Abstract

Different forms of SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) spike protein-based vaccines for generation of neutralizing antibody response against SARS-CoV were compared using a mouse model. High IgG levels were detected in mice immunized with intraperitoneal (i.p.) recombinant spike polypeptide generated by Escherichia coli (S-peptide), mice primed with intramuscular (i.m.) tPA-optimize800 DNA vaccine (tPA-S-DNA) and boosted with i.p. S-peptide, mice primed with i.m. CTLA4HingeSARS800 DNA vaccine (CTLA4-S-DNA) and boosted with i.p. S-peptide, mice primed with oral live-attenuated Salmonella typhimurium (Salmonella-S-DNA-control) and boosted with i.p. S-peptide, mice primed with oral live-attenuated S. typhimurium that contained tPA-optimize800 DNA vaccine (Salmonella-tPA-S-DNA) and boosted with i.p. S-peptide, and mice primed with oral live-attenuated S. typhimurium that contained CTLA4HingeSARS800 DNA vaccine (Salmonella-tPA-S-DNA) and boosted with i.p. S-peptide. No statistical significant difference was observed among the Th1/Th2 index among these six groups of mice with high IgG levels. Sera of all six mice immunized with i.p. S-peptide, i.m. DNA vaccine control and oral Salmonella-S-DNA-control showed no neutralizing antibody against SARS-CoV. Sera of the mice immunized with i.m. tPA-S-DNA, i.m. CTLA4-S-DNA, oral Salmonella-S-DNA-control boosted with i.p. S-peptide, oral Salmonella-tPA-S-DNA, oral Salmonella-tPA-S-DNA boosted with i.p S-peptide, oral Salmonella-CTLA4-S-DNA and oral Salmonella-CTLA4-S-DNA boosted with i.p. S-peptide showed neutralizing antibody titers of <1:20–1:160. Sera of all the mice immunized with i.m. tPA-S-DNA boosted with i.p. S-peptide and i.m. CTLA4-S-DNA boosted with i.p. S-peptide showed neutralizing antibody titers of ≥1:1280. The present observation may have major practical value, such as immunization of civet cats, since production of recombinant proteins from E. coli is far less expensive than production of recombinant proteins using eukaryotic systems.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) has affected 30 countries in five continents with more than 8000 cases and 750 deaths. A novel virus, the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV), has been confirmed to be the etiological agent [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. In addition, we have also reported the isolation of SARS-CoV-like viruses from Himalayan palm civets found in a live animal market in the Guangdong Province of China, which implied that animals could be the reservoir for the ancestor of SARS-CoV [8].

In animal coronavirus infections, it has been shown that the spike proteins of coronaviruses were highly immunogenic, and immunization of animals using spike protein-based vaccines were able to produce neutralizing antibodies that were effective in prevention of infections caused by the corresponding coronaviruses. For SARS-CoV infection, it has been shown that nucleotides 952–1530 of the spike protein gene of SARS-CoV encoded a 193-amino acid fragment responsible for attaching to the receptor for SARS-CoV, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 [9]. Furthermore, we, and also others, have shown that patients with SARS produced antibody response against the spike protein of SARS-CoV [3], [10], [11], and it has been demonstrated that the spike protein is the major target for passive immunization [12], [13]. In studies that determine the relative importance of humoral and cell mediated immunity for protection against SARS-CoV infection, it was confirmed that neutralizing antibody, when administered by passive immunization, was crucial in conferring protection [14], whereas T-cell immunity was unable to lead to protection [15]. In addition, for vaccine candidates against SARS-CoV, spike protein-based DNA vaccines appeared to be a promising group of vaccine shown to produce protective immunity against SARS-CoV infections, whereas recombinant spike protein vaccines produced by Escherichia coli were not efficient in terms of generation of protective immunity as compared to those generated from eukaryotic systems such as transfection of cell lines [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. However, multiple doses of intramuscularly (i.m.) administered DNA vaccine or recombinant protein generated from the eukaryotic systems are quite expensive, and therefore may not be practical in developing countries. No data on less expensive modalities of immunization, such as DNA vaccine followed by boosters of recombinant vaccine produced by E. coli or oral mucosal DNA vaccines [26], [27], [28], [29], are available.

In this study, we compared the different forms of SARS-CoV spike protein-based vaccines for generation of neutralizing antibody response against SARS-CoV using a mouse model. The relative effectiveness of recombinant spike polypeptide vaccine produced by E. coli, two different types of intramuscular spike polypeptide DNA vaccine with and without boosters of recombinant spike polypeptide vaccine produced by E. coli and two different types of oral mucosal spike polypeptide DNA vaccine with and without boosters of recombinant spike polypeptide vaccine produced by E. coli are compared.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Male Balb/c (H-2d) mice (6–8 weeks old, 18–22 g) were used in all animal experiments. They were housed in cages, under standard conditions with regulated day length, temperature and humidity, and were given pelleted food and tap water ad libitum.

