Abstract

The biogenesis of transmembrane β-barrels (outer membrane proteins, or OMPs) is an elaborate multistep orchestration of the nascent polypeptide with translocases, barrel assembly machinery, and helper chaperone proteins. Several theories exist that describe the mechanism of chaperone-assisted OMP assembly in vivo and unassisted (spontaneous) folding in vitro. Structurally, OMPs of bacterial origin possess even-numbered strands, while mitochondrial β-barrels are even- and odd-stranded. Several underlying similarities between prokaryotic and eukaryotic β-barrels and their folding machinery are known; yet, the link in their evolutionary origin is unclear. While OMPs exhibit diversity in sequence and function, they share similar biophysical attributes and structure. Similarly, it is important to understand the intricate OMP assembly mechanism, particularly in eukaryotic β-barrels that have evolved to perform more complex functions. Here, we deliberate known facets of β-barrel evolution, folding, and stability, and attempt to highlight outstanding questions in β-barrel biogenesis and proteostasis.

Keywords: Barrel assembly machinery, Assisted folding, OMP, Biogenesis, Mitochondrial outer membrane proteins, Energetics, Kinetic control

1. Introduction

Proteins form the workforce of any cell. Cytosolic proteins constitute a vast majority of well-characterized proteins; in contrast, integral membrane proteins represent the least characterized biomolecules, although they account for 30% of the cellular proteome. Functionally, membrane proteins are cellular gatekeepers, and are involved directly or indirectly in all cellular functions. Hence, they remain molecules of immense interest. Integral membrane proteins exists as α-helices (and helical bundles) or β-barrels. Single- and multi-pass helical membrane proteins are ubiquitous in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic membranes, whereas transmembrane β-barrels are almost exclusively localized in the outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria, as well as mitochondria and chloroplasts, by virtue of their endosymbiotic evolution. In Gram-negative bacteria, β-barrels of the bacterial outer membrane, also called outer membrane proteins (OMPs), are involved in a repertoire of functions that include serving as the cell's first line of defense, maintaining structural integrity of the membrane, host cell adhesion and invasion, lipopolysaccharide modification, anchoring, and metabolite transport [1–3]. Several bacterial toxins also exist as transmembrane β-barrels. We can trace the ancestral lineage of several mitochondrial and chloroplast β-barrels to Gram-negative bacteria. In this review, we discuss the evolution, biogenesis, and energetics of bacterial OMPs and compare them with their eukaryotic counterparts. We attempt to identify compelling caveats of the in vitro studies and present outstanding questions in membrane protein proteostasis.

2. Evolution and design of transmembrane β-barrels

2.1. Divergent evolution of barrel sequences?

The transmembrane segments of membrane proteins have two restricted folds, suggesting that significant changes in the parent sequence have resulted in multi-functional proteins. The evolution of protein structures and function can be both convergent and divergent. OMPs were believed to arise from divergent evolution, wherein gene duplication of a single β-hairpin unit [4] gave rise to similar structural scaffolds with diverse functions (Fig. 1). It is conceivable that four such repeating units can meet the minimum requirement for complete barrel formation through inter-strand hydrogen bonding. Not surprisingly, many OMPs including OmpA, OmpX, and PagP possess the 8-stranded structure. A study which showed that duplication of the OmpX gene product gave rise to a 16-stranded β-barrel also supported gene duplication as a means of β-barrel evolution [5]. However, whether OMP scaffold evolution can be accounted for solely by gene duplication, and whether other mechanisms of OMP evolution exist, remains to be established. Larger barrels with up to 26 β-strands (LptD; [6]) have been characterized. These proteins carry out functions that include the transport of metabolites (BtuB; [7]), efflux pumps (OprM; [8]) or proteins. For example, PapC belongs to a class of proteins called as ushers. It is responsible for the translocation of the pilin protein through its 24-stranded β-barrel pore [9].

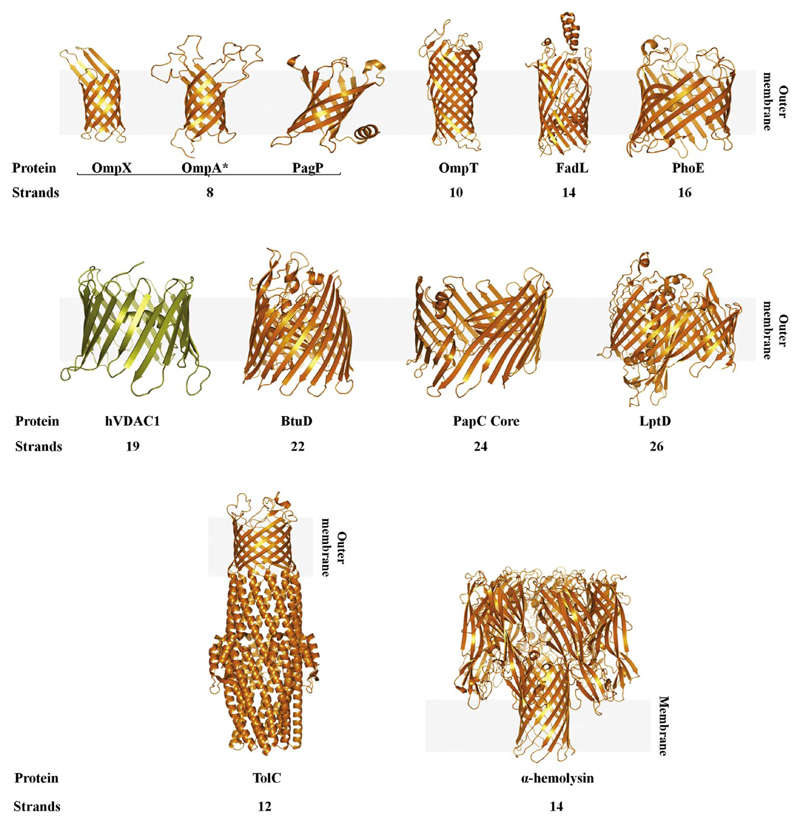

Fig. 1.

Structures of transmembrane β-barrels. Cartoon presentation of representative transmembrane β-barrels highlighting their different sizes from the smallest (8-stranded barrels) to the largest barrel known so far (26-stranded LptD). Protein names and the number of β-strands is presented below each structure. All the bacterial β-barrels are colored in gold, and the mitochondrial barrel (VDAC) is in olive. The third panel consists of unique proteins that form a single transmembrane barrel after oligomerization. All structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB; www.rcsb.org/pdb) and rendered using PyMOL [160].

Transmembrane β-barrels exist as monomers, and some are known to oligomerize; but there are a few examples where the oligomerization process in itself is very interesting. We briefly discuss two such examples: TolC and α-hemolysin. TolC is a trimer that forms a single β-barrel (Fig. 1). It is highly conserved in Gram-negative bacteria and aids in the efflux of bacterial proteins or toxins. It is thus the major cause of multidrug resistance seen in bacteria [10]. Another unique class of proteins is hemolysin. α-Hemolysin from Staphylococcus aureus serves as an excellent example to study membrane insertion of a soluble protein. It binds to the host membrane, oligomerizes, and forms a membrane-embedded heptameric pore (Fig. 1), which ultimately lead to host cell lysis [11].

Although exceptions exist, most OMPs possess an even number of strands (Fig. 1). OMP function and stand shear number are, however, decided by the OMP sequence. For example, E. coli OmpX (implicated in complement binding [12]; dispensable for bacterial survival) and Yersinia pestis Ail (binds fibronectin and heparin; important for host cell invasion and pathogenesis [13]) share considerable structural identity (root mean square deviation of 1.7 Å for the Cα atoms of both crystal structures [13]), but only < 45% sequence identity (~60% sequence identity in the transmembrane region). In bacterial OMPs, sequence diversity also appears to be more prominent towards the N-terminal strands than the C-terminal segments. At the C-terminus, a conserved β-signal is known to play a role in folding bacterial OMPs [14,15].

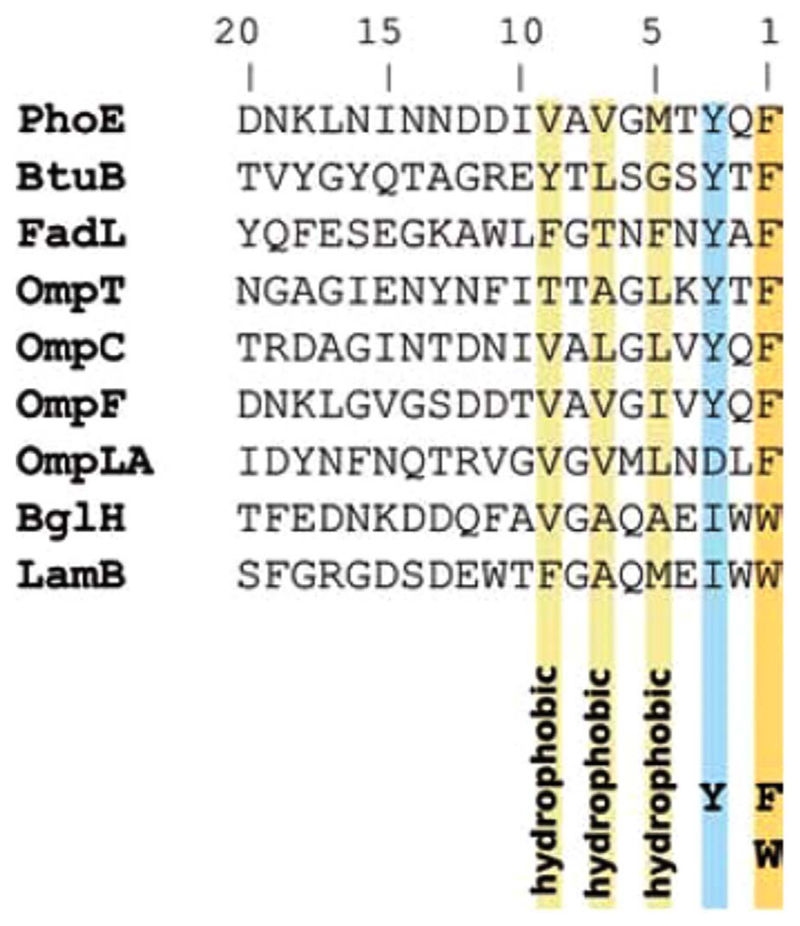

A conserved sequence motif called the β-signal is found at the C-terminus of many OMPs, which bears the consensus pattern aromatic (hydrophobic) – polar – aromatic (Aro-Xaa-Aro) (Fig. 2) [16,17]. Periplasmic holdases and the folding machinery are believed to recognize the β-signal in the nascent OMP [14,18]. The degradation complex in the periplasm may also use the Aro-Xaa-Aro motif as a recognition element to process misfolded OMPs [19]. Interestingly, deletion of the terminal residue hinders, but does not completely stop signal recognition in vitro [15]. Studies on PhoE mutants that lacked the C-terminal Phe of the β-signal showed that these proteins could be incorporated in the bacterial membrane, but with compromised folding efficiency and stability [14,16]. These findings suggest the presence of other recognition sequences in the unfolded OMP, also explaining why exceptions to the presence of the conserved β-signal motif are also prevalent [18]. Species–dependent specificity for the β-signal motif has been observed in bacterial OMPs [18,19]. Mitochondrial outer membrane β-barrels also possess a motif similar to the β-signal that is located towards the C-terminal end of the protein sequence [20]. Based on the observation that the C-terminal residues are important for OMP biogenesis, it is likely that OMPs are assembled in vivo from the C- to the N-terminus; there is no experimental evidence yet to support this hypothesis.

