Abstract

9-[2-(Thiophosphonomethoxy)ethyl]adenine 3 and (R)-9-[2-(Thiophosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine 4 were synthesized as the first thiophosphonate nucleosides bearing a sulfur atom at the α-position of the acyclic nucleoside phosphonates PMEA and PMPA. Thiophosphonates S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 were evaluated for in vitro activity against HIV-1 (subtypes A to G), HIV-2 and HBV-infected cells, and found to exhibit potent antiretroviral activity. We showed that their diphosphate forms S-PMEApp 5 and S-PMPApp 6 are readily incorporated by wild-type (WT) HIV-1 RT into DNA and act as DNA chain terminators. Compounds 3 and 4 were evaluated for in vitro activity against a broad panel of DNA and RNA viruses and displayed beside HIV a moderate activity against herpes simplex virus and vaccinia viruses. In order to measure enzymatic stabilities of the target derivatives 3 and 4, kinetic data and decomposition pathways were studied at 37 °C in several media.

Keywords: Modified nucleotide, Thiophosphonate, Antiviral activity, HIV, HBV

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; RT, reverse transcriptase; NRTIs, nucleoside RT inhibitors; NtRTIs, nucleotide RT inhibitors; dNTP, deoxynucleotide; ANPs, acyclic nucleoside phosphonates; PMEA, 9-[2-phosphonomethoxyethyl]adenine; (R)-PMPA, (R)-9-[2-phosphonomethoxypropyl]adenine; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; TCID50, 50% tissue culture infectious dose; MOI, multiplicity of infection

Graphical abstract

Highlights

► The RT of HIV is an important target for antiretroviral drugs such as nucleosi(ti)de RT inhibitors. ► Two nucleotides (ANP) are currently used in HIV/HBV therapy: Adefovir (Hepsera) and Tenofovir (Viread). ► We have designed, synthesized and tested new ANPs: α-thiophosphonates named S-PMEA and S-PMPA. ► α-thiophosphonates display potent activity against HIV-1, clinical HIV-1 isolates, HIV-2 and HBV. ► S-PMEApp and S-PMPApp are potent inhibitors and readily incorporated by WT HIV-1 RT.

1. Introduction

The reverse transcriptase (RT) of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) converts the single-stranded viral genomic RNA into double-stranded DNA, which is then integrated into cellular DNA. Thus, RT plays a key role in the viral life cycle and is therefore an important target for antiretroviral drugs such as nucleoside (NRTI) and nucleotide (NtRTI) RT inhibitors [1]. During RT-mediated conversion of viral genomic RNA into proviral DNA, nucleoside and nucleotide analogs can fool RT which can use their 5′-triphosphate form as a substrate. Because these analogs lack a 3′-OH group, DNA chain termination occurs and accounts for an antiretroviral effect.

The acyclic nucleoside phosphonates (ANPs) [2], [3] belong to NtRTIs and contain a stable phosphonate group. Therefore, NtRTIs require only two phosphorylation steps to be converted into their diphosphate active form [4]. Hence, NtRTIs bypass the often rate-limiting nucleoside-kinase step that is known to moderate the activity of NRTIs [5]. To date, only two ANPs have been approved as antiretroviral drugs. Adefovir [9-(2-Phosphonomethoxyethyl)adenine, PMEA] was originally developed for its potential in the treatment of HIV, but its prodrug adefovir dipivoxil proved to be nephrotoxic [6] at the dosage required to efficiently inhibit HIV replication. However, adefovir was subsequently approved for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infections at a lower dosage of administration [3]. Tenofovir [(R)-9-(2-Phosphonomethoxypropyl)-adenine, (R)-PMPA [7], referred hereinafter as PMPA], administered as the prodrug tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, is nowadays one of the most widely prescribed anti-HIV drugs in the US and Europe. Recently, tenofovir was also approved for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B [8], [9].

To widen the antiviral spectrum of ANPs [3], various structural modifications of PMEA and PMPA have been performed, including structural diversity at both the side chain [10], [11] and the heterocyclic moiety of these drugs [2], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. Little attention has been given to explore the phosphonate moiety modifications, and efforts were mainly focused on prodrug synthesis [17], [18]. Therefore, we decided to explore the different modifications of the phosphonate group and we designed the substitution of one of the oxygen atoms bearing by the phosphorus by several groups and atoms. In 2006, we developed an original method to synthesize an H-phosphinate intermediate [19] that can easily serve as a precursor to generate phosphorus-modified nucleotides. This key step was first applied to synthesize nucleoside α-boranophosphonate [19], [20], [21] and nucleoside α-selenophosphonate (unstable compounds, data not published) derived from PMEA and PMPA.

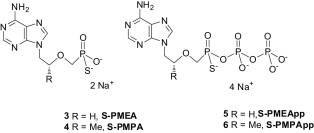

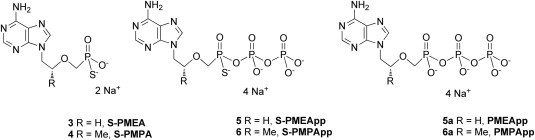

Here, we report the synthesis of novel PMEA and PMPA derivatives bearing a sulfur atom at the α-position of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates. α-Thiophosphonates S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 (Fig. 1 ) exhibit robust antiretroviral activity in cells infected by HIV-1 (LAI strain, and viral isolates from subtypes A to G), HIV-2 as well as HBV. To confirm the mechanism of action of these novel compounds on the viral polymerase, we explored in vitro drug susceptibility of recombinant wild-type (WT) HIV-1 RT from subtype B to the diphosphate forms S-PMEApp 5 and S-PMPApp 6 (Fig. 1) using steady-state kinetic analyses. In addition, the antiviral potential of the compounds 3 and 4 was evaluated by monitoring the reduction of the cytopathic effect of a broad panel of DNA and RNA viruses. Then, we evaluated the stability of our compounds 3 and 4 under conditions mimicking biological fluids. These novel antiviral nucleoside α-thiophosphonates are patented by us [22].

Fig. 1.

