Abstract

We have studied the regulation of the caspase-Activated DNase (CAD) by its inhibitor, ICAD. To study the role of ICAD short and long splice forms ICAD-S and ICAD-L, respectively, in vivo, we constructed chicken DT40 cell lines in which the entire coding regions of ICAD alone or ICAD plus CAD were deleted. ICAD and ICAD/CAD double knockouts lacked both DNA fragmentation and nuclear fragmentation after the induction of apoptosis. We constructed a model humanized system in which human ICAD-L and CAD proteins expressed in DT40 ICAD/CAD double knock-out cells could rescue both DNA fragmentation and stage II chromatin condensation. ICAD-S could not replace ICAD-L as a chap-erone for folding active CAD in these cells. However, a modified version of ICAD-S, in which the two caspase-3 cleavage sites were replaced with two tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage sites (ICAD-S2TEV) and which was therefore resistant to caspase cleavage, did inhibit CAD activation upon induction of apoptosis in vivo. Moreover, ICAD-L2TEV was functional as a chaperone for the production of active CAD in DT40 cells. In extracts prepared from these cells, we were able to activate CAD by cleavage of ICAD-L2TEV with TEV protease under non-apoptotic conditions. Thus, ICAD appears to be the only functional inhibitor of CAD activation in these cell-free extracts. Taken together, these observations indicate that ICAD-S may function together with ICAD-L as a buffer to prevent inappropriate CAD activation, particularly in cells where ICAD-S is the dominant form of ICAD protein.

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death leading to the elimination of damaged, harmful, or unwanted cells in a wide range of organisms (1, 2). DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation are two characteristic features of apoptosis in most cells (1, 3). The main nuclease responsible for DNA fragmentation is CAD/DFF40/CPAN3 (caspase-activated DNase/DNA fragmentation factor 40 kDa/caspase-activated nuclease) (4–7), although in some systems, endonuclease G might also contribute (8) (for an alternative view, see Ref. 9). In addition, CAD is required for the completion of apoptotic chromatin condensation (6, 10, 11). Apoptotic chromatin condensation can be divided into two stages. During stage I, chromatin condenses against the periphery of the nucleus. Later, during stage II chromatin condensation, individual apoptotic bodies are formed (11).

In cells, CAD nuclease is associated with its inhibitory chap-erone ICAD/DFF45 (DNA fragmentation factor 45 kDa) (5, 6, 12), which is now known as ICAD-L. ICAD-L is a mandatory chaperone that must be present during the translation of CAD, as the CAD polypeptide formed in the absence of ICAD-L is unable to fold into an active conformation (4, 13). After completing its chaperone function in promoting the folding of CAD on the ribosome, ICAD-L remains bound, functioning as an inhibitor of CAD and preventing its activation. During apopto-sis, CAD is activated when ICAD-L is cleaved by caspase-3 (5, 12,14). Once CAD is released from the fragmented ICAD, two molecules of CAD form a homodimer, which cleaves the DNA (15).

There are two forms of ICAD protein in cells, ICAD-L/DFF-45 and ICAD-S/DFF35 (DNA fragmentation factor 35 kDa) (4, 5, 16), that result from alternative splicing of a single pre-mRNA (17). Most studies have focused on ICAD-L; and the function of ICAD-S remains obscure. ICAD-S does not appear to function as a chaperone for CAD folding, as it does not support the production of active CAD if it is expressed in ICAD-/- mouse embryo fibroblasts (18). Nevertheless, ICAD-S was able to work as an inhibitor for CAD in vitro (16,19). ICAD-S in rat neurons prevents CAD activation (20). However, no ICAD-L protein was detected in this system, making it unclear just how CAD had been chaperoned, how ICAD-S had become associated with CAD, and what its specific function in the cell might be. In addition, tissue-specific differences in the quantity of ICAD-L and ICAD-S have been observed (17, 20). Furthermore, recent studies show that the ratio of ICAD-L and ICAD-S can be regulated in a single cell type (21).

To better define the role of ICAD-S in CAD regulation, we constructed a single knock-out of ICAD and a double knock-out of ICAD plus CAD in chicken DT40 cells. The double knock-out was constructed starting with a CAD knock-out cell line described previously (11). We then constructed a humanized system in which human CAD (hCAD) was expressed in DT40 cells either alone or in combination with human ICAD-L (hICAD-L), human ICAD-S (hICAD-S), or both. This system recapitulated the normal regulation of apoptotic DNA fragmentation in the knock-out cells.

In this system, ICAD-L could efficiently act as an inhibitory chaperone for CAD, but ICAD-S on its own was not able to support the synthesis of active CAD. Nonetheless, ICAD-S could inhibit CAD after cleavage of ICAD-L, thus showing its inhibitor function in vivo. Our data therefore demonstrate that although CAD must be synthesized with the help of ICAD-L as a chaperone and inhibitor, later ICAD-L can be efficiently replaced by ICAD-S, which works as an inhibitor but not as a chaperone for CAD in vivo. Thus, ICAD-S may act as a buffer in certain systems to ensure that CAD is kept inactive until a sufficient burst of caspase activity is generated.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture

The chicken B cell lymphoma DT40 cell line was cultured at 39 °C in RPMI 1640 medium with L-glutamine (Invitro-gen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma) and 1% chicken serum (Invitrogen).

Targeted Disruption of the ICAD Gene

To construct the ICAD knock-out we isolated a phage containing chicken ICAD genomic region (GenBank™ accession number EF632343) through screening of a λ FIX II DT40 genomic library. We completely removed the 2.7-kb ICAD open reading frame in DT40 cell lines using a targeting vector containing a 2.1-kb 5′-arm and a 3.4-kb 3′-arm from the non-coding regions. A selection cassette flanked with loxP sites (22) was placed between the 5′ and 3′ ICAD noncoding regions in the targeting vector. For the first targeting, a cassette consisting of the puromycin resistance gene (puro) and the thymidine kinase (tk) gene flanked by mutant loxP sites (loxP-puro-tk-loxP cassette) was used. This was constructed by cloning the Herpes simplex virus tk gene from the plasmid pBT/SP-TK (gift of Adrian Bird) into the loxP-puro-loxP cassette in pLoxPuro vector (22). For the second targeting, a loxP-puro-loxP cassette lacking tk coding sequences was used.

The knock-out constructs were linearized before transfec-tion into DT40 cells. Stable cell lines were selected with 0.5 μg/ml puromycin (Calbiochem). After the first targeting, the loxP-puro-tk-loxP cassette was removed by Cre-recombinase expressed from transiently transfected vector pCAGGS-Cre (23). Following transfection, cells were diluted and grown for 6 -7 days to obtain individual colonies without drug selection. Next, cells were replica-plated in media with and without drug to identify clones that had lost the marker due to removal of loxP drug resistance cassette. Throughout the knock-out construction procedure, each step was confirmed by Southern blotting.

Isolation of Human ICAD-L and CAD cDNAs

Total RNA from HeLa cells was isolated, and 5 μg was used for first strand cDNA synthesis using the Superscript first-strand synthesis system for reverse transcription-PCR (Invitrogen). Next, specific primers (Sigma-Genosys, Pampisford, UK) forhCAD (5′-AGCT-CTAGAATGCTCCAGAAGCCC-3′, 5′-AGCAAGCTTTCAC-TGGCGTTTCCG-3′) and hICAD-L (5′-AGCTCTAGAATGG-AGGTGACCG-3′, 5′-AGCGAATTCCTATGTGGGATCCTG-3′) were used to amplify human cDNAs encoding hICAD-L and hCAD. hICAD-S was constructed in a PCR reaction using hICAD-L as a template and the following primers: 5′-ATAAGA-AGCGGCCGCATGGAGGTGACCGGG-3′ and 5′-ATGG-GCGGCCGCTCAGTGACCCTGGTTTCCGCCCACCTCCA-AATCCTGACTAGATAAGCTC-3′.

