Abstract

An epidemic of chronic kidney disease of unknown origin has emerged in the last decade in Central America and has been named Mesoamerican nephropathy. This form of chronic kidney disease is present primarily in young male agricultural workers from communities along the Pacific coast, especially workers in the sugarcane fields. In general, these men have a history of manual labor under very hot conditions in agricultural fields. Clinically, they usually present with normal or mildly elevated systemic blood pressure, asymptomatic yet progressive reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate, low-grade non-nephrotic proteinuria, and often hyperuricemia and or hypokalemia. Diabetes is absent in this population. Kidney biopsies that have been performed show a chronic tubulointerstitial disease with associated secondary glomerulosclerosis and some signs of glomerular ischemia. The cause of the disease is unknown; this article discusses and analyzes some of the etiologic possibilities currently under consideration. It is relevant to highlight that recurrent dehydration is suggested in multiple studies, a condition that possibly could be exacerbated in some cases by other conditions, including the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. At present, Mesoamerican nephropathy is a medical enigma yet to be solved.

Index Words: Chronic kidney disease, Mesoamerica

Ricardo Correa-Rotter, MD, was an International Distinguished Medal recipient at the 2013 National Kidney Foundation Spring Clinical Meetings. The International Distinguished Medals are awarded to honor the achievement of individuals who have made significant contributions to the field of kidney disease and extended the goals of the National Kidney Foundation.

The emergence of a form of chronic kidney disease (CKD) with unidentified cause that is highly prevalent in young male agricultural workers in Central American nations has become a major health and epidemiologic challenge for the general community, health professionals, and authorities in the region. This review addresses the present status of the knowledge for different aspects of this regional health problem, now referred to as Mesoamerican nephropathy.

As Heraclitus said, “There is nothing permanent except change,” and medicine is no exception. There is continual change in the way we approach diseases, in our diagnostic capabilities, in our procedures and skills to provide therapeutic options, and of course, in the human diseases we confront. The emergence of new infectious and noninfectious diseases poses a permanent challenge to medical knowledge and health systems. Multiple case examples support this concept. During the past decade, several new infectious diseases have emerged: for example, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and its related coronavirus,1 the A H1/N1 human flu strand that was responsible for a 2009 pandemic,2 and the bird flu strain H7N9 that recently infected humans in China and caused more than 30 deaths.3 For some newly recognized diseases, there still is no effective prevention or treatment. In the field of noncommunicable diseases, new entities can emerge, some of them related to environmental conditions and others due to unknown causes, yet epidemiology and causality often are less well defined than is the case with infectious diseases.

Nephrology has not been the exception regarding the advent or identification of new clinical entities. During the second half of the last century, Balkan endemic nephropathy (also referred to as aristolochic acid nephropathy) emerged, a chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis that displayed a familial yet not inherited pattern of presentation and was identified among persons living in rural areas of the Danube River in Serbia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania, and Bosnia.4, 5, 6 Only after 50 years of epidemiologic and clinical studies was aristolochic acid, from the plant Aristolochia clematitis, which contaminated the wheat flour in the region, identified as a likely cause.5, 6 This same herbal toxin is the cause of Chinese herb nephropathy (also referred to as aristolochic acid nephropathy), first described in a cluster of cases in Belgium7 and later described in multiple regions of the world, in particular in Asia, in association with ingestion of aristolochic acid–contaminated food products, beverages, and herbal remedies.8, 9, 10, 11

Whenever there is the suspicion of the emergence of a new clinical entity, a systematic process of identification should be put in place, including epidemiologic, clinical, and pathophysiologic characterization of the disease. Such a scientific and systematic approach is critical to define causality, as demonstrated with the identification of aristolochic acid as the likely cause of Balkan endemic nephropathy.5

Although CKD is a health problem that is increasing worldwide, in most instances, its cause is linked to known chronic noncommunicable diseases: in particular, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and hypertension. The Mesoamerican region (geographically comprising Central America and Southeastern Mexico; Fig 1 ) is not an exception to this increase in CKD because as in other areas of the world, it is experiencing the demographic and epidemiologic transition observed in many developing nations. CKD linked to these chronic noncommunicable diseases is present in Mesoamerica as much as in most other parts of the world.13

Figure 1.

Geographic region known as Mesoamerica incudes Southeastern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama.

Image adapted from the CIA World Factbook map of Central America.12

Nevertheless, during at least the last 2 decades, several Central American nations have observed the emergence of and, in some cases, an epidemic increase in a different form of CKD. This form of CKD has been scarcely characterized, and only recently have a few scientific and epidemiologic reports appeared. The first formal mention of the possible presence of a new pathologic entity was published in 2002 by Trabanino et al,14 who reported that 67% of the population with advanced CKD in Rosales Hospital of El Salvador had a disease of unknown origin. Subsequently, Torres et al,15 Peraza et al,16 and several other investigators17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 have laid ground for the definition of a form of CKD for which the cause or causes remain unknown.24 This nephropathy has emerged in coastal regions of Nicaragua and El Salvador and to some extent Costa Rica20 and Guatemala.25 In all affected regions, it has a fairly consistent pattern (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Epidemiologic Studies in Nicaragua and El Salvador Examining Possible Risk Factors for Reduced Kidney Function

| Torres et al15 (2010) | Sanoff et al20 (2010) | O’Donnell et al18 (2010) | González-Quiroz22 (2011) | Laux et al17 (2012) | McClean et al23 (2012) Cross-sectional Survey | McClean et al23 (2012) Prospective Cohort | Peraza et al16 (2012) | Orantes et al19 (2011) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Characteristics | |||||||||

| Design | Community-based cross-sectional survey | Screening program & nested case-control analysis | Community-based cross-sectional survey & case-control | Community-based cross-sectional survey | Community-based cross-sectional survey | Occupational cross-sectional survey | Prospective cohort (over a harvest season) | Community-based cross-sectional survey | Community-based screening & cross-sectional survey |

| Country | Nicaragua | Nicaragua | Nicaragua | Nicaragua | Nicaragua | Nicaragua | Nicaragua | El Salvador | El Salvador |

| Setting altitude & type | 4 villages at <300 masl in León/Chinandega: mining-subsistence farming, banana-sugarcane, fishing, service; 1 village at 200-675 masl: Coffee | 9 municipalities in León/Chinandega, generally in lowlands, includes sugarcane areas | 1 agricultural municipality, Quezalguaque in León; 80% with residence <500 masl | 55 communities in Chichigalpa, lowlands <300 masl, mostly sugarcane | 1 coffee village at 1,000 masl | Workers in mining, construction, & ports in lowland León/Chinandega, never worked in sugarcane | 1 sugarcane company in lowland Chinandega with distinct job titles | 5 distinct communities, 2 at sea level: both sugarcane; 3 at ≥500 masl: sugarcane, coffee, service | 3 coastal agricultural communities in the mouth of Lempa River (Bajo Lempa), at sea level |

