Abstract

This study aims to evaluate the antiviral role of nucleic acid-based agonists for the activation of toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathways, and its protective role in respiratory influenza A virus infections. TLR-3 is expressed on myeloid dendritic cells, respiratory epithelium, and macrophages, and appears to play a central role in mediating both the antiviral and inflammatory responses of the innate immunity in combating viral infections. Influenza viruses can effectively inhibit the host's ability to produce interferons, and thereby suppress the immune system's antiviral defence mechanisms. Poly ICLC is a synthetic double stranded RNA comprising of polyriboinosinic-poly ribocytidylic acid (Poly IC) stabilized with l-lysine (L) and carboxymethylcellulose (C). Poly ICLC and liposome-encapsulated Poly ICLC (LE Poly ICLC) are TLR-3 agonists and are potent inducer of interferons and natural killer cells. Intranasal pre-treatment of mice with Poly ICLC and LE Poly ICLC provided high level of protection against lethal challenge with a highly lethal avian H5N1 influenza (HPAI) strain (A/H5N1/chicken/Henan clade 2), and against lethal seasonal influenza A/PR/8/34 [H1N1] and A/Aichi/2 [H3N2] virus strains. The duration of protective antiviral immunity to multiple lethal doses of influenza virus A/PR/8/34 virus had been previously found to persist for up to 3 weeks in mice for LE Poly ICLC and 2 weeks for Poly ICLC. Similarly, pre-treatment of mice with CpG oligonucleotides (TLR-9 agonist) was also found to provide complete protection against influenza A/PR/8/34 infection in mice. RT-PCR analysis of lung tissues of mice treated with Poly ICLC and LE Poly ICLC revealed upregulation of TLR-3 mRNAs gene expression. Taken together, these results do support the potential role of TLR-3 and TLR-9 agonists such as Poly ICLC and LE Poly ICLC in protection against lethal seasonal and HPAI virus infection.

Keywords: Toll-like receptor, Signaling pathway, Agonists, Protection, Influenza virus, Liposomes

1. Introduction

The innate immune system plays a central role in the detection of invading viral pathogens, and responds by activating inflammatory and antiviral defence mechanisms to combat the viral agents. To evade these defence machanisms, the influenza viruses are known to circumvent the potent antiviral interferon action by inhibiting the interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3), and the general interferon signaling pathway [1]. The viruses achieve this in part through their double stranded RNA (ds RNA) binding protein called non-structural protein-1 (NS-1) [1]. By doing so, influenza viruses can replicate unabated in the host's respiratory tract.

During influenza viral replication, single stranded (ss RNA) and ds RNA are intermediate molecules which are recognized by the toll-like receptors (TLRs) which are expressed by cells of the innate immunity including dendritic cells, natural killer cells and macrophages [2] as well as on respiratory epithelium and elsewhere. Toll-like receptors are transmembrane signaling proteins which are designed to specifically recognize various proteins, carbohydrates, lipids and nucleic acids of invading microorganisms. When activated, they trigger immune and inflammatory responses to respond to these infectious agents.

There are four known toll-like receptors which are found in mammalians cells and which recognize nucleic acids. These are TLR-3, TLR-7, TLR-8 and TLR-9 and these are found in the endosomal membranes [2]. Since these nucleic acid-recognizing TLRs regulate the induction of type I interferon and other antiviral gene functions, they are rationale targets for antiviral drug development. Previous study had demonstrated that TLR-3 contributes to the immune response of respiratory epithelial cells to influenza and ds RNA [3]. The molecular mechanism of this immune enhancement is generally believed to be mediated through mitogen-activated protein kinases, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling and the TLR-3 associated adaptor molecule TRIF [3].

