Abstract

Background

Provision of rehabilitation with the aim of restoring personal independence in elderly hemodialysis patients faces several challenges.

Design

Quality improvement report.

Setting & Participants

First 3 years of experience of an inpatient geriatric hemodialysis rehabilitation program in Toronto. Patients with new-onset disability from prolonged illness or an acute event rendering them incapable of living independently.

Quality Improvement Plan

Provision of in-patient rehabilitation with on-site dialysis; a simplified referral system; preferential admission of elderly dialysis patients; short daily dialysis sessions; integrated multidisciplinary care by experts in rehabilitation, geriatric medicine, and nephrology; and reciprocal continued medical education among staff.

Measures

Outcome measures were percentage of patients discharged home, score on the Functional Independence Measure, and attainment of rehabilitation goals.

Results

In the first 36 months, 164 dialysis patients aged 74.5 ± 7.8 years were admitted. On admission, patients had a mean Charlson comorbidity score of 7.8 ± 2.5, 98% had difficulty walking, and 84% required help with bed-to-chair transfers. After a median of 48.5 days, 111 patients (69%) were discharged home; 15 patients (9%), to an assisted-living setting; 20 patients (12%), to a long-term care facility; and 18 patients (11%), to other facilities for acute or palliative care. Of those completing therapy, 82% met some or all of their rehabilitation goals.

Limitations

The program relied on the leadership and drive of key personnel. Discharge disposition as an outcome can be affected by many factors, and definition of attainment of rehabilitation goals is arbitrary.

Conclusion

The introduction of an integrated dialysis rehabilitation service can help older dialysis patients with new-onset functional decline return to their home. Am J Kidney Dis 00:00-00

Index Words: Quality improvement report, hemodialysis, geriatric rehabilitation, functional impairment measure, nursing home

Editorial, p. 5

Cross-sectional studies showed that more than 50% of older dialysis patients living at home needed supervision or assistance with at least 1 activity of daily living,1 and an increasing number required long-term nursing home care.2, 3 On average, the life expectancy of dialysis patients aged 75 to 79 years was estimated to be 2.64 to 3.2 years from the time of dialysis therapy initiation, with a trend to improved survival in more recent years (S.V. Jassal et al, manuscript submitted). With continued aging of the dialysis population, we believe an even larger number of dialysis patients will require long-term nursing care, whereas many others will need social support services to continue to live at home.

We and others previously documented that older dialysis patients are vulnerable to mobility difficulties, falls, undetected spinal fractures, and functional disability.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 This in turn predisposes individuals to increased health care utilization and long-term institutionalization.12 The impact of disability on both the patient and the health care system is high. Functional dependency is associated with increased hospitalization, caregiver burden, and need for nursing home placement.13, 14, 15 Cardiac rehabilitation in dialysis patients is associated with a 35% decreased risk of cardiac mortality16; however, few data are available showing the outcome with geriatric rehabilitation services. Studies of geriatric rehabilitation in dialysis patients are limited to a few case reports or retrospective studies with small sample sizes ranging from 3 to 40 subjects.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Assuming studies from the nondialysis literature24, 25 are applicable to the dialysis population, one would predict that geriatric rehabilitation could limit functional impairment, prolong personal independence, and decrease the need for nursing home care in dialysis patients.

In 2002, the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, in partnership with the University Health Network, developed a dedicated dialysis rehabilitation service. This report describes the experience of the program during its first 3 years of operation.

Methods

Perceived Barriers

Until 2001, rehabilitation was available for dialysis patients in Toronto in either acute-care medical/geriatric units or nondialysis rehabilitation units. Most commonly, patients remained in the acute-care hospital ward and therapists would come and deliver therapy for short periods on the acute-ward floor. Therapy sessions occurred on average 2 to 5 times a week, but ranged in duration from 15 to 40 minutes according to the acute-care workload. Less commonly, patients were transferred to specialized rehabilitation units where they would receive formal therapy sessions in an environment promoting independence. Patients would be temporarily discharged to attend their 3-times-weekly dialysis treatment at offsite dialysis units. It appeared that in many cases, the need to make acute-care beds available and the perception that dialysis patients did poorly with rehabilitation meant that patients often were not given sufficient opportunities for rehabilitation before being advised to seek nursing home placement.

