Abstract

Background

To quantify the association between effects of interventions on carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) progression and their effects on cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.

Methods

We systematically collated data from randomized controlled trials. cIMT was assessed as the mean value at the common-carotid-artery; if unavailable, the maximum value at the common-carotid-artery or other cIMT measures were utilized. The primary outcome was a combined CVD endpoint defined as myocardial infarction, stroke, revascularization procedures, or fatal CVD. We estimated intervention effects on cIMT progression and incident CVD for each trial, before relating the two using a Bayesian meta-regression approach.

Results

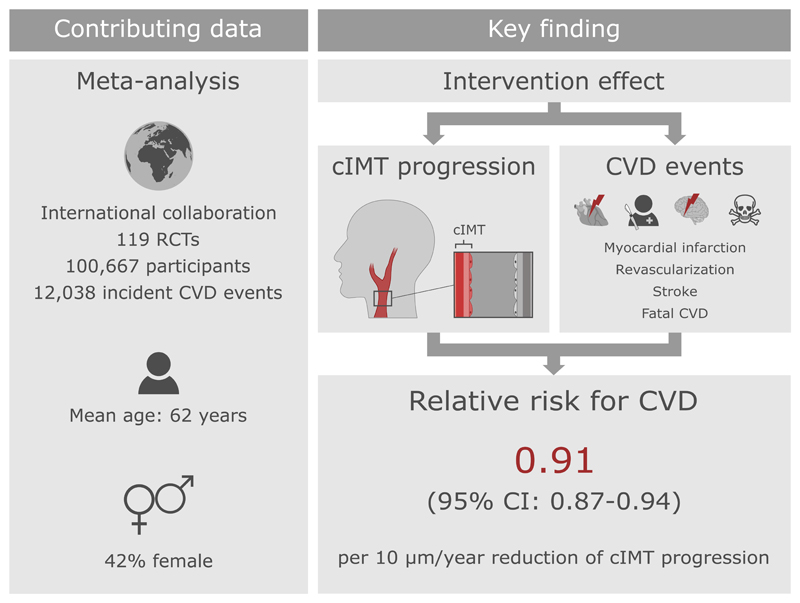

We analyzed data of 119 randomized controlled trials involving 100,667 patients (mean age 62 years, 42% female). Over an average follow-up of 3.7 years, 12,038 patients developed the combined CVD endpoint. Across all interventions, each 10 μm/year reduction of cIMT progression resulted in a relative risk for CVD of 0.91 (95% credible interval 0.87-0.94), with an additional relative risk for CVD of 0.92 (0.87-0.97) being achieved independent of cIMT progression. Taken together, we estimated that interventions reducing cIMT progression by 10, 20, 30, or 40 μm/year would yield relative risks of 0.84 (0.75-0.93), 0.76 (0.67-0.85), 0.69 (0.59-0.79), or 0.63 (0.52-0.74). Results were similar when grouping trials by type of intervention, time of conduct, time to ultrasound follow-up, availability of individual-participant data, primary vs. secondary prevention trials, type of cIMT measurement, and proportion of female patients.

Conclusions

The extent of intervention effects on cIMT progression predicted the degree of CVD risk reduction. This provides a missing link supporting the usefulness of cIMT progression as a surrogate marker for CVD risk in clinical trials.

Keywords: Intima-media thickness, Cardiovascular disease, Surrogate marker, Clinical trials, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT), the thickness of the intimal and medial layer of the carotid artery wall, can be measured non-invasively using ultrasound imaging and is considered a marker for the early stage of atherosclerosis.1 Mean values of cIMT in adults range around 650-900 µm and increase – on average – at a rate of 0-40 µm/year.2,3 A large number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that therapeutic interventions may slow progression of cIMT. However, it is uncertain whether effects on cIMT progression translate into reduced risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, that is whether cIMT progression is a valid surrogate marker for CVD.

In 2005, Espeland et al. first proposed cIMT progression as a surrogate marker for CVD risk based on findings in seven statin trials,4 but their arguments were based on limited data and most researchers were reluctant to rely on cIMT results alone.5 In 2009, ARBITER-6 HALTS was the first RCT to be terminated early based on findings for cIMT progression, showing superiority of extended-release niacin over ezetimibe.6 This decision was controversial due to the uncertain validity of the rate of progression of cIMT as a surrogate marker for clinical endpoints.7,8 Two subsequent literature-based meta-regression analyses on this topic have yielded conflicting results: Goldberger et al. 9 observed an association of effects on cIMT progression and risk of myocardial infarction, whereas Costanzo et al. 10 found no statistically significant association of changes in mean or maximal cIMT with risk of myocardial infarction or stroke. Both of these meta-analyses have been criticized because of methodological flaws.11

To address this uncertainty, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of 119 RCTs involving a total of 100,667 patients. Our aims were to: (i) quantify the reduction in CVD risk associated with reducing cIMT progression by therapeutic intervention; (ii) explore cIMT progression as a surrogate marker for different types of CVD endpoints as well as all-cause mortality; and (iii) investigate differences according to the intervention type, method of cIMT assessment, and other trial characteristics.

Methods

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are not made publicly available due to legal restrictions arising from the data distribution policy of the PROG-IMT/Proof-ATHERO collaborations and from the bilateral agreements between the consortium’s coordinating center and participating studies, but they may be requested directly from individual study investigators. Studies that shared individual-participant data have obtained informed consent of the study participants and ethical approval by their respective institutional review boards.

The report of the results of our study adhere to the PRISMA-IPD guidelines (Table I in the Supplement); the objectives and statistical methods in this paper have been described previously12. We identified relevant RCTs published before 3 February 2020 through systematic searches of ten medical knowledge databases, six clinical trial registries, and reference lists of relevant publications and reviews (Table II in the Supplement). Trials were eligible for inclusion if they: (1) had assigned patients randomly to two or more arms; (2) had applied well-defined inclusion criteria; (3) had measured cIMT at trial baseline and at one or more follow-up visits; and (4) had recorded incident CVD outcomes. We requested anonymized patient-level data from these trials, performed comprehensive plausibility checks, and were able to resolve any data-related queries through direct correspondence with trial investigators. For trials for which patient-level data was unavailable, four authors (PW, LT, EA, MWL) independently extracted the relevant data from the published literature and resolved any discrepancies by consensus.

As a measure of cIMT, we gave preference to assessments of mean values at the common-carotid-artery. If unavailable, we used maximum values at the common-carotid-artery or cIMT at other sections of the carotid artery instead. In trials quantifying cIMT values at different sites (i.e. left or right side, near or far vessel wall, or at different insonation angles), the arithmetic mean of these measurements was used. The primary outcome was a combined CVD endpoint defined as myocardial infarction, stroke, revascularization procedures (e.g. coronary or carotid revascularization), or fatal CVD. For trials without data on cause-specific death, all-cause mortality was included in the primary outcome instead. Table III in the Supplement provides details on the assessment of cIMT progression and primary outcome definition in each trial.

Statistical analysis

We conducted analyses according to a pre-specified analysis plan. For factorial trials, we analyzed the intervention contrast anticipated to have the greatest effect on CVD risk. For trials with more than two trial arms, we compared the arm that was – based on prior trials – anticipated to have the greatest effect to the arm anticipated to have the least effect (or no effect in case of placebo). For all trials, the latter group was used as reference.

The principal analysis consisted of three steps. First, we quantified intervention effects on cIMT progression. For each trial for which patient-level data was available, we used a linear mixed model to estimate the difference in yearly cIMT progression between trial arms. The model included fixed effects for assigned treatment, time in study, and the interaction of the two, plus an intercept and time variable allowed to vary randomly at the patient level. For each trial for which literature-based data was available (i.e. tabular data extracted from the trials’ publications), we annualized differences in cIMT progression and calculated standard errors from P values, if necessary.

Second, we quantified intervention effects on the CVD outcome. For each trial with patient-level data, we fitted a Cox proportional-hazards model to estimate the log hazard ratio and its standard error comparing the trial arms. If estimates were inestimable due to a low event number, we applied an augmentation procedure to allow incorporation of the trial in the meta-analysis.13 For each trial with literature-based data, we calculated the log risk ratio and its standard error based on the number of events and patients in each trial arm. For trials in which one arm had zero events, the number of events and non-events were each augmented by +0.5 in both trial arms. Hazard ratios and risk ratios are collectively described as measures of relative risk (RR).

Third, to test whether effects on CVD risk depended on effects on cIMT progression, we used a Bayesian meta-regression approach that models both effects simultaneously, while taking into account the estimated precisions in these two effects.14 The principal analysis involved (i) a model with an intercept of zero (i.e. forcing the regression line through the origin and thereby assuming that all the effects on CVD risk operate through cIMT progression) and (ii) a model with a non-zero intercept (i.e. allowing for an effect on CVD risk independent of cIMT progression). The meta-regression also took into account the within-study correlation of the two effects, which was estimated using bootstrapping in the trials with patient-level data and >30 events.15 For other trials, an overall correlation coefficient pooled using random-effects meta-analysis was used instead. Further details on methods for assessing surrogacy are provided in the Methods in the Supplement.

Subsidiary analyses evaluated surrogacy for individual disease endpoints and in trials grouped by intervention type, time of conduct, time to ultrasound follow-up, availability of individual-participant data, primary vs. secondary prevention trials, type of cIMT measure, and proportion of female patients. A Bayesian approach was taken for estimation of the meta-regression model parameters and for prediction (for details, see the Methods in the Supplement). Analyses were performed using Stata 15, R 2.5.1 and JAGS 4.3.0. PW had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Results

Among 10,260 articles screened, we identified 119 trials involving 100,667 patients that met the pre-specified inclusion criteria (Figure I in the Supplement). 103 trials (87%) had two arms, seven had three arms, one had four arms, seven had a 2x2 factorial design, and one had a 3x2 factorial design (Table 1). The trials employed antidiabetic (18 trials), antihypertensive (19 trials), dietary/vitamin (20 trials), lipid-lowering (33 trials), and/or other interventions (37 trials). Mean age at baseline was 62 years (standard deviation 8); 42% were female. Over an average follow-up duration of 3.7 years, 12,038 patients developed the primary CVD endpoint. The median proportion of patients with repeat cIMT measurements across trials was 90%. Seven large cardiovascular outcome trials had measured cIMT only in a subset of patients (Table 1). Mean cIMT measured at the common-carotid-artery was available in 91 trials, maximum cIMT at the common-carotid-artery in 49 trials, and other cIMT measures in 11 trials. Across contributing trials, the mean rate of cIMT progression was +9.1 µm/year (95% confidence interval: 7.1 to 11.1) in control arms and +1.0 µm/year (-0.6 to 2.7) in interventions arms. Across all contributing trials, the RR for CVD with intervention was 0.88 (0.83-0.92).

