Abstract

Flowers have a species-specific functional life span that determines the time window in which pollination, fertilization, and seed set can occur. The stigma tissue plays a key role in flower receptivity serving to intercept pollen and initiate pollen tube growth towards the ovary. Here we show that a tightly controlled and developmentally induced programmed cell death process terminates the functional life span of the stigmatic cells in Arabidopsis thaliana. We identified the leaf senescence regulator ORESARA1/ANAC092 and the previously uncharacterized KIRA1/ANAC074 as partially redundant key transcription factors that regulate stigma life span by directly controlling the expression of PCD-associated genes. KIRA1 expression is sufficient to induce programmed cell death and effectively terminate floral receptivity, while lack of both KIRA1 and ORESARA1 substantially increases stigma life span. Surprisingly, however, the extension of stigma life span is accompanied by only a moderate extension of flower receptivity, suggesting that additional processes than stigma PCD participate in the control of the flower’s receptive life span.

Introduction

Flowers are short-lived plant organs that facilitate sexual reproduction in angiosperms. Floral life span is restricted by pollination-induced floral organ senescence, which is triggered concomitant with the onset of seed and fruit development in many species 1. Evidence suggests that hormonal signaling conveys the message that floral organs have become obsolete and can be disposed of after successful initiation of seed development2. However, also in the absence of pollination floral organs start senescing after a certain, species-specific time span, which can range from mere hours to several weeks. The time between flower opening and onset of unpollinated flower senescence has been termed effective pollination period (EPP)3, conveying the concept that the reproductive potential of a flower is irrevocably lost once flower senescence sets in.

Depending on the ecology and the life style of a plant species, there are thought to be selective advantages to modulate the EPP in order to maximize reproductive success. Species with few flowers, low population density, or scarce pollinators might increase their chances for pollination by extending the EPP. In contrast, species with abundant flowers or high chances for rapid pollination would benefit from a shorter EPP by cutting the costs for maintaining unpollinated flowers4.

The enormous plasticity of the EPP among plant species suggests an active control of this trait. Over the past two decades, flower senescence research, using mainly petals as a model system, has revealed important insights into the physiology and the molecular regulation of this process1,5,6. Phytohormones, including abscisic acid and cytokinin, have been shown to influence petal life span via a complex cross-talk with ethylene1. Downstream of phytohormone signaling, only partially understood transcriptional networks control the reprogramming of senescent floral tissues7. Among several transcription factor (TF) families, NAC (Non-Apical Meristem – NAM; Arabidopsis Transcription Activation Factor 1- and 2 – ATAF1, 2; Cup-shaped Cotyledon 2 – CUC2) family members represent the largest group of TFs commonly upregulated in different floral organs in Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis)8. Some NAC TFs occupy prominent positions in their regulatory networks: In Japanese morning glory (Ipomoea nil), suppression of the EPHEMERAL1 resulted in delayed petal senescence9. Interestingly, the closely related ORESARA1 (ORE1/ANAC092) is a NAC TF that is commonly upregulated in senescing Arabidopsis leaves, petals, and siliques8. In Arabidopsis, ORE1 promotes leaf senescence as part of a regulatory network downstream of ethylene signaling10,11. Similarly, the petunia homeodomain–leucine zipper (HD-Zip) TF gene PhHD-Zip is necessary for timely flower senescence both in unpollinated and pollinated flowers12. In contrast, the MADS box transcriptional repressor FOREVER YOUNG FLOWER (FYF) is highly expressed in young flowers prior to pollination, but downregulated after pollination. Constitutive overexpression causes delay of stamen, petal, and sepal senescence after pollination13. These results illustrate that transcriptional reprogramming by TFs is an important aspect of floral senescence. Accordingly, genome-wide transcriptome profiling studies have revealed that flower senescence in different species is associated with the differential expression of many genes5. These genes are likely functional in a range of processes from nutrient mobilization to the regulation of senescence-induced programmed cell death (PCD). Even though the terms ‘senescence’ and ‘PCD’ have been used interchangeably in flower biology1, PCD can be regarded as the end point of the senescence process14. Here, we use PCD as an umbrella term describing pathways organizing the actively controlled cessation of a cell’s vital functions15. In plants, diverse forms of PCD can occur both as a response to biotic and abiotic environmental stresses (ePCD), and in the course of regular development (dPCD)16. While ePCD processes are important for a plant’s adaptation to environmental stress, the tight regulation of dPCD is indispensable for plant growth and successful sexual reproduction17. Interestingly, the transcriptional regulation of ePCD and dPCD seems to be largely independent. Central dPCD-associated genes including BIFUNCTIONAL NUCLEASE1 (BFN1), PUTATIVE ASPARTIC PROTEASE A3 (PASPA3), RIBONUCLEASE3 (RNS3), CYSTEIN ENDOPEPDITASE 1 (CEP1), DUF 679 MEMBRANE PROTEIN4 (DMP4), and EXITUS1 (EXI1) are commonly upregulated in diverse dPCD processes, but most of them are not differentially regulated during the hypersensitive response18. Nevertheless, some senescence-associated genes are commonly upregulated in cases of dPCD and some ePCD processes18,19. Some of these genes have been shown to be directly regulated by key senescence regulators, BFN1 for instance is directly controlled by ORE1 in senescing leaves20.

Here, we investigated the molecular mechanism regulating the EPP in unpollinated flowers of the model plant Arabidopsis. As the floral stigma is the primary interface for pollen reception and represents a key determinant of floral receptivity, we focused our investigations on this organ. Similar to other Brassicaceae species, Arabidopsis has a dry stigma, consisting of over two hundred protruding papilla cells21. The elongated unicellular papillae facilitate pollen capture, recognition, hydration, germination, and the initial guidance of the pollen tube towards the ovary22. We show that the Arabidopsis stigma has a tightly regulated functional life span that is terminated by a rapidly executed canonical dPCD process. When investigating the transcriptional reprogramming during stigma senescence, we identified TFs that are co-regulated with dPCD-associated genes. Manipulation of these TFs is both necessary and sufficient to promote the PCD of Arabidopsis stigmata. Intriguingly, despite the substantial extension of stigma life span in TF mutant flowers, their ability to facilitate seed set was only moderately prolonged, which suggests that besides stigma degeneration additional processes are involved in the control of the EPP.

Results

Arabidopsis stigmatic papilla cells have a limited functional life span

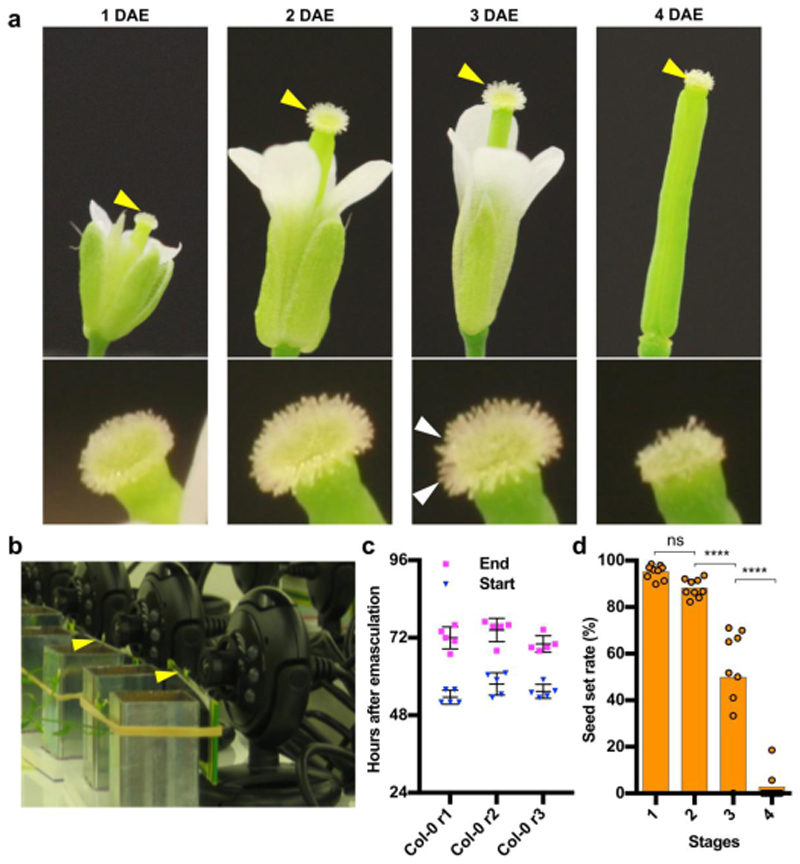

To investigate the functional life span of unpollinated Arabidopsis flowers, we removed the anthers of wild-type (WT) Col-0 flowers at late stage 12c, just prior to pollen release (anthesis)23. Next, we imaged the macroscopic stigma appearance over time. Under long-day growth conditions, we defined four morphological stages of stigma development and senescence (Fig 1a). At stage 1, or 1 day after emasculation (1 DAE) of a 12c flower, the stigmatic papilla cells were not yet completely elongated. At stage 2 (2 DAE) the papilla cells were fully elongated, effectively increasing the stigma surface area. Around 3 DAE, stage 3 marked the onset of age-induced stigma degeneration. Papilla cells started to bend, indicating a loss in turgor pressure, and collapse of individual or groups of papilla cells occurred, thus leading to a ragged appearance of the stigma surface (Fig 1a). The collapse of the remaining papilla cells continued for several hours, resulting in a visually degenerated stigma surface at stage 4 (approximately 4 DAE; Fig 1a).

Figure 1. Stigma degeneration is a developmentally timed process correlated with loss of floral receptivity.

a) Four stages of flower senescence after emasculation of plants grown in long-day conditions. At stage 1, or 1 day after emasculation (1 DAE), papilla cells are still short, whereas they are fully elongated at stage 2 (2 DAE). At stage 3 (3 DAE), the first papilla cells start to bend and collapse, and at stage 4 (4 DAE), stigma collapse is complete. The upper row shows the stigma, which are indicated with yellow arrowheads and given in detail in the lower row, with white arrows indicating the first groups of collapsing papilla cells. b) Webcam-based phenotyping platform. Arrowheads point at mounted flowers. c) Quantitative analysis of three independent webcam experiments conducted under continuous light, showing the reproducibility of occurrence of stage 3 (start) and stage 4 (end) of stigma senescence. Three individual replicates are shown; n = 5 flowers per replicate. Col0-r1: mean±SD=53.6±2.2h (beginning of collapse)/ mean±SD=72.00±3.39 h (end of collapse); Col0- r2: mean±SD=57.7±3.5h (beginning of collapse)/ mean±SD= 74.40±3.63 h (end of collapse); Col0-r3: mean±SD=55.4±2.2h (beginning of collapse)/ mean±SD=70.1±2.56 h (end of collapse). d) Stigma senescence is correlated with loss of reproductive potential. Whereas pollination at stage 1 and 2 results in full seed set, pollination at stages 3 and 4 shows a strong reduction in seed set. Data from three biological replicates are shown; n = 9 flowers per replicate (mean±SEM=95.16±3.01%, 88.08±3.94%, 49.89±22.94%, 2.70±6.25% for stage 1, stage 2, stage 3 and stage 4, respectively). Statistical differences were calculated using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons by Fisher’s LSD test; ns = non-significant.