The following barriers were noted by S.V.J. during the preceding years of training and practicing in geriatric medicine and nephrology:

-

1

Limited number of available beds in designated rehabilitation facilities that accepted hemodialysis patients.

-

2

Reluctance to admit dialysis patients to rehabilitation beds because of medical complexity and the need for special drug and diet regimens.

-

3

Under-referral; because nephrology staff were unsure of the appropriateness of candidates, the referral system was confusing and time consuming and acceptance rates were low.

-

4

Shortened or cancelled therapy sessions because therapists viewed patients as too unwell; patients reported dyspnea before dialysis or fatigue after dialysis; patients were anxious, particularly about not missing their dialysis session; and too-early or too-late transportation.

-

5

Lack of integration of treatment goals for acute medical care and rehabilitation therapy. When patients remained in acute care for ongoing rehabilitation therapy, the focus of the main health care team was acute medical management, and when patients were transferred to rehabilitation units, the main focus was rehabilitation care with little attention given to ongoing medical issues.

-

6

Limited interdisciplinary communication about acute medical problems that interfered with the ability to participate in rehabilitation therapy; for example, pain management in the face of renal failure, edema resulting in decreased ankle mobility, dyspnea with exertion, orthostasis, and effects of sedative medications.

Program Description

Program goals were to: (1) increase the number of elderly dialysis patients who remained independent in the community after acute or subacute functional decline, and (2) limit the use of acute-care facilities for these patients during rehabilitation therapy.

Key planning personnel included S.V.J., nephrology and rehabilitation program leaders, and senior executives from both institutions. Discussions and planning started in July 2000. Approval and funding (from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care) was secured in January 2001, and construction began in November 2001. A 6-station dialysis suite was built in preexisting space 2 floors below the inpatient ward unit within the rehabilitation hospital. The program was designed with several unique features, including 12 dedicated nephrology rehabilitation beds, a simplified timely referral process, and the ability to provide short daily dialysis on site. The first patient was admitted to the service in May 2002.

The program offered inpatient geriatric rehabilitation services to hemodialysis-dependent seniors who had a history of complex medical problems and an acute functional decline. Staffing included occupational therapy and physiotherapy (ratio, 1:6 patients), dietician and pharmacist (both staffed at 0.2 full-time equivalent), and access to other services, including nurses, speech and language therapists, social workers, and geriatric medicine specialists, as required. Dialysis care was provided by the University Health Network in the form of a satellite unit that offered on-site dialysis services on a daily basis. Medical coverage for the ward and dialysis units was provided by a hospitalist (from Toronto Rehabilitation Institute) and a nephrologist (from University Health Network). Both attended on a part-time basis and provided emergency coverage. Weekly interdisciplinary team meetings led by the nephrologist involved staff from rehabilitation, geriatric, and nephrology disciplines.

Patient eligibility was determined on an individual basis. Referrals were received by the ward admissions officer, screened by the social worker, and reviewed weekly by members of the rehabilitation team, which included nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, social work professionals, and physicians. Approval for admission was granted within 24 hours of the meeting and was based on the ability of a patient to participate in rehabilitation sessions and clearly identify rehabilitation goals. Patients requiring ventilation, inotropic support, or cardiac monitoring, as well as those with untunneled hemodialysis catheters, were not eligible. Feeding tubes, tracheostomies, or lack of social support and stable mild cognitive impairment or dementia were not contraindications. Initially, the program was designed for those older than 65 years; however, with time, this age limit was lowered to those older than 55 years, with priority for those aged 65-plus years. The program goal was to accept only those who, at the time of transfer to rehabilitation, would be considered unable to manage their own personal care if returned to their usual home setting.