Table 1. Key features of the trials included in this report.

| Type of intervention* | CVD risk | cIMT progression | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Trial | Years of baseline | Country | Access to IPD | No. of trial arms | Antidiabetic | Antihypertensive | Dietary / vitamins | Lipid-lowering | Other | No. of patients | Type of population | Mean age (SD), years | % female | Median follow-up, years | No. of events | Maximum follow-up, years | % with cIMT data | Mean CCA-IMT | Max CCA-IMT | Other cIMT |

| ACAPS16,17 | 1989-1990 | USA | ● | 2x2 | - | - | - | ● | ● | 919 | Elevated CVD risk | 62 (8) | 48 | 5.0 | 18 | 6.0 | 100 | - | ● | - |

| ACT NOW18,19 | 2004-2006 | USA | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 602 | Dysglycemia | 52 (10) | 58 | 2.2† | 13 | 4.0 | 63 | ● | - | - |

| ALLO-IMT20 | 2009-2010 | UK | ● | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 80 | Pre-existing CVD | 68 (10) | 43 | 1.0 | 11 | 1.2 | 100 | ● | ● | - |

| AMAR21 | 2004-2005 | Russia | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 257 | Elevated CVD risk | 61 (9) | 0 | 2.0‡ | 21 | 2.0 | 76 | ● | - | - |

| ARBITER22 | 1999-2001 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 161 | Elevated CVD risk | 60 (12) | 29 | 1.0‡ | 6 | 1.0 | 86 | ● | ● | - |

| ARBITER 223 | 2001-2003 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 167 | Pre-existing CVD | 67 (10) | 9 | 1.0‡ | 10 | 1.0 | 89 | ● | - | - |

| ARBITER 6-HALTS6,24,25 | 2006-2009 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 363 | Pre-existing CVD | 65 (10) | 20 | 1.2‡ | 11 | 1.2 | 57 | ● | ● | - |

| ARTSTIFF26 | 2008-2011 | International | - | 3 | - | ● | - | - | - | 133 | Hypertension | 53 (10) | 37 | 1.0‡ | 0 | 1.0 | 87 | ● | - | - |

| ASAP-FINLAND27–29 | 1994-1995 | Finland | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 520 | Hyperlipidemia | 60 (6) | 51 | 6.0‡ | 22 | 6.0 | 85 | ● | - | - |

| ASAP-NL30,31 | 1997-1998 | Netherlands | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 330 | Hyperlipidemia | 49 (11) | 61 | 2.0‡ | 5 | 2.0 | 85 | ● | - | - |

| ASFAST32 | 1998-2000 | International | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 315 | Kidney disease | 56 (13) | 32 | 3.3† | 73 | 3.6 | 77 | - | ● | - |

| ATIC33,34 | 2001-2002 | Netherlands | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 93 | Kidney disease | 53 (12) | 43 | 2.0‡ | 4 | 1.5 | 80 | ● | - | - |

| Ahn et al.35 | 2005-2006 | Korea | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 130 | Pre-existing CVD | 64 (11) | 38 | 2.0‡ | 18 | 2.0 | 73 | - | - | ● |

| Andrews et al.36,37 | 2011-2015 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 80 | Kidney disease | 57 (12) | 20 | 0.2‡ | 1 | 0.2 | 79 | ● | - | - |

| BCAPS38 | 1994-1996 | Sweden | - | 2x2 | - | ● | - | ● | - | 793 | Elevated CVD risk | 62 (5) | 54 | 3.0† | 18 | 3.0 | 99 | ● | - | - |

| BKREGISTRY-II39 | 2000-2003 | Korea | ● | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 205 | Pre-existing CVD | 60 (10) | 32 | 0.5 | 3 | 1.1 | 59 | ● | - | - |

| BVAIT40 | 2000-2006 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 506 | General population | 61 (10) | 39 | 3.1† | 20 | 2.5 | 97 | ● | - | - |

| CAIUS41 | 1991-1992 | Italy | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 305 | Hyperlipidemia | 55 (6) | 47 | 3.0‡ | 5 | 3.0 | 100 | - | ● | - |

| CAMERA42 | 2009-2011 | UK | ● | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 173 | Pre-existing CVD | 63 (8) | 23 | 1.5 | 12 | 2.3 | 100 | ● | - | - |

| CAPPA43 | 2009 | Korea | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 420 | Dysglycemia | 60 (9) | 50 | 3.0‡ | 6 | 3.0 | 99 | ● | ● | - |

| CAPTIVATE44 | 2004-2005 | International | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 892 | Hyperlipidemia | 55 (9) | 39 | 2.0‡ | 32 | 1.0 | 99 | - | - | ● |

| CERDIA45 | 1999-2001 | Netherlands | ● | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 250 | Dysglycemia | 58 (11) | 53 | 2.1 | 14 | 2.5 | 99 | ● | ● | - |

| CHICAGO46 | 2003-2005 | USA | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 462 | Dysglycemia | 60 (8) | 37 | 1.4‡ | 13 | 1.4 | 78 | ● | ● | - |

| CIMT phase 147,48 | 2008-2009 | Denmark | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 412 | Dysglycemia | 61 (9) | 32 | 1.5‡ | 20 | 1.5 | 100 | ● | ● | - |

| CLAS49–51 | 1980-1984 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 162 | Pre-existing CVD | 54 (5) | 0 | 7.0† | 82 | 4.0 | 48 | ● | - | - |

| CONTRAST52,53 | 2004-2009 | Netherlands | ● | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 714 | Kidney disease | 64 (14) | 38 | 2.4 | 173 | 3.1 | 20 | ● | ● | - |

| Cao et al.54 | 2008-2011 | China | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 287 | Elevated CVD risk | 71 (13) | 53 | 2.0‡ | 36 | 2.0 | 100 | - | - | ● |

| DAPC55,56 | 2004-2006 | International | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 329 | Dysglycemia | 64 (7) | 48 | 2.0‡ | 3 | 2.0 | 90 | ● | ● | - |

| DAPHNE57 | NR | Netherlands | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 80 | Pre-existing CVD | 59 (7) | 0 | 3.0‡ | 16 | 3.0 | 100 | - | - | ● |

| DOIT58 | 1997-1999 | Norway | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 561 | Elevated CVD risk | 70 (5) | 0 | 3.0‡ | 63 | 3.0 | 83 | ● | - | - |

| EGE STUDY59,60 | 2005-2006 | Turkey | ● | 2x2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 644 | Kidney disease | 59 (14) | 46 | 3.0 | 60 | 3.0 | 100 | ● | - | - |

| ELITE (early MP)61,62 | 2005-2008 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 271 | General population | 55 (4) | 100 | 5.0 | 1 | 5.0 | 92 | ● | - | - |

| ELITE (late MP)61,62 | 2005-2008 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 372 | General population | 65 (6) | 100 | 5.0 | 5 | 5.0 | 94 | ● | - | - |

| ELSA63 | NR | International | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 2334 | Hypertension | 56 (7) | 45 | 4.0‡ | 60 | 4.0 | 87 | - | - | ● |

| ELVA64 | NR | Sweden | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 129 | Hyperlipidemia | 60 (10) | 49 | 3.0‡ | 4 | 3.0 | 71 | ● | - | - |

| ENCORE65,66 | 2003-2008 | USA | ● | 3 | - | - | ● | - | - | 144 | Elevated CVD risk | 52 (10) | 67 | 0.4 | 1 | 1.1 | 98 | ● | - | - |

| ENHANCE67 | 2002-2004 | International | ● | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 720 | Hyperlipidemia | 47 (9) | 49 | 2.0 | 52 | 2.3 | 100 | ● | ● | - |

| EPAT68 | 1994-1998 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 222 | Hyperlipidemia | 61 (7) | 100 | 2.0‡ | 7 | 2.0 | 90 | ● | - | - |

| FIELD69,70 | 1998-2000 | International | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 9795 | Dysglycemia | 62 (7) | 37 | 6.0‡ | 1295 | 5.0 | 2 | - | ● | - |

| FIRST71,72 | 2008-2010 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 682 | Pre-existing CVD | 61 (9) | 32 | 2.1‡ | 30 | 2.0 | 84 | - | ● | - |

| FRANCIS73,74 | 2011-2012 | Netherlands | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 320 | Elevated CVD risk | 53 (11) | 70 | 5.0‡ | 9 | 5.0 | 100 | ● | - | - |

| GRACE75 | 2003-2005 | International | ● | 2x2 | ● | - | ● | - | - | 1189 | Dysglycemia | 63 (8) | 36 | 5.8 | 374 | 5.1 | 100 | ● | ● | - |

| Gresele et al.76 | 2003-2005 | International | ● | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 442 | Pre-existing CVD | 67 (9) | 21 | 0.6 | 8 | 0.6 | 57 | ● | ● | - |

| HART77 | 1999-2000 | International | ● | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 925 | Pre-existing CVD | 69 (7) | 24 | 5.0 | 152 | 5.6 | 100 | ● | ● | - |

| HERS78,79 | 1993-1994 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 2763 | General population | 67 (7) | 100 | 4.1† | 552 | 4.7 | 16 | - | ● | - |

| HYRIM80 | 1997-1999 | Norway | ● | 2x2 | - | - | - | ● | ● | 568 | Hypertension | 57 (9) | 0 | 4.1 | 47 | 4.6 | 99 | - | ● | - |

