Abstract

Qualitative fit testing for N95 respirators was conducted on 1271 health care workers. All male participants were fitted with a respirator. Six females, all under age 40 years, were not successfully fitted. The first-choice respirator provided a successful fit in 95.1% of the men and 85.4% of the women. Gender and age in women were significant factors associated with successful fitting. These differences should be considered when implementing a respiratory protection program.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of respirators approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) rated at a protection level of N95 or higher to protect against avian flu.1 An N95 filtering facepiece respirator also is recommended in the guidelines for protection from biological agents such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and tuberculosis.2, 3, 4

For a respirator to provide appropriate protection, fit testing and training in the correct use of the respirator are essential.5 The health care workers who acquired SARS during the outbreak in Toronto in 2003 were not fit tested and had not received adequate training in the correct use of personal protective equipment.6 As noted by Clayton and Vaughan,7 a successful fit test implies that the chosen respirator has the potential to provide an adequate fit but only if the wearer performs the user fit check each time that he or she dons a respirator.

Lee et al8 suggested specifying a fit test passing rate of at least 90% of randomly selected wearers as a criterion for a certified respirator. The passing rate is calculated as the number of participants passing a fit test divided by the total number of fit test participants. Facial characteristics, including face length and width, have been identified as important factors in correctly fitting a respirator.9 Understanding the factors that can affect the fit of respirators will be helpful when implementing a respiratory protection program. The aim of the present study was to determine whether age and sex could be factors in successful respirator fitting.

St. Mary's Hospital Center is a 316-bed university affiliated community hospital in Montréal, Québec. Hospital isolation protocols require the use of an N95 respirator by every worker entering a negative-pressure isolation room. Fit testing is strongly recommended, and workers are liberated during work hours for fit tests.

Four certified fit test providers conducted tests between May 2004 and December 2006. Participants refrained from eating or drinking for 30 minutes before the test. Males were required to be freshly shaven. A sensitization test ensured that the participants detected the test agent, Bitrex (Edinburgh, UK). Instructions were given on how to correctly don and adjust the respirator, and the manufacturer-recommended user fit checks were explained. Although this explanation adds to the length of the fit test appointment, it is critical that the user understand the importance of conducting the fit checks to ensure that the anticipated level of protection is achieved.

The fit test procedure was as follows. Under a hood, with the respirator in place, the participant was instructed to breathe normally, then deep breathe, move the head side to side, move the head up and down, and, finally, read a short text. At each step, the tester introduced Bitrex into the hood through a nebulizer. If at any time the participant sensed the presence of Bitrex, the test was stopped and counted as a failure. Each qualitative fit test lasted approximately 10 to 20 minutes. If the test was unsuccessful with the first choice of respirator, the participant rinsed his or her mouth with water and was given a candy before proceeding to the next respirator.

The Health Care N95 particulate respirator model 1870 (3M, Minneapolis, MN) was selected as the first choice. If it did not fit, then the tester chose either the Health Care N95 particulate respirator model 1860 (3M) or model 1860-S (3M), depending on the participant's perceived (but not measured) facial width and length. If still unsuccessful, then the next respirator was selected from the following: N95 particulate respirator model 8210 (3M), N95 particulate respirator model 2200N (Moldex-Metric, Culver City, CA), and Respir-X model SAP5200 (Total Source Manufacturing, Vista, CA).

The χ2 test was used to determine differences in success rate by gender and by age group in both sexes. Participants whose age was not identified (28 women and 17 men) were excluded from the analysis. SPSS version 10.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses.

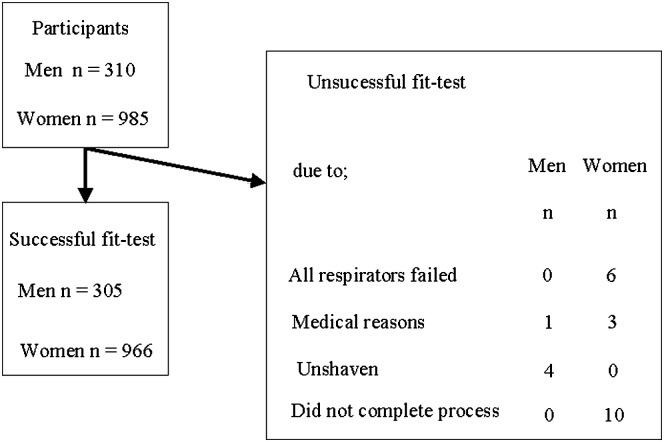

Figure 1 illustrates the results of the 1295 workers who participated in the program. Reasons for not completing the testing process included medical conditions, refusal to shave, and insufficient time to complete the test. Six women under age 40 years had unsuccessful fit tests for all 6 of the respirators tested.