Formal daily physical and/or cognitive exercises were scheduled on average twice daily, lasting from 30 to 60 minutes per session depending on patient tolerance. Informal and self-directed therapy was provided throughout the full day. Each patient was dialyzed for 2 hours 6 times weekly. In all cases, dialysis was scheduled either early (∼8:00 am to 10:00 am) or late (∼4:00 pm to 6:00 pm) in the day to limit interference with rehabilitation sessions. Strict renal diets often were liberalized to improve nutritional balance, patient morale, and participation. Each patient was assessed by the pharmacist to streamline medication regimens and minimize or avoid adverse drug effects.

Measures

We used 3 outcome measures to evaluate the program. The first was whether patients met the rehabilitation goals. At the time of admission, the patient and staff jointly identified rehabilitation goals for the admission. These goals were individualized and based upon personal lifestyle and living circumstances. Examples of such goals ranged from personal care needs, such as the ability to toilet and wash independently, to higher functional goals, such as climb stairs within the home or walk to the store independently. Because goals varied from individual to individual, we determined whether goals had been met by using a 3-point scale (did not meet goals; met some, but not all goals; and met all admission goals). This score was based on the consensus of the team at the time of discharge.

The second measure was the place of discharge as home, assisted-care facilities (group homes, retirement homes, or supervised-living settings), residential facilities (convalescent care, nursing home, home for the aged, or long-term-care facility), and other facilities (temporary accommodation; acute-care, and palliative-care facilities).

The third measure was change in Functional Independence Measure (FIM) score between admission and discharge.26 In keeping with National Reporting Standards in Canada for all rehabilitation facilities, severity of functional impairment, measured by means of FIM score, was recorded at the time of admission and discharge.27 Two individuals assumed responsibility for scoring. Consisting of 13 motor and 5 cognitive domains, the FIM instrument is a widely used rehabilitation outcome measure and has well-established validity and reliability for this use.27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 Motor items include disability assessment in feeding, grooming, dressing, toileting, and mobility. Cognitive items assess communication, social interaction, problem solving, and memory (see Appendix). Scores range from 1 (totally dependent) to 7 (totally independent) for each of the 18 items; a maximum score of 126 indicates total functional independence.

Sources of Data

All patients admitted to the program from May 2002 to December 2005 were included in the program evaluation. Clinical and demographic data were collected prospectively on a customized patient-care database (Microsoft Access 2000; Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). Data included time since starting renal replacement therapy (dialysis vintage), reason for acute functional decline necessitating admission, cause of end-stage renal disease, and presence of comorbid conditions (depression, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, arrhythmias, other heart disease [such as valvular lesions], hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, respiratory disease, malignancy, hepatobiliary disease, gastrointestinal disease, neurological disease [excluding cerebrovascular disease], skin ulcers; arthritis, hematologic disease, endocrinologic disease, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or renal bone disease). Comorbidity burden was reported as both a total count of all conditions and Charlson Comorbidity Index score.33, 34 Baseline blood tests, performed within 48 hours of admission, included hemoglobin, iron stores, creatinine, electrolytes, serum albumin, calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone, and C-reactive protein. Data from the clinical database and the hospital administrative database were linked by using the unique hospital file number, date of admission, and date of discharge. Missing or contradictory information was confirmed by means of manual data extraction from the hospital charts by a trained observer.

The local hospital research ethics board approved the evaluation and publication of this quality improvement report.

