Abstract

Background

New York State hospitals are required to implement a respiratory protection program (RPP) consistent with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration respirator standard. Guidance provided during the 2009 novel H1N1 pandemic expanded on earlier recommendations, emphasizing the need to keep staff in all health care settings healthy to maintain services.

Methods

New York State hospitals with emergency departments having more than 1,000 visits annually were invited to participate; 23 hospitals participated. Health care workers, unit managers, and hospital managers were interviewed regarding knowledge, beliefs, and practices of respiratory protection. Interviewees were observed donning and doffing an N-95 respirator as they normally would during patient care. Written RPPs for each hospital were evaluated.

Results

The majority of the hospitals surveyed had implemented an RPP, although unawareness of the policies and practices, as well as inadequacies in education and training exist among health care workers.

Conclusion

Health care workers and other hospital employees may be unnecessarily exposed to airborne infectious diseases. Having an RPP ensures safe and effective use of N-95 respirators and will help prevent avoidable exposure to disease during a pandemic, protecting the health care workforce and patients alike.

Key Words: H1N1, Transmission-based precautions, Hospital personnel, Hospitals, Emergency departments, N-95

Influenza, commonly referred to as the flu, is an infectious respiratory illness that is transmitted from person to person through close contact and direct touch, indirect touch, and respiratory droplets. Four influenza pandemics have occurred since 1918. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that, during the 2009 pandemic, 43 million to 89 million people contracted the novel H1N1 strain of influenza, and between 8,870 and 18,300 died as a result.1

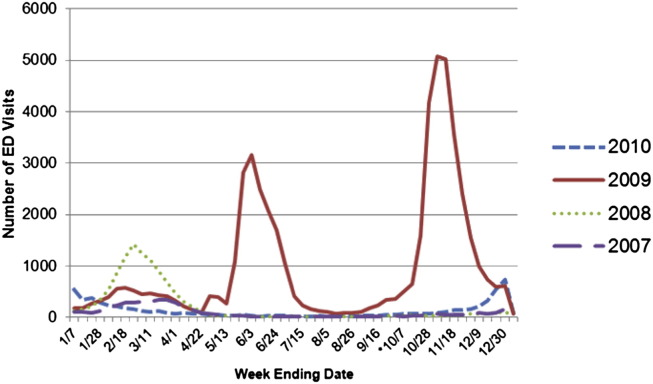

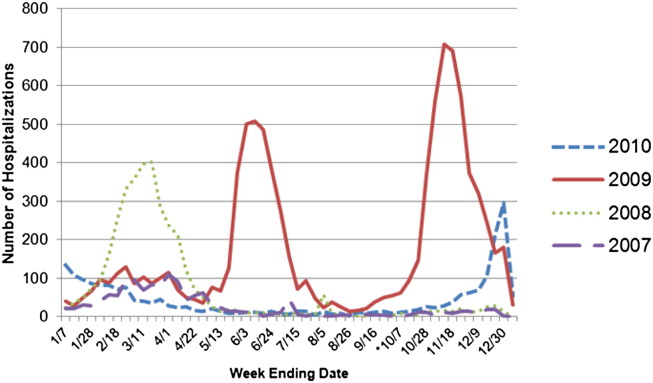

During the spring and winter of 2009, New York State (NYS) hospitals experienced a surge in emergency department (ED) visits, as well as inpatient hospital admissions, because of an increase in cases presenting with influenza-like illness.2 Figures 1 and 2 indicate the impact of influenza virus (including 2009 H1N1) on NYS hospitals from January 2007 through December 2010. Figures were generated using NYS hospital discharge data.3

Fig 1.

Number of emergency department visits by week based on New York State hospital discharge data from 2007 through 2010. *If H1N1 was suspected but not confirmed, “487.XX” was designated as the appropriate ICD-9 code. As of October 1, 2009 (week ending 10/7), cases of confirmed H1N1 were assigned the ICD-9 of “488.1.”

Fig 2.

