With great interest we read the recently published report by Poppelaars et al. in which no excess mortality was observed in 155 rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients from the COBRA-trial, who received early intensive treatment, compared to the general population (Standardized mortality rate (SMR) 0.80 (0.59-1.06)).[1] The question whether mortality in RA has normalized is debated, as contradicting results have been published.[2–8] In many of the studies on mortality two important factors are not sufficiently taken into account: follow-up duration and disease subtypes. This might explain the conflicting results. Because thus far none of the reported studies incorporated both factors in the analyses, it is too soon to conclude that mortality is “normal” again, as we will show here.

We compliment the authors on emphasizing the importance of a long follow-up duration by showing in their meta-analysis that excess mortality in RA becomes fully apparent after >10 years. This implies that previous studies that reported on normalization of mortality had insufficient follow-up to reach this conclusion.[2–5] Some studies with a short follow-up duration even showed a seemingly decreased mortality in RA, which may be due to a healthy inclusion bias.[3–5]

RA consists of two subtypes that are characterized by the presence or absence of RA-related autoantibodies, of which the presence of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) is most specific for RA. Both subtypes have known differences in the severity of the disease course. The study of Poppelaars et al did not stratify for ACPA, which is due to a small sample size (n=155), leaving the question unanswered if mortality has normalized in both subsets of RA.

To assess the true impact of early intensive treatment on mortality, we performed a large study with up to 25 years of follow-up and sufficient power to stratify for ACPA. 1288 RA-patients fulfilling the 1987 criteria, who were consecutively included in the Leiden Early Arthritis Clinic, were studied. According to treatment in routine care, patients included between 1993-2000 received initial treatment with only NSAIDs or mild DMARDs (e.g. penicillamine, gold, hydroxychloroquine). Patients included between 2001-2016 were treated with early intensive treatment with methotrexate as first-line treatment. Treat-to-target became routine during this period as well. Mortality data were obtained from the civic registries on June 1, 2018. Mortality was compared to the general population in the Netherlands with SMRs adjusted for birth year, gender and calendar year. SMRs were determined for both treatment-strategies, after stratification for follow-up duration (0-5 years, 5-10 years, >10 years) and disease subset (ACPA-status).

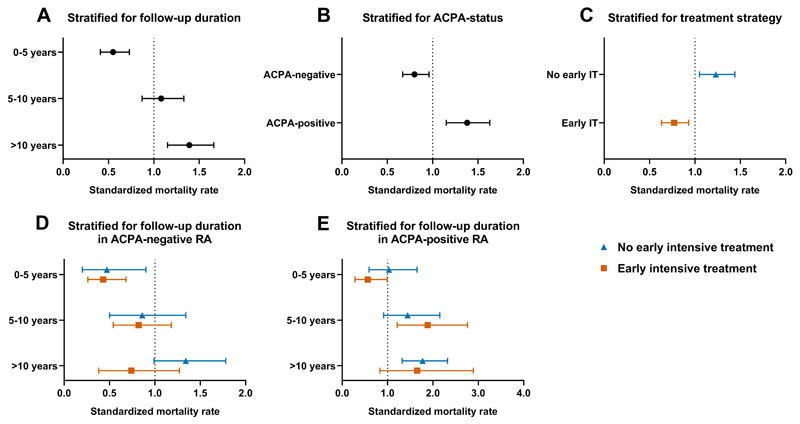

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. 248 patients died during follow-up. SMRs increased during follow-up and excess mortality became evident after 10 years of disease (0-5 years SMR 0.55 (0.41-0.73); 5-10 years 1.08 (0.87-1.33) and >10 years 1.39 (1.15-1.66); Figure 1A). Stratification for disease subset revealed that a decreased mortality was observed within ACPA-negative RA (SMR 0.80 (0.67-0.96)) and an increased mortality within ACPA-positivity RA (SMR 1.38 (1.15-1.63); Figure 1B). Comparing the two treatment strategies without considering follow-up duration and ACPA-status revealed that early intensive treatment was associated with a decrease in mortality compared to the general population (SMR 0.77 (0.63-0.93)), in contrast to group without early intensive treatment (SMR 1.23 (1.05-1.44); Figure 1C). This is concordance with the findings from Poppelaars et al. Subsequent stratification for follow-up duration and ACPA-status showed that excess mortality became apparent after 10 years of disease in ACPA-negative RA without early intensive treatment and that early intensive treatment had normalized this excess mortality. In ACPA-positive RA, in contrast, excess mortality emerged after 5 years of follow-up and was not influenced by early intensive treatment.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of RA patients treated without and with early intensive treatment.