| INSIGHT81–83 | 1994-1996 | France | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 6321 | Elevated CVD risk | 65 (7) | 54 | 3.5† | 347 | 4.0 | 5 | ● | - | - |

| J-STARS84–88 | 2004-2009 | Japan | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 1589 | Pre-existing CVD | 66 (8) | 31 | 4.9† | 290 | 5.0 | 50 | ● | - | - |

| JART89 | 2008-2010 | Japan | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 348 | Hyperlipidemia | 64 (9) | 51 | 2.0‡ | 9 | 2.0 | 40 | ● | ● | - |

| KAPS90 | 1984-1989 | Finland | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 447 | Hyperlipidemia | 57 (4) | 0 | 3.0‡ | 28 | 3.0 | 95 | - | ● | - |

| KEEPS91 | 2005-2008 | USA | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | ● | 727 | General population | 53 (3) | 100 | 4.0‡ | 1 | 4.0 | 100 | ● | - | - |

| KIMVASC92 | 2011-2012 | UK | ● | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 80 | Pre-existing CVD | 77 (5) | 45 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 99 | ● | - | - |

| Katakami et al.93 | 1998 | Japan | - | 3 | ● | - | - | - | - | 159 | Dysglycemia | 61 (9) | 51 | 3.3† | 0 | 3.3 | 74 | - | - | ● |

| Koyasu et al.94 | 2006-2008 | Japan | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 90 | Pre-existing CVD | 66 (8) | 9 | 1.0‡ | 0 | 1.0 | 90 | - | ● | - |

| LAARS95 | NR | International | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 280 | Hypertension | 59 (9) | 50 | 2.0‡ | 0 | 2.0 | 72 | ● | - | - |

| LIFE-ICARUS96 | 1996-1997 | International | ● | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 83 | Hypertension | 67 (6) | 27 | 4.9 | 8 | 3.1 | 98 | ● | - | - |

| LIPID97–100 | 1990-1992 | International | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 9014 | Pre-existing CVD | 61 (8) | 17 | 6.1† | 3229 | 4.0 | 4 | ● | - | - |

| Luijendijk et al.101,102 | 2007-2009 | Netherlands | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 155 | Pre-existing CVD | 36 (12) | 38 | 3.3† | 0 | 4.4 | 100 | ● | - | - |

| MARS103,104 | 1985-1989 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 270 | Hyperlipidemia | 58 (7) | 9 | 2.2† | 54 | 4.0 | 27 | ● | - | - |

| MAVET105 | 1994-1995 | Australia | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 409 | Elevated CVD risk | 64 (6) | 55 | 4.0‡ | 6 | 4.0 | 81 | - | ● | - |

| MECANO106,107 | 2005-2006 | Netherlands | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 185 | Kidney disease | 51 (13) | 36 | 1.5‡ | 6 | 2.0 | 88 | ● | - | - |

| MEDICLAS108,109 | 2003-2005 | Netherlands | ● | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 48 | Elevated CVD risk | 42 (10) | 0 | 3.0 | 1 | 3.2 | 77 | ● | - | - |

| METEOR110 | 2002-2004 | International | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 984 | Elevated CVD risk | 57 (6) | 40 | 2.0‡ | 3 | 2.0 | 89 | ● | ● | - |

| MG600111 | 2010-2011 | Brazil | ● | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 35 | Hypertension | 55 (7) | 100 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 100 | ● | ● | - |

| MIDAS112 | NR | USA | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 883 | Hypertension | 59 (9) | 22 | 3.0‡ | 47 | 3.0 | 100 | - | ● | - |

| MITEC113,114 | 2000-2002 | France | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 209 | Elevated CVD risk | 60 (8) | 36 | 3.0‡ | 0 | 3.0 | 41 | ● | - | - |

| Makimura et al.115 | 2008-2010 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 60 | Elevated CVD risk | 41 (2) | 35 | 1.0‡ | 0 | 1.0 | 97 | ● | - | - |

| Masia et al.116 | 2006-2007 | Spain | ● | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 68 | Elevated CVD risk | 52 (11) | 10 | 6.0 | 4 | 6.9 | 99 | ● | ● | - |

| Mitsuhashi et al.117 | NR | Japan | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 62 | Dysglycemia | 63 (7) | 35 | 2.6† | 1 | 2.6 | 100 | - | - | ● |

| Mortazavi et al.118 | NR | Iran | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 54 | Kidney disease | 57 (12) | 50 | 0.5‡ | 1 | 0.5 | 96 | ● | - | - |

| NTPP119 | 2005-2010 | Japan | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 123 | Elevated CVD risk | 59 (9) | 54 | 3.0‡ | 0 | 3.0 | 79 | ● | ● | - |

| Nakamura et al. II120 | 2001 | Japan | ● | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 50 | Kidney disease | 53 (7) | 40 | 6.9 | 8 | 4.1 | 100 | ● | ● | - |

| Ntaios et al.121 | 2005 | Greece | ● | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 103 | Elevated CVD risk | 73 (5) | 45 | 1.5 | 18 | 1.5 | 100 | ● | - | - |

| OPAL122,123 | 1997-1999 | International | ● | 3 | - | - | - | - | ● | 866 | General population | 59 (7) | 100 | 3.1 | 9 | 3.7 | 100 | ● | ● | - |

| PART-2124 | NR | New Zealand | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 617 | Pre-existing CVD | 61 (8) | 18 | 4.7† | 150 | 4.0 | 87 | ● | - | - |

| PEACE125 | 2007-2008 | Japan | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 303 | Hyperlipidemia | 66 (9) | 43 | 1.0‡ | 2 | 1.0 | 74 | ● | ● | - |

| PERFORM126,127 | 2006-2008 | International | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 19120 | Pre-existing CVD | 67 (8) | 37 | 2.4† | 2910 | 3.0 | 5 | ● | - | - |

| PERIOCARDIO128 | 2010-2012 | Australia | ● | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 273 | Elevated CVD risk | 41 (10) | 42 | 1.0 | 3 | 1.4 | 99 | ● | ● | - |

| PHOREA129 | 1995-1996 | Germany | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | ● | 321 | General population | 59 (4) | 100 | 0.9‡ | 1 | 0.9 | 54 | - | ● | - |

| PHYLLIS130,131 | 1995-1997 | Italy | - | 4 | - | ● | - | ● | - | 508 | Elevated CVD risk | 58 (7) | 60 | 2.6† | 6 | 2.6 | 82 | - | ● | - |

| PLAC II132–134 | 1987-1990 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 151 | Elevated CVD risk | 63 (NR) | 15 | 3.0‡ | 14 | 3.0 | 100 | - | ● | - |

| PPAR135 | 2002-2003 | International | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 200 | Elevated CVD risk | 59 (10) | 20 | 1.0‡ | 17 | 1.0 | 100 | - | - | ● |

| PREDIMED136,137 | 2008-2009 | Spain | - | 3 | - | - | ● | - | - | 7447 | Elevated CVD risk | 67 (6) | 57 | 4.8 | 288 | 2.4 | 2 | ● | ● | - |

| PREVEND IT138–141 | 1998-1999 | Netherlands | ● | 2x2 | - | ● | - | ● | - | 864 | Kidney disease | 51 (12) | 35 | 3.9 | 102 | 4.7 | 94 | ● | - | - |

| PREVENT142,143 | 1992-1997 | International | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 825 | Elevated CVD risk | 57 (10) | 20 | 3.0‡ | 196 | 3.0 | 46 | - | ● | ● |

| PROBE144,145 | 2002-2003 | Japan | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 587 | Dysglycemia | 58 (NR) | 37 | 4.0‡ | 14 | 3.3 | 30 | ● | ● | - |

| RADIANCE I146,147 | 2003-2004 | International | ● | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 904 | Hyperlipidemia | 46 (13) | 51 | 2.0 | 44 | 2.3 | 98 | ● | ● | - |

| RADIANCE II147,148 | 2004-2006 | International | ● | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 752 | Hyperlipidemia | 57 (8) | 36 | 2.0 | 37 | 2.4 | 98 | ● | ● | - |

| RAS149 | 2002-2003 | Sweden | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 557 | Elevated CVD risk | 67 (6) | 54 | 1.0‡ | 5 | 1.0 | 80 | ● | - | - |

| REGRESS150,151 | 1989-1991 | Netherlands | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 885 | Elevated CVD risk | 56 (8) | 0 | 2.0‡ | 148 | 2.0 | 29 | ● | - | - |

| REMOVAL152,153 | 2011-2014 | International | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 428 | Dysglycemia | 56 (9) | 41 | 3.0‡ | 17 | 3.0 | 99 | ● | ● | - |

| RIS154 | 1987-1989 | Sweden | ● | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 164 | Elevated CVD risk | 66 (5) | 0 | 5.9 | 47 | 7.3 | 99 | ● | ● | - |

| SANDS155–157 | 2003-2004 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 499 | Elevated CVD risk | 56 (9) | 66 | 3.0‡ | 18 | 3.0 | 100 | ● | - | - |

| SCIMO158,159 | 1992-1994 | Germany | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 223 | Elevated CVD risk | 58 (9) | 20 | 2.0‡ | 55 | 2.0 | 77 | - | ● | - |

| SECURE160 | 1994-1995 | Canada | ● | 3x2 | - | ● | ● | - | - | 731 | Elevated CVD risk | 66 (7) | 24 | 4.4 | 103 | 5.3 | 100 | - | ● | - |

| SEKONA161 | 2004-2005 | Germany | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 600 | Elevated CVD risk | 49 (6) | 11 | 3.0‡ | 110 | 3.0 | 66 | ● | - | - |

| SENDCAP162 | 1990-1993 | UK | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 164 | Dysglycemia | 51 (8) | 29 | 3.0‡ | 4 | 3.0 | 77 | - | ● | - |

| SPEAD-A163,164 | 2011-2013 | Japan | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 341 | Dysglycemia | 65 (9) | 42 | 2.0‡ | 4 | 2.0 | 94 | ● | ● | - |