This paper outlines the antiviral activity of two TLR agonists and examines their applications in inducing protective antiviral immunity against influenza viruses, including seasonal and avian strains. Poly ICLC is a synthetic ds RNA condensed with poly-l-lysine and carboxymethylcellulose, and is a known TLR-3 agonists [4]. The X-ray crystal structure of the poly IC:TLR-3 receptor signaling complex has been determined [4]. Since TLR-3 activation by ds RNA results in induction of type I interferons, it follows that Poly ICLC, when delivered in liposomes to the endosomal membrane location, may strengthen the host antiviral defence against influenza virus by priming the interferon levels and, therefore, reversing the interferon knockdown by the viruses. In addition, oligonucleotides containing unmethylated CpG motifs, a TLR-9 agonist [5], are evaluated as stand alone immunomodulating antiviral agents.

2. Materials and methods

Poly ICLC, and oligonucleotides containing unmethylated CpG motifs used in this study were supplied by Oncovir Inc. (Washington, DC) and Oligos Etc Inc. (Wilsonville, OR), respectively. The method of preparation and lipid compositions of liposome-encapsulated poly ICLC have been previously described [6].

2.1. RT-PCR

TLR-3 primers were procured from Applied Biosystems (ABI, Streetsville, ON). Mice were pre-treated with two intranasal doses of Poly ICLC, LE Poly ICLC (1 mg/kg body weight), sham liposomes or PBS given at 48 h apart. At 4, 24, 48 and 72 h post-drug treatment, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and the lungs were aseptically removed and homogenized in Trizol. Total RNA was extracted from lung tissues by Trizol method (Invitrogen). One μg of RNA was used for DNase I (Fermentas) digestion before doing RT (reverse transcription) to make 1st strand cDNA. RT was performed using high capacity cDNA RT kit with random primers (ABI). Thermal profile for the RT step was as follows: 25 °C for 10 min (hold); 37 °C for 120 min (hold); 85 °C for 3 s (hold). Real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan probe-based detection (ABI) that was run on an ABI Fast 7500 System. TaqMan Gene Expression assay (ABI) consists of two unlabelled PCR primers and a FAM dye labelled TaqMan MGB (minor groove binder) probe. The PCR step was as follows: 95 °C for 20 s for enzyme activation, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 3 s, annealing and extension at 60 °C for 30 s. β-Actin was used as an internal control to normalize the expression of target genes. Comparative Ct method for relative quantitation was used to calculate fold changes. Serial dilutions of different inputs of target and reference genes were performed to verify that efficiencies of target and reference are approximately equal (data not shown). Data analysis was performed using 7500 software v2.0 (ABI).

2.2. Pre-treatment study

Poly ICLC and CpG oligonucleotides (CpG ODN), whether unencapsulated or encapsulated in liposomes were administered intranasally into 6–7-week-old (20 g body weight) Balb/c female mice. For the prophylaxis of influenza virus infection, groups of mice (8–10 animals per group) were given two doses of free or liposomal poly ICLC (1 mg/kg body weight) 48 h apart by the intranasal route. The volume of the inoculum used was 50 μl. At various days post-drug treatment, the mice were intranasally challenged with either 10 LD50 of influenza A/PR/8/34, or with 1-10 LD50 of influenza A/H5N1/chicken/Henan viruses. The animals were then monitored daily for symptoms of infection, body weights and survival. At day 14 post-infection, the number of mice which survived the virus infection in each group was recorded.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The survival patterns of the control and treated mice were graphed using the Log-rank test (GraphPad Prism version 4.01, San Diego, CA). The survival of the various test groups were compared to the control groups using the Log-rank test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of Poly ICLC and LE Poly ICLC on TLR-3 mRNA expression in lungs

