Abstract

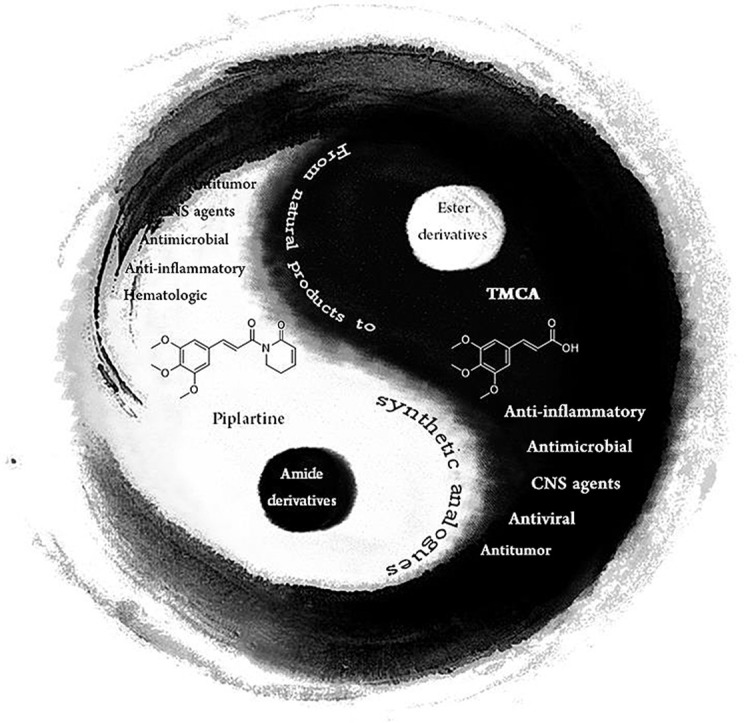

TMCA (3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamic acid) ester and amide are privileged structural scaffolds in drug discovery which are widely distributed in natural products and consequently produced diverse therapeutically relevant pharmacological functions. Owing to the potential of TMCA ester and amide analogues as therapeutic agents, researches on chemical syntheses and modifications have been carried out to drug-like candidates with broad range of medicinal properties such as antitumor, antiviral, CNS (central nervous system) agents, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and hematologic agents for a long time. At the same time, SAR (structure-activity relationship) studies have draw greater attention among medicinal chemists, and many of the lead compounds were derived for various disease targets. However, there is an urgent need for the medicinal chemists to further exploit the precursor in developing chemical entities with promising bioactivity and druggability. This review concisely summarizes the synthesis and biological activity for TMCA ester and amide analogues. It also comprehensively reveals the relationship of significant biological activities along with SAR studies.

Keywords: 3,4,5-Trimethoxycinnamic acid; TMCA derivatives; SAR; Antitumor agents; Antiviral agents; CNS agnets; Antimicrobial agents; anti-inflammatory agents; Hematologic agents

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

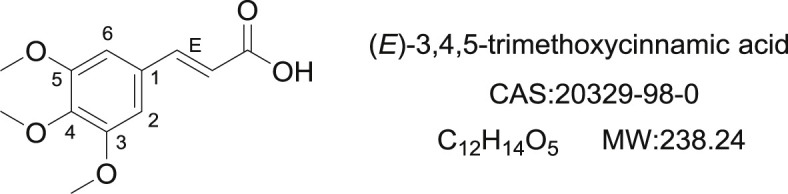

TMCA is a cinnamic acid substituted by multi-methoxy groups (Fig. 1 ). It is considered as an active metabolite of the root of Polygala tenuifolia Wild. (Polygalaceae), which have been used as traditional medicine in China for treating insomnia, headache and epilepsy [1,2]. TMCA has been reported to show anticonvulsant and sedative activity in former studies, and mechanism research reveal that it act as a GABAA/BZ receptor agonist for anti-seizure and insomnia therapy [3,4]. The appealing structural scaffold and pharmacological importance of TMCA has encouraged researches to synthesize its drivatives as novel drug candidates. Up to now, TMCA derivatives have attracted great attention and interest from researchers in the field of medicinal chemistry [5].

Fig. 1.

Structure of 3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamic acid (TMCA).

TMCA acts as a precursor to construct a large number of structural frameworks for diverse applications. The carboxyl group of TMCA is the most frequently concerned group for modification. Additionally, ester and amide derivatives are the most important analogues to report in this review. The substitution point at C=C bond and methoxy groups are also briefly mentioned in this article [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. The modifications in these frameworks lead to the broadening of activity continuum of TMCA analogues [10,11].

As for the pharmacology researches, this review is focus on the properties of TMCA esters and amides as antitumor, antiviral, CNS agnets, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and hematologic agents. We summarized advances in natural products of TMCA analogues (N1-9) and synthetic derivatives (S1-74). As for the synthetic derivatives, both the investigations that TMCA as core nucleus or as active substituent are reviewed. When using TMCA as substituent, the analogues are compared to the most potent compound according to SAR. For these points of view, this review is dedicated to accomplish an urgent need of compilation and summarization of natural products, biological activities and SAR that could be helpful for researchers to design some new potentially active of TMCA analogues.

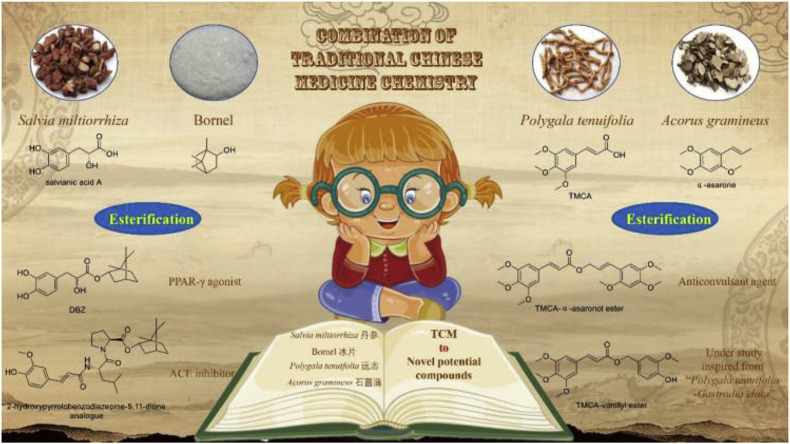

With the development of society, health problems arouse more and more attention worldwide. Side effects and multidrug-resistant exist in clinical utilizations of modern drugs have forced researchers to set their sights to natural products to seek precursors with more safety and efficiency. TCM (Traditional Chinese Medicine), a cluster of time-honored herb medicine, has attracted much attention in developing new drugs. Our research group has made unremitting effort to seek promising lead compounds from TCM, not only TMCA from P. tenuifolia, but also α-asarone from Acorus gramineus, salvianic acid A from Salvia miltiorrhiza and vanillyl alcohol from Gastrodia elata have been absorbed into the investigation [12,13]. Combination of Traditional Chinese Medicine Chemistry, CTCMC, is our main drug design strategy (Fig. 2 ), which means to integrate active constituents based on TCM theory. Accordint to the strategy CTCMC, we have developed potential lead compounds including DBZ (tanshinol borneol ester) [14,15], 2-hydroxypyrrolobenzodiazepine-5,11-dione analogues [16] and TMCA-α-asaronol ester [17,18]. We believe that this strategy is benefit to the innovation of new drugs from natural products. Moreover, we consider that this strategy can be helpful to decrease the costs during screening the test compounds and the blindness existing in the structural modification of natural products.

Fig. 2.

Drug design strategy: based on Combination of Traditional Chinese Medicine Chemistry (CTCMC).

2. Biological activities of natural TMCA ester and amide derivatives

2.1. TMCA esters and amide isolated from natural products

TMCA esters are widely distributed in several types of medicinal plants. The genus Polygala, containing spiecs P. tenuifolia, is the richest resource for TMCA esters [19]. Additionally, TMCA esters also exist in the genus Erythroxylum [20] and Rauwolfia [21].

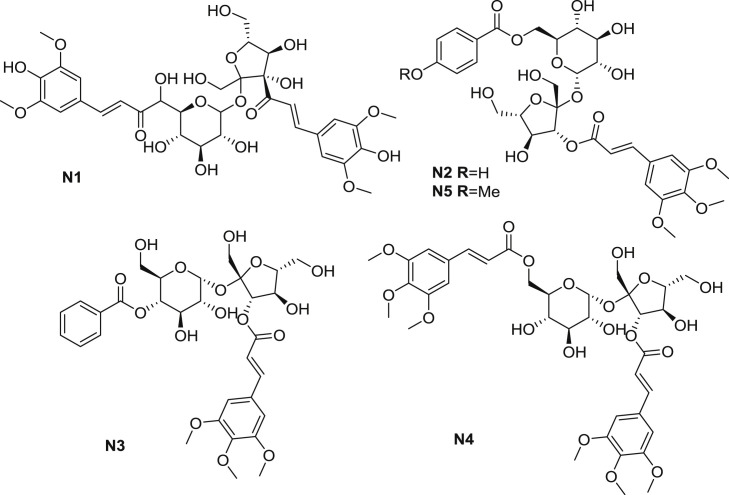

3,6′-disinapoyl sucrose (N1), an active oligosaccharide acyl component obtained from the roots of P. tenuifolia., is recorded as the standards for quality control of P. tenuifolia using the HPLC (high performance liquid chromatography) determination method according to the 2015 edition of Chinese pharmacopoeia (Fig. 3 ) [22]. TMCA has been demonstrated to be the metabolite of N1 [23]. The latter showed antidepressant activity mediating via the inhibiting of MAO (monoamine oxidase)-A and MAO-B activity, reducing plasma cortisol and MDA levels, increasing SOD (superoxide dismutase) activity [24]. Tenuifoliside A (N2), another active TMCA ester isolated from P. tenuifolia, possessed antidepressant-like, cognitive enhancement and cerebral protective effects [25,26]. In addition, N2 was proved to promote the viability of rat glioma cells C6 through BDNF (brain derived neurotrophic factor)/TrkB-ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase)/PI3KCREB signaling pathway [27].

Fig. 3.

TMCA esters isolated from P. tenuifolia.

Bioactivity-guided fractionation of root extract of P. tenuifolia yielded some constituents with soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitory activity (Table 1 .), including esters N2, N3, N4 and N5 [28]. Thereinto, ester N5 displayed the most potent inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase with the IC50 (half maximal inhibitory concentration) value of 6.4 μM. Ester N2, which was structurally similar to ester N5, performed best interaction between the soluble epoxide hydrolase in molecular docking (RCSB Protein Data Bank ID: 3ANS). As for the SAR, research results demonstrated that the substituted benzoic acid esterification on the pyranose was helpful for the compounds to interact with active site of soluble epoxide hydrolase.

Table 1.