Number of inpatient admissions by week based on New York State hospital discharge data from 2007 through 2010. *If H1N1 was suspected but not confirmed, “487.XX” was designated as the appropriate ICD-9 code. As of October 1, 2009 (week ending 10/7), cases of confirmed H1N1 were assigned the ICD-9 of “488.1.”

The increases seen in 2009 placed an additional burden on the health care system, emphasizing the need to keep staff in all health care settings healthy to maintain services. The CDC released interim guidance on infection control measures to prevent transmission of the 2009 H1N1 virus in health care settings.4 The guidance expanded on earlier recommendations and emphasized a comprehensive approach that includes all persons whose occupational activities involve contact with patients or potentially contaminated material in a health care setting.4 The guidance indicated that the 2009 influenza virus was transmitted from person to person through close contact in ways similar to other influenza viruses, although studies indicated that H1N1 may be spread via smaller airborne particles.4 As a result, appropriate airborne infectious disease precautions were recommended.

A respirator is a personal protective device that is worn on the face, covers the nose and mouth, and used to reduce the user's risk of inhaling airborne contaminants. Air-purifying respirators (APR) use filters to remove airborne particles and sorbent media to remove gases and vapors as the user inhales. There are 3 main categories of APRs: particulate-filtering facepiece respirators, elastomeric respirators, and powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs).

The N-95 respirator is a particulate filtering facepiece and is one of the most commonly used respirators in health care settings. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health's (NIOSH) respirator approval criteria defines the term N-95 as a filter class that removes at least 95% of the “most-penetrating” sized airborne particle during a NIOSH standardized test procedure.5

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires employers who use respirators to develop and administer a written respiratory protection program (RPP). Elements of the RPP include policies and procedures for fit testing, employee training, employee medical clearance, appropriate selection of respirators for the assigned task, proper maintenance of respirators, record keeping, program evaluation, and designation of an administrator to oversee the program.

The CDC guidelines recommend that facilities implement a “hierarchy of controls” to prevent exposure to influenza. The hierarchy prioritizes protective measures based on their likelihood of reducing the risk of exposure. It also serves to reduce reliance on respiratory protection in the event of a shortage. Top priorities in this hierarchy are those measures that can eliminate the source of potential exposure. The use of PPE, including respirators, is for protection from exposures that cannot otherwise be eliminated or controlled.

Respirators are particularly useful in situations where the other elements of the hierarchy of controls are inadequate or infeasible. Examples include exposure to undiagnosed cases during triage in a pandemic, within ambulances when patients are symptomatic, and when performing medically necessary aerosol-generating procedures on infectious cases.

Methods

Sampling strategy

The population surveyed for this project was health care workers (HCW), unit managers (UM), and hospital managers (HM) in NYS hospital EDs that see more than 1,000 patients annually (based on 2006 NYS hospital discharge data).3 Approval for this research was granted by the NYS Department of Health Institutional Review Board.

Acute care hospital recruitment

In NYS, there are 223 hospitals with ED facilities. For this project, hospitals with over 1,000 ED visits for 2006 were considered. There are 213 hospitals that had over 1,000 ED visits in 2006.

The 213 hospitals that were identified as being eligible to participate were mailed initial recruitment materials with information and background on the project. Follow-up calls were then made to the hospitals. Twenty-three hospitals agreed to participate. Site visits were conducted, and potential participants were identified by the infection control practitioners at each facility through convenience sampling.

Data collection

Standardized questionnaires developed by NIOSH were used in the interviews. Participants were all asked a series of questions concerning their general demographic information and knowledge of their facility's risk assessment, medical evaluation protocols, fit testing procedures, RPP training, evaluation of the RPP, infection control practices, and workplace safety.

A respirator demonstration tool provided by NIOSH was used when observing interviewees don and doff N-95 respirators. During the respirator demonstration, staff observed participants donning the N-95 respirator and recorded their actions using the respirator demonstration tool. Participating facilities provided us with their written RPPs, which we reviewed for all essential components required by OSHA.

Site visit staff entered the de-identified data into a Microsoft Access database provided by NIOSH after the site visits. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

During the site visits, we completed 127 questionnaires of HCWs, 31 questionnaires of UMs, and 40 questionnaires of HMs. A total of 115 respirator demonstrations was observed (a mean of five per facility).