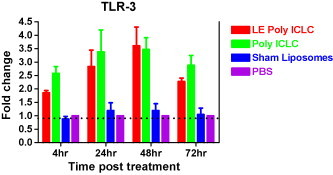

The effect of poly ICLC and LE Poly ICLC on the TLR-3 expression in the lungs of mice intranasally pre-treated with these drugs were determined by RT-PCR (Fig. 1 ). Both Poly ICLC and LE Poly ICLC were found to up-regulate TLR-3 mRNA expression in the lung tissues (Fig. 1). Increased TLR-3 expression was detected as early as 4 h post-drug administration, and was still pronounced at 72 h post-drug administration. In contrast, sham liposomes (empty liposomes without poly ICLC) did not have any effect on TLR-3 expressions in the lungs. The magnitude of TLR-3 up-regulation was slightly higher in the Poly ICLC group for the 4, 24 and 72 h time points compared to the LE Poly ICLC, whereas LE Poly ICLC TLR-3 upregulation was higher compared to the Poly ICLC for the 48 h. The differences between Poly ICLC and LE poly ICLC on TLR-3 expression were not significant statistically. Similar increases in TLR-3 expression were also observed in the Poly ICLC and LE Poly ICLC groups in the spleens of mice but the increases were lower in magnitude and shorter in duration compared to the levels obtained in the lungs (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

TLR-3 mRNA expression in the lungs of mice which received two intranasal administered doses of Poly ICLC, LE Poly ICLC (1 mg/kg body weight), sham liposomes and PBS were analyzed using qRT-PCR as described in Section 2. Results were normalized to β-actin as endogenous control, and are shown as fold increases relative to the PBS control group. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

3.2. The antiviral efficacy of Poly ICLC and LE Poly ICLC (TLR-3 agonists) against seasonal and avian strains of influenza A viruses

Using established lethal influenza infection murine models previously described [6], the protective activity of poly ICLC and LE poly ICLC against the various influenza A strains were determined by assessing the survival rates at day 14 post-infection with 10 LD50 dose of the influenza viruses (Table 1 ). The results summarized show that both Poly ICLC and LE Poly ICLC were highly effective in the protection of mice against both seasonal and avian influenza viruses (Table 1). Pre-treatment of mice with Poly ICLC or LE poly ICLC were found to be more efficacious than pre-treatment with exogenously administered IFN-α or IFN-γ against influenza A/PR/8/34. The data from these studies suggest that the prophylactic protection provided by Poly ICLC and LE poly ICLC is broad-spectrum, effective and protects against H1N1, H3N2 and H5N1 strains.

Table 1.

Prophylactic activity of Poly ICLC, LE Poly ICLC and IFNs against various strains of influenza A viruses in mice.

| Group | Influenza strain | LD50 | % Survival vs. control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly ICLC | A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) | 10 | 100% vs. 0% |

| A/Aichi/2 (H3N2) | 10 | 100% vs. 0% | |

| Henan/2005 (H5N1) | 10 | ND | |

| LE Poly ICLC | A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) | 10 | 100% vs. 0% |

| A/Aichi/2 (H3N2) | 10 | 100% vs. 0% | |

| Henan/2005 (H5N1) | 1 | 100% vs. 50% | |

| Henan/ | 10 | 67% vs. 0% | |

| IFN-α | A/PR/8/34 | 10 | 50% vs. 0% |

| IFN-γ | A/PR/8/34 | 10 | 50% vs. 0% |

The duration of protection provided by Poly ICLC and LE poly ICLC was previously reported [6]. LE Poly ICLC provided 100% protection against 10 LD50 influenza A/PR/8/34 when pre-treatment was given for up to 21 days prior to virus challenge. In comparison, pre-treatment with Poly ICLC was 100% protective when given up to 7 days prior to virus challenge, and it provided 80% protection when given at 14 days prior to virus challenge [6]. The longer duration of LE Poly ICLC compared to Poly ICLC was assumed to be attributable to liposome delivery and gradual release of the Poly ICLC from the liposomes. This remains to be confirmed.

3.3. The antiviral activity of CpG oligos (TLR-9 agonist) against influenza A/PR/8/34 in mice

In a study evaluating the efficacy of CpG ODN against influenza, mice were given 5 μg of a CpG ODN 4 days prior to infection with a lethal dose of influenza A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) (Fig. 2 ). Using this model, mice pre-treated with CpG ODN and liposome-encapsulated CpG ODN were completely protected (100% survival rates at day 14 post-infection) against the otherwise lethal virus challenge. Studies will be carried out to determine whether the incorporation of CpG ODNs in liposomes would confer a longer window of protection compared to unencapsulated CpG ODNs.

