Highlights

-

•

Immunization with MERS spike protein nanoparticles induced only Th2-biased response.

-

•

Heterologous prime-boost immunization induced both Th1 and Th2-biased responses.

-

•

Our vaccination strategy showed the protective effect against MERS-CoV.

Abbreviations: MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; DPP4, Dipeptidyl peptidase 4; RBD, Receptor binding domain; ORF, Open reading frame; Ad5/MERS, Adenovirus 5 expressing MERS-CoV spike protein

Keywords: MERS-CoV, Vaccine, Adenovirus 5, Th1, Th2, Heterologous prime–boost

Abstract

The Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is a highly pathogenic and zoonotic virus with a fatality rate in humans of over 35%. Although several vaccine candidates have been developed, there is still no clinically available vaccine for MERS-CoV. In this study, we developed two types of MERS-CoV vaccines: a recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 encoding the MERS-CoV spike gene (Ad5/MERS) and spike protein nanoparticles formulated with aluminum (alum) adjuvant. Next, we tested a heterologous prime–boost vaccine strategy, which compared priming with Ad5/MERS and boosting with spike protein nanoparticles and vice versa, with homologous prime–boost vaccination comprising priming and boosting with either spike protein nanoparticles or Ad5/MERS. Although both types of vaccine could induce specific immunoglobulin G against MERS-CoV, neutralizing antibodies against MERS-CoV were induced only by heterologous prime–boost immunization and homologous immunization with spike protein nanoparticles. Interestingly, Th1 cell activation was induced by immunization schedules including Ad5/MERS, but not by those including only spike protein nanoparticles. Heterologous prime–boost vaccination regimens including Ad5/MERS elicited simultaneous Th1 and Th2 responses, but homologous prime–boost regimens did not. Thus, heterologous prime–boost may induce longer-lasting immune responses against MERS-CoV because of an appropriate balance of Th1/Th2 responses. However, both heterologous prime–boost and homologous spike protein nanoparticles vaccinations could provide protection from MERS-CoV challenge in mice. Our results demonstrate that heterologous immunization by priming with Ad5/MERS and boosting with spike protein nanoparticles could be an efficient prophylactic strategy against MERS-CoV infection.

1. Introduction

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is a zoonotic beta coronavirus that can infect several kinds of animals including humans, camels, and bats [1]. It is known to cause severe respiratory symptoms and to have a high mortality rate [1]. The key receptor for MERS-CoV infection, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4), is widely distributed on human endothelial and epithelial cells [2]. Except for cases in Korea in 2015, most infections with MERS-CoV (82%) have occurred in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The total number of laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infection is 2040 with 712 deaths related to MERS-CoV infection since September 2012. Thus, the human mortality rate of MERS-CoV infection is approximately 35% [3].

The genome of MERS-CoV is single-stranded RNA that encodes 10 proteins including two replicase polyproteins (open reading frames [ORF], 1ab and 1a), three structural proteins (E, N, and M), a surface glycoprotein (S, spike), which comprises S1 and S2, and five nonstructural proteins (ORF 3, 4a, 4b, and 5) [4]. The main viral protein is the spike protein, which binds to the cell surface receptor DPP4 during the viral entry stage via the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of spike subunit S1 [5]. Because the spike protein is the most immunogenic structural protein [6], [7], the final goal of most current studies of MERS-CoV vaccines is to elicit neutralizing antibodies against this specific MERS-CoV spike protein.

Although several approaches to developing a MERS-CoV vaccine have been reported, there is no clinically approved vaccine for MERS-CoV. Previous studies have investigated viral vector-based vaccines [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], subunit vaccines [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], and DNA vaccines [18], [19]. Of these, vaccination using viral vectors or DNA immunization successfully generated neutralizing antibodies and protected against infection [12]. However, safety concerns about DNA vaccines and their weak induction of neutralizing antibodies plus the possibility of reduced efficacy of viral vector vaccines because of preexisting immunity against the viral vectors induced by repeated immunization cannot be ignored. Although protein subunit vaccines can induce neutralizing antibody, they usually elicit a lower level of cellular immune response which has close association with rapid viral clearance when infection occurs. In addition, subunit vaccines could not induce enough immune responses in host, resulting in failure to make long-term memory of antigen [20].

Therefore, we used a heterologous prime–boost immunization strategy combining recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 delivering MERS-CoV spike protein gene (Ad5/MERS) and MERS spike protein nanoparticles, because both types of vaccine have been shown to be safe in human trials. The results of this study showed that this heterologous prime–boost immunization strategy induced good humoral and cellular immune responses including neutralizing antibodies and activation of Th1 cells against MERS-CoV, and could protect mice against MERS-CoV infection. Therefore, this combined immunization with recombinant Ad5/MERS and spike protein nanoparticles may avoid the hurdles of preexisting antibody induced by repeated viral vector immunization and weak Th1 cell responses induced by protein subunit immunization.

2. Methods

2.1. Supporting information (SI) for Materials and methods

See the Supplemental data for Materials and Methods for details regarding Cell, Virus preparation and titration, MERS spike protein nanoparticles, SDS-PAGE and Immunoblot analysis, Recombinant Ad5, Electron microscopy, Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), Plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT), MERS-CoV infection, and Statistical analysis.