As shown in Table 1 , whereas all hospitals visited had respiratory protection policies present, 2 hospitals lacked a defined RPP (8.7%), and many were missing key components. Less than half of the programs reviewed contained a plan to evaluate the effectiveness of the RPP (47.8%) or a designated RPP administrator (39.1%). Only 69.6% of hospitals had the need for medical evaluation and clearance fully stated in the RPP, with 21.7% partially stating it. The fit-testing component of an RPP should provide guidance in choosing the brand, model, and size of respirator that provides the best fit for each individual employee, as well as instructions for proper wear procedures. This was only fully included in 65.2% of RPPs reviewed. Guidance pertaining to the use and storage of respirators was fully included in the RPPs 65.2% and 60.9% of the time, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Respiratory protection program written policy elements present: N = 23

| Elements | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of written RPP: to provide a clear policy and specific procedures for the use of respirators in protecting employees from respiratory hazards | 21 | 91.3 |

| Program administrator: to assign responsibility for ensuring full implementation and evaluation of the written program to a suitably trained employee | 9 | 39.1 |

| Medical evaluation: to ensure that employees are able to wear respirators safely | 16 | 69.6 |

| Fit testing: to choose the brand, model, and size of respirator that provides the best fit for each individual employee and to provide an opportunity to review proper donning and doffing procedures | 15 | 65.2 |

| Record keeping: to maintain a record of individual medical evaluations and fit tests and to ensure the availability of the written program | 12 | 52.2 |

| Training and information: to ensure that employees understand their facility's written program and the purpose of and limitations of respirators and that they are trained in the specific procedures for proper use and maintenance | 15 | 65.2 |

| Respirator selection: to determine which types of NIOSH-approved respirators will be required for each job or task based on an evaluation of respiratory hazards | 14 | 60.9 |

| Use of respirators: to provide clear, written policies and procedures for proper use of respirators by employees | 15 | 65.2 |

| Maintenance and care of respirators: to provide clear, written procedures for storage, care, and maintenance of respirators | 14 | 60.9 |

| Program evaluation: to ensure that the written program is being implemented and that it continues to be effective | 11 | 47.8 |

NIOSH, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health; RPP, respiratory protection program.

Based on their responses, UMs and HMs were generally very aware and knowledgeable about their hospitals' respiratory protection policies, and appropriate respiratory protection practices (Table 2 ). Health care workers reported that the N-95s they were fit tested for were easily accessible 92.9% of the time and stored close to the point of use 94.5% of the time (Table 2).

Table 2.

HCW, UM, and HM responses

| HCW, N = 127 |

UM, N = 31 |

HM, N = 40 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Does your facility have a written respiratory protection program? | ||||||

| Yes | 113 | 89.0 | 29 | 93.5 | 40 | 100.0 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Don't know | 14 | 11.0 | 2 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Are the correct model and size of N-95 respirators available when you need them? | ||||||

| Yes | 118 | 92.9 | N/A | N/A | ||

| No | 4 | 3.2 | ||||

| Don't know | 5 | 3.9 | ||||

| Is respiratory equipment located close to the point of use (ie, rooms with suspected or confirmed seasonal influenza or patients on airborne precautions)? | ||||||

| Yes | 120 | 94.5 | 31 | 100.0 | 40 | 100.0 |

| No | 3 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Don't know | 4 | 3.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Does your facility have powered air-purifying respirators available for use when employees need them? | ||||||

| Yes | 76 | 59.8 | 26 | 83.9 | 36 | 90.0 |

| No | 2 | 1.6 | 5 | 16.1 | 2 | 5.0 |

| Don't know | 49 | 38.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 5.0 |

| What would most commonly trigger you/staff to use an N-95 respirator (respiratory protection)? | ||||||

| Patient's signs and symptoms | 73 | 57.5 | 20 | 64.5 | 27 | 69.2 |

| Laboratory confirmation of disease | 4 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Physician order | 5 | 3.9 | 2 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sign on the door of a patient's room | 27 | 21.3 | 5 | 16.1 | 4 | 10.3 |