2.2. Recombinant SARS-CoV spike polypeptide vaccine from E. coli

Cloning and purification of the spike polypeptide of SARS-CoV was reported previously [3]. Briefly, to produce a plasmid for protein expression, primers (LPW742 5′-CGCGGATCCGAGTGACCTTGACCGGTGC-3′ and LPW931 5′-CGGGGTACCTTAACGTAATAAAGAAACTGTATG-3′) were used to amplify the gene encoding amino acid residues 14–667 of the spike protein of the SARS-CoV by RT-PCR. This portion of the spike protein was used because it contains the receptor-binding domain within the S1 domain that is highly immunogenic, whereas the complete spike protein was not expressible in E. coli. The PCR product was cloned into the BamHI and KpnI sites of vector pQE-31 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The resultant clone was digested by PstI, and the PstI fragment which contained the gene encoding amino acid residues 250–667 of the spike protein was cloned into expression vector pQE-30 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in frame and downstream of the series of six histidine residues. The (His)6-tagged recombinant spike polypeptide (S-peptide) was expressed and purified using the Ni2+-loaded HiTrap Chelating System (Amersham Pharmacia, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.3. Human codon usage optimized SARS-CoV DNA vaccines

To enhance the expression of spike polypeptide in human cells, the two SARS-CoV DNA vaccines, tPA-optimize800 (tPA-S-DNA) and CTLA4HingeSARS800 (CTLA4-S-DNA), were constructed using the concept of human codon usage optimization [30] with QUIKChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Strategene, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions. The synthetic polypeptides were cloned into pcDNA3.1(+).

2.4. Oral mucosal tPA-optimize800 and CTLA4HingeSARS800 DNA vaccines

The oral mucosal tPA-optimize800 and CTLA4HingeSARS800 DNA vaccines (Salmonella-tPA-S-DNA and Salmonella-CTLA4-S-DNA) were prepared according to our published protocol [26], [29]. tPA-S-DNA and CTLA4-S-DNA were transformed into auxotrophic S. typhimurium aroA strain SL7207 (S. typhimurium 2337-65 derivative hisG46, DEL 407 [aroA::Tn10{Tc-s}], a gift from Dr Bruce Stocker) [31] by electroporation.

2.5. Transfection of 293 cells with tPA-optimize800 and CTLA4HingeSARS800

Transfection of 293 cells with tPA-S-DNA and CTLA4-S-DNA was performed according to our published protocol [26], [29]. Two hundred and ninety-three cells were plated at 1 × 107 cells per well in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GibcoBRL, USA) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) in a six-well plate on the day before transfection. On the day of transfection, each well was transfected with 1 μg plasmid encoding eukaryotically expressed SARS-CoV spike polypeptide (tPA-S-DNA or CTLA4-S-DNA) or pcDNA3.1(+) (S-DNA-control) with FuGENE 6 Reagent (Boehringer Mannhein, Germany) according to manufacturer's instructions. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were harvested and lysed by freezing and thawing three times. After centrifugation at 14000 rpm, the supernatant was used for the detection of SARS-CoV spike polypeptide by Western blot assay using pre-immune rabbit serum and hyperimmune polyclonal serum from rabbit immunized with S-peptide.

2.6. Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed according to our published protocol [29]. Briefly, 10 μl of supernatant of 293 cell lysates obtained from 293 cells transfected with tPA-S-DNA, CTLA4-S-DNA or S-DNA-control was loaded into each well of a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–8% polyacrylamide gel and subsequently electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The blot was incubated separately with 1:1000 dilution of pre-immune rabbit serum or hyperimmune polyclonal serum from rabbit immunized with S-peptide. Antigen–antibody interaction was detected with an ECL fluorescence system (Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, UK).

2.7. Immunization schedule

Seventy-two Balb/c mice were used for the immunization experiments. The immunization schedule is summarized in Table 1 . On days 0, 14 and 28, six mice were immunized intraperitoneally (i.p.) with S-peptide [0.5 μg per mouse (Group 1, Table 1)]. On day 0, six mice were immunized i.m. (tibialis anterior muscle) with S-DNA-control [100 μg per mouse (Group 2, Table 1)] and 12 mice each were immunized i.m. with tPA-S-DNA [100 μg per mouse (Group 3, Table 1)] or CTLA4-S-DNA [100 μg per mouse (Group 5, Table 1)]. On days 28 and 42, 6 of the 12 mice in the two DNA vaccine groups were boosted with i.p. S-peptide [0.5 μg per mouse (Groups 4 and 6, Table 1)]. On day 0, 12 mice each were immunized orally with S. typhimurium aroA strain (Salmonella-S-DNA-control) [6 × 109 bacterial cells per mouse (Group 7, Table 1)], Salmonella-tPA-S-DNA [6 × 109 bacterial cells per mouse (Group 9, Table 1)] or Salmonella-CTLA4-S-DNA [6 × 109 bacterial cells per mouse (Group 11, Table 1)]. On days 28 and 42, 6 of the 12 mice in the three groups were boosted with i.p. S-peptide [0.5 μg per mouse (Groups 8, 10 and 12, Table 1)].

