Abstract

Being aware of one's own ability to interact socially is crucial to everyday life. After a brain injury, patients may lose their capacity to understand others' intentions and beliefs, that is, the Theory of Mind (ToM). To date, the debate on the association between ToM and other cognitive deficits (in particular executive functions and behavioural disorders) remains open and data regarding awareness of ToM deficits are meagre.

By means of an ad-hoc neuropsychological battery of tests, we report on a patient who suffers from ToM deficits and is not aware of these disorders, although aware of his other symptoms. The study is accompanied by a review of the literature (PRISMA guidelines) demonstrating that ToM deficits are independent from executive functions. Furthermore, an advanced lesion analysis including tractography was executed. The results indicate that: i) ToM deficits can be specific and independent from other cognitive symptoms; ii) unawareness may be specific for ToM impairment and not involve other disorders and; iii) the medial structures of the limbic, monitoring and attentional systems may be involved in anosognosia for ToM impairment.

Keywords: Anosognosia, Theory of Mind, DTI, Awareness, Frontal Lesion

1. Introduction

The reduced capacity to identify or realistically judge one's own abilities and deficits is known as Anosognosia (from the Greek: a, without; noso, disease; gnosia, knowledge, Mograbi & Morris, 2018). Although the term was initially coined in reference to a lack of awareness of motor deficits (Anosognosia for hemiplegia, Babinski, 1914), it has subsequently been applied to various different pathological conditions and etiologies (e.g. memory and aphasia; Prigatano, 2010). Experimental and clinical studies have also documented that anosognosia may be deficit specific, with people who are affected being unaware of certain deficits and fully aware of others (O'Keeffe, Dockree, Moloney, Carton, & Robertson, 2007; Prigatano, 2010). In brain damaged patients, self-awareness deficits have been observed in relation to a wide variety of disorders and phenomena such as sensory-motor problems (e.g. anosognosia for hemiplegia, AHP, Cocchini, Logie, Della Sala, MacPherson, & Baddeley, 2002; Anton Syndrome, McDaniel & McDaniel, 1991; Huntington's disease, Ho, Robbins, & Barker, 2006) reduced autonomy in daily life activities (Dourado, Laks, & Mograbi, 2019; Gambina et al., 2015) and cognitive deficits (Beadle, Paradiso, & Tranel, 2018; Hoofien, Gilboa, Vakil, & Barak, 2004; Prigatano, 2010). Anosognosia for behavioural deficits has been documented in traumatic brain injured (TBI) patients, who are in general more aware of their cognitive and motor deficits (Bach & David, 2006). Importantly, anosognosia impacts negatively patient's rehabilitation outcome, social interactions and the recovery of autonomy in daily life activities (Bach & David, 2006; Fischer, Trexler, & Gauggel, 2004; O'Keeffe et al., 2007; Prigatano, Altman, & O'brien, 1990).

Three levels of awareness are distinguished (Crosson et al., 1989) : i) intellectual awareness, which refers to a patient's ability to describe their deficits or impaired functioning, without identifying the potential consequences in terms of difficulties in performing a task; ii) emergent awareness, that regards the ability to acknowledge difficulties in the moment they occur and iii) anticipatory awareness, which concerns the ability to predict the difficulties that may arise due to deficits. Emergent and anticipatory awareness represent two forms of on-line awareness since these emerge during or immediately after the performance (or attempt to perform a task). However, an off-line, metacognitive level of awareness has also been described (e.g. Dynamic Comprehensive Model of Awareness; O'Keeffe et al., 2007; Toglia & Kirk, 2000) which refers to the patients' ability to reflect on their own condition and their beliefs about themselves.

Assessments of anosognosia have been carried out in three main ways (Dockree, O'Connell, & Robertson, 2015; Gambina et al., 2015; Gasquoine, 2016). Clinical interviews help the examiner to identify severe disorders in intellectual and metacognitive areas of awareness but are not sufficient when symptoms are unclear or when these are only specific to some functions. Comparisons of self-ratings in the performance of tasks with objective test scores may also be useful as an index of performance monitoring and emergent awareness. Nevertheless, this method usually investigates awareness in specific cognitive or motor tasks but does not allow an evaluation of the patients' perception of their functional difficulties in everyday activities. For social behavioural disorders, comparisons of self-ratings with informant ratings on the same patient's performance combined with in-depth interviews may help in assessments of awareness. This method measures awareness levels in relation to evaluative judgements (metacognition) by means of information provided by caregivers who represent a general reference point. However, comparisons between the self-reports of patients and family members' reports or professional judgements are vulnerable to methodological errors and response bias (Bach & David, 2006; Prigatano, 2010). An integration of these various different procedures is thus necessary in order to overcome their specific limits. Anosognosia for social behaviour deficits is particularly difficult to investigate due to the complexity of people's social lives and the fact that these depend on cultural contexts, in addition to there being a scarcity of specific measures. Furthermore, disorders in social behaviour may be associated with other cognitive deficits (in particular, memory and executive functions) that co-occur making it difficult to distinguish awareness disorders with respect to other problems. For this reason, an in-depth assessment of awareness deficits would ideally require patients to have relatively preserved general cognitive functioning without specific deficits in memory or executive functions.

The patient described in this single case study offers a unique opportunity to carry out an in-depth investigation into awareness relating to social abilities using all of the abovementioned three assessment methodologies. Furthermore, the patient's high level of performance in cognitive domains and the concomitant presence of very specific disorders in social cognition (in particular with respect to the Theory of Mind, ToM) allowed us to advance a hypothesis regarding the existence of a form of anosognosia which is specific to the incapacity to understand others' emotions and intentions (ToM). Finally, the study of patient's MRI and DTI allowed us to perform an exploratory analysis of the neural correlates of neuropsychological symptoms.

The ToM is described as the ability to make inferences about others' mental states and use them to understand intentions and predict others' behaviour (Baron-Cohen et al., 1994; Premack & Woodruff, 1978). Several studies have shown that ToM deficits are frequent after TBI (Dal Monte et al., 2014; Geraci, Surian, Ferraro, & Cantagallo, 2010; Henry, Phillips, Crawford, Theodorou, & Summers, 2006) and there is a vigorous debate on whether these represent a specific disorder or are the consequence of other cognitive deficits, in particular executive functions (Havet-Thomassin, Allain, Etcharry-Bouyx, & Le Gall, 2006; Henry et al., 2006; Samson, Apperly, Kathirgamanathan, & Humphreys, 2005; Yeh, Tsai, Tsai, Lo, & Wang, 2017). Neuroanatomical data indicate the key regions for ToM deficits as being the medial prefrontal cortex (Gallagher & Frith, 2003; Geraci et al., 2010; Sebastian et al., 2012) and the temporo-parietal cortex (McDonald, 2013; Saxe & Kanwisher, 2003). Furthermore, the inferior frontal cortex has been found to be associated with social deficits in TBI (e.g. Cicerone, 1997; Dal Monte et al., 2014), although recent studies have emphasised the role of white matter connectivity, in particular of long-range hemispheric connections such as the corpus callosum, the fornix and the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (Genova et al., 2015; McDonald, Rushby, Dalton, Allen, & Parks, 2018). Neuroanatomical data regarding brain connectivity patterns in self-awareness deficits in social cognition are meager (Ham et al., 2014; Schmitz, Rowley, Kawahara, & Johnson, 2006) and to date, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no investigations into the neural correlates for anosognosia for ToM deficits. Therefore, bearing in mind that no conclusions can be drawn from the anatomical study of a single case, we performed an MRI/DTI exploratory analysis of the neural correlates of the patient's neuropsychological symptoms.

