Abstract

Objective:

Stigma toward individuals with mental disorders has been studied extensively. In the case of Latin America and the Caribbean, the past decade has been marked by a significant increase in information on stigma toward mental illness, but these findings have yet to be applied to mental health services in Latin America. The objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of studies relating to stigma toward mental illness in Latin America and the Caribbean. The authors specifically considered differences in this region as compared with manifestations reported in Western European countries.

Methods:

A systematic search of scientific papers was conducted in the PubMed, MEDLINE, EBSCO, SciELO, LILACS, Imbiomed, and Bireme databases. The search included articles published from 2002 to 2014.

Results:

Twenty-six studies from seven countries in Latin America and the Caribbean were evaluated and arranged into the following categories: public stigma, consumer stigma, family stigma, and multiple stigmas.

Conclusion:

We identified some results similar to those reported in high-income settings. However, some noteworthy findings concerning public and family stigma differed from those reported in Western European countries. Interventions designed to reduce mental illness-related stigma in this region may benefit from considering cultural dynamics exhibited by the Latino population.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, community mental health, epidemiology, social anthropology, psychosis

Introduction

The Declaration of Caracas in 1990 represented a marked shift in mental health policy in Latin America, whereby a number of mental health reforms were implemented in different countries of this region.1 Each of these mental health reforms has three main objectives: 1) to anchor mental health within primary care; 2) to develop community mental health services; and 3) to reduce the stigma associated with mental illness.2 Examples of successful models are now found in Brazil, Panama, and Chile.3 However, a recent evaluation of mental health services in Latin America reported that stigma is still an important barrier to recovery in people with mental illness.4

Stigma toward individuals with mental disorders has been studied at length in Europe, North America, Africa, and Asia for almost half a century.5 In the case of Latin America and the Caribbean, while the past decade has been marked by a significant increase in information on stigma toward mental illness,6 7-8 the last review to analyze aspects of stigma at the regional level was published a decade ago.9

Link et al.10 have postulated “modified labeling theory,” which articulates the process by which stigmatization of mental illness occurs. Labeled individuals, in anticipation of stigmatizing responses from society, may adopt harmful coping mechanisms (e.g., secrecy or withdrawal), leading to worse psychological symptoms, diminished social networks, and reduced life opportunities.

Additionally, theorists have long identified that culture is a key factor that shapes stigma.11 According to Yang et al.,11 each local social group engages in a set of fundamental daily activities that “matter most,” and stigma affects those activities and capacities most profoundly. Stigma is thus viewed as a fundamentally “moral experience” for individuals, threatening that which is most at stake in local worlds (which might be viewed as a local community or culture) and manifested in the daily practices and social activities of its members. Therefore, cultural factors may be viewed as key in determining the fundamental capacities that shape stigmatization among different populations. However, the study of stigma toward people with mental illness has focused on the development of standardized assessments that do not incorporate cultural elements.12 Indeed, in a recent systematic review, Yang et al. found that the vast majority of studies analyzed (77%) utilized adaptations of existing Western-developed stigma measures.13

Culture, stigma, and Latin America

The concepts of Latin America or Latino are used here to refer to people from different geographical areas within the Americas. This includes Mexico, countries from Central America (i.e., Panama, Guatemala), South America (i.e., Argentina, Brazil), and the Caribbean (i.e., Cuba, Jamaica). Understandably, the Latin American population is heterogeneous.14 Notwithstanding, Latinos have several cultural features and values in common.15 While standardized approaches to stigma offer notable methodological advantages,12 we believe that a full understanding of the shared cultural aspects of stigma in the Latino population should consider cultural influences within this region. Therefore, we propose a framework of key cultural orientations to interpret stigma that have been previously identified in Latin America: familismo, compadrazgo, machismo, and dignidad y respeto.14

The concept of familismo encompasses three dimensions: 1) familial obligations, which entails providing material and emotional support for the family; 2) support from family, which is the expectation that family members should support and help one another; and 3) family as reference, which connotes the expectation that important decisions are made with the best interest of the entire family unit taken as the primary consideration.16 Machismo refers to a patriarchal structure of society whereby the man has the main role as protector and provider for his family.15 The main role for women, in contrast, is to become a “holy and pure” mother, dedicated to caring for her husband, children, and family. Therefore, many communities within Latin America have been found to reproduce authoritarian relationships between genders.15

Compadrazgo is a “formal friendliness” which values warm, close, and caring relationships, even within professional situations,17 which become strengthened only when individuals are able to offer and to reciprocally exchange favors. Finally, dignidad y respeto is a value emphasizing the intrinsic worth of all individuals and promoting equality, empathy, and connection in one’s relationships. This cultural value is associated with a hierarchy of deference in which elders and parents are accorded the highest status and merit more respect than youths.14 This value also may be moderated by other values such as machismo, whereby men may command more dignity and respect than women.14

Within this context, our review was motivated by: the lack of an up-to-date review, considering that research in this area has made great strides in the past 10 years; the establishment of the community psychiatry model in Latin America and the Caribbean, in which the fight against stigma is a growing priority; and, finally, the possible contribution to the generation of evidence-based anti-stigma strategies from this region, taking into account that some characteristic features from Latino communities have been identified as potential facilitators for decreasing stigma in people with mental illness.18

The objective of this paper was to conduct a systematic review of studies about all types of stigma toward mental illness in Latin America and the Caribbean. In this review, we assume that such differences may represent in part universal forms of stigma, as well as represent cultural expressions of stigma toward mental illness in this region.

Methods

Literature search and article selection strategy

We conducted a systematic search of scientific papers in the PubMed, MEDLINE, EBSCO, SciELO, LILACS, Imbiomed, and Bireme databases. One key strength of our strategy is that, unlike other literature reviews, we included Spanish- and Portuguese-language search engines in our strategies. The search included articles published from January 2002 to July 2014. The keywords included were: stigma (included keys terms of attitudes OR labeling OR prejudice OR social acceptance OR social stigma OR social discrimination OR social perception OR stereotyping); mental illness (included broad terms of adjustment mental disorders OR anxiety disorders OR eating disorders OR mood disorders OR neurotic disorders OR schizophrenia); Latin America (included related terms of Caribbean OR South America OR Middle America OR Central America); culture (OR race OR minority OR ethnicity OR anthropology OR qualitative); AND literature review (OR systematic review OR meta-analysis). These terms were combined to yield a more precise search strategy.

Titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by authors FM, SS, and TT. Documents that did not meet the inclusion criteria (detailed below) were discarded. Each disagreement was resolved via discussion with the research coordinator (FM). Furthermore, additional articles of interest were identified by a hand search of the reference sections of articles retrieved by the electronic database search.

The reviewed articles were organized and characterized as follows. The country where each study took place was noted, along with the sample size and makeup, and the aims and methods of the study. The “stigma type” addressed in each study was classified as: a) public stigma; b) self-stigma; c) family stigma; or d) institutional stigma (Table 1).

Table 1. Stigma type assessed by studies.

| Stigma type | Definition | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Public | The process in which the general public stigmatizes individuals with mental illness, consisting of processes of stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. | 12 (46.2) |

| Institutional | Institutional practices that work to the disadvantage of the stigmatized group or person. | 0 (0.0) |

| Self | When an individual takes publically acknowledged stereotypes held by society and applies them to him or herself. | 7 (26.9) |

| Family | When stigma is experienced among those who are related by kinship to labeled individuals. | 3 (11.5) |

| Multiple stigma | 4 (15.3) | |

| Total | 26 (100.0) |

Another category, multiple stigma, was used to classify studies that addressed more than one type of stigma. Finally, the main results of each study were summarized.

Inclusion criteria

Articles were included in this review if they: 1) were studies of Latin American and Caribbean populations (i.e., of native individuals living in the region); 2) reported primary research, published in peer-reviewed scientific journals; 3) focused on evaluating stigma toward adults and/or children with a diagnosis of mental disorder, or their relatives; 4) included quantitative or qualitative measures of public stigma, family stigma, institutional stigma, and/or consumer stigma (studies which analyzed stigma solely from the media were not included); and 5) were written in English, Spanish, or Portuguese.

Results

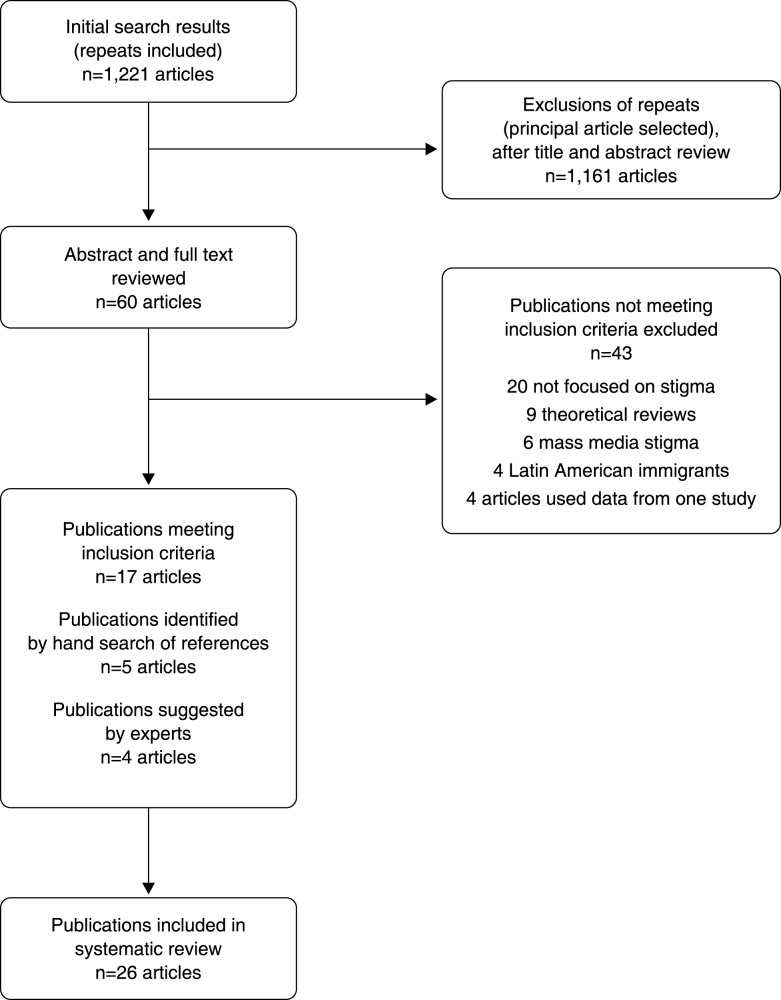

A systematic search of the databases yielded 1,221 documents. Of these, 1,161 papers were excluded, mainly due to repetition or because these studies were not focused on issues related to mental health. For the final review, of a subtotal of 60 articles, 43 additional articles were excluded: 20 because their primary aim was not the assessment of stigma, nine theoretical reviews, six focused on stigma associated with the media, four which looked at Latin American immigrants from other countries, and four others that reported different aspects of data from a single study. Thus, 26 articles met the selection criteria and were included in this review, arranged by the categories introduced earlier (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Search results and article selection flow chart.

The languages in which the documents were written, from most to least frequent, were English (n=14), Spanish (n=9), and Portuguese (n=3). Most of the research was carried out in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina. Remaining studies were conducted in Jamaica, Colombia, Peru, and Chile. The most evaluated type of stigma was public stigma (46.2%), followed by consumer stigma (26.9%). In turn, studies on family stigma were infrequent (11.5%). We did not locate any studies regarding institutional stigma (Table 1).

In terms of methodology, 17 studies were quantitative, eight were qualitative, and one integrated both methodological designs. The quantitative studies used questionnaires developed by the authors (ten studies, most of which did not consider cultural specific aspects), or adaptations of instruments designed in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, or other Anglo-Saxon countries (nine studies). With respect to qualitative studies, the principal information collection strategies were structured interviews, semistructured interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic interviews. Finally, we organized our results in Table 2 by type of stigma, sample and location, aims of study, methods, and main results.

