Summary

Embryo single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) can resolve the transcriptional landscape of development at unprecedented resolution. To date, mammalian embryo scRNA-seq studies have focused exclusively on eutherian species. Analysis of other mammalian outgroups has the potential to identify deeply-conserved lineage specification and pluripotency factors, and can enlighten our understanding of X-dosage compensation. Metatherian (marsupial) mammals diverged from eutherians 160 million years ago. They exhibit distinctive developmental features, including late implantation1 and imprinted X-chromosome inactivation (XCI)2, associated with expression of the Xist-like non-coding RNA RSX 3. Here we perform the first scRNA-seq analysis of embryogenesis and XCI in a metatherian, the grey short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica. We resolve the developmental trajectory and transcriptional signatures of the epiblast (EPI), primitive endoderm (PrE) and trophectoderm (TE), and identify deeply-conserved lineage-specific markers that pre-date the eutherian-metatherian divergence. RSX-coating and inactivation of the X chromosome occurs early and rapidly. This observation supports the hypothesis that imprinted XCI prevents biallelic X-silencing in organisms with early XCI. We identify XSR, an RSX-antisense transcript expressed from the active X chromosome, as the first candidate regulator of imprinted XCI. Our datasets provide unique insights into the evolution of mammalian embryogenesis and X-dosage compensation.

Introduction

Metatherians are a powerful comparative model system with which to understand mammalian biology. Studies on metatherians have provided insights into genome and transcriptome evolution, genomic imprinting, sex determination, neuroregeneration and carcinogenesis4–7. Metatherians exhibit several distinctive properties, most notably during embryogenesis1. Gestation is shorter and the preimplantation period longer than in eutherians. As a result, the placenta is highly transient and young are born in an altricial state, completing their development ex utero during an extended period of lactation. Unlike eutherians, metatherians do not form a morula. Instead, blastomeres divide and expand from the embryonic pole in close contact with the zona pellucida, generating a unilaminar blastocyst lacking an inner cell mass (ICM). Blastomeres at the embryonic pole are thought to form the EPI and PrE precursor, while other blastomeres give rise to TE1,8.

Although well-described morphologically, the transcriptional changes that occur during early metatherian development have not been examined. Existing studies focus on immunoanalysis of selected lineage markers9,10. The timing of lineage formation and transcriptional signatures for the EPI, PrE and TE have not been established. This information will allow us to identify deeply-conserved mammalian lineage specifiers and refine models of mammalian embryogenesis.

Metatherians can also provide insight into the diversity of X-dosage compensation strategies in mammals. X-dosage compensation requires two mechanisms11. X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) occurs in females (XX), and balances X-chromosome expression in this sex with that in males (XY). X-chromosome upregulation (XCU) occurs in females and males, and balances expression from the single active X chromosome with that from the autosomes. Together, XCI and XCU ensure that in both sexes the X-to-autosome (X:A) ratio is equal to 1.

Eutherian XCI is carried out by the Xist non-coding RNA. In adult eutherians, XCI is random, but species reach this X-dosage compensation state via divergent strategies12. XCI in rabbits and humans occurs from the blastocyst stage, and many blastomeres initially express Xist from both X chromosomes. In contrast, XCI in mice begins earlier, from the 4-cell stage, and is imprinted, silencing the paternal X chromosome (Xp)13,14. Imprinted XCI is retained in the TE and PrE, but is reversed in the EPI, where random XCI later takes place. Metatherians have imprinted XCI in all tissues2 but no Xist gene15, and an alternative XCI-initiating candidate non-coding RNA, RSX, has been identified3. The ontogeny of RSX expression and XCI has not been determined, and potential mechanisms regulating metatherian imprinted XCI have not been defined.

Main

Lineage divergence

To gain insight into the evolution of mammalian lineage specification and X-dosage compensation, we performed scRNA-seq in the metatherian Monodelphis domestica (opossum). Gestation in our opossum colony lasts 14.5 days, with implantation at embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5). We performed scRNA-seq on unfertilized oocytes and embryos collected from E1.5 (1 – 2 cell stage) to E7.5 (blastocyst stage; Fig. 1a,b; Extended Data Fig. 1a). Following quality control, 832 single cells, derived from a total of 58 embryos and 6 oocytes, and with an average of 8388 expressed genes, were retained for analysis (Extended Data Table 1). Spearmann correlation coefficients were high between single cells harvested at each developmental age (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

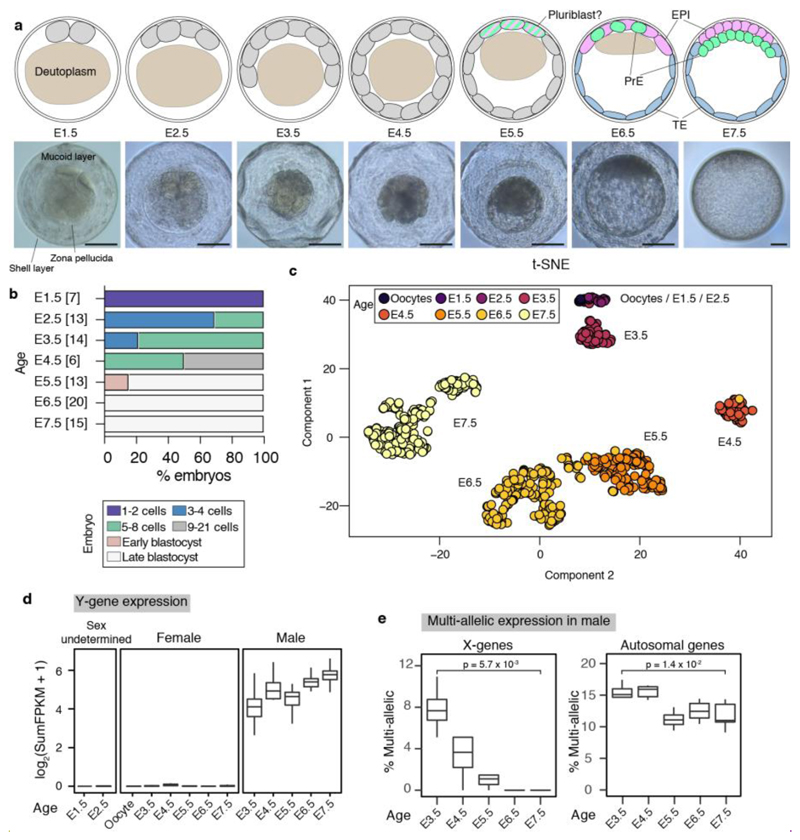

Figure 1. Opossum embryogenesis and single-cell clustering.

a. Schematic representation and light microscopy images of E1.5 – E7.5 opossum embryos. Scale bar 100 μm. b. Developmental progression of preimplantation opossum embryos. Number of embryos in parentheses. c. Unsupervised 3D t-SNE of scRNA-seq data.

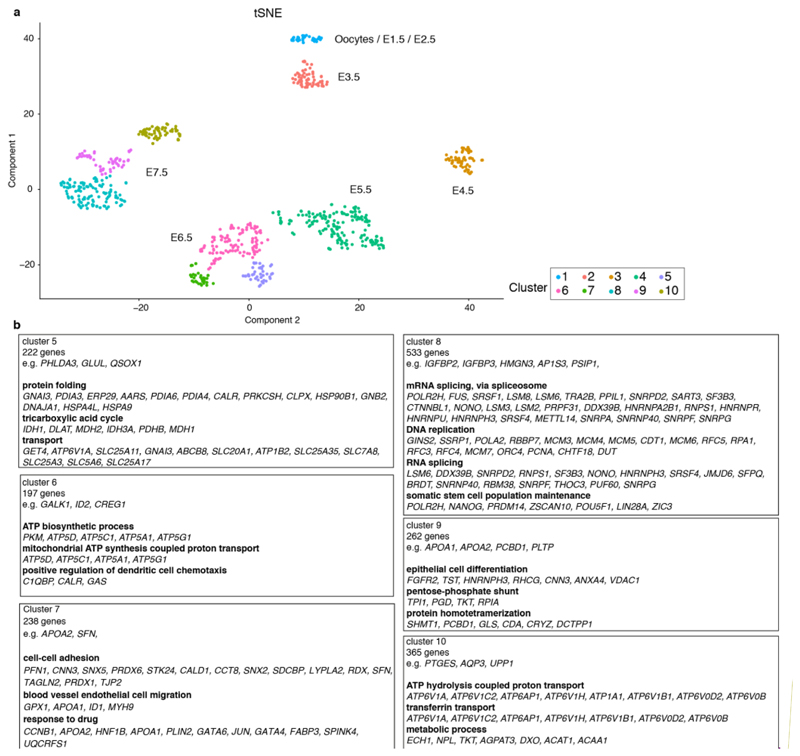

Unsupervised t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) analysis (Fig. 1c) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA; Extended Data Fig. 1c) showed that E3.5 – E7.5 single cells segregated into clusters according to their developmental age. Oocytes, E1.5 and E2.5 single cells formed a single cluster that was transcriptionally distinct from most E3.5 cells. This finding suggests that embryonic genome activation (EGA) occurs between E2.5 and E3.5. The timing of EGA was corroborated by measuring the onset of Y-gene expression in male embryos and examining changes in nucleolar morphology (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b; see Legend for explanation). To assess the maternal-embryonic transition we examined the abundance of X-encoded single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in male embryos16. The proportion of multiple X-encoded SNPs decreased from E3.5 to E5.5, and approached zero from E6.5 (Extended Data Fig. 2c; see Legend for explanation). Relative to eutherians, maternal product disappearance in the opossum is therefore protracted, with some oocyte-derived transcripts persisting until E5.5.

