Abstract

Objective:

To identify factors influencing dietary behaviours in urban food environments in Africa and identify areas for future research.

Design:

We systematically reviewed published/grey literature (protocol CRD4201706893). Findings were compiled into a map using a socio-ecological model on four environmental levels: individual, social, physical and macro.

Setting:

Urban food environments in Africa.

Participants:

Studies involving adolescents and adults (11–70 years, male/female).

Results:

Thirty-nine studies were included (six adolescent, fifteen adolescent/adult combined and eighteen adult). Quantitative methods were most common (twenty-eight quantitative, nine qualitative and two mixed methods). Studies were from fifteen African countries. Seventy-seven factors influencing dietary behaviours were identified, with two-thirds at the individual level (45/77). Factors in the social (11/77), physical (12/77) and macro (9/77) environments were investigated less. Individual-level factors that specifically emerged for adolescents included self-esteem, body satisfaction, dieting, spoken language, school attendance, gender, body composition, pubertal development, BMI and fat mass. Studies involving adolescents investigated social environment-level factors more, for example, sharing food with friends. The physical food environment was more commonly explored in adults, for example, convenience/availability of food. Macro-level factors associated with dietary behaviours were food/drink advertising, religion and food prices. Factors associated with dietary behaviour were broadly similar for men and women.

Conclusions:

The dominance of studies exploring individual-level factors suggests a need for research to explore how social, physical and macro-level environments drive dietary behaviours of adolescents and adults in urban Africa. More studies are needed for adolescents and men, and studies widening the geographical scope to encompass all African countries.

Keywords: Dietary behaviour, Africa, Urban, Food environment

Rapid demographic change in Africa, partly driven by increasing migration of individuals into cities, has changed people’s food environments and dietary habits(1). Economic development has increased access to food markets selling energy-dense processed foods at low prices and decreased the price of certain foods such as vegetable oils(2). Modification of diet structure towards a higher intake of energy-dense foods (especially from fat and added sugars), a higher consumption of processed foods(3), animal source foods, sugar and saturated fats, and a lower intake of complex carbohydrates, dietary fibre, fruit and vegetables has led to a significant change in diet quality over the past 20 years(4). The nutrition transition in urban areas of many African countries has resulted in a ‘double burden of disease’ in which there is an increased prevalence of nutrition-related non-communicable diseases (NR-NCD) alongside existing communicable diseases. Although obesity prevalence is higher among African women than men, there has been a rise in both(5,6). Children and adolescents are an important group to target in the prevention of overweight and obesity(7). In 2010, of the 43 million children estimated to be overweight and obesity, 35 million were from low- and middle-income countries(7). The prevalence of overweight and obesity in children in Africa is expected to increase from 8·5 % (2010) to a projected 12·7 % by 2020. By understanding this shift in nutrition and disease, new NR-NCD prevention strategies that account for the factors driving dietary behaviours can be developed across the life course.

A mapping review was previously conducted in 2015(8) to identify drivers of dietary behaviours specifically in adult women within urban settings in African countries and identify priorities for future research. However, the increasing evidence that the overweight and obesity burden is spread more widely across population groups indicates the need for a broader review. Hence, this systematic review mapped the factors influencing dietary behaviours of adolescents and adults of both genders in African urban food environments and identified areas for future research.

Methods

A systematic mapping review(9) was conducted to map existing literature regarding factors influencing dietary behaviours in urban Africa. Systematic mapping reviews are often conducted as a prelude to further research and are imperative in the identification of research gaps. Prior to conducting the review, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and MEDLINE were searched to ensure that no similar reviews were underway or had been conducted beyond the original mapping review(8). A review protocol was produced to ensure transparency in the review methodology and then registered with the PROSPERO database of existing and on-going systematic reviews (registration number CRD4201706893).

To determine appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review, the Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type tool was used(10). Criteria used in the original review were modified to acknowledge the additional population groups (adolescents and adult men)(8); otherwise, the same processes were applied to ensure compatibility.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The original review conducted in 2015 investigated women aged 18–70 years living in urban Africa from 1971 to April 2015(8). This current review synthesised recent research in this same group, published since April 2015 to April 2019, and included men (18–70 years) and female/male adolescents (11–17 years), between 1971 and April 2019. All participants were living in urban Africa, those from rural settings were excluded, as were studies with participants <11 years or >70 years. Participants with a clinical diagnosis related to NR-NCD were excluded; excluding studies with specific diseases also ensured that the included studies were of healthy African populations and not specific clinical sub-groups. The phenomenon of interest was defined as factors influencing dietary behaviours. This was purposely broad to enable sensitive mapping of all available literature. Furthermore, studies including African-Americans or African migrants to non-African countries were excluded on the basis of setting. Studies measuring the effect of factors on dietary behaviours were included, but studies that focused on the relationship between diet and diet-related diseases were excluded given the focus on factors influencing dietary behaviour rather than their effect on specific diseases.

To ensure broad coverage of research, all types of study designs were included, that is, randomised controlled trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, ecological/observational studies, reviews and meta-analyses. All publication types were included, provided they were in English or French. Languages were chosen to acknowledge the main publishing languages in Africa.

For adult men and adolescents, any appropriate study from 1971 to 2019 was included. For adult women, studies published since the previous search (April 2015–April 2019) were retrieved. The chosen 1971 start date reflected the earliest appearance of relevant publications concerning health behaviour in the context of the epidemiological transition(11) on the nominated databases and search engines. The primary outcome was dietary behaviour, including macronutrient, food item and food diversity intake, as well as eating habits, preferences, choices and feeding-related mannerisms. Macronutrients were included because of the review’s focus on urban settings where dietary transition is more likely to be associated with dietary change from the nutrition transition, which is associated with increased consumption of fat, vegetable and edible fat and increased added sugar(6).

Search strategy

Electronic searches were conducted across six key databases: EMBASE, MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ASSIA and African Index Medicus. The search strategy replicated that used in the previous review with the additional inclusion of search terms representing adult men and adolescents(8). An example of a search strategy used for these databases can be found in Supplemental Table 1 in the online supplementary material. Grey literature was explored through the WHO International Trials Registry Index and Thesis (UK and Ireland) Database.

Reference lists for the seventeen studies included in the initial review were examined, and citation tracking using Google Scholar (through Publish or Perish™) was also conducted. Forward and backward citation tracking sought to ensure that no important studies were missed and that representation of appropriate literature was maximised. Reference lists of newly identified included studies, reflecting the expansion of date range and populations of interest, were also reviewed. The dual approach of subject searching and follow-up citation tracking was considered to provide sufficient coverage of the relevant literature(12).

Study selection

Studies that fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria for title and abstract then underwent full-text screening by two reviewers (A.M./F.G.). Duplicates were removed prior to full-text screening. A second reviewer (H.O.-K./M.H.) assessed 10 % of excluded studies at two stages: the title and abstract stage and the full-text search stage. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. If no agreement was reached, a third reviewer also assessed the study.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment is not a mandatory requirement for a mapping review(9). However, by incorporating it into the review methodology, it enhances the credibility of the review’s findings and is particularly useful in documenting uncertainties that persist in relation to previous research(9). Quality assessment was conducted with a validated tool(13) for qualitative and quantitative studies by two reviewers independently (A.M., M.W. or F.G.).

Data extraction

Data were extracted from included studies by one of two principal reviewers (A.M. or F.G.) supported by a second reviewer (H.O.-K. or M.H.) and was checked by a member of the review team (M.W.). As the aim of this mapping review was to map the factors influencing dietary behaviours of adolescents and adults living in African urban food environments and identify areas for future research, it was decided to include all factors reported by authors and not to restrict the review to reporting factors only where a statistical relationship or association had been demonstrated.

Data synthesis

There are different approaches to updating a review. In this review, the new findings were integrated with those of the original review at the synthesis level(14) in order to present all the evidence for men, women and adolescents for the same timescale. In order to determine which factors influence dietary behaviours in the three population sub-groups, factors influencing dietary behaviours for adults and adolescents of all thirty-eight studies were mapped to the socio-ecological model defined by Story et al. (15). Factors were placed within four broad levels: individual, social environment, physical environment and macro-environment and assigned to an appropriate sub-level. For novel factors that emerged, it was decided within the team where to place it in the aforementioned socio-ecological model, similar to the original review(8). Reporting of the review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist(16).

