Abstract

Objective:

Rapid development in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) has led to changes in diet that have outpaced water and sanitation improvements, contributing to a dual burden of overweight and noncommunicable disease risk factors (OWT/NCD) and undernutrition and infectious disease symptoms (UND/ID) within individuals and households. Yet, little work has examined the joint impact of water and food exposures on the development of the dual burden.

Methods:

We use data from Ecuador’s nationally-representative Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición (ENSANUT-ECU) to test whether water access and quality and diet quality and security are associated with OWT/NCD and UND/ID among 1119 children and 1582 adults in Galápagos. Adjusted multinomial and logistic models were used to test the separate and joint associations between water and food exposures and the dual burden and its components at the individual and household levels.

Results:

The prevalence of the dual burden of OWT/NCD and UND/ID was 16% in children, 33% in adults, and 90% in households. Diet quality was associated with a higher risk of dual burden in individuals and households. Mild food insecurity was positively associated with the risk of dual burden at the household level. No water variable separately predicted the dual burden. Joint exposure to poor water access and food insecurity was associated with greater odds of dual burden in households.

Conclusion:

Our results suggest that unhealthy diets and poor water quality contribute to the dual burden at the individual and household levels. Addressing both food and water limitations is important in LMIC.

Keywords: dual burden, water quality, water access, household food security, Ecuador

Rapid economic development in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) has contributed to increasing rates of obesity and cardiometabolic disease in children and adults, as individuals are exposed to new high-fat, energy-dense diets, more sedentary lifestyles and differing disease exposures (Monteiro, Conde, & Popkin, 2004; Popkin, 2006; Popkin, Adair, & Ng, 2012). At the same time, decreases in undernutrition, assessed through the prevalence of stunting and/or micronutrient deficiencies, have not kept pace, particularly among poorer or more rural individuals (Kosaka & Umezaki, 2017). This co-occurrence of overnutrition and cardiometabolic disease and undernutrition and infectious disease, termed the “dual burden,” has come to characterize LMIC settings (Perez-Escamilla et al., 2018). In Latin American countries (LAC), the nutritional dual burden is particularly common at the national and household levels (Rivera, Pedraza, Martorell, & Gil, 2014). A recent synthesis found that two-thirds or more of women in seven reviewed countries were overweight, while anemia and stunting were found at moderate to very high levels. Similar patterns can be seen in Ecuador where, on the national level, rates of overweight and obesity are high among adults (38% in women and 44% in men), child stunting remains high (25.3%) and micronutrient deficiencies of iron and zinc are common (Freire, Silva-Jaramillo, Ramírez-Luzuriaga, Belmont, & Waters, 2014).

The heterogenous nature of economic development and access to the new foods and lifestyles that accompany it results in nutritional status and disease burdens that also vary within households (Doak, Adair, Bentley, Monteiro, & Popkin, 2005; Kapoor & Anand, 2002; Tzioumis & Adair, 2014). Though this research is sometimes criticized as stemming from a statistical artifact (Corsi, Finlay, & Subramanian, 2011; Dieffenbach & Stein, 2012), the dual pattern of overweight mothers and stunted or anemic children has been documented in a number of settings in LAC, including Ecuador (Barquera et al., 2007; Freire, Waters, Rivas-Marino, & Belmont, 2018; Lee, Houser, Must, de Fulladolsa, & Bermudez, 2010). Such differences in the patterning of malnutrition within households may reflect shared underlying determinants of poor nutritional status, including limited access to healthy foods, that when coupled with differences in individual nutrient needs and different dietary and physical activity behaviors, can result in different nutritional outcomes (Tzioumis & Adair 2014). Importantly, research into the socioeconomic patterning of dual burden households in LAC suggests that the combination of overweight mothers and stunted children is characteristic of the most disadvantaged population groups, such as poor, rural and indigenous households (Lee et al., 2010). Thus, the co-occurrence of under- and over-nutrition can pose an economic challenge for already disadvantaged households as they deal with these dual health problems and for policy makers and practitioners designing interventions to simultaneously alleviate under- and over-nutrition (Roemling & Qaim, 2013).

Along with these household level impacts, the rapidity of social and economic change in many LAC also means that individuals may also be at risk for the dual burden (Fernald & Neufeld, 2007; Varela-Silva et al., 2012). Exposure to infectious morbidity, micronutrient deficiencies, and stunting in childhood due to exposure to unclean water and nutrient-poor diets is associated with subsequent greater adiposity (Sawaya, Martins, Hoffman, & Roberts, 2003), elevated blood pressure (Adair & Cole, 2003; Adair et al., 2009; Gaskin, Walker, Forrester, & Grantham-McGregor, 2000) and impaired insulin sensitivity (González-Barranco & Ríos-Torres, 2004) in adulthood when excess energy becomes available. Increasing evidence also documents that simultaneous exposure to pathogens and high-fat processed foods may interact to contribute to the co-occurrence of OWT/NCD and UND/ID in children by inducing subclinical environmental enteropathy and inflammation (Ding & Lund, 2011; Jones, Thitiri, Ngari, & Berkley, 2014; Kau, Ahern, Griffin, Goodman, & Gordon, 2011).

Given the prevalence of the dual burden at the household and individual levels, the differential susceptibility of individuals within the same households, the potential for health consequences across the lifespan, and the impacts on household health and economic well-being, understanding the determinants of the dual burden for households and individuals is critical. Much work has established that socioeconomic and environmental changes associated with urbanization and globalization have contributed to the nutrition transition in LMIC, where traditional diets are being replaced by energy-dense, higher-fat and processed foods (Monteiro et al., 2004; Popkin et al., 2012). These diets, while high in energy tend to have low nutrient quality, potentially contributing to both overweight, through excess energy intake, and micronutrient malnutrition (Darmon & Drewnowski, 2015; Drewnowski & Specter, 2004).

Along with diet quality, food security is an important factor contributing to the dual burden and its components of overweight and undernutrition. In LMIC, household food insecurity (HFI) has traditionally been associated with inadequate dietary intake, poor diet quality, infection, anemia, and growth faltering in children (Anderson, Tegegn, Tessema, Galea, & Hadley, 2012; Campbell et al., 2011; Hackett, Melgar-Quiñonez, & Álvarez, 2009; Schmeer & Piperata, 2017). However, as in high-income countries, where a large literature links HFI to obesity (e.g. Dinour, Bergen & Yeh, 2007; Gorton, Bullen, & Mhurchu, 2010; Seligman, Laraia, & Kushel, 2010; Townsend, Peerson, Love, Achterberg, & Murphy, 2001) particularly among women (Martin & Lippert, 2012), HFI has also been associated with overweight, obesity, and cardiometabolic disease in LMIC (Jones et al., 2018; Pérez-Escamilla, Villalpando, Shamah-Levy, & Méndez-Gómez Humarán, 2014). While less research has examined the potential role of HFI in shaping the dual burden of malnutrition (Jones et al., 2018; Jones, Mundo‐Rosas, Cantoral, & Levy, 2016), HFI may be particularly important in this context, shaping both food choice and psychological responses to perceived threats of food shortages in ways that may increase the development of obesity and NCD (Seligman, Laraia, & Kushel, 2010). Studies of HFI in LAC suggest that mild-moderate episodic or cyclical food insecurity is associated with poorer diet quality thorough reduced diversity, less frequent consumption of fruits, vegetables, dairy products, meat, and fish (Weigel & Armijos, 2015), foods which tend to be more costly, and higher consumption of processed foods (Weigel, Armijos, Racines, Cevallos, & Castro, 2016).

These changes in diet have outpaced water and sanitation improvements in many LAC (Willaarts, Garrido, Soriano, Molano, & Fedorova, 2014), which suffer from limited water access and poor water quality. Contaminated drinking water is associated with undernutrition and increased morbidity from infectious conditions, including diarrhea and urinary tract infections (Günther & Fink, 2010; Hunter, MacDonald, & Carter, 2010; Vilcins, Sly, & Jagals, 2018). Contaminated water also plays a role in the development of small intestine bacterial overgrowth and subclinical environmental enteropathy, both of which can contribute to underweight and stunting in children (Donowitz & Petri Jr, 2015; Brown, Cairncross, Ensink, 2013) and micronutrient deficiencies in children and adults (Guerrant, DeBoer, Moore, Scharf, & Lima, 2013).