Fig. 2.

Conserved β-signal sequence in OMPs from Gram-negative bacteria. Multiple sequence alignment of the last 20 amino acid residues from representative transmembrane β-barrels of Gram-negative bacteria highlights the C-terminal Aro-Xaa-Aro motif which is conserved across all these barrels. This figure is reproduced with permission from Ref. [17].

2.2. Structural design and stability of β-barrels

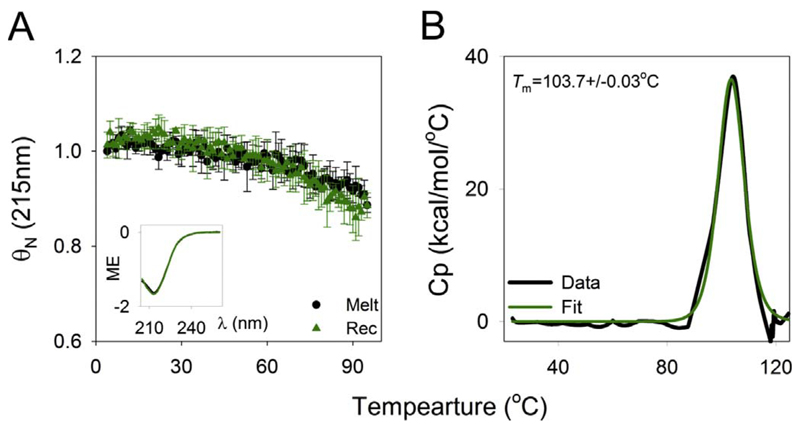

The structural features of transmembrane β-barrels have been addressed previously by Schulz [21]. Hydrophobic (lipid-facing) and hydrophilic or small polar (protein-facing) residues run alternately throughout the transmembrane region of the strand [3]. The major stabilizing factor is the extensive inter-strand hydrogen bonding in the non-polar lipid bilayer [22]. Another striking feature of a transmembrane β-barrel is the existence of aromatic residues at the water-bilayer interface, which anchor the barrel to the bilayer by forming interactions with the polar lipid headgroup and the hydrophobic tail [23,24]. These interactions result in highly stable transmembrane β-barrels, which do not easily unfold. The unusually high stability of OMPs is reflected in their high thermodynamic stability (in vitro estimates of folding free energy values ranging from − 18 to − 32 kcal mol−1; discussed in Section 7.1), resistance to unfolding by chemical denaturants including guanidine hydrochloride [25] and thermal denaturation even in detergent micelles (Fig. 3). For example, E. coli OmpX exhibits an unfolding mid-point temperature of > 100 °C (Fig. 3) [26]; similarly, E. coli PagP is also highly thermostable [27,28].

Fig. 3.

Folded OMPs exhibit high stability. Representative thermal denaturation profiles of E. coli OmpX monitored using circular dichroism (left) and microcalorimetry (right) highlighting the high thermal stability exhibited by this barrel in its folded state. Figure reproduced with permission from Ref. [26].

The recycling of OMPs is not clearly established, but they are known to be degraded in the periplasmic space or removed as outer membrane vesicles (OMVs). The formation of OMVs, though know from a long time, is now increasingly accepted as a strategy that a bacterium might employ to remove old OMPs from their system. The process of production of OMVs occurs by pinching or budding off of the outer membrane. A bacterium produces OMVs for pathogenesis, quorum sensing and other intercellular interactions [29]. The exact mediator or the force behind this process is not clearly understood but studies suggest that it is stress induced, and the turgor pressure built up due to accumulation of misfolded proteins in the outer membrane could be the reason for OMV formation [30]. Recent reports also suggest that lipids play an important role in OMP turnover [31]. Further, OMPs in the bacterial outer membrane are differentially segregated; old OMPs with their folding machinery segregate towards the poles of the growing cells [32], which are likely to be pinched off as OMVs. This also ensures that after subsequent divisions, the new daughter cells are largely devoid of old OMPs.

The three most abundant (and known) mitochondrial OMPs are Sam50, Tom40, and VDACs (voltage-dependent anion channels). Sam50 is a 16-stranded β-barrel that is structurally homologous to Omp85 in bacteria. Tom40 and VDAC are structurally distinct from the bacterial OMPs in that both barrels are 19-stranded structures (Fig. 1). They are believed to have similar structure and evolutionary origin, but have assimilated substantial sequence diversity as they evolved further in higher organisms [33]. The VDAC barrels themselves possess three isoforms (also referred to as paralogs [34,35] due to their diverse functions). VDAC isoforms 1 and 2 evolved from VDAC3 through recombination events and transposon mutagenesis. All three isoforms exhibit ~70% sequence identity, and in addition to transporting metabolites across the mitochondrial outer membrane, these barrels are known to have distinct auxiliary functions and interactomes within the cell [34,35]. Another important protein which is thought to be the component of SAM complex is Mdm10 (mitochondrial distribution and morphology protein 10) [36,37]. Studies show that it helps in the release of unfolded OMPs from the SAM complex [36,38]. Other reports indicate that Mdm10 helps in the later stages of the assembly of TOM complex [36,39]. Mdm10 is also an essential component of endoplasmic reticulum mitochondria encounter structure (ERMES) that connects the ER to mitochondria, and is the site for the exchange of phospholipids and calcium between the two organelles [40]. The OMPs seen in mitochondria are also present in the chloroplast membrane. The outer envelope of chloroplast possesses Toc75-V, which is similar to Sam50 of mitochondria. It additionally possesses Toc75-III, a homolog of Toc75-V involved in preprotein import [41–43].

3. Bacterial machinery for transmembrane β-barrel folding

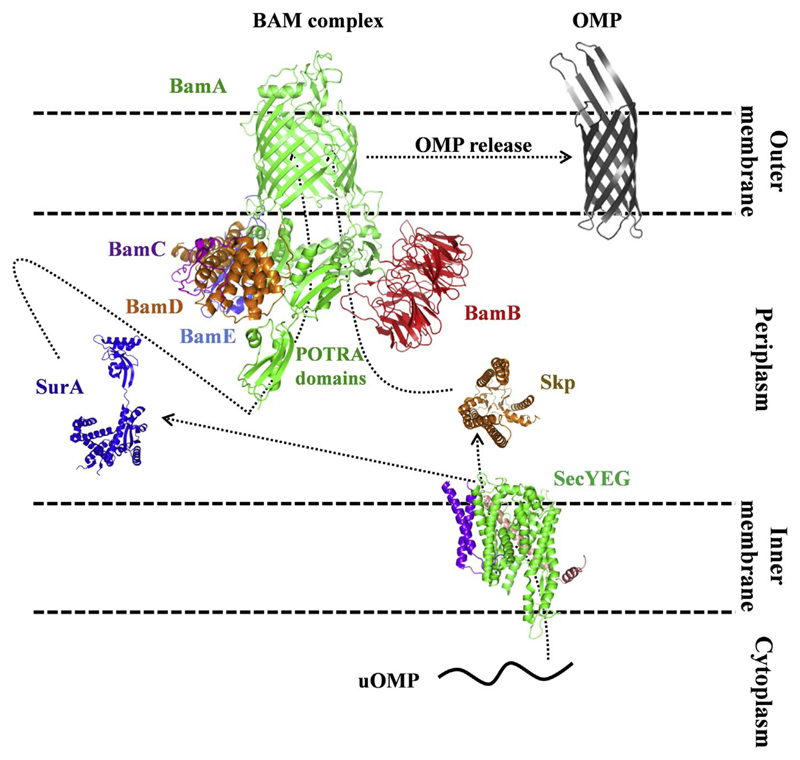

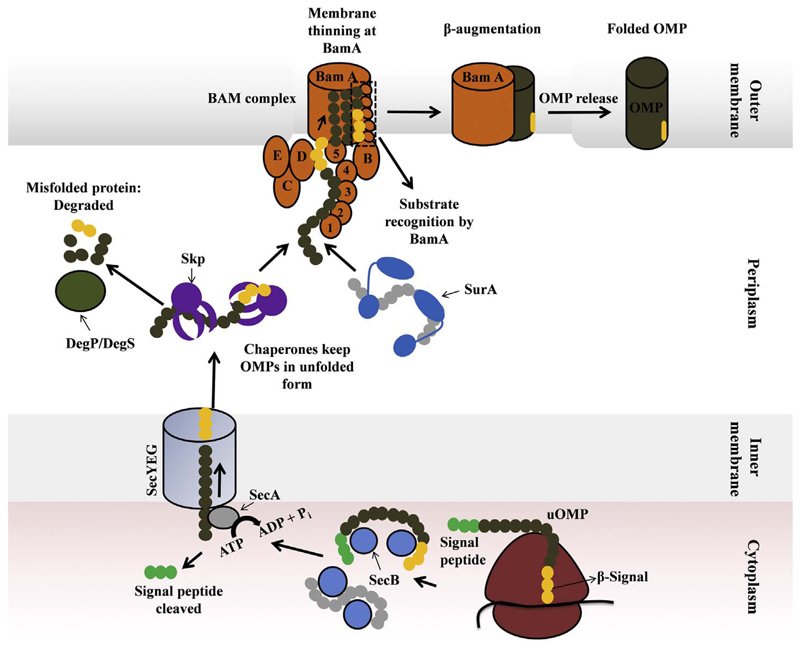

Bacterial OMP biogenesis starts in the cytosol. OMPs are synthesized with a removable N-terminal signal peptide that directs them to the bacterial inner membrane. From here, the OMPs are translocated across the membrane via the Sec translocon system into the periplasm, with simultaneous removal of the N-terminal signal sequence. Complete translocation and signal peptide processing thereby releases the OMPs from the inner membrane. The released OMPs are then transported across the periplasmic space to the assembly machinery in the outer membrane either through the SurA pathway or the Skp/DegP pathway [44,45]. Overall, four groups of proteins mediate the process of OMP biogenesis in bacteria, namely, the translocon, periplasmic chaperones, proteases and the assembly machinery (Fig. 4). These are described in the order they encounter the nascent OMP as the transport and folding proceeds.

Fig. 4.

Components involved in the biogenesis of transmembrane β-barrels in Gram-negative bacteria. Cartoon representation of the crystal structures of the major players involved in OMP biogenesis in the bacterial outer membrane. These include (i) the SecYEG translocon (PDB ID 5CH4) in the inner membrane (green, purple, pink), (ii) periplasmic proteins Skp (PDB ID 1U2M; gold) and SurA (PDB ID 1M5Y; dark blue), (iii) the BAM complex (PDB ID 5AYW) in the outer membrane (BamA, green; and the four lipoproteins: BamB, red; BamC, purple; BamD, gold; BamE, blue). BamA is further made up of five N-terminal extra-membrane POTRA domains located in the periplasm, and the transmembrane region is formed by the C-terminal 16-stranded β-barrel domain. The folded OMP (shown here is the folded OmpX barrel; PDB ID 1QJ8) is in dark grey. DegP is omitted from this schematic. All structures were obtained from the PDB and were rendered using PyMOL. The path traveled by the unfolded OMP (nascent protein; uOMP) is indicated as dotted lines with arrowheads.