Using a single-lens reflex camera equipped with a macro lens, we imaged the succession of the stages 1 to 4 under continuous light, observing that the senescence of petals and sepals occurred concomitantly with stigma collapse (Movie M1). In order to quantitatively phenotype stigma senescence, we devised a webcam-based phenotyping system, which allowed us to image up to 20 emasculated flowers simultaneously in a cost-effective manner (Fig 1b). This system delivered 10- minute time-lapse videos of sufficient quality to determine onset and completion of stigma collapse (MovieM2). In the continuous light necessary for non-intermittent monitoring, we observed a faster succession of sigma senescence stages than seen in long-day conditions. The onset of stigma degeneration was recorded around 56 hours after emasculation (HAE) of a 12c flower, on average about 16 hours earlier than in long-day conditions, and stigma collapse was completed at 72HAE (Fig 1c). Some slight, but not statistically significant deviations were observed between independently set up assays (Fig 1c). Hence, for all subsequent webcam phenotyping experiments, we simultaneously imaged mutant and WT flowers in order to correct for potential environmental variation.

Viable papilla cells are necessary for efficient seed set

To investigate to what extent stigma degeneration was correlated with loss of flower receptivity, we pollinated Col-0 flowers at the four stages of stigma senescence, and recorded seed set three days after pollination. This assay demonstrated a rapid decrease in seed yield associated with stigma collapse, with approximately 95 percent successful seed set recorded at stage 1, and only three percent at stage 4 (Fig 1d).

Other floral organs, such as the transmitting tract or ageing ovules, might also contribute to the loss of flower receptivity in senescent flowers. e therefore sought to confirm the correlation between stigma viability and flower receptivity independently by genetic ablation. To this end, we expressed the bacterial diphtheria toxin A chain (DT-A)24 under the stigma-specific S-locus-related gene 1 (SLR1) promoter25. The expression of DT-A blocked the elongation of papilla cells as described before26, and we detected precocious death of the developing papilla cells from flower stage 11c onward (Fig S1a,b). When pollinating DT-A expressing stigmata with WT pollen at the immature flower stages 11a and 11c, we observed a moderate seed set comparable to the WT at these stages (Fig S1c). However, when pollinated at the mature flower stage 13, pSLR1::DT-A plants set only 3 percent seed, whereas WT plants showed near full seed set (Fig S1c). We conclude that papilla cell viability is critical for effective pollination and seed set in Arabidopsis.

Senescing unpollinated papilla cells undergo dPCD

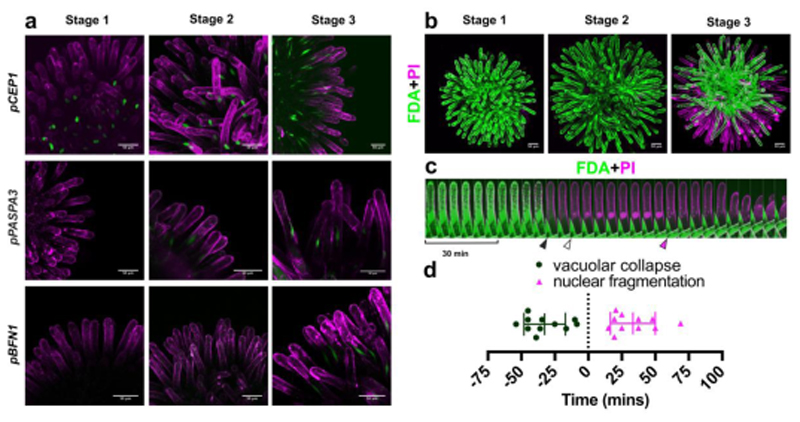

The reproducible timing of stigma degeneration culminating in the collapse of individual papilla cells suggested the presence of a tightly regulated organ senescence process, in turn terminated by an actively controlled programmed cell death. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed promoter-reporter lines of dPCD indicator genes that had been associated with several established systems of plant dPCD, including the anther tapetum, the xylem tracheary elements, and the lateral root cap of Arabidopsis 18,27. The expression of all tested dPCD indicator genes increased during stigma senescence. The nuclear GFP expression conferred by some dPCD promoter-reporter constructs was already detectable at stage 1, and increased throughout the later stages of stigma development (e.g. pCEP1≫H2A-GFP) (Fig 2a; Fig S2). Other reporters were detected from stage 2 (pPASPA3≫H2A- GFP), or only from stage 3 onward (pBFN1≫H2A-GFP) (Fig 2a; Fig S2). The age-dependent expression of these reporter constructs supports the existence of a canonical dPCD-like process acting to terminate the vital functions of senescing papilla cells.

Figure 2. Ageing unpollinated papilla cells die in a dPCD-like process.

a) Maximal projections of confocal microscopy images showing promoter-reporters of canonical dPCD-associated genes, which are expressed during stigma senescence. Green represents the nuclear-localized H2A-GFP reporter; magenta shows propidium iodide (PI) staining the cell wall. b) FDA (green) and PI (magenta) staining in different stages of stigma senescence shows loss of cellular viability in peripheral papilla cells at stage 3 by absence of FDA staining, and entry of PI into the dying cells. c) Kymograph of an individual papilla cell stained with FDA and PI, showing an attenuation of the FDA signal and vacuolar collapse (black arrowhead), followed by entry of PI in the nucleus (white arrowhead), abrupt nuclear fragmentation (magenta arrowhead), and cellular collapse. d) Quantification of the timing of vacuolar collapse and nuclear fragmentation in relation to PI entry into the nucleus (time point ‘0’). Scatter plot with mean±SD, n=11 cells from three different stigmata. Mean time of vacuolar collapse is -32.59 ± 15.44 minutes, mean time of nuclear fragmentation is 33.32 ± 16.8 minutes. Scale bars, 50 µm.

Next, we employed a live/dead stain combination of fluorescein diacetate (FDA) and propidium iodide (PI)28 to characterize the succession of cellular events in degenerating stigmatic papilla cells by live-cell imaging. Generally, cell death visualized by FDA/PI staining was non-synchronous, gradually progressing from the stigma periphery towards the stigma center (Fig 2b; Movie M3). Interestingly, when imaged in the genetic background of a tonoplast integrity marker line (ToIM) visualizing vacuolar collapse 18, papilla cells often did not die one by one, but together in small clusters of cells (Movie M4), thus pointing to the existence of a non-autonomous cell death trigger or a wave of cell- cell signaling. Whereas the degeneration of the entire stigma took up to 20 hours, the death of individual papilla cells occurred in a rapid succession of cellular events, executing cell death roughly one hour (Fig 2c-d; Movie M5). The collapse of the central vacuole as visualized by the uniform distribution of FDA in the entire cell volume, was the first notable cell death-associated event (Fig 2c-d). Vacuolar collapse occurred on average 30 minutes before plasma membrane permeation was indicated by PI entry into the cell (Fig. 2c-d). Finally, in the course of the following 50 minutes, PI- positive nuclei disintegrated abruptly (Fig 2c-d). Cellular collapse occurred last and its timing was more variable than that of the preceding events (Fig 2c; Movie M5).

In conclusion, both the expression of dPCD-associated genes and the organized succession of papilla cell dismantling indicate the existence of a tightly controlled program responsible for the preparation, triggering and execution of cell death in the senescent stigma.

ORE1 and KIR1 are highly expressed in senescent stigma

As a first step to unravel the molecular regulation of stigma degeneration and papilla cell death, we conducted a time course RNA-sequencing experiment in which we specifically sampled stigmata at different stages of senescence (stages 1 through 3). We identified a total of 1180 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) spread across the three stages of stigma development (FDR ≤ 0.05; Log2 Fold change ≥ 3). A co-expression cluster analysis performed on all nine replicates enabled the formation of two early expressed clusters that contained 283 down- and 500 up-regulated DEGs, the expression level of which changed step-wise in an age-dependent manner (Fig S3a, Supplementary Table ST1). A third cluster harbored 397 genes, peaking in expression level only at stage 3 of stigma senescence (Fig S3a). These substantial transcriptional changes and the large proportion of upregulated genes suggest that actively initiated and transcriptionally regulated processes occur in ageing stigmata.

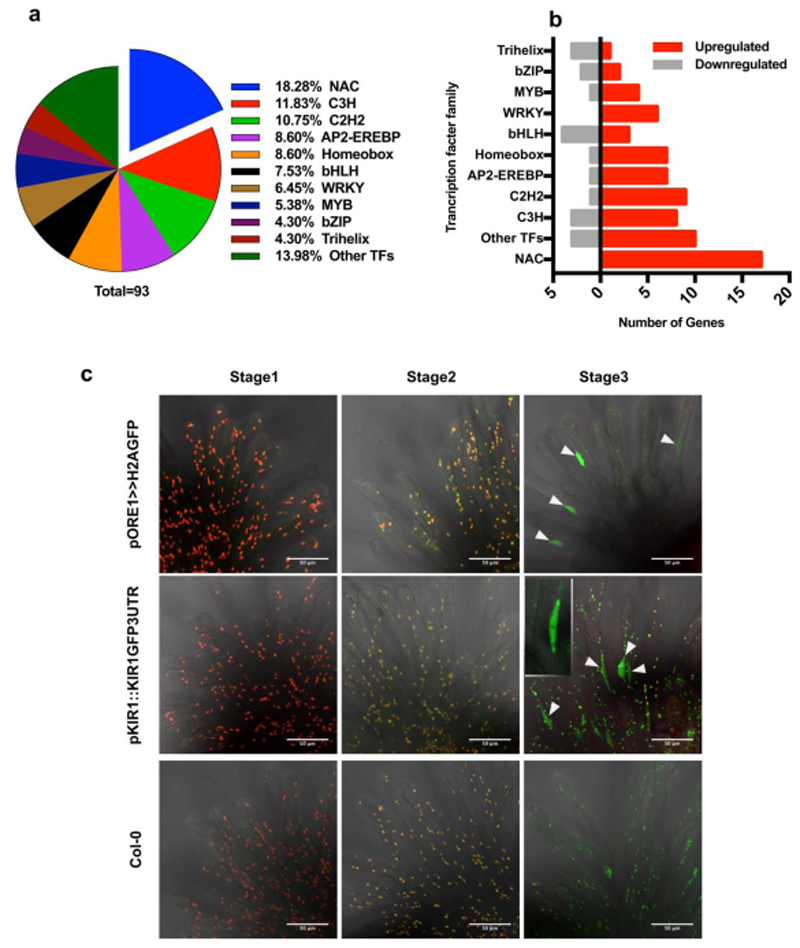

In order to identify major regulators responsible for the transcriptional reprogramming occurring during stigma senescence, we investigated the expression of transcription factors. NAC TFs represented the biggest fraction of up-regulated transcriptional regulators found in senescent stigmata (Fig 3a-b). Several members of the NAC TF family were co-expressed with the aforementioned dPCD-associated genes (Supplementary Table ST2). Among them, ANAC074 (hereafter called KIRA1/KIR1 after the killer in the Japanese manga “Death Note”), encoding a previously uncharacterized NAC transcription factor of unknown function, showed the strongest upregulation, as well as high transcript abundance at stage 3 (Supplementary Table ST2). Also the mRNA of ANAC092/ORESARA1 (ORE1), a well-established key regulator of leaf senescence29, was among the most highly upregulated NAC TFs mRNAs in the ageing stigma. We confirmed both the elevated expression of these transcriptional regulators as well as their co-expression with some dPCD-associated genes during stigma senescence via quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) (Fig S3b). Therefore, we focused on KIR1 and ORE1 to investigate flower-specific as well as general senescence-associated pathways functioning during stigma senescence.