| SPIKE165–167 | 2012 | Japan | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 282 | Dysglycemia | 64 (7) | 40 | 2.0‡ | 6 | 2.0 | 97 | ● | ● | - |

| STARR168 | 2001-2003 | International | ● | 2x2 | ● | ● | - | - | - | 1320 | Dysglycemia | 53 (11) | 55 | 4.2 | 30 | 4.5 | 100 | ● | ● | - |

| STOP-NIDDM169,170 | 1996-1998 | Germany | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 1429 | Dysglycemia | 55 (8) | 51 | 3.3† | 47 | 3.9 | 8 | ● | - | - |

| Safarova et al.171 | 2007-2009 | Russia | ● | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 60 | Pre-existing CVD | 55 (6) | 0 | 3.0 | 40 | 2.8 | 100 | ● | - | - |

| Sander et al. (Cp neg)172,173 | 1995-1998 | Germany | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 147 | Pre-existing CVD | 64 (12) | 44 | 3.0‡ | 9 | 2.0 | 100 | ● | - | - |

| Sander et al. (Cp pos)172,173 | 1995-1998 | Germany | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 125 | Pre-existing CVD | 65 (14) | 43 | 3.0‡ | 19 | 2.0 | 100 | ● | - | - |

| Spring et al.174 | NR | Switzerland | - | 2 | - | - | - | ● | - | 100 | Pre-existing CVD | 67 (11) | 22 | 0.5‡ | 2 | 0.5 | 89 | ● | - | - |

| Stanley et al.175 | 2011-2013 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 50 | Elevated CVD risk | 51 (7) | 16 | 0.5‡ | 1 | 0.5 | 86 | ● | - | - |

| Stanton et al.176 | NR | UK | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 69 | Hypertension | 48 (11) | 41 | 1.0‡ | 1 | 1.0 | 80 | ● | - | - |

| TART177 | 1997-1998 | USA | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 299 | Dysglycemia | 52 (9) | 66 | 2.0 | 12 | 2.0 | 92 | ● | - | - |

| TEAAM178 | 2004-2009 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 308 | General population | 68 (5) | 0 | 3.0‡ | 16 | 3.0 | 99 | ● | - | - |

| TRIPOD179 | 1995-1998 | USA | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 266 | Dysglycemia | 34 (7) | 100 | 2.9 | 0 | 4.0 | 72 | ● | - | - |

| Tasic et al.180 | NR | Serbia | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 40 | Hypertension | 64 (9) | 35 | 0.8‡ | 6 | 0.8 | 100 | ● | - | - |

| VEAPS181 | 1996-1999 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 353 | Hyperlipidemia | 56 (9) | 52 | 3.0† | 18 | 3.0 | 94 | ● | - | - |

| VHAS182,183 | NR | Italy | - | 2 | - | ● | - | - | - | 1414 | Hypertension | 54 (7) | 51 | 2.0‡ | 33 | 4.0 | 27 | - | - | ● |

| VIP184 | 2005-2007 | Netherlands | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 119 | Kidney disease | 53 (12) | 33 | 3.0‡ | 10 | 3.0 | 86 | ● | - | - |

| VITAL185 | 2002-2004 | Netherlands | ● | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 199 | Elevated CVD risk | 49 (12) | 41 | 1.5 | 12 | 2.5 | 99 | ● | - | - |

| WISH186 | 2004-2007 | USA | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 350 | General population | 61 (7) | 100 | 2.7 | 1 | 3.0 | 93 | ● | - | - |

| Yang et al.187 | 2013-2017 | China | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | ● | 119 | Elevated CVD risk | 54 (11) | 72 | 0.5‡ | 0 | 0.5 | 100 | - | - | ● |

| Yun et al.188 | 2010-2013 | China | - | 2 | ● | - | - | - | - | 135 | Pre-existing CVD | 62 (5) | 40 | 2.3† | 23 | 4.5 | 93 | ● | - | - |

| Zou et al.189 | 2010 | China | - | 2 | - | - | ● | - | - | 96 | Elevated CVD risk | 57 (5) | 59 | 1.0‡ | 0 | 1.0 | 89 | ● | - | - |

| Total: 119 trials | 1980-2017 | 30 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 33 | 37 | 100667 | 62 (8) | 41.9 | 3.7 | 12038 | 3.5 | 90 | 91 | 49 | 11 | |||

Table V in the Supplement provides full names of the contributing trials. *Table III in the Supplement provides detailed information on the interventions in each trial. †Mean. ‡Maximum. Abbreviations: CCA-IMT=common-carotid-artery intima-media thickness. cIMT=carotid intima-media thickness. CVD=cardiovascular disease. IPD=individual-participant data. NR=not reported. SD=standard deviation.

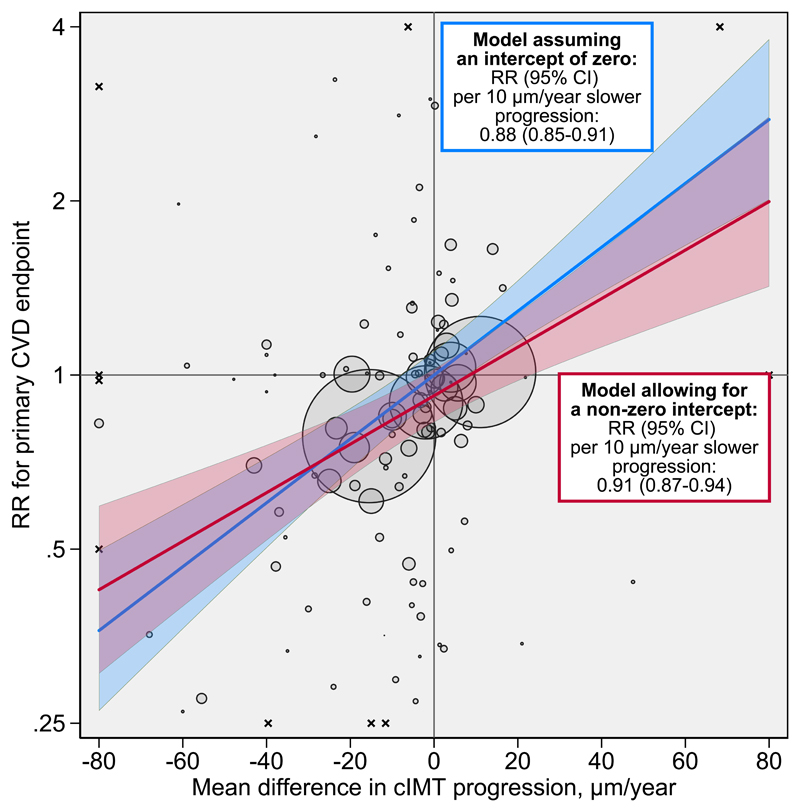

Results of the principal analysis are provided in Figure 1. Across all interventions, in the model assuming an intercept of zero, each 10 μm/year reduction of cIMT progression was associated with a RR for CVD of 0.88 (95% credible interval [CI] 0.85-0.91). In the model allowing for a non-zero intercept, the RR for CVD was 0.91 (0.87-0.94) per 10 μm/year slower cIMT progression, with a further RR of 0.92 (0.87-0.97) achieved independent of cIMT progression. Based on the non-zero intercept model, the proportion of variance in the CVD outcome explained by cIMT progression was 98% albeit with a wide 95% CI (71-100%). Taken together, we estimated that interventions that reduce cIMT progression by 10, 20, 30, or 40 µm/year would yield RRs of 0.84 (0.75-0.93), 0.76 (0.67-0.85), 0.69 (0.59-0.79), or 0.63 (0.52-0.74).

Figure 1. Intervention effects on cIMT progression plotted against intervention effects on risk for the primary CVD endpoint.

The intercept of the primary model was 0.92 (95% CI 0.87-0.97). Each bubble represents a trial. Trials with point estimates outside of this area are indicated with the symbol x. The areas of the bubbles are proportional to the inverse variance of the log relative risk for the primary CVD endpoint. The shaded areas around lines-of-fit are 95% prediction intervals. For purpose of presentation, the graph area was limited to -80 to 80 μm/year on the horizontal axis and 0.25 to 4 on the vertical axis. Abbreviations: CI=credible interval. cIMT=carotid intima-media thickness. CVD=cardiovascular disease. RR=relative risk.