Water quality may also influence the risk of overweight and obesity, albeit indirectly. Studies have documented that in both high income and LMIC, perceptions that drinking water is contaminated or of poor quality have been associated with increased sugar-sweetened beverage consumption (Onufrak, Park, Sharkey, & Sherry, 2014; Ritter, 2018), a risk factor for obesity and diabetes (Malik, Popkin, Bray, Després, & Hu, 2010). A lack of available water may also limit the cooking that households can do (Wutich & Brewis, 2014; Collins et al., 2018), possibly contributing to more meals consumed outside the home, a risk factor for poor diet quality (Bezerra et al., 2015) and obesity (Kant et al., 2015).

While less attention has been paid to the health effects of water security, several recent studies document that insufficient and/or insecure water supply have significant impacts on both physical (Hunter et al., 2010) and psychological health (Stevenson et al., 2012; Wutich & Ragsdale, 2008). Further, little research has examined whether water security is associated with the dual burden of disease or how water security may interact with food security in the development of the dual burden.

Thus, we test whether water access and quality and food quality and security are individually and jointly associated with the prevalence of the dual burden and its components, UND/ID and OWT/NCD, among individuals and households in Galápagos, Ecuador. The Galápagos Islands serve as an important location for this research. Tourism and migration have ignited economic growth, environmental change and urban development on the islands, creating new pressures for human health. The >300% population growth from 2000 to 2010, annual population growth rate of 3.3%, and 225,000 annual tourists strain water and food resources (Villacis & Carrillo, 2010; Walsh et al., 2010; Walsh & Mena, 2016). Water and sanitation services have not been able to keep up with the demands placed on the system by expanding urban development and the tourism industry. Water quality testing on the provincial capital of San Cristobal has documented high levels of E. coli in household tap water (Gerhard, Choi, Houck, & Stewart, 2017) and common infectious morbidity from gastrointestinal, respiratory, urinary and skin infections (Walsh et al., 2010). Island residents are concerned about the quality of municipal water and often resort to buying bottled water for drinking and cooking (Houck, 2017). Food availability, particularly the availability of fresh foods, is also a critical issue (Page, Bentley, & Waldrop, 2013). The designation of much of the island as park land limits the amount of food that can be grown on the island leaving residents and visitors largely dependent on processed foods shipped from the mainland, over 1000 km away. This combination of exposure to environmental pathogens through unclean water and high-energy, high-fat diets contributes to a dual burden of disease on the islands, with infections persisting alongside rates of overweight and obesity among children and adults that are the highest in Ecuador (Freire et al., 2014).

In this paper, we take a syndemic approach (Bulled, Singer, & Dillingham, 2014; Himmelgreen, Romero‐Daza, Amador, & Pace, 2012; Mendenhall, 2017; Mendenhall, et al., 2017; Singer, 2009), arguing that the pressures accompanying rapid urbanization, population growth, and tourism in the Galápagos place individuals and households at risk for the co-occurrence of UND/ID and OWT/NCD through inadequate access to healthy diets and poor water infrastructure (Figure 1). Using data collected in the Galápagos Islands as part of Ecuador’s nationally-representative Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutricion (ENSANUT-ECU) last conducted in 2012, we describe the prevalence of the dual burden and its components (UND/ID and OWT/NCD) in individuals and households. Past work on the dual burden has focused on a limited number of variables, usually the co-occurrence of stunting and overweight/obesity in households or anemia and overweight/obesity in individuals, and household pairs, usually mothers and an index child under 5, to describe the dual burden. While this work has contributed greatly to our understanding of the patterning of and risk factors for the dual burden in LMIC, it may underestimate the true burden of infectious and cardiometabolic disease and fail to fully describe the factors placing households and individuals at risk.

Figure 1:

Conceptual model of the syndemic of poor water and food access and the dual burden of disease

We examine how water and food access and quality, two key environmental components shaped by economic change and structural disparities, shape the dual burden at the household and individual levels. We test: 1) whether water quality and access and diet quality and food security are separately associated with the dual burden and its components and whether these associations are similar at both the individual and household levels and 2) whether inadequate water and food security act synergistically to increase the risk of the dual burden for individuals and households. Structural differences in access to quality diets and clean water may contribute to differential patterns of health (e.g UND/ID only or OWT/NCD only vs. dual burden) across households. We propose that the dual burden will be more common in households with both food and water insecurity since exposures to both water and food constraints may limit families’ abilities to employ adequate coping strategies for one condition or the other. At the individual level, the existence of the dual burden and its components reflect differences in individuals’ access to, interaction with and/or susceptibility to water and food resources. We propose that individuals will be sensitive to water and food exposures separately and also their joint effects. While both have important consequences for health, the existence of the dual burden at these dual levels may stem from different causes and may require different approaches to address.

Methods

Setting:

Participants were residents of two of the four populated islands of the Galápagos archipelago, San Cristóbal, the island that serves as the provincial capital, or Santa Cruz, the island with the largest population and most tourist activity, and lived in either of two urban centers or three rural towns. As of the 2010 census, San Cristobal had 7475 residents and Santa Cruz had 15,393 (INEC-CREG 2010). On both islands, the vast majority of land (96.7%) is designated as national park land and over 80% of residents live concentrated in urban areas. In San Cristobal, the city of Puerto Baquerizo Moreno has 6672 inhabitants with an additional 658 inhabitants living the rural town of El Progresso and scattered farms. On Santa Cruz, the city of Puerto Ayora has 11,974 inhabitants and the rural towns of Belavista and Santa Rosa have 2425 and 994 residents, respectively (INEC-CREG 2010).

Compared to the mainland, the standard of livng on the islands is relatively high (Villacis & Carrillo, 2010). On both islands, over 99% of households have electricity and a similar proportion have acceess to cellular phones (INEEC-CCRG 2010). As of the 2010 census, the islands had a low unemployment rate (approximately 5%). San Crisotbal residents work in primarly in public administration (21%), tourism (21%), and agriculture or fishing (11%) while Santa Cruz residents work in tourism (31.7%), commerce (14.9%), or agriculture or fishing (7.8%). The average monthly income for public and private workers in Galapagos is almost 3 times higher than that on the mainland ($772.03/month vs $251.70/month; Villacis & Carrillo, 2010). However, the cost of living is also higher on the islands and residents face problems affording basic services. The “cost of basic basket,” a composite economic measure of 75 goods and services considered necessary to satisfy basic needs, is considerably more expensive on the islands ($869 on Galapagos vs $536 on the mainland in March 2010; Villacis & Carrillo, 2010). Consequently, 47.6% of households are considered unable to meet basic needs. However, this figure is lower than on the mainland (56.2%; Villacis & Carrillo, 2010) and no households are considered to live in extreme poverty (Granda Leon, Gonzalez Cambra, and Calvopina Carvajal 2013).

While over 80% of the population on both island have public water access, the water infrastructure varies significantly betweeen San Cristobal and Santa Cruz. San Cristóbal has a fresh water source and water treatment plant, which supplies water for the municipal network year-around. Roughly 93% of households receive municipal piped water that is collected and stored in household cisterns (Guyot-Tephany, Grenier, and Orellana 2013). However, due to concerns over the quality of municpal water, residents also purchase bottled water from two private companies on the island or treat their tap water before drinking (Houck 2017). On Santa Cruz, the municipality provides water that is mainly brackish, is not treated, and is considered non-potable according to national and international regulations (Reyes et al., 2015). As a result, bottled water is the main source of drinking water and costs for this water are high (Reyes et al., 2015). Sewage treatment also differs between the islands. In San Cristobal, approximately 75% of housheolds have indoor bathrooms connected to the municipal sewage system and another 23% have indoor bathrooms and septic tanks (INEC-CCREG 2010). Santa Cruz residenets primarly rely on indoor plumbing connected to septic tanks (95.4%).

Sample:

Data come from Ecuador’s nationally-representative Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición (ENSANUT-ECU) conducted in 2012 (Freire et al., 2013). ENSANUT -ECU identified participants using a multi-stage, stratified sampling design based on urban/rural residence, region, and province. Twelve households were identified from each census tract. Within selected households, one individual from each age group of interest (<5, 10–19, and 20–59 years) and one woman of reproductive age was selected to participate. This sampling strategy yielded 19, 949 participating households and over 87,000 individuals. Biomarkers were collected on a subsample of 21, 249 individuals over the age of 6 months. Data were collected in the participating households and included sociodemographic surveys, anthropometry, 24-hour dietary recalls, and household environmental measures.

