Abstract

Clinically relevant features in patients with systemic mastocytosis (SM) include the cosmetic burden of lesional skin, mediator-related symptoms, and organ damage resulting from mast cell (MC) infiltration in advanced forms of SM. Regardless of the SM variant, expansion of neoplastic MC in the skin and other organs is triggered by mutant forms of KIT, the most prevalent being D816V. Activation of MC with subsequent release of chemical mediators is often caused by IgE-dependent mechanisms in these patients. Midostaurin, also known as PKC412, blocks the kinase activity of wild-type KIT and KIT D816V, counteracts KIT-dependent growth of neoplastic MC, and inhibits IgE-dependent mediator secretion. Based on this activity-profile, the drug has been used for treatment of patients with advanced SM. Indeed, encouraging results have been obtained with the drug in a recent multi-center phase II trial in patients with advanced SM, with an overall response rate of 60% and a substantial decrease in the burden of neoplastic MC in various organs. Moreover, midostaurin improved the overall survival and relapse-free survival in patients with advanced SM compared with historical controls. In addition, midostaurin was found to improve mediator-related symptoms and quality of life, suggesting that the drug may also be useful in patients with indolent SM suffering from mediator-related symptoms resistant to conventional therapies or those with MC activation syndromes. Ongoing and future studies will determine the actual value of midostaurin-induced MC depletion and MC deactivation in these additional indications.

Keywords: mast cells, targeted drugs, IgE, mast cell activation, mast cell leukemia

Introduction

Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is a hematopoietic neoplasm characterized by expansion and accumulation of neoplastic mast cells (MC) in one or more internal organ systems, including the bone marrow (BM), liver, spleen, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract [1–3]. Based on organ involvement and clinical course, SM can essentially be divided into indolent, smoldering, and advanced disease variants [4–10]. Patients with indolent SM (ISM) may suffer from mediator-related symptoms, osteopathy, and/or from the cosmetic consequences of the disease [4–7, 10–14]. Otherwise, ISM patients have a good prognosis with normal or near-normal life expectancy [10–16]. In contrast, patients with advanced SM, including aggressive SM (ASM), SM with an associated hematologic neoplasm (AHN), and MC leukemia (MCL) have a poor prognosis with reduced survival [5–9, 14–17]. In these patients, the ‘malignant’ expansion of neoplastic MC in the BM, liver, and other visceral organs leads to organ damage, also known as C-Findings [8–10]. Moreover, in advanced SM, neoplastic MC are often resistant to one or more cytoreductive drugs, including interferon-alpha (IFN-A) and cladribine (2CdA) [18–20]. These patients are candidates for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT) [21]. For those who are not eligible for SCT or refuse this therapy, investigational drugs are usually recommended [5, 9, 10, 22, 23]. In the past 10 years, several major efforts have been made to develop such drugs and to identify relevant therapeutic targets in neoplastic MC in advanced SM [24–27].

In over 80% of all patients with advanced SM, the KIT mutation D816V or other transforming KIT mutations are detectable in neoplastic cells [28–32]. These mutations cause ligand-independent activation of KIT and contribute to differentiation and expansion of MC in SM [25, 33]. Therefore, drugs interfering with the tyrosine kinase (TK) activity of KIT D816V have been proposed for patients with advanced SM [24–27, 34–36]. It is worth noting, however, that the D816V mutation of KIT confers resistance against several KIT kinase-inhibitors, including imatinib [25, 34–36].

Midostaurin was initially developed as a protein kinase C (PKC)-targeting drug [37]. However, it was soon discovered that midostaurin exerts strong inhibitory effects on a number of additional oncogenic kinases relevant in hematology [37]. In subsequent studies, midostaurin was found to suppress not only the kinase activity of wild-type (wt) KIT, but also mutated forms of the receptor, including D816V [25, 27, 35, 36]. Moreover, midostaurin was found to inhibit the growth of neoplastic MC exhibiting KIT D816V [25, 27]. Furthermore, midostaurin was found to block IgE-dependent mediator release in human MC and basophils [38]. Based on these observations and first pilot cases, clinical trials were designed to explore anti-neoplastic effects of midostaurin in patients with advanced SM. Results from first clinical trials are now available and indeed suggest that a majority of patients with advanced SM respond to therapy with this agent [39, 40].

In the current article, we review the preclinical activities and the pharmacologic properties of midostaurin as well as the clinical efficacy of the drug in advanced SM. Moreover, we discuss additional indications of the drug in the field of SM and MC activation syndromes (MCAS) for which the drug may be useful. Finally, we discuss potential mechanisms of resistance against midostaurin and explore the potential value of drug combinations and other alternative therapies that may be useful and may overcome drug resistance.

Structure and target spectrum of midostaurin

Midostaurin, originally termed PKC412, is a semi-synthetic derivative of the alkaloid staurosporine, a well-known inhibitor of PKC (Figure 1A) [41]. Although initially considered a rather specific pharmacologic inhibitor of PKC, midostaurin interacts with a broad spectrum of clinically relevant kinase-targets, including KIT, FLT3, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA), PDGFRB, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor KDR, and FES (Table 1) [37, 42, 43]. Moreover, unlike other kinase inhibitors, midostaurin was found to inhibit not only the kinase activity of wt KIT, wt FLT3, and wt PDGFRA/B, but also the kinase activity of KIT D816V, other KIT mutants, FLT3 ITD, and various mutant forms of PDGFR, all of which are relevant clinically as they mediate resistance against other TK inhibitors (TKI) [25–27, 44–46]. Based on these observations, midostaurin is an emerging new anti-cancer agent in applied hematology. More recently, the kinase interaction profile of midostaurin was analyzed in the context of neoplastic MC [43]. In addition, the kinase interaction profile of midostaurin has been compared with that of two major metabolites, CGP62221 and CGP52421 [43]. Chemical proteomics profiling and drug-competition experiments revealed that midostaurin interacts with KIT and several additional oncogenic kinases, and also with other clinically relevant kinase-targets, such as SYK, in lysates prepared from primary MCL cells and HMC-1 cells [43]. SYK is an IgE-receptor downstream target that plays a major role in IgE-dependent MC activation [47, 48]. Interestingly, KIT and the key downstream-regulator FES were found to be recognized and dephosphorylated by midostaurin and CGP62221, but not by CGP52421, whereas SYK was recognized and blocked by both metabolites as well as by midostaurin [43]. These observations may be clinically relevant, in particular since CGP52421, following chronic dosing of midostaurin to patients, achieves pharmacologically relevant steady-state concentrations in vivo [49–52]. An overview of clinically relevant kinase targets recognized by midostaurin is shown in Table 1.