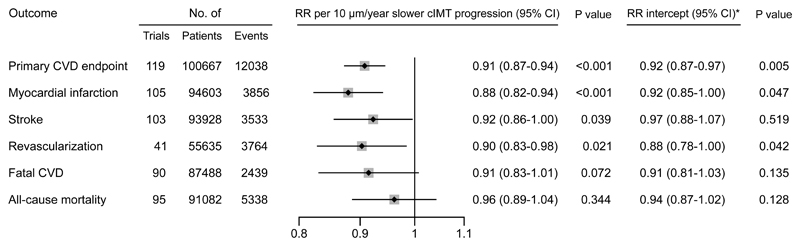

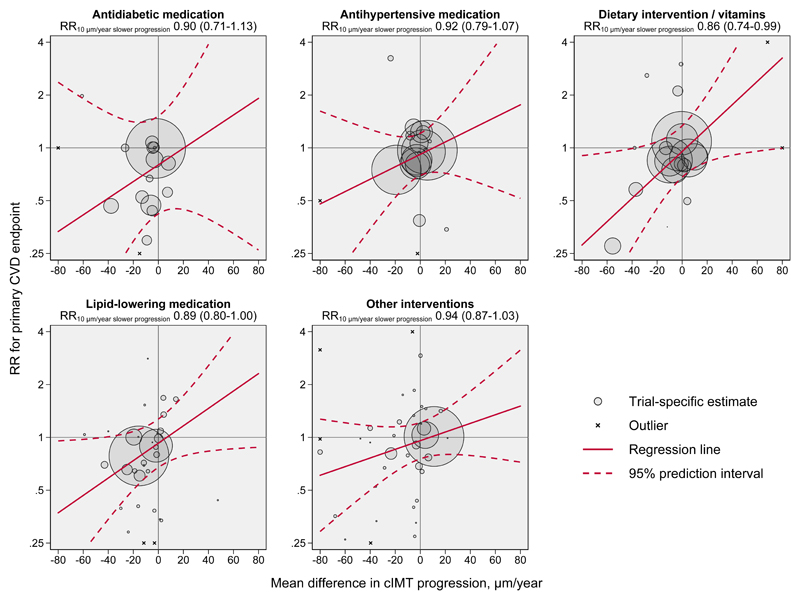

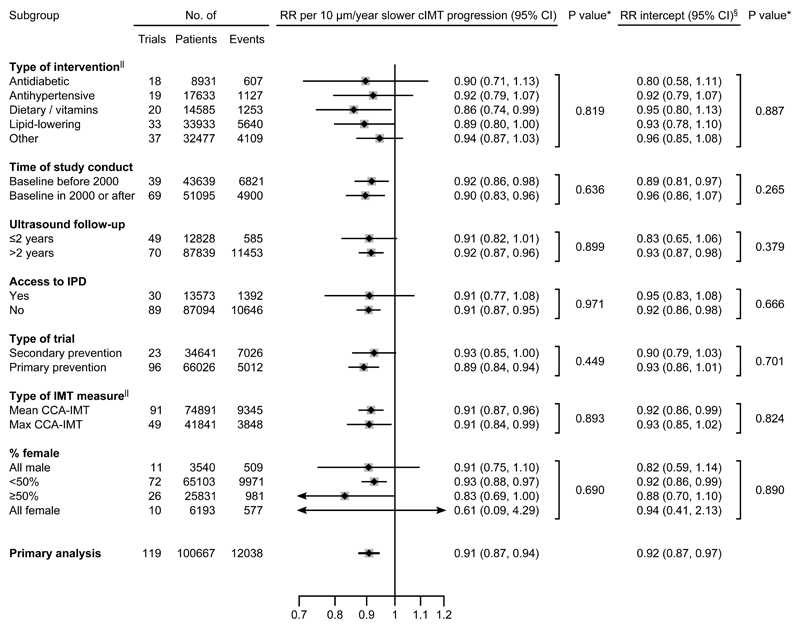

Due to presence of effects on CVD risk unexplained by cIMT progression, subsequent analyses focused on the non-zero intercept model. In outcome-specific analyses (Figure 2), RRs per 10 µm/year slower cIMT progression were 0.88 (0.82-0.94) for myocardial infarction, 0.92 (0.86-1.00) for stroke, 0.90 (0.83-0.98) for revascularization procedures, 0.91 (0.83-1.01) for fatal CVD, and 0.96 (0.89-1.04) for all-cause mortality. There was no evidence for differences in the RR for CVD associated with slower cIMT progression nor in the intercept across trials grouped by intervention type (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Similarly, there was no evidence for differences in these RRs in trials grouped by time of conduct, time to ultrasound follow-up, availability of individual-participant data, primary vs. secondary prevention trials, type of cIMT measurements, and proportion of female patients (Figure 4, P values for heterogeneity >0.05). In a sensitivity analysis that omitted trials with extreme effect sizes (i.e. cIMT progression changes >80 µm/year or RR for CVD <0.25 or >4.0), the RR for CVD per 10 µm/year slower cIMT progression was 0.91 (0.87-0.95). Results were also highly robust across leave-one-out cross-validation analyses (Figure II in the Supplement). Trial-specific estimates are provided in Table IV in the Supplement.

Figure 2. Intervention effects on risk for individual CVD endpoints and all-cause mortality per 10 µm/year slower cIMT progression.

*The RRs for intercepts are the effects achieved independent of cIMT progression. Abbreviations: CI=credible interval. cIMT=carotid intima-media thickness. CVD=cardiovascular disease. RR=relative risk.

Figure 3. Intervention effects on cIMT progression plotted against intervention effects on risk for the primary CVD endpoint, according to type of intervention.

The RRs for intercepts as well as P values for heterogeneity of intercept and slope are provided in Figure 4. The areas of the bubbles are proportional to the inverse variance of the log relative risk for the primary CVD endpoint. For purpose of presentation, the graph area was limited to -80 to 80 μm/year on the horizontal axis and 0.25 to 4 on the vertical axis. Trials with point estimates outside of this area are indicated with the symbol x. Abbreviations: cIMT=carotid intima-media thickness. CVD=cardiovascular disease. RR=relative risk.

Figure 4. Intervention effects on risk for the primary CVD endpoint per 10 µm/year slower cIMT progression, according to trial characteristics.

Abbreviations: CCA-IMT=intima-media thickness of the common-carotid-artery. CI=credible interval. cIMT=carotid intima-media thickness. IPD=individual-participant data. RR=relative risk. *P values for heterogeneity. §The RRs for intercepts are the effects achieved independent of cIMT progression.||Numbers of trials across some subgroups do not sum up to 119 because of missing information or contribution of trials to multiple subgroups.

Discussion

In this large-scale meta-analysis involving data from 119 RCTs and 100,667 patients, we showed that interventions reducing cIMT progression are also likely to reduce CVD event rates (summarized in Figure 5). Specifically, a 10 µm/year slower cIMT progression was associated with a RR of 0.91 (95% CI 0.87-0.94) for the principal outcome of CVD, with the differences in RR for CVD largely explained by the differences in cIMT progression. The same model also indicated a non-zero intercept, overall and for different types of interventions, highlighting that a small but significant proportion of the intervention effect acted independently of cIMT progression. By estimating CVD risk reductions according to specific reductions in cIMT progression, we provide guidance to future trials in the cardiovascular field.5 Results were robust for a range of disease endpoints and across clinically important trial characteristics, including type of intervention or type of cIMT measurement.

Figure 5. Summary of key findings of our study.

Abbreviations: CI=credible interval. cIMT=carotid intima-media thickness. CVD=cardiovascular disease. RCTs= randomized controlled trials.

Exploring the association between cIMT and CVD risk has some history. cIMT measured at a single time-point is associated with incident CVD and provides incremental predictive value over and beyond conventional CVD risk factors.190–192 For cIMT progression over time, our earlier analyses of observational studies within the PROG-IMT collaboration indicated no statistically significant association with subsequent CVD risk in individuals of the general population,2 patients with diabetes mellitus,193 or patients at high CVD risk194. This null association could be explained by the challenges of precisely estimating cIMT progression in individuals over time. In contrast, our present report focuses on groups of patients in RCTs and is therefore better suited to provide answers about the surrogate value of cIMT progression: averaging across patients improves the signal-to-noise ratio, confounders are expected to be balanced due to randomization, trial cohorts might be more homogeneous, and cIMT protocols may be of higher quality in clinical trial settings.

Prior RCT data on cIMT progression as a surrogate marker for CVD risk are limited. Because most RCTs reporting both cIMT and endpoints (with few exceptions63,70,97,127,170) have not been designed as CVD outcome trials and as a range of intervention effect sizes is needed for meaningful results, meta-analysis is the method of choice to investigate this question.195 Three such pooled analyses had been undertaken before. Espeland et al. demonstrated that statin treatment reduced cIMT progression and CVD risk in a concordant manner.4 In a meta-analysis involving 28 RCTs of different intervention types, Goldberger et al. observed an association between reduced cIMT progression and lower risk for non-fatal myocardial infarction, but noted marked between-trials heterogeneity.9 A meta-analysis by Costanzo et al. involving 41 RCTs demonstrated no statistically significant relationship between slower cIMT progression and risk of cardiovascular outcomes.10 Compared to these earlier reports, our meta-analysis stands out by (i) exclusively conducting within-trial comparison (thereby upholding the principle of randomization); (ii) increasing statistical power by involving >5 times as many patients as the previously largest report10; (iii) enhancing validity by accessing patient-level data of 28 trials; and (iv) using modern statistical methods that incorporate uncertainties both around the intervention effects on cIMT progression and CVD risk as well as their within-trial correlation.

What do we know about the suitability of cIMT progression as a surrogate marker for CVD risk? Ultrasound-based cIMT measurement fulfills several requirements of a surrogate marker,196 including (i) high correlation with thickness of the vessel wall measured in histological samples197; (ii) acceptable reproducibility198, which was further enhanced by clear recommendations for measurement and technical improvements199; (iii) close correlation with risk factors and prevalent CVD190–192; (iv) established correlation with atherosclerosis in other vascular beds196; (v) association with occurrence of clinical events190–192; (vi) the ability to change over time2,193; and (vii) the possibility to influence cIMT with interventions200. In the present analysis, we have provided evidence for the last missing requirement not credibly proven by earlier studies, namely that a change in cIMT progression is related to the change in risk of CVD events.

Importantly, using cIMT progression as a surrogate endpoint in future RCTs may facilitate and speed up development and licensing of new therapies. To illustrate this point, we conducted a sample size calculation for a hypothetical future trial. For this calculation, we assumed 80% power, several parameters similar to our individual-participant data (i.e. 2-year cumulative incidence of CVD 6.57%, a standard deviation of cIMT 178 µm, and a correlation between baseline and follow-up cIMT 0.79), no losses to follow-up, and a perfect relationship between treatment effects on cIMT progression and those on the CVD outcome. To have 80% power to detect a hazard ratio of 0.84, a future 2-year CVD outcome trial would require 8,600 patients in each trial arm. In comparison, a future 2-year cIMT progression trial would require 470 patients per trial arm to detect a 10 µm/year reduction in cIMT progression (corresponding to the above hazard ratio) at 2-years, also with a power of 80%. Consequently, a cIMT trial would only require 5.5% of the sample size of a comparable CVD endpoint trial.

