Summary

The chromosomal passenger complex protein INCENP is required in mitosis for chromosome condensation, spindle attachment and function, and cytokinesis. Here, we show that INCENP has an essential function in the specialized behavior of centromeres in meiosis. Mutations affecting Drosophila incenp profoundly affect chromosome segregation in both meiosis I and II, due, at least in part, to premature sister chromatid separation in meiosis I. INCENP binds to the cohesion protector protein MEI-S332, which is also an excellent in vitro substrate for Aurora B kinase. A MEI-S332 mutant that is only poorly phosphorylated by Aurora B is defective in localization to centromeres. These results implicate the chromosomal passenger complex in directly regulating MEI-S332 localization and, therefore, the control of sister chromatid cohesion in meiosis.

Introduction

Sexually reproducing organisms need a specialized cell division, meiosis, to generate haploid cells to maintain diploidy after fertilization. During meiosis, two divisions give rise to four haploid gametes. In the first meiotic division—the reductional division—homologous chromosomes pair and then segregate from each other. Without an intervening S phase, the second meiotic division proceeds similarly to mitosis. The success of meiosis depends on specific regulation of the cell division machinery. Some components are common to mitosis and meiosis but are regulated differently in the two types of division. Other components function only in meiosis (McKee, 2004).

In both mitosis and meiosis, sister chromatids must physically associate with each other to biorient on the spindle. The sister chromatids are linked by the cohesin complex, and, in mitosis, this cohesion is released at the metaphase-anaphase transition after cleavage of the Scc1/Rad21 subunit (Uhlmann et al., 2000).

Specialized features are required in meiosis I to facilitate homolog segregation and to ensure that sister chromatid segregation is deferred until meiosis II (Petronczki et al., 2003). In most organisms, homologs are linked by chiasmata, sites at which homologs have recombined. The sister kinetochores of each chromosome act as a unit, attaching to the same spindle pole and ensuring that both sister chromatids of each homo-log migrate to the same pole in anaphase I. To coordinate proper segregation, cohesion is lost in a stepwise manner. Cohesion distal to the chiasmata is lost in ana-phase I, allowing homologs to separate (Buonomo et al., 2000), but cohesion between the centromeres of the sister chromatids is preserved until the onset of anaphase II to guarantee accurate segregation of sister chromatids (for a review, see Petronczki et al., 2003). Retention of cohesion at the centromere requires the Drosophila MEI-S332 protein, the founding member of a class of protective proteins, now known as Shugoshins (Kerrebrock et al., 1995). Yeast Shugoshin proteins appear to act by preventing cleavage of the Rad21 meiotic paralog, Rec8, at the metaphase I-anaphase I transition (Katis et al., 2004; Kitajima et al., 2004; Marston et al., 2004; Rabitsch et al., 2004). Similarly, human Shugoshin ensures that cohesin does not prematurely dissociate from mitotic centromeres (McGuinness et al., 2005).

The chromosomal passenger complex plays essential roles in mitosis and cytokinesis (Carmena and Earn-shaw, 2003; Vagnarelli and Earnshaw, 2004), including chromosome condensation, biorientation of kineto-chores, stability of the bipolar spindle, and central spindle formation. Four members of the complex have been identified: Aurora B (Adams et al., 2000, 2001a; Schumacher et al., 1998; Terada et al., 1998), INCENP (Inner Centromere Protein) (Cooke et al., 1987), Survivin (Carvalho et al., 2003; Skoufias et al., 2000; Uren et al., 2000), and Borealin/Dasra-B (Gassmann et al., 2004; Sampath et al., 2004). Aurora B is a member of a highly conserved family of Ser-Thr kinases that are key mitotic regulators (Carmena and Earnshaw, 2003). The other members of the complex regulate the kinase activity and target it to its different cellular substrates. INCENP binds Aurora B (Adams et al., 2000) through a highly conserved domain called the IN-BOX (Adams et al., 2000, 2001a; Honda et al., 2003). INCENP is phosphorylated by Aurora B and activates the kinase in a positive feedback loop (Bishop and Schumacher, 2002; Honda et al., 2003; Kang et al., 2001). Loss of INCENP function leads to mistargeting and loss of kinase activity (Adams et al., 2001b). INCENP binds microtubules in vitro (Wheatley et al., 2001) and has a defined centromere-targeting domain; thus, it has been suggested that INCENP targets Aurora kinase to subcellular locations at which its activity is required during cell division. In yeast, dephosphorylation of the INCENP homolog, Sli15, by Cdc14 is required for transfer of the complex to the central spindle (Pereira and Schiebel, 2003).

Much less is known about the roles of the chromo-somal passenger proteins in meiosis. In C. elegans, AIR-2/Aurora B localizes on chromatin distal to chias-mata in meiosis I, and, in air-2 RNAi embryos, the REC-8 on the distal region of the chromosomes remains undegraded, preventing the separation of homologs (Kaitna et al., 2002; Rogers et al., 2002). Because phosphorylation of Scc1 increases the efficiency of separase cleavage (Uhlmann et al., 2000), phosphorylation by AIR-2 was proposed to promote Rec8 degradation distal to chiasmata. Aurora B may also contribute, together with Plk1, to the release of cohesion between sister chromatid arms in mitotic prophase/prometaphase (Gimenez-Abian et al., 2004; Losada et al., 2002).

We have used two Drosophila mutants in the INCENP protein to define the role of the chromosomal passenger complex in the specialized behavior of sister centromeres during male meiosis, a system in which meiosis I chromosomes are naturally achiasmatic. During Drosophila male meiosis, homologous chromosomes pair, but no synaptonemal complex is detected (Ault et al., 1982) and recombination is absent (Morgan, 1912). The effects of incenp mutants on meiosis, the localization of INCENP protein, and its effect on MEI-S332 localization reveal what we believe to be a novel function of the chromosomal passenger complex: regulation of MEI-S332 localization and protection of centromeric chromatid cohesion during meiosis.

Results

DmINCENP Remains at Centromeres after the Metaphase-Anaphase Transition in Male Meiosis I

The chromosomal passenger complex shows a characteristic distribution in mitosis (for a review, see Carmena and Earnshaw, 2003; Vagnarelli and Earnshaw, 2004). It associates with chromatin during prophase, concentrates at centromeres in prometaphase, then transfers to the central spindle at anaphase onset.

INCENP behavior in Drosophila male meiosis exhibited several notable features. During meiotic prometaphase I and metaphase I, INCENP associated with chromatin and concentrated at centromeres as it does in mitosis (Figure 1A); however, at the transition to anaphase I, INCENP remained primarily associated with the centromeres (Figure 1B). In early anaphase I, only low levels of INCENP were detected on the central spindle microtubules; later the centromeric signals became weaker, and the protein spread over the chromosome arms. At that time, a subset of INCENP became associated with the central spindle (Figure 1B, arrow). INCENP remained associated with chromosomes through telo-phase I (data not shown).

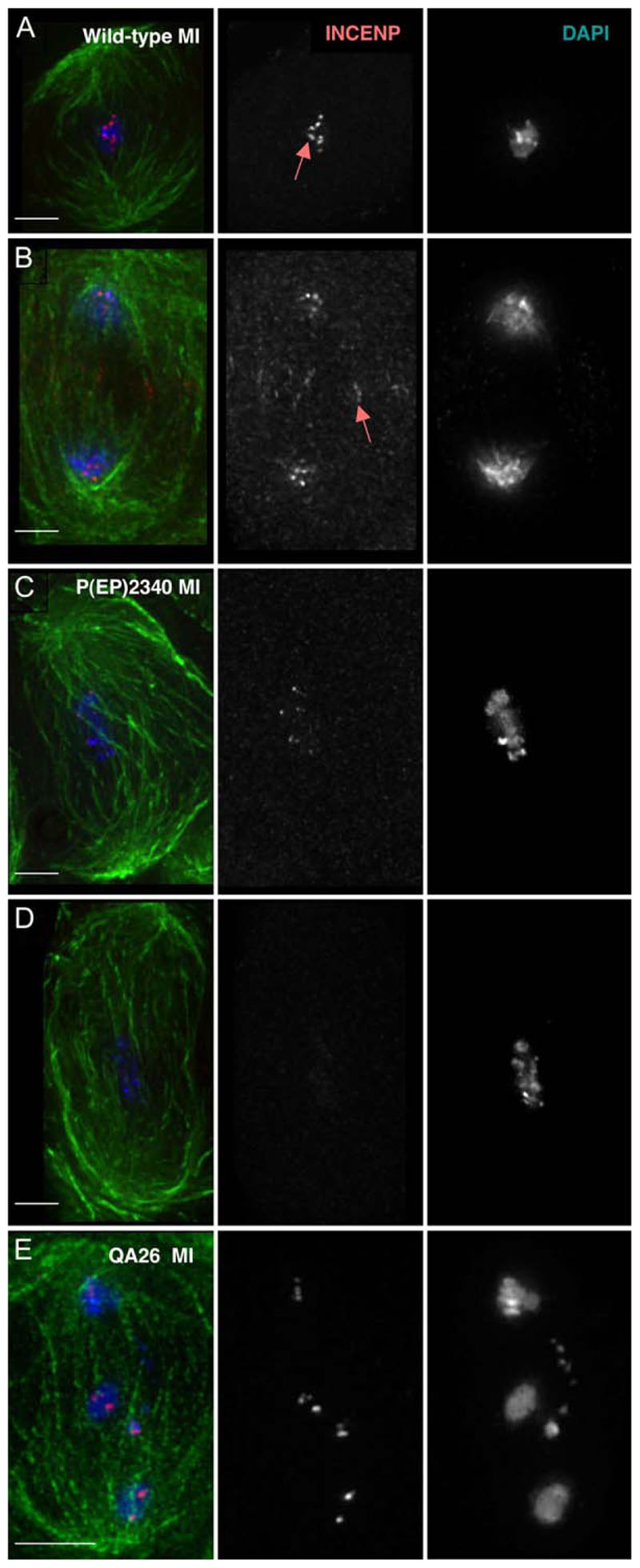

Figure 1. INCENP Protein Localization and Mutant Defects in Meiosis I.