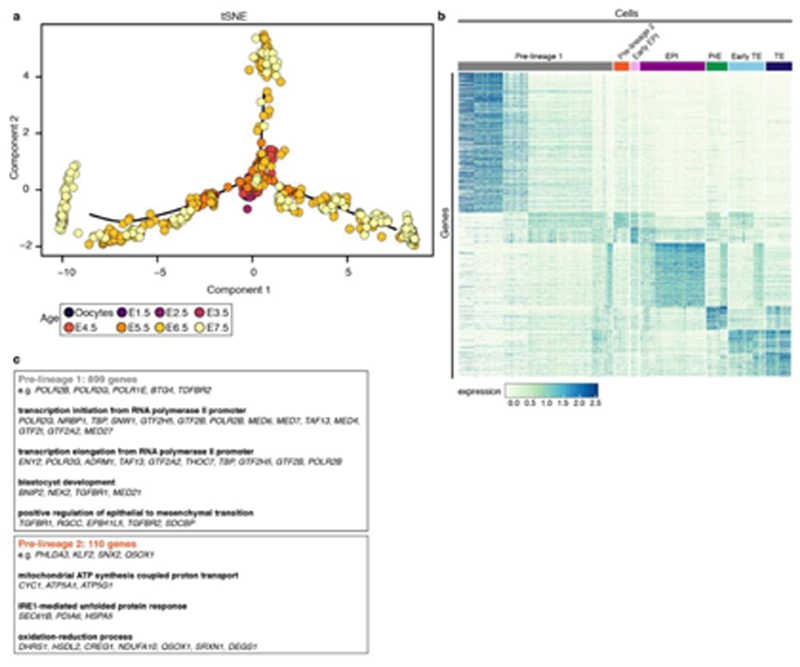

We used a semi-supervised approach to identify transcriptional similarities between single cells that were independent of developmental age and sex. We observed seven transcriptionally-distinct clusters via t-SNE (Fig. 2a,b; Supplementary Information Table 1). Oocytes and E1.5 - E5.5 cells fell into a single cluster. At E6.0, five additional clusters appeared, indicating that lineage divergence is first present at this age. At E7.5 a seventh cluster was evident. Unsupervised clustering also indicated that distinct lineages are present from E6.0 (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e).

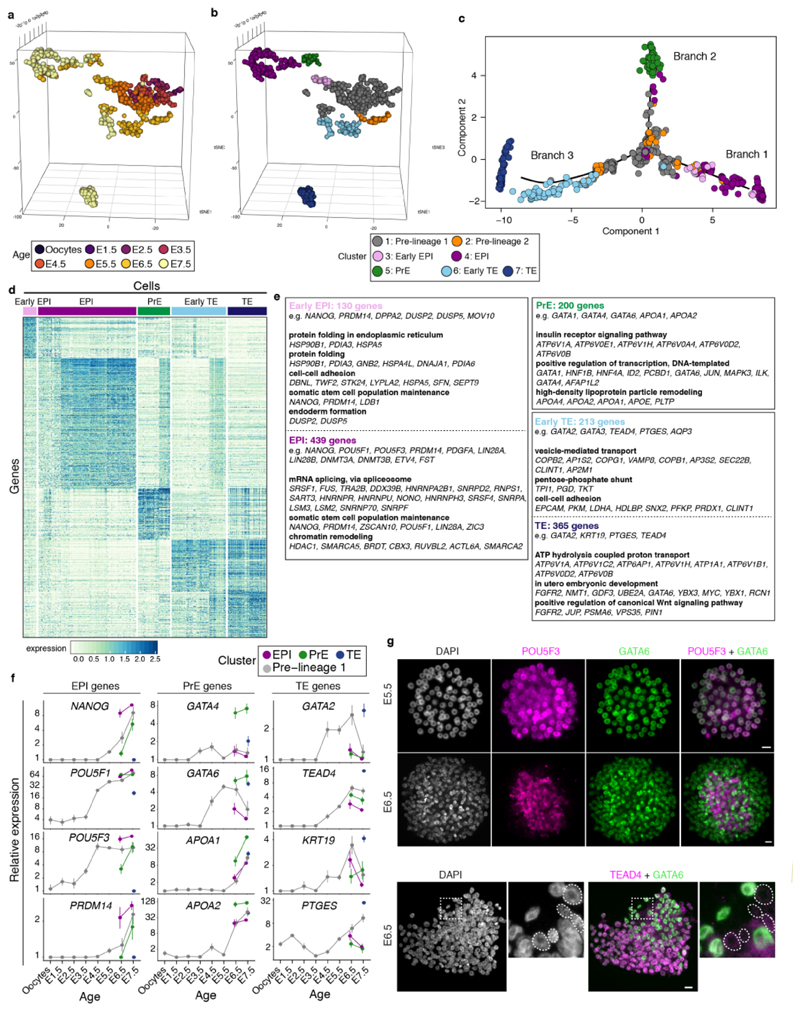

Figure 2. Opossum lineage formation.

a. Semi-supervised clustering 3D t-SNE with cells colored according to developmental age. b. same 3D t-SNE with cells colored according to cluster. c. Pseudotemporal ordering showing developmental trajectories between clusters. d. Heat map of genes defining early-EPI, EPI, PrE, early-TE and TE (developmental age ribbon shown). e. Gene ontology analysis for EPI, PrE and TE. f. Expression of POU5F3 / GATA6 at E5.5 (n = 3 embryos) and E6.5 (n = 5 embryos) and GATA6 / TEAD4 at E6.5 (n = 3 embryos). Dotted lines in bottom panel encircle putative EPI cells, which are negative for GATA6 and TEAD4. Images are maximum projection. Scale bars, 20um.

We determined developmental relationships between clusters using pseudotemporal ordering. The seven clusters formed three major branch trajectories (Fig. 2c; Extended Data Fig. 3a,b,c). Cluster 1 cells (grey) and cluster 2 cells (orange) were located on the branch intersection and all three branches (Extended Data Fig. 3a-e; and see Discussion). Cluster 3 (violet) and cluster 4 (magenta) cells localised to the same branch trajectory (Branch 1; Fig. 2c). The relatively proximal location of cluster 3 indicated that it contained cluster-4 progenitors. These clusters expressed genes that in eutherians regulate EPI formation and/or embryonic stem (ES) cell maintenance, including NANOG 17,18, PRDM14 19,20 and POU5F1 21,22 (Fig. 2d,e; Extended Data Fig. 3e,4a). Cluster 4 also expressed POU5F3, a POU5F1 paralogue that is absent in the eutherian genome, and in the tammar wallaby Macropus eugenii is expressed in the EPI9,23. In the opossum POU5F3 was expressed in all blastomeres at E5.5 and in the embryonic region from E6.5 (Fig. 2f). We therefore assigned clusters 3 and 4 as early-EPI and EPI, respectively.

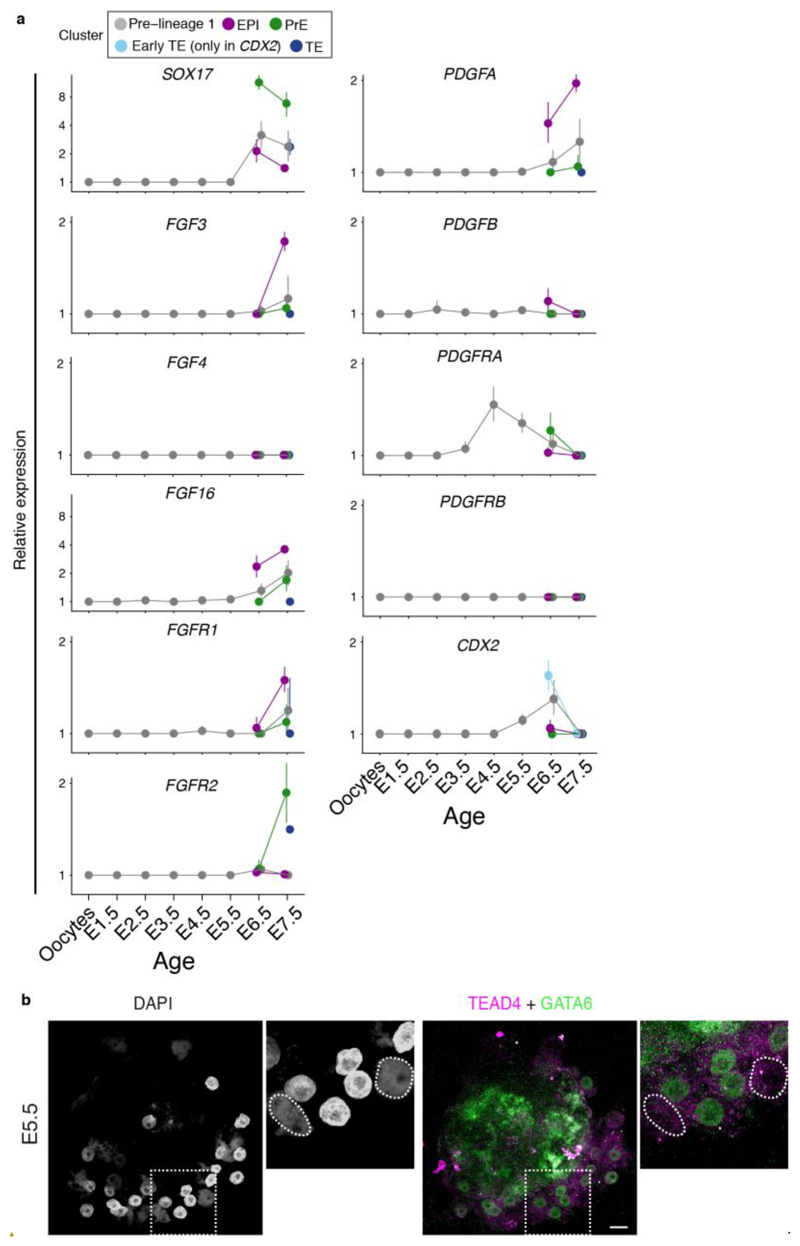

Cluster 5 (green), located on branch 2 (Fig. 2c), expressed the transcription factors GATA4 and GATA6, which in eutherians regulate PrE identity24–28 (Fig. 2d,e; Extended Data Fig. 4a). At E5.5, GATA6 was co-expressed with POU5F3 in all blastomeres. At E6.5 localisation of the two markers became distinct, with GATA6 expressed most highly in cells located near the embryonic disc, where the PrE is located29 (Fig. 2f). We therefore assigned cluster 5 as PrE. GATA6 was expressed more weakly in TE cells (Fig. 2f). In mice, FGF4 ligand produced by EPI-precursors signals via FGFR1 and FGFR2 to establish EPI-PrE segregation30–33. FGFR1 and FGFR2 were expressed in the opossum EPI and PrE, respectively, but while several FGF ligands were expressed in cluster 4EPI, FGF4 was not (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Interestingly however, PDGF-signalling components regulating later mouse EPI-PrE development showed similar expression patterns in the opossum. PDGFA was expressed preferentially in the EPI, while PDGFRA, whose activation in mice requires GATA634, was expressed in the PrE (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Although the semi-supervised approach identified PrE as a single cluster, E7.5 PrE cells exhibited a slightly different gene expression signature to earlier PrE cells, and therefore may represent a later PrE subtype (Fig. 2d).