The analytic sample of the current paper includes 1119 children, aged 0 - <19 years, and 1582 adults, aged 19–59, from 693 households residing on the Galápagos. Of this sample, a sub-sample of 731 individuals (392 children, 6 months to <19 years, and 339 adults) had measured biomarkers and 665 adults completed 24-hour diet recalls (S-Figure 1). This secondary analysis was approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board.

Water access and quality:

ENSANUT-ECU collected information on household water source (i.e. public system, well-water, river water, etc.), method of delivery (i.e. piped water within the home, piped water outside of the home, etc.), drinking water source (i.e. bottled water, tap water, boiled water, etc.) and sanitation service (S-Table 1). We created two metrics from these questions to assess water access and quality (Nicholas et al, under review). For water access, we created a water access index (WAI) using three survey questions (Where does your household primarily receive its water from? How is water delivered into the household? and What type of hygienic and waste services does the household receive?). Responses were rated on a scale of 0–4 for a total of 12 possible points, with higher points assigned to responses that correspond to increased access. One survey question, whether sanitation services where used only by the household or shared with other households, had little variability in the responses – >90% of households had their own waste disposal– and was excluded from the scale construction. Due to its highly non-normal distribution (two scores had over 80% of responses), WAI was dichotomized into a binary variable representing maximum water quality (a score of 12 in 28% of households) vs. all other scores (72% of households). For water quality, we condensed the survey question about drinking water sources (What is the primary source of water consumed by household members?) into a binary variable corresponding to households that purchase purified water (61%) versus any point-of-use treatment method (39%). This is based on literature highlighting inconsistent adherence and associated reduction in water quality from boiling, filtering, and adding chlorine (Arnold & Colford Jr, 2007; Brown & Sobsey, 2012).

Diet Quality:

A subsample of 665 respondents completed a single 24-hour dietary recall survey. While single 24-hour recalls are criticized for not capturing habitual diet, relying on the memory and cooperation of the participant, and needing well-trained interviewers, the ENSANUT-ECU study methods attempted to mitigate against these limitations (Freire et al., 2015). Interviewers received extensive training on dietary interview techniques, data collection, and data entry, and they were supervised in the field. To account for issues with participants’ inability to recall foods or estimate of portion sizes, reminders and prompts were used during interviews and listed foods were weighed and conversions for cooking preparation were created to generate a nationally-representative database of the weight/volume of food portions and homemade meals. To more accurately estimate usual consumption of nutrients from the single recall, nutrient intakes were adjusted using intra-individual variance estimators derived from the combination of three waves of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES; Jahns, Arab, Carriquiry and Popkin, 2005).

In the present study, diet quality was derived from these 24-hour recalls, using the Diet Quality Index-International (DQI-I), a tool developed for contexts undergoing nutritional transitions and designed to identify risk for both under- and over-nutrition (Kim, Haines, Siega-Riz, & Popkin, 2003). The DQI-I provides an absolute measure of diet quality with an overall score and scores for four components, variety, adequacy, moderation, and overall balance, and incorporates both nutrient intake and foods consumed. For the current analysis, we focus on the overall score and the variety and adequacy components, since these components of diet have been more consistently linked with nutrition and health outcomes (Darmon & Drewnowski, 2015; Marshall, Burrows, & Collins, 2014). The variety sub-component is based on the consumption of five major food groups (meat/poultry/fish/egg, dairy/beans, grains, fruits, and vegetables), chosen specifically for cross-national comparison, and variety of protein sources within the pro1tein group. The adequacy subscale assesses whether diets protect against undernutrition and is calculated based on the number of servings of fruits, vegetables and grains, the contribution of protein to total energy intake, and whether intakes of fiber, iron, calcium and vitamin C meet the recommended daily allowances. Higher scores on the DQI-I and the subscales represent diets with higher variety, adequate nutrient intake, and more balanced macronutrient and fatty acid intake.

After ensuring normality of the distribution of the DQI-I score, we used the std function in Stata to create a sample-specific DQI-I z-score with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 to provide a more easily interpretable effect size in our models. We also created a low diet quality score of <−1sd to reflect poor diet quality for our cjoint measures of water and food limitations. The adequacy subscale was standardized similar to the DQI-I score and low adequacy was defined as a sub-scale score <−1 z-score. Because the variety subscale was non-normally distributed with the modal response (75% of responses) being the highest possible score (20), we dichotomized the responses into high, a score of 20, vs. lower, any score <20. In sensitivity analysis, we tested these and alternate specifications of the variables (continuous and tertiles) to ensure that results were robust across variable definitions. Since not all individuals in the household completed the 24-hour recall, we assigned the same value (the maximum score if more than one individual per household completed the 24-hour recall) to all household members and are using this measure as a marker of household diet quality rather than a measure of individual intake.

Food Security:

ENSANUT-ECU incorporated two questions, adapted from the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations guidelines, to assess household food insecurity: during the last 2 weeks, did you have sufficient food to feed all the members of the household? and during the last two weeks, has the household had any difficulties paying for food? In the current analysis, the household was considered to have mild food insecurity if they responded “no” to the first question or “yes” to the second and to have moderate food insecurity if they responded “no” to the first question and “yes” to the second.

Anthropometry:

Height, weight, and waist circumference were measured by trained surveyors following standard protocols for children and non-pregnant adults (Freire, Ramirez-Luzuriaga, & Belmont, 2015). Weight was measured in duplicate using an electronic balance scale (Seca 874) to the nearest 50 g with participants wearing only light clothing. For children under age 2, length was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable length board (Seca 417). For children over age 2, standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable stadiometer (Seca 217). Length/height measurements were done in duplicate and the average measurement was used for analysis. Waist circumference was measured in duplicate to the nearest 0.1cm in individuals aged 10 and older using a fiberglass tape (Seca 201).

For the present analysis, stunting was defined as a sex-specific length/height-for-age z-score less than −2 for children and adults, compared to the WHO growth standards for children (de Onis et al., 2004) and the NHANES references for adults (Frisancho, 2008). BMI, calculated as kg/m2, was used to define overweight/obesity (BMI >25 kg/m2) and underweight (BMI<18 kg/m2) in adults. BMI z-scores were calculated using the WHO growth reference for children. In children and adolescents, underweight was defined as <−2 weight-for-age z-scores for children and overweight/obesity were defined as >1 BMIz. Waist-to-height ratio was calculated for both children and adults and values over 0.5 were considered as evidence of central obesity (Ashwell & Hsieh, 2005).

Biomarkers:

ENSANUT-ECU measured a number of biomarkers of cardiometabolic function and nutritional status including blood pressure, glucose, insulin, cholesterol, HDL-C, hemoglobin and C-reactive protein. Cardiometabolic measures were collected from individuals aged 10 or older. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings were collected in duplicate using a digital tensiometer with five minutes in between measures. In the present analysis, pre-hypertension was defined as a blood pressure >120/80 mm Hg and hypertension as >140/90 mm Hg for adults 18 and older (Whelton et al., 2018). For children and adolescents, we defined “elevated” blood pressure following the revised clinical practice guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics (Flynn, Kaelber, Baker-Smith, & Children., 2017). Children aged 10–13 were considered to have elevated blood pressure when they had systolic/diastolic measures above the >90th age-, sex- and height-specific percentiles and adolescents older than 13 were considered to have elevated blood pressure when they had values >120/80 mm Hg.

Blood samples were collected in participants’ homes by trained phlebotomists. Venous blood samples (13.5 cc) were collected from participants after an 8-hour fast. Samples were analyzed at a central, internationally-accredited laboratory, Netlab S.A., in Quito, Ecuador (International Organization for Standardization: 15189). Glucose, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol were analyzed using enzymatic colorimetric assays on the automated Roche/Hitachi Modular Evo P-800 system. Insulin was measured using chemiluminescent immunoassays on the Roche/Hitachi Modular Evo E-170. Hemoglobin was measured using the sodium lauryl sulphate (SLS) method on the SysmexXe-2100 fluorescence flow cytometry platform. C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured using automated nephelometry (Roche/Hitachi Modular EvoP-800 system). These methods do not require duplicate sample analysis. Internal and external quality control measures were used to ensure that %CV were within acceptable ranges, described in detail in Freire et al. 2015.

Morbidity:

Two measures were used to assess morbidity, self-reported symptoms and, for infectious morbidity, CRP levels. ENSANUT-ECU collected a history of illness symptoms over the past 30 days. Individuals were considered to have NCD morbidity if they reported cardiovascular or other chronic disease symptoms. Individuals were considered to have infectious morbidity if they or their caretaker for children under 10 reported respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms or had a C-reactive protein levels > 3mg/L for children (Thompson et al., 2014; Wander, Brindle & O’Connor, 2012) and >10mg/L for adults (Pearson et al., 2003).