(A) Wild-type metaphase I: INCENP concentrated on centromeres (arrow).

(B) Wild-type late anaphase I: INCENP remains on centromeres, and some protein transfers to the central spindle (arrow).

(C) P(EP)2340 prometaphase I: abnormally condensed bivalents, an abnormally long and wavy spindle, decreased levels of centromeric INCENP.

(D) Same as (C), but INCENP staining is undetectable.

(E) QA26 meiosis I: INCENP on centromeres and small segments of chromatin, the result of chromosome fragmentation or aberrant condensation.

Scale bars are 5 μm.

During the second meiotic division, INCENP again concentrated at centromeres through metaphase II, but then dispersed along the segregating chromatids at the onset of anaphase II (Figure 2A). The diffuse association with the chromosome arms in anaphase II was prominent relative to that in anaphase I. In addition, low levels of INCENP were associated with central spindle microtubules and with the cell cortex (Figure 2A, arrow).

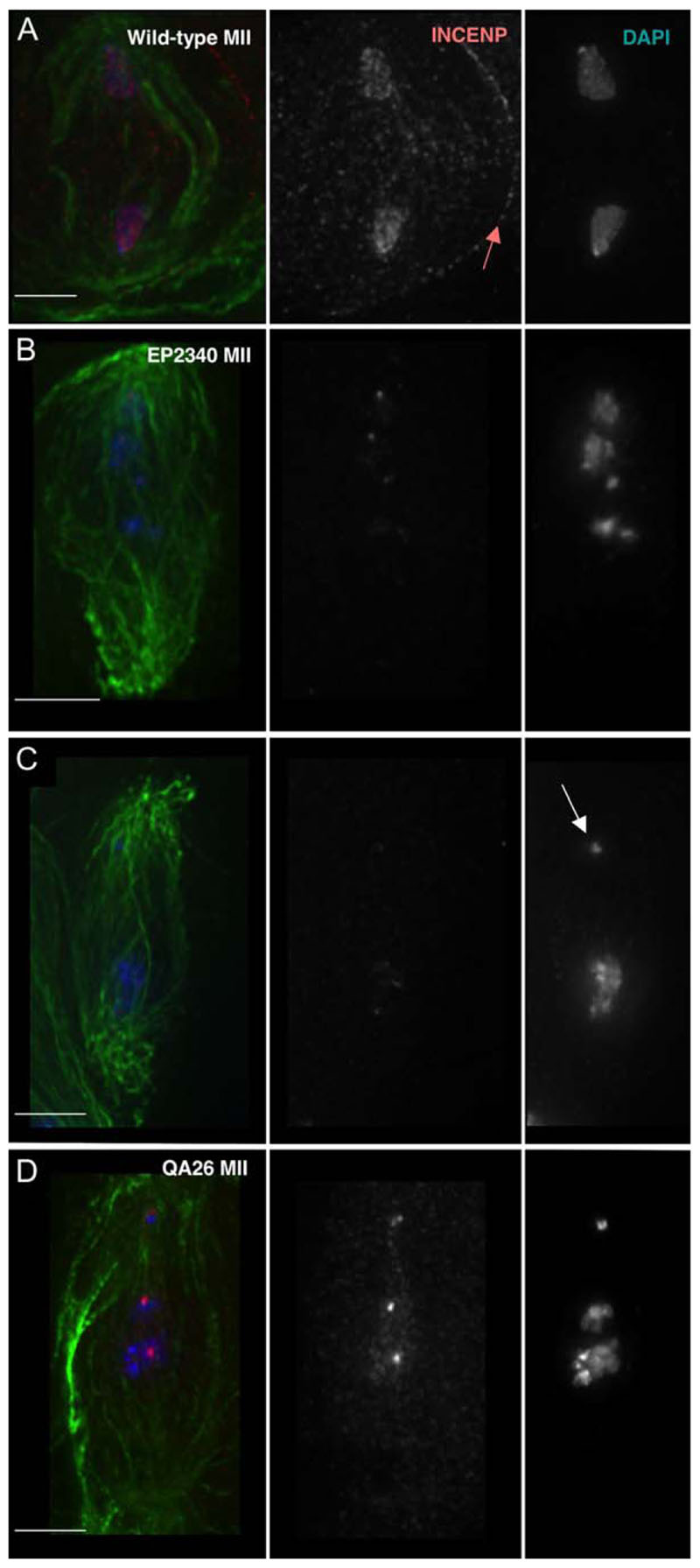

Figure 2. INCENP Protein Localization and Mutant Defects in Meiosis II.

(A) Wild-type anaphase II: INCENP associated with chromatin, central spindle, and cell cortex (arrow).

(B) P(EP)2340 prometaphase II-like figure: elongated spindle, decreased levels of centromeric INCENP, and chromatin masses aligned along the spindle.

(C) Meiosis II spindle showing the absence of INCENP staining and missegregation of chromosome 4.

(D) QA26 prometaphase II-like figure showing the absence of INCENP from some chromosomes and both copies of chromosome 4 at one pole.

Scale bars are 5 μm.

INCENP persistence on centromeres after the metaphase-anaphase I transition parallels the preservation of centromeric sister chromatid cohesion and is consistent with a possible role for the chromosomal passenger complex in this process. Maintenance of INCENP at centromeres through anaphase I is also seen in mouse spermatocytes (Parra et al., 2003).

The Female-Sterile Mutation QA26 Is Located in Dmincenp

The QA26 allele was generated in a screen for female-sterile mutations and was characterized as causing defects prior to cellularization of the embryo (Schupbach and Wieschaus, 1989). A combination of deficiency (see the Supplemental Experimental Procedures in the Supplemental Data available with this article online) and P element-induced male recombination mapping strategies (Chen et al., 1998) localized QA26 to a region including 43 genes, one of which was incenp (Adams et al., 2001b). PCR amplification and DNA sequencing from homozygous mutant genomic DNA revealed that QA26 is a point mutation that converts aspartic acid 675 to valine in the highly conserved IN-BOX, which is essential for the interaction between INCENP and Aurora B (Adams et al., 2000, 2001a; Honda et al., 2003).

QA26 homozygotes are viable, likely because INCENP retains some function. QA26 therefore provides an opportunity to examine the role of incenp in meiosis, which is not possible with stronger incenp alleles that prohibit the development of adult flies (Chang et al., 2006). QA26 mutant females completed meiosis without detectable defects, but there were aberrations in embryonic mitoses (data not shown). Homozygous mutant QA26 males had reduced fertility, suggestive of defects in male meiosis.

In addition to the QA26 allele, we made use of P(EP)2340, a P element insertion in the third exon of the incenp gene (Chang et al., 2006; Rorth, 1996; Tseng and Hariharan, 2002). Homozygous P(EP)2340 individuals die late in embryogenesis (Chang et al., 2006; Tseng and Hariharan, 2002). When overexpressed in dividing cell populations in the eye or posterior of the wing, P(EP)2340 results in a decrease in cell number and overall organ size (Tseng and Hariharan, 2002). Heterozygotes are viable, but they show reduced fertility; thus, this allele had a potential dominant defect in meiosis. Genetic and molecular assays demonstrated that the P element specifically affects incenp, and that its effects are not due solely to dosage reduction (Supplemental Data) (Chang et al. 2006).

The incenp Mutants Show Phenotypes Consistent with Disruption of Chromosomal Passenger Function

Both P(EP)2340 heterozygous or QA26 homozygous spermatocytes show abnormalities in the levels and localization of INCENP. In some instances, centromere-associated INCENP protein was low or undetectable in at least one bivalent pair (P(EP)2340: low in 27%, absent in 7% of meiosis I figures, n = 128, see Figures 1C and 1D; QA26: low in 34.3%, absent in 10.8%, n = 102). Although INCENP localized normally in meiosis I cells in many P(EP)2340 heterozygotes (40%) and QA26 homozygotes (27%, see Figure 1E), sometimes it was distributed along the chromosome arms in prometaphase/metaphase I rather than being restricted to the centromeres (see below). These effects were observed by using two antibodies that recognized opposite ends of INCENP.