Table 1.

Immunization schedule for different forms of spike polypeptide-based vaccines against SARS-CoV

| Groups | First dose (day 0) |

Second dose |

Third dose |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccines | Routes of administration | Dose per mouse | Vaccines | Routes (days) of administration | Dose per mouse | Vaccines | Routes (days) of administration | Dose per mouse | |

| 1 | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal | 50 μg | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (14) | 50 μg | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (28) | 50 μg |

| 2 | pcDNA3.1(+) | Intramuscular | 100 μg | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3 | tPA-optimize800 DNA vaccine | Intramuscular | 100 μg | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4 | tPA-optimize800 DNA vaccine | Intramuscular | 100 μg | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (28) | 50 μg | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (42) | 50 μg |

| 5 | CTLA4HingeSA RS800 DNA vaccine | Intramuscular | 100 μg | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6 | CTLA4HingeSA RS800 DNA vaccine | Intramuscular | 100 μg | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (28) | 50 μg | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (42) | 50 μg |

| 7 | S. typhimurium aroA strain | Oral | 6 × 109 bacterial cells | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8 | S. typhimurium aroA strain | Oral | 6 × 109 bacterial cells | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (28) | 50 μg | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (42) | 50 μg |

| 9 | Mucosal tPA-optimize800 DNA vaccine | Oral | 6 × 109 bacterial cells | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10 | Mucosal tPA-optimize800 DNA vaccine | Oral | 6 × 109 bacterial cells | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (28) | 50 μg | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (42) | 50 μg |

| 11 | Mucosal CTLA4HingeSA RS800DNA vaccine | Oral | 6 × 109 bacterial cells | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 12 | Mucosal CTLA4HingeSA RS800 DNA vaccine | Oral | 6 × 109 bacterial cells | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (28) | 50 μg | Spike polypeptide | Intraperitoneal (42) | 50 μg |

2.8. Measurement of serum antibodies against SARS-CoV spike polypeptide

Mice from each group were bled on the day before immunization and 42 days after the last dose of vaccine in the corresponding group. The blood was centrifuged at 2700 × g for 20 min and the supernatant (serum) was stored at −70 °C before antibody measurement.

Antibodies against SARS-CoV spike polypeptide were measured using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to our published protocol with modifications [3], [4]. Mouse sera (diluted with PBS-2% skim milk, 1:10 for IgM, 1:80 for IgG, 1:1280 for IgG1, 1:40 for IgG2a, 1:10 for IgG2b and 1:320 for IgG3) were added to ELISA plates precoated with S-peptide (80 ng per well for IgM, IgG, IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG3 and 10 ng per well for IgG1). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After washing with washing buffer five times, 100 μl peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM and IgG, rabbit anti-mouse IgG1, IgG2a and IgG3 and rat anti-mouse IgG2b antibody (Zymed Laboratories Inc., USA) diluted according to manufacturer's instructions using PBS-2% skim milk were added to the corresponding wells accordingly and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. IgM and total IgG levels were assayed to assess the primary and secondary immune response, while the IgG subtypes were used to determine whether the humoral response was inclined towards the Th1 (IgG2a and IgG2b) or Th2 (IgG1 and IgG3) pattern. After washing with washing buffer five times, 100 μl diluted 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Zymed Laboratories Inc.) was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. One hundred microliters of 0.3 M H2SO4 was added and the absorbance at 450 nm of each well was measured. Each sample was tested in duplicate and the mean absorbance for each serum was calculated. The serum antibody level of a particular mouse was defined as the absorbance obtained from the serum taken 42 days after the last dose of the vaccine minus that of the corresponding mouse taken the day before immunization. The Th1/Th2 index of each mouse is calculated by the following formula: IgG2a × IgG2b/IgG1 × IgG3.

2.9. Neutralizing antibody assay

The neutralizing antibody assay was modified from our published protocol [32]. All work with infectious virus was performed inside a type II Biosafety Cabinet, in a Biosafety Containment level III facility, and the personnel wore powered air-purifying respirators (HEPA Airmate, 3M, St. Paul, MN). Initial screening of mouse sera against the prototype SARS-CoV strain no. 39849 was performed in 96-well microtiter plates seeded with fetal rhesus kidney-4 cells. Two-fold dilutions of mouse sera (from 1:20 to 1:1280) were tested in duplicate against 100 TCID50 of SARS-CoV. A corresponding set of cell controls with sera but without virus inoculation was used as controls. The cells were scored for the inhibition of the cytopathic effect (CPE) at 48 h. The titer of neutralizing antibody is defined as the maximum dilution of serum at which the percentage of CPE is less than or equal to 50%.