Fig 1.

Fit test program participants.

Table 1 gives the results of successful fit tests for the various respirators by participant sex and age. The success rate for the first choice of respirator was 95.1% for men and 85.4% for women. There was a significant difference between men and women (P < .01) and among age groups in the women (P < .05). There were no significant differences among age groups for the men. The values in columns B through F are too small to be either statistically or clinically significant.

Table 1.

Successful respirator fit tests by sex and age (%)

| Men (n = 305) |

Women (n = 966) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | n | A | B | C | D | E | F | n | A | B | C | D | E | F |

| 19 to 29 | 48 | 93.8 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 215 | 80.9 | 5.1 | 13.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| 30 to 39 | 84 | 92.9 | 6.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 232 | 80.6 | 8.2 | 9.1 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| 40 to 49 | 98 | 95.9 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 241 | 88.0 | 3.3 | 8.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 50 to 59 | 46 | 95.7 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 195 | 90.8 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 60 to 71 | 12 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 55 | 85.5 | 1.8 | 12.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Unknown | 17 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 28 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Respirators: A, Health Care N95 particulate respirator and surgical mask model 1870 (3M).

B, Health Care N95 particulate respirator and surgical mask model 1860 (3M).

C, Health Care N95 particulate respirator and surgical mask model 1860S (3M).

D, Particulate respirator model 8210 (3M).

E, N95 particulate respirator model 2200N (Moldex-Metric).

F, Respir-X model SAP5200 (Total Source Manufacturing).

There were significant differences in the success rate between the sexes and among the age groups in the women. Lee et al 8 reported that some respirators demonstrated a gender difference in passing rate of > 10%. This finding is supported by our study, in which the first-choice respirator had about a 10% gender difference in pass rate.

The 6 women who had an unsuccessful fit test must undergo further testing. Using facial length and width measurements, it may be possible to plot these dimensions against the NIOSH bivariate panel used to help manufacturers determine optimum respirator design, as described by Zhuang et al.10

Many health care institutions are currently stockpiling respirators as part of a management plan for dealing with biological terrorism or a pandemic outbreak of respiratory disease. Although standardizing and limiting the type and number of respirators carried in inventory may be cost-efficient, in the event of a pandemic, manufacturers may be unable to produce sufficient quantities to meet the demand. Thus, it may be prudent to have workers fitted on more than one type of respirator.

Fit testing is an essential component of any respiratory protection program. Achieving a high overall success rate is possible. In this cohort, only a small percentage of the workers could not be successfully fitted with any of the respirators. Sex and age group are important factors to consider. The success rate for the first-choice respirator was considerably higher in the men than the women, indicating that women require a wider variety of respirator choices. More research is needed to identify other factors to assist decision makers in selecting appropriate respirators.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank Michel Perreault for his contribution to this study.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO interim guidelines on clinical management of humans infected by influenza A (H5N1), March 2, 2004. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/guidelines/clinicalmanage/en/. Accessed January 9, 2007

- 2.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim domestic guidance on the use of respirators to prevent transmission of SARS, May 3, 2005. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/sars/respirators.htm. Accessed January 9, 2007.

- 3.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Understanding respiratory protection against SARS. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/topics/respirators/factsheets/respsars.html. Accessed January 9, 2007.

- 4.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for preventing transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in healthcare settings, 2005. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/MMWR/PDF/rr/rr5417.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2008.

- 5.Coffey C.C., Lawrence R.B., Campbell D.L., Zhuang Z., Calvert C.A., Jensen P.A. Fitting characteristics of eighteen N95 filtering facepiece respirators. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2004;1:262–271. doi: 10.1080/15459620490433799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Health Canada. Cluster of severe acute respiratory syndrome cases among protected health-care workers—Toronto, Canada, April 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clayton M., Vaughan N. Fit for purpose? The role of fit testing in respiratory protection. Ann Occup Hyg. 2005;49:545–548. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mei046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee K., Slavcev A., Nicas M. Respiratory protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis: quantitative fit test outcomes for five type-N95 filtering-facepiece respirators. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2004;1:22–28. doi: 10.1080/15459620490250026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhuang Z., Coffey C.C., Ann R.B. The effect of subject characteristics and respirator features on respiratory fit. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2005;2:641–649. doi: 10.1080/15459620500391668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhuang Z., Bradtmiller B. Shaffer RE New respirator fit test panels representing the current US civilian workforce. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2007;4:647–659. doi: 10.1080/15459620701497538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]