Structure of thiophosphonates S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 and their diphosphate forms S-PMEApp 5 and S-PMPApp 6, and the structure of the diphosphate forms PMEApp 5a and PMPApp 5b derived from PMEA and PMPA.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

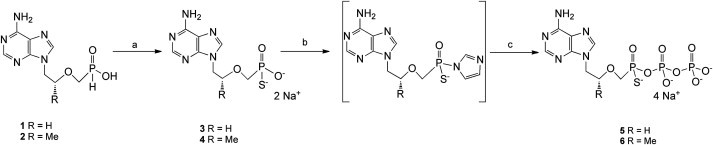

Thiophosphonates S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 are prepared in five steps. The four first steps were previously published [19] for the synthesis of α-boranophosphonate nucleosides and are briefly described here. The first step consists in specifically substituting adenine in order to obtain 9-(2-hydroxyethyl)adenine for the S-PMEA series and (R)-9-(2-hydroxypropyl)adenine for the S-PMPA series. Intermediates are then coupled by nucleophilic substitution to diethyl[[(p-toluenesulfonyl)oxy]methyl]phosphonate, prepared beforehand, to lead to the corresponding diethylphosphonates. Diethylphosphonates are reduced to phosphines by means of lithium aluminum hydride and trimethylsilyl chloride in anhydrous THF at −78 °C. Then oxidation of the corresponding phosphines, in the presence of hydrogen peroxide in a water-THF mixture, lead, with a quantitative yield, to the key intermediates H-phosphinates 1 and 2 (Scheme 1 ).

Scheme 1.

Synthetic Pathway for the Synthesis of compounds 3, 4, 5 and 6. Reagents and conditions: (a) BSA, S8/CS2/pyridine, pyridine, rt, 1 h 30 min; then H2O, then dowex Na+ exchange after purification. (b) Carbonyldiimidazole, DMF, rt, 4 h; then MeOH; (c) HBu3N+H2PO4−, Bu3N, DMF, rt, 72 h; then dowex Na+ exchange after purification.

Finally, the thiophosphonate derivatives S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 are obtained with yields of 52% and 47% respectively, in the presence of BSA and S8/CS2/pyridine in anhydrous pyridine. After reverse-phase purification, they are dissolved in water and passed over a Dowex 50WX2 ion exchange column (Na+ form) with a quantitative yield.

For the diphosphate forms synthesis, thiophosphonates 3 and 4 were activated by carbonyldiimidazole in DMF at ambient temperature. Intermediates obtained reacted with a solution of 0.5 M tributylammonium pyrophosphate in DMF in the presence of tributylamine, to lead to the thiophosphonate diphosphate derivative 5 named S-PMEApp (17%) and 6 named S-PMPApp (19%) after purification and passage through Dowex ion exchange (Na+). Compound S-PMEApp 5 is obtained as an enantiomeric mixture, compound S-PMPApp 6 is obtained as a diastereoisomeric mixture.

Non-thio phosphonate diphosphates PMEApp 5a and PMPApp 6a, derived from PMEA and PMPA, that served as referenced compounds, were synthesized as described in the literature [15].

2.2. Anti-HIV activity of S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 against wild-type (WT) HIV-1 (subtype B) and cytotoxicity in cells

To evaluate the activity of the target compounds, a cell-based antiviral drug susceptibility assay was performed using subtype B WT HIV-1 (LAI, IIIB) and HIV-2 (ROD) (Table 1 ). CEM are treated with increasing concentrations of S-PMEA 3, S-PMPA 4, and reference compounds PMEA or PMPA, and in vitro infected with 100 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious doses) of HIV-1 (IIIB) and HIV-2 (ROD). T-lymphocyte H9 cells and activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) are treated with increasing concentrations of S-PMEA 3, S-PMPA 4, and reference compounds PMEA or PMPA, and in vitro infected, respectively with 125 and 100 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious doses) of HIV-1 (LAI). Similar experiments were performed in H9 cells infected with 6250 TCID50 of HIV-1 (LAI) in order to evaluate the impact of viral load on the anti-HIV activity of the thiophosphonates. On day 7 post infection, reverse transcriptase (RT) activity in cell culture medium was measured to determine the antiviral properties of the compounds expressed as 50% reduction of viral replication (half maximal effective concentration, EC50) (H9, PBMC) or on day 3 post infection (CEM), virus-induced cytopathicity was microscopically recorded (Table 1). Concomitantly, the antimetabolic effect (50% cytotoxic concentration, CC50) of each compound was evaluated in CEM, H9 as well as in uninfected PBMC cultures.

Table 1.

Antiviral effects and cytotoxicity of S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 and reference compounds PMEA and PMPA, in CEM cells infected by 100 TCID50 of HIV-1(IIIa) or HIV-2(ROD), in H9 cells infected by 125 and 6250 TCID50 of HIV-1-LAI and in activated PBMC infected by 100 TCID50 of HIV-1-LAI.

| Compounds | CEM |

H9 |

PBMC |

PBMC and H9 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (μM)a 100 TCID50 HIV-1(IIIB) |

EC50 (μM)a 100 TCID50 HIV-2(ROD) |

CC50 (μM)b | EC50 (μM)a 125 TCID50 HIV-1-LAI |

EC50 (μM)a 6250 TCID50 HIV-1-LAI |

EC50 (μM)a 100 TCID50 HIV-1-LAI |

CC50 (μM)b | |

| S-PMEA 3 | 16 ± 3.4 | 23 ± 19 | 233 ± 5.3 | 1.9 ± 1.8 | 17 ± 0.8 | 14 ± 10 | >30 |

| PMEA | 5.5 ± 1.7 | 7.0 ± 4.3 | 85 ± 19 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 7.9 ± 4.2 | 3.2 ± 2.1 | >30 |

| S-PMPA 4 | 14 ± 1.6 | 7.9 ± 3.0 | >250 | 0.38 ± 0.10 | 9.7 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 3.9 | >100 |

| PMPA | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 7.1 ± 5.7 | >250 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 8.3 ± 1.7 | 3.4 ± 3.2 | >100 |

CEM: HumanT-Lymphoblastoid cells; H9: human lymphocyte cells; PMBC: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

EC50 or concentration of drug that decreases the HIV replication by 50% (means of EC50 from two blood donors).

CC50 or concentration of drug that reduces the viable cell number by 50% (means of CC50 from two blood donors).

The thiophosphonate compounds S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 display a good activity (EC50 1.9 μM and 0.38 μM, respectively) in H9 cells infected with 125 TCID50. These results show that thiophosphonates are able to penetrate cells, to be phosphorylated and to efficiently inhibit HIV-1 replication (subtype B). Antiviral activity is also observed in CEM and in PBMC cell cultures infected with a similar viral load (100 TCID50), indicating that thiophosphonates are able to inhibit HIV-1 replication in other T-lymphocyte cell cultures as well, including primary cells. However, higher EC50 values are obtained with S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 as well as reference compounds PMEA and PMPA in CEM- and PBMC-infected cells, suggesting that the difference between the two cell types could be attributed to different origin and/or activation states for each cell-type and therefore different phosphorylation properties of NtRTI or cellular uptake. The thiophosphonates are also effective against HIV-2 (Table 1). S-PMPA 4 tends to be somewhat more active than S-PMEA 3. With a 50-fold higher multiplicity of infection (MOI) in H9 cells, activity of thiophosphonates as well as the non-thiophosphonates is affected, as expected, with increased EC50 values from 7- to 25-fold. Thus, these results show that the difference between thio and non-thiophosphonates remained constant independently from the MOI virus input. However, it should be noticed that the standard deviation for a number of EC50 values were rather high, being possibly due to inter-individual variability between PBMC donors, and masking potential subtle differences in antiviral potency between the compounds.