2.2. Mice

Six-week-old female specific-pathogen-free BALB/c mice were purchased from Dae Han Bio Link Co., Ltd., (Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea). Mouse experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant ethical guidelines and regulations established by the Korean Association for Laboratory Animals [21]. All mice were housed in specific-pathogen-free conditions with a standard light cycle (12 h light/dark) and maintained according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Sungsim Campus, Catholic University of Korea. All mice were fed a normal fat (5%) diet (Harlan Laboratories, Livermore, CA, USA) and sterile water. Mice were randomly allocated to groups of six and immunized three times as indicated (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Detailed information about each vaccination protocol.

| Group | Prime (1st vaccination) | 1st Boost (2nd vaccination) | 2nd Boost (3rd vaccination) | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | PBS | PBS | PBS | Control groups |

| Ad5/GFP | Ad/GFP | Ad/GFP | Ad/GFP | |

| Spike protein | Spike protein | Spike protein | Spike protein | Homologous prime–boost groups |

| Ad5/MERS | Ad5/MERS | Ad5/MERS | Ad5/MERS | |

| Ad5/MERS–spike protein | Ad5/MERS | Spike protein | Spike protein | Heterologous prime–boost groups |

| Spike protein–Ad5/MERS | Spike protein | Ad5/MERS | Ad5/MERS |

2.3. Virus preparation and titration

MERS-CoV was provided by the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (National Control Number 1-001-MER-IS-2015001). All experimental procedures were performed in the Biosafety Level 3 facility of the Korea Zoonosis Research Institute at Chonbuk National University. The virus was passaged and titered on Vero E6 cells.

2.4. MERS spike protein nanoparticles

Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 insect cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in Insect-XPRESSTM medium. The MERS-CoV spike protein sequence was referred from NCBI reference sequence (Genbank accession No. AGN70962), and the nucleotide sequence was codon optimized for optimal expression in insect cells. Full length spike gene was cloned into pBacPAK8 baculovirus transfer vector. MERS-CoV spike proteins were produced in Sf9 cells infected with recombinant baculovirus. Spike proteins were purified using a combination of anion exchange and glucose affinity chromatography.

2.5. Recombinant adenovirus 5 expressing MERS spike protein gene (Ad5/MERS) and human DPP4 (Ad5/hDPP4)

Recombinant adenoviruses encoding the MERS spike protein and human DPP4 were purchased from Sirion Biotech (London, UK). The detailed production protocol is in Supporting Information (SI).

2.6. Vaccination and serum collection

Groups of mice were immunized using heterologous (different vaccine candidates for priming and boosting) or homologous (the same vaccine candidate for priming and boosting) prime–boost immunization. The detailed immunization schedules and grouping are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2A.

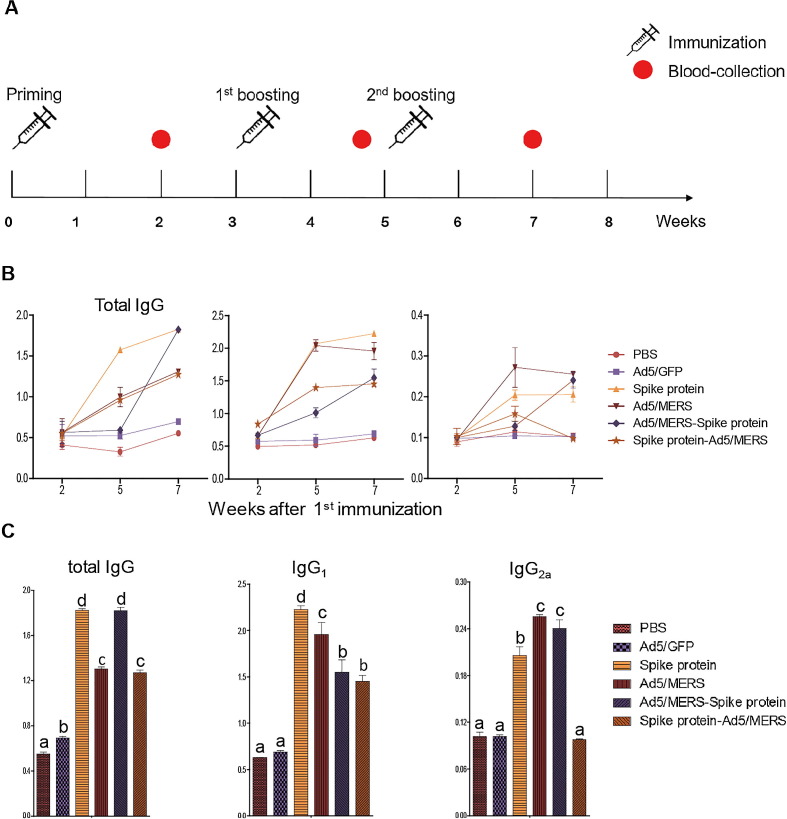

Fig. 2.

Immunogenicity of homologous and heterologous vaccination strategies. (A) Schedule for heterologous or homologous vaccination and bleeding. Mice were immunized three times intramuscularly using 5 μg MERS spike protein nanoparticles and 1 × 109 IU Ad5/MERS or Ad5/GFP. Serum was collected 2 weeks after each immunization. Seven weeks after the first immunization, mice were sacrificed and used for analysis. (B) Mean titer of MERS-specific serum antibody. Total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a subsets were measured by ELISA 2 weeks after the last immunization. (C) Antibody titer of sera collected 7 weeks after the first vaccination (2 weeks after the second booster). The graph shows mean optical density (OD) ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were assessed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test for comparing multiple treatments; the significance of differences between groups are indicated by letters. Each group had n = 6 mice. All within-group samples were pooled and independently analyzed three times.

