Abstract

Objective:

To identify factors associated with referral and enrollment in early intervention (EI) for infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS).

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 256 infants born with NAS (2006–2013) at a tertiary care hospital in (Springfield), Massachusetts, linking maternal-infant birth hospitalization records with Department of Public Health EI records. We calculated the percent of infants retained at each step in the EI enrollment process over the first 3 years of life. We conducted separate multivariable logistic regression analyses to identify factors associated with EI referral and enrollment.

Results:

Among mothers, 82% received medication-assisted treatment at delivery, 36% endorsed illicit drug use during pregnancy, and 76% retained custody of their child at discharge. Among infants, 77% were referred to EI and 48% were enrolled in services. Of infants discharged to biological parents, 81% were referred to EI versus 66% of infants discharged to foster care (p ≤ 0.05); this difference persisted in multivariable analysis [adjusted odds ratio, 2.30; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.09–4.86]. Infants in the highest tertile for length of stay had 2.70 times the odds of EI enrollment (95% CI, 1.37–5.31).

Conclusion:

Fewer than half of the eligible infants with NAS were enrolled in EI services. Discharge to a biological parent and longer hospital stay had the strongest associations with EI referral and enrollment, respectively. Efforts to improve EI referral rates during the birth hospitalization, particularly among infants discharged into foster care, and close follow-up for infants with shorter hospital stays would enhance the developmental supports for this vulnerable population.

Index terms: neonatal abstinence syndrome, early intervention, opioid use disorders

As opioid use has increased across the United States, the number of infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), a drug withdrawal syndrome experienced by up to 60% of opioid-exposed infants, has tripled over the past 15 years.1 NAS presents during the early postnatal period with a spectrum of neurologic and gastrointestinal symptoms, ranging from tremors and irritability to poor feeding, tachypnea, and seizures. In 2012, NAS affected 5.8 of every 1,000 hospital births in the United States,1 and in New England, the incidence of NAS was more than double the national average.2 The US Department of Health and Human Services also reported that the percent of children removed to foster care because of parental abuse of drugs more than doubled from 10% to over 30% between 2000 and 2016 across the United States.3 It is estimated that nearly half of substance-exposed newborns reported to the Massachusetts child protection services were placed in the custody of foster families or kinship care between 2010 and 2013.4

Infants with NAS are at increased risk for developmental delay and later behavioral, educational, and mental health problems.5–10 The perinatal period is both a critical window for women to seek treatment for addiction and to begin establishing strong parent-infant relationships. Among pregnant women in Massachusetts, over 60% receive pharmacotherapy for addiction in the year before delivery.11 Overdose rates were lowest in the third trimester in this population but increased steadily through 12 months postpartum, suggesting that the year after delivery is a vulnerable time for recovery.11 In an effort to ameliorate the developmental sequelae associated with NAS and maternal addiction, many states offer infants with NAS early intervention (EI) services under Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Beginning in 2004, this Act authorized states to provide EI services to infants and toddlers with or at risk of developmental delays and disabilities.12 In addition, beginning in 2009 in Massachusetts, NAS became an automatic qualifying diagnosis for EI services such that an infant with NAS may receive up to 1 year of EI services.

Across the United States, only approximately 25% of all eligible children receive EI services.13–15 Certain subpopulations, including African-American and Hispanic children and those with developmental delay, are even less likely to receive EI services compared with white infants and infants with established qualifying diagnoses or those born very preterm (<32 weeks).16–21 This low rate of enrollment is likely related in part to individual factors such as parental health beliefs and psychosocial stressors,22,23 as well as system-level factors involved in the EI referral and enrollment process. The hospital-based health care teams that provide initial care to infants with NAS are particularly well-positioned to initiate EI referrals, given the relatively long hospital stays experienced by these infants, as well as the engagement of multidisciplinary teams in maternal and infant care at this time.

Estimates of the proportion of eligible infants with NAS that enroll in EI services are limited. One study estimated that between 1998 and 2005, 61% of illegal drug-exposed infants with moderate to severe NAS requiring treatment in Massachusetts were referred to EI, and 89% of those evaluated by EI were found eligible. Although not all these infants carried the diagnosis of NAS, the authors hypothesize that the discrepancy in eligibility likely occurred because neonatal drug exposure history was not disclosed to the EI program during evaluation.24 As the number of infants with NAS continues to grow, estimates of EI referral and enrollment are increasingly important for program planning and monitoring access to services for infants and their families in recovery from opioid use disorders (OUDs). Understanding the factors associated with enrollment in EI services among the heterogeneous population of substance-exposed infants is necessary to guide the engagement and retention of families affected by OUDs. Recognizing that children discharged from hospital and into foster care may experience a number of challenges during the hospital-to-home transitions, understanding how EI referral and enrollment patterns differ among infants with NAS who are discharged into foster care is particularly important.25,26