Interestingly, the thiophosphonate modification does not significantly modify the anti-HIV activity of the acyclic nucleoside phosphonate compounds, although S-PMEA 3 tends to display a slightly increased EC50 (1.7- to 4-fold) as compared to PMEA and S-PMPA 4 a 1.2- to 3.5-fold increased EC50 as compared to PMPA. Compounds S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 display cytostatic activity values (CC50) in PBMC, CEM and H9 cells to the same order of magnitude as the reference compounds PMEA and PMPA, indicating that the thiophosphonate modification does not measurably affect the cytotoxicity of target compounds.

2.3. Anti-HIV-1 activity of S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 in cells infected by HIV-1 isolates from subtypes A to G

To evaluate the capacity of the compounds to inhibit the replication of clinically relevant HIV-1 isolates from different clades, a cell-based antiviral drug susceptibility assay was performed with HIV-1 isolates from clades A to G obtained from the NIH AIDS reagent program (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Antiviral effects of S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 and reference compounds PMEA and PMPA in the H9 cells infected by HIV-1 isolates from subtypes A, B, C, D, A/E, F and G.

| Viral isolate | Clade | EC50 (μM)a S-PMEA 3 |

EC50 (μM)a PMEA |

EC50 ratiob (PMEA/S-PMEA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4113 | A | 1.64 ± 1.92 | 17.76 ± 4.23 | 10.8 |

| 2101 | B | 0.49 ± 0.74 | 3.51 ± 0.57 | 7.16 |

| 2056 | B | 3.41 ± 2.73 | 1.02 ± 0.02 | 0.29 |

| 1722 | B | 2.80 ± 1.69 | 1.85 ± 0.19 | 0.66 |

| 2914 | C | 0.49 ± 0.36 | 1.45 ± 1.85 | 2.96 |

| 4110 | C | 0.45 ± 0.47 | 2.74 ± 3.58 | 6 |

| 1649 | D | 2.77 ± 2.01 | 0.32 ± 0.10 | 0.11 |

| 2165 | A/E | 0.30 ± 0.13 | 0.32 ± 0.34 | 1.06 |

| 2338 | F | 0.22 ± 0.16 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.86 |

| 3187 | G | 0.88 ± 0.21 | 0.22 ± 0.11 | 0.25 |

| Viral isolate | Clade | EC50 (μM) S-PMPA 4 |

EC50 (μM) PMPA |

EC50 ratio (PMPA/S-PMPA) |

| 4113 | A | 4.49 ± 0.99 | 5.61 ± 6.34 | 1.25 |

| 2101 | B | 0.47 ± 0.18 | 0.24 ± 0.13 | 0.51 |

| 2056 | B | 0.45 ± 0.58 | 1.25 ± 1.82 | 2.77 |

| 1722 | B | 0.51 ± 0.44 | 0.69 ± 0.05 | 1.35 |

| 2914 | C | 0.38 ± 0.33 | 0.34 ± 0.29 | 0.89 |

| 4110 | C | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.83 ± 0.19 | 1.54 |

| 1649 | D | 0.71 ± 0.12 | 0.10 ± 0.07 | 0.14 |

| 2165 | A/E | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.51 ± 0.31 | 1.5 |

| 2338 | F | 0.20 ± 0.35 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.2 |

| 3187 | G | 0.12 ± 0.11 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 1.25 |

Results are expressed as the EC50 or concentration of drug that decreases the HIV replication by 50%.

EC50 ratio = EC50 (μM) PMEA/EC50 (μM) S-PMEA 3 and EC50 (μM) PMPA/EC50 (μM) S-PMPA 4.

Both S-PMEA and S-PMPA suppressed HIV replication in the submicromolar or low micromolar range (4.49 μM-0.12 μM). Depending the nature of the virus isolate the EC50 values of the thio derivatives were somewhat higher or lower than their corresponding PMEA and PMPA derivatives (compare the EC50 ratios in Table 2). Thus, the novel acyclic nucleoside thiophosphonates not only markedly suppress laboratory HIV-1 strains in cell culture but also a broad variety of clinical isolates in primary PBMC representing the different viral clades.

2.4. Enzyme susceptibility assays using steady-state kinetics

To confirm that compounds bearing a thiophosphonate modification target the reverse transcriptase of HIV-1, the relative efficiencies of incorporation of the thiophosphonate diphosphates S-PMEApp 5 and S-PMPApp 6 and reference compounds PMEApp 5a and PMPApp 6a were addressed using subtype B HIV-1 WT RT in in vitro enzyme susceptibility assay (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Drug susceptibilities of WT HIV-1 RT from subtype B for S-PMEApp 5, S-PMPApp 6, and reference compounds PMEApp 5a and PMPApp 6a.

| IC50 (μM)a S-PMEApp 5 |

IC50 (μM)a PMEApp 5a |

IC50 (μM)a S-PMPApp 6 |

IC50 (μM)a PMPApp 6a |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT RT | 6.8 ± 2.3 | 7.0 ± 2.7 | 13.9 ± 5.4 | 11.3 ± 3.8 |

IC50 values were determined with recombinant RT assayed on activated calf thymus DNA and averaged (±S.D.) for at least three independent experiments.

The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values obtained in this assay show that both thiophosphonate diphosphates S-PMEApp 5 (6.8 μM) and S-PMPApp 6 (13.9 μM) are equally efficient inhibitors as their parent compounds PMEApp 5a (7.0 μM) and PMPApp 6a (11.3 μM). The S-PMEApp 5 and S-PMPApp 6 compounds are thus readily incorporated by HIV-1 RT from subtype B and display pronounced inhibitory properties against HIV-1 WT RT. Moreover, the effect of the sulfur atom is seemingly neutral, as also observed with the compounds 3 and 4 in the virus-infected cells.