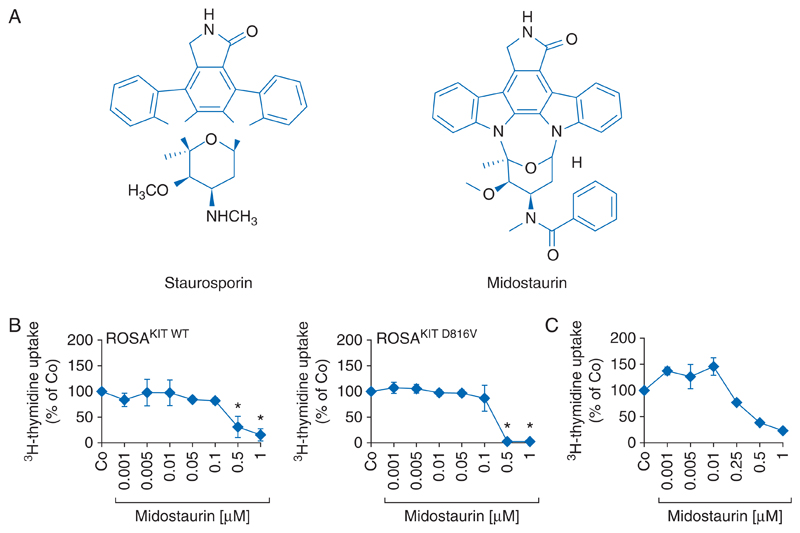

Figure 1. Chemical structure and anti-neoplastic effects of midostaurin.

(A) Chemical structure of staurosporin and its derivative midostaurin. (B) The human mast cell lines ROSAKIT WT (left panel) and ROSAKIT D816V (right panel) were incubated in control medium (Co) or with increasing concentrations of midostaurin (PKC412) at 37 °C for 48 h. Results represent the percent of control and are expressed as mean±SD of three independent experiments. *, P<0.05. (C) Primary mast cells of a patient with aggressive systemic mastocytosis were cultured in the absence (Co) or presence of various concentrations of midostaurin at 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, uptake of 3H-thymidine was measured. Results show the percent of control and are expressed as mean±SD of triplicates.

Table 1. Clinically relevant targets of midostaurin.

| Molecular targeta | Major target cell populations and disorders |

|---|---|

| KIT wt | Mast cells, AML blasts, GIST cells |

| KIT D816V | Mast cells in SM, AML blasts, GIST cells |

| KIT V560G | Mast cells in SM, GIST cells |

| KIT K509I | Mast cells in CM |

| FES | Mast cells in KIT D816V+ SM (KIT D816V-downstream-signaling) |

| FLT3 wt | Myeloid (progenitor) cells |

| FLT3 ITD | AML blasts |

| FLT3 D835H | AML blasts |

| FLT3 D835Y | AML blasts |

| FLT3 N841I | AML blasts |

| PDGFRA wt | Fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells |

| FIP1L1-PDGFRA (F/P) | Eosinophils, CEL, MPN-eo |

| F/P mutant forms | Eosinophils, CEL, MPN-eo |

| PDGFRB wt | Fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells |

| PDGFRB mutant forms | Eosinophils, CEL, MPN-eo |

| JAK2 | Myeloid cells, MPN cells |

| JAK3 | Various immune cells |

| AAK1 | Notch adaptor in neoplastic cells |

| SYK | IgE-R+ cells, IgE-R-downstream signaling |

| AURKA | Mitosis regulator in various neoplastic cells |

| AURKB | Mitosis regulator in various neoplastic cells |

| MARK3 | Oncogenic molecule in hepatocellular cancer |

| PKN1 | Wnt/β-catenin repressor in cancer cells |

| FGFR3 | B cells, multiple myeloma cells |

| FGFR3 TDII (K650E) | B cell lymphoma cells, multiple myeloma cells |

| TEL-FGFR3 | T cell lymphoma cells, MPN, AML blasts |

Molecular targets were identified in a cell-free screen [42] and in a chemical proteomics approach using primary neoplastic mast cells [43]. wt, wild-type; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; GIST, gastrointestinal stroma cell tumor; SM, systemic mastocytosis; CM, cutaneous mastocytosis; CEL, chronic eosinophilic leukemia; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; IgE, immunoglobulin E; JAK, Janus kinase; AURK, Aurora kinase.

Evidence that midostaurin blocks proliferation, survival, and activation of MC

Earlier preclinical studies have shown that midostaurin inhibits the proliferation of Ba/F3 cells engineered to express either wt KIT or KIT D816V [25, 35]. Moreover, midostaurin suppressed the growth and survival of the human MCL-derived cell lines HMC-1.1 expressing the KIT V560G mutation (but not KIT D816V) and HMC-1.2 expressing both KIT V560G and KIT D816V [25, 27]. In both cell lines, relevant and comparable IC50 values (50–250 nM) were obtained with midostaurin [25]. Similar effects were also seen when applying the drug in the recently established human MC lines ROSAKIT WT and ROSAKIT D816V [53]. In both cell lines, midostaurin exerts growth-inhibitory effects at submicromolar concentrations (Figure 1B). Furthermore, midostaurin was found to induce apoptosis and growth arrest in primary neoplastic MC obtained from patients with advanced SM (Figure 1C) [25, 27].

Midostaurin also produced synergistic growth-inhibitory effects in HMC-1 cells when combined with a number of targeted drugs, including other KIT inhibitors, cladribine (2CdA), BCL-2 family antagonists, or inhibitors of BRD4 [25, 27, 54–57]. In most studies, cooperative effects could be explained by the different target-interaction profiles these drugs exhibit [58]. For example, the synergistic effect of the drug combination ‘midostaurin + dasatinib’ was explained by inhibitory effects of dasatinib on BTK and LYN, since cooperative drug effects (midostaurin + dasatinib) were also obtained when applying the drug plus small interfering RNA (siRNA), namely ‘midostaurin + BTK-siRNA’ or ‘midostaurin + LYN-siRNA’ on neoplastic MC [58].

