Abstract

Background

Many outbreaks of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) have occurred in health care settings and involved health care workers (HCWs). We describe the occurrence of an outbreak among HCWs and attempt to characterize at-risk exposures to improve future infection control interventions.

Methods

This study included an index case and all HCW contacts. All contacts were screened for MERS-CoV using polymerase chain reaction.

Results

During the study period in 2015, the index case was a 30-year-old Filipino nurse who had a history of unprotected exposure to a MERS-CoV–positive case on May 15, 2015, and had multiple negative tests for MERS-CoV. Weeks later, she was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis and MERS-CoV infection. A total of 73 staff were quarantined for 14 days, and nasopharyngeal swabs were taken on days 2, 5, and 12 postexposure. Of those contacts, 3 (4%) were confirmed positive for MERS-CoV. An additional 18 staff were quarantined and had MERS-CoV swabs. A fourth case was confirmed positive on day 12. Subsequent contact investigations revealed a fourth-generation transmission. Only 7 (4.5%) of the total 153 contacts were positive for MERS-CoV.

Conclusions

The role of HCWs in MERS-CoV transmission is complex. Although most MERS-CoV–infected HCWs are asymptomatic or have mild disease, fatal infections can occur and HCWs can play a major role in propagating health care facility outbreaks. This investigation highlights the need to continuously review infection control guidance relating to the role of HCWs in MERS-CoV transmission in health care outbreaks, especially as it relates to the complex questions on definition of risky exposures, who to test, and the frequency of MERS-CoV testing; criteria for who to quarantine and for how long; and clearance and return to active duty criteria.

Key Words: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, MERS-CoV, Infection control, Outbreak

Since the emergence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in September 2012, the largest and most documented outbreaks to date have occurred in health care settings.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 As of June 26, 2017, there have been 2,029 cases, including a total of 704 deaths, reported to the World Health Organization.7 The recent outbreaks of MERS-CoV infection highlight the importance of the emergency departments in being the initial site of the spread of this virus.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 In addition, hemodialysis units were also highlighted as the focus of multiple documented and undocumented outbreaks in Al-Hasa and Taif, Saudi Arabia (SA).5, 13 From April 2014-November 2016, a total of 295 confirmed cases were admitted to Prince Mohamed Bin Abdulaziz Hospital (PMAH), Ministry of Health, Riyadh, SA. Of those cases, 98 (33%) were diagnosed at PMAH, whereas the rest were transferred to PMAH from other Riyadh hospitals, because it is the reference coronavirus center for the central region of SA. Here, we describe a detailed investigation of an outbreak of MERS-CoV among health care workers (HCWs) in a MERS-CoV referral hospital with key learning points to be highlighted.

Methods

We describe the transmission pattern and contact tracing of a MERS-CoV–infected HCW, resulting in an outbreak in PMAH in SA. All suspected HCWs were tested for MERS-COV using real-time polymerase chain reaction.14 The target upstream of MERS-CoV was upE and ORF1a.14

The first case who initiated the outbreak was designated as the index case with all her positive contacts designated as primary transmissions. As described previously, subsequent cases resulting from the first-generation cases were called second-generation transmission, and infected HCWs from those were designated as third-generation cases and so on.15

Results

Index case

The case was confirmed on August 12, 2015 (from the first screening swab), and the patient was a 30-year-old Filipino nurse who had a history of unprotected exposure to a MERS-CoV–positive case on May 15, 2015. She was normal weight (weight, 58 kg). At that time and as per hospital protocol, she was quarantined for 14 days.16 MERS-CoV swab was documented on days 2, 5, and 12 to be negative (May 17, 23, and 27). On June 26, she went on vacation to the Philippines. Two weeks after her arrival to the Philippines, she manifested symptoms of dry cough and shortness of breath. She self-medicated herself with amoxicillin with no significant improvement. On August 7, she came back to SA, and on August 10, she was seen at the employee health clinic for evaluation. Given her recent arrival from a nonendemic country, screening for MERS-CoV was not considered. On August 11, she was allowed to resume work despite being symptomatic with dry cough and shortness of breath. On August 12, she was admitted as a suspected tuberculosis vs MERS-CoV infection. On the following day, MERS-CoV test was positive (cycle threshold [Ct] values of upE gene = 35, and ORF1a gene = 34), and she also tested positive for tuberculosis.17