2.10. Measurement of lymphocyte proliferation index (LPI)

LPI was measured according to our published protocol [29]. On day 60, single-cell suspensions of spleen cells from the six mice of each group were depleted of erythrocytes by adding freshly prepared Gey's solution. The cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD) supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum and inoculated into microwell plates at 5 × 105 cells per well in triplicate. Cells were stimulated with phytohaemagglutinin at 5 μg per well (positive control), S-peptide at 0.1 μg per well or RPMI medium (negative control). Cells were cultured at 37 °C 5% CO2 for 3 days, and 3H-labelled thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia, Little Chalfont, UK) was added at 1 μCi per well for the last 18 h. Cells were harvested onto glass microfibre filter (Whatman International Ltd., UK) using a Model CH1 cell harvester (Insel, Hampshire, UK) and radioactivity was measured by a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman, Fullerton, CA). The S-peptide-specific LPI of a particular sample is defined as the ratio of the difference of radioactivity between the sample and the negative control and that between the positive and negative controls.

2.11. Interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) assays

IL-4 and IFN-γ were assayed according to our published protocol [29]. On day 60, spleens from the six mice in each group were harvested. Single-cell suspensions were prepared and cells from mice within the same group were pooled. 2 × 106 cells were cultured in 1 ml RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol in 24-well plates. S-peptide was added at final concentrations of 0.5, 1.0 and 2.5 μg/ml. Supernatant (200 μl) from each sample was collected at 24, 48 and 72 h for cytokine measurement. Monoclonal antibodies against IL-4 or IFN-γ were coated onto wells in 96-well microtiter plates (OptEIA, PharM3ingen, Becton Dickinson, USA) at 1:250 dilutions according to manufacturer's instructions. The plates were incubated at RT for 24 h. After washing with washing buffer three times, the plates were blocked with assay diluent at RT for 1 h. After washing with washing buffer three times, 100 μl of supernatant from each sample was added to the wells in duplicate. The plates were incubated at RT for 2 h. After washing with washing buffer five times, 100 μl diluted biotinylated antibody against IL-4 or IFN-γ and avidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate were added to the wells and incubated at RT for 1 h. After washing with washing buffer eight times, 100 μl TMB substrate was added to each well and incubated at RT for 30 min. Hundred microliters of 0.3 M H2SO4 was added and the absorbance of each well was measured at 450 nm, using TMB buffer as a blank. Each pooled sample was tested in triplicate and the mean absorbance for each pooled sample was calculated.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Comparison was made among the serum antibody levels and LPI of the various groups of mice using one-way ANOVA. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. SARS-CoV spike polypeptide expression in 293 cells transfected with tPA-optimize800 and CTLA4HingeSARS800

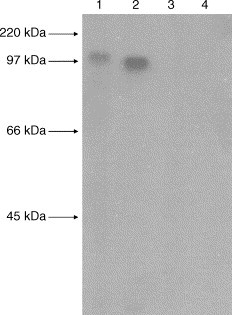

The supernatant of 293 cell lysates obtained from 293 cells transfected with tPA-S-DNA, CTLA4-S-DNA or S-DNA-control were separated on SDS–polyacrylamide gels followed by Western blot analysis with sera from pre-immune rabbit serum or hyperimmune polyclonal serum from rabbit immunized with S-peptide. Prominent immunoreactive protein bands of about 90 and 110 kDa were visible on the Western blot that used cell lysates obtained from 293 cells transfected with tPA-S-DNA and CTLA4-S-DNA, respectively, as the antigen and hyperimmune polyclonal serum from rabbit immunized with S-peptide as the source of antibody (Fig. 1 , lanes 1 and 2). These sizes were consistent with the expected size of 91.4 and 108.1 kDa for the corresponding spike polypeptides.

Fig. 1.

Prominent immunoreactive protein bands of about 90 and 110 kDa were visible on the Western blot (lanes 1 and 2), indicating antigen–antibody interactions between the 293 cell lysates obtained from 293 cells transfected with tPA-optimize800 and CTLA4HingeSARS800, respectively, and hyperimmune polyclonal serum from rabbit immunized with (His)6-tagged recombinant spike polypeptide. No antigen–antibody interactions were observed between the 293 cell lysates obtained from 293 cells transfected with tPA-optimize800 or CTLA4HingeSARS800 and the pre-immune rabbit serum (lanes 3 and 4).