| Study population (age, sex) | All community members, age 20-60 y, N = 1,096 (479 M/617 F) | Screening program: volunteers, age ≥ 18 y, N = 997 (848 M/149 F); Case-control: 112 cases, 222 controls, women excluded | Cross-sectional survey: weighted random sample, age ≥ 18 y, 17% of households, N = 771 (298 M/473 F); Case control: 98 cases & 221 controls from same household | Weighted random sample, age 20-60 y, N = 704 (237 M/467 F) | All community members, age 20-60 y, N = 267 (120 M/167 F) | Miners, n = 51; construction workers, n = 60; port workers, n = 53; age 18-63 y, only 3 F | Age 18-63 y, N = 284 (254 M/30 F); cane cutters, n = 51; seed cutters, n = 26; irrigators, n = 50; (re)seeders, n = 28; agrochemical applicators, n = 26; drivers, n = 41; factory workers, n = 50 | All community members, age 20-60 y, N = 674 (256 M/408 F) | 375 families (88% of community members), age > 18 y, N = 775 (343 M/432 F) |

| Community or group prevalence (%) of eGFRMDRD < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Mining/subsistence farming: M 18.5/F 4.9; banana-sugarcane: M 17.1/F 4.0; fishing: M 10.5/F 2.2; service, M 0.0/F 0.0; coffee, M 7.5/F 0.0 | Volunteer population: M 14.0/F 3.4 | M 20.1/F 8.0 | M 28.3/F 2.4 | M 0.0/F 1.4 | Mining, 5.9; construction, 5.0; port work, 7.9 | All workers preharvest, 0.4 (requirement for hiring SCr ≤ 1.3 mg/dL); all workers at late harvest, 5.5; cane cutters, 5.9; seed cutters, 11.5; irrigators, 2.0; other categories, 0.0 | Sugarcane lowland, M 18.6/F 8.0; sugarcane highland, M 1.8/F 3.1; coffee, M 0.0/F 1.2; services, M 0.0/F 2.4 | M 16.9/F 4.1 |

| Urinary biomarkers of kidney function | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Increased NGAL & NAG associated with decr eGFR; IL-18 highest in miners but not associated with decr eGFR | At late harvest: NGAL, NAG, & IL-18 highest in cane/seed cutters; Incr NGAL & NAG associated with decr eGFR; increase of NGAL & IL-18 during harvest largest for cane cutters & NAG largest for cane & seed cutters | Not studied | Not studied |

| Associations of Selected Risk Factors With Decreased eGFRa | |||||||||

| Male sex | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NA (only 3 women) | NR | Yes | Yes |

| Hypertension | Yes: men | No | Yes | Yes (NS) | No | NR | NR | Yes: women | Yes |

| Diabetes | No | No | No | Yes: women | No | No | No | Yes: women | No |

| Residence at low altitude | All excess CKD at low altitude, but service village at sea level without excess CKD | NR | Yes | NA (all lowland) | NA (all lowland) | NA (all lowland) | NA (all lowland) | Yes | NA (all lowland) |

| Family history of CKD | NR | Yes | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| (Illegal) alcohol | No | Yes: illegal; no: legal | Yes: legal (NS); no: illegal | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| NSAIDs | Yes: women (NS) | NR | No | No | No | NR | NR | No | No |

| Metals | Not studied | Not studied | No: lead | Not studied | Not studied | Yes: high total arsenic; no: lead, cadmium, uranium | Not studied | Not studied | |

| Associations of Agricultural Risk Factors With Decreased eGFRa | |||||||||

| Any agricultural work | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | NA | Yes | Yes | No |

| Sugarcane | Yes | NR | No | Yes | NA | NA | Yes: fieldworkers, especially cane & seed cutters | Yes: lowland; no: highland | NR |

| Cotton | NR | No | No | No | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NR |

| Coffee | No | NA | NA | NA | No | NA | NA | No | NA |

| Subsistence farming | Yes | NR | NR | NR | NR | NA | NA | Unclear | NR |

| Other crops | Yes: banana | Yes: banana, corn, rice; No: beans, sesame seed, cattle | NR | No: banana | NR | NA | NA | No | NR |

| Other jobs with heat exposure | Yes: mining, artisanal work, construction | Yes: sugar mills | NR | Yes: construction | NR | Yes: mining, construction, port work | NA | Yes: construction, service jobs | NR |

| Pesticides/ agrochemicals | NR | Yes | Yes (NS) | No | No | NA | No | NR | No |

| Heavy exertion | NR | NR | No | NR | NR | NR | Yes | NR | NR |

| High water intake | NR | Yes | No | NR | NR | No | No | NR | NR |

| Major limitations | Cross-sectional; analyses limited to current occupation | Volunteer study with likely selection bias; omission of sugarcane in the analyses | Cross-sectional; in case-control component, controls were not randomly selected from study population; no stratification by sex, obscuring work-related associations | Cross-sectional; analyses limited to current occupation | Cross-sectional; only confirms low risk in a low-risk community | Cross-sectional; no recruitment data; no multivariate analyses presented | High loss to follow-up | Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional; no stratification by sex, obscuring work-related associations; omission of sugarcane in analyses |

Note: In the prospective cohort in the McClean et al study, the largest decrease in eGFR during harvest was among cane cutters and seed cutters. Conversion factor for SCr in mg/dL to μmol/L, ×88.4.

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; decr, decreased; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IL-18, interleukin 18, incr, increased; masl, meters above sea level; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation; NA, not applicable; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; NR, not reported; NS, not statistically significant. NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SCr, serum creatinine.

Yes = positive association observed; no = no association observed.

Three international workshops have been conducted in Central America since 2005, under the auspices of the Program on Work, Health and Environment in Central America (SALTRA),26, 27, 28 as well as the National Autonomous University of Mexico.27 Much of this review is based on the discussions and results of these workshops, especially the First International Research Workshop on the Mesoamerican Nephropathy, held in November 2012 in San José, Costa Rica.28, 29 The epidemiologists, clinicians, and public health professionals who participated in the workshops emphasized that this disease does not follow expected patterns of usual or commonly known kidney disease, such as kidney disease linked to diabetes or hypertension. Instead, they confirmed that based on the epidemiologic studies listed in Table 1, this type of CKD exhibits the following characteristics. First, the location is primarily in a specific geographic region, that is, the coastal Pacific region of Central America. Second, the kidney disease is unrelated to diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or other known causes of kidney disease. Third, there is a male predominance (3 or 4:1) and predominance in young individuals (aged 30-50 years). Fourth, there is excessive occurrence in individuals working under hot conditions in agricultural communities, that is, especially workers in sugarcane and former cotton fields in coastal communities.