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using maternal and infant hospital birth records from 1 tertiary care academic children’s hospital in Western Massachusetts, linked with EI enrollment data, to characterize enrollment patterns and to identify factors associated with EI enrollment among mother-infant dyads affected by NAS. We hypothesized that infant enrollment in EI would be positively associated with (1) retained maternal custody of her infant at the time of hospital discharge, (2) maternal receipt of medication-assisted treatment, and (3) maternal abstinence from illicit drugs during pregnancy, with all 3 of these factors representing the stability of the mother’s recovery from OUD or the overall functional assessment of the family home environment that is also conducive to recovery. EI referral was a necessary prerequisite for EI enrollment; hence, we examined completion of the referral to EI as a secondary outcome.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We extracted data from mother-infant dyads’ birth hospitalization records between July 2006 and July 2013 from a single tertiary care academic children’s hospital in (Springfield), Massachusetts, with approximately 4,000 births per year. The infants were either born in this hospital or had been transferred from a level 1 nursery because of a non-neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS)-related diagnosis requiring neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) care, difficulty capturing NAS despite maximizing treatment, or a complication secondary to NAS such as seizures. During this time period, infants with NAS symptoms requiring an escalation of nonpharmacologic or pharmacologic treatment were managed in the NICU. The hospital policy was to refer all infants with the NAS diagnosis cared for in the NICU to early intervention (EI) services, even before NAS became an automatic qualifying diagnosis for EI services beginning in 2009. Infants in this cohort were initially identified using ICD-9 diagnostic codes for “maternal drugs affecting newborns” or “neonatal abstinence syndrome,” 2 specific codes for substance-exposed infants.24,27 The electronic medical records (EMRs) were then reviewed for all infants with these ICD-9 codes, and only those with clinical diagnoses of NAS were included in the final cohort. Infants with chromosomal anomalies and those born <35 weeks gestational age, identified in the medical records, were excluded from the study because they would qualify for EI under these specific diagnoses. Infant and maternal data were obtained from the EMR and then linked to data from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH) EI database. This study was deemed exempt from review by the Baystate Health Institutional Review Board and the Massachusetts DPH Institutional Review Board.