Definition of the dual burden:

We used these measured anthropometry, cardiometabolic and nutritional biomarkers, and morbidity history to define OWT/NCD, UND/ID and the dual burden at the individual and household levels. Since biomarkers were collected in only a subset of individuals, we used the occurrence of one or more risk factors (Table 1) to categorize individuals into four groups: no risk factors, UND/ID only, OWT/NCD only, or dual burden. Individuals were considered to have UND/ID if they reported infectious symptoms, were stunted, were underweight, had iron deficiency anemia, or had acutely elevated CRP (levels > 3mg/L for children (Thompson et al., 2014; Wander et al., 2012), and >10mg/L for adults (Pearson et al., 2003)). Individuals were considered to have OWT/NCD if they had one or more of the following risk factors: reported NCD symptoms, moderately elevated CRP (1–3 mg/L in children (Skinner et al., 2010; Thompson et al., 2014) or 3–10 mg/L in adults (Pearson et al., 2003)), were overweight or obese, had high waist-to-height ratio, mean systolic or diastolic blood pressure indicative of prehypertension or hypertension, or, for adults only, impaired glucose, high Homa-IR, high total cholesterol, high LDL cholesterol, or low HDL cholesterol. Finally, individuals were considered to suffer from the dual burden if they had at least one UND/ID and one OWT/NCD symptom.

Table 1:

Definition and prevalence of UND/ID and OWT/NCDa risk factors for Galápagos children and adults

| Children (0–18 years)b | Adults (18–59 years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Prevalence %(n) | Definition | Prevalence %(n) | |

| Overweight/Cardiometabolic Disease Risk Factors (OWT/NCD)a | ||||

| NCD symptoms | Self-reportedb cardiovascular problems or chronic disease symptoms | 0.7 (7) | Self-reported cardiovascular problems or chronic disease symptoms | 4.9 (71) |

| Overweight/Obesity | BMIZ>1c | 38.7 (258) | BMI>25 | 74.4 (803) |

| High Waist-to-Height Ratio | >0.5 | 37.0 (129) | >0.5 | 86.7 (884) |

| Moderate Inflammation | CRP 1–3 mg/Lb,d | 8.7 (34) | CRP 3–10mg/Le | 22.0 (74) |

| Pre-/hypertension | Children 10–13: >90th percentile for age, sex and height; Children over 13: SBP >120 or DBP>80 | 19.6 (70) | SBP >120 or DBP>80 | 46.6 (504) |

| Impaired glucose | >126 | 26.7 (87) | ||

| Impaired HOMA-IR | >4.65 | 49.8 (100) | ||

| High Total Cholesterol | >200 | 32.2 (109) | ||

| High LDL-C | >130 | 30.7 (102) | ||

| Low HDL-C | <40 for men, <50 for women | 50.7 (172) | ||

| Undernutrition/Infectious Disease (UND/ID) | ||||

| ID symptoms | Maternal or self-reported respiratory or GI symptomsb | 33.0 (354) | Self-reported respiratory or GI symptoms | 18.4 (299) |

| Acute inflammation | CRP>3 mg/Ld | 12.5 (49) | CRP >10 mg/Le | 3.5 (12) |

| Iron deficiency anemia | Hemoglobin <11 for 6mo-5 yo; <11.5 for 5–11 yo; and <12 for 12–14 yo and women; <13 boys 14–18 | 13.2 (48) | Hemoglobin <12 for women and <13 for men | 9.7 (33) |

| Underweight | WAZ <−2c | 1.7 (7) | BMI<18 | 0.6 (6) |

| Stunted | HAZ <−2c | 8.9 (59) | HAZ<−2f | 22.3 (241) |

Abbreviations: |OWT/NCD: overweight/noncommunicable disease, BMIZ: Body Mass Index Z-Score, BMI: Body Mass Index, CRP: C-reactive protein, SBP: systolic blood pressure, DP: diastolic blood pressure, HOMA-IR: homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, LDL-C: low density lipoprotein-cholesterol, HDL-C: high density lipoprotein-cholesterol, UND/ID: undernutrition/infectious disease, ID: infectious disease, GI: gastrointestinal infection, WAZ:weight-for-age z-score, HAZ: height-for age z-score. All cut points were derived from current clinical guideline unless otherwise cited.

Blood samples were collected from children 6 months old and older. Blood pressure and chronic disease symptoms were collected in children 10 years old and older. Mothers reported infectious symptoms for children under age10.

BMIZ, HAZ, and WAZ were defined using the WHO MultiCentre Growth Reference Standards (de Onis et al., 2004) and z-scores for overweight, underweight and stunting are those recommended by the WHO.

CRP cut points for moderate and acute inflammation in children come from: Skinner et al., 2010; Thompson et al., 2014; and Wander et al., 2012.

CRP cut points for moderate and acute inflammation in adults come from: Pearson et al., 2010.

HAZ and stunting in adults was defined using Frisancho, 2008.

We categorized households into the same categories: neither burden if no members had any UND/ID or OWT/NCD risk factors, UND/ID if members only had UND/ID risk factors, OWT/NCD if members only had OWT/NCD factors, and dual burden if either a member had both types of risk factors or there was at least one member with each type of risk factor. Because the majority of households fell in to the dual burden category (89.8%) and there were only a few households with no risk factors (0.3%) or UND/ID only (0.3%), we dichotomized our household measure into dual burden or not.

Statistical Analysis:

Descriptive statistics were used to examine age and sex patterns in the dual burden and its components, using a Pearson chi-square test of trend. We examined differences in demographic and environmental variables for the four groups of individuals, “healthy,” UND/ID only, OWT/NCD only, and dual burden using oneway ANOVA for continuous outcomes and chi-square tests for categorical outcomes. For those variables showing significant differences, we examined pairwise differences in values compared to the “healthy” referent group.

We used multinomial logistic regression models to test whether water and food exposures placed individuals at greater or lesser risk of being in one of the three risk groups compared to the healthy referent group. We first ran separate models for each of the two water (access and quality) and four diet (overall diet quality, low adequacy, low variety, and HFI) exposures, adjusting for the sociodemographic variables that were significant in the bivariate analysis. These included: age, sex, economic quintile (a composite measure of household assets and characteristics), ethnicity (mestizo, indigenous Ecuadorian vs. other race/ethnicity), marital status of the head of household (married/in a union, separated/divorced, widowed, or single), place of birth (in Galapágos, in mainland Ecuador, or in another country) and island (Santa Cruz vs. San Cristobal). Standard errors were adjusted to account for clustering by household. We then ran a similarly specified multinomial model with a four-level joint exposure variable (no water or food issues, food issues only, water issues only, and both water and food issues) to test the independent and combined effects of water and food concerns on the dual burden and its components.

To test the effects of water and food exposures on the dual burden at the household level, we repeated these analysis with our household-level variables. We used logistic regression models to test the odds of a household having the dual burden with, first, the separate water and food exposures and then the four-level joint exposure variable. These models were adjusted for head of household sex, ethnicity, marital status and place of birth, economic quintile and island. We tested for differences between these four levels of water and food exposure using likelihood ratio tests. We calculated and plotted predicted probabilities from this model using the Stata margins command. All analyses were conducted using STATA version 15 (College Park, Texas). Statistical significance was considered to be p < 0.05.

Sensitivity analysis:

Since we were interested in both the dual burden of infectious and cardiometabolic disease and under- and over-nutrition, our analysis of the dual burden incorporates a larger number of risk factors for UND/ID and OWT/NCD than normally used in the literature on the dual burden (Varela-Silva et al., 2012). We created a second dual burden variable for individuals and households using only overweight and stunting to more closely match the existing literature and reran our models with this outcome to assess whether the results would change substantially with this narrower definition.

Results

On the individual level, OWT/NCD was the most common condition (38.9%) with dual burden (both UND/ID and OWT/NCD) the next most common (26.5%; Figure 2). The prevalence of the dual burden and its components differed by age and sex (S-Figure 2). UND/ID was more common in children under the age of 5 and declined significantly with age. Conversely, both OWT/NCD and the dual burden increased significantly with age. Sex differences were present in adults only, with women having a significantly higher prevalence of OWT/NCD and dual burden than men. Among the UND/ID risk factors, ID morbidity (respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms in past month) was the most common risk factor for children and iron deficiency anemia and stunting were also problems for children and adults (Table 1). Among the OWT/NCD risk factors, overweight/obesity and central obesity (high waist-to-height ratio) were the most common risk factors for children and adults, but pre- and hypertension and impaired HOMA-IR were also common among adults.