We observed a variety of defects during meiosis I in both incenp mutants. These defects included cells in which unaligned chromosomes were distributed along the spindle (Figures 1C-1E), and others in which the four bivalents were not distinguishable or the chromosome morphology was abnormal (Figure 1D). In QA26, we saw small bits of chromatin that could be fragmented or aberrantly hypocondensed chromosomes (Figure 1E). In addition, we observed cells with more than four chromosomal masses in prometaphase I in both mutants. These extra chromosomal masses are likely due to failure in chromosome pairing or sister chromatid cohesion in meiosis, as the low level of premeiotic defects observed by orcein stain and phase contrast in QA26 mutants is not sufficient to explain them (see below and data not shown). In many meiosis II mutant spermatocytes, centromere-associated INCENP protein was reduced (P(EP)2340: low in 5%, Figure 2B, absent in 1.7%, Figure 2C; QA26: low in 16.5%, absent in 0%) or dispersed on the chromatin (P(EP)2340: 49.1%; QA26: 43%). INCENP localized normally in 44.2% of P(EP)2340 heterozygotes (n = 120) and 40.5% of QA26 homozygotes (n = 158). We observed chromatids randomly distributed along the spindle and unequal chromatid segregation (Figures 2B-2D), including asymmetric segregation of chromosome four as shown in Figure 2C.

Spermatocytes from both mutants also showed a range of defects in central spindle formation in anaphase and telophase of meioses I and II (data not shown). Pavarotti-KLP (Pav), a kinesin-like protein related to MKLP1 and required for central spindle stability (Adams et al., 1998), was absent or present at low levels on the central spindle in the mutant spermatocytes (data not shown).

These results demonstrate that INCENP function is required during Drosophila male meiosis for chromosome condensation, chromosome segregation, and central spindle organization. These phenotypes in incenp mutant spermatocytes are consistent with the mitotic phenotypes from depletion of INCENP or Aurora B in Drosophila S2 cells (Adams et al., 2001b; Giet and Glover, 2001). We pursued the possible role of INCENP in meiotic cohesion by additional quantitative cytological and genetic analyses of the chromosomal phenotype in QA26 male meiosis.

Disruption of incenp Function Leads to Premature Loss of Sister Chromatid Cohesion in Meiosis

Quantitative genetic analysis revealed that both incenp mutants underwent significantly increased levels of chromosome nondisjunction during meiosis. By crossing QA26 males to attached-X females, we detected progeny generated by nondisjunction in meiosis I (both X and Y chromosomes from the father) and those from nondisjunction during meiosis II (with two paternal X chromosomes). We also recovered progeny from sperm lacking sex chromosomes, which could have experienced nondisjunction in either meiotic division, as well as progeny from XXY sperm, which must have undergone nondisjunction in both divisions (Supplemental Data).

For 1,516 progeny from QA26 males, the rate of total nondisjunction was 15.8%, a 26-fold increase over the 0.6% nondisjunction measured for QA26/SM1 heterozygous siblings (Figure 3A). The recovery of exceptional sperm could result either from a failure of the sex chromosomes to disjoin or from premature separation of the sister chromatids followed by random segregation to the poles. The cytology of QA26 chromosomes supports precocious separation as one mechanism by which non-disjunction arises in this mutant (see below), but other effects may also be present.

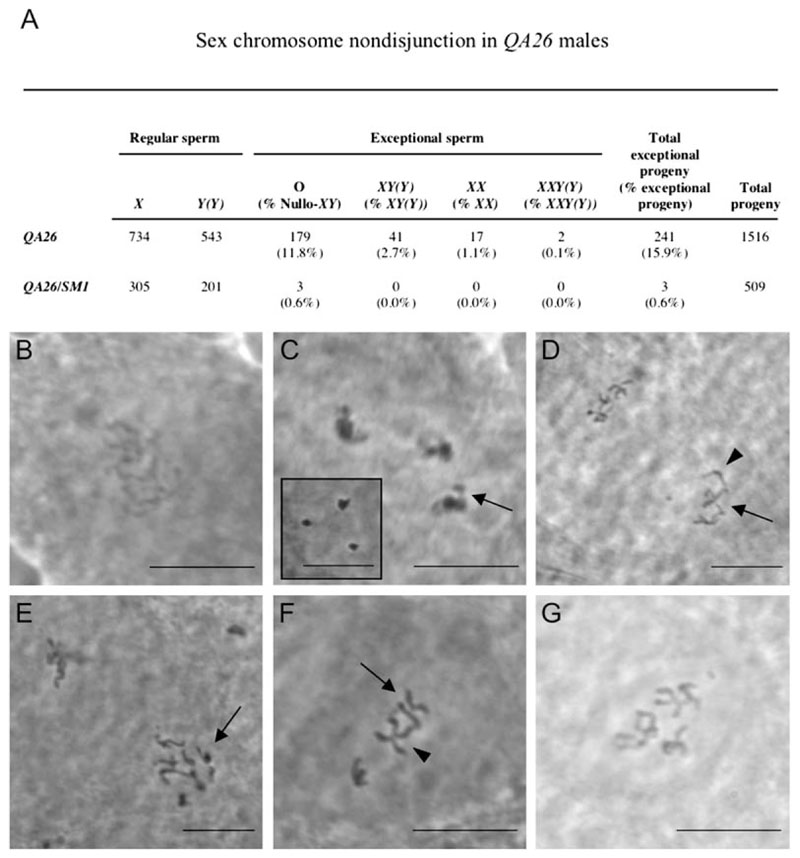

Figure 3. Meiotic Chromosome Cohesion and Condensation Defects in incenp Mutants.

(A) Mutations in incenp cause elevated nondisjunction during meiotic chromosome segregation.

(B) Defective prophase I chromosome condensation in a QA26 mutant spermatocyte.

(C) QA26 mutant prophase I: chromatid arms protrude from loosely packed bivalents (arrow). The inset shows the wild-type prophase I bivalent configuration.

(D) Wild-type anaphase I: at one pole, one major autosome (arrow) and the X chromosome (arrowhead) attached at their centromeres are indicated. This cohesion configuration is retained into prometaphase II.

(E) Anaphase I QA26 mutant: sister chromatids of all dyads at one pole (arrow) are precociously separated.

(F) Prometaphase II QA26 spermatocyte: sister chromatids of one dyad have lost cohesion (arrow) rather than retaining cohesion at the centromere, as seen in the adjacent dyad (arrowhead).

(G) Aneuploid prometaphase II QA26 mutant cell with more than the six expected major chromatids (see [D] and [F]), which is most likely the result of meiosis I nondisjunction. Scale bars are 10 μm.

The P(EP)2340 allele was tested for dominant effects on meiotic segregation. We performed crosses and counted progeny to score nondisjunction of the sex, second, and fourth chromosomes. Each of these tests revealed significantly higher rates of nondisjunction in P(EP)2340 heterozygotes than in controls (Supplemental Data).

Genetic evidence of nondisjunction in incenp mutants was confirmed cytologically by orcein staining of QA26 homozygous spermatocytes. This staining revealed abnormalities in both chromosome morphology and number (Figure 3). Prophase I figures with loosely packed and minimally condensed chromosomes were observed in 34% of QA26 spermatocytes as compared to 14% of wild-type (Figures 3B and 3C; 380 QA26 and 130 wild-type spermatocytes scored).

In addition to defects in chromosome condensation, QA26 spermatocytes displayed premature loss of sister chromatid cohesion. This was suggested by the appearance of prometaphase I bivalents that were compacted into blobs but had protruding arms that appeared to be single sister chromatids (Figure 3C). These figures were strikingly reminiscent of those present in ord mutants in which sister chromatid cohesion is prematurely released in prophase I (Miyazaki and Orr-Weaver, 1992), and they contrast with the tight packing of the bivalents normally seen in wild-type (Figure 3C, inset).

Premature loss of cohesion was unambiguous in anaphase I QA26 spermatocytes, where completely separated sisters were present at the poles (Figures 3D and 3E). Prometaphase II cells with separated sister chromatids were also observed (Figure 3F). Of those spermatocytes in which the chromosome arrangement permitted cohesion to be assessed, 34% of QA26 mutants had precociously separated sister chromatids (Figure 3F), compared to 7.8% in wild-type (90 QA26 and 65 wild-type scored). These data reveal that the centromeric cohesion that normally holds sisters together until the onset of anaphase II is lost prematurely in the QA26 mutant. The defects in chromosome condensation and sister chromatid cohesion likely led to missegregation, as aneuploid meiosis II spermatocytes were present (Figure 3G).

Together, this genetic and cytological analysis demonstrates that incenp plays a critical role in Drosophila male meiosis, and that it is required for proper chromosome segregation in both the reductional and equational divisions.

INCENP/Aurora B Functions Are Required for Normal Centromeric MEI-S332 Localization in Mitosis

The cytological and genetic analyses together reveal a requirement for INCENP function for cohesion at sister chromatid centromeres. We explored whether INCENP might affect the localization or function of MEI-S332, a member of the Shugoshin family of proteins required for the maintenance of sister chromatid cohesion in meiosis I (Lee et al. 2005). In both mitotic and meiotic chromosomes, MEI-S332 localizes within the functional centromere (Blower and Karpen, 2001; Lee et al., 2004; Lopez et al., 2000), where it contributes to sister chromatid cohesion. In mitosis, this role of MEI-S332 is not essential (LeBlanc et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2005).