In addition to demonstrating the association between intervention effects on cIMT and intervention effects on CVD risk, we found that the regression line had a small but significant non-zero intercept, in the overall analysis and in all subgroups of trials investigated. The non-zero intercept – which indicates that a small proportion of the intervention effect on CVD risk bypasses cIMT – may be explained by “pleiotropic” effects; meaning that the intervention influences the clinical endpoint via multiple pathways. While effects of interventions on the extent of atherosclerosis may be captured by cIMT progression, any effects on other pathophysiological mechanisms related to CVD events, such as endogenous thrombogenesis and fibrinolysis,1 may bypass cIMT progression and thereby lead to a non-zero intercept. Alternative pathways have been described for many major cardiovascular substance groups, including lipid-lowering medications (e.g. statins,1,201,202 fibrates,203 niacin,204 resins,205 and omega-3 fatty acids206), antidiabetic medications (e.g. AMPK activators,207 thiazolidinediones,207 DPP-4 inhibitors,207,208 GLP-1 receptor agonists,207,208 SGLT-2 inhibitors208), or antihypertensive medications (e.g. beta-blockers,209 calcium channel-inhibitors,210,211 angiotensin-II antagonists,212 ACE inhibitors212). Nevertheless, this finding does not negate the main result that an intervention effect on cIMT predicts the effect on CVD risk.

A major strength of our study is that we systematically collated and analyzed worldwide data on cIMT progression and CVD outcomes published up to February 2020. Access to patient-level data allowed us to include hitherto unpublished data and thereby reduce publication bias. Supplementing our analysis with published data enhanced generalizability and statistical power. Strengths of our meta-regression analysis include that it upholds randomization within trials, allows for between-trials heterogeneity, makes no distributional assumption about the true intervention effects on cIMT progression across trials (unlike standard bivariate random-effects meta-analysis), and improved precision by incorporating within-trial correlations of intervention effects on cIMT progression and CVD risk.

Our analysis also has limitations. First, our principal analysis combined trials of varying types of interventions. While we conducted a sensitivity analysis by medication class, further research is required to precisely quantify the differences in the surrogate value of cIMT by intervention type. Second, our analysis involved a broad range of types of trial populations. While sensitivity analysis revealed no evidence for differential effects in the setting of primary vs. secondary prevention trials, further study is needed on specific trial populations, such as patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease. Third, the definition of the primary combined CVD endpoint varied across the included trials. However, the differences were relatively minor (see Table III in the Supplement), so we are confident that this does not constitute a major source of systematic bias. Finally, while ultrasound scanning protocols may have differed across contributing trials – in particular before consensus guidelines were available213, there was no evidence for effect modification by type of cIMT measure or baseline years of the trials.

Conclusions

In conclusion, effects of interventions on cIMT progression and on CVD risk are associated, endorsing the usefulness of cIMT progression as a surrogate marker in clinical trials. Using cIMT progression as a surrogate marker may be a useful tool to guide future development for cardiovascular drugs.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

We analyzed data of 119 randomized controlled trials that involved 100,667 patients and 12,038 incident cardiovascular disease events.

We used a Bayesian meta-regression approach to evaluate progression of carotid intima-media thickness as a surrogate marker for cardiovascular events.

Our analysis revealed a statistically significant association between treatment effects on progression of carotid intima-media thickness and treatment effects on cardiovascular disease risk.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Our paper provides the key missing link supporting the usefulness of carotid intima-media thickness progression as a surrogate marker for cardiovascular disease risk in clinical trials.

Using progression of carotid intima-media thickness as a surrogate endpoint in future randomized controlled trials may facilitate and speed up the development and licensing of new therapies.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) [P 32488]; the Dr.-Johannes-and-Hertha-Tuba Foundation; the German Research Foundation [DFG Lo 1569/2-1 and DFG Lo 1569/2-3]; and the excellence initiative “Competence Centers for Excellent Technologies” (COMET) of the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG) “Research Center of Excellence in Vascular Ageing: Tyrol, VASCage” [K-Project No. 843536], funded by Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Innovation und Technologie (BMVIT), Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Forschung (BMWFW), Wirtschaftsagentur Wien, and Standortagentur Tirol.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CI