2.5. Anti-HBV activity of S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 in cell cultures

Since PMEA and PMPA are clinically approved to inhibit HBV replication in infected patients, the compounds were tested in two cell-based antiviral drug susceptibility assays. The inhibition of WT HBV replication was assessed in HepAD38 and Huh7 cells treated with increasing concentrations of S-PMEA 3, S-PMPA 4 and reference compounds PMEA and PMPA. The amount of viral DNA produced in the cells was quantified to evaluate the antiviral properties of the compounds as the 50% reduction of viral DNA (EC50) (Table 4 ). Concomitantly, the cytotoxic effect of each compound was evaluated as well.

Table 4.

Anti-HBV activities and cytotoxicity in HepAD38 and Huh7 cell cultures of S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 and reference compounds PMEA and PMPA.

| Compound | EC50 (μM)a HepAD38 cells |

EC50 (μM)a Huh7 cells |

CC50 (μM)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-PMEA 3 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | > 150 |

| PMEA | 7.6 ± 0.0 | 6.0 ± 1.0 | > 150 |

| S-PMPA 4 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.0 | > 150 |

| PMPA | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | > 150 |

EC50: effective concentration of compounds inducing a 50% reduction of the level of HBV viral DNA in the culture.

CC50: cytotoxic concentration of compounds inducing a 50% reduction of the cell density.

Similar inhibitory properties are observed for S-PMPA 4 as compared with PMPA in the two assays, with IC50 values of 2.8 and 4 μM, respectively for S-PMPA 4. The S-PMEA 3 derivative tended to be slightly more potent (1.5–2.5 fold) than PMEA irrespective of the cell-type used. These results show that thiophosphonate compounds are effective to inhibit the replication of WT HBV. No cytotoxicity is observed up to 150 μM for all compounds tested.

2.6. Evaluation of S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 against other DNA and RNA viruses in cell culture

To evaluate the antiviral selectivity of the compounds, the antiviral activity testing against a panel of RNA and DNA viruses was performed in cell culture. Coxsackie virus B4, Respiratory Syncytial virus, Influenza A (H1N1 and H3N2 subtype), Influenza B, Parainfluenza-3 virus, Reovirus-1, Sindbis virus, Feline Corona virus, Punta Toro virus, Herpes Simplex virus type 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and 2), Vaccinia virus and Vesicular Stomatitis virus were included in the study (Table 5 ).

Table 5.

Antiviral activities and cytotoxicity of S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 and the reference compounds PMEA and PMPA against several DNA viruses in cell culture.

| Compound | EC50 (μM)a |

Minimum cytotoxic concentration (μM)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herpes simplex virus-1 (KOS) | Herpes simplex virus-1 (TK− KOS ACVr) | Herpes simplex virus-2 (G) | Vaccinia virus | ||

| S-PMEA 3 | 40 ± 0 | 24 ± 2 | 24 ± 1 | 84 ± 6 | >200 |

| PMEA | 89 ± 6 | 20 ± 4 | 20 ± 3 | >200 | >200 |

| S-PMPA 4 | 169 ± 13 | 80 ± 5 | 48 ± 0 | 80 ± 7 | >200 |

| PMPA | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 |

EC50: effective concentration of compounds required to reduce virus-induced cytopathicity by 50%.

Minimum concentration required to cause a microscopically detectable alteration of normal cell morphology.

None of the compounds exhibit cytotoxicity at concentrations as high as 200 μM. No antiviral activity up to 200 μM is observed against any of the RNA viruses tested, i.e. Coxsackie virus B4, Respiratory Syncytial virus, Influenza A and B, Parainfluenza-3 virus, Reovirus-1, Sindbis virus, Feline Corona virus, Vesicular stomatitis virus and Punta Toro virus (data not shown). However, S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 display a similar or better activity against DNA viruses than the reference compounds although the observed EC50 values are rather high but consistent with previously described results [23], [24], [25]. Indeed, S-PMPA 4 is able to inhibit Herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 as well as Vaccinia virus (EC50: 48–169 μM) while the reference compound PMPA exhibits no activity at 200 μM. S-PMEA 3 shows some inhibitory properties against Vaccinia virus in contrast to PMEA. In addition, S-PMEA 3 is as active as PMEA against the thymidine kinase-deficient HSV-1 and against HSV-2 but is slightly more active against wild-type HSV-1. These results confirm that PMPA and PMEA are highly specific for DNA viruses (i.e. encoding a viral DNA polymerase) and in particular for viruses encoding for a viral reverse transcriptase like HIV and HBV. The thiophosphonates S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 mainly display the same specificity as PMEA and PMPA but with somewhat amplified antiviral spectrum for S-PMPA in particular.

2.7. Stability studies

To be effective in vivo, any antiviral compound has to be stable enough to reach the bloodstream and then the infected cell where its target is localized. Therefore, a stability study with S-PMEA 4 and S-PMPA 5 was carried out under conditions mimicking biological fluids, i.e. in complete culture medium (extra-cellular medium) and in cell extracts (intra-cellular medium) in order to evaluate the stability spectrum. The degradation kinetics were followed by analytical HPLC. The apparatus used possesses a specific system for on-line filtration, which makes it possible to inject a protein-rich mixture (cell extracts, culture medium, serum) into the analytical column without prior filtration [26]. For each condition studied, the whole sample was incubated at 37 °C and at each chosen time interval, 50 μL were sampled and directly injected into an analytical HPLC column where the analytical conditions make it possible to visualize and properly separate the starting compound from the degradation products.

The tests under culture medium conditions were carried out with RPMI medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (complete medium) and on extracts of CEM cells. The half-lives were calculated and are displayed in Table 6 .

Table 6.

Stabilities of S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 in various media.

t1/2: half-life of decomposition.

Product 80% intact (degradation into PMEA).

Product 77% intact (degradation into PMPA).

Less than 1% degradation after 24 h.

S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 behave similarly under the conditions tested (complete culture medium and cell extracts). Compound 3 is slowly degraded into a single product, identified as being PMEA by HPLC co-injection. Compound 4 is slowly decomposed into a single product, identified as being PMPA by HPLC co-injection. This conversion is due to a de-sulfuration of the P–S bond into a P–O bond. The difference in behavior observed in complete culture medium (20% degradation after 24 h) and in cell extracts (less than 1% degradation after 24 h) could be explained by the difference in enzymatic content between the two media. As described previously [19], the reference compounds PMEA and PMPA are stable in all tested media.