| Verbally informed by coworkers | 3 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 15 | 11.8 | 4 | 12.9 | 7 | 18.0 |

| Don't know | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.6 |

| Do employees receive medical evaluation and clearance before being allowed to wear a respirator? | ||||||

| Yes | 123 | 96.8 | 31 | 100.0 | 39 | 97.5 |

| No | 3 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Don't know | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Does your facility offer you training in how to properly use respiratory protection? | ||||||

| Yes | 123 | 96.9 | 31 | 100.0 | 39 | 97.5 |

| No | 3 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Don't know | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.5 |

| How often are employees required to attend respirator training? | ||||||

| Once at hire, and then annually | 104 | 81.9 | 26 | 83.9 | 38 | 95.0 |

| Once at hire only | 7 | 5.5 | 2 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| No requirements | 2 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.5 |

| Don't know | 12 | 9.5 | 1 | 3.2 | 2 | 2.5 |

| Other | 2 | 1.6 | 2 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Workers at my workplace use respirators when they are required. | ||||||

| Agree | 111 | 87.4 | 30 | 96.8 | 39 | 97.5 |

| Disagree | 9 | 7.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Don't know | 7 | 5.5 | 1 | 3.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Did you receive, or do you intend to receive, the seasonal flu vaccine this year? | ||||||

| Yes | 95 | 74.8 | N/A | N/A | ||

| No, but I do intend to get it | 11 | 8.7 | ||||

| No, and I do not intend to get it | 20 | 15.8 | ||||

| Don't know | 1 | 0.8 | ||||

| Last year, were flu vaccines made available to you/employees at no cost? | ||||||

| Yes | 122 | 96.1 | 31 | 100.0 | 40 | 100.0 |

| No | 2 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Don't know | 3 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| This year, were flu vaccines made available to you/employees at no cost? | ||||||

| Yes | 126 | 99.2 | 31 | 100.0 | 40 | 100.0 |

| No | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Don't know | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

HCW, health care worker; HM, hospital manager; UM, unit manager.

Hospitals are required to have PAPRs on hand if there is an employee who cannot be cleared to wear an N-95. PAPRs are also desirable to use when performing a high-risk, aerosol-generating procedure. When asked whether the facility had PAPRs available for use when employees need them, 59.8% of HCWs responded “Yes” (Table 2). When asked about the most common trigger for use of respiratory protection, HCWs stated that 57.5% of the time it is a “Patients' signs and symptoms” (Table 2).

Medical evaluation and clearance, in addition to fit testing, is required at hire before being allowed to wear an N-95 respirator. HCWs stated that they did receive medical evaluation and clearance 96.9% of the time (Table 2).

Facilities are required to offer employees training about how to use respiratory protection. HCWs reported this 96.9% of the time (Table 2). OSHA requires that respirator training be provided at hire and every year thereafter. HCWs reported that this standard was met 81.9% of the time (Table 2). The overall beliefs of those interviewed were that employees used respirators when they were required: HCWs stated this 87.4% of the time (Table 2).

Vaccinations are important in preventing the spread of influenza within the health care facility. Of those surveyed, 74.8% reported being vaccinated for the 2011-2012 season (Table 2). The majority of HCWs reported that flu vaccinations were made available to them at no cost during the 2010-2011 flu season (96.1%) and the 2011-2012 season (99.2%) (Table 2). To conserve supplies in the event of a shortage, while still reducing the risk of exposure to influenza, employees can redon a specific N-95 as long as it has not been soiled or functionally compromised. Facilities should state in the RPP the specifics of reuse. The N-95 should be stored in a paper bag (or other breathable container) between uses. Less than half of all those surveyed were aware of a reuse policy in their facility. Of those who stated there was a policy for the reuse of N-95s, the majority was unaware of the recommendation to store an N-95 in a breathable container between uses (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Reuse policies in the event of a shortage

| HCW, N = 127 responses |

UM, N = 31 responses |

HM, N = 40 responses |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Does your facility have a written policy for the redonning (reuse) of N-95 respirators? | ||||||