Table 2. Description of results.

| Study | n, country | Aims | Method/data collection | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public stigma | ||||

| Quantitative | ||||

| Delevati & Palazzo19 | 536 employers, Brazil | To learn the attitudes of employers toward people with mental disorders. | - Questionnaire: sociodemographic information- Attitudes and opinions about mental illness | Participating employers scored highest in benevolence. Authoritarianism was also a common factor.Employers are generally in favor of social restriction. |

| Des Courtis20 | 112 mental health professionals, Brazil1, 073 mental health professionals, Switzerland | 1) To assess knowledge about mental health and general attitudes toward people with mental illness in a sample of mental health professionals in Brazil and Switzerland.2) To compare the results between different professional groups. | - Questionnaire developed by the authors- Semistructured interview- DSM-III-R case vignette | Mental health professionals in Switzerland, compared with those from Brazil, showed greater social distance and stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness (p < 0.001). Brazilian mental health professionals showed more positive attitudes toward community psychiatry (p < 0.001). |

| Gibson6 | 1,306 community members, Jamaica | To determine the degree of internalization of stigma toward mental illness and the assimilation of attitudes, cognitions, and behaviors in people who are at risk of stigmatizing in Jamaica. | - Semistructured interview- Questionnaire developed by the authors | People with family members with mental disorders are less likely (57.0%) than others (66.4%) to avoid them. They were also more likely to be friendly (82.6 vs. 72.8%).Moreover, 79-82% of respondents displayed attitudes of compassion, care, love, and concern, compared with 37-43% who showed attitudes of anger, fear, and disgust. |

| Ronzani21 | 609 mental health professionals, Brazil | To investigate the opinions, moral stereotypes, and attributions regarding alcohol and drug dependence in primary centers. | - Questionnaire developed by the authors assessing stereotypes and attributions- Judgment scale on alcoholism- Questionnaire about mental disorders- Personal difficulty evaluation | The moral (or stigmatizing) judgments between professional groups showed significant differences (p < 0.01); nursing assistants were the most stigmatizing professionals.Use of tobacco, marijuana/cocaine, and alcohol were most highly judged (p < 0.05), compared with other disorders. |

| Fresán22 | 258 community members, Mexico | To develop an instrument about public conception of aggressiveness in schizophrenia and to determine its reliability and validity. | - Questionnaire developed by the authors: Public CAQ- Sociodemographic information | 53.9% of participants affirmed that the person described in the vignette (someone with a diagnosis of schizophrenia) was not aggressive or dangerous. Only 23.3% of the sample recommended psychopharmacology as the first line of treatment. Finally, the CAQ had adequate internal consistency (alpha = 0.74). |

| Leiderman7 | 1,254 community members, Argentina | To assess knowledge, social distance, and perceived social discrimination toward people with schizophrenia. | - Scale developed by the authors assessing: knowledge about schizophrenia, social distance, perception of social discrimination | 44.4% of the population surveyed believed that people with schizophrenia suffer from “multiple personality,” and 69.9% believe that these individuals show “bizarre or inadequate behavior.” Almost 80% of the population had an elevated perception of social discrimination toward individuals with mental illness. |

| Loch8 | 1,414 psychiatrists, Brazil | To assess the attitudes of Brazilian psychiatrists toward people with schizophrenia. | - Questionnaire developed by the authors assessing: stereotypes, social distance, and prejudice; drugs and tolerance of side effects; sociodemographic and professional information concerning the psychiatrists | Psychiatrists had negative stereotypes and social distance toward people with schizophrenia.Psychiatrists who worked in a university psychiatric hospital exhibited lower levels of social distance that psychiatrists who did not (p = 0.009).Older psychiatrists had positive stereotypes and less prejudice (p = 0.012). |

| Peluso23 | 500 community members, Brazil | To assess public stigma toward people with schizophrenia and possible factors associated with this phenomenon. | - Vignette (DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria)- Questions about vignette | Logistic regression analysis showed that the participants identified the vignette as concerning mental illness (p = 0.02, OR = 1.26). The attribution of “biological reasons” (p = 0.00, OR = 2.26) was associated with increased perceptions of danger. |

| Fresán24 | 110 community members, Mexico | To evaluate the attitudes of a group of female psychology students toward mental illness to determine their perceptions of risk and aggressiveness of individuals with schizophrenia. | - OMI-M- CPA | 59.1% of the students felt that the person described in the clinical case vignette could be aggressive in some way.The students who perceived the person described in the vignette as aggressive exhibited higher scores in areas of restriction and higher pessimistic prediction in the total OMI-M score. |

| Robles García25 | 1,038 community members, Mexico | To assess mental illness recognition and beliefs about treatment of schizophrenia, and to determine their relationship with perception of patient aggressiveness/dangerousness. | - CPA- Questionnaire developed by the authors assessing: perception of patient aggressiveness and dangerousness; mental illness recognition and beliefs about adequate treatment | 54.5% of responders believed that the person described in the vignette would eventually behave aggressively. Specifically, verbal aggression was the most common belief (n=420, 40.5%).Most women could recognize mental illness and suggested psychiatric interventions as the most adequate treatment to control and reduce symptoms. Alternatively, men considered non-psychiatric interventions (such as talking with families or friends) more often. |

| Qualitative Hickling26 | ||||

| 159 community members, Jamaica | To assess whether deinstitutionalization and community mental health care reduce stigma toward mental illness in Jamaica. | - Focus groups (20, of separate and mixed gender) | Feelings of avoidance and fear of violent behavior during the period of deinstitutionalization were transformed into feelings of compassion and kindness after the integration of community mental health services into the primary care systems. | |

| Martin27 | Eight community members, Brazil | Describe living conditions and sociability among people with severe mental disorders living in slums. | - Ethnographic observations- Semistructured in-depth interviews | People in the community believed that individuals with mental illness were “angry,” “nervous,” or “mentally weak.”There was great fear about security, i.e., that individuals with impaired control could attack other residents. The community members also expressed some attitudes indicative of compassion. |

| Consumer stigma | ||||

| Quantitative Flores28 | ||||

| 100 consumers, Mexico | 1) To carry out a Spanish adaptation of the ISS.2) To evaluate basic psychometric properties among Mexicans with severe mental disorders. | - ISS- GAF- CGI | The Mexican version showed good internal consistency, with alpha coefficients above 0.60 in all subscales. The dimensional assessment of the construct is highly reliable, with a coefficient of 0.87. | |

| Vázquez29 | 241 consumers, Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia | To evaluate the association between perceived stigma and functionality in consumers with bipolar disorder in Latin America. | - FAST- ISE | Functional impairment was significantly associated with perceived stigma experience: Brazil (r = 0.49, p = 0.001; r = 0.54, p = 0.001).Colombia (r = 0.34, p = 0.002; r = 0.26, p = 0.017).Argentina (p ≤ 0.10) (r = 0.21, p = 0.078; r = 0.18, p = 0.10). |