Figure 2:

Prevalence of Overweight/Noncommunicable Disease (OWT/NCD), Underweight/Infectious Disease (UND/ID), and the Dual Burden by Age and Sex.

*Significant (p<0.05) age trend for neither, UND/ID, OWT/NCD and Dual burden; † significant (p<0.05) sex differences between adult men and women in OWT/CD and dual burden.

Nearly all sociodemographic characteristics differed between individuals with no dual burden components, those with UND/ID only, those with OWT/NCD only and those with both (Table 2). Compared to individuals with none of the dual burden components, those with a dual burden had lower incomes, were more likely to be indigenous Ecuadorian, were less likely to be single, and were more likely to be born in another part of Ecuador. Similarly, those with OWT/NCD were more likely to be single and to be born in another part of Ecuador. Water quality and access and food security did not significantly vary across groups in bivariate analysis. The prevalence of low variety and low adequacy was differed across groups and variety scores were lower in individuals with the dual burden than in the “neither” reference group.

Table 2:

Sample Characteristics by Dual Burden Components

| Neither n=374 |

UND/ID onlya n=363 |

OWT/NCD only n=829 |

Dual Burden n=567 |

p valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 20.0 (18.3) | 15.4 (18.5) | 31.4 (16.0) | 31.5 (15.1)* | <0.001 |

| Sex, %male | 46.3 (173) | 55.4 (201)* | 47.7 (395) | 44.1 (250) | 0.008 |

| Income quintile | |||||

| <20th%ile | 7.0 (26) | 8.8 (32) | 6.4 (53) | 13.1 (74)* | 0.001 |

| 20–40th %ile | 10.7 (40) | 13.2 (48) | 11.6 (96) | 14.1 (80) | |

| 40–60th %ile | 21.9 (82) | 23.4 (85) | 18.6 (154) | 19.8 (112)* | |

| 60–80th %ile | 31.0 (116) | 29.5 (107) | 32.6 (270) | 29.6 (168)* | |

| >80th %ile | 29.4 (110) | 25.1 (91) | 30.9 (256) | 23.5 (133)* | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Mestizo | 88.2 (330) | 88.7 (322) | 87.5 (725) | 85.6 (485) | 0.002 |

| Indigenous | 4.6 (17) | 7.4 (27) | 5.2 (43) | 9.7 (55)* | |

| Other | 7.2 (27) | 3.9 (14) | 7.4 (61) | 4.8 (27) | |

| Marital status (adults only) | |||||

| Married/couple | 45.9 (95) | 51.5 (70) | 64.1 (468) | 65.5 (324) | <0.001 |

| Separated/divorced | 6.3 (13) | 3.7 (5) | 9.6 (70) | 10.7 (53) | |

| Widowed | 0.5 (1) | 2.2 (3) | 1.4 (10) | 1.0 (5) | |

| Single | 47.3 (98) | 42.7 (58) | 24.9 (182)* | 22.8 (113)* | |

| Place of birth | |||||

| Galapagos Islands | 48.7 (182) | 54.3 (197) | 33.8 (280) | 25.4 (144) | <0.001 |

| Mainland Ecuador | 50.5 (189) | 44.6 (162) | 65.7 (545)* | 32.1 (423)* | |

| Another country | 0.8 (3) | 1.1 (4) | 0.5 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Water access, % highest | 27.0 (101) | 27.8 (101) | 29.4 (244) | 25.0 (142) | 0.34 |

| Water quality, %buying purified | 60.2 (225) | 60.3 (219) | 64.5 (535) | 62.4 (354) | 0.38 |

| Food Security | |||||

| Mild | 18.2 (68) | 19.0 (69) | 18.2 (151) | 20.8 (118) | 0.32 |

| Moderate | 7.0 (26) | 10.7 (39) | 7.7 (64) | 9.4 (53) | |

| Diet quality index subsample, n | 170 | 211 | 423 | 308 | |

| Overall score (max 94) | 65.8 (6.7) | 66.6 (6.3) | 65.7 (6.9) | 66.0 (5.9) | 0.21 |

| Diet quality z-scorec | 0.42 (0.9) | 0.53 (0.9) | 0.42 (1.0) | 0.53 (0.8) | 0.21 |

| Variety score (max 20) | 19.2 (1.9) | 19.3 (1.6) | 19.2 (1.8) | 19.6 (1.3)* | 0.01 |

| Variety, low vs. higherd | 18.8 (32) | 16.6 (35) | 19.2 (81) | 11.0 (34)* | 0.02 |

| Adequacy score (max 40) | 30.6 (3.6) | 30.6 (3.3) | 30.1 (3.9) | 30.6 (3.4) | 0.16 |

| Adequacy, low vs. highere | 5.9 (10) | 2.8 (6) | 8.3 (35) | 20.8 (118) | 0.004 |

Abbreviations: UND/ID undernutrition and infectious disease; OWT/NCD: overweight and noncommunicable disease.

from oneway ANOVA for continuous variables and Pearson chi2 test of trend for categorical variables;

indicates significant difference from “Neither” group in contrast tests.

Sample specific z-score

Dichomtomized as having the a score <20 or the maximum score of 20.

Dichomotomized as <−1 sample-sprecifc z-score or higher

Association between water and food risk factors and the dual burden components

To examine the associations between water and food exposures and components of the dual burden, we used multinomial regression models to compare the relative risk of UND/ID only, OWT/NCD only and the dual burden compared to the “healthy” individuals by water and food exposures separately (Table 3). Neither water measure differed between groups. Higher diet quality index scores were associated with a higher relative risk of an individual having dual burden compared to the referent group. Conversely, low diet variety was associated with a lower relative risk of an individual having dual burden compared to the referent group. At the household level, higher diet quality index scores and mild food insecurity were associated with a greater odds of being a dual burden household.

Table 3:

Water and food factors risk factors for UND/ID, OWT/NCD and the dual burden at the individual levelaand dual burden at the household levelb

| Individual | Household | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UND/ID onlyc | OWT/NCD only | Dual Burden | Dual Burden | |

| RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Individual Models | n=2133 | n=693 | ||

| Water access, highest vs. lower | 0.72 (0.43, 1.19) | 0.73 (0.44, 1.11) | 0.76 (0.48, 1.19) | 0.63 (0.31, 1.27) |

| Water quality, %buying purified | 0.99 (0.70, 1.39) | 1.21 (0.91, 1.60) | 1.10 (0.81, 1.50) | 0.82 (0.53, 1.26) |

| Overall diet quality, stdd | 1.14 (0.93, 1.41) | 1.02 (0.86, 1.22) | 1.22 (1.02, 1.46)* | 2.37 (1.69, 3.32)*** |

| Low variety | 0.81 (0.45, 1.44) | 0.81 (0.49, 1.35) | 0.43 (0.24, 0.77)** | 0.71 (0.31, 1.64) |

| Low adequacy | 0.49 (0.18, 1.39) | 1.15 (0.49, 2.74) | 0.43 (0.15, 1.22) | 0.43 (0.15, 1.28) |

| Food Insecurity | ||||

| Mild | 1.09 (0.72, 2.97) | 1.10 (0.76, 1.58) | 1.20 (0.82, 1.73) | 2.09 (1.06, 4.14)* |

| Moderate | 1.58 (0.84, 2.97) | 1.24 (0.76, 2.03) | 1.44 (0.85, 2.42) | 1.17 (0.51, 2.65) |

| Joint models | ||||

| No water or food issues | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Food issues onlye | 1.27 (0.50, 3.23) | 2.01 (1.06, 3.83)* | 1.33 (0.66, 2.66) | 1.43 (0.44, 4.72) |

| Water issues onlyf | 1.46 (0.85, 2.49) | 1.40 (0.89, 2.21) | 1.24 (0.75, 2.07) | 1.43 (0.70, 2.92) |

| Both water and foodg | 1.91 (1.05, 3.46)* | 1.43 (0.85, 2.42) | 1.45 (0.84, 2.50) | 2.31 (1.01, 5.30)* |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001;

Relative risk ratios come from individual multinomial models comparing UND/ID, OWT/NCD and DB to a normal weight/healthy referent for individuals. All models are adjusted for age, sex, economic quintile, ethnicity, marital status of the head of household, place of birth, island, and clustering by household.