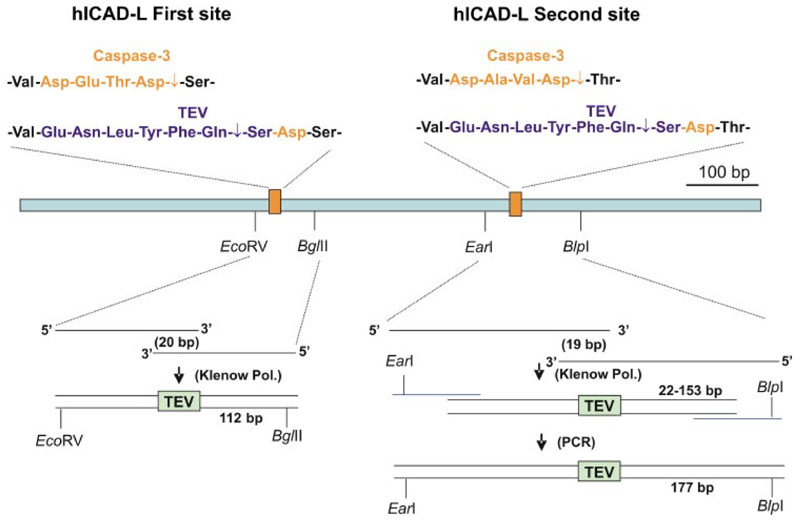

Constructing hICAD-L andhICAD-S with Two TEVSites (hICAD-L2TEV and hICAD-S2TEV)

The caspase-3 sites in hICAD-L and hICAD-S were replaced with TEV protease cleavage sites (24) using the strategy shown in Fig. 5. The insertion of the first TEV protease site was achieved after the synthesis with DNA Polymerase I Klenow fragment (New England Biolabs) using long oligonucleotides 5′-GCTT-GGATATCCCAAGAGTCCTTTGATGTAGAGAACCTCTA-CTTCCAGAGCGACAGCGGGGCAGGGTTGAAGTGG-3′ and5′-TGGACAGATCTTCTTTCAGCTGCCTGGCCACAT-TCTTCCACTTCAACCCTGCCCCGC-3′. To insert this fragment, an EcoRV site was engineered in the hICAD-L protein by point mutation without a resulting amino acid change using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The second site was partly synthesized with a DNA polymerase I Klenow fragment using oligonucleotides 5′-GCCTCTTGTCAAAGCAGGAAGAGTCCAAAGCTGCCT-TTGGTGAGGAGGTGGAGAACCTCTACTTCCAGAGC-GACACGGGTATCAGCAGAGAGACCTCCTCG-3′ and 5′-CCTGACTAGATAAGCTCAGCTCTGGAGCCTGCTTCT-CCCTCAGTGCAGTAAGGATGTGGCTCGCCAGCGCAA-CGTCCGAGGAGGTCTCTCTGCTG-3′. The reaction product required the further extension by PCR with primers 5′-GCCTCTTGTCAAAGCAGGAAGAGTCCAAAGCTGC-CTTTGG-3′ and 5′-CCTGACTAGATAAGCTCAGCTCTG-GAGCCTGCTTCTCCCTCAG-3′. hICAD-S2TEV was constructed using a strategy similar to that for hICAD-S in a PCR reaction using hICAD-L2TEV as a template.

Figure 5. Strategy for replacement of two caspase-3 sites in hICAD-L protein with two TEV protease sites.

Caspase-3 has two 4-amino acid recognition sites in hICAD. These sites were replaced by two 7-amino acid TEV protease recognition sites. For the first caspase-3 recognition site, a double-stranded DNA fragment encoding TEV protease recognition site synthesized using DNA polymerase I Klenow fragment from two long DNA oligos was introduced into the hICAD-L cDNA by replacement cloning. A similar approach for the second TEV recognition site yielded only a partial fragment. The desired fragment was obtained by extension using PCR with a long primer and then introduced into the hICAD-L cDNA by replacement cloning.

Annexin VAssay

The progress of cells into apoptosis upon its induction with 10 μm etoposide was assessed with Annexin-V-FLUOS staining kit (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

DNA Fragmentation and DNA Condensation Assay

DT40 cells were grown to a concentration of 5 × 105/ml prior to the addition of etoposide (10 μm) to induce apoptosis. Aliquots of cells harvested at 0,2, and 4 h were then used to isolate genomic DNA for fragmentation assay as described previously (25) or for microscopy analysis. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylin-dole. The slides were analyzed using a DeltaVision system (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA) as described previously (26).

Immunoblotting

Anti-DFF45/ICAD N-terminal antibody (Sigma) was used (1:500) to detect human ICAD protein. Monoclonal antibody to human α-tubulin (clone B512) from Sigma was used at a 1:4000 concentration as a loading control.

Assay for in Vitro Activation of CAD

Cytosolic extracts were prepared from DT40 cell lines in exponential growth. The cells were washed once in phosphate-buffered saline and then in KPM buffer (50 mM Pipes, pH 7.0, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithio-threitol). No protease inhibitors were added. The pellet was lysed by three freeze/thaw cycles and sonica-tion and then centrifuged at 55,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. Each reaction used 75 μg of extract protein/2 μg of plasmid DNA in CAD buffer (27) plus an ATP regenerating system (28). Caspase-3 (200 units, Calbiochem) or TEV protease (20 units, Invitrogen) were added to the reaction with the cell extract and plasmid DNA and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. After the reaction, plasmid DNA was isolated by phenol extraction and run on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Results

Construction of ICAD and ICAD/CAD Double Knock-outs in DT40 Cells

To study the function of ICAD and CAD in DT40 cells we constructed ICAD and ICAD/CAD double knock-outs, the latter starting with a CAD knock-out cell line described previously (11). DT40 cells are characterized by a high frequency of homologous recombination (29). The ICAD pre-mRNA is alternatively spliced in DT40 cells (21), producing ICAD-L and ICAD-S mRNAs similar to those described previously in mouse and human (17).