Outcome Variable: Early Intervention Enrollment

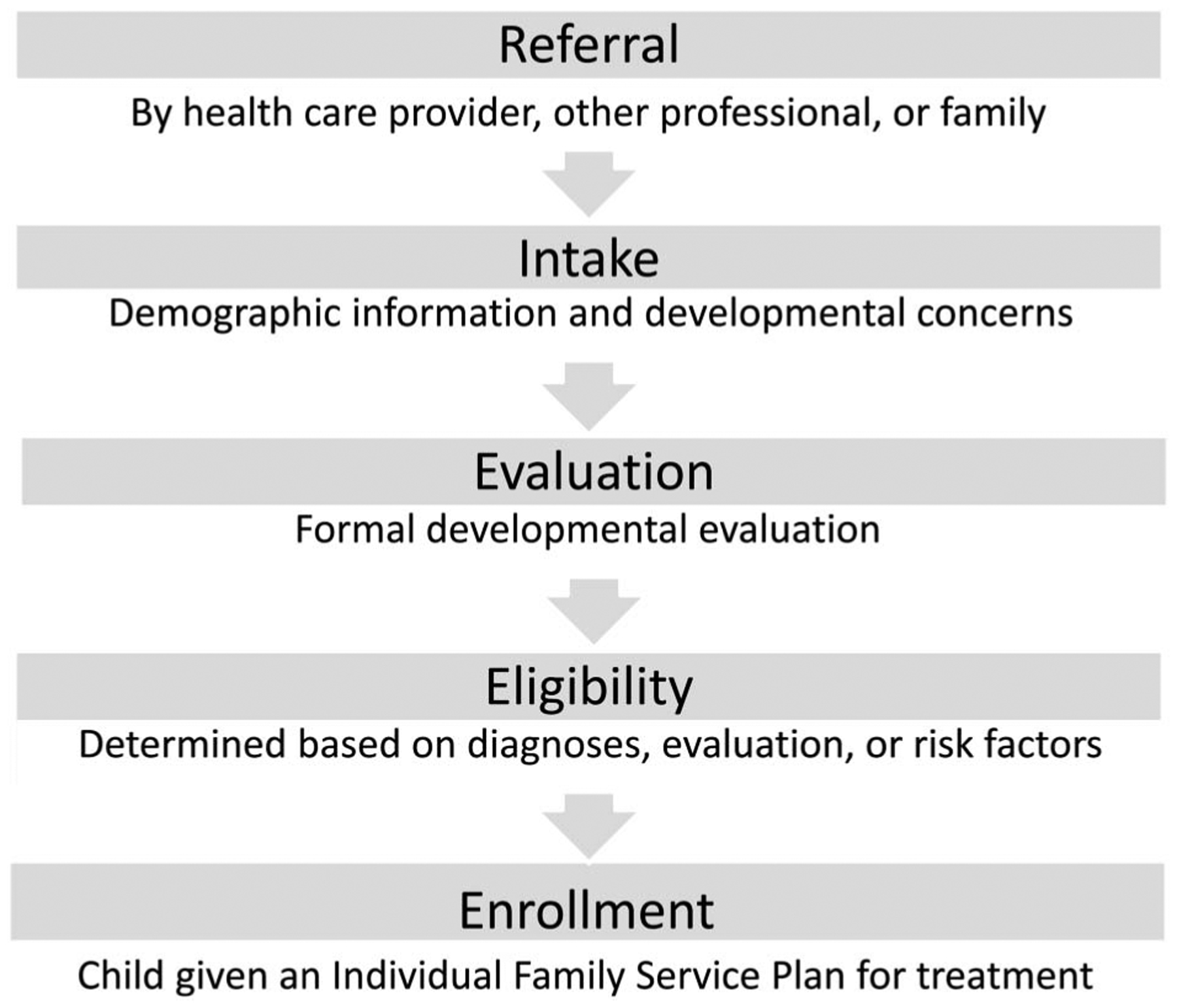

Enrollment in EI within the first 3 years of life was our primary outcome variable of interest. To enroll in EI, a family must complete a multistep enrollment process (Fig. 1), beginning with referral and moving through each subsequent step. Referral to EI was a necessary prerequisite for enrollment; hence, we examined completion of the referral to EI (referral identified within the EI database) as a secondary outcome. During the time period of this study, the NICU case manager made referrals to EI programs for all infants with NAS except when the child was in custody of the Department of Children and Families (DCF). In these cases, DCF was responsible for making the referral based on geographic location of foster family placements. Referrals were defined as incomplete if they were not identified in the EI database. For each study participant, completion of the furthest step along the pathway was categorized as follows: (1) referral to EI completed, (2) EI intake completed, (3) evaluated and eligibility determined, and (4) enrolled with an individualized family service plan (IFSP). Engagement in this process is voluntary, and a family could choose to decline a referral or withdraw from the process at any time. An EI evaluation consists of developmental testing with a validated measure conducted by trained EI providers. A child is deemed eligible if they meet any of the following criteria: a qualifying diagnosis (including NAS), developmental delay based on the validated measure, or at least 4 specified “family eligibility factors” such as prematurity, homelessness, domestic violence, or parental substance use disorder. An IFSP is a written treatment plan provided to eligible families that maps all the EI services that a child will receive, including how and when the services will be administered.28 Age of evaluation (months) and duration of services > 6 months were described for the subset of children enrolled in EI services.

Figure 1.

Stepwise process for early intervention enrollment.

Descriptor Variables

The following variables collected at the time of hospital discharge from the EMR were used to describe the cohort of infants with NAS and their mothers and to assess associations with EI referral and enrollment. Infant characteristics included race or ethnicity (categorized: non-Hispanic white, Hispanic/Latino, African-American, other, unknown), sex (male/female), birth weight (kg), gestational age (weeks and categories: 35 to <37, 37 to <39, and 39+), any period of hospitalization in the NICU (yes/no), length of hospital stay (weeks and tertiles), any breastfeeding during the hospitalization (yes/no), and NAS medication type [none, morphine (yes/no), phenobarbital (yes/no), and clonidine (yes/no)]. We selected 3 variables that reflect the stability of the mother’s recovery as recorded in the EMR: (1) enrollment in medication-assisted treatment (MAT); (2) illicit drug use in pregnancy (self-report or laboratory results for cocaine, heroin, oxycodone, or other not including marijuana); (3) discharge of the infant to the biological parent versus foster parent. There is unequivocal evidence that retention in MAT is associated with more stable recovery, and the inability to abstain from illicit drug use during pregnancy, when motivation to seek treatment is particularly high, has strong face validity as a marker of more severe addictive disorder. The custody determination by DCF involves a more global assessment of family functioning, safety, and the supportive nature of the home environment that is also conducive to recovery. Additional maternal characteristics included age (years), psychiatric diagnoses (bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, none), any psychiatric medications (yes/no), tobacco use in pregnancy (self-report, yes/no), marijuana use in pregnancy (self-report or laboratory result, yes/no), type of MAT medication (methadone, suboxone/buprenorphine), and duration of time in MAT (months) for those enrolled. These descriptor variables were selected based on the published literature about NAS risk and severity, clinical experiences, and our above-described hypotheses.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were calculated for infants born with NAS and their mothers (n = 256). Bivariate analyses were conducted to examine the associations between the maternal-infant characteristics listed above and our primary (EI enrollment) and secondary (EI referral) outcomes using χ2 test of independence, 2-sample t tests, and the non-parametric Wilcoxon 2-sample test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate for the given variable. We developed 2 separate multivariable logistic models to evaluate associations between each of our outcome variables and enrollment in MAT, illicit drug use during pregnancy, and discharge to biological versus foster parent, controlling for a priori variables associated with EI enrollment in the published literature (child race/ethnicity, sex, birth weight, and maternal age).14,17,18 In addition, we followed the model-building approach described by Hosmer et al.,29 screening additional covariates with a p value < 0.20 in unadjusted analyses and retaining any variables that resulted in >10% change in the point estimates. Phenobarbital treatment and maternal anxiety were evaluated for models predicting referral; breastfeeding, any maternal psychiatric medications, and length of infant hospital stay were evaluated for models predicting enrollment. Only length of stay remained in the enrollment model, analyzed in tertiles for the primary analysis and as a continuous variable in a sensitivity analysis.