2.7. Enzyme-linked immunospot (EliSpot) assay

Mouse splenocytes were collected and isolated after mice were euthanized. Then, 3 × 106 splenocytes were seeded into wells of an EliSpot plate for detection of IFN-γ secreting T cells. To stimulate the splenocytes, 1.6 μg/well of MERS-CoV spike-specific peptide (S291, KYYSIIPHSI) [22] was added to the culture medium to restimulate the splenocytes and then cultured for 1 day. After 2 days, cells were stained to detect spots positive for cytokines analyzed.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses of the data were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.01; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Between-group differences were tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

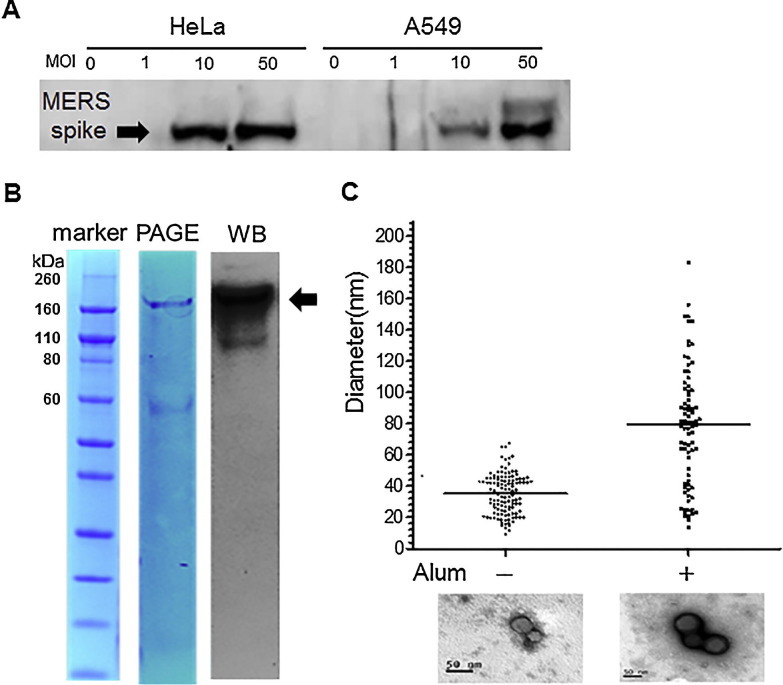

3.1. Construction and expression of Ad5/MERS and spike protein nanoparticles

Adenovirus serotype 5 for delivery of the full-length MERS spike protein gene (Ad5/MERS) was produced and tested for gene transduction efficiency in cell lines. HeLa cells and A549 cells were infected with 1, 10, or 50 MOI of Ad5/MERS. At 24 h after infection, lysates of each cell line were harvested and immunoblotted with a polyclonal anti-MERS spike protein antibody, produced in rats immunized with MERS spike protein nanoparticles formulated with alum. The lysates of HeLa and A549 cell lines infected with Ad5/MERS at over 10 MOI clearly contained the approximately 140-kDa MERS spike protein (Fig. 1 A). These data confirmed that Ad5/MERS-infected cells can express the MERS spike protein. In addition, full-length MERS spike protein containing the transmembrane domain (amino acids 1297–1320) was produced in an insect cell culture system (Fig. 1B) and was confirmed the expression by Western blot (Fig. 1B). Electron micrographs of these spike protein nanoparticles formulated with alum showed that their mean diameter was around 80 nm, whereas that of spike protein nanoparticles not formulated with alum is around 35 nm (Fig. 1C). Alum-formulated MERS spike protein nanoparticles displayed a broader distribution of diameters than those not formulated with alum.

Fig. 1.

Expression of MERS spike protein by Ad5/MERS and electron microscopy of aluminum (alum)-formulated MERS spike protein nanoparticles. (A) Expression of Ad5/MERS in HeLa and A549 cells was confirmed using anti-MERS spike protein antibody. MOI: multiplicity of infection. (B) Purified MERS spike protein nanoparticle (indicated by arrow) was stained by Coomassive blue after sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (middle) and was detected by Western blotting (WB) (right). (C) The mean diameter of spike protein nanoparticles formulated with or without alum was compared from the micrograph images. The bars indicate the mean size. Electron microscope images of spike protein nanoparticles are under the graph. The black bar in images indicates 50 nm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. Immunization with Ad5/MERS and spike protein nanoparticles induces MERS spike protein-specific antibodies in mice

We immunized mice three times with Ad5/MERS and spike protein nanoparticles. The details of the combinations used for heterologous or homologous prime–boost immunization is indicated in Table 1. The immunization and bleeding schedules are shown in Fig. 2 A. The sera from immunized mice were collected and pooled at weeks 2, 5, and 7 after the first vaccination (priming) to analyze the MERS spike protein-specific antibodies by ELISA. At 7 weeks after the first immunization (2 weeks after the second booster), mice were sacrificed. At 2 weeks after the first vaccination, spike protein-specific total IgG could not be detected (Fig. 2B). However, at 5 weeks after the first vaccination (2 weeks after the first booster), spike protein-specific total IgG was increased in most groups except the Ad5/MERS–spike protein group. Finally, at 7 weeks after the first vaccination (2 weeks after the second booster), all vaccinated groups showed induction of MERS spike protein-specific antibodies, whereas the control PBS and Ad5/GFP groups did not show any induction of MERS-specific antibodies (Fig. 2B and 2C). Both the spike protein nanoparticles and Ad5/MERS–spike protein groups showed higher antibody titers compared with the Ad5/MERS group and the spike protein–Ad5/MERS group (Fig. 2C).