Results

Search results

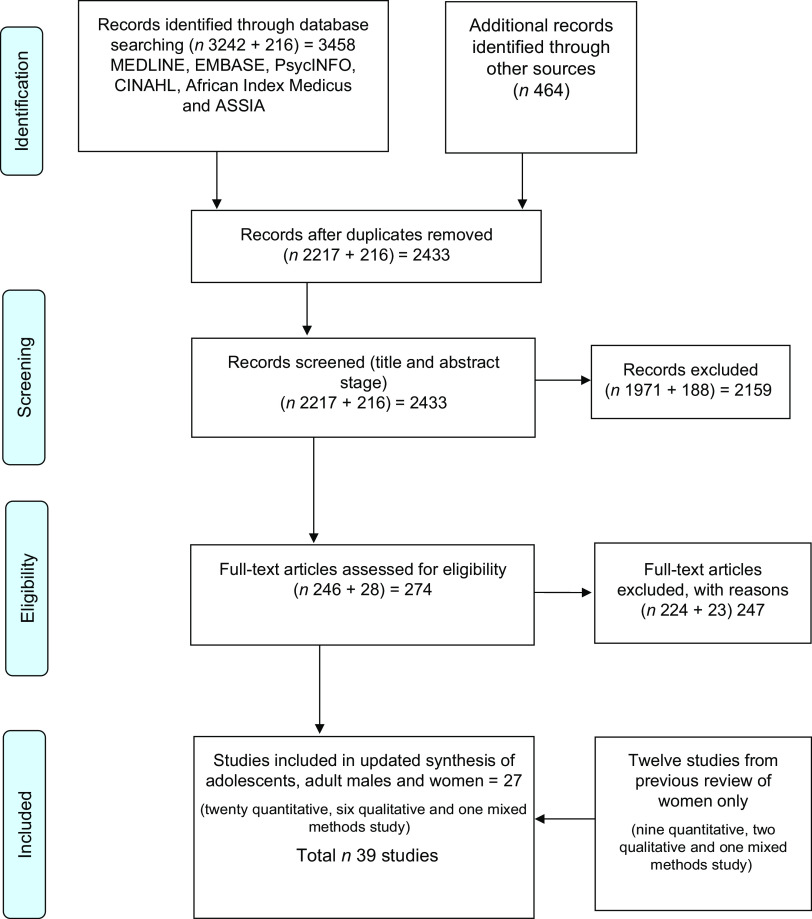

The search yielded 2433 title and abstract records after duplicates were removed (Fig. 1); 274 records remained for full-text retrieval, at which stage 247 records were excluded, leaving twenty-seven studies for inclusion for studies of adolescents, men and women (from 2015). Twelve studies from an earlier review of women only aged 18–70 years (1971–2015) were integrated in the review findings, giving a total of thirty-nine studies.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram showing the selection of studies for the present systematic mapping review

Description of included studies

Thirty-nine studies were included in the final data synthesis (Table 1), of which nineteen were conducted in lower middle-income countries(17): Cape Verde, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria and Tunisia. Thirteen studies were conducted in upper middle-income countries: Botswana, Mauritius and South Africa, and one study was undertaken in the Seychelles (high-income country). Only six studies were undertaken in low-income countries: Burkina Faso, Benin, Niger and Tanzania (Table 1). Over half of studies were conducted in Ghana and Morocco (six studies each) or South Africa (ten studies).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies (39 studies and 45 records)

| Study | Design, method | Country | Income level | Sample characteristics | Sample size | Sampling | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative studies | Gender | Age (range) | n/households | ||||

| Batnitzky(18) | Field study, semi-structured interviews, observation | Morocco | Lower middle | Mixed | 20+ years (adult) | 1789 | Unclear – individuals then households |

| Boatemaa et al. (19) | Cross-sectional, interviews | Ghana | Lower middle | Mixed | 15–35 years and 35+ years (adolescent and adult) | 30 | Purposive sampling |

| Brown et al. (20) | Cross-sectional, focus groups | Botswana | Upper middle | Mixed | 12–18 years (adolescent) and adult (age range not specified) | 72–132 (adolescents) parents unknown | Sampling of schools with differing tuition status |

| Craveiro et al. (21) | Observational, focus groups | Cape Verde | Lower middle | Mixed | 18–41 years (adult) | 48 | Opportunistic sampling using probabilistic sampling with random selection |

| Draper et al. (22) | Observational, focus groups | South Africa | Upper middle | Female | 24–51 years (adult) | 21 | Convenience sampling |

| Legwegoh(23) and Legwegoh & Hovorka(24) | Case-study, interview | Botswana | Upper middle | Mixed | 20–65 years (adult) | 40 households | Purposive sample, stratified based on household-head gender and socio-economic status |

| Rguibi & Behalsen(25) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire via interview | Morocco | Lower middle | Female | 15–70 years (adolescent and adult) | 249 | Convenience. Women visiting primary care centres |

| Sedibe et al. (26) and Voorend et al. (27) | Observational, duo-interviews | South Africa | Upper middle | Female | 15–21 years (adolescent) | 58 | Voluntary participation following researcher involvement in school |

| Quantitative studies | |||||||

| Agbozo et al. (28) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Ghana | Lower middle | Mixed | 60–70 years (adult) | 120 | Purposive sample from four peri-urban communities |

| Amenyah & Michels((29) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Ghana | Lower middle | Mixed | 11–18 years (adolescent) | 370 | Random selection, five secondary schools |

| Aounallah-Skhiri et al. (30) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Tunisia | Lower middle | Mixed | 15–19 years (adolescent and adult) | 1019 | Clustered random sampling from three regions of Tunisia |

| Becquey et al. (31) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Burkina Faso | Low | Mixed | 15–65 years (adolescent and adult) | 1072 | Purposive random sampling |

| Cisse-Egbuonye et al. (32) | Quantitative, cross-sectional | Niger | Low income | Female | 15–49 years (adolescent and adult) | 3360 | Randomly selected household heads in purposive sample |

| Codjoe et al. (33) | Cross-sectional | Ghana | Lower middle income | Mixed | 15–59 years (adolescent and adult males), 15–49 years (adolescent and adult) | 452 households | Purposive sampling according to age from a larger data set |

| El Ansari & Berg-Beckhoff(34) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Egypt | Lower middle | Mixed | 16–30 years (adolescent and adults) | 2810 | Voluntary questionnaire distributed to students attending lectures of randomly selected courses |

| Feeley et al. (35) | Cohort, questionnaire | South Africa | Upper middle | Mixed | 13–17 years (adolescent) | 1298 | Cohort selection sampling-recruitment of all singleton births that occurred over a 7-week period in public delivery centres from all population groups |

| Fokeena & Jeewon(36) | Cross-sectional, self-reported questionnaires | Mauritius | Upper middle | Mixed | 12–15 years (adolescent) | 200 | Multistage sampling, schools randomly selected from four educational zones of Mauritius and sample taken from three of these schools |

| Glozah & Pevalin(37) | Cross-sectional, self-reported questionnaires | Ghana | Lower middle income | Mixed | 14–21 years (adolescent and adult) | 770 | Participants selected at random from four senior high schools that were purposively selected in Accra |

| Gitau et al. (38) | Longitudinal, self-reported questionnaire | South Africa | Upper middle | Males | 13–17 years (adolescent) | 391 | Stratified convenience sample |

| Hattingh et al. (39,40,41) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | South Africa | Upper middle | Female | 25–44 years (adult) | 488 | Stratified random according to number of plots in each settlement |

| Jafri et al. (42) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Morocco | Lower middle | Female | 18+ years (adult) | 401 | Multistage cluster. Households randomly selected within clusters |

| Kiboi et al. (43) | Cross-sectional, structured interviews, questionnaire | Kenya | Lower middle | Female | 16–49 years (adolescent and adult) | 254 | Purposive sampling at antenatal clinic in a hospital over 1 month |

| Landais(44) and Landais et al. (45) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Morocco | Lower middle | Female | 20–49 years (adult) | 894 | Multistage cluster. Households then addresses randomly selected from enumeration areas |

| López et al. (46) | Observational, 3 × 24 h dietary recalls | Morocco | Lower middle | Mixed | 15–20 years (adolescent and adult) | 327 | All students enrolled in high schools year 2007–2008 completed survey |