Statistical Analysis

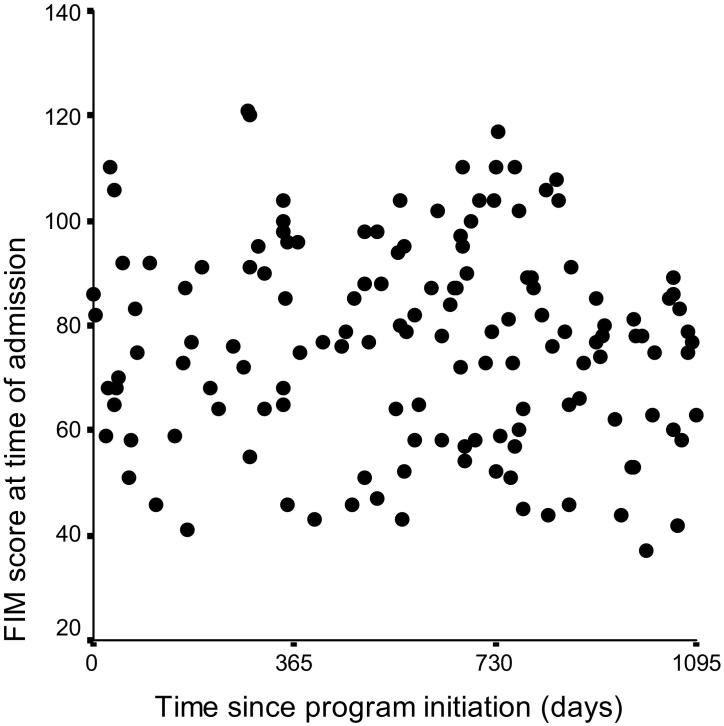

Demographic data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (mean ± SD for continuous data, percentages for categorical data). Median and quartiles were used to describe values found to have a skewed distribution. We plotted admission FIM score over time starting from May 2002, when the unit opened, to assess whether it changed over time.

Results

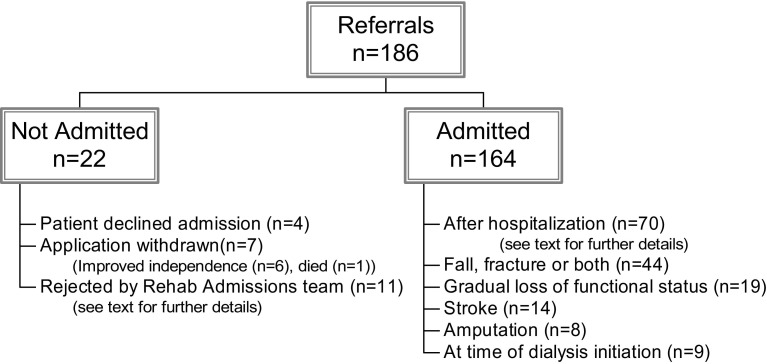

One hundred eighty-six referrals were received during a 36-month period. Twenty-two patients were not admitted either because they refused care, their application was withdrawn, or they were not believed to be suitable for rehabilitation (Fig 1). Of those not believed to be suitable for rehabilitation, 8 had ongoing acute medical problems, 2 were believed to have no rehabilitation goals, and 1 was known to the program from a previous admission and believed to have no motivation to improve. One patient was refused admission on the basis of infection control during the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in Toronto.

Figure 1.

Patients referred, admitted, and not admitted.

A total of 164 patients were admitted from 8 secondary or tertiary-care nephrology units in Toronto and 15 patients (9.1%) were admitted from home, whereas the remaining patients were admitted from acute care institutions (Fig 1). The largest proportion was admitted after acute hospitalization. Of these, 36 had required intensive-care therapy (eg, for calciphylaxis with sepsis requiring inotrope therapy, pneumonia with sepsis requiring inotrope therapy, end-stage liver cirrhosis with actively bleeding varices, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and deep-vein thrombosis, fungal peritonitis with bowel obstruction requiring surgical care, and vascular or cardiac bypass surgery with postoperative complications). Only 23 patients had “simple” reasons for their prior hospital admission. These included patients with vasculitis (n = 3), myeloma (n = 1), joint arthroplasty (n = 1), tuberculous peritonitis (n = 1), uncomplicated fungal peritonitis (n = 2), and more common conditions, such as catheter sepsis, nausea and vomiting, fluid overload, and pneumonia.

