Abstract

We report on the design and synthesis of a green-emitting iridium complex–peptide hybrid (IPH) 4, which has an electron-donating hydroxyacetic acid (glycolic acid) moiety between the Ir core and the peptide part. It was found that 4 is selectively cytotoxic against cancer cells, and the dead cells showed a green emission. Mechanistic studies of cell death indicate that 4 induces a paraptosis-like cell death through the increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations via direct Ca2+ transfer from ER to mitochondria, the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), and the vacuolization of cytoplasm and intracellular organelle. Although typical paraptosis and/or autophagy markers were upregulated by 4 through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, as confirmed by Western blot analysis, autophagy is not the main pathway in 4-induced cell death. The degradation of actin, which consists of a cytoskeleton, is also induced by high concentrations of Ca2+, as evidenced by costaining experiments using a specific probe. These results will be presented and discussed.

Introduction

Cyclometalated iridium(III) (Ir(III)) complexes such as fac-Ir(tpy)31a (tpy = 2-(4′-tolyl)pyridine) and fac-Ir(ppy)31b (ppy = 2-phenylpyridine) exhibit excellent photophysical properties, inducing long Stokes shifts, high quantum yields, and long lifetimes.1−4 Therefore, these analogs have widely been applied to organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs),1−4 photoredox catalysts,5,6 bioimaging probes,7−11 oxygen sensors,10 anticancer agents,12−17 and related areas.

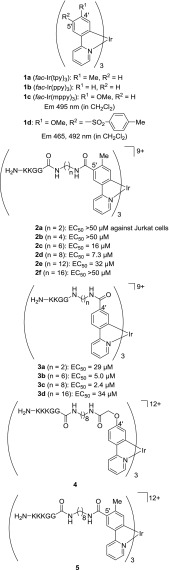

We previously reported on the characteristics of cyclometalated Ir complexes such as blue-green-red18,19 and white emitters,20 pH sensors,21−23 and anticancer agents24−28 via regioselective substitution reactions of 1a and 1b at the 5′-position (the p-position with respect to the C–Ir bond) of tpy and ppy ligands.18 Among them, cationic amphiphilic Ir complexes 2 with net charges of +9 to +12, which contain a cationic peptide sequence such as KKGG and KKKGG (K, lysine; G, glycine) connected through appropriate alkyl (C6 and C8) linkers between the Ir core and the peptide, have substantial cytotoxicity against Jurkat cells (T-lymphocyte leukemia) (EC50 = 7–16 μM).24

We recently reported on the design and synthesis of new iridium complex–peptide hybrids (IPHs) 3a–d, which contain the same alkyl linker and peptide sequence as those of 2 at the 4′-position (the m-position with respect to the C–Ir bond) of the ppy ligands (Chart 1).29 It was found that 3b and 3c have a more potent cytotoxicity against Jurkat cells than that for 2c and 2d, respectively. Jurkat cells treated with these Ir complexes undergo a morphological change accompanied by membrane disruption, and the dead cells show a strong green emission for 2 and a yellow emission in the case of 3. Mechanistic studies indicate that the cell death induced by these IPHs is related to intracellular Ca2+ signaling, possibly involving the interaction with a Ca2+–calmodulin (CaM) complex and localization on mitochondria. However, costaining experiments with other red-emitting probes (λem = 600–700 nm) (and green-emitting probes) were hampered by an overlap in the emission by a strong yellow emission (λem = 500–650 nm) of 3. Therefore, the design and synthesis of new IPHs having the same peptide units that emit a green luminescence are needed.

Chart 1.

In this context, we previously reported that electron-donating groups at the 4′-position of the ppy ligands in 1c stabilize the HOMO energy and increase the highest unoccupied molecular orbital (HOMO)–lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy gap, resulting in a blue shift in the luminescence emission.19 Typical examples include fac-Ir(mppy)31c (mppy = 2-(4′-methoxyphenyl)pyridine) and 1d that exhibit a blue emission at ca. 460 and 490 nm (Chart 1).

This background prompted us to design and synthesize a green-emitting IPH 4, which contains a hydroxyacetic acid (glycolic acid) moiety as an electron-donating group to connect with the H2N-KKKGG sequence at the 4′-positon of the ppy units (Chart 1). As a reference, 5 having the same alkyl linker and the same peptide sequence at the 5′-position of the tpy unit was synthesized. The findings indicated that 4 has a selective cytotoxicity against Jurkat cells (cancer cells), a process that is accompanied by membrane disruption, and its strong green emission was observed from the dead cells. In mechanistic studies, the dissociation constants of the Ir complexes with CaM were determined by 27 MHz quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) analysis. It was also found that 4 induces a paraptosis-like cell death of Jurkat cells through the enhancement of mitochondrial concentration of Ca2+ via direct Ca2+ transport from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to mitochondria, the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), and cytoplasmic vacuolization. It also appears that the morphological changes are due to the degradation of actin caused by the enhancement in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, as verified by staining experiments with 4 and the use of a probe that is specific for actin filaments.

Results and Discussion

Design and Synthesis of an Amphiphilic Ir Complex with a Cationic Peptide Sequence at the 4′-Position Showing a Green Emission

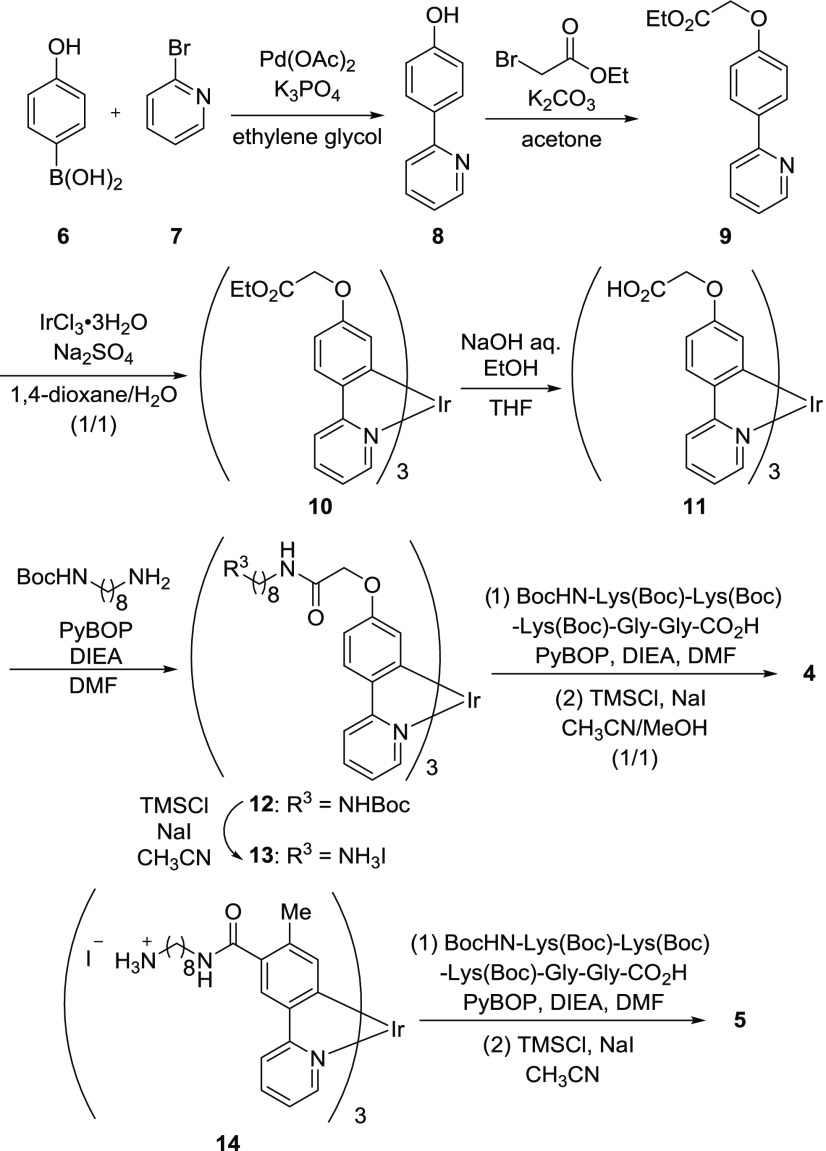

The synthesis of 4 is shown in Chart 2. 2-(4′-Hydroxyphenyl)pyridine 8 was synthesized from 4-hydroxyphenylboronic acid 6 and 2-bromopyridine 7 in ethylene glycol in the presence of Pd(OAc)2 and K3PO4, and the product was converted to the ligand 9 by the treatment with ethyl bromoacetate in acetone in the presence of K2CO3. After complexation of 9 with IrCl3 according to our previously reported method18 to give 10, the ethyl esters were subjected to hydrolysis with aqueous NaOH and EtOH in tetrahydrofuran (THF) to afford 11. The condensation of 11 with mono-Boc-protected 1,8-octanediamine linker gave 12, and the subsequent removal of the Boc group by the treatment with TMSCl and NaI in CH3CN afforded 13 as the HI salt. The protected peptide prepared by Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis was coupled with 13 to obtain the fully protected Ir complex. Finally, the protecting groups were removed by the treatment with TMSCl and NaI in CH3CN/MeOH (1/1), and the resulting product was purified by reversed-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) to afford the trifluoroacetate salt of 4. The Ir complex 5, as a reference compound of 4, was synthesized by the condensation of 14, the preparation of which was previously reported by us,24 with the protected peptide and a successive deprotection reaction. It should be noted that the diastereomers of 4 and 5 resulting from the racemic Ir centers (Δ and Λ forms) were not distinguished in the 1H NMR spectra and hence were not separated.

Chart 2.

Photophysical Properties of Ir Complexes

UV–vis and luminescence emission spectra of the Ir complex 4, 5, and 3c (10 μM) in degassed 100 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) at pH 7.4 and 25 °C are shown in Figure S1 in the Supporting Information, and their photophysical data are summarized in Table S1 in the Supporting Information. The concentrations of these Ir complexes in stock solutions (PBS: phosphate-buffered saline) were determined by our previous method24 from the molar extinction coefficient at 340 nm (ε340 nm = (1.91 ± 0.03) × 104 M–1 cm–1) of 10 and 12 (shown in Chart 2) that were characterized by elemental analysis. The strong absorption bands at ca. 300 nm were assigned to the 1π–π* transition of the ppy ligands, and the weak shoulder bands at ca. 350–500 nm were attributed to spin-allowed singlet-to-singlet metal-to-ligand charge transfer (1MLCT) transitions, spin-forbidden singlet-to-triplet (3MLCT) transitions, and 3π–π* transitions as compared that of 3c (ca. 540 nm) (Figure S1b in the Supporting Information), and emission quantum yields (Φ) of 4 and 5 were determined to be 0.43 and 0.41, respectively. It should be noted that the emission of 4 exhibits a considerable blue shift (ca. 505 nm). These results are consistent with reports that an electron-donating methoxy group on the phenylpyridine (ppy) ligand induces a blue shift in its emission spectra.19

Density Function Theory Calculations of 10

Density function theory (DFT) calculations of 10 as representative examples of 4 and 10–13 were carried out using the Gaussian09 program, in which the B3LYP hybrid functional was used together with the LanL2DZ basis set for the Ir atom and the 6-31G basis set for the H, C, N, and O atoms.30 Time-dependant DFT (TD-DFT) calculations were carried out based on all ground-state geometries using the same functional and basis set. As shown in Figure S2 in the Supporting Information, the HOMO shapes of 10 and 15 (Chart 3) are similar and consisted of phenyl-π and Ir-d orbitals (Figures S2a,c in the Supporting Information), while the LUMO is mainly localized on the pyridine ring (Figures S2b,d in the Supporting Information). The introduction of an electron-donating glycolic acid group at the 4′-position raises its HOMO level, resulting in a blue shift in its emission (Table S2 in the Supporting Information), as evidenced by Figure S1 in the Supporting Information.

Chart 3.

Cytotoxicity of IPHs that Contain a Cationic Peptide Sequence against Cancer Cells (Jurkat Cells) and a Normal Cell Line (IMR90 Cells)

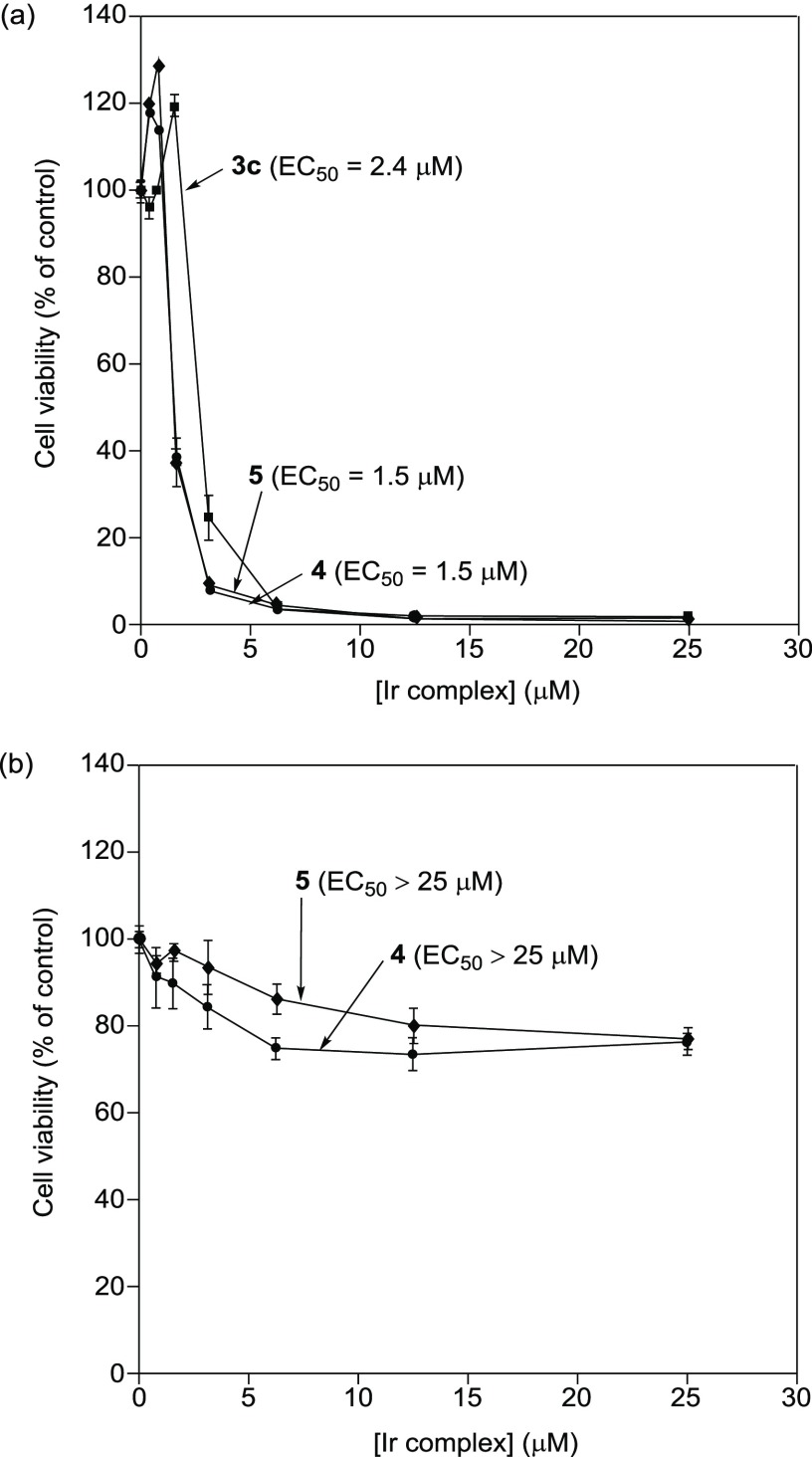

The cytotoxicities of 4 and 5 containing the cationic KKKGG peptide sequence against Jurkat cells (T-lymphocyte leukemia) were assessed by means of an 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Figure 1a). Jurkat cells (2.0 × 104 cells/mL) were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)/RPMI 1640 medium containing 4 or 5 (0–25 μM). The results of the MTT assay indicate that 4 had nearly the same cytotoxicity (EC50 = 1.5 μM) as 5 (EC50 = 1.5 μM) and is slightly more cytotoxic than 3c (EC50 = 2.4 μM). On the other hand, 4 and 5 (0–25 μM) weakly induced cell death of IMR90 cells (human Caucasian fetal lung fibroblast), which are used as a model of normal cells (Figure 1b). These results suggest that Ir complexes 4 and 5 have the capacity to selectively kill cancer cells.