3.2. Antibody response

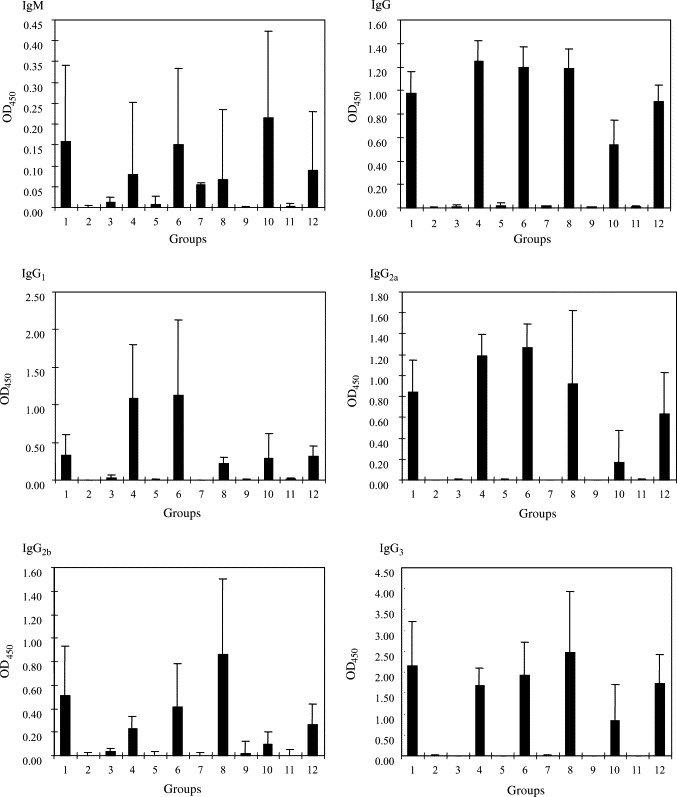

The antibody levels of the 12 groups of mice on day 42 were summarized in Fig. 2 . No IgG was detected in mice of Groups 2, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 11, whereas high IgG levels were detected in mice of Groups 1, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12. No statistical significant difference was observed among the Th1/Th2 index among these six groups of mice with high IgG levels.

Fig. 2.

Serum antibody levels (O.D. 450) at day 42 in the 12 groups of Balb/c mice immunized with the various vaccines. The 12 groups correspond to the 12 groups of mice described in Table 1 (bar = average of six mice, error bar = 1 standard deviation).

3.3. Neutralizing antibody assay

The number of mice with different neutralizing antibody titers immunized with different forms of spike polypeptide-based vaccines against SARS-CoV was shown in Table 2 . Sera of all the six mice immunized with i.p. S-peptide, i.m. S-DNA-control and oral Salmonella-S-DN A-control (Groups, 1, 2 and 7) showed no neutralizing antibody against SARS-CoV. Sera of the mice immunized with i.m. tPA-S-DNA, i.m. CTLA4-S-DNA, oral Salmone-lla-S-DNA-control boosted with i.p. S-peptide, oral Salmonella-tPA-S-DNA, oral Salmonella-tPA-S-DNA boosted with i.p S-peptide, oral Salmonella-CTLA4-S-DNA and oral Salmonella-CTLA4-S-DNA boosted with i.p. S-peptide (Groups, 3, 5 and 8–12) showed neutralizing antibody titers of <1:20–1:160. Sera of all the mice immunized with i.m. tPA-S-DNA boosted with i.p. S-peptide and i.m. CTLA4-S-DNA boosted with i.p. S-peptide (Groups 4 and 6) showed neutralizing antibody titers of ≥ l:1280.

Table 2.

Neutralizing antibody titers for different forms of spike polypeptide-based vaccines against SARS-CoV

| Groups | Neutralizing antibody titers (no. of mice) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1:20 | 1:20 | 1:40 | 1:80 | 1:160 | 1:320 | 1:640 | ≥1:1280 | |

| 1 (S-peptide) | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 (S-DNA-control) | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 (tPA-S-DNA) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 (tPA-S-DNA boosted with S-peptide) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 5 (CTLA4-S-DNA) | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 (CTLA4-S-DNA boosted with S-peptide) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 7 (Salmonella-S-DNA-control) | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 (Salmonella-S-DNA-control boosted with S-peptide) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 (Salmonella-tPA-S-DNA) | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 (Salmonella-tPA-S-DNA boosted with S-peptide) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 (Salmonella-CTLA4-S-DNA) | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 (Salmonella-CTLA4-S-DNA boosted with S-peptide) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

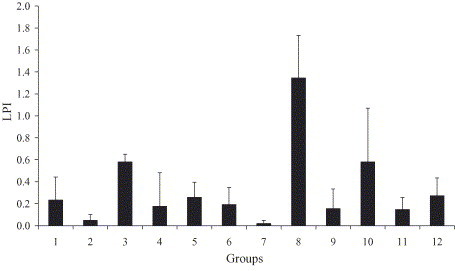

3.4. Lymphocyte proliferation index

The S-peptide-specific LPI of the 12 groups of mice on day 60 were summarized in Fig. 3 . Significant lymphocyte proliferation was detected in Groups 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12, compared to the control groups (Groups 2 and 7).

Fig. 3.

SARS-CoV spike polypeptide-specific lymphocyte proliferation index of Balb/c mice immunized with the various vaccines. The 12 groups correspond to the 12 groups of mice described in Table 1 (bar = average of six mice, error bar = 1 standard deviation).