Patients had a mean age of 74.5 years (range, 58 to 92 years) at the time of admission. Most (51.2%) were women, 51.2% had diabetes, and 17.7% were not fluent in English (Table 1). Thirty-four percent of patients had started hemodialysis therapy within 6 months of admission for rehabilitation. Before admission, 96.5% of all patients lived in a private home or apartment, and 3.6% lived in either an assisted-living or long-term-care setting. All patients had multiple comorbidities, with a mean of 7.9 ± 2.4 comorbid conditions and Charlson comorbidity score of 7.8 ± 2.5 (Table 1). Serum chemistry test results suggested a high incidence of malnutrition and/or inflammation because 42.1% of patients had ferritin values of 223 ng/mL (μg/L) or greater, 25.6% had a C-reactive protein level greater than the laboratory normal range (≥13 mg/L), 20.1% had a serum albumin level of 3 g/dL or less (≤30 mmol/L), and 17.1% had a hemoglobin level less than 9.5 mg/L (<95 g/L) despite therapy with an erythropoietic agent and iron.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics of Patients Admitted to the Rehabilitation Program

| Demographic data | N = 164 |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 74.5 ± 7.8 |

| Women | 84 (51) |

| Fluent in English | 134 (82) |

| Dialysis vintage (y) | 1.4 (0.2-5.0) |

| Cause of end-stage renal disease | |

| Diabetes (or combination of diabetes mellitus and hypertension) | 64 (39) |

| Glomerulonephritis or vasculitis | 34 (21) |

| Hypertension | 32 (20) |

| Other | 26 (16) |

| Unknown | 8 (5) |

| Concomitant comorbid condition(s) | |

| Hypertension | 139 (84.8) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 101 (61.6) |

| Diabetes | 84 (51.2) |

| Cognitive impairment⁎ | 76 (46.3) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 71 (43.3) |

| Congestive heart failure | 69 (42.1) |

| Chronic lung disease | 61 (37.2) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 60 (36.6) |

| Depression | 53 (32.3) |

| Obesity | 21 (12.8) |

| Laboratory results at baseline | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.0 ± 1.4 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 178 (69-352) |

| Iron saturation | 0.16 (0.12-0.27) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.37 ± 0.43 |

| Calcium (mg/L) | 9.5 ± 0.8 |

| Phosphate (mg/L) | 4.4 ± 3.0 |

| Intact parathyroid hormone (ρg/mL) | 18.2 (8.7-48.7) |

| C-Reactive protein (mg/L) | 15.5 (5.0-36.2) |

Note: Values expressed as mean ± SD, number (percent), or median (quartiles). To convert hemoglobin in g/dL to g/L, multiply by 10; ferritin in ng/mL to μg/L, multiply by 1; albumin in g/dL to g/L, multiply by 10; calcium in mg/L to mmol/L, multiply by 0.2495; phosphate in mg/L to mmol/L, multiply by 0.3229, parathyroid hormone in pg/mL to ng/L, multiply by 1.

Defined as either a clinical diagnosis of dementia made by the primary physician or a Mini-Mental State Examination score of 24 or less.

Median length of stay (LOS) was 48.5 days (quartiles, 32 to 72 days). Rehabilitation outcomes are listed in Table 2. Admission FIM scores were available for all patients (mean score, 76.4 ± 19.6; median, 77; range, 37 to 121; Table 3). To our surprise, admission scores did not change over time (Fig 2). Discharge FIM scores were available for all except 2 individuals who had a planned discharge. Of 20 patients who were transferred to and did not return from acute care, FIM scores were available for only 9. Discharge FIM scores followed a skewed distribution, suggesting possible ceiling effects,35 with a median score of 101.5 (quartiles, 81 to 114; range, 15 to 124). Mean change in FIM score was 21.5 ± 16.1 (range, −24 to +64). Eleven patients had no change in or worsening of their functional status despite rehabilitation therapy.

Table 2.

Achievement of Rehabilitation Goals and Discharge Disposition

| Rehabilitation Goals (total N = 164) | Discharged to |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home (N = 111) | Assisted-Living Setting (N = 15) | Long-Term Care (N = 20) | Acute or Palliative Care (N = 18) | |

| Met all (N = 110) | 90 (54.9) | 13 (7.9) | 5 (5.0) | 2 (1.2) |

| Met some, but not all (N = 14) | 11 (6.7) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) |

| Met few (N = 40) | 10 (6.1) | 0 (0) | 14 (8.5) | 16 (9.8) |

Note: Values expressed as number (percent).