Figure 3. KIR1 and ORE1 are upregulated in senescent papilla cells.

a) Pie-chart showing the percentage of differentially expressed transcription factors of major families, with NAC family members representing the largest fraction. b) 17 NAC transcription factors are significantly upregulated during stigma senescence, more than members of other transcription factor families. c) Maximal projections of confocal microscopy images showing red plastid auto-fluorescence and green GFP fluorescence. Both the pORE1≫H2A-GFP transcriptional reporter and the pKIR1::KIR1-GFP-3’UTR translational reporter show a GFP signal in the fusiform papilla nuclei at stage 3 (arrowheads). The nucleus of a single papilla cell is shown in the inset. Note the change in the plastid auto-fluorescence spectrum from red over yellow to green during ageing, possibly caused by chlorophyll degradation. Scale bars, 50 µm.

To analyze ORE1 and KIR1 gene expression patterns and protein localization, we produced GFP- tagged transcriptional and translational reporter lines for both genes. The expression of the GFP reporter controlled by a previously published 1.5kb ORE1 promoter19 conferred strong expression already in young stigmata (data not shown), and did not reproduce the stage-dependent accumulation of mRNA indicated by our RNA sequencing and RT-qPCR experiments. Hence, we produced a longer transcriptional reporter harboring a 2.5kb ORE1 promoter fragment, which did recapitulate the age-associated stigma expression of ORE1 mRNA (Fig 3c). In contrast, KIR1 promoter fragments varying from 1- to 5kb upstream of the start codon did not confer any expression of a reporter gene neither in young, nor in senescent stigmata (data not shown). Only by cloning a translational reporter containing a 5kb promoter fragment followed by the entire KIR1 genomic sequence, a C-terminally fused GFP sequence, and the 3’UTR of KIR1 (pKIR1::KIR1-GFP-3’UTR), did we generate a reporter construct recapitulating the RNA sequencing-derived expression patterns of KIR1 (Fig 3c). Possibly, regulatory elements located in the large introns or in the 3’UTR region of KIR1 are required for full control of KIR1 expression in the stigma.

ORE1 and KIR1 are partially redundant key regulators of stigma life span

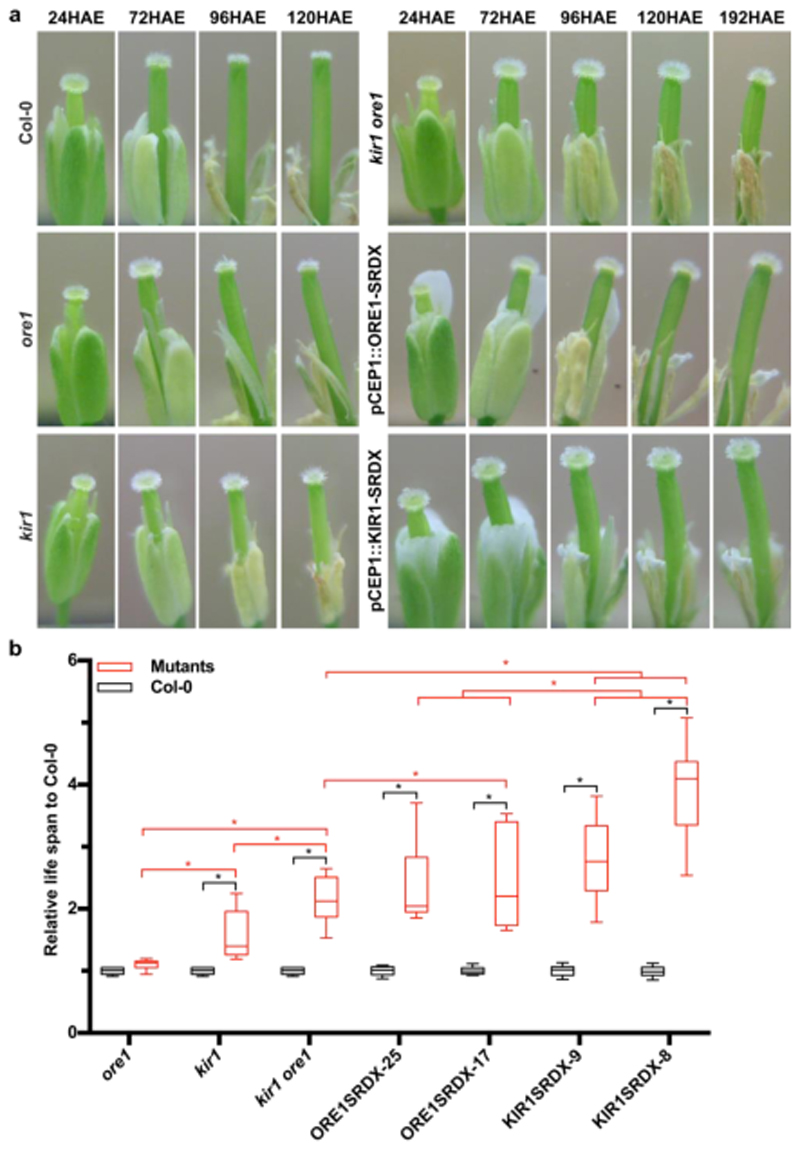

In order to investigate if ORE1 and KIR1 function in the control of stigma longevity, we phenotyped flowers of knock-out mutants in ORE1 (called ore1 in the following, published earlier as nac2-1 30), KIR1 (kir1-1 (GK_224_H08) and kir1-2 (SAIL_910_E07); see Fig S4a,b for mutant characterization). As kir1-1 carried an exonic T-DNA insertion causing a complete gene knock-out and it displayed a stronger stigma-senescence phenotype than kir1-2 (Fig S4c), we performed all subsequent experiments with this allele, called kir1 in the following.

Using the webcam phenotyping platform, we determined that ore1 mutant flowers showed a slight but not statistically significant extension of stigma life span (Fig 4a-b; Fig S5; Movie M6). In contrast, the kir1 mutant stigmata started to degenerate significantly later than the WT, on average at 95HAE (Fig 4a-b; Fig S5; Movie M6). In the ore1 kir1 double mutant, a synergistic effect on stigma lifespan was observed, with an average onset of stigma collapse only at 130HAE, about double of the WT stigma life span (Fig 4a-b; Fig S5; Movie M6). A qPCR analysis of ore1 kir1 and WT stigmata at 72HAE revealed significantly reduced expression levels of the dPCD markers BFN1, RNS3, EXI1 and DMP4 in the double mutant (Fig 5Sf). To confirm the role of KIR1 in promoting stigma cell death, we transformed the ore1 kir1 mutant with the proKIR1::KIR1-GFP-3UTR construct. Several independent lines showed a partial to full restauration of the wild-type phenotype (Fig 4Sd). These results suggest that ORE1 and KIR1 redundantly control stigma life span, with KIR1 playing a more substantial role than ORE1. To address genetic redundancy among the other upregulated NAC transcription factors, we created plant lines expressing ORE1 and KIR1 fusions with a dominant repressive domain (SRDX)31,32 controlled by the early senescence-activated promoter pCEP1 33 (Figure 2A). In the pCEP1::ORE1-SRDX lines with the strongest phenotypes, the first dying papilla cells were observed on average at 144 HAE (Fig 4a-b; Fig S5 and Movie M6). The pCEP1::KIR1-SRDX lines displayed an even stronger phenotype, with the stigmata only starting to collapse as late as 167 HAE, extending the stigma life span about four-fold in comparison to the WT (Fig 4a-b; Fig S5 and Movie M6). These results suggested that in addition to KIR1 and ORE1 other NAC TFs contribute to the control of stigma life span. Interestingly, the timing of papilla collapse was more varied in mutant lines than in Col-0, and mutant lines with a strong delay in the onset of stigma collapse tended also to show a longer time span until stigma collapse was complete (Movie M6). These observations suggest that KIR1 and ORE1 are not only necessary for the timely onset of stigma collapse, but also for the efficient completion of stigma degeneration.

Figure 4. ORE1 and KIR1 redundantly control stigma lifespan.

a) Representative snapshots of the webcam analysis of Col-0 and diverse ore1 and kir1 mutants. b) Quantitative analysis of the webcam experiments. In order to integrate several independent experiments in a comparative analysis, the lifespan of the stigmata in mutant lines was normalized to the Col-0 control in the individual experiments. While ore1 mutant stigmata live slightly but not significantly longer, kir1 and kir1 ore1 mutant stigmata are significantly longer living. Different independent lines of ORE1-SRDX and KIR1-SRDX show even stronger stigma life-extending effects. Black box-and-whiskers show Col-0 controls (from left to right, mean±SEM=1±0.014, 1±0.014, 1±0.014, 1±0.015, 1±0.017, 1±0.018, 1±0.018, N=15,15,15,20,13,20,17), red box-and-whiskers show mutants (from left to right, mean±SEM=1.101±0.020, 1.557±0.099, 2.139±0.091, 2.402±0.127, 2.472±0.213, 2.789±0.135, 3.881±0.196, N=15,15,15,19,14,20,14). Statistical differences were calculated using two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons by Fisher’s LSD test. Black asterisks indicate the comparison between Col-0 and mutants, red asterisks show the comparison between different mutants, significance levels at * P<0.05.