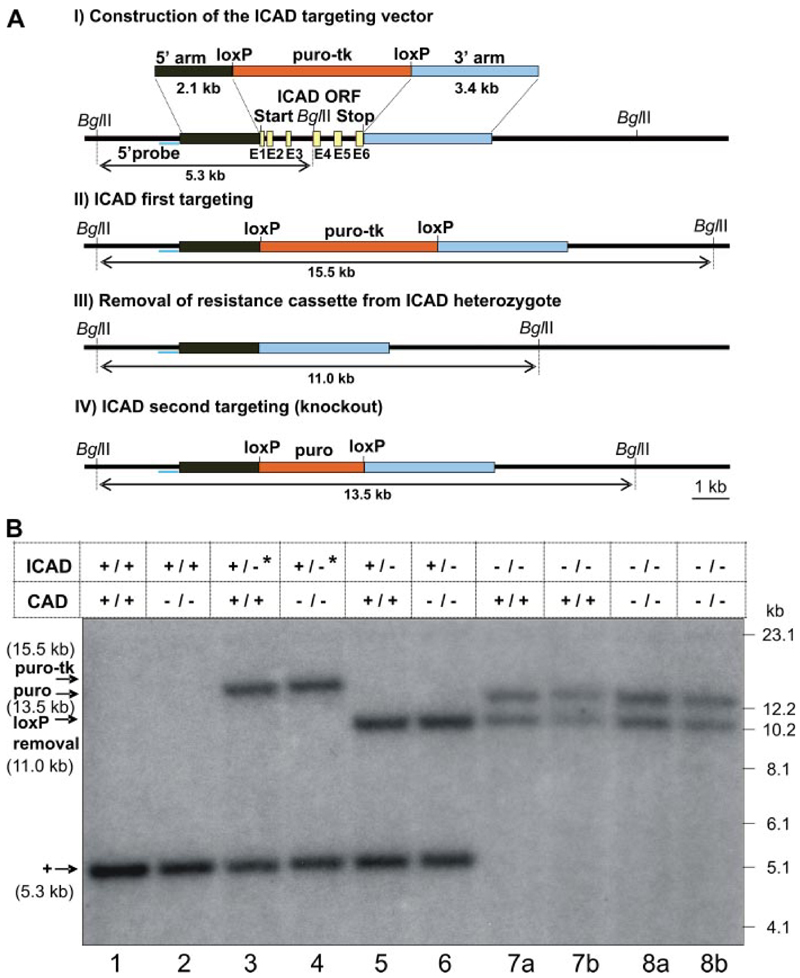

The ICAD gene (located on chromosome 21 at location 3.727.659-3.730.862) has 6 exons (Fig. 1 A ). We designed an ICAD knock-out strategy that results in complete removal of the ICAD open reading frame. To do this, we constructed a targeting vector with a selection cassette (loxP-puro-tk-loxP) inserted between ICAD 5′ and 3′ noncoding regions (Fig. 1A ). The cassette was flanked by mutant loxP sites to allow its removal by Cre-recombinase (22). The removal of the cassette allows marker recycling so that only a single knock-out vector was required to disrupt both alleles.

Figure 1. Structure and targeting of the DT40 ICAD gene.

A, structure of the chicken ICAD gene and the targeting strategy using a targeting vector with a resistance cassette flanked by ICAD 5′ and 3′ noncoding genomic regions. B, Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA prepared from the following: ICAD+/+ (lanes 1 and 2); ICAD+/-* (ICAD heterozygote with the puro/tk marker, lanes 3 and 4); ICAD+/- (ICAD heterozygote with puro/tk marker excised, lanes 5 and 6); and ICAD-/- (lanes 7 and 8). Genomic DNA (5 μg) was digested by BglII. The radioactive 5′-probe was located outside of the targeting vector. The figure shows data from two independent ICAD -/-- clones (lanes 7a and 7b) and two independent ICAD-/-/CAD-/- clones (lanes 8a and 8b).

After transfection with the ICAD targeting vector, clones (Table 1) were isolated using puro as a selectable marker. Correct targeting was recognized by Southern blot analysis with a 5′-external probe, using BglII-digested genomic DNA (Fig. 1B ). The probe recognized a 5.3-kb band corresponding to a DNA fragment from the intact ICAD allele (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 2 ) plus a 15.5-kb band corresponding to the integrated loxP-puro-tk-loxP cassette (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 4 ). The correct integration was further verified with an ICAD 3′-external probe (data not shown). As a result, heterozygous clones with the genotype ICAD+/-*/CAD+/+ and ICAD+/-*/CAD-/- were isolated (the asterisk indicates alleles containing the tk gene). The total targeting efficiency of homologous recombination was 32% for isolating these ICAD+/- heterozygotes.

Table 1. List of cell lines used and constructed in this study.

The “genotype” column refers exclusively to the genotypes of ICAD and CAD alleles. Stable cell lines expressing different versions of human ICAD and CAD proteins were constructed after the random integration of plasmid vectors. All proteins were expressed from SV40 promoters. The stable cell line used as the source for construction of each cell line is shown in the right column.

| Cell line no. | Stable cell line name | Genotype | Stably expressed proteins | Made from cell line no. (first column) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DT40 wild type | (ICAD +/+/CAD +/+) | ||

| 2 | CAD knock-out | (ICAD +/+/CAD −/−) | ||

| 3 | ICAD heterozygote with loxP-puro-tk-loxP cassette | (ICAD +/−/CAD +/+) (ICAD +/−/CAD −/−) | 1 and 2 | |

| 4 | ICAD heterozygote with removed loxP-puro-tk-loxP cassette | (ICAD +/−∗/CAD +/+) (ICAD +/−∗/CAD −/−) | 3 | |

| 5 | ICAD knock-out (clones a and b) | (ICAD −/−/CAD +/+) | 4 | |

| 6 | ICAD/CAD double knock-out (clones a and b) | (ICAD−/−/CAD−/−) (ICAD−/−/CAD−/−) | 4 | |

| 7 | hCAD | (ICAD −/−/CAD −/−) | hCAD | 6 |

| 8 | hCAD | (ICAD −/−/CAD −/−) | hCAD | 6 |

| 9 | hICAD-L:hCAD | (ICAD −/−/CAD −/−) | hICAD-L hCAD | 7 |

| 10 | hICAD-S2TEV:hICAD-L:hCAD | (ICAD −/−/CAD −/−) | hICAD-S2TEV hICAD-L hCAD | 9 |

| 11 | hICAD-S:hICAD-L:hCAD | (ICAD −/−/CAD −/−) | hICAD-S hICAD-L hCAD | 9 |

| 12 | hICAD-S:hCAD | (ICAD −/−/CAD −/−) | hICAD-S hCAD | 7 |

| 13 | hICAD-L2TEV:hCAD | (ICAD −/−/CAD −/−) | hICAD-L2TEV hCAD | 8 |

We originally planned to use the tk gene for negative selection to detect cassette removal by Cre-recombinase (30). However, the negative selection of DT40 cells with ganciclovir was not effective (data not shown).

To remove the loxP-puro-tk-loxP cassette, ICAD+/-*/CAD+/+ and ICAD+/-*/CAD-/- clones were transiently transfected with vector pCAGGS-Cre expressing Cre-recombinase. The clones with removed cassette were selected as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The 5′-external probe (Fig. 1B ) recognized the shift from 15.5 to 11.0 kb that occurred as a result of the removal of the 4.5-kb loxP-puro-tk-loxP cassette (Fig. 1B, lanes 5 and 6 ). As a result, clones with the genotype ICAD+/-/CAD+/+ and ICAD +/-/CAD-/- were isolated. The removal efficiency of the loxP-puro-tk-loxP cassette was 11%, so lack of the tk selection did not prove to be a significant impediment.

We used an ICAD targeting vector with a loxP-puro-loxP cassette for the second targeting. The resulting drug-resistant clones were confirmed by Southern blotting (Fig. 1B ). The 5′-external probe recognized the disappearance of the 5.3-kb band corresponding to the intact ICAD allele and appearance of the 13.5-kb band corresponding to the fragment bearing the integrated loxP-puro-loxP cassette (Fig. 1B, lanes 7 and 8 ). The targeting efficiency for the second ICAD allele was 11%.