Table 3.

FIM Scores on Admission and Discharge

| FIM score on admission (n = 164) | 77.0 (60.5-90.8) |

| FIM score at discharge (n = 151) | 101.5 (81.0-114.0) |

| Change in FIM scores during admission period | 18.0 (5.0-30.0) |

Note: Values expressed as median (quartiles).

Abbreviation: FIM, Functional Independence Measure.

Figure 2.

Functional Independence Measure (FIM) scores at admission during first 3 years of the program.

Forty individuals were transferred to acute care, on 46 occasions. Thirty-six transfers were attributable to an acute medical illness (eg, myocardial infarction, sepsis, or gangrene) requiring hospitalization, 8 were for treatment of a dialysis access–related complication (eg, bleeding, thrombosis, or stenosis), and 2 patients were transferred to await palliative care. Eighteen patients did not return to rehabilitation after transfer. Of those who returned, median time in acute care was 7.5 days (quartiles, 3.3 to 12.0). One patient was kept in acute care for 79 days before his or her return.

Discussion

In this report, we describe our experience with a specialized dialysis rehabilitation program designed for older dialysis patients with functional limitations. Our data suggest that geriatric rehabilitation is feasible for older hemodialysis patients after acute care hospitalization or acute loss of function, and a substantial proportion of patients can return to their homes. Based on the impressions of the authors (S.V.J., R.L.), providing dialysis in short daily sessions and integrating care in a multidisciplinary team were key ingredients for success of the program. Whereas short daily dialysis was designed primarily to increase rehabilitation efficiency by limiting scheduling conflicts and interference between medical and rehabilitation treatments,17 we heard from patients that they preferred daily dialysis and reported higher energy levels. We believe short daily dialysis may have been less exhausting for patients, allowed more dietary flexibility, and improved fluid and electrolyte control. In addition, patients seemed less anxious about their dialysis schedule and overall were very willing to participate in rehabilitation treatments. We also noted increased collaboration between caregivers over time, with detailed discussion of the goals, achievements, and challenges for each patient in the weekly team meetings. We noted reciprocal continued medical education between staff of different disciplines and close collaboration between the various health professions involved in dialysis and rehabilitation care.

Randomized controlled trials showed that rehabilitation prevented admissions to nursing homes and shortened the length of hospitalizations.24, 25, 36 Our data suggest this also may be true for dialysis patients. Comparisons with previously published studies are limited because most studies were small, involved younger dialysis patients, and omitted clinical details about concurrent comorbid illnesses, diabetes status, and so on.17, 18, 19, 22, 23 Only 1 study involved dialysis patients with an average age older than 70 years.20 In that study, 80% of patients did poorly with rehabilitation. In other studies, dialysis patients were often 10 to 15 years younger and were admitted after acute surgical procedures. The largest of these, by Forrest et al,17 reported outcomes for 40 dialysis patients. In their study, only 8 of 40 patients were reported as “medically complicated.” Average LOS was 12 days, substantially shorter than the LOS in our population (average LOS, 48 days). Age, patient comorbidity, and differences in health care systems may explain these discrepancies. In Canada, health care is provincially funded and therefore accessible to all regardless of health insurance coverage. Therefore, we believe a more appropriate comparison group may be nondialysis patients admitted to a geriatric facility within Canada. One such study is by Patrick et al.36 In that study, non–dialysis-dependent geriatric patients admitted for rehabilitation after an acute hospitalization had similar overall improvements in raw FIM scores from the time of admission to discharge. LOS also was similar.

Some features of our program are unique and may be difficult to reproduce in other centers. In particular, both the nephrologist (S.V.J.) and the hospitalist (R.L.) involved in our program had a strong interest in rehabilitation and care of older dialysis patients, and their enthusiasm may have had a significant role to generate momentum, particularly in the early stages of the program. Our outcome measures of achieving prespecified rehabilitation goals and the discharge destination are subjective, and although they have face validity, they are not validated. Furthermore, the discharge destination may be influenced by many factors, including social and financial resources. However, use of the FIM score is mandated across Canada and previously was validated.37, 38, 39 Although ordinal and prone to a high incidence of both ceiling and floor effects, use of the FIM score allows comparisons of our data with those of other units.

In conclusion, our data suggest that older hemodialysis patients can benefit from specialized geriatric dialysis rehabilitation. We are continuing to monitor the quality of our program.39 We also are planning extensions to the program to include access for younger patients and incorporation of musculoskeletal and acute brain injury rehabilitation services.

Acknowledgements

Support: None.

Financial Disclosure: None.

Appendix.

Details of Parameters Measured as Part of the Functional Independence Measure

-

1

Ability to feed oneself.

-

2

Ability to groom oneself (includes oral hygiene, washing hands and face, combing hair, and shaving or makeup application, if appropriate).

-

3

Ability to bathe oneself (includes showering).

-

4

Ability to dress upper body.

-

5

Ability to dress lower body.

-

6

Ability to toilet self (includes removing clothing, cleaning, and readjusting clothing),

-

7

Bladder control.

-

8

Bowel control.

-

9

Ability to transfer from bed to chair or vice versa.

-

10

Ability to get on and off toilet (eg, grab bar or special seat).

-

11

Ability to get in and out of bath or shower.

-

12

Ability to walk 50 m.

-

13

Ability to climb a flight of stairs.

-

14

Comprehension (of such complex information as family matters or current events).

-

15

Ability to express complex and abstract ideas (family matters or current events).

-

16

Social interactions.

-

17

Problem solving skills (eg, managing bank account or confronting interpersonal problems).

-

18

Memory, eg, for people, routines, and tasks.

References

- 1.Jassal S.V., Li M., Cook W.L. Survival at what cost?: A study of disability in older dialysis subjects. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17 S-FP0398, (abstr) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toronto District Health Council: The Rising Tide of End Stage Renal Disease in Toronto. Toronto District Health Council; Toronto, Ontario, Canada: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Renal Data System: Incidence and prevalence of ESRD in patients 75 or over, in USRDS 2005 Annual Data Report, chap 2. The National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2005. pp. 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Renal Data System: Morbidity and mortality, in USRDS 2006 Annual Data Report, chap 6. The National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2006. pp. 121–144. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jassal S.V., Douglas J.F., Stout R.W. Increasing dependency on dialysis: An age old problem, in 4th International Conference in Geriatric Nephrology and Urology, Toronto, Canada, International Society of Geriatric Nephrology. 1996:10. (abstr) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naglie G., Jassal S.V., Tomlinson G., Richardson R. Frailty in elderly hemodialysis patients at a large university hospital dialysis center. Gerontologist. 2002;42:239–240. (special issue 1) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook W.L., Jassal S.V. Prevalence of falls amongst seniors maintained on hemodialysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005;37:649–652. doi: 10.1007/s11255-005-0396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook W.L., Tomlinson G., Donaldson M. Falls and fall-related injuries in older dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1197–1204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01650506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jamal S.A., Leiter R.E., Jassal V., Hamilton C.J., Bauer D.C. Impaired muscle strength is associated with fractures in hemodialysis patients. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1390–1397. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0133-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altutepe L., Levendoglu F., Okudan N. Physical disability, psychological status, and health-related quality of life in older hemodialysis patients and age-matched controls. Hemodial Int. 2006;10:260–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2006.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sterky E., Stegmayr B.G. Elderly patients on haemodialysis have 50% less functional capacity than gender- and age-matched healthy subjects. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2006;39:423–430. doi: 10.1080/00365590500199319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kravitz R.L., Greenfield S., Rogers W. Differences in the mix of patients among medical specialties and systems of care: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1992;267:1617–1623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fried T.R., Bradley E.H., Williams C.S., Tinetti M.E. Functional disability and health care expenditures for older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2602–2607. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.21.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill T.M., Gahbauer E.A., Allore H.G., Han L. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:418–423. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill T.M., Allore H.G., Hardy S.E., Guo Z. The dynamic nature of mobility disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kutner N.G., Zhang R., Huang Y., Herzog C.A. Cardiac rehabilitation and survival of dialysis patients after coronary bypass. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1175–1180. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forrest G., Nagao M., Iqbal A., Kakar R. Inpatient rehabilitation of patients requiring hemodialysis: Improving efficiency of care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1949–1952. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forrest G.P. Inpatient rehabilitation of patients requiring hemodialysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:51–53. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrison S.J., Merritt B.S. Functional outcome of quadruple amputees with end-stage renal disease. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;76:226–230. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199705000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank C., Morton A.R. Rehabilitation of geriatric patients on hemodialysis; A case series. Geriatr Today. 2002;5:136–139. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenspun B., Harmon R.L. Rehabilitation of patients with end-stage renal failure after lower extremity amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67:336–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cowen T.D., Huang C.T., Lebow J. Functional outcomes after inpatient rehabilitation of patients with end-stage renal disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:355–359. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Czyrny J.J., Merrill A. Rehabilitation of amputees with end-stage renal disease: Functional outcome and cost. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;73:353–357. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199409000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gill T.M., Baker D.I., Gottschalk M., Peduzzi P.N., Allore H., Van Ness P.H. A prehabilitation program for the prevention of functional decline: Effect on higher-level physical function. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stuck A.E., Minder C.E., Peter-Wuest I. A randomized trial of in-home visits for disability prevention in community-dwelling older people at low and high risk for nursing home admission. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:977–986. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.7.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright, J. The FIM. The Center for Outcome Measurement in Brain Injury. Available at: http://www.tbims.org/combi/FIM. Accessed March 22, 2007.