RESULTS

Overall, the sample of infants (n = 256) was predominantly non-Hispanic white, with a mean gestational age of 38.9 weeks and mean birth weight of 3.0 kilograms (Table 1). The average length of hospital stay was 3.4 weeks, and almost all infants (96%) received medication treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Most infants received morphine plus phenobarbital or clonidine (90%). Less than a quarter of the sample breastfed, and approximately one-quarter were discharged to foster care. The mothers had a mean age of 28.3 years, approximately 40% had diagnoses of depression, and 82% were enrolled in medication-assisted treatment (MAT) with an average duration of MAT of 16.8 months. Approximately half endorsed tobacco use, and approximately a third engaged in illicit drug use during their pregnancy.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics and Bivariate Association with EI Referral and Enrollment (N = 256)

| Category | Total | EI Referrala | EI Enrollmenta | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 256 | No | Yes | pb | No | Yes | pb | |

| N = 59 | N = 197 | N = 133 | N = 123 | ||||

| N (Column Percent) or Mean (SD) | |||||||

| Child | |||||||

| Race/ethnicity | 39 (75.0) | 146 (76.0) | 0.86 | 88 (71.5) | 97 (80.2) | 0.14 | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 185 (72.3) | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 33 (12.9) | ||||||

| African-American | 9 (3.5) | ||||||

| Other | 17 (6.6) | ||||||

| Unknown | 12 (4.7) | ||||||

| Sex (male) | 136 (53.1) | 32 (54.2) | 104 (52.8) | 0.88 | 72 (54.1) | 64 (52.0) | 0.80 |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.0 (0.6) | 3.0 (0.5) | 2.9 (0.6) | 0.61 | 3.0 (0.5) | 2.9 (0.6) | 0.10 |

| Gestational age (wk) (N = 248) | 38.9 (1.7) | 38.9 (1.5) | 39.0 (1.7) | 0.94 | 39.0 (1.6) | 38.8 (1.7) | 0.27 |

| 35 to <37 | 19 (7.7) | ||||||

| 37 to <39 | 114 (46.0) | ||||||

| 39+ | 115 (46.4) | ||||||

| Length of hospital stay (wk) | 3.4 (1.7) | 3.2 (1.5) | 3.4 (1.7) | 0.66 | 3.2 (1.6) | 3.6 (1.7) | 0.01 |

| First tertile: 0.9—2.4 wk (N = 87) | 1.9 (0.4) | ||||||

| Second tertile: 2.6—3.6 wk (N = 80) | 3.0 (0.4) | ||||||

| Third tertile: 3.7–9.9 wk (N = 86) | 5.2 (1.5) | ||||||

| Any breastfeeding | 54 (21.1) | 11 (18.6) | 43 (21.8) | 0.72 | 33 (24.8) | 21 (17.1) | 0.17 |

| Medication for treatment | |||||||

| Morphine | 245 (95.7) | 58 (98.3) | 187 (94.9) | 0.47 | 129 (97.0) | 116 (94.3) | 0.36 |

| Phenobarbital | 181 (70.7) | 46 (78.0) | 135 (68.5) | 0.19 | 98 (73.7) | 83 (67.5) | 0.34 |

| Clonidine | 57 (22.3) | 11 (18.6) | 46 (23.4) | 0.48 | 31 (23.3) | 26 (21.1) | 0.76 |

| None | 10 (3.9) | ||||||

| Parental custody at hospital discharge | |||||||

| Biological parent | 195 (76.2) | 38 (64.4) | 157 (79.7) | 105 (79.0) | 90 (73.2) | 0.31 | |

| Foster parent | 61 (23.8) | 21 (35.6) | 40 (20.3) | 0.02 | 28 (21.1) | 33 (26.8) | |

| Mother | |||||||

| Age at time of infant birth (yr) (N = 252) | 28.3 (5.2) | 28.1 (5.0) | 28.3 (5.2) | 0.74 | 28.1 (5.0) | 28.4 (5.3) | 0.65 |

| Psychiatric diagnoses | |||||||

| Bipolar disorder | 39 (15.2) | 10 (17.0) | 29 (14.7) | 0.68 | 20 (15.0) | 19 (15.5) | 1.00 |

| Depression | 104 (40.6) | 25 (42.4) | 79 (40.1) | 0.76 | 53 (39.9) | 51 (41.5) | 0.80 |

| Anxiety | 69 (27.0) | 21 (35.6) | 48 (24.4) | 0.10 | 39 (29.3) | 30 (24.4) | 0.40 |

| Any psychiatric medications | 85 (33.2) | 22 (37.3) | 63 (32.0) | 0.53 | 38 (28.6) | 47 (38.2) | 0.11 |

| Enrolled in MAT | 211 (82.4) | 51 (86.4) | 160 (81.2) | 0.44 | 109 (82.0) | 102 (82.9) | 0.87 |

| MAT-specific medication | |||||||

| Methadone | 139 (54.3) | 35 (68.6) | 104 (65.0) | 72 (66.1) | 67 (65.7) | ||

| Suboxone/buprenorphine | 72 (28.1) | 16 (31.4) | 56 (35.0) | 0.74 | 37 (33.9) | 35 (34.3) | 1.00 |

| Duration in MAT, mo (N = 161) | 16.8 (17.5) | 13.9 (13.9) | 17.7 (18.5) | 0.49 | 16.3 (17.2) | 17.3 (18.0) | 0.80 |

| Tobacco use in pregnancy | 148 (57.8) | 37 (62.7) | 111 (56.4) | 0.45 | 75 (56.4) | 73 (59.4) | 0.70 |

| Marijuana use in pregnancy | 42 (16.4) | 9 (15.3) | 33 (16.8) | 1.00 | 21 (15.8) | 21 (17.1) | 0.87 |

| Any illicit drug use during pregnancy | 92 (35.9) | 21 (35.6) | 71 (36.0) | 0.91 | 43 (32.6) | 49 (40.2) | 0.24 |

| Cocaine | 42 (16.4) | ||||||

| Heroin | 8 (3.1) | ||||||

| Oxycodone | 41 (16.0) | ||||||

| Other | 1 (0.4) | ||||||

| Unknown | 2 (0.8) | ||||||

CI, confidence interval; EI, early intervention; MAT, medication-assisted treatment.