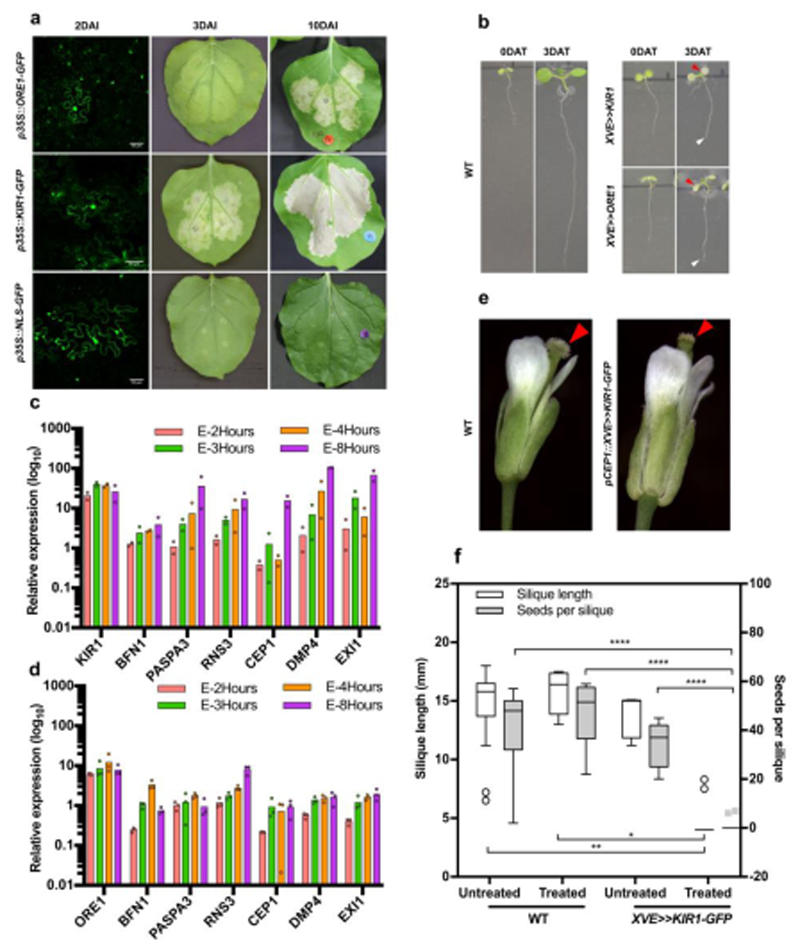

Figure 5. Overexpression of ORE1 and KIR1 induces senescence and cell death symptoms to varying degrees.

a) Tobacco leaf infiltration with Agrobacterium carrying p35S::ORE1-GFP leads to expression of senescence symptoms at three days after infiltration (DAI), and cell death symptoms at 10 DAI, while p35S::KIR1-GFP expression induces cell death symptoms already at 3 DAI. Infiltration with p35S::NLS-GFP plasmid is used as a negative control; the presence of GFP signal at 2DAI (green) in all samples indicates successful transfection. b) Five-day-old Col-0 wild-type (WT) plants and seedlings of a representative line for an estradiol-inducible pRPS5A::XVE≫KIR1-GFP and pRPS5A::XVE≫ORE1-GFP construct directly after and three days after transfer to estradiol-containing medium (DAT). Red arrowheads indicate chlorotic cotyledons, white arrowheads the growth-arrested root tip. c-d) Real-time quantitative PCR reveals an increased accumulation of dPCD- associated transcripts in response to time-course estradiol treatment of 5-day-old XVE≫KIR1-GFP (c) and pRPS5A::XVE≫ORE1-GFP (d) seedlings. Expression values are relative to the reference genes PEX4 and UBL5; a minimum of two biological replicates are shown (n=20 seedlings per replicate). Expression data of estradiol- treated lines is normalized to mock-treated samples. e) Representative Col-0 wild-type and pCEP1::XVE≫KIR1- GFP flowers after estradiol treatment. Whereas the Col-0 stigma appears still viable, the KIR1-GFP stigma appears collapsed (arrowheads). f) Representative Col-0 and pCEP1::XVE≫KIR1-GFP flowers after estradiol treatment and pollination. Whereas silique elongation in WT indicates successful pollination and seed development, in estradiol-treated transgenic lines silique elongation appears severely reduced, and seed set is absent. Box-and-whisker plots are calculated following the Tukey method; white box-and-whisker plots show the silique length (from left to right, mean±SD=14.413±3.504, 15.788±1.762, 13.760±18.04, 4.390±1.207, N=15,8,5,20.), grey box-and-whisker plots show the seeds per silique (from left to right, mean±SD=40.933±18.211, 47.000±13.038, 34.200±9.576, 0.650±2.007, N=15,8,5,20.). white circles and gray rectangles show the outliers. Statistical differences were calculated using two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons by Fisher’s LSD test. *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ****=p<0.0001. Scale bars, 50 µm.

ORE1 and KIR1 are sufficient to induce cell death

We next tested the effects of ectopic KIR1 and ORE1 expression. In agreement with its role as a leaf senescence regulator, transient overexpression of p35S::ORE1-GFP transgene in tobacco leaves triggered a senescence program causing leaf yellowing 3 days after infiltration (DAI), and chlorotic tissue lesions at 10 DAI (Fig 5a). Conversely, transient overexpression of p35S::KIR1-GFP induced extensive cell death lesions visible already at 3DAI-old leaves (Fig 5a). To test KIR1 and ORE1 gain-of- function in Arabidopsis, we generated stable estradiol-inducible overexpression lines34, pRPS5A::XVE≫ORE1-GFP and pRPS5A::XVE≫KIR1-GFP. Estradiol induction of several independent lines first triggered root growth arrest and later widespread systemic cell death in 5-day old Arabidopsis seedlings (Fig 5b; Fig S6; MovieM7). Cessation of root growth and extensive cell death were detected in KIR1-overexpressors approximately at 16.7 hours after induction (HAI), whereas in ORE1-overexpressors root growth arrest was only seen after 25.4 HAI on average, and ectopic cell death was less widespread in the root tips (Fig 5b; Fig S6; MovieM7). By means of RT-qPCR we showed that induction of either KIR1 or ORE1 in seedlings resulted in the up-regulation of several dPCD-associated genes from 2- to 8 hours after induction (HAI) (Fig 5c-d). The dPCD-associated nuclease BFN1, a direct target of ORE120, was strongly activated in pRPS5A::XVE≫ORE1-GFP expressing seedlings at 4HAI. In comparison, pRPS5A::XVE≫KIR1-GFP seedlings showed relatively higher activation of the dPCD markers RNS3, DMP4 and EXI1 at 4HAI. At 4HAI, the transcript levels of CEP1 were not highly up-regulated in any of the transgenic lines, thus suggesting that CEP1 is an indirect target of both KIR1 and ORE1. These results indicate that inducible overexpression of either KIR1 or ORE1 is sufficient to trigger ectopic cell death accompanied by the expression of dPCD- associated genes independently from the stigma tissue context.

When attempting to induce the expression of XVE≫KIR1-GFP in the stigma context by treating emasculated flowers with estradiol, stigma senescence occurred similarly to the WT. Conceivably, the pRPS5A promoter used in these constructs was too weak to show an appreciable effect in papilla cells. To solve this problem, we generated an additional estradiol-inducible construct expressing XVE≫KIR1-GFP under the early stigma-senescence activated CEP1 promoter (pCEP1::XVE≫KIR1- GFP). A screen of 25 independent T1 plants showed that 24 hours after local estradiol treatment of flowers, the stigmata of 20 out of 25 transgenic lines degenerated earlier than the WT (Fig 5e). Pollinations of the respective transgenic lines and Col-0 controls performed 24h after estradiol treatment resulted in a drastically decreased silique length and in a lack of seed set in the KIR1- expressing lines (Fig 5f). Attempts to reproduce these results in selected transgenic lines in the T2 and T3 generation failed, possibly due to silencing of the pCEP1::XVE≫KIR1-GFP construct (Fig 6Sf). We repeated the experiment with new T1 plants, obtaining similar results as in the first T1 assay, suggesting that KIR1 expression is sufficient to promote stigma degeneration and terminate floral receptivity (Fig 6Se).

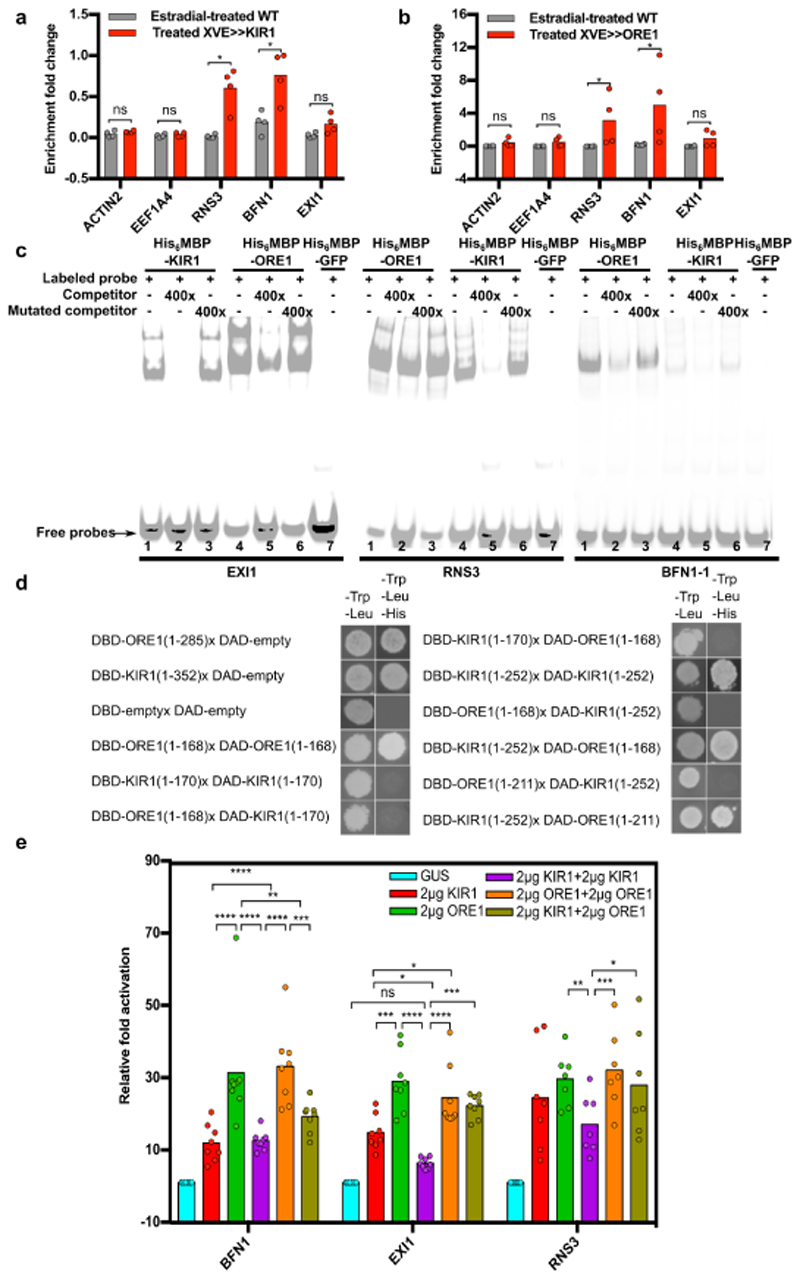

Figure 6. ORE1 and KIR1 homo- and heterodimers directly control expression of dPCD-associated genes.