3.1. Sec translocon machinery

Transmembrane β-barrels are synthesized in the cytoplasm with an N-terminal signal sequence. This signal sequence is recognized by the SecYEG complex, which is also responsible for the translocation–coupled assembly of transmembrane helical proteins in the inner membrane. The precise mechanism how SecYEG transports the polypeptide is unclear, but this process is ATP dependent (reviewed in detailed in [46]). Briefly, SecB (a cytosolic chaperone) delivers the unfolded OMP to the SecYEG complex. SecB binds to the nascent protein before the signal peptide is cleaved, thereby preventing premature folding of the polypeptide before translocation and unfolded OMP aggregation in the cytoplasm [47]. Once translocated across the inner membrane, the unfolded OMP (now without the signal sequence) is bound competitively by the periplasmic chaperones Skp and SurA.

The SecYEG complex is made of three proteins, SecY, SecE, and SecG. It is responsible for the import of the unfolded OMP from the cytosol to the periplasmic space, where the polypeptide is handed over to the holdases. SecYEG cannot function independently and uses ancillary proteins to mediate OMP translocation. One such important ancillary protein is SecA. SecA is an ATPase that interacts with SecY protein of the translocation complex. The SecB-OMP complex thus formed further interacts with SecA [46], as the translocation process is energy-dependent. Recent reports suggest that Sec translocon functions through a ratchet mechanism where ATP binding and its hydrolysis guides the movement of the nascent protein through the SecYEG translocon [48]. The SecYEG complex in eukaryotes is referred to as Sec61αβγ; this is discussed later in Section 4.1.

3.2. Holdases and chaperones

The processes that occur in the intermembrane space and outer membrane are energy independent, spontaneous, and thermodynamically favored [25]. Skp and SurA are the major periplasmic chaperones that help in OMP biogenesis, maintain the unfolded OMP in a protected unfolded state and prevent OMP misfolding [49,50]. Skp (17 kDa protein) is a trimeric multivalent chaperone which sequesters the unfolded OMP in its hydrophobic cavity, stabilizes the unfolded state, and prevents misfolding and aggregation of the nascent polypeptide [51]. Recent reports on Skp suggest that the flexibility in the structure allows Skp to bind to substrates of various sizes [52]. Binding within the Skp cavity prevents over-stabilization of the non-native structure and thus helps in substrate release when required [53].

surA (survival A) was first identified as a gene required by bacteria for survival during the stationary phase [54]. SurA also has a general chaperone activity, and mutants lacking SurA show decreased levels of OMPs in the membrane [49]. Skp mutants do not exhibit such reduction in OMP levels, suggesting a possible preference of SurA over Skp as a commonly used chaperone [49]. However, more recent measurements of competitive binding kinetics between Skp and SurA for the substrate OMP suggest that Skp preferentially sequesters the unfolded OMP from SecYEG [52].

3.3. Proteases

The third member among periplasmic chaperones is DegP, which is an established protease [55–57] and is also known to function as a chaperone [49]. DegS is another protease and is known to sense the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the periplasm [58,59]. It has also been known to recognize the β-signal motif of the outer membrane proteins when they are overproduced or misfolded in the periplasm. Here, DegS initiates a cascade reaction, which ultimately causes the production of chaperones or proteases [60,61].

Studies show that both the SurA and Skp/DegP pathways function in parallel and that cell will survive when either pathway is missing. The SurA pathway is believed to play an important role under normal conditions and the Skp/DegP pathway is more significant when the cells are under stress [17,49,50]. Irrespective of the pathway, all unfolded OMPs reach the outer membrane or are degraded.

3.4. Barrel assembly machinery (BAM) complex

The final and the key player in OMP assembly is the BAM complex [17,62,63]. It is responsible for the final insertion and folding of transmembrane β-barrels in the outer membrane. It comprises of one transmembrane protein BamA and four lipoproteins BamB, C, D, and E, which are anchored to the inner leaflet of the outer membrane [64,65]. The structures of the BAM complex have been explored in great detail [66–71]. BamA (Omp85) is the central component of the complex, with five POTRA (polypeptide transport-associated) domains at its N-terminus, and a C-terminal transmembrane domain that adopts a 16-stranded β-barrel scaffold (Fig. 5) [66,72,73].

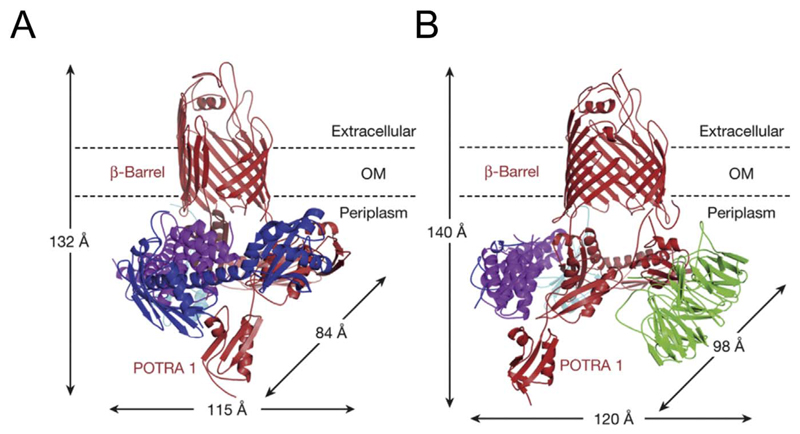

Fig. 5.

Two states of the BAM complex. (A) The transmembrane region of BamA exhibits lateral opening between strands 1 and 16 (PDB ID 5D0Q).The closed state is shown in (B) (PDB ID 5D0O). BamA (red), BamB (green), BamC (blue), BamD (magenta), BamE (cyan). Note that the open state was crystallized without BamB. This figure is reproduced with permission from Ref [72].

Deletion mutants of the POTRA domain suggest that POTRA5 is required for BamA function; interestingly, however, BamA itself is assembled in its absence [74]. Of the four accessory lipoproteins, BamB and BamE are not essential for cell viability; however, nascent OMP assembly is significantly reduced or is defective in their absence [75,76]. Notably, Neisseria does not code for BamB [77,78]. The role of BamC in the BAM complex is not clearly established [79]. BamD, like BamA, is crucial for OMP assembly, and its absence causes cell death [80]. It is one of the most conserved BAM lipoproteins. BamD supposedly interacts with BamA through its POTRA5, and establishes interactions with BamC and BamE [80].

How does the BAM complex fold and insert the nascent OMPs? Each component of the BAM complex has a specific function [17]. The exact mechanism by which the nascent OMP is assembled in the membrane remains unclear, and some the mechanisms proposed thus far [15,66,69] are discussed in Section 3.5. Briefly, it is believed that BamA and BamB recognize and assemble the substrate, while BamD recognizes the C-terminal targeting sequence (β-signal) in the precursor OMP. The POTRA domains on BamA guide the substrate into the barrel scaffold that, in turn, facilitates β-strand formation and assembly. The flexibility of the POTRA domain is believed to be important for this step. BamB might assist the POTRA domain in improving the efficiency of unfolded OMP transport, while BamE may recruit phosphatidylglycerols to regulate the folding efficiency. BamC is believed to act through its unstructured N-terminus to regulate the β-signal binding activity of BamD. Overall, the subunits act in concert to increase the efficiency of OMP biogenesis. A few of the various hypothesis on how the BAM complex mediates its function of barrel insertion and folding, are discussed below (Section 3.5) in greater detail.

3.5. Models for folding and insertion of OMPs by BAM complex

Current in vitro data suggests that the folding and membrane insertion of OMPs takes place in a concerted manner (Fig. 6). There are several OMP folding mechanisms available to date. One of the first models proposed that the transmembrane region of BamA could act as a channel to thread the unfolded substrate OMP across the bilayer (reviewed in Ref. [17,81]). This model was based on structural studies of FhaC (a BamA homolog), wherein it was observed that the binding of the FhaC substrate increased the channel diameter allowing substrate entry. Similarly, it was speculated that BamA could undergo a conformational change that facilitated unfolded OMP movement. A major drawback of this model is that it is hard to perceive how unassisted OMP folding could occur in the absence of folding factors in the extracellular surface of the outer membrane.

Fig. 6.

Proposed pathway of barrel assembly and OMP biogenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. A stepwise description of unfolded OMP (uOMP) sorting and assembly is presented pictorially here, and occurs as follows. The process of OMP synthesis starts in the cytoplasm where a nascent polypeptide is released from the ribosome and is recognized by the cytoplasmic chaperone, SecB. The polypeptide translocates from the cytoplasm across the inner membrane into the periplasm through SecYEG, using energy from ATP hydrolyzed by SecA ATPase. The signal peptide is removed in this process. In the periplasm, the polypeptide interacts with the major periplasmic chaperones, Skp or SurA, which sequester the nascent OMP. These chaperones retain the OMP in its unfolded state, prevent misfolding, and help these transmembrane hydrophobic proteins remain soluble in the periplasm. The OMPs that are not recognized by the chaperones misfold and aggregate in the periplasm. These misfolded proteins are subjected to degradation by proteases like DegP. The Skp/SurA-bound polypeptide is released from the chaperone-substrate complex and is handed over to the BAM complex for its assembly into the outer membrane. It is believed that BamA recognizes the unfolded OMP by the C-terminal β-signal sequence. After this recognition, BamA facilitates the spontaneous folding of the OMP in the outer membrane by creating defects in the bilayer (bilayer thinning). Alternately, the lateral gate of BamA opens and the unfolded OMP is threaded through the membrane, likely by β-augmentation. The opening/closing motion of the lateral gate is believed to facilitate OMP assembly. Once the assembly is completed, BamA gate is closed and this leads to termination of OMP assembly and OMP release. The precise mechanism used by BamA for OMP assembly is still unclear.

Another model of OMP assembly predicted that the BAM complex forms a tetramer in vivo, and substrate folding occurred in the space formed between the four BamA subunits (reviewed in Ref. [17,81]). Here, BamA would serve as the scaffold to thread the unfolded substrate, following which each strand would adopt its structure in the membrane. It was proposed that the limited folding space presented by the tetramer would facilitate closing of the β-sheets into a β-barrel, which would be released into the bilayer. However, no direct evidence for BamA tetramers has been obtained thus far.

Recent studies suggest that BamA works by creating a membrane defect in the vicinity of its β-strands 1 and 16. This leads to membrane thinning, which further lowers the kinetic barrier that is imposed by the outer membrane [15], facilitating the folding of the substrate OMP. The substrate OMP is recognized by its C-terminal β-signal sequence [14,16,18,64]. Data from BamA assembly-defective mutants indicate that certain mutations (G771A and F738A) inhibit its interaction with BamD and the β-signal, which further halts the BAM assembly machinery [82]. Hence, recognition of the unfolded OMP by the BAM assembly machinery [83] and physical defects introduced in the membrane by the asymmetric structure of BamA together leads to folding of the nascent OMP (Fig. 6). In another mechanism, lateral opening of BamA is also considered as one of the ways by which the nascent OMP might insert into the membrane (see Fig. 5). It is believed that the exposed unpaired strands 1 and 16 of BamA might provide a lateral opening through which OMPs would travel to the membrane [73]. This lateral opening is presumed to be initiated or triggered by the β-signal of the nascent OMP, following which interaction of the OMP β-hairpin with the BamA barrel is established. Nascent OMPs might then be folded by β-augmentation, and are later detached from the BAM complex (Fig. 6) [67]. It must be noted that there is still no experimental evidence that β-augmentation indeed occurs.