The aims of the present study are: i) the neuropsychological identification of specific deficits in ToM deficits and awareness of these, by means of distinguishing and separating ToM disorders from co-occurring executive frontal deficits and ii) an exploratory anatomical investigation of the neural correlates for anosognosia for ToM deficits in terms of both direct lesions and disconnections. In addition, the results from this single case study were compared with information resulting from a meta-analysis of the literature on the subject of deficits relating to ToM and their correlations with executive functions, and a revision of the literature on anosognosia for behavioural disorders in TBI.

2. Methods

2.1. Case Report

AP is a 55 years old man who lives with his family and works as a sales representative. He has 12 years of education. As a consequence of a traumatic brain injury following an accidental fall (initial Glasgow Coma Scale = 7), he suffered multiple lesions in the left fronto-basal areas and bilaterally in the temporo-basal regions. Pharmacological sedation was maintained for 10 days. Post-traumatic amnesia lasted around 40 days after the lesion onset. A first neuropsychological assessment (executed two months after the lesion onset) excluded the presence of deficits in memory, reasoning and executive functions (Table 1).

Table 1.

AP's scores in the neuropsychological assessments carried out at two and four months after the lesion onset. Where the tests do not give the methods of score correction for their subtests, row scores are reported with the score range in brackets. The percentiles are reported for the tests where there are not cut-off values. 1,2 Sartori et al., 1997; Colombo et al., 2002. 3 Caffarra, 2003. 4 Spinnler & Tognoni, 1987. 5 Della Sala e coll., 2003. 6,7 Wilson et al. 1996; Antonucci et al. 2010. 8 Cantagallo et al., 1997. 9 Zimmermann, B. Fimm, 2012. 10 Luzzatti, Willmes, De Bleser, 1996. 11 Vers. Papagno et al., 1995. 12 Carlesimo et al., 1995. 13 Novelli et al., 1986. 14 Monaco, 2013. 15 Carlesimo et al., 1996. 16 Wilson et al., 1989. 17 Valgimigli et al., 2010. 18,19 Shallice, 1982; Allamanno et al. 1987. 20 Cattelani et al., 2011. 21 Sohlberg & Geyer, 1986.

| Cut-off/(score range) | 2 months (score/ percentile) | 4 months (score/ percentile) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General functions | |||

| Short intelligence test (Test di intelligenza breve, TIB; 1,2) | |||

| Total score | ≥93.1 | 103.63 | |

| Verbal Intelligence Quotient estimate | (0-110) | 103.31 | |

| Performance Intelligence Quotient estimate | (0-110) | 103.95 | |

| Raven - Progressive matrices 38 3 | ≥20.63 | 42 | |

| Verbal judgement 4 | |||

| Total | ≥32 | 36,75 | |

| Differences between concepts | (0-15) | 12 | |

| Proverbs | (0-15) | 3 | |

| Identification of absurdity | (0-15) | 12 | |

| Classifications | (0-15) | 15 | |

| Cognitive Estimation Task (CET 5) | |||

| Total errors | <18 | 10 | |

| Bizarre answers | <4 | 4 | |

| Temporal judgement (Behavioural Assessment of Dysexecutive Syndrome BADS; 6,7) | (0-4) | 3 | |

| Attention | |||

| Test of Everyday Attention (Test dell'attenzione nella vita quotidiana, TAQ; 8) | |||

| Visual Elevator Test - Accuracy | >10° | 7 (25°) | |

| Visual Elevator Test - time (mean in sec.) | >10° | 5.83 (15°) | |

| Test of Attentional Performance (TAP; 9) | |||

| Go/No-go | >30 | 52 | |

| Divided attention (visual) | >30 | 47 | |

| Divided attention (auditory) | >30 | 50 | |

| Language | |||

| Aachener Aphasia Test (AAT; 10) | |||

| Token Test | ≤7 | 6 | |

| Denomination | ≥104 | 111 | |

| Repetition | ≥142 | 146 | |

| Comprehension | ≥108 | 117 | |

| Written language | ≥81 | 90 | |

| Metaphors & Idioms 11 | |||

| Metaphors | ≥13 | 26.75 | |

| Idioms | ≥13 | 25.50 | |

| Phonemic Fluency 12 | ≥17.35 | 17 | |

| Semantic Fluency 13 | ≥25 | 36 | |

| Memory | |||

| Digit Span 14 | |||

| Forward | ≥4.26 | 4.83 | |

| Backword | ≥2.65 | 2.79 | |

| Corsi span 4 | ≥3.75 | 4.75 | |

| Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test 12 | |||

| Immediate | ≥28.53 | 29 | |

| Delayed Recall | ≥4.69 | 5.5 | |

| Story recall 4 | |||

| Total (cut-off) | ≥4.75 | 13.53 | |

| Immediate | (0-8) | 6.9 | |

| Delayed | (0-8) | 6.3 | |

| Rey Figure 15 - Delayed Recall | ≥6.33 | 11.75 | |

| Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test 16 | ≥9 | 9 | |

| Executive Functions | |||

| Response Inhibition | |||

| Stroop test 17 | ≥42 | 11.94 | |

| Rule shift cards test (BADS) | (0-4) | 3 | |

| Planning | |||

| Action program test (BADS) | (0-4) | 3 | |

| Key search test (BADS) | (0-4) | 2 | |

| Zoo map (BADS) | (0-4) | 3 | |

| Six elements (BADS) | (0-4) | 3 | |

| Tower of London 18,19 | ≥9.5 | 26 | |

| Elithorn's Perceptual Maze Test- Short form 4 | ≥13.5 | 15.5 | |

| Modified Five points 20 | ≥23.83 | 24.5 | |

| Frontal functions assessment | |||

| BADS -total score 6,7 (cut-off ≥14) | ≥14 | 17 | |

| Behavioural Assessment of Executive Functions 21 | |||

| Planning | (0-35) | 29 | |

| Time planning and contraints | (0-20) | 20 | |

| Self control | (0-30) | 13 | |

A more in-depth assessment was carried out when we met AP, 4 months after the lesion onset. As shown in Table 1, the patient did not show any deficits in general cognitive functions, language, attention, executive functions. His score was under cut-off only in the subtest of Proverbs (where his answers showed reduced abstract processing of the proverb contents) and at the lower limits in Phonemic Fluency and in Bizarre responses during verbal judgment task.

In contrast with his cognitive capacities which for the most part have been preserved, certain behavioural symptoms had emerged, as manifested by the patient's difficulties in social relations, both in terms of his ability to comprehend others' feelings and in his responses to social inputs. However, when he was in formal contexts, he did not have any difficulties in respecting the rules of social behaviour (in terms of what is permitted and what is prohibited) and he was not disinhibited or inappropriate with other people. Nevertheless, he appeared to be totally incapable of understanding the thoughts and emotions of others. This information was all collected during interviews with the patient's partner, who reported, for example, that when he was sedated, he could not understand why she cried when remembering the first days of his illness. When she tried to explain her anxiety that he didn't recover, he got angry saying she didn't understand anything. AP's behaviour often appeared to be anaffective, inappropriate or even sometimes verbally aggressive in familiar and intimate contexts. Furthermore, when incomprehension or conflicts emerged, he had the tendency to impute all the responsibilities to others, also when the conflict arose with the young child. In addition, he was not able to analyse or criticise his own attitudes and behaviour or to understand the feedback in response to his actions. Even when there was social feedback which specifically referred to his difficulties, he continued to deny that he had problems. These symptoms suggested the potential presence of a deficit relating to the Theory of Mind (ToM). For this reason, a specific assessment of ToM was carried out. In addition, in order to verify AP's awareness of his difficulties, a specific battery of tests for the evaluation of Anosognosia for ToM deficits was devised.