Figure 1.

(a) MTT assay of Jurkat cells with 4 (closed circles), 5 (closed diamonds), and 3c (closed squares) in 10% FBS/RPMI medium (incubation at 37 °C for 24 h). (b) MTT assay of IMR90 cells with 4 (closed circles) and 5 (closed diamonds) in 10% FBS/RPMI medium (incubation at 37 °C for 24 h). The net charge of each complex is assumed to be +12 (4 and 5) and +9 (3c).

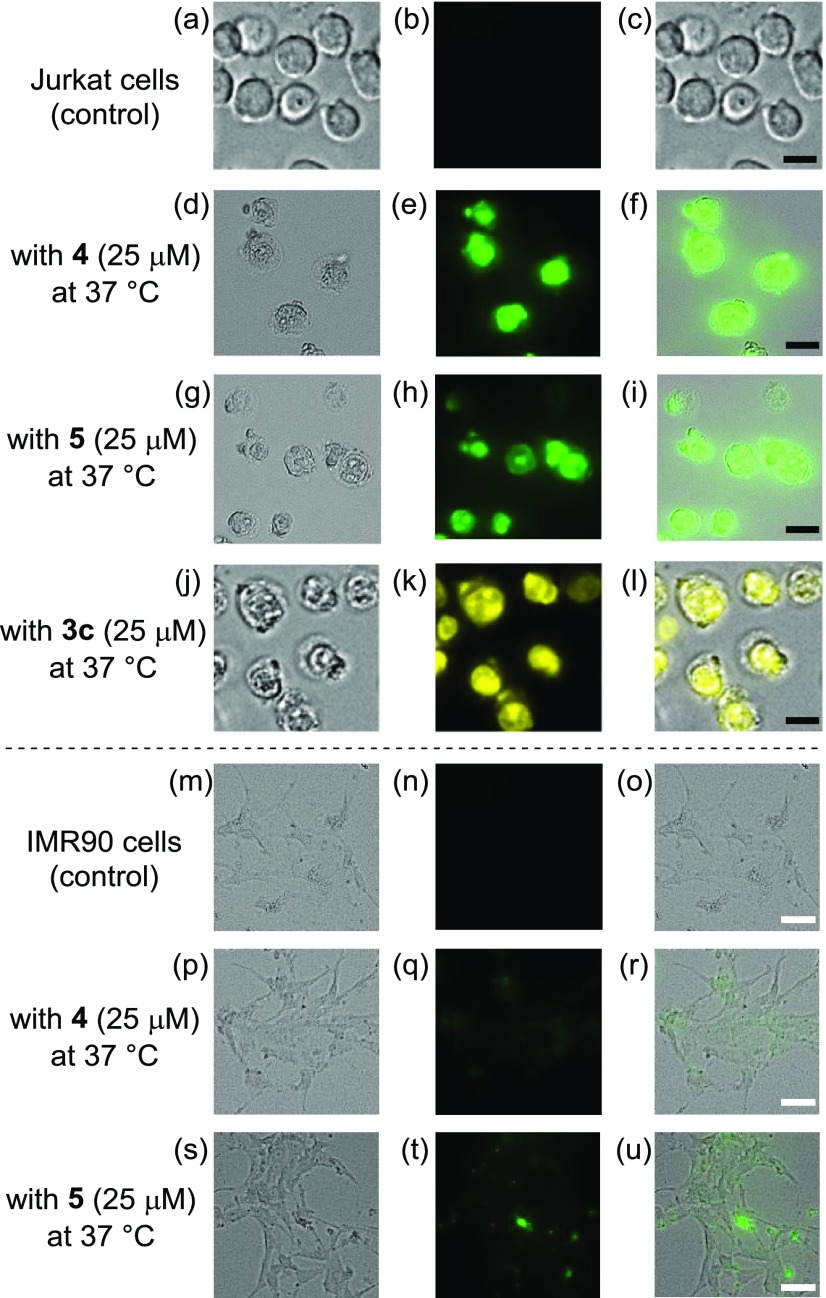

Figure 2a–l shows fluorescence microscopic images of Jurkat cells treated with 4, 5, and the reference compound 3c ([Ir complex] = 25 μM). Considerable morphological changes were induced by 4, 5, and 3c, and the dead cells exhibited green emission arising from these IPHs. The cytotoxicities of 4 and 5 against IMR90 cells (human Caucasian fetal lung fibroblast), a normal cell line, were also evaluated. In Figure 2p–u, morphological changes and emissions of 4 and 5 from the cells were both negligible or weak, indicating their lower cytotoxicity against IMR90 cells.

Figure 2.

Typical luminescence microscopy images of (a–l) Jurkat cells and (m–u) IMR90 cells treated with 4 (25 μM), 5 (25 μM), and 3c (25 μM) at 37 °C for 1 h. (a) Bright field, (b) emission, and (c) overlay images of the control; (d) bright field, (e) emission, and (f) overlay images with 4; (g) bright field, (h) emission, and (i) overlay images with 5; (j) bright field, (k) emission, and (l) overlay images with 3c of Jurkat cells; (m) bright field, (n) emission, and (o) overlay images of the control; (p) bright field, (q) emission, and (r) overlay images with 4; (s) bright field, (t) emission, and (u) overlay images with 5 of IMR90 cells. Scale bar (black) is 10 μm, and scale bar (white) is 50 μm.

Measurement of Intracellular Uptake of Ir Complexes in Jurkat Cells

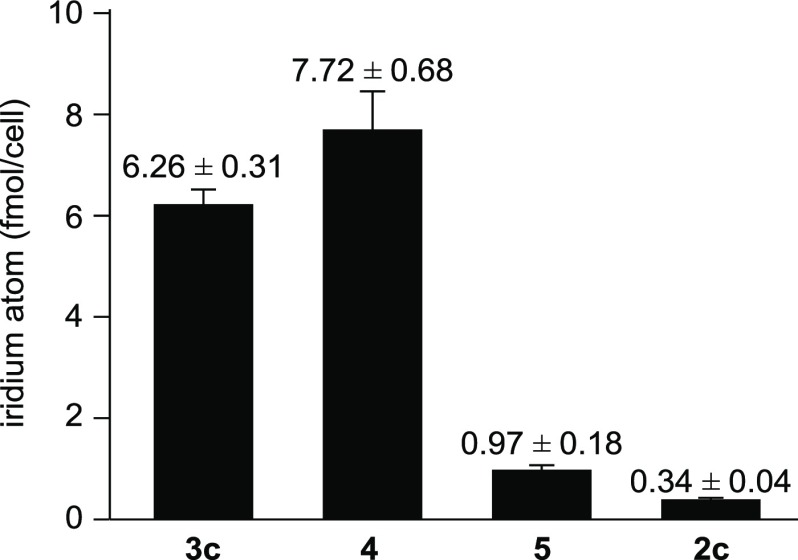

The intracellular uptake of IPHs 3c, 4, 5, and 2c in Jurkat cells was examined by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometer (ICP-MS). Jurkat cells were incubated with 3c, 4, 5, and 2c (25 μM) for 1 h at 37 °C. After treatment, the cells were washed three times with PBS and lysed by nitric acid. Then, lysed cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C, and the samples were analyzed on ICP-MS. Interestingly, it was found that the intracellular uptake of 3c (6.26 ± 0.31 fmol/cell) and 4 (7.72 ± 0.68 fmol/cell) was higher than that of 5 (0.97 ± 0.18 fmol/cell) and 2c (0.34 ± 0.04 fmol/cell), as summarized in Figure 3. We assume that the three polycationic peptide parts of 3c and 4 are assembled in the same direction of its structure and that the position of cationic peptide parts on the IPHs is important for their intracellular uptake.

Figure 3.

Intracellular uptake of IPHs 3c, 4, 5, and 2c (25 μM) into Jurkat cells at 37 °C for 1 h measured by ICP-MS.

Effect of Inhibitors of Intracellular Events, Programmed Cell Death, and a Calmodulin-Binding Molecule

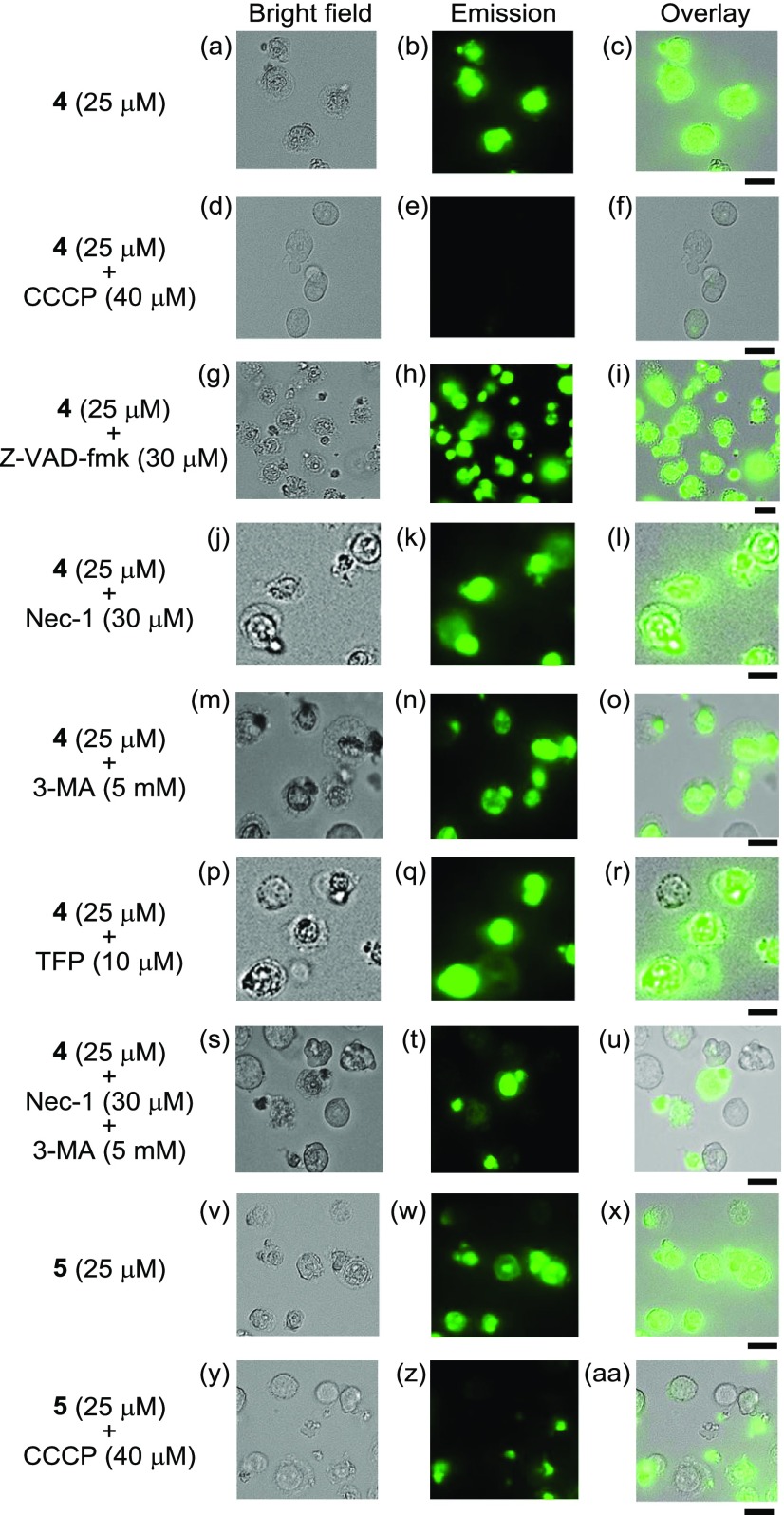

In our previous paper, it was reported that the induction of cell death by 2c is not inhibited by the broad caspase inhibitor benzyloxycarbonyl-VAD(OMe)-fluoromethylketone (Z-VAD-fmk), indicating that cell death does not involve apoptosis.24 In this study, the effects of Z-VAD-fmk, 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP, an uncoupling reagent and an inhibitor of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake), necrostatin-1 (Nec-1, a specific RIPK-1 inhibitor and necroptosis inhibitor), 3-methyladenine (3-MA, an inhibitor of autophagosome formation that functions by inhibiting type III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K), an autophagy inhibitor), and trifluoperazine (TFP, a CaM-binding molecule) (for the structures of these inhibitors, see Charts S1 and S2 in the Supporting Information) on the cytotoxicities of 4 and 5 were examined (Figure 4). Jurkat cells were preincubated with these inhibitors31 for 30 min and then treated with 4 (25 μM) or 5 (25 μM) for 1 h. Morphological changes (and cell death) in the Jurkat cells caused by 4 and 5 were inhibited to a considerable extent by treatment with CCCP (40 μM), and the extent of IPH emission was negligible (Figure 4d–f,y-aa), indicating the existence of a relationship between the cell death and intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and/or membrane potential of mitochondria. On the other hand, the cell death induced by 4 and 5 was negligibly inhibited by Z-VAD-fmk (Figure 4g–i), Nec-1 (Figure 4j–l), 3-MA (Figure 4m–o), TFP (Figure 4p–r), and combinations thereof (Nec-1 + 3-MA) (Figure 4s–u). These results indicate that cell death induced by IPHs does not involve apoptosis, necroptosis, or autophagy alone.

Figure 4.

