Abstract

Frequently touched surfaces of a university classroom that is cleaned daily contained viable human coronavirus 229E (CoV-229E). Tests of a CoV-229E laboratory strain under conditions that simulated the ambient light, temperature, and relative humidity conditions of the classroom revealed that some of the virus remained viable on various surfaces for 7 days, suggesting CoV-229E is relatively stable in the environment. Our findings reinforce the notion that contact transmission may be possible for this virus.

Key Words: Frequently touched environmental surfaces, Human coronavirus 229E

Symptomatic or asymptomatic individuals that harbor respiratory viruses release virus particles through expiration and respiratory maneuvers such as coughing and sneezing. Virus particles emitted by these persons are present in aerosols or are contained in droplets that settle or are manually deposited onto frequently touched surfaces. One route of human respiratory virus infection is through contact transmission, which occurs when virus-containing fomites or free viruses are transferred from an environmental surface to mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract.1, 2

In this study, we tested which viable (live) respiratory viruses might be isolated from high contact surfaces of a university classroom during the start of influenza season in November 2016.

Methods

High-touch environmental surfaces were sampled once a day, from November 12-26, 2016, in the same highly used classroom of a university in Florida. Samplings were performed between classroom sessions or on weekends, when students were not present in the classroom, typically between 6-7 PM. The classroom's high-touch surfaces were cleaned Monday through Friday between 6-7 AM with a commercial cleaning solution consisting of nonionic surfactant (alcohol ethoxylates) mixed with an anionic surfactant (sodium xylene sulfonate) by janitorial staff. Surfaces chosen for sampling in this study were (1) seat-backs made of hard polyvinylchloride, (2) laminate desktops, (3) a wooden podium, and (4) a stainless steel doorknob.

Swab samples were collected using flocked nylon swabs that were inserted into 1 mL of Universal Transport Medium (no. 360C; Copan Diagnostics, Murrieta, CA).3 Virus isolation was attempted in monolayers of 6 ATCC (Manassas, VA) cell lines: A549 (CCL-185), MDCK (NBL-2) (CCL-34), HeLa (CCL-2), LLC-MK2 (CCL-7), VERO E6 (CRL-1586), and MRC-5 (CCL-171).4 Replicate sets of cells were inoculated with 50 µL aliquots from the Universal Transport Medium tubes, with one set incubated at 33°C and the other at 37°C (some human respiratory viruses preferentially grow at 33°C, others at 37°C), and observed over 21 days for development of virus-specific cytopathic effects. Nucleic acids extracted from the spent cell growth media were subsequently analyzed using a GenMark multiplex PCR eSensor XT-8 Respiratory Viral Panel (GenMark Diagnostics, Carlsbad, CA) for virus identification. One human coronavirus 229E (CoV-229E) isolate was thereafter completely sequenced essentially as described by Farsani et al.5

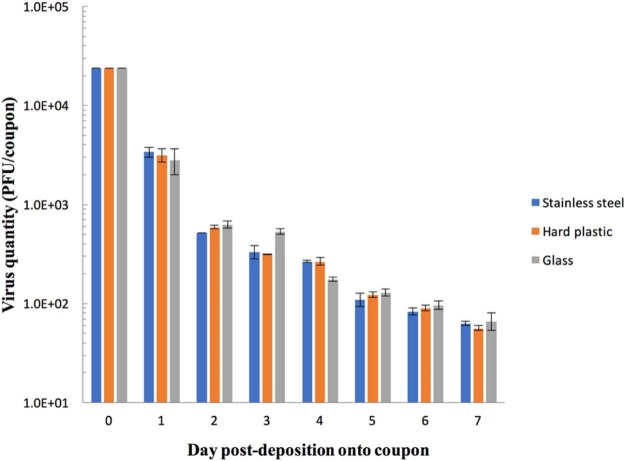

Separately, the stability of a well-studied CoV-229E strain (VR-740; ATCC) was assessed on 3 different hard surfaces held at 24°C and 50% relative humidity with fluorescent lights on for 14 h/d (simulating the university classroom ambient light, temperature, and humidity conditions). Briefly, 20 µL aliquots (3 replicates per day, over a 7-day testing period) containing 2 × 104 plaque forming units of virus were spotted and spread over the surface of sterile 1 cm2 hard plastic, glass, and stainless steel coupons. Virus survival was monitored, with viable counts of viruses extruded off the different surfaces determined by plaque assay.

Results

Six cell cultures inoculated with samples collected on 4 different days displayed cytopathic effects within 3-11 days postinoculation. Viral genomic RNA extracted from virions in spent culture media was identified as that of CoV-229E by the GenMark multiplex PCR eSensor XT-8 Respiratory Viral Panel. Desktops and the doorknob were the most commonly contaminated surfaces (Table 1 ). The complete genome sequence of Human coronavirus 229E/UF-1/2016 was determined from 1 isolate (GenBank: KY996417.1).

Table 1.