At present, the cause of this form of CKD, which has been named Mesoamerican nephropathy, is unknown. Agents that have been proposed as risk factors include, among others, heavy metals, agrochemicals, excessive use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications as pain killers, or consumption of potentially contaminated alcohol. Moreover, given the extremely hot and humid weather of the affected areas and the extremely strenuous working conditions of the agricultural workers, other potential mechanisms of kidney injury have been proposed.24, 26, 27, 28, 29

In parallel with the epidemiologic characterization of this disease, its natural history and clinical behavior also have been described.26, 27, 30, 31 The disease usually manifests as a silent yet progressive and relentless increase in serum creatinine level and absence of or, if any, low-grade (protein excretion < 1 g/d) proteinuria as measured by dipstick, in the otherwise asymptomatic individual. Nephrotic proteinuria is not common, and the urinary sediment, although not systematically reported, often is devoid of blood or casts. Mild hyperuricemia is common, as is hypokalemia. At present, we are not aware of any other systematic laboratory abnormalities that have been identified and or any specific pattern found by renal ultrasound or other imaging techniques. Mesoamerican nephropathy tends to progress to end-stage renal disease at some point, though the time period is not yet defined. In some patients, it occurs a few years after the first evidence of an elevated serum creatinine level. Unfortunately, renal replacement therapy is extremely scarce in Central America, and as such, many individuals who progress to end-stage renal disease are not offered dialysis. Thus, Mesoamerican nephropathy is the most common cause of death of young men working in sugarcane plantations in the lowlands of the Nicaraguan Pacific coast.22, 26 Mesoamerican nephropathy also results in a high mortality rate in El Salvador,32 including in the sugarcane-producing Pacific coast, where access to renal replacement therapy also is limited.33

To date, only a few kidney biopsies of affected patients have been performed. The dominant histopathologic pattern is that of a tubulointerstitial disease, consistent with the clinical presentation.26, 27, 30, 31 However, Wijkström et al34 also noted the common finding of glomerular ischemia, often with a component of global glomerulosclerosis, in a small series describing 8 sugarcane workers.

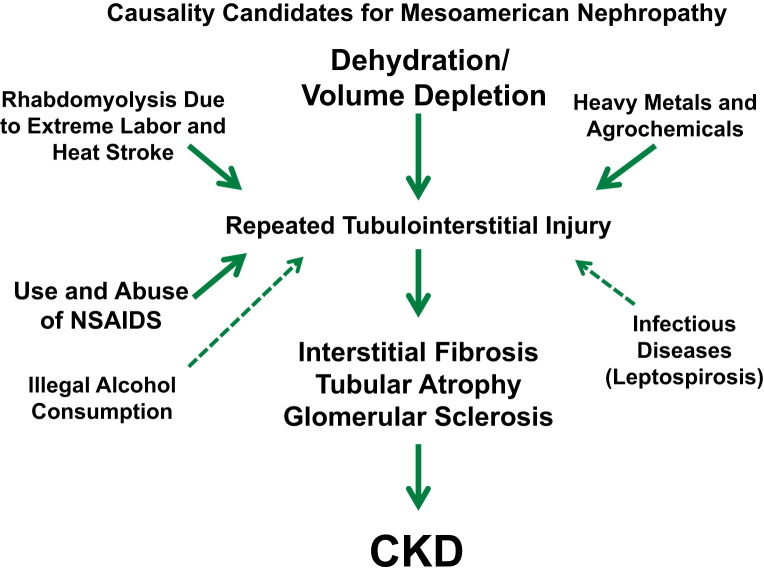

As happened with Balkan endemic nephropathy many years ago, now that a new form of CKD of unknown cause has been identified epidemiologically and clinically, there is an urgent need to understand its cause and how to prevent this disease from occurring. Multiple questions arise: are we facing a single cause or is this a mutlifactorial disease? Are we facing known or unknown factors that can cause kidney injury? To effectively advance our knowledge requires significant experimental and clinical research in several fields. The focus of the research will depend on which potential mechanisms are identified as relevant or potentially causative and which specific hypotheses are to be tested. In addition, the research may include a variety of approaches based on physiology, toxicology, epidemiology, and clinical intervention. In Table 2 , we summarize the pros and cons of selected etiologic agents that may be linked to the development of this clinical entity, as reviewed in the San José workshop.28 The conclusions presented in Table 2 on the whole coincide with the views of the workshop attendees, but in some cases, additional reflections and new information that has emerged after the workshop have been added and priority levels for research have been adjusted. The conclusions reflect current knowledge and likely will change in the future as results of new research become available. Also of note, there was consensus in the workshop that the cause of Mesoamerican nephropathy probably is multifactorial (Fig 2 ), with one or more of the factors discussed next interacting with each other.

Table 2.

Potential Causes of Mesoamerican Nephropathy

| Hypotheses | Pros | Cons | Comments | Conclusion | Priority for Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat stress, dehydration, and volume depletion | Heat exposure affects kidney function through volume depletion; exertion can produce rhabdomyolysis with consequent AKI35; individuals most frequently affected by MeN, ie, sugarcane workers, are exposed to extreme heat and strenuous work36; in El Salvador, sugarcane work in lowlands, but not in highlands, was associated with decreased kidney function16 | CKD has not been reported among sugarcane workers in other hot areas, such as in Brazil, Africa, and others | Subclinical injuries from repeated episodes of heat stress and dehydration may develop into CKD; ongoing experimental research in mice supports the hypothesis37 | Heat stress and dehydration are likely causes of MeN, in combination with other unknown factors | High priority |

| Hypokalemia and hyperuricemia | Prolonged hypokalemia can cause tubulointerstitial fibrosis38; hyperuricemia has experimentally been shown to cause glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis39 | Hypokalemia and hyperuricemia are not universally present in individuals presenting with MeN; hyperuricemia-associated kidney disease usually is associated with significant microvascular disease, which appears to be minimal in MeN | Both hyperuricemia and hypokalemia likely are a consequence of volume depletion and activation of the renin-angiotensin system | Hypokalemia and hyperuricemia are probably cofactors rather than primary causes | Low priority |

| Fructose/fructokinase | Recurrent dehydration in mice can induce CKD by the stimulation of aldose reductase with the production of fructose that causes tubular injury via fructokinase37; some sugarcane workers are also hydrating with drinks high in sugar | Animal studies do not always carry over to humans | Epidemiologic studies investigating the role of hydration with sugary solutions need to be performed | Activation of the fructokinase pathway may represent a potential mechanism for dehydration-associated CKD | High priority |