Effect of Z-VAD-fmk (15 μM, an apoptosis inhibitor), necrostatin-1 (30 μM, a necroptosis inhibitor), 3-MA (5 mM, an autophagy inhibitor), TFP (10 μM, a CaM-binding molecule), and CCCP (40 μM, an uncoupling reagent and an inhibitor of Ca2+ influx into mitochondria) on the cell death of Jurkat cells induced by 4. (a, d, g, j, m, p, s, v, y) Bright field images of Jurkat cells; (b, e, h, k, n, q, t) emission images of 4; (w, z) emission images of 5; (c) overlay image of (a) and (b); (f) overlay image of (d) and (e); (i) overlay image of (g) and (h); (l) overlay image of (j) and (k); (o) overlay image of (m) and (n); (r) overlay image of (p) and (q); (u) overlay image of (s) and (t); (x) overlay image of (v) and (w); (aa) overlay image of (y) and (z). Excitation at 377 nm. Scale bar (black) is 10 μm.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ Spike Induced by 4

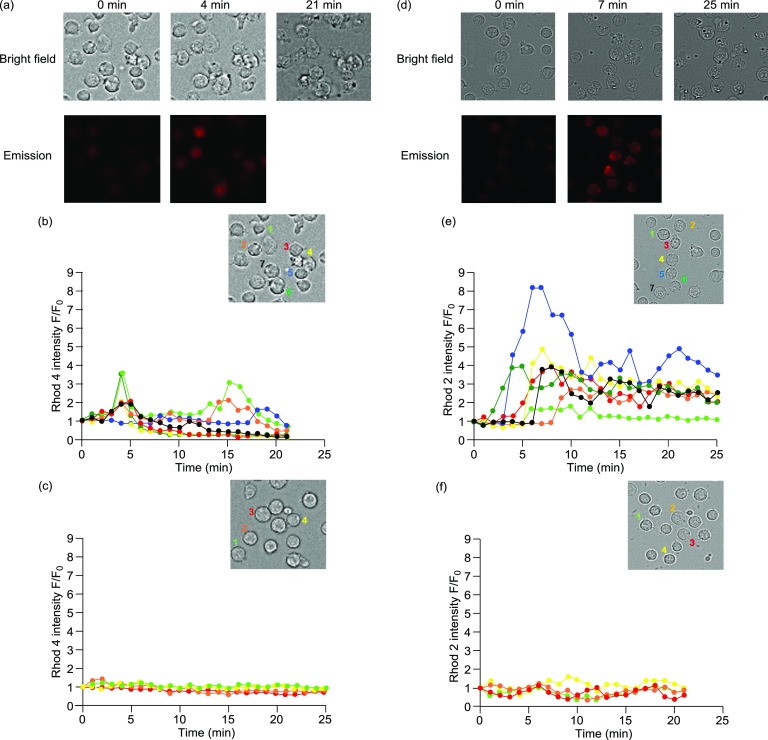

Recently, the relationship of intracellular Ca2+ signaling and CaM with cell survival and cell death was well discussed.32−38 The enhancement in intracellular Ca2+ concentration was examined by time-course fluorescent microscopy according to our previous reports.24,25 Jurkat cells were treated with Rhod-4/AM, a cytosolic Ca2+ indicator, or Rhod-2/AM, a mitochondrial Ca2+ indicator, as confirmed by costaining experiments with MitoTracker Green (Figure S3 in the Supporting Information), whose red emission is enhanced upon complexation with Ca2+ in cytosol and mitochondria, respectively. As shown in Figure 5d,e, the fluorescent intensity of Rhod-2 was enhanced in a few minutes after the addition of 4 (50 μM) in mitochondria rather than in cytosol (Figure 5a,b), and the morphology of Jurkat cells changed after ca. 20 min. In contrast, 13, which contains no peptide part and shows a very weak cytotoxicity, induces negligible Ca2+ response (Figure 5c,f). These results suggest that 4 initially induces an increase in the Ca2+ concentrations in mitochondria rather than in cytosol at the early stages of the cell death processes.

Figure 5.

(a) Typical luminescence images (Biorevo, BZ-9000, Keyence) of Jurkat cells treated with Rhod-4 (red emission), followed by 4 (50 μM). Excitation at 540 nm for Rhod-4. (b, c) Time-dependent changes in the fluorescent intensity of Rhod-4 (F/F0) after the treatment with 4 (b) and 13 (c) (cell 1 (light green), 2 (orange), 3 (red), 4 (yellow), 5 (blue), 6 (green), and 7 (black)). (d) Typical luminescence images (Biorevo, BZ-9000, Keyence) of Jurkat cells treated with Rhod-2 (red emission), followed by 4 (50 μM). Excitation at 540 nm for Rhod-2. (e, f) Time-dependent fluorescent changes of Rhod-2 (F/F0) after the treatment with 4 (e) and 13 (f) (cell 1 (light green), 2 (orange), 3 (red), 4 (yellow), 5 (blue), 6 (green), and 7 (black)).

We checked the effect of BAPTA/AM, which is a cytosolic Ca2+ scavenger, on the cell death induced by 4 by means of microscopic observations and MTT assays (Figure S4 in the Supporting Information). Figure S4 in the Supporting Information indicates that BAPTA/AM negligibly inhibits cell death by 4, suggesting that mitochondrial Ca2+ spike is an important event that induces cell death and the change in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is not so important.

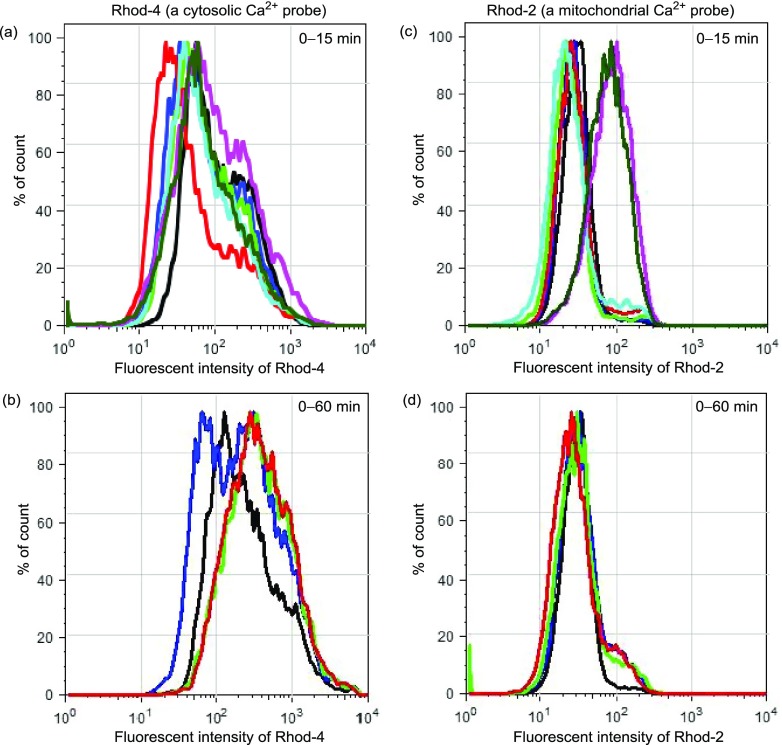

The cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations were also checked by flow cytometric analysis (Figure 6). Jurkat cells were preincubated with Rhod-4/AM or Rhod-2/AM for 30 min, treated with 4 (50 μM) for a given incubation time, and then immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Figure 6a,b shows the emission intensity of Rhod-4 for 0–15 and 0–60 min after the addition of 4, respectively, and Figure 6c,d shows the emission change of Rhod-2 for 0–15 and 0–60 min after the addition of 4, respectively. The apparent increase in the emission from Rhod-2 was observed within 15 min after the addition of 4 to Jurkat cells, supporting the observations in Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Flow cytometry analysis of Jurkat cells after the treatment with (a, b) Rhod-4 (5 μM) or (c, d) Rhod-2 (5 μM) and then with 4 (50 μM). Different colors indicate the incubation times of 4: control (black), 2 min (blue), 4 min (light green), 6 min (red), 8 min (sky blue), 10 min (violet), and 15 min (green) in (a) and (c), and control (black), 20 min (blue), 40 min (light green), and 60 min (red) in (b) and (d).

Measurement of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm)

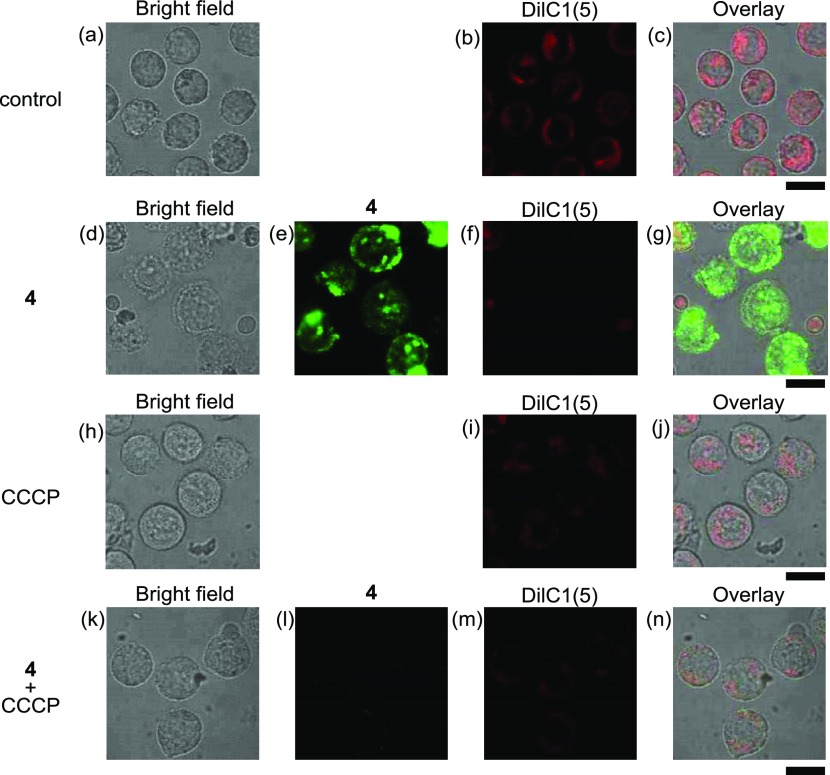

The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) was measured using DilC1(5) (1,1′,3,3,3′,3′-hexamethylindodicarbocyanine iodide)39 (its structure is shown in Chart S3 in the Supporting Information), which accumulates in mitochondria and responds to ΔΨm. In Figure 7d–g, considerable decrease in the emission of DilC1(5) was observed in the presence of 4 (25 μM), as compared with Figure 7b,c, indicating the loss of ΔΨm. The decrease in ΔΨm was also observed by the treatment of CCCP, which prevents Ca2+ influx into mitochondria and inhibits cell death induced by 4, in the absence (h–j) or presence (k–n) of 4 (25 μM). It has been well described that the influx of Ca2+ into mitochondria induces the loss of ΔΨm, resulting in cell death.40,41 These results allowed us to conclude that 4 induces the influx of Ca2+ into mitochondria and then the loss of ΔΨm, which trigger the cell death signaling pathway.

Figure 7.

Typical luminescent confocal microscopy images of Jurkat cells treated with DilC1(5) (500 nM) in the presence of 4 (25 μM) and/or CCCP (40 μM): (a, d, h, k) bright field images of Jurkat cells; (b, f, i, m) emission images of DilC1(5); (e, l) emission images of 4; (c) overlay image of (a) and (b); (g) overlay image of (d)–(f); (j) overlay image of (h) and (i); (n) overlay image of (k)–(m). Excitation at 405 nm for (e) and (l); 635 nm for (b), (f), (i), and (m). Exposure time is 20 μs/pixel. Scale bar (black) is 10 μm.

Confocal Microscopic Observations of Jurkat Cells with IPHs and Specific Probes for Intracellular Proteins or Organelles

Our previous reports indicated that one of the target proteins of IPHs such as 2c and 2d is the Ca2+–CaM complex,25 which controls intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and regulates certain types of protein functions such as calmodulin kinase, phosphorylase kinase, and related targets,42 resulting not only in cell proliferation and metabolic homeostasis but also in processes such as apoptosis and autophagy, leading to the death of cancer cells.32−38 It is well known that many types of programmed cell death (PCD) are related to malfunction and/or overfunction of intracellular organelles such as mitochondria43−47 and lysosomes.48−51 Furthermore, actin filaments provide mechanical structure and motility to ameboid and animal cells.52

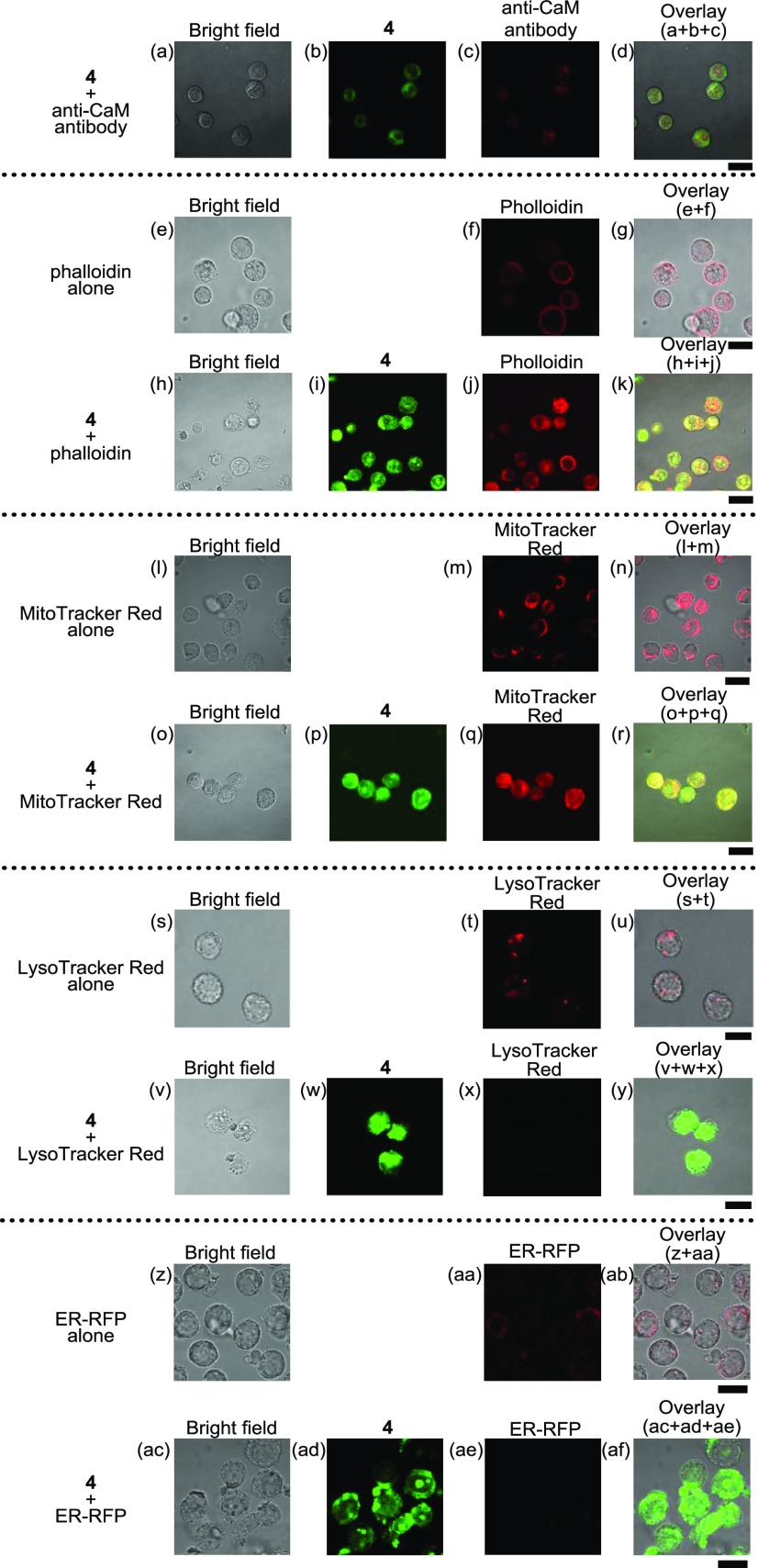

These facts prompted us to conduct staining experiments of Jurkat cells by treating them with an anticalmodulin (CaM) antibody (+antirabbit IgG H&L conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594), phalloidin (a probe for actin), MitoTracker Red (a probe for mitochondria), LysoTracker Red (a probe for lysosome), and ER-RFP (a probe conjugated with the red fluorescent protein (RFP) for the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)) (Figure 8). For staining with an anti-CaM antibody, Jurkat cells were treated with 4 (10 μM) at 37 °C for 1 h and then incubated with the anti-CaM antibody at room temperature for 2 h accompanied by the treatment with the Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody. For the staining of actin, mitochondria, and lysosomes, the cells were treated with 4 for 1 h and then incubated with a phalloidin–CruzFluor 555 conjugate (at a dilution of 1/1000), MitoTracker Red (100 nM), and LysoTracker Red (500 nM) for 1 h, sequentially. For the staining of ER, the cells were pretreated with ER-RFP for 24 h and then incubated with 4 for 1 h. As shown in Figure 8a–d, the overlapping of the green emission of 4 and the red emission of anti-CaM antibody was negligible. This point will be discussed later.