On mitotic chromosomes, INCENP/Aurora B and MEI-S332 exhibited an overlapping distribution, but they did not coincide completely (Figures 4C and 4F). INCENP/Aurora B were enriched in the heterochromatin beneath kinetochores, whereas MEI-S332 appeared closer to the kinetochores.

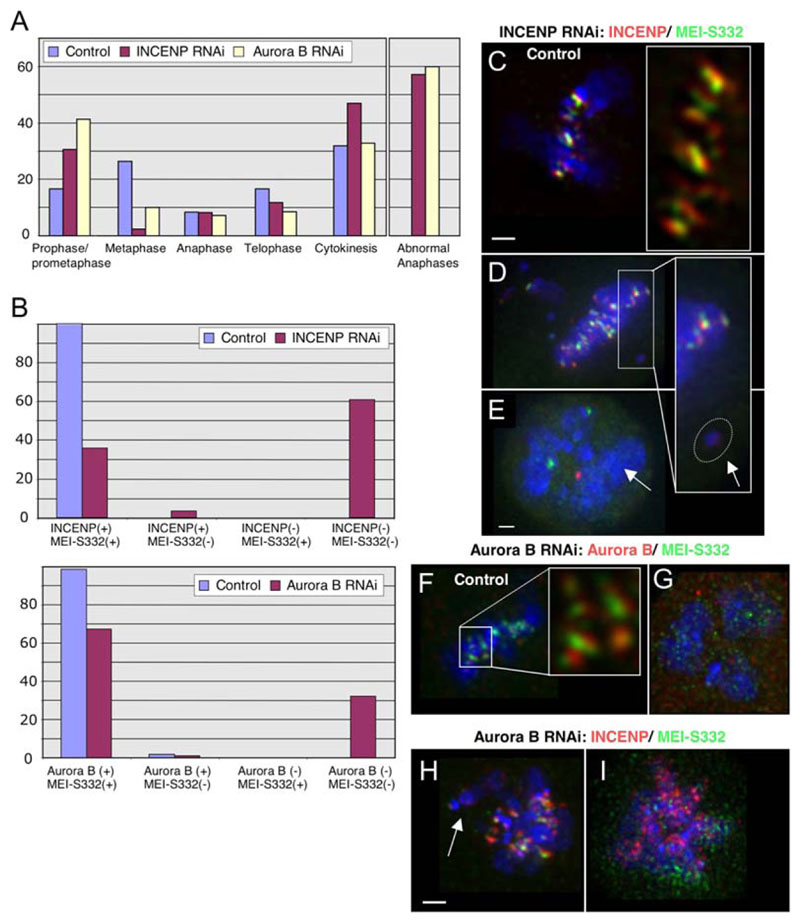

Figure 4. Loss of INCENP/Aurora B in Mitosis Correlates with Delocalization of MEI-S332.

(A) Distribution of mitotic phases in DmIN-CENP RNAi (red bar), DmAurora B RNAi (yellow bar), and control (blue bar) shows a reduction of the percentage of metaphases and an increase in the percentage of prometaphases (t = 48 hr after addition of dsRNA); the percentage of abnormal anaphase cells is shown separately (right).

(B) Analysis of the colocalization of MEI-S332 with INCENP in control and INCENP RNAi-treated cells (upper panel) and with Aurora B in Aurora B RNAi-treated cells (lower panel) (t = 48 hr). n > 300.

(C) Localization of MEI-S332 and INCENP in control S2 cells. The zoomed image at right shows that both proteins overlap partially, but that INCENP extends beneath MEI-S332. The scale bar is 5 μm.

(D) INCENP dsRNA-treated S2 cells showing unaligned chromosomes. INCENP and MEI-S332 are present on most centromeres. The Arrow points to a chromosome in which both proteins are absent.

(E) INCENP dsRNA-treated S2 cells showing the absence of both INCENP and MEI-S332 (arrow). The scale bar is 5 μm.

(F-I) Aurora B dsRNA-treated S2 cells. (F) Control metaphase cell; the zoomed image shows partial colocalization of Aurora B and MEI-S332 on centromeres. (G) Prometaphase cell with decondensed chromosomes showing the absence of both Aurora B and MEI-S332 from centromeres. (H) Prometaphase cell showing INCENP and MEI-S332 on some centromeres; the arrow points to an unaligned chromosome showing low levels of INCENP and undetectable MEI-S332. The scale baris 5 mm. (I) Prometaphase cell showing abnormal INCENP localization on chromatin and dispersed MEI-S332 staining.

To test whether INCENP is required for localization of MEI-S332 in mitosis, we used RNAi to deplete INCENP in S2 cells. A total of 48 hr after addition of INCENP dsRNA, cultures exhibited a prometaphase delay, as described after depletion of INCENP or Aurora B (Figure 4A) (Adams et al., 2001b). At this time point, 61% of mitotic cells in prometaphase/metaphase showed no INCENP staining, while 39% retained some INCENP staining (Figure 4B, upper panel).

We exploited the variable penetrance of the RNAi phenotype to examine the dependency of MEI-S332 centromeric localization on INCENP. We found that every mitotic figure with normal INCENP staining at centromeres was also positive for MEI-S332 staining, and that every cell without INCENP staining at centromeres also lacked MEI-S332 (Figure 4B, upper panel; Figure 4E). A small percentage of mitoses (3.6%) showed extremely decondensed chromosomes with very low levels of INCENP and undetectable MEI-S332 (Figure 4B, upper panel). Occasionally, an INCENP-positive cell contained individual chromosomes with low or undetectable INCENP signal at the centromeres. These chromosomes showed low or undetectable levels of MEI-S332 (Figure 4D).

To investigate further the role of the passenger complex in MEI-S332 localization, we also examined Aurora B-depleted cells. Again, in cells with normal Aurora B kinetochore staining, MEI-S332 was localized on centromeres. In cells with undetectable levels of Aurora B, MEI-S332 was aberrantly dispersed around the chromatin and in the cytoplasm (Figure 4B, lower panel; Figure 4G). Similar to the INCENP depletion, we observed cells in which the levels of both INCENP and MEI-S332 (Figure 4H) or Aurora B and MEI-S332 (data not shown) were low or undetectable only on a subset of chromosomes. As we reported previously (Adams et al., 2001b), in S2 cells in which Aurora B is depleted, INCENP associates with chromatin upon entry into mitosis, but it fails to concentrate on the centromeres during prometaphase/metaphase (Figure 4I). In these cells, MEI-S332 also failed to localize normally to centromeres (Figure 4I).

These experiments indicate that INCENP and/or Aurora B function is required for the stable localization of MEI-S332 at centromeres in mitosis. They also suggest that Aurora B phosphorylation of INCENP or MEI-S332 could contribute to maintaining MEI-S332 on centromeres.