Within branch 3, the location of cluster 6 (light blue) indicated that it was a precursor state to cluster 7 (dark blue; Fig. 2c). Both clusters expressed the transcription factors TEAD4 which in mice is required for TE formation35,36 and GATA2, which is implicated in TE formation37 but whose function in this process has not been extensively studied (Fig. 2d,e; Extended Data Fig. 3e,4a). At E5.5, TEAD4 could not be detected by immunostaining (Extended Data Fig. 4b), but at E6.5 it was expressed in TE cells (Fig. 2f). We therefore assigned cluster 6 as early-TE and cluster 7 as TE. Cluster 6early-TE also expressed CDX2, which in eutherians acts downstream of TEAD4 in TE development35,36,38,39 (Extended Data Fig. 3e,4a).

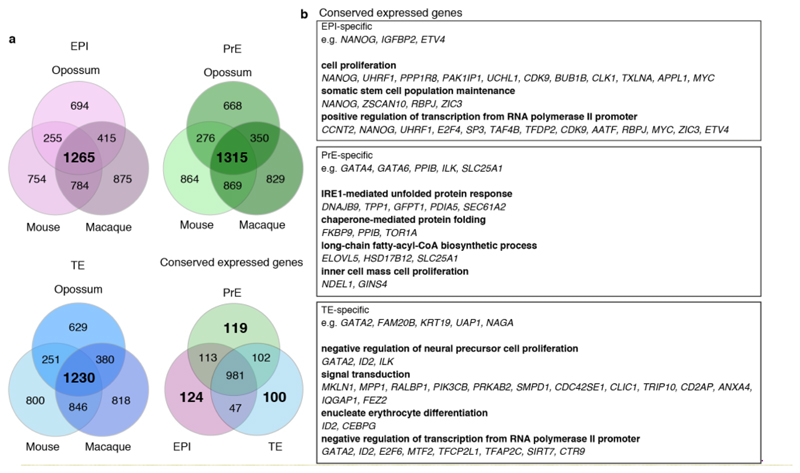

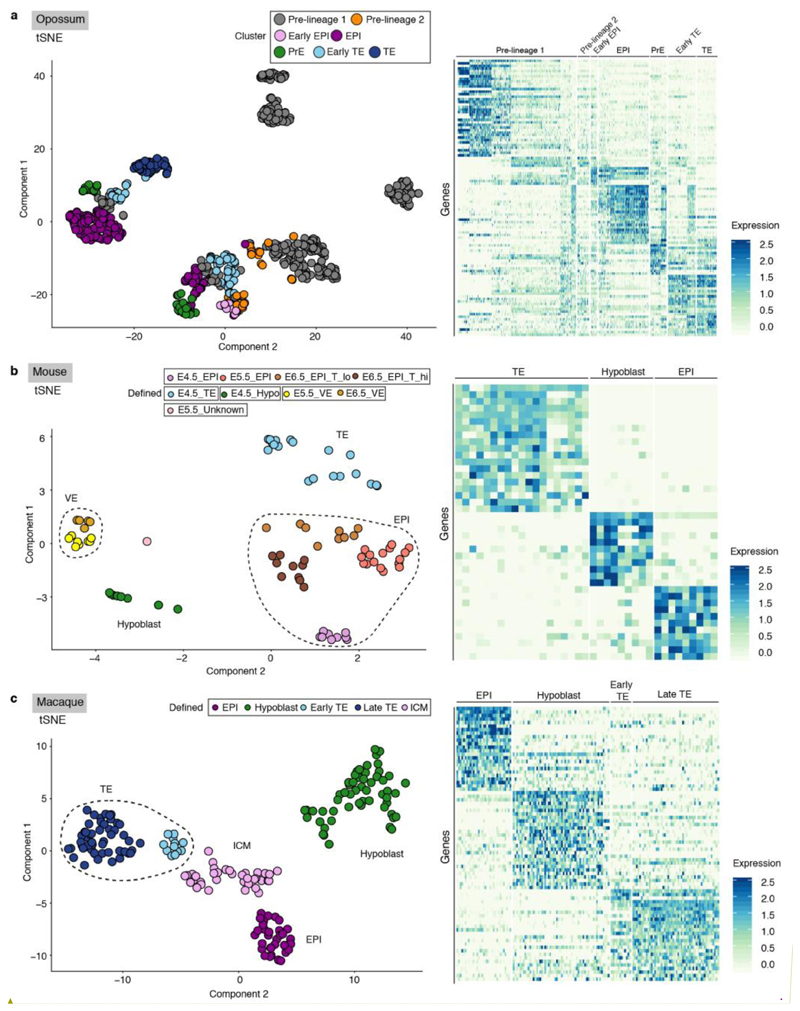

Significant differences in embryonic gene expression are observed between eutherian species40. To identify EPI-, PrE- and TE-markers conserved between eutherians and metatherians, we compared our opossum scRNA-seq datasets to those recently derived from E4.5 – E6.5 mouse, E6 – E9 cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis), and E5 - E7 human embryos16,41,42. Analysis of these datasets using the same approach used for our opossum scRNA-seq identified EPI-, PrE- and TE-clusters highly concordant with those assigned previously (Extended Data Fig. 5a-c). For EPI, PrE and TE, we identified genes expressed in all three eutherian species (n = 1725, 2003 and 1771 genes, respectively; Extended Data Fig. 6a; Supplementary Information Table 2). Overlapping these genes with those that define the opossum lineages identified 179 conserved early-EPI/EPI, 49 PrE and 125 early-TE/TE genes, including NANOG, DPPA4, ZSCAN10 (EPI), GATA4 and GATA6 (PrE), and GATA2 and AQP3 (TE; Extended Data Fig. 6b; Supplementary Information Table 2). These genes likely acquired specialised lineage functions prior to the eutherian-metatherian divergence 160 million years ago. Opossum EPI cells did not exhibit a transcriptional profile more reminiscent of eutherian naïve or primed EPI cells (Extended Data Fig. 6c,d).

X-dosage compensation

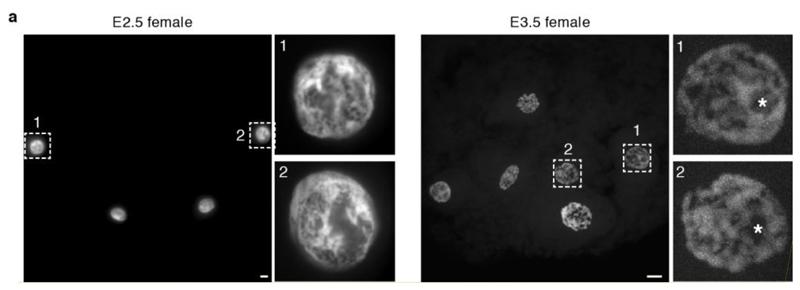

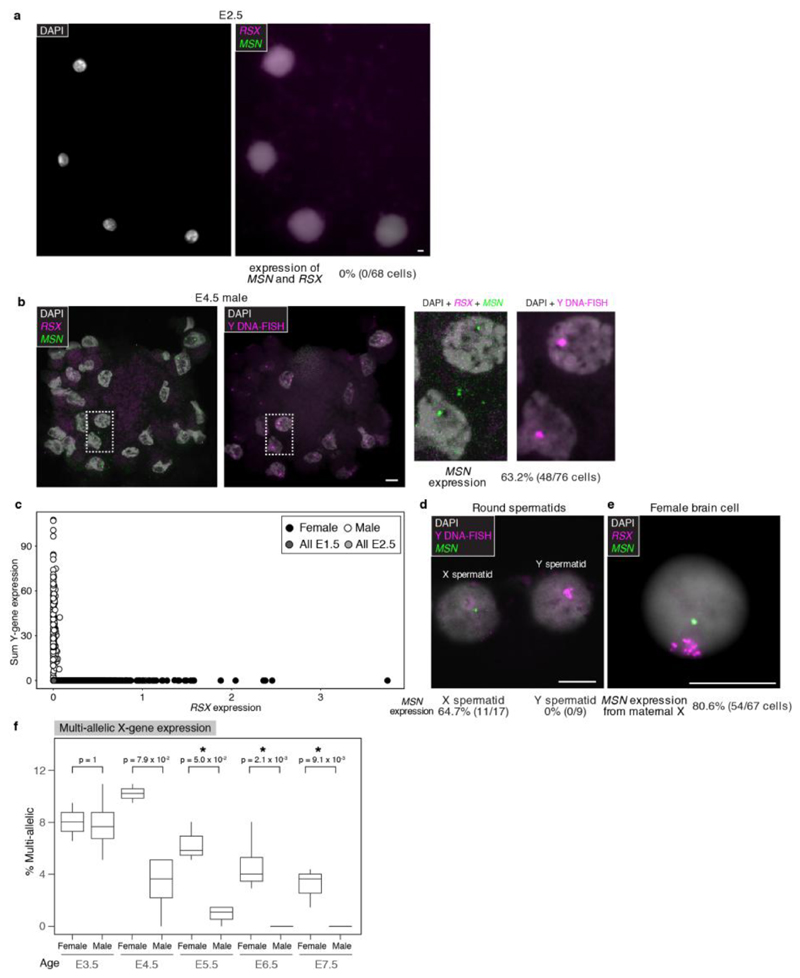

We established the timing of X-dosage compensation in opossum embryos. In both males and females, the X:A ratio was 1 at all developmental stages (Fig. 3a). This finding indicates that in females XCU and XCI are both instated early, providing a fully X-dosage compensated state at EGA. Consistent with early initiation of XCI, RSX transcription was already evident in females at E3.5 (Extended Data Fig. 7a). RSX RNA-FISH signals were absent at E2.5 (Extended Data Fig. 7b), but were detected at E3.5, when they were observed in 84% of blastomeres (Fig. 3b,c,e; Extended Data Table 2). RNA-FISH showed that RSX was expressed from one X chromosome (Fig. 3b,d), which SNP analysis revealed was Xp (see later). Male embryos, identified using Y chromosome DNA-FISH or Y-gene expression, did not express RSX (Extended Data Fig. 7c,d). Thus, initial transcription of RSX, like mouse Xist, occurs at EGA, is female-specific and Xp-restricted.