The procedure for this study (which is part of a larger study on anosognosia) was approved by the local ethics committee (CEP Prot. 47566), and informed written consent was given by the patient.

2.2. The assessment of the Theory of Mind (ToM)

Four aspects of the ToM were investigated by means of specific tools (with validation in in the Italian population). These investigated: i) emotion recognition; ii) reading of the mind; iii) social comprehension and iv) identification of moral/conventional distinctions (see Table 2). Even though the patient did not show comprehension or memory deficits (Table 1), the texts of the stories presented in the verbal tasks were always left near the patient.

Table 2.

Results of the clinical assessment of Theory of Mind. 1 Baron-Cohen et al., 2001. 2 Prior et al., 2003. 3 Stone et al., 1998.

| Theory of Mind Assessment | Cut-off | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition of emotions | ||

| Reading the Mind in the Eyes 1 (36) | ≥ 15 | 14 |

| Emotion attribution task 2 (58) | ≥ 41 | 17 |

| Sadness (n.10) | ≥ 6 | 2 |

| Fear (n.10) | ≥ 8 | 5 |

| Uneasiness(n.12) | ≥ 8 | 0 |

| Disgust (n.3) | ≥ 2 | 1 |

| Happiness (n.10) | ≥ 10 | 7 |

| Anger(n.10) | ≥ 6 | 2 |

| Envy (n.3) | ≥ 1 | 0 |

| Reading of Mind | ||

| Faux Pas Test3 | ||

| - Faux Pas Stories (60) | 48.15% | |

| - Control questions in Faux Pas Stories (20) | 95% | |

| - Control Stories (20) | 60% | |

| - Control questions in Control Stories (21) | 95.24% | |

| Theory of Mind Test (ToM; 2) (13) | 13 | 7 |

| - First order beliefs (7) | 3 | |

| - Second order beliefs (6) | 4 | |

| Social comprehension | ||

| Comprehension of social situations (ToM, 2) (115) | 73 | |

| - Identification of correct behaviour (15) | ≥ 13 | 11 |

| - Identification of violations (25) | ≥ 22 | 19 |

| - Gravity of violations (75) | ≥ 45 | 43 |

| Moral/Conventional distinction (ToM, 2) | ||

| - Moral Behaviour not allowed (6) | ≥ 6 | 6 |

| - Gravity of moral violations (60) | ≥ 39 | 58 |

| - Moral Behaviour not allowed (without explicit rule) (12) | ≥ 11 | 12 |

| - Behaviour not allowed by conventions (6) | ≥ 5 | 5 |

| - Gravity of violations in conventional behaviours (60) | ≥ 20 | 49 |

| - Behaviour not allowed by conventions (without explicit rule) (12) | ≥ 6 | 10 |

Emotion recognition

The Reading the Mind in the Eyes test (Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, Raste, & Plumb, 2001; Italian validation, Meneghini, 2005) was administered. In addition, the lesser known Emotion Attribution task (Prior, Marchi, & Sartori, 2003) was used. In this latter test, 58 everyday situations are verbally presented (e.g. “Simone's paintings arrived last in the competition”) and a judgement about the main agent's emotions is requested (e.g. “How did Simone feel in this situation?”). In this way the patient's ability to identify seven emotions (sadness, fear, uneasiness, disgust, happiness, anger and envy) was investigated (1 = correct response, 0 = error).

Reading of the Mind

We used the version for adults of the Faux Pas Test (Gregory et al., 2002; Stone, Baron-Cohen, & Knight, 1998) and the Italian Theory of Mind test (Prior et al., 2003). As in the case of Emotion Attribution task, this latter task also involves short stories concerning daily life events and the patient is asked to give his/her opinion regarding the thoughts of the main character (e.g. Mark and Philip are playing together, and they have turned the table upside down. When their mother comes in, she laughs and says: “What are you doing?” “This table is a pirate ship”, Philip says, “and you'd better get on board before you drown, because now you are in the middle of the sea!”). Patients are asked to identify what the characters of the short story thinks or what the real meaning of their statements is (1 = correct response, 0 = error). Both first and second order beliefs are investigated.

Social comprehension

In order to evaluate AP's capacities to analyse social situations, the Social Situations test (part of the ToM test, Prior et al., 2003) was administered. 25 stories concerning a protagonist who acts in a variety of social contexts were presented (e.g. A baseball player is late for an important match and when he arrives, he realises he has forgotten his uniform. He does not have time to go back home and get it, so he enters the stadium wearing his underwear). The patient has to judge whether the character's behaviour is or is not appropriate (1 = correct response, 0 = error), and assess the gravity of any potential violation (4 point-scale, 0 = normal, 1= a bit strange, 2 = moderately strange, 3 = very strange).

Moral/Conventional distinction

The capacity to understand when certain behaviour violates social or moral conventions was investigated by means of the Moral/Conventional test (part of the ToM test; Prior et al., 2003). 12 situations are presented including various types of conventional (e.g. during a lesson, a boy stands up and goes out of the classroom without asking for permission) and moral (e.g. a boy shouts ridiculous words to a lame man) contexts. Four questions are asked: (i) “Is this correct behaviour?”; ii) “How bad is this behaviour, on a scale from 0 to 10?”; iii) “In a country where there are no regulations, would this behaviour be right?” and iv) “If the teacher allowed everybody to behave like this, would this behaviour be right?”. By means of this last question, it is possible to ascertain whether the patient's judgement is conditioned by the presence of external rules or oriented by an internal evaluation of the situation in terms of both moral and conventional violations (presence of moral, convention, with or without rules :1 = correct response, 0 = error; gravity of violations: scale 0-10).

2.3. ToM and executive functions

The only tests where AP's scores were at cut-off or pathological were Phonemic Fluency, Proverbs and verbal judgments (bizarre responses). For this reason and as there is a debate in the literature on the subject regarding whether or not disorders in ToM are associated with deficits in executive functions, a meta-analysis of the literature was conducted in order to verify a potential association of the two deficits. This was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009). A comprehensive systematic search of the literature was performed using PubMed, ScienceDirect and Scopus for articles published between January 1996 and March 2018, entering the following keywords: “theory of mind” AND “deficits”; “theory of mind” AND “brain damage”; “theory of mind” AND “brain injury”; “theory of mind” AND “TBI” “mentalizing” AND “brain damage” “mentalizing” AND “brain injury”. After the removal of doubles and non-English articles, 1,890 potentially relevant abstracts were identified. A scan of the titles and abstracts was performed according to the inclusion criteria, namely the presence of: i) adult TBI population, ii) psychometric measures of Theory of Mind (ToM) and Executive Functions (EF) and iii) at least one measure of correlation between Theory of Mind and Executive Functions. Articles reporting data on patients in developmental age or including mixed aetiologies or neurodegenerative/ psychiatric disease were excluded. Furthermore, book chapters, commentaries, reviews, meta-analyses, single-case reports and research conducted on animals were not included. A third full-text assessment selection was performed on the 48 articles identified as being eligible, according to the previous selection phase. At the end of this procedure, seven studies met all the required criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (see SM1 for a schematic description of the procedure).