Figure 8.

Typical luminescence confocal microscopy images of Jurkat cells that had been treated with anti-CaM antibody–Alexa Fluor 594 conjugate, phalloidin–CruzFluor 555 conjugate, MitoTracker Red, LysoTracker Red, and ER-RFP in the presence (10 μM) or absence of 4: (a, e, h, l, o, s, v, z, ac) bright field of Jurkat cells; (b, i, p, w, ad) emission images of 4; (c) emission images of the anti-CaM antibody; (d) overlay image of (a)–(c); (f, j) emission images of phalloidin; (g) overlay image of (e) and (f); (k) overlay images of (h)–(j); (m, q) emission images of MitoTracker Red; (n) overlay images of (l)–(m); (r) overlay images of (o)–(q); (t, x) emission images of LysoTracker Red; (u) overlay images of (s)–(t); (y) overlay images of (v)–(x); (aa, ae) emission images of ER-RFP; (ab) overlay images of (z)–(aa); (af) overlay images of (ac)–(ae). Excitation at 405 nm for (b), (i), (p), and (w) and at 559 nm for (c), (f), (j), (m), (q), (t), and (x). Exposure time was 20 μs/pixel. Scale bar (black) is 10 μm.

Although actin constructs cytoskeletons in the cells in the absence of 4 (Figure 8e–g), this network underwent degradation after the treatment with 4, and the green emission of 4 and the red emission of phalloidin were overlapped to a considerable extent (Figure 8h–k). The green emission of 4 and the red emission of MitoTracker Red were also considerably overlapped (Figure 8l–r). On the other hand, the red emission of LysoTracker Red and ER-RFP was decreased by the treatment with 4 (Figure 8s–y,z–af), indicating the degradation of lysosome and ER by 4. These results suggest that 4 interacts with actin filaments and mitochondria and induces lysosome- and ER-related cell death accompanied by morphological changes, possibly through 4-(Ca2+-CaM) complexation.

Evaluation of the Complexation of IPHs with CaM by 27 MHz QCM Analysis

Based on our previous observation regarding the interaction of IPHs with CaM,24,25,29 the interaction of 4 with CaM was assessed by 27 MHz quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) measurements. CaM was immobilized on a sensor chip, to which 1 μL of the stock solutions of 4 (0.39 mM), 5 (0.50 mM), and 3c (0.41 mM) in PBS was injected in the absence of Ca2+ (Figure S3a in the Supporting Information); as shown in Figure S3b in the Supporting Information, 4 was added to the Ca2+ complex of CaM (1 μL of a 40 mM CaCl2 solution was first added to CaM, after which an aliquot of the 0.39 mM aqueous solution of 4 was injected). From the ΔF decay curves, the complexation constants (Kapp) of 4, 5, and 3c were determined to be (1.0 ± 0.1) × 106, (9.1 ± 0.1) × 105, and (1.2 ± 0.1) × 105 M–1, respectively, from which their dissociation constants (Kd) were calculated to be 0.94 ± 0.05, 1.1 ± 0.1, and 8.3 ± 0.1 μM, respectively (Table 1). The interaction of 4 with CaM in the presence of Ca2+ (80 μM) was somewhat weaker, and the Kapp and Kd values were determined to be (3.0 ± 0.1) × 105 M–1 and 3.3 ± 0.1 μM, respectively (Figure S3b in the Supporting Information and Table 1).

Table 1. Complexation Constants of IPHs and Trifluoperazine (TFP) with Calmodulin (Assuming a 1:1 Complexation) in PBS at 25 °C, as Determined by 27 MHz QCM.

| analytes | Kapp (M–1) | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| 4 in the absence of Ca2+ | (1.0 ± 0.1) × 106 | 0.94 ± 0.05 |

| 4 in the presence of Ca2+ (80 μM) | (3.0 ± 0.1) × 105 | 3.3 ± 0.1 |

| 5 | (9.1 ± 0.1) × 105 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| 3c | (1.2 ± 0.1) × 105 | 8.3 ± 0.1 |

| TFP | (1.2 ± 0.1) × 105 | 8.3 ± 0.1 |

As a reference compound, the Kapp and Kd values of trifluoperazine (TFP),53,54 which is a CaM-binding molecule (Chart S2 in the Supporting Information), were determined to be 1.20 × 105 M–1 and 8.3 μM, respectively (Figure S3c in the Supporting Information and Table 1). These data imply that 4, 5, 3c, and TFP bind to CaM with Kd values of 0.9–8.3 μM. Although TFP only weakly induces the cell death of Jurkat cells (EC50 ≈ 50 μM), cooperative effects with 4 (25 μM) were observed to be negligible (data not shown).

In Figure 8a–d, negligible overlap of the green emission from 4 and the red emission from the anti-CaM antibody (+secondary IgG H&L-Alexa Fluor 594) was observed. Then, the binding affinity of the anti-CaM antibody (Abcam) with CaM was checked by QCM analysis in the presence (80 μM) and absence of Ca2+ (Figure S6 and Table S3 in the Supporting Information). The Kapp and Kd values of the anti-CaM antibody were determined to be (4.22 ± 0.15) × 108 M–1 and 2.4 ± 0.1 nM, respectively, in the absence of Ca2+. However, the interaction of the antibody with CaM was very weak in the presence of Ca2+ (>1 mM), suggesting that the anti-CaM antibody has weak affinity with the Ca2+ complex of CaM. It was assumed that this is the reason why negligible overlap of the emission of 4 and the anti-CaM antibody was observed in Figure 8a–d.

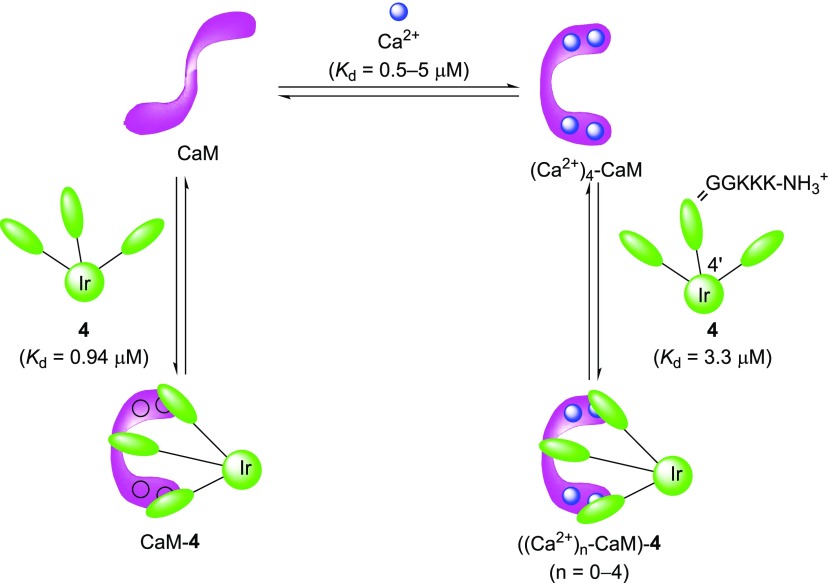

It is known that CaM binds to four Ca2+ ions via four EF hands with Kd values of 0.5–5 μM, which are dependent on the Ca2+ binding sites in N- and C-terminal EF hands.39 The aforementioned results of the QCM analysis using CaM, Ca2+, and 4 (Table 1) suggest that the complex of 4 with Ca2+-free CaM (Kd = 0.94 μM) is slightly more stable than that of 4 with Ca2+-CaM (Kd = 3.3 μM). It should also be noted that these Kd values between 4 and CaM are close to the Kd values of 4 and (Ca2+)n–CaM complexes (n = 0–4) (Chart 4).

Chart 4. Our Assumption on the Complexation of 4 with Ca2+-CaM.

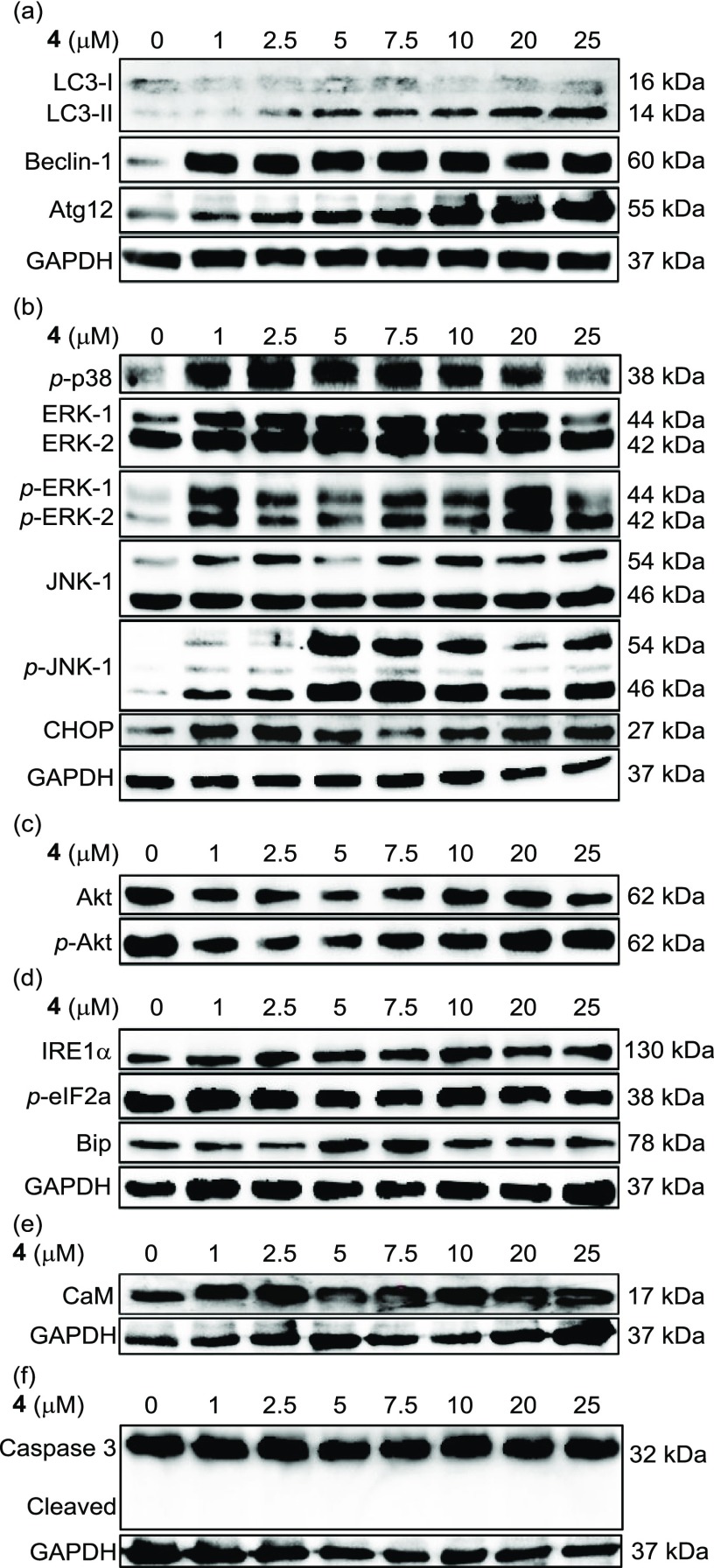

Western Blot Analysis of Jurkat Cells Treated with 4

The aforementioned results strongly suggest that IPHs induce some sort of programmed cell death (PCD), which can be categorized into several types such as apoptosis, necroptosis, paraptosis, and autophagic cell death.51,55−63 For the further study of this issue, we checked the expression levels of proteins that are related to apoptosis, autophagy, and some signaling pathway in Jurkat cells that had been treated with 4 by Western blot analysis (Figure 9). The degradation of caspase-3 was negligible, suggesting that this is not an apoptosis process, as previously shown in Figure 4g–i.

Figure 9.

Western blot analysis of Jurkat cells treated with 4 (0–25 μM). Proteins related to (a) autophagy, (b) MAPK signaling pathway, and (c) PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, (d) ER stress, (e) CaM, and (f) apoptosis were investigated in a dose-dependent manner.

In Figure 9a, LC3-I, LC3-II, Beclin-1, and Atg-12, which are autophagy markers, were upregulated by 4 in a dose-dependent manner. We further examined the autophagy signaling pathway such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (Figure 9b), the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (Figure 9c), and ER stress (Figure 9d). In Figure 9b, p-p38 (phosphorylated form of p38), p-ERK-1, -2 (ERK: extracellular regulated kinase), p-JNK (JNK: c-jun N-terminal kinase 1), and CHOP, which are typical marker molecules of the MAPK signaling pathway, were upregulated after the treatment by 4; in contrast, only negligible changes were observed in the expression levels of proteins related to the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (Akt and p-Akt) and ER stress (IRE1α, p-eIF2a, and Bip) (Figure 9c,d). Change in the expression levels of CaM was also negligible (Figure 9e). In addition, negligible effect of 4 was observed in the apoptosis signaling pathway in Jurkat cells (Figure 9f).