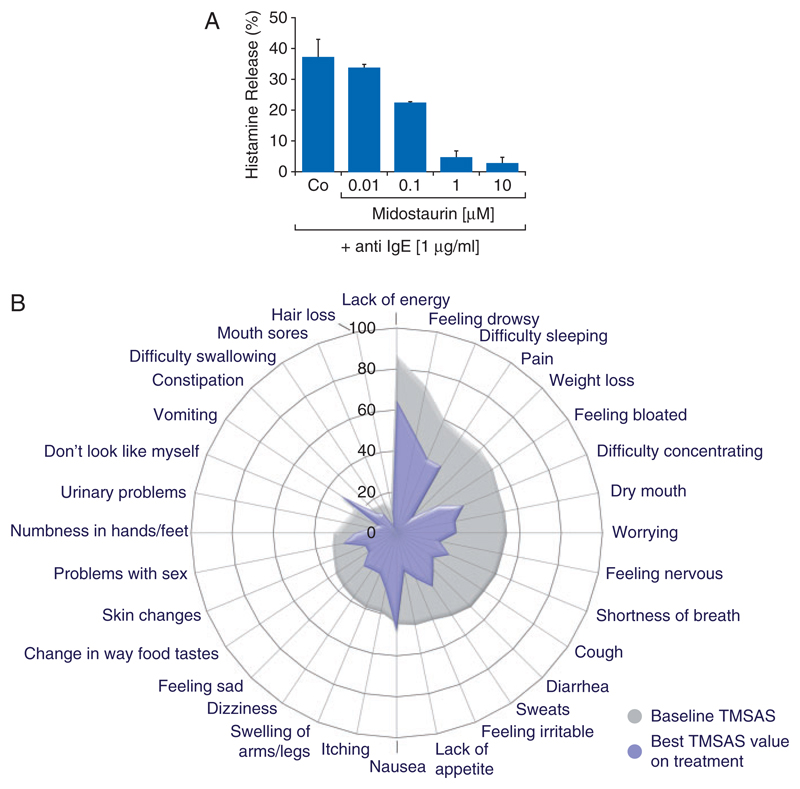

Another remarkable observation was that midostaurin almost completely blocks IgE-receptor mediated activation and mediator release in human MC and blood basophils (Figure 2A) [38, 43]. This effect was observed at pharmacologically relevant drug concentrations (0.5–2.0 μM) and may be explained by the strong effect of the drug on PKC, SYK, and other IgE receptor-downstream targets [43]. The effects of midostaurin on histamine release are dose-dependent, without a rebound effect or paradoxical stimulating effect at low concentrations, described for dasatinib in its effects on IgE-mediated histamine release [59]. More recently, midostaurin was also found to block IgE-dependent histamine release in ex vivo basophils obtained from SM patients receiving midostaurin [43]. It is also worth noting that midostaurin exerts little if any immunological side-effects in vivo (such as immunosuppression, lymphopenia, or hyperactivation of immune cells) at doses administered in clinical trials. Together, these data suggest that midostaurin is a promising agent that can target neoplastic cell growth as well as IgE-dependent cell activation in patients with SM.

Figure 2. Effect of midostaurin on mediator release and mediator-induced symptoms.

(A) Human basophils were incubated in control buffer or in the presence of various concentrations of midostaurin (as indicated). Histamine release was induced by incubating basophils with an anti-IgE antibody at 37 °C for 30 min. Histamine release was calculated as percent of total (cellular+extracellular) histamine and is expressed as mean±SD of triplicates. (B) Spider plot delineation of symptom improvement in patients with advanced SM. Symptoms were recorded in 79 assessable patients in the global phase II trial examining the effects of midostaurin in advanced systemic mastocytosis [39]. Symptoms were assessed by memorial symptom assessment scale (MSAS) at baseline and during treatment with midostaurin. The spider plot shows the baseline MSAS values (gray shading) and the MSAS values at the time of best symptom improvement by total MSAS scoring during treatment (blue area). Reproduced from Gotlib et al. [39] (copyright: Massachusetts Medical Society) in slightly modified form with permission from the editor.

Results from a global phase II trial in patients with advanced SM

Between 2009 and 2012 a global multi-center, open-label, phase II (single-arm) trial enrolled patients with advanced SM to determine the safety and efficacy of single agent oral midostaurin. The drug was administered continuously at a dose of 100 mg twice daily in 4-week cycles [39]. A total of 116 patients with ASM, SM-AHN, or MCL were eligible for safety evaluation, and of these, 89 patients were eligible for the evaluation of midostaurin’s efficacy based on the presence of organ damage attributable to SM (C-Findings). Treatment was continued until disease progression, death, or intolerable toxicity. The overall response rate was 60%, and thus the highest ever reported in this group of poor-risk patients [39]. More importantly, 45% of all patients achieved a major response defined by resolution of organ damage (disappearance of at least 1 C-Finding) [39]. The response rates and the duration of responses were similar in ASM and SM-AHN. Successful treatment was also accompanied by a substantial decrease in the BM MC burden (median best decrease: ‒59%) and in the serum tryptase level (median best decrease: ‒58%). The median overall survival (OS) was 28.7 months, and the progression-free survival 14.1 months (Table 2) [39]. The primary cause of death was progression of ASM to MCL or to advanced AHN, often in form of secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Among the 16 patients with MCL, 8 patients (50%) responded, including 7 with a major response. The median OS was 9.4 months for all MCL patients, but was not reached in responders. In a post hoc multivariate analysis, two outcome measures of midostaurin therapy, response (versus no response), and ≥50% (versus <50%) reduction in BM MC burden were associated with longer survival. In 56% of the patients, the dose of midostaurin was transiently or permanently reduced because of toxicity. In 32% of these patients, midostaurin could later be re-escalated to the starting dose of 100 mg twice daily. The most frequently recorded side-effects were low-grade nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea (Table 3) [39]. Grade 3/4 neutropenia, anemia, or thrombocytopenia developed in <50% of all patients, and in most of these patients, mild to moderate cytopenia had already been detected before therapy.

Table 2. Clinical responses to midostaurin in patients with advanced SM: results from the global phase II trial.

| Response and clinical endpoint | Data recorded in a global phase II triala | Improvement over historical controls |

|---|---|---|

| Overall response rate | 60% | Yes (<50%) |

| Overall response rate in MCL | 50% | Yes (<50%) |

| Major response rate | 45% | Yes (<20%) |

| Median overall survival (OS) | 28.7 months | Yes (<20 months) |

| Median OS of responders | 44.4 months | Yes |

| Median P-F survival | 14.1 months | Yes (<10 months) |

| Median OS in MCL | 9.4 months | Yes (<6 months) |

| Decrease in BM MC burden by=50% | 57% | Yes |

| Decrease in serum tryptase by=50% | 60% | Yes |

| Decrease in spleen volume | 77% | Yes |

Data were obtained from the recently published global midostaurin trial [39].

SM, systemic mastocytosis; MCL, mast cell leukemia; P-F, progression-free; BM MC, bone marrow mast cells.