Of nonmissing values.

Fisher’s exact test or Wilcoxon 2-sample test.

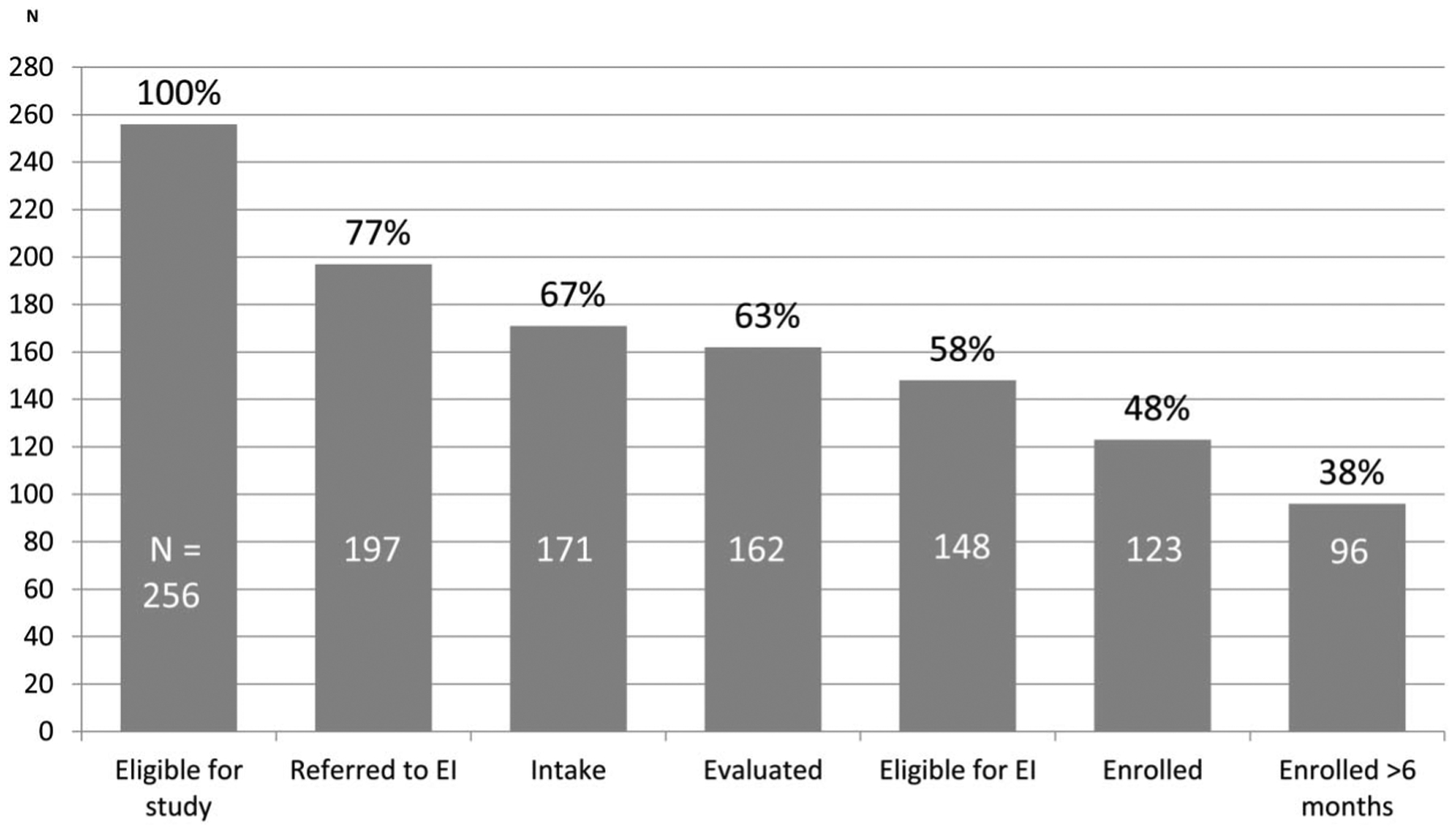

Retention in the Early Intervention Enrollment Process

Of the infants, 77% were referred to early intervention (EI), approximately two-thirds received an EI intake, and 5% were deemed ineligible for services (Fig. 2). Approximately half of infants with NAS enrolled in EI, and 38% sustained enrollment for longer than 6 months. The mean age of EI evaluation among enrolled infants was approximately 6 months, with 74% of infants receiving evaluations by 6 months of age (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Retention in EI enrollment process. EI, early intervention.

Figure 3.

Age of initial evaluation for infants enrolled in EI. EI, early intervention.

Completion of Early Intervention Referral

In bivariate analyses, only custody status (biologic parent vs foster parent) was significantly associated with greater referral. Of infants discharged to biological parents, 81% were referred to EI versus 66% of infants discharged to foster parents (p ≤ 0.05). This difference persisted in multivariable analysis [adjusted odds ratio (aOR), 2.30; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.09–4.86] controlling for a priori variables (Table 2). No other variables met criteria for inclusion in the regression model.

Table 2.