Contacts of the index case

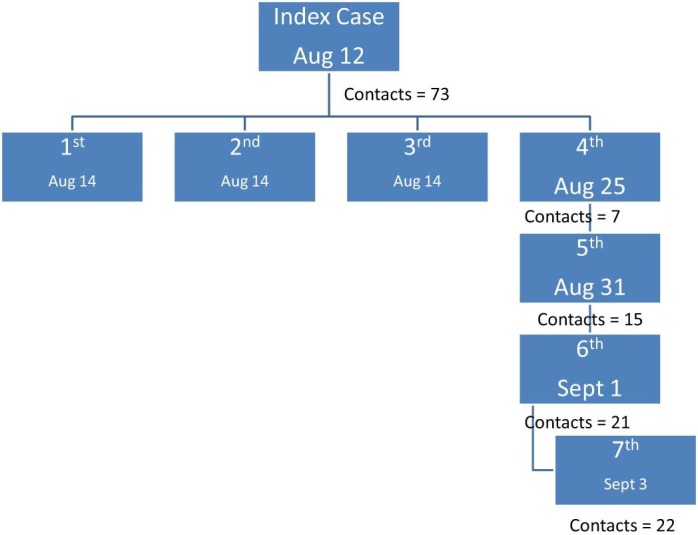

A comprehensive contact tracing was done, with a total of 73 staff quarantined for 14 days, and nasopharyngeal swabs taken on days 2, 5, and 12 postexposure. All quarantined HCW contacts had daily monitoring for fever and respiratory symptoms. Of those contacts, 3 (4%) were asymptomatic and confirmed positive for MERS-CoV by nasopharyngeal swabs (on first swab). An additional 18 new HCW contacts were quarantined and had MERS-CoV swabs as previously indicated. A fourth case was asymptomatic and tested negative on days 2 and 5 but was confirmed positive on day 12. Therefore, an additional 7 staff were quarantined (the fourth case's flatmates). A fifth staff member had fever and sore throat and was confirmed positive on first swab, and she came into contact with 15 additional staff. A sixth case had cough and sore throat and was confirmed positive on third swab. This sixth case had 21 additional contacts. Of those, 1 nurse was diagnosed with MERS-CoV (seventh case). The staff member was asymptomatic and was positive on the first swab. The seventh case had an additional 22 exposed staff, but none of them were positive (Fig 1 ). Therefore, only 7 (4.5%) of the total 153 contacts were positive for MERS-CoV.

Fig 1.

Graphical representation of the evolution of the outbreak.

All confirmed cases were nurses, and 2 of the 7 subsequent cases were thought to acquire the infection through an exposure within the housing compound. Detailed questioning on the significance of the contact with the positive cases revealed the following: 3 (43%) had contact <1.5 m, 4 (57%) had contact for <10 minutes, 3 (43%) had contact <1.5 m and >10 minutes, and the remaining had contact >1.5 m and <10 minutes (Table 1 ). Only the index case had an abnormal chest radiograph, and the laboratory evaluations of all positive cases are shown in Table 2 . All positive cases were positive on the first swab except for 2 who were positive on the second and third swabs. The mean time to negative swab was 4.8 days (range, 2-14 days).

Table 1.

Characteristics of confirmed MERS-CoV cases

| No. | Sex | Age (y) | Nationality | Symptoms | Days to negative | No. of contacts | Distance of contact (m) | Duration (min) | Department | LOS (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | F | 30 | Filipino | Cough, SOB | 2 | 79 | >1.5 | <10 | ICU | 32 |

| 1 | F | 37 | Filipino | Asymptomatic | 4 | 5 | <1.5 | >10 | ICU | 10 |

| 2 | F | 28 | Filipino | Asymptomatic | 4 | 7 | >1.5 | <10 | ICU | 10 |

| 3 | F | 28 | Indian | Asymptomatic | 4 | 6 | >1.5 | <10 | ICU | 12 |

| 4 | F | 26 | Filipino | Asymptomatic | 2 | 0 | <1.5 | >10 | ICU | 14 |

| 5 | F | 27 | Filipino | Fever, sore throat | 3 | 21 | >1.5 | <10 | Ward 24 | 16 |

| 6 | F | 29 | Filipino | Cough, sore throat | 14 | 15 | >1.5 | <10 | Ward 12 | 14 |

| 7 | M | 30 | Jordanian | Asymptomatic | 6 | 20 | <1.5 | >10 | Ward 24 | 12 |

F, female; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; M, male; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

Table 2.

