Summary

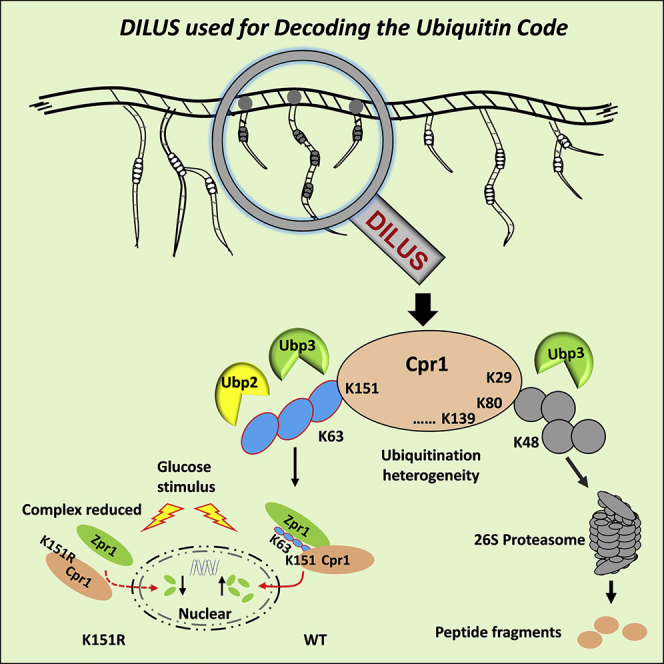

Ubiquitin chain specificity has been described for some deubiquitinases (DUBs) but lacks a comprehensive profiling in vivo. We used quantitative proteomics to compare the seven lysine-linked ubiquitin chains between wild-type yeast and its 20 DUB-deletion strains, which may reflect the linkage specificity of DUBs in vivo. Utilizing the specificity and ubiquitination heterogeneity, we developed a method termed DUB-mediated identification of linkage-specific ubiquitinated substrates (DILUS) to screen the ubiquitinated lysine residues on substrates modified with certain chains and regulated by specific DUB. Then we were able to identify 166 Ubp2-regulating substrates with 244 sites potentially modified with K63-linked chains. Among these substrates, we further demonstrated that cyclophilin A (Cpr1) modified with K63-linked chain on K151 site was regulated by Ubp2 and mediated the nuclear translocation of zinc finger protein Zpr1. The K48-linked chains at non-K151 sites of Cpr1 were mainly regulated by Ubp3 and served as canonical signals for proteasome-mediated degradation.

Subject Areas: Molecular Biology, Omics

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Quantitative proteomics is used to reflect DUB's linkage specificity in vivo

-

•

DILUS is developed to decode the ubiquitin code on the level of ubiquitinated sites

-

•

K63 chains on K151 of Cpr1 regulated by Ubp2/Ubp3 mediates Zpr1's nuclear transition

-

•

K48 chains on non-K151 of Cpr1 regulated by Ubp3 controls its proteasomal proteolysis

Molecular Biology; Omics

Introduction

The covalent attachment of ubiquitin onto substrate proteins is a universal eukaryotic post-translational modification (PTM) (Hershko et al., 2000). This regulatory system underlies the precise control of a broad spectrum of cellular processes including protein degradation, gene transcription, and cell cycle progression (Hoeller and Dikic, 2009, Komander and Rape, 2012). The precise regulation of cellular processes by the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) relies on the substrate specificity of hundreds of UPS enzymes.

The seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63) and N-terminus of ubiquitin can be conjugated by other ubiquitin moieties to form eight types of chains with distinct topologies (Kulathu and Komander, 2012). There is growing evidence that ubiquitin chains bearing different linkages have distinct biological functions, referred to as the “ubiquitin code” (Komander and Rape, 2012). The two main outputs of UPS have been the protein turnover control and governance of cell signaling networks by regulation of protein localization, interactions, and activities. For example, K48-linked chain is a predominant linkage and serves as canonical signals for proteasomal degradation (Komander and Rape, 2012); K63-linked chains perform various non-degradative roles and participate in endosomal trafficking, intracellular signaling, and DNA repair (Ikeda and Dikic, 2008, Kulathu and Komander, 2012, Spence et al., 1995); K11-linked chains are involved in cell division, transcription regulation, and endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) (Li et al., 2019, Min et al., 2015, Xu et al., 2009). For atypical chains, K6-linked chain is involved in mitophagy regulation (Gersch et al., 2017); K27-linked chains act as recruiting proteins for DNA repair and immune response (Wang et al., 2014); K33-linked chains have been implicated in cell-surface-receptor-mediated immunity, signal transduction, and protein trafficking (Huang et al., 2010, Yuan et al., 2014). In addition, branched ubiquitin chains and ubiquitin with other PTMs have been recently recognized (Stolz and Dikic, 2018). This diversity of function reflects the varieties of the ubiquitin chain structures that are specifically recognized by ubiquitin receptors (Husnjak and Dikic, 2012, Kulathu and Komander, 2012).

The formation of ubiquitin chains is regulated by ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s) and ubiquitin ligases (E3s) (Chen et al., 2019, Finley et al., 2012), whereas the detachment of ubiquitination is mediated by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) (Clague et al., 2019). To date, 21 and approximately 100 DUBs have been identified in the genomes of S. cerevisiae and humans, respectively (Abdul Rehman et al., 2016, Clague et al., 2013, Nijman et al., 2005). Some DUBs display selectivity and specificity for particular ubiquitin linkages or cleaving positions within ubiquitin chains, whereas others show linkage ambiguity, mainly due to substrate selectivity via specific protein-protein interactions mediated through domains outside of the catalytic domain (Clague et al., 2019). The linkage specificities of human DUBs in the ubiquitin-specific protease (USP) and ovarian tumor (OTU) families have been systematically characterized in vitro (Faesen et al., 2011, Mevissen et al., 2013, Mevissen and Komander, 2017). Generally, the USP DUBs are not linkage but substrate specific (Faesen et al., 2011, Ritorto et al., 2014). By contrast, the OTU family DUBs display preference to diverse chains, unveiling the specificity rules of DUBs toward linkage (Mevissen et al., 2013). However, the Ub-linkage specificity in vivo is expected to be more complex and less explored because of DUBs' subcellular localization and PTMs, as well as the involvement of co-factors. DUBs are subjected to spacious and temporary regulation and can act as both negative and positive regulators in the ubiquitination system. Therefore, systematic analysis of the specificity of DUBs for ubiquitin linkages and substrates in vivo remains a challenge. Furthermore, for substrates with multiple ubiquitin chains, individual sites of ubiquitination may be modified by chains of different linkages and regulated by distinct DUBs. Therefore, it also remains challenging but deeply in demand to directly identify the modification sites on substrates, the ubiquitin chains, and corresponding enzymes involved in the modification process.

In this study, we combined yeast genetics and quantitative proteomics approaches to characterize the accumulation of seven lysine-linked ubiquitin chains in each DUB deletion strain, which might reflect the linkage specificity of DUBs in vivo. Utilizing the linkage specificity of certain DUBs, we developed a method termed DUB-mediated identification of linkage-specific ubiquitinated substrates (DILUS), which allowed us to build a network of specific protein substrates and their corresponding ubiquitinated lysine residues with certain ubiquitin linkages regulated by particular DUBs. After generating two large-scale datasets of the substrates and their ubiquitinated residues potentially modified with K63-linked chains for Ubp2, we further confirmed cyclophilin A (Cpr1) as an Ubp2 substrate that was modified with K63-linked chains at residue K151. These K63-linked ubiquitin chains could bind Zpr1 to trigger its nuclear translocation on the condition of glucose stimulus after starvation. However, the K48-linked chains at non-K151 sites of Cpr1 were mainly regulated by Ubp3 and mediated the degradation through proteasome.

Results

Quantitative Proteomics Reveals Ubiquitin Chain Specificity of DUBs In Vivo

Although ubiquitin modifies thousands of proteins in yeast (Gao et al., 2016, Peng et al., 2003, Swaney et al., 2013), only 21 DUBs are known to be involved in deubiquitination. The budding yeast has five families of DUBs namely ubiquitin-specific proteases (USP, Ubp1–16), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCH, Yuh1), ovarian tumor proteases (OTU, Otu1 and Otu2), JAB1/MPN/Mov34 metalloenzymes (JAMM, Rpn11) (Finley et al., 2012, Nijman et al., 2005), and a recently discovered MINDY protease (Miy1) (Abdul Rehman et al., 2016, Kristariyanto et al., 2017). As RPN11 (POH1 in human) is an essential gene in budding yeast (Finley, 2009), it is not included in this study.