Odds ratios come from individual logistic regression models comparing dual burden to households without the dual burden. Models are adjusted for head of household sex, ethnicity, marital status and place of birth, economic quintile and island.

Abbreviations: UND/ID: undernutrition and infectious disease; OWT/NCD: overweight and noncommunicable disease.

Models with diet quality include 1362 individuals and 317 households.

Includes low diet quality and/or food insecurity;

Includes poor water access and/or use of nonbottled drinking water;

includes low diet quality and/or food insecurity and poor water access and/or use of nonbottled drinking water.

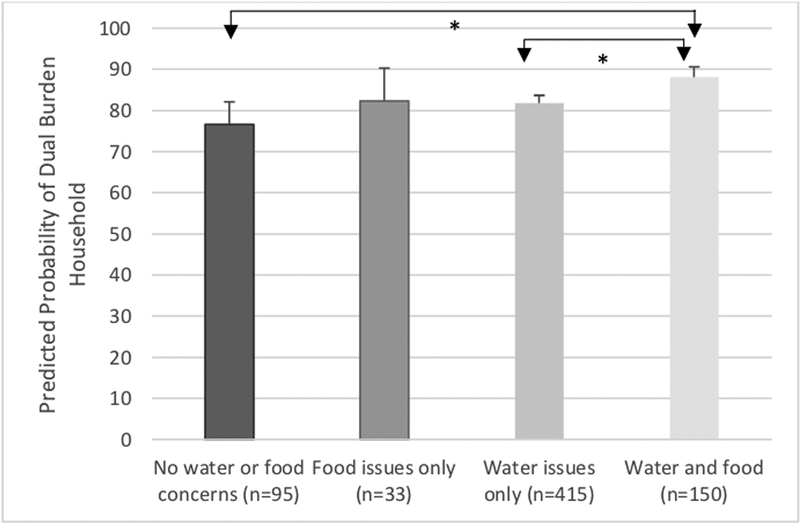

When looked at jointly, individuals living in households with both water and food limitations were more likely to have UND/ID than were healthy individuals with no water or food issues (Table 3). Individuals living in households with food issues only were have a greater risk of having OWT/NCD than healthy individuals with no water or food issues. At the household level, households with both water and food issues were significantly more likely to be dual burden households. The probability of being a dual burden household was high for all households, but the probability was significantly higher for households with food and water issues (88.1%) compared to households with neither problem (76.6%) and those with just water problems (81.8%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Independent and Joint Associations of Water and Food Limitations with the Dual Burden at the Household Level.

*Significant (p<0.05) group differences in predicted probability of household experiencing the dual burden from logistic regression from model controlling for head of household marital status, sex, and place of birth, economic quintile and island.

Sensitivity Analysis:

Overall, the results from the sensitivity analysis using the narrower definition of the dual burden (i.e overweight and stunting) were similar to our main analyses (S-Table 2), particularly in the household models and the joint exposure models. Some differences were seen in the individual models, however. In contrast to the main model results, low diet adequacy was associated with a lower relative risk of having UND/ID compared to the “healthy” referent group. In these models, neither diet quality nor adequacy predicted an individual’s risk of dual burden, though, as with the household models, mild food insecurity was associated with a greater risk of having dual burden compared to the referent group. Finally, in the household models of dual burden, better water access and quality were associated with lower odds of dual burden, though the association with water quality did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06). Overall diet quality and mild food insecurity remained significantly positively associated with the odds of dual burden and the household level.

Discussion

Our analyses show that the prevalence of the dual burden is high for both individuals and households in Galápagos. Overweight, obesity, and cardiometabolic risk factors are common among children over age 5, adolescents and adults while infectious disease morbidity and undernutrition remain prevalent among both younger children and adults. Consequently, the vast majority of households, nearly 90%, experience a dual burden of UND/ID and OWT/NCD, placing them at risk for increased morbidity and, for children, potential long-term health consequences.

For individuals and households, experiencing the dual burden was associated with household diet quality and food security. Higher diet quality was associated with a greater risk and lower variety diets with a reduced risk of dual burden in individuals. At the household level, both higher diet quality and mild food insecurity were associated with a greater risk of household members experiencing the dual burden. While neither water access nor water quality were associated with the dual burden or its components separately, individuals and households suffering from both water and food limitations were more likely to suffer from UND/ID and the dual burden, respectively. These results suggest that water and food exposures act as a syndemic in this context, placing individuals and households at risk for the dual burden of UND/ID and OWT/NCD.

The prevalence of undernutrition and overweight/obesity were both high in our sample. While few individuals of any age were underweight, 9% of children and 23.3% of adults were stunted. At the same time, over 1/3 of children and nearly 3/4 of adults were overweight or obese. These prevalences differ from Ecuadorian national estimates, with considerably lower stunting than the national average of 25.3% in children and higher overweight/obesity than the national averages of 25% overweight/obesity in children and 65% in adults (Freire et al., 2014; Freire, Waters, Román, et al., 2018). While the stunting prevalence for children in the Galápagos is more similar to other LAC, where, for example, stunting ranges from 7.1% in Brazil to 14.0% in El Salvador (Corvalán et al., 2017), the prevalence of overweight and obesity are high compared to both the Ecuadorian national average and to other countries in the region (Freire, Waters, Román, et al., 2018; Jones et al., 2016). Consequently, the dual burden at the individual and household levels is also common in the Galápagos. 16% of children and 33.9% of adults had simultaneous UND/ID and OWT/NCD and nearly 90% of households suffered from both UND/ID and OWT/NCD. While these estimates are considerably higher than the 10% co-occurrence of overweight/obesity and anemia seen in Mexican women (Jones et al., 2016) or the 5% co-occurrence of overweight and stunting seen in non-indigenous Mexican children (Fernald & Neufeld, 2007), these findings stem from our broader definition of UND/ID and OWT/NCD. Limiting the definition of dual burden to only overweight and stunting results in an individual prevalence of 3.2% in children, 17.6% in adults, and 50.9% of households in our sample, within the range of other LMIC (Doak et al, 2005). Thus, our data show that, while common, the dual burden of stunting and co-occurring overweight/obesity is not more prevalent in the Galapagos than in many other LMICs.

Similarly to other studies in LAC (Jones et al., 2018; Parra et al., 2018; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2014), we found that mild food insecurity was associated with a greater risk of the dual burden at the household level. Previous research in LAC and elsewhere has linked HFI to both the dual burden and its components of under- and over-nutrition. Mild food insecurity, for example, has been associated with both overweight/obesity and the dual burden in Colombian households (Parra et al., 2018). HFI may also contribute to the dual burden by increasing undernutrition and infectious morbidity in children and adults. HFI, for example, was associated with a greater risk of illness, anemia and low height for age z-score in Nicaraguan children (Schmeer & Piperata, 2017) and undernutrition in urban Ecuadorian women (Weigel, Armijos, Racines, Cevallos, et al., 2016). While less research has looked at the association between HFI and other markers of the dual burden beyond overweight and stunting, mild HFI has been associated with type 2 diabetes and hypertension in Mexican women (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2014), though not in Ecuadorian women living in Quito (Weigel, Armijos, Racines, & Cevallos, 2016). Similarly, mild food insecurity was associated with both overweight and anemia in Mexican women (Jones et al., 2016).

Studies linking HFI to the dual burden propose that HFI alters diet quality, leading to lower diet quality, less variety within and across food groups, and, possibly, higher consumption of energy-dense, nutrient poor foods (Bassett, Romaguera, & Giménez, 2014; Varela-Silva et al., 2012; Weigel & Armijos, 2015). Contrary to these studies, however, we found that higher relative household diet quality is associated with an elevated risk of the dual burden while lower variety (an absolute measure of number of food groups consumed and the number of protein sources consumed) is associated with a lower risk of dual burden. These differences may be linked to the unique context of the Galapagos as an eco-tourism location. Work in other tourism-centered economies, such as Costa Rica and Mexico, have found that the dual burden in individuals and households is associated with mild food insecurity stemming from seasonal fluctuations in intake based on the highly-seasonal economies of the regions and the changing foods available to cater to visiting tourists (Himmelgreen et al., 2012; Leatherman, Hoke, & Goodman, 2016; Ruiz, Himmelgreen, Romero Daza, & Peña, 2014). Such fluctuations in food availability may alter eating patterns, contributing to overconsumption when foods are available and/or more affordable. A recent analysis of household food expenditures on the Galápagos found that availability and price are two of the most important factors shaping household purchases (Freire, Waters, Román, et al., 2018). Residents are increasing their expenditures on processed and ultra-processed foods, which are viewed as more readily available, better quality, and less expensive than fresh produce (Freire, Waters, Román, et al., 2018). Thus, the fact that higher diet quality is associated with a greater risk of DB and low variety with a reduced risk may reflect differences in access to and ability to afford these more expensive, fresh foods.