Laboratory data of confirmed MERS-CoV cases

| No. | WBCS × 109/L | Hgb (g/L) | PLAT × 109/L | NEUT no. × 109/L | NEUT (%) | CK (100 U/L) | ALT (13 U/L) | AST (29 U/L) | Creatinine, (µmol/L) | Albumin (33 g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | 6.8 | 133 | 330 | 4.7 | 69 | NA | NA | NA | 61 | NA |

| 1 | 8 | 140 | 205 | 5.37 | 70 | 131 | 53 | 32 | 63.9 | 43 |

| 2 | 10 | 156 | 360 | NA | NA | NA | 14 | 20 | 67.1 | 49 |

| 3 | 12.2 | 119 | 206 | NA | NA | NA | 28 | 21 | 48.3 | 34 |

| 4 | 9 | 150 | 301 | 6.35 | 71 | NA | 23 | 32 | 50.2 | 45 |

| 5 | 17.7 | 146 | 166 | 15.3 | 86 | NA | 19 | 20 | 68.1 | 45 |

| 6 | 13 | 153 | 439 | 8.26 | 64 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 7 | 5.2 | 159 | 181 | 2.89 | 55 | NA | 20 | 21 | 71.8 | 44 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CK, creatinine kinase; Hgb, hemoglobin; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; NA, not applicable; NEUT, neutrophil; PLAT, platelet; SOB, shortness of breath; WBC, white blood cell count.

Discussion

In this outbreak investigation, we report 4 generations of transmission of MERS-CoV among HCWs. The transmission dynamics suggest that the transmission occurred within the setting of the hospital and in the housing environment. These findings highlight the importance of continued vigilance and detailed systematic screening of exposed HCWs whether they are symptomatic or not. Such an activity is very complex, and often it is difficult to elucidate the exact contact pattern between HCWs because of the extensive social interaction within the hospital and housing among different HCWs from different units. In addition, there are difficulties in relying on HCW's memory of exact contacts and infection control precautions taken during that contact.

The index case was initially identified as a contact of a MERS-CoV patient, and she had multiple swabs that were negative. She then went to the Philippines and started to have symptoms. Later, she was diagnosed with both MERS-CoV and pulmonary tuberculosis. Because the diagnosis of MERS had occurred many weeks after several negative MERS swabs, the exact source of the infection could not be determined. In the South Korean MERS-CoV outbreak, 5 patients with MERS-CoV had unclear infection sources.15 During the outbreak investigation, there were 4 spreaders (transmitting MERS to ≥1 individuals), and 1 possibly was a superspreader (transmitted the virus to 4 HCWs). In the South Korean outbreak, superspreader was arbitrarily defined as transmission of MERS-CoV to ≥5 cases.15 However, the exact definition of superspreader is not well established.18 The characteristics of the index case of an infectious disease outbreak potentially influence the transmission dynamics. These dynamics may also depend on the traits of the individuals with whom the index case interacts.

In this investigation, we found that all HCWs were nursing staff. In a previous outbreak study, none of the neurology unit workers contracted MERS-CoV, but 15 medical workers (11.7%) and 5 emergency department workers (4.1%) did contract MERS-CoV.19 The seropositivity of HCWs after a contact with MERS-CoV patients is variable. In this study, the polymerase chain reaction positivity rate was 4.5% among the exposed staff and no serologic testing was conducted. In a previous study of 1,169 HCWs, 15 were positive by polymerase chain reaction and 5 of 737 HCWs were positive by serology testing.20 In a second study from Thailand, none of 38 HCWs tested positive by serology.21 Using serology, none of 48 contacts were positive for MERS-CoV infection.22 In Korea, 36 (19.9%) of 181 confirmed MERS-CoV cases were HCWs.23

Although MERS-CoV among HCWs is usually asymptomatic or presents as a mild disease, fatal cases had been reported. Comparing MERS-CoV with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), most HCWs with SARS had symptomatic infection with an associated high case fatality rate. In one study, the case fatality rate was 7% among MERS-CoV–infected HCWs versus 12% in SARS among HCWs.24 The current study showed that most of the MERS-CoV–positive HCWs had asymptomatic or mild disease consistent with previous observations.25 What is surprising in our report was the fact that asymptomatic HCWs were able to transmit the virus to other HCWs despite being asymptomatic. This is in sharp contrast with the recent report from South Korea were none of 82 contacts of asymptomatic patients turned out to be positive.26 Although, the Ct value of the index case was high, the index case was able to infect an additional 4 cases. The relationship between the Ct value and transmission dynamics was not studied. However, a lower Ct of 31 for E gene was significantly lower than the median of 33 of survivors.27