INCENP Is Required for Normal MEI-S332 Localization at Centromeres in Meiosis

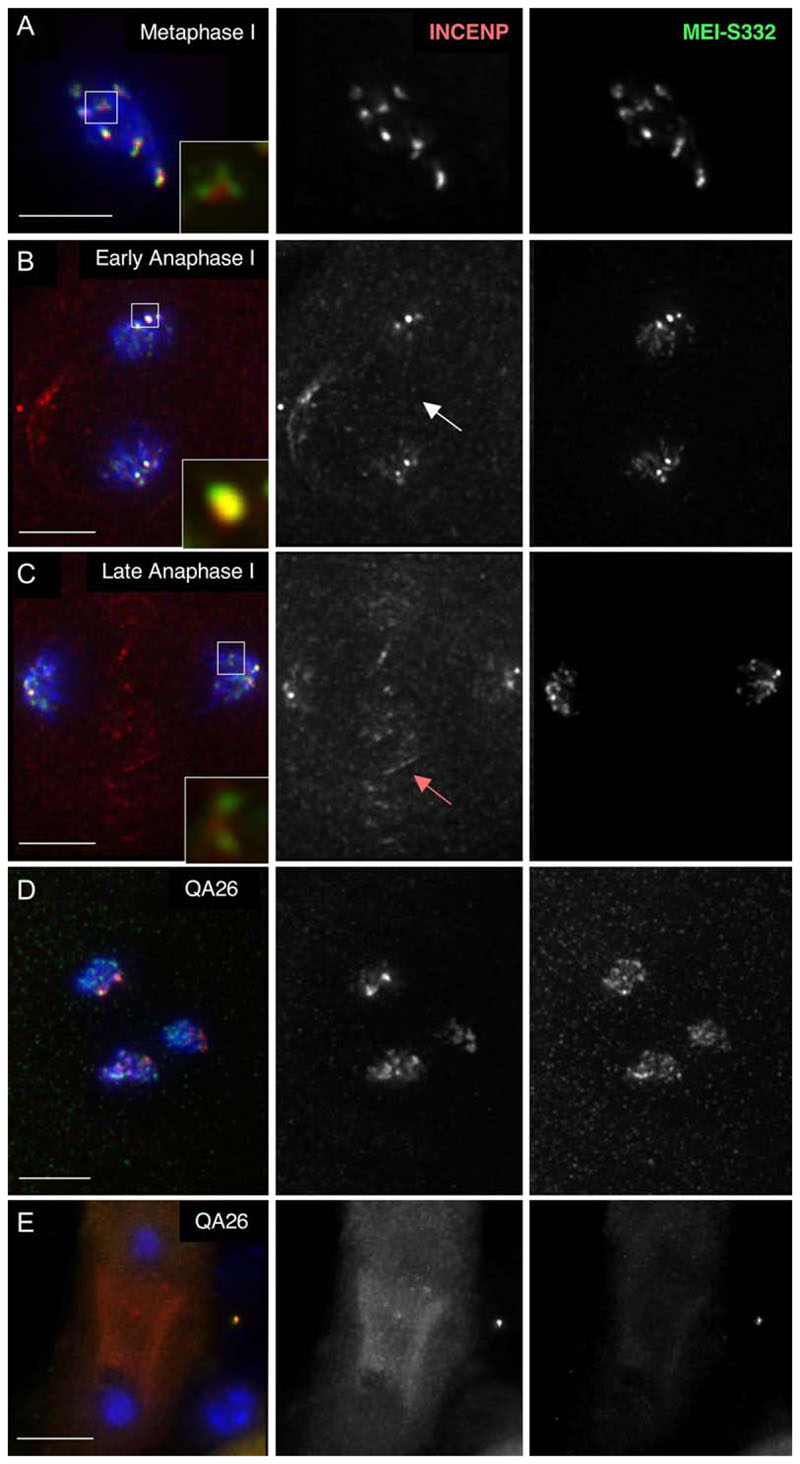

MEI-S332 is essential for proper chromosome segregation in meiosis; thus, we next investigated the distribution of INCENP and MEI-S332 during meiosis in wild-type and incenp mutant flies. INCENP and MEI-S332 colocalized at centromeres during wild-type male meiosis (Figures 5A-5C). In metaphase I, INCENP partially overlapped and linked the two sister kinetochore-associated MEI-S332 dots. Early in anaphase I, the two proteins appeared largely to overlap, but late in anaphase I, INCENP was concentrated in the heterochromatin linking sister kinetochores, and only partially overlapped with MEI-S332 (Figure 5C, inset). This is reminiscent of the relative distributions of INCENP and the Aurora B substrate MCAK during mitosis in mammalian cells.

Figure 5. Localization of INCENP and MEI-S332 Is Disrupted in QA26 Meiosis.

(A) Wild-type metaphase I: INCENP and MEI-S332 on centromeres. The inset shows INCENP staining partially overlapping and linking the two sister kinetochore-associated MEI-S332 dots.

(B) Wild-type early anaphase I: INCENP and MEI-S332 remain associated with the centromeres. The inset shows an overlap in the localization of the proteins. Arrow: absence of INCENP staining on the central spindle.

(C) Wild-type late anaphase I: INCENP remains associated with centromeres, but some protein is associated with chromatin and the central spindle (arrow: INCENP on the central spindle).

(D) QA26 meiosis I spermatocyte: INCENP and MEI-S332 are distributed diffusely on the chromosomes.

(E) QA26 anaphase I: both INCENP and MEI-S332 are absent from the chromosomes. Scale bars are 5 μm.

In QA26 homozygous males, we observed prometaphase I-like figures in which both MEI-S332 and INCENP proteins were not restricted to the centromere, but were dispersed along the chromosome arms (Figure 5D). This phenotype is consistent with defective interactions between INCENP and Aurora B (Adams et al., 2001b). In addition, we commonly observed meiotic figures in both QA26 homozygotes and P(EP)2340 heterozygous males in which MEI-S332 and INCENP were absent or reduced on one or more chromosomes (Figure 5E; Figure S1, see the Supplemental Data). This was particularly evident in mutant anaphase I cells (Figure 5E) and contrasted with wild-type cells, in which both proteins persisted at centromeres until anaphase II (data not shown). Together, these observations are consistent with INCENP being necessary for stable MEI-S332 localization at centromeres.

To determine whether INCENP and MEI-S332 have a mutual requirement for proper localization, we examined INCENP distribution in mei-S3324 spermatocytes. In each meiotic division, INCENP distribution was normal (data not shown). Because mei-S3324 flies lack detectable levels of MEI-S332 protein (Tang et al., 1998), we conclude that INCENP localization does not require MEI-S332.

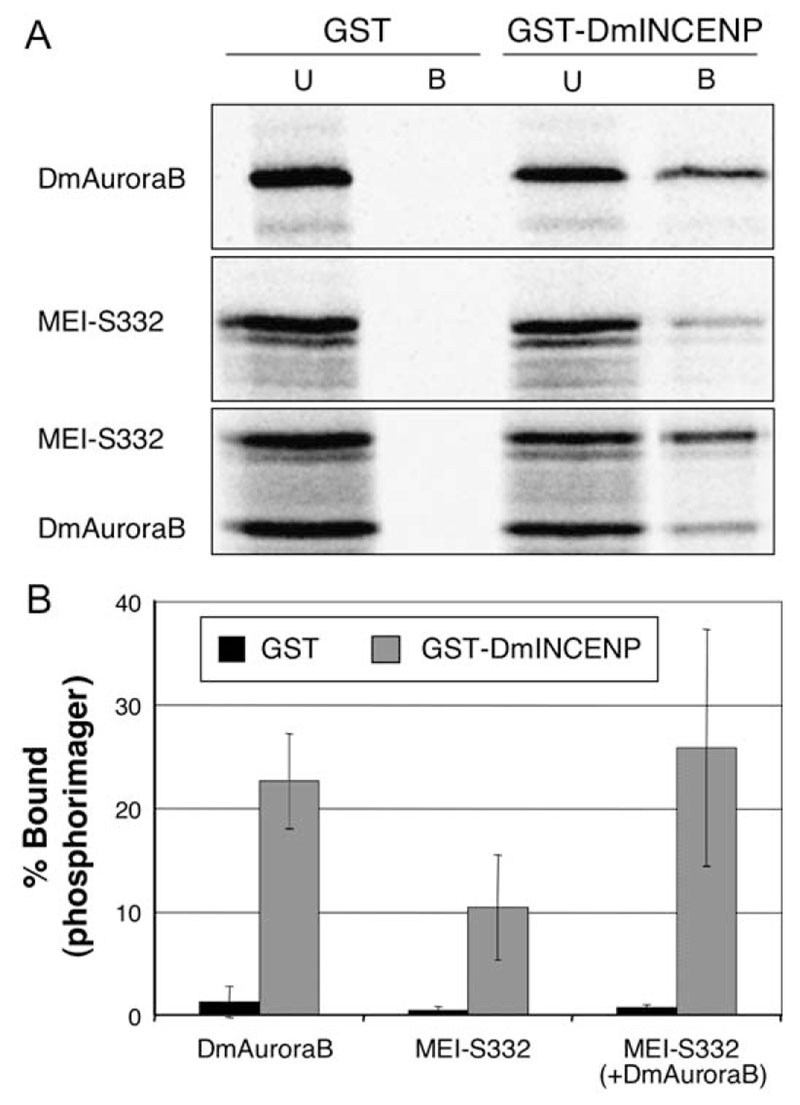

MEI-S332 Associates Directly with DmINCENP In Vitro

To elucidate the mechanism underlying the interaction between INCENP and MEI-S332, we next investigated whether MEI-S332 could bind DmINCENP in vitro. Bacterially expressed GST-INCENP was assayed for binding to in vitro-translated MEI-S332, DmAurora B, or a mixture of both proteins (Figures 6A and 6B). GST-DmINCENP interacted directly with MEI-S332 (Figure 6A), and binding of MEI-S332 was increased in the presence of DmAurora B (i.e., active kinase complex) (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. INCENP Binds MEI-S332 In Vitro.

(A) Proteins were translated in the presence of [35S]methionine and incubated with bacterially expressed GST-DmINCENP or GST bound to glutathione Sepharose beads. Bound (“B”) and unbound (“U”) fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were visualized by using a phosphorimager.

(B) Quantification of the binding experiment shown in (A). The bars represent the percentage of total protein bound to GST (black) or GST-DmINCENP (gray). Error bars show standard deviation.