Further our measure of diet quality extrapolates from the measured individual to the household and intakes may differ across individuals within the household. Previous qualitative research in the Galápagos found that diet diversity was high for children, though not mothers, in even households with low food security (Pera, Katz, & Bentley, 2019), suggesting that mothers may compromise their own diets to provide better quality foods for their children. Such differences in food allocation could serve to generate the dual burden at the household level, despite overall high levels of diet quality among some members.

Contrary to a large literature linking water quality to UND/ID (Günther & Fink, 2010; Vilcins et al., 2018) and more limited literature linking water quality to OWT/NCD (Liu, Balasubramaniam, & Hunt, 2016; Ritter, 2018; Ritter, 2019), we found no individual effects of either water access or quality in our main analysis. Access to drinking water has been linked to reduced morbidity from infectious illnesses (Bivins et al., 2017; Gamper-Rabindran, Khan, & Timmins, 2010) and, less consistently, with a reduced risk of child stunting (Vilcins et al., 2018). Our previous work in the Galápagos similarly found no significant associations between water quality or access and stunting or diarrheal morbidity among children, suggesting that these measures are either too crude to capture pathogen exposures or that other factors are buffering children from stunting in this context (Nicholas et al., under review).

Access to clean water has also been shown to be associated with overweight through direct and indirect pathways. Piped water availability was associated with a significant, albeit, small increase in overweight/obesity among Indian school children (Liu et al., 2016), likely due to a reduction in diarrhea incidence. Conversely, a much larger indirect effect of the lack of access to clean water on obesity prevalence has also been documented (Ritter, 2019). Access to piped water in the home increased the consumption of water and home prepared foods, factors associated with a healthier BMI (Ritter, 2018). Water access and perceived quality are also associated with the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB). Among adults in the United States, those who perceived their tap water to be unclean were more likely to consume SSBs (Onufrak et al., 2014), a risk factor for obesity (Malik et al., 2010). In Chile, a reduction in soda prices were associated with a dramatic increase in consumption and higher obesity rates in households lacking piped water (Ritter, 2018). Access to drinking water, then, would appear to be protective against both components of the dual burden, UND/ID and OWT/NCD. In the only study we were able to find that looked at water access and the dual burden, access to piped water was associated with a reduced risk of the dual burden of overweight in Bangladeshi mothers and anemia in their children. These results mirror what we find in our sensitivity analysis, where better water access was associated with lower odds of overweight and stunting at the household level.

While we found few independent effects of water quality or access on the dual burden or its components, these water measures were nevertheless important when we examined their joint effects with food insecurity and low diet quality. First, among individuals, those living in households with water and food concerns were more likely to suffer from UND/ID. The importance of both water and food insecurity on undernutrition have recently been documented among children in Burkina Faso, where the effects of water quality on child stunting interacted with community level food resources and maternal education to shape child growth outcomes (Grace, Frederick, Brown, Boukerrou, & Lloyd, 2017). For adults, concerns about food and water may also shape disease risk. Recent research in Nepal documents that both low water access and HFI are associated with elevated blood pressure in women across all wealth levels, suggesting that concerns with water and food lead to considerable stress and may contribute to the development of chronic disease (Brewis, Chaodhary, & Wutich, 2019). Similar effects of stress may underlie our household results as well. At the household level, we found that, compared to households with no dual burden components, those with water and food limitations were more likely to suffer from the dual burden. Water and food limitations were also associated with a higher risk of dual burden than water concerns alone, suggesting that water and food limitations may act synergistically to contribute to poor health.

At the household level, uncertain access to food and water may cause households to change their behaviors in ways that increase the risk of the dual burden. For example, food and water insecure households have been shown to cut back on intake, make substitutions, and ingest proscribed or stigmatized substances (Wutich & Brewis, 2014). In the Galápagos, households with food and water limitations may reduce their intake of more expensive (i.e. fresh) foods, drink SSB or juice as substitutions for water, and, potentially, still use contaminated water for household and hygiene purposes, leading to both obesogenic and pathogenic exposures.

For individuals, biological and behavioral pathways may link both actual poor water and diet quality and also concerns about water and food to these health outcomes. Household food insecurity, for example, is associated with diabetes and hypertension (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2014), through both changes in diet, such as consumption of less healthy food choices and altered eating patterns, such as emotional eating and overconsumption, and physical manifestations, such as obesity, depression and stress. These pathways interact, with poor diet quality contributing to obesity and diabetes and hypertension independently of obesity, stress contributing to adipose tissue deposition and obesity, and depression contributing to poorer eating practices, all exacerbating OWT/NCD risk. Further, if the foods individuals are consuming are energy-dense but nutrient poor, they may also contribute to undernutrition manifested as stunting in children or micronutrient deficiencies in children and adults (Varela-Silva et al., 2012). A further risk factor for adults is the rapidity of economic and dietary change in LMIC contexts like Galápagos. The adults in our sample have a much higher prevalence of stunting than children, 22% compared to 9%, suggesting that the adults were more likely to have faced undernutrition as infants and young children potentially increasing their risk of overweight and cardiometabolic disease in adulthood. Research from other LAC countries has found that stunting is associated with higher risk of metabolic syndrome (Boulé et al., 2003) and higher glucose, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol in young adulthood (González-Barranco & Ríos-Torres, 2004; Velásquez-Meléndez et al., 1999) compared to those of normal height. Further, some evidence suggests that a history of chronic malnutrition may alter energy metabolism (Frisancho, 2003), leading to greater adipose deposition. While the occurrence of the dual burden, at least as classically measured as the co-occurrence of stunting and overweight, is less easy to explain in children (Varela-Silva et al., 2012), the majority of children suffering from the dual burden in our sample have infectious morbidity along with overweight/obesity. These results are supported by studies of environmental enteropathy, which suggest that continued exposure to pathogens through unclean water sources and other environmental exposures alongside high fat consumption may contribute to both stunting and obesity through subclinical inflammation (Ding & Lund, 2011; Jones et al., 2014; Kau et al., 2011).

Finally, several sociodemographic variables were associated with the patterning of the dual burden. Compared to individuals with no dual burden risk factors, those with the dual burden were less likely to be of middle or higher income, were more likely to have be born in continental Ecuador, were more likely to be indigenous Ecuadorian, and were less likely to be single. These results are consistent with previous literature, which has documented a higher prevalence of dual burden in lower income and indigenous families in Mexico (Barquera et al., 2007; Fernald & Neufeld, 2007) and Colombia (Parra et al., 2018). Similarly, the components of the dual burden also tend to be inversely associated with income in LAC. Obesity, hypertension, and diabetes have all been found to be higher with lower income (Fleischer, Roux, Alazraqui, & Spinelli, 2008) and lower income is a well-established risk factor for stunting and undernutrition (Vilcins et al., 2018). Interestingly, place of birth, our measure of migration status, was also associated with the dual burden. Work in urban Quito found that those who had lived in the study neighborhood for more than half of their lives were less likely to suffer from HFI, suggesting that social networks may serve as an important buffer (Weigel, Armijos, Racines, Cevallos, et al., 2016). Similarly, qualitative work in the Galápagos found that recent migrants to the islands were more likely to be food insecure and proposed that recent migrants may be less able to afford or less exposed to the Western foods available on the island (Pera et al., 2019). Our findings on the patterning of the dual burden with income, indigeneity, and migration history further highlight the need to examine the strategies that households and individuals use to cope with limitations in food and water.

Our study is one of the few to examine the individual and joint impacts of water and food on the dual burden of disease. Importantly, our data come from a large, high quality survey with measured anthropometry and biomarkers of nutritional adequacy and cardiometabolic risk. The availability of data from multiple individuals within households allowed us to examine the dual burden at the individual and household levels. Our approach differs from past research in that we examined the association of water and dietary conditions on both the nutritional and epidemiological dual burdens of under- and over-nutrition and infectious and cardiometabolic disease at the individual and household levels. Our broader focus limits our ability to fully compare our results to the previous literature, which has focused on a narrower definition of the dual burden, and which, when examining the dual burden at the household level, has generally focused on mothers and an index child under the age of 5. While our broader definition increases the number of individuals and households labelled as dual burden compared to past research, our approach may more accurately represent the true health burden for individuals and households in LMIC facing constraints in water and food.