However, IgG1 and IgG2a showed different patterns of induction compared with total IgG (Fig. 2B and 2C). In general, IgG1 represents the Th2 response, which is more associated with humoral immune responses, and IgG2a represents the Th1 response, which is more associated with cellular immune responses [23]. For IgG1, the titers in the homologous prime–boost groups (spike protein nanoparticles or Ad5/MERS) were about 50% and 30% higher than those of the heterologous prime–boost groups each (Ad5/MERS–spike protein and spike protein–Ad5/MERS) at 7 weeks after the first vaccination (2 weeks after the second booster) (Fig. 2C). For IgG2a, the Ad5/MERS and Ad5/MERS–spike protein groups showed higher titers than the spike protein group. However, the spike protein–Ad5/MERS group did not show any induction of IgG2a at 7 weeks after the first vaccination (2 weeks after the second booster), although it showed induction of total IgG and IgG1 (Fig. 2B and 2C).

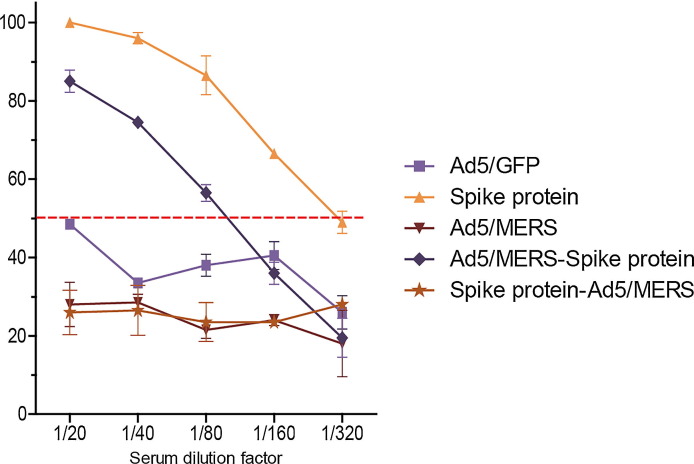

3.3. Immunization of mice with homologous spike protein nanoparticles and heterologous Ad5/MERS–spike protein induces neutralizing antibodies against MERS-CoV

Seven weeks after the first vaccination (2 weeks after the second booster), we collected mouse sera to evaluate the presence of neutralizing antibodies against MERS-CoV. Homologous spike protein nanoparticles and heterologous Ad5/MERS–spike protein immunized groups showed 50% of reduction in MERS-CoV when serum of each group was diluted at1:160 and 1:80 (Fig. 3 ). Although homologous Ad5/MERS and heterologous spike protein–Ad5/MERS immunization could induce total IgG against MERS spike protein (Fig. 2B and 2C), these groups had no detectable neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Titers of neutralizing serum antibody against MERS-CoV in immunized mice assessed by plaque reduction neutralizing assay. The rate of virus reduction for each group was calculated by comparison with the number of plaques in the PBS group. Equal volumes of sera from all mice in each group were pooled and serially diluted from 1/20 to 1/320. The Korean strain of MERS-CoV was used to assess the neutralizing activity. The red dotted line indicates a 50% reduction in virus. The mean reduction ± standard deviations are shown. Each group had n = 6 mice. All within-group samples were pooled and independently analyzed two times. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

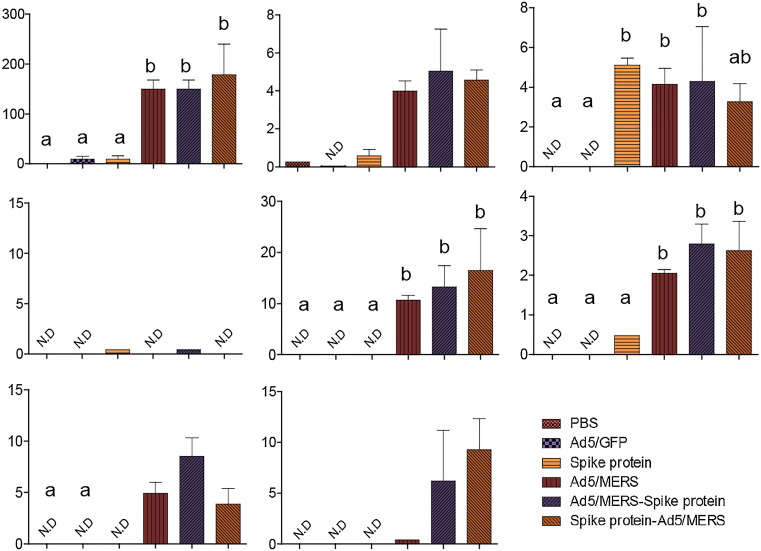

3.4. Homologous Ad5/MERS, heterologous Ad5/MERS–spike protein and heterologous spike protein–Ad5/MERS immunization induces IFN-γ-secreting T cells against MERS-CoV in mice