Both these mechanisms have specific features that make them plausible. The membrane thinning model emphasizes on the recognition of OMP by the BAM assembly and a folding pathway post-recognition through the physical process of modulating membrane thickness. The lateral opening model justifies how regulation of OMP folding can be achieved by preventing uncontrolled insertion of porins in the outer membrane upon thinning of the membrane. Hence, the actual mechanism of BAM complex functioning might involve steps from both the models discussed above. It is also possible that one mechanism is favored over the other depending on the size and nature of the OMP substrate. For example, LptD folding is nucleated in the periplasm [83]. Here, it was observed that BamA and BamD catalyze the reaction by conformationally constraining unfolded LptD, thereby promoting spontaneous folding of the LptD barrel. As the periplasm is devoid of ATP, the folding free energy of the unfolded OMP must be relatively high to act as the major driving force for OMP assembly in the outer membrane [25].

4. Mitochondrial machinery for membrane protein insertion

Mitochondrial β-barrel OMPs are produced in the cytosol and imported into the organelle. In eukaryotes, co-translational folding of outer membrane barrels (mitochondrial OMPs) into the mitochondrial outer membrane is not known to occur. Instead, mitochondrial OMPs assemble through a convoluted mechanism that is evolutionarily similar to the bacterial OMPs. Nascent (unfolded) mitochondrial OMPs are translocated from the cytosol to the intermembrane space (IMS) through translocases in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Subsequently, the unfolded OMP is assembled in an orchestrated manner and involves the chaperones and assembly machinery. The challenge for the protein translocation system is the correct integration of the hydrophobic precursor proteins into phospholipid bilayers, because these membrane proteins with different transmembrane topologies require different biogenesis pathways. Another challenge includes the transportation of the hydrophilic segments of the nascent polypeptide across the membrane, and recognition of the hydrophobic stretches representing the transmembrane segments by translocase and integration of this stretches into the phospholipid bilayer. The energetic challenges of mitochondrial OMP transport across the membrane, process of secondary structure formation and tertiary structure assembly are similar to the bacterial systems. Here we discuss recent findings on the structure and function of the various molecular machineries for mitochondrial membrane protein insertion.

4.1. TOM complex: the mitochondrial entry gate

In prokaryotes, SecYEG is responsible for the translocation of proteins from cytoplasm into the periplasm through inner membrane. It is an evolutionarily conserved translocon across prokaryotes and eukaryotes [84,85]. It is referred to as Sec61αβγ in eukaryotes. The components of Sec61 translocation machinery, namely Sec61α (SecY), Sec61β and Sec61γ (SecE) are homologous to the components of SecYEG except for the SecG protein [85]. Sec61α and γ subunits are indispensable for cell survival [86]. However, the Sec61 complex is responsible for the translocation of proteins across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane [86], and is not involved in the import of mitochondrial OMPs from the cytosol to the mitochondrial intermembrane space.

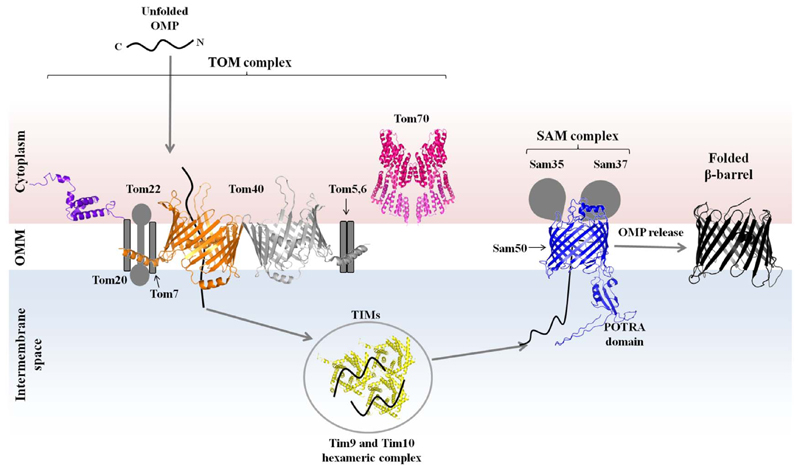

The mitochondrial import machinery is the TOM (the translocase of the outer membrane) complex (Fig. 7). The TOM complex imports all mitochondrial outer membrane proteins encoded by nuclear genes and synthesized in the cytosol. The TOM complex imports the mitochondrial OMP in its unfolded state, which is then assembled by the SAM/TOB complex (the sorting and assembly machinery/topogenesis of the outer membrane β-barrel proteins). The TOM and SAM/TOB complex work in a relay to execute mitochondrial OMP biogenesis [63]. The TOM complex or its equivalent has not been identified in Gram-negative bacteria, suggesting that eukaryotes evolved a different machinery for the import of nascent mitochondrial OMPs while it retained the SAM complex for β-barrel folding and assembly in the outer mitochondrial membrane.

Fig. 7.

Interplay between TOM and SAM complex in the mitochondrial outer membrane. Schematic representation of the components of the TOM and SAM/TOB complex involved in mitochondrial OMP folding in the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM). Tom40 is the channel forming protein of the TOM complex (modeled structure), and it is present as a dimer (gold and grey). Tom20 (PDB ID 1OM2, purple) and Tom70 (PDB ID 2GW1, pink) form the primary receptor subunits of the TOM complex. The TOM core complex also contains Tom5, Tom6, Tom7 and Tom22 (structures not known; grey schematics). Tim9 and Tim10 (PDB ID 2BSK, yellow) are members of tiny TIMs. They retain the nascent mitochondrial OMP in its unfolded state and transfer the polypeptide to the SAM complex. The SAM complex (blue) is made of at least three proteins, whose structures are not yet known. Sam50, which is the homolog of Omp85 (modeled structure), is the core protein, and it is associated with Sam35 and Sam37. Tom40 was rendered based on the recent cryo-EM structure of the TOM complex [161]. Sam50 were modeled using I-TASSER [162] based on the structure of BamA; Sam50 structure has not been experimentally determined. Other structures were obtained from the PDB and rendered using PyMOL.

A significant number of mitochondrial proteins are encoded in the nucleus and synthesized in the cytoplasm. The influx of proteins through the main entry gate of mitochondria – TOM complex – determines the functionality and growth of mitochondria [87]. The major player of the TOM complex is the β-barrel protein Tom40, which is the central pore-forming TOM subunit and the translocase for protein import into mitochondria (Fig. 7). Additionally, the TOM complex consists of six other accessory proteins made up of single pass α-helical structures (Fig. 7). This includes three receptor proteins, namely, Tom20, Tom22, and Tom70, and three small Tom proteins, Tom5, Tom6, and Tom7 [88], which are together responsible for the assembly and stability of the complex [89,90]. It is suspected that the TOM complex has nine subunits, with Tom37 and Tom72 as additional receptor subunits [87].

The translocation pathways that different proteins follow through the TOM complex are not well understood. TOM complex proteins are also synthesized in the cytosol and transported into the mitochondria [91]. The TOM complex itself is comprised of two Tom40 subunits that are interconnected by two Tom22 receptor molecules; they may also exist as three copies each of Tom40 and Tom22. Tom5, 6 and 7 are present around each Tom40 barrel [88]. Tom20 and Tom70 are loosely associated with Tom40. Mitochondrial preproteins that possess positively charged targeting sequences are recognized by the Tom20-Tom22 complex. More hydrophobic sequences are recognized by the Tom70-Tom37 complex [87,92]. These recognized sequences are then transferred to Tom40 with the help from Tom22 and Tom5 [92]. Together all the six proteins are essential for the stability and functioning of the TOM complex.

4.2. Chaperones of the intermembrane space

In the mitochondrial intermembrane space, the nascent mitochondrial OMP is prevented from misfolding or aggregation by binding to a group of molecular chaperones called as tiny TIMs (translocase of the inner membrane; Fig. 7) that function in a similar way as Skp or SurA in bacteria [38,87,93]. However, the sequence and structure of Skp/SurA is distinct from the tiny TIMs. Although Tim10c (a member of TIM subfamily, Tim10) and SurA share a similar basic structure (both are α-helical proteins) and substrate binding specificity [94], evolutionary correlation between the chaperones is not established so far.

4.3. Sorting and assembly machinery (SAM) complex

Biogenesis of transmembrane β-barrels in the outer mitochondrial membrane (mitochondrial OMPs) is facilitated by the interplay of the components of TOM complex and SAM complex (Fig. 7). OMPs assigned specifically for the mitochondrial outer membrane are assembled by the SAM complex. Mitochondrial OMP precursors are first recognized and fully imported by the TOM complex to the intermembrane space from where they are transferred to the SAM complex for folding and assembly. Hence, the SAM complex is also called topogenesis of mitochondrial outer membrane β-barrel proteins (TOB) complex [95]. Structurally and functionally, the SAM complex closely resembles the BAM complex of bacteria. Hence, the mitochondrial and bacterial OMP assembly machinery are related evolutionarily.

In yeast, the SAM complex is composed of three subunits: Sam50, Sam35, and Sam37. Sam50 forms the core component of this complex, and is the eukaryotic homolog of Omp85/BamA from bacteria. The homolog of BamA in chloroplast is Toc75. We are able to readily model Sam50 based on the 16-stranded β-barrel scaffold of BamA (see Fig. 7). Whether Sam50 indeed adopts this scaffold remains to be established experimentally. The C-terminal transmembrane β-barrel domain of Sam50 is similar to BamA [93]. However, in interesting contrast to the five POTRA domains in BamA, Sam50 possesses only one POTRA domain at the N-terminus, which faces the mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS). Further, unlike BamA, the POTRA domain of Sam50 is not essential for its function [38,93,95]. The two other subunits Sam35 (Tob38, Tom38) and Sam37 (Mas37, Tom37) are located on the cytosolic side, and have no homologs in bacteria. While BamA can function independent of the BamBCDE lipoproteins in vitro, Sam35 and Sam37 are essential for the function of the SAM complex [96]. Sam35 is a peripheral membrane protein that helps in substrate recognition through a β-signal – like motif found in mitochondrial OMPs [20,93,97]. Sam37 is known to interact with Tom22, and is required for the stability of SAM complex [93], as well as the formation of the TOM-SAM complex [96]. It also supports the release of the nascent barrel from the translocase. Experimental evidence suggests that sam50 mutants in yeast show defective assembly of Tom40, indicating that Sam50 assembles the Tom40 barrel [98,99]. The SAM complex is also implicated in the biogenesis of the α-helical Tom proteins in the TOM complex [100].