| Mileva30 | 392 consumers, Argentina and Canada | 1) To adapt ISE.2) To evaluate basic psychometric properties among Argentines with bipolar disorder. | - ISE- SES- SIS | Over 50% of respondents believed that the average person is afraid of those with mental illnesses and that stigma associated with mental illness has affected their quality of life and their self-esteem.SES: coefficient of reliability = 0.78.SIS: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91. |

| Mora-Ríos31 | 59 consumers (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, drug abuse and dependence, obsessive/compulsive disorder, among others), Mexico | To analyze sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial variables related to self-stigma in people with mental illness. | - Sociodemographic and clinical data- EPCP- ISMI | More than 90% of consumers experienced rejection at least once in their lives. According to respondents, the family was the main source of discrimination, and behaviors such as underestimation or hostile attitudes were frequently reported.Perception of the consequences of mental illness in the workplace explained the variance of alienation (33%), stereotype endorsement (21%), and stigma resistance (23%), all subscales of the ISMI. The consequences of mental illness on family relationships, together with medical diagnosis and time under treatment, explained 49% of variance of the discrimination subscale. |

| Qualitative Jorge & Bezzerra32 | ||||

| 8 consumers, Brazil | To understand the social representations of employment for consumers and mental health professionals. | - Semistructured interview | Results were organized according to three categories:1) Be excluded from work: life difficulties, bias, disability, and social isolation.2) Harm resulting from the exclusion from work: Marginalization and emotional disintegration.3) Sense of inclusion at work: Need and symbolic value. | |

| Araújo33 | 1 consumer, Brazil | To understand the stigma experience of a person with a diagnosis of somatoform disorder. | - Informal conversations- Participant observation- Field notes | Presence of stigma attached to mental illness in the consumer’s daily life and relationships. Stigma was manifested through discrimination, rejection, difference, and isolation. Stigma led to social isolation due to fear of revealing illness. |

| Robillard34 | 22 consumers, Peru | To understand gender keys that produce social stigma of mental illness in the general population. | - Field notes- Focus group | Participants’ labels, such as insane, mad, or manic, were associated with violent behavior, bizarre behavior, animal-like behavior, loss of control, and homelessness.Most people had experienced discrimination and/or exclusion. |

| Family stigma Quantitative Lolich35 | ||||

| 175 consumers, Argentina | To investigate the clinical characteristics of consumers with bipolar disorder who have manifested psychotic symptoms. | - Clinical evaluation, YMRS, and HAM-D- Functionality: FAST- Stigma: ISE | People with BP with psychotic onset had higher work functioning than people with BP without psychotic onset (p = 0.037). For consumers with psychotic onset, a greater perception of stigma in the item of stigmatization due to family illness was identified (p = 0.003). | |

| Loch36 | 169 consumers, 169 relatives, Brazil | 1) To evaluate re-hospitalization rates of people with psychosis and bipolar disorder.2) To study the determinants of readmission. | - Telephone interview using a questionnaire developed by the author | Rehospitalization rate after one year was 42.6%. Family members’ agreement with the consumers’ ongoing hospitalization was a predictor associated with readmission. Readmitted persons were often classified as dangerous and unhealthy by their own families. |

| Loch37 | 1,015 general population individuals, Brazil | To assess stigma toward schizophrenia in a sample of the Brazilian general population. | - Vignette (DSM-IV criteria)- Questions about vignette- Likert scale of stereotypes (12 items), social restriction (3 items), perceived prejudice (8 items), and social distance (7 items) | Four stigma profiles were found: no stigma individuals (n=251); labelers (n=222) scored high on social distance; discriminators, the group with the majority of individuals (n=302), showed high levels of stigmatizing beliefs in all dimensions; and unobtrusive stigma individuals (n=240). |

| Multiple stigma Chuaqui38 | ||||

| 250 consumers, 60 relatives, 200 community members, 150 employers, Chile | To describe stigma toward mental illness in a group of consumers, family members, employers, guardians, and community members. | - Semistructured interview- Questionnaire developed by the authors | Consumer stigma: only 13.3% were working in competitive situations and unprotected.Family stigma: 71.6% knew nothing or little about schizophrenia before their family members was diagnosed.Public stigma: 68% of employers think that people with schizophrenia do even simple tasks poorly. | |

| Uribe Restrepo39 | 52 consumers, 18 relatives, Colombia | To describe characteristics of stigma. | - Focus group- Semistructured interview | Consumer stigma: consumers described stigma as rejection, ignorance, derogatory language, low self-esteem, lack of autonomy and freedom. These included feelings of social exclusion and of being different.Family stigma: consumers’ siblings commented on their denial, pain, and frustration after learning the diagnosis. |

| Wagner40 | 146 consumers, 80 relatives, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, England, Spain, and Venezuela | To examine existential questions from people with schizophrenia and their caregivers. | - Focus groups were used to gather qualitative data | Consumer stigma: consumers experience a sense of uselessness, feel unproductive, dependent and therefore inferior to others. Gender differences were reported.Family stigma: several families feel embarrassed to have a “special member.” Many families feel like victims of a cruel fate. Abandonment and institutionalization occur specially in Argentina and Venezuela. |

| Mora-Ríos41 | 8 health professionals, 15 relatives, 4 community members, 2 consumers, Mexico | To describe the cultural adaptation and semantic validation of three instruments for measuring stigma and mental illness. | - ISMI- OMI- DDS- Focus groups- Semistructured interviews | The instruments included in this research had good levels of understanding, acceptability, relevance, and semantic integrity. After qualitative analysis, the responders suggested several new items for addition to each instrument. Many related to gender issues (“Most people think that a woman is more prone to mental illnesses,” “Women are more likely to develop a mental illness”) or family (“Most of the relatives of a person who is mentally ill are ashamed of him/her,” “Due to my mental illness I’m feeling closer to my family”). |

BP = bipolar disorder; CAQ = Conception of Aggressiveness Questionnaire; CGI = Clinical Global Impression; CPA = Cuestionario de Concepto Público de Agresividad (Questionnaire of Public Concepts of Aggressiveness); DDS = Devaluation-Discrimination Scale; EPCP = Escala de Percepción de Consecuencias del Padecimiento (Scale of Perceived Illness Consequences); FAST = Functioning Assessment Short Test; GAF = Global Assessment Functioning; HAM-D = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; ISE = Inventory of Stigmatizing Experiences; ISMI = Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness; ISS = Internalized Stigma Scale; OMI-M = Opinions about Mental Illness; OR = odds ratio; SES = Stigma Experiences Scale; SIS = Stigma Impact Scale; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale.