To analyze MERS spike protein-specific T cell activation, we used an EliSpot assay. First, we stimulated splenocytes cultured from immunized mice with a CD8+ T cell-specific peptide (S291, KYYSIIPHSI) [22] from MERS spike protein. Interestingly, groups immunized with regimens including Ad5/MERS (homologous Ad5/MERS group and heterologous groups including Ad5/MERS–spike protein and spike protein–Ad5/MERS) showed three times higher levels of IFN-γ-secreting T cells than the homologous spike protein nanoparticles immunized group (Fig. 4 ). Although the homologous spike protein group showed a slight increase in IFN-γ-secreting T cells compared with the PBS group, this increase was not as significant as those in Ad5/MERS-immunized groups (Fig. 4). Regardless of the number of immunizations with Ad5/MERS, all groups including Ad5/MERS immunization clearly showed the induction of IFN-γ-secreting T cells (Th1 cells) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Induction of MERS-specific Th1 immune responses. Mice from the immunized groups were sacrificed to analyze IFN-γ-secreting T cells. For this, 3 × 106 splenocytes were seeded and treated with S291 peptide. The number of stained cells were calculated using the AID iSpot Fluorescent EliSpot Reader System of AID GmbH (Strassberg, Germany). Mean optical density ± standard deviations are shown. Significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test for comparing multiple treatments, and significant differences between groups are indicated by letters. SFU: spot-forming unit. Each group had n = 6 mice. All within-group samples were pooled and independently analyzed three times.

3.5. Homologous Ad5/MERS and heterologous Ad5/MERS–spike protein or spike protein–Ad5/MERS immunization induces cytokine production by splenocytes stimulated with specific Th1 peptide

To investigate T cell responses further, we performed ELISA on splenocyte culture supernatants after stimulation with CD8+ T cell-specific peptide to measure the levels of various cytokines. Splenocytes from homologous Ad5/MERS and heterologous Ad5/MERS–spike protein- or spike protein–Ad5/MERS-immunized mice showed the induction of IL-2, IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-4, IL-5, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IL-10, with some exceptions in the homologous spike protein group with respect to the induction of TNF-α (Fig. 5 ). These data are generally consistent with those from the EliSpot analysis (Fig. 4).

Fig. 5.

Induction of cytokines after MERS-specific T cell peptide treatment of splenocytes from immunized mice. Cytokine levels (pg/mL) in culture supernatants of splenocytes were measured. Three days after MERS-CoV-specific peptide treatment, supernatants were diluted threefold and analyzed by multiplex cytokine ELISA. Mean optical density ± standard deviations are shown. Significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test for comparing multiple treatments, and significant differences between groups are indicated by letters. Each group had n = 6 mice. All within-group samples were pooled and independently analyzed three times.

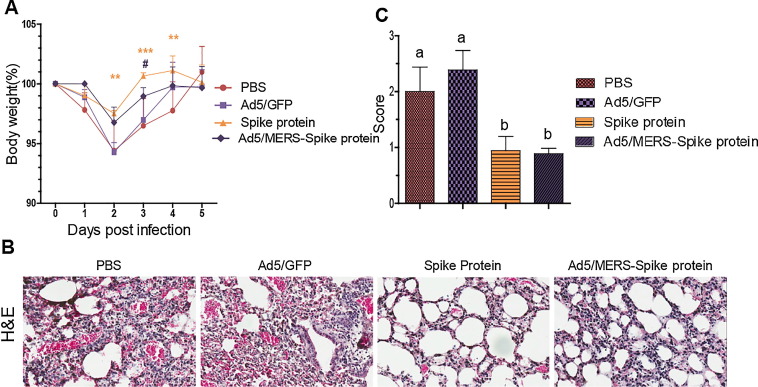

3.6. Homologous spike protein nanoparticles and heterologous Ad5/MERS–spike protein vaccination protects mice from MERS-CoV challenge

We selected two vaccination groups to test the protective effect of the vaccines against MERS-CoV challenge: the homologous spike protein group and the heterologous Ad5/MERS–spike protein group. The immunization schedules were as shown in Fig. 2A. The immunized mice were intranasally infected with 2 × 105 PFU live MERS-CoV 5 days after inoculation with 1.0 × 1010 IU of Ad5/hDPP4, which generates expression of hDPP4, the MERS-CoV receptor. After MERS-CoV infection, the control PBS and Ad5/GFP groups lost weight to about 94% of their starting weight. However, the vaccinated groups showed significantly less weight loss (to about 98% of their starting weight; p < 0.05) (Fig. 6 A). We compared the histopathology of homologous- or heterologous-vaccinated mice (spike protein nanoparticles or Ad5/MERS–spike protein) with that in nonvaccinated controls (PBS and Ad5/GFP). Lungs were collected 5 days after MERS-CoV infection. Although the mice began to regain weight at 3 days after infection, the severity of the lesions in their lungs was clear. PBS and Ad5/GFP groups showed the most severe lesions (Fig. 6B and 6C). Lung histology sections were examined by three blinded observers (Fig. 6C) and scored (from 0 to 3 points) based on the degree of inflammatory cell infiltration observed on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections (Fig. 6B). The spike protein and the Ad5/MERS–spike protein groups showed significantly milder pathology with MERS-CoV infection (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Protection of immunized mice from MERS-CoV challenge. Heterologous or homologous vaccination with spike protein nanoparticles and Ad5/MERS protected mice from MERS-CoV infection. (A) For 5 days after challenge, mice were weighed daily to determine the percentage increase or decrease in weight caused by viral infection. Mean changes in body weight ± standard deviation are shown. Asterisks indicate the significance of differences between the PBS group and the spike protein group. **p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001. Hashes indicate the significance of differences between the PBS group and the Ad5/MERS–spike protein group. #p < 0.05. (B) Histopathological examination of homologously or heterologously vaccinated mice (spike protein nanoparticles or Ad5/MERS–spike protein) and nonvaccinated controls (PBS and Ad5/GFP). Lungs were collected 5 days postinfection. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of lung were examined and scored by blinded observers (n = 3). Score 0: absence of lesions. Score 1: small or occasional subpleural foci. Score 2: thickened intraalveolar septa and subpleural fibrotic foci. Score 3: thickened continuous subpleural fibrous foci and intraalveolar septa [40]. Each group had n = 5 mice.