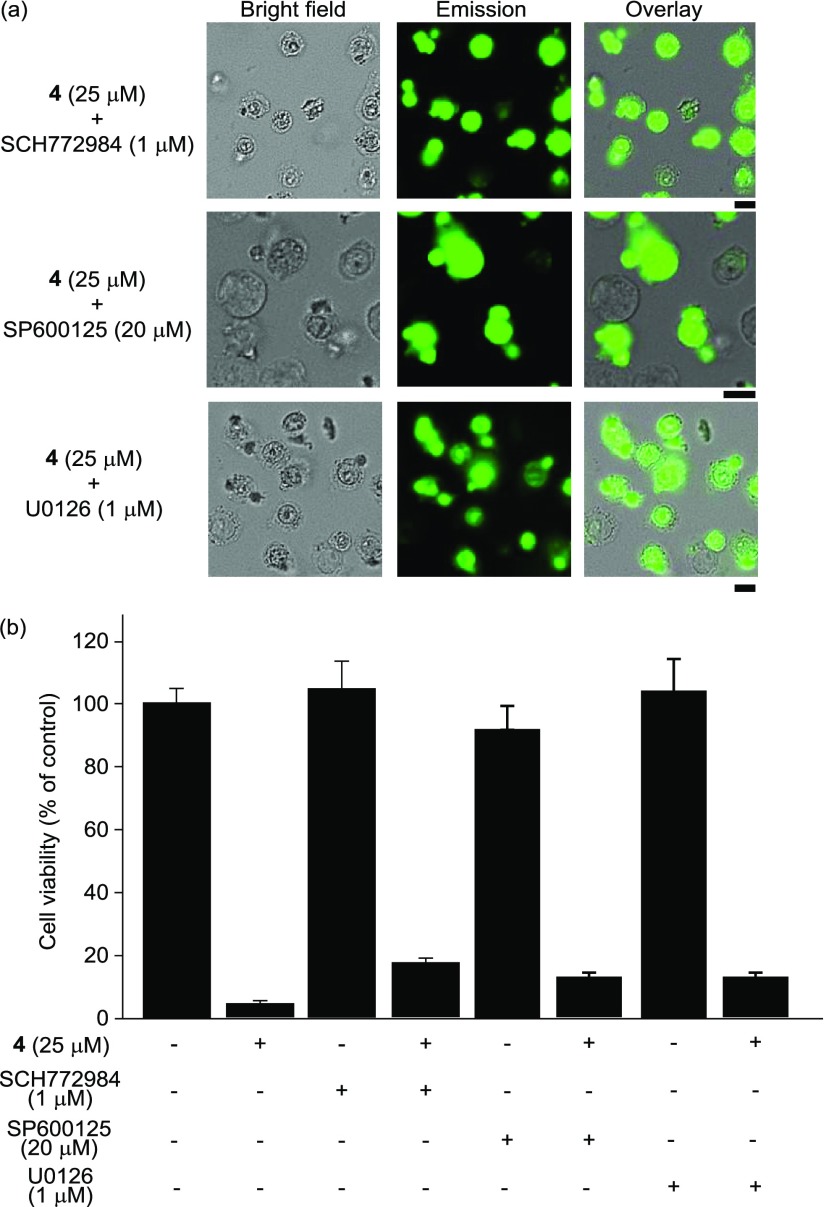

To evaluate the role of the MAPK signaling pathway in this process, the effects of SCH772984, SP600125, and U0126, which are ERK, JNK, and MEK inhibitors (see Chart S4 in the Supporting Information for their chemical structures), respectively, were assessed (Figure 10). In Figure 10a, morphological changes (and cell death) of Jurkat cells by 4 were observed, and the dead cells exhibited a strong green emission from 4. The results of MTT assays indicate that negligible inhibition of cell death induced by 4 (25 μM, 1 h) was observed by SCH772984, SP600125, or U0126 (Figure 10b), suggesting that autophagy-mediated cell death through the MAPK signaling pathway is not a major pathway in 4-induced cell death.

Figure 10.

Effect of SCH772984 (ERK inhibitor), SP600125 (JNK inhibitor), and U0126 (MEK inhibitor). (a) Typical luminescence microscopy images of Jurkat cells treated with SCH772984, SP600125, and U0126. (b) MTT assays of Jurkat cells in the presence and/or absence of 4 and SCH772984, SP600125, or U0126. Scale bar (black) is 10 μm.

Cytoplasmic Vacuolization of Jurkat Cells Induced by 4

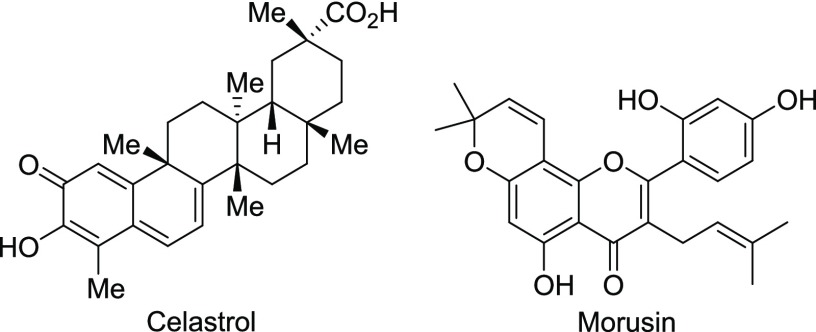

We also suspected that paraptosis, a process that has been reported as a relatively new category of PCD,55 might be involved. Choi et al. reported that celastrol (Chart 5), a naturally occurring triterpenoid isolated from Tripterygium wilfordii, induces the swelling of the ER and/or mitochondria through the release of Ca2+ from the ER and its subsequent influx into mitochondria, accompanied by the activation of the ERK signaling pathway.56,57 Xue and co-workers reported that morusin (Chart 5), which was isolated from Morus australis, induces paraptosis with similar morphological changes and the development of a signaling pathway similar to that for celastrol.58

Chart 5.

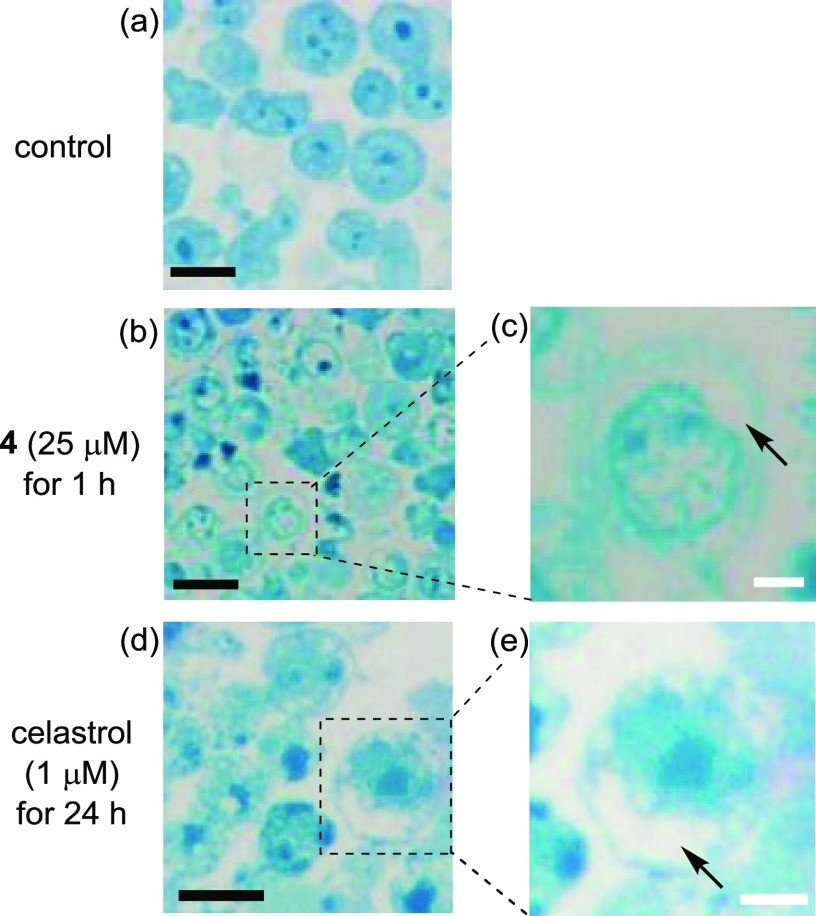

Figure 10b,c shows images of Jurkat cells that were treated with 4 (25 μM) for 1 h, fixed with glutaraldehyde and osmium tetroxide (OsO4), embedded into Poly 812 resin, sliced, and then stained with methylene blue. These pictures clearly show vacuolization of the cytoplasm and intracellular organelle (it has been described in the literature that cytoplasmic vacuolization is triggered by the damage of mitochondria and ER)55−58 in Jurkat cells and morphological changes. The same intracellular morphological changes were observed by the treatment with celastrol (1 μM and incubation for 24 h) (Figure 11d,e).

Figure 11.

Typical microscopy images of Jurkat cells stained with methylene blue after the treatment with 4 (25 μM) at 37 °C for 1 h. (a) Control; (b, c) Jurkat cells treated with 4 (25 μM, for 1 h); and (d, e) Jurkat cells treated with celastrol (1 μM, for 24 h). Arrows in (c) and (e) indicate cytoplasmic vacuolization induced by 4 and celastrol, respectively. Scale bar (black) is 10 μm, and scale bar (white) is 5 μm.

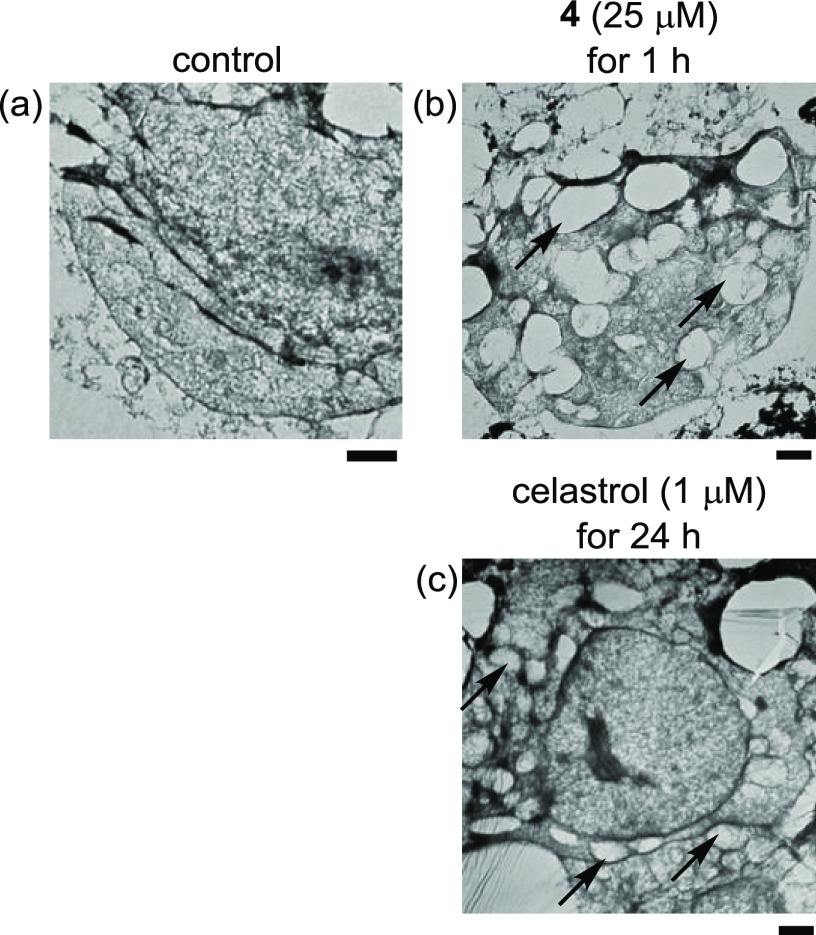

In addition, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of Jurkat cells treated with 4 and celastrol were also undertaken. Pictures in Figure 12 display the vacuolization in Jurkat cells, similar to Figure 11, strongly implying that 4 and celastrol induce similar PCD, which can be classified into paraptosis although their PCD-inducing mechanisms are somewhat different, as described in Figure 6 in the text and Figure S4 in the Supporting Information. These results also suggest that the staining experiments of dead cells with glutaraldehyde, OsO4, and methylene blue shown in Figure 11 may be a more convenient and cheaper method than TEM experiments to characterize paraptosis and the related PCD.

Figure 12.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of Jurkat cells treated with 4 (25 μM, 1 h) and celastrol (1 μM, 24 h). (a) Control, (b) Jurkat cells treated with 4 (25 μM, for 1 h), and (c) Jurkat cells treated with celastrol (1 μM, for 24 h). Arrows in (b) and (c) indicate cytoplasmic vacuolization induced by 4 and celastrol, respectively. Scale bar (black) is 1 μm.

Plausible Mechanism for Cell Death Induced by 4

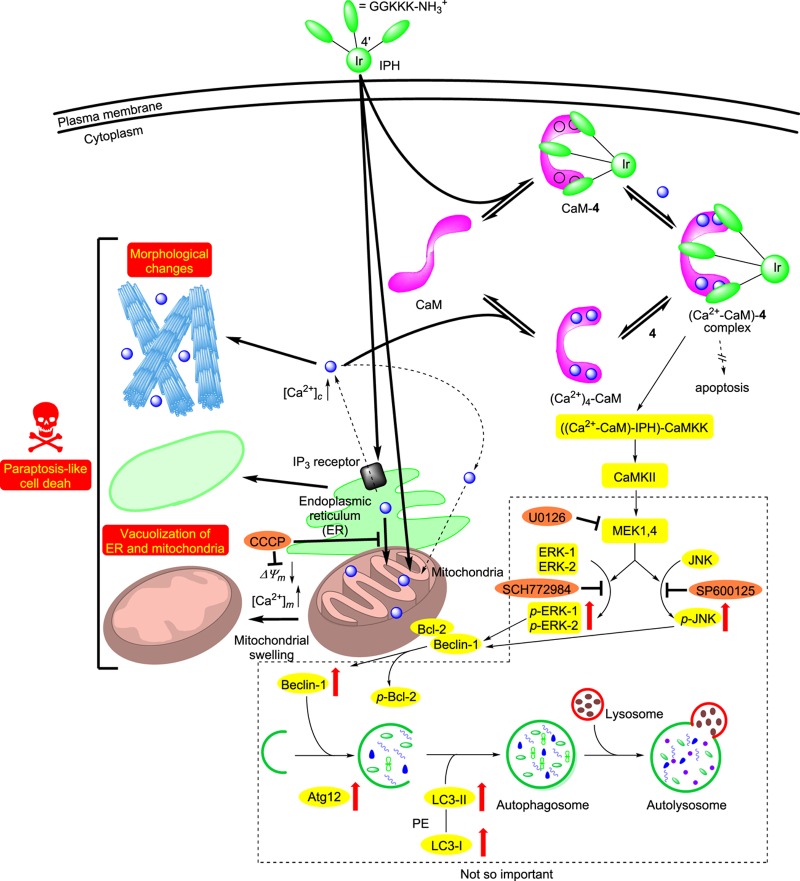

The aforementioned experimental results are summarized as follows and in Chart 6.