MEI-S332 Is Phosphorylated by Aurora B In Vitro

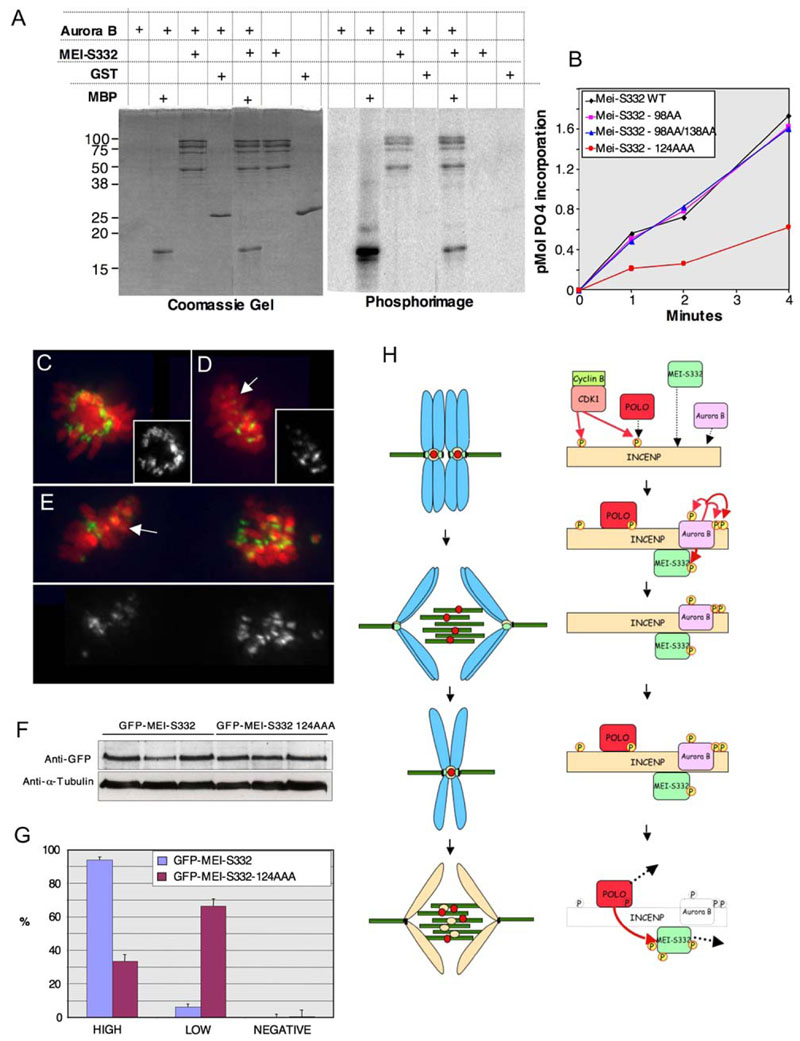

MEI-S332 is an excellent in vitro substrate of Aurora B kinase. When GST-MEI-S332 was incubated with recombinant bacterially expressed Xenopus INCENP/Aurora B, it was phosphorylated at levels comparable to a strong test substrate, myelin basic protein (MBP) (Figure 7A). Moreover, at similar concentrations, MEI-S332 could compete label away from MBP (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. Aurora B Phosphorylates MEI-S332 and Regulates Its Stable Association with Centromeres in Mitosis.

(A and B) INCENP/Aurora B phosphorylates MEI-S332 in vitro within residues 124–126 (A) The recombinant INCENP/Aurora B complex was incubated with [32P]ATP and the indicated substrate for 1 min, and incorporation of phosphate onto the proteins was visualized by autoradiography(right) and protein loading analyzed by Coomassie blue(left). MBP, myelin basic protein; GST, glutathioneS-transferase. (B) Timecourse of INCENP/Aurora B kinase activity (assayed as in [A]) by using wild-type MEI-S332 or the indicated phosphosite mutant.

(C–G) The MEI-S332-124AAA phosphorylation mutant does not stably associate with centromeres in mitosis. (C) High level of centromeric GFP-MEI-S332 in metaphase. (D) Reduced level of the phosphorylation mutant GFP-MEI-S332-124AAA on metaphase centromeres (arrow). (E) Microscope field showing a prometaphase cell with high levels of centromeric GFP-MEI-S332-124AAA and a metaphase cell with very reduced levels of mutant protein in most centromeres (arrow). In (C)–(E), the GFP staining alone is shown in gray. (F) Western blot showing levels of expression of the GFP-tagged proteins in three different transfection experiments. (G) Percentage of cells transfected with GFP-MEI-S332 or GFP-MEI-S332-124AAA showing normal levels of GFP signal on kinetochores (HIGH), lower than normal levels (LOW), or no signal (NEGATIVE). Error bars show standard deviation.

(H) Model of the role of INCENP in the regulation of MEI-S332 in meiosis. Left column: meiotic chromosome dynamics and the localization patterns of key regulatory proteins INCENP/Aurora B (orange/pink), MEI-S332 (green), and POLO (red). Right column: protein interactions at the kinetochore. In prophase I, CDK phosphorylates INCENP at the POLO binding site, promoting the targeting of POLO kinase to the kinetochore; INCENP targets Aurora B to the kinetochore; MEI-S332 is recruited to the kinetochore. Before the metaphase-anaphase I transition, Aurora B initiates its autoactivation backloop, phosphorylating INCENP and itself. The INCENP/Aurora B complex stabilizes centromeric MEI-S332 through direct binding and phosphorylation. At the onset of anaphase I, INCENP stays on the centromere, stopping MEI-S332 from being phosphorylated by POLO, and POLO transfers to the central spindle. During the metaphase-anaphase II transition, INCENP transitions off the centromere, redistributing over chromatin and transferring to the central spindle. POLO is free to phosphorylate MEI-S332, promoting its release from centromeres. POLO then transfers to the central spindle.

In general, bona fide in vivo substrates such as MCAK, MKLP1, and INCENP are phosphorylated by INCENP/Aurora B as efficiently as MBP (PTS data not shown).

Three regions of MEI-S332 contain putative Aurora B consensus sites (RX S/T). Each site includes two or more consecutive serine residues (98S 99S, 124S 125S 126S, 138S 139S). Three mutant MEI-S332 proteins in which the consecutive serines in each putative site were mutated to alanines were engineered and purified from E. coli. Of these, MEI-S332S124,125,126A was a poor substrate for Aurora B kinase in vitro when compared to MEI-S332wt, MEI-S332S98,99A, or MEI-S332S138,139A (Figure 7B). Because residues 124–126 constitute the only Aurora B target site that diminishes phosphorylation when mutated, we conclude that Aurora B most likely phosphorylates MEI-S332 within these residues.

The MEI-S332-124AAA Phosphorylation Mutant Does Not Stably Associate with Centromeres in Mitosis

To analyze the role of Aurora B phosphorylation of MEI-S332 in vivo, we studied the behavior of the GFP-tagged MEI-S332S124,125,126A phosphorylation mutant (MEI-S332-124AAA) in transiently transfected S2 cells. Both wild-type and mutant proteins showed similar levels of expression and stability by Western blot (Figure 7F). We found high levels of centromeric wild-type GFP-MEI-S332 (Figure 7C) in 94% of prometaphase/meta-phase cells (Figure 7G; n > 400 per experiment). In contrast, only 33.3% of prometaphase/metaphase cells showed high levels of GFP-MEI-S332-124AAA mutant protein at centromeres. A total of 66% of cells expressing this mutant version showed reduced signal at centromeres (Figures 7D-7E, arrow; Figure 7G). Quantification of fluorescence intensity showed that kinetochores in cells with high levels of mutant MEI-S332 have a level similar to wild-type, whereas kinetochores with lower levels of mutant protein show up to a 15-fold reduction in fluorescence (data not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this analysis of Drosophila incenp mutants reveals for the first time a crucial role for INCENP in regulating centromeric cohesion during the reductional division of meiosis. INCENP influences the localization and/or function of MEI-S332: precocious sister chromatid separation is observed at the centromeres in the mutants, the distribution of MEI-S332 is abnormal when INCENP levels are decreased, INCENP can bind MEI-S332 in vitro, the protein is phosphorylated in vitro by Aurora B, and MEI-S332 localization to centromeres in mitosis is perturbed when its preferred Aurora B phosphorylation site is mutated.

incenp Mutations Affect Sister Chromatid Cohesion and Chromosome Condensation and Cause Nondisjunction in Drosophila Male Meiosis

The QA26 incenp mutation perturbs chromosome condensation and causes precocious separation of the sister chromatids in spermatocytes. Quantitative genetic nondisjunction tests showed that chromosome segregation fails in both meiosis I and II, and that these non-disjunction events are consistent with premature separation of sister chromatids and random segregation in both meiotic divisions. This genetic analysis is likely to underestimate the true rates of nondisjunction because many of the defects caused by loss of passenger function (e.g., defective spindle organization or cytokinesis) would not yield functional gametes, thereby preventing us from scoring all of the nondisjunction events. Although the aberrant condensation in prophase and prometaphase I made direct visualization of the onset of loss of cohesion difficult, completely separated sister chromatids could unambiguously be seen in mutant anaphase I cells, confirming one mechanism that contributes to the genetic nondisjunction phenotype.

In C. elegans meiosis, the chromosome passenger complex is necessary for chiasma resolution (Kaitna et al., 2002; Rogers et al., 2002). If chromosomal passengers were to participate both in regulation of centromeric cohesion as well as processing of chiasmata in C. elegans, essential roles in the latter might obscure roles in the former. In Drosophila male meiosis, there is no synapsis of homologs or recombination. Rather, segregation of homologous chromosomes is regulated via specific pairing sites (McKee, 2004). The analysis of passenger function was therefore simplified in Drosophila males, where chiasmata do not form.

INCENP Is Required for the Stable Localization of MEI-S332 Protein to Centromeres in Mitosis and Meiosis

The MEI-S332-related yeast Shugoshin proteins are critical for the maintenance of the meiotic-specific cohesin subunit Rec8 at centromeres during anaphase I (Katis et al., 2004; Kitajima et al., 2004; Marston et al., 2004; Rabitsch et al., 2004).