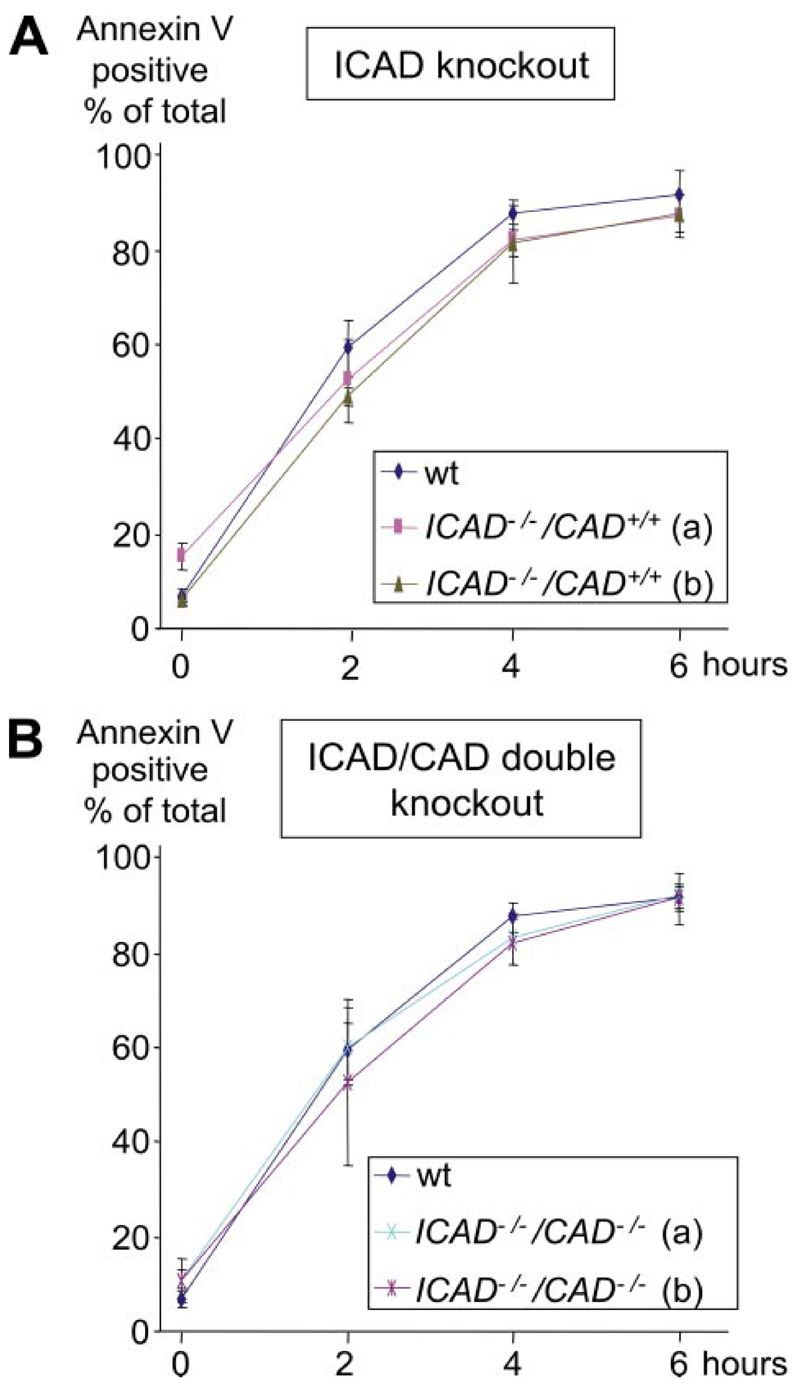

To determine whether apoptosis proceeds normally in the ICAD and ICAD/CAD double knock-out cell lines, both were tested for the presence of phosphatidylserine on the outer surface of the plasma membrane following treatment with etopo-side (31). Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane can be detected using the binding of Annexin V (32).

The percentage of Annexin V-positive cells was tested in the wild type, ICAD, and ICAD/CAD double knock-outs after the induction of apoptosis with etoposide (Fig. 2). There was a small background amount of Annexin V-positive cells at time 0 in all cell lines. The number of Annexin V-positive cells increased dramatically 2 h after apoptosis was induced by etoposide, with nearly half of the cells becoming apoptotic at this point. By 4 h most cells were Annexin V-positive, with only minimal changes in the cultures thereafter. No difference in the kinetics of phosphatidylserine exposure was observed among the wild-type, ICAD-/-, and ICAD-/-/CAD-/- cells, indicating that deletion of the ICAD gene, either singly or in combination with CAD has no effect on the kinetics of cell death induction. In preliminary experiments, the cell death rate measured by trypan blue exclusion appeared to be lower in ICAD and ICAD/CAD double knock-outs (data not shown). That is consistent with another study in which mouse thymocytes lacking DFF45/ICAD-L were reported to be more resistant to several proapoptotic stimuli (33–35) and suggests that CAD accelerates cellular demise after caspases have been activated.

Figure 2. Quantification of phosphatidylserine exposure on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane of DT40 cells by Annexin V staining.

This analysis was carried out for DT40 wild type (wt), ICAD -/-, and ICAD -/-/CAD-/-cell lines upon induction of apoptosis with 10μM etoposide. Samples were collected at 0,2,4, and 6 h, stained with Annexin-V-FLUOS, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The number of Annexin V-positive cells is indicated as a percentage of the total.A, Annexin V staining for ICAD knock-out clones a and b. B, Annexin V staining for ICAD/CAD double knock-out clones a and b. The same DT40 wild type data are shown in both panels. Experiments were repeated at least three times. S.D. is indicated by error bars.

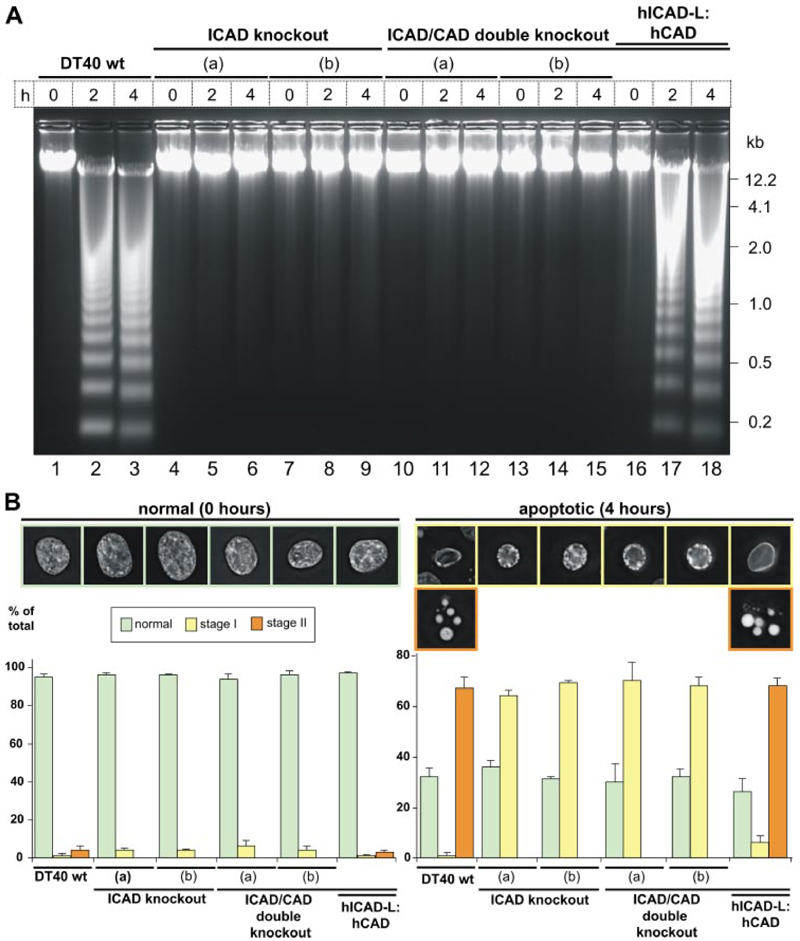

Oligonucleosomal DNA Fragmentation and Stage II DNA Condensation Are Absent in DT40 Knock-out Cells Lacking ICAD or ICAD Plus CAD

Oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation was undetectable in the ICAD knock-out and ICAD/CAD double knock-out cells upon induction of apoptosis with etoposide (Fig. 3A, lanes 4–15 ). In contrast, DNA fragmentation preceded efficiently in wild type DT40 cells (Fig. 3A, lanes 1-3 ). The CAD knock-out had been characterized previously in DT40 and shown to lack DNA fragmentation (11). This indicates that ICAD protein is absolutely required as a chaperone, which is consistent with results obtained in certain cells from ICAD knock-out mice (13).

Figure 3. DNA fragmentation and stage II chromatin condensation are absent in ICAD and ICAD/CAD double knock-outs following induction of apoptosis by 10 µM etoposide.

A, DNA fragmentation. Genomic DNA samples were collected at 0,2, and 4 h.Two ICAD-/- clones (clone a, lanes 4-6; clone b, lanes 7-9) and two ICAD-/-/CAD-/- clones (a, lanes 10-12; b, lanes 13-15) were analyzed. The stable cell line expressing hICAD-L:hCAD (lanes 16-18) was constructed by introducting the human cDNAs into the ICAD/CAD double knockout. B, images of cells before (0 h) and after (4 h) induction of apoptosis. DNA was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. The percentage of cells with normal, stage I, and stage II chromatin condensation is indicated. Data represent mean ± S.D. from a minimum of at least three independent experiments with over 300 cells counted for each.

Chromatin condensation was also affected in ICAD knockout and ICAD/CAD double knock-out cells (Fig. 3B ). Stage II chromatin condensation was absent in both knock-out cell lines upon induction of apoptosis. Only peripheral (stage I) chromatin condensation was observed. The knock-out pheno-type resembled the DT40 CAD knock-out characterized previously (11). The induction of apoptosis with etoposide for longer than 4 h did not result in DNA fragmentation or stage II chromatin condensation in any of these knock-out cell lines (data not shown). Therefore, CAD nuclease is required for stage II DNA condensation in DT40 cells, and stage I DNA condensation must be driven by another mechanism.

Human ICAD and CAD Proteins Can Rescue the DNA Fragmentation Phenotype of DT40 ICAD-/-/CAD-/- Cells

To test whether ICAD/CAD function as an independent module for chromatin processing in apoptosis, as suggested by current models, we used the ICAD/CAD double knock-out cells to construct humanized DT40 cell lines expressing human ICAD and CAD (Table 1). DNA fragmentation and stage II chromatin condensation upon induction of apoptosis were completely rescued in ICAD/CAD double knock-out cell lines expressing hICAD-L and hCAD (Fig. 3A, lines 16-18, and B ). This humanized cell line provided the basis for our further studies of the role of ICAD-S in CAD regulation.

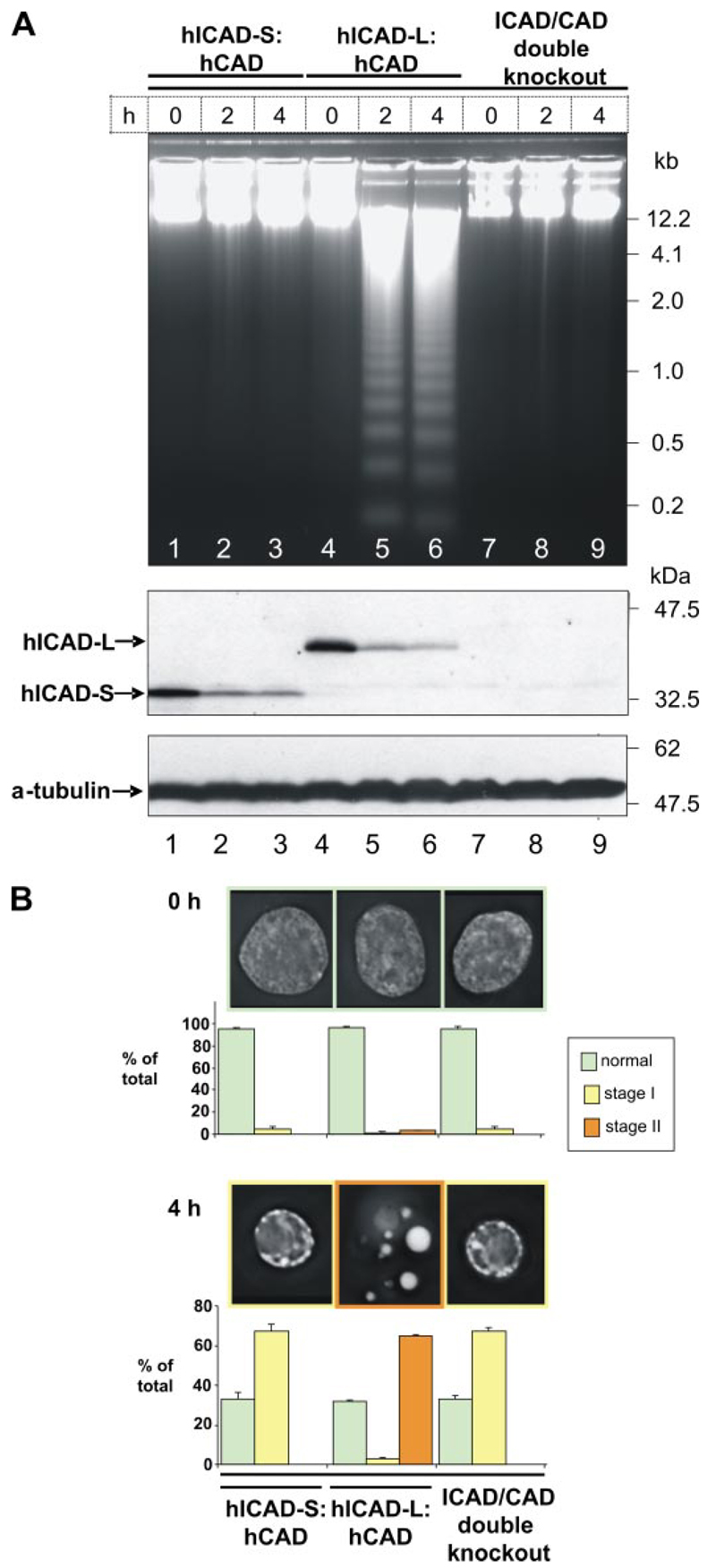

ICAD-S Does Not Work as a Folding Chaperone for CAD in Vivo

Given that hICAD-L plus hCAD could reconstitute the DNA destruction system in DT40 ICAD-/-/CAD-/- cells, we asked whether a similar rescue could be obtained using hICAD-S in place of hICAD-L (Table 1). After the induction of apoptosis by etoposide, hICAD-S was cleaved in these cells (Fig. 4A, lanes 1-3 ). However, no DNA fragmentation could be detected in these cell lines (Fig. 4A, lanes 1-3 ). Furthermore, chromatin condensation did not proceed beyond stage I, with small balls of chromatin distributed around the nuclear periphery (Fig. 4B ). Therefore, hICAD-S cannot replace hICAD-L as a chaperone in vivo for the folding of active CAD.

