Highlights

-

•

We detected an outbreak of nosocomial human rhinovirus C in our neonatal intensive care unit.

-

•

Although the outbreak only consisted of 2 cases, it emphasizes the importance of hand hygiene in a neonatal intensive care unit to prevent the spread of infectious diseases to a susceptible population.

-

•

Laboratory techniques, such as respiratory panel polymerase chain reaction, improve the efficiency of test results, allowing clinicians the ability to detect outbreaks and detect them earlier.

Key Words: Human rhinovirus C, Nosocomial infection, Neonatal intensive care unit

Abstract

Nosocomial respiratory infections cause significant morbidity and mortality, especially among the extremely susceptible neonatal population. Human rhinovirus C is a common viral respiratory illness that causes significant complications in children <2 years old. We describe a nosocomial outbreak of human rhinovirus C in a level II-III neonatal intensive care unit in an urban public safety net hospital.

Background

Respiratory syncytial virus and influenza are 2 common respiratory viruses that are well-known for nosocomial transmission; however, new rapid diagnostic respiratory tests have implicated other viruses, such as human rhinovirus (HRV), in severe respiratory infections.

HRV is divided into 3 distinct species: HRV species A, B, and C.1 HRV species C is associated with respiratory tract infections, severe asthma exacerbations in children, and apnea in infants.2 We describe a nosocomial outbreak of HRV species C in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). To our knowledge, there are only 2 previously published studies implicating HRV in a NICU respiratory infection outbreak.3, 4

Methods

Setting

This study took place in an urban public safety net hospital with a level II-III NICU. The NICU has 20 beds with 8 single occupancy rooms and 4 triple occupancy rooms. All visitors are screened by the patient's nurse for signs of illness and asked to leave if they are ill.

Outbreak detection and investigation

After 2 infants becoming ill with respiratory symptoms, respiratory viral testing and routine bacterial cultures were undertaken. Each patient's medical record was reviewed with attention to vital signs, examination findings, respiratory and ventilator support, white blood cell counts, radiographic studies, room location, and staff members, including nurses, respiratory therapists, and physicians.

Isolate testing

The FilmArray Respiratory Panel (Biofire Diagnostics, Salt Lake City, UT) was used for viral and bacterial detection. This multiplex polymerase chain reaction system is used to detect the presence of adenovirus, coronavirus, metapneumovirus, rhinovirus-enterovirus, influenza, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, Bordetella pertussis, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Both children's specimens tested positive for rhinovirus-enterovirus complex, and the samples were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for further confirmatory testing.

Results

Cases

Patient 1 was a 73-day-old boy who was born at 25 weeks, weighing 670 g, to a 38-year old mother via Cesarean section at an outside hospital and transferred to our facility on day of life 27 and hospital day (HD) 1. The patient's neonatal course was complicated by prenatal exposure to cocaine, maternal chorioamnionitis secondary to Escherichia coli, and lung disease. From HD 42-47, the patient's oxygen requirement increased to 100%; respiratory support changed from nasal cannula oxygenation to bilevel positive airway pressure. From HD 46-56, upper airway congestion was noted, and moderate to large respiratory secretions were suctioned. Neither fever nor leukocytosis was present.

Patient 2 was a 16-day-old boy born at our facility on HD 32 at 31 6/7 weeks, weighing 1,575 g. He was delivered via Cesarean section for nonreassuring biophysical profile. Secondary diagnoses included respiratory insufficiency, suspected bacteremia, and hyperbilirubinemia. On HD 45, the patient had desaturation episodes into the low 80s and large cloudy secretions suctioned from nose. On HD 46 and 47, the patient's oxygen requirement increased to 175 mL/min prior to the use of bilevel positive airway pressure. Chest radiograph revealed multifocal pulmonary opacities in the left lower lobe and right middle lobe. The patient did not have a fever or leukocytosis, and blood cultures were negative.