Interestingly, no Rec8 homolog has yet been found in Drosophila. The only Drosophila meiotic kleisin, C(2)M, is a component of the synaptonemal complex (Anderson et al., 2005; Manheim and McKim, 2003) and has been shown to have an earlier role in female (Heidmann et al., 2004) and male meiosis (M.C., unpublished data). Thus, what MEI-S332 protects at centromeres in meiosis remains unclear. In mitosis, ablation of MEI-S332 does not lead to premature loss of the mitotic cohesin Rad21 from centromeres (Lee et al., 2005).

In both incenp mutants, impaired INCENP function results in a failure of MEI-S332 localization to centromeres in meiosis. This presumably leads to defects in the protection of cohesion at sister centromeres and contributes to the observed increase in meiotic nondisjunction. The failure to localize MEI-S332 in the incenp mutants is not a general secondary effect of prophase I condensation defects or of premature sister chromatid separation prior to the onset of anaphase I: ord mutants, which display both of those phenotypes, localize MEI-S332 normally (Bickel et al. 1998). Although our data support a role for MEI-S332 in the increased nondisjunction in incenp mutants, mei-S332 mutants predominantly lead to meiosis II nondisjunction, whereas the incenp alleles show defects in both meiotic divisions. Thus, INCENP must be required for additional functions beyond its role in MEI-S332 regulation described here.

Potential Roles for INCENP in Regulating MEI-S332 Function

One mechanism by which INCENP could promote MEI-S332 function is through its role in establishing or maintaining the specialized chromatin structure around centromeres. The chromosomal passenger complex is involved in regulation of chromatin remodeling complexes like ISWI (MacCallum et al., 2002), and it interacts with histone and nonhistone proteins from the pericentric heterochromatin (Ainsztein et al., 1998; Rangasamy et al., 2003). Recent studies show a direct link between Aurora B activity and regulation of HP1 localization in mitosis (Fischle et al., 2005; Hirota et al., 2005), suggesting a possible role in the regulation of heterochromatin structure. Since heterochromatin is important for cohesin binding to centromeres (Bernard et al., 2001; Nonaka et al., 2002), it is possible that modifications of both MEI-S332 and the underlying heterochromatin are important for stabilizing centromeric cohesion during meiosis I.

Alternatively, INCENP could act as a platform for the regulation of MEI-S332 at centromeres. The direct binding between INCENP and MEI-S332 could target MEI-S332 to heterochromatin, or it could help to direct its regulation by protein kinases. MEI-S332 binds better in vitro to a mixture of INCENP and Aurora B than to INCENP alone, suggesting that the interaction is strengthened by phosphorylation of either INCENP or MEI-S332. In addition to its role in binding and activating Aurora B, INCENP that has been phosphorylated by CDK1 can bind to Plk1, the human homolog of POLO kinase. Binding to phosphorylated INCENP is required to target Plk1 to centromeres in mitosis (Goto et al., 2005). Thus, INCENP could potentially coordinate the functions of POLO and Aurora B, both of which have been implicated in the regulation of cohesin (and also in the regulation of MEI-S332 in the case of POLO). These kinases have been shown to cooperate in the release of arm cohesion in chromosomes assembled in Xenopus extracts (Losada et al., 2002). In contrast to Aurora B, however, POLO promotes the dissociation of MEI-S332 from centromeres during mitosis and meiosis (Clarke et al., 2005). In polo mutants, MEI-S332 persists on the centromere, and mutation of two POLO box domains disrupts POLO binding and phosphorylation of MEI-S332 in vitro, as well as MEI-S332 dissociation from the centromeres.

Together, these observations suggest that INCENP may act to integrate the various pathways controlling MEI-S332 function in meiosis I (Figure 7H). Early in meiosis I, INCENP/Aurora B complexes may stabilize centromeric MEI-S332 through direct binding or modification of the underlying chromatin as described above. Similar to what happens in mitosis, CDK1 could phosphorylate INCENP at the POLO binding site, and phosphorylation-dependent binding of POLO to INCENP could target the kinase to the centromere (Goto et al., 2005). This binding might also render the kinase unavailable to phosphorylate MEI-S332. During the metaphase-anaphase I transition, INCENP remains on the centromeres and might therefore prevent MEI-S332 from being phosphorylated by POLO. At the onset of anaphase II, however, as INCENP transitions off the centromere, POLO may be free to phosphorylate MEI-S332, thereby releasing it from centromeres, allowing the release of sister chromatid cohesion.

INCENP is emerging as a key regulator of kinase signaling pathways in mitosis. The present study reveals that this versatile protein may have a similar role in meiosis and may use its interactions with Aurora B and POLO to coordinate the specialized behavior of sister chromatids in meiosis I.

Experimental Procedures

See Supplemental Data.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Data include further discussion of the genetic analysis of the P(EP)2340 allele, a figure showing defects in MEI-S332 local-ization in P(EP)2340 spermatocytes, and a description of the Experimental Procedures employed and are available at http://www.developmentalcell.com/cgi/content/full/11/1/57/DC1/.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard R. Adams and David M. Glover for gifts of antisera and Daniel Roth for technical assistance to M.C. Laura Lee carried out the initial mapping studies on QA26. Some fly strains were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. T.D.R. and T.L.O.-W. were supported by National Science Foundation grant MCB0132237 and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant GM39341. T.D.R. was supported by an Anna Fuller graduate fellowship. D.L.S. was supported by training grant HD07528 for Developmental Biology at the University of Virginia. P.T.S. was supported by a grant from the NIH, GM63045, and by a grant from the Pew Charitable Trust. M.C. and W.C.E. were supported by the Wellcome Trust, of which W.C.E. is a Principal Research Fellow.