| Arsenic | Arsenic (inorganic) can cause AKI; low/moderate urinary levels of arsenic have been linked with albuminuria40; arsenic pollution occurs in regions of Central America with MeN: Guanacaste, Costa Rica,41 and Bajo Lempa, El Salvador42; highest 10th percentile of total urinary arsenic in sugarcane and mine workers was associated with a significant decrease in eGFR in Nicaragua23 | Arsenic is not a recognized cause of CKD; arsenic in drinking water has been documented in regions of Central America, but widespread high levels have not been demonstrated in the MeN-affected areas in Nicaragua or El Salvador43; urinary levels of Nicaraguan sugarcane and mining workers exceeded WHO tolerances in only 3%23 | Occupational exposure through contaminated pesticide formulations (as observed in Sri Lanka44) has not been evaluated in Mesoamerica | Arsenic is possibly a cofactor | Medium priority |

| Other heavy metals | In El Salvador cadmium has been detected in water sources in Nefrolempa42; lead and other heavy metals could be present in illegal alcohol20 | High cadmium, mercury, or lead levels are not reported in areas affected by MeN45; blood lead and urinary cadmium & uranium levels in Nicaragua sugarcane and mining workers were less than internationally recommended maximum and similar to levels in US population23; clinical presentation does not resemble renal effects from cadmium, lead, or mercury45 | Occupational exposure through cadmium-contaminated pesticide formulations (as observed in Sri Lanka44) has not been evaluated in Mesoamerica | Lead, cadmium, mercury, and uranium are unlikely causes of MeN | Low priority |

| Pesticides | CKD is more frequent in agricultural populations, who likely are exposed to pesticides; some widely used pesticides can cause AKI: paraquat, 2,4-D, glyphosate, and cypermethrin46; epidemiologic studies have found some evidence of an association between pesticides and CKD18, 20 | No pesticide has been identified as a cause of CKD in the literature we have examined; pesticides is a large heterogeneous group of agents with different toxicities; pesticide use differs greatly between regions and countries; it seems unlikely that thousands of CKD victims spread over multiple countries would be exposed to the same nephrotoxic pesticide | Pesticide contamination of water sources is a community concern; obsolete nephrotoxic insecticide toxaphene may still be present in soil in sugarcane areas where cotton or rice was produced, but this has not been evaluated; occupational exposure through contaminated pesticide formulations (as observed in Sri Lanka44) has not been evaluated in Mesoamerica | An etiologic role of pesticides in MeN is not likely but cannot be completely ruled out | Medium priority |

| Nephrotoxic medications | Use of NSAIDs is widespread15, 16; anecdotally, this is the case in particular among sugarcane workers exposed to physically demanding tasks; to a lesser extent, aminoglycoside antibiotics are used for dysuria treated as UTI47 | NSAIDs are rarely associated with CKD and AKI should be seen more frequently if NSAIDs were an important cause; aminoglycosides need prolonged treatment in order to cause CKD48 | NSAIDs and aminoglycosides may worsen kidney injury from other causes | The use of nephrotoxic medications is a possible cofactor in the MeN epidemic | High priority |

| Infectious diseases: leptospirosis | Leptospirosis can cause AKI in humans and CKD in other mammals49; leptospirosis is endemic in MeN regions, more common among male agricultural workers, including sugarcane workers49 | Leptospira is not an established cause of CKD | Key question: Could mild or subclinical leptospirosis lead to multiple episodes of acute interstitial nephritis, resulting in progressive kidney fibrosis and ultimately CKD?49 | Leptospirosis is possibly a cofactor | Medium priority |

| Urinary tract diseases | Heat stress could contribute to the development of kidney stones, which can damage the kidney and lead to CKD35 | Urine cultures among 50 male sugarcane workers with current symptoms of ‘chistate’ (dysuria) or white blood cells in their urine were uniformly negative23; nephrolithiasis is infrequent and does not explain the widespread epidemic of MeN | ‘Chistata’ (or chistate) is dysuria and, in Central America, it is often wrongly diagnosed as UTI; kidney stones and dysuria may have their origin in dehydration and heat stress; dysuria may be a symptom for microcrystals in hypersaturated urine35 | UTIs are not a cause of MeN; kidney stones could be associated with MeN in the context of heat stress and dehydration | Low priority for UTIs and medium priority for kidney stones |

| Aristolochic acid | Various Aristolochia spp grow in Mesoamerica | The histopathology in MeN differs from aristolochic nephropathy34; absence of urothelial cancers; widespread exposure is unlikely: sex difference in MeN argues against50 | Urothelial cancer has a long latency, could appear later or not at all if affected men die young; an increase may go undetected in countries without a cancer registry | Aristolochia is an unlikely cause, but cannot be completely ruled out at this moment | Low priority |

| Genetic susceptibility | High local rates of a relatively uncommon disease need a powerful risk factor; family clustering has been reported51 | — | No studies have been carried out; the main benefit of determining a genetic component from the etiologic perspective is if it helps elucidate the other cause(s) of MeN; virtually all diseases have some genetic component, but unless the genetic component is strong, it is unlikely to be useful | — | Medium priority |

| Low birth weight, prenatal, and childhood exposures | High prevalence of CKD at young age suggests initial damage may start during childhood; markers of tubular kidney damage, especially NAG, were highest among students aged 12-18 y in areas with highest occurrence of CKD52 | Levels of biomarkers were higher among women than men52 | A factor, so far unidentified, may act at early age and posterior occupational exposure among men may trigger the disease | Early child factors may possibly influence disease occurrence, yet seems not a very likely cause | Medium priority |

| Hard water | In Sri Lanka, hard water and CKD occurrence coincide; it has been hypothesized that hardness of water affects heavy metal toxicity at the cellular level53 | No known health effects from hard water | In the MeN-affected area of Guanacaste in Costa Rica, hard water is a serious community concern (Jennifer Crowe, personal communication) | Hard water is an unlikely cause | Low priority |

| (Illegal) alcohol use | One study found an association between CKD and intake of illegal alcohol in Nicaragua20 | Strong associations between alcohol and MeN have not been observed in other studies in the Mesoamerican region14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22 | — | Illegal alcohol is not a likely cause | Low priority |

| Silica dust | Silica has been associated with CKD54, 55; sugarcane, construction, and mining workers may be exposed to silica dust | Most cases of CKD associated with exposure to silica have been reported to condition glomerulonephritis and clinically have significant hypertension and proteinuria56 | Silica content in soils in MeN areas is unknown | Silica is a potential risk of unknown magnitude | Low priority |

| Social determinants | Extreme poverty forces young people to leave school early and begin working in sugarcane57; working conditions in sugarcane are extremely harsh: excessive working hours, few rest days, and physical exertion in extreme heat36, 57 | Social factors are prone to generalizations and oversimplification; social determinants do not explain the pathophysiology of the disease | Working conditions underlying physiopathology of MeN can be changed as preventative action | Poverty is a known determinant of CKD, although a distal cause; working conditions contribute to heat stress and dehydration | High priority |

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MeN, Mesoamerican nephropathy; NSAIDs, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs; UTI, urinary tract infection; WHO, World Health Organization.