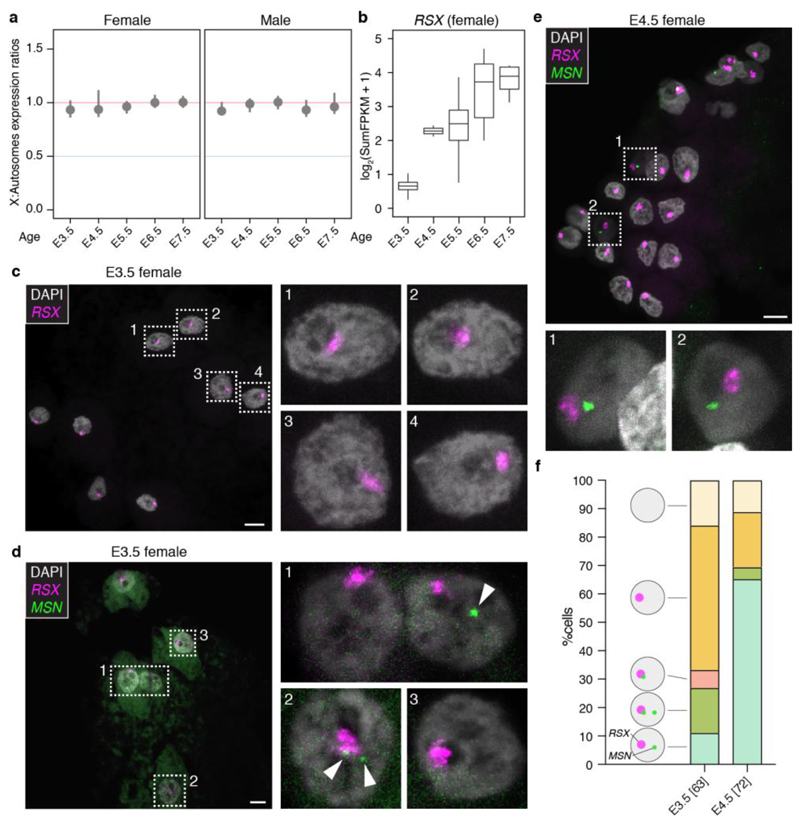

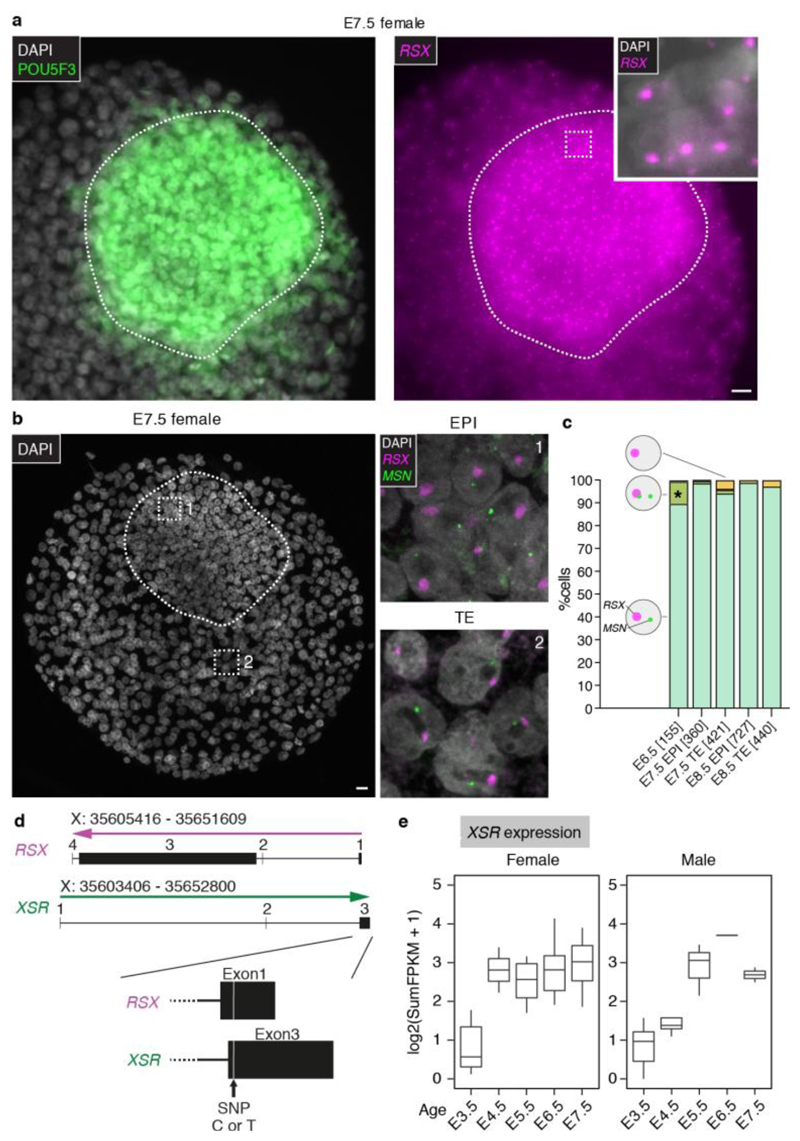

Figure 3. Ontogeny of opossum X-dosage compensation.

a. X:A ratios in male (n = 20) and female (n = 26) embryos and adult soma. b. RSX RNA-FISH in E3.5 female embryo; blastomeres magnified in insets. c,d. Dual RSX and MSN RNA-FISH in E3.5 (c, arrow head points to MSN RNA-FISH signal) and E4.5 (d) female embryos; blastomeres magnified in insets. Brightness is increased in (d) insets to more clearly visualize DAPI. Insets within insets in c and d show that the RSX-positive region is not DAPI-enriched (E3.5, n = 30 number of cells from 4 embryos, E4.5, n = 31 number of cells from 2 embryos). e. Summary of RSX and MSN expression data (E3.5, n = 12 embryos; E4.5, n = 5 embryos; total cell number in parentheses). Images are maximum projection. Scale bars, 10um. Blastomeres exhibit minimal cell-cell adhesion and thus separate during processing.

In mice, Xist RNA appears as a pinpoint signal at the 2-cell stage, and then accumulates, forming a cloud that silences Xp14. Surprisingly, in most E3.5 opossum blastomeres, RSX RNA signals were larger than pinpoints, and formed clouds resembling those in differentiated somatic cells3 (Fig. 3b,c,e). To establish Xp activity, we performed RNA-FISH for the X-gene MSN, which is distant (25Mb away) from the RSX locus (X chromosome length 79Mb). Like other X-genes43, MSN was expressed in spermatids, i.e. before fertilization, but was silent on Xp in adult female tissue (Extended Data Fig. 7e,f). MSN RNA signals were first detected in females at E3.5 (Fig. 3c,e; Extended Data Table 2). At this age, expression of the paternal MSN allele, identified by its close proximity to the RSX cloud, was observed in one quarter of blastomeres (Fig. 3c,e). However, 30% of MSN-expressing blastomeres exhibited paternal MSN silencing (Fig. 3c,e). At E4.5, MSN was silenced on Xp and expressed from Xm in most blastomeres (Fig. 3d,e). Further evidence for initial Xp activity was derived from bulk RNA-seq on whole embryos. There was a higher proportion of multi-allelic X-encoded SNPs in female than in male embryos from the same litter (Extended Data Fig. 7g). We identified informative SNPs for an additional eleven genes located across the X chromosome, and with the exception of the XCI-escapee ATRX 44, all exhibited complete or almost complete Xp-silencing by E4.5 (Extended Data Fig. 7h; Supplmentary Information Table 4). XCI therefore occurs rapidly after EGA in the opossum.

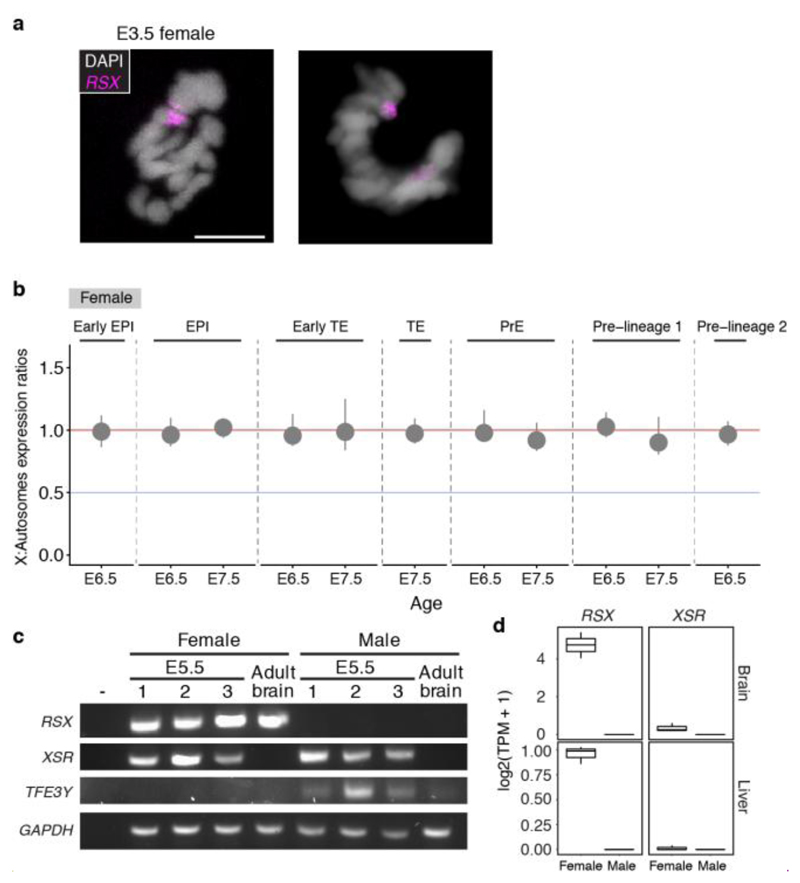

Biallelic X-expression in mice and humans is temporally and functionally linked to the pluripotent state45. We investigated whether pluripotent EPI opossum cells maintain or reverse XCI. RSX clouds were retained throughout the opossum embryo at E6.5, E7.5 and even at E8.5, both in non-EPI cells and EPI cells (the latter identified by POU5F3 immunostaining; Fig. 4a; Extended Data Table 2). Furthermore, in both cell populations, MSN expression remained predominantly monoallelic (Fig. 4b,c). Like Xist 46, RSX remained stably associated with the inactive X chromosome in dividing cells (Extended Data Fig 8a). These findings suggested that XCI is maintained in the opossum EPI. To corroborate them, we looked for evidence of XCI erasure, manifested as an elevation in the X:A ratio, in E6.0 - 7.5 early-EPI and EPI scRNA-seq data. The X:A ratio in these cell types was similar to that in cluster 1, cluster 2, PrE, early-TE and TE cells (Extended Data Fig 8b). Xp silencing is thus retained in the opossum EPI. These findings indicate that unlike in eutherians, pluripotency and XCI in the opossum are uncoupled.