Public stigma

The studies identified negative prejudices toward people with mental illness which have been commonly identified in Western European contexts, such as being categorized as “dangerous” and “violent.” Leiderman et al.7 interviewed 1,254 community members from Argentina, and reported that 69.9% of the surveyed individuals believed that people with schizophrenia show bizarre or inadequate behavior. Community respondents also reported harboring stereotypes about the potential “chronicity” of mental disorders. Similarly, Peluso & Blay23 determined that attributing “biological reasons” to the causation of mental disorders was significantly associated with an increased perception of danger in a sample of 500 respondents from the general population. Finally, in Mexico, Robles-García et al.25 evaluated the public conception of aggressiveness about schizophrenia among 1,038 community members. More than 54.5% of the respondents believed that the person described in the vignette would eventually behave aggressively. Verbal aggression was the most common belief (n=420, 40.5%). Men considered non-psychiatric interventions to treat mental disorders more often.

On the other hand, negative attitudes from mental health professionals were identified in most,21 but not all of the reports.20 In a study with a sample of 1,414 psychiatrists, Loch et al.8 reported that the respondents endorsed negative attitudes and social distance toward people with schizophrenia. Nevertheless, psychiatrists who worked in a university psychiatric hospital reported less social distance than colleagues who did not work in a psychiatric hospital setting. In a subsequent study, the same authors compared psychiatrists’ responses and responses from 1,015 individuals of the general population, finding that the psychiatrists reported lower social distance scores compared with members of the general population.37

Lastly, Fresán et al.24 evaluated the attitudes of a group of female psychology students (110 participants) through the Opinions about Mental Illness-OMI (OMI-M). They reported that 59.1% of the students felt that the person described in the clinical case vignette (of someone with psychosis) could be aggressive in some way. The students who perceived the person described in the vignette as aggressive also exhibited higher scores in areas of social restriction and higher pessimistic prediction of recovery. In the same line, in a sample of employers, results revealed a devaluation of mentally ill individuals’ labor skills: 68% of employers thought that people with schizophrenia performed even simple tasks poorly.38

Regarding local expressions of stigma, Des Courtis et al.20 carried out a study with a sample of mental health professionals from Brazil and Switzerland. Participants in Switzerland, compared with those from Brazil, showed greater social distance and stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness (p < 0.001). Brazilian mental health professionals, in turn, showed more positive attitudes toward community psychiatry (p < 0.001).

Gibson et al.6 showed that 79-82% of respondents in a national survey in Jamaica (n=1,306) exhibited positive attitudes and behavior toward people with mental illness. Attitudes of compassion, care, love, and concern were commonly reported. Delevati & Palazzo19 evaluated the attitudes of 536 employers toward people with mental disorders in Brazil, and participating employers scored highest in benevolence and authoritarianism on the OMI-M. Moreover, Fresan et al.22 interviewed 258 community members concerning their perceptions of aggressiveness relating to people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Overall, 53.9% of the participants declared that the person described in the vignette was not aggressive or dangerous. Only 23.3% of the sample, especially women, recommended psychopharmacology as the first line of treatment.

Finally, in a qualitative study conducted in Jamaica, Hickling et al.26 identified that mental health consumers, family members, and community members had more positive attitudes toward mental illness when the community mental health services were integrated into the primary care network. Similarly, Martin et al.,27 in an ethnographic study that described the living conditions and sociability among people with severe mental disorders living in slums in Brazil, reported that the impaired social functioning characteristic of individuals with psychotic disorders was exacerbated in this vulnerable environment. However, most of the community members expressed tolerance, pity, compassion, support, and solidarity toward slum residents with mental health problems.

Consumer stigma

The main results showed that consumers commonly experience functional impairment and social exclusion.28,34 For instance, Va�zquez et al.29 evaluated the association between perceived stigma and functionality in 241 consumers with bipolar disorder from Brazil, Colombia, and Argentina. Functional impairment was significantly associated with perceived stigma. Furthermore, a Chilean study of 250 consumers only reported that 13.3% were working in competitive situations and most were not receiving any welfare benefits.38

Uribe Restrepo39 carried out in-depth interviews with 52 consumers and 18 relatives from Colombia. Consumers described stigma as rejection, ignorance, and derogatory language, which led to low self-esteem, lack of autonomy and freedom, and feelings of social exclusion and “being different.” In the same line, Arau�jo et al.,33 in an ethnographic study, found that stigma manifested itself through discrimination, rejection, difference, and isolation. The consumers also reported fear of being excluded from employment and other social spaces if they disclosed their psychiatric diagnosis.32

A comparison regarding perceived stigma between Argentina and Canada was done by Mileva et al.30 The authors interviewed 392 consumers using the Stigma Experiences Scale (SES) and Stigma Impact Scale (SIS). Over 50% of respondents believed that the average person is afraid of individuals with a mental illness and that stigma associated with mental illness has affected their quality of life and their self-esteem. SES and SIS scores were significantly different between the two populations, with the Argentinean population scoring lower on both the SES and lower on the SIS as well. The authors stated that family dynamics and emotional closeness with family members might differ culturally between the two groups, and this could become in a protective factor for Argentinean people.

Concerning internalized stigma and discrimination, Mora-Rios et al.31 applied the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) and the Scale of Perceived Illness Consequences (Escala de Percepción de Consecuencias del Padecimiento, EPCP) to 59 consumers in Mexico City. More than 90% of respondents had experienced rejection at least once in their lives. Family was identified as the principal source of discrimination, and behaviors such as underestimation of abilities or hostile attitudes from relatives and extended family were frequently reported.

Family stigma

Studies with relatives focused mostly on stigma “from” the family, not stigma “toward” the family. Research with relatives of people with mental disorders highlighted their limited knowledge about mental illness prior to their family members’ diagnosis.38 Upon learning the psychiatric diagnosis, families often experienced frustration, denial, and grief.39

Nonetheless, in a general population study in Jamaica (n=1,306 community members), Gibson at al.6 found that people who had relatives with a mental disorder were less likely (57.0%) than others (66.4%) to avoid individuals with mental illness. Family members were also slightly more likely to be friendly (82.6 vs. 72.8%) and tended to socialize with mental health consumers more (55.5 vs. 44.2%).