3. Conclusion

Novel α-thiophosphonate derivatives S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 and their diphosphate forms S-PMEApp 5 and S-PMPApp 6 have been synthesized. Target compounds S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 were screened for their antiviral activity in vitro against HIV-1, HIV-2, HBV and other DNA or RNA viruses in comparison with reference compounds PMEA and PMPA. Compounds 3 and 4 display potent activity against HIV-1 and HIV-2, clinically relevant HIV-1 isolates (clades A to G) and HBV generally to a similar extent as the reference compounds. S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 display a moderate activity against herpes simplex virus and vaccinia virus. The diphosphate forms 5 and 6 are readily incorporated by WT HIV-1 RT providing the molecular basis of their anti-HIV activity. Stability studies of derivatives 3 and 4 in culture media and cell extracts have shown an excellent stability of these derivatives up to 24 h and a unique but slow metabolism pathway in enzymatic nucleophile-enriched media via the conversion of the P–S bond into a P–O bond due to a de-sulfuration.

To conclude, these novel acyclic nucleoside thiophosphonates display promising antiviral activities. Our future work will consist in the improvement of their pharmacokinetic properties by prodrug forms synthesis to make them potential candidates for HIV and HBV therapy.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

The 1H NMR, 13C NMR and 31P NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) spectra were determined with a BRUKER AMX 250 MHz, a BRUKER Avance DPX 400 MHz and a BRUKER Avance III 600 MHz. Chemical shifts are expressed in ppm and coupling constants (J) are in hertz (s = singlet, bs = broad singlet, d = doublet, dd = double doublet, ddd = double–double doublet, t = triplet, dt = double triplet, tt = triple triplet, m = multiplet, dm = double multiplet). FAB High Resolution Mass Spectra (HRMS) were recorded in positive-ion mode on a JEOL SX 102 mass spectrometer using a cesium ion source and a glycerol/thioglycerol matrix; ESI High Resolution Mass Spectra were recorded in the negative-ion mode on a Micromass Q-TOF Waters (Laboratoire de Mesures Physiques RMN, USTL, Montpellier, France). HPLC was performed on a Waters 600E controller system equipped with a 991 photodiode array detector (detection 260 nm), auto-injector 717 and on-line degazer. Eluant A: 0.05 M triethylammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 7.5); eluant B: solution A containing 50% of acetonitrile. A stock solution of triethylammonium bicarbonate buffer TEAB (pH 7.5) 1 M was prepared by addition of dry-ice in a 1 M triethylamine solution in water to reach pH 7.5 and filtered with membrane 0.22 μM GV-type (Millipore). HPLC and FPLC buffers are prepared daily. Analytical reverse phase (RP) chromatography was carried out on a 4.6 × 100 mm Source®15RPC column or a column X-Terra MS C18 (5 μM, 4.6 × 250 mm) + precolumn X-Terra MS C18 (3.5 μM, 3.9 × 20 mm) and samples were eluted at a flow rate of 1 mL/min using a linear gradient 0–100% B in 60 min. Preparative purifications of thiophosphonate and thiophosphonate diphosphate derivatives were achieved on an ÄKTAprime FPLC (Amersham) using respectively a reverse-phase Source®30RPC column (18 × 350 mm) and a DEAE-Sephadex A-25 column (2 × 30 cm) with a linear gradient 0–100% B programmed over a 6 h period with a flow rate of 2 mL/min for thiophosphonate derivatives and over a 10 h period with a flow rate of 1 mL/min for thiophosphonate diphosphate derivatives (detection at 254 nm). Compounds {[2-(6-amino-9H-purin-9-yl)ethoxy]methyl}phosphinic acid 1 and ({[(2R)-1-(6-amino-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl]oxy}methyl)phosphinic acid 2 were synthesized as described previously [19], [22].

4.1.1. General procedure for the synthesis of {[2-(6-amino-9H-purin-9-yl)ethoxy]methyl}phosphonothioic acid (3) and ({[(2R)-1-(6-amino-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl]oxy}methyl)phosphonothioic acid (4)

H-phosphinate (1 eq, 0.194 mmol) was dried over phosphorus pentoxide under vacuum for 5 h then dissolved in anhydrous pyridine (2 mL). N,O-Bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (BSA) (5 eq, 0.972 mmol) was added by syringe and the solution was stirred for about 1 h at room temperature, under argon. A freshly solution of elemental sulfur (2 eq, 0.388 mmol) in CS2/pyridine (1/1, 1 mL) was added, the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min, and quenched with deionized water (5 mL). After the solvents were evaporated under reduced pressure, the residue was purified by reversed-phase column chromatography (linear gradient 0–100% B). Product fractions were collected, evaporated to dryness and lyophilized. Excess triethylammonium bicarbonate was removed by repeated freeze-drying with deionized water. The residue was dissolved in water and eluted on a Dowex 50WX2 column (Na+ exchange) to give the pure compound as disodium salt.

4.1.1.1. {[2-(6-Amino-9H-purin-9-yl)ethoxy]methyl}phosphonothioic acid (3)

1H NMR (D2O) δ: 8.08 (s, 1H, H-8), 7.93 (s, 1H, H-2), 4.23 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H, CH2N), 3.87 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H, CH2O), 3.60 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H, CH2P). 13C NMR (D2O) δ: 152.23, 149.12, 146.98, 141.98, 116.38, 73.01 (d, J CP = 120.0 Hz), 68.57 (d, J CP = 10.6 Hz), 42.27. 31P NMR (D2O) δ: 60.67 (t, J = 5.2 Hz). HRMS (TOF, ESI-) calcd for C8H11N5O3PS (M)− 288.0320, found 288.0347. HRMS (FAB+) calcd for C8H13N5O3PS (M + H)+ 290.0477, found 290.0463. HPLC purity >98%; white powder after freeze-drying. Yield = 52%.

4.1.1.2. ({[(2R)-1-(6-Amino-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl]oxy}methyl)phosphonothioic acid (4)

1H NMR (D2O) δ: 8.16 (s, 1H, H-8), 8.07 (s, 1H, H-2), 4.29 (dd, J = 14.6 Hz and J = 3.1 Hz, 1H, CHaN), 4.10 dd, J = 14.6 Hz and J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, CHbN), 3.95 (m, 1H, CHO), 3.63 (dd, J = 12.6 Hz and J = 5.8 Hz, 1H, CHaP), 3.49 (dd, J = 12.6 Hz and J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, CHbP), 1.05 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (D2O) δ: 152.65, 149.12, 147.25, 142.25, 116.26, 74.46 (d, J CP = 10.7 Hz), 70.89 (d, J CP = 121.1 Hz), 46.39, 14.73. 31P NMR (D2O) d: 61.60 (t, J 4.8 Hz). HRMS (TOF, ESI-) calcd for C9H13N5O3PS (M)− 302.0477, found 302.0465. HRMS (FAB+) calcd for C9H15N5O3PS (M + H)+ 304.0633, found 304.0623. HPLC purity >98%; white powder after freeze-drying. Yield = 47%.

