Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate practical barriers to personal protective equipment (PPE) use found through health care personnel (HCP) training sessions held during and after the 2015 Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak in Korea. Difficulties observed were ill-fitting sizes, anxiety, confusion from unstandardized protocols, doubts about PPE quality and effectiveness, and complexity of using several PPE items together. Further research to generate robust evidence and repeated HCP trainings are necessary to ensure HCP and patient safety in future outbreaks.

Key Words: Health care personnel, Personal protective equipment, Focus group interview

The inter- and intrahospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in South Korea resulted in 38 deaths, 186 confirmed cases, and 16,693 quarantines between May and December 2015.1 For MERS patient care, the Korean government provided level-D personal protective equipment (PPE) sets to designated hospitals (Fig 1 ). This study aimed to evaluate practical barriers to PPE use found through health care personnel (HCP) training sessions held both during and after the MERS outbreak at Korean hospitals.

Fig 1.

The level-D personal protective equipment set provided by the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, consists of a coverall (with an attached hood and no attached foot cover), N95 respirator, goggles, inner gloves, outer gloves, and shoe cover. This picture was taken and provided with permission by the infection control department at the Seoul National University Hospital.

Methods

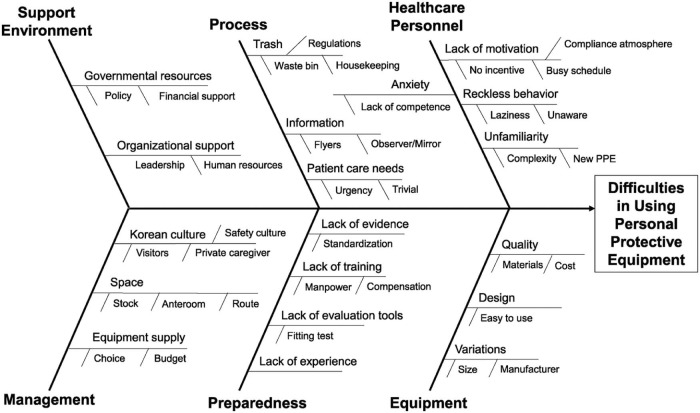

With institutional review board approval, a focus group interview was conducted on March 17, 2017, with infection control nurse (ICN) leaders from major hospitals. Upon participants' consent, a brief survey on demographic characteristics was completed before the focus group interview. Participants' responses and discussions were recorded anonymously. The content was analyzed by theme with additional weighted factors: frequency, specificity, emotion, and extensiveness.2 A fishbone diagram summarizing the contributing factors to PPE use difficulties and reflecting MERS-specific conditions was created at a consultation with 2 board members of the Korean Association of Infection Control Nurses. All participants approved the theme categories and the fishbone diagram.

Results

From Seoul and Chungcheongnam-do, 7 ICN leaders participated. Their hospitals (1,122 average beds [range, 706-1,980 beds]) had at least 3 probable MERS cases (range, 3-5,300; 0-82 confirmed cases) during the outbreak. Each leader with an average of 10 years of ICN experience directed PPE trainings for an estimated 50-5,495 HCP, mostly using fluorescent markers. All participants enumerated difficulties in developing hospital-customized PPE protocols and trainings, facing PPE variations, and inconsistent donning/doffing orders in guidelines.

Difficulties observed were classified by theme: ill-fitting PPE sizes, anxiety, confusion from unstandardized protocols, doubts about PPE quality and effectiveness, and complexity of using several PPE items together. Due to the 1 size (ie, extra large) of level-D coveralls, petite female HCP had baggy fits that blunted their work processes. In contrast, for large male HCP with problems rolling down the coverall off their shoulders, 1 hospital changed its protocol to advise them to pull the coverall down by holding the sleeves with hands inside the sleeves on the back. Likewise, cup-shaped N95 respirators often developed cracks in the chin area for small-jawed female HCP. When HCP failed the fit-test or found fluorescent lotion contamination, it provoked anxiety. Evolving PPE protocols over the prolonged outbreak period caused confusion for HCP at later PPE trainings attributable to changes from practical experience or other hospital benchmarks. Inconsistent government protocols (eg, different holding locations for N95 respirators; that is, by side strings or the front) increased confusion. Participants also wanted valid evidence on effective hours for PPE items. The most common doffing difficulty was locating the coverall zipper-slider and pulling it down with gloved hands. Sometimes the overlapping parts of different PPE items were ill-fitted (eg, gaps between goggles and N95 respirator). With more PPE items, the doffing order became complicated and confusing. For example, the outer gloves were not the first doffing item when untying the outer shoe cover strings first.