Figure 4. XCI in the EPI and characterization of XSR.

a, Combined RSX RNA-FISH (EPI blastomeres magnified in upper inset) and POU5F3 immunostaining (whole EPI magnified in lower inset) in an E7.5 female embryo. b, Dual RSX and MSN RNA-FISH in an E7.5 female embryo (EPI and TE blastomeres magnified in insets). Images are maximum projection, inset to show that the RSX-positive region is not DAPI-enriched (EPI, n = 100, TE, n = 100 number of cells from 2 embryos). c. Summary of RSX and MSN expression data in E6.5, n = 2 embryos; E7.5, n = 2 embryos; and E8.5, n = 2 embryos; total cell number in parentheses. Asterisk denotes that cells with biallelic MSN-expression are observed both in the EPI and TE. d, RSX and XSR genomic organization and location of SNP used for parent-of-origin analysis. e. XSR locus organization and expression in females (n = 26 embryos) and males (n = 20 embryos) from E3.5 to E7.5. Scale bars, 20um.

Imprinted XCI in mice is achieved early in development by epigenetic silencing of the maternal Xist allele47, and later by repression of maternal Xist by the antisense RNA Tsix 48–51. The mechanisms regulating imprinted XCI in metatherians are unknown. We discovered in our scRNA-seq datasets an RNA that overlaps, is transcribed antisense to, and has distinct exon-intron boundaries to RSX (Fig. 4d). We called this antisense RNA XSR (reverse of RSX). Like RSX, XSR was expressed early in embryogenesis, being detectable at E3.5 (Fig. 4d). However, while RSX transcription was female-specific (Extended Data Fig 7c) and continues into adulthood3, XSR transcription was observed in both sexes and was developmentally regulated, occurring in embryos but not adults (Fig. 4d; Extended Data Fig 8c,d,e). Using SNP-analysis (see Materials and Methods), we determined parent-of-origin expression of RSX and XSR in whole embryos at E3.5 (n = 11 embryos), when XCI is initiating, and E5.5 (n = 8 embryos), when XCI is complete. As expected, in males at E3.5 and E5.5, XSR transcripts carried the maternal SNP (Supplementary Information Table 8). In females at E3.5 and E.5.5, RSX transcripts carried the paternal SNP. In contrast, XSR transcripts were exclusively of maternal origin (Supplementary Information Table 8). RSX and XSR thus show strictly monoallelic expression from Xp and Xm, respectively.

Discussion

Here we define the first single-cell transcriptional landscape of embryogenesis in a metatherian. We find that lineage divergence in the opossum initiates late in development. It has been suggested that in eutherians, lineage divergence to generate the TE and pluriblast (the EPI-PrE progenitor) occurs precociously because implantation in these mammals occurs very early32. Our findings support this view. Whether a pluriblast exists in the opossum remains an open question (see SI 9 for Supplementary Discussion). Genes with critical eutherian lineage functions exhibit similar expression patterns in the opossum. The core networks regulating lineage development may therefore be surprisingly similar between these diverse mammalian groups.

Our work also provides insight into the evolution of imprinted XCI. Organisms with late XCI-initiation exhibit transient biallelic XIST expression, and in rabbits this causes silencing of both X chromosomes. Biallelic X-silencing is clearly tolerated in later development but may compromise survival if initiated early. An imprint ensuring strictly monoallelic XCI would protect organisms with early XCI-initiation from the detrimental effects of inactivating both X chromosomes12. This model, which predicts that organisms with imprinted XCI also exhibit early XCI-initiation, is supported by work in mice13,14 and our current findings in the opossum. We propose that XSR serves a Tsix-like function in opossums, being expressed from the maternal X chromosome and in doing so antagonizing RSX expression to ensure precise monoallelic XCI during the especially-short embryonic period. Establishing the epigenetic status of the XSR locus in sperm, oocytes and early embryos will help assess its candidacy as a regulator of XCI imprinting.

Methods

Opossum maintenance

Opossums were maintained with appropriate care according to the United Kingdom Animal Scientific Procedures Act 1986 and the ethics guidelines of the Francis Crick Institute. All studies were approved by local ethical review and UK Home Office. Opossums were housed in individually ventilated cages and had free access to water and food. The light cycle consisted of 14 h of artificial light from 07:00 to 21:00. During non-breeding periods male and female opossums were maintained in different rooms. For breeding, male and female opossum cages were kept next to each other for two days, and then swapped into each other’s cages for two days, allowing exposure to pheromones, which induces ovulation. Subsequently they were put together, and breeding monitored by CCTV. To ensure accurate developmental timings, embryos were collected only from matings that occurred between 21.30 and 24.00.

Recovery of opossum oocytes, embryos and single cells

Oocytes were recovered from the oviduct of females mated to sterile vasectomized males. E1.5 (36 hours post-coitum; h.p.c), E2.5 (60h.p.c), E3.5 (84h.p.c), E4.5 (108h.p.c), E5.5 (132h.p.c), E6.0 (144h.p.c), E6.5 (156h.p.c), E7.5 (180h.p.c) and E8.5 (204h.p.c) preimplantation opossum embryos were recovered from the uterus (see Extended Data Table 1 for number of samples used for bulk and single-cell analysis). Oocytes and embryos were then maintained on ice in PBS-A during processing. For single-cell dissection, individual embryos were transferred to glass-bottom (MatTek no. #1.5) 35mm petri dish with 14mm bottom well. Under a dissection microscope, the embryo shell layer was removed using 30G needles. Subsequently the mucoid layer was removed by incubation in pre-warmed pronase solution (0.5% Protease; Sigma, Cat. No. p8811, in PBS-A) on a 37°C hot plate for 4 - 8 mins, depending on the mucoid layer thickness and embryonic stage. The shell but not mucoid layer is present in E7.5 and E8.5 embryos. Embryos were then rinsed twice in PBS-A. For whole embryo analysis, the embryo was collected in 1ul of PBS-A using a stripper pipette (Origio; 600μm inner diameter) and transferred to individual low bind RNase-free, DNase free Eppendorf tube containing 5ul of PBS-A. E1.5 to E4.5 embryos exhibit low cell-cell adhesion, so no additional treatment was required for single cell collection at these ages. Single cells were rinsed and collected in 1ul of PBS-A using a stripper pipette (270 μm inner diameter) and transferred to individual low bind RNase- and DNase-free 100μl PCR tubes containing 5μl of PBS-A. E5.5 to E7.5 embryo single-cell collection, embryos were incubated with 0.5% trypLE (Gibco., Cat. No.12604-013) in PBS-A, on a 37°C hot plate for 3 - 6 mins, prior to gentle dissociation by flushing. Single cells were picked up manually and transferred to a fresh glass bottom petri dish with PBS-A. All samples were stored at -80°C prior to cDNA preparation.

cDNA synthesis, library construction and read processing

Amplified double-stranded cDNA was prepared using SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit following manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech Laboratories; Cat no 634891). Single cells cDNA was subjected to 17 to 18 cycles of PCR amplification. E2.5, E3.5 and E4.5 whole embryos cDNA underwent 14 to 15 cycles amplification; E5.5 and E6.5 embryos, 10 - 11 cycles; E7.5, 7 - 8 cycles. cDNA quality was evaluated by High Sensitivity DNA assay on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser. Amplified double-stranded cDNA samples passing quality control checks were used to make libraries. A minimum of 1 ng of cDNA was used for the preparation of libraries using the Ovation Ultralow Library system V2 1-96 following manufacturer’s instructions (Cat. no. 0347). Library quality was assessed by Bioanalyser and concentration measured by Qubit assay. Libraries were paired-end sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 analyser with 100bp reads. Quality control was performed on FASTQ output files using the FastQC package and MGA52. Sequence data has been deposited at Annotare (EMBL-EBI; E-MTAB-7515).

Preparation of custom reference genome and annotation

A pseudo-Y chromosome was assembled using 15 known Monodelphis domestica cDNAs inferred to be Y-derived53, separated by ‘Ns’ (Y cDNAs: ARPP19Y, ATRY, HCFC1Y, HMGB3Y, HSFY1, HUWE1Y, KLF8Y, MECP2Y, PHF6Y, RBM10Y, RBMY, RPL10Y, TFE3Y, THOC2Y, UBE1Y1). This pseudo-Y chromosome was added to the pre-existing M. domestica genome, and the modified genome was used to create a custom genome index in HISAT2 v2.1.0. M. domestica transcriptome annotation was obtained from Ensembl (v91) and supplemented with annotation for Y-chromosome derived transcripts, RSX 3 and XSR (see later).

RNA sequencing analysis

Reads were aligned to the M. domestica genome using HISAT2 v2.1.0 (with parameters -3 0 -5 9 --fr --no-mixed --no-discordant) only uniquely mapped paired-reads with a MAPQ score > 40 were retained for further analysis. Transcript abundances were then computed using StringTie, and were collated and processed in R (v. 3.5.1) using Ballgown to obtain gene level abundances54,55. Subsequent single-cell analyses were performed using Monocle2 and Seurat packages56,57.

Quality control and t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbour Embedding (t-SNE) dimensionality reduction

Cells either with very low or very high mRNAs (+ or – 2.5sd from mean than that seen in the typical cell were excluded, and 832 high-quality single-cell transcriptomes were retained for further analysis. 43262 mean total mRNAs were detected per cell. Using an unsupervised approach, tSNE was performed on 8388 genes with a mean expression of above 0.1, with the top ten principal components derived from principal component analysis (PCA) as input.

Sexing and Y-gene expression

Based on the 15 aforementioned Y-linked genes, total expression from the Y chromosome (ΣFPKM Y) for a given embryo / oocyte was calculated. Embryos with ΣFPKM Y < 1.6 were classified as female embryos and those with ΣFPKM Y > 18.7 were classified as male (which corresponded to nearly a 12-fold difference in thresholds for ΣFPKM Y between the groups). ΣFPKM Y of 1.57 corresponded to the maximum value that was observed for a E7.5 “female” embryo (where a minimum ΣFPKM Y value for a equivalent “male” E7.5 embryo was 1730 FPKM; > 1000 - fold difference). Similarly, ΣFPKM Y of 18.7 corresponded to the minimum value for a E3.5 “male” embryo (where a maximum ΣFPKM Y value for a “female” E3.5 embryo was 0.15 FPKM; > 123.8 - fold difference).