a) ChIP-qPCR showing the enrichment of dPCD-associated promoter fragments 24 h after estradiol-induced overexpression of pRPS5A::XVE≫KIR1-GFP. b) ChIP-qPCR showing the percentage of enrichment of dPCD- associated genes 48 h after estradiol-induced overexpression of pRPS5A::XVE≫ORE1-GFP. In both A and B, gray bars indicate the estradiol-treated Col-0 control, red bars show estradiol-treated pRPS5A::XVE≫KIR1-GFP or pRPS5A::XVE≫ORE1-GFP, respectively. Promoter fragments from ACTIN2 and EEF1A were used as negative controls. A mean of two biological replicates per experiment is shown (each biological replicate includes two technical repeats). c) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay. Purified His6-MBP-KIR1 and His6-MBP-ORE1 bind in vitro to a 40-bp sequence of the EXI1, RNS3, and BFN1 promoters, a clear band shift can be seen for the tested promoter fragments. Generally, weaker band shifts were observed, when a non-labeled competitor probe (400-fold excess) was added. In contrast, strong band shifts were detected again when a mutated competitor was added. d) Left panel: Y1H auto-activation assay showing transcriptional activation of full-length ORE1 and KIR1 proteins fused to the DBD domain in absence of a DAD-fused protein partner. C-terminally truncated versions do not auto-activate transcription in yeast any more. Right panel: Y2H assay showing interactions of ORE1 and KIR1 as homodimers, and of ORE1 and KIR1 as heterodimers. Note that DBD-KIR1 interacts with DAD- ORE1, but not vice versa. e) Transient expression assay (TEA) in tobacco BY-2 protoplasts quantifying the activation of dPCD promoters by p35S::KIR1 and p35S::ORE1 constructs. Promoter activation was measured based on firefly luciferase activity controlled by pBFN1, pEXI1, and pRNS3, and normalized to Renilla luciferase controlled by the constitutive p35S promoter. Note that co-transfection with both KIR1 and ORE1 did not lead to an additive, nor to a synergistic effect on promoter activation of all tested dPCD-associated genes. To account for the doubled amount of TF added in the case of dimerization assays, the respective control assays contained doubled amounts of KIR1 and ORE1 (4µg total TF plasmid).

ORE1 and KIR1 directly regulate the expression of dPCD-associated genes

The transcriptome profiles of senescent stigmata, as well as the RT-qPCR of inducible lines, suggested that ORE1 and KIR1 might – directly or indirectly – regulate the expression of dPCD-associated genes.

To test whether ORE1 and KIR1 can bind promoter fragments of the dPCD-associated genes BFN1, RNS3, and EXI1 in planta, we performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation with quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR). Putative ORE1 binding sites located in the promoters of both RNS3 and EXI1 were inferred by computationally mapping TF binding sites (see Materials and Methods). In the case of KIR1, no binding site mapping data was available, so we used promoter fragments that were predicted to contain binding sites for other NAC transcription factors including ORE1. After induction of ORE1-GFP and KIR1-GFP expression by estradiol, the immuno-precipitated ORE1-GFP and KIR1- GFP fusion proteins were found to be significantly enriched with a DNA fragment containing an established BFN1 binding site20. Furthermore, both KIR1-GFP and ORE1-GFP pull-downs were significantly enriched with promoter fragments of RNS3, but not of EXI1 (Fig 6a-b). Based on this, we conclude that KIR1 and ORE1 interact with the promoter regions of RNS3 and BFN1.

To confirm these results, we conducted an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). The EMSA results showed that both ORE1 and KIR1 could physically interact in vitro with promoter fragments of RNS3 and BFN1, and in contrast to data obtained via ChIP-qPCR, also with that of EXI1 (Fig 6c). Since NAC proteins are known to form dimers to control gene transcription35, we investigated whether ORE1 and KIR1 were able to homo- or heterodimerize. Due to the inherent transcription-activating capability of the C-terminal transcriptional regulatory domain (TRD) of NAC proteins, NAC protein- protein interactions are difficult to assess in regular Yeast-Two-Hybrid (Y2H) assays36. Indeed, even in the absence of the GAL4 activation-domain (DAD-) containing prey construct, both full-length KIR1 (1- 352 AA) and ORE1 (1-285 AA) proteins were able to auto-activate transcription in yeast as DNA- binding domain (DBD-) bait construct (Fig 6d). To overcome this problem, we determined the TRD of both transcription factors by progressive truncation of their C-termini in a modified yeast-one-hybrid (Y1H) approach36 (Fig S7). The longest non-autoactivating versions of KIR1 (252AA) and ORE1 (211AA) were then transfected into tobacco leaves where they failed to trigger senescence and cell death, suggesting that their transcriptional regulatory efficiency was compromised (Fig S7). In the following Y2H screen, both truncated versions of ORE1 and KIR1 were able to interact with themselves, indicating the capacity to homo-dimerize (Fig 6d). Interestingly, the bait construct DBD- KIR1 (252 AA) interacted with DAD-ORE1 (Fig 6d). Though this interaction could not be confirmed in the inverse assay (ORE1 as bait and KIR1 as prey), our data suggest that ORE1 and KIR1 are able to hetero-dimerize. These results indicate that KIR1-ORE1 heterodimers might be formed, which could be important to modulate expression of PCD-associated target genes in the stigma.

To test the function of ORE1 and KIR1 as homo- or heterodimerizing transcriptional activators of dPCD-associated genes, we performed a dual luciferase transient expression assay (TEA) in protoplasts from BY-2 tobacco suspension cultures37. In the presence of p35S::KIR1, the firefly luciferase activity conferred by the reporter constructs pBFN1-FLuc, pEXI1-FLuc and pRNS3-FLuc increased more than tenfold over the p35S::GUS control plasmid (Fig 6e). A similar trend was observed in the presence of p35S::ORE1, which was able to activate the promoter BFN1 even more efficiently than p35S::KIR1 (Fig 6e). When co-transfecting the protoplasts with both p35S::ORE1 and p35S::KIR1, no significant activation increase could be observed (Fig 6e), suggesting that KIR1 and ORE1 do not act synergistically on these dPCD promoters in BY-2 protoplasts. These results do not support a functional role for a putative KIR1-ORE1 heterodimer I. However, the synergistic loss-of- function phenotype in the kir1 ore1 double mutant (Fig 4b) suggests that both ORE1 and KIR1 functions are relevant for the regulation of stigma senescence.

Taken together, our findings suggest that ORE1 and KIR1 can directly and indirectly activate the transcription of dPCD-associated genes, and that heterodimerization might optimize gene regulation.

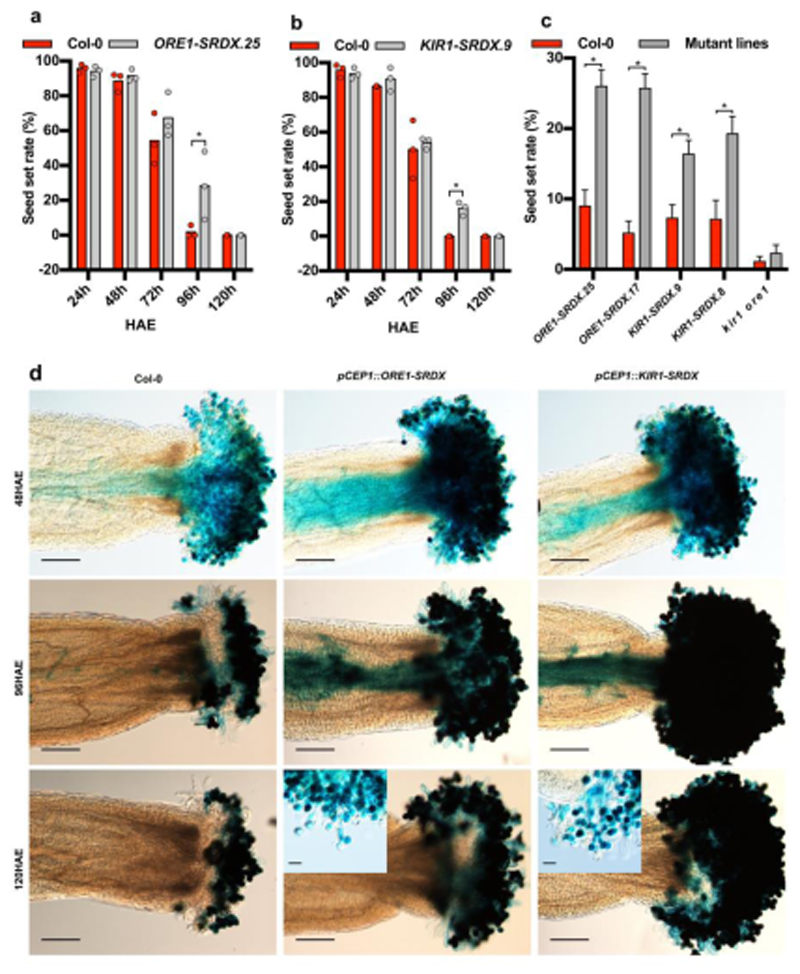

Floral receptivity is less extended than stigma life span in kir1 mutants

A major question arising from our results was whether the extended stigma life span of ORE1- and KIR1-deficient mutants leads to an extended EPP. To test this, we compared the seed set of three mutants with long-lived stigmata (ore1 kir1, ORE1-SRDX and KIR1-SRDX) to that of Col-0 flowers pollinated at 24-, 48-, 72-, 96- and 120HAE. Despite the dramatically prolonged stigma life span of the KIR1-SRDX and ORE1-SRDX lines, an extension of floral receptivity and seed set was only notable at 96HAE, but not at 120HAE (Fig 7a-b). The ore1 kir1 double mutant did not show an increased seed set potential even at 96 HAE (Fig 7c). In order to determine the reason for the lack of seed set despite the viability of mutant stigmata, we performed a pollen germination assay with pLAT52::GUS labeled pollen38. These experiments revealed that whereas pollen was still able to hydrate and germinate on aged ORE1- and KIR1-deficient stigma, pollen tube growth on the stigma was severely compromised, and pollen tubes did not reach the style or transmitting tract (Fig 7d; Fig S8). These results show that loss of ORE1 and KIR1 function is sufficient to substantially postpone papilla cell death in Arabidopsis, although it is not sufficient to extend the full spectrum of stigma-pollen interactions necessary to support pollen tube growth. Conceivably, parallel pathways to terminate stigma receptivity exist that target the compatible pollen pistil interaction.