4. Discussion

Although the first MERS-CoV outbreak occurred in 2012, there is still no commercially licensed MERS-CoV vaccine for human use. Therefore, there has been much research on how to present effectively the main target antigen, spike protein. Previous studies have reported the effectiveness of DNA vaccines containing the spike protein gene [18], [19], spike protein itself [13], [17], RBD subunit vaccines [14], [15], [16], and viral vectors including modified vaccinia virus Ankara and adenovirus [8], [9], [10], [11], [12] for immunization of mice or nonhuman primates. Subunit vaccines, such as spike protein and RBD protein, induced neutralizing antibody against MERS-CoV, indicating the induction of a humoral immune response, and the DNA vaccine triggered the activation of cytotoxic T cells, indicating the induction of a cellular immune response. However, subunit vaccines usually induce weak cellular immune and Th1 cell responses, whereas DNA vaccines induce weak humoral immune and Th2 cell responses [20], [23], [24].

In this study, although Ad5/MERS induced spike protein-specific antibodies, these antibodies showed weak neutralizing activity. In contrast, Ad5/MERS induced MERS spike protein-specific IFN-γ-secreting T cells, which indicated the activation of Th1 cells. Moreover, the levels of effector cytokines including TNF-α, IL-2, GM-CSF, and IFN-γ that were produced after stimulation of cultured splenocytes with CD8+ T cell-specific peptide were higher in the Ad5/MERS-immunized groups. These cytokines are associated with both Th1 and Th2 immune responses. Therefore, the cytokine ELISA data indicate that Ad5/MERS immunization triggered activation of both Th1 and Th2 responses against MERS spike protein.

However, although the Ad5 vector has some advantages for use in development of vaccines, such as the induction of cellular immune responses and easy production [25], previous studies have reported that repeated injections of recombinant Ad5 reduced the presentation of the targeted antigen to antigen-presenting cells because of the presence of preexisting antibody against Ad5, and that this preexisting antibody, which was induced by the first (priming) vaccination, prevented further immune responses. This could be because of the low titers of neutralizing antibody induced by Ad5/MERS [26], [27]. To overcome this problem of preexisting antibody, several approaches have been developed [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]. One approach was to increase the dose of viral vector, but high-dose injection increased its cytotoxicity. Another approach was to change the surface antigen of the adenovirus vector used for booster immunizations to a rare serotype to evade the preexisting antibody [28], [29], [30], [31]. However, the concern with this strategy is the difficulty of mass production of two types of recombinant viruses, although packaging of the adenoviral vector with polymer [32], [33] and/or administration of adenovirus through other routes, such as mucosal or nasal inoculation, may circumvent this problem [34], [35]. Furthermore, these methods are dependent on the experimental conditions or the researcher’s skill. Therefore, to overcome this disadvantage but to take advantage of a viral vector vaccine, in this study we used a heterologous prime–boost vaccination strategy, in which Ad5/MERS was used for the first (priming) vaccination to activate the cellular immune response and then MERS spike protein nanoparticles was used for the second and third (first and second booster) vaccinations to activate the humoral immune response. As shown in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, this strategy induced both specific neutralizing antibody and Th1 cells against MERS spike protein, indicating that it could effectively trigger a cellular immune response by priming with Ad5/MERS and bypass the limitations of viral vectors by boosting with MERS spike protein nanoparticles.

A recent study analyzing patients who survived MERS virus infection demonstrated that survival depended on induction of both a cell-mediated immune response and neutralizing antibody [36]. The analysis showed a correlation between the severity of symptoms, the activation of T cells extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and the intensity of the antibody response. According to these data, patients with stronger activation of a MERS-specific CD8+ T cell response showed faster viral clearance and had relatively shorter exposure to the virus. In this regard, adenovirus vaccines, which are known to increase cellular immune responses via activation of CD8+ T cells [26], [37], [38], [39], may be strategic candidates for a MERS vaccine. The results shown in Fig. 6 indicate that both the Ad5/MERS–spike protein group and the spike protein group were protected against MERS-CoV challenge, as indicated by smaller body weight loss and less severe lung pathology after MERS-CoV infection. However, the spike protein group did not induce a Th1 immune response, but rather a Th2 immune response including induction of neutralizing antibody. This imbalance of Th1/Th2 responses suggests that immunization with spike protein nanoparticles alone may provide short-term protection against virus infection but not long-term maintenance of a protective immune response.