References

- Adams RR, Tavares AA, Salzberg A, Bellen HJ, Glover DM. pavarotti encodes a kinesin-like protein required to organize the central spindle and contractile ring for cytokinesis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1483–1494. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RR, Wheatley SP, Gouldsworthy AM, Kandels-Lewis SE, Carmena M, Smythe C, Gerloff DL, Earnshaw WC. INCENP binds the Aurora-related kinase AIRK2 and is required to target it to chromosomes, the central spindle and cleavage furrow. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1075–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00673-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RR, Eckley DM, Vagnarelli P, Wheatley SP, Gerloff DL, Mackay AM, Svingen PA, Kaufmann SH, Earnshaw WC. Human INCENP colocalizes with the Aurora-B/AIRK2 kinase on chromosomes and is overexpressed in tumour cells. Chromosoma. 2001a;110:65–74. doi: 10.1007/s004120100130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RR, Maiato H, Earnshaw WC, Carmena M. Essential roles of Drosophila innercentromere protein (INCENP) and Aurora B in histone H3 phosphorylation, metaphase chromosome alignment, kinetochore disjunction, and chromosome segregation. J Cell Biol. 2001b;153:865–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsztein AM, Kandels-Lewis SE, Mackay AM, Earnshaw WC. INCENP centromere and spindle targeting: identification of essential conserved motifs and involvement of heterochromatin protein HP1. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1763–1774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LK, Royer SM, Page SL, McKim KS, Lai A, Lilly MA, Hawley RS. Juxtaposition of C(2)M and the transverse filament protein C(3)G within the central region of Drosophila synaptonemal complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4482–4487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500172102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ault JG, Lin H-PP, Church K. Meiosis in Drosophila melanogaster. IV. The conjunctive mechanism of the XY bivalent. Chromosoma. 1982;86:309–317. doi: 10.1007/BF00292259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard P, Maure JF, Partridge JF, Genier S, Javerzat JP, Allshire RC. Requirement of heterochromatin for cohesion at centromeres. Science. 2001;294:2539–2542. doi: 10.1126/science.1064027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel SE, Moore DP, Lai C, Orr-Weaver TL. Genetic interactions between mei-S332 and ord in the control of sister-chromatid cohesion. Genetics. 1998;150:1467–1476. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.4.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop JD, Schumacher JM. Phosphorylation of the carboxyl terminus of inner centromere protein (INCENP) by the Aurora B Kinase stimulates Aurora B kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27577–27580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200307200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blower MD, Karpen GH. The role of Drosophila CID in kinetochore formation, cell-cycle progression and heterochromatin interactions. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:730–739. doi: 10.1038/35087045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonomo SBC, Clyne RK, Fuchs J, Loidl J, Ulhmann F, Nasmyth K. Disjunction of homologous chromosomes in meiosis I depends on proteolytic cleavage of the meiotic cohesin Rec8 by Separin. Cell. 2000;103:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmena M, Earnshaw WC. The cellular geography of Aurora kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:842–854. doi: 10.1038/nrm1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A, Carmena M, Sambade C, Earnshaw WC, Wheatley SP. Survivin is required for stable checkpoint activation in taxol-treated HeLa cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2987–2998. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-J, Goulding S, Adams RR, Earnshaw WC, Carmena M. DmINCENP is required for cytokinesis and asymmetric cell division during development of the nervous system. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1144–1153. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Chu T, Harms E, Gergen J, Strickland S. Mapping of Drosophila mutations using site-specific male recombination. Genetics. 1998;149:157–163. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AS, Tang TT, Ooi DL, Orr-Weaver TL. POLO kinase regulates the Drosophila centromere cohesion protein MEI-S332. Dev Cell. 2005;8:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke CA, Heck MM, Earnshaw WC. The inner centromere protein (INCENP) antigens: movement from inner centromere to midbody during mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2053–2067. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W, Tseng BS, Dormann HL, Ueberheide BM, Garcia BA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Funabiki H, Allis CD. Regulation of HP1-chromatin binding by histone H3 methylation and phosphorylation. Nature. 2005;438:1116–1122. doi: 10.1038/nature04219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann R, Carvalho A, Henzing AJ, Ruchaud S, Hudson DF, Honda R, Nigg EA, Gerloff DL, Earnshaw WC. Borealin:anovel chromosomal passenger required for stability of the bipolar mitotic spindle. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:179–191. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giet R, Glover DM. Drosophila Aurora B kinase is re-quired for histone H3 phosphorylation and condensin recruitment during chromosome condensation and to organize the central spindle during cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:669–682. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Abian JF, Sumara I, Hirota T, Hauf S, Gerlich D, de la Torre C, Ellenberg J, Peters JM. Regulation of sister chromatid cohesion between chromosome arms. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1187–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto H, Kiyono T, Tomono Y, Kawajiri A, Urano T, Furukawa K, Nigg EA, Inagaki M. Complex formation of Plk1 and INCENP required for metaphase-anaphase transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;8:180–187. doi: 10.1038/ncb1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidmann D, Horn S, Heidmann S, Schleiffer A, Nasmyth K, Lehner CF. The Drosophila meiotic kleisin C(2)M functions before the meiotic divisions. Chromosoma. 2004;113:177–187. doi: 10.1007/s00412-004-0305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota T, Lipp JJ, Toh BH, Peters JM. Histone H3 serine 10 phosphorylation by Aurora B causes HP1 dissociation from heterochromatin. Nature. 2005;438:1176–1180. doi: 10.1038/nature04254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda R, Korner R, Nigg EA. Exploring the functional interactions between Aurora B, INCENP, and survivin in mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3325–3341. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaitna S, Pasierbek P, Jantsch M, Loidl J, Glotzer M. The Aurora B kinase AIR-2 regulates kinetochores during mitosis and is required for separation of homologous chromosomes during meiosis. Curr Biol. 2002;12:798–812. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00820-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Cheeseman IM, Kallstrom G, Velmurugan S, Barnes G, Chan CS. Functional cooperation of Dam1, Ipl1, and the inner centromere protein (INCENP)-related protein Sli15 during chromosome segregation. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:763–774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katis VL, Galova M, Rabitsch KP, Gregan J, Nasmyth K. Maintenance of cohesin at centromeres after meiosis I in budding yeast requires a kinetochore-associated protein related to MEI-S332. Curr Biol. 2004;14:560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrebrock AW, Moore DP, Wu JS, Orr-Weaver TL. MEI-S332, a Drosophila protein required for sister-chromatid cohesion, can localize to meiotic centromere regions. Cell. 1995;83:247–256. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima TS, Kawashima SA, Watanabe Y. The conserved kinetochore protein shugoshin protects centromeric cohesion during meiosis. Nature. 2004;427:510–517. doi: 10.1038/nature02312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc HN, Tang TT, Wu JS, Orr-Weaver TL. The mitotic centromeric protein MEI-S332 and its role in sister-chromatid cohesion. Chromosoma. 1999;108:401–411. doi: 10.1007/s004120050392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Dej KJ, Lopez JM, Orr-Weaver TL. Control of centromere localization of the MEI-S332 cohesion protection protein. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1277–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Hayashi-Hagihara A, Orr-Weaver T. Roles and regulation of the Drosophila centromere cohesion protein MEI-S332 family. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:543–552. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez JM, Karpen GH, Orr-Weaver TL. Sister-chromatid cohesion via MEI-S332 and kinetochore assembly are separable functions of the Drosophila centromere. Curr Biol. 2000;10:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00650-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losada A, Hirano M, Hirano T. Cohesin release is required for sister chromatid resolution, but not for condensin-mediated compaction, at the onset of mitosis. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3004–3016. doi: 10.1101/gad.249202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum DE, Losada A, Kobayashi R, Hirano T. ISWI remodeling complexes in Xenopus egg extracts: identification as major chromosomal components that are regulated by INCENP-aurora B. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:25–39. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-09-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manheim EA, McKim KS. The synaptonemal complex component C(2)M regulates meiotic crossing over in Drosophila . Curr Biol. 2003;13:276–285. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston AL, Tham WH, Shah H, Amon A. A genome-wide screen identifies genes required for centromeric cohesion. Science. 2004;303:1367–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.1094220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness BE, Hirota T, Kudo NR, Peters JM, Nasmyth K. Shugoshin prevents dissociation of cohesin from centro-meres during mitosis in vertebrate cells. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e86. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee BD. Homologous pairing and chromosome dynamics in meiosis and mitosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677:165–180. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki WY, Orr-Weaver TL. Sister-chromatid misbehavior in Drosophila ord mutants. Genetics. 1992;132:1047–1061. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.4.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TH. Complete linkage in the second chromosome of the male of Drosophila . Science. 1912;36:719–720. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka N, Kitajima T, Yokobayashi S, Xiao G, Yamamoto M, Grewal SI, Watanabe Y. Recruitment of cohesin to heterochromatic regions by Swi6/HP1 in fission yeast. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:89–93. doi: 10.1038/ncb739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra MT, Viera A, Gomez R, Page J, Carmena M, Earnshaw WC, Rufas JS, Suja JA. Dynamic relocalization of the chromosomal passenger complex proteins inner centromere protein (INCENP) and Aurora-B kinase during male mouse meiosis. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:961–974. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira G, Schiebel E. Separase regulates INCENP-Aurora B anaphase spindle function through Cdc14. Science. 2003;302:2120–2124. doi: 10.1126/science.1091936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronczki M, Siomos MF, Nasmyth K. Un menage a quatre: the molecular biology of chromosome segregation in meiosis. Cell. 2003;112:423–440. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabitsch KP, Gregan J, Schleiffer A, Javerzat JP, Eisenhaber F, Nasmyth K. Two fission yeast homologs of Drosophila Mei-S332 are required for chromosome segregation during meiosis I and II. Curr Biol. 2004;14:287–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangasamy D, Berven L, Ridgway P, Tremethick DJ. Pericentric heterochromatin becomes enriched with H2A.Z during early mammalian development. EMBO J. 2003;22:1599–1607. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E, Bishop JD, Waddle JA, Schumacher JM, Lin R. The aurora kinase AIR-2 functions in the release of chromosome cohesion in Caenorhabditis elegans meiosis. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:219–229. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorth P. A modular misexpression screen in Drosophila detecting tissue-specific phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12418–12422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath SC, Ohi R, Leismann O, Salic A, Pozniakovski A, Funabiki H. The chromosomal passenger complex is required for chromatin-induced microtubule stabilization and spindle assembly. Cell. 2004;118:187–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JM, Golden A, Donovan PJ. AIR-2: an Aurora/Ipl1-related protein kinase associated with chromosomes and midbody microtubules is required for polar body extrusion and cytokinesis in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1635–1646. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupbach T, Wieschaus E. Female sterile mutations on the second chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. I. Maternal effect mutations. Genetics. 1989;121:101–117. doi: 10.1093/genetics/121.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoufias DA, Mollinari C, Lacroix FB, Margolis RL. Human survivin is a kinetochore-associated passenger protein. JCell Biol. 2000;151:1575–1582. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TT-L, Bickel SE, Young LM, Orr-Weaver TL. Maintenance of sister-chromatid cohesion at the centromere by the Drosophila MEI-S332 protein. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3843–3856. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada Y, Tatsuka M, Suzuki F, Yasuda Y, Fujita S, Otsu M. AIM-1: a mammalian midbody-associated protein required for cytokinesis. EMBO J. 1998;17:667–676. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng AS, Hariharan IK. An overexpression screen in Drosophila for genes that restrict growth or cell-cycle progression in the developing eye. Genetics. 2002;162:229–243. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F, Wernic D, Poupart MA, Koonin EV, Nasmyth K. Cleavage of cohesin by the CD clan protease separin triggers anaphase in yeast. Cell. 2000;103:375–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uren AG, Wong L, Pakusch M, Fowler KJ, Burrows FJ, Vaux DL, Choo KH. Survivin and the inner centromere protein INCENP show similar cell-cycle localization and gene knockout phenotype. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1319–1328. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00769-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagnarelli P, Earnshaw WC. Chromosomal passengers: the four-dimensional regulation of mitotic events. Chromosoma. 2004;113:211–222. doi: 10.1007/s00412-004-0307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley SP, Kandels-Lewis SE, Adams RR, Ainsztein AM, Earnshaw WC. INCENP binds directly to tubulin and requires dynamic microtubules to target to the cleavage furrow. Exp Cell Res. 2001;262:122–127. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.