Abstract

This study was conducted to assess the knowledge of H1N1 among medical students, their perceptions, and behavioral intentions in the wake of the H1N1 pandemic influenza. There were significant gaps in important self-isolation protocols and preventive measures. Increased contact with both patients and colleagues can lead to unintentional transmission and contraction of influenza. Universities should introduce and encourage infection control guidelines into routine curriculum.

Key Words: Infection control, Medical education, Pandemic

Early outbreaks of a new respiratory virus were first reported in April 2009, which was later identified as the H1N1 virus.1 The first known confirmed case in Pakistan was reported on November 08, 2009.2 By January 2010, Pakistan’s case fatality rate was low,3 but the actual number of cases to have occurred is thought to be much higher than the reported figures.4

Medical universities pose as an important source of infection because of their large and crowded student population as well as their large vulnerable patient population. Nurses from first through fourth year, medical students from first through fifth year, and residents all study and practice in the medical university and accompanying hospital. Without adequate knowledge or perceived seriousness of contracting a given pandemic, students will not be inclined to comply with recommended behavioral adaptations. As Brug et al have stated, one must first be aware of the potential risk to be motivated enough to begin to adopt any protective measures.5 Having adequate knowledge and awareness about an infectious outbreak begins with an appropriate implementation of lectures by the university that are essential in affecting the level of concern of medical students. Compliance with infection control measures is directly related to the level of concern; the greater the concern level, the more likely the students will adhere to the appropriate prevention guidelines. The objective of the study is to assess the awareness, perceptions, and behavioral intentions of medical students to the H1N1 pandemic.

Methods

This was a questionnaire carried out over 5 weeks from February 11 to March 18, 2010, at Isra University, Hyderabad. At the time of our study, a total of 528 students were enrolled in first through fifth year. A simple random sampling methodology was conducted using a Texas Instrument (TI)-87 scientific calculator (Dallas, TX) to obtain numbers from the students’ enrollment list. The survey was distributed to 264 medical students at a confidence interval of 95% and assuming a margin of error at 4.3%.

The self-developed questionnaire assessed knowledge, behavioral intentions, and perceptions of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009, which was referred to by its vernacular alternative, “swine flu.” For this, searches on relevant literature were carried out. A team of medical students carried out the data collection. The questionnaires were pilot tested on a convenience group of 20 students and modified accordingly. The final version consisted of multiple choice questions and was handed out in classrooms after obtaining consent. Ethics approval was obtained from the relevant Ethics Committee. Sociodemographic details of each student included age, marital status, medical year, and locality. Only those who were aware of the H1N1 pandemic were asked (1) mode of transmission; (2) signs and symptoms of H1N1; (3) response if H1N1 symptoms are found; and (4) concern about contracting H1N1.

Assessment of the responses of recommended precautionary measures was in accordance to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). All randomly selected medical students of Isra University were included. Students who were absent during the study duration or who refused to participate were excluded.

The data were analyzed using the SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). We regarded a P value of less than 0.05 as statistically significant. Descriptive statistics were employed to determine the demographic and clinical variables.

Results

Out of a total of 264 students, 251 filled out the questionnaire completely with a response rate of 95.1%. Of all the students, 241 (96%) had heard of H1N1, and only 10 (4%) were unaware of the new pandemic.

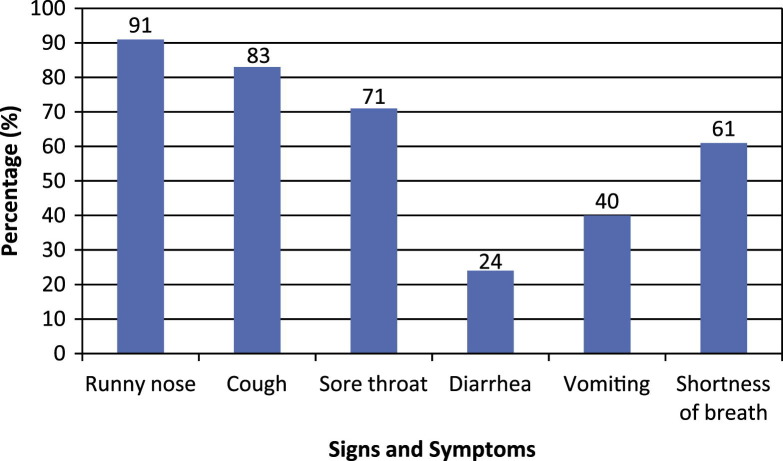

The majority of the students (52%, n = 126) had accurate information about the mode of transmission. One hundred ninety-seven students also accurately specified the indirect mode of transmission via H1N1-infected objects. Regarding H1N1 signs and symptoms, few students were able to correctly identify diarrhea and vomiting (23% and 40%, respectively). Most common symptoms identified were runny nose (91%), cough (83%), and sore throat (71%) (Fig 1 ).

Fig 1.

Signs and symptoms of H1N1 influenza.