First, we quantified the total ubiquitination level in WT and 20 DUB-deletion strains (Table S1) by performing western blotting and SILAC-based quantitative proteomics on total cell lysate (TCL) level (Figure S1). Both orthogonal methods showed different degrees of ubiquitinated protein accumulation in some DUB deletion strains such as ubp3Δ, ubp7Δ, and ubp14Δ, while being reduced in ubp8Δ, ubp15Δ, and miy1Δ strains (Figures S1B, S1C, and S1E). Next, the seven lysine-linked ubiquitin chains were globally compared in WT and DUB-deletion strains on the ubiquitin conjugates (UbC) level (Figure 1). The purified UbC was separated into three fractions based on molecular weight (<10, 10–50, and >50 kDa roughly representing mono ubiquitin, free ubiquitin chains, and ubiquitin conjugates, respectively) and then analyzed using a highly sensitive MS method called selective reaction monitoring (SRM) (Xu et al., 2009). In the <10 kDa section, the absence of some DUBs resulted in the accumulation of ubiquitin pool. However, the lack of proteasomal DUB Ubp6 led to a decrease of free ubiquitin, which was similar to a previous report (Nijman et al., 2005) (Figure S2A). In the 10–50 kDa section, UBP14 (USP5 in human) deletion resulted in a 30-fold increase in the abundance of K29- and K48-linked chains, but no significant changes in the abundance of K63-linked chains (Figure S2B). Our result is consistent with the previous reports that Ubp14 hydrolyzes unanchored ubiquitin chains (Amerik and Hochstrasser, 2004, Reyes-Turcu et al., 2009) and moreover indicates that the influence of Ubp14 on free chains is strongly linkage specific.

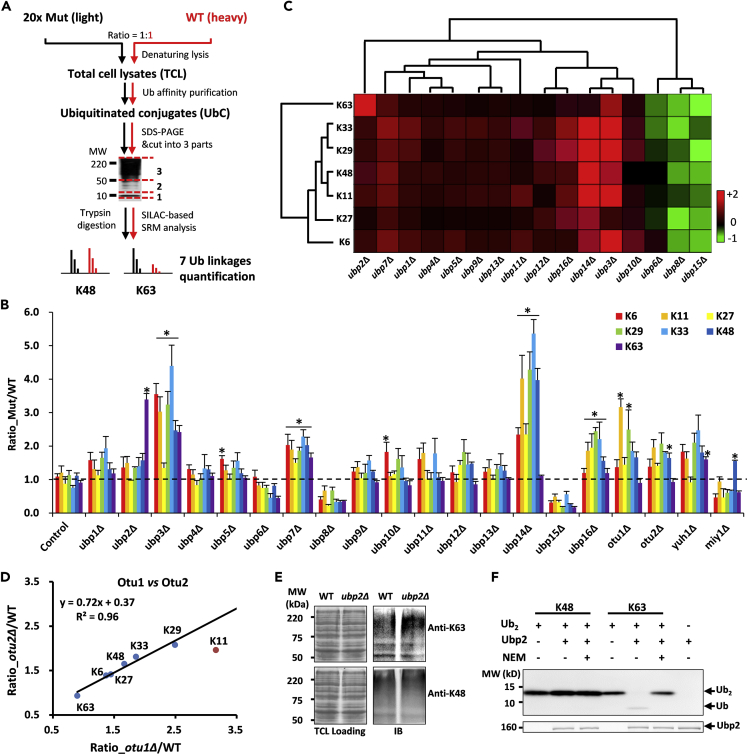

Figure 1.

Quantitative Proteomics of DUB-Deletion Strains Reveals Ubiquitin Linkage Specificity of Ubp2 for K63-Linked Chain

(A) Schematic of SILAC-based quantitative proteomics used to quantify ubiquitin chains in DUB-deletion strains. Equal amounts of light- and heavy-isotope-labeled yeast of DUB-deletion and WT strains were mixed for LC-MS/MS analysis. Enriched ubiquitinated conjugates (UbC) under denatured conditions were separated into three fractions according to molecular weight (i.e., <10, 10–50 and >50 kDa). The seven ubiquitin chains were relatively quantified through selected reaction monitoring (SRM) technology.

(B) Ubiquitin chains in fraction 3 (MW > 50 kDa) were collected and measured by MS. Data were shown as mean ± SEM of relative ratios for DUB-deletion and WT strains. Control and dotted line stand for quantification of equal light and heavy WT cells. The asterisk for significantly increased chains passed the t-test (p-value <0.05).

(C) Hierarchical clustering analysis of seven ubiquitin chains quantification for each USP DUB-deletion strain (red, upregulation; green, downregulation; black, no change). The quantitative values were derived from panel (B).

(D) The seven chains accumulation comparison between OTU1- and OTU2-deletion strains.

(E) Ubp2 deletion resulted in the accumulation of K63- but not K48-linked chains. WT and ubp2Δ strains were harvested for immunoblotting with K63 (up) and K48 (down) chain-specific antibodies.

(F) Ubp2 specifically cleaves K63- but not K48-linked chains in vitro. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 5 min before immunoblotting with monoclonal anti-ubiquitin antibody. Image was visualized by ECL.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

In the sector above 50 kDa, deletion of some DUBs (except Ubp6, Ubp8, Ubp15, and Miy1) resulted in significant accumulation of ubiquitination (Figure 1B). Most USP DUBs, such as Ubp1, Ubp7, and Ubp12, did not display obvious chain preferences. We also noticed that UBP3 deletion resulted in the accumulation of all of the chains except K27, whereas deletion of UBP2 specifically accumulated the K63 chain more than the other six chains. As for the recently reported MINDY DUBs in yeast, deletion of MIY1 resulted in decreasing of overall ubiquitination level (Figure S1C), whereas the K48 chain levels obviously increased (Figure 1B).

In S. cerevisiae, only two open-reading frames encode OTU domain proteins (Otu1 and Otu2). Otu1 is orthologous to the human OTUD2 (38% identical in the OTU domain). It is reported through an in vitro assay that Otu1 and OTUD2 have similar biases toward atypical linkages, including K11, K27, K29, and K33 chains (Mevissen et al., 2013), while having a strong preference toward K11-linked chains. Interestingly, we found that OTU1 and OTU2 deletions caused similar accumulation patterns for six ubiquitin chains except K11-linked chains. The otu1Δ mutant accumulated more K11-linked chains than the otu2Δ strain (Figure 1D). Despite possible side effects of DUBs deletions in vivo, the observed specificities of DUBs toward ubiquitin linkages were consistent between in vivo and in vitro studies.

Ubp2 Preferentially Regulates K63-Linked Chains

Ubp2 is reported to preferentially bind K63- over K48-linked chains and antagonize Rsp5-mediated assembly of K63-linked chains (Kee et al., 2005, Kee et al., 2006). Our analysis also proved that UBP2 deletion selectively increased the abundance of K63-linked chains compared with the other chains (Figures 1B and 1C). Additionally, across the 20 DUB-deletion strains, the abundance of K63-linked chains was presented as the highest accumulation in the ubp2Δ strain. We further confirmed this preference accumulation of the K63-linked instead of K48-linked chains in ubp2Δ by linkage specific antibodies on TCL (Figure 1E). Furthermore, we characterized Ubp2 activity by performing in vitro deubiquitination assays. The result showed that Ubp2 cleaved K63-linked chains with high activity while having little effect on K48-linked chains (Figure 1F). These pieces of evidence indicated that Ubp2 specifically participated in the regulation of substrates, which modified with K63-linked chains in yeast.

Ubp2 Substrate Profiling by DILUS Strategy

To fully characterize the regulatory mechanism of a given DUB or E3, it is often necessary to screen its regulated substrates and further distinguish their relevant ubiquitination sites. The classical proteomic strategy to systematically screen the substrates of these UPS enzymes is comparing the difference of the ubiquitinated conjugates before and after that enzyme overexpression or knockout (Raman et al., 2015, Silva et al., 2015, Xu et al., 2009, Zhuang et al., 2013). However, the ubiquitination heterogeneity shows that multiple lysine residues of the substrate are modified with diverse chains. Therefore, in addition to upregulated UbC levels (Figure 2A, class Ⅰ), upregulated modified sites without changes in UbC levels (Figure 2A, class Ⅱ, k1 site) in the ubp2Δ strain are also potential substrates of Ubp2. Combined with the specificity and ubiquitination heterogeneity, we developed a differential display strategy termed DILUS aimed at identifying Ubp2-regulated substrates and modification sites. Because the Ubp2 deletion specifically accumulated the K63-linked chain, upregulated sites were potentially modified with K63-linked chains with high possibility. In addition, we quantified the proteome of the ubp2Δ and WT through SILAC and eliminated the false-positive targets that were also increased on TCL levels (Table S2).