Category branches for the fishbone diagram (Fig 2 ) included support environment, management, process, preparedness, equipment, and HCP. Depending on hospital budgets, the quality of PPE preparedness differed (eg, purchases of powered air purifying respirators). Limited hospital layouts disrupted space management for PPE use. In the presence of hospital visitors, PPE use was inconvenient. Various underlying factors included task characteristics (from trivial to emergent), selection among various PPE, and absent incentives for HCP compliance.

Fig 2.

A fishbone diagram presenting a comprehensive summary from the focus group interview.

Discussion

Our findings provide insights into improving PPE practices in modern hospitals. Regarding ill-fitting sizes, a 2016 UK survey on women's experiences wearing PPE found the coverall to be among the worst-fitting PPE types but commonly accepted as “part of the way things are.”3 Moreover, female emergency services workers were ranked as the most hampered in their work and with the least comfortable PPE fits.3 Unique to this study's findings, evolving protocols may also reflect the desire of HCP to use PPE at their preference for either heavy use for personal safety (eg, taping over gaps between hood and coverall) or modified use for their convenience (eg, triple gloving for logistical efficiency). Sometimes ICN leaders had to allow HCP their own methods to assuage their anxiety, due to a lack of scientific evidence on various scenarios.

Although HCP were reported to make changed mistakes while avoiding previous mistakes, even after receiving feedback on their PPE contaminations,4 more training certainly improves HCP PPE use.5 Through direct MERS contact, HCP can run a higher risk of infection: A 5.1-fold increased risk was reported among family care givers.6 The Korean MERS outbreak infected 39 HCP,1 and greater numbers of HCP could have been infected if PPE trainings had not been provided. Although many Korean HCP volunteered for MERS care, they may have faced the dilemma of working or quitting, as some Canadian nurses experienced during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak.7 Therefore, more suitable PPE products for female HCP and further research to generate robust evidence are necessary for developing gold-standard PPE protocols to ensure HCP and patient safety in future outbreaks. Thereafter, repeated training would increase HCP competencies in PPE use.

Footnotes

Funded by the 2016 Seoul National University Invitation Program for Distinguished Scholars.

This study was presented at the Fourth International Conference on Prevention and Infection Control, Geneva, Switzerland, June 21, 2017 (poster presentation #117).

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

References

- 1.Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare The 2015 MERS outbreak in the republic of Korea: learning from MERS. 2016. http://www.mohw.go.kr/front_new/jb/sjb030301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=032903&CONT_SEQ=337407&page=1 Available from:

- 2.Krueger R.A.C.M.A. 5th ed. Sage publication; London, UK: 2015. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prospect Women's personal protective equipment: one size does not fit all. 2016. https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2016-01299-Leaflet-booklet-Women%27s-PPE–One-Size-Does-Not-Fit-All-Version-26-09-2016%20%282%29.pdf Available from:

- 4.Kang J., O'Donnell J.M., Colaianne B., Bircher N., Ren D., Smith K.J. Use of personal protective equipment among health care personnel: results of clinical observations and simulations. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casalino E., Astocondor E., Sanchez J.C., Diaz-Santana D.E., Del Aguila C., Carrillo J.P. Personal protective equipment for the Ebola virus disease: a comparison of 2 training programs. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:1281–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron R.C., McCormick J.B., Zubeir O.A. Ebola virus disease in southern Sudan: hospital dissemination and intrafamilial spread. Bull World Health Organ. 1983;61:997–1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care The SARS Commission Executive Summary—spring of fear. 2006. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/e_records/sars/report/v1-pdf/Volume1.pdf Ontario, Canada; Available from: