Abstract

Snakebite envenoming causes 138,000 deaths annually, and ~400,000 victims are left with permanent disabilities. Envenoming by saw-scaled vipers (Viperidae: Echis) leads to systemic hemorrhage and coagulopathy, and represents a major cause of snakebite mortality and morbidity in Africa and Asia. The only specific treatment for snakebite, antivenom, has poor specificity, low affordability, and must be administered in clinical settings due to its intravenous delivery and high rates of adverse reactions. This requirement results in major treatment delays in resource-poor regions and substantially impacts on patient outcomes after envenoming. Here we investigated the value of metal ion chelators as pre-hospital therapeutics for snakebite. Among the tested chelators, dimercaprol (British anti-Lewisite) and its derivative 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonic acid (DMPS), were found to potently antagonize the activity of Zn2+-dependent snake venom metalloproteinases in vitro. Moreover, DMPS prolonged or conferred complete survival in murine preclinical models of envenoming against a variety of saw-scaled viper venoms. DMPS also considerably extended survival in a ‘challenge and treat’ model, where drug administration was delayed after venom injection, and the oral administration of this chelator provided partial protection against envenoming. Finally, the potential clinical scenario of early oral DMPS therapy combined with a delayed, intravenous dose of conventional antivenom provided prolonged protection against the lethal effects of envenoming in vivo. Our findings demonstrate that the safe and affordable repurposed metal chelator DMPS can effectively neutralize saw-scaled viper venoms in vitro and in vivo and highlights the promise of this drug as an early, pre-hospital, therapeutic intervention for hemotoxic snakebite envenoming.

Introduction

Snakebite envenoming is a neglected tropical disease (NTD) that affects ~5 million people worldwide each year, and leads to high mortality (~138,000/year) and morbidity (~400,000-500,000/year), particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia (1). In West Africa, the economic burden of snakebite has been estimated at 320,000 Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) annually - a number higher than most other NTDs, including leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis, and onchocerciasis (2). The highest burden of snakebite is suffered by the rural impoverished communities of low and middle income countries, who often rely on agricultural activities for their income (3). These activities put them at risk of snakebite by being exposed to environments inhabited by venomous snakes, and the remoteness of many of these communities makes accessing healthcare problematic (4). Consequently, it is estimated that 75% of snakebite fatalities occur outside of a hospital setting (5), as victims are often delayed in reaching a healthcare facility due to long travel times and/or suboptimal health-seeking behaviors. Crucially, treatment delays are known to result in poor patient outcomes, and often lead to life-long disabilities, psychological sequelae, or death (6, 7). Further compounding this situation, species-specific antivenom, the only appropriate treatment for snakebite (1, 3), is often unavailable locally and, when present, is exceedingly expensive relative to the income of snakebite victims, despite being classified by the WHO as an essential medicine (8). Consequently, snakebite was classified as a ‘priority NTD’ by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017. Subsequently, the WHO has developed a strategy proposed to halve the number of snakebite deaths and disabilities by the year 2030, by improving existing treatments, developing new therapeutics, and empowering local communities to improve pre-hospital treatment (9).

Snake venoms are mixtures of numerous toxin isoforms encoded by multiple gene families, whose composition varies both inter- and intra-specifically (10, 11). Venom variation makes the development of pan-specific snakebite treatments challenging due to the multitude of drug targets that need to be neutralized for any particular geographical region. Antivenoms consist of polyclonal antibodies (IgG or IgG-derived F(ab’)2 or Fab fragments) purified from the serum or plasma of animals hyperimmunized with snake venom(s). Venom toxin variation results in these products typically having limited or no efficacy against snake venoms not used in the manufacturing process (12). Furthermore, antivenoms have poor dose efficacy (only ~10-20% of antibodies are specific to venom toxins (13)), must be delivered intravenously, and have a high incidence of adverse reactions (as high as 75% of cases (14)), meaning that they must be delivered in a clinical setting (1). As advocated by the WHO (9), there is an urgent need for the development of rapid, effective, well-tolerated, and affordable interventions for treating tropical snakebite (9). Ideally, initial interventions would be safe for use outside of a clinical environment, thus facilitating rapid administration in a community setting and likely improving patient outcomes.

The use of small molecule inhibitors to generically target key classes of snake venom toxins has recently attracted renewed interest as a potential therapeutic alternative to antivenom (15). Varespladib, a secretory phospholipase A2 (PLA2) inhibitor, has emerged as a promising drug candidate that protects against venom-induced lethality and limits the pathology associated with certain snakebites in preclinical animal models (16, 17). Varespladib was found to be particularly effective against PLA2-rich elapid venoms, but also showed some efficacy against a number of viper venoms (18). Molecules that counteract the activity of snake venom metalloproteinase (SVMPs) toxins have also been investigated in this regard. SVMPs are Zn2+-dependent, enzymatically active hemotoxins (19) involved in causing systemic hemorrhage and coagulopathy by actively degrading capillary basement membranes and/or interacting with key components of the blood clotting cascade (20). They are often the major toxin constituents of viper venoms (21). Peptidomimetic hydroxamate inhibitors that block the catalytic site of SVMPs (for example batimastat and marimastat) have been shown to abolish the local and systemic toxicity induced by saw-scaled viper (Echis ocellatus) venoms from Cameroon and Ghana (22), and dermonecrosis and hemorrhage caused by the venom of the Central American fer-de-lance (Bothrops asper) (23). Similarly, metal ion chelators (referred to as metal chelators hereafter) that deplete the Zn2+ pool required for SVMP function, including EDTA (23, 24), can prevent hemorrhage, myotoxicity, and/or lethality caused by E. ocellatus or E. carinatus venoms (25, 26). These previous studies suggest that small molecule inhibitors targeting SVMPs may represent good candidates for delaying or even neutralizing the toxicity caused by SVMP-rich venoms. However, neither marimastat nor batimastat are currently available as licensed medicines, whereas EDTA is not desirable for further development as a therapeutic due to its poor specificity for zinc and high affinity for calcium, its poor safety profile, as well as a requirement for slow intravenous administration, which makes it unsuitable for use as a pre-hospital therapeutic (27).

Saw-scaled vipers (Viperidae: Echis spp.) represent one of the most medically-important groups of venomous snakes, with a broad distribution through Africa north of the equator, the Middle East, and western parts of South Asia (Fig. 1). Among these, E. ocellatus (the West African saw-scaled viper) is responsible for most snakebite deaths in sub-Saharan Africa (2), with a case fatality rate of 20% in the absence of antivenom treatment (28), whereas the Indian saw-scaled viper (E. carinatus) is one of the ‘big four’ snake species that together cause the vast majority of India’s 46,000 annual snakebite deaths (5). Envenomings by saw-scaled vipers cause local tissue damage and venom-induced consumption coagulopathy (VICC), the combination of which routinely results in life-threatening internal hemorrhage (29, 30). Crucially, the predominant toxins in saw-scaled viper venoms are typically SVMPs (27.4-75.7% of all venom proteins; Fig. 1) (11, 24), and thus these snakes are tractable models for testing the development of new SVMP-specific small molecule-based snakebite therapeutics. Consequently, in this study we investigated the in vitro and in vivo neutralizing potential of repurposed licensed metal chelators against a variety of saw-scaled viper venoms (genus Echis). We demonstrate that 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonic acid (DMPS), an existing licensed drug indicated for treating chronic and acute heavy metal poisoning, effectively neutralizes venom-induced lethality in vivo and is a promising candidate for translation into a potential pre-hospital treatment for snakebite envenoming.

Fig. 1. The geographical distribution and venom toxin composition of saw-scaled vipers (genus Echis).

Map of saw-scaled viper distribution with the locales of the studied species indicated by red stars. Echis distribution areas and corresponding venom proteomes are highlighted by the following colors: light orange (E. leucogaster), blue (E. ocellatus), green (E. carinatus), pink (E. pyramidum), violet (E. coloratus). Toxin proteome abundances were taken from (11, 58) and generated in this study for E. leucogaster. Toxin family key: SVMP, snake venom metalloproteinase; SVSP, snake venom serine proteinase; PLA2, phospholipase A2; CTL, C-type lectins; LAAO, L-amino acid oxidase; SVMPi, SVMP inhibitors; DIS, disintegrin; CRISP, cysteine-rich secretory protein.

Results

Metal chelators inhibit venom activity in vitro

Saw-scaled viper venoms are highly enriched in SVMPs (45.4-72.5% of all toxins), with the exception of that of E. leucogaster, whose venom proteome is dominated by PLA2s (39.7%; SVMPs 27.4%) (Fig. 1). Because SVMP activity is Zn2+-dependent, we assayed the ability of three metal chelators to inhibit venom SVMPs from six saw-scaled vipers with a wide geographical distribution (Fig. 1), namely E. ocellatus (Nigeria), E. carinatus (U.A.E. and India), E. pyramidum (Kenya), E. leucogaster (Mali), and E. coloratus (Egypt). The three chosen chelators – dimercaprol (British anti-Lewisite), 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonic acid (DMPS, also known as unithiol), and dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA, also known as succimer) – share a common backbone (fig. S1) and are licensed medicines used to treat acute and chronic heavy metal poisoning (31). We also compared the efficacy of these chelators to that of EDTA, a metal chelator that we have previously shown to inhibit the SVMP activity and lethal effects of E. ocellatus venom (24).

We used a kinetic fluorogenic assay to quantify venom SVMP activity and its neutralization by metal chelators. All six Echis venoms displayed similar amounts of SVMP activity (fig. S2A), with slightly higher activity observed for Indian E. carinatus. When testing the neutralization of this activity across a 1000-fold concentration range for the various metal chelators (150 µM to 150 nM), dimercaprol was found to consistently be the most effective (IC50: 0.04-0.18 µM), followed by DMPS≈EDTA (IC50: 1.64-3.40 and 2.25-4.43 µM, respectively) and then DMSA (IC50=19.29-35.09 µM) (Fig. 2, Data file S1). However, all drugs inhibited >98% of venom activity at the maximal concentration tested (150 µM), with dimercaprol, DMPS, and EDTA displaying comparable potency at the 15 µM concentration, irrespective of the snake species tested.

Fig. 2. Metal chelators inhibit SVMP toxin activity of saw-scaled viper venoms.

The neutralizing capability of four metal chelators against the SVMP activity of six Echis venoms. Data are presented for four drug concentrations, from 150 µM to 150 nM (highest to lowest dose), expressed as percentages of the venom-only sample (100%, dotted red line). The negative control is presented as an interval (dotted black lines) and represents the values recorded in the PBS-only samples (expressed as % of venom activity), where the highest and the lowest values for each set of experiments are depicted. Inhibitors are color-coded (dimercaprol, red; DMPS, blue; DMSA, purple; EDTA, dark blue). The data represent triplicate independent repeats with SEMs, where each repeat represents the average of n≥2 technical replicates.

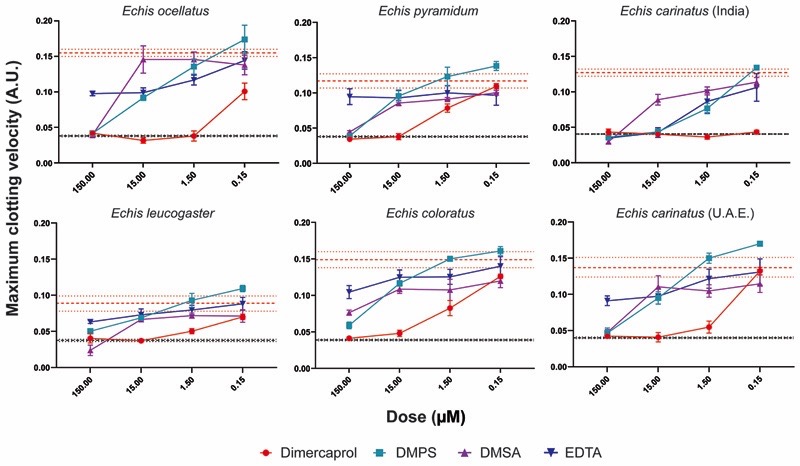

We next tested the inhibitory capacity of the chelators in a venom-induced plasma clotting assay, an in vitro model for in vivo coagulopathy (32). Because all tested Echis venoms are procoagulant (24, 33) and exhibit rapid clotting profiles (fig. S2B), we measured venom neutralization as a shift in these profiles towards that of the plasma-only control. Similar to the SVMP assay, dimercaprol outperformed DMPS and DMSA (IC50: 0.14-1.36, 1.18-27.65, and 18.78-147 µM, respectively). However, all three drugs showed considerable neutralization (60.6-100% inhibition) of the coagulopathic effects of each of the venoms at the maximal inhibitor dose tested (150 µM) (Fig. 3, Data file S1).

Fig. 3. Metal chelators inhibit the procoagulant activity of saw-scaled viper venoms.

The neutralizing capability of four metal chelators against the procoagulant activity of six Echis venoms. Data are presented for four drug concentrations, from 150 µM to 150 nM (highest to lowest dose), expressed as the maximum clotting velocity (middle dotted red line and surrounding interval indicates the maximum clotting velocity of the venom and represents the average ± SEM). The negative control is presented as an interval (dotted black lines, including the average and average ± SEM; this may appear as a single black line if the interval is very narrow and lines overlap) and represents normal plasma clotting. Inhibitors are color-coded (dimercaprol, red; DMPS, blue; DMSA, purple; EDTA, dark blue). The data represent triplicate independent repeats with SEMs, where each repeat represents the average of n≥2 technical replicates.

Except for Indian E. carinatus venom (IC50 = 2.18 µM), EDTA did not extensively inhibit venom activity in the plasma assay due to its proclivity towards calcium, which is added to the citrated plasma in excess as a required cofactor to stimulate clotting. Because five of the six Echis venoms are capable of inducing clotting in a calcium-independent manner (24, 33), we repeated the assay in the absence of calcium and in this scenario, EDTA was effective at inhibiting venom-induced plasma clotting, presumably through effective chelation of Zn2+ in the absence of calcium (fig. S3, Data file S1). Despite this, EDTA was generally outperformed by both dimercaprol and DMPS under these conditions (IC50: 4.89-253.10 versus 0.49-13.98 and 2.18-7.55 µM, respectively).

Saw-scaled viper venoms contain SVMPs that potently activate prothrombin, and therefore contribute to VICC in envenomed patients (24). Given the success of metal chelators in neutralizing procoagulant venom activity in the above assays, we next tested whether they could prevent the cleavage of prothrombin. Recombinant human prothrombin was either preincubated with venom or venom and inhibitor (150 or 500 µM doses of each metal chelator), with prothrombin profiles subsequently examined by SDS-PAGE (fig. S4). All four chelators demonstrated protective effects against each saw-scaled viper venom, with the exception of E. coloratus, at the higher dose, although dimercaprol and EDTA outperformed DMPS and DMSA at the lower dose (150 µM) (fig. S4).

Dimercaprol and DMPS protect against venom-induced lethality

Given the in vitro efficacy of the tested chelators, which generally outperformed EDTA, a drug shown to neutralize the lethal effects of saw-scaled viper venoms in vivo (24), we next investigated whether these compounds could protect against venom-induced lethality in a conventional in vivo model of envenoming. To this end, we used a refined version of the WHO-recommended standard protocol for the preclinical testing of antivenoms (ED50 assay). This assay requires the preincubation of venom and therapy before their intravenous co-administration to mice. Groups of male CD1 mice (n=5) were injected via the tail vein with 2.5 x lethal dose 50 (LD50) of E. ocellatus venom (Nigeria, 45 µg) in the presence or absence of the various chelators (60 μg dose of dimercaprol, DMPS, or DMSA per mouse). We used E. ocellatus as our model because this species has been referred to as the most medically-important snake in West Africa (2). The positive control venom-only group all succumbed to the lethal effects of the venom within the first hour (3-50 min). However, the groups of mice that received dimercaprol or DMPS alongside a lethal dose of venom survived until the end of the experiment (6 h) (Fig. 4A-B). DMSA was found to be less effective, as only three of the five experimental animals survived (Fig. 4C). The metal chelators were also well-tolerated when administered alone (Fig. 4, dotted lines), with no overt signs of toxicity.

Fig. 4. Metal chelators prevent or delay lethality in vivo when preincubated with Echis ocellatus venom.

Kaplan-Meier survival graphs for experimental animals (n=5) receiving venom preincubated (30 min at 37 C) with different metal chelators via the intravenous route. Survival of mice receiving 45 µg of E. ocellatus venom (2.5 × LD50 dose) with and without 60 µg of dimercaprol (A), 60 µg of DMPS (B), or 60 µg of DMSA (C). Drug-only controls are presented as black dotted lines at the top of each graph, and the end of the experiment was at 6 h. None of the drugs exhibited toxicity at the given doses. (D) Quantification of TAT concentrations in envenomed animals. Where the time of death was the same within experimental groups (early deaths or complete survival), TAT concentrations were quantified for n=3, and where times of death varied, n=5. The data are displayed as means of the duplicate technical repeats plus SDs.

We have previously demonstrated that plasma thrombin-antithrombin (TAT) concentrations, a marker of thrombin generation, are a useful biomarker for assessing the efficacy of therapeutics against saw-scaled viper envenoming in experimental animals (24). In the current study, mortality correlated with high TAT concentrations (~1200 ng/ml, R2=0.866, fig. S5), whereas low TAT concentrations (Fig. 4D) were observed in mice where metal-chelators prevented lethality, and these concentrations were comparable to those in non-envenomed control animals (10.2-15.9 ng/ml). In line with our in vitro findings, dimercaprol caused the greatest decrease in TAT concentrations (~40-50 ng/ml), followed by DMPS (~170-252 ng/ml) and then DMSA (~300-666 ng/ml).

Chelator efficacy varies among snake species

We next tested the capability of the two metal chelators that provided complete protection against the lethal effects of E. ocellatus envenoming (dimercaprol and DMPS) at neutralizing venom from related saw-scaled viper species. We chose the next two most medically important Echis species (E. pyramidum from Kenya and E. carinatus from India), each of which has a relatively different venom composition when compared to that of E. ocellatus (Fig. 1, (11, 34)). Whereas both E. pyramidum and E. carinatus venoms remain dominated by SVMPs, they each have higher proportions of C-type lectin toxins (CTLs) (11.2% and 23.9%) and PLA2s (E. pyramidum, 21.5%) or disintegrins (E. carinatus, 14.0%) than E. ocellatus (CTL, 7.1%; PLA2, 10.0%; disintegrins, 2.3%). Neither chelator was found to confer complete protection against both of these venoms when tested in vivo. Dimercaprol provided complete protection against lethality caused by E. carinatus, but was less effective against E. pyramidum (two deaths; 54 and 165 min), whereas DMPS provided complete protection against E. pyramidum, but only partial neutralization against E. carinatus (two deaths; 89 and 110 min) (Fig. 5). TAT concentrations showed a consistent correlation with the survival data, with lethality corresponding to increased TAT concentrations (>322 ng/ml). We found it highly promising that both metal chelators were capable of preventing lethality in mice envenomed with two of the three venoms tested, and that for the third partial protection and significantly prolonged survival times were observed (P=0.0041 for E. carinatus venom-only vs. venom + DMPS; P=0.0037 for E. pyramidum venom-only vs. venom + dimercaprol) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 5. The efficacy of metal chelators against other medically important Echis venoms.

Kaplan-Meier survival graphs for experimental animals (n=5) receiving Echis pyramidum or E. carinatus (India) venom preincubated (30 min at 37 C) with different metal chelators via the intravenous route. Survival of mice receiving 40 µg of E. pyramidum venom (A), and 47.5 µg of E. carinatus (India) venom (both represent the 2.5 × LD50 dose) (B) with or without 60 µg of dimercaprol or DMPS. Drug-only controls are presented as black dotted lines at the top of each graph. None of the drugs exhibited toxicity at the given doses. The end of the experiment was at 6 h after injection. Quantification of TAT concentrations in envenomed animals is displayed in the right panels. Where the time of death was the same within experimental groups (early deaths or complete survival), TAT concentrations were quantified for n=3, and where times of death varied, n=5. The data are displayed as means of the duplicate technical repeats plus SDs.

Delayed drug administration protects against lethality

We initially designed our survival assays in line with the WHO-approved recommendations for the preclinical testing of antivenoms, whereby the preincubation of venom and treatment ensures optimal conditions for the neutralization of venom toxins. To modify this model to better mimic a real-life envenoming scenario, we next challenged groups of mice intraperitoneally with 90 µg (the equivalent of 5 x the intravenous LD50 dose) of E. ocellatus venom, followed by the administration of an intraperitoneal dose (120 μg) of dimercaprol or DMPS 15 minutes later. All experimental animals were then monitored for signs of envenoming for 24 h, along with those from the venom-only and drug-only control groups. None of the animals receiving metal chelators alone displayed any adverse effects over the 24 h period, whereas the venom-only group succumbed to the lethal effects of the venom within 1.5-4 h (Fig. 6A). Notably, the delayed dosing of DMPS protected against venom-induced lethality for over 12 h after initial envenoming, and two of the five experimental animals survived to the end of the experiment (24 h) (Fig. 6A). The observed prolonged protection against envenoming provided by DMPS is promising, and it is worth noting that the death of the three mice between 12.6-24 h post-venom administration is likely due to the substantial clearance of DMPS in the absence of redosing, as previous research in rats and rabbits has shown that 85-89% of this chelator is excreted in the urine within 6 h after oral dosing (35, 36). Contrastingly, the delayed dosing of dimercaprol in E. ocellatus-envenomed mice offered considerably less protection than DMPS. Although two experimental animals also survived until the end of the experiment (24 h), three succumbed rapidly, and at times closely matching those of the venom-only control (111, 125, and 150 min vs. 110, 110, and 143 min, respectively). These findings demonstrate that DMPS outperforms dimercaprol by providing prolonged protection against the lethal effects of E. ocellatus snake envenoming in a preclinical model more reminiscent of a real-world envenoming scenario (treatment delivery after envenoming).

Fig. 6. DMPS delays lethality in vivo in a ‘challenge and treat’ model of envenoming.

Kaplan-Meier survival graphs for experimental animals (n=5) receiving venom (intraperitoneal administration), followed by delayed drug treatment (intraperitoneally 15 min later). (A) Survival of mice receiving 5 x the intravenous LD50 dose of E. ocellatus venom (90 µg) with or without 120 µg of drug (dimercaprol or DMPS) 15 min later. (B) Survival of mice receiving 7 x intravenous LD50 dose of E. pyramidum venom (112 µg) with or without 120 µg of DMPS 15 min later. (C) Survival of mice receiving 5 x intravenous LD50 dose of E. carinatus (India) venom (95 µg) with or without 120 µg of DMPS 15 min later. For (A), (B), and (C), drug-only controls are presented as black dotted lines at the top of each graph (none of the drugs exhibited toxicity at the given doses), and the end of the experiment was at 24 h. (D) Quantification of TAT concentrations in envenomed animals. Where the time of death was the same within experimental groups (early deaths or complete survival), TAT concentrations were quantified for n=3, and where times of death varied, n=5. The data are displayed as means of the duplicate technical repeats plus SDs. EOC, E. ocellatus; EPL, E. pyramidum; ECAR, E. carinatus.

We next investigated whether the delayed administration of DMPS was equally effective against the venoms of E. pyramidum and E. carinatus. In line with our previous findings, DMPS was more effective at protecting against the lethal effects of E. pyramidum venom than those of E. carinatus, despite using a higher venom challenge dose (112 vs. 95 µg, respectively) (Fig. 6B and C). Although three animals died within the first 6 h (at 99, 227, and 365 min) in the E. pyramidum group, two survived for the duration of the experiment (24 h) (Fig. 6B), whereas all mice treated with E. carinatus venom succumbed within the first 6.5 h of the experiment, and thus the chelator only provided a slight delay in lethality compared with the venom-only control (Fig. 6C). TAT concentrations again correlated with lethality, with higher concentrations (>400 ng/ml) observed in animals not protected by DMPS, in contrast to those that survived for the duration of the experiment (average of ~200 ng/ml) (Fig. 6D and fig. S5).

DMPS with subsequent antivenom administration prolongs survival

The results described above demonstrate impressive protective capabilities for a single small molecule (DMPS), when considering that snake venoms consist of mixtures of numerous (50 to >200) constituents. To better support the use of DMPS as a pre-hospital snakebite therapy, we next sought to model a scenario in which metal chelators were administered as a rapid intervention soon after a snakebite, followed by later antivenom therapy when the patient has reached a healthcare facility. Thus, we compared our earlier findings where E. ocellatus venom (90 µg) was administered intraperitoneally followed by DMPS (120 μg) via the same route 15 min later, with mice receiving the same venom and drug regimen, but with the intravenous administration (as per clinical use) of antivenom 1 h after venom injection (45 min after DMPS administration). For this, we used EchiTabG, an ovine antivenom generated against the venom of E. ocellatus and with known preclinical and clinical efficacy (13, 37). In addition, we used two control groups: one that received antivenom intravenously 1 h after venom injection but did not receive DMPS, and another that received antivenom intraperitoneally 15 min after the venom, as a direct comparator for the DMPS dose. A 1 h delay in antivenom administration in the absence of DMPS resulted in the early death of two mice (within the first 4.5 h), which correlated with high TAT concentrations (554 and 728 ng/ml) (Fig. 7A). The antivenom control that was administered intraperitoneally at 15 min, again in the absence of DMPS, resulted in one early death (at 142 min). Thus, delayed delivery of high doses of effective antivenom was unable to provide complete protection against envenoming by E. ocellatus. Notably, the early intraperitoneal administration of DMPS at 15 min after envenoming, followed by the intravenous delivery of antivenom at 1 h, protected against the lethal effects of E. ocellatus venom in all experimental animals until the end of the experiment (24 h), thereby extending the survival times of envenomed animals that received DMPS alone by >11 h (first death at 12.6 h) (Fig. 7B). This treatment regimen was also associated with low TAT concentrations (13.6-23.2 ng/ml), approaching those of the non-envenomed control mice (10.2-15.9 ng/ml; Fig. 7B). In combination, these findings demonstrate that: (i) DMPS outperforms antivenom therapy when administered by the same route after venom delivery, (ii) DMPS outperforms antivenom therapy when delivered earlier, even when the antivenom is delivered intravenously, and (iii) the combination of early DMPS treatment followed by later antivenom administration provides prolonged protection against E. ocellatus venom-induced lethality.