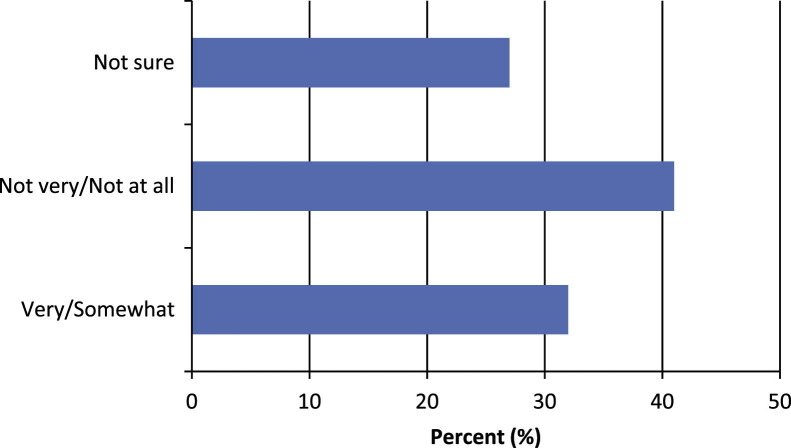

Figure 2 illustrates the students’ level of concern of being infected. Almost half of the students (41%, n = 99) were not very or not at all concerned about contracting the H1N1 virus. Only 32% of students were very or somewhat concerned, and 27% of students were not sure.

Fig 2.

Perceived risk of contracting H1N1 influenza.

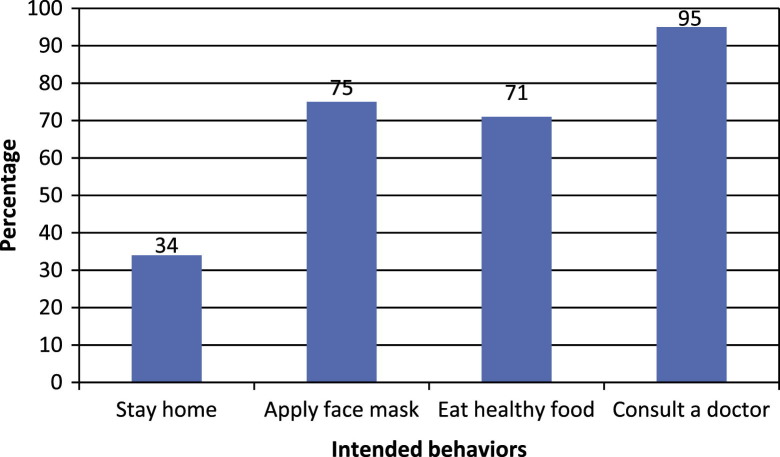

When asked about the predicted response upon discovering any H1N1 symptoms, 66% of the students reported that they would not stay at home (Fig 3 ). However, 75% (n = 181) of students would apply a face mask if necessary. The use of face masks was met with the most resistance (29%, n = 36) among students aged 18 to 20 years (P = .047). The only significant predictor of concern was the failure of usage of face masks by students who were not concerned about contracting H1N1. Students with the lowest concern level were more likely to refuse the use of a protective face mask (P < .021).

Fig 3.

Intended behaviors upon discovering H1N1 infection.

Discussion

According to the CDC, H1N1 influenza is spread from person to person by coughing, sneezing, or talking. A study performed earlier in the pandemic by Khowaja et al6 reported that medical students did not have complete knowledge about the mode of transmission. However, in our study, students were able to identify air droplets as the mode of transmission that helped to contribute to the students’ willingness to wear a face mask when necessary. A previous study conducted on the varicella virus by Hesham et al7 showed that medical students had significant knowledge of its spread and symptoms and believed it to be a serious disease but were not necessarily vaccinated.

Although the H1N1 virus presents with influenza-like symptoms, diarrhea and vomiting are 2 symptoms that are unique to H1N1,8 which students failed to identify. University health supervisors should establish a protocol to recognize H1N1 symptoms.

Greater perceived risk of susceptibility can lead to greater compliance of health behaviors.5 We found that only 32% of the students believed themselves to be at a risk of contracting H1N1. This finding is comparable with another study conducted by Eastwood et al,9 which showed that only 25% of the residents considered themselves to be at a risk of contracting the virus. It is not surprising to find a low perception risk among the students because of the low number of laboratory-confirmed outbreaks reported in the newspaper and media.4

The use of face masks was met with the most resistance (15%, 36/241) among students aged 18 to 20 years. This finding is consistent with May et al,10 who reported young adults between 16 and 24 years were the least willing to comply with the use of face masks. The implementation of a face mask in the event of an illness was met with the most resistance from students who did not perceive themselves to be at risk. The low usage of face masks is of concern, placing both patients and colleagues at risk of contamination. The optimism of not being at risk results in a false sense of security and therefore a lack of precaution. Educating students on the utilization of proper CDC guidelines is required to prevent iatrogenic infections. A study conducted by Wong et al assessed the potential spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome among previously healthy medical students and found that specific control measures can prevent the spread of pathogens by respiratory droplets.11

The recommendation to stay at home when ill was met by resistance in most students. This behavior poses a serious threat of student to colleague and student to patient transmission if infected students do not remain isolated. Brown et al,12 however, reported the contrary, finding that the majority of their respondents were more likely to self-isolate during an influenza. The factors that led to their decision were not assessed, but universities need to enforce proper compliance to health guidelines and set up alternative teaching sources for students. A study performed by Agahaizu et al13 on newly emerging infectious diseases revealed that, because of lack of regulation of infection control guidelines, symptomatic health care workers continued to attend their duty and therefore became a risk for transmission of infection.