Lineage compartmentalisation analysis

A semi-supervised approach was adopted in order to identify genes involved in the formation of cell lineages in M. domestica embryos. Briefly, a cell-type hierarchy data structure was initially utilised to classify possible cell-types based on published lineage markers9,10: NANOG expression for epiblast cells; CDX2 or TEAD4 expression (and no NANOG expression) for trophectoderm cells, and GATA4, GATA6 and APOA2 expression (and no NANOG expression) for primitive endoderm cells, in Monocle2. Using the function ‘markerDiffTable’ accompanied with cell-type hierarcy and a residual model supplied to subtract effects of gestational age, we identified 704 top markers for clustering (at a qval < 0.0005). t-SNE dimensionality reduction using the top ten principal components was then performed, followed by clustering. We further also performed differential expression analysis to define the genes that marked each cluster using Seurat (FindAllMarkers; with settings min.pct = 0.1, logfc.threshold = 0.25, using the Wilcoxon test). Markers with adjusted p-values < 0.1 were retained (n = 2356). The timing of lineage divergence and number of clusters was unchanged when the semi-supervised approach was repeated using trophectoderm markers GATA2 / GATA3 instead of CDX2 / TEAD4. For the unsupervised clustering, in Monocle2, 8388 genes were used, with the top ten principal components used to perform tSNE and clustering. For calculation of “relative expression”: Monocle2 employs the Census algorithm to convert relative RNA-seq expression levels into relative transcript counts58. This is performed by the function relative2abs() in R. The output, standardized expression values, are subsequently used in plotting.

Identification of conserved markers in therian lineage specification

Expression and annotation matrices for E6 – E9 cynomolgus macaque41 (Bioproject: PRJNA301445, Platform GPL19944), E4.5 – E6.5 mouse42 (Bioproject: PRJNA301445, Platform GPL15907) and E5 and E7 human16 (study: PRJEB11202; E-MTAB-3929; analysis restricted to cells retrieved post immunosurgery). scRNA-seq datasets were imported into the R package Monocle2 for detailed analyses separately. Gene annotation was obtained from the Ensembl Biomart site, which enabled comparison of RefSeq genes between species. Semi-supervised clustering was performed in each species using the same markers, which enabled the identification of single-cell clusters of representative lineages. The veracity of each lineage was confirmed by looking at marker expression, and comparing to clusters as defined previously16,41,42. Genes wit a median expression value of >= 1 in each cluster and a human orthologue were retained. Gene lists for each cell type were then analysed together using Venn diagrams in R using the package venn (v1.9).

Embryo immunofluorescence

Embryos were individually processed in glass bottom (no. #1.5) petri dishes. After removing the shell and mucoid layer, opossum embryos were transferred to a 35mm glass bottom (no. #1.5) petri dish coated with Poly-L-lysine, with a drop of PBS-A, on ice. After removing the PBS-A, embryos were fixed in ice-cold sterile filtered 4% PFA for 30 mins. Embryos were washed in cold PBS-A to remove fix, and ice-cold permeabilizing solution (0.5%Triton X-100, 2mM Vanadyl Ribonucleoside in PBSA) added for 30 mins. Embryos were rinsed in cold PBS-A and blocked in blocking buffer (0.15% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Tween in PBS-A) for 1 hour at room temperature. Antibodies diluted 1:100 in blocking buffer were added and embryos incubated at 4°C overnight. Antibodies: POU2 (gift from H. Niwa), GATA6 (goat anti-human GATA6, AF1700, R&D Systems) and TEAD4 (Rabbit anti-mouse Ab97460, Abcam). Embryos were washed three times for 5 mins in PBS-A, and incubated in secondary antibodies (Alexa-488, Alexa-568 - Molecular Probes; Invitrogen) diluted 1:250 in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Embryos were washed three times for 5 mins in PBS-A and stained with DAPI (1ug/ml) in PBS-A for 10 mins at room temperature. Embryos were rinsed once with PBS-A and mounted in antifade without DAPI with a coverslip. Embryos were stored in -20°C.

Embryo RNA- and DNA-FISH

After removing the permeabilizing solution (see previous section), embryos were rinsed in ice-cold PBS-A, dehydrated through ice-cold 70%, 80%, 95% and 100% ethanol for 5 minutes each, and air dried. BAC VM18-259O2 (CHORI) and a DIG-labelled oligo (TCTTCCTGGCTCCGACAGGCCGGGGTCCCTTCTTCCT) were used for MSN and RSX RNA FISH, respectively. XSR could not be detected using oligos due to its much lower expression relative to RSX. For this reason, BAC VM18-839J22del (CHORI), described previously3, was used to detect XSR in Extended Figure 8e. Since the BAC is double-stranded, it also hybridizes to RSX. XSR and RSX can easily be discriminated based on the differences in RNA signal size. BAC DNA was labelled using Nick Translation Direct Labelling Kit (30-608364/R1; Roche) according to manufacturer’s instructions, and using fluorescent nucleotides (for RSX spectrum orange – dUTP; 02N33-050, Vysis, MSN spectrum green – dUTP; 02N32-050, Abbott). Embryos were hybridized with a denatured mix of probes along with 1 µg salmon sperm DNA in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 25% dextran sulphate, 5 mg/ml BSA, 1mM Vanadyl Ribonucleoside complex in 2X SSC) at 37°C overnight in a humid chamber. Stringency washes were performed on a hot plate, three times for 5 mins in 50% formamide, 1X SSC (pH 7.2-7.4) pre-heated to 45°C, and three times for 5 mins in 2X SSC (pH 7-7.2) pre heated to 45°C. Embryos were stained with DAPI in 2xSSC (1ug/ml) for 10 mins at room temp, rinsed once with 2X SSC, and mounted in antifade without DAPI with a coverslip and stored at -20°C. Development of RNA-FISH signals for the DIG-RSX oligo probe was carried out as previously described59.

For DNA-FISH, coverslips were removed using two washes in 2X SSC. To remove primary transcripts, embryos were incubated in RNaseA 100ug/ml in 2xSSC at 37°C for 1 hour and rinsed in 2xSSC. Embryos were placed in 2X SSC pre-heated to 80°C for 7 mins, and then 70% formamide in 2X SSC pre-heated to 80°C, for 7 minutes (Y probe) or 20 minutes (MSN probe) on a 80°C hotplate. Embryos were then transferred to ice-cold 70% alcohol for 5 mins, dehydrated through 80%, 95% and 100% ethanol for 5 minutes each at room temperature, and air dried. A denatured opossum Y-chromosome probe (MAB1980; gift from David Page)43, labelled with orange–dUTP (02N33-050-Vysis), or MSN spectrum green – dUTP; 02N32-050, Abbott), was added and the embryo incubated at 37°C overnight in humid chamber supplemented with 50% formamide. Embryos were then washed 4 times for 3 mins in 2X SSC (pH 7.2-7.4) pre-heated to 45°C, and 4 times for 3 mins in 0.1X SSC (pH 7.2-7.4) pre-heated to 60°C, on a hot plate. After the final wash, embryos were stained with DAPI in 2X SSC (1ug/ml) for 10 mins, rinsed in 2X SSC and mounted in antifade without DAPI with a coverslip.

Microscopy and image acquisition

Embryos were imaged using an Olympus Confocal FV3000 microscope. Images of opossum spermatids and female brain cells RNA FISH and DNA FISH were captured using DeltaVision Microscopy System (100x/1.35NA Olympus UPlanApo objective; GE Healthcare). Images were processed and analyzed using ImageJ software.

Assessment of proportion of multi-allelic SNPs

Reads from each library were aligned to the M. domestica genome using HISAT2 v2.1.0, and only uniquely mapped reads with a MAPQ score > 40 were retained for further analysis. PCR duplicates were marked and removed using picardTools MarkDuplicates (v. 2.1.1). Processed BAM files were analysed using the samtools – bcftools pipeline (htslib 1.8) and each chromosome was individually analysed for ease of processing and subsequently merged. Only high-quality SNP loci (i.e. QUAL > 30 && DP4 > 10 && minimum GQ>15) that were detected in all the samples were then retained for further analysis (7443 autosomal and 137 X-chromosome loci). A ratio of heterozygous loci / all loci was then computed for each embryo, separately for the X chromosome and the autosomes (Fig 1e).

X-inactivation analysis using SNPs

SNPs were identified at 137 X-linked loci, corresponding to 42 X-genes. Only instances in which the mother was homozygous for one SNP and the father carried a distinct SNP were informative when assessing expression from Xm vs Xp. Parental SNPs were identified by Sanger sequencing of PCR amplicons (Supplementary Information Table 7).

X-chromosome expression analysis for X chromosome to autosome expression ratios

X:A median expression ratios with 95% confidence intervals were computed as described previously60, using the pairwiseCI package in R using ‘Median.ratio’ with 1,000,000 bootstrap replications. All genes that were expressed with FPKM > 0.1 in cells were included in the analysis.

Discovery of XSR

Alignment BAM files from whole embryos were merged and inspected using the IGV genome browser, focusing on the X-chromosome interval between PHF6 to FAM122B, which encompasses ENSMODG00000015247 (the HPRT1 orthologue) and RSX, and searching for exon-exon boundaries. XSR (EMBL-EBI identifier to follow) matches in part the in-silico predicted transcript ncRNA LOC107650328 in NCBI database, with LOC107650328 appearing to be slightly longer.

Parent-of-origin analysis of RSX and XSR

We identified in our colony a SNP at chrX: 35,651,239, which resides in exon 1 of RSX and exon 3 of XSR. We mated females homozygous C / C to males hemizygous T at this locus. Embryos were harvested at E3.5 and E5.5. Amplified double-stranded cDNA was prepared using SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit as described above. RT-PCR was carried out using RSX primers lying in exon 1 (TCCGATGAACCTATGGCTACC and exon 2 (CTCAAAGAGCCAGGTTTCCC) and with XSR primers lying in exon 2 (GGAAATTTCAGGAAGGCTGA) and exon 3 (CGAACCTTCCGATGAACCTA). We extracted reads corresponding to full length PCR product and assessed the percentage of reads heterozygous (C/T) at the SNP site (Supplementary Information Table 8). Control RT-PCRs were the Y-gene TFE3Y (F: TTCTCACCTCCACATGCACT, R: GAGGAAAGCAGGGGATCAGT) and GAPDH (F: TAAATGGGGAGATGCTGGAG, R :ATGCCGAAGTTGTCGTGAA).

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Illustration of late opossum embryo and single-cell clustering.

a. Schematic representation of opossum E8 – E12.5 embryos. b. Single-cell correlation coefficients. c. Principal component analysis.

Extended Data Figure 2. EGA and gene ontology analysis of genes in the clusters by unsupervised 3D t-SNE.

a. Y-gene expression in scRNA-seq data derived from oocytes (n = 6 cells), E1.5 (n = 7 embryos) and E2.5 (n = 5 embryos), and E3.5 to E7.5 presumptive male embryos (n = 20 embryos). Y-transcripts cannot be maternally deposited, because the Y chromosome is inherited from the father. Their appearance must therefore signify the initiation of embryonic transcription. b. Immature and mature (asterisk) nucleolar morphology in E2.5 and E3.5 embryos, respectively. Images are maximum projection. Scale bars, 10um. c. Percentage of multi-allelic X- and autosomally-encoded SNP variants in male bulk RNA-seq data (n = 28 embryos). When multiple SNPs for X-encoded RNAs are detected, maternal RNA is still present. However, when single SNPs are detected, it has been degraded. d. Unsupervised clustering of scRNA-seq data. e. Gene ontology analysis for genes in d.

Extended Data Figure 3. Identification of lineage specific genes.

a. Pseudotemporal ordering for Fig. 2c in 3D. b. pseudotemporal ordering from Fig. 2c separated by sex. c. Pseudotemporal from 2c with cells coloured according to developmental age. d. Full heat map of genes defining cluster 1, cluster 2, early-EPI, EPI, PrE, early-TE and TE. e. Gene ontology analysis for cluster 1 and cluster 2, early-EPI and early-TE.

Extended Data Figure 4. Lineage marker genes expression and immunostaining.

a. Expression of representative genes in cluster 1, EPI, PrE, early-TE and TE. b. Expression of GATA6 and TEAD4 at E5.5. All cells are TEAD4 negative, even those not expressing GATA6 (encircled). Images are maximum projection. Scale bars, 10um.

Extended Data Figure 5. Early embryo lineages in eutherians using the same approach used for opossum embryo scRNA-seq.

Semi-supervised 3D t-SNE (left) and heatmap (right) of a. mouse, b. macaque and c. human embryos, with single cells colored according to cluster.

Extended Data Figure 6. Eutherian and metatherian lineage conservation.

a. Genes expressed in EPI, PrE and TE in mouse, macaque and human. b. Heatmap showing expression of conserved genes in opossum. c. expression of opossum genes whose orthologues are associated with naïve and primed pluripotency in macaque. d. expression heatmap of opossum genes whose mouse orthologues are expressed specifically in mouse E6.5 EPI (CORO1A) of E4.5 EPI (all other genes).

Extended Data Figure 7. EGA and RSX expression.

a. RSX expression in females. b. Dual RSX and MSN RNA-FISH in E2.5 embryo (16 embryos = 68 cells). c. Dual RSX and MSN RNA-FISH (left), followed by Y chromosome DNA-FISH (right) in E4.5 male embryo; blastomeres magnified in insets. d. Y-gene versus RSX expression. e. MSN RNA-FISH followed by Y chromosome DNA-FISH in opossum spermatids. f, Dual RSX and MSN RNA-FISH in female opossum brain cells. Images are maximum projection. Scale bars 10um. g. Percentage of multi-allelic X-SNP variants in female (n = 15 embryos) and male (n = 28 embryos) bulk RNA-seq data from E3.5 – E7.5. Mann-Whitney test was used to calculate p-values. For RNA-FISH data quantitation shown below images. h. SNP analysis showing expression of eleven genes from Xp in E3.5 (n = 3) and E4.5 (n = 2) embryos. Location of RSX shown. Asterisks denote instances where informative SNPs were not present. ATRX is the only gene exhibiting no Xp expression at E3.5 (star): expression from Xm at this age could represent maternal products, with activation of embryonic ATRX initiating at E4.5.

Extended Data Figure 8. Dosage compensation and XSR expression.

a. RSX localization to the inactive X chromosome (identified using MSN DNA FISH) in dividing cells. Images are maximum projection. Scale bar, 10um. b. X:A ratios in female clusters at E6.0 - E7.5. c. RTPCR analysis of RSX, XSR, TFE3Y and GAPDH in E5.5 female and male embryos. d. RSX and XSR expression in adult female and male tissues. e. Dual RSX / XSR RNA FISH in E3.5 female and male embryos. See Materials and Methods for explanation why RSX and XSR FISH signals are the same colour.

Extended Data Table 1. Opossum embryos and single cells used for RNA seq.

| Age | No of embryos used for bulk RNA-Seq | Male embryos | Female embryos |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oocytes | 9 | ||

| E1.5 | 7 | ||

| E2.5 | 8 | ||

| E3.5 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| E4.5 | 7 | 5 | 2 |

| E5.5 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| E6.5 | 13 | 9 | 4 |

| E7.5 | 9 | 6 | 3 |

| Total | 9 oocytes 58 embryos | 28 | 15 |

| Age | No of embryos used for scRNA-Seq | No of cells used for scRNA-Seq | Male embryos | Female embryos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oocytes | 6 | |||

| E1.5 | 7 | 7 | ||

| E2.5 | 5 | 21 | ||

| E3.5 | 14 | 62 | 8 | 6 |

| E4.5 | 6 | 55 | 4 | 2 |

| E5.5 | 7 | 140 | 3 | 4 |

| E6.0 | 5 | 125 | 2 | 3 |

| E6.5 | 8 | 201 | 1 | 7 |

| E7.5 | 6 | 215 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 58 embryos | 832 (826 cells and 6 oocytes) | 20 | 26 |

Extended Data Table 2. Preimplantation opossum embryo RNA FISH for RSX and MSN.

| Embryo stage | Number of female embryos | Numberof blastomeres | NO FISH signal | RSX only | RSX and paternal MSN | RSX, maternal and paternal MSN | RSX and maternal MSN | No RSX, maternal and paternal MSN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3.5 | 12 | 63 | 10 (16%) | 32 (51%) | 4 (6%) | 10 (16%) | 7 (11%) | 0 |

| E4.5 | 5 | 72 | 8 (11%) | 14 (19%) | 0 | 3 (4%) | 47 (66%) | 0 |

| E6.5 Complete embryo | 2 | 394 | 2 (0.5%) | 27 (6.8%) | 0 | 36 (9.2%) | 329 (83.5%) | 0 |

| E7.5 Epi/PrEcells (random sampling) | 2 | 460 | 1 (0.2%) | 11 (2.4%) | 0 | 13 (2.9%) | 435 (94.5%) | 0 |

| E7.5 TE cells (random sampling) | 2 | 528 | 0 | 19 (3.6%) | 1 (0.2) | 15 (2.8%) | 493 (93.5%) | 0 |

| E8.5 Epi/PrEcells (random sampling) | 2 | 727 | 0 | 10(1.4%) | 1(0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 712 (98%) | 3 (0.4%) |

| E8.5 TE cells (random sampling) | 2 | 440 | 0 | 12 (2.7%) | 0 | 2 (0.4%) | 426 (96.9%) | 0 |

Extended Data Table 2. Preimplantation opossum embryo RNA FISH for RSX alone.

| Embryo stage | Number of female embryos | Number of blastomeres | NO FISH signal | RSX only |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E6.5 Complete embryo | 1 | 241 | 0 | 241 |

| E7.5 Epi/PrEcells (random sampling) | 2 | 645 | 0 | 645 (100%) |

| E7.5 TE cells (random sampling) | 2 | 647 | 0 | 647 (100%) |

Extended Data Table 3.

| Genes ID | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| PIH1D3 | GAGACGGGAGGTCCTAGGTT | GACAGACCCTGGCAATTTTT |

| NTF2 | GCCTTTTCCCAATTCAAACA | AAGTAGCCATGGAGGCTGTG |

| TAX1 | TTCTTACAGGTGGCCTCTGG | AGGCTTGAAAATCCAGCAGA |

| CD99 | TGGAGTTTCACTAAGGCACCA | GATTCCTGTTTTGGGATGGA |

| ATRX | GCCTGTGGAATTCTGGTCAT | GGCAAAACAAAGTGGCTCAT |

| GJB1 | TGGATAAGAGAGCACCAGCA | GGGAGGGGCATTTAGTGAA |

| CXXC1 | GCCAAGGTCAGGGTATTTGA | GTCATGCTGGATGGTCTGGT |

| ERCC | AAATGTGCAGTGGTGGGAAT | GCTGCTGCTGCTTCTTCTTC |

| GLA | TGGCAAACACCTTTAGGAAGA | GTTTAGGGGTGGATGGGAAT |

| TIMM8A | ATGACTATCAGGGCTGGACA | TTGGAGATGCCAAGAGGAAG |

| CSTF2 | AAACAGAGCTGGGGAACAGA | TCCAGAATTTGAGTAGGTCCAGA |

Extended Data Table 4.

| E3.5 EMBRYO | Number of reads aligned to XSR transcript | Percentage of XSR reads with maternal SNP (C) | Percentage of XSR reads with paternal SNP (T) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Female | 33233 | 100 | 0 |

| E3 Female | 32368 | 100 | 0 |

| E6 Female | 3484 | 100 | 0 |

| E8 Female | 4891 | 100 | 0 |

| E12 Female | 2562 | 100 | 0 |

| E2 Male | 115 | 100 | 0 |

| E4 Male | 5061 | 100 | 0 |

| E7Male | 20324 | 100 | 0 |

| E9 Male | 1122 | 100 | 0 |

| E10 Male | 1902 | 100 | 0 |

| E11 Male | 3689 | 100 | 0 |

| E5.5 EMBRYO | |||

| E2 Female | 48805 | 100 | 0 |

| E3 Female | 7198 | 100 | 0 |

| E7 Female | 51009 | 100 | 0 |

| E8 Female | 43192 | 100 | 0 |

| E1 Male | 43850 | 100 | 0 |

| E4 Male | 87968 | 100 | 0 |

| E5 Male | 36635 | 100 | 0 |

| E6 Male | 47623 | 100 | 0 |

| E3.5 FEMALE EMBRYO | Number of reads aligned to RSX transcript | Percentage of RSX reads with maternal SNP (C) | Percentage of RSX reads with paternal SNP (T) |

| E1 Female | 34451 | 0 | 100 |

| E3 Female | 23443 | 0 | 100 |

| E6 Female | 25415 | 0 | 100 |

| E8 Female | 14768 | 0 | 100 |

| E12 Female | 25254 | 0 | 100 |

| E5.5 FEMALE EMBRYO | |||

| E2 Female | 29773 | 0 | 100 |

| E3 Female | 18606 | 0 | 100 |

| E7 Female | 14401 | 0 | 100 |

| E8 Female | 33586 | 0 | 100 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by European Research Council (CoG 647971) and the Francis Crick Institute, which receives its core funding from Cancer Research UK (FC001193), UK Medical Research Council (FC001193), and Wellcome Trust (FC001193). We thank the Francis Crick Institute Biological Research, Advanced Sequencing and Robert Goldstone, Light Microscopy facilities and D. Bell for their expertise, H. Niwa for the POU5F3 antibody, David Page for the MAB1980 (opossum Y-chromosome) probe, and members of the J.M.A.T and Kathy Niakan laboratories for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Main Text Statements

J.M.A.T and S.K.M conceived the project. S.K.M performed and optimized embryo collection, single-cell harvesting, RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, RNA-FISH, DNA-FISH, immunofluorescence, RT-PCR and MiSeq. M.S performed computational analysis. T.H advised on data representation and generated figures. J.M.A.T, S.K.M and M.S wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

All cytological data and R-markdown files in this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary files 3 to 6). Sequence data has been deposited at ArrayExpress (E-MTAB-7515).