An interesting consequence of the evolution of the bacterial BAM complex into the SAM complex in eukaryotes is that pathogens (Gram-negative bacteria) may use the eukaryotic host machinery to fold and assemble their proteins in the mitochondrial outer membrane [101]. For example, bacterial toxins that target mitochondria are folded by the SAM complex. The Neisseria gonorrhoeae porin is known to use the same import machinery in the mitochondrial membrane that is used to fold VDAC [102]. The evolutionary similarity in both assembly machines was also established by the seminal work from the Tommassen and Rapaport groups [103]. They expressed bacterial membrane proteins PhoE and Omp85 in yeast cells to show that they were assembled correctly in the mitochondrial outer membrane.

4.4. Structural organization of the TOM – SAM supercomplex

During their two-step import, β-barrel precursors need to travel from the TOM complex through the intermembrane space to SAM. Hence, the SAM and the TOM complex work in a coordinated manner to carry out the sorting and assembly of outer membrane β-barrels of the mitochondria (Fig. 7). Experimental evidence suggests that the formation of a TOM-SAM supercomplex makes β-barrel biogenesis a more efficient process [104]. This complex formation is mediated by the Tom22 receptor of the TOM complex and Sam37 of the SAM complex [96,105]. The absence of Tom22 leads to a decrease in the efficiency of transfer of β-barrels from the TOM to the SAM complex. Accessory proteins also involved in mitochondrial OMP biogenesis and association with the TOM-SAM supercomplex includes the tiny TIM proteins. These are six-bladed α-propeller chaperone complexes specialized in escorting hydrophobic precursors through the intermembrane space, and prevent the misfolding or aggregation of β-barrels [87,94,106]. However, no substrate-bound TIMs have so far been reported.

4.5. Mechanism of SAM–dependent β-barrel insertion

The subunits of the SAM complex have been characterized functionally, but currently elude complete structural characterization. Therefore, as in the case of the BAM complex, the precise mechanism of β-barrel formation and membrane insertion in vivo remains obscure. The structural similarity predicted between BamA and Sam50 suggests that the basic mechanism by which both barrels fold OMPs would also be similar. However, a few striking differences exist between the bacterial and mitochondrial machinery. For example, Sam50 contains only one POTRA domain. The models that require movement of the POTRA domain for substrate entry might not be applicable here. Further, the SAM complex also folds odd-stranded barrels (Tom40 and VDAC); these β-barrel substrates are not encountered by the bacterial transmembrane β-barrels. Additionally, the presence of a specific β-signal at the C-terminus of nascent mitochondrial OMPs is not very well characterized. For instance, eukaryotic β-barrels like VDACs lack a β-signal motif that bears a distinct Aro-Xaa-Aro sequence at the C-terminus (human VDAC2 ends with Leu-Glu-Ala). Instead, the recognition motif is a structural element composed of hydrophobic residues that are located towards the C-terminus and on the last two strands of the protein scaffold [63,107]. Nevertheless, the β-signal motif of bacterial OMPs can be recognized by the mitochondrial folding machinery [108,109]. It is also known that bacterial folding machinery can assemble exogenously expressed VDAC [110]. These evidences point to the existence of a β-signal–like motif in mitochondrial OMPs, although they seem to be less conserved than their bacterial counterparts. Among the mechanisms hypothesized for barrel insertion by Sam50, experimental evidence indicates that protein insertion may happen via the lateral gate of Sam50 [106] and might proceed further by β-augmentation. We currently have limited experimental evidence for β-augmentation. However, experimental evidence indicates that the SAM complex might catalyze insertion of partially folded mitochondrial OMPs in a manner similar to the bacterial BAM complex [20].

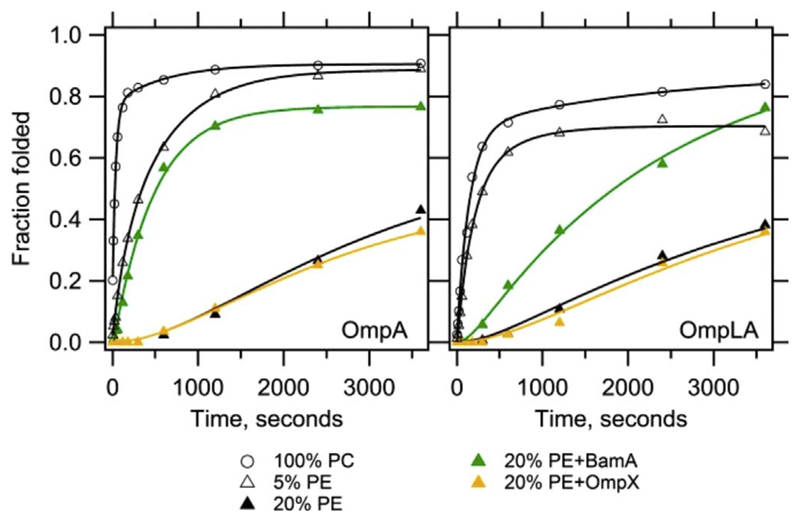

5. Role of lipids in OMP folding

We currently have limited information on how lipids control OMP folding in vivo. In bacteria, it has been argued that the presence of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and phosphatidylglycerol (PG) in both the outer and inner membranes creates a kinetic barrier during OMP folding (Fig. 8) [15]. Such a barrier is required to direct the unfolded OMP to the outer membrane and prevent its spontaneous insertion in the inner membrane. Results from in vitro folding kinetics suggests that membrane thinning created by BamA coupled with the assisted folding of the Skp-SurA-BAM complex together direct the correct folding of OMPs in the bacterial outer membrane.

Fig. 8.

Lipid headgroup controls OMP folding. Experimentally measured OMP folding rates in vitro in phosphocholine (PC) lipid vesicles doped with PE or PG. The presence of PE or PG lowers the folding rate of the substrate OMP (OmpA and OmpLA). The presence of BamA in the vesicles accelerates the folding of the substrate OMP. Figure reproduced with permission from Ref [15]. Copyright 2014 National Academy of Sciences.

The lipid composition of the cell membrane also plays an important role in the translocation of proteins. Non-bilayer and negatively-charged lipids like PG and cardiolipin are important for protein transport across the membrane They might play a role in introducing curvature stress, which might be important for the assembly of SecYEG translocon [111,112]. Protein-lipid interactions are responsible for proper functioning of membrane proteins of bacterial as well mitochondrial origin [112].

6. Unassisted OMP folding

The in vivo folding of OMPs and mitochondrial OMPs are strictly governed by holdases and assembly machines. However, nearly all OMPs that have been studied so far can fold correctly in various lipidic environments without chaperones. Strategies to prevent aggregation and facilitate folding include the use of denaturants and detergents as mimetics of holdases. OmpA [113] and OmpF [114] were the first β-barrels that were successfully folded in vitro using SDS and urea, respectively, as the denaturants. Folding in vitro is achieved by rapid or stepwise dilution of the unfolded OMP in denaturant (urea, guanidine hydrochloride, SDS, etc.) into lipid vesicles or detergent micelles that provide the necessary folding environment [115]. For example, OmpA folding in lipid bilayers has been achieved by a 100-fold dilution of the urea-unfolded protein in palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (C16:0 C18:1 PC) small unilamellar lipid vesicles (SUVs) [116]. The outer membrane enzyme PagP has been folded by dropwise dilution from guanidine into n-dodecylphosphocholine micelles [117] or diC12:0-phosphatidylcholine (diC12:0PC) vesicles additionally containing 6–7 M urea [28]. OmpX can be folded in an array of detergent micelles, lipid vesicles, bicelles, and bilayers, by rapid or slow dilution from various denaturants (urea, guanidine, SDS) [118–121]. Ail, which belongs to the same family of adhesins as OmpX, folds spontaneously in a variety of detergents and lipids at 25 °C, without the need for further processing [122]. The folding time also varies for various OMPs. For example, while OmpX folds within minutes in lipids, the transmembrane domain of OmpA (which is structurally similar to OmpX) folds slower at the same folding temperature [123].

Detergents have been used to fold transmembrane β-barrels. While efforts are being made to solve the structures of membrane proteins in near-native conditions using lipid vesicles and bicelles, many transmembrane β-barrel protein structures have been determined in detergent micelles [13,117,124,125]. Detergents with high critical micelle concentration such as C8E4, SB10, SB12, CHAPS, CYFOS etc., are also now used as carriers to transfer unfolded OMPs into vesicles [126]. They mimic the in vivo holdases and mainly prevent the unfolded OMP from aggregation. The amphipathic nature of micelles makes them highly suitable as solubilizing agents for membrane proteins. Amphipols and other membrane protein mimetics also support OMP assembly [127–129], suggesting that the OMP only requires a membrane-like environment to fold, and the exact chemical nature of the detergent or lipid does not substantially inhibit scaffold assembly.

Defects in the bilayer also promote rapid OMP folding. Such defects can be introduced with temperature (Fig. 9) [130–132], unsaturated lipids [116], SUVs [132,133], and the use of short chain lipids with inherent packing defects [123,134,135]. Such defects are introduced in vivo by the asymmetric structure of BamA [15], to promote rapid folding of OMPs. It is believed that in vitro OMP assembly in lipidic environments follows a multi-step pathway. Experiments reveal that the initial adsorption step is very rapid, while the barrel insertion and assembly in the membrane can occur in minutes–hours (discussed later in Fig. 13). The kinetics of this process is OMP and membrane dependent [15]. It has been argued that the BAM complex particularly assists in accelerating this step in vivo [15].

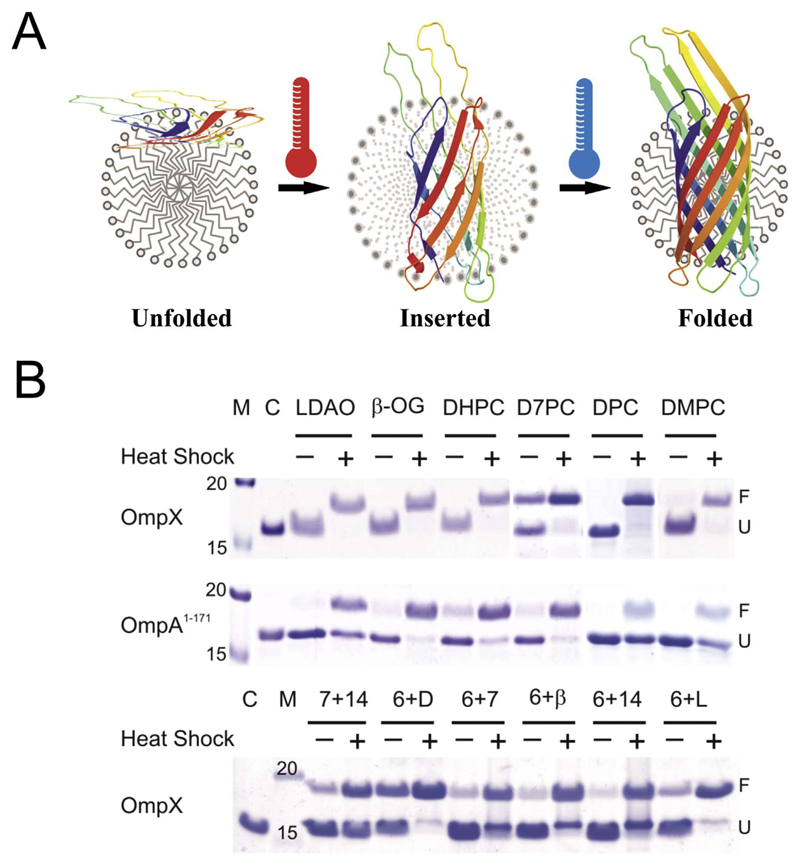

Fig. 9.