| Yes | 54 | 42.5 | 13 | 41.9 | 18 | 45.0 |

| No | 36 | 28.4 | 10 | 32.3 | 19 | 47.5 |

| Don't know | 37 | 29.1 | 8 | 25.8 | 3 | 7.5 |

| If the facility does have a written policy for the redonning (reuse) of N-95 respirators, how are employees instructed to store N-95 respirators between doffing (removing) and redonning? | ||||||

| In a plastic bag | 21 | 38.9 | 8 | 61.5 | 7 | 38.9 |

| In a paper (breathable) bag | 2 | 3.7 | 1 | 7.7 | 6 | 33.3 |

| Carried by the employee | 3 | 5.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hang in a designated area | 9 | 16.7 | 2 | 15.4 | 3 | 16.7 |

| Other | 5 | 9.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.6 |

| Don't know | 14 | 25.9 | 2 | 15.4 | 1 | 5.6 |

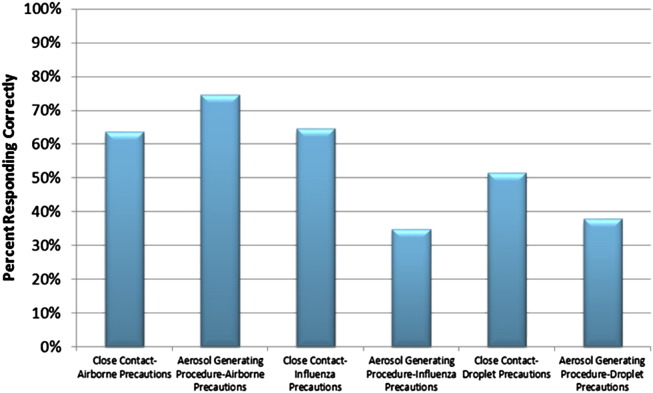

All HCWs were asked questions about the appropriate respirator that would be required for different scenarios and levels of precaution. A respirator selection element was included in 60.9% of the RPPs reviewed (Table 1). When asked during interviews about the selection of appropriate respiratory protection based on precautions (droplet, influenza, airborne) and task (close contact, aerosol-generating procedure), results were wide-ranging (Fig 3 ). These respirator selection requirements are based on Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee guidance.6

Fig 3.

Percentage of HCWs who selected the appropriate respiratory protection for task and suspected/confirmed infectious disease.

The majority of respondents reported that they had access to the model and size for which they received a fit test (97.4%). We observed that participants performed well in positioning the N-95 properly on the face (92.2%), properly placing the straps (87.8%), properly forming the nose clip (85.2%), and having no facial hair under the seal (93.0%). Only 36.5% of participants performed the seal check, which is imperative in determining whether a proper fit has been achieved. The respirators were properly removed using the straps 65.2% of the time (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Respirator demonstration observation results: n = 115

| n | % Compliant | |

|---|---|---|

| Do you have access to the respirator model and size for which you have been fit tested? | 112 | 97.4 |

| Is the respirator correctly positioned on the face? | 106 | 92.2 |

| Is there any facial hair under the seal? | 107 | 93.0 |

| Are the straps correctly placed? | 101 | 87.8 |

| Is the nose clip properly formed around the nose? | 98 | 85.2 |

| Was a user seal check performed? | 42 | 36.5 |

| Was the respirator removed using the straps? | 75 | 65.2 |

Discussion

Strengths of this study include the enthusiastic and cooperative response from hospital administrators that participated. HCWs, UMs, and HMs were also obliging during the interviews and respirator demonstrations. Hospital administrators were very considerate about finding employees in other units to interview when ED staff was unavailable. We were able to obtain participation from hospitals throughout NYS, representing urban, suburban, and rural areas, as well as teaching institutions. Sizes ranged from <150 to >500 beds.