Table 3. Side-effects observed with midostaurin in a global phase II trial in advanced SMa .

| Reported event | Frequency (%) |

Also known as a classical symptom in (advanced) SM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Grade | grades 3/4 | |||

| Hematologic | ||||

| Anemia ↑b | 63 | 41 | Yes | |

| Neutropenia ↑b | 48 | 24 | Yes | |

| Thrombocytopenia ↑b | 52 | 29 | Yes | |

| Non-hematologic | ||||

| Nausea | 79 | 6 | Yesc | |

| Vomiting | 66 | 6 | Yesc | |

| Diarrhea | 54 | 8 | Yes | |

| Peripheral edema | 34 | 4 | No | |

| Abdominal pain | 28 | 3 | Yes | |

| Fatigue | 28 | 9 | Yes | |

| Pyrexia | 27 | 6 | No | |

| Constipation | 24 | 1 | No | |

| Headache | 23 | 2 | Yes | |

| Back pain | 20 | 2 | Yes | |

| Pruritus | 19 | 3 | Yes | |

| Arthralgia | 17 | 2 | No | |

| Cough | 16 | 1 | No | |

| Dyspnea | 16 | 4 | Yes | |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 16 | 4 | Yes | |

| Nasopharyngitis | 15 | 0 | No | |

| Urinary tract infection | 12 | 2 | No | |

| Dizziness | 11 | 0 | Yes | |

| Epistaxis | 11 | 3 | No | |

| Pleural effusion | 11 | 3 | No | |

| QT-interval prolongation | 10 | 1 | No | |

Data are derived from Gotlib et al. [39] with permission from the Editor.

Worsening (↑) of cytopenia was frequently observed (as sign of clone-eradication and poor stem cell reserve) and often followed by a good response.

Nausea and vomiting are considered to be a result of drug (capsule) formulation rather than produced by midostaurin itself. SM, systemic mastocytosis.

The study also examined potential effects of midostaurin on SM-related (including mediator-induced) symptoms and the quality of life (QOL) [39, 60]. Most commonly reported baseline symptoms, defined by Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS), were lack of energy (86%), feeling drowsy (72%), and difficulty sleeping (60%). During treatment with midostaurin, most of the symptoms improved, and at the time of best response by MSAS, all 32 symptoms decreased, except for nausea and vomiting, the two known side-effects of midostaurin capsules (Figure 2B) [39, 60]. It is also noteworthy that IgE-dependent basophil histamine release rapidly decreased after intake of midostaurin [43]. A remarkable observation was that improvement in mediator-related symptoms and QOL was still observed even when no objective hematologic response was found and the disease relapsed. This is best explained by clinically relevant activity of midostaurin on MC activation, an effect that is separable from the impact of the drug on MC growth and survival, as also predicted from in vitro studies carried out with midostaurin and its metabolites [43]. In fact, both metabolites block IgE-dependent mediator secretion potently, but only one metabolite (CGP62221) blocks the in vitro growth of neoplastic MC whereas the other, accumulating, metabolite (CGP52421) is less effective [43].

Results from other clinical trials, cohorts, and case reports

Historically, the first patient with advanced SM (MCL) who was treated with midostaurin, achieved a major response with resolution of liver function abnormalities and almost complete disappearance of KIT D816V+ circulating neoplastic MC in the peripheral blood [61]. Based on this impressive response and the encouraging in vitro results obtained with the drug, clinical trials with midostaurin were started. The first study, an investigator-initiated trial of 26 patients with advanced SM, documented an organ response rate of 69%, including 50% major responses [62]. Notably, one patient with MCL achieved a complete remission, which included complete resolution of anemia and hypalbuminemia, normalization of a highly elevated tryptase (763 ng/ml), resolution of splenomegaly, and elimination of a huge infiltrate (70%–80%) of neoplastic MC in the BM [62]. This response is of particular interest from a molecular perspective since the patient carried tandem KIT D816V and FLT3 ITD mutants, both therapeutic targets of midostaurin (Table 1). These data provided proof of principle of the activity of midostaurin in advanced SM, and led to the aforementioned global phase II trial of midostaurin. With now more than 9 years of median follow-up, the median overall and progression free-survival of the pilot cohort examined are 40 and 41 months, respectively (J. Gotlib, personal communication).

In a more recent analysis, the response of 28 patients with advanced SM treated with midostaurin on a French compassionate use program was compared with a historical control group of patients with SM treated with other anti-neoplastic drugs, including cladribine [40]. After a median treatment-duration of 10.5 months and a median follow-up of 18.5 months, the overall response rate in the midostaurin group was 71%, including major responses seen in 57% of the cases. After a median treatment-duration of about 10 months, the OS rate was 42.7% in the midostaurin group and thus significantly higher than the OS rate in the control group (14.9%) [40]. Other studies suggest that midostaurin can also reduce the burden of neoplastic MC in the skin in patients with ISM (A. Reiter, H. C. Kluin-Nelemans, and J. Gotlib, unpublished observation).

Furthermore, due to its potent activity against wt KIT, midostaurin should also be able to induce near-complete MC-deficiency in the absence of SM, as has been recently described for imatinib [63]. However, due to the long-maturation time of MC-committed stem- and progenitor cells and the long survival of mature MC in the tissues [64], it may take about 2 years until a strong KIT-inhibitor is able to induce complete MC deficiency [63].

Pharmacologic aspects and impact of midostaurin metabolites

After multiple dosing, a non-linear pharmacokinetic of midostaurin was observed in patients with AML [49–51]. In fact, plasma concentrations of the drug increased during the first week of therapy, followed by a significant decrease, with a plateau being reached after 2–3 weeks [49–51]. It was also found, that during treatment, the following major drug metabolites can be measured in the plasma of these patients: CGP52421 and CGP62221 [49–51]. Whereas the pharmacokinetics of CGP62221 is similar to that of midostaurin, CGP52421 was found to accumulate over time and to reach steady-state concentrations after 1 month [49–52]. The pharmacologic basis of this phenomenon remains unclear, but may be related to cytochrome P450 enzyme induction in the liver. Recent data suggest that CGP62221 and midostaurin are equally effective in inhibiting the growth of neoplastic MC [43]. However, CGP52421 is less effective in inhibiting the growth of HMC-1 cells compared with midostaurin [43]. On the other hand, the metabolite still retains considerable activity against primary neoplastic MC in vitro in most patients with SM [43]. In addition, CGP52421 does not ‘antagonize’ the effects of midostaurin on MC when co-administered in vitro [43]. In addition, CGP52421 blocks IgE-dependent MC activation in the same way as midostaurin [43]. Furthermore, the metabolite cooperates with cladribine (2CdA) in the same way as midostaurin to block MC growth [43]. Finally, the metabolites can be washed out easily by discontinuing the drug for several days. Therefore, the metabolite issue, albeit recognized, may not be a major hurdle in the successful treatment of patients with advanced SM.

Mechanisms of resistance against midostaurin

Although midostaurin is regarded a breakthrough in the treatment of advanced SM, response-duration is variable, and in some patients, no clinical activity is observed. Although the mechanisms for primary or secondary resistance have not been formally elucidated [39, 61], a number of etiologies are discussed. These include: (i) secondary mutations in primary target genes, (ii) additional molecular lesions expressed in driver mutant-positive clones, (iii) selection and expansion of driver-negative sub-clones, (iv) intrinsic stem cell resistance, and (v) pharmacologic resistance.