Separate Multivariable Logistic Regression Models for EI Referral and EI Enrollment

| Maternal-Infant Characteristics | EI Referral (N = 242)b | EI Enrollment (N = 239)b |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| MAT enrollment (yes vs no) | 0.82 (0.29–2.33) | 0.98 (0.41–2.36) |

| Drug use in pregnancy (yes vs no) | 1.33 (0.59–3.03) | 1.46 (0.73—2.91) |

| Discharge custody | 2.30 (1.09–4.86)a | 0.76 (0.38—1.52) |

| Biological parent vs foster parent | ||

| Length of hospital stay (wk) | ||

| Reference (first tertile) | — | 1.00 |

| Second tertile | — | 1.39 (0.71—2.73) |

| Third tertile | — | 2.70 (1.37—5.31)a |

p = 0.05.

Adjusting for infant sex, birth weight (kg), ethnicity, maternal age (yr). EI, early intervention; MAT, medication-assisted treatment; OR, odds ratio.

Early Intervention Enrollment

In bivariate analyses, average length of hospital stay had the strongest association with EI enrollment. Average hospital stay was 3.6 versus 3.2 weeks (Table 1) for those enrolled versus not enrolled in EI (p ≤ 0.05). Infants in the top tertile for length of hospital stay (ranging from 3.7 to 9.9 weeks) had 2.70 (95% CI, 1.37–5.31) times increased odds of being enrolled in EI compared with those in the first tertile after controlling for the variables related to stability of maternal recovery and a priori variables (Table 2). In our sensitivity analysis in which we examined length of stay as a continuous variable, this association demonstrated an attenuated linear association whereby each additional week of hospitalization was associated with 19% increased odds of EI enrollment (aOR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.00–1.41). None of the variables reflective of the stability of maternal recovery (MAT enrollment, illicit drug use in pregnancy, and custody status) were associated with EI enrollment (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that nearly half of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) born at a tertiary care hospital between 2006 and 2013 were enrolled in early intervention (EI) services. A steady attrition of eligible infants was noted at each step in the EI enrollment process, from referral to intake to evaluation to enrollment. The average age of initial evaluation was approximately 6 months, and approximately 80% of infants were evaluated by 12 months of age. In adjusted analysis, only discharge to a biological parent was independently associated with higher rates of referral to EI when compared with discharge to a foster parent. Infants in the top tertile for length of hospital stay were most likely to enroll in EI, even after adjusting for confounders. Stability of maternal recovery during the birth hospitalization (e.g., maternal enrollment in medication-assisted treatment, abstinence from illicit drugs in pregnancy) can affect clinical outcomes for substance-exposed infants30,31; however, our study did not find any association between stability of recovery and ultimate EI enrollment. Although the reason for this lack of association requires future study, these results suggest that other factors, possibly related to perceived need for services, may drive voluntary enrollment of infants with NAS as has been the case in other populations.22

The percent of infants with NAS enrolled in EI programs was higher than estimates of children at risk of developmental delay among the general population17 and near the range of infants in Massachusetts with clear diagnoses such as prematurity (range, 23.5%–44%).14,15 Our cohort represents a clinically detected population of infants with NAS as evidenced by the high rate of medication treatment for NAS symptoms and hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit. Rates of referral and enrollment in EI would likely be lower for substance-exposed infants who are not diagnosed with NAS during their birth hospitalization. Massachusetts also has more inclusive EI eligibility criteria compared with other states, so these rates of enrollment are difficult to compare with national cohorts.13

The rate of referral and proportion eligible for EI services in this cohort were similar, although slightly higher than estimates for substance-exposed infants in Massachusetts from 1998 to 200524 despite the policy change expanding eligibility to infants at risk for developmental delay in 2004 and the automatic eligibility of infants with an NAS diagnosis beginning in 2009. The similarity in our rates of EI enrollment to those reported by Derrington are likely related to the comparable methods used for identifying substance-exposed infants by diagnosis codes. The higher rate of EI enrollment of infants with NAS compared with children with screen-detected developmental delay could be due, in part, to early referral to EI during the birth hospitalization, as well as earlier engagement of health professionals or child protective services in the provision of social and developmental supports. However, in both studies, 5% to 10% of eligible infants were found ineligible by EI, suggesting that there is a failure to communicate the NAS diagnosis or other risk factors to EI programs by medical providers and that families chose not to disclose. In our cohort, 13 of the 14 ineligible infants were evaluated after the change to automatic EI eligibility with NAS diagnosis in 2009; however, the number of infants evaluated pre-2009 was too small to definitively determine the impact of this policy change.

We have shown that the odds of EI referral are approximately 2-fold higher among children discharged to biological parents compared with children discharged to foster care. A lower rate of referral to EI for infants discharged to foster care has not been previously reported in the literature. The confidence interval for the odds ratio in this study is somewhat wide, indicating some degree of imprecision arising from the imbalance in exposure groups, thus warranting replication in future studies. It is also possible that observed differences in referral rates were due to differences in the referral process at our hospital, where infants discharged with their biological mothers are referred to EI by hospital personnel using a structured process, whereas referrals for infants discharged into foster care are made by the Department of Children and Families (DCF). Our findings do align with 2 recent studies demonstrating that children discharged from hospital into foster care experience a number of challenges at the time of hospital discharge, including poor communication between DCF, the hospital, and the children’s caregivers; inconsistent discharge processes; and increased odds of caregiver misunderstandings about children’s postdischarge care needs.25,26 Children in foster care may move multiple times to different families and cities, initially complicating the EI referral process. A recent study by Merhar et al.10 suggested that children who remained in foster/adoptive care scored higher on cognitive testing at 2 years of age. However, given frequent reunification of infants with biological parents and the risk of care fragmentation and developmental delay among infants with NAS in foster care, concerted efforts by health care teams and child protective services to address the care coordination needs of this vulnerable population are needed.