| Mayén et al. (47) | Cross-sectional, survey | Seychelles | High | Mixed | 25–64 years (adult) | 2004 | National surveys, random sample drawn from entire population |

| Mbochi et al. (48) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Kenya | Lower middle | Female | 25–54 years (adult) | 365 | Stratified random according to number of women in each socio-economic stratum |

| Mogre et al. (49) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Ghana | Lower middle | Mixed | 20–60 years (adult) | 235 | Stratified random based on number of employees in each department |

| Njelekela et al. (50) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Tanzania | Low | Mixed | 45–66 years (adult) | 209 | Random stratified selection from list of adult residents, strata: gender |

| Onyiriuka et al. (51) | Cross-sectional, structured questionnaire | Nigeria | Lower middle | Female | 12–19 years (adolescent and adult) | 2097 | Random selection by ballot from four all-girls schools, no sampling performed as designed to include all students |

| Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52) | Cross-sectional, survey | South Africa | Upper middle | Mixed | >50 years (adult) | 3840 | National population based sample, from original study (SAGE; two-stage probability sample) |

| Savy et al. (53) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Burkina Faso | Low | Female | 29–50 years (adult) | 481 | Random, from a database containing an exhaustive list of inhabitants |

| Sodjinou et al. (54,55) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Benin | Low | Mixed | 25–60 years (adult) | 200 | Multistage cluster. Neighbourhoods, households, then individuals randomly selected |

| Soualem et al. (56) | Cross-sectional, questionnaires | Morocco | Lower middle | Mixed | 12–16 years (adolescent) | 190 | Random selection from five schools in Gharb region |

| Steyn et al. (57) | Cross-sectional, structured interview | South Africa | Upper middle | Mixed | ≥16 years (adolescent and adult) | 3287 | Stratified sampling of annual survey data |

| Van Zyl et al. (58) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | South Africa | Upper middle | Mixed | 19–30 years (adult) | 341 | Convenience, residents of Johannesburg visiting a mall |

| Waswa(59) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire | Kenya | Lower middle | Female | 20–25 years (adult) | 260 | Stratified random according to university department size including each year |

| Zeba et al. (60) | Cross-sectional, questionnaires | Burkina Faso | Low | Mixed | 25–60 years (adult) | 110 | Stratified random sampling, stratification by income |

| Mixed-methods | |||||||

| Charlton et al. (61) | Cross-sectional, questionnaire; focus groups | South Africa | Upper middle | Female | Questionnaire: 17–50 years (adult and adolescent); Focus groups: 18–49 years (adult and adolescent) | Questionnaire: 394; focus groups: 39 | Convenience, according to age and gender |

| Pradeilles(62) | Cross-sectional, questionnaires; focus groups | South Africa | Upper middle | Mixed | Questionnaire: 17–19 years (adult and adolescent); Focus groups: 18 years+ (adult) | Questionnaire: 631; focus groups: 51 | Cohort selection sampling-recruitment of all singleton births that occurred over a 7-week period in public delivery centres from all population groups; Snowball sampling |

Of the thirty-nine studies, eight were qualitative (ten records)(18–27), twenty-nine (thirty-three records) were quantitative(28–60) and two used mixed methods(61,62) studies. The qualitative and quantitative data in the latter were extracted separately in order to generate distinct quality assessment scores. Of the thirty-nine studies, thirty-two were cross-sectional studies(18–20,25,28–37,39–45,47–62), four were observational(18,21,26,27,46), two used a longitudinal design(38) and one was a detailed case study(23,24). The methodology consisted of interviews and focus groups to obtain qualitative data, whereas self-administered or interviewer-led surveys were mostly used for quantitative studies.

Quality assessment

In summary, while most of the quantitative studies scored high on criteria such as appropriate study designs, question/objective sufficiently described and data analysis clearly described, these studies did not report on controlling for confounders or estimation of variance in the main results.

Similarly, in all qualitative studies, authors failed to report on procedures to establish credibility or show reflexivity. The individual aspects of the quality assessment conducted for all thirty-nine included studies (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

Factors influencing diet or dietary behaviour in urban Africa

In total, seventy-seven factors influencing dietary behaviours were identified, with two-thirds at the individual level (45/77). Factors in the social (11/77), physical (12/77) and macro (9/77) environments were investigated less. Slightly more studies investigating social-level factors studied adolescent populations (Table 2). The configuration of dietary factors in adult men paralleled that of adult women, probably because relevant included studies examined a mixed adult population. In all population groups, the individual and household factors level of the socio-ecological model was the most studied.

Table 2.

Factors in urban African food environments influencing dietary behaviours in the included studies (n 39)

| Level | Sub-level | Factor (no. of studies) | Dietary behaviour | Evidence | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual and household (45) | Cognitions (12) | Taste (4) | Dietary intake | Pradeilles(62)MM, Sedibe et al. (26)QL and Voorend et al. (27)QL | Mixed adolescent adult; Female adolescent |

| Fast-food intake | Van Zyl et al. (58)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Food choice | Charlton et al. (61)MM | Female adolescent and adult | |||

| Preferences (1) | Food choice | Boatemma et al. (19)QL | Mixed adolescent and adult; female adolescent | ||

| Hunger/not hungry/lack of appetite (6) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN * | Mixed adult | ||

| Food intake | Agbozo et al. (28)QN *, Mogre et al. (49)QN * and Waswa(59)QN * | Mixed adult; Mixed adult; Female adult | |||

| Dietary diversity | Cisse-Egbuonye et al. (32)QN † | Female adolescent and adult | |||

| Skipping meals | Onyiriuka et al. (51)QN † | Female adolescent | |||

| Mood (1) | Food intake | Waswa(59)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Subjective health status (4) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN ‡ and Mogre et al. (49)QN * | Mixed adult; Mixed adult | ||

| Food choice | Agbozo et al. (28)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Dietary intake/Disordered eating | Amenyah & Michels(29)QN * | Mixed adolescent | |||

| Perceived stress (1) | Dietary intake | El Ansari & Berg-Beckhoff(34)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| Self-esteem (1) | Disordered eating | Gitau et al. (38)QN ‡ | Males adolescent | ||

| Body satisfaction (1) | Disordered eating | Gitau et al. (38)QN ‡ | Males adolescent | ||

| Body image perception (1) | Food intake | Waswa(59)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Food knowledge (3) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN † | Mixed adult | ||

| Food choice | Agbozo et al. (28)QN ‡ | Mixed adult | |||

| Food intake | Waswa(59)QN * | Female adult | |||

| Perception of diet quality (1) | Dietary diversity | Becquey et al. (31)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| Perception of diet quantity (1) | Dietary diversity | Becquey et al. (31)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| Lifestyle/behaviours (15) | Dieting (1) | Dietary habits | Sedibe et al. (26)/Voorend et al. (27)QL | Female adolescent | |

| Skipping meals (1) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Snacking (1) | Dietary diversity | Becquey et al. (31)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| Habit/routine (1) | Food choice | Charlton et al. (61)MM | Female adolescent and adult | ||

| Household dietary diversity (1) | Dietary diversity | Cisse-Egbuonye et al. (32)QN † | Female adolescent and adult | ||

| Processed food consumption (1) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Eating out occasions (1) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Eating three daily meals (1) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Overall lifestyle (1) | Diet quality | Sodjinou et al. (54)/Sodjinou et al. (55)QN † | Mixed adult | ||

| Spoken language (1) | Food quality | Soualem et al. (56)QN † | Mixed Adolescent | ||

| Time limitations (5) | Dietary intake | Legwegoh(23)/Legwegoh & Hovorka(24)QN | Mixed adult | ||

| Fast-food intake | Van Zyl et al. (58)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Food choice | Brown et al. (20)QL | Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Unhealthy food intake | Craveiro et al. (21)QL | Mixed adult | |||

| Skipping meal | Mogre et al. (49)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Quality of life (1) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN ‡ | Mixed adult | ||

| Tobacco use (2) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN † | Mixed adult | ||

| Diet quality | Sodjinou et al. (54)/Sodjinou et al. (55)QN † | Mixed adult | |||

| Alcohol use (2) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN * | Mixed adult | ||

| Diet quality | Sodjinou et al. (54)/Sodjinou et al. (55)QN † | Mixed adult | |||

| Physical activity (5) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN * | Mixed adult | ||