2.4. Anosognosia for Deficits in Theory of Mind (AToM)

An investigation was carried out in order to establish the presence or otherwise of anosognosia for deficits in the Theory of Mind (AToM). This was done by means of integrating the procedures suggested for the assessment of other forms of anosognosia (Dockree et al., 2015; Gambina et al., 2015; Gasquoine, 2016) after a systematic revision of the literature (PRISMA guidelines, Moher et al., 2009) regarding studies on anosognosia for behavioural deficits (SM2).

In particular, to assess intellectual and metacognitive levels of awareness, a direct clinical interview was done to gain information regarding the patient's symptoms and a comparison was made between the self-ratings of the patient and the ratings of the informants (in this case, the patient's partner and his neuropsychologist). In addition, in order to investigate on-line, emergent awareness, a comparison was made between the patient's pre- and post - task self-ratings for tasks in which the patient had failed.

Clinical Interview

The interview (SM3) started with a general question about the state of AP's health and the circumstances in which the TBI occurred (“How are you?” “Why are you participating in a rehabilitation programme?”). Then, some more specific questions were asked regarding his cognitive and social abilities (e.g. “Do you have any problems with cognitive (e.g. language, memory, attentional/social) abilities?” “Have your capacities to interact with other people changed since the injury?” “Are you able to put yourself in other people's shoes as well as you could before the injury? Can you understand the emotions of others as well as you could before the injury?”). The patient was also asked to comment on what his doctors had said (e.g. “The doctor tells me that you have some problems in understanding others' feelings and interacting with other people. What do you think?”). Finally, a question about motor deficits was asked to conclude the interview (“Do you have any motor problems as a result of your fall?”). Comparison between self versus informant ratings. Two versions of the same questionnaire were administered to AP and the informants in order to compare their judgements regarding his current difficulties. The Patient Competency Rating Scale (PCRS, (Prigatano, 1996) Prigatano et al., 1986; Italian version, Zettin & Rago, 1995) is a self- evaluation questionnaire regarding motor, emotional and behavioural competencies. With reference to a 5-point scale, patients are asked to quantify the degree of difficulty they have in executing 30 different actions (with 1 = very easy, 3 = quite easy, 5= some difficulties, 7 = very difficult, 9 = impossible). The questions regard daily life activities (9 items), cognitive functions (7 items), social behaviour (8 items) and emotions (6 items). A comparison between the patient's scores and those of the informants was made. The same procedure was followed for the Disexecutive Questionnaire (part of the BADS battery; Burgess, Alderman, Evans, Emslie, & Wilson, 1998), but in this case the patient's ratings were only compared with those of the neuropsychologist (information from the partner was not available for this questionnaire). In this interview, 20 items assess the frequency with which some difficulties arise (5-point scale, form 0 = never to 4 = very often). 6 items assess emotions/personality, 2 relate to motivation, 7 to behaviour and 5 to cognition.

Comparison between the self-ratings of the patient relating to his performance and objective test scores

A new tool was devised in order to assess emergent awareness with reference to AP's capacity to adjust his beliefs regarding his abilities during the execution of specific tasks and/or after feedback on his performance (SM4). 10 ToM and Emotion Attribution situations were selected from the Battery for Social Intelligence test (Prior et al., 2003) and 6 cognitive tasks (person's names recall, digit and verbal short-term memory, attention, verbal fluency and response inhibition) were administered. Each trial started with a question regarding the patient's judgement concerning his ability to do a specific task (“How difficult do you think it is for you to……?” 5-point scale; 1= impossible; 2 = very hard for me; 3 = quite difficult; 4 = I can do it quite well; 5 = I can do it perfectly). The patient was then requested to perform the task and afterwards he was given feedback on whether his response was correct or not (e.g. “You have recalled 5 words”, or “The correct response was ....”). In this way, a comparison between the patient's judgement and his performance was made. The patient was then asked again about his capacity to do the task. A comparison between the pre- and post-task judgements was made in order to obtain an index of emergent awareness (Moro, Scandola, Bulgarelli, Avesani, & Fotopoulou, 2015).

2.5. Data analysis

The cut-offs of the validated Italian version of in the neuropsychological tests were used (Table 1). The PCRS scores were dichotomised into a binomial variable where 1 indicated the presence of difficulties (PRCS scores ≥5) and 0 the absence of difficulties (PRCS scores ≤ 3). The BADS Disexecutive subtest scores were dichotomised with 1 when the scores were greater than 0 (indicating the presence of difficulties), or 0 (indicating the absence of difficulties). In this way, the frequencies of the patient's difficulties as reported by himself, his partner (only for the PRCS questionnaire) or his therapist were calculated for daily life activities, cognitive functions, social behaviour and emotions for the PCRS scale, and the BADS Disexecutive subtest investigated cognitive, behavioural, motivational and emotional aspects. These frequencies were then compared by means of χ2 tests, using Cramer's V as Effect Size (small V = [0 - 0.3), medium V = [0.3 - 0.6), large V = [0.6 - 1); Cohen, 1988).

2.6. Anatomical study

Imaging Data Acquisition

In addition to the CT scan conducted for routine clinical purposes, the patient underwent radiological 1.5 T MRI (Siemens MagnetomAera) examinations of T1, T2 and FLAIR to obtain an optimal identification of the lesion. In addition, a standard DTI tractography was carried out by means of the acquisition of 30 diffusion-weighted volume directions and 10 volumes with no diffusion gradient (B0), repeated twice to increase the signal-to-noise ratio, with a b-value of 1000 s/mm2. The images were obtained at a repetition time of 6000 ms and an echo time of 97 ms. The voxel size corresponded to 2.5x2.5x3.5 mm2, the slice thickness and the FOV size was 2.5 mm and 250 mm, respectively.

Lesion Analysis

The lesion drawing was performed according to a consolidated methodology (Moro et al., 2016; see SM5 for details) on the CT scan image where the lesion was more visible than in the MRI (de Haan & Karnath, 2018). Then, in order to identify the brain structures affected by the lesion, we compared AP's lesions and the AAL brain atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002).

White matter tracts lesion analysis

In order to identify the white matter tracts affected by the lesion, we took advantage of an advanced technique for lesion symptom mapping (Tractotron, as part of the BCBToolkit; Foulon et al., 2018). The lesion drawing of the patient was used as the ROI to track the white matter fibres from a healthy subjects dataset (Rojkova et al., 2016), setting the 50% overlap maps for the localisation of the lesions (Dalla Barba et al., 2018; Thiebaut de Schotten et al., 2014). The severity of the disconnection is established by the proportion of the tracts that are disconnected. Furthermore, from the patient's lesion a percentage overlap map was produced that took into account the inter-individual variability of tractography in the healthy subjects dataset using the Disconnectome maps tool (part of the BCBToolkit, Foulon et al., 2018), in order to obtain the patient's map of disconnection. In the resulting disconnectome map, the voxels show the probability of disconnection from 0 to 100% (Thiebaut de Schotten et al., 2015). Tractography Reconstruction. In order to confirm the white matter tract disconnections resulting from the Tractotron, we performed a tractography of the diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) data. The DWI data were corrected for subject motion and eddy current induced geometric distortions by means of Explore DTI (http://www.exploredti.com; Leemans, Jeurissen, Sijbers, & Jones, 2009). Hence, a computation of diffusion tensors and the whole-brain deterministic tractography was performed using StarTrack software (http://www.natbrainlab.com), with a fractional anisotropy (FA) above a threshold of 0.2 and an angle threshold of 45°. Tracts dissection were performed using Trackvis (http://www.trackvis.org/), in order to allow for an inter-hemispheric comparison of lesioned tracts and their spared homologues in the contralesional hemisphere (Thiebaut de Schotten et al., 2014). Details of the tract reconstruction are described in SM6.