In terms of stigma toward the family, Lolich et al.35 investigated the characteristics of 175 consumers with bipolar disorder, with and without psychotic symptoms at onset, and found that a greater proportion of consumers with psychosis thought that their family had been stigmatized due to their mental illness, in comparison to bipolar patients without psychotic symptoms at onset (31.82 vs. 10.67%, p = 0.003). Regarding local manifestations of stigma in Latin America, Loch36 interviewed 169 consumers and inquired about re-hospitalization rates of people with psychosis and bipolar disorder. Family members’ agreement with the consumers’ ongoing hospitalization was a predictor of readmission. Readmitted persons were often classified as dangerous and unhealthy by their own families.

Multiple stigma

One study by Loch et al.37 that considered a sample of 1,051 community members from Brazil, who were interviewed by telephone, identified four stigma profiles: no stigma individuals (n=251), labelers (n=222), discriminators (n=302), and unobtrusive stigma individuals (n=240). People with the labeler profile more often had familial contact with mental illness and, paradoxically, scored higher on social distance. The authors concluded that these findings are likely determined by specific cultural characteristics of Latin American families.

In a qualitative, multisite study (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Spain, UK, and Venezuela) that interviewed 146 people with schizophrenia and 80 caregivers, Wagner et al.40 found that stigma and discrimination was an omnipresent existential theme. Some participants from Latin America, especially women, reported several pressures from their families to accomplish the typical role of woman within a family (i.e., cooking, cleaning), but they were not able to obtain a romantic partner or rent a house on their own.

Finally, in Mexico, Mora-Rios et al.41 carried out adaptation and validation of several instruments about stigma: the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) inventory, the Opinions about Mental Illness Scale (OMI), and the Devaluation-Discrimination Scale (DDS). This study consisted of semistructured interviews and focus groups with eight health professionals, 15 relatives, four community members, and two consumers. The instruments showed good levels of understanding, acceptability, relevance, and semantic integrity. After analysis, several new items were proposed by participants for addition to each instrument. Many of the proposed items were related to gender issues (“Most people think that a woman is more prone to mental illnesses,” “Women are more likely to develop a mental illness”) or family (“Most of the relatives of a person who is mentally ill are ashamed of him/her,” “Due to my mental illness I’m feeling closer to my family”).

Discussion

The main purpose of this article was to conduct a systematic review of the literature about mental illness stigma in Latin America and the Caribbean. Many of the results reported in this region were similar to those reported in studies carried out in other parts of the world. For example, regarding public stigma, stereotypes and prejudices associated to violence, unpredictability, and disability are common in many countries around the world.35 In a multisite study with representative national samples of adults from 16 countries (n=19,508), Pescosolido et al.42 found the highest levels of stigmatizing responses relating to child care providers, potential for violence (self-directed), unpredictability, marrying, and teaching children. Thornicroft43 stressed that the majority of people with mental illness worldwide suffer stigma and discrimination in multiple aspects of their life: work, housing, access to health services or the legal system, etc.

Concerning self-stigma, experiences of rejection, isolation, low self-esteem, and hope are frequently reported by users of mental health services. For instance, Corrigan et al.44 tested a model of self-stigma with 85 people with schizophrenia in the United States and found a significant association between stigma and lowered self-esteem, self-efficacy, and hope. Other studies from Western European countries have also confirmed an association between self-stigma and higher rates of hospitalizations.45,46

Finally, negative attitudes and discrimination are usually experienced by family members,47 as was established in some of the studies included in this review. In the same line, caregiver burden, sleep disorders, low social support, and impaired quality of life among caregivers are usually reported in the literature.48

However, some important results of the studies included in this review differed from those reported in Western European settings. For instance, regarding public stigma, the results of the Jamaican studies conducted by Hickling et al.26 and Gibson et al.6 indicated that, if mental health services are integrated into the primary care system, stigma in community members may decrease, while benevolence and compassion toward individuals with a mental illness could grow.

One explanation for these findings arises from the deinstitutionalization movement and development of a community mental health system in Jamaica.49 The authors pointed out that this process considered several qualitative assessments of the population, addressing particular cultural aspects of Caribbean countries. Indeed, in comparison with another report,50 Jamaican people began to show positive attitudes toward mental illness as early as the 1970s, with special mental health community work carried out via psycho-historiography and cultural therapy. Both approaches highlight the history, knowledge, and identities of specific communities.49

Attitudes of compassion and benevolence associated with Latin American culture have been also identified in other studies. For instance, Silva de Crane and Spielberger,51 in a sample of 309 Anglo, Hispanic American, and Black American college students, found the highest OMI-M Benevolence scores in Hispanic people. This could be explained if one relates benevolence and compassion to the Latin American cultural orientations of compadrazgo or dignidad y respeto. Some authors have linked this cultural phenomenon to social capital within Hispanic groups, rooted in the power of family and community, which can be a protective factor for stigma.18

In general, results of Brazilian studies about stigma from health care professionals showed negative attitudes toward individuals with a mental illness. Nevertheless, compared with professionals from Switzerland20 and the general population,37 Brazilian healthcare professionals endorsed less social distance and more positive attitudes. It is worth noting that perspectives on mental health problems from pre-industrialized societies generally include a religious dimension that might prevent the negative effect of stigmatization.52 In Brazil, religious beliefs about mental illness are common and Christianity is the main religion, which may serve to ameliorate mental illness stigma in this context. In a study conducted by Paro et al.53 in a sample of 319 medical students, the Brazilian version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy was adapted, and results showed that the first factor to emerge was a compassionate care component, which the authors linked to the humane care perspective promoted by Christian religions.

Additionally, several of the findings described throughout this manuscript relate with gender issues,40,41 machismo, and dignidad y respeto toward men. Many Latin American societies are traditional and influenced by the legacy of Colonialism and Christianity,16 which determined an active and authoritarian role for men (provider and protector of his family) and passive and secondary social roles for women, who must devote themselves to household chores and duties (i.e., cooking, cleaning), as reported by Wagner et al.40 Therefore, women may be more stigmatized if they lose their capacity to fulfill family roles, and men may hide their psychiatric diagnosis and refuse to attend mental health services to avoid losing status and the ability to work.54

Finally, we obtained particularly important findings related to family stigma. Mileva et al.30 reported findings concerning the potential protective role of family in Argentina. From their point of view, family members, friends, and relatives provide emotional assistance to family members who have a diagnosis of mental illness. This makes sense if one conceptualizes Latin families as groups with close and meaningful relationships among their members.55 However, some findings went in the opposite direction.31,37 According to consumers interviewed by Mora-Rios,31 family reactions and behaviors might be the main source of discrimination for people with mental disabilities. Additionally, Loch et al.,36 after evaluating a sample of relatives, found that more contact entailed greater social distance between caregivers.