| No early intensive treatment (n = 353) |

Early intensive treatment (n = 945) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion period | 1993-2000 | 2001-2016 |

| Women, n (%) | 238 (67) | 620 (66) |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 56 (16) | 58 (15) |

| Symptom duration, days median (IQR) | 136 (75-279) | 117 (58-234) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 98 (30) | 211 (25) |

| ESR, median (IQR) | 37 (21-58) | 29 (14-45) |

| 66-SJC, median (IQR) | 10 (5-16) | 6 (3-11) |

| RF-positive, n (%) | 193 (55) | 543 (59) |

| ACPA-positive, n (%) | 199 (56) | 456 (51) |

N, number of patients; SD, standard deviation; IQR, inter quartile range; ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; SJC, swollen joint count; RF, rheumatoid factor; ACPA, anti-citrullinated peptide antibody;

Figure 1.

Mortality of patients with RA compared to the general population, stratified for follow-up duration (A), disease subset characterized by ACPA-status (B), early intensive treatment (IT) (C) and these variables combined (D&E), showing that excess mortality has normalized by early intensive treatment in ACPA-negative RA but not in ACPA-positive RA.

In conclusion, sufficient follow-up duration and stratification for relevant disease subsets are important to disentangle the effects of treatment on mortality. Our data from a large cohort of RA patients with up to 25 years follow-up showed that excess mortality has resolved since the introduction of early intensive treatment in ACPA-negative RA, but excess mortality remains an issue in ACPA-positive RA. This underlines that RA consists of two types with differences in treatment response and long-term outcome and that additional efforts are still needed to reduce the increased risk of early death in ACPA-positive RA.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding: The research leading to these results has received funding from the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Starting grant, agreement No 714312). The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Contributorship: XMEM and AHMvdHvM contributed to the conception and study design. XMEM analysed the data. XMEM, TWJH, EN and AHMvdHvM contributed to interpretation of the data. XMEM and EN contributed to acquisition of the data. XMEM and AHMvdHvM wrote the first version of the manuscript and TWJH revised it critically. All authors read and approved the final version of the document.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethical approval: ’Commissie Medische Ethiek' of the Leiden University Medical Centre (B19.008).

Data sharing statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Poppelaars PB, van Tuyl LHD, Boers M. Normal mortality of the COBRA early rheumatoid arthritis trial cohort after 23 years of follow-up. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2019 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markusse IM, Akdemir G, Dirven L, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, van Groenendael JH, Han KH, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Patients With Recent-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis After 10 Years of Tight Controlled Treatment: A Randomized Trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2016;164(8):523–31. doi: 10.7326/M15-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Nies JA, de Jong Z, van der Helm-van Mil AH, Knevel R, Le Cessie S, Huizinga TW. Improved treatment strategies reduce the increased mortality risk in early RA patients. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2010;49(11):2210–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puolakka K, Kautiainen H, Pohjolainen T, Virta L. No increased mortality in incident cases of rheumatoid arthritis during the new millennium. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2010;69(11):2057–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.125492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindqvist E, Eberhardt K. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis patients with disease onset in the 1980s. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 1999;58(1):11–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmqvist M, Ljung L, Askling J. Mortality following new-onset Rheumatoid Arthritis: has modern Rheumatology had an impact? Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2018;77(1):85–91. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gwinnutt JM, Symmons DPM, MacGregor AJ, Chipping JR, Marshall T, Lunt M, et al. Twenty-Year Outcome and Association Between Early Treatment and Mortality and Disability in an Inception Cohort of Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: Results From the Norfolk Arthritis Register. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, NJ) 2017;69(8):1566–75. doi: 10.1002/art.40090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abhishek A, Nakafero G, Kuo CF, Mallen C, Zhang W, Grainge MJ, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and excess mortality: down but not out. A primary care cohort study using data from Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2018;57(6):977–81. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]