Fig. 7. Oral DMPS followed by later administration of antivenom protects against in vivo lethality caused by Echis ocellatus venom.

Kaplan-Meier survival graphs for experimental animals (n=5) receiving E. ocellatus venom (90 µg, 5 × intravenous LD50 dose, via intraperitoneal administration), followed by delayed drug treatment (intraperitoneal or oral) and/or antivenom (intraperitoneal or intravenous). (A) Survival of mice receiving E. ocellatus venom (intraperitoneally) followed by 168 µl of the E. ocellatus monospecific antivenom EchiTAbG either intraperitoneally 15 min later or intravenously 1 h later. Corresponding TAT concentrations for the envenomed animals are depicted on the right. Note: For the venom + AV intraperitoneally (15 min) dataset, the mouse that succumbed early to the effects of the venom could not be sampled for TAT, therefore the data displayed only reflect the animals that survived until the end of the experiment. (B) Survival of mice receiving E. ocellatus venom (intraperitoneally) followed by DMPS 15 min later (120 µg, intraperitoneally) and antivenom 1 h after venom administration (168 µl, intravenously). Right panel shows corresponding TAT concentrations. (C) Survival of mice receiving E. ocellatus venom (intraperitoneally), followed immediately by: (i) oral DMPS (600 µg, ~1 min after venom injection), (ii) oral DMPS (600 µg, ~1 min after venom injection) and EchiTAbG antivenom (168 µl, intravenously, 1 h later), and (iii) EchiTAbG antivenom (168 µl, intravenously, 1 h later). Right panel shows corresponding TAT concentrations. For all survival experiments, drug- or antivenom-only controls are presented as black dotted lines at the top of each graph (none exhibited toxicity at the given doses), and the end of the experiment was at 24 h. For quantification of TAT, where the time of death was the same within experimental groups (early deaths or complete survival), TAT concentrations were quantified for n=3, and where times of death varied, n=5. The data are displayed as means of the duplicate technical repeats plus SDs.

Oral DMPS followed by antivenom protects against venom lethality

DMPS is formulated both as a solution for injection and as an oral capsule, with the latter making it particularly promising as an early intervention for administration outside of a hospital setting. Next, we investigated the preclinical efficacy of DMPS when dosed via the oral route. DMPS was dissolved into a solution containing molasses, which was then provided to experimental animals ad libitum via a pipette tip 1 min after venom injection (90 µg E. ocellatus venom administered intraperitoneally; 600 μg DMPS orally; n=5). We compared survival outcomes in experimental groups consisting of: (i) venom and molasses (sham) only, (ii) venom and oral DMPS only, (iii) venom, oral DMPS, and then antivenom delivered intravenously 1 h later, and (iv) venom, sham, and the later dose of antivenom (Fig. 7C). The DMPS dose was increased fivefold in these studies (600 μg vs. 120 µg) due to the anticipated lower bioavailability of the oral route compared with the intraperitoneal delivery described earlier. Nonetheless, this dose remained considerably lower than the maximal human equivalent dose permitted over 24 hr (2.44 mg/kg vs. 34.28 mg/kg) or even at a single dosing point (2.44 mg/kg vs 2.86 mg/kg), and the drug itself did not display any signs of toxicity in mice, as evidenced by survival data (Fig. 7C) and behavioral and post-mortem observations. Oral DMPS treatment resulted in comparable survival (2 of 5 experimental animals) to intraperitoneally delivered DMPS at the end of the experiment (24 h), although survival times were noticeably prolonged when the drug was delivered via the intraperitoneal route (Figs. 7B and 7C). These findings suggest that, as perhaps anticipated, the uptake and distribution of DMPS via oral administration are indeed inferior to the intraperitoneal route. In the comparator group, where envenomed mice received sham and antivenom only, only three mice survived to the end of the experiment, with two animals succumbing to the lethal effects of the venom (Fig. 7C). Critically though, the combination of oral DMPS followed by later antivenom administration resulted in the complete survival of experimental animals at 24 h (Fig. 7C), and those animals displayed TAT concentrations highly comparable to those observed in non-envenomed controls (average of 17.3 ng/ml vs. 13.05 ng/ml in the control). These findings demonstrate that the early oral delivery of DMPS is capable of prolonging the survival of envenomed animals, and when combined with a later dose of antivenom, can provide prolonged and complete protection against snakebite lethality in vivo.

DMPS effectively neutralizes venom-induced local hemorrhage and restores red blood cell (RBC) morphology

The findings presented above demonstrate that DMPS protects against lethality and prevents the onset of severe coagulopathy in a variety of preclinical models. Next, we wished to explore the effectiveness of this chelator in preventing other pathological signs caused by saw-scaled viper venoms, specifically venom-induced hemorrhage and toxicity towards RBCs. To investigate the ability of DMPS to neutralize local hemorrhage, we injected groups of three male CD-1 mice intradermally with one minimum hemorrhagic dose (1 MHD [10 µg] (38)) of E. ocellatus venom. We then compared the size of the hemorrhagic lesions formed in the group receiving venom only with those in mice receiving the same dose of venom preincubated with 13.3 µg DMPS (1:1.33 venom to drug ratio, consistent with the lethality experiments). Whereas the venom-only group developed large, distinct, hemorrhagic lesions at 2 h after injection (average size of 41.24 mm2), those receiving the drug exhibited a substantial reduction (p=0.0007) in lesion size (average size of 1.43 mm2), nearly matching the complete absence of lesions observed in the PBS-only control group (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. DMPS effectively neutralizes local hemorrhage caused by E. ocellatus venom.

(A) The resulting murine hemorrhagic lesions observed 2 h after the intradermal injection of (from left to right): (i) 10 µg E. ocellatus venom, (ii) 10 µg E. ocellatus venom preincubated (30 min at 37 C) with 13.3 µg DMPS, (iii) 13.3 µg DMPS, and (iv) PBS control. For all experimental groups, n=3. Black lines represent scale bars equivalent to 2 mm. (B) Quantification of hemorrhagic lesion sizes expressed as the hemorrhagic area (mm2) observed 2 h after injection. The data are expressed as the mean of triplicate measurements ± SEM. A two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to compare the lesion sizes in the venom-only vs. venom+ DMPS groups, and significance is indicated by asterisks (p=0.0007).

We next examined RBC morphology in blood films collected from our earlier intravenous experiments in which mice received E. ocellatus, E. carinatus, or E. pyramidum venom or those venoms preincubated with DMPS. Envenomation correlated with marked echinocytosis (the presence of crenated or ‘burr’ cells) across the three venoms tested, but the intravenous administration of DMPS fully rescued normal RBC morphology in mice treated with E. ocellatus venom (fig. S6). In addition, some protection was also observed against the venoms of E. pyramidum and E. carinatus, and the resulting cell morphology closely matched that observed in control blood samples, although limited intravascular hemolysis marked by ‘ghost cells’ was noted in these cases (fig. S6). When assessing the RBC morphology in blood films sourced from E. ocellatus envenomed mice in which drug administration was delayed, similar findings were observed. The intraperitoneal administration of E. ocellatus venom also resulted in the formation of echinocytes due to the expansion of the outer leaflet of the RBC membrane (fig. S7). Echinocytosis observed following rattlesnake (Crotalus spp.) envenoming was previously associated with the action of PLA2 toxins (39). However, we suspect that SVMPs may be responsible in the case of saw-scaled vipers, as DMPS was unable to inhibit the PLA2 or serine protease activities of fractionated E. ocellatus venom (fig. S8), yet the oral administration of DMPS markedly reduced the number of echinocytes present in the blood films (fig. S7). The delivery of antivenom alone at 1 h after venom delivery also generally rescued this RBC phenotype, though a small number of echinocytes and ghost cells remained present (fig. S7). The combined administration of both DMPS and antivenom resulted in a further reduction in the number of abnormal cells (fig. S7). In combination, these findings demonstrate that the treatment of experimentally envenomed animals with DMPS protects them from venom-induced local hemorrhage and toxicity against RBCs, in addition to preventing coagulopathy and lethality.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that metal chelators can likely be repurposed as effective snakebite therapeutics, particularly when directed against snake venoms rich in metalloproteinases. Chelators have demonstrated safety profiles, are licensed medicines, and show considerable promise as affordable treatments for snakebite in low/middle-income countries (~8-12 USD/100 mg oral capsule versus 48-315 USD per vial of antivenom (8), with 5-10 vials often required per envenoming). Moreover, the doses at which these SVMP inhibitors show efficacy are >100-fold lower than current immunoglobulin-based treatments (60 µg of drug versus 7.5 mg of antivenom for intravenous administration used in this study). The combination of these characteristics makes them highly amenable for investigation for clinical use in a pre-hospital setting, thus potentially dramatically reducing the long time to treatment typically observed after snakebite, which has a known major detrimental impact on patient outcomes (40, 41).