-

(1)

The cytotoxicity of 4 is more potent than the reference compound 5, which could be attributed to its more efficient intracellular uptake than that of 5, partially due to the position of peptide units (Figures 2 and 3). The similar order of the EC50 value of 4 to that of 5 is controlled by the affinity of these IPHs to the target biomolecules, whose affinity with these IPHs would be on the order of micromolar.

-

(2)

IPH 4 enhances the concentration of Ca2+ in mitochondria rather than in cytosol (Figures 5 and 6), possibly by Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and then induces the loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), which triggers the malfunction of mitochondria (Figure 8o–r). Recently, it has been described that the excessive Ca2+ release promotes PCD and proliferation via Ca2+-signaling events in the ER and mitochondrion,32 which may support our hypothesis. This mechanism is also supported by the findings that cell death was considerably inhibited by CCCP, which is an inhibitor of mitochondrial Ca2+ influx and an uncoupling reagent that compromises the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) (Figures 4d–f and 7h–j). Further studies indicated that 4 induces mitochondrial Ca2+ overload within 15 min after the addition to Jurkat cells, as evidenced by Figure 6c. In contrast, celastrol, a naturally occurring triterpenoid, stimulates cytosolic Ca2+ overload in 1–5 h after the addition to Jurkat cells (Figure S7 in the Supporting Information).

-

(3)

Another possibility is that 4 binds to actin and promotes the degradation of actin filaments and the morphological changes in Jurkat cells (Figures 1 and 8e–k). It is also reported that the enhancement of intracellular Ca2+ collapses the bundling of actin filaments, resulting in morphological changes in the cells.64−66

-

(4)

The results of QCM measurements of CaM with 4 indicated that 4 binds to a Ca2+-free CaM (Kd = 0.94 μM) a little bit more strongly than to the Ca2+–CaM complex (Kd = 3.3 μM) (Figures S5 and S6 in the Supporting Information, Table 1, and Chart 4). These experimental results allow us to consider two possibilities: the stimulation of the intracellular cell death pathway by the CaM-4 and ((Ca2+)n-CaM)-4 complexation (n = 0–4) and the inhibition of the Ca2+–CaM complex due to the occupation of the Ca2+ binding site by 4, resulting in intracellular Ca2+ overload. In this case, there might be unidentified target biomolecules that induce the release of Ca2+ from intracellular organelles such as ER. Our attempt at the crystallization of the complex of 4 with CaM in the presence and absence of Ca2+ for the X-ray crystallization analysis is now in progress to elucidate the molecular mechanism of paraptosis induced by 4 and to explain the different responses of cancer cells to IPHs, TFP, and other drugs.

-

(5)

The results of Western blot analysis revealed that 4 induces the upregulation of typical marker proteins of paraptosis and autophagy (LC3-II, Beclin-1, and Atg-12) through the MAPK signaling pathway (phosphorylation of p38, ERKs, and JNK 1), possibly by CaMKK and CaMKII activated by a (Ca2+-CaM)–4 complex, rather than the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and ER stress (Figure 9). However, the cell death of Jurkat cells by 4 was negligibly inhibited by an ERK inhibitor (SCH772984), a JNK inhibitor (SP600125), and an MEK inhibitor (U0126) (Figure 10), indicating that autophagy-mediated cell death is not the main pathway of cell death.

-

(6)

It is strongly suggested that the cell death induced by 4 is a paraptosis-like cell death, as evidenced by cytoplasmic vacuolization, which was also observed by a treatment with celastrol, which had been reported to induce Ca2+ overload and paraptosis in the literature.56,57 We therefore assessed the cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations induced by celastrol by flow cytometric analysis (Figure S7 in the Supporting Information). Interestingly, it was found that celastrol induces considerable increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations slowly (in ca. 1–5 h) with a small change in the mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration. These findings suggest that 4 and celastrol induce paraptosis-like cell death via different responses of intracellular Ca2+. It is unlikely that the influx of Ca2+ into mitochondria occurs from cytosol in the case of 4, according to negligible or weak enhancement of the emission of a cytosolic Ca2+ probe, Rhod-4 (Figure 5a,b). In addition, the cell death induced by 4 was negligibly inhibited by a Ca2+ chelator, BAPTA (Figure S4 in the Supporting Information). We assume that 4 induces the direct transportation of Ca2+ from ER to mitochondria and then loss of ΔΨm, resulting in paraptosis-like cell death accompanied by their vacuolization, although the roles of the interaction of 4 with CaM in these processes are yet to be studied.

-

(7)

It has very recently been reported that organometallic complexes such as ruthenium, copper, and titanium induce paraptosis.67−73 Although these metal complexes also induce cytoplasmic vacuolization through the damage of mitochondria, lysosome, and/or ER, a slightly longer time (3–24 h) is required to induce cell death of cancer cells. On the contrary, IPHs 4 and 5 quickly induce the paraptosis-like cell death of Jurkat cells, and the resulting dead cells can be detected by their strong green emission.

Chart 6.

Conclusions

In this manuscript, we have succeeded in synthesizing the amphiphilic IPH 4 containing cationic peptides at the 4′-position of the ppy ligands through glycolic acid units, which exhibits green emission for use in mechanistic studies of cell death. These newly synthesized IPHs exhibit a green emission, and their lifetimes are on the order of microseconds, due to phosphorescence from the excited triplet states, as supported by TD-DFT calculations. According to fluorescence microscopic observations and MTT assays, IPH 4 has more potent cytotoxicity against Jurkat cells (cancer cells) than 3a–d and 5, accompanied by membrane disruption, whereas negligible induction of cell death against IMR90 cells (normal cells) was observed. It was also found that 4 is uptaken into Jurkat cells more efficiently than our previous IPH 5. Detailed mechanistic studies allowed us to conclude that 4 induces the paraptosis-like cell death of Jurkat cells via a Ca2+-dependent pathway including the direct influx of Ca2+ from ER into mitochondria, the decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), and the vacuolization of the cytoplasm and intracellular organelle, although we do not exclude the possibility that stimulation of mitochondria by Ca2+ overload would induce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to promote PCD, as described in the literature,59,60,74 and another possibility is that 4 induces the degradation of actin, leading to the morphological change of Jurkat cells.32

The direct or close contact of the ER or the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) in the case of neural and muscle cells and mitochondria for the Ca2+ and lipid exchange and other cross-talk has been proposed not only in cancer cells but also in neural cells, muscle cells, and so on.74−81 To the best of our knowledge, 4 and its analogs such as 2b–d and 3b,c are the first class of molecules that induces direct Ca2+ transfer from the ER into mitochondria to activate the PCD mechanism of cancer cells. These results suggest that the control of Ca2+ homeostasis between ER and mitochondria could be one of the important targets in the chemotherapy of cancer and related diseases.

The information described in this manuscript would be useful for understanding the mechanisms of paraptosis and the future design and synthesis of amphiphilic anticancer agents in bioorganic chemistry, medicinal chemistry, and related research fields. More detailed mechanistic studies including cocrystallization of these IPHs with CaM and screening of more appropriate peptide sequences are currently in progress.

Experimental Section

General Information

All reagents and solvents were of the highest commercial quality and were used without further purification, unless otherwise noted. Anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were obtained by distillation from sodium benzophenone ketyl and calcium hydride, respectively. All aqueous solutions were prepared using deionized and distilled water. IrCl3·3H2O was purchased from KANTO CHEMICAL Co. 4-hydroxyphenylboronic acid was purchased from Oakwood Chemicals. 3-(4,5-Dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT), Rhod-2/AM, and Rhod-4/AM were purchased from Dojindo. NaN3 and CaCl2 were purchased from Nacalai tesque. 2-Bromopyridine and BAPTA/AM (tetrakis(acetoxymethyl)-1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetate) were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry. CCCP (Carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone) and DilC1(5) (1,1′,3,3,3′,3′-hexamethlyindodicarbocyanine iodide) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Calmodulin (human recombinant, BML-SE325) and necrostatin-1 were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences. The anticalmodulin antibody [EP799Y] and the goat antirabbit (secondary) IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 594) conjugate were purchased from Abcam. LysoTracker Red DND-99, MitoTracker Red CMXRos, and CellLight ER-RFP were purchased from Invitrogen. The caspase-3, ERK 1/2, p-ERK 1/2 antibody, and phalloidin–CruzFluor 594 conjugate were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. JNK 1, p-JNK 1, CHOP, LC3-I/II, Atg-12, Beclin-1, GAPDH, and HRP-conjugated secondary antirabbit and antimouse antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. SCH772984, SP600125, U0126, and celastrol were purchased from cayman. Concentrations of Ir complexes 4 in stock solutions (PBS: phosphate-buffered saline, 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)) were determined based on a molar extinction coefficient of 340 nm (ε340nm = (1.91 ± 0.03) × 104 M–1 cm–1) of 10 and 12 in Chart 2 that were characterized by elemental analysis. Stock solutions of all of the Ir complexes in PBS were used for measurements and cell assay and were stored at 0 °C prior to use. UV–vis spectra were recorded on JASCO V-630 and V-650 spectrophotometers at 25 °C. Emission spectra were recorded on JASCO FP-6200 and FP-6500 spectrofluorometers at 25 °C. IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer FT-IR spectrophotometer (Spectrum100) at room temperature. Melting points were measured using a Yanaco MP-J3 Micro Melting Point apparatus and are uncorrected. Luminescence imaging studies were performed using fluorescent microscopy (Biorevo, BZ-9000, Keyence; and Fluoview, FV-1000, Olympus). 1H (300 MHz) and 13C (75 MHz) NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL Always 300 spectrometer. Tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as an internal reference for the 1H and 13C NMR measurements in CDCl3, CD3OD, and DMSO. Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra were recorded on a Varian 910-MS spectrometer. The mass of some triscyclometalated Ir complexes was observed as [M]+ (rather than [M + H]+) in the ESI mode (Varian 910-MS). Lyophilization was performed with the freeze-dryer FD-5N (EYELA). Thin-layer chromatographies (TLCs) and silica gel column chromatographies were performed using the Merck Art. 5554 (silica gel) TLC plate and Fuji Silysia Chemical FL-100D, respectively. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) experiments were carried out using a system consisting of a PONM P-50 (Japan Analytical Industry Co., Ltd.), a UV–vis detector S-3740 (Soma Japan), a manual sample injector 7725i (Rheodyne), and an MDL-101 1 pen recorder (Japan Analytical Industry Co., Ltd.), equipped with two GPC columns, JAIGEL-1H and JAIGEL-2 (Japan Analytical Industry Co., Ltd.) (20φ × 600 mm, nos. A605201 and A605214). HPLC experiments were carried out using a system consisting of PU-980 intelligent HPLC pumps (JASCO, Japan), a UV-970 intelligent UV–visible detector (JASCO), a Rheodine injector (model no. 7125), and a Chromatopak C-R6A (Shimadzu, Japan). For analytical HPLC, a SenshuPak Pegasil ODS column (Senshu Scientific Co., Ltd.) (4.6φ × 250 mm, no. 07051001) was used. For preparative HPLC, a SenshuPak Pegasil ODS SP100 column (Senshu Scientific Co., Ltd.) (20φ × 250 mm, No. 1302014G) was used.

Synthesis

2-(4′-Hydroxyphenyl)pyridine (8)

2-Bromopyridine (3.8 g, 24 mmol), tripotassium phosphate (10 g, 48 mmol), and palladium acetate (0.25 g, 1.1 mmol) were added to a solution of 4-hydroxyphenylbornic acid (5.0 g, 36 mmol) in ethylene glycol (150 mL), and the reaction mixture was refluxed for 2 h in air. After the addition of 50 mL of H2O and 50 mL of brine, the reaction mixture was extracted with CHCl3 (200 mL × 3). The combined organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure, and the resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3) to afford 8 as a colorless solid (3.7 g, 90%). Mp 160–161 °C. IR (ATR): ν = 2590, 2482, 1609, 1593, 1561, 1525, 1468, 1423, 1383, 1310, 1289, 1269, 1246, 1182, 1157, 1100, 999, 968, 887, 837, 776, 744, 729, 717, 648, 626, 577, 552, 491, 474, 466, 407. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3/TMS): δ = 8.62 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.79–7.72 (m, 2H), 7.65 (dd, J = 8.1, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (td, J = 6.0, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H) ppm. 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3/TMS): δ = 158.0, 157.6, 148.9, 137.4, 128.6, 121.5, 120.8, 115.9 ppm. FAB (m/z) calcd. for. C11H10NO: [M + H]+ 172.0757; found 172.0761.

Ligand 9

To a solution of 8 (3.6 g, 21 mmol) in acetone (600 mL) were added ethyl bromoacetate (4.2 g, 25 mmol) and potassium carbonate (4.3 g, 31 mmol), and the reaction mixture was refluxed for 7.5 h. After cooling to room temperature, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. To the crude residue was added H2O (100 mL), and the resulting solution was extracted with CHCl3 (100 mL × 3). The combined organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure, and the resulting residue was recrystallized from hexane to afford 9 as beige needle-shaped crystals (3.8 g, 70%). Mp 89.0–91.0 °C. IR (ATR): ν = 2976, 2911, 1755, 1603, 1592, 1578, 1565, 1516, 1468, 1446, 1433, 1413, 1390, 1319, 1302, 1271, 1245, 1207, 1178, 1157, 1116, 1079, 1033, 1020, 1008, 988, 950, 839, 816, 776, 741, 717, 710, 640, 624, 590, 554, 513, 490, 434, 418. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3/TMS): δ = 8.65 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (dd, J = 6.9, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.74–7.64 (m, 2H), 7.18 (td, J = 5.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.67 (s, 2H), 4.28 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.30 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H) ppm. 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3/TMS): δ = 168.5, 158.4, 156.6, 149.3, 136.5, 132.8, 128.0, 121.4, 119.6, 114.6, 65.2, 61.2, 13.9 ppm. FAB (m/z) calcd. for. C15H16NO3: [M + H]+ 258.1125; found 258.1129. C15H15NO3: calcd. for C 70.02, H 4.85, N 7.08; found C 69.91, H 5.07, N 7.02.

fac-10

IrCl3·3H2O (0.26 g, 0.73 mmol) was added to a solution of 9 (5.6 g, 21.7 mmol) and Na2SO4 (3.1 g, 22 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane/H2O (1/1, 100 mL), and the reaction mixture was refluxed for 1 day. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was extracted with CHCl3 (100 mL × 2). The combined organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure, to which Na2SO4 (3.1 g, 22 mmol) and 1,4-dioxane/H2O (1/1, 100 mL) were added, and the resulting solution was then refluxed for 1 day. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was extracted with CHCl3 (100 mL × 2). The combined organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexane/AcOEt = 5/1 to 1/1), precipitated with hexane, and filtered to afford 10 as a yellow powder (0.51 g, 73%). Mp 105 °C (dec.). IR (ATR): ν = 3050, 2924, 2853, 1752, 1730, 1600, 1582, 1563, 1471, 1456, 1429, 1390, 1379, 1307, 1272, 1183, 1158, 1079, 1024, 936, 874, 851, 810, 771, 747, 725, 669, 647, 597, 532, 491 cm–1. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3/TMS): δ = 7.73 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 3H), 7.56–7.01 (m, 6H), 7.45 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 3H), 6.79 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 6.49 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 3H), 6.32 (s, 3H), 4.37 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 6H), 4.16 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 1.22 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H) ppm. 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3/TMS): δ = 169.2, 166.0, 163.5, 159.0, 146.9, 137.7, 135.8, 125.2, 120.8, 118.1, 107.6, 64.9, 60.9, 14.1 ppm. ESI/MS (m/z): calcd. for C45H42N3O9191Ir [M + Na]+ 982.2419; found 982.2415. C45H42IrN3O9·0.5H2O: calcd. for C 55.72, H 4.47, N 4.33; found C 55.71, H 4.42, N 4.21.