| Energy intake | Hattingh et al. (39) * ,(40) * ,(41)QN * | Female adult | |||

| Dietary intake | Becquey et al. (31)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Dietary patterns | Zeba et al. (60)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Dietary quality | Sodjinou et al. (54)/Sodjinou et al. (55)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Biological (9) | Morbidity (1) | Dietary diversity | Kiboi et al. (43)QN † | Female adolescent and adult | |

| Age (11) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN ‡ | Female adult | ||

| Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN ‡ | Mixed adult | |||

| Dietary quality | Soualem et al. (56)QN * | Mixed adolescent | |||

| Dietary diversity | Becquey et al. (31)QN *, Savy et al. (53)QN *, Codjoe et al. (33)QN ‡ and Cisse-Egbuonye et al. (32)QN ‡ | Mixed adolescent and adult; Adult women; Mixed adolescent and adult; Female adolescent and adult | |||

| Meal skipping | Onyiriuka et al. (51)QN † | Female adolescent | |||

| Food choice | Onyiriuka et al. (51)QN | Female adolescent | |||

| Dietary patterns | Zeba et al. (53)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Energy intake | Hattingh et al. (39)/Hattingh et al. (40)/Hattingh et al. (41)QN * | Female adult | |||

| Fattening practices | Jafri et al. (42)QN * | Adult women | |||

| Parity (2) | Dietary patterns | Zeba et al. (54)QN * | Mixed adult | ||

| Fruit and vegetable intake | Landais(42)/Landais et al. (45)QN ‡ | Adult women | |||

| Gender (5) | Dietary quality | Soualem et al. (56)QN * | Mixed adolescent | ||

| Dietary diversity | Codjoe et al. (33)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Dietary intake | Aounallah-Skhiri et al. (30)QN * | Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Fast-food intake | Van zyl et al. (58)QN † | Mixed adult | |||

| Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN ‡ | Mixed adult | |||

| Body composition (2) | Dietary intake | Pradeilles(62)MM ‡ | Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN ‡ | Mixed adult | |||

| Pubertal development (1) | Dietary intake | Pradeilles(62)MM | Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| BMI z-score (1) | Dietary intake/Snacking | Feeley et al. (35)QN † | Mixed adolescent | ||

| Fat mass (1) | Dietary intake/Snacking | Feeley et al. (35)QN † | Mixed adolescent | ||

| Health (2) | Food intake | Waswa(59)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Demographic (9) | Income (individual/household) (6) | Dietary diversity | Codjoe et al. (33)QN * and Kiboi et al. (43)QN † | Female adolescent and adult | |

| Dietary intake | Legwegoh et al. (23)/Legwegoh et al. (24)QL and Steyn et al. (57)QN † | Mixed adult; Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Dietary patterns | Zeba et al. (54)QN ‡ | Mixed adult | |||

| Dietary quality | Soualem et al. (56)QN † | Mixed adolescent | |||

| Socio-economic status (individual/household) (13) | Dietary diversity | Becquey et al. (31)QN † and Savy et al. (53)QN * | Mixed adolescent and adult; Female adult | ||

| Dietary intake | Aounallah-Skhiri et al. (30)QN †, Legwegoh et al. (23)/Legwegoh et al. (24)QL, Hattingh et al. (39)/Hattingh et al. (40)/Hattingh et al. (41)QN ‡, Mbochi et al. (48)QN †, Njelekela et al. (50)QN ‡, Pradeilles(62)MM ‡ and Steyn et al. (57)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult; Mixed adult; Female adult; Female adult; Mixed adult; Mixed adolescent and adult; Mixed adolescent and adult; | |||

| Fruit and vegetable intake | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN * | Female adult | |||

| Dietary quality | Fokeena & Jeewon(36)QN * | Mixed adolescent | |||

| Meal skipping /Food choices | Onyiriuka et al. (51)QN * | Female adolescent and adult | |||

| Fast-food intake | Van zyl et al. (58)QN † | Mixed adult | |||

| Employment (individual/parent/household head) (7) | Dietary diversity | Kiboi et al. (43)QN †, Cisse-Egbuonye et al. (32)QN † and Codjoe et al. (33)QN * | Female adolescent and adult; Female adolescent and adult; Mixed adult and adolescent | ||

| Fruit and vegetable intake | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN † | Female adult | |||

| Dietary intake | Aounallah-Skhiri et al. (30)QN † and Steyn et al. (57)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult; Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Dietary quality | Soualem et al. (56)QN † | Mixed adolescent | |||

| Education (individual/parent) (9) | Dietary diversity | Kiboi et al. (43)QN † | Female adolescent and adult | ||

| Dietary intake | Aounallah-Skhiri et al. (30)QN †, Glozah & Pevalin(37)QN † and Lopez et al. (46)QN * | Mixed adolescent and adult; Mixed adolescent and adult; Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Dietary quality | Soualem et al. (56)QN ‡ | Mixed adolescent | |||

| Dietary patterns | Zeba et al. (54)QN ‡ | Mixed adult | |||

| Fruit and vegetable intake | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN and Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN † | Female adult ; Mixed adult | |||

| Household dietary diversity | Codjoe et al. (33)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Wealth (individual/household) (3) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN * | Mixed adult | ||

| Dietary diversity | Codjoe et al. (33)QN † | Mixed adult and adolescent | |||

| Food choice | Agbozo et al. (28)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Land ownership (1) | Dietary diversity | Kiboi et al. (43)QN † | Female adolescent and adult | ||

| Ethnicity (5) | Dietary intake | Steyn et al. (57)QN ‡ | Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| Disordered eating | Gitau et al. (38)QN ‡ | Male adolescent | |||

| Meal skipping/Food choice | Onyiriuka et al. (51)QN * | Female adolescent and adult | |||

| Fruit and vegetable consumption | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN † | Mixed adult | |||

| Dietary diversity | Codjoe et al. (33)QN ‡ | Mixed adult and adolescent | |||

| Household food expenditure (2) | Dietary diversity | Becquey et al. (31)QN † and Codjoe et al. (33)QN ‡ | Mixed adolescent and adult; Mixed adult and adolescent | ||

| Financial insecurity (1) | Unhealthy eating choice | Draper et al. (22)QL | Female adult | ||

| Social environment (11) | Family (9) | Marital status (6) | Fruit and vegetable intake and diversity | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN ‡ and Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN * | Female adult; Mixed adult |

| Fattening practices | Rguibi & Behalsen(25)QL and Jafri et al. (42)QN * | Female adolescent and adult; Adult women | |||

| Dietary diversity | Becquey et al. (31)QN † and Savy et al. (53)QN * | Mixed adolescent and adult; Female adult | |||

| Household social roles (1) | Snacking | Batnitzky(18)QL | Mixed adult | ||

| Household composition (4) | Meal skipping | Onyiriuka et al. (51)QN * | Female adolescent and adult | ||

| Food intake | Batnitzky(18)QL | Mixed adult | |||

| Dietary diversity | Codjoe et al. (33)QN ‡ and Cisse-Egbuonye et al. (32)QN ‡ | Mixed adult and adolescent; Female adolescent and adult | |||

| Eating companions (2) | Meal skipping | Onyiriuka et al. (51)QN * | Female adolescent and adult | ||

| Food choice | Brown et al. (20)QL | Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Shared bowl (1) | Fruit and vegetable intake and diversity | Landais(43)/Landais et al. (45)QN ‡ | Female adult | ||

| What rest of family eat (2) | Food choice | Charlton et al. (61)MM and Boatemma et al. (19)QL | Female adolescent and adult; Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| Number of children (1) | Fruit and vegetable intake and diversity | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Parental influence (1) | Adequacy of food intake | Waswa(59)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Support in the household (3) | Food choice | Boatemma et al. (19)QL, Becquey et al. (31)QN † and Savy et al. (53)QN * | Mixed adolescent and adult; Mixed adolescent and adult; Female adult | ||

| Dietary intake | Glozah & Pevalin(37)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Friends and peers (n 2) | Friendship (4) | Fruit and vegetable consumption | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN * | Mixed adult | |

| Dietary intakes | Sedibe et al. (26) */Voorend et al. (27)QL * | Female adolescent | |||

| Food choice | Boatemma et al. (19)QL | Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Adequacy of food intake | Waswa(59)QN * | Female adult | |||