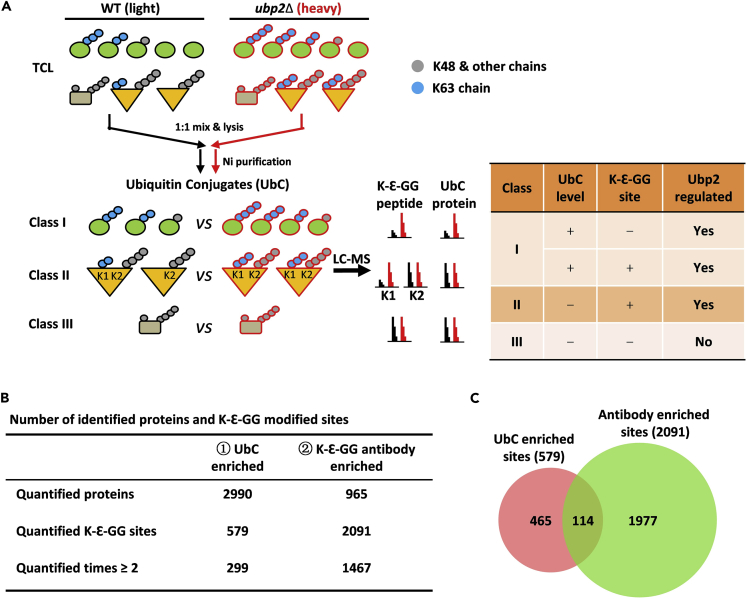

Figure 2.

DUB-Mediated Identification of Linkage-Specific Ubiquitinated Substrates (DILUS) Requires Deep Coverage of the K-Ɛ-GG-Modified Sites

(A) Schematic diagram of DILUS strategy used to directly screen for Ubp2-regulated substrates and sites potentially modified with K63-linked chains. All of the ubiquitin conjugates were divided into three classes and only classes I and II are true targets of Ubp2. After trypsin digestion, ubiquitin modified substrates will produce ubiquitin-remnant-containing (K-Ɛ-GG) peptides. In class I, Ubp2 deletion resulted in increased levels of UbC with or without increased K-Ɛ-GG peptides identified. In class II, only the level of K-Ɛ-GG peptides (modified site lysine K1) impacted by Ubp2 would increase, whereas other K-Ɛ-GG-modified peptides (modified site lysine K2) will be not affected by UBP2 deletion. “+” stands for “increased in ubp2Δ strain” and “–” for “no change or not identified in ubp2Δ strain”.

(B) Comparison of identified K-Ɛ-GG peptides from the UbC and K-GG enrichment experiments.

(C) The overlap of K-Ɛ-GG-modified site identified from UbC and K-Ɛ-GG antibody enriched methods.

See also Figure S3.

We compared UbC and K-Ɛ-GG peptides between ubp2Δ and WT using an SILAC label-swap strategy. The UbC samples were enriched with Ni-NTA agarose and the modified peptides with a K-Ɛ-GG antibody (Figure S3A). For UbC enrichment, high-quality ubiquitinated samples were purified under denaturing conditions (Figure S3B), and three separation strategies were applied to improve coverage of UbC and their K-Ɛ-GG modified sites (Figures S3C–S3E). In the UbC and K-Ɛ-GG antibody-enriched experiments, we totally quantified 2,990 and 965 ubiquitinated proteins, with 579 and 2,091 K-Ɛ-GG peptides, respectively (Figure 2B and Table S4). We noted that there was a small overlap of modified peptides identified from these two enrichment datasets (Figure 2C), indicating the complementary effects of the two methods for the identification of the ubiquitination events.

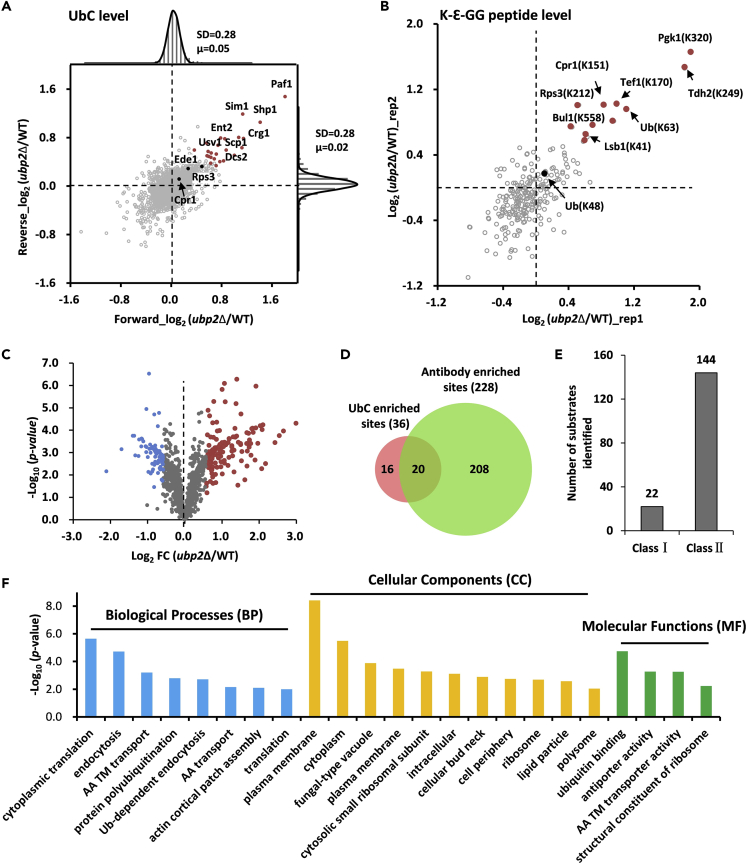

In the UbC dataset, 22 upregulated ubiquitinated proteins without change on the TCL were outlined in the ubp2Δ strain (Figure 3A and Table S3). Unexpectedly, the known Ubp2 substrates, such as 40S ribosomal protein S3 (Rps3) and EH domain-containing and endocytosis protein 1 (Ede1) (Silva et al., 2015, Sims et al., 2009), were not accumulated significantly on the UbC quantification (Figure 3A). Through DILUS strategy, the upregulated K-Ɛ-GG peptides were also considered as potentially modified sites regulated by Ubp2 (Figure 3B). In the UbC dataset, 36 upregulated K-Ɛ-GG peptides, including Rps3 (K212) and Ede1 (K1329), were significantly increased in the ubp2Δ strain, which proved that the DILUS strategy could identify the true substrates missed by the classical method. To amplify the power of DILUS, the combination with K-Ɛ-GG antibody enrichment allowed 228 upregulated peptides to be filtered out (Figure 3C) and 20 of them overlapped with the upregulated peptides obtained from the UbC dataset (Figure 3D). These results showed that each protein contained only certain upregulated K-Ɛ-GG modified sites (Table S4), suggesting that Ubp2 specifically regulated only a subset of sites within these substrates. The number of substrate candidates from class Ⅱ was much larger than that from class Ⅰ (Figure 3E). Ultimately, we combined the potential substrates derived from UbC and K-Ɛ-GG site datasets and identified 166 proteins with 244 sites that were potentially modified with K63-linked chains and regulated by Ubp2 (Table S5). Gene ontology (GO) classification analysis revealed that Ubp2 substrates potentially modified with K63-linked chains participated in a broad range of cellular processes (Figure 3F and Table S6), including endocytosis, amino acids transmembrane transport, and protein translation.

Figure 3.

Identification of Ubp2's Substrates Potentially Modified with K63-Linked Chains through DILUS Approach

(A) Global distribution of ubiquitinated proteins in label-swapped samples. The top and right shows the distribution of log2 ratios of quantified proteins in the forward (ubp2Δ/WT, n = 2,689) and reverse (ubp2Δ/WT, n = 2,777) experiments. Proteins quantified in both experiments (n = 2,475) were shown in the central scatterplot. The red dots stand for potential substrates of Ubp2 derived from UbC level quantification.

(B) Global distribution of K-Ɛ-GG peptides in label-swapped UbC samples. K-Ɛ-GG peptides with only one quantification value were not shown. The red dots stand for potential sites regulated by Ubp2 derived from UbC-enriched dataset.

(C) Volcano plot of log2 fold change (FC, ubp2Δ/WT) against -log10p-value from the t-test. The red dots were for potential sites regulated by Ubp2 derived from K-Ɛ-GG-antibody-enriched dataset.