Secondary mutations have been described in AML patients with FLT3 ITD mutations [65] and patients with PDGFR mutations [66], but not in patients with advanced SM. This may be explained by the low number of patients examined so far, by a low mitotic rate and mutation-rate in KIT-mutated SM-clones or by the fact that the selection pressure of midostaurin is too weak to allow for outgrowth of sub-clones carrying such secondary mutations.

Additional molecular lesions and driver pathways are frequently detected in advanced SM [67–69]. Since KIT D816V may not be a primary defect in SM, such additional lesions and pathways are detectable in both, KIT-mutated sub-clones and ‘KIT-non-mutated’ sub-clones. In other words, midostaurin resistant patients may relapse with a KIT D816V-positive or with a KIT D816V-negative sub-clone or a mixture of such clones. As an example, the first MCL patient successfully treated with midostaurin relapsed a few months after a major initial response, and presented with an AML-like disease without KIT D816V [61]. A number of different mutations may be detected in advanced SM, mostly in the context of an AHN. These include, among others, known pathogenic variants of TET2, SRSF2, ASXL1, CBL, RUNX1, and RAS [67–69]. At least some of these mutations may contribute to resistance against midostaurin. In other SM-AHN patients, additional driver-lesions may be found, such as JAK2 V617F or the AML-associated t(8;21) RUNX1-RUNX1T1 fusion-gene.

Instrinsic resistance of leukemic stem cells (LSC) has been postulated in various malignancies and linked to certain molecules, including multidrug-resistance genes, such as MDR-1, immune-checkpoint receptors, such as PD-L1 (PD1 ligand) or CD47 (‘don’t eat me’ receptor), and interactions between LSC and the so-called stem cell niche. Such mechanisms may also apply in patients with advanced SM. For example, it has been described recently that neoplastic MC display PD-L1 [70]. Moreover, MCL-initiating cells (MCL LSC) have been described to express various niche-related receptors, such as CD44, KIT, and CD47 [71]. Pharmacologic resistance against midostaurin has also been discussed, especially in the context of midostaurin metabolites (see above). However, the clinical impact of pharmacologic resistance in the context of SM remains uncertain. Potential mechanisms of resistance against midostaurin are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Potential mechanisms and strategies to overcome resistance against midostaurin.

| Potential mechanism | Example(s) | Proposed potential strategies to overcome drug resistance |

|---|---|---|

| (A) Molecular (acquired) resistance | ||

| Secondary mutations in critical target/driver genes Expansion of driver target- Negative subclone(s) +/− additional oncogenic drivers trigger growth of neoplastic cells |

FLT3 N676 in AML KIT D816V− Negative relapse |

Switch to other drug, CT+SCT, drug combinations Switch to other drug, CT+SCT Drug combinations employing additional targeted drugs directed against other oncogenic drivers |

| pAXL in AML pBTK in MCL |

||

| (B) Intrinsic LSC resistance | ||

| Niche-related resistance Checkpoint-related resistance Drug-transporter activity |

CXCR4-SDF-1 PD-L1 in MC and AML LSC MDR-1 on LSC |

CXCR4 blockers Checkpoint inhibitors Transporter-targeting drugs |

| (C) Pharmacologic resistance | ||

| Metabolite accumulation | Accumulation of CGP52421 in AML patients |

Cycle-based therapy with in-between wash out periods |

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CT, chemotherapy; SCT, stem cell transplantation; MCL, mast cell leukemia; MC, mast cells; LSC, leukemic stem cells.

Potential strategies aimed at overcoming resistance against midostaurin

A key question in advanced SM is how to avoid and to overcome resistance against midostaurin. One strategy may be to apply combinations of drugs that exert clear synergistic growth-inhibitory effects on neoplastic MC [25, 27, 55–57, 72]. Probably the most encouraging drug combination to be considered is midostaurin + cladribine [25]. Based on in vitro data and clinical responses seen with both agents, this combination should be tested in forthcoming clinical trials in advanced SM.

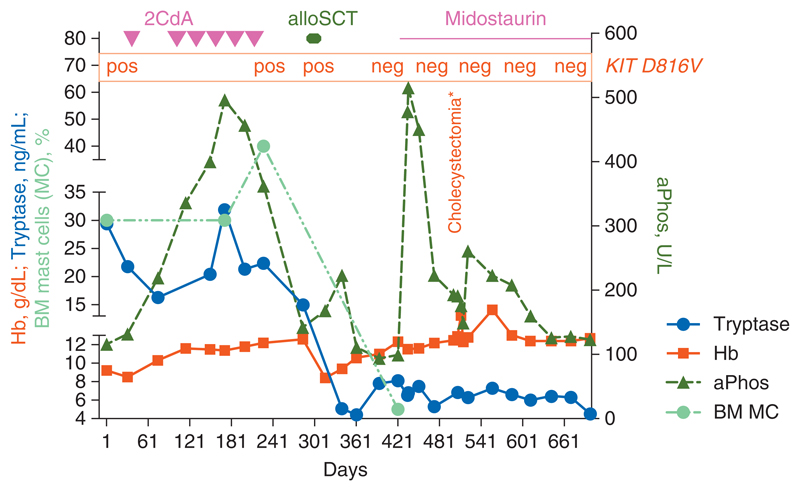

Another potential strategy to overcome resistance may be to apply poly-chemotherapy (CT) and allogeneic SCT. Indeed, it has been shown that SCT is a potentially curative approach in advanced SM, particularly in patients with SM-AHN [21, 73]. One strategy for patients with drug-resistant SM may be to use midostaurin with or without chemotherapy (CT) such as cladribine or multi-agent induction regimens (especially for patients with MCL) as a bridge to SCT. Such debulking strategies may be particularly relevant for rapidly proliferating forms of ASM and MCL. Currently available safety and efficacy data suggest that high-risk hematologic neoplasms such as FLT3-positive AML can be managed effectively with midostaurin in combination with chemotherapy [74]. Another approach would be to use midostaurin after allogeneic SCT as maintenance therapy in order to reduce the risk of relapse. Observations in single case reports suggest that such an approach is feasible and associated with disease-free survival (Figure 3). CT and SCT may also be an optimal way to eradicate neoplastic stem cells in ASM and MCL. However, not all patients are transplantable, mainly because of age and comorbidities. For such elderly and/or comorbid patients, alternative stem-cell eradicating therapies have to be developed. One problem is that these cells are often quiescent and indistinguishable (by phenotype and target-profiles) from normal stem cells. One interesting approach to kill neoplastic stem cells (preferentially) may be to apply targeted antibodies directed against surface structures expressed on disease-initiating and propagating cells in ASM and MCL. Promising surface targets that are expressed not only on neoplastic MC, but also on disease-initiating and -propagating stem cells in ASM and MCL, include CD33, CD44, and CD52 [71, 75, 76]. Table 4 provides a summary of strategies that may be useful for overcoming resistance of neoplastic MC against midostaurin. Another question may be how to address pharmacologic resistance and the accumulation of inactive midostaurin metabolites. One possible way may be to apply the drug in 14- or 21-day cycles, followed by a short wash-out period. Another method to address this form of resistance may be to apply drug combinations. In fact, it has been described that both midostaurin metabolites cooperate with cladribine in inducing growth inhibition of neoplastic MC [43].