| Fast-food intake | Van zyl et al. (58)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Religious groups (1) | Dietary intake | Pradeilles(62)MM | Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| Physical environment(12) | Home (4) | Household food stocks (1) | Dietary diversity | Becquey et al. (31)QN †, Kiboi et al. (43)QN † and Codjoe et al. (33)QN ‡ | Mixed adolescent and adult; Female adolescent and adult; Mixed adult and adolescent |

| Food availability (3) | Adequacy of food intake | Waswa(59)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Dietary diversity | Codjoe et al. (33)QN † | Mixed adult and adolescent | |||

| Food choice | Agbozo et al. (28)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Living area (3) | Fruit and vegetable intake/ diversity | Landais(44)/Landais et al. (45)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya(52)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Food choice | Mayen et al. (47)QN † | Mixed adult | |||

| Housing conditions (2) | Dietary intake | Steyn et al. (57)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| Meal skipping | Onyiriuka et al. (51)QN * | Female adolescent and adult | |||

| Neighbourhoods (7) | Household sanitation (1) | Dietary diversity | Becquey et al. (31)QN † and Savy et al. (53)QN * | Mixed adolescent and adult; Female adult | |

| Neighbourhood SES (2) | Dietary intake | Pradeilles(62)MM ‡ | Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| Dietary intake/Snacking | Feeley et al. (35)QN * | Mixed adolescent | |||

| Affordability (2) | Food choice | Boatemma et al. (19)QL and Sedibe et al. (26)/Voorend et al. (27)QL | Mixed adolescent and adult; Female adolescent | ||

| Eating outside of home (2) | Fruit and vegetable consumption | Landais(43)/Landais et al. (45)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Dietary diversity | Codjoe et al. (33)QN † | Mixed adult and adolescent | |||

| Where food is bought (1) | Dietary intake | Steyn et al. (57)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult | ||

| Convenience (2) | Dietary intake | Sedibe et al. (26)QL/Voorend et al. (27)QL | Female adolescent | ||

| Fast-food intake | Van Zyl et al. (58)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Availability (3) | Fast-food intake | Van Zyl et al. (58)QN * | Mixed adult | ||

| Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer et al.(52)QN* | ||||

| Food choices | Boatemma et al. (19)QL | Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| School (2) | School attendance (1) | Dietary habits | Sedibe et al. (26)/Voorend et al. (27) | Female adolescent | |

| Dietary intake | Aounallah-Skhiri et al. (30)QN † | Mixed adolescent and adult | |||

| Macro-level environment(9) | Food marketing and media (3) | Advertising (1) | Dietary intake | Legwegoh et al. (23)/Legwegoh et al. (23)QL | Mixed adults |

| Media (3) | Fast-food intake | Van Zyl et al. (58)QN * | Mixed adult | ||

| Dietary intake/Disordered eating | Amenyah & Michels(29)QN * | Mixed adolescent | |||

| Food intake | Waswa(59)QN * | Female adult | |||

| Ideal body size (2) | Dietary intake/Disordered eating | Amenyah & Michels(29)QN * | Mixed adolescent | ||

| Disordered eating | Gitau et al. (38)QN ‡ | Male adolescent | |||

| Societal and cultural norms/values (2) | Religion (5) | Fruit and vegetable intake | Peltzer et al. (52)QN ‡ | Mixed adult | |

| Skipping meal | Mogre et al. (49)QN * | Mixed adult | |||

| Dietary diversity | Becquey et al. (31)QN †, Savy et al. (53)QN * and Codjoe et al. (33)QN ‡ | Mixed adolescent and adult; Female adult; Mixed adult and adolescent | |||

| Food intake | Waswa(59)QN * | Female adult | |||

| Cultural beliefs (4) | Food intake | Waswa(59)QN * | Female adult | ||

| Fattening practices | Rguibi & Behalsen(25)QL | Female adolescent and adult | |||

| Dietary diversity | Codjoe et al. (33)QN ‡ | Mixed adult and adolescent | |||

| Dietary intake | Legwegoh et al. (23)/Legwegoh et al. (23)QL | Mixed adults | |||

| Food and beverage industry (4) | Food prices (5) | Dietary intake | Legwegoh et al. (23)/Legwegoh et al. (23)QL and Sedibe et al. (26)/Voorend et al. (27)QL | Mixed adults; Female adolescent | |

| Food choice | Charlton et al. (61)MM | Female adolescent and adult | |||

| Food intake | Waswa(59)QN * | Female adult | |||

| Unhealthy eating choice | Draper et al. (22)QL | Female adult | |||

| Quality/freshness of food (1) | Food choice | Charlton et al. (61)QN * | Female adolescent and adult | ||

| Quick/easy to make foods (1) | Food choice | Charlton et al. (61)MM | Female adolescent and adult | ||

| Presentation and packaging (1) | Food choice | Charlton et al. (61)MM | Female adolescent and adult |

MM, mixed methods; QN, quantitative study; QL, qualitative study.

Association not assessed/reported.

Significant association.

Association assessed but NS.

Dietary factors in adult women, adult men and adolescents

Individual level

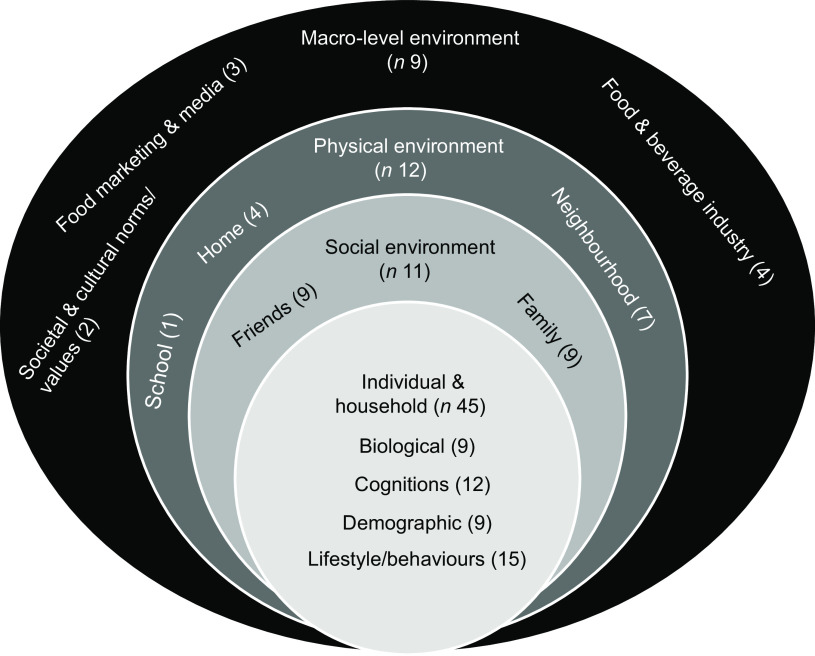

Almost two-thirds of factors identified were on the individual level (45/77), of which twelve related to cognitions, fifteen to lifestyle/behaviours, nine were biological factors and nine were demographic factors (Fig. 2). Factors specific to adolescents included self-esteem, body satisfaction, dieting, spoken language, school attendance, gender, body composition, pubertal development, BMI and fat mass.

Fig. 2.

A summary of factors (n 77) emerging from the included studies at different environmental levels

Cognitions

Taste and hunger were cognition-related factors only found within adult studies(26,27,32,58,61). For instance, one quantitative study(58) in Johannesburg found that 52·5 % of participants believed taste influenced fast-food intake. Higher perceived stress levels were found to significantly decrease the amount of fruit and vegetable consumption in a mixed adult population in Egypt, with a more pronouned effect in men(34). Food knowledge and subjective health status was more commonly reported in the studies of adults(28,46,59). Preferences, mood and perception of diet quality and quantity were reported in both qualitative and quantitative studies of both adolescents and adults(19,26,27,31,59).

A small number of factors emerged on the relationship between body satisfaction and dietary behaviours. An association was identified between decreased self-esteem and body satisfaction with disordered eating in South African adolescents, as measured by the Eating Attitudes Tests 26(38). No significant association was found between body image perception and food intake in a quantitative study of female adults(59).