Previously, formalin-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine induced severe vaccine-enhanced respiratory disease (VERD) after natural RSV infection [41]. Therefore, our safety concern is that VERD, even during a long interval between vaccination and natural infection, may increase MERS-CoV because it is another respiratory virus [1]. It has also been shown that the induction of allergic and biased Th2 immune responses and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the airways and lungs are the main characteristics of VERD in RSV-inactivated vaccines [42], [43]. Our heterologous prime-boost immunization strategy with Ad5/MERS and spike protein nanoparticle clearly showed a balanced induction of Th1 and Th2 immune responses. Therefore, this vaccine strategy may be safe. However, it requires more detailed study.

Therefore, the heterologous vaccination strategy used in this study (Ad5/MERS prime and spike protein nanoparticles boost) is the method that would be most feasibly applied in the clinic, because it effectively uses the advantages of both a viral vector vaccine and a protein vaccine, concurrently inducing both Th1 and Th2 immune responses to induce protective immunity against MERS-CoV.

Funding information

This work was supported by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI15C2955), a grant (16172MFDS268) from Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2016–2017, and Basic Science Research Program through the NRF funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2015M3A9B5030157).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.082.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

References

- 1.Chan J.F.W., Lau S.K.P., To K.K.W., Cheng V.C.C., Woo P.C.Y., Yuen K.Y. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic betacoronavirus causing SARS-like disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(2):465–522. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyerholz D.K., Lambertz A.M., McCray P.B., Jr. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 distribution in the human respiratory tract. Am J Pathol. 2016;186(1):78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus [MERS-CoV]; 2016. <http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/> [accessed 20 August 2017].