From a cultural perspective, these results may be contextualized within the framework of the value known as familismo. If one considers people with mental disorders to be viewed as persons that may fail to meet their “family obligations” (i.e., they are unable to provide material and emotional support to the family), they may eventually become a “burden” on their relatives and be subject to highly stigmatizing attitudes.55 Furthermore, our findings in regards to the role of women with mental illness within the family are interesting, and have a clear connection with machismo as mentioned above. Namely, women reported they could be homemakers and take care of their siblings or parents, but had difficulty becoming mothers or moving to homes of their own.40

This review has several potential limitations. First, our search strategy did not specifically include terms corresponding to culture-specific descriptors of distress (i.e., nervios, problemas emocionales, debilidad, or flojera), and thus may have missed studies addressing the cultural expression of stigma toward mental illness in this region. Similarly, by using broad search terms such as culture or Latin America for our database search, we may have missed studies on specific regions or ethnicities (e.g., Argentinean or Quechua Culture). Additionally, we incorporated diverse studies with different conceptual and methodological frameworks, which made them difficult to synthesize and compare. Most quantitative studies in our review used small convenience samples, so that findings were specific to certain subgroups and may not apply to all group members from one country, province, or region. Finally, the choice of stigma measure also varied from study to study, thus potentially undermining identification of cogent, culturally specific stigma constructs.

Considering the importance of sociocultural characteristics in stigma, we recommend developing or validating instruments about stigma that consider its cultural aspects. We believe that a useful and interesting method to adapt and validate “culture-specific” stigma instruments has been proposed by Yang et al.11 These authors suggest administering quantitatively based stigma instruments to qualitatively collect data on stigma. This approach allows for the development of “culture-specific measurement modules” which take into account the sociocultural characteristics of the local community in which the instrument is applied, and which may lead to better prediction of outcomes of interest (e.g., psychological symptoms).

The results discussed in this review, in terms of the cultural aspects of different actors included in the process of stigma, could contribute to the creation and implementation of anti-stigma interventions in Latin America. To date, no published results about anti-stigma interventions employed in the region have been published.56 Rosen18 has stated that some factors present in developing countries could contribute to a favorable implementation of anti-stigma projects, such as a) retention of social integration; b) social support from community and solidarity; c) the power of family and an extended kinship or communal network; and d) a higher threshold for detecting madness or for labeling a person as “mad.” All of these may facilitate implementation of anti-stigma interventions in Latin America.