Longer hospital stay had the strongest association with EI enrollment in this cohort. A longer hospitalization in the case of pharmacologically treated infants with NAS is closely associated with severity of NAS symptoms when using traditional treatment guidelines for weaning medication.32,33 Longer hospitalization could also be a marker of overall severity of illness, including other comorbid conditions. Perceptions of the infant’s severity of illness on the part of medical professionals and the parents may result in a greater perceived need for EI services. These perceptions were not captured in this retrospective chart review study but are a known driver of EI engagement.22,34 In addition, longer stays in the hospital may affect EI enrollment in multiple ways, for example, the longer hospitalization could result in greater trust and relationship building between families and health care providers. This trust may result in increased motivation for families to follow through with EI referrals.

Although infants with longer lengths of stay were more likely to ultimately enroll in EI, our results demonstrate loss of eligible infants during each stage of the enrollment process. These findings are consistent with previous studies23,24 and highlight the need for future community-based research to determine reasons for suboptimal EI enrollment in this high-risk population. This type of attrition is common in other fields with similar stepwise processes required for accessing screening, diagnosis, and treatment.35 The HIV literature, which coined the description of this phenomenon as the “treatment cascade,” shows that the attrition of patients at each step in the treatment process is not random; rather, it is influenced by multiple societal and individual factors.35,36 Similar factors may contribute to the loss of eligible infants from the EI enrollment process and warrant further study. Interestingly, factors associated with EI enrollment in other studies (e.g., infant race/ethnicity, sex, birth weight, or maternal age) were not associated with enrollment in this population of infants with NAS.

Significant progress is being made to improve hospital-based management of NAS symptoms and the referral process to EI during the birth hospitalization. Treatment of infants in outpatient settings,37,38 use of first-line nonpharmacologic therapies,39 and alternative methods for assessing NAS symptoms40 have all resulted in shorter lengths of birth hospitalizations. Although these practices clearly have benefits for parent-infant bonding and cost reduction, this study suggests that greater attention and support may be needed during hospitalization to facilitate referrals to EI and other outpatient programs as the typical length of hospitalization decreases. Some hospital and EI systems are testing different strategies for EI engagement to improve the referral process for infants with NAS. These strategies include EI providers meeting with mothers prenatally to provide referrals to local resources if there are known qualifying risk factors such as depression and substance use disorders41 or providing the first introduction to EI providers in the hospital rather than following discharge of infants with NAS. Future studies are needed to assess the impact of these recent changes on EI referral and enrollment. Ensuring equitable access to services that support vulnerable children during critical windows of development must remain a high priority.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this cohort comes from 1 large tertiary care hospital in 1 state with specific protocols and practices as well as state-specific EI eligibility criteria that cannot necessarily be generalized nationally. Second, the collection of data from retrospective chart review is subject to misclassification bias from imperfect documentation. For example, the identification of infants by ICD-9 code likely misclassified substance-exposed infants with less severe or no NAS symptoms. However, we are reassured that all infants meeting our ICD-9 inclusion criteria had a clinical diagnosis of NAS by review of the electronic medical record. In addition, the mother-infant characteristics included were limited to variables available in the mother and infant health records. Greater detail regarding the timing and number of EI referrals, as well as descriptors of people placing referrals or the developmental assessments performed in EI would also be beneficial. Clearly, other factors such as personal beliefs, characteristics of the home environment, and maternal relapse were not collected in this study and could also drive engagement with child developmental services after discharge. Additional variables such as educational attainment, socioeconomic status, housing stability, and social support could not be consistently captured for the entire cohort, although they have been show to impact EI enrollment.14,42,43 Future prospective and longitudinal studies could assess the association of these psychosocial factors, well child care attendance, and ongoing developmental or medical problems with EI enrollment over the time period of EI eligibility.

CONCLUSION

Over half of eligible infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome did not enroll in early intervention (EI) services. Custody status by the biologic parent was most strongly associated with higher rate of EI referral, and longer hospital stay was associated with EI enrollment. Stability of maternal recovery is frequently used to determine the need for additional child development support services; however, our study shows that these factors were not associated, positively or negatively, with ultimate enrollment in EI programs. Future studies are needed to explore why longer hospital stays were associated with EI enrollment as well as to identify postdischarge factors that influence enrollment over time. Efforts to improve the hospital-to-home transitions by improving referral rates during the birth hospitalization and close follow-up of EI enrollment after discharge for infants with shorter hospital stays may enhance developmental supports for this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Award Number 1KL2TR002545. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehman CU, et al. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. J Perinatol. 2015;35:667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ko JY, Patrick SW, Tong VT, et al. Incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome—28 states, 1999–2013. 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6531a2.htm. Accessed March 16, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghertner R, Baldwin M, Crouse G, et al. The Relationship between Substance Use Indicators and Child Welfare Caseloads. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.França UL, Mustafa S, McManus ML. The growing burden of neonatal opiate exposure on children and family services in Massachusetts. Child Maltreat. 2016;21:80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oei JL, Melhuish E, Uebel H, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and high school performance. Pediatrics. 2017;139:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ornoy A, Michailevskaya V, Lukashov I, et al. The developmental outcome of children born to heroin-dependent mothers, raised at home or adopted. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20: 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckwith AM, Burke SA. Identification of early developmental deficits in infants with prenatal heroin, methadone, and other opioid exposure. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54:328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandstra ES, Morrow CE, Mansoor E, et al. Prenatal drug exposure: infant and toddler outcomes. J Addict Dis. 2010;29:245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fill MA, Miller AM, Wilkinson RH, et al. Educational disabilities among children born with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. 2018;142:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merhar SL, McAllister JM, Wedig-Stevie KE, et al. Retrospective review of neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants treated for neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Perinatol. 2018;38:587–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Terplan M, et al. Fatal and nonfatal overdose among pregnant and postpartum women in Massachusetts. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:466–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act. In. 20 U. S.C. Section 1400 Pub. L. No. 108–4462004.