Inhibitory activity of soluble epoxide hydrolase and interaction for ester N2, N3, N4 and N5.

| Com. | Inhibitory activity |

Interaction and Autodock score |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 μM (%) | IC50 (μM) | Type | Hydrogen bonds (Å) | Binding energyb | |

| N2 | >100 | 9.1 | a | Tyr343(2.68), Gln384(2.79), Asn378(2.62), Met503(3.22) | −7.36 |

| N3 | >100 | 18.0 | a | Thr360(2.71), Gln384(3.06) | −6.79 |

| N4 | 97.4 | 27.2 | a | Gln384(2.91) | −8.27 |

| N5 | >100 | 6.4 | a | Asp335(3.30), Gln384(3.14) | −7.87 |

| AUDAc | 4.4 | ||||

a: competitive; b: kcal/mol; c: positive control.

In 2013, Zhao et al. [29] presented that one of the major metabolite of P. tenuifolia in rat, 3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamate (N6), at the dosage of 15–30 μM markedly shortened APD50 (action potential duration at 50% repolarization) and APD90 (action potential duration at 90% repolarization) in cardiomyocytes in a concentration-dependent and a reversible manner (Fig. 4 ). Moreover, ester N6 suppressed L-type calcium current, but showed effect on neither Ito (transient outward potassium current) nor I K,SS (steady-state potassium current). Furthermore, N6 abolished isoprenaline and BayK8644-induced EADs (early afterdepolarizations), suppressed DADs (delayedafterdepolarizations) and Tas (triggered activities). The phenomenon revealed that N6 protected heart from arrhythmias via its inhibitory effect on calcium channel. Ester N6 was also described to probe the active site of esterase named FAE-III, with the Km (substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vmax) value of 1.63, and Kcat (limiting rate of any enzyme-catalyzed reaction at saturation) value of 1063 [30].

Fig. 4.

TMCA esters isolated from other natural products.

Pervilleine A (N7) was isolated and characterized from Erythroxylum pervillei (Fig. 4) [20]. Cholinergic and adrenergic effects of N7 were investigated. Ester N7 (30 μM) non-competitively inhibited cholinergic response in the guinea-pig ileum and did not affect the carbachol-induced contraction of the rat anococcygeus smooth muscle. Further research indicated that N7 exhibited weak vascular antiadrenergic and nonspecific anticholinergic effects. Subsequently, compounds structurally similar to N7 were obtained from Erythroxylum pervillei. The cytotoxicity of isolated components as MDR (multi-drug resistant) inhibitors were speculated according to the SAR as well, suggesting that TMCA group at C-6 was necessary for cytotoxicity [31].

Rescinnamine (N8) isolated from Rauvolfia, known as moderil or anaprel, was considered as an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor used as an antihypertensive drug clinically (Fig. 4) [21]. This ester exhibited significant inhibition against SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) as well. The minimal concentration of inhibition toward SARS-CoV (SARS coronavirus) was approached to be 10 μM [32]. As the analogue of reserpine, ester N8, which beared a substituted cinnamate in place of a substituted benzoate, was reported to modulate MDR [33]. Ester N8 enhanced the cytotoxic activity of natural product antitumor drugs in CEM/VLB100 cells on different dosages. Structure-function relationship revealed that compounds that retained the pendant benzoyl function in an appropriate spatial orientation all modulated MDR.

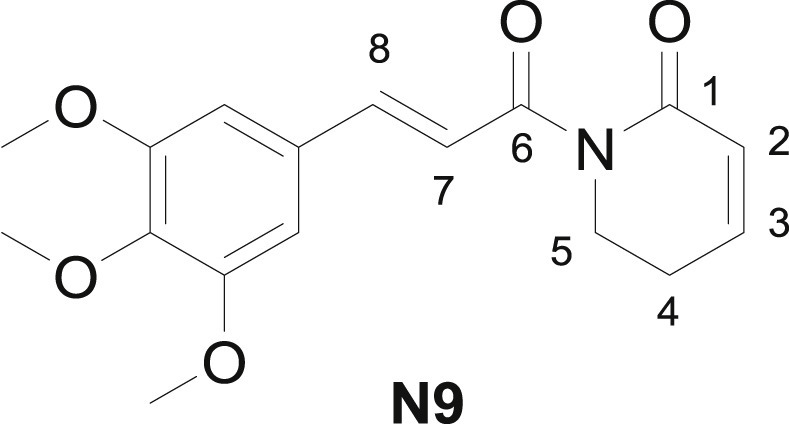

2.2. TMCA amides isolated from natural products

Piplartine (N9), also known as piperlongumine, is the most frequently reported TMCA amide isolated from Piper plants (Fig. 5 ). Piplartine has shown effective against various ailments including cancer, neurogenerative disease, arthritis, melanogenesis, lupus nephritis, and hyperlipidemic [34]. Several related molecular targets have been disclosed such as NF-κB (nuclear transcription factor-κB), MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), IL-6 (interleukin-6), JAK (janus kinase) etc.

Fig. 5.

Structure of piplartine.

3. Bioactivities of synthetic TMCA ester and amide derivatives

The structure of TMCA could be prepared by several kinds of reactions for the synthesis cinnamic acid including Perkin and Knoevenagel reaction. For the synthesis of TMCA ester and amide derivatives, coupling reactions were utilized widely. Catalysts including DCC (dicyclohexylcarbodiimide)/DMAP (4-dimethylaminopyridine), DMAP/EDCI (1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide) were commonly chosen. Sometimes TMCA was converted into cinnamoyl chloride to increase the activity of reaction.

To date, numerous TMCA ester and amide analogues have been synthesized and evaluated the bioacitivities. The largely unexplored derivatives possess a variety of pharmacological activities, ranging from antitumor, antiviral, CNS agnets, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and hematologic agents. Next, these derivatives were discussed one by one in the following paragraphs.

3.1. Antitumor activity of synthetic TMCA derivatives

Nowadays, cancer is one of the leading causes of death and unremitting efforts being made by researches to develop antitumor agents with more efficiency and safety [35]. So far, various TMCA ester and amide derivatives with antitumor effect have been reported. We summarized the progress of these active compounds as follow.

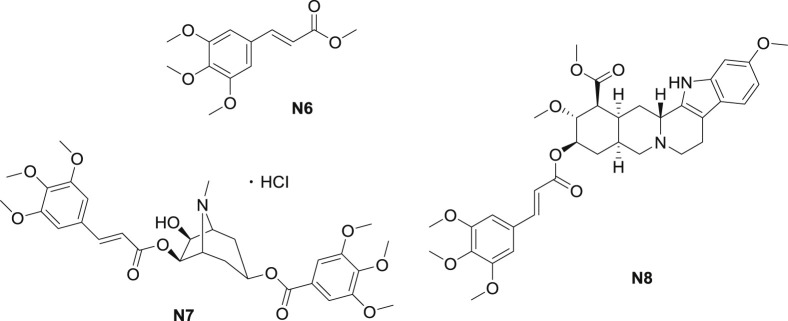

3.1.1. Synthetic TMCA esters as antitumor agents

The antitumor evaluation of a series of olive secoiridoids derivatives was carried out by Busnena and coworkers [36]. TMCA was introduced to give esterification product with tyrosol, which was the e major olive phenolic in olive oil. The result of in vitro activity demonstrated that ester S1 (Fig. 6 ) showed moderate antitumor activity against the MDA-MB231 human breast cancer cells (IC50: 46.7 μM) with the c-MET (tyrosine-protein kinase Met) inhibition as the possible mechanism. The SAR studies indicatited that function groups positioned with more hydrogen bond donor binding role of the hydroxyl groups were more conducive to the inhibitory activity compared with 3,4,5-trimethoxyl group on aromatic ring.

Fig. 6.

Structure of synthetic TMCA ester derivatives as antitumor agents (S1-S10).

MDR is a major obstacle to successful cancer chemotherapy. Ester S2, inspired by the lead compound quercetin, processed antitumor activity against MDR by modulating activity of P-gp (P-glycoprotein 1) (Fig. 6) [37]. At 1.0 μM, ester S2 showed high P-gp and BCRP- modulating activities. When ester S2 was used along to evaluate the cytotoxicity for the mentioned cell lines, no significant cytotoxicity was observed (IC50 > 100 μM). According to SAR investigation, TMCA moiety showed stronger P-gp-modulating and BCRP- modulating activities than subtittued benzoic acid esters, suggesting that the extra C=C bond on cinnamic acid group was important for the activity.

Ester S3 was also explored as MDR modulator. A series of analogues were synthesized and split as cis-trans isomer (Fig. 6) [38]. Among them, the ester S3 with the configuration for trans/cis displayed most potent MDR modulating activity, with the [I]0.5 value of 0.01 μM.

Ester S4, which was a ester derivative of methylated epigallocatechin, possessed most promising P-gp inhibition among the synthetic methylated epigallocatechin analogues (Fig. 6) [39]. Noncytotoxic ester S4 reversed drug resistance of P-gptransfected breast cancer cell line LCC6MDR (EC50: 123–195 nM). Futher study demonstrated that ester S4 inhibited the active drug efflux of P-gp transporter. The SAR investigation revealed that the derivatives substituted with TMCA group exhibited favourable activity in both cis-methylated epigallocatechin derivatives and trans-methylated gallocatechin derivatives, suggesting the potential of TMCA group promitting the activity of lead compounds.

The structure of TMCA ester was widely used for the modify of natural products. Ester S5, which was the structure of dihydroartemisinin esterified with TMCA, exhibited significant antitumor activity (Fig. 6) [40], with The IC50 values of ester S5 against cell lines: PC-3, SGC-7901, A549 and MDA-MB-435s were 17.22, 11.82, 0.50 and 5.33 μM, respectively. The cytotoxicities of ester S5 on normal hepatic L-02 cells was weak (IC50: 58.65 μM). Meanwhile, the SI (selective index) (IC50 normal/IC50 cancer) value was 117.30. As for the SAR, on the one hand, multi-methoxyl group substituted cinnamic acid esters performed better than other substituted cinnamic acid esters. On the other hand, diester derivatives exhibited stronger inhibitory activity than compounds with bare hydroxy on the C-9 of dihydroartemisinin in general according to the pharmacological results.

Nam et al. [41] executed the esterification of 4-senecioyloxymethyl-6, 7-dimethoxycoumarin, which was a metabolite of the plant plant Crinum latifolium. Ester S6 showed moderate cytotoxicity on B16 and HCT116 cell lines with the IC50 values of 6.74 and 8.31 μg/mL (Fig. 6) [30]. The most promising ester was the 4-methoxycinnamoyl substituted derivative S7, which was structurally similar to ester S6.

Based on the structure of the precursor 2′,5′-dimethoxychalcone, a series of ester derivatives were synthesized [42]. Among them, ester S8 possessed broad spectrum antitumor activity in different cell lines (Fig. 6). When ester S8 was added in cell lines including A549, Hep 3B, HT-29 and MCF-7, the IC50 values were 36.7, 23.2, 23.8 and 6.4 μM, respectively. Further research suggested that this cluster of esters could mediate cancer cell apoptosis via G2/M arrest.

Ester S9 was designed based on a cytotoxic natural ester isolated from Piper sintenense (Fig. 6) [43]. In several cell models including PC-3, Hela, A549 and BEL7404, ester S9 possessed cytotoxicity with the IC50 values of 80, 64, 172 and 212 μM, respectively.