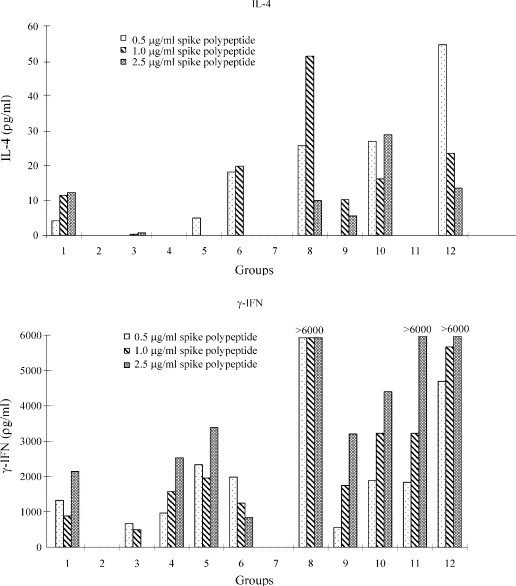

3.5. Interleukin-4 and interferon-γ assays

At 24 h, IL-4 was undetectable in all 12 groups of mice for all three concentrations of S-peptide (data not shown). At 48 h, IL-4 was detectable only in mice of Groups 6, 8 and 12 (data not shown). At 72 h, IL-4 was detectable in mice of Groups 1, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10 and 12 (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

IL-4 (at 72 h) and Interferon-γ (at 24 h) levels of splenic cell culture supernatant in Balb/c mice immunized with the various vaccines. The 12 groups correspond to the 12 groups of mice described in Table 1.

At 24 h, the IFN-γ levels of the 12 groups of mice are shown in Fig. 4. IFN-γ was detectable in mice of Groups 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12. At 48 and 72 h, the IFN-γ levels mice of Groups 1, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11 and 12 were all >6000 pg/ml (data not shown).

4. Discussion

Among all the combinations of vaccines examined in this study, mice primed with SARS-CoV human codon usage optimized spike polypeptide DNA vaccines and boosted with S-peptide produced by E. coli generated the highest titer of neutralizing antibody against SARS-CoV. It has been observed, and is confirmed in the present study, that S-peptide produced by E. coli did not induce neutralizing antibody against SARS-CoV infection (Table 2, Group 1). On the other hand, recombinant spike polypeptide generated by eukaryotic systems such as transfection of COS7 and BHK21 cells or DNA vaccine was able to elicit high neutralizing antibody titer against SARS-CoV infection [15], [21], [24]. This was probably because when S-peptide produced by E. coli was used, the three dimensional folding and/or the glycosylation of the S-peptide was not optimal for the generation of neutralizing antibodies. In this study, we documented that although recombinant S-peptide produced by E. coli itself was not able to generate neutralizing antibody against SARS-CoV infection, mice primed with spike polypeptide DNA vaccine and boosted with S-peptide from E. coli were able to generate high titer of neutralizing antibody against SARS-CoV (Table 2, Groups 4 and 6). This indicates that the type of vaccine used for priming is crucial in determining the type of immune response developed. Subsequent doses will booster the immune response generated by the first dose of vaccine. Of note is that the humoral immune response developed in mice primed with spike polypeptide DNA vaccine and boosted with S-peptide from E. coli was not particularly of the Th1 type as compared to that developed in mice immunized with S-peptide from E. coli alone. This indicates that a Th1 type immune response may not be essential for the generation of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV. Although our results suggest that priming with DNA vaccines and boosting with S-peptide produced by E. coli was successful in the generation of neutralizing antibody against SARS-CoV, further experiments using infection models to evaluate its protective immunity are warranted, since anti-spike antibodies have been shown to enhance the infectivity of coronaviruses in some cell culture systems, as occurred with SARS-CoV and feline infectious peritonitis virus [33], [34].

The present observation may have major practical value, such as immunization of civet cats, as production of recombinant proteins from E. coli is far less expensive than production of recombinant proteins using eukaryotic systems such as transfection of cell lines or DNA vaccines. Although it has been shown that DNA vaccines are able to generate both humoral and cellular immunity successfully for various pathogens in mice, one of the major limitations for its clinical use is its ineffectiveness when it is used in humans, unless a large amount of DNA is used for immunization [35], [36]. As for the production of recombinant spike polypeptide generated by eukaryotic systems such as transfection of COS7 and BHK21 cells [24] or using the baculovirus system [25], although the conformation and/or glycosylation of the spike polypeptide produced can theoretically be more similar to the native viral spike protein, it is not easy to scale up the production of such recombinant proteins to industrial levels. In contrast to recombinant spike polypeptide generated by eukaryotic systems, a large amount of S-peptide can be produced by E. coli in a relatively inexpensive way, and such S-peptide can be used successfully as boosters. Further studies on the effectiveness of this mode of vaccination for generation of protective immunity against SARS-CoV in other animals could be performed. This principle can also be examined in vaccination for other pathogens, where “more effective” modalities of vaccination, such as DNA vaccine, can be used for priming, and the “less expensive” recombinant protein produced by E. coli, instead of eukaryotic systems, can be used as boosters.