Lifestyle/behaviours

A third of individual-level factors identified for adults were categorised under the lifestyle/behaviours sub-level. Time limitation was found to be an important factor in five studies encompassing qualitative and quantitative data conducted in Botswana, Cape Verde, Ghana and South Africa(20,21,23,24,49,58). In the qualitative study conducted in Cape Verde( 21), reduced time availability was associated with the intake of unhealthy street foods. Other important lifestyle-related factors identified in a quantitative study related to lack of fruit and vegetable intake(52) were tobacco use, alcohol use, physical inactivity and low quality of life. Spoken language was found to be significantly associated with dietary quality in one quantitative study conducted in Morocco, as adolescents who only spoke Arabic had a poorer quality of diet than those who spoke both Arabic and French(56).

Biological

Evidence from quantitative studies was found for the role of biological factors, which were associated with dietary behaviours in adults, that is, morbidity(43), age(31,39–42,44,45,51,53,56) and having multiple children (parity)(44,45,54). For instance, increased morbidity was significantly associated with minimum dietary diversity among pregnant women in Kenya(43).

More diverse biological factors were investigated for adolescents than for adults. However, only age(51), BMI and fat mass(35) were significantly associated with dietary behaviours. For instance, increasing age was significantly associated with skipping meals among schoolgirls in Nigeria(51) and fat mass was negatively associated with poor eating behaviour(35).

Demographic

More demographic factors were identified in adult women than in mixed adult studies. In one quantitative study of adults conducted in Burkina Faso, males of higher SES, as measured by income and education were significantly aggregated in the ‘urban’ diet cluster, while there were proportionally more lower income, non-educated and female subjects in the ‘traditional’ diet cluster(54). Other factors that were investigated were household composition and family profession, but their relationship with dietary behaviours was NS. Adolescents with high SES adhered to more aspects of dietary guidelines than those of low SES in one quantitative study in Mauritius(36).

Qualitative and quantitative studies have found that the importance of household SES was apparent across a range of SES indicators including household income or wealth(23,24,33,43,50,54,57), employment(32,43,45,56,57), land ownership(43) and financial insecurity(22). Educational level of individuals or parents was also found to play a role in dietary behaviours in several quantitative studies(30,33,37,43–46,52,54,56). Higher parental education level was associated with better dietary intake in four quantitative studies among adolescents(30,33,37,46), resulting in a higher modern dietary diversity score for adolescents in Tunisia,(30) higher household dietary diversity score in Ghana(33) and better healthy eating behaviours in Ghana(37) and Morocco(46) than those whose parents had average or low educational attainment.

Dietary behaviours were associated with ethnicity in South African adults(38,52) and adolescents in South Africa(38) and Nigeria(51).

Social environment

Eleven factors emerged that related to the social environment, eleven studies (both qualitative and quantitative) explored family influences(18–20,25,31,42,44,45,51,53,59,61) and four studies investigated friendship(19,26,27,52,59) (Fig. 2).

Family

The social environment was particularly investigated in adolescent studies; nine factors related to the family including marital status, with evidence coming from both qualitative and quantitative studies(25,31,42,44,53), what the rest of the family eats(19,61) and support in the household(19,31,53).

Friends

Two qualitative studies examined the role of friendship on dietary habits and reported that friendship was associated with dietary habits in South African adolescents(26,27), stating that ‘participants often ate the same food as their friends’ and that shared food consumption between friends was common. In another qualitative study in Ghana, some participants mentioned friends as influencing food choice; foods recommended among peers were usually processed foods such as savoury snacks, soda and instant noodles(19). A quantitative study conducted among South African adults(52) did not find a significant association between social cohesion and fruit and vegetable consumption.

Physical environment

Fourteen studies (qualitative and quantitative) investigated the role of the physical environment on dietary behaviours, of which nine included adolescents(19,26,27,31,33,35,43,51,57,62). Twelve factors emerged in the physical food environment that influenced dietary behaviours. Seven of these were in the neighbourhood, four in the home environment and one in the school environment (Fig. 2).

Convenience and availability of food were the most investigated factors in the physical environment. For instance, convenience was identified as a factor influencing fast-food intake with one quantitative study in South Africa noting that 58·1 % of participants believed it influenced their food choices(58). Significant associations were found between housing conditions and where food is bought with dietary behaviours in South Africa(57). Two studies found an association between eating outside the home and dietary behaviours(33,44,45). Eating outside the home was associated with higher household dietary diversity in a quantitative study in Ghana, while food eaten at home was associated with lower household dietary diversity scores(33).

The influence of school on dietary habits was investigated by only one qualitative study(26), which found that availability of food within schools, as well as sharing food within school, influenced dietary habits in South Africa.

Macro-environment

Nine factors emerged as influencing dietary behaviours that were on the macro-environment level. Three of these factors related to the food marketing and media environment, two related to societal and cultural values and four related to the role of the food and beverage industry.

Food prices were associated with fast-food intake in one South African quantitative study of young adults(58). Media and advertising were found to be associated with dietary intake of adults in both qualitative and quantitative studies in Botswana(23,24) and South Africa(58). About 49 % of participants in one study in South Africa stated that they believed media messages influenced their decision to purchase fast food(58). In a quantitative study conducted in South Africa, ideal body size was related to dietary behaviours(38). A quantitative study conducted in Ghana(29) identified that larger ideal body size was associated with a changed Eating Attitudes Tests 26 score. Lack of religious involvement was associated with dietary behaviour in one quantitative study of adults in South Africa(52), and one quantitative study of adults and adolescents in Ghana but was not associated with meal skipping or food choices in adults(49).

Discussion

This systematic mapping review mapped the factors influencing dietary behaviours of adolescents and adults in African urban food environments and identified areas for future research. Thirty-nine studies (forty-five records) were included in the final data synthesis. In total, seventy-seven factors influencing dietary behaviours were identified, with two-thirds at the individual level (45/77). Factors in the social (11/77), physical (12/77) and macro (9/77) environments were investigated less. The inclusion of two additional population groups (adult men and adolescents), in comparison to the original review, expands the generalisability of findings to the general population in urban Africa. Studies included in this review were from fifteen African countries, encompassing a range of low-, middle- and high-income African countries, reflecting the heterogeneity of urban African contexts. However, over half (22/39) were conducted in Ghana, Morocco or South Africa. This updates and extends a previous review, which was restricted to women(8). The current review updated and extended the demographic scope to include men and adolescents, as well as women.

Findings synthesised from included studies indicate that the most investigated factors for adults and adolescents were the individual and household environment of the socio-ecological model as described by Story et al. (15). This finding is consistent with our previous review(8). Dietary behaviour was significantly associated with a range of individual and household environmental factors: household income, educational level, employment, land ownership, socio-economic status (SES), ethnicity and financial insecurity. Low self-esteem, high levels of stress and lack of time were associated with unhealthy dietary behaviours. The focus on individual-level factors might be attributable to the fact that promoting healthy eating and preventing obesity have predominantly focused on changing behaviour through interventions such as nutrition education, although such interventions alone have met with little success(63).

Studies involving adolescents investigated factors in their social environments and were less focused on the role of the physical food environment on dietary behaviours, than for adults. This bias is unsurprising given that adolescence is defined as a transient formative period where many life patterns are learnt(64), particularly through the social environment. Shared food consumption between adolescent friends was common. Evidence from the wider literature outlines the social transmission of eating behaviours, whereby a strong relationship exists between the social environment and amount or types of food eaten(65). This implies individuals tend to eat according to the usual social group they find themselves, either in terms of quantity or types of food eaten(66). Thus, understanding the role of the social environment among adults and adolescents as a modifiable factor influencing dietary behaviours offers an opportunity for developing nutrition interventions that harness social relationships.

Convenience and availability of food were the most investigated factors in the physical environment. Significant associations were found between housing conditions and dietary intake, and where food was purchased and dietary intake. In contrast to the socio-ecological model(15), our map lacks evidence for the role of several factors in the physical environment such as workplaces, schools (one study), supermarkets and convenience stores.

In contrast to studies conducted in high-income countries, factors influencing dietary behaviours in the macro-environment were rarely investigated in our review for adults or adolescents. Only food/drink advertising and religion (adolescents only) and food prices were associated with unhealthy dietary behaviours, but many macro-level factors are known to influence diet, such as the political context, economic systems, health care systems and behavioural regulations(67) that were not studied. One possible explanation may be that because Story’s model was generated following research within high-income counties, some of the sub-levels may be less relevant to the African context. Factors that have been shown to influence dietary behaviours in high-income countries and were investigated in studies included in this review include food prices, social networks (friendship), time constraints and convenience. However, in high-income countries these factors are often reported in low-income groups(68). Another important finding from this review is the consistent association between SES and dietary behaviours as expected. SES is a global concern, and several studies have shown that lower SES restricts food choices, thus compelling the consumption of unhealthy foods(69–71).