Han et al. [44] synthesized fumagillin analogues according to molecular modeling with MetAP2 (human methionine aminopeptidase-2). Among them, ester S10 exhibited the strongest antitumor activity in EL-4 and CPAE cells, with the IC50 values of 0.15 and 0.03 μg/mL (Fig. 6), respectively. Ester S10 interacted well with MetAP2 according to the docking study. In subsequent study, ester S10 was demonstrated to inhibit MetAP2 significantly with the IC50 value of 0.96 nM [45]. The SAR of the synthetic fumagillin analogues could be summarized as that the aromatic ring of the derivatives should be positioned to contact with the Leu447 of human MetAP-2 for maximizing hydrophobic interaction, and the activity of cis-cinnamic acid ester derivative was much less than trans-cinnamic acid ester derivatives.

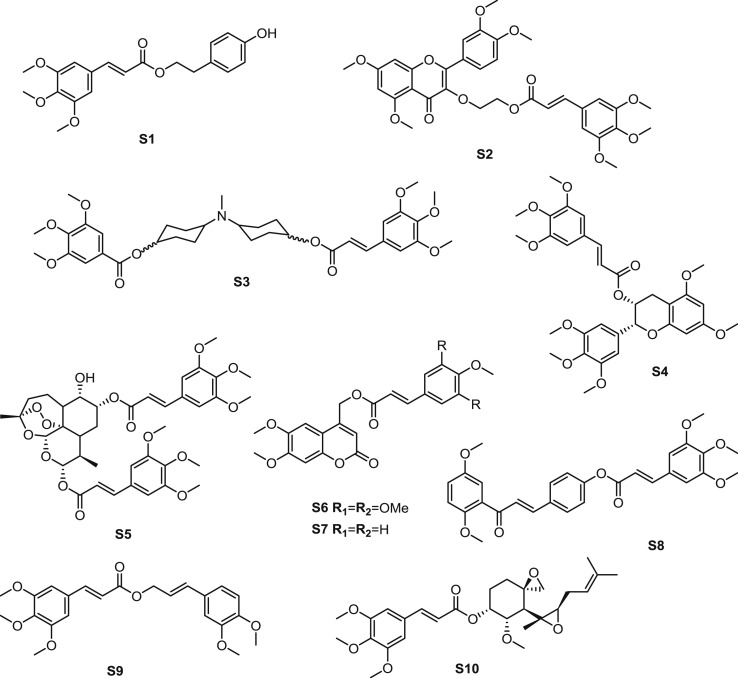

3.1.2. Synthetic TMCA amides as antitumor agents

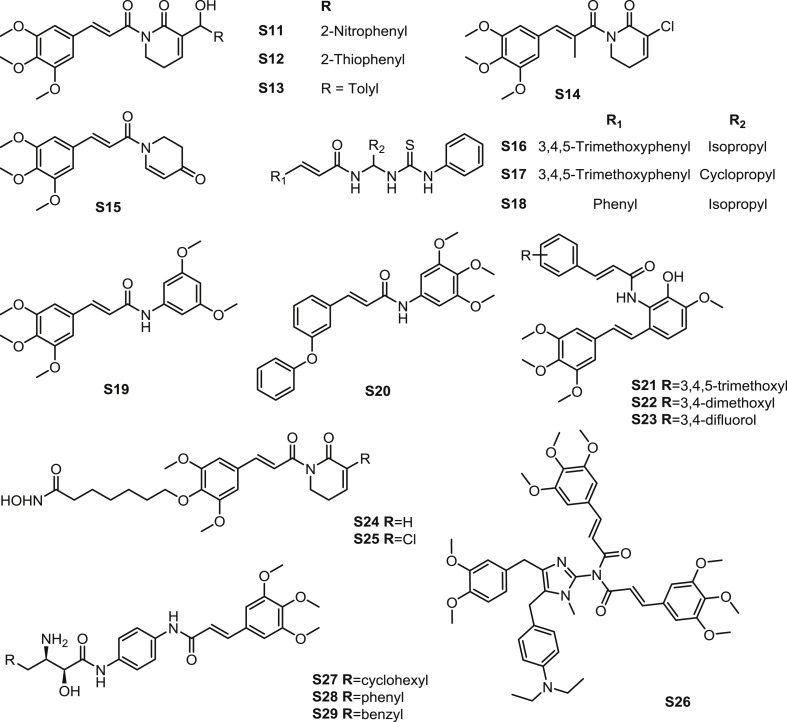

Piplartine was modified on heterocyclic ring via Baylis-Hillman reaction. The derivatives were determined anticancer activity [46]. In HeLa and IMR-32 cells, amides S11–13 were demonstrated to enforced cell cycle inhibition arresting cells in G2-M phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 7 ). The enhanced ERK1/2, MAPK activation was significant when the potent compounds were used along or combined with chemotherapeutic drugs. In the combination treatment with colcemid and hydroxyurea, the enhanced elongation and inhibition of cell adhesion in both the cells were observed.

Fig. 7.

Structure of synthetic TMCA amide derivatives as antitumor agents (S11-S29).

Multiple piplartine analogues with alkyl or halogen substituents at C-7 and morpholine substituents at C-2 were prepared by Wu et al. [7]. All the compounds showed modest selectivity for WI38 human fetal lung normal cells and MRC-5 human lung normal cells. Among the synthetic compounds, amide S14 (Fig. 7) displayed most potent inhibitory against four cancer cells in vitro (Table 2 ). Subsequently, amide S14 exerted significant antitumor potency in ROS (reactive oxygen species) elevation and excellent. SAR suggested that 2-Halo-7-alkylpiperlongumines retained in vitro anticancer activity, while analogue with morpholine substituents at position 7 of piplartine exhibited diminished cytotoxicity.

Table 2.

Antitumor activity of S14in vitro.

| Amides | IC50 (μM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | HCT116 | MDA-MB-231 | Hep3B | WI38 | |

| S14 | 3.94 | 9.85 | 6.07 | 16.69 | 19.60 |

| Piplartine | 5.90 | 21.80 | 19.53 | 69.46 | 26.78 |

Based on the structure of piplartine and cenocladamide, a series of analogues were synthesized by Santos et al. [47]. Amide S15 was identified as the most promising compound against MDA-MB-231 cells (IC50: 6.6 μM) (Fig. 7). Additionally, amide S15 also induced apoptosis on several tested cell lines (efficacy: 15%–80% of apoptosis), which was superior to the positive control doxorubicin. The proliferating inhibition also showed selectivity, because amide S15 was proved to be unconspicuous cytotoxicity to the non-tumorigenic cells including iHMEC and MCF10A.

Zeng et al. [48] synthesized multiple N, N-disubstituted thiourea analogues as the inhibitors of HSP70 (heat shock protein 70). Amides S16 and S17 (Fig. 7), which were the molecules contained TMCA amide group, exhibited favourable inhibition against HSP70 with the ratio of 50.42% and 50.45% in 200 μM. Amide S18 was the most potent compound with the percentages of inhibition of 65.36. Furthermore, amide S18 induced M-phase arrest in HL-60/VCR cells and was proved that it was not the substrate of P-glycoprotein drug transporters.

A series of phenylcinnamides were synthesized and assessed the antitumor activity [49]. Among them, amide S19 showed moderate antitumor effect against U-937 and HeLa cells with IC50 values of 9.7 and 38.9 μM (Fig. 7), respectively. The most potent amide S20, C-4 position on benzene etherification analogue, exerted apoptosis effect with IC50 values of 1.8 and 2.1 μM for the mentioned two kinds of cell lines, respectively.

According to the structure of Combretastatin A-4, a precursor exhibited cytotoxic effect against murine lymphocytic leukemia, a series of derivatives with higher aqueous solubility were designed and synthesized [50]. Among them, amide S21 (Fig. 7), a TMCA amide, showed favourable antitumor activity against several kinds of cell lines (Table 3 ). The most potent amides S22 and S23 were structurally similar to S21. SAR indicated that 3,4-substituted on benzene of the cinnamide was helpful to promote apoptosis activity.

Table 3.

Cytotoxic activity (Concentration of drug causing 50% inhibition of cell growth) data of amides, S21, S22, S23 and CA-4 by SRB method.

| Com. | MCF7 | DU145 | HOP62 | HeLa | K562 | SK-OV-3 | Colo205 | MIA-PaCa-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S21 | 0.079 | 0.095 | 24.8 | 14.9 | 28.0 | 20.9 | 76.0 | 64.5 |

| S22 | 0.056 | 0.060 | 0.090 | 7.5 | 0.094 | 0.099 | 0.099 | 29.9 |

| S23 | 0.031 | 0.045 | 43.6 | 29.2 | 0.099 | 29.8 | 74.9 | 74.0 |

| CA-4 | 0.033 | 0.046 | 0.15 | 0.008 | 0.031 | 31.6 | 0.025 | – |

Inspired by the structure of piplartine and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, which was a kind of HDACi (histone deacetylase inhibitor), active antileukemic amides S24 and S25 were synthesized (Fig. 7) [8]. Amide S24 were reported to mediate DNA damage and apoptosis. Subsequently, amide S25, which was an analogue introduced C2-chloro substituent to S25, improved apoptosis activity but redcued selectivity in noncancerous MCF-10A cell lines. amides S24 and S25 also performed antileukemic activity through mediating pro-apoptotic proteins expression, inhibiting DNA repair and pro-survival proteins expression, and interfering cellular GSH (glutathione) defense.

Zhang et al. developed a Namidine scaffold framework as MDR modulator [51]. Amides S26, which was an analogue with two units of 3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)acryloyl in the molecule structure, was proved to be the most potential compound among the derivatives (Fig. 7). Amide S26 (1 mM) sensitized LCC6MDR cells toward Taxol 24.5 folds (EC50: 210.5 nM), which was more potent than verapamil.

TMCA amides were considered to be bestatin-based inhibitor of MetAP2 and inhibitor against HUVECs (human umbilical vein endothelial cells) [52]. A series of α-hydroxy-β-amino amide analogues were synthesized and evaluated inhibition against MetAP2 and HUVEC growth. Amides S27-29 (Fig. 7), which were TMCA amide analogues, exhibited significant inhibitory effect (Table 4 .). When the R group was substituted with benzyl group, both MetAP2 and HUVEC growth inhibition were favourable. When TMCA moiety were replaced with other group, the inhibition against MetAP2 and HUVEC growth can not be ensured at same time.

Table 4.

Enzyme and cellular activities of amides S27, S28 and S29.

| Com. | IC50 MetAP2 (nM) | GI50 HUVEC (μM) | GI @ 5 μM HUVEC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S27 | 177 | 0.67 | >98 |

| S28 | 755 | – | 93 |

| S29 | 67 | 0.85 | >98 |

3.2. Antiviral activity of synthetic TMCA derivative

A variety of virus widely exist in the nature and threaten public health. TMCA is using to design antiviral agents, involving to anti-HBV (hepatitis B virus), anti-SARS and anti-influenza A agents. To date, nearly all the reported effective antiviral analogues are TMCA esters.