In light of the above, we conclude that stigma, in addition to having powerful forms that are shared across cultures, is expressed with important local differences that have meaning in particular Latin American contexts. Thus, an effective approach in the region will require concerted global investment (economic, social, educational, and political) both from powerful stakeholders and from the community at large, as well as the incorporation of dimensions in future stigma assessments and interventions. Development of these new approaches must include suitable strategies to incorporate cultural features relevant to each community. As noted above, the influence of gender issues, the power of family and its dual role as a protective but also discriminatory agent, and the attitudes of benevolence and solidarity observed among community members should be considered for future anti-stigma interventions in Latin America.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (award U19MH095718 pertaining to authors FM, TT, SS, RA, ET, and LHY). The contents of the manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.González Uzcátegui R, Levav I. Reestructuración de la atención psiquiátrica: bases conceptuales y guías para su implementación. Washington: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO). The world health report 2001 - Mental health: new understanding, new hope. Geneva: WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J, et al. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370:1164–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61263-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caldas de Almeida JM, Horvitz-Lennon M. Mental health care reforms in Latin America: an overview of mental health care reforms in Latin America and the Caribbean. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:218–21. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuart H. Fighting the stigma caused by mental disorders: past perspectives, present activities, and future directions. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:185–8. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson RC, Abel WD, White S, Hickling FW. Internalizing stigma associated with mental illness: findings from a general population survey in Jamaica. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2008;23:26–33. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892008000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leiderman EA, Vazquez G, Berizzo C, Bonifacio A, Bruscoli N, Capria JI, et al. Public knowledge, beliefs and attitudes towards patients with schizophrenia: Buenos Aires. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:281–90. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loch AA, Hengartner MP, Guarniero FB, Lawson FL, Wang Y, Gattaz WF, et al. Psychiatrists' stigma towards individuals with schizophrenia. Rev Psiquiatr Clin. 2011;38:173–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Toledo Piza Peluso E, Blay L. Community perception of mental disorders - a systematic review of Latin American and Caribbean studies. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:955–61. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0820-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening EL, Shrout P, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. Am Sociol Rev. 1989;54:400–23. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang LH, Kleinman A, Link BG, Phelan JC, Lee S, Good B. Culture and stigma: adding moral experience to stigma theory. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1524–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang LH, Valencia E, Alvarado R, Link B, Huynh N, Nguyen K, et al. A theoretical and empirical framework for constructing culture-specific stigma instruments for Chile. Cad Saude Colet. 2013;21:71–9. doi: 10.1590/s1414-462x2013000100011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang LH, Thornicroft G, Alvarado R, Vega E, Link BG. Recent advances in cross-cultural measurement in psychiatric epidemiology: utilizing ‘what matters most’ to identify culture-specific aspects of stigma. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;3:494–510. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdullah T, Brown TL. Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: an integrative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:934–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrés-Hyman RC, Ortiz J, Aãez LM, Paris M, Davidson L. Culture and clinical practice: recommendations for working with Puerto Ricans and other Latinas(os) in the United States. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2006;37:694–701. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larraín J. Identidad chilena. . Santiago de Chile: LOM; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez CF, Rodriguez JK. Four keys to Chilean culture: authoritarianism, legalism, fatalism and compadrazgo. Asian J Lat Am Stud. 2006;19:43–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen A. Destigmatizing day-to-day practices: what developed countries can learn from developing countries. World Psychiatry. 2006;5:21–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delevati DM, Palazzo LS. Atitudes de empresários do sul do Brasil em relação aos portadores de doenças mentais. J Bras Psiquiatr. 2008;57:240–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Des Courtis N, Lauber C, Costa CT, Cattapan-Ludewig K. Beliefs about the mentally ill: a comparative study between healthcare professionals in Brazil and in Switzerland. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:503–9. doi: 10.1080/09540260802565125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ronzani TM, Higgins-Biddle J, Furtado EF. Stigmatization of alcohol and other drug users by primary care providers in Southeast Brazil. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:1080–4. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fresán A, Robles-Garcia R, de Benito L, Saracco Alvarez RA, Escamilla R. Desarrollo y propiedades psicométricas de un instrumento breve para evaluar el estigma de agresividad en la esquizofrenia. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2010;38:340–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peluso ÉT, Blay SL. Public stigma and schizophrenia in São Paulo city. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2011;33:130–6. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462011000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fresán A, Robles R, Cota M, Berlanga C, Lozano D, Tena A. Actitudes de mujeres estudiantes de psicología hacia las personas con esquizofrenia: relación con la percepción de agresividad y peligrosidad. Salud Ment. 2012;35:215–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robles-Garcia R, Fresan A, Berlanga C, Martinez N. Mental illness recognition and beliefs about adequate treatment of a patient with schizophrenia: association with gender and perception of aggressiveness-dangerousness in a community sample of Mexico City. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2012;59:811–8. doi: 10.1177/0020764012461202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hickling FW, Robertson-Hickling H, Paisley V. Deinstitutionalization and attitudes toward mental illness in Jamaica: a qualitative study. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2011;29:169–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin D, Andreoli SB, Pinto RM, Barreira TM. Living conditions of people with psychotic disorders living in slums in Santos, Southeastern Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45:693–9. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102011000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flores Reynoso S, Medina Dávalos R, Robles García R. Estudio de traducción al espaãol y evaluación psicométrica de una escala para medir el estigma internalizado en pacientes con trastornos mentales graves. Salud Ment. 2011;34:33–339. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vázquez GH, Kapczinski F, Magalhaes PV, Cordoba R, Lopez Jaramillo C, Rosa AR, et al. Stigma and functioning in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2011;130:323–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mileva VR, Vazquez GH, Milev R. Effects, experiences, and impact of stigma on patients with bipolar disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:31–40. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S38560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mora-Ríos J, Ortega-Ortega M, Natera G, Bautista-Aguilar N. Auto-estigma en personas con diagnóstico de trastorno mental grave y su relación con variables sociodemográficas, clínicas y psicosociales. Acta Psiquiatr Psicol Am Lat. 2013;59:147–58. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jorge MSB, Bezerra MLMR. Inclusão e exclusão social do doente mental no trabalho: representações sociais. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2004;13:551–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Araújo TCBC, Moreira V, Cavalcante FS., Junior Sofrimento de Sávio: estigma de ser doente mental em Fortaleza. Fractal Rev Psicol. 2008;20:119–28. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robillard C. The gendered experience of stigmatization in severe and persistent mental illness in Lima, Peru. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:2178–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lolich M, Vázquez G, Leiderman EA. Primer episodio psicótico en trastorno bipolar: diferenciación clínica e impacto funcional en una muestra argentina. Vertex. 2010;21:418–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loch AA. Stigma and higher rates of psychiatric re-hospitalization: São Paulo public mental health system. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2012;34:185–92. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462012000200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loch AA, Wang YP, Guarniero FB, Lawson FL, Hengartner MP, Rössler W, et al. Patterns of stigma toward schizophrenia among the general population: a latent profile analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60:595–605. doi: 10.1177/0020764013507248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chuaqui J. El estigma en la esquizofrenia. Cienc Soc Online. 2005;2:45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uribe Restrepo M, Mora OL, Cortés Rodríguez AC. Voces del estigma Percepción de estigma en pacientes y familias con enfermedad mental. Univ Med. 2007;48:207–20. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner LC, Torres-González F, Geidel AR, King MB. Existential questions in schizophrenia: perception of patients and caregivers. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45:401–8. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102011000200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mora-Ríos J, Bautista-Aguilar N, Natera G, Pedersen D. Adaptación cultural de instrumentos de medida sobre estigma y enfermedad mental en la Ciudad de México. Salud Ment. 2013;36:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pescosolido BA, Medina TR, Martin JK, Long JS. The “backbone” of stigma: identifying the global core of public prejudice associated with mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:853–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thornicroft G. Shunned: discrimination against people with mental illness. . New York: Oxford University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corrigan PW, Rafacz J, Rüsch N. Examining a progressive model of self-stigma and its impact on people with serious mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189:339–43. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alonso J, Buron A, Rojas-Farreras S, de Graaf R, Haro JM, de Girolamo G, et al. Perceived stigma among individuals with common mental disorders. J Affect Disord. 2009;118:180–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rusch N, Corrigan PW, Wassel A, Michaels P, Larson JE, Olschewski M, et al. Self-stigma, group identification, perceived legitimacy of discrimination and mental health service use. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:551–2. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong C, Davidson L, Anglin D, Link B, Gerson R, Malaspina D, et al. Stigma in families of individuals in early stages of psychotic illness: family stigma and early psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3:108–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2009.00116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Link BG, Struening E, Kaczynski R, Gonzalez J, et al. Perceived stigma and depression among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:535–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hickling FW. Catalyzing creativity: psychohistoriography, sociodrama and cultural therapy. In: Hickling FW, Sorel E, editors. Images of psychiatry: the Caribbean. Kingston: University of the West Indies; 2005. pp. 241–72. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hickling FW. Sociodrama in the rehabilitation of chronic mentally ill patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40:402–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.40.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Crane RS, Spielberger CD. Attitudes of Hispanic, Black, and Caucasion university students toward mental illness. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1981;3:241–53. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hinshaw SP, Stier A. Stigma as related to mental disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:367–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paro HB, Daud-Gallott RM, Tibério IC, Pinto RM, Martins MA. Brazilian version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy: psychometric properties and factor analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:73. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mascayano F, Toso-Salman J, Sia KJ, Escalona A, Alvarado R, Yang LH. ‘What matters most’ towards severe mental disorders in Chile: a theory-driven, qualitative approach. Rev Fac Cien Med Univ Nac Cordoba, Forthcoming. 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arriagada I. Familias latinoamericanas: diagnóstico y políticas públicas en los inicios del nuevo siglo. Washington: UN-CEPAL; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mascayano F, Schilling S, Tapia E, Gallo V, Abeldaão A. Programas para reducir el estigma hacia la enfermedad mental: lecciones para Latinoamérica. . In: Fernández R, Enders J, Burrone S, editors. Experiencias y reflexiones en salud mental comunitaria. Córdoba: Conicet; 2014. pp. 257–86. [Google Scholar]