Use of heat shock to drive OMP folding. (A) Schematic representation of how heat shock can be used to introduce transient perturbations in the lipidic assembly to drive OMP folding. (B) Heat shock can be used to fold OMPs (shown here are data obtained from OmpX and the transmembrane domain of OmpA (OmpA1–171)) in micelles such as lauryldimethylamine oxide (LDAO, L), β-octylglucoside (β-OG, β), 1,2-dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DHPC, 6), 1,2-diheptanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (D7PC, 7), dodecylphosphocholine (DPC, D), vesicles of 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC, 14) and mixed micelles and bicelles. Figure reproduced with permission from Ref. [130].

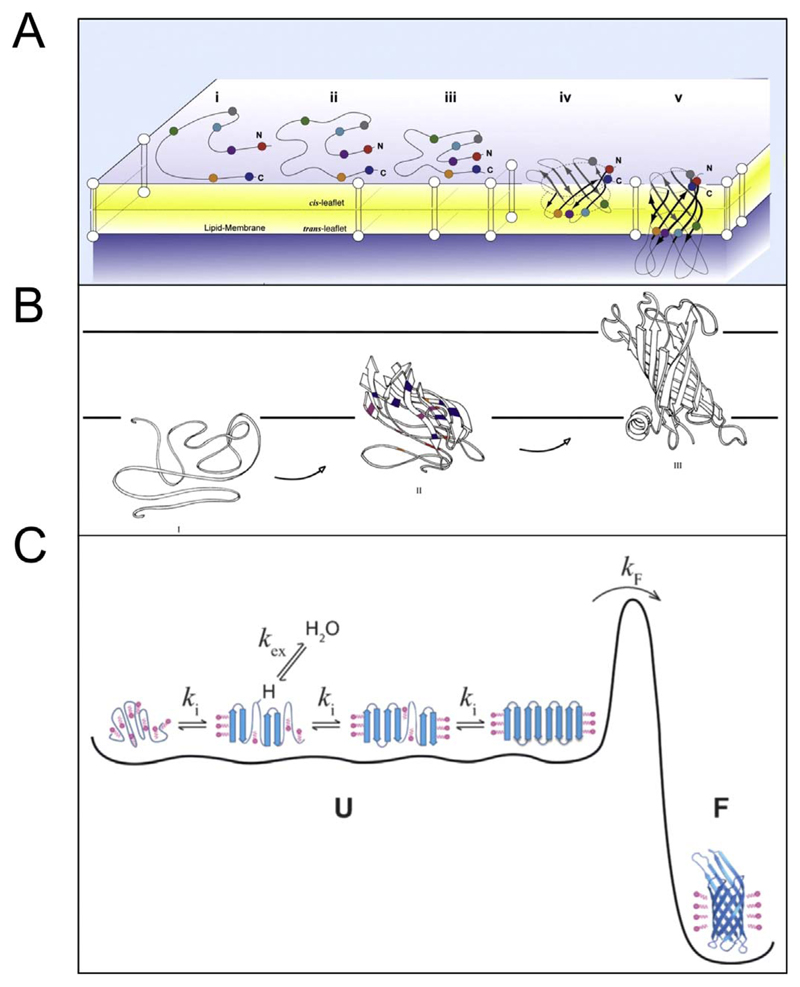

Fig. 13.

Proposed mechanisms of unassisted folding of OMPs. Three possible mechanisms of OMP assembly have been proposed based on experimental data. (A) This scenario (proposed based on studies on E. coli OmpA) involves a concerted folding mechanism of OMPs that follows an initial rapid adsorption event, which is followed by a slower process of strand assembly and insertion [131]. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [131]. (B) This mechanism is similar to (A), with the exception that strand assembly exhibits directionality. This mechanism, proposed based on studies of PagP, involves a more rapid assembly of the C-terminal strands than the N-terminal region of the barrel [154]. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [154]. Copyright 2010 National Academy of Sciences. (C) This mechanism involving the formation of a dynamic ensemble of conformationally interconvertible states has been currently proposed based on experimental observations using OmpX in dodecylphosphocholine micelles [121]. Here, cooperative folding of OmpX occurs when the ensemble overcomes the transition state barrier (U → F, with a rate of k F). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [121].

The folding of outer mitochondrial transmembrane β-barrels in vitro has been attempted from inclusion bodies, and this has been successful with VDACs and Sam50 [20]. The folding of VDACs from various organisms (including human VDACs) has been achieved in various detergent and lipidic conditions using similar protocols as bacterial OMPs [136–139]. With the development of better lipid mimetics, it would be possible to fold several other eukaryotic β-barrels.

7. Energetics of membrane protein folding

As dictated by the second law of thermodynamics, every system tries to attain its lowest energy state. Achieving a free energy minimum is what drives a protein to fold into a compact and functional state. In turn, the fold is determined by the primary protein sequence. Yet, as simple as it sounds, it has been challenging to decode the information on how a protein achieves its free energy minimum, from its primary sequence. This problem is further magnified in membrane proteins. Several interaction forces that include protein-solvent interactions, intra-protein interactions, and protein-lipid interactions [140,141] influence the polypeptide as it travels downhill on the free energy funnel from the unfolded to the folded state. The introduction of an asymmetric lipid bilayer with a dynamic composition introduces an additional variable. Despite the tremendous progress in elucidating the structure of membrane proteins, we still lag behind in our understanding of the thermodynamics of membrane protein folding. This section discusses what we have currently understood, and a few aspects of the problems.

7.1. Reversibility and path independence

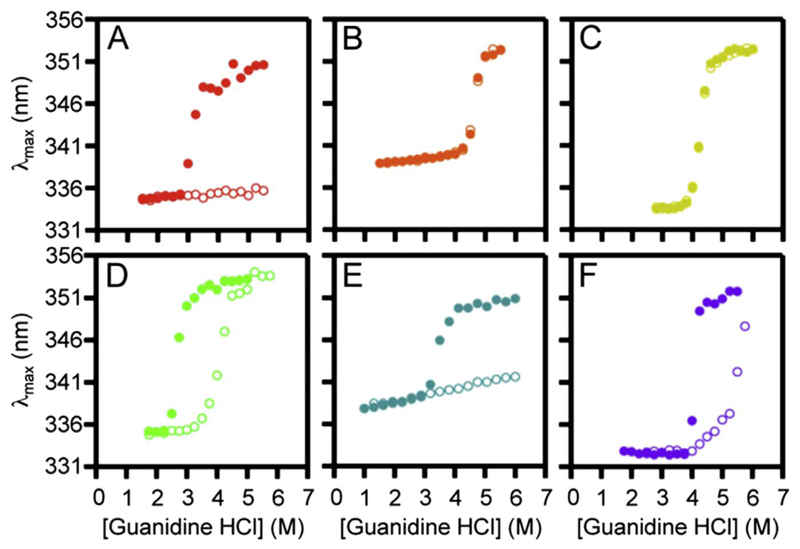

Thermodynamic parameters can be measured only in systems that exhibit path independence [142]. Owing to the complex nature of interactions established by membrane proteins, obtaining a condition of no hysteresis has been a Herculean task. Earlier studies used detergent micelles to achieve path independence in the transmembrane β-barrel OmpA. More recently, reversibility has been achieved in lipid vesicles (SUVs and large unilammelar vesicles (LUVs)) for select proteins [116,143]. However, several transmembrane β-barrels evade thermodynamic characterization. One such lipidic condition is shown in Fig. 10, wherein path dependence prevails for several OMPs including OmpX, full-length OmpA, OmpT and FadL, while PagP, OmpW, and OmpLA show reversible folding [25].

Fig. 10.

Hysteresis and path independence. Equilibrium folding (filled circles) and unfolding (open circles) measurements of six transmembrane β-barrels in phosphocholine LUVs. Here, PagP (B) and OmpW (C) show path independence and no hysteresis, whereas OmpA (D) and FadL (F) show hysteresis under the same condition. OmpX (A) and OmpT (E) show no unfolding even in 6 M GdnHCl. Figure reproduced with permission from Ref. [25]. Copyright 2014 National Academy of Sciences.

The choice of the folding environment depends on whether it leads to the formation of a completely folded, near-native state of the protein that is also functional [141]. Further, the folding environment must mimic the lateral bilayer pressure and provide a condition of hydrophobic match for the transmembrane region of the barrel. An additional condition is that it closely mimics the natural environment of the protein, to allow for extrapolation of the findings from in vitro studies to the lipid bilayer of the cell. Thus far, such near-native conditions have not supported path independence, as a result of which most thermodynamic measurements of bacterial OMPs have been carried out in detergents or phosphocholine lipids. The asymmetric nature of the bacterial outer membrane is also challenging to mimic in vitro; our current understanding of β-barrel dynamics is therefore limited to atomic force microscopy measurements in vitro and molecular dynamics simulations.

Equilibrium measurements in phosphocholine systems have revealed that folded bacterial OMPs are more stable than their soluble counterparts. The change in free energy for these proteins range largely from − 18 to − 32 kcal mol−1 in LUVs and − 5 to − 15 kcal mol−1 in SUVs and micelles [27,116,144]. The folded OMP state is therefore highly stable and resists unfolding. Kinetic measurements support fast folding and slow unfolding rates for these OMPs [144,145], which has led to the conclusion that the β-barrel structures are kinetically stabilized systems. It has been argued that due to their location in the outer membrane of bacteria, these OMPs are subjected to extreme environmental conditions despite which they must retain their folded state. As a result OMPs have evolved such that a large energetic barrier separates the folded state from the transition state during protein unfolding [25]. A similar kinetic barrier to unfolding has been observed when long chain lipids and rigid lipidic systems are used to fold OMPs. In contrast, short chain lipids and micellar systems promote greater protein dynamicity that, in turn, can lower the kinetic barrier to OMP unfolding. We discuss this aspect in Section 7.2.

7.2. Systems under kinetic control

Protein stability has been addressed from the perspective of thermodynamics, where a protein achieves the lowest free energy state in its process of folding. The lowest free energy state is the functional or the active state of the protein [146], and is considered the global (thermodynamic) minimum. Such a thermodynamic equilibrium possesses a moderate energy barrier between the folded and unfolded states. Reversibility can therefore be achieved between both these states with little change in the external constraints, although the equilibrium predominantly populates the folded state. However, not all proteins are stabilized thermodynamically. A protein is said to be in a kinetically trapped state when there is a high energy barrier separating the native from the unfolded state [147–149]. Simply put, a protein is under kinetic control when its stability can be explained using high folding rate constants and slow unfolding rates. Such proteins are kinetically trapped in their folded state, as the energy barrier for unfolding is very high. When unfolded, such proteins can attain irreversibly denatured states that are usually highly stable aggregated or misfolded forms, or altered metastable states.

Kinetic stability was firstly observed in α-lytic protease [148]. Like many other proteases, the proenzyme of α-lytic protease exhibits thermodynamic stability. Once folding is achieved, and the proenzyme is processed to the active form, the system now is under kinetic control. Transmembrane β-barrels are known to exist in a kinetically controlled state [144,145]. The unfolding process becomes exceedingly slow in such cases, and the corresponding rates of unfolding are therefore very low. In a recent study, the E. coli transmembrane α-helical protease GlpG was also shown to have a very high unfolding barrier [149], suggesting that kinetic stability can be a general stabilizing factor across various membrane proteins.