Among the metal chelators explored in this study, DMPS, a hydrophilic heavy-metal chelator, was effective in preventing lethality in vivo in an intravenous model of snakebite envenoming, as well as in prolonging survival in mouse models where the venom challenge was followed by a delayed administration of the drug. Our challenge and treatment model attempted to replicate a clinical situation in which a victim would be bitten, would subsequently receive the metal chelator soon after, and would be later admitted to a healthcare facility where they would be treated with antivenom (if required). In both of our models (venom intraperitoneally/DMPS intraperitoneally or venom intraperitoneally/DMPS orally), the delayed administration of DMPS resulted in prolonged animal survival of ~17 h and ~10 h compared to the venom-only controls for the intraperitoneal and oral dosing, respectively. Moreover, when DMPS administration was followed by an intravenous dose of antivenom 1 h later, complete survival at 24 h after envenoming was observed in all cases, irrespective of whether the drug was delivered intraperitoneally or orally. These findings demonstrate that rapid DMPS intervention can substantially delay the onset of venom lethality, whereas antivenom administration alone (either intraperitoneally as a drug-matched control or intravenously with a 1 h delay) was insufficient to fully neutralize venom activity. In addition to providing protection against lethality, we found that DMPS restored parameters indicative of normal coagulation, protected against damage to RBCs in both the preincubation and delayed administration models, and effectively prevented the formation of localized hemorrhagic lesions in a morbidity model of snakebite envenoming. These results highlight not only the promise of DMPS as a systemic intervention against envenoming, but also as a potential candidate drug for preventing local tissue damage after snakebite.

DMPS is approved in Germany for treating mercury intoxication (marketed as Dimaval) and is available as both a 100-mg capsule for oral dosing and a 250-mg ampoule for intravenous or intramuscular administration. In humans, DMPS is readily absorbed after oral administration, can be detected in the plasma 30-45 min after administration, and reaches peak plasma concentrations 3-4 h after ingestion (42), making it a strong candidate as an early, pre-hospital, therapeutic intervention. Moreover, the drug forms complexes with plasma proteins via disulfide linkages, which results in slow release and prolongation of its clinical half-life to ~20 h, thus extending its efficacy window (43). DMPS also appears to exhibit high specificity for zinc, as previous preclinical research performed in rabbits and dogs showed no significant changes in the concentrations of iron or calcium, despite the intravenous or oral administration of the drug for prolonged periods (50-315/mg/kg/week for 10-26 weeks (44, 45). Importantly, no major side effects or teratogenic effects have been reported (46, 47), even with repeated oral administration spanning months in animals (126 mg/kg/day in rats for 5 days/week for 66 weeks (46); 45 mg/kg/day over 6 months in beagles (45)) or several days in humans (~15 g DMPS given as a mixed regimen parenterally and orally over 12 days (48)). In our study, we used a single therapeutic dose that scales up to 1/14th of the maximal daily oral human equivalent dose regimen for acute heavy metal intoxication (2.44 mg/kg vs. 34.28 mg/kg). However, even under these sub-maximal and single dose conditions, DMPS prolonged survival for at least 12 h in mice envenomed with E. ocellatus venom, suggesting that the drug can effectively counteract systemic venom toxicity within a defined therapeutic window. Its efficacy in the intraperitoneal model superseded that of oral administration, likely due to increased bioavailability and distribution, whereas its decrease in efficacy over time (>12 h) seems likely to be linked to its excretion in the urine. Previous studies in rats and rabbits indicate that >85% of the drug is eliminated during the first 6 h (35, 36), as opposed to the ~20 h half-life observed in humans. Considering that in our model the drug was only administered once, we hypothesize that repeated dosing may continue to effectively neutralize venom SVMPs, thus expanding the protective interval. This should be explored in future studies.

Of the remaining metal chelators tested in this study, dimercaprol showed some early promise as a snakebite therapeutic. Dimercaprol chelates a variety of heavy metals, including lead, arsenic, gold, and mercury, and provided the most effective venom inhibition in vitro. This chelator also neutralized the lethal effects of E. ocellatus and E. carinatus venoms in vivo in the coincubation model, although it had no efficacy in the more clinically-relevant ‘challenge and treat’ preclinical model. In addition, dimercaprol comes with several challenges for clinical use (49), including its formulation in peanut oil, requirement for administration via a deep, painful intramuscular injection, a number of reported adverse reactions, and a small safety margin (50). Given these considerations, its more hydrophilic derivatives offer safer alternatives. Consequently, both DMSA and DMPS have been advocated as the drugs of choice for the contemporary treatment of heavy metal poisoning (27). Our results here, however, demonstrate that DMSA shows a lack of preclinical efficacy against the medically important snake venoms investigated, thus strongly justifying the selection of DMPS as our lead chelator for future clinical translation.

The WHO-recommended protocol for testing snakebite therapies recommends the preincubation of venom with antivenom, which artificially promotes the binding of venom toxins with the therapy. Although this is a necessary first step in assessing the therapeutic potential of a treatment by providing a ‘best-case’ scenario, this method does not accurately reflect snakebite, where venom is delivered before treatment. To overcome this, we used an intraperitoneal challenge/treatment model whereby the treatment was administered after venom, mirroring a more realistic scenario. However, no in vivo mouse model, regardless of venom or drug dosage, route of administration, or time between venom injection and drug treatment, can ever fully reflect a human snakebite. This is because the venom dose in mice is usually high (45-112 µg) to induce rapid lethality (<4 h) and avoid prolonged suffering in experimental animals. In contrast, lethality from saw-scaled viper bites in humans does not typically occur in <12 h (29). Thus, the onset of pathology is much faster in the animal model, and drug uptake and pharmacokinetics will likely differ due to different circulatory volumes. Nevertheless, the current model is still highly useful in evaluating antivenom efficacy and is the best preclinical model available for assessing potential therapeutic interventions for snakebite. Furthermore, snake venoms are toxin cocktails (10), and their toxin composition can vary extensively among species (11). It is worth noting that DMPS displayed superior efficacy against the venoms of E. ocellatus and E. pyramidum, compared with the venom of the related species E. carinatus, when used as a solo therapy. Nevertheless, DMPS did offer some protection against E. carinatus venom and prolonged survival in experimental animals. These differences in efficacy likely reflect variation in the toxin constituents found in the venom of these species (Fig. 1, (11, 34)), because a similar lack of preclinical efficacy has been observed when using antivenom made against E. ocellatus to neutralize E. carinatus venom (13) and, conversely, the clinical use of E. carinatus antivenom for treating bites by E. ocellatus has resulted in poor patient outcomes (51, 52). Despite these limitations, we suggest that DMPS may be a useful early intervention therapeutic to delay the onset of snakebite pathology caused by a variety of SVMP-rich venoms, particularly when subsequently coupled with species-specific antivenom. Future work should explore the breadth of DMPS efficacy in combination with antivenom, specifically to assess whether this combination therapy approach may reduce the number of costly vials of antivenom that are currently required to effect cure after snakebite.

Lastly, although we have shown here that DMPS is effective in counteracting the activity of SVMP toxins, it cannot neutralize other toxin classes, such as the enzymatically active serine proteases and PLA2s also found in E. ocellatus venom. Thus, although oral DMPS may prove to be an effective early intervention for delaying the onset of pathology caused by many viperid snakes, which typically have a high abundance of SVMPs in their venom (21), snakebite victims may still require immediate transport to a healthcare facility in case antivenom therapy is required to neutralize other pathogenic, or even potentially lethal, toxin constituents. Future treatments consisting of mixtures of small molecules, each targeting different toxin types, could prove particularly valuable as more generic drugs against viper venoms, particularly since such inhibitors with specificities towards different toxin types have recently been described (15, 53). In addition, the further combination of small molecule inhibitors with conventional or next-generation recombinant human/humanized oligoclonal antivenoms (54) may represent a particularly promising treatment strategy, particularly because this is an actively developing field aimed at generating safer and more effective snakebite therapeutics.