Spike polypeptide DNA vaccines delivered by the live-attenuated Salmonella system did not induce good neutralizing antibody against SARS-CoV infection. We have previously shown that hepatitis B virus DNA vaccine presented by the live-attenuated Salmonella system generated good cytotoxic T lymphocyte response, but minimal antibody response, against hepatitis B virus in a mouse model [26], [27]. Furthermore, we found that this immune response was able to down-regulate transgene expression in hepatitis B virus surface antigen transgenic mice [28]. Subsequently, we reported a comparison of the efficacy of DNA vaccine, DNA vaccine delivered by the live-attenuated Salmonella system and recombinant protein vaccine for generation of protective immune response against Penicillium marneffei, a thermal dimorphic fungus infecting 10% of HIV positive patients in China and Southeast Asia, in a mouse model [29]. Results showed that, similar to hepatitis B virus DNA vaccine presented by the live-attenuated Salmonella system, P. marneffei DNA vaccine delivered by the live-attenuated Salmonella system did not generate good antibody response, whereas intramuscular DNA vaccine generated the best protective immunity against P. marneffei infection, implying that both cellular and humoral immune response are important for protection against P. marneffei infection [29]. In the present study, it was observed that, in line with the results of hepatitis B virus DNA vaccine and P. marneffei DNA vaccine delivered by the live-attenuated Salmonella system, spike polypeptide DNA vaccines delivered by the live-attenuated Salmonella system did not induce good antibody response (Fig. 2 and Table 2, Groups 9 and 11). Although the mice developed high antibody levels against the spike protein after boosting with S-peptide (Fig. 2, Groups 10 and 12), the antibodies were not neutralizing in our cell culture system (Table 2, Groups 10 and 12). This may be due to the ineffectiveness of the DNA vaccine delivered by the live-attenuated Salmonella system in priming the development of neutralizing antibodies in the correct configuration, while the “non-neutralizing” antibodies against the spike protein were only elicited in response to the subsequent recombinant S-peptide.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the Research Fund for the Control of Infectious Diseases of the Health, Welfare and Food Bureau of the Hong Kong SAR Government 01030282, SARS Research Fund, University SARS Donation Fund and the Research Grant Council Grant.