Ir Complex 11

Aqueous NaOH (15 mL) of 6 N was added to a solution of 10 (73 mg, 77 μmol) in THF (25 mL) and EtOH (25 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 16 h. After cooling to room temperature, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and 2 N aqueous HCl was added to adjust the pH to 1. The resulting residue was isolated on a filter and washed with H2O to afford 11 as a yellow solid (61 mg, 91%). Mp 235 °C (dec.). IR (ATR): ν = 2922, 1729, 1583, 1546, 1470, 1456, 1428, 1392, 1310, 1270, 1242, 1193, 1159, 1077, 1023, 1004, 852, 813, 772, 748, 724, 691, 667, 593, 562, 528, 496, 465, 441, 434, 419, 407 cm–1. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO/TMS): δ = 8.01 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 3H), 7.77–7.69 (m, 6H), 7.41 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H), 7.05 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H), 6.37 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 3H), 6.21 (s, 3H), 4.38 (s, 6H) ppm. 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO/TMS): δ = 170.2, 1655.1, 164.5, 162.4, 146.6, 137.6, 136.7, 125.5, 122.2, 121.7, 118.5, 104.6, 63.8 ppm. ESI/MS (m/z): calcd. for C39H30N3O9191Ir [M]+ 875.1583; found 875.1588.

Ir Complex 12

N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) (0.11 g, 0.86 mmol), PyBOP (0.23 g, 0.45 mmol), and 11 (64 mg, 73 μmol) were added to a solution of mono-Boc-protected octamethylenediamine (0.21 g, 0.86 mmol) in distilled DMF (5 mL). The resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 17.5 h and then concentrated under reduced pressure. The remaining residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 150/1) and GPC (CHCl3) to afford 12 as a yellow powder (76 mg, 67%). Mp 105 °C (dec.). IR (ATR): ν = 3398, 3330, 2974, 2927, 2855, 1705, 1667, 1589, 1534, 1471, 1456, 1441, 1427, 1392, 1364, 1307, 1268, 1250, 1200, 1164, 1064, 1004, 878, 769, 748, 725, 694, 662, 604, 584, 546, 530, 515, 451, 410 cm–1. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3/TMS): δ = 7.81 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 3H), 7.64–7.59 (m, 6H), 7.16 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 3H), 6.75 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H), 6.54 (dd, J = 4.5, 2.4 Hz, 3H), 6.26 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 3H), 4.58 (brs, 3H), 4.21 (d, J = 14 Hz, 3H), 3.98 (J = 14 Hz, 3H), 3.08–3.02 (m, 6H), 2.54–2.42 (m, 3H), 1.45 (s, 30H), 1.40–1.33 (m, 6H), 1.26 (s, 6H), 1.17–1.10 (m, 6H), 1.07–1.02 (m, 6H), 0.97–0.81 (m, 6H), 0.68–0.53 (m, 9H) ppm. 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3/TMS): δ = 166.8, 165.4, 162.8, 157.6, 155.9, 146.3, 138.5, 136.2, 125.3, 123.9, 121.0, 118.8, 102.8, 78.9, 65.8, 40.5, 37.7, 29.9, 29.0, 28.8, 28.6, 28.4, 26.6, 26.5 ppm. ESI/MS (m/z): calcd. for C78H108N9O12Na191Ir [M + Na]+ 1576.7616; found 1576.7617. C78H108IrN9O12·0.3CHCl3: calcd. for C 59.08, H 6.86, N 7.92; found C 59.04, H 6.90, N 7.86.

Ir Complex 13

A mixture of TMSCl (22 mg, 0.20 mmol) and NaI (31 mg, 0.21 mmol) in CH3CN (2 mL) was added to a suspension of Boc-protected 12 (11 mg, 6.8 μmol) in CH3CN (2 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 min and then sonicated. The insoluble residue was collected by centrifugation and washed with CH3CN to give 13 as the HI salt (7.7 mg, 69%). Mp 185 °C. IR (ATR): ν = 3386, 2924, 2853, 1646, 1587, 1541, 1470, 1456, 1426, 1393, 1361, 1307, 1268, 1199, 1161, 1065, 1024, 1004, 879, 809, 773, 749, 692, 667, 591, 545, 530, 488, 480, 453, 446, 435, 427, 419, 412 cm–1. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD/TMS): δ = 7.78 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 3H), 7.75–7.66 (m, 6H), 7.29 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 3H), 7.18 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 3H), 6.92 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H), 6.51 (dd, J = 8.7 Hz, 3H), 4.28 (t, J = 15 Hz, 3H), 4.01 (d, J = 15 Hz, 3H), 2.47–2.38 (m, 3H), 1.65–1.55 (m, 6H), 1.35–1.22 (m, 12H), 1.16–1.07 (m, 6H), 1.00–0.87 (m, 9H), 0.77–0.63 (m, 6H), 0.56–0.48 (m, 3H), 0.42–0.36 (m, 3H) ppm. ESI/MS (m/z): calcd. for C63H85N9O6191Ir [M + H]+ 1254.6223; found 1254.6230.

Ir Complex 4

DIEA (19 mg, 0.14 mmol), PyBOP (67 mg, 0.13 mmol), and protected KKKGG peptide (28 mg, 31 μmol) were added to a solution of 13 (11 mg, 6.5 μmol) in freshly distilled DMF (2 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 h and then concentrated under reduced pressure. The remaining residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH = 15/1 to 10/1) to afford the protected compound. A mixture of TMSCl (69 mg, 0.63 mmol) and NaI (0.10 g, 0.66 mmol) in CH3CN/MeOH (1/1, 3 mL) was added to a solution of the protected compound in CH3CN/MeOH (1/1, 3 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h and then concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was dissolved in MeOH and precipitated with Et2O. The insoluble compound was collected by centrifugation and washed with Et2O. The resulting residue was purified by RP-HPLC (CH3CN (0.1% TFA)/H2O (0.1% TFA) = 20/80 to 50/50 (30 min), tr = 23 min, 8.0 mL/min) and lyophilized to afford 4 as a yellow solid (3.0 mg, 11% as TFA salt). IR (ATR): ν = 3061, 2934, 1659, 1591, 1546, 1472, 1430, 1271, 1181, 1128, 1072, 958, 882, 839, 800, 773, 748, 722, 667, 598, 519, 444, 426, 435, 416, 407 cm–1. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD/TMS): δ = 7.94 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 3H), 7.70–7.65 (m, 6H), 7.49 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 3H), 6.50 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 3H), 6.37 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 3H), 4.37–4.24 (m, 12H), 3.91–3.85 (m, 15H), 3.16–3.07 (m, 15H), 3.04–2.95 (m, 21H), 1.93–1.83 (m, 15H), 1.70–1.61 (m, 30H), 1.49–1.33 (39H), 1.26–1.12 (m, 30H) ppm. ESI/MS (m/z): calcd. for C129H213N33O21191Ir [M + 3H]3+ 917.2058; found 917.2068.

The Ir complex 5 was prepared using a procedure similar to that for 4.

Ir Complex 5

A yellow powder (25%). IR (ATR): ν = 3267, 3062, 2931, 2861, 1663, 1532, 1473, 1428, 1303, 1261, 1197, 1178, 1127, 1071, 1029, 923, 894, 837, 798, 783, 750, 721, 597, 517, 442, 418, 406 cm–1. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD/TMS): δ = 8.03 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 3H), 7.76–7.72 (m, 6H), 6.96 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H), 6.73 (s, 3H), 4.39–4.26 (m, 6H), 3.97–3.95 (m, 9H), 3.84 (s, 6H), 3.20–3.18 (m, 9H), 2.99–2.91 (m, 15H), 2.12 (s, 9H), 1.93–1.81 (m, 12H), 1.78–1.65 (m, 24H), 1.58–1.53 (m, 30H), 1.36–1.29 (m, 24H) ppm. ESI/MS (m/z): calcd. for C129H216N33O18191Ir [M + 3H]3+ 901.2119; found 901.2118.

Measurements of UV–Vis Absorption and Luminescence Spectra

UV–vis spectra were recorded on JASCO V-630 and V-650 UV–vis spectrophotometers, and emission spectra were recorded on a JASCO FP-6200 or FP-6500 spectrofluorometer with excitation and emission slit widths at 5 nm at 25 °C. Sample solutions in quartz cuvettes equipped with Teflon septum screw caps were degassed by Ar bubbling through the solution for 10 min prior to making the luminescence measurements. The luminescence quantum yields (Φ) were determined by comparison with the integrated corrected emission spectrum of quinine sulfate (Φ = 0.55 in 0.1 M H2SO4)82,83 when excited at 366 nm. In the case of excitation at 425 nm, Φ values were determined by comparison with Ir(tpy)31 (Φ = 0.5 in CH2Cl2).6,29Equation 1 was used for calculating the emission quantum yields, in which Φs and Φr denote the quantum yields of the sample and reference compound, respectively, and ηs and ηr are the refractive indexes of the solvents used for the measurements of the sample and reference, respectively (η: 1.33 for H2O, 1.42 for CH2Cl2, and 1.48 for DMSO). As and Ar denote the absorbance of the sample and reference, respectively.

| 1 |

The luminescence lifetimes of sample solutions in degassed aqueous solutions at 298 K were measured on a TSP1000-M-PL (Unisoku, Osaka, Japan) instrument using THG (355 nm) of Nd:YAG laser, Minilite I (Continuum, CA) as the excitation source. The signals were monitored with an R2949 photomultiplier. Data were analyzed using the nonlinear least-squares procedure.

Theoretical Calculations

Density function theory (DFT) calculations were carried out using the Gaussian09 program (PBE1PBE functional, the LanL2DZ basis set for Ir and the 6-31G basis set for H, C, O, N atoms).30 TD-DFT calculations were carried out based on optimized ground-state geometries using the same functional and basis set. The molecular orbitals were visualized using Jmol software (an open-source Java viewer for chemical structures in 3D, http://www.jmol.org/).

Cell Culture

Jurkat cells were cultured in an RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), l-glutamine, (2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinyl]ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH = 7.5), penicillin/streptomycin, and monothioglycerol (MTG) in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C.

MTT Assay

Jurkat cells (2.0 × 105 cells/mL, 100 μL) were incubated in a 10% FBS RPMI 1640 medium containing Ir complexes under 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h in 96-well plates (BD Falcon); 0.5% MTT reagent in PBS (10 μL) was then added to the cells. After incubation at 37 °C for 4 h, a formazan lysis solution (10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in 0.01 N HCl) (100 μL) was added, and the resulting solution was incubated overnight under the same conditions, followed by measurement of the absorbance at 570 nm using a microplate reader (BIO-RAD).

Fluorescent Microscopy Studies of Jurkat Cells with Ir Complexes

Jurkat cells (2.0 × 105 cells/mL, 100 μL) were incubated in the absence or the presence of Ir complexes (25 μM) in an RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS for 1 h under 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After the incubation, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS containing 0.1% NaN3 and 0.5% FBS and observed by fluorescent microscopy (Biorevo, BZ-9000, Keyence) using a Greiner CELLview petri dish (35 × 10 mm2). Emission images were observed by an FF01 filter (excitation 377 nm, emission 520 nm).

Measurement of Intracellular Uptake of Ir Complexes into Jurkat Cells Evaluated by ICP-MS

Jurkat cells (1.5 × 106 cells) were treated with IPHs such as 4, 3c, 5, and 2c (25 μM) for 1 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 (n = 3). Then, cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with 0.5 mL of HNO3 (70%) overnight at 4 °C. On the next day, the supernatant was collected by centrifugation (15 000 rpm, 4 °C, 10 min) and transferred to a new 15 mL centrifuge tube. The supernatant was diluted with fresh miliQ water (9.5 mL) and filtrated. The measurement of the iridium atom was determined by ICP-MS using these filtrated solutions.

Fluorescent Microscopy Studies of Jurkat Cells with 4 in the Presence of Inhibitors

Jurkat cells (1.0 × 106 cells/mL, 100 μL) in an RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS were pretreated with the inhibitor Z-VAD-fmk (15 μM), CCCP (40 μM), Necrostatin-1 (30 μM), 3-methyladenine (3-MA) (5 mM), or trifluoperazine (10 μM) under 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 30 min, and 4 (25 μM) was then added to the cell suspension. After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS containing 0.5% FBS and 0.1% NaN3 and observed by fluorescent microscopy (Biorevo, BZ-9000, Keyence) using a Greiner CELLview petri dish (35 × 10 mm2). Emission images were observed by an FF01 filter (excitation 377 nm, emission 520 nm).

Cytosolic and Mitochondrial Ca2+ Measurement

To measure the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration, Jurkat cells were incubated with Rhod-4/AM (5 μM) or Rhod-2/AM (5 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C, respectively. The loaded cells in the RPMI 1640 medium were plated on a Greiner CELLview petri dish (35 × 10 mm2), and the change in the fluorescent intensity of Rhod-4 or Rhod-2 after treatment with Ir complexes (50 μM) was then observed by fluorescent microscopy (excitation 540 nm, emission 605 nm, TRITC filter). Fluorescent intensities of Rhod-4 and Rhod-2 were analyzed by BZ analyzer II (Keyence).

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Jurkat Cells Stained with Rhod-2 or Rhod-4

Jurkat cells (2.0 × 105 cells) were preincubated with Rhod-2/AM (5 μM, 100 μL) or Rhod-4/AM (5 μM, 100 μL) in a 10% FBS RPMI 1640 medium under 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 30 min and then treated with 4 (50 μM, 100 μL) for a given incubation time (2–60 min), immediately after which the cells were suspended in 300 μL of RPMI 1640 medium and then analyzed on a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur cytometer, Becton), and the data were analyzed on FlowJo software (FlowJo, LCC).