Despite these described limitations, DMPS remains a strong candidate for translation for clinical use in snakebite envenoming. Given its high tolerability and availability of an oral formulation, DMPS is highly suitable for repurposing for treating snakebite, particularly against bites by the West African saw-scaled viper E. ocellatus, when considering the preclinical efficacy observed here. This species is an ideal choice for testing the clinical utility of DMPS, because it is responsible for thousands of deaths in Africa every year (2). We envision the implementation of a Phase 2 clinical trial in which snakebite victims would be given DMPS as an immediate pre-hospital intervention followed later by antivenom upon arrival at a healthcare facility, compared with a second arm of the trial receiving conventional antivenom therapy only. However, first it will be important to undertake a Phase 1 trial to identify an optimal dosing regimen for DMPS within an African population, which is necessary because snakebite is an acute event, and thus the optimal bioavailability is likely to differ from that of the current clinical indication of heavy metal poisoning, where frequent dosing can be repeated for several weeks. Collectively, our data demonstrate that repurposing of inexpensive metal chelators can protect against the lethal effects of envenoming by snakes with SVMP-rich venoms. Although antivenom may be required secondarily, DMPS seems likely to delay the onset of severe envenoming by these snakes and may facilitate a reduction in the dose of costly and poorly tolerated antivenom. Ultimately these findings advocate for further research into the utility of small molecule inhibitors for rapidly and generically treating the world’s most lethal neglected tropical disease.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The study used a variety of in vitro and in vivo assays to determine the efficacy of metal chelators against snakebite. For all in vitro kinetic experiments testing the dose-efficacy of chelators, the assays were performed in at least triplicate and each experimental repeat consisted of technical duplicates or triplicates. For the animal lethality studies, experiments were performed on groups of five male CD-1 mice (18-20 g). We first followed a modified version of the established WHO protocol (55) for testing intravenous treatment efficacy in a preincubation model of envenoming. Subsequently, we developed an intraperitoneal delivery-based ‘challenge and treat’ model of envenoming to explore venom neutralisation with delayed drug administration. For the hemorrhagic lesion studies, venom and/or drug was delivered intradermally into groups of three male CD-1 mice (18-20 g). For all animal experiments, mice were randomly distributed across groups, and the experimenters assessing the outcomes were blinded to the intervention. Mouse blood samples were collected from experimental animals via cardiac puncture after euthanasia by rising concentrations of CO2. Resulting plasma samples were assessed for markers of coagulopathy in duplicate using commercial ELISA kits, with 3 to 5 mice being sampled. The numbers for all biological repeats are given in the respective figure legends. Detailed descriptions of all of the Materials and Methods used in this study are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

In vivo studies

All animal experiments were conducted using protocols approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Boards of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and the University of Liverpool, and performed in specific pathogen-free conditions under licensed approval of the UK Home Office and in accordance with the Animal [Scientific Procedures] Act 1986 and institutional guidance on animal care. All animals were housed in groups of 5 with water and food ad libitum. Experimental design was based upon refined WHO-recommended protocols (8, 55), with the observers being blinded to the experimental groups. The median lethal dose (venom LD50) for E. ocellatus (Nigeria), E. carinatus (India) and E. pyramidum (Kenya) venoms (18, 19, and 16 µg per 20 g mouse, respectively) were previously determined (8, 24, 55). Drug stocks were freshly prepared as follows: DMPS (1 mg/ml in PBS), DMSA (2 mg/ml in ethanol; final ethanol concentration of 15%), and Dimercaprol (1 mg/ml in water).

Coincubation model of preclinical efficacy

For our initial experiments, we used 2.5 x the intravenous LD50 doses of E. ocellatus (45 µg), E. carinatus (India) (47.5 µg), and E. pyramidum venoms (40 µg) in a refined version of the WHO recommended (55) antivenom ED50 neutralization experiments (24). Groups of five male 18-22 g CD-1 mice (Charles River) received experimental doses that consisted of either (a) venom only (2.5 x LD50 dose); (b) venom and drug (60 µg); or (c) drug only (60 µg). All experimental doses were prepared to a volume of 200 µl in PBS and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min before intravenous injection via the tail vein. Animals were monitored for 6 h and euthanized upon observation of humane endpoints (seizure, pulmonary distress, paralysis, hemorrhage). Deaths, times of death, and survivors were recorded, where “deaths/times of death” actually represent the implementation of euthanasia via rising concentrations of CO2 based on the defined humane endpoints.

Challenge and treatment model of preclinical efficacy

Next, we performed experiments where mice were initially challenged with venom, followed by delayed administration of the drug or antivenom. For these studies, we used an intraperitoneal model of venom administration to provide an acceptable time window to measure venom neutralization. Consequently, the venom challenge doses were increased to 5 x the intravenous LD50s (E. ocellatus [90 µg] and E. carinatus India [95 µg]) or 7 x the intravenous LD50s (E. pyramidum leakeyi [112 µg]) to ensure that complete lethality in the venom-only control group occurred within 4-5 h. Groups of five male 18-22 g CD-1 mice (Charles River) were injected with venom (100 µl final volume), followed by a drug dose that was scaled up in line with the increases in venom challenge doses (120 µg + PBS up to 200 µl) after 15 min. The experimental groups included mice receiving: (a) venom only (5 x intravenous LD50 or 7 x intravenous LD50) + 200 µl PBS (15 min later); (b) venom (5 x intravenous LD50 or 7 x intravenous LD50) + drug (120 µg, 15 min later); and (c) sham (100 µl PBS) + drug (120 µg, 15 min later).

For later ‘challenge and treat’ experiments with E. ocellatus venom only, we also explored the efficacy of antivenom, both with and without drug treatment. The antivenom used was EchiTAbG (MicroPharm Limited, batch EOG001330), an ovine monospecific anti-E. ocellatus antivenom validated for preclinical and clinical efficacy against envenoming by this species (13, 37). The median effective dose (ED50) of EchiTAbG (Micropharm) against 5 x LD50 E. ocellatus (intravenous LD50 of 12.43 µg/mouse) venom was previously determined to be 58.46 µl (13). Consequently, we scaled up the antivenom dose to a dose that would protect all envenomed animals (2 x ED50; 168 µl), taking into account the slight difference in LD50 of our current E. ocellatus venom batch (17.85 µg/mouse vs. 12.43 µg/mouse). Antivenom was administered either intravenously 1 h after venom injection or intraperitoneally as a drug-matched control after 15 min. The experimental design followed that described above with the following experimental groups: (a) E. ocellatus venom (90 µg; 5 x intravenous LD50) + drug (120 µg, 15 min later) + antivenom (intravenously 1 h later, 168 µl); (b) E. ocellatus venom (90 µg; 5 x LD50) + antivenom (intravenously, 1 h later, 168 µl); (c) E. ocellatus venom (5 x intravenous LD50) + antivenom (intraperitoneally 15 min later, 168 µl). For both sets of experiments described above, experimental animals were monitored for 24 h and euthanized upon observation of humane endpoints as described above. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests in GraphPad Prism 8.1 (GraphPad Software) were used to compare the survival times between groups treated with venom alone and venom + drug for E. carinatus and E. pyramidum venoms.

Challenge and treatment model using oral DMPS

We assessed the utility of DMPS as an oral therapeutic, using a similar ‘challenge and treat’ approach. We injected groups of mice intraperitoneally with 5 x intravenous LD50s of E. ocellatus venom, followed immediately (~1 min) by an oral dose of DMPS (600 µg, a dose lower than the human equivalent dose (56) [2.44 mg/kg vs. 34.28 mg/kg maximal daily dose permitted, or 2.44 mg/kg vs 2.86 mg/kg every 2 h]). The drug was dissolved in 50 µl of ~50 mg/ml molasses and administered orally (ad libitum) via a pipette tip to groups of 5 male CD-1 mice. The experimental groups included: (a) venom (90 µg) + molasses; (b) venom (90 µg) + oral DMPS (600 µg); (c) venom (90 µg) + oral DMPS (600 µg) + antivenom (intravenously, 1 h later, 168 µl); (d) venom (90 µg) + molasses + antivenom (intravenously, 1 h later, 168 µl). Animals were monitored for 24 h and euthanized upon observation of humane endpoints, as described above.