3. Results

3.1. Deficits in Theory of Mind (ToM)

AP's results in the tests assessing ToM deficits are shown in Table 2.

Emotion recognition

The patient's scores confirmed his difficulties in identifying others' emotions when presented both in visual (Reading the Mind in the Eyes) and verbal (Emotion Attribution task) modalities. He was occasionally able to recognise happiness and fear, but his scores were very low for sadness, uneasiness, anger, disgust and envy. This was also confirmed by a qualitative inspection of the responses to the questions regarding emotions in the Faux Pas test, where he only responded correctly to two of the 10 questions.

Reading of Mind

AP understood the short stories without any problems (control questions), both when the faux pas was present and when it was absent. In addition, it is interesting to note that he always identified the Faux Pas (Identification 10/10) and the agent (10/10), but he failed to understand the character's intention (5/10) and the emotions induced by the action (2/10). Furthermore, the results also showed an overestimation of inappropriate behaviours with wrong identification of the Faux Pas in the control stories. The Test of Theory of Mind (Prior et al., 2003) confirmed the presence of deficits in identifying both first and second order beliefs.

Social comprehension

Results show that comprehension of social situations was problematic for AP, who failed in the identification of both correct behaviours and the violation of social rules, and when judging the gravity of a violation. In apparent contrast with this result, AP's scores relating to Moral/Conventional distinction were all above cut-off. It is, however, worth noting that there were no control trials in this task (i.e. where the conventional or moral rule is not violated) and this meant that it was not possible for us to exclude a tendency to overestimate the violation, as in fact occurred in the case of the Control stories for the Faux Pas test. In support of this hypothesis, AP tended to consider all the different violations as being equally serious, without a distinction of gravity (e.g. during a lesson a boy starts talking with another boy: gravity of violation = 9; a boy beats another boy in the yard: gravity of violation = 9).

Considering these data and, conversely, the good performance in the neuropsychological tests, we thus consider the AP's deficit in ToM as very specific and not a mere consequence of other cognitive symptoms. The meta-analysis of the literature on the relations between ToM and FE that was carried out supports this hypothesis, showing that the two deficits are not correlated indicating that the patient's failure in two specific tasks (Proverbs and Fluency) do not explain his severe symptoms relating to ToM deficits.

3.2. Anosognosia for Deficits in Theory of Mind

Clinical Interview

During the interview, AP admitted that he was having some problems with language, in particular recalling some words and names and he complained that he was suffering from general stiffness in his movements. Nevertheless, he denied that he had any social impairments, declaring that he was able to understand the thoughts and emotions of other people just as he could before the injury. He also stated that he always paid attention to what other people were feeling and that he understood his relatives' emotions from their voices, facial expressions and behaviour. When asked to give an opinion about what the doctor had said regarding his case, he responded that after the trauma he probably had some problems but that now these had, however, been totally resolved.

Comparison between self versus informant ratings

The PCRS scores indicate that AP was aware of his difficulties in performing cognitive tasks (χ2(2) =2.33, p = 0.31, V = 0.33) and emotional responses (χ2 (2) =4, p = 0.14, V = 0.47), while he overestimated his difficulties in carrying out daily-life activities (χ2(2) =6.75, p = 0.03, V = 0.5). In contrast, he was anosognosic for his disorders in social behaviour where his scores were significantly different from the informants' ones (χ2(2) =7.47, p = 0.02, V = 0.56). Crucially, the results show that he was unaware in the items regarding ToM (e.g. “How much of a problem do I have in realising when something I have done or said does irritates other people?”, “How much of a problem do I have in communicating my affection to other people?”, “How much of a problem do I have in accepting criticism?”), but not in items regarding his abilities in behavioural control (e.g. “How much of a problem do I have in controlling laughter?” “How much of a problem do I have in behaving properly with other people?”).

The BADS Disexecutive Function scores indicate that AP was aware of the cognitive (χ2(1) =1.67, p = 0.20, V = 0.41), behavioural (χ2 (1) =0.29, p = 0.59, V = 0.14) and motivational disorders (and both the therapist's and AP's scores were equal to 0 out of 2). There was a statistically significant difference in the emotional scores (χ2(1) =5.33, p = 0.02, V = 0.67), with the therapist reporting that AP had emotional problems in 5 out of 6 items, while AP reported 1 item out of 6.

Comparison of pre- and post-task judgements

The results shown in Figure 1 regarding the modulation of AP's judgements before and after performing a task, show that the he tended to persist in his high evaluation of what he was capable of regardless of the feedback he was given about his failures. Although there were too few items to make any statistical comparisons, the scores indicate that AP was more aware of his difficulties in cognitive than in social functions. In addition, in the cognitive tasks where he failed, the scores relating to his assessments of his proficiency were lower than in ToM and Emotion Attribution tasks. In contrast, he thought he was able to do ToM tasks without any problems and did not change his judgements after failing, despite being told that he had failed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

a) Patient Competency Rating Scale. All scores > 5 were transformed into 1 = presence of problems, while 0 = absence of problems were divided per evaluator and component of competency. b) Dysexecutive Questionnaire. Mean and standard deviation of the dichotomised scores for the Dysexecutive Questionnaire divided by evaluator and component. All scores >0 were transformed into 1 = presence of dysexecutive behaviours, while 0 = absence of dysexecutive behaviours. c) Comparison of pre- and post-task judgements. The patient's self-evaluations before and after the execution of each of the ToM/Emotion Attribution and Cognitive tasks, divided in Correct/Incorrect responses, and Tom/Cognitive tasks. * = p<0.05.