- 13.Rosenberg SA, Robinson CC, Shaw EF, et al. Part C early intervention for infants and toddlers: percentage eligible versus served. Pediatrics. 2013;131:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro-Mendoza C, Kotelchuck M, Barfield W, et al. Enrollment in early intervention programs among infants born late preterm, early term, and term. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e61–e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diop H, Gopal D, Cabral H, et al. Assisted reproductive technology and early intervention program enrollment. Pediatrics. 2016;137: e20152007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg SA, Zhang D, Robinson CC. Prevalence of developmental delays and participation in early intervention services for young children. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1503–e1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feinberg E, Silverstein M, Donahue S, et al. The impact of race on participation in part C early intervention services. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2011;32:284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khetani MA, Richardson Z, McManus BM. Social disparities in early intervention service use and provider-reported outcomes. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2017;38:501–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javalkar K, Litt JS. Reason for referral predicts utilization and perceived impact of early intervention services. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2017;38:706–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barfield WD, Clements KM, Lee KG, et al. Using linked data to assess patterns of early intervention (EI) referral among very low birth weight infants. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12: 24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clements KM, Barfield WD, Kotelchuck M, et al. Birth characteristics associated with early intervention referral, evaluation for eligibility, and program eligibility in the first year of life. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magnusson DM, Minkovitz CS, Kuhlthau KA, et al. Beliefs regarding development and early intervention among low-income African American and Hispanic mothers. Pediatrics. 2017;140:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peacock-Chambers E, Silverstein M. Health beliefs and the developmental treatment cascade. Pediatrics. 2017;140:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derrington TM. Development of the drug-exposed infant identification algorithm (DEIIA) and its application to measuring part C early intervention referral and eligibility in Massachusetts, 1998–2005. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:1567–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martens A, DeLucia M, Leyenaar JK, et al. Foster caregiver experience of pediatric hospital-to-home transitions: a qualitative analysis. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18:928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeLucia M, Martens A, Leyenaar J, et al. Improving hospital-to-home transitions for children entering foster care. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8:465–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patrick SW, Burke JF, Biel TJ, et al. Risk of hospital readmission among infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5:513–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP). Division of children & youth with special needs, Massachusetts department of public health. 2018. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/gov/departments/dph/programs/family-health/directions/chap-8/the-individualized-family-service-plan-ifsp.html. Accessed January 19, 2018.

- 29.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression In: Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. 3rd ed Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hwang SS, Diop H, Liu CL, et al. Maternal substance use disorders and infant outcomes in the first year of life among Massachusetts singletons, 2003–2010. J Pediatr. 2017;191:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kotelchuck M, Cheng ER, Belanoff C, et al. The prevalence and impact of substance use disorder and treatment on maternal obstetric experiences and birth outcomes among singleton deliveries in Massachusetts. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:893–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lainwala S, Brown ER, Weinschenk NP, et al. A retrospective study of length of hospital stay in infants treated for neonatal abstinence syndrome with methadone versus oral morphine preparations. Adv Neonatal Care. 2005;5:265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kocherlakota P Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. 2014; 134:e547–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Little AA, Kamholz K, Corwin BK, et al. Understanding barriers to early intervention services for preterm infants: lessons from two states. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:430–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, et al. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 52:793–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kay ES, Batey DS, Mugavero MJ. The HIV treatment cascade and care continuum: updates, goals, and recommendations for the future. AIDS Res Ther. 2016;13:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee J, Hulman S, Musci M, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: influence of a combined inpatient/outpatient methadone treatment regimen on the average length of stay of a Medicaid NICU population. Popul Health Manag. 2015;18:392–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Backes CH, Backes CR, Gardner D, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: transitioning methadone-treated infants from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Perinatol. 2012;32:425–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmes AV, Atwood EC, Whalen B, et al. Rooming-in to treat neonatal abstinence syndrome: improved family-centered care at lower cost. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20152929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grossman MR, Berkwitt AK, Osborn RR, et al. An initiative to improve the quality of care of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20163360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Early Intervention Partnership Programs (EIPP)—Overview. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/gov/departments/dph/programs/family-health/early-intervention-partnerships-program/overview.html. Accessed January 19, 2018.

- 42.Sutter MB, Gopman S, Leeman L. Patient-centered care to address barriers for pregnant women with opioid dependence. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nardi DA, Rooda LA. The use of a multicultural conceptual model in perinatal addiction treatment. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 1996;8: 68–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]