Students should be taught in small group scenarios by local health department officials who have adequate knowledge of infection control. Kaiser et al14 believe universities must devise a well-organized collaboration with different organizations to effectively utilize medical students in the event of public health emergencies. Preparing students to understand their roles and responsibilities, goals to accomplish, and the need to provide professional patient satisfaction are key elements in ensuring proper infection control. Reliable assessments should be made throughout these exercises, thus ensuring adherence to these methods.

Limitations

This survey measured the sample views at a specific point in time; therefore, the beliefs and attitudes reflect the information available at that time. Furthermore, we only recruited medical students of 1 private medical university in Hyderabad. Therefore, our sample may not be a representation of other larger university student populations whose concern levels and response to a pandemic may be different based on greater susceptibility of infection transmission. Not all of the students were available or responded (5%). Our study asked about the intended measures to be taken but not the actual uptake of these measures. Hence, this survey may not reflect the students’ real world responses.

Conclusions

Our study found that the medical students had sufficient knowledge regarding the H1N1 pandemic, but they lacked understanding of some key elements. Infection control guidelines and training should be introduced into routine curriculum. University health supervisors should establish a guideline to recognize symptoms of the H1N1 virus. They should also promote self-isolation and form alternate teaching strategies for infected students. A complete knowledge of the disease can ensure proper intervention especially in developing countries where routine testing may not be available.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Professor Dr Nishat Zohra for her assistance in the completion of this project and Meena Memon, Summaya Anjum, Sumaira Qayyom, and Summia Akram for their help in data collection.

Footnotes

Author contributions: All authors helped in data collection. Z.A.H. carried out the study design and drafted the final manuscript. Data analysis and result interpretations were carried out by F.A.H. and S.A.H. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. What is the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/frequently_asked_questions/about_disease/en/index.html. Accessed January 28, 2010.

- 2.First casualty of swine flu in Pakistan. Available from: http://www.thenews.jang.com.pk/TodaysPrintDetail.aspx?ID=207349&Cat=7&dt=11/8/2009. Accessed May 21, 2010.

- 3.14 Deaths from A(H1N1) flu reported so far in Pakistan. Available from: http://balita.ph/2010/01/07/14-deaths-from-ah1n1-flu-reported-so-far-in-pakistan/. Accessed May 21, 2010.

- 4.World Health Organization. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009: update 75. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2009_11_20a/en/index.html. Accessed January 18, 2010.

- 5.Brug J., Aro A.R., Richardus J.H. Risk perceptions and behaviour: towards pandemic control of emerging infectious diseases. Int J Behav Med. 2009;16:3–6. doi: 10.1007/s12529-008-9000-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khowaja Z.A., Soomro M.I., Pirzada A.K., Yoosuf M.A., Kumar V. Awareness of the pandemic H1N1 influenza global outbreak 2009 among medical students in Karachi. Pakistan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:151–155. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hesham R., Cheong J.Y., Hasni J.M. Knowledge, attitude and vaccination status of varicella among students of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) Med J Malaysia. 2009;64:118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Key facts about swine influenza (Swine flu). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/swineflu/key_facts.htm. Accessed January 18, 2010.

- 9.Eastwood K., Durrheim D., Jones A., Butler M. Acceptance of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza vaccination by the Australian public. MJA. 2010;192:33–36. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.May L., Katz R., Johnston L., Sanza M., Petinaux B. Assessing physicians in training attitudes and behaviors during the 2009 H1N1 influenza season: a cross-sectional survey of medical students and residents in an urban academic setting. Influenza Other Resp Viruses. 2010;4:267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong T.-W., Lee C.-K., Tam W., Lau J.T.-F., Yu T.-S., Lui S.-F. Cluster of SARS among medical students exposed to single patient, Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:269–276. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown L.H., Aitken P., Leggat P.A., Speare R. Self-reported anticipated compliance with physician advice to stay home during pandemic (H1N1) 2009: results from the 2009 Queensland Social Survey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:138. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aghaizu A., Elam G., Ncube F., Thomson G., Szilagyi E., Eckmanns T. Preventing the next “SARS.” European healthcare workers’ attitudes towards monitoring their health for the surveillance of newly emerging infections: qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:541. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser H.E., Barnett D.J., Hayanga A.J., Brown M.E., Filak A.T. Medical students’ participation in the 2009 Novel H1N1 Influenza Vaccination Administration: policy alternatives for effective student utilization to enhance surge capacity in disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness. 2011;5:150. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2011.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]