4.1.2. General procedure for the synthesis of ({[({[(Rp/Sp)-2-(6-amino-9H-purin-9-yl)ethoxy]methyl}(sulfanyl)phosphoryl)oxy](hydroxy)phosphoryl}oxy)phosphonic acid (5) and [({[({[(2R,Rp/2R,Sp)-1-(6-amino-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl]oxy}methyl)(sulfanyl)phosphoryl]oxy} (hydroxy)phosphoryl)oxy]phosphonic acid (6)

Thiophosphonate (1 eq, 0.069 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (2 mL) and treated with 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole (4 eq, 0.278 mmol). The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Excess of CDI was decomposed by addition of anhydrous methanol (8 μL) and stirring was continued for 30 min. Anhydrous tri-n-butylamine (50 μL) and tributylammonium pyrophosphate (700 μL of a 0.5 M solution in DMF) were added and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 days. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 5 mL of cold water. The solvent was removed under vacuum, the residue dissolved in water, and the solution applied to a DEAE-Sephadex column (linear gradient 0–100% B). The appropriate fractions were collected, evaporated to dryness and lyophilized. The residue was dissolved in water and passed through a Dowex 50WX2 (Na+ form) column to give the pure compound as tetrasodium salt.

4.1.2.1. ({[({[(Rp/Sp)-2-(6-Amino-9H-purin-9-yl)ethoxy]methyl}(sulfanyl)phosphoryl)oxy](hydroxy) phosphoryl}oxy)phosphonic acid (5)

1H NMR (D2O) δ: 8.40 (s, 1H, H-8), 8.32 (s, 1H, H-2), 4.52 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H, CH2N), 4.10 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H, CH2O), 3.97 (dd, J = 13.8 Hz and J = 4.2 Hz, 1H, CHaP), 3.93 (dd, J = 13.2 Hz and J = 4.8 Hz, 1H, CHbP). 31P NMR (D2O) δ: 62.06 (d, 2 J = 33.0 Hz), −10.94 (d, 2 J = 19.8 Hz), −23.53 (d, 2 J = 33.0 Hz and 2 J = 19.8 Hz). HRMS (TOF, ESI-) calcd for C8H13N5O9P3S (M)− 447.9647, found 447.9656. HPLC purity >99%; white powder after freeze-drying. Yield = 17%.

4.1.2.2. [({[({[(2R,Rp/2R,Sp)-1-(6-Amino-9H-purin-9-yl)propan-2-yl]oxy}methyl)(sulfanyl)phosphoryl]oxy} (hydroxy)phosphoryl)oxy]phosphonic acid (6)

1H NMR (D2O) δ: 1H NMR (D2O) δ: 8.42 (s, 1H, H-8), 8.32 (s, 1H, H-2), 4.52 (dd, J = 14.8 Hz and J = 3.1 Hz, 1H, CHaN), 4.33 (ddd, J = 14.8 Hz, J = 6.6 Hz and J = 2.8 Hz, 1H, CHbN), 4.14 (m, 1H, CHO), 3.99 (m, 1H, CHaP), 3.84 (m, 1H, CHbP), 1.23 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H, CH3). 31P NMR (D2O) δ: 62.18 (d, 2 J = 33.5 Hz), 62.02 (d, 2 J = 33.3 Hz), −10.60 (d, 2 J = 19.9 Hz), −10.96 (d, 2 J = 20.0 Hz), −23.1-(−)23.6 (m). HRMS (TOF, ESI-) calcd for C9H15N5O9P3S (M)− 461.9803, found 461.9802. HPLC purity >99%; white powder after freeze-drying. Yield = 19%.

4.2. Reverse transcriptase assays

4.2.1. HIV-RT plasmid constructions, enzyme preparations and reagents

The recombinant clade B HIV-1 WT RT were co-expressed with HIV-1 protease in Escherichia coli in order to obtain p66/p51 heterodimers, which were later purified using affinity chromatography as described [27]. Enzymes were quantitated by active-site titration before biochemical studies. Activated Calf Thymus DNA was purchased from GE Healthcare. [3H]-labeled deoxythymidine 5′-triphosphate was purchased from Perkin Elmer.

4.2.2. Drug susceptibility assays with recombinant subtype B HIV-1 RT

Standard RT activity was assayed using 250 μg/mL of activated calf thymus DNA. To determine IC50 values for S-PMEApp 5, S-PMPApp 6, PMEApp 5a or PMPApp 6a, reactions were performed with 10 nM (active sites) of HIV-1 RT and 5 μM of each dNTP containing 100 μCi/mmol of 3H-dTTP for 15 min with increasing amounts of inhibitors. Each aliquot was spotted in duplicate on DE81 ion-exchange paper discs, and the discs were washed three times for 10 min in 0.3 M ammonium formate, pH 8.0, two times in ethanol, and dried. The radioactivity bound to the filters was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Values of IC50 are the average from at least three independent experiments.

4.3. Antiviral activity in cells

4.3.1. Cells and viruses

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy donors were isolated and stimulated with 1 μg/mL of phytohemagglutinin-P (PHA-P, Sigma) and 5 IU/mL of human interleukin-2 (IL-2, Invitrogen) for 3 days. PBMCs, CEM and H9 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with antibiotics, and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). The human hepatoma cell line HepAD38 [28], stably transfected by an HBV-expressing construct under the control of tetracyclin, was grown in DMEM/HAM’s F12 (50/50) culture medium supplemented with 10% (FCS), 100 IU/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 400 μg/mL G418 and 0.3 μg/mL tetracycline. The human hepatoma cell line Huh7 was growth in DMEM culture medium supplemented with 10% (FCS), 100 IU/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin. Human embryonic lung HEL, simian kidney Vero, feline kidney CrFK and human cervix carcinoma HeLa cells were propagated in minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 0.075% bicarbonate. The HIV-1-LAI strain was described previously [29]. Viral isolates from clades A, B, C, D, A/E, F and G were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) (KOS and KOS ACV TK-), HSV-2 (G), vaccinia virus, vesicular stomatitis virus, Coxsackie virus B4, respiratory syncitial virus, parainfluenza-3 virus, reovirus-1, Sindbis virus and Punta Toro virus were described elsewhere [19].