(D) The overlap of increased modified sites from UbC-enriched and K-Ɛ-GG-antibody-enriched methods.

(E) The number of identified substrates modified with K63-linked chains as determined based on increased UbC level (class I) or K-Ɛ-GG-modified site level (class II). The false-positive targets increased on TCL were filtered out.

(F) GO analysis of the substrates regulated by Ubp2 and potentially modified with K63-linked ubiquitin chain. AA stands for amino acid and TM for transmembrane.

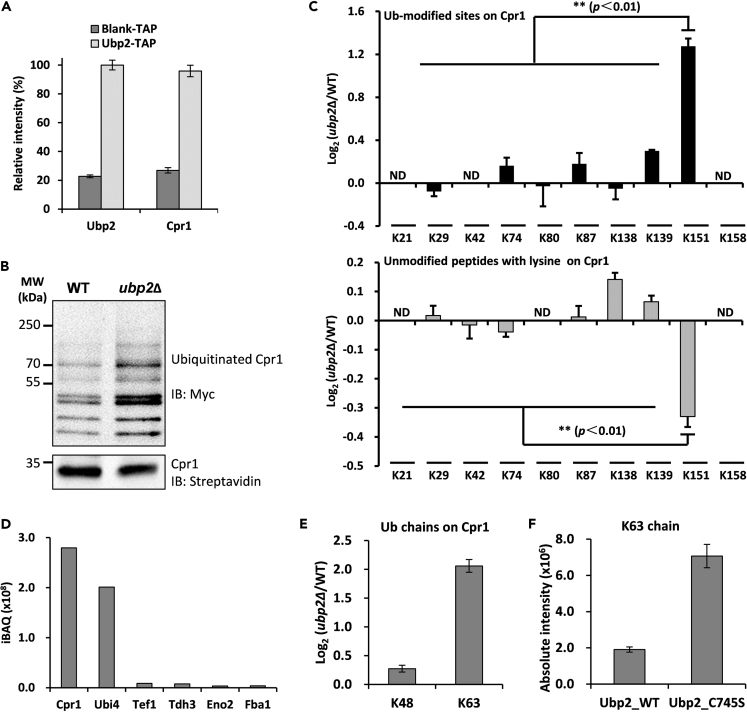

The Ubiquitination at K151 Site of Cpr1 Is Regulated by Ubp2

We noticed that most potential substrate candidates identified by DILUS were not changed on the TCL and UbC level in the ubp2Δ strain. These substrates were regulated by Ubp2 on certain but not all sites and potentially modified with K63-linked chains, which belonged to class Ⅱ (Figure 2A). To confirm the effect of DILUS strategy, we chose one novel substrate potentially regulated by Ubp2 for further analysis. The cyclophilin (Cpr1) from the UbC dataset was not altered after UBP2 deletion (Figure 3A), but the K151-modified site was increased (Figure 3B).

It is well known that cyclosporin A (CsA) inhibits T cells by blocking signal transduction (Breuder et al., 1994, Zhu et al., 2015), and Cpr1 is a target of CsA. This study as well as previous reports have shown that Cpr1 is highly ubiquitinated (Swaney et al., 2013), but the biological function of these ubiquitination events, as well as the linkage types and its regulating DUBs, are unknown. First, we expressed and purified the histidine and biotin (HB)-tagged Ubp2 and its blank control for LC-MS/MS analysis. Ubp2 was significantly enriched compared with the vector control, and the Cpr1 was also enriched significantly (Figure 4A), thus Ubp2 could interact with Cpr1. Then, we tagged Cpr1 with same histidine and biotin tags and expressed it in WT and ubp2Δ strains. We compared their ubiquitinated forms after enrichment; the western blotting suggested that ubiquitinated Cpr1, especially those of higher molecular weight, were more abundant in ubp2Δ than in WT (Figure 4B), suggesting that Cpr1 ubiquitination was affected by Ubp2. SILAC-based quantitative proteomics revealed that Cpr1 has at least seven lysine residues modified with ubiquitin (Figure 4C). However, K-Ɛ-GG peptide at Cpr1-K151 was elevated in the ubp2Δ to a greater extent than those peptides corresponding to other sites, indicating that Ubp2 specifically regulated the ubiquitination at K151 in preference to other sites (Figure 4C, up). In addition, the level of unmodified peptides at Cpr1-K151 was significantly less than that of other peptides (Figure 4C, down) as a result of a greater proportion of modified K151 sites, because of the total amount of Cpr1 in the ubp2Δ strain being unaltered.

Figure 4.

The Ubiquitination at K151 Site of Cpr1 Is Regulated by Ubp2

(A) Ubp2 interacted with Cpr1. Label-free quantification of the bait protein Ubp2 in the yeast expressing HB tag vehicle (Blank) and HB-tagged Ubp2 (HB-Ubp2) after TAP. Equal amounts of yeast cells were used, and the purifications were operated in parallel.

(B) Western blotting for Cpr1 in WT and ubp2Δ strains. WT and ubp2Δ strains expressing HB-tagged Cpr1 were subjected to TAP and immunoblotting Cpr1 and its ubiquitinated forms with anti-streptavidin and anti-Myc antibodies based on the biotin tag on Cpr1 and the myc tag on Ub, respectively.

(C) Log2 ratios of K-Ɛ-GG peptides (up) and unmodified peptides with lysine on C-terminal (down) after tryptic-cleaved Cpr1 in WT and ubp2Δ. The error bars represent mean ± SEM from two biological replicates quantifications. The asterisk (∗∗) indicated the p-value < 0.01 using t-test. ND was for no detection.

(D) The top six proteins identified in tandemly purified Cpr1 with HB tag under denatured condition.

(E) The K63 but not K48 chains on Cpr1 increased in the ubp2Δ strain. Data shown as mean ± SEM from two biological replicates quantifications.

(F) The K63 chain on Cpr1 was regulated by Ubp2 depending on USP catalytic activity. The K63-linked ubiquitin chain on Cpr1 was increased in the Ubp2 C745S mutant strain. The results were normalized with the amount of unmodified Cpr1 and shown as mean ± SEM.

After tandem affinity purification (TAP) in denatured condition, Cpr1 and ubiquitin were the most abundant, and contaminants were reduced effectively (Figure 4D). The K48-linked chain on Cpr1 was not obviously increased in the ubp2Δ strain, whereas the K63-linked chain was increased up to four times compared with WT (Figure 4E). The accumulation of K63-linked chain on Cpr1 was Ubp2 catalytic activity dependent; because this increase could not recover even we re-expressed a catalytic inactive mutant Ubp2-C745S in ubp2Δ strain (Figure 4F). Conclusively, Ubp2 participated in the regulation of ubiquitination at K151 site of Cpr1.

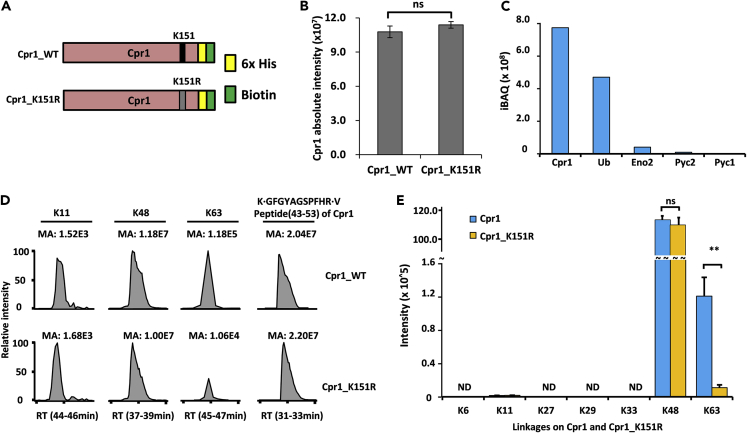

The K151 Site of Cpr1 Is Modified with K63-Linked Ubiquitin Chain

To further prove that K63-linked chains was modified at the Cpr1 K151 site, we constructed strains expressing either CPR1 or Cpr1-K151R mutant tandemly tagged with 6×histidine and biotin on their C-termini—hereafter referred to Cpr1-WT and Cpr1-K151R mutant (Figure 5A). To improve accuracy, we tandemly purified and quantified Cpr1 and Cpr1-K151R through SILAC label-swap strategy (Figure S4A). First, we confirmed the effects of the Cpr1-K151R mutation on Cpr1 abundance. We chose three peptides allowing quantification of wild-type Cpr1, namely, (Pep_1: VESLGSPSGATK), Cpr1-K151R (Pep_2: VESLGSPSGATR), and shared peptide of Cpr1 and its mutant (Pep_3: GFGYAGSPFHR; Figure S4B). The abundance of Cpr1 did not change in the Cpr1-K151R mutant (Figures 5B and S4C), suggesting that ubiquitin chain modification at Cpr1-K151 had no effect on its abundance. After TAP, the MS analysis showed that Cpr1 and ubiquitin were the most abundant, and contaminants were reduced effectively (Figure 5C). The Cpr1 contained large amounts of K48- and K63-linked chains but only a small amount of K11-linked chains (Figure 5D). Surprisingly, we found that the amount of K63-linked chains in WT was 10-fold higher than in cpr1-K151R mutant (Figures 5E and S4D). However, no significant difference was detected in the abundance of K48-linked chains (Figures 5E and S4E). These results strongly indicated that Cpr1 was modified with K48- and K63-linked ubiquitin chains and that Ubp2 recognized and cleaved K63-linked chains at K151 but not K48-linked chains at other sites.