- 4.Zumla A., Chan J.F.W., Azhar E.I., Hui D.S.C., Yuen K.Y. Coronaviruses—drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:327–347. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang N., Shi X., Jiang L., Zhang S., Wang D., Tong P. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res. 2013;23(8):986–993. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman C.M., Liu Y.V., Mu H., Taylor J.K., Massare M., Flyer D.C. Purified coronavirus spike protein nanoparticles induce coronavirus neutralizing antibodies in mice. Vaccine. 2014;32:3169–3174. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Q., Wong G., Lu G., Yan J., Gao G.F. MERS-CoV spike protein: targets for vaccines and therapeutics. Antiviral Res. 2016;133:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song F., Fux R., Provacia L.B., Volz A., Eickmann M., Becker S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein delivered by modified vaccinia virus Ankara efficiently induces virus-neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2013;87:11950–11954. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01672-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim E., Okada K., Kenniston T., Raj V.S., AlHajri M.M., Farag E.A. Immunogenicity of an adenoviral-based Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine in BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 2014;32:5975–5982. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo X., Deng Y., Chen H., Lan J., Wang W., Zou X. Systemic and mucosal immunity in mice elicited by a single immunization with human adenovirus type 5 or 41 vector-based vaccines carrying the spike protein of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Immunology. 2015;145:476–484. doi: 10.1111/imm.12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volz A., Kupke A., Song F., Jany S., Fux R., Shams-Eldin H. Protective efficacy of recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara delivering Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein. J Virol. 2015;89(16):8651–8656. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00614-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alharbi N.K., Padron-Regalado E., Thompson C.P., Kupke A., Wells D., Sloan M.A. ChAdOx1 and MVA based vaccine candidates against MERS-CoV elicit neutralising antibodies and cellular immune responses in mice. Vaccine. 2017;35:3780–3788. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du L., Kou Z., Ma C., Tao X., Wang L., Zhao G. A truncated receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV spike protein potently inhibits MERS-CoV infection and induces strong neutralizing antibody responses: implication for developing therapeutics and vaccines. PLos ONE. 2013;8:e81587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma C, Li Y, Wang L, Zhao G, Tao X, Tseng CT, et al. Intranasal vaccination with recombinant receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV spike protein induces much stronger local mucosal immune responses than subcutaneous immunization: implication for designing novel mucosal MERS vaccines. Vaccine 2014; 32(18):2100–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Tang J., Zhang N., Tao X., Zhao G., Guo Y., Tseng C.T. Optimization of antigen dose for a receptor-binding domain-based subunit vaccine against MERS coronavirus. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:1244–1250. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1021527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang N., Tang J., Lu L., Jiang S., Du L. Receptor-binding domain-based subunit vaccines against MERS-CoV. Virus Res. 2015;202:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coleman C.M., Venkataraman T., Liu Y.V., Glenn G.M., Smith G.E., Flyer D.C. MERS-CoV spike nanoparticles protect mice from MERS-CoV infection. Vaccine. 2017;35(12):1586–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muthumani K, Falzarano D, Reuschel EL, Tingey C, Flingai S, Villarreal DO, et al. A synthetic consensus anti-spike protein DNA vaccine induces protective immunity against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in nonhuman primates. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7(301):301ra132. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac7462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Wang L., Shi W., Joyce M.G., Modjarrad K., Zhang Y., Leung K. Evaluation of candidate vaccine approaches for MERS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7712. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naz R.K., Dabir P. Peptide vaccines against cancer, infectious diseases, and conception. Front Biosci. 2006;12:1833–1844. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2014.912134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho A., Seok S.H. Ethical guidelines for use of experimental animals in biomedical research. J Bacteriol Virol. 2013;43:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao J., Li K., Wohlford-Lenane C., Agnihothram S.S., Fett C., Zhao J. Rapid generation of a mouse model for Middle East respiratory syndrome. PNAS. 2014;111(13):4970–4975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323279111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh V.K., Mehrotra S., Agarwal S.S. The paradigm of Thl and Th2 cytokines. Immunol Res. 1999;20(3):147–161. doi: 10.1007/BF02786470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang R., Doolan D.L., Le T.P., Hedstrom R.C., Coonan K.M., Charoenvit Y. Induction of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in humans by a malaria DNA vaccine. Science. 1998;282(5388):476–480. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tatsis N., Fitzgerald J.C., Reyes-Sandoval A., Harris-McCoy K.C., Hensley S.E., Zhou D. Adenoviral vectors persist in vivo and maintain activated CD8+ T cells: implications for their use as vaccines. Blood. 2007;110:1916–1923. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-062117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindsay R.W., Darrah P.A., Quinn K.M., Wille-Reece U., Mattei L.M., Iwasaki A. CD8+ T cell responses following replication-defective adenovirus serotype 5 immunization are dependent on CD11c+ dendritic cells but show redundancy in their requirement for TLR and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor signaling. J Immunol. 2010;185(3):1513–1521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahi Y.S., Bangari D.S., Mittal S.K. Adenoviral vector immunity: its implications and circumvention strategies. Curr Gene Ther. 2011;11(4):307–320. doi: 10.2174/156652311796150372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vogels R., Zuijdgeest D., van Rijnsoever R., Hartkoorn E., Damen I., de Béthune M.P. Replication-deficient human adenovirus type 35 vectors for gene transfer and vaccination: efficient human cell infection and bypass of preexisting adenovirus immunity. J Virol. 2003;77:8263–8271. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8263-8271.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barouch D.H., Pau M.G., Custers J.H., Koudstaal W., Kostense S., Havenga M.J. Immunogenicity of recombinant adenovirus serotype 35 vaccine in the presence of pre-existing anti-Ad5 immunity. J Immunol. 2004;172(10):6290–6297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiver J.W., Emini E.A. Recent advances in the development of HIV-1 vaccines using replication incompetent adenovirus vectors. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:355–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.104344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts D.M., Nanda A., Havenga M.J., Abbink P., Lynch D.M., Ewald B.A. Hexon-chimaeric adenovirus serotype 5 vectors circumvent pre-existing anti-vector immunity. Nature. 2006;441(7090):239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature04721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chillón M., Lee J.H., Fasbender A., Welsh M.J. Adenovirus complexed with polyethylene glycol and cationic lipid is shielded from neutralizing antibodies in vitro. Gene Ther. 1998;5:995–1002. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beer S.J., Matthews C.B., Stein C.S., Ross B.D., Hilfinger J.M., Davidson B.L. Poly [lactic-glycolic] acid copolymer encapsulation of recombinant adenovirus reduces immunogenicity in vivo. Gene Ter. 1998;5:740–746. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiang Z.Q., Gao G.P., Reyes-Sandoval A., Li Y., Wilson J.M., Ertl H.C.J. Oral vaccination of mice with adenoviral vectors is not impaired by preexisting immunity to the vaccine carrier. J Virol. 2003;77(20):10780–10789. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.20.10780-9.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croyle MA, Patel A, Tran KN, Gray M, Zhang Y, Strong JE, et al. Nasal delivery of an adenovirus-based vaccine bypasses pre-existing immunity to the vaccine carrier and improves the immune response in mice. PLoS ONE 3(10):e3548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Zhao J, Alshukairi AN, Baharoon SA, Ahmed WA, Bokhari AA, Nehdi AM, et al. Recovery from the Middle East respiratory syndrome is associated with antibody and T cell responses. Science 2017; 2(14):eaan5393. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aan5393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Tatsis N., Lasaro M.O., Lin S.W., Haut L.H., Xiang Z.Q., Zhou D. Adenovirus vector-induced immune responses in nonhuman primates: responses to prime boost regimens. J Immunol. 2009;182(10):6587–6599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harvey B.G., Worgall S., Ely S., Leopold P.L., Crystal R.G. Cellular immune responses of healthy individuals to intradermal administration of an E1–E3- adenovirus gene transfer vector. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10(17):2823–2837. doi: 10.1089/10430349950016555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santra S., Seaman M.S., Xu L., Barouch D.H., Lord C.I., Lifton M.A. Replication-defective adenovirus serotype 5 vectors elicit durable cellular and humoral immune responses in nonhuman primates. J Virol. 2005;79(10):6516–6522. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6516-6522.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoshino T., Nakamura H., Okamoto M., Kato S., Araya S., Nomiyama K. Redox-active protein thioredoxin prevents proinflammatory cytokine- or bleomycin-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care med. 2003;1689(9):1075–1083. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200209-982OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim H.W., Canchola J.G., Brandt C.D., Pyles G., Chanock R.M., Jensen K. Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89(4):422–434. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hwang H.S., Lee Y.T., Kim K.H., Park S., Kwon Y.M., Lee Y. Combined virus-like particle and fusion protein-encoding DNA vaccination of cotton rats induces protection against respiratory syncytial virus without causing vaccine-enhanced disease. Virology. 2016;494:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knudson C.J., Hartwig S.M., Meyerholz D.K., Varga S.M. RSV vaccine-enhanced disease is orchestrated by the combined actions of distinct CD4 T cell subsets. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(3):e1004757. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.