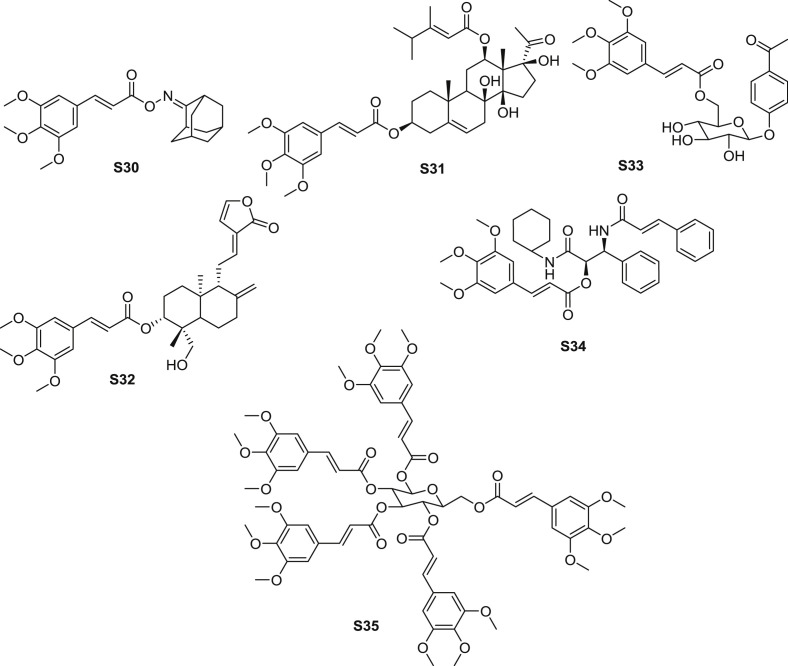

Sixteen phenylpropionic acid analogues were prepared and screened for the anti-HBV effect [53]. Ester S30 (Fig. 8 ) displayed the outstanding HBV inhibitory, with the CC50 (half cytotoxicity concentration) value of 506.99 μM in HepG2 2.2.15 cells, and IC50 values of HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen) and HBeAg (hepatitis Be Antigen) were 107.19 and 74.80 μM, respectively.

Fig. 8.

Structure of synthetic TMCA derivatives as antivival agents (S30-S35).

Research group of Jijun Chen synthesized numerous of natural-based compounds and measured their anti-HBV activity, several TMCA esters exhibited anti-HBV activity in the studies (Table 5 ). Caudatin, an effective anti-HBV precursor tetracyclic triterpenoid separated from Cynanchum bungee, was modified with cinnamic acid and measured for anti-HBV activity. Ester S31 (Fig. 8) exhibited most potent for anti-HBV activity, with the CC50 value of 1821.75 μM in HepG2 2.2.15 cells, and both the IC50 values of HBsAg and HBeAg were 5.52 μM. With the highest SI value of 330. The IC50 value of S31 inhibiting HBV DNA replication was 53.1 μM [54]. Ester S32 (Fig. 8), which was an esterified derivative from andrographolide, also performed moderate anti-HBV effect, with the CC50 value of 211 μM in HepG2 2.2.15 cells, and the IC50 values of HBsAg and HBeAg were 753 and 518 μM, respectively. The IC50 value of S32 inhibiting HBV DNA replication was 53.1 μM. TMCA was considered as one of the group which was favourable to enhance anti-HBV activity according to SAR [55].

Table 5.

Anti-HBV activity and cytotoxicity of esters S30, S31, S32 and S33.

| Com. | CC50 (μM) | HBsAg |

HBeAg |

DNA replication |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM) | SI | IC50 (μM) | SI | IC50 (μM) | SI | ||

| S30 | 506.99 | 107.19 | 4.73 | 74.80 | 6.78 | 141.46 | 3.58 |

| S31 | >1821.75 | 5.52 | >330.0 | 5.52 | >330.0 | 2.44 | >746.6 |

| S32 | 211 | 753 | – | 518 | 1.6 | 53.1 | 3.0 |

| S33 | >2423.5 | 285.7 | >8.5 | >2423.5 | – | 114.9 | >21.1 |

p-Hydroxyacetophenone, isolated from Artemisia capillaris, was explored as the precursor for the anti-HBV agent. A series of anlogues were synthesized and identificated through the Mitsunobu reaction on the primary hydroxyl group of pyranose. Among the synthetic compounds, ester S33 (Fig. 8) exhibited strongest anti-HBV DNA replication effect, with the CC50 value of 1821.75 μM in HepG2 2.2.15 cells, meanwhile, the IC50 value of S33 inhibiting HBV DNA replication was 5.8 μM, SI = 330 [56]. The SAR can be concluded that glycosides showed stronger inhibitory activity than aglycones in general, meanwhile, the cinnamic acid analogues positioned with methoxyl or fluoro group exhibited more potential activity than other substituted analogues.

According to the structure of effective ester tetrapeptide aldehyde against SARS, a series of derivatives were synthesized. Ester S34 (Fig. 8) showed weak anti-SARS CoV 3CL R188I mutant protease effect (IC50: 250 μM) [57]. Interestingly, according to another research result from the author [58], TMCA amide analogue was reported to be the most promising compound among the designed derivatives. The author considered that planar aromatic ring and its hydrophobic functionality on the structure of substituted group were essential for the inhibitory activity.

Inspired by the structure of penta-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose, several derivatives were synthesized and determined for the anti-influenza A activity [59]. Compared with 3,4,5-trimethoxy benzoic acid substituted derivatives, ester S35 showed stronger inhibition against influenza A. Ester S35 (Fig. 8), which was composed by d-Mannose and five units of TMCA, showed most potent anti-influenza A effect. As for the configuration, ester S35 was the mixture of α- and β-anomer, with the ratio of α/β = 63/37.

3.3. CNS agents of synthetic TMCA derivative

CNS disorders, which are made up of multiple diseases whose symptoms contain cognitive impairment and maniac or depressive behavior, affected millions of people around the world [60]. Because of the complexity of pathogenesis, development of CNS agents is high investment but low returns. Coherent with the bioactivity of precursor TMCA, TMCA ester and amide analogues have been reported to show CNS activity including antinarcotic, neuroprotective anti-Alzheimer and anticonvulsant effect. Several targets are involved to such as 5-HT (5-hydroxytryptamine), Ache (acetylcholine), BuChe (butyrocholinesterase), Aβ (1–42), EP2 and Nrf2 (nuclear factor 2).

3.3.1. Synthetic TMCA esters as CNS agents

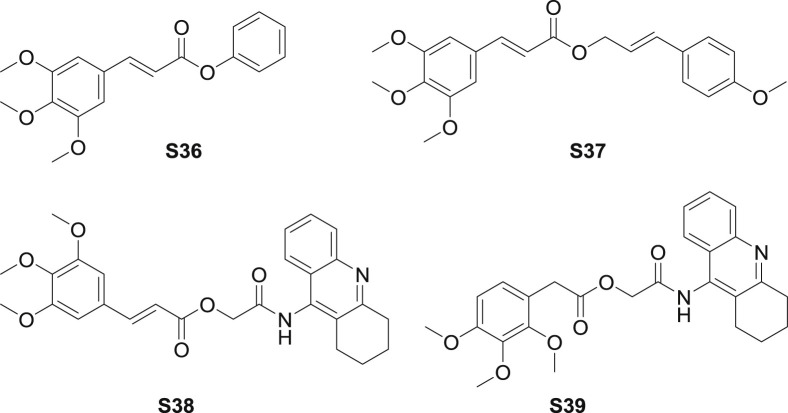

In 2013, a series of TMCA analoges were synthesized and examined the antinarcotic activity [61]. Ester derivatives were synthesized by acyl chlorination of TMCA, among which ester S36 (Fig. 9 ) exhibited moderate antinarcotic in vivo and in vitro. At the dose of 20 kg/mg, S36 suppressed naloxone-stimulated jumping behavior in morphine-dependent mice. Moreover, S36 inhibited 5-HT1A with the IC50 value of 9.4 μM.

Fig. 9.

Structure of synthetic TMCA ester derivatives as CNS agents (S36-S39).

According to the structure of Sintenin, a lignanoid isolated from Piper sintenense, Jung et al. [62] synthesized multiple ester analogues. The neuroprotective effect of the synthetic esters was determined in in vitro models. Ester S37 (Fig. 9) showed moderate neuroprotective activity in DPPH (1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazylradical2,2-Diphenyl-1-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)hydrazyl) radicals scavenging model, with the inhibition for 18.60% at 50 μg/mL, which was higher than the positive control quercetin. Further study revealed that caffeic acid substituted ester showed the most potent neuroprotective effect through suppressing the H2O2-induced oxidative injury in PC12 cells.

Ester S38 (Fig. 9), which was a esterified derivative of active lead compound-tacrine, was confirmed to show potential against Alzheimer's disease [63]. To detail, S38 showed inhibitor against AChe, BuChe and Aβ (1–42) aggregation with IC50 values of 16.88, 298.9 and 45.88 μM, respectively. The most active ester S39, which also containing trimethoxybenzene moiety, showed AChe inhibition (IC50: 5.63 μM, 13 times stronger than tacrine). The SAR investigation suggested that electron-withdrawing substituents on the benzene ring of cinnamate were not conductive to improve the inhibitory activity of AChe, BuChe and Aβ (1–42) aggregation.

3.3.2. Synthetic TMCA amides as CNS agents

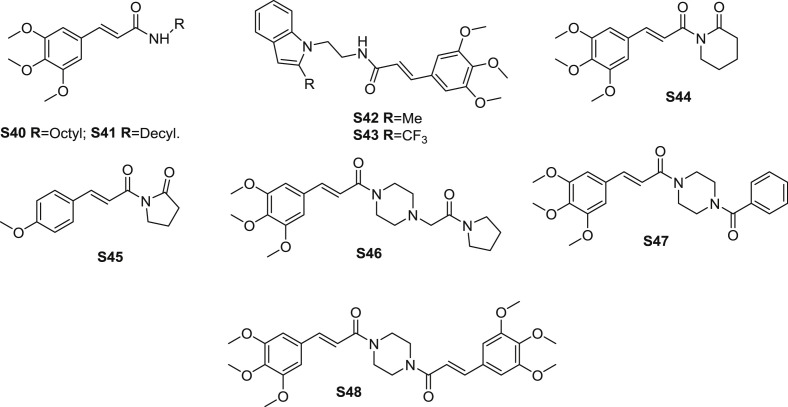

Jung et al. [5] synthesized several TMCA amides and measured the antinarcotic activity. The reaction details about preparation of TMCA were described. Among the homologous, amides S40 and S41(Fig. 10 ) were the most potential amides in vivo and in vitro. At the dose of 5 mg/kg (i.p.), S40 and S41 significantly decreased the naloxone-induced jumping behavior in morphine-dependent mice, with the inhibition ratio values of 88% and 80%, respectively. In vitro, S40 and S41 exhibited favourable binding affinity to serotonergic receptors such as 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT6, 5-HT7, and the 5-HT transporter (Table 6 ). Amide S40 displayed the most significant binding affinity to the 5-HT1A receptor. Additionally, S41 possessed different binding affinity to mentioned receptors. Ability of activating the pERK expression for the amides was also determined. The result indicated that amides S40 and S41 moderately increased the expression of pERK.

Fig. 10.