Investigation

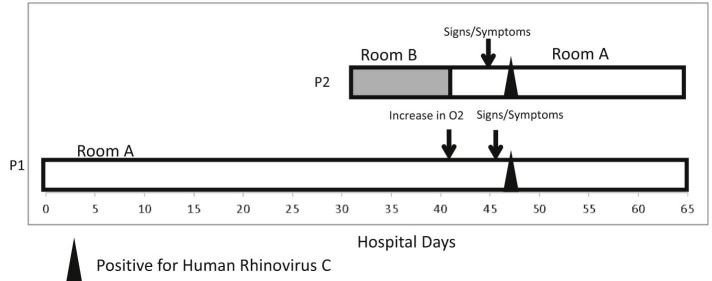

Patients 1 and 2 were in the NICU concurrently for 11 days and cared for by separate staff; then on HD 42, patient 2 was moved into patient 1's triple occupancy room (Fig 1 ). They were the only patients in this room during this time. This was the same day that patient 1's oxygen requirement increased, whereas patient 2 did not have any signs or symptoms of infection. On HD 45 and 46, patient 2 and patient 1 developed nasal congestion, respectively. On HD 47, both patients 1 and 2 tested positive for rhinovirus-enterovirus. During the 5 days they shared a room prior to positive HRV species C test, patient 1 was in an isolette, and patient 2 was in an open crib. They had 6 common nurses, with 3 caring for them on multiple days. They did not share any physicians or respiratory staff. None of the shared staff members called in ill in the 2 weeks before or after the respiratory outbreak, but it is unknown if any staff worked while having mild or moderate illness. Patient 1 had a family member visit, and patient 2 had 2 family members visit in the 5 days prior to HRV species C diagnosis, one of them being a young sibling; none of these family members were noted to be ill.

Fig 1.

Locations of case patients, days of positive human rhinovirus test, and signs symptoms of infection. Abbreviation: P, patient.

Discussion

This report describes 2 nosocomial cases of HRV species C. HRV species C is transmitted either person to person through contact (either direct or through a fomite) or through aerosolization.5, 6, 7

We suspect that HRV species C was from a single point source given the 2 infants became symptomatic on the same day through either staff members or common use patient items within the room. The most plausible explanation would be a shared health care worker who was ill, but not ill enough to call in sick. It is possible that a staff member was ill with HRV species C the week prior to patient care and was shedding virus after the symptoms resolved. Adults with symptomatic HRV can shed virus for at least a week after infection, but it can persist up to 2-3 weeks in some adults.8 Another possibility of transmission could have occurred from the young family member of patient 2. The sibling could have either had an asymptomatic infection or the family neglected to tell the staff that the child was feeling ill. Children <4 years old have had asymptomatic rates of infection range from 12%-32%.9, 10 Because patient 1 was in an isolette, this is a less likely scenario. Alternatively, HRV species C may have been spread through inanimate surfaces. HRV is able to survive for hours to days on environmental surfaces.11 However, there are very few items that are shared between 2 neonates in the NICU.

We report a series of nosocomial transmission of HRV species C in neonates. Although we cannot be certain, the timing of this cluster makes us suspect that a single health care worker exposed both infants. Both patients exhibited signs and symptoms within a day of each other and tested positive on the same day, making it most likely that they were exposed by a single source. Exposure by a symptomatic or asymptomatic family member is less likely because family members of infants did not directly interact with the other infant. An inanimate object was also unlikely because the infants were not mobile, and no other infants in the NICU were found to have HRV species C at that time.

In conclusion, we report a cluster of possible nosocomial HRV species C in a NICU. The detection of this outbreak likely was because of improved laboratory techniques, namely the multiplex polymerase chain reaction system. We suspect an increase in reports of nosocomial viral transmission. We hope that molecular technology will continue to advance so that we can determine clonality of viruses and trace exposure etiology and determine if concurrent cases are coincidence or from a common source.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

References

- 1.Palmenberg AC, Spiro D, Kuzmickas R, Wang S, Djikeng A, Rathe JA. Sequencing and analyses of all known human rhinovirus genomes reveal structure and evolution. Science. 2009;324:55–59. doi: 10.1126/science.1165557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gern JE. The ABCs of rhinoviruses, wheezing, and asthma. J Virol. 2010;84:7418–7426. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02290-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steiner M, Strassl R, Straub J, Bohm J, Popow-Kraupp T, Berger A. Nosocomial rhinovirus infection in preterm infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:1302–1304. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31826ff939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid AB, Anderson TL, Cooley L, Williamson J, McGregor AR. An outbreak of human rhinovirus species C infections in a neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:1096-5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31822938d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jennings LC, Dick EC. Transmission and control of rhinovirus colds. Eur J Epidemiol. 1987;3:327–335. doi: 10.1007/BF00145641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hendley JO, Gwaltney JM., Jr Mechanisms of transmission of rhinovirus infections. Epidemiol Rev. 1988;10:243–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel JD, Jackson M, Chiarello L, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/isolation2007.pdf Available from: Accessed December 21, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Winther B, Gwaltney JM, Jr, Mygind N, Turner RB, Hendley JO. Sites of rhinovirus recovery after point inoculation of the upper airway. JAMA. 1986;256:1763–1767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singleton RJ, Bulkow LR, Miernyk K, DeByle C, Pruitt L, Hummel KB. Viral respiratory infections in hospitalized and community control children in Alaska. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1282–1290. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwane MK, Prill MM, Lu X, Miller EK, Edwards KM, Hall CB. Human rhinovirus species associated with hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness in young US children. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1702–1710. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fendrick AM. Viral respiratory infections due to rhinoviruses: current knowledge, new developments. Am J Ther. 2003;10:193–202. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]