References

- 1.Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361(9366):1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peiris J.S., Chu C.M., Cheng V.C., Chan K.S., Hung I.F., Poon L.L. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Tsoi H.W., Chan K.H., Wong B.H., Che X.Y. Relative rates of non-pneumonic SARS coronavirus infection and SARS coronavirus pneumonia. Lancet. 2004;363(9412):841–845. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Wong B.H., Tsoi H.W., Fung A.M., Chan K.H. Detection of specific antibodies to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus nucleocapsid protein for serodiagnosis of SARS coronavirus pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(5):2306–2309. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.2306-2309.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Wong B.H., Woo G.K., Poon R.W., Tsoi H.W. Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus nucleoapsid protein in SARS patients by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(7):2884–2889. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.2884-2889.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Wong B.H., Chan K.H., Chu C.M., Tsoi H.W. Longitudinal profile of immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, and IgA antibodies against the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus nucleocapsid protein in patients with pneumonia due to the SARS coronavirus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11(4):665–668. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.4.665-668.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Wong B.H., Chan K.H., Hui W.T., Kwan G.S. False-positive resultss in recombinant severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) nucleocapsid enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay due to HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-229E rectified by Western blotting with recombinant SARS-CoV spike polypeptide. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(12):5885–5888. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5885-5888.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Guan Y., Zheng B.J., He Y.Q., Liu X.L., Zhuang Z.X., Cheung C.L. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003;302(5643):276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong S.K., Li W., Moore M.J., Choe H., Farzan M. A 193-amino acid fragment of the SARS coronavirus S protein efficiently binds angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(5):3197–3201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang L.R., Chiu C.M., Yeh S.H., Huang W.H., Hsueh P.R., Yang W.Z. Evaluation of antibody responses against SARS coronaviral nucleocapsid or spike proteins by immunoblotting of ELISA. J Med Virol. 2004;73(3):338–346. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsueh P.R., Kao C.L., Lee C.N., Chen L.K., Ho M.S., Sia C. SARS antibody test for serosurveillance. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(9):1558–1562. doi: 10.3201/eid1009.040101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traggiai E., Becker S., Subbarao K., Kolesnikova L., Uematsu Y., Gismondo M.R. An efficient method to make human monoclonal antibodies from memory B cells: potent neutralization of SARS coronavirus. Nat Med. 2004;10(8):871–875. doi: 10.1038/nm1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ter Meulen J., Bakker A.B., van den Brink E.N., Weverling G.J., Martina B.E., Haagmans B.L. Human monoclonal antibody as prophylaxis for SARS coronavirus infection in ferrets. Lancet. 2004;363(9427):2139–2141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16506-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bisht H., Roberts A., Vogel L., Bukreyev A., Collins P.L., Murphy B.R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein expressed by attenuated vaccinia virus protectively immunizes mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(17):6641–6646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401939101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Z.Y., Kong W.P., Huang Y., Roberts A., Murphy B.R., Subbarao K. A DNA vaccine induces SARS coronavirus neutralization and protective immunity in mice. Nature. 2004;428(6982):561–564. doi: 10.1038/nature02463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchholz U.J., Bukreyev A., Yang L., Lamirande E.W., Murphy B.R., Subbarao K. Contributions of the structural proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus to protective immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(26):9804–9809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403492101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bukreyev A., Lamirande E.W., Buchholz U.J., Vogel L.N., Elkins W.R., St Claire M. Mucosal immunisation of African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) with an attenuated parainfluenza virus expressing the SARS coronavirus spike protein for the prevention of SARS. Lancet. 2004;363(9427):2122–2127. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16501-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao W., Tamin A., Sol off A., D’Aiuto L., Nwanegbo E., Robbins P.D. Effects of a SARS-associated coronavirus vaccine in monkeys. Lancet. 2003;362(9399):1895–1896. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14962-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim T.W., Lee J.H., Hung C.F., Peng S., Roden R., Wang M.C. Generation and characterization of DNA vaccines targeting the nucleocapsid protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2004;78(9):4638–4645. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4638-4645.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang L., Zhu Q., Qin E., Yu M., Ding Z., Shi H. Inactivated SARS-CoV vaccine prepared from whole virus induces a high level of neutralizing antibodies in BALB/c mice. DNA Cell Biol. 2004;23(6):391–394. doi: 10.1089/104454904323145272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng F., Chow K.Y., Hon C.C., Law K.M., Yip C.W., Chan K.H. Characterization of humoral responses in mice immunized with plasmid DNAs encoding SARS- CoV spike gene fragments. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315(4):1134–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu M.S., Pan Y., Chen H.Q., Shen Y., Wang X.C., Sun Y.J. Induction of SARS- nucleoprotein-specific immune response by use of DNA vaccine. Immunol Lett. 2004;92(3):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H., Wang G., Li J., Nie Y., Shi X., Lian G. Identification of an antigenic determinant on the S2 domain of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein capable of inducing neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2004;78(13):6938–6945. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.6938-6945.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song H.C., Seo M.Y., Stadler K., Yoo B.J., Choo Q.L., Coates S.R. Synthesis and characterization of a native, oligomeric form of recombinant severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein. J Virol. 2004;78(19):10328–10335. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10328-10335.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mortola E., Roy P. Efficient assembly release of SARS coronavirus-like particles by a heterologous expression system. FEBS Lett. 2004;576(1–2):174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woo P.C., Wong L.P., Zheng B.J., Yuen K.Y. Unique immunogenicity of hepatitis B virus DNA vaccine presented by live-attenuated Salmonella typhimurium. Vaccine. 2001;19(20–22):2945–2954. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00530-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng B.J., Woo PCY, Ng M.H., Tsoi H.W., Wong L.P., Yuen K.Y. A crucial role of macrophages in the immune responses to oral DNA vaccination against hepatitis B virus in a murine model. Vaccine. 2001;20(1–2):140–147. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng B.J., Ng M.H., Chan K.W., Tam S., Woo PCY, Ng S.P. A single dose of oral DNA immunization delivered by attenuated Salmonella typhimurium down-regulates transgenic expression in HBsAg transgenic mice. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32(11):3294–3304. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200211)32:11<3294::AID-IMMU3294>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong L.P., Woo P.C., Wu A.Y., Yuen K.Y. DNA immunization using a secreted cell wall antigen Mp1p is protective against Penicillium marneffei infection. Vaccine. 2002;20(23–24):2878–2886. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deml L., Bojak A., Steck S., Graf M., Wild J., Schirmbeck R. Multiple effects of codon usage optimization on expression and immunogenicity of DNA candidate vaccines encoding the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein. J Virol. 2001;75(22):10991–11001. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10991-11001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoiseth S.K., Stocker B.A. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;291(5812):238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen F., Chan K.H., Jiang Y., Kao R.Y., Lu H.T., Fan K.W. In vitro susceptibility of 10 clinical isolates of SARS coronavirus to selected antiviral compounds. J Clin Virol. 2004;31(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsen C.W., Corapi W.V., Ngichabe C.K., Baines J.D., Scott F.W. Monoclonal antibodies to the spike protein of feline infectious peritonitis virus mediate antibody-dependent enhancement of infection of feline macrophages. J Virol. 1992;66(2):956–965. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.956-965.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Z.Y., Werner H.C., Kong W.P., Leung K., Traggiai E., Lanzavecchia A. Evasion of antibody neutralization in emerging severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(3):797–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409065102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manoj S., Babiuk L.A., van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S. Approaches to enhance the efficacy of DNA vaccines. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2004;41(1):1–39. doi: 10.1080/10408360490269251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dupuis M., Denis-Mize K., Woo C., Goldbeck C., Selby M.J., Chen M. Distribution of DNA vaccines determines their immunogenicity after intramuscular injection in mice. J Immunol. 2000;165(5):2850–2858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]