Neutralization of local hemorrhage by DMPS

To assess the efficacy of DMPS against the local hemorrhagic effects of E. ocellatus venom, we used a variation of the minimum hemorrhagic dose (MHD) model (55). We used the previously determined MHD dose of E. ocellatus venom (10 µg, (38)) to induce hemorrhagic lesions via intradermal injection (50 µl) into the shaved dorsal skin of briefly anesthetized (isoflurane) male 18-22g CD-1 mice (n=3, Charles River). To assess the ability of DMPS to neutralize hemorrhage, the following experimental groups were used: (a) E. ocellatus venom only (10 µg); (b) DMPS only (13.3 µg); (c) E. ocellatus venom (10 µg) preincubated with DMPS (13.3 µg) (1:1.33 ratio matched to the lethality experiments described earlier); (d) PBS control. All samples were preincubated at 37 ºC for 30 min before injection. Following previous recommendations (38), we implemented a humane reduction in the experimental time frame of this assay from 24 h to 2 h, because in the venom-only control group, venom injection resulted in a clearly measurable hemorrhagic lesion of ~8 mm in diameter after 2 h. The animals were continuously monitored for 2 h, after which they were euthanized via rising concentrations of CO2. Resulting hemorrhagic lesions were excised, measured in two directions using electronic calipers, and digitally photographed alongside color standards (57).

Statistical analysis

The areas under the curve for kinetic data (n=3) and the maximum clotting velocity data were plotted with SEMs. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests were performed in GraphPad Prism 8.1 (GraphPad Software) and used to statistically compare the survival times between groups treated with venom alone and venom + drug for both E. carinatus and E. pyramidum, and to estimate the significance of the reduction in lesion size observed in the MHD model. For all ELISA measurements, the biological replicates were plotted with SDs.

Supplementary Material

One Sentence Summary.

DMPS, a drug licensed to treat mercury poisoning, is preclinically effective as an oral therapeutic for treating certain hemotoxic snakebites.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Rowley for maintenance and husbandry of the snake collection at LSTM and for performing venom extractions. We also thank Joshua Longbottom for his help with distribution mapping and Michael Abouyannis for helpful discussions about therapeutic use of metal chelators.

Funding

This study was funded by: (i) a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship to N.R.C. (200517/Z/16/Z) jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and Royal Society, (ii) a UK Medical Research Council funded Confidence in Concept Award (MC_PC_15040) to R.A.H. and N.R.C. and (iii) a UK Medical Research Council funded Research Grant (MR/S00016X/1) to N.R.C. and R.A.H.

Footnotes

Author contributions: L-O.A., J.K. and N.R.C designed the study. L-O.A. and M.S.H. performed in vitro tests. J.J.C. performed proteomics on E. leucogaster venom. M.C.W. performed fractionation of E. ocellatus venom. S.A., J.A., E.C., R.A.H. and N.R.C. performed the in vivo research. C.E. analyzed mouse blood films. L-O.A. wrote the manuscript with input from J.K. and N.R.C.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