3.3. Neuroanatomical results

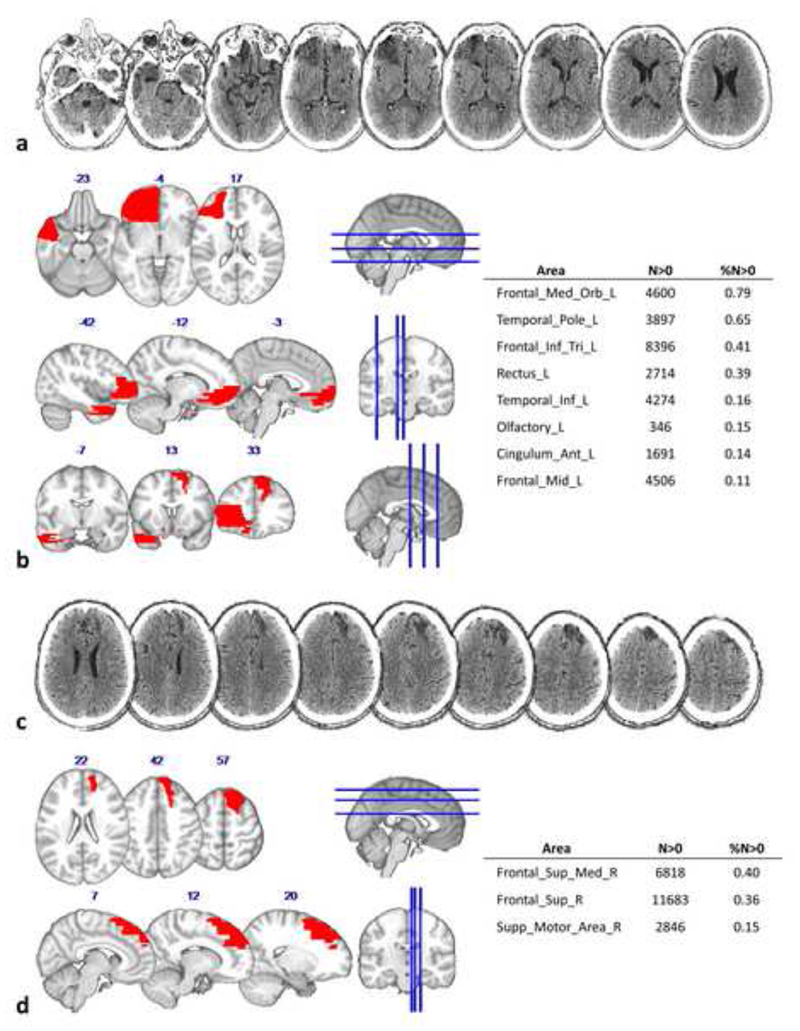

The comparison between AP's lesions and the AAL template is shown in Figure 2. In the left hemisphere, the lesion extends in the inferior, orbital and middle frontal lobe, in temporal inferior and anterior cingulate cortex. In the right hemisphere the lesion is more dorsal, involving the superior and middle frontal cortex and the supplementary motor cortex.

Figure 2.

The image and delineation relating to AP's lesion. a) Axial view of the CT scan showing the left hemisphere damage, the last slice (on the extreme top right) represent the dorsal limit of the lesion in the left hemisphere. b) Axial (up), sagittal (middle) and coronal (bottom) view of the left hemisphere lesion drawing (on the coronal sections, also the right lesion is appreciable) registered onto the MNI152 template. The table on the right half of the figure describes the number of voxels (N>0) and the percentage volume (%N>0) affected by the lesion for each left hemisphere grey matter structure. c) Axial view of the CT scan showing the right hemisphere damage. d) Axial (up) and sagittal (bottom) view of the right hemisphere lesion drawing registered onto the MNI 152 template. The table on the right describes the number of voxels (%N>0) and the percentage volume (N>0) affected by the lesion for each right hemisphere grey matter structure.

Figure 3a shows the disconnection of the left frontal areas, both within the frontal lobe and with respect to other more distant areas. In fact, the lesion affects 68% of the Fronto Marginal tract (FMT), 55% of the Uncinate, 44% of the Fronto Orbitopolar tract (FOP) and 25% of the Fronto-Striatal tract (FST). Long intrahemispheric connection tracts are also damaged, in particular the third branch of the Superior Longitudinal Fasciculus (SLF III, 13%), the anterior Cingulum (7%), the Frontal Superior Longitudinal tract (FLS, 24%), the Inferior Longitudinal Fasciculus (ILF, 11%) and the Inferior Fronto-Occipital fasciculus (IFOF, 30%).

Figure 3.

White matter disconnections in AToM. a) On the left, lateral and medial view of the left hemisphere and its damaged tracts. Cing. = cingulum; IFOF = inferior fronto occipital fasciculus; ILF = inferior longitudinal fasciculus; FOP = fronto-orbitopolar tract; FST = fronto striatal tract; SLF III = third (ventral) branch of the superior longitudinal fasciculus; FMT = fronto marginal tract; Unc = uncinate. In the centre, ventral view of the left (up) and right (bottom) hemispheres and the damaged association fibres. CC = corpus callosum. On the right, lateral and medial view of the right hemisphere and its damaged tracts. SLF I = first branch (dorsal) of the superior longitudinal fasciculus; FAT = frontal aslant tract; FSL = frontal superior longitudinal tract. b) Tract reconstruction from the patient's Diffusion Weighted Imaging. The colour bar represents the Fractional Anisotropy level. dFornix = dorsal Fornix; aFornix = anterior Fornix. c) Map of the probability of tract disconnection computed for the patient's lesion. The colour bar represents the disconnection probability ranging from 80% to 100%.

In the right hemisphere, the tracts affected by the lesion are the Frontal Aslant tract (FAT, 24%), the Frontal Superior Longitudinal tract (FSL, 24%) and the Fronto-Striatal tract (FST, 11%). The lesion also involves long intra-hemispheric tracts, such as the first branch of the Superior Longitudinal Fasciculus (SLF I,14%) and the anterior Cingulum (6%).

Finally, the commissural inter-hemispheric connections that are affected by the lesion are the Fornix (15%), and the Corpus Callosum (7%).

The tractography (Figure 3b) confirmed the damage to the connections of the left fronto-orbital regions (FOP and FMT) and between the left medial temporal area and the mammillary bodies (via the Fornix). A reduced FA was found for the left Uncinate, IFOF, SLF III, and IFL with respect to their right homologues, and for the right FSL, but not for the right FAT, when compared to its left homologue. Unfortunately, it was not possible to reconstruct the SLF I due to the image acquisition parameters available, while for the Cingulum, the FST and the Corpus Callosum the inter-hemispheric comparison was not possible.

The disconnectome analysis (Figure 3c) confirmed a high probability of disconnection of the left fronto-orbital regions from the anterior temporal lobe, and from the occipital cortex, while the pre-SMA is disconnected from the striatum. A high probability of disconnection is shown between the superior frontal and superior parietal gyri. The medial temporal lobe is disconnected from the occipital lobe and from the mammillary bodies and the hypothalamus.

Within the right hemisphere, the results show a high probability of disconnection i) of the fronto-orbital areas from their left homologues; ii) between the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and the temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) and iii) between the pre-SMA and the IFG and the striatum, respectively.

4. Discussion

Although we are aware that a single case does not allow one to draw any definite conclusions regarding a deficit as complex as anosognosia, the findings relating to our patient may provide a contribution to the long-standing debate on self-awareness in social behaviour. The interest aroused by the patient studied here was the result of various factors. Firstly, there was the specificity of his symptoms which were not attributable to general behavioural problems but were specific for ToM. Another point of interest concerns the question of the specificity of ToM deficits with respect to other cognitive functions, since at the moment of the assessment, AP did not show severe cognitive disorders. We will briefly address these points before moving on to the discussion regarding the novel findings resulting from this study, that is, the potential existence of a specific form of anosognosia for the Theory of Mind.