There are a number of limitations with this study. Whereas written RPPs were provided by facilities and reviewed for accuracy, all survey results were self-reported. Because the project is voluntary, selection bias is a concern because those who choose to participate are concerned with proper respiratory protection and therefore may be more likely to practice it than those who did not participate. Convenience sampling was employed to interview HCWs, as not to interfere with patient care. This nonprobabilistic method can result in an under- or over-representation of the population of interest. Site visits were conducted during regular weekdays and took approximately 4 hours to complete. Because of the time frame and limited resources, it was not possible to interview workers during evening and night shifts. Whereas HCWs were cooperative in participating in the respirator demonstration, we were unable to observe N-95 use during patient care activities. Therefore, we could not accurately assess whether proper control measures were undertaken when a patient with airborne, influenza, or contact precautions was identified. Although the primary focus of the study was on EDs, they can become busy quickly, and it was not always possible to obtain the number of interviews desired. Although these limitations make it difficult to generalize the findings, the surveys were a useful tool in evaluating the knowledge, beliefs, and practices of hospital personnel.

All facilities surveyed had respiratory protection policies in place (even if a defined RPP was absent), and employees were compliant to varying degrees. The common deficiencies recorded included incomplete RPP components, inappropriate respirator selection, failure to perform the seal check when donning a respirator, and unawareness of best practices for the reuse of respirators in the event of a shortage. The findings from this study suggest that HCWs may be unnecessarily exposed to influenza and other infectious diseases because of unawareness of respiratory protection policies and practices, as well as inadequacies in education and training.

Unfamiliarity and unawareness of the policies are issues among hospital employees at all levels. Commonly, information about respiratory protection policies did not make its way down the “chain”—HMs (100.0%) were more aware of the presence of an RPP than UMs (93.5%), whereas UMs were more aware than HCWs (89.0%) based on the percentage of correct responses (Table 2).

Although N-95 respirators are being widely used, significant gaps in training as well as appropriate donning and doffing procedures exist. A representative at one of the participating facilities stated they did not train employees to perform a seal check because they thought it was an unnecessary step. A seal check is required by the OSHA standard (the facility was made aware of this), and research has demonstrated that a seal check is beneficial to HCWs who have been previously fit tested.7 Without a proper seal between the user's face and the respirator, inhaled air may bypass the respirator's filter, putting the user at risk for exposure.8

Influenza vaccination has been repeatedly demonstrated to be an effective means in protecting patient health, but inoculation rates in the United States have remained low.9, 10 Vaccination rates have increased over the past decade, and it is estimated that overall vaccination coverage was 63.5% of HCWs during the 2010-2011 season.11 Of the HCWs interviewed for this project, 74.8% reported that they had received the flu vaccine that year (Table 2). Although better than the national average, this is still below the “Healthy People 2020” goal of 90% coverage among HCWs.9, 11, 12 Making vaccines available to HCWs at no cost, along with other initiatives implemented by hospitals, have helped to increase vaccination coverage.9 Many managers and HCWs surveyed also reported the success of initiatives such as mobile vaccination carts and mandatory declinations.

Many RPPs lacked a specifically defined RPP program administrator. Hospitals should assign responsibility of the RPP to 1 individual, such as the infection control manager or the employee/occupational health manager, and state this position in the RPP. The program administrator should be part of the creation, implementation, and evaluation of the RPP. Another gap that existed in the RPPs was the lack of specific record-keeping procedures. The purpose of record keeping is to maintain a record of individual medical evaluations and fit tests and to ensure the availability of the written program. We recommended that the hospitals assign all record-keeping responsibilities to one department, ideally the department that administers the RPP.

The last major gap that existed was the lack of formal RPP evaluation procedures. The purpose of RPP evaluation is to assess the implementation and efficacy of the written program. We recommended that the hospitals perform an annual RPP evaluation that examines respirator fit, appropriate respirator selection, proper respirator use, and proper respirator maintenance. We also recommended that hospitals implement focus groups or an employee survey distributed during the evaluation to gather input from employees.