Fig. 2.

Efficacy of CpG ODN prophylaxis against influenza viral challenge. Mice were intranasally given 5 μg (0.25 mg/kg body weight) of free or liposome-encapsulated CpG ODN (Lip-CPG ODN) 4 days prior to infection with influenza A/PR/8/34. Liposomes were composed of dimyristoltrimethylammonium propane/cholesterol/dioleylphosphatidyl choline (molar ratio of 25:50:25). Mice (n = 5) were monitored daily for appearance, weight and survival. Graph shows the percentage of mice surviving 14 days after challenge.

4. Conclusion

The results presented affirm the antiviral role of nucleic acid-based TLR agonists such as Poly ICLC and CpG ODNs for the broad-spectrum protection against various seasonal and avian influenza A viruses. The activation of the TLR signaling pathway results in the stimulation of both innate and adaptive immune responses and may be partially responsible for the antiviral state against influenza infections. Influenza viruses are highly effective and adaptable infectious agents which can overcome antiviral therapy by developing drug resistance, and by overcoming the host's immune defence mechanisms. Conventional anti-influenza drugs target the virus structure, and they are susceptible to the emergence of drug resistance. Animal studies suggest that activation of TLR signaling pathway by TLR agonists provides protection not only against influenza virus infections, but also respiratory syncytial virus [7], SARS-CoV [8], and hepatitis B [9], among others. The activation of the toll-like receptor signaling pathway may represent an effective broad-spectrum strategy against these viruses. This approach targets the cells of the innate immune system and hence, is less likely to result in drug resistance. In addition, it provides an effective means to enhance and/or restore interferon production during viral replication. In summary, TLR agonists may represent an affective and broad-spectrum antiviral strategy to combat influenza viruses which are unpredictable and ever changing.

References

- 1.Talon J., Horvath C.M., Polley R., Basler C.F., Muster T., Palese P. Activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 is inhibited by the influenza virus NS1 protein. J Virol. 2000;74:7989–7996. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.7989-7996.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sen G.C., Sarkar S.N. Transcriptional signaling by double stranded RNA: role of TLR3. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guillot L., Goffic R.L., Bloch S., Escriou N., Akia S., Chignard M. Involvement of toll-like receptor 3 in the immune response of lung epithelial cells to double stranded RNA and influenza A virus. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5571–5580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu L., Botos I., Wang Y., Leonard J.N., Shiloach J., Segal D.M. Structural basis of toll-like receptor 3 signaling with double stranded RNA. Science. 2008;320:379–381. doi: 10.1126/science.1155406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krieg A.M. Antiinfective applications of toll-like receptor 9 agonists. Proc Am Thorac Society. 2007;4:289–294. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-021AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong J.P., Christopher M.E., Salazar A.M., Dale R.M.K., Sun L.-Q., Wang M. Nucleic acid-based antiviral drugs against seasonal and avian influenza viruses. Vaccine. 2007;25:3175–3178. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnard D.L., Day C.W., Bailey K., Heiner M., Montgomery R., Lairidsen L. Evaluation of immunomodulators, interferons, and known in vitro SARS-coV inhibitors for inhibition of SARS-coV replication in BALB/c mice. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2006;17:275–284. doi: 10.1177/095632020601700505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerrero-Plata A., Baron S., Poast J.S., Adegboyega P.A., Casola A., Garofalo R.P. Activity and regulation of alpha interferon in respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus experimental infections. J Virol. 2005;79:10190–10199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10190-10199.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isogawa M., Robek M.D., Furuichi Y., Chisari F.V. Toll-like receptor signaling inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in vivo. J Virol. 2005;79:7269–7272. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.7269-7272.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]