4.3.2. Anti-HIV assay in cells

PHA-P-activated PBMC (1.5 × 105 cells) or H9 cells (5 × 105 cells) treated for 30 min by increasing concentrations of S-PMEA 3, S-PMPA 4, and reference compounds PMEA and PMPA (generously provided by Dr Antonin Holý from Prague, Czech Republic) were infected, respectively, with 100 or 125 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious doses) of the HIV-1-LAI strain. Supernatants were collected at day 7 post infection and stored at −20 °C. Viral replication was measured by quantifying reverse transcriptase (RT) activity in cell culture supernatants by use of the RetroSys RT Activity Kit (Innovagen). Cytotoxicity of the compounds was evaluated in uninfected PHA-P-activated PBMC and H9 cells by MTT assay (Sigma) on day 7. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated with another blood donor for PBMCs. Data analyses were performed using SoftMax®Pro 4.6 microcomputer software. Percent of inhibition of RT activity or cell viability were plotted versus compound concentration and fitted with quadratic curves to determine 50% effective concentrations (EC50) and cytotoxic concentrations (CC50).

The methodology of the anti-HIV assays was as follows: human CEM (∼3 × 105 cells/cm3) cells were infected with 100 CCID50 of HIV(IIIB) or HIV-2(ROD)/mL and seeded in 200 μL wells of a microtiter plate containing appropriate dilutions of the test compounds. After 4 days of incubation at 37 °C, HIV-induced CEM giant cell formation was examined microscopically. The 50% effective concentration (EC50) was defined as the compound concentration required to inhibit syncytia formation by 50%. The 50% cytostatic concentration (CC50) was defined as the compound concentration required to inhibit CEM cell proliferation by 50% in mock-infected cell cultures.

4.3.3. Anti-HBV assay in cells

The tetracycline-responsive hepatoma cell line HepAD38, stably transfected with a cDNA copy of the pregenomic RNA of wild-type HBV virus, was used [28]. Withdrawal of tetracycline from the culture medium resulted in the initiation of viral replication. The cells (5 × 105) were seeded in 48-well plates and were induced after 2–3 days for viral production by washing with PBS and were fed with 200 μL culture medium without tetracycline and G418 with or without the antiviral compounds. Medium was changed after 3 days. The antiviral effect was quantified by measuring levels of intracellular viral DNA at day 6 post induction, by a real time quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) method. Total cellular DNA was extracted from the cells by means of a commercial kit. The Q-PCR was performed in a reaction volume of 25 μL using the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix with forward primer (5′-CCG TCT GTG CCT TCT CAT CTG-3′; final concentration: 600 nM), reversed primer (5′-AGT CCA AGA GTY CTC TTA TRY AAG ACC TT-3′; final concentration: 600 nM), and Taqman probe (6-FAM-CCG TGT GCA CTT CGC TTC ACC TCT GC-TAMRA; final concentration 150 nM). The reaction was analyzed using an ABI Prism SDS 7000 apparatus. A plasmid containing the full-length insert of the HBV genome was used to prepare the standard curve. The amount of viral DNA produced in treated cultures was expressed as a percentage of the untreated samples. Compounds that exhibited selective antiviral activity in a first assay were retested to confirm the activity. The cytostatic effect of the various compounds was assessed employing the parent hepatoma cell line HepG2. The effect of the compounds on exponentially growing HepG2 cells was evaluated by means of the MTS method. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 3000 cells/well and were allowed to proliferate for 3 days in the absence or presence of compounds S-PMEA 3, S-PMPA 4, and reference compounds PMEA or PMPA, after which the optical density was measured with a 96-well plate reader and cell density was determined.

For the Anti-HBV assay in the Huh7 cell line, the plasmid pTriEXMod-HBV, which contains 1.1 IU of the HBV genome, enabled after cell transfection the production of pregenomic RNA under the control of the chicken beta actin promoter and therefore triggers HBV DNA synthesis [30]. Huh7 cells (3 × 105) were seeded in 12-well plates and were transfected 1 day post plating with 0.5 μg/well of pTriEXMod-HBV plasmid containing wt HBV genome, using the Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sixty hours post transfection, treatment with increasing concentrations (0, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 μM) of S-PMEA 3, S-PMPA 4, and reference compounds PMEA or PMPA, was started. Medium was changed daily, and drug administration was performed from day 3 to day 8 post transfection. Cells were then lysed for analysis of intracellular viral DNA. HBV DNA was purified from intracellular core particles as described earlier [31], separated on agarose gels, analyzed by Southern Blot hybridization, and quantified after PhosphorImager scanning to determine the inhibitory concentration-50 (IC50) after comparison with standard that is an isogenic wild-type strain or wild-type quasispecies [32]. Cultures were inspected microscopically for alteration of cell morphology.

4.3.4. Antiviral assay against a panel of DNA and RNA viruses

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) (KOS and KOS ACV TK−), HSV-2 (G), vaccinia virus and vesicular stomatitis virus were assayed in HEL cell cultures. Coxsackie virus B4 and respiratory syncytial virus were assayed in HeLa cell cultures. Parainfluenza-3 virus, reovirus-1, Sindbis virus and Punta Toro virus were assayed in Vero cell cultures. Feline corona viruses were assayed in CrFK cell cultures. Cells were grown to confluency in microtiter trays and were inoculated with 100 times the 50% cell culture infective dose. Compounds S-PMEA 3, S-PMPA 4, and reference compounds PMEA or PMPA, were added after a 1 to 2-h virus adsorption period. The virus-induced cytopathic effect (CPE) was recorded microscopically at 3 days post infection and was expressed as percentage of the untreated controls. The 50% effective concentrations (EC50) were derived from graphical plots. The minimal toxic concentration (MTC) was defined as the minimal concentration that resulted in a microscopically detectable alteration of cell morphology. The MTC was determined in uninfected confluent cell cultures that were incubated, akin to the cultures used for the antiviral assays, with serial dilutions of the compounds for the same time period. Cultures were inspected microscopically for alteration of cell morphology.

4.4. Stability studies

4.4.1. Media and preparation of cell extracts

CEM-SS cells extract was prepared as previously described [19], [26]. Briefly, exponentially growing CEM-SS cells were recovered by centrifugation (500g), washed with PBS, and resuspended in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 140 mM KCl, at the concentration of 30 × 106 cells/mL. Cells were lyzed by ultrasonic treatment and cellular debris were removed by centrifugation (10,000g, 20 min). The supernatant containing soluble proteins (3 mg/mL) was stored at −80 °C. Kinetic data of decomposition for S-PMEA 3 and S-PMPA 4 was studied at 37 °C (a) in culture medium (RPMI-1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum), and (b) in total cell extract (CEM-SS cell). For each kinetic study, the compound solution is diluted with a freshly thawed aliquot of the considered medium to obtain a final concentration of 0.1 mM and the mixture is incubated at 37 °C. At the desired time, an aliquot is removed and immediately frozen at −80 °C for further HPLC analysis, as previously described [19].