Figure 3. Clinical course in a patient with aggressive systemic mastocytosis (ASM).

The patient was diagnosed with ASM with rapid clinical deterioration based on the local destructive growth of mast cells as well as on severe mediator-related symptoms. Initially, the patient's condition did not allow for any intensive therapy. The patient was then treated with cladribine and glucocorticosteroids. After sufficient debulking the general condition improved dramatically, and the patient subsequently underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT). After SCT, the patient had a transient increase in tryptase. Treatment with midostaurin was initiated and resulted in a decrease in tryptase and a complete disappearance of KIT D816V. At the same time, the patient had also developed cholecystitis and a huge (transient) increase in alkaline phosphatase. However, after cholecystectomy, clinical symptoms improved, and the alkaline phosphatase concentration (otherwise also known as a disease-indicator in ASM) decreased to normal levels. After 2 years, the patient has still a major clinical response and is in complete hematologic and molecular remission.

Indications for midostaurin: status 2017 and outlook toward the future

Based on its beneficial effects observed in recent clinical trials [39, 40, 62], midostaurin is regarded as an emerging first-line standard therapy for patients with advanced SM. In addition, midostaurin can be considered standard salvage therapy for SM patients in whom lack or loss of response to IFN-A, cladribine, or other cytoreductive is seen. Additional indications may be based on the effects of the drug on MC activation. For example, patients with ISM or smoldering SM (SSM) with severe mediator-related symptoms unresponsive to conventional antimediator therapy may benefit from midostaurin [77]. In addition, patients with advanced SM who have undergone high-dose CT and/or SCT may benefit from treatment with midostaurin as maintenance therapy (Figure 3). However, thus far, no data from controlled clinical trials are available to support these indications. It also remains unknown whether and what combination treatments involving midostaurin are useful, and what subgroup of patients will optimally benefit. A reasonable approach may be to combine midostaurin with cladribine in patients who develop resistance against cladribine. Other unresolved questions are whether midostaurin can eradicate all neoplastic MC in patients with ISM and whether skin lesions will disappear in all patients. If this is the case, the benefits of midostaurin will need to be weighed against potential side-effects, including long-term toxicities that may not be fully appreciated at this time.

Because of midostaurin’s capacity to block IgE-mediated activation of MC and its ability to improve mediator-related symptoms in SM patients [39, 60], an additional indication worthy of future investigation may be secondary (IgE-dependent) MCAS and IgE-dependent allergies unresponsive to classical antimediator therapy. An important consideration in this regard is that it can take many months until the numbers of (normal) MC decrease substantially in patients treated with a potent KIT inhibitor [63]. The obvious advantage of midostaurin over other KIT inhibitors such as imatinib or masitinib would be that the drug immediately blocks IgE-dependent release of histamine [38, 43]. However, the side-effect profile of the drug should always be carefully considered against potential symtomatic improvements in non-neopleastic conditions. Whether midostaurin indeed works in patients with severe anaphylaxis or secondary MCAS remains to be elucidated in forthcoming clinical trials. A summary of potential future indications of midostaurin is shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Potential indications of midostaurin in applied hematology and immunology.

| Potential indication | Positive results from clinical trials available | Approval from health authorities |

|---|---|---|

| FLT3-mutated AML | + | +a |

| KIT-mutated AML | − | − |

| Advanced SM including MCL | + | +a |

| Smoldering SM (skin lesions, MCAS) | +/− | − |

| Indolent SM (skin lesions, MCAS) | +/− | − |

| Primary MCAS | − | − |

| Secondary (IgE-dependent) MCAS | − | − |

| IgE-dependent atopic diseases | − | − |

| Eosinophilic leukemias | − | − |

| PDGFR-rearranged MPN-eo | − | − |

| Other forms of MPN-eo | − | − |

For these indications midostaurin received approval from the FDA on April 28, 2017.

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; SM, systemic mastocytosis; MCL, mast cell leukemia; MCAS, mast cell activation syndrome; IgE, immunoglobulin E; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; MPN-eo, MPN with hypereosinophilia

Discussion

Concluding remarks

The growth of normal and neoplastic MC is largely dependent on the kinase activity of KIT. The oncogenic KIT variant D816V is detected in most patients with SM and has been implicated as a major driver of MC survival and oncogenesis. As a result, KIT is an obvious target of therapy in advanced SM. Midostaurin is a multi-targeted drug that blocks not only the oncogenic variants of KIT and various KIT-downstream kinase targets, but also IgE-dependent secretion of histamine from MC and basophils. In first clinical trials, these effects have been confirmed and major clinical responses were seen with midostaurin in advanced SM. The next steps will be to explore the clinical efficacy of drug combinations in advanced SM and the potential value of midostaurin as monotherapy in patients with indolent or smoldering SM suffering from severe mediator-related symptoms (MCAS). Based on its broad target spectrum, its documented efficacy in advanced SM and FLT3-mutated AML, and its favorable toxicity profile, midostaurin is expected to become a broadly used agent in clinical hematology once it has been adopted in clinical practice. In the USA, midostaurin (RydaptVR ; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.) was approved for the treatment of advanced SM and FLT3-positive AML by the FDA on April 28, 2017.

Acknowledgement

We thank Emir Hadzijusufovic for excellent technical assistance.

Funding

Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (grant F4704-B20) to PV; Charles and Ann Johnson Foundation (no grant numbers apply) to JG.

Footnotes

Disclosure

PWM is employed by Novartis, Switzerland; PV, KH, TIG, KS, HCK-N, H-PH, AR, and JG served as Scientific Advisory Board Members and as Consultants in a global phase II Novartis trial exploring the effects of midostaurin in advanced SM. PV, KH, TIG, KS, WRS, OH, HCK-N, H-PH, AR, and JG received honoraria from Novartis. The authors have declared no other conflicts of interest in this project.