Figure 5.

The K151 Site of Cpr1 Is Modified with K63-Linked Chain

(A) Schematic for the construction of HB tagged Cpr1 and its K151R mutant.

(B) The Cpr1 amount was not affected in the K151R mutant. Data shown as mean ± SEM from two biological replicates quantifications.

(C) The identified proteins from tandemly purified Cpr1 with HB tag under denatured conditions.

(D) HPLC chromatographic peaks of the identified Ub chains on Cpr1 and Cpr1-K151R. The peak area (AA) corresponds to the relative ion intensity of the target peptide. Three Ub-linkages (K11, K48, and K63) were detected. One of tryptic peptide (GFGYAGSPFHR) shared by Cpr1 and Cpr1-K151R was used as quantitation control.

(E) Swapped SILAC-based quantitative proteomics of tandemly purified ubiquitin chains for WT and Cpr1-K151R mutant. Light- and heavy-isotope-labeled amino acids were incorporated into Cpr1 and Cpr1-K151R in cell culture. Yeast cells were lysed under denatured conditions and then tandemly purified with HB tags. The error bars were represented mean ± SEM from two biological replicates quantifications.

See also Figure S4.

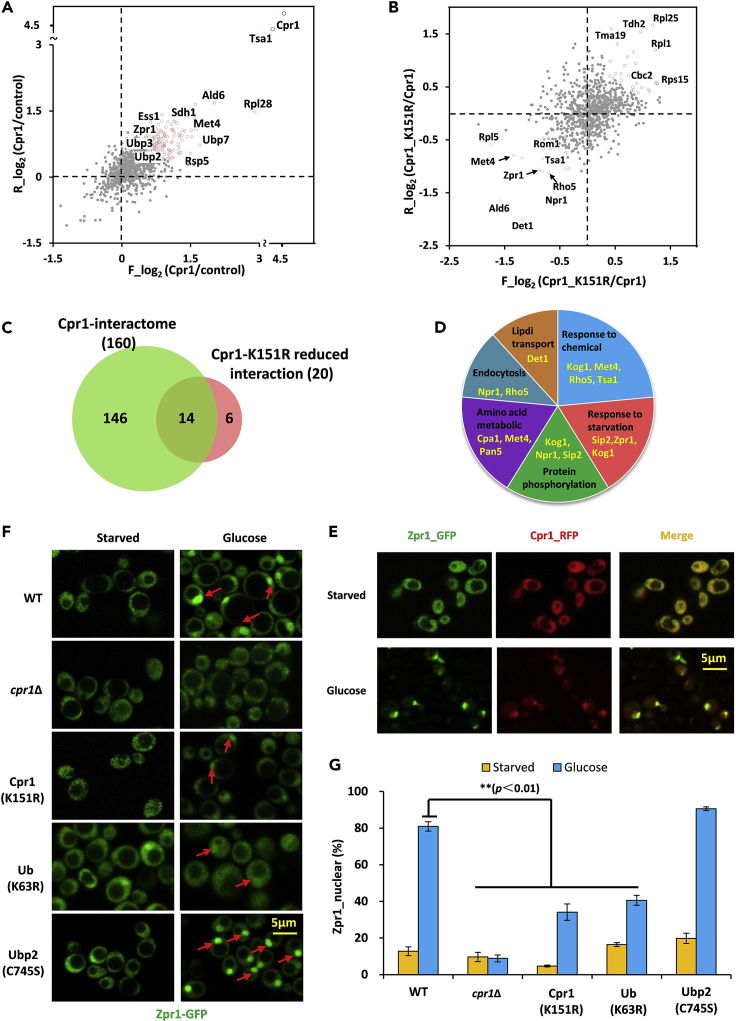

The K63-Linked Chain at K151 Site of Cpr1 Mediates the Nuclear Translocation of Zpr1

To investigate the biological function of the K63-linked chains at the Cpr1 K151 site, we employed an SILAC-based TAP strategy to profile the Cpr1 interactome (Figures 6A and S5A) and the putative interacting proteins of K63-linked chains at the Cpr1 K151 site (Figures 6B and S5B). After TAP in native conditions, the abundance of Cpr1 and Cpr1-K151R in SDS–PAGE resolved samples was measured through silver staining (Figure S5C). Figure 6A showed the upregulated proteins that interacted with Cpr1 (Table S7), including positive controls such as Ess1 (Ansari et al., 2002). We noticed that Rsp5, an E3 ligase of NEDD4 family that catalyzes the synthesis of K63-linked ubiquitin chains, was also enriched. Additionally, we identified those interacting proteins that were decreased when Cpr1 was mutant at the K151 site (downregulated proteins in the third quadrant in Figure 6B and Table S7). Interestingly, a majority of these interacting proteins were overlapped with the Cpr1 interactome (Figure 6C). Gene ontology classification of these interacting proteins revealed that the K151R substitution perturbs the Cpr1 interactome in a profound manner during the starvation, amino acid metabolism, and endocytosis processes. These results indicated that K63-linked chains at Cpr1-K151 executed some cellular functions (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

The K63-Linked Chain at K151 Site of Cpr1 Promotes Nuclear Translocation of Zpr1

(A) Global distribution of Cpr1-interacting proteins (shown in red) in SILAC label-swapped samples.

(B) Global distribution of all Cpr1-and its K151R mutant-interacting proteins. The blue points represented interacting proteins specific for K63-linked chains at K151 of Cpr1.

(C) Overlap between Cpr1-interacting proteins (left) and proteins that interacted with K63-linked chains at K151 of Cpr1 (right).

(D) Gene ontology classification for proteins that interacted with K63-linked chains at K151 of Cpr1.

(E) Both Zpr1 (green) and Cpr1 (red) moved from cytoplasm to the nucleus following glucose treatment. Areas of co-localization were shown in yellow (merged images, scale bar = 5 μm).

(F) The nuclear transport of Zpr1 following glucose treatment was reduced in Cpr1-K151R mutants and blocked in the CPR1-deletion strain. WT, cpr1Δ, Cpr1-K151R, ubiquitin-K63R, and Ubp2 C745S mutants expressing Zpr1-GFP were grown to log phase in YEPD medium, starved in glucose-free synthetic complete medium for 12 h, and then treated with glucose (scale bar = 5 μm).

(G) Percentage of Zpr1 that was transported to the nucleus prior to and after glucose treatment. Data were shown as mean ± SEM obtained from three independent experiments (~100 yeast cells per experiment).

See also Figures S5–S7 and Table S7.

Among the K151-dependent Cpr1-interacting proteins, Zpr1 (zinc finger protein) decreased its association with the Cpr1-K151R mutation. Previous studies have shown that Zpr1 interacts with ubiquitin and undergoes nuclear translocation following mitogen treatment (Ansari et al., 2002). Structure analysis showed that Zpr1 owned two zinc finger domains, which might interact with the K63-linked chain. We incubated recombinant Zpr1 with equal amounts of K48- and K63-linked ubiquitin chains (N = 2–7) and then washed with PBS thoroughly for far-western blotting analysis (Xiao et al., 2020). We found that its interaction with K63-linked chains was stronger than K48-linked chains (Figure S6A). Furthermore, Zpr1 displayed higher affinity for longer over shorter K63-linked chains (Figure S6B).