4.1. Deficits in TOM

Personality changes and lack of self-control in social exchanges are common after brain damage to the frontal network. Disinhibited behaviour, inappropriate jokes, vulnerability to deception and aggressive or sexually inappropriate behaviour have all been described (Berlin, Rolls, & Kischka, 2004a; Channon, Pellijeff, & Rule, 2005; Stone et al., 1998). Along with these symptoms, difficulties in understanding the intentions and emotions of others (Spikman et al., 2013) may also occur. Disorders in the ToM have been found both in developmental phases (Baron-Cohen, Leslie, & Frith, 1985; Hughes & Leekam, 2004; Lockwood, 2016) and adulthood (Apperly, Samson, Chiavarino, & Humphreys, 2004; Dermody et al., 2016; Stone et al., 1998). In cases of TBI, ToM may be compromised by various other deficits, for example memory disorders that prevent the patient from using his/her knowledge of their social world (i.e. what they know about other people or what type of behaviour is or is not acceptable in a specific context). This makes it difficult for the patient to orient their answers and anticipate the future intentions of others (Gallagher & Frith, 2003). Moreover, specific deficits in perspective taking can make it impossible for a patient to understand information that other people are aware of and thus also the beliefs that may derive from them (Frith & Frith, 2006). One might in this way consider that ToM deficits are not specific but are the mere consequence of disorders in other cognitive functions.

Our neuropsychological assessment of AP excluded the possibility that his ToM deficits had emerged as a result of other cognitive problems since at the moment of assessment he did not present with problems relating to attention, memory or language. Furthermore, with respect to working memory and executive functions, his scores were above cut-off (except for Proverbs and Phonemic Fluency), indicating that this did not contribute to ToM deficits. This is particularly interesting as there is a debate over whether the ability to infer others' mental states is specific or is the result of more general inferential abilities. In the latter hypothesis, working memory (Bibby & McDonald, 2005; Muller et al., 2010; Turkstra, Norman, Mutlu, & Duff, 2018) and executive functions (Bibby & McDonald, 2005; Dal Monte et al., 2014; Henry et al., 2006; Milders, Ietswaart, Crawford, & Currie, 2006; Yeh et al., 2017) might play a crucial role. However, our meta-analysis of the literature did not result in any confirmation of a relationship between executive functions and ToM. In fact, although the studies on this topic are extremely heterogeneous in terms of methods and the grouping of patients, the results indicate that there is no relationship between executive functions and ToM deficits, supporting the hypothesis that the two cognitive functions refer to two different constructs, with levels of independency.

Crucially, there was no evidence of other relevant disorders in AP's behaviour, such as disinhibition or lack of control, but his social deficits were directly associated with his inability to understand others. He failed in all of the ToM tasks, although he demonstrated a good level of comprehension of contexts and his knowledge of moral and conventional rules was good even though his opinions were a little strong at times. This supports the possibility that ToM deficits may be very specific (Bibby &McDonald, 2005).

Another matter of debate is the distinction, in terms of symptoms and neural correlates, between the affective and cognitive aspects of the ToM (Abu-Akel & Shamay-Tsoory, 2011; Lockwood, 2016; Shamay-Tsoory & Aharon-Peretz, 2007). Our patient showed deficits in tests assessing both the recognition of emotions (the Reading the Mind in the Eyes and Emotion attribution tasks) and reading the mind of others (the Faux Pas and Theory of Mind tests and social comprehension), indicating a general problem in understanding others' mental states.

Our anatomical investigation supports the clinical diagnosis regarding AP's ToM deficits. In fact, the lesions in the left hemisphere extend to the connections between the TPJ and the IFG via the SLF III. These structures are part of the mentalising system and any damage to this area leads to an impairment in the ability to take a third person perspective (Frith & Frith, 2008). The disconnection of temporal areas has been shown to lead to difficulties in understanding other's emotions and accessing previous knowledge about other people's beliefs and social contexts (Gallagher & Frith, 2003). Other crucial areas for ToM are the medial frontal cortices that are also lesioned and/or disconnected in AP's case. These areas play a role in the attribution of intentions (Gallagher, Jack, Roepstorff, & Frith, 2002). The disconnection of the fronto-occipital and temporo-occipital connections via the IFOF and the IFL may explain support the AP's failure to process facial expressions and behave appropriately in social interactions (Im et al., 2018; Philippi, Mehta, Grabowski, Adolphs, & Rudrauf, 2009). Finally, we found damage to the corpus callosum. This is in line with the literature that indicates that damage to the corpus callosum prevents the identification of emotional states by interrupting the communication between the verbal processing initiated by the left hemisphere and the vocal and facial processing carried by the right hemisphere (McDonald, Rushby, Dalton, Allen, & Parks, 2018; Symington, Paul, Symington, Ono, & Brown, 2010).

4.2. Anosognosia for Theory of Mind deficits

In the present study, we have taken self-awareness to indicate the individual capacity to judge and rate one's own proficiency in accordance with an objective assessment of performance (or with ratings from a close informant or a clinician), and to adjust this judgement in accordance with any mistakes and failures. Three different methods were used to demonstrate that AP failed in both of the tests which were administered to assess anosognosia, that is, the metacognitive tasks (i.e. a direct interview with questions regarding his symptoms and a comparison between the judgements made by the patient himself versus those of his partner and his neuropsychologist) and the on-line task (i.e. the patient's pre- and post-task judgements). In terms of the aims of the present study, it was particularly interesting to note that the evaluations made by the patient regarding his abilities in cognitive tasks were no different to those of the informants (and he even overestimated his difficulties in ADL which were in fact minimal) with the exception of the items regarding emotions and social interactions. This excludes the contribution of a general metacognitive impairment, as he was aware of his errors in cognitive tasks, and anosognosia was specific for his social and emotional deficits. Moreover, his AToM was not associated with attentional deficits (Dockree, O'Connel, & Robertson, 2015), executive deficits (Bivona et al., 2008) or deficits in Memory or Comprehension (O'Keefe, Dockree, Moloney, Carton, & Robertson, 2007). Although we do not have direct measures of AP's pre-trauma personality, he was described as a sociable person who was highly esteemed in his job which was very demanding in terms of social competences. Thus, we consider that he did not have any difficulties in understanding others' thoughts and feelings before the trauma.

In our review of the literature on the topic, we found only a few experimental studies that specifically focus on awareness of behavioural disorders in neurological patients and to the best of our knowledge there is only one other study that addresses awareness for ToM deficits.

In that study, Bach & David (2006) compared patients with and without behavioural disorders in a modified version of the PCRS which included some specific questions regarding ToM (e.g. “How much of a problem do I have in understanding jokes?”; How much of a problem do I have to be tactful?”). They found that 80% of the behaviourally disturbed participants overestimated their social functioning, versus 45% of the participants without behavioural problems. These results suggest that although often associated, behavioural disorders and awareness of social functioning may at times be dissociated and behavioural disorders can occur despite intact ToM ability (Bach & David, 2006). Furthermore, in the same study, social self-awareness and performance in tasks assessing ToM were found to be only modestly associated (i.e. with ToM stories: r= -.421 p<.01; theory of mind cartoons: r= -.329, p<.05).