Figure 2.

Possible causes for Mesoamerican nephropathy. Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Potential causes of Mesoamerican nephropathy

Aristolochic Acid and Mycotoxins

Potential candidate agents and areas for research to identify causality of Mesoamerican nephropathy include diverse types of environmental toxins, some of which occur naturally, such as aristolochic acid, which has been linked to Chinese herb nephropathy and Balkan endemic nephropathy, and mycotoxins, such as ochratoxin A, as described in Tunisia.50 Aristolochia is a plant that is common in Central America and its potential use in herbal remedies and even inadvertent contamination of food supplies could be a potential risk for nephropathy. Although these 2 agents have not been excluded in the causality of Mesoamerican nephropathy, present data do not suggest they are likely etiologic factors. In addition, aristolochic nephropathy is characterized by primary renal fibrosis with minimal inflammation50 and is not consistent with biopsy findings from the few cases that have been reported.34

Heavy Metals

Other environmental toxins that may be considered are heavy metals, such as cadmium, lead, mercury, or arsenic. However, to date, there is little evidence for involvement of heavy metal poisoning in the Mesoamerican region.45 While low concentrations of arsenic have been identified in a study in Western Nicaragua, the concentrations are unlikely to be sufficient to account for the epidemic of Mesoamerican nephropathy.23 Nevertheless, it could be a contributing risk factor, similar to what has been described in a recent epidemic of kidney disease in Sri Lanka.58

Agrochemicals

Other man-made environmental toxins of relevance are agrochemicals, such as pesticides or fertilizers. In support for this hypothesis, there is a geographical distribution of the disease affecting mainly rural-agricultural regions, especially those associated with sugarcane production. However, the association of Mesoamerican nephropathy with other activities (such as mining, construction, and port work),23 in which agrochemicals are not present, makes this hypothesis less likely. The difference in the number of men and women affected argues against environmental pathways of exposures, and if agrochemicals were etiologically involved, occupational exposure would be the most likely setting. Although pesticide exposure has been a major concern for workers, to date no specific agrochemical has been identified as a likely candidate for the epidemic.46 It is noteworthy that pesticides are a large heterogeneous group of hundreds of active ingredients with different chemical structures and toxicities and a diversity of uses. Pesticide use varies considerably between regions and countries and even within the same crops. It is hard to imagine that the thousands of individuals with CKD in multiple countries would have been occupationally exposed to a specific nephrotoxic pesticide, but this still cannot be ruled out. In addition, environmental exposures, for example, to the nephrotoxic organochlorine insecticide toxaphene, which was widely used in the past on rice and cotton throughout Central America, could be etiologically relevant if its toxicity interacts with another occupational exposure that predominantly affects men, such as exposure to heat and dehydration.

Leptospirosis and Other Infectious Causes

Some systemic infections such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) are well-known causes of glomerulopathies and secondary CKD, yet these known causes are not prevalent among the affected population with Mesoamerican nephropathy and therefore have not been identified as causal factors in the Mesoamerican region. However, some systemic infections may be associated with environmental exposures (reflecting bad hygiene conditions) and occupational hazards. It is well known that infectious diseases such as leptospirosis, hantavirus, and malaria may cause acute kidney injury. There is limited, if any, evidence that these agents also may cause CKD. In some Central American nations there is a high seroprevalence of leptospirosis, including in the Pacific coastal regions of Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Costa Rica. There also may be significant under-reporting of cases and the real frequency of the disease could be higher. It has been hypothesized that leptospirosis may act in conjunction with other potentially nephrotoxic conditions in the genesis of Mesoamerican nephropathy.49

Alcohol Drinks Containing Toxins

Another potential etiologic factor that has been studied in Nicaragua is the unregulated consumption of locally produced alcohol known as lija, which is a sugarcane-derived, distilled, and unfiltered product that is illegally produced and has caused major outbreaks of poisoning and hundreds of deaths in Chinandega and Leon in the past, mainly due to methanol contamination. A study published in 2010 described an association of ingesting this type of unregulated alcohol with CKD.20 The authors suggested that some “potential contamination” of this product could be involved, yet no specific component or causal agent was proposed. In the past, non–legally produced alcoholic products have been reported to cause gout or kidney disease due to contamination by lead, but there is little evidence that this occurs with lija. The observation that lija is not commonly drunk in El Salvador despite the presence of Mesoamerican nephropathy there16 also makes this possibility unlikely. Heavy consumption of unadulterated alcohol also can contribute to CKD by exacerbating dehydration, but to date, most studies do not support an association (see Table 1).

Nonsteroidal Agents and Other Nephrotoxic Drugs

A common practice among workers in areas where Mesoamerican nephropathy is prevalent is the use of self-prescribed drugs, especially nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs commonly are taken as pain killers after exhausting physical activity, and intake may be increased in individuals given a diagnosis of Mesoamerican nephropathy.47 Although NSAIDs can cause acute interstitial nephritis, the more likely way they might contribute to Mesoamerican nephropathy is through their hemodynamic effects, especially the reduction of renal blood flow. This effect might be especially important in individuals who are exposed to heat and not adequately hydrated. Hence, NSAIDS are likely contributory factors for the development of Mesoamerican nephropathy.

Recurrent Dehydration/Volume Depletion

One of the characteristic findings of individuals who develop Mesoamerican nephropathy is the common history of working in hot agricultural communities in which dehydration is common. Agricultural workers of the Pacific Coast lowlands of Central America, in particular sugarcane harvesters, work under severe heat stress conditions.36 Very significant differences between those working in the fields and local controls have been demonstrated in terms of hydration/dehydration practices and their consequences. Solís-Zepeda59 noted that sugarcane workers lost an average of 2.6 kg of body weight during the course of a day in the sugarcane fields, whereas workers participating in an educational hydration program did not lose weight. A study performed in Costa Rica by Crowe et al60 also found evidence for significant dehydration during work hours, as noted by urinary specific gravity >1.020 at the end of their shift, and significantly more heat stress and dehydration-related symptoms among cane cutters compared with noncutters in the same sugarcane company over the harvest period. A recently completed and as yet unpublished study in Nicaragua demonstrated increases in serum creatinine levels at the end of daily working shifts among cane cutters (Aurora Aragón, personal communication).