References

- 1.Lennert K, Parwaresch MR. Mast cells and mast cell neoplasia: a review. Histopathology. 1979;3:349–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1979.tb03017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metcalfe DD. The liver, spleen, and lymph nodes in mastocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96(3S):45S–46S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horny HP, Valent P. Diagnosis of mastocytosis: general histopathological aspects, morphological criteria, and immunohistochemical findings. Leuk Res. 2001;25:543–551. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metcalfe DD. Classification and diagnosis of mastocytosis: current status. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:2S–4S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of systemic mastocytosis: state of the art. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:695–717. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akin C, Metcalfe DD. Systemic mastocytosis. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:419–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arock M, Valent P. Pathogenesis, classification and treatment of mastocytosis: state of the art in 2010 and future perspectives. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3:497–516. doi: 10.1586/ehm.10.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valent P, Horny HP, Escribano L, et al. Diagnostic criteria and classification of mastocytosis: a consensus proposal. Leuk Res. 2001;25:603–625. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, et al. Aggressive systemic mastocytosis and related mast cell disorders: current treatment options and proposed response criteria. Leuk Res. 2003;27:635–641. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valent P, Akin C, Escribano L, et al. Standards and standardization in mastocytosis: consensus statements on diagnostics, treatment recommendations and response criteria. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:435–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escribano L, Akin C, Castells M, et al. Mastocytosis: current concepts in diagnosis and treatment. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:677–690. doi: 10.1007/s00277-002-0575-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brockow K, Jofer C, Behrendt H, Ring J. Anaphylaxis in patients with mastocytosis: a study on history, clinical features and risk factors in 120 patients. Allergy. 2008;63:226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theoharides TC, Valent P, Akin C. Mast cells, mastocytosis, and related disorders. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:163–172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1409760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valent P, Sperr WR, Schwartz LB, Horny HP. Diagnosis and classification of mast cell proliferative disorders: delineation from immunologic diseases and non-mast cell hematopoietic neoplasms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim KH, Tefferi A, Lasho TL, et al. Systemic mastocytosis in 342 consecutive adults: survival studies and prognostic factors. Blood. 2009;113:5727–5736. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pardanani A, Lim KH, Lasho TL, et al. Prognostically relevant breakdown of 123 patients with systemic mastocytosis associated with other myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2009;114:3769–3772. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Travis WD, Li CY, Hoagland HC, et al. Mast cell leukemia: report of a case and review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc. 1986;61:957–966. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kluin-Nelemans HC, Oldhoff JM, Van Doormaal JJ, et al. Cladribine therapy for systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2003;102:4270–4276. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim KH, Pardanani A, Butterfield JH, et al. Cytoreductive therapy in 108 adults with systemic mastocytosis: outcome analysis and response prediction during treatment with interferon-alpha, hydroxyurea, imatinib mesylate or 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:790–794. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barete S, Lortholary O, Damaj G, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of cladribine (2-CdA) in adult patients with mastocytosis. Blood. 2015;126:1009–1016. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-614743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ustun C, Reiter A, Scott BL, et al. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for advanced systemic mastocytosis. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3264–3274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tefferi A, Verstovsek S, Pardanani A. How we diagnose and treat WHO-defined systemic mastocytosis in adults. Haematologica. 2008;93:6–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valent P, Sperr WR, Akin C. How I treat patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:5812–5817. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-292144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valent P, Ghannadan M, Akin C, et al. On the way to targeted therapy of mast cell neoplasms: identification of molecular targets in neoplastic mast cells and evaluation of arising treatment concepts. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:S41–S52. doi: 10.1111/j.0960-135X.2004.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gleixner KV, Mayerhofer M, Aichberger KJ, et al. PKC412 inhibits in vitro growth of neoplastic human mast cells expressing the D816V-mutated variant of KIT: comparison with AMN107, imatinib, and cladribine (2CdA) and evaluation of cooperative drug effects. Blood. 2006;107:752–759. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah NP, Lee FY, Luo R, et al. Dasatinib (BMS-354825) inhibits KITD816V, an imatinib-resistant activating mutation that triggers neoplastic growth in most patients with systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2006;108:286–291. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gleixner KV, Mayerhofer M, Sonneck K, et al. Synergistic growth-inhibitory effects of two tyrosine kinase inhibitors, dasatinib and PKC412, on neoplastic mast cells expressing the D816V-mutated oncogenic variant of KIT. Haematologica. 2007;92:1451–1459. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagata H, Worobec AS, Oh CK, et al. Identification of a point mutation in the catalytic domain of the protooncogene c-kit in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients who have mastocytosis with an associated hematologic disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10560–10564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Longley BJ, Tyrrell L, Lu SZ, et al. Somatic c-KIT activating mutation in urticaria pigmentosa and aggressive mastocytosis: establishment of clonality in a human mast cell neoplasm. Nat Genet. 1996;12:312–314. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fritsche-Polanz R, Jordan JH, Feix A, et al. Mutation analysis of C-KIT in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes without mastocytosis and cases of systemic mastocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2001;113:357–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Féger F, Ribadeau Dumas A, Leriche L, et al. Kit and c-kit mutations in mastocytosis: a short overview with special reference to novel molecular and diagnostic concepts. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;127:110–114. doi: 10.1159/000048179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arock M, Sotlar K, Akin C, et al. KIT mutation analysis in mast cell neoplasms: recommendations of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis. Leukemia. 2015;29:1223–1232. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furitsu T, Tsujimura T, Tono T, et al. Identification of mutations in the coding sequence of the proto-oncogene c-kit in a human mast cell leukemia cell line causing ligand-independent activation of c-kit product. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1736–1744. doi: 10.1172/JCI116761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akin C, Brockow K, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 on human mast cells bearing wild-type or mutated c-kit. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:686–692. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Growney JD, Clark JJ, Adelsperger J, et al. Activation mutations of human c-KIT resistant to imatinib mesylate are sensitive to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKC412. Blood. 2005;106:721–724. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ustun C, DeRemer DL, Akin C. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of systemic mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2011;35:1143–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fabbro D, Ruetz S, Bodis S, et al. PKC412 – a protein kinase inhibitor with a broad therapeutic potential. Anticancer Drug Des. 2000;15:17–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krauth MT, Mirkina I, Herrmann H, et al. Midostaurin (PKC412) inhibits immunoglobulin E-dependent activation and mediator release in human blood basophils and mast cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1711–1720. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gotlib J, Kluin-Nelemans HC, George TI, et al. Efficacy and safety of midostaurin in advanced systemic mastocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2530–2541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chandesris MO, Damaj G, Canioni D, et al. Midostaurin in advanced systemic mastocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2605–2607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1515403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamaoki T, Nomoto H, Takahashi I, et al. Staurosporine, a potent inhibitor of phospholipid/Ca++dependent protein kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;135:397–402. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karaman MW, Herrgard S, Treiber DK, et al. A quantitative analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:127–132. doi: 10.1038/nbt1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peter B, Winter GE, Blatt K, et al. Target interaction profiling of midostaurin and its metabolites in neoplastic mast cells predicts distinct effects on activation and growth. Leukemia. 2016;30:464–472. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cools J, Stover EH, Boulton CL, et al. PKC412 overcomes resistance to imatinib in a murine model of FIP1L1-PDGFRα-induced myeloproliferative disease. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:459–469. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weisberg E, Wright RD, Jiang J, et al. Effects of PKC412, nilotinib, and imatinib against GIST-associated PDGFRA mutants with differential imatinib sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1734–1742. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Bubnoff N, Engh RA, Aberg E, et al. FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3-internal tandem duplication tyrosine kinase inhibitors display a nonoverlapping profile of resistance mutations in vitro. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3032–3041. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nadler MJ, Matthews SA, Turner H, Kinet JP. Signal transduction by the high-affinity immunoglobulin E receptor Fc epsilon RI: coupling form to function. Adv Immunol. 2000;76:325–355. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)76022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siraganian RP, Zhang J, Suzuki K, Sada K. Protein tyrosine kinase Syk in mast cell signaling. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:1229–1233. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Propper DJ, McDonald AC, Man A, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of PKC412, an inhibitor of protein kinase C. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1485–1492. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levis M, Brown P, Smith BD, et al. Plasma inhibitory activity (PIA): a pharmacodynamic assay reveals insights into the basis for cytotoxic response to FLT3 inhibitors. Blood. 2006;108:3477–3483. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Yin OQ, Graf P, et al. Dose- and time-dependent pharmacokinetics of midostaurin in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48:763–775. doi: 10.1177/0091270008318006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dutreix C, Munarini F, Lorenzo S, et al. Investigation into CYP3A4-mediated drug-drug interactions on midostaurin in healthy volunteers. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;72:1223–1234. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2287-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saleh R, Wedeh G, Herrmann H, et al. A new human mast cell line expressing a functional IgE receptor converts to tumorigenic growth by KIT D816V transfection. Blood. 2014;124:111–120. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-534685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aichberger KJ, Gleixner KV, Mirkina I, et al. Identification of proapoptotic Bim as a tumor suppressor in neoplastic mast cells: role of KIT D816V and effects of various targeted drugs. Blood. 2009;114:5342–5351. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-175190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gleixner KV, Peter B, Blatt K, et al. Synergistic growth-inhibitory effects of ponatinib and midostaurin (PKC412) on neoplastic mast cells carrying KIT D816V. Haematologica. 2013;98:1450–1457. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.079202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wedeh G, Cerny-Reiterer S, Eisenwort G, et al. Identification of bromodomain-containing protein-4 as a novel marker and epigenetic target in mast cell leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29:2230–2237. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peter B, Cerny-Reiterer S, Hadzijusufovic E, et al. The pan-Bcl-2 blocker obatoclax promotes the expression of Puma, Noxa, and Bim mRNA and induces apoptosis in neoplastic mast cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95:95–104. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1112609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gleixner KV, Mayerhofer M, Cerny-Reiterer S, et al. KIT-D816V-independent oncogenic signaling in neoplastic cells in systemic mastocytosis: role of Lyn and Btk activation and disruption by dasatinib and bosutinib. Blood. 2011;118:1885–1898. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kneidinger M, Schmidt U, Rix U, et al. The effects of dasatinib on IgE receptor-dependent activation and histamine release in human basophils. Blood. 2008;111:3097–3107. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-104372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gotlib J, et al. Durable responses and improved quality of life with midostaurin (PKC412) in advanced systemic mastocytosis (SM): updated stage 1 results of the global D2201 trial. Blood. 2013;122:106. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gotlib J, et al. Activity of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKC412 in a patient with mast cell leukemia with the D816V KIT mutation. Blood. 2005;106:2865–2870. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gotlib J, et al. KIT inhibitor midostaurin exhibits a high rate of clinically meaningful and durable responses in advanced systemic mastocytosis: report of a fully accrued phase II trial. Blood. 2010;116:316. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cerny-Reiterer S, Rabenhorst A, Stefanzl G, et al. Long-term treatment with imatinib results in profound mast cell deficiency in Ph+ chronic myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2015;6:3071–3084. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Födinger M, Fritsch G, Winkler K, et al. Origin of human mast cells: development from transplanted hematopoietic stem cells after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1994;84:2954–2959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heidel F, Solem FK, Breitenbuecher F, et al. Clinical resistance to the kinase inhibitor PKC412 in acute myeloid leukemia by mutation of Asn-676 in the FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain. Blood. 2006;107:293–300. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lierman E, Michaux L, Beullens E, et al. FIP1L1-PDGFRalpha D842V, a novel panresistant mutant, emerging after treatment of FIP1L1-PDGFRalpha T674I eosinophilic leukemia with single agent sorafenib. Leukemia. 2009;23:845–851. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Traina F, Visconte V, Jankowska AM, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism array lesions, TET2, DNMT3A, ASXL1 and CBL mutations are present in systemic mastocytosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson TM, Maric I, Simakova O, et al. Clonal analysis of NRAS activating mutations in KIT-D816V systemic mastocytosis. Haematologica. 2011;96:459–463. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.031690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwaab J, Schnittger S, Sotlar K, et al. Comprehensive mutational profiling in advanced systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2013;122:2460–2466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-496448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rabenhorst A, Leja S, Schwaab J, et al. Expression of programmed cell death ligand-1 in mastocytosis correlates with disease severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eisenwort G, et al. Identification of a neoplastic stem cell in human mast cell leukemia. Blood. 2014;124:817. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gotlib J. KIT mutations in mastocytosis and their potential as therapeutic targets. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26:575–592. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ustun C, Gotlib J, Popat U, et al. Consensus opinion on allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in advanced systemic mastocytosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:1348–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stone RM, et al. The multi-kinase inhibitor midostaurin prolongs survival compared with placebo in combination with daunorubicin/cytarabine induction, high-dose consolidation, and as maintenance therapy in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients age 18-60 with FLT3 mutations: an international prospective randomized placebo-controlled double-blind trial (CALGB 10603/RATIFY) Blood. 2015;126:6. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krauth MT, Böhm A, Agis H, et al. Effects of the CD33-targeted drug gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) on growth and mediator secretion in human mast cells and blood basophils. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hoermann G, Blatt K, Greiner G, et al. CD52 is a molecular target in advanced systemic mastocytosis. FASEB J. 2014;28:3540–3551. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-250894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van Anrooij B, Oude Elberink JNG, Span LF, et al. Midostaurin (PKC412) in indolent systemic mastocytosis: a phase 2 trial. EHA Learning Center. 2016 Abstract P303. [Google Scholar]