Figure 4. hICAD-L, but not hICAD-S, supports the production of active hCAD in vivo.

A, apoptosis was induced by 10 μM etoposide in stable cell lines expressing hICAD-S:hCAD (lanes 1-3) and hICAD-L:hCAD (lanes 4-6) in the chicken ICAD-/-/CAD-/- background. Upper panel, genomic DNA was isolated at 0, 2, and 4 h after induction of apoptosis. Middle panel, cleavage of hICAD-S and hICAD-L was detected with hICAD N-terminal antibody. B, images of cells before and after induction of apoptosis (0 and 4 h). Stage II chromatin condensation was absent in cells expressing hICAD-S: hCAD and present in cells expressing hICAD-L:hCAD. Data represent the mean ± S.D. from a minimum of at least three independent experiments with over 300 cells counted for each.

ICAD-S Inhibits CAD in Vivo

Importantly, ICAD is essential not only for the folding of active CAD but also for its subsequent inactivation until an appropriate apoptotic stimulus is detected. We therefore used the humanized cell system to test whether ICAD-S can act as an inhibitor of CAD in vivo (Table 1). To do this, we constructed a form of hICAD-S that was resistant to cleavage by caspases but could be cleaved at the same sites by the viral TEV protease.

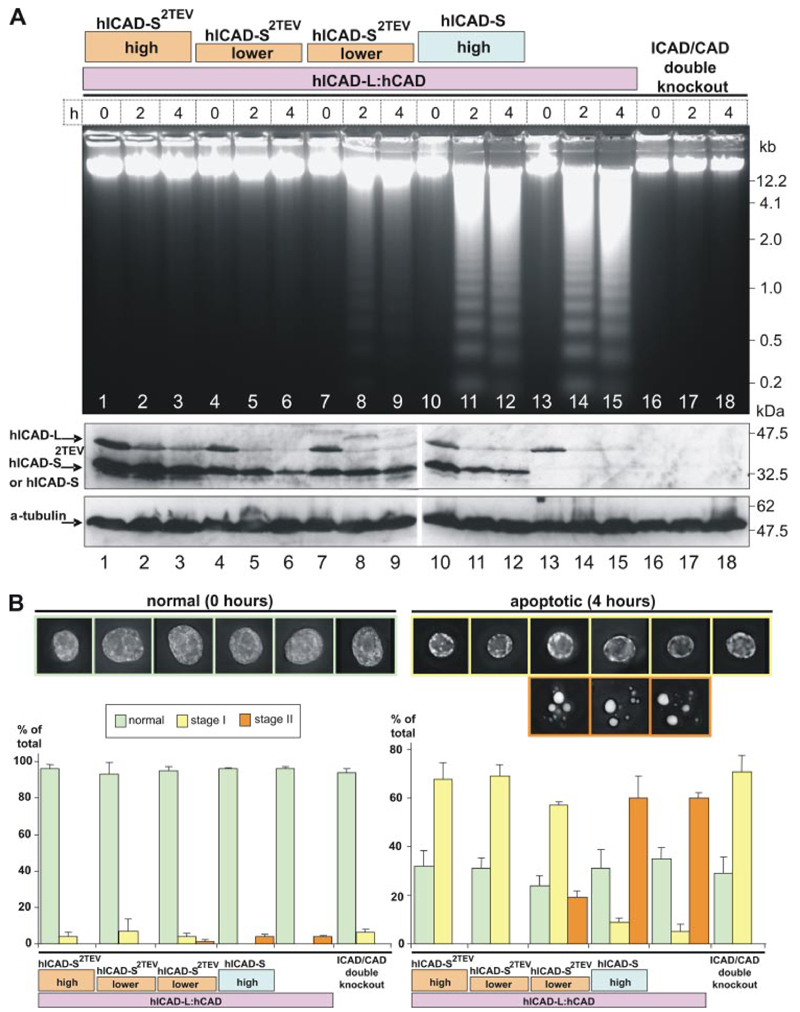

First, we constructed hICAD-L with two TEV sites, hICAD-L2tev (Fig. 5). Later, hICAD-S2TEV was synthesized from this by PCR using a long 3′-primer to generate the divergent truncated C terminus of ICAD-S. We then introduced hICAD-S2TEV into the humanized DT40 cells in which endogenous chicken ICAD and CAD had been replaced with hICAD-L and hCAD (Fig. 6A, lanes 1-9 ). In these cell lines, hICAD-L acts as a folding chaperone and inhibitor for hCAD. Treatment of these cell lines with etoposide resulted in activation of the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis, leading to caspase activation and cleavage of hICAD-L but not hICAD-S2TEV (Fig. 6A, lanes 1-9 ). Thus, if hICAD-S2TEV can bind and inhibit hCAD in vivo, these cells should fail to show any activation of CAD nuclease.

Figure 6. ICAD-S can inhibit CAD in vivo.

Stable cell lines expressing different levels of hICAD-S2TEV were constructed starting with the humanized cell line expressing hICAD-LhCAD in the ICAD/CAD double knockout. A, genomic DNA was isolated at 0,2, and 4 h after induction of apoptosis (top). The status of hICAD-L and hICAD-S2TEV was monitored by immunoblotting. hICAD-Lbut not hICAD-S2TEV was cleaved by caspasein vivo during the induction of apoptosis. One of the cell lines had a high levelofhICAD-S2TEV(lanes 1–3).Two other cell lines had a lower level of hICAD-S2TEV (lanes 4-9). A cell line expressing high level of caspase-cleavable hICAD-S was used as a control (lanes 10-12). B, images of cells before and after induction of apoptosis (0 and 4 h).DNA was stained with4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Histograms show the percentage of cells with normal, stage I, and stage II chromatin condensation. The experiment was done at least three times with over 300 cells counted for each independent experiment. Data represent the mean ± S.D. from a minimum of at least three independent experiments with over 300 cells counted for each.

Indeed, after induction of apoptosis in the humanized cells expressing hICAD-S2TEV, hCAD activation was prevented (Fig. 6A, lanes 1-9 ). In clones expressing high levels of hICAD-S2TEV no evidence of DNA fragmentation or apoptotic body formation was observed (Fig. 6A, lanes 1-3, and B ). More variable results were obtained in cell clones expressing lower levels of hICAD-S2TEV. In one such cell line, no DNA fragmentation was observed (Fig. 6A, lanes 4-6 ). In a second hICAD-S2TEV-expressing clone, low levels of DNA fragmentation could be observed (Fig. 6A, lanes 7-9 ), and apoptotic bodies were formed, albeit ~3-fold less efficiently than in the “wild type” humanized cells expressing only hICAD-L plus hCAD (Fig. 6B ). There was no obvious difference in the levels of hICAD-S2TEV protein in these two cell lines, so the explanation for the difference is not clear. Importantly, in all cell lines expressing higher levels of hICAD-S2TEV, hCAD activation was completely abolished.