Although volume depletion usually is thought of as causing a prerenal pattern of acute kidney injury, experimental studies in mice have suggested that recurrent dehydration may lead to chronic tubular injury with fibrosis.37 The mechanism appears to be mediated by an increase in serum osmolarity, which stimulates an increase in the polyol (aldose reductase) pathway in the kidney. This leads to some conversion of glucose in the proximal tubule to sorbitol and fructose, which then is metabolized by fructokinase to generate oxidants that cause local tubular injury. Volume depletion also may cause renal injury by other mechanisms, including decreased renal perfusion (causing tubular injury).37 In addition, repeated dehydration and exhausting physical work may be accompanied by other mechanisms of tissue injury, such as rhabdomyolysis. All these conditions often are accompanied by the intake of NSAIDs as stimulants and pain relievers, further jeopardizing appropriate renal medullary blood flow in particular and whole kidney perfusion in general. These various contributory factors may favor discrete yet repeated episodes of acute kidney injury, which in turn could be responsible for the CKD seen in the long term in this population. Further studies are needed to test this and other hypotheses. If long-term recurrent dehydration or volume depletion is a cause of CKD, it also may play a role in CKD in other countries such as Sri Lanka, where epidemics of kidney disease are being reported.61 If this hypothesis is true, Mesoamerican nephropathy may represent a disease of or exacerbated by global warming.

Fructose

The observation that recurrent dehydration can induce CKD in mice by the polyol-fructokinase pathway37 suggests that excessive intake of fructose-containing drinks also may exacerbate the kidney injury. It is known that some individuals are hydrating themselves with drinks that are high in sugar content (such as soft drinks). In turn, this can lead to an increase in urinary fructose62 that then could be taken up by the proximal tubule, where it would be metabolized by fructokinase. Although it has been shown that diets high in fructose can cause tubulointerstitial injury and CKD in rats,63, 64 whether this process is occurring in Mesoamerican nephropathy has not been determined.

Hypokalemia and Hyperuricemia

Metabolic factors also may be important in the disease etiology. Many affected individuals have been found to have mild to moderate hypokalemia and hyperuricemia, both of which are likely a response to dehydration with activation of the renin-angiotensin system.31, 34 Chronic hypokalemia can induce tubulointerstitial disease that consists of tubular cell hyperplasia and an ischemic-type of fibrosis.65 Chronic hyperuricemia also has been proposed to play a role in CKD, although classically the kidney lesions have significant microvascular disease.66 It remains possible that these metabolic abnormalities may be contributing factors in this disease.

Social Determinants

In the web of causation, biological causes and physiopathologic pathways are immersed in social determinants. Mesoamerican nephropathy is an occupational disease,57 primarily affecting sugarcane workers16, 22, 26, 27, 28 and especially cane cutters,23 who perform the most strenuous tasks in the hottest environmental conditions.23, 36 Although workers in other hot occupations also may be at risk, such as miners, construction workers, and port workers,15, 16, 22, 23 it is work in sugarcane fields that stands out in affected communities.15, 16, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 33, 35, 36, 56, 57, 60 Epidemiologic studies that did not specifically report or did not observe a relation of CKD with sugarcane work either did not differentiate among types of agricultural workers,15, 19, 20 were conducted in a high-altitude low-risk area,17 or did not present sex-specific associations,18, 19 which made it more difficult to interpret occupational risk factors. Working conditions in sugarcane fields are extremely harsh: excessive working hours, few rest days, and physical exertion in extreme heat.36, 57, 60

Prevention and treatment

Treatment resources for end-stage renal disease in most of Central America are scarce. There is minimal availability of health insurance, and dialysis and transplantation programs are not widely available due to major financial constraints and lack of doctors and clinical staff. At present, a large number of individuals with this form of CKD of unknown origin will die untreated of end-stage renal disease. Thus, there is an urgent need to find the cause, and for early prevention and treatment.

At present, the best known prevention is to provide adequate hydration and limit exposure of workers to heat. Working in the early morning hours before the temperature gets excessive may be of benefit. However, this is not an easy recommendation for all heat-exposed workers. Sugarcane cutters in Costa Rica and Nicaragua start their workday at dawn.22, 36 In Costa Rica, sugarcane cutters work over the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)-recommended limits of heat stress often by as early as 9:15 am.36 Increased drinking of water is recommended to minimize the effects of excessive sweating, and avoidance of NSAIDs is highly recommended. Providing appropriate sources of hydration and sanitation and allowing for reasonable working shifts accompanied by periods of rest and provision of shade are all recommended strategies for prevention. Such interventions should be adequately studied for effectiveness by means of field trials. In addition, even if pesticides eventually are found not to cause CKD, there is no doubt that any potential hazards associated with their use should be minimized, and sustainable nontoxic pest control methods should be favored. Other factors that have been discussed, including limiting alcohol consumption, are an equal matter of concern that in any case should be modified and reduced to improve the general health of this population.

In the context of prevention and treatment strategies, the socioeconomic circumstances underlying the explosion of this epidemic must be addressed. The World Bank’s Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) final media statement,67 issued in 2012 after the completion of a series of important studies carried out in the Mesoamerican nephropathy hotspot in Nicaragua, Chichigalpa, emphasized that this disease extends to other regions and industries that involve strenuous work conditions in hot environments.67 In addition, CAO places the responsibility of addressing the socioeconomic issues that may predispose individuals to diseases such as Mesoamerican nephropathy with national and regional institutions. Early in 2013, the International Finance Corporation loaned $15 million to another Nicaraguan sugarcane company to increase development, yet working conditions remain as they have been and no intervention or research has been commissioned.68

Conclusion

In summary, it was not until relatively recently that a devastating epidemic of CKD among agricultural workers living in rural Nicaragua and other Central American countries, including El Salvador and Costa Rica, was described. This type of CKD is not due to diabetes, hypertension, or obesity. Although a variety of causes have been considered, to date there is no conclusive evidence of any specific risk factor being the cause of this epidemic. However, a likely candidate is recurrent dehydration related to occupational exposure to heat, likely exacerbated by NSAIDs or other toxins. The occupational heat exposure leading to Mesoamerican nephropathy to date has been most evident among sugarcane workers, whose social and labor conditions are part of the cause of Mesoamerican nephropathy and should be considered by policy makers and development agencies. Further studies are indicated to identify the physiologic cause, in the context of their social determinants.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the valuable contributions of the participants of the First International Research Workshop on Mesoamerican Nephropathy, held November 30, 2012 in San José, Costa Rica, to increase understanding of Mesoamerican nephropathy. In particular we are grateful to the authors of the state-of-the-art papers published in the workshop report, many of which are referenced in this review.