Structure of synthetic TMCA amide derivatives as CNS agents (S40-S48).

Table 6.

Serotonin (5-HT) receptor and transporter binding afnities of amides S40 and S41.

| Compound | Receptor binding affinity (IC50, μM) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 5-HT2A | 5-HT2C | 5-HT6 | 5-HT7 | 5-HT transporter | |

| S40 | 1.2 | >10 | 8.8 | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| S41 | 2.1 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 6.7 |

| TMCA | 7.6 | >10 | 2.5 | >10 | >10 | >10 |

Amide S42 (Fig. 10) was reported to be effective in inhibiting seizure-induced mediation of neuronal injury by PGE2 (prostaglandin E2) receptor subtype EP2 [64]. As the most potent molecular in the synthetic analogues, S42 possessed competitive antagonism of EP2 receptor (KB: 2.4 nM), meanwhile, the EP4 (prostaglandin E2 receptor 4) receptor KB value was 11.4 μM, and the SI was 4730. Furhermore, S42 as a brain-permeant agent inhibted the up-regulation of COX-2 (prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2) mRNA in rat cultured microglia activated by EP2 and markedly decreased neuronal injury in hippocampus when administered in mice beginning 1 h after termination of pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. The result revealed that S42 was effective in treating inflammation-related brain injury. Based on the structure of S42, amide S43 was synthesized and evaluated the selectivity against prostanoid receptor EP2 and DP1.

A series of piplartine analogues were synthesized and measured cytoprotection against hydrogen peroxide- and 6-hydroxydopamine-induced neuronal cell oxidative damage in PC12 cells [65]. Amides S44 and S45 (Fig. 10) showed low cytotoxicity and confer potent protection of PC12 cells from the oxidative injury via upregulation of a panel of cellular antioxidant molecules. Genetically silencing the transcription factor Nrf2, a master regulator of the cellular stress responses, suppresses the cytoprotection, indicating the critical involvement of Nrf2 for the cellular action of S44 and S45 in PC12 cells.

Cinepazide (S46) (Fig. 10) is a marketed drug using for the treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and peripheral vascular diseases. Cinepazide can also be regarded as a TMCA amide analogue. Amide S46 was suggested to protect PC12 neuronal cells by affecting mitochondrial functions [66]. To detail, S46 inhibited OGD (oxygen–glucose deprivation)-induced oxidative stress, as supported by its capability of reducing intracellular reactive oxygen species and malondialdehyde production and enhancing superoxide dismutase activity. Furthermore, S46 was found to sustain the function of mitochondrial function via stabilizing mitochondrial membrane potential, promoting OGD-induced suppression of mitochondrial respiratory complex activities and enhancing ATP (adenosine-triphosphate) production.

Jung and coworkers [67] presented a simple synthesis TMCA amides and evaluated the bioactivities. All the synthesic amides were determined the radical scavenging activity, neurotoxicity inhibition and antinarcotic activity. No significant radical scavenging activity was observed for the tested amides compared to the reference material in vitro. Amide S47 (Fig. 10) showed most potent neuroprotective activity in glutamate-induced primary cortical neuronal cells at the doses ranging from 5 to 20 μM. Meanwhile, all the analogues showed antinarcotic property in vivo. Amide S48 displayed strongest inhibition among the examed amides, which indicated that TMCA moiety was essential for the enhancement of antinarcotic activty.

3.4. Antimicrobial activity of synthetic TMCA derivatives

TMCA ester ester and amide analogues are applied to synthesize antimicrobial agents as well. Active derivatives have been reported to suppressed the growth of strains including Ustilaginoidea oryzae, Pyricularia oryzae, P. falciparum, S. aureus, C. krusei and Trypanosoma cruzi.

3.4.1. Synthetic TMCA esters as antimicrobial agents

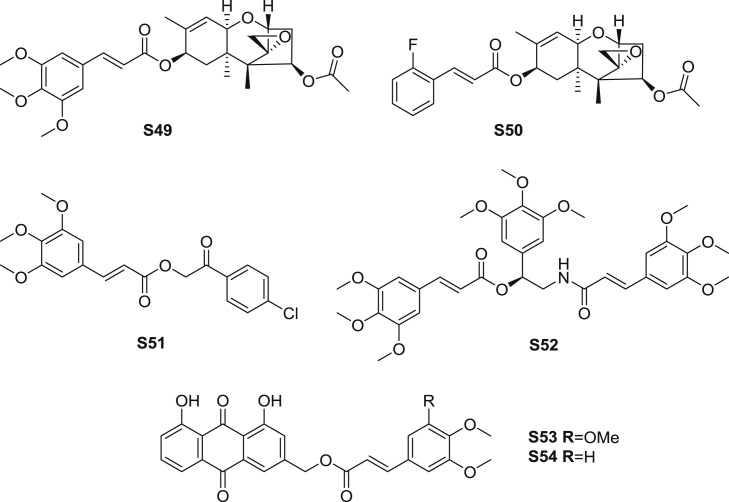

Trichodermin cinnamic acid ester derivatives were prepared and by Zheng et al. [68]. Among the obtained compounds, ester S49 (Fig. 11 ) exhibited moderate inhibition against Ustilaginoidea oryzae and Pyricularia oryzae in vitro, with the EC50 values of 11.04, and 11.07 μM, respectively. Ester S50, which was a derivative substituted with ortho-fluorine cinnamic acid, exhibited prodominent inhibition against mentioned strains, with the EC50 values of 0.56, and 0.53 μM, respectively. The effect was even better than the marketed drug prochloraz, which could be related with the function of the fluorine moiety in inhibiting microbials [69].

Fig. 11.

Structure of synthetic TMCA amide derivatives as antimicrobial agents (S49-S54).

Several studies have reported esters including TMCA moiety possessed antimalarial effect, which indicated that TMCA could be an important group for developing antimalarial agents. As an analogue of neolignane, ester S51 (Fig. 11) was identified and measured the antimalarial activity in vitro [70]. The result revealed that S51 exhibited moderate antimalarial activity against blood forms of chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum with both the IC50 values for 3H-hypoxantine and HRPII were 127.9 μM.

In an anticipation of powerful antimalarial activity, Aratikatla et al. [71] exploited a series of syncarpamide analogues and investigated the efficacy in vivo and in vitro. Among the synthetic compounds, ester S52 (Fig. 11) displayed the strongest inhibition for 3D7 and K1 strains of P. falciparum, with the IC50 values of 1.89 and 1.93 μM, respectively. Unfortunately, there was no significant effect for S52 inhibiting N-67 strain of Plasmodium in vivo.

Dai et al. [72] modified the structure of Kniphofiones A and B, which were two lead compounds separated from Kniphofia ensifolia. Ester S53 (Fig. 11) was reported to show marked antiplasmodial effect against Dd2 chloroquine-resistant strain of P. falciparum (IC50: 2.7 μM). The most potent ester S54 was structurally similar to S53, and the IC50 value of S54 was 1.3 μM. Ester S54 exerted 7 and 20 times the efficiency of Kniphofiones A and B.

3.4.2. Synthetic TMCA amides as antimicrobial agents

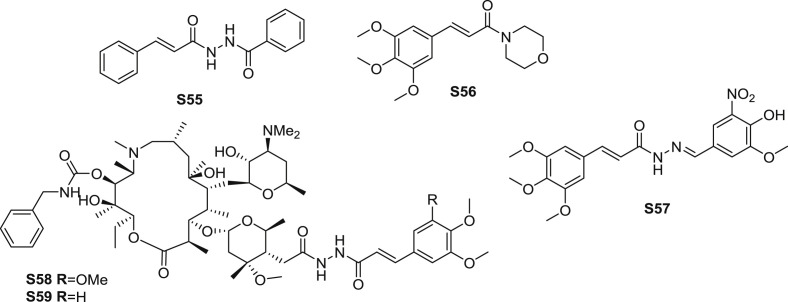

Fregnan et al. [73] synthesized several analogues of piplartine and evaluated the antimicrobial activity of the analogues. Amides S55 and S56 (Fig. 12 ) were the most potent amides (Table 7 ). Amide S55 displayed three-fold more potent than piplartine in antibacterial evaluation against S. aureus and five-fold less toxic than piplartine. Amide S56 possessed fourfold more potent in antifungal evaluation against C. krusei and five-fold less toxic than piplartine. As for the SAR, it was possible to note that an aromatic ring lacking methoxyl moieties is important for the antibacterial activity of these compounds. On the other hand, trimethoxyphenyl group substituted on benzene ring was imperative for the antifungal activity.

Fig. 12.

Structure of synthetic TMCA amide derivatives as antimicrobial agents (S55-S59).

Table 7.

Antimicrobial activity of amides S55 and S56.

| Com. | Fungus |

Bacteria |

CC50 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans ATCC 10231 | C. tropicalis ATCC 750 | C. krusei ATCC 6258 | C. glabrata ATCC 90030 | C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 | S. aureus ATCC 6538 | BHK-21 | |

| S55 | 375.79 (0.61)a | 375.79 (0.61) | -b | 375.79 (0.61) | 375.79 (0.61) | 85.20 (2.71) | 231.71 |

| S56 | – | 97.67 (1.89) | 48.83 (3.79) | – | – | – | 185,55 |

| Piplartine | 94.60 (0.42) | – | 189.20 (0.21) | 189.20 (0.21) | 94.60 (0.42) | 315.33 (0.12) | 40.14 |

IC50 (SI).

Inactive at highest evaluated concentration.

Carvalho et al. [74] synthesized several cinnamic N-acylhydrazones and measured the antitrypanosomal effect. Amide S57 (Fig. 12) exhibited modest antitrypanosomal activity against trypomastigote forms of Trypanosoma cruzi with the IC50 value of 18.4 μM. The value of SI of S57 was the highest of 134. Moreover, possessed favourable cruzain inhibition with the IC50 value of 45.9 μM.

Derivatives of 4″-O-(trans-β-arylacrylamido)carbamoyl azithromycin were synthesized and assessed for their antibacterial effect against nine significant pathogens [75]. Amide S58 (Fig. 12) exhibited moderate antibacterial effect against susceptible and resistant strains (Table 8 ). The most potent amide S59 was structurally close to S58, which revealed that 3,4-dimethoxyl substituted moiety enhanced the antibacterial activity for the lead compound.

Table 8.

Antimicrobial activity of amides S58 and S59.

| Com. | S. aureus ATCC25923 | S. pneumoniae ATCC49619 |

S. pyogenes S2 |

S. aureus | S. aureus ATCC29213 |

S. pyogenes R2 |

S. pneumoniae A22072 |

S. pneumoniae AB11 |

S. pyogenes R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S58 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 32 | 2 | 16 | 64 |

| S59 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 2 | 4 | 64 | 2 | 64 | 64 |

| Azithromycin | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 1 | 128 | 4 | 256 | ≥128 |

3.5. Anti-inflammatory activity of synthetic TMCA derivatives

Inflammation is body's natural response against external infection. [76]. TMCA ester and amide derivatives have been reported to show anti-inflammatory activity through the targets including TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor), NO (nitric oxide) and NF-κB.