Previous studies show that Zpr1 is in the nucleus of growing cells and relocates to the cytoplasm during starved status via a Cpr1-mediated process (Ansari et al., 2002). In this study, yeast cells expressing Zpr1-GFP and Cpr1-mcherry were grown to log phase in a rich YEPD medium and starved in a glucose-free synthetic complete medium overnight and then retreated with glucose. Zpr1 was found in the cytoplasm after 12 h of nutrient withdrawal (upper left panel of Figures 6E and 6F); it was almost entirely translocated to the nucleus following the addition of glucose (left lower panel of Figure 6E and upper right panel of Figure 6F). Cpr1 was co-localized with Zpr1 in the cytoplasm under starvation and then translocated to the nucleus in the presence of glucose (Figures 6E and S7). In contrast, glucose treatment did not activate Zpr1 translocation in the starved cpr1Δ strain, suggesting the importance of Cpr1 in this process. Interestingly, the Cpr1-K151R substitution of Cpr1 reduced the efficiency of translocation to less than half, and similar effects were also observed in the ubiquitin K63R mutant. On the contrary, Ubp2-C745S mutant accelerated the Zpr1 nuclear translocation in some degree (Figures 6F and 6G). These results collectively suggested that the K63-linked chain at Cpr1-K151 and its regulation by Ubp2 were critical for Zpr1 translocation.

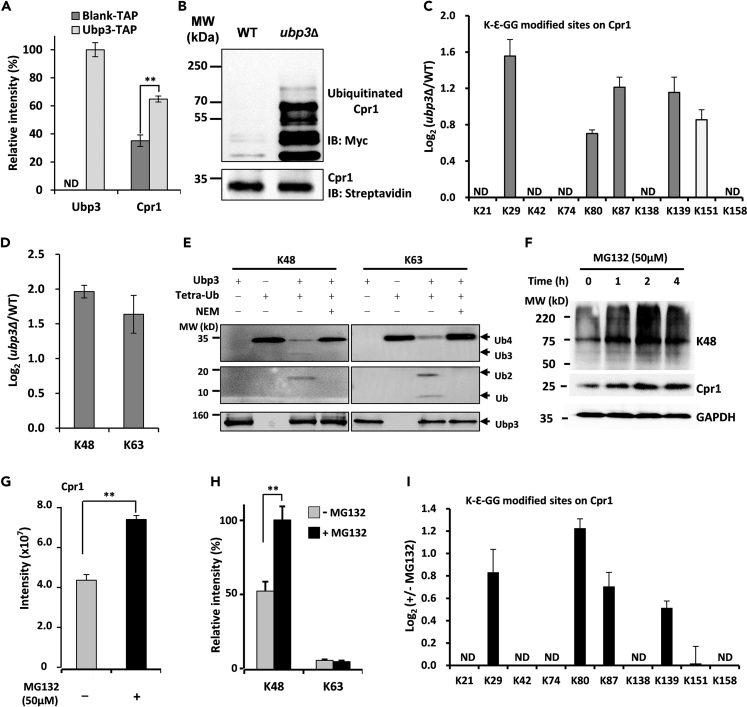

Ubp3-Mediated Cleavage of K48-Linked Chains at Non-K151 Sites of Cpr1 Triggers Proteasomal Degradation

As not all of the ubiquitination sites were regulated by Ubp2, we speculated that there exist other DUBs regulating the ubiquitination especially for the K48-linked chains on the Cpr1. To identify DUBs involved in the regulation of non-K63-linked chains on Cpr1, we reanalyzed the Cpr1 interactome dataset and found that besides Ubp2, Ubp3 and Ubp7 were also found to be Cpr1-interacting proteins (Figure 6A). The Ubp3-Cpr1 interaction was in agreement with a previous report (Ossareh-Nazari et al., 2010). To further validate the interaction, we constructed HB-tagged Ubp3 and proved that Cpr1 was found to interact with Ubp3 (Figure 7A). Because Ubp7 did not significantly affect the ubiquitination of Cpr1 (data not shown), Ubp7 was not included for further analysis in this study.

Figure 7.

K48-Linked Chains at Non-K151 Sites of Cpr1 Regulated by Ubp3 Trigger Proteasomal Degradation

(A) Ubp3 interacted with Cpr1. Label-free quantification of the bait protein Ubp3 in the yeasts expressing HB tag vehicle (Blank) and HB-tagged Ubp3 (HB-Ubp3) after TAP. Equal amounts of the yeast cells were used and the purifications were operated in parallel.

(B) The ubiquitinated level of Cpr1 in ubp3Δ increased. WT and ubp3Δ strains expressing HB-tagged Cpr1 were subjected to tandem affinity purification and immunoblotting Cpr1 and its ubiquitinated forms with anti-streptavidin and anti-myc antibodies based on the biotin tag on Cpr1 and the myc tag on Ub, respectively.

(C) Log2 ratios of K-Ɛ-GG peptides on tryptic-cleaved Cpr1 in WT and ubp3Δ. The error bars represented mean ± SEM from two biological replicates quantifications. ND was for no detection.

(D) Both the K48 and K63 chains on Cpr1 were increased in the ubp3Δ strain.

(E) Ubp3 cleaves K48- and K63-linked chains in vitro. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 20 min before immunoblotting with monoclonal anti-ubiquitin antibody. Image was visualized by ECL.

(F) Accumulation of Cpr1 and K48-linked chains was observed after MG132 treatment. Strain expressing HB-Cpr1 was treated and harvested for immunoblotting with anti-K48 and anti-streptavidin antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

(G) The abundance of Cpr1 was relatively quantified by MS. The sample was harvested after two hours with MG132 treatment.

(H) Inhibition of the proteasome system increased the level of K48 but not K63 chain on Cpr1. The strain expressing HB-Cpr1 was inhibited with 50 μM MG132 and then quantified with LC-MS/MS after tandem affinity purification of Cpr1.

(I) Log2 ratios of K-Ɛ-GG peptides on tryptic Cpr1 tandemly purified from untreated and MG132-treated samples. Two technical replicates were performed and data shown as mean ± SEM.

We further investigated the role of Ubp3 in the deubiquitinating regulation of Cpr1. The western blotting results suggested that ubiquitinated Cpr1, especially those of higher molecular weight, were much more abundant in ubp3Δ than in WT (Figure 7B). This indicated that Cpr1 ubiquitination was significantly affected by Ubp3. SILAC-based quantitative proteomics showed that the lack of Ubp3 increased the K-Ɛ-GG peptides of Cpr1 at all sites including the K151 site (Figure 7C). The K48- and K63-linked chains on Cpr1 were both significantly increased (Figure 7D). Figure 1B showed that Ubp3 was chain-unspecific and the second most important DUB regulating K63-linked chains in yeast. Furthermore, we characterized Ubp3 activity by performing in vitro deubiquitination assays. Ubp3 cleaved both K48- and K63-linked chains with high activity (Figure 7E). These results indicated that Ubp3 also regulated K63-linked chains at K151 and K48-linked chains at non-K151 sites of Cpr1.

We further investigated the biological effects of K48-linked chains on Cpr1. Following the treatment with a proteasome inhibitor MG132, the abundance of both K48-linked chains and Cpr1 increased with time of incubation (Figure 7F). LC–MS/MS results also showed that the amount of Cpr1 in TCL increased about two-fold after MG132 treatment (Figure 7G), consistent with western blot results, suggesting that the degradation of Cpr1 was mediated by the proteasome. The abundance of K48-linked chains on Cpr1 increased more than two-fold, whereas the abundance of K63-linked chains remained stable after MG132 treatment (Figure 7H), suggesting that K48-linked chains regulate the Cpr1 level through proteasomal degradation. The abundance of non-K151 K-Ɛ-GG peptides was significantly increased after MG132 treatment but that of K151 was not impacted by MG132, further implying the different functions of these ubiquitin chain types (Figure 7I).

Discussion

There are eight types of ubiquitin chains, whereas we focus on seven lysine-linked ubiquitin chains and exclude linear chain in this study. This is because the N-terminal tags on ubiquitin are introduced in WT (JMP024) strain.

Previous in vitro deubiquitinating assays provide pivotal and efficient evidences for the activity and specificity of DUBs to pure ubiquitin chains (Mevissen et al., 2013, Ritorto et al., 2014). Four mechanisms underlying the linkage specificity of the OTU class of DUBs have been concluded (Mevissen et al., 2013). However, the linkage specificity of DUBs in vivo is more complex and poorly understood. In cells, DUBs are tightly regulated in space and time and can act as negative or positive regulators of the ubiquitin system including E2 and E3, which may be direct or indirect regulation of the ubiquitin chains. For example, the human OTUB1 is specific for cleaving K48-linked ubiquitin chains and has no activity for K63-linked chains in an in vitro assay. However, both K48- and K63-linked chains were accumulated in OTUB1 deletion cells. Further analysis reveals that OTUB1 binds to the E2 UBC13 in vivo, which inhibits the extension of the K63-linked chain (Juang et al., 2012).