Support: None.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

References

- 1.Drosten C., Günther S., Preiser W. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez-Padilla R., de la Rosa-Zamboni D., Ponce de Leon S., for the INER Working Group on Influenza Pneumonia and respiratory failure from swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(7):680–989. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu D., Shi W., Shi Y. Origin and diversity of novel avian influenza A H7N9 viruses causing human infection: phylogenetic, structural, and coalescent analyses. Lancet. 2013;381(9881):1926–1932. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60938-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hranjec T., Kovac A., Kos J. Endemic nephropathy: the case for chronic poisoning by Aristolochia. Croat Med J. 2005;46(1):116–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grollman A.P., Shibutani S., Moriya M. Aristolochic acid and the etiology of endemic (Balkan) nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(29):12129–12134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701248104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grollman A.P., Jelaković B. Role of environmental toxins in endemic (Balkan) nephropathy. October 2006, Zagreb, Croatia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(11):2817–2823. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007050537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vanherweghem J.L. [A new form of nephropathy secondary to the absorption of Chinese herbs] Bull Mem Acad R Med Belg. 1994;149(1-2):128–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lord G.M., Tagore R., Cook T., Gower P., Pusey C.D. Nephropathy caused by Chinese herbs in the UK. Lancet. 1999;354(9177):481–482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez M.C., Nortier J., Vereerstraeten P., Vanherweghem J.L. Progression rate of Chinese herb nephropathy: impact of Aristolochia fangchi ingested dose. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17(3):408–412. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai M.Y., Yang W.C. Herb-associated carcinogenicity and chronic renal failure in Asian patients with kidney cancer and hypertension. Kidney Int. 2005;68(1):412. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.413_7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debelle F.D., Vanherweghem J.L., Nortier J.L. Aristolochic acid nephropathy: a worldwide problem. Kidney Int. 2008;74(2):158–169. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Central Intelligence Agency. CIA World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook. Accessed October 31, 2013.

- 13.Cusumano A., Garcia Garcia G., Gonzalez Bedat C. The Latin American Dialysis and Transplant Registry: report 2006. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(1 suppl 1) S1-3-S1-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trabanino R.G., Aguilar R., Silva C.R., Mercado M.O., Merino R.L. [End-stage renal disease among patients in a referral hospital in El Salvador] Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2002;12(3):202–206. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892002000900009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torres C., Aragón A., González M. Decreased kidney function of unknown cause in Nicaragua: a community-based survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3):485–496. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peraza S., Wesseling C., Aragón A. Decreased kidney function among agricultural workers in El Salvador. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(4):531–540. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laux T.S., Bert P.J., Barreto Ruiz G.M. Nicaragua revisited: evidence of lower prevalence of chronic kidney disease in a high-altitude, coffee-growing village. J Nephrol. 2012;25(4):533–540. doi: 10.5301/jn.5000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Donnell J.K., Tobey M., Weiner D.E. Prevalence of and risk factors for chronic kidney disease in rural Nicaragua. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(9):2798–2805. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orantes C.M., Herrera R., Almaguer M. Chronic kidney disease and associated risk factors in the Bajo Lempa region of El Salvador: Nefrolempa study, 2009. MEDICC Rev. 2011;13(4):14–22. doi: 10.37757/MR2011V13.N4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanoff S.L., Callejas L., Alonso C.D. Positive association of renal insufficiency with agriculture employment and unregulated alcohol consumption in Nicaragua. Ren Fail. 2010;32(7):766–777. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.494333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerdas M. Chronic kidney disease in Costa Rica. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;97:S31–S33. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.González-Quiroz M.A. CISTA-UNAN-León; Nicaragua: 2010. Enfermedad Renal Crónica: prevalencia y factores de riesgo ocupacionales en la Municipalidad de Chichigalpa. [Master en Ciencias con mención en salud ocupacional thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClean M, Amador JJ, Laws R, et al. Biological sampling report: investigating biomarkers of kidney injury and chronic kidney disease among workers in Western Nicaragua. Boston University School of Public Health. 2012. http://www.cao-ombudsman.org/cases/document-links/documents/Biological_Sampling_Report_April_2012.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2013.

- 24.Weiner D.E., McClean M.D., Kaufman J.S., Brooks D.R. The Central American epidemic of CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(3):504–511. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05050512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ministry of Health of Guatemala. Data presented at COMISCA meeting, April 2013, El Salvador. http://www.paho.org/els/index.php?option5com_content&task5view&id5778. Accessed November 10, 2013.

- 26.Cuadra SN, Jakobsson K, Hogstedt C, Wesseling C. Chronic kidney disease: assessment of current knowledge and feasibility for regional research collaboration in Central America. In: Chronic Kidney Disease: Assessment of Current Knowledge and Feasibility for Regional Research Collaboration in Central America. Work & Health Series, No. 2. Heredia, Costa Rica: SALTRA, IRET-UNA; 2006. http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-2. Accessed October 6, 2013.

- 27.Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Programa Salud y Trabajo en América Central (SALTRA). Memoria del taller “Formación de un equipo interdisciplinario para la investigación de la enfermedad renal crónica en las regiones cañeras de Mesoamérica”, 13–14 de noviembre 2009, Heredia, Costa Rica. http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/descarga-memoria-taller-erc-nov-09. Accessed October 6, 2013.

- 28.Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wesseling C, Crowe J, Hogstedt C, Jakobsson K, Lucas R, Wegman D. Resolving the enigma of the Mesoamerican nephropathy – MeN - A research workshop summary [published online ahead of print October 17, 2013]. Am J Kidney Dis. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Flores Reyna R., Jenkins Molieri J.J., Vega Manzano R. Salud para un país de future [Health for a Country of the Future] PAHO; 2004. Enfermedad renal terminal: hallazgos preliminares de un reciente estudio en el Salvador [End stage renal disease: preliminary findings of a recent study in El Salvador] pp. 222–230. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trujillo L., Cruz Z., Leiva R., Lazo S., Cruz V. Clinical characteristics and 3 year follow-up of patient with chronic kidney disease who live in Santa Clara sugarcane cooperative department of La Paz, El Salvador. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 209–210.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.DIGESTYC. Indicadores demográficos. Ministry of Economy of El Salvador, 2013. http://www.digestyc.gob.sv/index.php/servicios/descarga-de-documentos/category/47-presentaciones-estadisticas-sociales.html. Accessed March 12, 2013.

- 33.Leiva R. The health system and CKD in El Salvador. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 219–220.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wijkström J., Leiva R., Elinder C.G. Clinical and pathological characterization of Mesoamerican nephropathy: a new kidney disease in Central America. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(5):908–918. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks D. Hypothesis summary: heat exposure. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 103–108.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crowe J., Wesseling C., Román Solano B. Heat exposure in sugarcane harvesters in Costa Rica. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56(10):1157–1164. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roncal Jimenez CA, Ishimoto T, Lanaspa MA, et al. Dehydration-induced renal injury: a fructokinase mediated disease? [published online ahead of print December 11, 2013]. Kidney Int. 10.1038/ki.2013.492. [DOI]

- 38.Wang H.H., Hung C.C., Hwang D.Y. Hypokalemia, its contributing factors and renal outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakagawa T., Cirillo P., Sato W. The conundrum of hyperuricemia, metabolic syndrome, and renal disease. Intern Emerg Med. 2008;3(4):313–318. doi: 10.1007/s11739-008-0141-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng L.Y., Umans J.G., Tellez-Plaza M. Urine arsenic and prevalent albuminuria: evidence from a population-based study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(3):385–394. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mora-Alvarado D. Informe: acciones correctivas para disminuir las concentraciones de arsénico en el acueducto de la comunidad de Cañas [Report: corrective actions to decrease arsenic concentrations in the aqueduct of the Cañas community]. Laboratorio Nacional de Aguas, Instituto Costarricense de Acueductos y Alcantarillados (AyA), 2011. https://www.aya.go.cr/Administracion/DocumentosBoletines/Docs/050411021758nformeaccionescorrectivasparadisminuirlasconcentracionesdearsenicoenelacueductodelacomunidaddeCanas.pdf. Accessed July 24, 2013.