References and Notes

- 1.Gutiérrez JM, Calvete JJ, Habib AG, Harrison RA, Williams DJ, Warrell DA. Snakebite envenoming. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.79. 17063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Habib AG, Kuznik A, Hamza M, Abdullahi MI, Chedi BA, Chippaux J-P, Warrell DA. Snakebite is Under Appreciated: Appraisal of Burden from West Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison RA, Hargreaves A, Wagstaff SC, Faragher B, Lalloo DG. Snake envenoming: A disease of poverty. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longbottom J, Shearer FM, Devine M, Alcoba G, Chappuis F, Weiss DJ, Ray SE, Ray N, Warrell DA, Ruiz de Castañeda R, Williams DJ, et al. Vulnerability to snakebite envenoming: a global mapping of hotspots. Lancet (London, England) 2018;392:673–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31224-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohapatra B, Warrell DA, Suraweera W, Bhatia P, Dhingra N, Jotkar RM, Rodriguez PS, Mishra K, Whitaker R, Jha P, for the Collaborators M. D. S Snakebite Mortality in India: A Nationally Representative Mortality Survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams DJ, Gutiérrez J-M, Calvete JJ, Wüster W, Ratanabanangkoon K, Paiva O, Brown NI, Casewell NR, Harrison RA, Rowley PD, O’Shea M, et al. Ending the drought: New strategies for improving the flow of affordable, effective antivenoms in Asia and Africa. J Proteomics. 2011;74:1735–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khosrojerdi H, Amini M. Acute and Delayed Stress Symptoms Following Snakebite. Mashhad Univ Med Sci. 2013;2:140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison RA, Oluoch GO, Ainsworth S, Alsolaiss J, Bolton F, Arias A-S, Gutiérrez J-M, Rowley P, Kalya S, Ozwara H, Casewell NR. Preclinical antivenom-efficacy testing reveals potentially disturbing deficiencies of snakebite treatment capability in East Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams DJ, Faiz MA, Abela-Ridder B, Ainsworth S, Bulfone TC, Nickerson AD, Habib AG, Junghanss T, Fan HW, Turner M, Harrison RA, et al. Strategy for a globally coordinated response to a priority neglected tropical disease: Snakebite envenoming. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casewell NR, Wüster W, Vonk FJ, Harrison RA, Fry BG. Complex cocktails: the evolutionary novelty of venoms. Trends Ecol Evol. 2013;28:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casewell NR, Wagstaff SC, Wuster W, Cook DAN, Bolton FMS, King SI, Pla D, Sanz L, Calvete JJ, Harrison RA. Medically important differences in snake venom composition are dictated by distinct postgenomic mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:9205–9210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405484111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chippaux JP, Williams V, White J. Snake venom variability: methods of study, results and interpretation. Toxicon. 1991;29:1279–303. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(91)90116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casewell NR, Cook DAN, Wagstaff SC, Nasidi A, Durfa N, Wüster W, Harrison RA. Pre-Clinical Assays Predict Pan-African Echis Viper Efficacy for a Species-Specific Antivenom. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Silva HA, Pathmeswaran A, Ranasinha CD, Jayamanne S, Samarakoon SB, Hittharage A, Kalupahana R, Ratnatilaka GA, Uluwatthage W, Aronson JK, Armitage JM, et al. Low-Dose Adrenaline, Promethazine, and Hydrocortisone in the Prevention of Acute Adverse Reactions to Antivenom following Snakebite: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulfone TC, Samuel SP, Bickler PE, Lewin MR. Developing Small Molecule Therapeutics for the Initial and Adjunctive Treatment of Snakebite. J Trop Med. 2018;2018:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2018/4320175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewin M, Gilliam L, Gilliam J, Samuel S, Bulfone T, Bickler P, Gutiérrez J. Delayed LY333013 (Oral) and LY315920 (Intravenous) Reverse Severe Neurotoxicity and Rescue Juvenile Pigs from Lethal Doses of Micrurus fulvius (Eastern Coral Snake) Venom. Toxins (Basel) 2018;10:479. doi: 10.3390/toxins10110479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewin M, Gutiérrez J, Samuel S, Herrera M, Bryan-Quirós W, Lomonte B, Bickler P, Bulfone T, Williams D. Delayed Oral LY333013 Rescues Mice from Highly Neurotoxic, Lethal Doses of Papuan Taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) Venom. Toxins (Basel) 2018;10:380. doi: 10.3390/toxins10100380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Zhang J, Zhang D, Xiao H, Xiong S, Huang C. Exploration of the Inhibitory Potential of Varespladib for Snakebite Envenomation. Molecules. 2018;23:391. doi: 10.3390/molecules23020391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeda S, Takeya H, Iwanaga S. Snake venom metalloproteinases: Structure, function and relevance to the mammalian ADAM/ADAMTS family proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta - Proteins Proteomics. 2012;1824:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kini R, Koh C, Kini RM, Koh CY. Metalloproteases Affecting Blood Coagulation, Fibrinolysis and Platelet Aggregation from Snake Venoms: Definition and Nomenclature of Interaction Sites. Toxins (Basel) 2016;8:284. doi: 10.3390/toxins8100284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tasoulis T, Isbister GK. A Review and Database of Snake Venom Proteomes. Toxins (Basel) 2017;9:290. doi: 10.3390/toxins9090290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arias AS, Rucavado A, Gutiérrez JM. Peptidomimetic hydroxamate metalloproteinase inhibitors abrogate local and systemic toxicity induced by Echis ocellatus (saw-scaled) snake venom. Toxicon. 2017;132:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rucavado A, Escalante T, Franceschi A, Chaves F, León G, Cury Y, Ovadia M, Gutiérrez JM. Inhibition of local hemorrhage and dermonecrosis induced by Bothrops asper snake venom: effectiveness of early in situ administration of the peptidomimetic metalloproteinase inhibitor batimastat and the chelating agent CaNa2EDTA. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:313–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ainsworth S, Slagboom J, Alomran N, Pla D, Alhamdi Y, King SI, Bolton FMS, Gutiérrez JM, Vonk FJ, Toh C-H, Calvete JJ, et al. The paraspecific neutralisation of snake venom induced coagulopathy by antivenoms. Commun Biol. 2018;1:34. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0039-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howes JM, Theakston RDG, Laing GD. Neutralization of the haemorrhagic activities of viperine snake venoms and venom metalloproteinases using synthetic peptide inhibitors and chelators. Toxicon. 2007;49:734–739. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanjaraj Urs AN, Yariswamy M, Ramakrishnan C, Joshi V, Suvilesh KN, Savitha MN, Velmurugan D, Vishwanath BS. Inhibitory potential of three zinc chelating agents against the proteolytic, hemorrhagic, and myotoxic activities of Echis carinatus venom. Toxicon. 2015;93:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.11.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flora SJS, Pachauri V. Chelation in metal intoxication. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:2745–2788. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7072745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pugh RNH, Theakston RDG. Incidence and mortality of snakebite in savanna Nigeria. Lancet. 1980;316:1181–1183. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92608-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warrell DA, Davidson NMcD, Greenwood BM, Ormerod LD, Pope HM, Watkins BJ, Prentice CR. Poisoning by bites of the saw-scaled or carpet viper (Echis carinatus) in Nigeria. Q J Med. 1977;46:33–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartholdi D, Selic C, Meier J, Jung H. Viper snakebite causing symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage. J Neurol. 2004;251:889–891. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosnett MJ. The Role of Chelation in the Treatment of Arsenic and Mercury Poisoning. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:347–354. doi: 10.1007/s13181-013-0344-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Still K, Nandlal R, Slagboom J, Somsen G, Casewell N, Kool J, Still KBM, Nandlal RSS, Slagboom J, Somsen GW, Casewell NR, et al. Multipurpose HTS Coagulation Analysis: Assay Development and Assessment of Coagulopathic Snake Venoms. Toxins (Basel) 2017;9:382. doi: 10.3390/toxins9120382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogalski A, Soerensen C, Op den Brouw B, Lister C, Dashevsky D, Arbuckle K, Gloria A, Zdenek CN, Casewell NR, Gutiérrez JM, Wüster W, et al. Differential procoagulant effects of saw-scaled viper (Serpentes: Viperidae: Echis) snake venoms on human plasma and the narrow taxonomic ranges of antivenom efficacies. Toxicol Lett. 2017;280:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2017.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casewell NR, Harrison RA, Wüster W, Wagstaff SC. Comparative venom gland transcriptome surveys of the saw-scaled vipers (Viperidae: Echis) reveal substantial intra-family gene diversity and novel venom transcripts. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:564. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabard B. Distribution and excretion of the mercury chelating agent sodium 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulfonate in the rat. Arch Toxicol. 1978;39:289–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00296388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luganskii NI, Loboda II. Conversion of unithiol in the organism. Farmakol Toksikol. 1960;23:349–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abubakar IS, Abubakar SB, Habib AG, Nasidi A, Durfa N, Yusuf PO, Larnyang S, Garnvwa J, Sokomba E, Salako L, Theakston RDG, et al. Randomised Controlled Double-Blind Non-Inferiority Trial of Two Antivenoms for Saw-Scaled or Carpet Viper (Echis ocellatus) Envenoming in Nigeria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook DAN, Owen T, Wagstaff SC, Kinne J, Wernery U, Harrison RA. Analysis of camelid antibodies for antivenom development: Neutralisation of venom-induced pathology. Toxicon. 2010;56:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walton RM, Brown DE, Hamar DW, Meador VP, Horn JW, Thrall MA. Mechanisms of echinocytosis induced by Crotalus atrox venom. Vet Pathol. 1997;34:442–9. doi: 10.1177/030098589703400508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abubakar SB, Habib AG, Mathew J. Amputation and disability following snakebite in Nigeria. Trop Doct. 2010;40:114–116. doi: 10.1258/td.2009.090266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma SK, Chappuis F, Jha N, Bovier PA, Loutan L, Koirala S. Impact of snake bites and determinants of fatal outcomes in southeastern Nepal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:234–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maiorino RM, Dart RC, Carter DE, Aposhian HV. Determination and metabolism of dithiol chelating agents. XII. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of sodium 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulfonate in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;259:808–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maiorino RM, Xu ZF, Aposhian HV. Determination and metabolism of dithiol chelating agents. XVII. In humans, sodium 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonate is bound to plasma albumin via mixed disulfide formation and is found in the urine as cyclic polymeric disulfides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:375–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hrdina R, Gersl V, Vávrová J, Holecková M, Palicka V, Voglová J, Mazurová Y, Bajgar J. Myocardial elements content and cardiac function after repeated i.v. administration of DMPS in rabbits. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1998;17:221–4. doi: 10.1177/096032719801700404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szinicz L, Wiedemann P, Häring H, Weger N. Effects of repeated treatment with sodium 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulfonate in beagle dogs. Arzneimittelforschung. 1983;33:818–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Planas-Bohne F, Gabard B, Schäffer EH. Toxicological studies on sodium 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulfonate in the rat. Arzneimittelforschung. 1980;30:1291–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Domingo JL, Ortega A, Bosque MA, Corbella J. Evaluation of the developmental effects on mice after prenatal, or pre- and postnatal exposure to 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulfonic acid (DMPS) Life Sci. 1990;46:1287–92. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90361-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heinrich-Ramm R, Schaller K, Horn J, Angerer J. Arsenic species excretion after dimercaptopropanesulfonic acid (DMPS) treatment of an acute arsenic trioxide poisoning. Arch Toxicol. 2003;77:63–68. doi: 10.1007/s00204-002-0413-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aaseth J, Skaug MA, Cao Y, Andersen O. Chelation in metal intoxication-Principles and paradigms. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015;31:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. AHFS drug information 2010. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; Bethesda, MD: 2010. https://www.worldcat.org/title/ahfs-drug-information-2010/oclc/609401493. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alirol E, Lechevalier P, Zamatto F, Chappuis F, Alcoba G, Potet J. Antivenoms for Snakebite Envenoming: What Is in the Research Pipeline? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Visser LE, Kyei-Faried S, Belcher DW, Geelhoed DW, van Leeuwen JS, van Roosmalen J. Failure of a new antivenom to treat Echis ocellatus snake bite in rural Ghana: the importance of quality surveillance. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Albulescu L-O, Kazandjian T, Slagboom J, Bruyneel B, Ainsworth S, AlSolaiss J, Wagstaff SC, Whiteley G, Harrison RA, Ulens C, Kool J, et al. A decoy-receptor approach using nicotinic acetylcholine receptor mimics reveals their potential as novel therapeutics against neurotoxic snakebite. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:848. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kini R, Sidhu S, Laustsen A. Biosynthetic Oligoclonal Antivenom (BOA) for Snakebite and Next-Generation Treatments for Snakebite Victims. Toxins (Basel) 2018;10:534. doi: 10.3390/toxins10120534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Theakston RD, Reid HA. Development of simple standard assay procedures for the characterization of snake venom. Bull World Health Organ. 1983;61:949–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nair A, Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin Pharm. 2016;7:27. doi: 10.4103/0976-0105.177703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jenkins TP, Sánchez A, Segura Á, Vargas M, Herrera M, Stewart TK, León G, Gutiérrez JM. An improved technique for the assessment of venom-induced haemorrhage in a murine model. Toxicon. 2017;139:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patra A, Kalita B, Chanda A, Mukherjee AK. Proteomics and antivenomics of Echis carinatus carinatus venom: Correlation with pharmacological properties and pathophysiology of envenomation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17227-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calvete JJ, Cid P, Sanz L, Segura Á, Villalta M, Herrera M, León G, Harrison R, Durfa N, Nasidi A, Theakston RDG, et al. Antivenomic Assessment of the Immunological Reactivity of EchiTAb-Plus-ICP, an Antivenom for the Treatment of Snakebite Envenoming in Sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:1194–1201. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eichberg S, Sanz L, Calvete JJ, Pla D. Constructing comprehensive venom proteome reference maps for integrative venomics. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2015;12:557–573. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2015.1073590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sevenet PO, Depasse F. Clot waveform analysis: Where do we stand in 2017? Int J Lab Hematol. 2017;39:561–568. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.