Measurement of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm) of Jurkat Cells Treated with 4

The measurements of the mitochondrial membrane potential were conducted using DilC1(5) (1,1′,3,3,3′,3′-hexamethlyindodicarbocyanine iodide).36 Jurkat cells (2.0 × 105 cells) were preincubated in the presence or absence of CCCP (40 μM, 100 μL) in a 10% FBS RPMI 1640 medium under 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by the incubation with 4 (25 μM, 100 μL) for 1 h. After the treatment of DilC1(5) (500 nM, 100 μL) for 30 min, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS containing 0.1% NaN3 and 0.5% FBS twice and then observed by confocal microscopy (Fluoview, FV-1000, Olympus) using a Greiner CELLview petri dish (35 × 10 mm2). Excitation was 405 nm for 4 and 635 nm for DilC1(5).

Immunofluorescent Microscopy of Jurkat Cells with a CaM Antibody in the Presence of 4

Jurkat cells (1.0 × 106 cells) were incubated with 4 (25 μM) in an RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 1 h. After the incubation, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS containing 0.1% NaN3 and 0.5% FBS. After fixing by treatment with cold MeOH at −30 °C for 10 min, the cells were washed with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS and then permeabilized by treatment with 0.3% Tween 20 in PBS at room temperature for 10 min and washing twice with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS. After blocking the cells by the treatment with 0.1% BSA in 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS at room temperature for 45 min and washing with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS, the cells were incubated with the CaM antibody (primary antibody) at a dilution of 1/100 at room temperature for 2 h and then washed three times with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS. Finally, a goat antirabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 594) at a dilution of 1/400 was used as a secondary antibody, and the cells were then washed twice with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS and twice with PBS. They were observed by confocal fluorescent microscopy (Fluoview, FV-1000, Olympus) using a Greiner CELLview petri dish (35 × 10 mm2). Excitation was 405 nm for 4 and 559 nm for the secondary antibody. Emissions from 470–530 nm for 4 and 610–680 nm for the secondary antibody were used.

Fluorescent Confocal Microscopy Studies of Jurkat Cells Treated with LysoTracker Red and MitoTracker Red in the Presence of 4

Jurkat cells (3.0 × 105 cells) were incubated with Ir complexes (25 μM) in an RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS containing LysoTracker Red (500 nM) or MitoTracker Red (100 nM) at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 1 h. After the incubation, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS containing 0.1% NaN3 and 0.5% FBS. After fixation by treatment with cold MeOH at −30 °C for 10 min, the cells were washed with PBS twice and observed by confocal fluorescent microscopy (Fluoview, FV-1000, Olympus) using a Greiner CELLview petri dish (35 × 10 mm2). Excitation was 405 nm for Ir complexes and 559 nm for LysoTracker Red and MitoTracker Red. Emissions from 470–530 nm for 4 and 580–660 nm for LysoTracker Red and MitoTracker Red were used.

Fluorescent Confocal Microscopy Studies of Jurkat Cells Treated with Phalloidin in the Presence of 4

Jurkat cells (3.0 × 105 cells) were incubated with 4 (25 μM) in an RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 1 h. After the incubation, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS containing 0.1% NaN3 and 0.5% FBS. After fixation by treatment with cold MeOH at −30 °C for 10 min, the cells were washed with PBS twice and treated with phalloidin at a dilution of 1:1000 in PBS at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 1 h. After washing with PBS twice, the cells were observed by confocal fluorescent microscopy (Fluoview, FV-1000, Olympus) using a Greiner CELLview petri dish (35 × 10 mm2). Excitation was 405 nm for 4 and 559 nm for phalloidin. Emissions from 470 to 530 for 4 and 580–660 nm for phalloidin were used.

Analysis by 27 MHz Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM)

QCM analysis was performed on an Affinix-Q4 apparatus (Initium Inc., Japan). A clean Au (4.9 mm2) electrode equipped on the quartz crystal was incubated with an aqueous solution of 3,3′-dithiodipropionic acid (3 mM, 5 μL) at room temperature for 30 min. After washing with H2O, the surface was activated by the treatment with a mixture of EDC·HCl (0.26 M) and NHS (0.44 M) for 30 min, washed with H2O, and then treated with CaM (100 μg/mL, 5 μL) at room temperature for 30 min. After washing with PBS, an aqueous solution of 1 M ethanolamine (5 μL) was added as a blocking reagent. After washing with PBS, the QCM cell was filled with PBS (500 μL). After this, an aqueous solution of CaCl2 (40 mM) was added to adjust the final Ca2+ concentration in the QCM cell to 80 μM for the QCM experiments in the presence of Ca2+. The apparent binding constants (Kapp) for Ir complexes with CaM in PBS were calculated from the decrease in frequency (ΔF). The nonspecific response was subtracted from the frequency decrease curve to obtain the apparent complexation constants (Kapp) and the dissociation constants (Kd (=1/Kapp)).

Western Blot Analysis

Jurkat cells (3.0 × 106 cells) were treated with Ir complexes and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After the treatment, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and proteins were extracted by RIPA buffer (Nacalai Tesque, Japan). The extracted proteins were quantified by the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). Then, 50 μg (per well) of proteins was used for SDS-PAGE (7.5–15%) (BioRad). After SDS-PAGE, the gel was transferred to a poly(vinylidene fluoride) membrane (Merck Millipore, Germany) using a semidry blotter (BioRad). The membrane was blocked with Blocking One solution (Nacalai Tesque, Japan) for 30 min at room temperature. After blocking, the membrane was washed three times with TBST (5 min each time) and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at a dilution of 1/1000 in a signal enhancer HIKARI-solution A (Nacalai Tesque, Japan). On the next day, the membrane was washed three times with TBST and incubated for 60 min at room temperature with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody such as antirabbit or antimouse at a dilution of 1/200 or 1/1000 in signal enhancer HIKARI-solution B. The protein signal was spotted by Chemi-Lumi One Ultra solution (Nacalai Tesque, Japan) using the ChemiDoc MP system (BioRad).

MTT Assay of Jurkat Cells in the Presence of Inhibitors

Jurkat cells (1.0 × 105 cells/mL, 100 μL) were preincubated in a 10% FBS RPMI 1640 medium containing inhibitors under 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 30 min and then treated with 4 (25 μM) for 1 h in 96-well plates (BD Falcon). After incubating the cells at 37 °C for 4 h, 0.5% MTT reagent in PBS (10 μL) was added to the cells, after which a formazan lysis solution (10% SDS in 0.01 N HCl) (100 μL) was added and the resulting solution incubated overnight under the same conditions, followed by measurement of the absorbance at 570 nm using a microplate reader (BIO-RAD).

Methylene Blue Staining and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis of Jurkat Cells Treated with 4

Jurkat cells (3.0 × 106 cells) were incubated with 4 (25 μM) in an RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 1 h. After the incubation, the cells were collected by centrifugation and washed with ice-cold PBS containing 0.1% NaN3 and 0.5% FBS twice and then prefixed with glutaraldehyde (2.5%) at 4 °C for 40 min and washed with ice-cold PBS twice. Postfixing was conducted with osmium tetroxide (1%) at 4 °C for 30 min. After washing, the cells were included in an agarose gel and dehydrated with 50–100% anhydrous EtOH. Embedding of the cells in Poly 812 resin (Nisshin EM Co. Ltd.) was conducted at 60 °C for 3 days. The resin was sliced with a glass knife (150 nm thickness) on an ultramicrotome (EM UC6, Leica), and the sections were stained with methylene blue for microscopic observation on a microscope (BX51, Olympus) (Figure 11). For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation, the sliced samples (ca. 100 nm thickness) were stained with an EM stainer (Nisshin EM Co. Ltd.) and observed on a TEM instrument (H-7650, HITACHI) with electron irradiation at 100 kV (Figure 12).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan (Nos. 22390005, 24659011, and 24640156 for S.A.), the Uehara Memorial Foundation for S.A., the scholarship of International Association for the Exchange of Students for Technical Experience (IAESTE) for A.M., the “Academic Frontiers” project for private universities: a matching fund study from MEXT, and the TUS (Tokyo University of Science) fund for strategic research areas. We wish to thank Prof. Takeshi Nakamura (Research Institute for Biomedical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science), Prof. Kohei Soga (Faculty of Industrial Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Science), Prof. Hideki Sakai (Faculty of Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Science), Dr. Rikio Niki (Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science), and Dr. Toshinari Ichihashi (Research Institute for Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Science) for the kind help in confocal microscopic and TEM observation. We would also wish to express our sincere appreciation to Prof. Toshiyuki Kaji and Dr. Eiko Yoshida (Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science) for providing a normal cell line IMR90. We also wish to thank Ms. Fukiko Hasegawa, Ms. Noriko Sawabe, and Ms. Yuki Honda (Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science) for measurement of MS spectrometry, NMR, and elemental analysis, respectively.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c00337.

Photophysical properties of Ir complexes (1a, 1c, 3c, 4, 5, 10, and 15) (Figure S1 and Table S1), DFT calculations of 10 and 15 (Figure S2 and Table S2), typical confocal microscopic observations of Jurkat cells treated with MitoTracker Green and Rhod-2/AM (Figure S3), effect of BAPTA/AM on the cell death induced by 4 (Figure S4), 27 MHz QCM analysis of CaM with 3c, 4, 5, and anti-CaM antibody (Figures S5 and S6, and Table S3), flow cytometric analysis of Jurkat cells treated with celastrol (Figure S7), and chemical structures of inhibitors and fluorescent probe (Charts S1–S4) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Dedeian K.; Djurovich P. I.; Garces F. O.; Carlson G.; Watts R. J. A new synthetic route to the preparation of a series of strong photoreducing agents: fac-tris-ortho-metalated complexes of iridium(III) with substituted 2-phenylpyridines. Inorg. Chem. 1991, 30, 1685–1687. 10.1021/ic00008a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo A. B.; Alleyne B. D.; Djurovich P. I.; Lamansky S.; Tsyba I.; Ho N. N.; Bau R.; Thompson M. E. Synthesis and characterization of facial and meridional tris-cyclometalated iridium(III) complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 7377–7387. 10.1021/ja034537z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamigni L.; Barbieri A.; Sabatini C.; Ventura B.; Barigelletti F. Photochemistry and photophysics of coordination compounds: iridium. Top. Curr. Chem. 2007, 281, 143–203. 10.1007/128_2007_131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omae I. Application of five-membered ring products of cyclometalation reactions as sensing materials in sensing devices. J. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 823, 50–75. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2016.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot A.; Schnider P.; Pfaltz A. Enantioselective hydrogenation of olefins with iridium-phosphonodihydrooxazole catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 2897.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster T. P.; Blakemore J. D.; Schley N. D.; Incarvito C. D.; Hazari N.; Brudvig G. W.; Crabtree R. H. An iridium(IV) species, [Cp *Ir(NHC)Cl]+, related to a water-oxidation catalyst. Organometallics 2011, 30, 965–973. 10.1021/om101016s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara T.; Hosaka M.; Terata M.; Ichikawa K.; Murayama S.; Tanaka A.; Mori M.; Itabashi H.; Takeuchi T.; Tobita S. Intracellular and in vivo oxygen sensing using phosphorescent Ir(III) complexes with a modified acetylacetonato ligand. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 2710–2717. 10.1021/ac5040067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbricht C.; Beyer B.; Friebe C.; Winter A.; Schubert U. S. Recent developments in the application of phosphorescent iridium(III) complex systems. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 4418–4441. 10.1002/adma.200803537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobita S.; Yoshihara T. Intracellular and in vivo oxygen sensing using phosphorescent iridium(III) complexes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 33, 39–45. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara T.; Hirakawa Y.; Hosaka M.; Nangaku M.; Tobita S. Oxygen imaging of living cells and tissues using luminescent molecular probes. J. Photochem. Photobiol., C 2017, 30, 71–95. 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2017.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu K.; Liu Y.; Huang H.; Liu C.; Zhu H.; Chen Y.; Ji L.; Chao H. Biscyclometalated iridium(III) complexes targeted mitochondria or lysosomes by regulating the liphophilicity of the main ligands. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 16144–16147. 10.1039/C6DT03328H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo K. K.-W.; Tso K. K.-S. Functionalization of cyclometalated iridium(III) polypyridine complexes for the design of intracellular sensors, organelle-targeting imaging reagents, and metallodrugs. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2015, 2, 510–524. 10.1039/C5QI00002E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- You Y. Molecular dyad approaches to the detection and photosensitization of singlet oxygen for biological applications. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 7131–7135. 10.1039/C6OB01186A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvadó I.; Gamba J.; Montenegro J.; Martínez-Costas J. M.; Brea M. I.; Loza M.; Vázquez López I.; Vázquez M. E. Membrane disrupting iridium(III) oligocationic organometallopeptides. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 11008–11011. 10.1039/C6CC05537K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao R.; Jia J.; Ma X.; Zhou M.; Fei H. Membrane localized iridium(III) complex induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in human cancer cells. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 3636–3644. 10.1021/jm4001665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X. D.; Kong X.; He S. F.; Chen J. X.; Sun J.; Chen B. B.; Zhao J. W.; Mao Z. W. Cyclomatalated iridium(III)-guanidinium complexes as mitochondria-targeted anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 138, 246–254. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkankit C. C.; Marker S. C.; Knopf K. M.; Wilson J. J. Anticancer activity of complexes of the third row transition metals, ruthenium, osmium, and iridium. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 9934–9974. 10.1039/C8DT01858H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki S.; Matsuo Y.; Ogura S.; Ohwada H.; Hisamatsu Y.; Moromizato S.; Shiro M.; Kitamura M. Regioselective Aromatic Substitution Reactions of Cyclometalated Ir(III) Complexes: Synthesis and Photochemical Properties of Substituted Ir(III) Complexes that Exhibit Blue, Green, and Red Color Luminescence Emission. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 806–818. 10.1021/ic101164g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisamatsu Y.; Aoki S. Design and Synthesis of Blue-Emitting Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Complexes Based on Regioselective Functionalization. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 5360–5369. 10.1002/ejic.201100755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Hisamatsu Y.; Tamaki Y.; Ishitani O.; Aoki S. Design and Synthesis of Heteroleptic Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Complexes Containing Quinoline-Type Ligands that Exhibit Dual Phosphorescence. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 3829–3843. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moromizato S.; Hisamatsu Y.; Suzuki T.; Matsuo Y.; Abe R.; Aoki S. Design and Synthesis of a Luminescent Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Complex Having N,N-Diethylamino Group that Stains Acidic Intracellular Organelles and Induces Cell Death by Photoirradiation. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 12697–12706. 10.1021/ic301310q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa A.; Hisamatsu Y.; Moromizato S.; Kohno M.; Aoki S. Synthesis and Photochemical Properties of pH Responsive Tris-Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Complexes that Contain a Pyridine Ring on the 2-Phenylpyridine Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 409–422. 10.1021/ic402387b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kando A.; Hisamatsu Y.; Ohwada H.; Itoh T.; Moromizato S.; Kohno M.; Aoki S. Photochemical Properties of Red-Emitting Tris(Cyclometalated) Iridium(III) Complexes Having Basic and Nitro Groups and Application to pH Sensing and Photoinduced Cell Death. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 5342–5357. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]