Of the thirty-nine studies identified, none specifically investigated adult men, as they were only included in mixed adult population studies. Adult men and women studies identified during this review showed similar types of factors associated with dietary behaviour across the different environments, suggesting that similar interventions could be targeted at both men and women. However, demographic factors were identified more in adult women than in mixed adult studies. This implies that the household is an important setting in which to reach women. The findings for women from this review went beyond that of the previous review. Three more factors (stress, self-esteem and body satisfaction) were identified in the updated review. Furthermore, the expanded review identified evidence of more physical-level dietary factors including housing, living area, convenience and where food is bought.

As the most common study methodology of included studies was cross-sectional, it is not possible to conclude on causality of the factors in different components of the food environment on dietary behaviours. Limitations regarding the use of the socio-ecological model(68) became evident during the review, as there is overlap between the different environmental levels for factors such as SES, spoken language and religious group. For instance, SES crosses multiple levels of the model, particularly in adolescents, as SES is often measured via physical or household/family-related factors. Another example is religious groups, which do not fit within the current sub-categories defined by Story’s ecological model(15). Although religion may broadly be classified as a factor in the macro-environment, religious groups may best fit in the social environment. While the socio-ecological model depicts reality as artificially separating individual and social experiences(68), it is still a useful tool to communicate with policy makers and practitioners, unlike systems-based approaches, which are better at representing reality but rely on data on causality and mechanisms that are often lacking in cross-sectional and quantitative studies(72) and are harder to communicate to a non-expert audience.

This review revealed considerable heterogeneity in the design of quantitative studies and the outcome measures used for assessing dietary behaviours. Future quantitative studies should ensure that outcome measures are clearly defined and report the direction of association between the factors examined and whether dietary behaviours are healthy or unhealthy. Quantitative studies should enhance the control of confounding variables to prevent them from introducing bias into the findings, and longitudinal quantitative studies are needed to be able to measure how factors influencing dietary behaviours are changing with the transformation of food environments. Qualitative studies are useful for understanding the complex relationships between determinants of dietary behaviours. Qualitative studies need to have a rigorous design and improve the reporting of reflexivity by considering the impact of the role of researcher characteristics on the data collected to improve their quality.

This review highlights the need for robust mixed methods studies to gain a better understanding of the drivers of dietary behaviours in urban food environments in Africa.

This is the first systematic mapping review that focuses on environmental factors of dietary behaviour for all population groups in an urban African context. The nutrition transition has been associated with changes in dietary patterns globally with concomitant increases in obesity and NR-NCD, now among the leading causes of death(73). In African countries, NR-NCD risk is increasing at a faster rate and at a lower economic threshold than seen in high-income countries(74), hence the need for this review that identifies context specific factors that influence dietary behaviours. The recent focus on good health and well-being as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG3)( 75) also reflects this review’s aim to identify the underlying determinants of dietary behaviour in the urban African context to identify avenues for interventions.

Conclusion

The relatively small number of appropriate studies identified, following an extensive literature search, indicates a significant gap in research into understanding of the factors influencing diets in food environments in urban Africa. Due to the increasing presence of multiple burdens of malnutrition in urban Africa, secondary to the nutrition transition(6), more studies should be directed at investigating how food environments are changing and driving this complex nutritional landscape. In particular, future research could emphasise the investigation of adult men and adolescents. The evidence from this review will contribute towards developing a socio-ecological framework of factors influencing dietary behaviours adapted to urban African food environments.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Emmanuel Cohen was supported by the South African DST/NRF Centre of Excellence in Human development. Financial support: This research was funded by a Global Challenges Research Fund Foundation Award led by the MRC, and supported by AHRC, BBSRC, ESRC and NERC, with the aim of improving the health and prosperity of low- and middle-income countries. The TACLED (Transitions in African Cities Leveraging Evidence for Diet-related non-communicable diseases) project code is MR/P025153/1. The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: All authors designed the review. A.M. conducted the searches and screening. H.O.-K. checked 10 % of excluded records at title/abstract and full-text screening stages. A.M., F.G. and H.O.-K. extracted data and conducted analyses and quality assessment. M.W. checked data extraction and quality assessment. H.O.-K. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed draft versions of the manuscript and provided suggestions and critical feedback. All authors have made a significant contribution to this manuscript and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019005305.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Holdsworth M & Landais E (2019) Urban food environments in Africa: implications for policy and research. Proc Nutr Soc 78, 513–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Popkin BM & Gordon-Larsen P (2006) The nutrition transition: worldwide obesity dynamics and their determinants. Int J Obes 28, S2–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holmes MD, Dalal S, Sewram V et al. (2018) Consumption of processed food dietary patterns in four African populations. Public Health Nutr 21, 1529–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Imamura F, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S et al. (2015) Dietary quality among men and women in 187 countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic assessment. Lancet Glob Heal 3, e132–e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS et al. (2008) Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes 32, 1431–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Popkin BM (2004) The nutrition transition: an overview of world patterns of change. Nutr Rev 62, S140–S143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Onis M, Blössner M & Borghi E (2010) Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children. Am J Clin Nutr 92, 1257–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gissing SC, Pradeilles R, Osei-Kwasi HA et al. (2017) Drivers of dietary behaviours in women living in urban Africa: a systematic mapping review. Public Health Nutr 20, 2104–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grant MJ & Booth A (2009) A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Heal Info Libr J 26, 91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cooke A, Smith D & Booth A (2012) Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res 22, 1435–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olshansky SJ & Ault AB (1986) The fourth stage of the epidemiologic transition: the age of delayed degenerative diseases. Milbank Q 64, 355–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cooper C, Booth A, Britten N et al. (2017) A comparison of results of empirical studies of supplementary search techniques and recommendations in review methodology handbooks: a methodological review. Syst Rev 6, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS et al. (2004) Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research from a variety of fields. Alberta Herit Found Med Res AHFMR HTA Initiat 13, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Booth A, Sutton A & Papaioannou D (2016) Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review. London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O’Brien R et al. (2008) Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health 29, 253–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Br Med J 339, b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Data.worldbank.org (2019) Low & middle income | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/income-level/low-and-middle-income (accessed November 2018).

- 18. Batnitzky A (2008) Obesity and household roles: gender and social class in Morocco. Sociol Heal Illn 30, 445–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boatemaa S, Badasu DM & De-Graft Aikins A (2018) Food beliefs and practices in urban poor communities in Accra: implications for health interventions. BMC Public Health 18, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brown C, Shaibu S, Maruapula S et al. (2015) Perceptions and attitudes towards food choice in adolescents in Gaborone, Botswana. Appetite 95, 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Craveiro I, Alves D, Amado M et al. (2016) Determinants, health problems, and food insecurity in urban areas of the largest city in Cape Verde. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13, 1155–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Draper CE, Davidowitz KJ & Goedecke JH (2015) Perceptions relating to body size, weight loss and weight-loss interventions in black South African women: a qualitative study. Public Health Nutr 19, 548–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Legwegoh AF (2012) Urban food security in Gaborone, Botswana, p. 130. PhD Thesis, University of Guelph.