3.5.1. Synthetic TMCA esters as anti-inflammatory agents

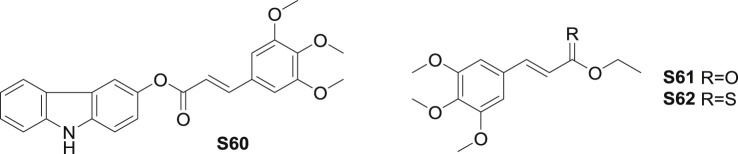

Ku et al. [61] combined carbazole with cinnamoyl group and measured the vascular barrier protective effects of derivatives. Ester S60 (Fig. 13 ) exhibited marked inhibition on HMGB1 (high mobility group box-1 protein)-mediated hyperpermeability. At the dose of 10 μM, S60 inhibited hyperpermeability with the most remarkable inhibition of 70.2% and ELISA OD650 value of 0.158. On mice model, also suppressed HMGB1-mediated hyperpermeability with the inhibition of 58.9%. The result demonstrated that S60 could be a potent agent for inhibiting HMGB1-mediated inflammatory responses.

Fig. 13.

Structure of synthetic TMCA ester derivatives as anti-inflammatory agents (S60-S62).

Kumar et al. [77] reported that ester S61 (Fig. 13) isolated from Piper longum inhibited ICAM-1 (intercellularcelladhesionmolecule-1), VCAM-1 and E-selectin by the induction of TNF-α. As one of the thionocinnamate homologs, S62 exhibited better inhibition than S61. On the concentration of 20 μg/mL, S62 exerted 95% inhibition of ICAM-1 expression (IC50: 10 μg/mL). Consequently, S62 abolished adhesion of neutrophils to endothelial monolayer by the induction of TNF-α. SAR investigation indicated that the critical role of the chain-length of the alkyl moiety in the alcohol moiety, number of methoxy groups in the aromatic ring of the cinnamoyl moiety and the presence of the α, β- C-C double bond in the thiocinnamates and thionocinnamates.

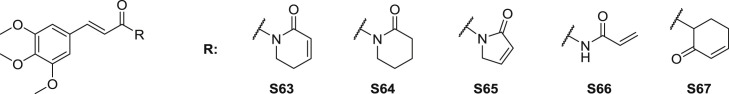

3.5.2. Synthetic TMCA amides as anti-inflammatory agents

A series analogues of piplartine (S63) were synthesized and investigated the anti-inflammatory activity [76]. Among them, amide S63-66 (Fig. 14 ) exhibited better inhibition. At the dose of 10 μM, LPS (lipopolysaccharide)-induced NO production was inhibited by four mentioned amides with the inhibition of 91%, 46%, 65% and 41%, respectively. Additionally, the cytotoxicity of four amides in RAW264.7 macrophages was measured with the IC50 values of 3, 6, 14 and 17 μM, respectively.

Fig. 14.

Structure of synthetic TMCA amide derivatives as anti-inflammatory agents (S63-S67).

Sun et al. [78] designed and synthesized several piplartine derivatives. Analogue S67 (Fig. 14), which was the ketone analogue with amide group replaced by carbonyl to increase its electrophilicity, was certified to show more potential than the lead amide piplartine in blocking LPS-induced secretion of NO and PGE2 as well as COX-2 and iNOS (inductive nitric oxide synthase) expressions in RAW264.7 macrophages.

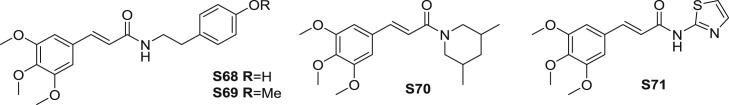

3.6. Hematologic activity of synthetic TMCA derivatives

TMCA amides have been revealed to show hematologic activity, in which anti-aggregatory and haemostatic effect are the relative effects.Substituted cinnamoyl-tyramine analogues were synthesized and evaluated the platelet anti-aggregatory activity [79]. Among the synthetic derivatives, amides S68 and S69 (Fig. 15 ) exhibited moderate platelet anti-aggregatory activity. At the dosage of 20 μg/mL, amides S68 and S69 suppressed PAF (platelet-activating factor) receptor binding to rabbit platelet with the inhibition of 12 and 19%, respectively (Table 9 ). On the concentration of 30 μg/mL, S68 and S69 inhibited PAF induced platelet aggregation with the inhibition of 28.8 and 39.3%, respectively. In addition, at the dose of 50 μg/mL, amides S68 and S69 inhibited PAF induced platelet aggregation with the inhibition of 24.4 and 29.1%, respectively. SAR suggested that 3,4-dimethoxycinnamoyl group could be the beneficial for the platelet anti-aggregatory activity.

Fig. 15.

Structure of synthetic TMCA derivatives as hematologic agents (S68-S71).

Table 9.

Platelet anti-aggregatory activity of amides S68 and S69.

| Com. | Inhibition (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PAF receptor binding to rabbit platelet | ADP induced platelet aggregation | PAF induced platelet aggregation | |

| Dose | 20 μg/mL | 30 μg/mL | 50 μg/mL |

| S68 | 12 | 24.4 | 28.8 |

| S69 | 19 | 29.1 | 39.3 |

To investigate the aggregation inhibition of piplartine and its analogues, a seires of derivatives of piplartine were synthesized by Park et al. [80]. Among the derivatives, amide S70 (Fig. 15) displayed the most promising platelet aggregation inhibitory effect in different models (Table 10 ). SAR research revealed that adding a methyl group to the C-2 position of the piperidine ring exerted mixed effects, promoting inhibitory effect for thrombin and collagen-induced platelet aggregation but reducing inhibition to arachidonic acid-induced platelet aggregation.

Table 10.

Platelet anti-aggregatory activity of amide S70.

| Com. | Conc. (μM) | Inhibition (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen (2 μg/mL) | Arachidonic acid (100 μM) | PAF (10 nM) | Thrombin (100 μM) | ||

| S70 | 300 | 98.6 | 100 | 94.8 | – |

| 150 | 97.2 | 100 | 56.9 | – | |

| Piplartine | 300 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 23.5 |

| 150 | 100 | 76.4 | 100 | – | |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 300 | 5.8 | 100 | 0.3 | – |

| 150 | – | 75 | 0.3 | – | |

Ten new cinnamamide derivatives containing a 2-aminothiazole substructure were presented as potent haemostatic agents [81]. Among the studied series, amide S71 (Fig. 15) exhibited coagulation activity to a certain extent. Amide S71 promoted platelet aggregation (IC50: 18.09 μmol/L) more potent than etamsylate. Amide S71 showed lowest TT (thrombin time) value among the analogues, moreover, S71 improved platelet aggregation relative to etamsylate while promoting APTT (activated partial thromboplastin time) and PT (prothrombin time), suggesting that S71 showed haemostatic activity by stimulating fibrinogen or promoting fibrin and activating platelet aggregation.

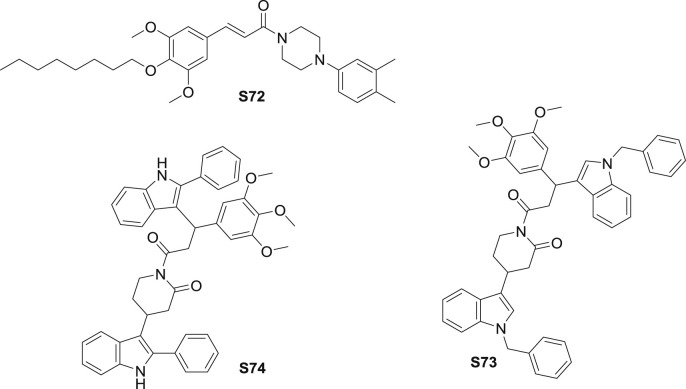

3.7. Other activities of synthetic TMCA derivatives

Apart from the bioactivity described above, TMCA amide derivatives exhibited ACAT (O-acyltransferase) and ALR2 (aldose reductase) inhibitory as well. A series of Yakuchinone B derivatives were synthesized and assessed the lipid-lowering activity [9]. As the most promising amide, in vivo, amide S72 (Fig. 16 ) inhibited rat hepatic cholesterol ACAT more significant than positive control and it exerted remarkable hypocholesterolemic activity. Subsequent research implicated that S72 from male rats could be better metabolized than those from females [82]. Sex-related different CYP3A2 expression in the toxicology research relevant to decreased accumulation and metabolism of S72 in female rats.

Fig. 16.

Structure of synthetic TMCA derivatives for other activities (S72-S74).

Piplartine was proved to suppress recombinant human ALR2 (IC50: 160 μM) [6]. To improve the activity, multiple derivatives were prepared by modificating styryl/aromatic and heterocyclic ring functionalities. S73 and S74(Fig. 16) synthesized by Michael addition exhibited aldose reductase inhibitor effect, with the IC50 value for 4 μM. Notably, according to SAR study, double bond and 3,4,5-trimethoxy substitutions at aromatic ring are important characteristics for ARI effect.

4. Conclusion

Up to now, esterification and amidation still play a significant role in discovering and developing new drugs. Amide bond formation dominated the most frequently used reaction to give the production even though the new synthetic reactions are spring up [83]. Compared with other modifications, esterification and amidation are easy to exert the metabolic characteristic of lead compounds, moreover, esterification and amidation can be easily controlled for industrial scale production for the targets compounds. Currently, the difficulty to develop new drugs is to discover novel lead compounds instead of synthsis.

As for the promising precursor TMCA, it is clearly evident that TMCA ester and amide analogues possess diversified biological activities and have immense potentiality in the field of medicinal chemistry from the above discussion. This review article is focused on the pharmacological activities of natural and synthetic TMCA ester and amide derivatives for various therapeutic targets reported recently. The present survey indicates that TMCA ester and amide derivatives have been targeted for their antitumor, antiviral, CNS agnets, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and hematologic agents. There is much scope in this potent TMCA ester and amide moiety for other therapeutic targets, future investigations of the scaffolds could give some more encouraging results in the field of medicinal chemistry. It is not to be neglected that esters generally perform poor pharmacokinetics and limited druggability [84], so there are still gaps waiting for overcoming when TMCA derivatives are developed to the marketed drugs.

It is anticipated that the information compiled in this review article not only update researchers with the recent reported biological activities of TMCA ester and amide analogues derivatives, but also motivate them to design and synthesize promising TMCA ester and amide with improved medicinal properties.

Disclosure

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in Universities, Ministry of Education of China (IRT_15R55), the 7th Group of Hundred-Talent Program of Shaanxi Province (2015), and Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province, China (Grant No. 2017JM8054).