Figure 7. Loss of KIR1 and ORE1 function moderately extends seed set in aged flowers.

a) Seed set assay of ageing Col-0 flowers versus ageing flowers of an ORE1-SRDX line showing a significant extension of floral receptivity only at 96 hours after emasculation (HAE). Three plants and one flower each were used per time point and per genotype; statistical differences were calculated using multiple t-test. b) The same assay showing a similar extension of floral receptivity in a KIR1-SRDX line. Three plants and one flower each were used per time point and per genotype. Statistical differences were calculated using multiple t-test; *=p<0.05. c) Comparison of the seed set in different genotypes after pollination at 96 HAE. Two independent ORE1-SRDX and KIR1-SRDX lines each show a significant extension of floral receptivity at this time point, whereas the kir1 ore1 double mutant shows no difference compared to the Col-0 wild type. * = p<0.05. Error bars show the standard error of the mean (SEM), Mean and SEM values were calculated from two independent experiments with 15 replicates, N=30. Statistical differences were calculated using multiple t-test. d) Pollen germination assay using pollen of a pLAT52::GUS reporter line. In accordance with the seed set assays, there is no qualitative difference between pollen tube growth towards the ovules after pollination at 48 HAE. In contrast to wild-type flowers, there are still pollen tubes growing through the styles in ORE1-SRDX and KIR1-SRDX flowers at 96 HAE. At 120 HAE, despite the viability of papilla cells in the ORE1-SRDX and KIR1-SRDX flowers, there are no pollen tubes growing through the style any more. In the last row of panels, higher magnification insets of ORE1-SRDX and KIR1-SRDX flowers at 120 HAE show that although many pollen grains still germinate, pollen tubes do not seem to grow effectively through the stigma any more. Scale bars, 200 µm in the main panels and 50 µm in the insets.

Discussion

Plant flowers have a species-specific functional life span, the EPP, during which pollination and fertilization have to occur to achieve successful sexual reproduction. It has been suggested that in the absence of pollination, a dedicated developmental program terminates the floral receptivity of ageing flowers39,40. However, the genetic mechanisms controlling these events at the level of the stigma as primary interface for pollination remain poorly understood.

Here we show that a developmental stage-induced PCD process in the stigmatic papilla cells is a key determinant of the EPP in Arabidopsis. Transcriptome profiling and promoter-reporter analyses revealed the upregulation of dPCD-associated genes in the ageing unpollinated stigma18. In Arabidopsis, many dPCD-associated genes are directly or indirectly controlled by various TFs in different cellular contexts, for instance by SOMBRERO (SMB/ANAC033) in the lateral root cap27, or by VASCULAR-RELATED NAC-DOMAIN 6 (VND6/ANAC101) in terminally differentiating tracheary elements41. ANAC045 and ANAC086 were shown to regulate nucleases to control the cell-death like enucleation process that occurs in maturating phloem sieve elements42. In the senescent stigma, both the recognized leaf-senescence regulator ORE1 and the previously uncharacterized NAC TF KIR1 were co-regulated with dPCD marker genes. Dominant loss-of-function of these TFs leads to a substantial extension of stigma life span, accompanied by a moderate prolongation of the EPP. Conversely, inducible expression of KIR1, and to a lesser extent of ORE1, was sufficient to trigger ectopic cell death independent of the stigma context, suggesting that these TFs can activate general cell-death promoting gene expression networks. Within the stigma context, precocious activation of KIR1 led to an early onset of papilla cell degeneration and a shortening of the EPP. This suggests that KIR1-controlled transcriptional changes effectively terminate stigma receptivity by inducing a canonical dPCD process in aged papilla cells.

Plant PCD types have been categorized based on morphological and biochemical characteristics43,44 or on their functional context16. The cellular morphology and the gene expression profiles of senescing stigmatic papilla cells suggest that papilla cell death represents a canonical dPCD process. As such it can be linked to established dPCD events occurring for instance in the xylem, the tapetum, or the root cap by the common expression of dPCD-associated genes18. In the morphological context, the vacuolar collapse was a prominent feature of papilla cell death, which occurred before plasma membrane permeation indicated by PI entry. This succession of events is reminiscent of xylem PCD45, but differs from the one recently described in root cap cell death, in which plasma membrane permeation precedes tonoplast rupture27. Vacuolar collapse and nuclear fragmentation have been described as hallmarks of vacuolar cell death in plants, 44, yet the precise time point of their execution might differ between PCD and cell types. The activation of transcriptional networks and the substantial delay of papilla cell death observed in kir1 ore1 loss-of-function mutants clearly demonstrates the active nature of the stigma degeneration process. As papilla cell death eventually does occur there might be other cell death regulators that are activated in absence of KIR1 function.

Surprisingly, the extension of stigma lifespan did not translate into a corresponding extension of the EPP. Whereas KIR1-SRDX mutants showed a moderate EPP extension of about 24 h, the EPP in the kir1 ore1 double mutant did not differ from the WT. The failure to extend EPP likely is caused by the stigma tissue itself, and not by other floral tissues, as pollen tube growth is already blocked shortly after germination on the viable but aged mutant stigmata. Similarly, haf bee1 bee3 mutants did not show an extension of the EPP although ageing unpollinated papilla cells failed to activate a pBFN1::GUS reporter gene and remained visibly intact longer than the WT46. Hence, whereas the loss of kir1 and ore1 functions effectively suppresses cell death initiation, it is not sufficient to maintain full papilla functionality. Either KIR1- and ORE1-independent pathways are activated to promote the cessation of papilla functions in ageing but viable mutant stigmata, or tissue senescence leads to a shut-down of stigma function characterized by the depletion of factors necessary for pollen-pistil interaction. A transcriptome profiling of viable, but no longer receptive KIR1-SRDX stigmata would provide clues to differentiate between these possibilities.

The investigation of floral longevity and EPP is a challenging field of plant biology, and of importance in both the horticultural as well as the agricultural context. In fruit producing crops, a short EPP can represent a major restriction for yield stability40,47. Also in staple crops such as wheat, rice, or maize, optimization of the period of floral receptivity could contribute to stabilization of seed yield, particularly under adverse environmental conditions. Whereas episodes of stressful growth conditions in the vegetative growth stages often can be compensated for during later time points, even short spells of environmental stresses during flowering can lead to irrevocable losses in seed or fruit yield48. Understanding the mechanisms of floral receptivity and senescence might generate new angles to improve crops for the environmental and societal challenges we are going to face in the decades to come.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana accession Columbia-0 (Col-0) was used as the wild type control (WT). The ore1 mutant allele used here was originally published as nac2-1 (SALK_090154) 30. The kir1 allele (GK_224H04) was obtained via the NASC seed stock center. Accession numbers of mentioned genes are ORE1 (AT5G39610), KIR1 (AT4G28530), CEP1 (AT5G50260), BFN1 (AT1G11190), RNS3 (AT1G26820), DMP4 (AT4G18425), EXI1 (AT2G14095), PASPA3 (AT4G04460), and SCPL48 (AT3G45010). Plants were grown on Jeffy-7 in plant growth chambers at 16-h light/ 8-h dark cycles at 20-22°C. Seedlings were grown vertically on ½ MS medium (2.15 g·L-1Murashige and Skoog salts, 0.1 g·L-1MES, pH 5.8 (KOH), 0.8 % agar) at 16-h light/ 8-h dark, 20-22°C.

Cloning and the Preparation of Transgenic Lines

Promoter-reporter lines for all dPCD-associated genes as well as the ToIM system used in this article were published by Fendrych et al.27 and Olvera-Carrillo et al18. KIR1 and ORE1 CDS without stop codons, as well as truncated versions of both genes, were recombined into the pDONR221 vector (Invitrogen). The dominant-negative versions of KIR1 and ORE1 (KIR1-SRDX and ORE1-SRDX) were constructed by two-step PCR, and were recombined into the pDONR221 vector (Invitrogen). The pSLR1, pUBQ10, pORE1 (1.5kb and 2.5kb promoter versions) were isolated from Col-0 genomic DNA using specific primers and adding BamHI and XhoI restriction sites to clone directionally into pENTRL4-R1 (Invitrogen), a Gateway-compatible entry vector containing a cassette with a multiple cloning sites (https://gateway.psb.ugent.be/). The DT-A coding sequence was derived from pTH1 as described24. The pSLR1 promoter was assembled either with DT-A or GFP into the destination vectors pB7m24GW,3 using LR clonaseII (Invitrogen). The pUBQ10 promoter49 was assembled with ToIM to the destination vectors pB7m24GW,3 using LR clonase II (Invitrogen).

The 5kb pKIR1 was isolated from Col-0 genomic DNA and recombined into the pDONRP4P1r vector (Invitrogen). The 2.5kb ORE1 promoters were assembled in a multisite Gateway reaction using LR clonase II+ (Invitrogen) with the GAL4 coding sequence and the destination vector pB9-H2A-UAS- 7m24GW to create activator lines as described18. These lines express a nuclear localized GFP reporter and can be used for UAS-Gal4 transactivation as described 50. The 1.5kb ORE1 and 5kb KIR1 promoter were assembled with pEN-L1-NF(NLSGFP)-L2, and pEN-R2-S(GUS)-L3 to the destination vectors pB7m34GW as described51. The 1.5kb ORE1 promoter was assembled with ORE1 and pEN-R2-F(GFP)- L3 to the destination vectors pB7m34GW (Invitrogen). The KIR1 5kb promoter was assembled with KIR1-GFP-3’UTR (synthesized by GenScript: http://www.genscript.com/) to the destination vector pB7m24GW,3. The promoter pCEP1 was cloned upstream of KIR1-SRDX and ORE1-SRDX into the destination vectors pB7m24GW,3. Primers used for PCR are listed in Supplementary Table ST3.

The expression clones obtained were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58C1 (pMP90) or GV3101(pMP90) competent cells using electroporation; next these bacteria were used for a modified floral dip method to stably transform Arabidopsis plants, Col-0 ecotype. The bacteria were first grown for 6 h at 28 °C in 1 mL of non-selective YEB broth (pre-culture), then 10 mL of YEB was added and the culture was left at 28 °C overnight. Plants were dipped in the overnight culture after the addition of 40 mL of floral dip medium (10% sucrose, 0.05% Silwet L-77). T1 plants were selected on antibiotics or BASTA and segregation analysis was performed on T2 plants. All further analyses were performed with homozygous single-locus T3 plants, unless listed otherwise.

Camera systems

A high-quality SLR imaging system was set in a tissue growth chamber (24h light, 20-22°C, humidity 50-65%), using a Canon EOS 650D camera controlled by Canon EOS Utility software, which was programmed to take an image every 30 mins. For higher throughput, web-camera phenotyping systems were set up in a semi-controlled imaging environment (24h light, 20-22°C, humidity 50-65%). Each system consisted of one computer and 10 Trust SpotLight Pro Web-cameras. Flowers were carefully positioned on hand-made holders and set in front of the web-cameras. Each camera records one picture every 10 minutes, allowing to follow 10 flowers in parallel. Two of such systems were used for phenotyping experiments.