To determine the linkage specificity of DUBs in vivo, we assumed that a specific DUB deletion would result in the accumulation of its preferred linkages. Although this accumulation may be a result of direct or indirect effects because of the loss of certain DUB, the results provide us some valuable hints reflecting the specificity of DUBs to ubiquitin chains. For the USP family, most of them were not linkage specific, whereas the specificity of Ubp2 toward K63-linked chains was verified through in vitro and in vivo assays. Ubp14 was preferred to all six free ubiquitin chains except K63-linked forms in vivo. Here, we also confirmed that Otu1 could specifically regulate more K11-linked chains modified on substrates than Otu2 in vivo, which was consistent with those from in vitro assay studies (Mevissen et al., 2013). Conclusively, we noted that in vivo assays may not always be straightforward to interpret because of competing effects of other DUBs in the cell. Therefore, in vivo and in vitro assays are best used in combination for studying the specificity of DUBs.

It is technically challenging to identify the types of ubiquitin linkage associated with a defined residue in a substrate. Generally, the strategy for identifying UPS substrates is based on the total protein quantification (Raman et al., 2015). In this study, we developed the DILUS strategy of combing DUB linkage specificity and quantification of K-Ɛ-GG peptides, allowing us to identify site-specific modifications of certain ubiquitin linkage on substrates regulated by Ubp2 (Figure 2A). For DILUS approach, however, it required that Ubp2 or any other chain-specific DUB of choice to obviously increase the specific chain but not the mono-ubiquitination (Kee et al., 2006). If not, it was hard to speculate the chain types bound on the substrates through the MS quantitative analysis. The further combination of DILUS with the K-Ɛ-GG antibody enrichment strategy enabled more site-specific identification with certain linkages (Kim et al., 2011, Tong et al., 2014, Udeshi et al., 2013). With more modification sites being systematically identified and quantified in Ubp2 and other DUBs, robust evidence and a stronger conclusion about the determining elements for the substrate specificity of DUBs can be obtained in the future.

Different sites of Cpr1 are modified by different ubiquitin chain types. However, it is unclear how DUBs specifically distinguish and regulate these ubiquitin chains and what roles these modifications played before. What determines the regulation and how the DUBs cooperate with each other for substrate ubiquitination will require more research. The K63-linked chains at K151 of Cpr1mediated interaction with Zpr1. The zinc finger domain of Zpr1 may interact with a K63-linked chain with higher affinity than a K48-linked chain. Additionally, the affinity capacity of the Zpr1 with K63-linked chain was increased with the length of the chain (Figure S6). In future studies, more evidence should be added to support this potential new ubiquitin-binding domain for K63-linked chains. The absence of K63-linked chains in Cpr1-K151R mutant significantly hindered the interaction between Cpr1 and Zpr1, thereby impacting the translocation of Zpr1 from cytoplasm to the nucleus in starved cells following glucose treatment. We also found that the K151R mutation reduced but did not block Zpr1 nuclear translocation because the process was rescued by the extension of glucose stimulation (data not shown). The results suggest that other mechanisms might exist to regulate the translocation of Zpr1 from cytoplasm to nucleus, including the compensatory mechanism of K63-linked chain on other sites of Cpr1. The molecular mechanisms underlying this process require further study.

In conclusion, the results of DUBs for ubiquitin chains bearing different linkages reflected the in vivo specificity. Using the linkage and site specificities, we developed a novel strategy, DILUS, to determine the sites on substrates favorable to decoding the ubiquitin code. Using this strategy, we identified substrates of Ubp2 modified by K63-linked chains and provided the detailed mechanism of how DUBs edit and regulate ubiquitination precisely. The balance of different chains on certain sites of Cpr1 regulated by specific DUBs is tightly coupled to the regulation of protein levels and signaling functions. These findings not only provide new insights into the regulatory mechanisms underlying deubiquitination but also reveal complicated ubiquitination networks, transduction pathways, and biological functions.

Limitations of the Study

Although we aimed to reflect the ubiquitin chain specificity of DUBs in vivo, we could not exclude the side effects of DUBs deletion. For example, certain DUB might affect the ubiquitin transcription and the stability of E2 or E3, which made it more complex for specificity research in vivo. We thus recommended to verifying their linkage specificity additionally with in vitro assays. Second, although Ubp2 preferred to cleave the K63 linkage, we still could not completely exclude the substrate candidates modified with mono-ubiquitination or other chains potentially affected by Ubp2 when using DILUS strategy. For this limitation, we could use the tools of K63-UIM (ubiquitin interacting motif) (Sims and Cohen, 2009) to reduce the interference. K63-UIM could specifically interact with K63 ubiquitin chains with high affinity than other chains and mono ubiquitin, thus combined K63-UIM enrichment with DILUS strategy would be a perfect method to screen the specific substrates of Ubp2. Finally, despite we had screened a series of potential candidate substrates of Ubp2 through DILUS strategy, additional molecular and biochemical validations would be recommended to verify the target substrates.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Wei Xiao, JunminPeng, Felix Cheung, Anthony Nguyen, Miguel Prado, and Eric Dammer for critical review of the manuscript. We thank Drs. Joseph Heitman, Lilin Du, Donald Kirkpatrick, and Yanchang Wang for gracious gifts of their reagents, strains, and ubiquitin linkage-specific antibodies. We are indebted to Drs. Jingwei Wang, Tianying Yu, Limei Zhou, and Chen Deng for support in the early stage of this project. This study was supported by the Chinese National Basic Research Programs (2017YFA0505100, 2017YFA0505002, 2017YFC0906600, & 2017YFC0906700), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31700723, 31670834, 31870824, 31901037, & 91839302), the Innovation Foundation of Medicine (16CXZ027, AWS17J008, & BWS17J032), National Megaprojects for Key Infectious Diseases (2018ZX10302302), Guangzhou Science and Technology Innovation & Development Project (201802020016), the Unilevel 21st Century Toxicity Program (MA-2018-02170N), the Foundation of State Key Lab of Proteomics (SKLP-K201704), and the National Institutes of Health of United States grant (R37GM43601) to D.F.

Author Contributions

P.X. and Y.L. designed experiments. Y.L. and Q.L. performed most of the experiments with the help of Y.G. and Z.X.. Y.L. and Q.L. collected and analyzed all the data with the help of Y.W.. C.X., Q.L., and L.C. constructed all the DUB's knockout strains. Y.L. and P.X. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. J.W., Z.D., F.H., and D.F. offered advice and discussion for the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: April 24, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.100984.

Data and Code Availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository (Ma et al., 2019). The accession numbers for the mass spectrometry proteomics data reported in this paper are the ProteomeXchange dataset identifier: PXD017357 and the iProX (https://www.iprox.org/) dataset identifier: IPX0001986000.