Abbreviations

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- AChe

acetylcholine

- ATP

adenosine-triphosphate

- APTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- ACAT

O-acyltransferase

- ALR2

aldose reductase

- APD50

action potential duration at 50% repolarization

- APD90

action potential duration at 90% repolarization

- BuChe

butyrocholinesterase

- BDNF

brain derived neurotrophic factor

- CC50

half cytotoxicity concentration

- COX-2

prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2

- C.krusei

Candida krusei

- CNS

central nervous system

- c-Met

tyrosine-protein kinase Met

- DCC

Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- DADs

delayedafterdepolarizations

- DPPH

1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazylradical2,2-Diphenyl-1-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)hydrazyl

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- EADs

early afterdepolarizations

- EDCI

1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide

- EC50

half effective concentration

- EP4

prostaglandin E2 receptor 4

- GSH

glutathione

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- HMGB1

high mobility group box-1 protein

- HSP70

heat shock protein 70

- HDACi

histone deacetylase inhibitor

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBeAg

hepatitis Be Antigen

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- ICAM-1

intercellularcelladhesionmolecule-1

- IC50

half maximal inhibitory concentration

- iNOS

inductive nitric oxide synthase

- IL-6

interleukin- 6

- Ito

transient outward potassium current

- IK,SS

steady-state potassium current

- i p

intraperitoneal injection

- JAK

janus kinase

- Km

substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vmax

- Kcat

limiting rate of any enzyme-catalyzed reaction at saturation

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MAO

monoamine oxidase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MDR

multi-drug resistant

- MetAP2

human methionine aminopeptidase-2

- NF-κB

nuclear transcription factor-κB

- NO

nitric oxide

- Nrf2

nuclear factor 2

- OGD

oxygen–glucose deprivation

- P. falciparum

Plasmodium falciparum

- PAF

platelet-activating factor

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PT

prothrombin time

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein 1

- P. tenuifolia

Polygala tenuifolia Willd. (Polygalaceae)