Despite these considerable strengths, our use of secondary data introduced several important limitations. First, our measures of water access and quality are based on a limited number of survey questions and then dichotomized due to the non-normality of their distributions. Such measures have been criticized for masking potential variability within “improved” and “non-improved” sources of water and for not addressing potential sources of contamination introduced during water usage (Vilcins et al., 2018). We chose to dichotomize our water quality variable into purchased water vs. all other treatment sources (i.e. boiling, using filters, adding chlorine etc) based on literature showing inconsistent adherence to water treatment recommendations (Arnold & Colford Jr, 2007; Brown & Sobsey, 2012). However, the heterogenous referent group may have limited our ability to find consistent individual effects of water quality on health. Similarly, we used an individual’s 24-hour recall to describe diet quality for all household members. Along with the limitations of 24-hour recalls for describing habitual diets (Gibson, 2005), our use of a single recall to describe household diet quality does not account for the existing variability between household members, something that has been previous documented in the Galápagos (Pera et al., 2019). While measures of household expenditures have shown that intakes tend to be highly correlated among family members (Coates, Rogers, Blau, Lauer, & Roba, 2017), these methods do not capture the direct pathways between individual intake and disease risk. Similarly, we are limited to a single, cross-sectional measure of cardiometabolic and nutritional biomarkers, which limits our ability to distinguish between acute and chronic illness states. This is particularly the case for CRP, which we used as a risk factor for both UND/ID and OWT/NCD. The measurement of CRP at a single time point cannot definitively distinguish between chronic elevations in baseline inflammation due to OWT/NCD or recovery from a recent illness. Serial measures are necessary to distinguish between these possibilities. However, only 24 individuals in of our sample (approximately 1% of the total sample) had elevated CRP as their sole UND/ID or OWT/NCD risk factor and excluding these individuals from analysis has no effects on our results. Our food insecurity variable was derived from two questions about insufficiency and inability to pay for food. While these items capture important dimensions of food insecurity, they may not fully capture other important domains, such as hunger and/or coping strategies. Finally, data were collected in 2012 and may not fully represent the current situation in the Galápagos; given the continued expansion of the population and tourism, our results may underestimate the current situation. We have recently collected similar data and will be able to describe these changes more fully.

Nevertheless, our findings with these measures suggest that further research with more fine-grained, up-to-date measures of the water and food environments, particularly experiential measures of water and food insecurity, on the dual burden of disease is warranted. Our findings that the dual burden is highly prevalent in both individuals and households highlights the need to more fully describe the patterning of the dual burden by age and sex and examine the underlying pathways contributing to malnutrition and disease risk. Contrary to our expectations, we did not find clear evidence that individuals were more likely than households to suffer health effects from the individual exposures to poor water and food security. Both individuals and households with better diet quality were more likely to suffer from the dual burden while water quality and access had no individual effects. We did find support for our hypotheses that households would show health effects when exposed to both poor water and diet conditions, since those facing water and food constraints were more likely to experience the dual burden than those with no issues or only water issues. This lack of clear distinctions between individuals and households may indicate that the factors for ill health are similar across household members or, perhaps more likely, that more fine-grained measures that address individual exposure to pathogens, high fat diets, and/or water-related stress are needed.

Future research should focus on differences in exposure to dietary and water risk factors and the factors contributing to differential susceptibility to these changing dietary and water environments within and across households. In particular, a syndemic approach that looks at the multiple social and physical risk factors contributing to water and food insecurity and how these factors shape individuals’ physical and mental health and household function is critical for understanding the development of the dual burden of disease. With more fine-grained measures of these physical and social contexts of water and food insecurity and the heterogeneity in individual and household responses to these limitations, future research will be able to more fully describe the pathways linking these key environmental exposures to health and well-being.

Conclusions

Our results show that the dual burden of UND/ID and OWT/NCD is a considerable health concern for Galápagos children and adults and households. While water exposures had few independent associations with OWT/NCD or UND/ID, diet quality and food security were associated with the dual burden and its components. When considered jointly, households with food and water limitations were more likely to suffer from the dual burden than households with only water concerns or no water or food issues, suggesting that limited access to clean water and high-quality diets may serve as a syndemic, contributing to a significant dual burden of disease. Understanding the biological and behavioral pathways linking these exposures to the dual burden of disease at the individual and household levels and, perhaps even more importantly, understanding the strategies households employ to manage these limitations is critical for identifying avenues of intervention in the Galápagos and LMIC more broadly.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This research is funded by NIH/FIC (1R21TW010832; PI: Thompson). This research received support from the Population Research Training grant (T32 HD007168) and the Population Research Infrastructure Program (P2C HD050924) awarded to the Carolina Population Center at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adair LS, & Cole TJ (2003). Rapid child growth raises blood pressure in adolescent boys who were thin at birth. Hypertension, 41(3), 451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adair LS, Martorell R, Stein AD, Hallal PC, Sachdev HS, Prabhakaran D, Wills AK, Norris SA, Dahly DL, Lee NR, Victora CG. (2009). Size at birth, weight gain in infancy and childhood, and adult blood pressure in 5 low-and middle-income-country cohorts: when does weight gain matter? The American journal of clinical nutrition, 89(5), 1383–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LC, Tegegn A, Tessema F, Galea S, & Hadley C (2012). Food insecurity, childhood illness and maternal emotional distress in Ethiopia. Public health nutrition, 15(04), 648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold BF, & Colford JM Jr (2007). Treating water with chlorine at point-of-use to improve water quality and reduce child diarrhea in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 76(2), 354–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell M, & Hsieh SD (2005). Six reasons why the waist-to-height ratio is a rapid and effective global indicator for health risks of obesity and how its use could simplify the international public health message on obesity. International journal of food sciences and nutrition, 56(5), 303–307. doi: 10.1080/09637480500195066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barquera S, Peterson KE, Must A, Rogers BL, Flores M, Houser R, … Rivera-Dommarco JA (2007). Coexistence of maternal central adiposity and childstunting in Mexico. Int J Obes, 31, 601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett MN, Romaguera D, & Giménez MA (2014). Prevalence and determinants of the dual burden of malnutrition at the household level in Puna and Quebrada of Humahuaca, Jujuy, Argentina. . Nutr Hosp, 29, 322–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra IN, Junior EV, Pereira RA, & Sichieri R (2015). Away-from-home eating: nutritional status and dietary intake among Brazilian adults. Public health nutrition, 18(6), 1011–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivins AW, Sumner T, Kumpel E, Howard G, Cumming O, Ross I, … Brown J (2017). Estimating infection risks and the global burden of diarrheal disease attributable to intermittent water supply using QMRA. Environmental science & technology, 51, 7542–7551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulé NG, Tremblay A, Gonzalez-Barranco J, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Lopez-Alvarenga JC, Despres JP, … Rios-Torres JM (2003). Insulin resistance and abdominal adiposity in young men with documented malnutrition during the first year of life. International journal of obesity, 27(5), 598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewis A, Chaodhary N, & Wutich A (2019). Low water access as a gendered physiological stressor: Blood pressure evidence from Nepal. Amer J Hum Biol, e23234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cairncross S, & Ensink JH (2013). Water, sanitation, hygiene and enteric infections in children. Archives of disease in childhood, 98(8), 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, & Sobsey MD (2012). Boiling as household water treatment in Cambodia: a longitudinal study of boiling practice and microbiological effectiveness. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 87(3), 394–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulled N, Singer M, & Dillingham R (2014). The syndemics of childhood diarrhoea: A biosocial perspective on efforts to combat global inequities in diarrhoea-related morbidity and mortality. Global public health, 9(7), 841–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A, Akhter N, Sun K, De Pee S, Kraemer K, Moench-Pfanner R, & al, e. (2011). Relationship of household food insecurity to anaemia in childrene aged 6–59 months among families in rural Indonesia. Annals of Tropical Pediatrics, 31, 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates J, Rogers BL, Blau A, Lauer J, & Roba A (2017). illing a dietary data gap? Validation of the adult male equivalent method of estimating individual nutrient intakes from household-level data in Ethiopia and Bangladesh. Food policy, 72, 27–42. [Google Scholar]