4.4.2. HPLC analysis

We used a previously described on-line HPLC cleaning method [26]. Studies were performed on a column Nova-pak C18 (4 mm, 3.9 × 150 mm) + precolumn Nova-pack C18 (100 Å) with an on-line filtration system. Samples were eluted using a linear gradient of 0.05 M triethylammonium bicarbonate buffer in 100% water (pH 7.5) (buffer A) to a 0.05 M triethylammonium bicarbonate buffer in 50% acetonitrile (buffer B), programmed over a 60 min period with a flow rate of 1 mL/min and detection at 260 nm. The crude sample (50 mL) is injected into the precolumn and eluted with buffer A during 5 min. Then, the switching valve for connecting the precolumn to the column is activated and a linear gradient from 0% buffer B to 20% over 40 min is applied. The retention times are 25.6 min for S-PMEA 3, 29.5 min for S-PMPA 4, 24.3 min for PMEA, and 27.7 min for PMPA. The amount of remaining parent compound at each time point was used to determine the half-life of the compound. The product of decomposition from parent derivative is determined by comparison with authentic samples and reference compounds.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grant from the French “Agence Nationale de Recherche Contre le Sida et les hépatites virales” (ANRS), by SIDACTION and the K.U. Leuven (GOA 10/014). The authors wish to thank Dr A. Holý for providing the reference compounds. We wish to thank Dr. K. Parra, A. Lebrun and Dr G. Valette (Université Montpellier II, Montpellier, France) for their expertise in conducting NMR experiments and mass spectrometry analysis. We wish to thank Dr P. Clayette (SPI-BIO, CEA, Fontenay-aux-roses, France) for his expertise in conducting antiviral experiments in HIV-infected cells, and Mrs. Leentje Persoons, Frieda De Meyer and Leen Ingels for technical assistance with the antiviral assays.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.06.034.

Contributor Information

Stéphane Priet, Email: Stephane.priet@afmb.univ-mrs.fr.

Karine Alvarez, Email: Karine.Alvarez@afmb.univ-mrs.fr.

Appendix. Supplementary material

References

- 1.De Clercq E. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2010;10:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holy A. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2003;9:2567–2592. doi: 10.2174/1381612033453668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Clercq E., Holy A. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:928–940. doi: 10.1038/nrd1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma P.L., Nurpeisov V., Hernandez-Santiago B., Beltran T., Schinazi R.F. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2004;4:895–919. doi: 10.2174/1568026043388484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins B.L., Srinivas R.V., Kim C., Bischofberger N., Fridland A. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:612–617. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Izzedine H., Harris M., Perazella M.A. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2009;5:563–573. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suo Z., Johnson K.A. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:27250–27258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duarte-Rojo A., Heathcote E.J. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2010;3:107–119. doi: 10.1177/1756283X09354562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenh A.M., Pham P.A. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2010;8:1079–1092. doi: 10.1586/eri.10.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holý A. Collect. Symp. Ser. 2002;5:24–35. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolakova P., Dracinsky M., Masojidkova M., Solinova V., Kasicka V., Holy A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009;44:2408–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holy A., Dvorakova H., Jindrich J., Masojidkova M., Budrinski M., Balzarini J., Andrei G., De Clercq E. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:4073–4088. doi: 10.1021/jm960314q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holy A., Dvorakova H., Masojidkova M. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1995;60:1390–1409. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holy A., Gunter J., Dvorakova H., Masojidkova J., Andrei G., Snoeck R., Balzarini J., De Clercq E. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:2064–2086. doi: 10.1021/jm9811256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holý A., Rosenberg I. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1987;52:2801–2809. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holý A., Votruba I., Tloustova E., Masojidkova M. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 2001;66:1545–1592. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starrett J.E., Jr., Tortolani D.R., Russell J., Hitchcock M.J., Whiterock V., Martin J.C., Mansuri M.M. J. Med. Chem. 1994;37:1857–1864. doi: 10.1021/jm00038a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackman R.L., Ray A.S., Hui H.C., Zhang L., Birkus G., Boojamra C.G., Desai M.C., Douglas J.L., Gao Y., Grant D., Laflamme G., Lin K.Y., Markevitch D.Y., Mishra R., McDermott M., Pakdaman R., Petrakovsky O.V., Vela J.E., Cihlar T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:3606–3617. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barral K., Priet S., Sire J., Neyts J., Balzarini J., Canard B., Alvarez K. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:7799–7806. doi: 10.1021/jm060030y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barral K., Priet S., De Michelis C., Sire J., Neyts J., Balzarini J., Canard B., Alvarez K. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:849–856. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frangeul A., Barral K., Alvarez K., Canard B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3162–3167. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00145-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.B. Canard, K. Alvarez, K. Barral, J.L. Romette, J. Neyts, J. Balzarini, WO/2008/056264, 2008.

- 23.De Clerck E., Sakuma T., Baba M., Pauwels R., Balzarini J., Rosenberg I., Holy A. Antiviral Res. 1987;8:261–272. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(87)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snoeck R., Andrei G., De Clercq E. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1996;15:574–579. doi: 10.1007/BF01709366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balzarini J., Holy A., Jindrich J., Naesens L., Snoeck R., Schols D., De Clercq E. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993;37:332–338. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.2.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puech F., Gosselin G., Lefebvre I., Pompon A., Aubertin A.M., Kirn A., Imbach J.L. Antiviral Res. 1993;22:155–174. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(93)90093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boretto J., Longhi S., Navarro J.M., Selmi B., Sire J., Canard B. Anal. Biochem. 2001;292:139–147. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ladner S.K., Otto M.J., Barker C.S., Zaifert K., Wang G.H., Guo J.T., Seeger C., King R.W. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1715–1720. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.8.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barre-Sinoussi F., Chermann J.C., Rey F., Nugeyre M.T., Chamaret S., Gruest J., Dauguet C., Axler-Blin C., Vezinet-Brun F., Rouzioux C., Rozenbaum W., Montagnier L. Science. 1983;220:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.6189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durantel D., Carrouee-Durantel S., Werle-Lapostolle B., Brunelle M.N., Pichoud C., Trepo C., Zoulim F. Hepatology. 2004;40:855–864. doi: 10.1002/hep.20388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horwich A.L., Furtak K., Pugh J., Summers J. J. Virol. 1990;64:642–650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.642-650.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seigneres B., Pichoud C., Martin P., Furman P., Trepo C., Zoulim F. Hepatology. 2002;36:710–722. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.35070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.