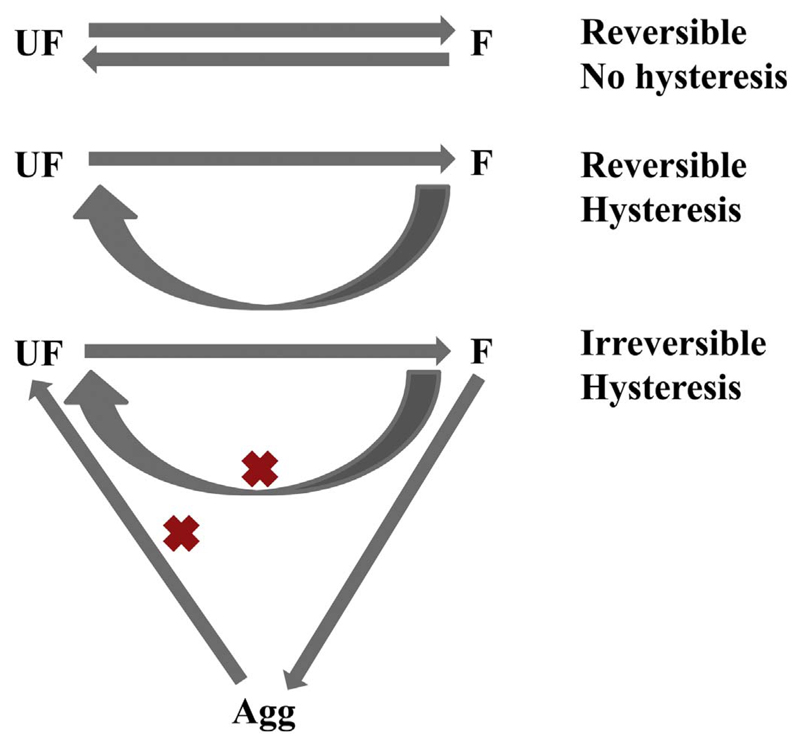

One of the consequences of systems under kinetic control is that the folding and unfolding pathways do not always superimpose within reasonable experimental timeframes, leading to hysteresis in the system. An extreme case of hysteresis is seen when protein unfolding or misfolding leads to aggregation. Such aggregates are kinetically trapped in a metastable or low energy state and the energy barrier for refolding is largely insurmountable. This is represented schematically in Fig. 11. The primary sequence of the protein and the surrounding lipidic or detergent environment also play important roles in determining the folding and unfolding pathways. One such experimental outcome is provided for the Y. pestis OMP Ail in Fig. 12 [122].

Fig. 11.

Possible consequences of OMP folding. OMPs such as OmpA [116,156,163]), OmpLA [143]), OmpW [25] and PagP [25,154,164]) exhibit reversibility and path independence when subjected to chemical denaturation under specific conditions of the folding lipid environment and buffers (upper scheme). OMPs such as Ail [122], full-length OmpA and FadL [25] (chemical denaturation) and OmpX [155] (thermal denaturation) show reversibility with path dependence in the folding/unfolding process (middle scheme). Some OMPs show irreversible unfolding and aggregation when subjected to thermal denaturation (lower scheme) [138,165]. F: folded; UF: unfolded; Agg: aggregated protein.

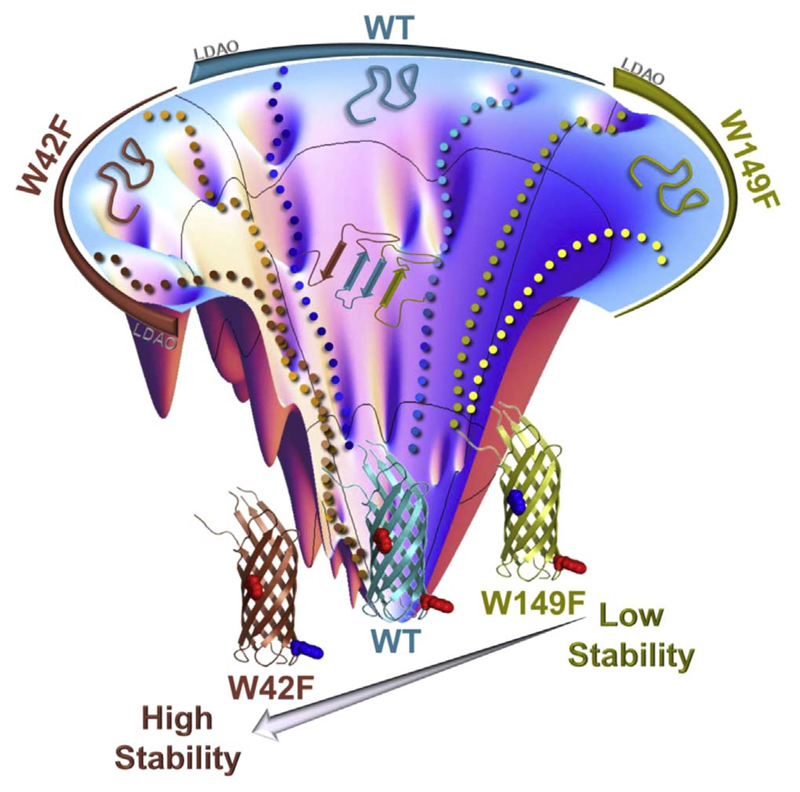

Fig. 12.

Influence of detergent-protein ratio and mutations on the OMP folding pathway. Shown here is a schematic folding funnel highlighting how the lauryldimethylamine oxide (LDAO) concentration influences the folding of the 8-stranded OMP Ail from Y. pestis. Also shown is the consequence of mutating interface tryptophans on the folding pathway and resultant stability of the folded barrel. Figure reproduced with permission from Ref. [122].

The obvious question that arises from such observations is the physiological or evolutionary significance of hysteresis loops. There is an evolutionary bias for proteins to be trapped in local minima that are energetically less stable than the global minima, in cases where this local minimum allows superior function. In the case of OMPs, a kinetically trapped state may be important to retain protein stability despite extreme duress on the outer membrane from the environment. It is therefore no surprise that in most cases, folded OMPs are usually not recycled, but are removed from the bacterial membrane in the form of OMVs [30]. However, mitochondrial OMPs may require recycling when they are damaged due to oxidation or misfolded [150–153]. Hence, it is tempting to speculate that mitochondrial OMPs should be in thermodynamic equilibrium between the folded and unfolded states; whether this is true requires experimental validation under conditions that closely mimic the native environment of the mitochondrial outer membrane.

8. Open questions and future directions

Transmembrane β-barrels have opened avenues to study forces that drive membrane protein folding and energetics associated with protein stability. The importance of these proteins in bacterial survival and in the functioning of mitochondria and chloroplast emphasizes the need to understand their assembly in vivo. Current studies of OMP behavior in vitro have highlighted the gap that exists between our understanding of OMP thermodynamics in artificial systems and a more realistic concept of folding and stability under native conditions. First, although attempts at reconstituting the assembly machinery with the molecular chaperones and holdases have been successful, the complexity of the in vivo lipidic environment in itself offers immense challenges to replicate in vitro. Secondly, it is almost impossible to regenerate the same interactome that is present in the cell membrane during the lifetime of the protein. This aspect becomes critical to membrane protein function and stability, considering that proteins, even if not interacting, are always in close association with the other biomolecules present in the membrane (known conventionally as macromolecular crowding). Thirdly, protein folding pathway(s) in the absence of chaperones, BAM complex and other effector molecules can be considerably different in vitro. In 1996, Tamm and co-workers presented evidence for the presence of folding intermediates in the in vitro folding process of the β-barrel OmpA [132] (Fig. 13). Subsequently, studies with other OMPs including PagP [154] and OmpX [121,155] have suggested that OMPs undergo multi-step folding in vitro (Fig. 13). Such intermediates observed in vitro are unlikely to exist in vivo, in BAM-assisted folding of OMPs (see Figs. 5 and 6), although the OMP biogenesis is still likely to remain a multi-step event (as seen, for example, in LptD folding [83]).

A remarkable effort is now being made to bridge the gap between what happens in vivo and what is achieved in vitro. The use of lipid vesicles in the place of detergents, doping lipid vesicles with the desired amounts of phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, cholesterol, cardiolipin, total lipid extracts etc., and the incorporation of Skp, BamA and other holdases in these lipid systems, are some ways to transition from in vitro to in vivo – like environments. Yet, several challenges and unanswered questions still remain, and the observed mechanisms of OMP folding are open for interpretation. We list out a few open questions.

-

1)

What defines the interaction dynamics, specificity of recognition, and binding stoichiometry of the unfolded OMPs with molecular chaperones and the BAM complex? Several molecular chaperones in the periplasmic region including Skp, SurA, and the proteasome DegP interact dynamically with the unfolded OMP before it is transferred to the BAM complex. The molecular mechanism by which these chaperones specifically choose the unfolded OMP and the energetics of this process is still being investigated. The kinetics of association and specificity of these interactions is not fully understood. Further, we only have limited information on the stoichiometry of the binding in vivo, especially since the OMP polypeptide can vary considerably in length from ~120 residues to ~780 residues in length. Although the β-signal motif at the C-terminus of the OMP serves as the connecting link between substrate recognition by chaperones and BamA, several exceptions of species specific recognition signals are well documented [19]. For example, a few OMPs of E. coli (LamB: Ile-Trp-Trp) and Neisseria meningitidis (NspA: Val-Lys-Phe; LbpA: Met-Lys-Phe) do not possess the Aro-Xaa-Aro motif [18], and yet show no folding defects in vivo. Further, work from Tommassen's group on PhoE showed that mutants lacking the C-terminal Phe of the β-signal could be incorporated in the membrane, but with compromised folding efficiency and stability [14,16]. The Aro-Xaa-Aro motif may also serve as the recognition signal for DegS [19]. Hence, the molecular signature elements for unfolded OMP recognition by the facilitator proteins in the intermembrane space need to be unambiguously identified.

-

2)

What roles do the components of BAM and SAM complexes play during OMP biogenesis? Experimental evidence in vitro clearly supports that Bam A alone is sufficient to facilitate the folding of outer membrane proteins [15]. If this were true, what purpose do the other components of BAM assembly serve if not directly involved in folding? Indeed, a few organisms lack some of the accessory lipoproteins of the BAM complex (see [63,64]). The accessory proteins may contribute to stabilizing BamA and assisting in its function [63]. Despite the complexity of the eukaryotic SAM complex in the mitochondrial membrane, analogs of the BAM accessory proteins are not found in the SAM complex. Similarly, Sam50 has only retained one of the five POTRA domains seen in BamA. The BamBCDE lipoproteins could help stabilize the structure of BamA in the outer membrane or regulate the activity of the folding machinery. Further information from biochemical experiments will allow us to assign specific function to each protein in the BAM and SAM complex, and identify evolutionary similarities and differences between both complexes. This will lead to a detailed mechanistic understanding of how BamA and Sam50 fold OMPs.