- 27.Dodds T.A., Martin D.P., Stolov W.C., Deyo R.A. A validation of the Functional Independence Measurement and its performance among rehabilitation inpatients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90119-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ottenbacher K.J., Hsu Y., Granger C.V., Fiedler R.C. The reliability of the Functional Independence Measure: A quantitative review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:1226–1232. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollak N., Rheault W., Stoecker J.L. Reliability and validity of the FIM for persons aged 80 years and above from a multilevel continuing care retirement community. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:1056–1061. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickson H.G., Kohler F. Interrater reliability of the 7-level Functional Independence Measure (FIM) Scand J Rehabil Med. 1995;27:253–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kidd D., Stewart G., Baldry J. The Functional Independence Measure: A comparative validity and reliability study. Disabil Rehabil. 1995;17:10–14. doi: 10.3109/09638289509166622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton B.B., Laughlin J.A., Fiedler R.C., Granger C.V. Interrater reliability of the 7-level Functional Independence Measure (FIM) Scand J Rehabil Med. 1994;26:115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charlson M.E., Pompei P., Ales K.L., MacKenzie C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Manen J.G., Korevaar J.C., Dekker F.W., Boeschoten E.W., Bossuyt P.M., Krediet R.T. Adjustment for comorbidity in studies on health status in ESRD patients: Which comorbidity index to use? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:478–485. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000043902.30577.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pouwer F., Snoek F.J., Heine R.J. Ceiling effect reduces the validity of the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:2039. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.11.2039b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patrick L., Knoefel F., Gaskowski P., Rexroth D. Medical comorbidity and rehabilitation efficiency in geriatric inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1471–1477. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panesar B.S., Morrison P., Hunter J. A comparison of three measures of progress in early lower limb amputee rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15:157–171. doi: 10.1191/026921501669259476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gosman-Hedstrom G., Svensson E. Parallel reliability of the Functional Independence Measure and the Barthel ADL index. Disabil Rehabil. 2000;22:702–715. doi: 10.1080/09638280050191972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dodds T.A., Martin D.P., Stolov W.C., Deyo R.A. A validation of the Functional Independence Measurement and its performance among rehabilitation inpatients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90119-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]