In addition to the overall need for more comprehensive RPPs, education, and policy awareness practices, we made other recommendations to the participating facilities during and after site visits. As previously stated, selection of the appropriate PPE for specific tasks and infectious disease was a common issue. We recommended that the hospitals have a reference sheet readily available in a common area where employees could look to determine the PPE needed (for example, a flyer posted in the nurses' station). Another recommendation we made was to verify that employees knew what model/size N-95 respirator for which they had been fit tested. The majority of ED staff was aware of the model/size they needed (because they use N-95 protection frequently), but staff on other units (medical/surgical, intensive care unit) would sometimes state they were unsure of the model/size for which they had been fitted because they use respiratory protection much less frequently. As a possible solution, we recommended that staff be given a sticker at the time of fit testing with their model/size N-95 information written on it. This sticker could then be placed on their ID card (or in their locker) for quick reference.

For seasonal influenza, the CDC recommends that a surgical or procedure mask, rather than an N-95, be worn by HCWs when in close contact with patients who exhibit symptoms of influenza.13 However, hospitals continue to need and use N-95s for the control of airborne infectious diseases such as tuberculosis.14 N-95s are also a key infection control component for response to certain bioterror agents, such as the smallpox virus,15 as well as emerging infectious diseases, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome.16

As part of the greater infection control plan, hospitals must have an RPP in place to ensure that all respiratory equipment is used in a safe and effective manner. The program must identify an RPP administrator and include written policies and procedures for fit testing, employee training, medical clearance, appropriate selection of respirators, maintenance, record keeping, and program evaluation. Having these protocols in place is necessary for ensuring the effectiveness of respiratory protection, protecting health care personnel and patients, and preventing influenza transmission within health care settings.

Acknowledgments

Elizabeth Rees and Nicholas Pavelchak had full access to all the original data in this study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors thank Dr Eileen Franko, Dr Kitty Gelberg, and Karen Cummings for their valuable contributions to this paper, as well as the infection control professionals and hospital personal who donated their time to this project.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) contract number 254-2010-36371.

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

References

- 1.US Department of Health & Human Services. Pandemic flu history. Flu.gov. Available from: http://www.flu.gov/pandemic/history/index.html. Accessed July 11, 2012.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Key facts about influenza (flu) & flu vaccine. 2012. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/keyfacts.htm. Accessed August 10, 2012.

- 3.Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) (database). Albany [NY]: New York State Department of Health; 2007-2010. Available from: http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/sparcs/. Accessed August 9, 2012.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance on infection control measures for 2009 H1N1 influenza in healthcare settings, including protection of healthcare personnel. 2009. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/guidelines_infection_control.htm. Accessed July 11, 2012. [PubMed]

- 5.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Respirator trusted-source information page. 2012. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/topics/respirators/disp_part/RespSource.html. Accessed July 11, 2012.

- 6.Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. 2007 Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/isolation/isolation2007.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Viscusi D., Bergman M., Zhuang Z., Shaffer R. Evaluation of the benefit of the user seal check on N-95 filtering facepiece respirator fit. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;9:408–416. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2012.683757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Occupational Safety and Health Administration . Occupational Safety and Health Administration; Washington [DC]: 2009. Pandemic influenza preparedness and response guidance for healthcare workers and healthcare employees. Publication OSHA 3328–05R. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quan K., Tehrani D., Dickey L. Voluntary to mandatory: evolution of strategies and attitudes toward influenza vaccination of healthcare personnel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:63–70. doi: 10.1086/663210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemaitre M., Meret T., Rothan-Tondeur M. Effect of influenza vaccination of nursing home staff on mortality of residents: a cluster-randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1580–1586. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Influenza vaccination coverage among health-care personnel, United States, 2010-2011 influenza season. MMWR. 2011;60:1073–1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Department of Health and Human Services . US Department of Health and Human Services; Washington [DC]: 2011. Healthy People 2020. Increase the percentage of health-care personnel who are vaccinated annually against seasonal influenza. Objective IID-12.9.http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicid=23 Available from: Accessed August 15, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention strategies for seasonal influenza in healthcare settings. 2013. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/healthcaresettings.htm. Accessed February 20, 2013.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care settings, 2005. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5417a1.htm?s_cid=rr5417a1_e. Accessed February 20, 2013.

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smallpox response plan and guidelines. 2007. Available from: http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/response-plan/files/guide-c-part-1.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2013.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim domestic guidance on the use of respirators to prevent transmission of SARS. 2003. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/sars/clinical/respirators.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2013.