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- SARS

severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SARS-CoV

SARS coronavirus

- SI

selective index

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TCM

traditional Chinese medicine

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor

- TT

thrombin time

- TMCA

3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl) acrylic acid

- TAs

triggered activities

References

- 1.Duarte F.S., Marder M., Hoeller A.A., Duzzioni M., Mendes B.G., Pizzolatti M.G., De Lima T.C.M. Anticonvulsant and anxiolytic-like effects of compounds isolated from Polygala sabulosa (Polygalaceae) in rodents: in vitro and in vivo interactions with benzodiazepine binding sites. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197:351–360. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein L.C., Jr., de Andrade S.F., Cechinel Filho V. A pharmacognostic approach to the Polygala genus: phytochemical and pharmacological aspects. Chem. Biodivers. 2012;9:181–209. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201000319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee C.I., Han J.Y., Hong J.T., Oh K.W. 3,4,5-Trimethoxycinnamic acid (TMCA), one of the constituents of Polygalae Radix enhances pentobarbital-induced sleeping behaviors via GABAAergic systems in mice. Arch Pharm. Res. (Seoul) 2013;36:1244–1251. doi: 10.1007/s12272-013-0167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C.Y., Wei X.D., Chen C.R. 3,4,5-Trimethoxycinnamic acid, one of the constituents of Polygalae Radix exerts anti-seizure effects by modulating GABAAergic systems in mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016;131:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2015.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung J.C., Min D., Kim H., Jang S., Lee Y., Park W.K., Khan I.A., Moon H.I., Jung M., Oh S. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl acrylamides as antinarcotic agents. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2010;25:38–43. doi: 10.3109/14756360902932784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao V.R., Muthenna P., Shankaraiah G., Akileshwari C., Babu K.H., Suresh G., Babu K.S., Kumar R.S.C., Prasad K.R., Yadav P.A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new piplartine analogues as potent aldose reductase inhibitors (ARIs) Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;57:344–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Y., Min X., Zhuang C., Li J., Yu Z., Dong G., Yao J., Wang S., Liu Y., Wu S. Design, synthesis and biological activity of piperlongumine derivatives as selective anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;82:545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao Y., Niu X., Chen B., Edwards H., Xu L., Xie C., Lin H., Polin L., Taub J.W., Ge Y. Synthesis and antileukemic activities of piperlongumine and HDAC inhibitor hybrids against acute myeloid leukemia cells. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohishi K., Aiyama R., Hatano H., Yoshida Y., Wada Y., Yokoi W., Sawada H., Watanabe T., Yokokura T. Structure-activity relationships of N-(3,5-dimethoxy-4-n-octyloxycinnamoyl)-N'-(3,4-dimethylphenyl)piperazine and analogues as inhibitors of acyl-CoA: cholesterol O-acyltransferase. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001;49:830–839. doi: 10.1248/cpb.49.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherukupalli S., Karpoormath R., Chandrasekaran B., Hampannavar G.A., Thapliyal N., Palakollu V.N. An insight on synthetic and medicinal aspects of pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine scaffold. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;126:298–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rai A., Singh A.K., Raj V., Saha S. 1,4-Benzothiazines-a biologically attractive scaffold. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2018;18:42–57. doi: 10.2174/1389557517666170529075556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao X., Zheng X., Fan T., Li Z., Zhang Y., Zheng J. A novel drug discovery strategy inspired by traditional medicine philosophies. Science. 2015;347:S38–S40. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Z., He X., Ma C., Wu S., Cuan Y., Sun Y., Bai Y., Huang L., Chen X., Gao T., Zheng X. Excavating anticonvulsant compounds from prescriptions of traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of epilepsy. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2018:1–31. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X18500374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai Y., Zhang Q., Jia P., Yang L., Sun Y., Nan Y., Wang S., Meng X., Wu Y., Qin F., Sun Z., Gao X., Liu P., Luo K., Zhan Y., Zhao X., Xiao C., Liao S., Liu J., Wang C., Fang J., Wang X., Wang J., Gao R., An X., Zhang X., Zheng X. Improved process for pilot-scale synthesis of Danshensu ((+/-)-DSS) and its enantiomer derivatives. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014;18:1667–1673. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu P., Hong F., Wang J., Wang J., Zhao X., Wang S., Xue T., Xu J., Zheng X., Zhai Y. DBZ is a putative PPARgamma agonist that prevents high fat diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance and gut dysbiosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2017;1861:2690–2701. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun Y., Bai Y., He X., Bai Y., Liu P., Zhao Z., Chen X., Zheng X. Design, synthesis and evaluation of novel 2-Hydroxypyrrolobenzodiazepine-5,11-dione analogues as potent angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Molecules. 2017:22. doi: 10.3390/molecules22111739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He X., Bai Y., Zeng M., Zhao Z., Zhang Q., Xu N., Qin F., Wei X., Zhao M., Wu N., Li Z., Zhang Y., Fan T.P., Zheng X. Anticonvulsant activities of alpha-asaronol ((E)-3'-hydroxyasarone), an active constituent derived from alpha-asarone. Pharmacol. Rep. 2018;70:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng X.H. 2017. Preparation Method and Application of Alpha-Asaronol Esters. CN104529775A. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawashima K., Miyako D., Ishino Y., Makino T., Saito K., Kano Y. Anti-stress effects of 3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamic acid, an active constituent of roots of Polygala tenuifolia (Onji) Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004;27:1317–1319. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chin Y.W., Kinghorn A.D., Patil P.N. Evaluation of the cholinergic and adrenergic effects of two tropane alkaloids from Erythroxylum pervillei. Phytother Res. 2007;21:1002–1005. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fife R., Maclaurin J.C., Wright J.H. Rescinnamine in treatment of hypertension in hospital clinic and in general practice. Br. Med. J. 1960;2:1848–1850. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5216.1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.China Pharmacopoeia Commission . vol.2015. Chemical Industry Press; Beijing, China: 2015. pp. 156–157. (Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China Part I). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ling Y., Li Z., Chen M., Sun Z., Fan M., Huang C. Analysis and detection of the chemical constituents of Radix Polygalae and their metabolites in rats after oral administration by ultra high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectr. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2013;85:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Y., Liu M., Liu P., Guo D.H., Wei R.B., Rahman K. Possible mechanism of the antidepressant effect of 3,6'-disinapoyl sucrose from Polygala tenuifolia Willd. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011;63:869–874. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikeya Y., Takeda S., Tunakawa M., Karakida H., Toda K., Yamaguchi T., Aburada M. Cognitive improving and cerebral protective effects of acylated oligosaccharides in Polygala tenuifolia. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004;27:1081–1085. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu P., Hu Y., Guo D.H., Wang D.X., Tu H.H., Ma L., Xie T.T., Kong L.Y. Potential antidepressant properties of radix polygalae (yuan zhi) Phytomedicine. 2010;17:794–799. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong X.Z., Huang C.L., Yu B.Y., Hu Y., Mu L.H., Liu P. Effect of Tenuifoliside A isolated from Polygala tenuifolia on the ERK and PI3K pathways in C6 glioma cells. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:1178–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le B.V., Kim J.H., Ji S.L., Nguyet N.T.M., Yang S.Y., Jin Y.M., Kim Y.H. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitory activity of phenolic glycosides from Polygala tenuifolia and in silico approach. Med. Chem. Res. 2017:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Z., Fang M., Xiao D., Liu M., Fefelova N., Huang C., Zang W.J., Xie L.H. Potential antiarrhythmic effect of methyl 3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamate, a bioactive substance from roots of polygalae radix: suppression of triggered activities in rabbit myocytes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2013;36:238–244. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b12-00654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroon P.A., Faulds C.B., Brézillon C., Williamson G. Methyl phenylalkanoates as substrates to probe the active sites of esterases. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;248:245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chin Y.W., Jones W.P., Waybright T.J., Mccloud T.G., Rasoanaivo P., Cragg G.M., Cassady J.M., Kinghorn A.D. Tropane aromatic ester alkaloids from a large-scale re-collection of Erythroxylum pervillei stem bark obtained in Madagascar. J. Nat. Prod. 2006;69:414–417. doi: 10.1021/np050366v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu C.Y., Jan J.T., Ma S.H., Kuo C.J., Juan H.F., Cheng Y.S.E., Hsu H.H., Huang H.C., Wu D., Brik A. Small molecules targeting severe acute respiratory syndrome human coronavirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:10012–10017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403596101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearce H.L., Safa A.R., Bach N.J., Winter M.A., Cirtain M.C., Beck W.T. Essential features of the P-glycoprotein pharmacophore as defined by a series of reserpine analogs that modulate multidrug resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1989;86:5128–5132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prasad S., Tyagi A.K. Historical spice as a future drug: therapeutic potential of piperlongumine. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 2016;22:4151–4159. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160601103027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shagufta, Ahmad I. Recent insight into the biological activities of synthetic xanthone derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;116:267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Busnena B.A., Foudah A.I., Melancon T., Sayed K.A.E. Olive secoiridoids and semisynthetic bioisostere analogues for the control of metastatic breast cancer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:2117–2127. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan J., Wong I.L., Jiang T., Wang S.W., Liu T., Wen B.J., Chow L.M., Wan S.B. Synthesis of methylated quercetin derivatives and their reversal activities on P-gp- and BCRP-mediated multidrug resistance tumour cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;54:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neri A., Frosini M., Valoti M., Cacace M.G., Teodori E., Sgaragli G. N,N-bis(cyclohexanol)amine aryl esters inhibit P-glycoprotein as transport substrates. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;82:1822–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong I.L.K., Wang B.C., Yuan J., Duan L.X., Liu Z., Liu T., Li X.M., Hu X., Zhang X.Y., Jiang T. Potent and nontoxic chemosensitizer of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance in cancer: synthesis and evaluation of methylated epigallocatechin, gallocatechin, and dihydromyricetin derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:4529–4549. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu C.C., Deng T., Fan M.L., Lv W.B., Liu J.H., Yu B.Y. Synthesis and in vitro antitumor evaluation of dihydroartemisinin-cinnamic acid ester derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;107:192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nam N.H., Yong K., You Y.J., Hong D.H., Kim H.M., Ahn B.Z. Preliminary structure–antiangiogenic activity relationships of 4-senecioyloxymethyl-6,7-dimethoxycoumarin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:2345–2348. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00392-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei B.L., Teng C.H., Wang J.P., Won S.J., Lin C.N. Synthetic 2′,5′-dimethoxychalcones as G 2/M arrest-mediated apoptosis-inducing agents and inhibitors of nitric oxide production in rat macrophages. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007;42:660–668. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu L.H., Zou H.B., Gong J.X., Li H.B., Yang L.X., Cheng W., Zhou C.X., Bai H., Guéritte F., Zhao Y. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a natural ester sintenin and its synthetic analogues. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:342–348. doi: 10.1021/np0496441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han C.K., Ahn S.K., Choi N.S., Hong R.K., Moon S.K., Chun H.S., Lee S.J., Kim J.W., Hong C.I., Kim D. Design and synthesis of highly potent fumagillin analogues from homology modeling for a human MetAP-2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00577-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fardis M., Pyun H.J., Tario J., Jin H., Kim C.U., Ruckman J., Lin Y., Green L., Hicke B. Design, synthesis and evaluation of a series of novel fumagillin analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003;11:5051. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar J.U., Shankaraiah G., Kumar R.S., Pitke V.V., Rao G.T., Poornima B., Babu K.S., Sreedhar A.S. Synthesis, anticancer, and antibacterial activities of piplartine derivatives on cell cycle regulation and growth inhibition. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2013;15:658–669. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2013.769965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santos C.C.F., Paradela L.S., Novaes L.F.T., Dias S.M.G., Pastre J.C. Design and synthesis of cenocladamide analogues and their evaluation against breast cancer cell lines. Medchemcomm. 2017;8:83–95. doi: 10.1039/c6md00577b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng Y.Q., Cao R.Y., Yang J.L., Li X.Z., Li S., Zhong W. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel HSP70 inhibitors: N, N′-disubstituted thiourea derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;119:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leslie B.J., Holaday C.R., Nguyen T., Hergenrother P.J. Phenylcinnamides as novel antimitotic agents. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:3964–3972. doi: 10.1021/jm901805m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamal A., Bajee S., Nayak V.L., Rao A.V.S., Nagaraju B., Reddy C.R., Sopanrao K.J., Alarifi A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of arylcinnamide linked combretastatin-A4 hybrids as tubulin polymerization inhibitors and apoptosis inducing agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:2957–2964. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang N., Zhang Z., Wong I.L.K., Wan S., Chow L.M.C., Jiang T. 4,5-Di-substituted benzyl-imidazole-2-substituted amines as the structure template for the design and synthesis of reversal agents against P-gp-mediated multidrug resistance breast cancer cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;83:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sendzik M., Janc J.W., Cabuslay R., Honigberg L., Mackman R.L., Magill C., Squires N., Waldeck N. Design and synthesis of beta-amino-alpha-hydroxy amide derivatives as inhibitors of MetAP2 and HUVEC growth. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:3181–3184. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu S., Li Y., Wei W., Wei J. Synthesis and biological evaluation of phenylpropanoid derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2016;25:1074–1086. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang L.J., Geng C.A., Ma Y.B., Luo J., Huang X.Y., Chen H., Zhou N.J., Zhang X.M., Chen J.J. Design, synthesis, and molecular hybrids of caudatin and cinnamic acids as novel anti-hepatitis B virus agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;54:352–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen H., Ma Y.B., Huang X.Y., Geng C.A., Zhao Y., Wang L.J., Guo R.H., Liang W.J., Zhang X.M., Chen J.J. Synthesis, structure-activity relationships and biological evaluation of dehydroandrographolide and andrographolide derivatives as novel anti-hepatitis B virus agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:2353–2359. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao Y., Geng C.A., Chen H., Ma Y.B., Huang X.Y., Cao T.W., He K., Wang H., Zhang X.M., Chen J.J. Isolation, synthesis and anti-hepatitis B virus evaluation of p-hydroxyacetophenone derivatives from Artemisia capillaris. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:1509–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Konno H., Onuma T., Nitanai I., Wakabayashi M., Yano S., Teruya K., Akaji K. Synthesis and evaluation of phenylisoserine derivatives for the SARS-CoV 3CL protease inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;27:2746–2751. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Konno H., Wakabayashi M., Takanuma D., Saito Y., Akaji K. Design and synthesis of a series of serine derivatives as small molecule inhibitors of the SARS coronavirus 3CL protease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;24:1241–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qurat-Ul-Ain S., Wang W., Yang M., Du N., Wan S., Zhang L., Jiang T. Anomeric selectivity and influenza A virus inhibition study on methoxylated analogues of Pentagalloylglucose. Carbohydr. Res. 2014;402:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matias M., Silvestre S., Falcão A., Alves G. Recent highlights on molecular hybrids potentially useful in central nervous system disorders. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2017;17:486–517. doi: 10.2174/1389557517666161111110121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jung J.C., Moon S., Min D., Park W.K., Jung M., Oh S. Synthesis and evaluation of a series of 3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamic acid derivatives as potential antinarcotic agents. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2013;81:389–398. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang L.X., Zhang L.J., Huang K.X., Kun L.X., Hu L.H., Wang X.Y., Stockigt J., Zhao Y. Antioxidant and neuroprotective effects of synthesized sintenin derivatives. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2009;24:425–431. doi: 10.1080/14756360802188214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang C., Du Q.Y., Chen L.D., Wu W.H., Liao S.Y., Yu L.H., Liang X.T. Design, synthesis and evaluation of novel tacrine-multialkoxybenzene hybrids as multi-targeted compounds against Alzheimer's disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;116:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jiang J., Ganesh T., Du Y., Quan Y., Serrano G., Qui M., Speigel I., Rojas A., Lelutiu N., Dingledine R. Small molecule antagonist reveals seizure-induced mediation of neuronal injury by prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:3149–3154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120195109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peng S., Zhang B., Meng X., Yao J., Fang J. Synthesis of piperlongumine analogues and discovery of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) activators as potential neuroprotective agents. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:5242–5255. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao J., Bai Y., Zhang C., Zhang X., Zhang Y.X., Chen J., Xiong L., Shi M., Zhao G. Cinepazide maleate protects PC12 cells against oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced injury. Neurol. Sci. 2014;35:875–881. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1618-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jung J.C., Min D., Lim H., Moon S., Jung M., Oh S. A simple synthesis of trans -3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamamides and evaluation of their biologic activity. Med. Chem. Res. 2013;22:4615–4621. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ku S.K., Lee J.H., Y O., Lee W., Song G.Y., Bae J.S. Vascular barrier protective effects of 3-N- or 3-O-cinnamoyl carbazole derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:4304–4307. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Holla B.S., Mahalinga M., Karthikeyan M.S., Poojary B., Akberali P.M., Kumari N.S. Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of some substituted 1,2,3-triazoles. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2005;40:1173–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pereira G.A., Souza G.C., Santos L.S., Barata L.E., Meneses C.C., Krettli A.U., Danielribeiro C.T., Alves C.N. Synthesis, antimalarial activity in vitro and docking studies of novel neolignan derivatives. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2017;90:464–472. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aratikatla E.K., Valkute T.R., Puri S.K., Srivastava K., Bhattacharya A.K. Norepinephrine alkaloids as antiplasmodial agents: synthesis of syncarpamide and insight into the structure-activity relationships of its analogues as antiplasmodial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;138:1089–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dai Y., Harinantenaina L., Bowman J.D., Fonseca I.O.D., Brodie P.J., Goetz M., Cassera M.B., Kingston D.G.I. Isolation of antiplasmodial anthraquinones from Kniphofia ensifolia, and synthesis and structure-activity relationships of related compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fregnan A.M., Brancaglion G.A., Costa C.O.D.S., Moreira D.R.M., Soares M.B.P., Bezerra D.P., Silva N.C., Morais S.M.D.S., Oliver J.C. Synthesis of piplartine analogs and preliminary findings on structure–antimicrobial activity relationship. Med. Chem. Res. 2017;26:603–614. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carvalho S.A., Feitosa L.O., Soares M., Costa T.E., Henriques M.G., Salomão K., de Castro S.L., Kaiser M., Brun R., Wardell J.L. Design and synthesis of new (E)-cinnamic N-acylhydrazones as potent antitrypanosomal agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Biodiversity. 2012;54:512–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yan M., Ma X., Dong R., Li X., Zhao C., Guo Z., Shen Y., Liu F., Ma R., Ma S. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of 4″-O-(trans-β-arylacrylamido)carbamoyl azithromycin analogs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;103:506–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seo Y.H., Kim J.K., Jun J.G. Synthesis and biological evaluation of piperlongumine derivatives as potent anti-inflammatory agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:5727–5730. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kumar S., Singh B.K., Arya P., Malhotra S., Thimmulappa R., Prasad A.K., Van d.E.E., Olsen C.E., Depass A.L., Biswal S. Novel natural product-based cinnamates and their thio and thiono analogs as potent inhibitors of cell adhesion molecules on human endothelial cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:5498–5511. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sun L.D., Wang F., Dai F., Wang Y.H., Lin D., Zhou B. Development and mechanism investigation of a new piperlongumine derivative as a potent anti-inflammatory agent. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015;95:156–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Woo N.T., Jin S.Y., Cho D.J., Kim N.S., Bae E.H., Han D., Han B.H., Kang Y.H. Synthesis of substituted cinnamoyl-tyramine derivatives and their platelet anti-aggregatory activities. Arch Pharm. Res. (Seoul) 1997;20:80–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02974047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Park B.S., Son D.J., Choi W.S., Takeoka G.R., Han S.O., Kim T.W., Lee S.E. Antiplatelet activities of newly synthesized derivatives of piperlongumine. Phytother Res. 2008;22:1195–1199. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nong W., Zhao A., Wei J., Lin X., Wang L., Lin C. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a new series of cinnamic acid amide derivatives as potent haemostatic agents containing a 2-aminothiazole substructure. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;27:4506–4511. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kaneko K., Uchida K., Kobayashi T., Miura K., Tanokura K., Hoshino K., Kato I., Onoue M., Yokokura T. Sex-dependent toxicity of a novel acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase inhibitor, YIC-C8-434, in relation to sex-specific forms of cytochrome P450 in rats. Toxicol. Sci. 2001;64:259–268. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/64.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brown D.G., Bostrom J. Analysis of past and present synthetic methodologies on medicinal chemistry: where have all the new reactions gone? J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:4443–4458. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen Y., Wang X., Yan B. Effect of brusatol ester side-chains on its chemosensitizing and cytotoxic activities: a coupled issue of druggability with drug metabolism. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2018;33 S45-S45. [Google Scholar]