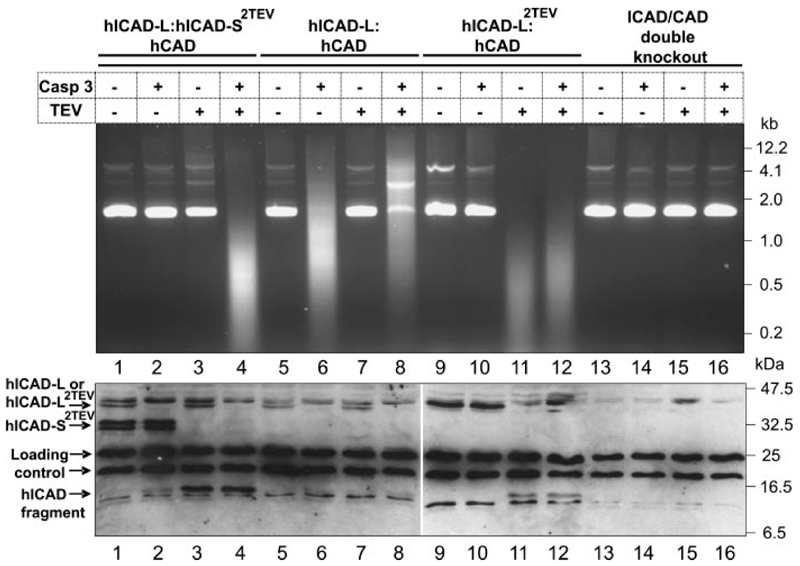

TEV Protease Cleaves ICAD-S2TEV in Vitro and Releases Active CAD

An in vitro experiment confirmed that both hICAD-L and hICAD-S can efficiently perform the function of inhibiting hCAD and that cleavage of both inhibitors is required for hCAD activation. In this experiment, we prepared extracts from humanized DT40 cells in which endogenous ICAD and CAD had been replaced by hICAD-S2TEV plus hICAD-L and hCAD (Fig. 7, lanes 1–4). In those extracts, added caspase-3 selectively cleaved ICAD-L but not ICAD-S2TEV, whereas added TEV selectively cleaved ICAD-S2TEV but not ICAD-L. Using this system, we observed CAD activation only when both caspase-3and TEV were added to the extracts (Fig. 7, lane 4 ).

Figure 7. hCAD is activated in vitro after the cleavage of hICAD in non-apoptotic extracts.

Extracts were prepared from stable cell lines expressing hICAD-S2TEV:hICAD-L:hCAD (lanes 1–4), hICAD-L:hCAD (lanes 5–8), and hICAD-L2TEV:CAD (lanes 9–12) in the ICAD/CAD double knock-out (lanes 13–16) background. Plasmid DNA was added to each reaction mixture either alone or together with caspase-3, TEV protease, or both. Plasmid DNA was degraded in reactions where hCAD was released as a result of hICAD cleavage.

In a control experiment, we prepared extract from a stable cell line expressing hICAD-L plus hCAD. In that extract, plasmid DNA was degraded when caspase-3 was added to the reaction mixture but not when TEV protease was added (Fig. 7, lanes 5–8 ). This confirms the well known activation of hCAD following hICAD-L cleavage by caspase-3.

To test whether the replacement of caspase-3 sites with TEV protease sites affected the ability of ICAD-L to act as a folding chap-erone function for production of active CAD, we constructed stable cell lines expressing hICAD-L2TEV plus hCAD in the absence of endogenous ICAD and CAD (Table 1). When cell-free extracts from those cell lines where analyzed in vitro, the addition of TEV protease was found to release active CAD, leading to the cleavage of plasmid DNA (Fig. 7, lanes 11 and 12 ). Therefore, replacing the two caspase cleavage sites of hICAD-L protein with TEV sites did not affect its chaperone and inhibitor function. Furthermore, this experiment reveals for the first time that under non-apoptotic conditions, specific cleavage of ICAD, is the only requirement for CAD activation in cell-free extracts.

As a final control, when either caspase-3 or TEV protease were added to cell-free extracts prepared from ICAD-/- / CAD-/- cells, no plasmid DNA degradation was observed. Therefore, neither protease activated another latent nuclease, such as endonuclease G, in the cell-free extracts.

Discussion

ICAD/DFF45 and CAD/DFF40/CPAN together comprise a module that is responsible for the destruction of the cellular DNA during classical apoptosis (4–7, 12). This module has been widely studied, but several key questions remain. These include the role of the ICAD splice variant ICAD-S in vivo, the role of other nucleases such as endonuclease G in DNA cleavage during apoptosis, and the role of other molecules including nucleophosmin/B23 and CIIA as “back-up” inhibitors of CAD in vivo. To address these questions, we constructed a humanized system in which the ICAD and CAD genes of chicken DT40 cells were deleted and the function of the ICAD/CAD module restored by the expression of wild type and variant forms of human ICAD and CAD.

Chicken DT40 cells lacking ICAD, CAD, or both are deficient in DNA degradation and formation of apoptotic bodies during apoptosis induced by etoposide, but the other aspects of apoptosis appear to proceed with normal kinetics as shown previously in DT40 CAD (11), mouse ICAD (33), and mouse CAD knock-outs (36). These results confirm that CAD activity is required for full apoptotic chromatin condensation. It is possible that cleavage by CAD releases the DNA from local entanglements or associations with nuclear substructures that constrain the condensed DNA into bead-like domains in the absence of CAD activity. Interestingly, whatever these constraints may be, they must be located around the nuclear periphery, as even in the absence of CAD activity no condensed DNA was detectable in the interior of apoptotic DT40 cell nuclei.

Human ICAD-L and CAD proteins were able to rescue the pheno-type of the DT40 ICAD/CAD double knock-out. However, hICAD-S could not replace hICAD-L, thereby confirming an earlier observation that ICAD-S is unable to function as a chaperone to promote the folding of active CAD (18).

To test the role of ICAD-S as an inhibitor of CAD in vivo and in vitro, we created an allele of ICAD-S in which the two caspase cleavage sites had been replaced by TEV protease cleavage sites (ICAD-S2TEV). hICAD-S2TEV could completely abolish both DNA cleavage and stage II chromatin condensation following the induction of apoptosis in humanized DT40 cells expressing hICAD-L and hCAD. Thus, ICAD-S2TEV could bind to CAD, which had been liberated following the cleavage of ICAD-L and inhibited its nuclease activity. These results were further confirmed in an in vitro assay.

We originally designed this system to examine whether cleavage of ICAD in a non-apoptotic context in vivo would result in CAD activation and cell death. This approach was modeled on experiments in budding yeast in which TEV cleavage of cohesin component Scc1/Mcd1 released cells into anaphase (37). However, after almost 2 years of attempts using multiple vector systems for the expression of nuclear and cyto-plasmic TEV protease in DT40 cells, we were able to express TEV but could never demonstrate any cleavageofICAD-L2TEV. We do not know the reason for this lack of TEV cleavage in living DT40 cells, but it is unlikely to result from inaccessibility of the TEV sites, as both ICAD-L2TEV and ICAD-S2TEV were efficiently cleaved in cell extracts by exogenous TEV.

This system could also be used to ask whether DT40 cells contain activities in addition to ICAD that inhibit CAD. It has been proposed that nucleophosmin/B23 (38) and CIIA (39) can fulfill this role and modulate CAD function either in normal cells or during apoptosis. Inhibiting CAD could be one of several functions of B23 that would be expected to be lost once B23 is cleaved by caspase-3 in apoptosis (40). However, CIIA cleavage has not been reported in apoptosis.