- 42.Larios D, Ribó A, Quinteros E, et al. Investigación ambiental en áreas con alta prevalencia de la Enfermedad Renal Crónica de causa no tradicional: Bajo Lempa [Environmental research in areas with high prevalence of chronic kidney disease of non traditional cause: Nephro Lempa]. Data presented at COMISCA meeting, San Salvador, April 24, 2013. http://www.paho.org/els/index.php?option%20=com_content&view=article&id=778. Accessed October 6, 2013.

- 43.Law R., Amador J.J. Hypothesis summary: arsenic. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 95–98.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jauasumana MACS, Paranagama PA, Amarasinge M, Fonseka SJ, Wijekoon DV. Presence of arsenic in pesticides used in Sri Lanka. In: Proceedings of the Water Professional's Day. Symposium, Water Resources Research in Sri Lanka, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Peradenyia; 2011:127-141. http://www.lankaweb.com/news/items/2011/10/03/presence-of-arsenic-in-pesticides-used-in-sri-lanka/. Accessed July 24, 2013.

- 45.Elinder C.G. Renal effects from exposure to lead, cadmium and mercury. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 67–74.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McClean MD, Laws R, Ramirez Rubio O, Brooks D. Industrial hygiene/occupational health assessment: evaluating potential hazards associated with chemicals and work practices at the Ingenio San Antonio (Chichigalpa, Nicaragua). 2010. http://www.cao-ombudsman.org/cases/document-links/documents/FINALIHReport-AUG302010-ENGLISH.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2013.

- 47.Ramírez-Rubio O., Brooks D.R., Amador J.J., Kaufman J.S., Weiner D.E., Scammell M.K. Chronic kidney disease in Nicaragua: a qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews with physicians and pharmacists. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:350. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaufman J., Elinder C.G. Drug-induced nephrotoxicity in the Central American CKD epidemic. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 99–102.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riefkohl A. Possible association between Leptospira infection and chronic kidney disease of unknown origin in Central America. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 81–85.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elinder C.G., Jakobsson K. Balkan nephropathy, Chinese herbs nephropathy, aristolochic acid nephropathy and nephrotoxicity from mycotoxins. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 87–90.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friedman D., Brooks D. Genetic susceptibility to kidney disease in Mesoamerica: a developing hypothesis. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 119–221.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramírez-Rubio O., Amador J.J., Kaufman J.S. Kidney damage markers in Nicaraguan adolescents in a region of an epidemic of CKD of unknown etiology. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 201–202.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jayasumana M.A.C.S., Paranagama P.A., Amarasinghe M.D., Fonseka S.I. Is hard water an etiological factor for CKDu? In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 91–94.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steenland K., Rosenman K., Socie E., Valiante D. Silicosis and end-stage renal disease. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2002;28(6):439–442. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vupputuri S., Parks C.G., Nylander-French L.A., Owen-Smith A., Hogan S.L., Sandler D.P. Occupational silica exposure and chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2012;34(1):40–46. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2011.623496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Osorio A.M., Thun M.J., Novak R.F., Van Cura E.J., Avner E.D. Silica and glomerulonephritis: case report and review of the literature. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;9(3):224–230. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(87)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiss I., Hutchinson Y. Experiences of La Isla Foundation. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 123–127.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jakobsson K, Jayasumana Ch. Chronic kidney disease of unknown origin in Sri Lanka. In: Wesseling C, Crowe J, Hogstedt C, Jakobsson K, Lucas R, Wegman D, eds. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. Heredia, Costa Rica: SALTRA/IRET-UNA; 2103:53-56. http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10. Accessed December 22, 2013.

- 59.Solís-Zepeda G. Impacto de las medidas preventivas para evitar el deterioro de la función renal por el Síndrome de Golpe por Calor en trabajadores agrícolas del Ingenio San Antonio del Occidente de Nicaragua, Ciclo Agrícola 2005-2006. León: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua; 2007.

- 60.Crowe J., Wesseling C., Robles-Ramírez A. Empirical data from Costa Rica on heat stress and hydration. In: Wesseling C., Crowe J., Hogstedt C., Jakobsson K., Lucas R., Wegman D., editors. Mesoamerican Nephropathy: Report From the First International Research Workshop on MeN. SALTRA/IRET-UNA; Heredia, Costa Rica: 2013. pp. 109–111.http://www.saltra.una.ac.cr/index.php/sst-vol-10 Accessed October 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Athuraliya N.T., Abeysekera T.D., Amerasinghe P.H. Uncertain etiologies of proteinuric chronic kidney disease in rural Sri Lanka. Kidney Int. 2011;80(11):1212–1221. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johner S.A., Libuda L., Retzlaff A., Joslowski G., Remer T. Urinary fructose: a potential biomarker for dietary fructose intake in children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(11):1365–1370. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakayama T., Kosugi T., Gersch M. Dietary fructose causes tubulointerstitial injury in the normal rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298(3):F712–F720. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00433.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gersch M.S., Mu W., Cirillo P. Fructose, but not dextrose, accelerates the progression of chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293(4):F1256–F1261. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00181.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Suga S.I., Phillips M.I., Ray P.E. Hypokalemia induces renal injury and alterations in vasoactive mediators that favor salt sensitivity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281(4):F620–F629. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.4.F620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson R.J., Nakagawa T., Jalal D., Sanchez-Lozada L.G., Kang D.H., Ritz E. Uric acid and chronic kidney disease: which is chasing which? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(9):2221–2228. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO). CAO media statement: local collaboration in Nicaragua aims to catalyze an international response to address chronic kidney disease in Central America. http://www.cao-ombudsman.org/cases/document-links/documents/Mediastatement_Nicaraguachronickidneydisease_012612.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2013.

- 68.International Finance Corporation (IFC). Ingenio Montelimar, summary of investment information. http://ifcext.ifc.org/ifcext/spiwebsite1.nsf/651aeb16abd09c1f8525797d006976ba/8d7b9f97c4c64fa585257b26007872ff?OpenDocument. Accessed July 25, 2013.