Supplemental Information

References

- Abdul Rehman S.A., Kristariyanto Y.A., Choi S.Y., Nkosi P.J., Weidlich S., Labib K., Hofmann K., Kulathu Y. MINDY-1 is a member of an evolutionarily conserved and structurally distinct new family of deubiquitinating enzymes. Mol. Cell. 2016;63:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amerik A.Y., Hochstrasser M. Mechanism and function of deubiquitinating enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1695:189–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari H., Greco G., Luban J. Cyclophilin A peptidyl-prolylisomerase activity promotes ZPR1 nuclear export. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:6993–7003. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.6993-7003.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuder T., Hemenway C.S., Movva N.R., Cardenas M.E., Heitman J. Calcineurin is essential in cyclosporin A- and FK506-sensitive yeast strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1994;91:5372–5376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Liu X., Xia T., Tekcham D.S., Wang W., Chen H., Li T., Lu C., Ning Z., Liu X. A multidimensional characterization of E3 ubiquitin ligase and substrate interaction network. iScience. 2019;16:177–191. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clague M.J., Barsukov I., Coulson J.M., Liu H., Rigden D.J., Urbe S. Deubiquitylases from genes to organism. Physiol. Rev. 2013;93:1289–1315. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clague M.J., Urbe S., Komander D. Breaking the chains: deubiquitylating enzyme specificity begets function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20:338–352. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faesen A.C., Luna-Vargas M.P., Geurink P.P., Clerici M., Merkx R., van Dijk W.J., Hameed D.S., El Oualid F., Ovaa H., Sixma T.K. The differential modulation of USP activity by internal regulatory domains, interactors and eight ubiquitin chain types. Chem. Biol. 2011;18:1550–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley D. Recognition and processing of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu. Rev.Biochem. 2009;78:477–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley D., Ulrich H.D., Sommer T., Kaiser P. The ubiquitin-proteasome system of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;192:319–360. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.140467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Li Y., Zhang C., Zhao M., Deng C., Lan Q., Liu Z., Su N., Wang J., Xu F. Enhanced purification of ubiquitinated proteins by engineered tandem hybrid ubiquitin-binding domains (ThUBDs) Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2016;15:1381–1396. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O115.051839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gersch M., Gladkova C., Schubert A.F., Michel M.A., Maslen S., Komander D. Mechanism and regulation of the Lys6-selective deubiquitinase USP30. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:920–930. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A., Ciechanover A., Varshavsky A. Basic medical research award.The ubiquitin system. Nat. Med. 2000;6:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/80384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeller D., Dikic I. Targeting the ubiquitin system in cancer therapy. Nature. 2009;458:438–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Jeon M.S., Liao L., Yang C., Elly C., Yates J.R., 3rd, Liu Y.C. K33-linked polyubiquitination of T cell receptor-zeta regulates proteolysis-independent T cell signaling. Immunity. 2010;33:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husnjak K., Dikic I. Ubiquitin-binding proteins: decoders of ubiquitin-mediated cellular functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:291–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051810-094654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda F., Dikic I. Atypical ubiquitin chains: new molecular signals. 'Protein Modifications: beyond the Usual Suspects' review series. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:536–542. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang Y.C., Landry M.C., Sanches M., Vittal V., Leung C.C., Ceccarelli D.F., Mateo A.R., Pruneda J.N., Mao D.Y., Szilard R.K. OTUB1 co-opts Lys48-linked ubiquitin recognition to suppress E2 enzyme function. Mol. Cell. 2012;45:384–397. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee Y., Lyon N., Huibregtse J.M. The Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase is coupled to and antagonized by the Ubp2 deubiquitinating enzyme. EMBO J. 2005;24:2414–2424. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee Y., Munoz W., Lyon N., Huibregtse J.M. The deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp2 modulates Rsp5-dependent Lys63-linked polyubiquitin conjugates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:36724–36731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W., Bennett E.J., Huttlin E.L., Guo A., Li J., Possemato A., Sowa M.E., Rad R., Rush J., Comb M.J. Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Mol. Cell. 2011;44:325–340. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komander D., Rape M. The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:203–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristariyanto Y.A., Abdul Rehman S.A., Weidlich S., Knebel A., Kulathu Y. A single MIU motif of MINDY-1 recognizes K48-linked polyubiquitin chains. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:392–402. doi: 10.15252/embr.201643205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulathu Y., Komander D. Atypical ubiquitylation - the unexplored world of polyubiquitin beyond Lys48 and Lys63 linkages. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:508–523. doi: 10.1038/nrm3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Dammer E.B., Gao Y., Lan Q., Villamil M.A., Duong D.M., Zhang C., Ping L., Lauinger L., Flick K. Proteomics links ubiquitin chain topology change to transcription factor Activation. Mol. Cell. 2019;76:126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Chen T., Wu S., Yang C., Bai M., Shu K., Li K., Zhang G., Jin Z., He F. iProX: an integrated proteome resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D1211–D1217. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mevissen T.E.T., Hospenthal M.K., Geurink P.P., Elliott P.R., Akutsu M., Arnaudo N., Ekkebus R., Kulathu Y., Wauer T., El Oualid F. OTU deubiquitinases reveal mechanisms of linkage specificity and enable ubiquitin chain restriction analysis. Cell. 2013;154:169–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mevissen T.E.T., Komander D. Mechanisms of deubiquitinase specificity and regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017;86:159–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min M., Mevissen T.E., De Luca M., Komander D., Lindon C. Efficient APC/C substrate degradation in cells undergoing mitotic exit depends on K11 ubiquitin linkages. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2015;26:4325–4332. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-02-0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman S.M.B., Luna-Vargas M.P.A., Velds A., Brummelkamp T.R., Dirac A.M.G., Sixma T.K., Bernards R. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell. 2005;123:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossareh-Nazari B., Bonizec M., Cohen M., Dokudovskaya S., Delalande F., Schaeffer C., Van Dorsselaer A., Dargemont C. Cdc48 and Ufd3, new partners of the ubiquitin protease Ubp3, are required for ribophagy. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:548–554. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J., Schwartz D., Elias J.E., Thoreen C.C., Cheng D., Marsischky G., Roelofs J., Finley D., Gygi S.P. A proteomics approach to understanding protein ubiquitination. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:921–926. doi: 10.1038/nbt849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman M., Sergeev M., Garnaas M., Lydeard J.R., Huttlin E.L., Goessling W., Shah J.V., Harper J.W. Systematic proteomics of the VCP-UBXD adaptor network identifies a role for UBXN10 in regulating ciliogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:1356–1369. doi: 10.1038/ncb3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Turcu F.E., Ventii K.H., Wilkinson K.D. Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:363–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082307.091526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritorto M.S., Ewan R., Perez-Oliva A.B., Knebel A., Buhrlage S.J., Wightman M., Kelly S.M., Wood N.T., Virdee S., Gray N.S. Screening of DUB activity and specificity by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4763. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva G.M., Finley D., Vogel C. K63 polyubiquitination is a new modulator of the oxidative stress response. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:116–123. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims J.J., Cohen R.E. Linkage-specific avidity defines the lysine 63-linked polyubiquitin-binding preference of rap80. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:775–783. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims J.J., Haririnia A., Dickinson B.C., Fushman D., Cohen R.E. Avid interactions underlie the Lys63-linked polyubiquitin binding specificities observed for UBA domains. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:883–889. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence J., Sadis S., Haas A.L., Finley D. A ubiquitin mutant with specific defects in DNA repair and multiubiquitination. Mol. Cell Biol. 1995;15:1265–1273. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolz A., Dikic I. Heterotypic ubiquitin chains: seeing is believing. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaney D.L., Beltrao P., Starita L., Guo A., Rush J., Fields S., Krogan N.J., Villen J. Global analysis of phosphorylation and ubiquitylation cross-talk in protein degradation. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z., Kim M.S., Pandey A., Espenshade P.J. Identification of candidate substrates for the Golgi Tul1 E3 ligase using quantitative diGly proteomics in yeast. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:2871–2882. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.040774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udeshi N.D., Svinkina T., Mertins P., Kuhn E., Mani D.R., Qiao J.W., Carr S.A. Refined preparation and use of anti-diglycine remnant (K-epsilon-GG) antibody enables routine quantification of 10,000s of ubiquitination sites in single proteomics experiments. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:825–831. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O112.027094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Liu X., Cui Y., Tang Y., Chen W., Li S., Yu H., Pan Y., Wang C. The E3 ubiquitin ligase AMFR and INSIG1 bridge the activation of TBK1 kinase by modifying the adaptor STING. Immunity. 2014;41:919–933. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W., Liu Z., Luo W., Gao Y., Chang L., Li Y., Xu P. Specific and unbiased detection of polyubiquitination via a sensitive non-antibody approach. Anal. Chem. 2020;92:1074–1080. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P., Duong D.M., Seyfried N.T., Cheng D., Xie Y., Robert J., Rush J., Hochstrasser M., Finley D., Peng J. Quantitative proteomics reveals the function of unconventional ubiquitin chains in proteasomal degradation. Cell. 2009;137:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W.C., Lee Y.R., Lin S.Y., Chang L.Y., Tan Y.P., Hung C.C., Kuo J.C., Liu C.H., Lin M.Y., Xu M. K33-Linked polyubiquitination of coronin 7 by cul3-KLHL20 ubiquitin E3 ligase regulates protein trafficking. Mol. Cell. 2014;54:586–600. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D., Wang Z., Zhao J.J., Calimeri T., Meng J., Hideshima T., Fulciniti M., Kang Y., Ficarro S.B., Tai Y.T. The Cyclophilin A-CD147 complex promotes the proliferation and homing of multiple myeloma cells. Nat. Med. 2015;21:572–580. doi: 10.1038/nm.3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang M., Guan S., Wang H., Burlingame A.L., Wells J.A. Substrates of IAP ubiquitin ligases identified with a designed orthogonal E3 ligase, the NEDDylator. Mol. Cell. 2013;49:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository (Ma et al., 2019). The accession numbers for the mass spectrometry proteomics data reported in this paper are the ProteomeXchange dataset identifier: PXD017357 and the iProX (https://www.iprox.org/) dataset identifier: IPX0001986000.