Development of virus-induced cytopathic effects in inoculated cell lines

| Sampling date | Surface tested | Day | Cell lines | Respiratory virus identified by eSensor XT-8 Respiratory Viral Panel | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | MRC-5 | VERO E6 | ||||

| November 12, 2016 | Desk top 1 | Saturday | — | — | — | |

| November 13, 2016 | Desk top 2 | Sunday | — | — | — | |

| November 14, 2016 | Desk top 3 | Monday | — | — | — | |

| November 18, 2016 | Desk top 4 | Friday | + | + | + | CoV-229E |

| November 19, 2016 | Doorknob | Saturday | — | — | — | |

| November 20, 2016 | Desk top 5 | Sunday | + | + | + | CoV-229E |

| November 22, 2016 | Podium | Tuesday | — | — | — | |

| November 22, 2016 | Desk top 6 | Tuesday | + | + | + | CoV-229E |

| November 22, 2016 | Doorknob | Tuesday | + | + | + | CoV-229E |

| November 22, 2016 | Chair back | Tuesday | — | — | — | |

| November 23, 2016 | Desk top 7 | Wednesday | + | + | + | CoV-229E |

| November 23, 2016 | Doorknob | Wednesday | + | + | + | CoV-229E |

| November 23, 2016 | Chair back | Wednesday | — | — | — | |

| November 24, 2016 | Desk top 8 | Thursday | — | — | — | |

| November 25, 2016 | Doorknob | Friday | — | — | — | |

| November 26, 2016 | Chair back | Friday | — | — | — | |

—, No cytopathic effects observed; +, cytopathic effects observed; CoV-229E, human coronavirus 229E.

After 7 days, there was an approximate reduction of the viable virus count of CoV-299E VR-740 by about 2.5 logs; however, a significant quantity of virus remained infectious (Fig 1 ).

Fig 1.

Survival of human coronavirus 229E on different hard surfaces over a 7-day observation period. Viable virus counts were determined by plaque assay and reported as PFU per coupon. PFU, plaque forming units.

Discussion

We isolated CoV-229E from high-touch surfaces in a university classroom. Others have reported detection of coronavirus genomic RNA on various surfaces in hospitals and dwellings.6, 7 Taken together, these findings seem counterintuitive because enveloped viruses are more susceptible to environmental stresses, such as radiation, temperature, and relative humidity, than nonenveloped viruses, mostly because of the lipidic nature of their envelopes.8 Our study of CoV-229E VR-740 survival indicates that the virus is not fully inactivated for at least 7 days after deposition on different environmental surfaces at ambient temperature (24°C) and relative humidity conditions (approximately 50%) typical of our university's classrooms. This is significant given that the minimum infective dose of respiratory viruses can be very low.9

Given that the frequently touched surfaces in the classroom were cleaned every morning, isolation of CoV-229E on several days during the sampling period suggests frequent redeposition of the virus on those surfaces or an ineffective daily cleaning regimen. Of all the surfaces tested in the classroom, isolation of infectious CoV-229E from the doorknob is probably of greatest significance because it is always used, and the knob was thoroughly swabbed at each sampling. From a public health perspective, a better choice might be brass instead of stainless steel doorknobs because brass has been reported to be deleterious for CoV-229E; however, quick inactivation on brass may not occur for other viruses.10 Alcohol ethoxylates, the principal component of the cleaning solution used on the surfaces of the classroom of this study, reduced genomic loads of common respiratory viruses on toys in day care nurseries. Although the effect on virus viability was not investigated in the later study, a decrease in genomic loads of adeno-, rhino-, and respiratory syncytial viruses was reported, but the load of coronavirus, the most prevalent virus group detected on toys, remained unchanged before and after the alcohol ethoxylate intervention.11

Although a new COV 229E strain was confirmed by sequencing of 1 isolate, and it is tempting to infer 1 person was the source, it is possible that the same virus strain was circulating among the students and that the viruses we detected over many days emanated from various persons. A broader study might include linking the virus to the person(s) shedding the virus. Also, further study on the effects of commonly used cleaning and disinfecting solutions on CoV-229E viability are warranted. Finally, air sampling studies would be an important adjunct; in our study, an inhalation risk was also likely caused by aerosols containing CoV 229E.

Conclusions

CoV-229E can remain infectious on environmental surfaces, and potentially poses a biohazard by contact transmission.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

References

- 1.Killingley B., Nguyen–Van–Tam J. Routes of influenza transmission. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7:42–51. doi: 10.1111/irv.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otter J.A., Yezli S., Salkeld J.A.G., French G.L. Evidence that contaminated surfaces contribute to the transmission of hospital pathogens and an overview of strategies to address contaminated surfaces in hospital settings. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:S6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Memish Z.A., Almasri M., Assirri A., Al-Shangiti A.M., Gray G.C., Lednicky J., et al. Environmental sampling for respiratory pathogens in Jeddah airport during the 2013 Hajj season. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:1266–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lednicky J.A., Loeb J.C. Detection and isolation of airborne influenza A H3N2 virus using a Sioutas Personal Cascade Impactor Sampler. Influenza Res Treat. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/656825. 656825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farsani S.M., Dijkman R., Jebbink M.F., Goossens H., Ieven M., Deijs M., et al. The first complete genome sequences of clinical isolates of human coronavirus 229E. Virus Genes. 2012;45:433–439. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0807-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boone S.A., Gerba C.P. Significance of fomites in the spread of respiratory and enteric viral disease. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1687–1696. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02051-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowell S.F., Simmerman J.M., Erdman D.D., Wu J.S., Chaovavanich A., Javadi M., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus on hospital surfaces. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:652–657. doi: 10.1086/422652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraise A.P., Lambert P.A., Maillard J. Blackwell Publishing; Malden (MA): 2004. Russell, Hugo and Ayliffe's Principles and Practices of Disinfection. Preservation, and Sterilization. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yezli S., Otter J.A. Minimum infective dose of the major human respiratory and enteric viruses transmitted through food and the environment. Food Environ Virol. 2011;3:1–30. doi: 10.1007/s12560-011-9056-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warnes S.L., Keevil C.W. Inactivation of norovirus on dry copper alloy surfaces. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e75017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibfelt T., Engelund E.H., Schultz A.C., Andersen L.P. Effect of cleaning and disinfection of toys on infectious diseases and micro-organisms in daycare nurseries. J Hosp Infect. 2015;89:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]