Systematic thorough screening for MERS-CoV among contacts is needed for effective infection control of outbreaks. The current guidelines from the Saudi Ministry of Health do not advocate routine MERS-CoV testing of asymptomatic contacts and advocate the return to normal duty. However, the guidelines stress the need for testing of all the HCWs involved in high-risk unprotected exposure. High-risk exposure is defined as “contact with confirmed MERS-CoV case within 1.5 meters for > 10 minutes.” Those who are asymptomatic should have only 1 test.28 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that asymptomatic HCWs do not get routine MERS-CoV testing.29 During an outbreak investigation, HCWs with no symptoms were allowed to work with active monitoring and to be excluded from work if they develop MERS-CoV–like symptoms.30 The index case acquired MERS-CoV from the community, and she had concomitant tuberculosis with MERS-CoV. The coinfection might have contributed to increased infectiveness because of coughing and damaged lung tissue. The World Health Organization recommends testing all contacts in health care–associated outbreaks regardless of the development of symptoms.31 In addition, the World Health Organization recommends that asymptomatic HCWs with positive MERS-CoV by polymerase chain reaction should be isolated. The HCWs can return to work when 2 consecutive upper respiratory tract samples taken at least 24 hours apart are negative on real-time polymerase chain reaction.32 In this study, 43% had contact <1.5 m, 57% had contact <10 minutes, and 43% had high-risk contact (<1.5 m and >10 minutes contact).33 Therefore, of those positive, only 43% had high-risk exposure. Therefore, this definition alone may not be sufficient to exclude HCWs from testing. In a study of 9 HCWs who had contact within 0.91-1.83 meters of a MERS-CoV patient, only 1 of them was positive for MERS-CoV.34 In another study, all HCWs' contacts reported 100% compliance with personal protective equipment, and none were positive. In a study of 48 HCWs' contacts, none had serologic evidence of MERS-CoV infection.22 However, the largest screening of MERS-CoV among HCWs showed a positive rate of 1.1% among 1,695 HCWs.35 In the SARS era, asymptomatic patients were culture negative for SARS.36 Therefore, it is not clear if asymptomatic MERS-CoV patients behave similarly to SARS patients.

In conclusion, all HCWs in contact with confirmed MERS-CoV patients need to be quarantined for 14 days no matter how significant the contact is, if the full compliance with personal protective equipment cannot be assured with certainty. One and 2 samplings might not be adequate, and a third sampling is advisable prior to HCW clearance. The current detailed investigation identified positive contacts of asymptomatic MERS-CoV–positive HCWs, which highlights the possibility of being infectious even if symptoms are lacking, a question which has been debated by scientists for years.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report

References

- 1.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Assiri A., Memish Z.A. Middle East respiratory syndrome novel corona (MERS-CoV) infection: epidemiology and outcome update. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:991–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guery B., Poissy J., el Mansouf L., Séjourné C., Ettahar N., Lemaire X., et al. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet. 2013;381:2265–2272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omrani A.S., Matin M.A., Haddad Q., Al-Nakhli D., Memish Z.A., Albarrak A.M. A family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections related to a likely unrecognized asymptomatic or mild case. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e668–e672. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulland A. Novel coronavirus spreads to Tunisia. BMJ. 2013;346:f3372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assiri A., McGeer A., Perl T.M., Price C.S., Al Rabeeah A.A., Cummings D.A.T., et al. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Al-Rabiah F.A., Al-Hajjar S., Al-Barrak A., et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO; 2017. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Infection control measures for the prevention of MERS coronavirus transmission in healthcare settings. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14:281–283. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2016.1135053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hastings D.L., Tokars J.I., Abdel Aziz I.Z.A.M., Alkhaldi K.Z., Bensadek A.T., Alraddadi B.M., et al. Outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome at tertiary care hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:794–801. doi: 10.3201/eid2205.151797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balkhy H.H., Alenazi T.H., Alshamrani M.M., Baffoe-Bonnie H., Arabi Y., Hijazi R., et al. Description of a hospital outbreak of middle east respiratory syndrome in a large tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1147–1155. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balkhy H.H., Alenazi T.H., Alshamrani M.M., Baffoe-Bonnie H., Al-Abdely H.M., El-Saed A., et al. Notes from the field: nosocomial outbreak of middle east respiratory syndrome in a large tertiary care hospital–Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:163–164. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Saudi Arabia. 2016. http://www.who.int/csr/don/21-june-2016-mers-saudi-arabia/en/ Available from.