Cryo-SEM imaging

Optical and cryo-scanning electron microscopy (cryo-SEM) was utilized to study the microstructure of the samples. Optical microscopy was done on Leica DM2500 microscope (Leica Micro-systems, Belgium). For cryo-SEM, samples of the emulsions were placed in the slots of a stub, plunge-frozen in slush nitrogen and transferred into the cryo-preparation chamber (PP3010T cryo-SEM Preparation System, Quorum Technologies, UK) where they were freeze-fractured, sublimated for 20 min and subsequently sputter-coated with Pt and examined by a JEOL JSM 7100F SEM (JEOL Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

Confocal imaging

Confocal images were acquired using an upright Zeiss LSM710, an inverted Zeiss LSM710, and an upright Zeiss LSM510. Objectives used were Water Immersion Plan-Apochromat 20x/1.0 DIC M27 75mm, W N-Achroplan 20x/0.5 W M27, Plan-Apochromat 40x/1.0 DIC M27 75mm, EC Plan-Neofluar 10x/0.3 M27 and Plan-Apochromat 20x/0.8. For stigmata stained with FDA/PI, FDA/PI was mix was dissolved in 1/10 MS (0.43 g·L-1MS salts, 20 μg·mL-1 FDA, 10 μg·mL-1 PI). For stigmata stained with PI, PI was dissolved in 1/10 MS (0.43 g·L-1MS salts, 10 μg·mL-1 PI). GFP and FDA were excited with the 488 nm laser line of the Argon laser and the emission was detected between 495-545 nm. PI was excited with a 561 nm diode laser and detected between 580 and 680 nm. All images were collected in 8 bit depth.

Isolation of papilla cells, extraction of total RNA and sample preparation for RNA sequencing

For RNA-sequencing, WT Col-0 flowers were emasculated at flower stage 12c. Papilla cells were manually dissected from the pistil with hypodermic needles under binocular microscope and flash- frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted in three independent biological replicates, from about 200 stigmata per replicate, at stage 1, 2 and 3, representing the young, mature and senescent stage, respectively. RNA was extracted using the Spectrum Plant Total RNA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). RNA quantity and quality was assessed by spectrophotometric analysis (NanoDrop ND-2000, Thermo) and on-chip electrophoresis (RNA 6000 Nano Kit, Agilent). Total RNA samples with a quality value greater than RIN = 6 were used for Illumina HiSeq-based sequencing resulting in 100bp paired-end reads.

Sequence data processing and DEG analysis

After RNA-sequencing, the resulting BAM files were imported to the Galaxy Workflow Environment52. Sequencing data were sorted and the paired reads were mapped to genomic regions using an A. thaliana annotation file (TAIR10), a GFF3 format file downloaded from Ensembl Plants (http://plants.ensembl.org). To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) during stigma senescence, statistical analysis was carried out using edgeR package by R 3.3.1 in the graphical environment of RStudio (http://www.rstudio.com/)53,54. Read counts per gene locus were calculated from reads mapped to the genome. The expression genes were filtered as over 1 counts per million (CPM) present in at least 3 samples. The expression values were normalized by the “trimmed-mean of M-values” (TMM) normalization method. We defined DEGs as genes with a CPM value showing a ≥ 3-fold change in expression at a false discovery rate of ≤0.05 during stigma senescence. Gene annotations were added using Biomart Ensembl Plants (http://plants.ensembl.org/biomart/). Functional categorization of DEGs by GO was performed using GO annotations from the TAIR website (http://www.Arabidopsis.org). GO term enrichment of DEGs was performed using DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/). Gene function classification was analyzed using MapMan 3.6. Cluster analysis of DEGs was performed using K-means clustering method in MeV 4.8.1 (http://mev.tm4.org/). The number of clusters was evaluated with the Figure-of Merit algorithm implemented in MeV 4.8.1. TF identification and categorization was analyzed using AGRIS AtTFDB (http://Arabidopsis.med.ohio-state.edu/AtTFDB/). The complete RNA sequencing data set has been made publically available in ArrayExpress https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress (accession code E-MTAB-6279).

Tobacco infiltration

The coding sequences of KIR1 and ORE1 were fused to the one of GFP, and placed under the control of the CaMV p35S promoter in the destination vector pB7GW34. The truncated KIR1 (1-252 AA) and ORE1 (1-211 AA) were constructed in the destination vector pB7WG2D,1, which contains the endoplasmic reticulum ER-GFP marker as visible transfection control55. Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants were grown in soil for 4–6 weeks before infiltration with a suspension of transformed Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells suspended at a cell density OD600 of 1.5 in an infiltration medium (10 mM MgSO4, 10 mM MES at pH 5.8, 100 μM acetosyringone).

TEA assay

As the effectors, the p35S::ORE1 and p35S::KIR1 were transformed into protoplasts in the presence of: 1) a reporter containing the promoter of a given candidate reporter gene fused to the firefly luciferase coding region (pPCD–FLuc) and 2) a transfection normalization vector containing the p35S- driven Renilla luciferase coding region (p35S–RLuc). In addition, the p35S::GUS was used as the negative control representing a protein unable to interfere with gene transcription. The TEA assay was performed as previously described37.

TF binding site mapping for the design of EMSA probes

108 and 623 positional frequency matrices that were obtained from protein-binding microarray studies56,57 were mapped on an extended locus, spanning 2kb upstream, introns and 1kb downstream regions with the exons masked, for each gene in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. All matrices were mapped using MatrixScan and filtered on a p-value cutoff <= 1e-0458. This dataset was further filtered to the binding sites of 20 TFs targeting 45 genes involved in programmed cell death. The retrieved binding sites were extended with 10 bp on each side to serve as templates for the design of EMSA probes.

Protein purification and EMSA

For protein expression and purification, the ORE1 and KIR1 coding sequences and GFP were recombined into the Gateway vector pDEST-HisMBP59, and transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). When cell density (OD600) reached 0.6, protein expression in 1L cultures was induced at 18°C by addition of 1 mM isopropyl thio-β-D-galactoside in the course of 16 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 5 mM DTT, 1% Triton X-100 and 0.75 mg·mL-1 lysozyme and incubated on ice for 30 mins. Following sonication, the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 20 mins. Ni-NTA Agarose was used for purification of His-tagged proteins by gravity-flow chromatography according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Concentrations of purified proteins were determined with Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit. EMSA probess using 5′-IRDye®700-labeled DNA fragments were synthetized by IDT (Supplementary Table ST3). EMSAs were performed using Odyssey infrared EMSA Kit from LI-COR and following the protocol of the manufacturer.

ChIP-qPCR

ChIP-qPCR was performed as described19, with modifications of the seedling harvesting procedure. In short, approximately 150 mg seeds from representative transgenic lines carrying proRPS5A::XVE≫KIR1-GFP and proRPS5A::XVE≫ORE1-GFP were grown for 6 days in 600 mL liquid ½ MS medium (2.15 g·L-1 Murashige and Skoog salts, 0.1 g·L-1 MES, pH 5.8 with KOH), with a constant shaking. After 6 days, the expression of both transgenes was induced with 0.6 mL 10 mM β-estradiol dissolved in DMSO (to a final concentration of 10 µM). After 24- (KIR1) and 48 hours of estradiol induction (ORE1), respectively, seedlings were washed three times with distilled water, soaked on a paper tissue and ground to a powder in liquid nitrogen. Plant material was lysed and crosslinked using formaldehyde. The crosslinking reaction was stopped using glycine. Nuclei were isolated and lysed in a sucrose gradient and the chromatin obtained was fragmented by sonication (Bioruptor Next Gen, Diagenode). Immunoprecipitations were performed using anti-GFP (Abcam; http://www.abcam.com)-coated IgA magnetic beads (Dynabeads protein G 1003D, Invitrogen). Protein–DNA complexes were eluted using 0.1M NaHCO3 and 1% w/w SDS. Reverse DNA crosslinking was performed in two steps: overnight at 65 °C using 0.2 M NaCl and 1 h incubation at 45 °C adding 10 μl 0.5 M EDTA, 20 μl 1 M Tris HCl pH 6.5 and 2 μl 10 mg ml−1 proteinase K. DNA was extracted using phenol-chloroform isoamyl alcohol pH8 and precipitated with sodium acetate/glycogen/ethanol60. The qPCR analysis was performed with 0.5 μl of sample per reaction using and the LC480 SYBR Green I Master Kit (Roche Diagnostics) on a Roche LightCycler 480 system. For each pair of primers (Supplementary Table ST3), normalization to DNA input was carried out. The fold enrichment was calculated as relative to Col-0 wt using the ΔCt expression values.

Gene expression induction experiments

Inducible gene expression was carried out by means of an estradiol-based inducible gene expression system34. The estradiol-inducible chimeric expression activator XVE was placed under the control of different promoters (pRPS5A and pCEP1) via PCR and classical cloning. The promoter fragments were amplified by PCR (Kpn1-CEP1-F and Xho1-CEP1-R for pCEP1; XhoI_RPS5A_FW and XhoI_RPS5A_REV for pRPS5A), followed by restriction digest, and ligated upstream of the XVE cassette in p1R4-ML- XVE, and recombined into an expression vector as described34 driving ORE1-GFP or KIR1-GFP fusion constructs. The cloned region and insertion orientation were sequence verified. Estradiol induction of seedlings on plates was performed as described in the ChIP section above. Estradiol induction of flowers was performed on flowers that had been emasculated at stage 12c. 24h after emasculation, the stigma and tips of petals were dipped into 350µL estradiol working solution (100µM β-estradiol by diluting a 100mM DMSO-based stock solution in 1/20MS) contained in an upside-down PCR tube. Treatment lasted 6 hours, evaporated liquid was replaced by working solution. Analysis of the stigmata occurred 20h after the treatment. After visual inspection, maximal pollination was performed. Silique length and seed set were determined 5 days after pollination.

RT-qPCR

A total amount of 1 µg purified RNA was subjected to cDNA synthesis with iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad). The resulting cDNA was dissolved in ultra-pure water and mixed with LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche) and 0.5 µM gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table ST3) using JANUS automated pipetting station (Perkin Elmer). RT-qPCR was performed with a Light-Cycler system (Roche) in a program of 45 amplification cycles and primer annealing temperature of 60°C. RT-qPCR data was analysed with Qbase+ software (BioGazelle, Belgium). Relative expression levels were calculated based on two reference genes (ACTIN and EEF1A for stigma samples; PEX4 and UBL5 for seedlings).

Pollination assay

Flowers were emasculated at flower stage 12c. Stigmata were maximally pollinated at 24-, 48-, 72-, 96-, and 120 HAE. Seeds and unfertilized ovules were counted under binocular microscope (Leica) 5 days after pollination. Seed set rate = seed numbers / (seed and unfertilized ovule numbers) %.

Pollination analysis with GUS staining

For analysis of GUS-positive pollen on stigma, pLAT52::GUS pollen was used to pollinate stigmata61. GUS staining of pollinated pistils was performed 16 hours after pollen application as described62. Samples were photographed using an Olympus BX51 with Nikon Digital Sight DS-L2.

Protein interaction assays in yeast

To detect intrinsic transcriptional activity and protein–protein interaction, ORE1 and KIR1 were examined for the presence of an activation domain and for their ability to bind as heterodimer and homodimer using the yeast-one- and yeast-two-hybrid systems. Full-length and truncated versions of the NAC TF encoding sequences were amplified using sequence specific primers and recombined into the pDEST32/pDEST22 vectors (Invitrogen). Plasmids were transformed into yeast strain pJ694A and assayed as described63.