Bibliography

- 1.Frankenberg SR, de Barros FR, Rossant J, Renfree MB. The mammalian blastocyst. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2016;5:210–232. doi: 10.1002/wdev.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharman GB. Late DNA replication in the paternally derived X chromosome of female kangaroos. Nature. 1971;230:231–232. doi: 10.1038/230231a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant J, et al. Rsx is a metatherian RNA with Xist-like properties in X-chromosome inactivation. Nature. 2012;487:254–258. doi: 10.1038/nature11171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graves JA, Renfree MB. Marsupials in the age of genomics. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2013;14:393–420. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samollow PB. The opossum genome: insights and opportunities from an alternative mammal. Genome Res. 2008;18:1199–1215. doi: 10.1101/gr.065326.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murchison EP, et al. Genome sequencing and analysis of the Tasmanian devil and its transmissible cancer. Cell. 2012;148:780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.VandeBerg JL, Williams-Blangero S, Hubbard GB, Ley RD, Robinson ES. Genetic analysis of ultraviolet radiation-induced skin hyperplasia and neoplasia in a laboratory marsupial model (Monodelphis domestica) Archives of dermatological research. 1994;286:12–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00375837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selwood L. Mechanisms underlying the development of pattern in marsupial embryos. Current topics in developmental biology. 1992;27:175–233. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60535-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frankenberg S, Shaw G, Freyer C, Pask AJ, Renfree MB. Early cell lineage specification in a marsupial: a case for diverse mechanisms among mammals. Development. 2013;140:965–975. doi: 10.1242/dev.091629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison JT, Bantilan NS, Wang VN, Nellett KM, Cruz YP. Expression patterns of Oct4, Cdx2, Tead4, and Yap1 proteins during blastocyst formation in embryos of the marsupial, Monodelphis domestica Wagner. Evol Dev. 2013;15:171–185. doi: 10.1111/ede.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng X, Berletch JB, Nguyen DK, Disteche CM. X chromosome regulation: diverse patterns in development, tissues and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:367–378. doi: 10.1038/nrg3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okamoto I, et al. Eutherian mammals use diverse strategies to initiate X-chromosome inactivation during development. Nature. 2011;472:370–374. doi: 10.1038/nature09872. nature09872 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mak W, et al. Reactivation of the paternal X chromosome in early mouse embryos. Science. 2004;303:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1092674303/5658/666. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okamoto I, Otte AP, Allis CD, Reinberg D, Heard E. Epigenetic dynamics of imprinted X inactivation during early mouse development. Science. 2004;303:644–649. doi: 10.1126/science.10927271092727. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duret L, Chureau C, Samain S, Weissenbach J, Avner P. The Xist RNA gene evolved in eutherians by pseudogenization of a protein-coding gene. Science. 2006;312:1653–1655. doi: 10.1126/science.1126316. 312/5780/1653 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petropoulos S, et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Lineage and X Chromosome Dynamics in Human Preimplantation Embryos. Cell. 2016;165:1012–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chambers I, et al. Nanog safeguards pluripotency and mediates germline development. Nature. 2007;450:1230–1234. doi: 10.1038/nature06403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitsui K, et al. The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell. 2003;113:631–642. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00393-3. S0092867403003933 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chia NY, et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen reveals determinants of human embryonic stem cell identity. Nature. 2010;468:316–320. doi: 10.1038/nature09531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaji M, et al. PRDM14 ensures naive pluripotency through dual regulation of signaling and epigenetic pathways in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:368–382. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nichols J, et al. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fogarty NME, et al. Genome editing reveals a role for OCT4 in human embryogenesis. Nature. 2017;550:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature24033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frankenberg S, Pask A, Renfree MB. The evolution of class V POU domain transcription factors in vertebrates and their characterisation in a marsupial. Dev Biol. 2010;337:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koutsourakis M, Langeveld A, Patient R, Beddington R, Grosveld F. The transcription factor GATA6 is essential for early extraembryonic development. Development. 1999;126:723–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrisey EE, et al. GATA6 regulates HNF4 and is required for differentiation of visceral endoderm in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3579–3590. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wamaitha SE, et al. Gata6 potently initiates reprograming of pluripotent and differentiated cells to extraembryonic endoderm stem cells. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1239–1255. doi: 10.1101/gad.257071.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimosato D, Shiki M, Niwa H. Extra-embryonic endoderm cells derived from ES cells induced by GATA factors acquire the character of XEN cells. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujikura J, et al. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells is induced by GATA factors. Genes Dev. 2002;16:784–789. doi: 10.1101/gad.968802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mate KE, Robinson ES, Vandeberg JL, Pedersen RA. Timetable of in vivo embryonic development in the grey short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica) Mol Reprod Dev. 1994;39:365–374. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang M, Garg V, Hadjantonakis AK. Lineage Establishment and Progression within the Inner Cell Mass of the Mouse Blastocyst Requires FGFR1 and FGFR2. Dev Cell. 2017;41:496–510 e495. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molotkov A, Mazot P, Brewer JR, Cinalli RM, Soriano P. Distinct Requirements for FGFR1 and FGFR2 in Primitive Endoderm Development and Exit from Pluripotency. Dev Cell. 2017;41:511–526 e514. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossant J. Genetic Control of Early Cell Lineages in the Mammalian Embryo. Annu Rev Genet. 2018;52:185–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120116-024544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris SA, Graham SJ, Jedrusik A, Zernicka-Goetz M. The differential response to Fgf signalling in cells internalized at different times influences lineage segregation in preimplantation mouse embryos. Open biology. 2013;3 doi: 10.1098/rsob.130104. 130104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Artus J, Panthier JJ, Hadjantonakis AK. A role for PDGF signaling in expansion of the extra-embryonic endoderm lineage of the mouse blastocyst. Development. 2010;137:3361–3372. doi: 10.1242/dev.050864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yagi R, et al. Transcription factor TEAD4 specifies the trophectoderm lineage at the beginning of mammalian development. Development. 2007;134:3827–3836. doi: 10.1242/dev.010223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishioka N, et al. Tead4 is required for specification of trophectoderm in pre-implantation mouse embryos. Mech Dev. 2008;125:270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krendl C, et al. GATA2/3-TFAP2A/C transcription factor network couples human pluripotent stem cell differentiation to trophectoderm with repression of pluripotency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E9579–E9588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708341114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strumpf D, et al. Cdx2 is required for correct cell fate specification and differentiation of trophectoderm in the mouse blastocyst. Development. 2005;132:2093–2102. doi: 10.1242/dev.01801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu G, et al. Initiation of trophectoderm lineage specification in mouse embryos is independent of Cdx2. Development. 2010;137:4159–4169. doi: 10.1242/dev.056630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blakeley P, et al. Defining the three cell lineages of the human blastocyst by single-cell RNA-seq. Development. 2015;142:3613. doi: 10.1242/dev.131235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamura T, et al. A developmental coordinate of pluripotency among mice, monkeys and humans. Nature. 2016;537:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature19096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakamura T, et al. SC3-seq: a method for highly parallel and quantitative measurement of single-cell gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahadevaiah SK, et al. Key features of the X inactivation process are conserved between marsupials and eutherians. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1478–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.041. S0.960/9822(09)01467-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X, Douglas KC, Vandeberg JL, Clark AG, Samollow PB. Chromosome-wide profiling of X-chromosome inactivation and epigenetic states in fetal brain and placenta of the opossum, Monodelphis domestica. Genome Res. 2014;24:70–83. doi: 10.1101/gr.161919.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sahakyan A, et al. Human Naive Pluripotent Stem Cells Model X Chromosome Dampening and X Inactivation. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duthie SM, et al. Xist RNA exhibits a banded localization on the inactive X chromosome and is excluded from autosomal material in cis. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:195–204. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.2.195. ddc032 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue A, Jiang L, Lu F, Zhang Y. Genomic imprinting of Xist by maternal H3K27me3. Genes Dev. 2017;31:1927–1932. doi: 10.1101/gad.304113.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JT. Disruption of imprinted X inactivation by parent-of-origin effects at Tsix. Cell. 2000;103:17–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00101-x. S0092-8674(00)00101-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maclary E, et al. Differentiation-dependent requirement of Tsix long non-coding RNA in imprinted X-chromosome inactivation. Nature communications. 2014;5:4209. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sado T, Wang Z, Sasaki H, Li E. Regulation of imprinted X-chromosome inactivation in mice by Tsix. Development. 2001;128:1275–1286. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohhata T, Senner CE, Hemberger M, Wutz A. Lineage-specific function of the noncoding Tsix RNA for Xist repression and Xi reactivation in mice. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1702–1715. doi: 10.1101/gad.16997911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hadfield J, Eldridge MD. Multi-genome alignment for quality control and contamination screening of next-generation sequencing data. Front Genet. 2014;5:31. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cortez D, et al. Origins and functional evolution of Y chromosomes across mammals. Nature. 2014;508:488–493. doi: 10.1038/nature13151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, Salzberg SL. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:1650–1667. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pertea M, et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:290–295. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trapnell C, et al. The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:381–386. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, Satija R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:411–420. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qiu X, et al. Single-cell mRNA quantification and differential analysis with Census. Nat Methods. 2017;14:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turner JM, Mahadevaiah SK, Ellis PJ, Mitchell MJ, Burgoyne PS. Pachytene asynapsis drives meiotic sex chromosome inactivation and leads to substantial postmeiotic repression in spermatids. Dev Cell. 2006;10:521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sangrithi MN, et al. Non-Canonical and Sexually Dimorphic X Dosage Compensation States in the Mouse and Human Germline. Dev Cell. 2017;40:289–301 e283. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All cytological data and R-markdown files in this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary files 3 to 6). Sequence data has been deposited at ArrayExpress (E-MTAB-7515).