- 13.Assiri A., Abedi G.R., Bin Saeed A.A., Abdalla M.A., al-Masry M., Choudhry A.J., et al. Multifacility outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in Taif, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:32–40. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.151370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Hinedi K., Ghandour J., Khairalla H., Musleh S., Ujayli A., et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (MERS-CoV): a case-control study of hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:160–165. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S.W., Park J.W., Jung H.-D., Yang J.-S., Park Y.-S., Lee C., et al. Risk factors for transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection during the 2015 outbreak in South Korea. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:551–557. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghazal H., Ghazal S., Alharbi T., Al Nujaidi M., Memish Z. Middle-East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus: putting emergency departments in the spotlight. J Health Spec. 2017;5:51. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alfaraj S.H., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Altuwaijri T.A., Memish Z.A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and pulmonary tuberculosis coinfection: implications for infection control. Intervirology. 2017 doi: 10.1159/000477908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. Drivers of MERS-CoV transmission: what do we know? Expert Rev Respir Med. 2016;10:331–338. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2016.1150784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alraddadi B.M., Watson J.T., Almarashi A., Abedi G.R., Turkistani A., Sadran M., et al. Risk factors for primary Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus illness in humans, Saudi Arabia, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:49–55. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.151340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim C.-J., Choi W.S., Jung Y., Kiem S., Seol H.Y., Woo H.J., et al. Surveillance of the MERS coronavirus infection in healthcare workers after contact with confirmed MERS patients: incidence and risk factors of MERS-CoV seropositivity. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:880–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiboonchutikul S., Manosuthi W., Sangsajja C. Zero transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome: lessons learned from Thailand. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(Suppl):S167–S170. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall A.J., Tokars J.I., Badreddine S.A., Saad Z.B., Furukawa E., Al Masri M., et al. Health care worker contact with MERS patient, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:2148–2151. doi: 10.3201/eid2012.141211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim S.G. Healthcare workers infected with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and infection control. J Korean Med Assoc. 2015;58:647–654. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S., Chan T.-C., Chu Y.-T., Wu J.T.-S., Geng X., Zhao N., et al. Comparative epidemiology of human infections with Middle East respiratory syndrome and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses among healthcare personnel. PLoS ONE. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149988. 0149988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alraddadi B.M., Al-Salmi H.S., Jacobs-Slifka K., Slayton R.B., Estivariz C.F., Geller A.I., et al. Risk factors for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection among healthcare personnel. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1915–1920. doi: 10.3201/eid2211.160920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moon S., Son J.S. Infectivity of an asymptomatic patient with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:1457–1458. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feikin D.R., Alraddadi B., Qutub M., Shabouni O., Curns A., Oboho I.K., et al. Association of higher MERS-CoV virus load with severe disease and death, Saudi Arabia, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:2029–2035. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.150764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Command and Control Center Ministry of Health Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Scientific Advisory Board Infection prevention and control guidelines for the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Infection. 2017. http://www.moh.gov.sa/endepts/Infection/Documents/Guidelines-for-MERS-CoV.PDF 4th edition; Available from.

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for hospitalized patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/infection-prevention-control.html Available from.

- 30.Park G.E., Ko J.-H., Peck K.R., Lee J.Y., Lee J.Y., Cho S.Y., et al. Control of an outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in a tertiary hospital in Korea. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:87. doi: 10.7326/M15-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization Surveillance for human infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/177869/1/WHO_MERS_SUR_15.1_eng.pdf?ua=1 Available from.

- 32.World Health Organization Management of asymptomatic persons who are RT-PCR positive for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV. 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/180973/1/WHO_MERS_IPC_15.2_eng.pdf?ua=1 Available from.

- 33.Wiboonchutikul S., Manosuthi W., Likanonsakul S., Sangsajja C., Kongsanan P., Nitiyanontakij R., et al. Lack of transmission among healthcare workers in contact with a case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in Thailand. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:21. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0120-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim T., Jung J., Kim S.-M., Seo D.-W., Lee Y.S., Kim W.Y., et al. Transmission among healthcare worker contacts with a Middle East respiratory syndrome patient in a single Korean centre. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:e11–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Memish Z.A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Makhdoom H.Q., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Assiri A., Alhakeem R.F., et al. Screening for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in hospital patients and their healthcare worker and family contacts: a prospective descriptive study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:469–474. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan K.H., Poon L.L.L.M., Cheng V.C.C., Guan Y., Hung I.F.N., Kong J., et al. Detection of SARS coronavirus in patients with suspected SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:294–299. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]