Statistical analysis, image analysis and figure preparation

Statistical data were analyzed in Graphpad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA, www.graphpad.com). Statistical images were generated by Graphpad Prism 7. Camera and confocal images were prepared with ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/)64, the only manipulation of images were histogram adjustments. The figures were then assembled in Inkscape (https://inkscape.org).

Reporting Summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the PCD lab for discussions and critical feedback on the manuscript, Veronique Storme for assistance with statistical analysis, and Annick Bleys for help with the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge funding from the CSC for ZG, the FWO project G011215N for AD, an IWT fellowship for MD, and funding from the BELSPO for YS. The Hercules foundation is acknowledged for its financial support in the acquisition of the scanning electron microscope JEOL JSM-7100F equipped with the cryo-transfer system Quorum PP3010T (grant no. AUGE-09-029) used in this research.

Footnotes

Detailed author contributions

ZG devised and performed most experiments of this study, including, plasmid construction; phenotyping of mutant lines via camera systems; RNA-Seq and data analysis; yeast assays; tobacco infiltration; protein purification and EMSA; pollination assay and GUS staining; cryo-SEM imaging; data analysis, manuscript and figure preparation.

AD devised and performed many experiments of this study, including confocal microscopy (movies + PCD markers); RT- and ChIP-qPCR experiments; TEA of BY-2 protoplasts; cluster analysis of RNA-Seq data; design of estradiol-inducible OE lines (pRPS5A::XVE≫KIR1-GFP; pRPS5A::XVE≫ORE1-GFP; pCEP1::XVE≫KIR1-GFP); analysis of estradiol-inducible seedlings; analysis of kir1-2; and tissue harvesting for RNA-Seq; manuscript preparation.

YS performed stigma-specific promoter cloning; expression analysis of promoter-reporter lines of senescence-associated and stigma-specific genes; establishment of cellular PCD markers-such as vacuolar collapse; nuclear fragmentation and staging of the process; preparation for RNA seq.

MD produced the dominant repressive KIR1 and ORE1 constructs, the transcriptional and translational reporters for ORE1, and genotyped the nac2-1 (ore1) mutant.

MH designed, performed, and analyzed the EMSA experiments.

ZL performed and analyzed the flower-specific estradiol induction experiments.

FDW designed, performed, and analyzed the transient expression assays (TEAs).

SV cloned and established the pRPS5A::XVE estradiol-inducible module.

MK cloned the pCEP1::XVE estradiol-inducible module.

JV and KV performed TF binding site analyses.

DW and KD actively contributed to, and described the methodology of the cryo-SEM experiments; reviewed the manuscript prior to submission.

BL contributed to the setup of papilla live cell imaging.

MN devised and directed the research project, performed flower-specific gene induction experiments, and prepared the manuscript.

Data availability

The RNA-sequencing data set characterizing stigma senescence has been made publically available in ArrayExpress (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress; accession number E-MTAB-6279). All other data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

- 1.Rogers HJ. From models to ornamentals: how is flower senescence regulated? Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 2013;82:563–574. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9968-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones ML. Ethylene signaling is required for pollination-accelerated corolla senescence in petunias. Plant Science. 2008;175:190–196. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams RR. The Effect of Summer Nitrogen Applications on The Quality of Apple Blossom. Journal of Horticultural Science. 1965;40:31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Primack RB. Longevity of Individual Flowers. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1985;16:15–37. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahri W, Tahir I. Flower senescence: some molecular aspects. Planta. 2014;239:277–297. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1984-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibuya K, Yamada T, Ichimura K. Morphological changes in senescing petal cells and the regulatory mechanism of petal senescence. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:5909–5918. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broderick SR, et al. RNA-sequencing reveals early, dynamic transcriptome changes in the corollas of pollinated petunias. BMC plant biology. 2014;14:307. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0307-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagstaff C, Yang TJ, Stead AD, Buchanan-Wollaston V, Roberts JA. A molecular and structural characterization of senescing Arabidopsis siliques and comparison of transcriptional profiles with senescing petals and leaves. Plant J. 2009;57:690–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibuya K, Shimizu K, Niki T, Ichimura K. Identification of a NAC transcription factor, EPHEMERAL1, that controls petal senescence in Japanese morning glory. Plant J. 2014;79:1044–1051. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HJ, et al. Gene regulatory cascade of senescence-associated NAC transcription factors activated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE2-mediated leaf senescence signalling in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:4023–4036. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JH, et al. Trifurcate feed-forward regulation of age-dependent cell death involving miR164 in Arabidopsis . Science. 2009;323:1053–1057. doi: 10.1126/science.1166386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang X, et al. A Petunia homeodomain-leucine zipper protein, PhHD-Zip, plays an important role in flower senescence. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen MK, et al. The MADS box gene, FOREVER YOUNG FLOWER, acts as a repressor controlling floral organ senescence and abscission in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2011;68:168–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas H. Senescence, ageing and death of the whole plant. New Phytologist. 2013;197:696–711. doi: 10.1111/nph.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickman M, Williams B, Li Y, Figueiredo P, Wolpert T. Reassessing apoptosis in plants. Nat Plants. 2017;3:773–779. doi: 10.1038/s41477-017-0020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daneva A, Gao Z, Van Durme M, Nowack MK. Functions and Regulation of Programmed Cell Death in Plant Development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2016;32:441–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-111315-124915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huysmans M, Lema AS, Coll NS, Nowack MK. Dying two deaths - programmed cell death regulation in development and disease. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017;35:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olvera-Carrillo Y, et al. A Conserved Core of Programmed Cell Death Indicator Genes Discriminates Developmentally and Environmentally Induced Programmed Cell Death in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:2684–2699. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balazadeh S, et al. A gene regulatory network controlled by the NAC transcription factor ANAC092/AtNAC2/ORE1 during salt-promoted senescence. Plant Journal. 2010;62:250–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matallana-Ramirez LP, et al. NAC transcription factor ORE1 and senescence-induced BIFUNCTIONAL NUCLEASE1 (BFN1) constitute a regulatory cascade in Arabidopsis . Molecular plant. 2013;6:1432–1452. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heslop-Harrison Y, Shivanna KR. The Receptive Surface of the Angiosperm Stigma. Annals of Botany. 1977;41:1233–1258. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dresselhaus T, Franklin-Tong N. Male-female crosstalk during pollen germination, tube growth and guidance, and double fertilization. Molecular plant. 2013;6:1018–1036. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christensen CA, King EJ, Jordan JR, Drews GN. Megagametogenesis in Arabidopsis wild type and the Gf mutant. Sex Plant Reprod. 1997;10:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weijers D, Van Hamburg JP, Van Rijn E, Hooykaas PJ, Offringa R. Diphtheria toxin- mediated cell ablation reveals interregional communication during Arabidopsis seed development. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:1882–1892. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.030692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hackett RM, Cadwallader G, Franklin FC. Functional analysis of a Brassica oleracea SLR1 gene promoter. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1601–1607. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.4.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorsness MK, Kandasamy MK, Nasrallah ME, Nasrallah JB. Genetic Ablation of Floral Cells in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1993;5:253–261. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.3.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fendrych M, et al. Programmed cell death controlled by ANAC033/SOMBRERO determines root cap organ size in Arabidopsis . Current Biology. 2014;24:931–940. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones K, Kim DW, Park JS, Khang CH. Live-cell fluorescence imaging to investigate the dynamics of plant cell death during infection by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. BMC plant biology. 2016;16:69. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0756-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HJ, Nam HG, Lim PO. Regulatory network of NAC transcription factors in leaf senescence. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016;33:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He XJ, et al. AtNAC2, a transcription factor downstream of ethylene and auxin signaling pathways, is involved in salt stress response and lateral root development. Plant J. 2005;44:903–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hiratsu K, Matsui K, Koyama T, Ohme-Takagi M. Dominant repression of target genes by chimeric repressors that include the EAR motif, a repression domain, in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003;34:733–739. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitsuda N, et al. CRES-T, an effective gene silencing system utilizing chimeric repressors. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;754:87–105. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-154-3_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou LZ, et al. Expression analysis of KDEL-CysEPs programmed cell death markers during reproduction in Arabidopsis. Plant reproduction. 2016;29:265–272. doi: 10.1007/s00497-016-0288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siligato R, et al. MultiSite Gateway-Compatible Cell Type-Specific Gene-Inducible System for Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:627–641. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsen AN, Ernst HA, Leggio LL, Skriver K. NAC transcription factors: structurally distinct, functionally diverse. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Shea C, et al. Protein intrinsic disorder in Arabidopsis NAC transcription factors: transcriptional activation by ANAC013 and ANAC046 and their interactions with RCD1. Biochem J. 2015;465:281–294. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanden Bossche R, Demedts B, Vanderhaeghen R, Goossens A. Transient expression assays in tobacco protoplasts. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2013;1011:227–239. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-414-2_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson MA, et al. Arabidopsis hapless mutations define essential gametophytic functions. Genetics. 2004;168:971–982. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.029447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carbonell-Bejerano P, Urbez C, Carbonell J, Granell A, Perez-Amador MA. A fertilization-independent developmental program triggers partial fruit development and senescence processes in pistils of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:163–172. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.160044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanzol JH, M The “effective pollination period” in fruit trees. Scientia Horticulturae. 2001;90:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohashi-Ito K, Oda Y, Fukuda H. Arabidopsis VASCULAR-RELATED NAC-DOMAIN6 directly regulates the genes that govern programmed cell death and secondary wall formation during xylem differentiation. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3461–3473. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furuta KM, et al. Arabidopsis NAC45/86 direct sieve element morphogenesis culminating in enucleation. Science. 2014;345:933–937. doi: 10.1126/science.1253736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Doorn WG. Classes of programmed cell death in plants, compared to those in animals. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2011;62:4749–4761. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Doorn WG, et al. Morphological classification of plant cell deaths. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2011;18:1241–1246. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Obara K, Kuriyama H, Fukuda H. Direct evidence of active and rapid nuclear degradation triggered by vacuole rupture during programmed cell death in Zinnia. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:615–626. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crawford BC, Yanofsky MF. HALF FILLED promotes reproductive tract development and fertilization efficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2011;138:2999–3009. doi: 10.1242/dev.067793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferradás Y, López M, Rey M, González MV. Programmed cell death in kiwifruit stigmatic arms and its relationship to the effective pollination period and the progamic phase. Annals of Botany. 2014;114:35–45. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bac-Molenaar JA, et al. Genome-Wide Association Mapping of Fertility Reduction upon Heat Stress Reveals Developmental Stage-Specific QTLs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2015;27:1857–1874. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grefen C, et al. A ubiquitin-10 promoter-based vector set for fluorescent protein tagging facilitates temporal stability and native protein distribution in transient and stable expression studies. Plant J. 2010;64:355–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]