- 24. Legwegoh AF & Hovorka AJ (2016) Exploring food choices within the context of nutritional security in Gaborone, Botswana. Singap J Trop Geogr 37, 76–93. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rguibi M & Belahsen R (2006) Fattening practices among Moroccan Saharawi women. East Mediterr Heal J 12, 619–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sedibe MH, Feeley AB, Voorend C et al. (2014) Narratives of urban female adolescents in South Africa: dietary and physical activity practices in an obesogenic environment. South Afr J Clin Nutr 27, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Voorend CGN, Norris SA, Griffiths PL et al. (2013) ‘We eat together; Today she buys, tomorrow I will buy the food’: adolescent best friends’ food choices and dietary practices in Soweto, South Africa. Public Health Nutr 16, 559–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Agbozo F, Amardi-Mfoafo J, Dwase H et al. (2018) Nutrition knowledge, dietary patterns and anthropometric indices of older persons in four peri-urban communities in Ga West municipality, Ghana. Afr Health Sci 18, 743–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Amenyah SD & Michels N (2016) Role of diet, physical activity and media in body size and dissatisfaction in Ghanaian adolescents. Ann Nutr Metab 67, 402. http://linker2.worldcat.org/?rft.institution_id=132347&spage=402&pkgName=customer.131416.13&issn=0250-6807&linkclass=to_article&jKey=1421-9697&provider=karger&date=2015-10&aulast=Amenyah+S.D.%3B+Michels+N.&atitle=Role+of+diet%2C+physical+activity+and+medi (accessed November 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aounallah-Skhiri H, Trasissac P, El-Ati JA et al. (2011) Nutrition transition among adolescents of a south-Mediterranean country: dietary patterns, association with socio-economic factors, overweight and blood pressure. A cross-sectional study in Tunisia. Nutr J 10, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Becquey E, Savy M, Danel P et al. (2010) Dietary patterns of adults living in Ouagadougou and their association with overweight. Nutr J 9, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cisse-Egbuonye N, Ishdorj A, McKyer ELJ et al. (2017) Examining nutritional adequacy and dietary diversity among women in Niger. Matern Child Health J 21, 1408–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Codjoe SNA, Okutu D & Abu M (2016) Urban household characteristics and dietary diversity. Food Nutr Bull 37, 202–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. El Ansari W & Berg-Beckhoff G (2015) Nutritional correlates of perceived stress among university students in Egypt. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12, 14164–14176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Feeley AB, Musenge E, Pettifor JM et al. (2013) Investigation into longitudinal dietary behaviours and household socio-economic indicators and their association with BMI Z-score and fat mass in South African adolescents: the Birth to Twenty (Bt20) cohort. Public Health Nutr 16, 693–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fokeena WB & Jeewon R (2012) Is there an association between socioeconomic status and body mass index among adolescents in Mauritius? Sci World J 2012, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Glozah FN & Pevalin DJ (2015) Perceived social support and parental education as determinants of adolescents’ physical activity and eating behaviour: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Adolesc Med Health 27, 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gitau TM, Micklesfield LK, Pettifor JM et al. (2014) Eating attitudes, body image satisfaction and self-esteem of South African Black and White male adolescents and their perception of female body silhouettes. J Child Adolesc Ment Health 26, 193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hattingh Z, Walsh CM, Veldman FJ et al. (2006) Macronutrient intake of HIV-seropositive women in Mangaung, South Africa. Nutr Res 26, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hattingh Z, Walsh C & Bester CJ (2011) Anthropometric profile of HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected women aged 25–44 years in Mangaung, Free State. South Afr Fam Pract 53, 474–480. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hattingh Z, Le Roux M, Nel M et al. (2014) Assessment of the physical activity, body mass index and energy intake of HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected women in Mangaung, Free State province. South Afr Fam Pract 56, 196–200. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jafri A, Jabari M & Dahhak M (2013) Obesity and its related factors among women from popular neighborhoods in Casablanca, Morocco. Ethn Dis 23, 369–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kiboi W, Kimiywe J & Chege P (2017) Determinants of dietary diversity among pregnant women in Laikipia County, Kenya: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Landais E (2012) Fruit and vegetable consumption and its determinants amongst Moroccan women in the context of nutrition transition. PhD Thesis, University of Nottingham.

- 45. Landais E, Bour A, Gartner A et al. (2014) Socio-economic and behavioural determinants of fruit and vegetable intake in Moroccan women. Public Health Nutr 18, 809–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. López PM, Anzid K, Cherkaoui M et al. (2012) Nutritional status of adolescents in the context of the Moroccan nutritional transition: the role of parental education. J Biosoc Sci 44, 481–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mayén AL, Bovet P, Marti-Soler H et al. (2016) Socioeconomic differences in dietary patterns in an East African country: evidence from the Republic of Seychelles. PLoS One 11, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mbochi RW, Kuria E, Kimiywe J et al. (2012) Predictors of overweight and obesity in adult women in Nairobi Province, Kenya. BMC Public Health 12, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mogre V, Atibilla J & Kandoh B (2013) Association between breakfast skipping and adiposity status among civil servants in the Tamale metropolis. J Biomed Sci 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Njelekela MA, Liu E, Mpembeni R et al. (2011) Socio-economic status, urbanization, and cardiometabolic risk factors among middle-aged adults in Tanzania. East Afr J Public Health 8, 216–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Onyiriuka AN, Umoru DD & Ibeawuchi AN (2013) Weight status and eating habits of adolescent Nigerian urban secondary school girls. South Afr J Child Heal 7, 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Peltzer K & Phaswana-Mafuya N (2012) Fruit and vegetable intake and associated factors in older adults in South Africa. Glob Health Action 5, e18668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Savy M, Martin-Prével Y, Danel P et al. (2008) Are dietary diversity scores related to the socio-economic and anthropometric status of women living in an urban area in Burkina Faso? Public Health Nutr 11, 132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sodjinou R, Agueh V & Fayomi B (2008) Obesity and cardio-metabolic risk factors in urban adults of Benin: relationship with socio-economic status, urbanisation, and lifestyle patterns. BMC Public Health 8, 84–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sodjinou R, Agueh V, Fayomi B et al. (2009) Dietary patterns of urban adults in Benin: relationship with overall diet quality and socio-demographic characteristics. Eur J Clin Nutr 63, 222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Soualem A, Ahami AOT, Aboussaleh Y et al. (2012) Eating behavior of young adolescents in urban area in northwestern Morocco. Med J Nutr Metab 5, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Steyn NP, Labadarios D & Nel JH (2011) Factors which influence the consumption of street foods and fast foods in South Africa: a national survey. Nutr J 10, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Van Zyl M, Steyn N & Marais M (2010) Characteristics and factors influencing fast food intake of young adult consumers in Johannesburg, South Africa. South Afr J Clin Nutr 23, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Waswa J (2011) Influence of perceived body image on nutrient intake and nutritional health of female students of Moi University. East Afr J Public Heal 8, 132–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zeba AN, Delisle HF & Renier G (2014) Dietary patterns and physical inactivity, two contributing factors to the double burden of malnutrition among adults in Burkina Faso, West Africa. J Nutr Sci 3, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Charlton K, Brewitt P & Bourne L (2004) Sources and credibility of nutrition information among black urban South African women, with a focus on messages related to obesity. Public Health Nutr 7, 801–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pradeilles R (2015) Neighbourhood and household socio-economic influences on diet and anthropometric status in urban South African adolescents. PhD Thesis, Loughborough University. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63. Delormier T, Frohlich K & Potvin L (2009) Food and eating as social practice-understanding eating patterns as social phenomena and implications for public health. Sociol Heal Illn 31, 215–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rees J & Christine M (1989) Nutritional influences on physical growth and behavior in adolescence. In Biology of Adolescent Behavior and Development, pp. 195–222 [Adams G, editor]. California: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Robinson E, Thomas J & Aveyard P (2014) What everyone else is eating: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of informational eating norms on eating behavior. J Acad Nutr Diet 114, 414–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Powell K, Wilcox J & Clonan A (2015) The role of social networks in the development of overweight and obesity among adults: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 15, 996–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sleddens E, Kroeze W & Kohl L (2015) Correlates of dietary behavior in adults: an umbrella review. Nutr Rev 73, 477–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Osei-Kwasi H, Nicolaou M & Powell K (2016) Systematic mapping review of the factors influencing dietary behaviour in ethnic minority groups living in Europe: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 13, 85–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Powell LM, Zhao Z & Wang Y (2009) Food prices and fruit and vegetable consumption among young American adults. Health Place 15, 1064–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Roberts K, Cavill N, Hancock C et al. (2013) Social and Economic Inequalities in Diet and Physical Activity. London: Public Health England. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Vogel C, Ntani G, Inskip H et al. (2016) Education and the relationship between supermarket environment and diet. Am J Prev Med 51, e27–e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Holdsworth M, Nicolaou M & Langoien L (2017) Developing a systems-based framework of the factors influencing dietary and physical activity behaviours in ethnic minority populations living in Europe: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 14, 154–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2019) Global Burden of Disease (GBD). http://www.healthdata.org/gbd (accessed October 2019).

- 74. Popkin BM (2002) Part II. What is unique about the experience in lower- and middle-income less-industrialised countries compared with the very-high-income industrialised countries? Public Health Nutr 5, 205–214.12027286 [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sustainabledevelopment.un.org (2019) Goal 3 Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3 (accessed October 2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019005305.

click here to view supplementary material