-

3)

Energetics of OMP folding: Can in vitro measurements be extra-polated to in vivo? A fundamental problem in most of the in vitro studies is that the pH and ionic strength deviate considerably from what is recognized as a physiological condition for the organism being studied. Acidic [143] or alkaline [154–157] conditions are employed to achieve thermodynamic equilibrium. A major concern with these methods is whether the results and measured energetics can confidently be extrapolated to native conditions. A more recent study demonstrated how acidic residues can control hysteresis in bacterial OMPs [158]. Whether this indicates that the OMPs are likely to be under kinetic (and not thermodynamic) control in their native environment deserves further investigation.

-

4)

Can we bridge the gap between OMP biogenesis mechanisms in vitro and in vivo? Correlating the mechanisms of assisted folding of OMPs deduced in vitro to the mechanism employed in vivo has remained an incredible challenge (compare Figs. 5 and 6 with Fig. 13). In addition to the complex and heterogeneous folding environment that exists in vivo, it is presently unclear as to what extent the pathway mapped for the nascent polypeptide in vitro resembles that occurring in vivo.

-

5)

Does specific regulatory process exists for proteostasis of every OMP? We have not identified whether sensory signals exist that trigger the overproduction of specific OMPs depending on environmental cues. For example, the bacterial outer membrane enzyme PagP is overexpressed when the bacterial outer membrane is damaged. There is currently some evidence for how PagP production is signaled under such stress conditions [159]. Similarly, it is unclear how the levels of the other OMP are maintained in the bacterial outer membrane.

Remarkable developments in the study of bacterial and mitochondrial OMPs using spectroscopic and single molecule methods has considerably advanced the field of membrane proteins in the past decade. It is anticipated that a near-complete mechanistic understanding of membrane protein regulation and turnover will be achieved in the next decade.

Acknowledgements

D.C. is supported by a senior research fellowship from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India. R.M. is a Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance Intermediate Fellow.

Funding

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance award number IA/I/14/1/501305 to R.M.

Abbreviations

- BAM

barrel assembly machinery

- IMS

intermembrane space

- LUV

large unilamellar vesicle

- OMP

outer membrane protein

- POTRA

polypeptide transport-associated

- SAM

sorting and assembly machinery

- SUV

small unilamellar vesicle

- TIM

translocases of the inner membrane

Footnotes

Transparency document

The http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.09.020 associated with this article can be found, in online version.

References

- [1].Galdiero S, Galdiero M, Pedone C. Beta-barrel membrane bacterial proteins: structure, function, assembly and interaction with lipids. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2007;8:63–82. doi: 10.2174/138920307779941541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bishop RE. Structural biology of membrane-intrinsic beta-barrel enzymes: sentinels of the bacterial outer membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1881–1896. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wimley WC. The versatile beta-barrel membrane protein. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:404–411. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(03)00099-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Remmert M, Biegert A, Linke D, Lupas AN, Soding J. Evolution of outer membrane beta-barrels from an ancestral beta beta hairpin. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:1348–1358. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Arnold T, Poynor M, Nussberger S, Lupas AN, Linke D. Gene duplication of the eight-stranded beta-barrel OmpX produces a functional pore: a scenario for the evolution of transmembrane beta-barrels. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:1174–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Qiao S, Luo Q, Zhao Y, Zhang XC, Huang Y. Structural basis for lipopolysaccharide insertion in the bacterial outer membrane. Nature. 2014;511:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature13484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cherezov V, Yamashita E, Liu W, Zhalnina M, Cramer WA, Caffrey M. In meso structure of the cobalamin transporter, BtuB, at 1.95 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:716–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Akama H, Kanemaki M, Yoshimura M, Tsukihara T, Kashiwagi T, Yoneyama H, Narita S, Nakagawa A, Nakae T. Crystal structure of the drug discharge outer membrane protein, OprM, of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: dual modes of membrane anchoring and occluded cavity end. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52816–52819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Thanassi DG, Saulino ET, Lombardo MJ, Roth R, Heuser J, Hultgren SJ. The PapC usher forms an oligomeric channel: implications for pilus biogenesis across the outer membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3146–3151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Koronakis V, Eswaran J, Hughes C. Structure and function of TolC: the bacterial exit duct for proteins and drugs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:467–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Meesters C, Brack A, Hellmann N, Decker H. Structural characterization of the alpha-hemolysin monomer from Staphylococcus aureus . Proteins. 2009;75:118–126. doi: 10.1002/prot.22227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vogt J, Schulz GE. The structure of the outer membrane protein OmpX from Escherichia coli reveals possible mechanisms of virulence. Structure. 1999;7:1301–1309. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)80063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yamashita S, Lukacik P, Barnard TJ, Noinaj N, Felek S, Tsang TM, Krukonis ES, Hinnebusch BJ, Buchanan SK. Structural insights into Ail-mediated adhesion in Yersinia pestis . Structure. 2011;19:1672–1682. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Struyve M, Moons M, Tommassen J. Carboxy-terminal phenylalanine is essential for the correct assembly of a bacterial outer membrane protein. J Mol Biol. 1991;218:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90880-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gessmann D, Chung YH, Danoff EJ, Plummer AM, Sandlin CW, Zaccai NR, Fleming KG. Outer membrane beta-barrel protein folding is physically controlled by periplasmic lipid head groups and BamA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:5878–5883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322473111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].de Cock H, Struyve M, Kleerebezem M, van der Krift T, Tommassen J. Role of the carboxy-terminal phenylalanine in the biogenesis of outer membrane protein PhoE of Escherichia coli K-12. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:473–478. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kim KH, Aulakh S, Paetzel M. The bacterial outer membrane beta-barrel assembly machinery. Protein Sci. 2012;21:751–768. doi: 10.1002/pro.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Robert V, Volokhina EB, Senf F, Bos MP, Van Gelder P, Tommassen J. Assembly factor Omp85 recognizes its outer membrane protein substrates by a species-specific C-terminal motif. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Paramasivam N, Habeck M, Linke D. Is the C-terminal insertional signal in Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane proteins species-specific or not? BMC Genomics. 2012;13:510. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kutik S, Stojanovski D, Becker L, Becker T, Meinecke M, Kruger V, Prinz C, Meisinger C, Guiard B, Wagner R, Pfanner N, et al. Dissecting membrane insertion of mitochondrial beta-barrel proteins. Cell. 2008;132:1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schulz GE. The structure of bacterial outer membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1565:308–317. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(02)00577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bishop CM, Walkenhorst WF, Wimley WC. Folding of beta-sheets in membranes: specificity and promiscuity in peptide model systems. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:975–988. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ulmschneider MB, Sansom MS. Amino acid distributions in integral membrane protein structures. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1512:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(01)00299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Killian JA, von Heijne G. How proteins adapt to a membrane-water interface. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:429–434. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Moon CP, Zaccai NR, Fleming PJ, Gessmann D, Fleming KG. Membrane protein thermodynamic stability may serve as the energy sink for sorting in the periplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4285–4290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212527110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chaturvedi D, Mahalakshmi R. Methionine mutations of outer membrane protein X influence structural stability and beta-barrel unfolding. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Iyer BR, Mahalakshmi R. Residue-dependent thermodynamic cost and barrel plasticity balances activity in the PhoPQ-activated enzyme PagP of Salmonella typhimurium . Biochemistry. 2015;54:5712–5722. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Huysmans GH, Radford SE, Brockwell DJ, Baldwin SA. The N-terminal helix is a post-assembly clamp in the bacterial outer membrane protein PagP. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Roier S, Zingl FG, Cakar F, Durakovic S, Kohl P, Eichmann TO, Klug L, Gadermaier B, Weinzerl K, Prassl R, Lass A, et al. A novel mechanism for the biogenesis of outer membrane vesicles in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10515. 10515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Macdonald IA, Kuehn MJ. Stress-induced outer membrane vesicle production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Bacteriol. 2013;195:2971–2981. doi: 10.1128/JB.02267-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jia W, El Zoeiby A, Petruzziello TN, Jayabalasingham B, Seyedirashti S, Bishop RE. Lipid trafficking controls endotoxin acylation in outer membranes of Escherichia coli . J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44966–44975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rassam P, Copeland NA, Birkholz O, Toth C, Chavent M, Duncan AL, Cross SJ, Housden NG, Kaminska R, Seger U, Quinn DM, et al. Supramolecular assemblies underpin turnover of outer membrane proteins in bacteria. Nature. 2015;523:333–336. doi: 10.1038/nature14461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bay DC, Hafez M, Young MJ, Court DA. Phylogenetic and coevolutionary analysis of the beta-barrel protein family comprised of mitochondrial porin (VDAC) and Tom40. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:1502–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Maurya SR, Mahalakshmi R. VDAC-2: mitochondrial outer membrane regulator masquerading as a channel? FEBS J. 2016;283:1831–1836. doi: 10.1111/febs.13637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Maurya SR, Mahalakshmi R. Mitochondrial VDAC2 and cell homeostasis: highlighting hidden structural features and unique functionalities. Biol Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1111/brv.12311. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Meisinger C, Rissler M, Chacinska A, Szklarz LK, Milenkovic D, Kozjak V, Schonfisch B, Lohaus C, Meyer HE, Yaffe MP, Guiard B, et al. The mitochondrial morphology protein Mdm10 functions in assembly of the preprotein translocase of the outer membrane. Dev Cell. 2004;7:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yamano K, Tanaka-Yamano S, Endo T. Mdm10 as a dynamic constituent of the TOB/SAM complex directs coordinated assembly of Tom40. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:187–193. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Dolezal P, Likic V, Tachezy J, Lithgow T. Evolution of the molecular machines for protein import into mitochondria. Science. 2006;313:314–318. doi: 10.1126/science.1127895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Thornton N, Stroud DA, Milenkovic D, Guiard B, Pfanner N, Becker T. Two modular forms of the mitochondrial sorting and assembly machinery are involved in biogenesis of alpha-helical outer membrane proteins. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:540–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wideman JG, Go NE, Klein A, Redmond E, Lackey SW, Tao T, Kalbacher H, Rapaport D, Neupert W, Nargang FE. Roles of the Mdm10, Tom7, Mdm12, and Mmm1 proteins in the assembly of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins in Neurospora crassa. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1725–1736. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-10-0844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sommer MS, Daum B, Gross LE, Weis BL, Mirus O, Abram L, Maier UG, Kuhlbrandt W, Schleiff E. Chloroplast Omp85 proteins change orientation during evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13841–13846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108626108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Day PM, Potter D, Inoue K. Evolution and targeting of Omp85 homologs in the chloroplast outer envelope membrane. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:535. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].O'Neil PK, Richardson LGL, Paila YD, Piszczek G, Chakravarthy S, Noinaj N, Schnell D. The POTRA domains of Toc75 exhibit chaperone-like function to facilitate import into chloroplasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E4868–E4876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621179114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Schafer U, Beck K, Muller M. Skp, a molecular chaperone of gram-negative bacteria, is required for the formation of soluble periplasmic intermediates of outer membrane proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24567–24574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Patel GJ, Behrens-Kneip S, Holst O, Kleinschmidt JH. The periplasmic chaperone Skp facilitates targeting, insertion, and folding of OmpA into lipid membranes with a negative membrane surface potential. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10235–10245. doi: 10.1021/bi901403c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Beckwith J. The Sec-dependent pathway. Res Microbiol. 2013;164:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]