credible interval

- cIMT

Carotid intima-media thickness

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- RR

relative risk

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

P. Willeit reports grants from the German Research Foundation DFG, the Austrian Science Fund FWF, the Austrian Research Promotion Agency FFG and the Dr.-Johannes-and-Hertha-Tuba Foundation during the conduct of the study. L. Tschiderer reports grants from the Dr.-Johannes-and-Hertha-Tuba Foundation during the conduct of the study and non-financial support from Sanofi outside the submitted work. E. Allara was supported by a National Institute for Health Research PhD studentship (NIHR BTRU-2014-10024) during the conduction of this study and reports support from EU/EFPIA Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking BigData@Heart grant n° 116074 outside the submitted work. L. Seekircher reports non-financial support from Sanofi outside the submitted work. H.C. Gerstein reports grants from Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Merck, and Abbott, and personal fees from Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Abbott, Novo Nordisk, Merck, Jannsen, Kowa Research Institute, and Cirius outside the submitted work. E. Stroes reports Lecturing/ad-boards fees paid to institution by Amgen, Sanofi-Regeneron, Novartis, Athera, Mylan unrelated to the present work. K. Kapellas reports grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council during the conduct of the study. M. Skilton reports grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia during the conduct of the study. M.G.A. van Vonderen reports grants from Abbott International and Boehringer Ingelheim during the conduct of the study. S. Kiechl reports grants from the Austrian Promotion Agency FFG outside the submitted work. G. Klingenschmid reports non-financial support from Sanofi and Pfizer outside the submitted work. S.E. Kjeldsen reports personal fees from Bayer, Merck KGaA, MSD, Sanofi, and Takeda outside the submitted work. M.H. Olsen reports grants from the Novo Nordic Foundation outside the submitted work. N. Sattar reports personal fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, NAPP Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi, and grants from Boehringer Ingelheim outside the submitted work. M.P.C. Grooteman reports grants from the Dutch Kidney Foundation, Fresenius Medical Care Netherlands BV, Gambro Sweden, the Twiss Fund, and ZON MW during the conduct of the study. P.J. Blankestijn reports grants from the European Commission and other financial activities from Medtronic, Baxter, and Braun outside the submitted work. M.L. Bots reports grants from AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. M.J. Sweeting reports grants from the German Research Foundation during the conduct of the study. S.G. Thompson reports grants from the UK Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, and the German Research Foundation DFG during the conduct of the study. M.W. Lorenz reports grants from the German Research Foundation DFG during the conduct of the study. Other authors have no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011;473:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nature10146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lorenz MW, Polak JF, Kavousi M, Mathiesen EB, Völzke H, Tuomainen T-P, Sander D, Plichart M, Catapano AL, Robertson CM, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness progression to predict cardiovascular events in the general population (the PROG-IMT collaborative project): a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2012;379:2053–2062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60441-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willeit P, Thompson SG, Agewall S, Bergström G, Bickel H, Catapano AL, Chien K-L, de Groot E, Empana J-P, Etgen T, et al. Inflammatory markers and extent and progression of early atherosclerosis: Meta-analysis of individual-participant-data from 20 prospective studies of the PROG-IMT collaboration. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2016;23:194–205. doi: 10.1177/2047487314560664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espeland MA, O'Leary DH, Terry JG, Morgan T, Evans G, Mudra H. Carotid intimal-media thickness as a surrogate for cardiovascular disease events in trials of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2005;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1468-6708-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters SAE, den Ruijter HM, Grobbee DE, Bots ML. Results from a carotid intima-media thickness trial as a decision tool for launching a large-scale morbidity and mortality trial. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:20–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.978114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor AJ, Villines TC, Stanek EJ, Devine PJ, Griffen L, Miller M, Weissman NJ, Turco M. Extended-release niacin or ezetimibe and carotid intima-media thickness. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2113–2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumenthal RS, Michos ED. The HALTS trial--halting atherosclerosis or halted too early? N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2178–2180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0908838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kastelein JJP, Bots ML. Statin therapy with ezetimibe or niacin in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2180–2183. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0908841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberger ZD, Valle JA, Dandekar VK, Chan PS, Ko DT, Nallamothu BK. Are changes in carotid intima-media thickness related to risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction? A critical review and meta-regression analysis. Am Heart J. 2010;160:701–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costanzo P, Perrone-Filardi P, Vassallo E, Paolillo S, Cesarano P, Brevetti G, Chiariello M. Does carotid intima-media thickness regression predict reduction of cardiovascular events? A meta-analysis of 41 randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:2006–2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bots ML, Taylor AJ, Kastelein JJP, Peters SAE, den Ruijter HM, Tegeler CH, Baldassarre D, Stein JH, O'Leary DH, Revkin JH, et al. Rate of change in carotid intima-media thickness and vascular events: meta-analyses can not solve all the issues. A point of view. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1690–1696. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835644dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenz MW, Bickel H, Bots ML, Breteler MMB, Catapano AL, Desvarieux M, Hedblad B, Iglseder B, Johnsen SH, Juraska M, et al. Individual progression of carotid intima media thickness as a surrogate for vascular risk (PROG-IMT): Rationale and design of a meta-analysis project. Am Heart J. 2010;159:730–736.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White IR. Multivariate random-effects meta-analysis. Stata Journal. 2009;9:40–56. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0900900103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels MJ, Hughes MD. Meta-analysis for the evaluation of potential surrogate markers. Stat Med. 1997;16:1965–1982. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19970915)16:17<1965::AID-SIM630>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley RD, Price MJ, Jackson D, Wardle M, Gueyffier F, Wang J, Staessen JA, White IR. Multivariate meta-analysis using individual participant data. Res Synth Methods. 2015;6:157–174. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The ACAPS Group. Rationale and design for the Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Plaque Study (ACAPS) Control Clin Trials. 1992;13:293–314. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(92)90012-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furberg CD, Adams HP, Applegate WB, Byington RP, Espeland MA, Hartwell T, Hunninghake DB, Lefkowitz DS, Probstfield J, Riley WA. Effect of lovastatin on early carotid atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Progression Study (ACAPS) Research Group. Circulation. 1994;90:1679–1687. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.4.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D, Schwenke DC, Banerji M, Bray GA, Buchanan TA, Clement SC, Henry RR, Hodis HN, Kitabchi AE, et al. Pioglitazone for diabetes prevention in impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1104–1115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saremi A, Schwenke DC, Buchanan TA, Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Banerji M, Bray GA, Clement SC, Henry RR, Kitabchi AE, et al. Pioglitazone slows progression of atherosclerosis in prediabetes independent of changes in cardiovascular risk factors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:393–399. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins P, Walters MR, Murray HM, McArthur K, McConnachie A, Lees KR, Dawson J. Allopurinol reduces brachial and central blood pressure, and carotid intima-media thickness progression after ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack: a randomised controlled trial. Heart. 2014;100:1085–1092. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orekhov AN, Sobenin IA, Korneev NV, Kirichenko TV, Myasoedova VA, Melnichenko AA, Balcells M, Edelman ER, Bobryshev YV. Anti-atherosclerotic therapy based on botanicals. Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov. 2013;8:56–66. doi: 10.2174/18722083113079990008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor AJ, Kent SM, Flaherty PJ, Coyle LC, Markwood TT, Vernalis MN. ARBITER: Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol: a randomized trial comparing the effects of atorvastatin and pravastatin on carotid intima medial thickness. Circulation. 2002;106:2055–2060. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000034508.55617.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor AJ, Sullenberger LE, Lee HJ, Lee JK, Grace KA. Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol (ARBITER) 2: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of extended-release niacin on atherosclerosis progression in secondary prevention patients treated with statins. Circulation. 2004;110:3512–3517. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148955.19792.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devine PJ, Turco MA, Taylor AJ. Design and rationale of the ARBITER 6 trial (Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol)-6-HDL and LDL Treatment Strategies in Atherosclerosis (HALTS) Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2007;21:221–225. doi: 10.1007/s10557-007-6020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villines TC, Stanek EJ, Devine PJ, Turco M, Miller M, Weissman NJ, Griffen L, Taylor AJ. The ARBITER 6-HALTS Trial (Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol 6-HDL and LDL Treatment Strategies in Atherosclerosis): final results and the impact of medication adherence, dose, and treatment duration. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2721–2726. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurent S, Boutouyrie P. Dose-dependent arterial destiffening and inward remodeling after olmesartan in hypertensives with metabolic syndrome. Hypertension. 2014;64:709–716. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salonen JT, Nyyssönen K, Salonen R, Lakka HM, Kaikkonen J, Porkkala-Sarataho E, Voutilainen S, Lakka TA, Rissanen T, Leskinen L, et al. Antioxidant Supplementation in Atherosclerosis Prevention (ASAP) study: a randomized trial of the effect of vitamins E and C on 3-year progression of carotid atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 2000;248:377–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rissanen T, Voutilainen S, Nyyssönen K, Salonen R, Salonen JT. Low plasma lycopene concentration is associated with increased intima-media thickness of the carotid artery wall. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2677–2681. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.20.12.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salonen RM, Nyyssönen K, Kaikkonen J, Porkkala-Sarataho E, Voutilainen S, Rissanen TH, Tuomainen T-P, Valkonen V-P, Ristonmaa U, Lakka H-M, et al. Six-year effect of combined vitamin C and E supplementation on atherosclerotic progression: the Antioxidant Supplementation in Atherosclerosis Prevention (ASAP) Study. Circulation. 2003;107:947–953. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000050626.25057.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smilde TJ, Trip MD, Wollersheim H, van Wissen S, Kastelein JJ, Stalenhoef AF. Rationale, Design and Baseline Characteristics of a Clinical Trial Comparing the Effects of Robust vs Conventional Cholesterol Lowering and Intima Media Thickness in Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolaemia : The Atorvastatin versus Simvastatin on Atherosclerosis Progression (ASAP) Study. Clin Drug Investig. 2000;20:67–79. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200020020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smilde TJ, van Wissen S, Wollersheim H, Trip MD, Kastelein JJ, Stalenhoef AF. Effect of aggressive versus conventional lipid lowering on atherosclerosis progression in familial hypercholesterolaemia (ASAP): a prospective, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2001;357:577–581. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zoungas S, McGrath BP, Branley P, Kerr PG, Muske C, Wolfe R, Atkins RC, Nicholls K, Fraenkel M, Hutchison BG, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Atherosclerosis and Folic Acid Supplementation Trial (ASFAST) in chronic renal failure: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1108–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nanayakkara PWB, van Guldener C, ter Wee PM, Scheffer PG, van Ittersum FJ, Twisk JW, Teerlink T, van Dorp W, Stehouwer CDA. Effect of a treatment strategy consisting of pravastatin, vitamin E, and homocysteine lowering on carotid intima-media thickness, endothelial function, and renal function in patients with mild to moderate chronic kidney disease: results from the Anti-Oxidant Therapy in Chronic Renal Insufficiency (ATIC) Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1262–1270. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nanayakkara PWB, Teerlink T, Stehouwer CDA, Allajar D, Spijkerman A, Schalkwijk C, ter Wee PM, van Guldener C. Plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) concentration is independently associated with carotid intima-media thickness and plasma soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1) concentration in patients with mild-to-moderate renal failure. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2230–2236. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahn CM, Hong SJ, Park JH, Kim JS, Lim D-S. Cilostazol reduces the progression of carotid intima-media thickness without increasing the risk of bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndrome during a 2-year follow-up. Heart Vessels. 2011;26:502–510. doi: 10.1007/s00380-010-0093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jalal DI, Decker E, Perrenoud L, Nowak KL, Bispham N, Mehta T, Smits G, You Z, Seals D, Chonchol M, et al. Vascular Function and Uric Acid-Lowering in Stage 3 CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:943–952. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016050521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andrews ES, Perrenoud L, Nowak KL, You Z, Pasch A, Chonchol M, Kendrick J, Jalal D. Examining the effects of uric acid-lowering on markers vascular of calcification and CKD-MBD; A post-hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0205831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedblad B, Wikstrand J, Janzon L, Wedel H, Berglund G. Low-dose metoprolol CR/XL and fluvastatin slow progression of carotid intima-media thickness: Main results from the Beta-Blocker Cholesterol-Lowering Asymptomatic Plaque Study (BCAPS) Circulation. 2001;103:1721–1726. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.13.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bae J-H, Bassenge E, Kim K-Y, Synn Y-C, Park K-R, Schwemmer M. Effects of low-dose atorvastatin on vascular responses in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2004;9:185–192. doi: 10.1177/107424840400900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Dustin L, Mahrer PR, Azen SP, Detrano R, Selhub J, Alaupovic P, Liu C-r, Liu C-h, et al. High-dose B vitamin supplementation and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2009;40:730–736. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.526798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercuri M, Bond MG, Sirtori CR, Veglia F, Crepaldi G, Feruglio FS, Descovich G, Ricci G, Rubba P, Mancini M, et al. Pravastatin reduces carotid intima-media thickness progression in an asymptomatic hypercholesterolemic mediterranean population: the Carotid Atherosclerosis Italian Ultrasound Study. Am J Med. 1996;101:627–634. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(96)00333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Preiss D, Lloyd SM, Ford I, McMurray JJ, Holman RR, Welsh P, Fisher M, Packard CJ, Sattar N. Metformin for non-diabetic patients with coronary heart disease (the CAMERA study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:116–124. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong S, Nam M, Little BB, Paik S, Lee K, Woo J, Kim D, Kang J, Chun M, Park Y. Randomized control trial comparing the effect of cilostazol and aspirin on changes in carotid intima-medial thickness. Heart Vessels. 2019;34:1758–1768. doi: 10.1007/s00380-019-01421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meuwese MC, de Groot E, Duivenvoorden R, Trip MD, Ose L, Maritz FJ, Basart DCG, Kastelein JJP, Habib R, Davidson MH, et al. ACAT inhibition and progression of carotid atherosclerosis in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia: the CAPTIVATE randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1131–1139. doi: 10.1001/jama.301.11.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beishuizen ED, van de Ree MA, Jukema JW, Tamsma JT, van der Vijver JCM, Meinders AE, Putter H, Huisman MV. Two-year statin therapy does not alter the progression of intima-media thickness in patients with type 2 diabetes without manifest cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2887–2892. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mazzone T, Meyer PM, Feinstein SB, Davidson MH, Kondos GT, D’Agostino RB, Perez A, Provost J-C, Haffner SM. Effect of pioglitazone compared with glimepiride on carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2572–2581. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.joc60158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lundby-Christensen L, Tarnow L, Boesgaard TW, Lund SS, Wiinberg N, Perrild H, Krarup T, Snorgaard O, Gade-Rasmussen B, Thorsteinsson B, et al. Metformin versus placebo in combination with insulin analogues in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus-the randomised, blinded Copenhagen Insulin and Metformin Therapy (CIMT) trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e008376. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lundby-Christensen L, Almdal T, Boesgaard T, Breum L, Dunn E, Gade-Rasmussen B, Gluud C, Hedetoft C, Jarloev A, Jensen T, et al. Study rationale and design of the CIMT trial: the Copenhagen Insulin and Metformin Therapy trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11:315–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blankenhorn DH, Selzer RH, Crawford DW, Barth JD, Liu CR, Liu CH, Mack WJ, Alaupovic P. Beneficial effects of colestipol-niacin therapy on the common carotid artery. Two- and four-year reduction of intima-media thickness measured by ultrasound. Circulation. 1993;88:20–28. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.88.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Azen SP, Mack WJ, Cashin-Hemphill L, LaBree L, Shircore AM, Selzer RH, Blankenhorn DH, Hodis HN. Progression of coronary artery disease predicts clinical coronary events. Long-term follow-up from the Cholesterol Lowering Atherosclerosis Study. Circulation. 1996;93:34–41. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cashin-Hemphill L, Mack WJ, Pogoda JM, Sanmarco ME, Azen SP, Blankenhorn DH. Beneficial effects of colestipol-niacin on coronary atherosclerosis. A 4-year follow-up. JAMA. 1990;264:3013–3017. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450230049028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Penne EL, Blankestijn PJ, Bots ML, van den Dorpel MA, Grooteman MP, Nubé MJ, van der Tweel I, ter Wee PM. Effect of increased convective clearance by on-line hemodiafiltration on all cause and cardiovascular mortality in chronic hemodialysis patients - the Dutch CONvective TRAnsport STudy (CONTRAST): rationale and design of a randomised controlled trial ISRCTN38365125. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2005;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1468-6708-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grooteman MPC, van den Dorpel MA, Bots ML, Penne EL, van der Weerd NC, Mazairac AHA, den Hoedt CH, van der Tweel I, Lévesque R, Nubé MJ, et al. Effect of online hemodiafiltration on all-cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1087–1096. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011121140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cao A-H, Wang J, Gao H-Q, Zhang P, Qiu J. Beneficial clinical effects of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract on the progression of carotid atherosclerotic plaques. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015;12:417–423. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamasaki Y, Kim Y-S, Kawamori R. Rationale and protocol of a trial for prevention of diabetic atherosclerosis by using antiplatelet drugs: study of Diabetic Atherosclerosis Prevention by Cilostazol (DAPC study) Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katakami N, Kim Y-S, Kawamori R, Yamasaki Y. The phosphodiesterase inhibitor cilostazol induces regression of carotid atherosclerosis in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus: principal results of the Diabetic Atherosclerosis Prevention by Cilostazol (DAPC) study: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2010;121:2584–2591. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.892414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoogerbrugge N, de Groot E, de Heide LHM, de Ridder MAJ, Birkenhägeri JC, Stijnen T, Jansen H. Doxazosin and hydrochlorothiazide equally affect arterial wall thickness in hypertensive males with hypercholesterolaemia (the DAPHNE study). Doxazosin Atherosclerosis Progression Study in Hypertensives in the Netherlands. Neth J Med. 2002;60:354–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ellingsen I, Seljeflot I, Arnesen H, Tonstad S. Vitamin C consumption is associated with less progression in carotid intima media thickness in elderly men: A 3-year intervention study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;19:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Asci G, Tz H, Ozkahya M, Duman S, Demirci MS, Cirit M, Sipahi S, Dheir H, Bozkurt D, Kircelli F, et al. The impact of membrane permeability and dialysate purity on cardiovascular outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1014–1023. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012090908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ok ES, Asci G, Toz H, Ritz E, Kircelli F, Sever MS, Ozkahya M, Sipahi S, Dheir H, Bozkurt D, et al. Glycated hemoglobin predicts overall and cardiovascular mortality in non-diabetic hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82:173–180. doi: 10.5414/CN108251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, Azen SP, Stanczyk FZ, Hwang-Levine J, Budoff MJ, Henderson VW. Methods and baseline cardiovascular data from the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol testing the menopausal hormone timing hypothesis. Menopause. 2015;22:391–401. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, Shoupe D, Budoff MJ, Hwang-Levine J, Li Y, Feng M, Dustin L, Kono N, et al. Vascular Effects of Early versus Late Postmenopausal Treatment with Estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1221–1231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zanchetti A, Bond MG, Hennig M, Neiss A, Mancia G, Dal Palù C, Hansson L, Magnani B, Rahn K-H, Reid JL, et al. Calcium antagonist lacidipine slows down progression of asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis: principal results of the European Lacidipine Study on Atherosclerosis (ELSA), a randomized, double-blind, long-term trial. Circulation. 2002;106:2422–2427. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000039288.86470.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wiklund O, Hulthe J, Wikstrand J, Schmidt C, Olofsson S-O, Bondjers G. Effect of controlled release/extended release metoprolol on carotid intima-media thickness in patients with hypercholesterolemia: a 3-year randomized study. Stroke. 2002;33:572–577. doi: 10.1161/hs0202.102332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Hinderliter A, Watkins LL, Craighead L, Lin P-H, Caccia C, Johnson J, Waugh R, Sherwood A. Effects of the DASH diet alone and in combination with exercise and weight loss on blood pressure and cardiovascular biomarkers in men and women with high blood pressure: the ENCORE study. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:126–135. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Craighead L, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Browndyke JN, Strauman TA, Sherwood A. Effects of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet, exercise, and caloric restriction on neurocognition in overweight adults with high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2010;55:1331–1338. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kastelein JJP, Akdim F, Stroes ESG, Zwinderman AH, Bots ML, Stalenhoef AFH, Visseren FLJ, Sijbrands EJG, Trip MD, Stein EA, et al. Simvastatin with or without ezetimibe in familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1431–1443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Lobo RA, Shoupe D, Sevanian A, Mahrer PR, Selzer RH, Liu Cr CR, Liu Ch CH, Azen SP. Estrogen in the prevention of atherosclerosis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:939–953. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keech A, Simes RJ, Barter P, Best J, Scott R, Taskinen MR, Forder P, Pillai A, Davis T, Glasziou P, et al. Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1849–1861. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hiukka A, Westerbacka J, Leinonen ES, Watanabe H, Wiklund O, Hulten LM, Salonen JT, Tuomainen T-P, Yki-Järvinen H, Keech AC, et al. Long-term effects of fenofibrate on carotid intima-media thickness and augmentation index in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2190–2197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davidson M, Rosenson RS, Maki KC, Nicholls SJ, Ballantyne CM, Setze C, Carlson DM, Stolzenbach J. Study design, rationale, and baseline characteristics: evaluation of fenofibric acid on carotid intima-media thickness in patients with type IIb dyslipidemia with residual risk in addition to atorvastatin therapy (FIRST) trial. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2012;26:349–358. doi: 10.1007/s10557-012-6395-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davidson MH, Rosenson RS, Maki KC, Nicholls SJ, Ballantyne CM, Mazzone T, Carlson DM, Williams LA, Kelly MT, Camp HS, et al. Effects of fenofibric acid on carotid intima-media thickness in patients with mixed dyslipidemia on atorvastatin therapy: randomized, placebo-controlled study (FIRST) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1298–1306. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burggraaf B, van Breukelen-van der Stoep DF, de Vries MA, Klop B, van Zeben J, van de Geijn G-JM, van der Meulen N, Birnie E, Prinzen L, Castro Cabezas M. Progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis and the metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis. 2018;271:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Burggraaf B, van Breukelen-van der Stoep DF, de Vries MA, Klop B, Liem AH, van de Geijn G-JM, van der Meulen N, Birnie E, van der Zwan EM, van Zeben J, et al. Effect of a treat-to-target intervention of cardiovascular risk factors on subclinical and clinical atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:335–341. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lonn EM, Bosch J, Diaz R, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Ramachandran A, Hâncu N, Hanefeld M, Krum H, Ryden L, Smith S, et al. Effect of insulin glargine and n-3FA on carotid intima-media thickness in people with dysglycemia at high risk for cardiovascular events: the glucose reduction and atherosclerosis continuing evaluation study (ORIGIN-GRACE) Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2466–2474. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gresele P, Migliacci R, Arosio E, Bonizzoni E, Minuz P, Violi F. Effect on walking distance and atherosclerosis progression of a nitric oxide-donating agent in intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:1622–8, 1628.e1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Held C, Sumner G, Sheridan P, McQueen M, Smith S, Dagenais G, Yusuf S, Lonn E. Correlations between plasma homocysteine and folate concentrations and carotid atherosclerosis in high-risk individuals: baseline data from the Homocysteine and Atherosclerosis Reduction Trial (HART) Vasc Med. 2008;13:245–253. doi: 10.1177/1358863X08092102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, Furberg C, Herrington D, Riggs B, Vittinghoff E. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605–613. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Byington RP, Furberg CD, Herrington DM, Herd JA, Hunninghake D, Lowery M, Riley W, Craven T, Chaput L, Ireland CC, et al. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on progression of carotid atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women with heart disease: HERS B-mode substudy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1692–1697. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000033514.79653.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anderssen SA, Hjelstuen AK, Hjermann I, Bjerkan K, Holme I. Fluvastatin and lifestyle modification for reduction of carotid intima-media thickness and left ventricular mass progression in drug-treated hypertensives. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Simon A, Gariépy J, Moyse D, Levenson J. Differential effects of nifedipine and co-amilozide on the progression of early carotid wall changes. Circulation. 2001;103:2949–2954. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.24.2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brown MJ, Palmer CR, Castaigne A, de Leeuw PW, Mancia G, Rosenthal T, Ruilope LM. Morbidity and mortality in patients randomised to double-blind treatment with a long-acting calcium-channel blocker or diuretic in the International Nifedipine GITS study: Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT) Lancet. 2000;356:366–372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Taddei S, Ghiadoni L, Salvetti A. Current treatment of patients with hypertension: therapeutic implications of INSIGHT. Drugs. 2003;63:1435–1444. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363140-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hosomi N, Nagai Y, Kohriyama T, Ohtsuki T, Aoki S, Nezu T, Maruyama H, Sunami N, Yokota C, Kitagawa K, et al. The Japan Statin Treatment Against Recurrent Stroke (J-STARS): A Multicenter, Randomized, Open-label, Parallel-group Study. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Toyoda K, Minematsu K, Yasaka M, Nagai Y, Hosomi N, Origasa H, Kitagawa K, Uchiyama S, Koga M, Matsumoto M. The Japan Statin Treatment Against Recurrent Stroke (J-STARS) Echo Study: Rationale and Trial Protocol. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:595–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.11.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Koga M, Toyoda K, Minematsu K, Yasaka M, Nagai Y, Aoki S, Nezu T, Hosomi N, Kagimura T, Origasa H, et al. Long-Term Effect of Pravastatin on Carotid Intima-Media Complex Thickness: The J-STARS Echo Study (Japan Statin Treatment Against Recurrent Stroke) Stroke. 2018;49:107–113. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wada S, Koga M, Toyoda K, Minematsu K, Yasaka M, Nagai Y, Aoki S, Nezu T, Hosomi N, Kagimura T, et al. Factors Associated with Intima-Media Complex Thickness of the Common Carotid Artery in Japanese Noncardioembolic Stroke Patients with Hyperlipidemia: The J-STARS Echo Study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2018;25:359–373. doi: 10.5551/jat.41533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]