To address the importance of these alternative inhibitors of CAD function, we expressed a caspase-resistant ICAD-L2TEV/CAD module in DT40 cells lacking endogenous CAD and ICAD. ICAD-L2TEV is competent as a folding chaperone for CAD, and active nuclease was released following its cleavage with exogenous TEV, providing the first example of caspase-independent CAD activation and confirming that ICAD cleavage is sufficient to activate CAD. B23 and CIIA lack consensus cleavage sites for TEV, and DT40 cells expressing TEV appear to grow normally.4 It therefore appears that DT40 cell extracts lack other proteins that can replace ICAD as inhibitors of CAD. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that other potential modulators of ICAD or CAD activity function in vivo but are too dilute in cell extracts to perform their function.

These studies suggest a possible role for ICAD-S as a “buffer” of inhibitor to stop the sporadic loss or cleavage of ICAD-L from resulting in destruction of the genomic DNA. This is possible because ICAD-S acts as an inhibitor but not a chaperone for CAD. ICAD-L cannot act as such a buffer because italso acts as a chaperone to promote the folding of active CAD. As a result, expression of higher levels of ICAD could simply allow the folding of higher levels of active CAD. ICAD-L and ICAD-S are ubiquitously expressed during mouse development (33). The ratio of ICAD-S and ICAD-L varies in different tissues and organs (17, 20) and can be regulated at the level of alternative splicing (21). Interestingly, in some tissues that are destined for long-term existence such as neurons, only ICAD-S is detected and not ICAD-L (20) (for contrasting results in human brain tissues see Ref. 41).

Our study leads to a view of the ICAD/CAD module as a three-part system with ICAD-L acting both as activator and inhibitor of CAD, whereas ICAD-S is held in reserve as a buffer that prevents accidental activation of CAD. The humanized DT40 cell system described here provides a useful asset for future studies of the role and regulation of the ICAD/CAD module in DNA degradation and chromatin condensation during apoptosis.

Acknowledgements

We thank Matthew A. Sims for ICAD genomic region analysis. We greatly appreciate the gift of pBT/SP-TK plasmid from Prof. Adrian Bird.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: CAD, caspase-activated DNase; ICAD, inhibitor of CAD; ICAD-L, ICAD-long splice variant; ICAD-S, ICAD-short splice variant; DFF, DNA fragmentation factor; CPAN, caspase-activated nuclease; TEV, tobacco etch virus; hICAD-S2TEV, human ICAD-S with two TEV sites replacing the two caspase cleavage sites; hICAD-L2TEV, human ICAD-L with two TEV sites; hCAD, human CAD; tk, thymidine kinase; puro, puromycin; Pipes, 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid.

A. V. Ageichik, unpublished observation.

References

- 1.Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Br J Cancer. 1972;26:239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobson MD, Weil M, Raff MC. Cell. 1997;88:347–354. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81873-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wyllie AH. Nature. 1980;284:555–556. doi: 10.1038/284555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enari M, Sakahira H, Yokoyama H, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Na-gata S. Nature. 1998;391:43–50. doi: 10.1038/34112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakahira H, Enari M, Nagata S. Nature. 1998;391:96–99. doi: 10.1038/34214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Li P, Widlak P, Zou H, Luo X, Garrard WT, Wang X. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8461–8466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halenbeck R, MacDonald H, Roulston A, Chen TT, Conroy L, Williams LT. Curr Biol. 1998;8:537–540. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)79298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li LY, Luo X, Wang X. Nature. 2001;412:95–99. doi: 10.1038/35083620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irvine RA, Adachi N, Shibata DK, Cassell GD, Yu K, Karanjawala ZE, Hsieh CL, Lieber MR. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:294–302. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.294-302.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samejima K, Earnshaw WC. Exp Cell Res. 1998;243:453–459. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samejima K, Tone S, Earnshaw WC. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45427–45432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. Cell. 1997;89:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Liu X, Scherer DC, van Kaer L, Wang X, Xu M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:12480–12485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McIlroy D, Sakahira H, Talanian RV, Nagata S. Oncogene. 1999;18:4401–4408. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woo EJ, Kim YG, Kim MS, Han WD, Shin S, Robinson H, Park SY, Oh BH. Mol Cell. 2004;14:531–539. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu J, Dong RP, Zhang C, McLaughlin DF, Wu MX, Schloss-man SF. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20759–20762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawane K, Fukuyama H, Adachi M, Sakahira H, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkin NA, Nagata S. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:745–752. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagase H, Fukuyama H, Tanaka M, Kawane K, Nagata S. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:142–143. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakahira H, Enari M, Nagata S. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15740–15744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen D, Stetler RA, Cao G, Pei W, O’Horo C, Yin XM, Chen J. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38508–38517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003906200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Wang J, Manley JL. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2705–2714. doi: 10.1101/gad.1359305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arakawa H, Lodygin D, Buerstedde JM. BMC Biotechnol. 2001;1:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Araki K, Araki M, Miyazaki J, Vassalli P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:160–164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrington JC, Dougherty WG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:3391–3395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korfali N, Ruchaud S, Loegering D, Bernard D, Dingwall C, Kaufmann SH, Earnshaw WC. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1030–1039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vagnarelli P, Hudson DF, Ribeiro SA, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Spence JM, Lai F, Farr CJ, Lamond AI, Earnshaw WC. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1133–1142. doi: 10.1038/ncb1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samejima K, Tone S, Kottke TJ, Enari M, Sakahira H, Cooke CA, Durrieu F, Martins LM, Nagata S, Kaufmann SH, Earnshaw WC. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:225–239. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wood ER, Earnshaw WC. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2839–2850. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winding P, Berchtold MW. J Immunol Methods. 2001;249:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cannon JS, Hamzeh F, Moore S, Nicholas J, Ambinder RF. J Virol. 1999;73:4786–4793. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4786-4793.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fadok VA, Voelker DR, Campbell PA, Cohen JJ, Bratton DL, Henson PM. J Immunol. 1992;148:2207–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koopman G, Reutelingsperger CP, Kuijten GA, Keehnen RM, Pals ST, van Oers MH. Blood. 1994;84:1415–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Wang X, Bove KE, Xu M. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37450–37454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas DA, Du C, Xu M, Wang X, Ley TJ. Immunity. 2000;12:621–632. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boulares AH, Zoltoski AJ, Yakovlev A, Xu M, Smulson ME. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38185–38192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100629200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawane K, Fukuyama H, Yoshida H, Nagase H, Ohsawa Y, Uch-iyama Y, Okada K, Iida T, Nagata S. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:138–144. doi: 10.1038/ni881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uhlmann F, Wernic D, Poupart MA, Koonin EV, Nasmyth K. Cell. 2000;103:375–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahn JY, Liu X, Cheng D, Peng J, Chan PK, Wade PA, Ye K. Mol Cell. 2005;18:435–445. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cho SG, Kim JW, Lee YH, Hwang HS, Kim MS, Ryoo K, Kim MJ, Noh KT, Kim EK, Cho JH, Yoon KW, et al. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:71–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chou CC, Yung BY. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:38–45. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masuoka J, Shiraishi T, Ichinose M, Mineta T, Tabuchi K. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:806–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb01165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]