AP represents a particular case, as he does not have general behavioural problems (e.g. he can respect rules, he does not show disinhibition or aggression and he recognises the presence of a faux pas or an unpleasant social situation), but does show evidence of very specific deficits in terms of understanding others' thoughts and emotions. This gave us the opportunity to observe these disorders from a different perspective, namely, by assuming that ToM is not only a predictor of the overestimation of social self-awareness (Bach & David, 2006), but is also a function about which the patient may be specifically unaware. One may consider that ToM involves the capacity to take the perspective of other people to understand their point of view and some research suggests that this is also necessary in order to be aware of the reasons for one's own behaviour (Besharati, Kopelman, Avesani, Moro, Fotopoulou, 2015; Besharati, Forkel, Kopelman, Solms, Jenkinson, Fotopoulou, 2015). If this is so, then capacities associated with ToM would be always associated with anosognosia. However, clinical experience indicates that there are patients who recognise their difficulties in social behaviour (20% in Bach and David, 2006) or at least admit their mistakes. AP does not show any indications that he is able to modulate his awareness in terms of ToM but does change his judgments about his cognitive capacities after failure. The hypothesis of a form of anosodiaphoria relating to “apathy or lack of concern in relation to a condition (Jenkinson et al., 2018)” cannot be excluded. However, it is worth noting that this lack of awareness was very specific in our patient and only referred to his disorders in ToM. The patient was indeed very worried about the slightest motor symptoms (e.g. fatigue and poor stamina when exerting himself physically) and regarding the temporarily limitations to daily life activities (e.g. driving, customer relations). There is a heated debate on whether awareness is a specific function or may have some domain-specific components (Vallar e Ronchi, 2009, Mograbi & Morris, 2013; Fotopoulou, 2014). Selective lack of awareness has been demonstrated in syndromes such as anosognosia for hemiplegia (Babinski, 1914), apraxia (Canzano, Scandola, Pernigo, Aglioti, & Moro, 2014; Scandola, Canzano, Avesani, Leder, Bertagnoli, Gobbetto, Aglioti, Moro, 2020), amnesia (Mograbi & Morris, 2013) and aphasia (Cocchini, Gregg, Beschin, Dean, & Della Sala, 2010), thus supporting a hypothesis of at least a partial specificity. However, neuro-anatomical data indicate that there may be a number of general processes relating to awareness, which would be associated with the neural networks involved in self-referred processes, the updating of self-referred beliefs and general behaviour monitoring and error processing (Pacella et al., 2019). The results of the analysis of brain lesion and white matter disconnection in AP suggests the hypothesis of a double contribution of both specific and general processes for AToM since the damage to the patient's brain involves: 1) the monitoring system (Aron, Behrens, Smith, Frank, & Poldrack, 2007; Bonnelle et al., 2012 Ham et al., 2014) and part of the attentional system in the right hemisphere (Parlatini et al., 2017; Bressler, Tang, Sylvester, Shulman, & Corbetta, 2008; Corbetta, Kincade, Ollinger, McAvoy, & Shulman, 2000); 2) the limbic system (Berlin, Rolls, & Kischka, 2004b; Grabenhorst & Rolls, 2011; Kringelbach & Rolls, 2004) and default mode network (Raichle et al., 2001) in the left hemisphere; and 3) the mentalising system and other grey and white matter structures which have been discussed above as these are specifically related to ToM deficits.

The main limitation of the present study is linked to the fact that it is a single case study. Data on groups of patients with more appropriate statistical controls would provide an opportunity to compare patients with behavioural problems and patients suffering from specific ToM deficits and this would be extremely useful in terms of confirming the results and hypothesis relating to our research. Nevertheless, it is important to take into consideration the fact that patients with such specific deficits who do not also have cognitive and behavioural disorders are extremely rare and this case thus represents a unique opportunity for an integrated neuropsychological and neuroanatomical investigation. Another limit is the absence of a control group for the tasks used to assess awareness. The ToM tasks are in effect very easy to execute for healthy people and awareness is not measurable in subjects who are without deficits. In a different way, the use of brain damaged people as controls is problematic due to the fact that it is difficult to control for the presence of other deficits in cognitive functions. Technical problems prevented us from collecting neuroanatomical data from healthy controls. However, the patient's lesions were compared (following a previously used procedure) to an anatomical atlas (AAL, http://www.cyceron.fr/web/aal anatomical automatic labeling.html) and the patient's tractography reconstruction of one hemisphere was compared with the reconstruction of its homologue (Thiebaut et al., 2014). Although inconclusive, these data may represent a first step towards a better comprehension of the neural correlates of ToM and self- awareness.

5. Conclusion

The study reports a case of deficits in ToM capacitiesdeficits. By means of an ad-hoc battery of neuropsychological tests and a neuroanatomical study, the patient's awareness of his deficits was investigated. In addition, a meta-analysis of literature on the topic enabled us to distinguish between ToM deficits and potential concomitant symptoms, in particular relating to executive functions. The results indicate there is potentially a specific form of anosognosia for ToM deficits that would, however, need to be further investigated.

Supplementary Material

Credit Author Statement.

authors' individual contributions

Valentina Pacella: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Roles/Writing - original draft

Michele Scandola: Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology

Maddalena Beccherle, Giulia Agostini: Meta-analisys of literature

Cristina Bulgarelli, Renato Avesani, Giovanni Carbognin: Investigation

Michel de Thieabut Schotten: Supervision; Funding acquisition

Valentina Moro: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Project administration; Resources;

Supervision; Writing -review and editing

Acknowledgments

We thank A.P. for his kindness and his willing participation in our study. Funding: This study was supported by MIUR Italy (PRIN 20159CZFJK and PRIN 2017N7WCLP to V.M.); by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 818521 to MTS) and by Fondati on pour la Recherche Me dicale (FRM DEQ20150331725 to the frontlab team).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

Declaration of interest: none.

Contributor Information

Valentina Pacella, Email: valentina.pacella.90@gmail.com.

Michele Scandola, Email: michele.scandola@univr.it.

Maddalena Beccherle, Email: maddalena.beccherle@gmail.com.

Cristina Bulgarelli, Email: cristinabulgarelli06@gmail.com.

Renato Avesani, Email: renato.avesani@sacrocuore.it.

Giovanni Carbognin, Email: giovanni.carbognin@sacrocuore.it.

Giulia Agostini, Email: agostinigiulia93@gmail.com.

Michel Thiebaut de Schotten, Email: michel.thiebaut@gmail.com.

References

- Abu-Akel A, Shamay-Tsoory S. Neuroanatomical and neurochemical bases of theory of mind. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(11):2971–2984. doi: 10.1016/j~.neuropsychologia.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allamanno N, Della Sala S, Laiacona M, Pasetti C, Spinnler H. Problem solving ability in aging and dementia: Normative data on a non-verbal test. The Italian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 1987;8(2):111–119. doi: 10.1007/BF02337583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci G, Spitoni G, Cantagallo A. La valutazione con BADS. In: Cantagallo A, Spitoni G, Antonucci G, editors. LE FUNZIONI ESECUTIVE-Valutazione e riabilitazione. Carocci; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Apperly IA, Samson D, Chiavarino C, Humphreys GW. Frontal and Temporo-Parietal Lobe Contributions to Theory of Mind: Neuropsychological Evidence from a False-Belief Task with Reduced Language and Executive Demands. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16(10):1773–1784. doi: 10.1162/0898929042947928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Behrens TE, Smith S, Frank MJ, Poldrack RA. Triangulating a Cognitive Control Network Using Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Functional MRI. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(14):3743–3752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0519-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach LJ, David AS. Self-awareness after acquired and traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2006;16(4):397–414. doi: 10.1080/09602010500412830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Hill J, Raste Y, Plumb I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2001;42(2):241–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Leslie AM, Frith U. Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition. 1985;21(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Ring H, Moriarty J, Schmitz B, Costa D, Ell P. Recognition of Mental State Terms. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;165(5):640–649. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.5.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadle JN, Paradiso S, Tranel D. Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Is Critical for Helping Others Who Are Suffering. Frontiers in Neurology. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin HA, Rolls ET, Kischka U. Impulsivity, time perception, emotion and reinforcement sensitivity in patients with orbitofrontal cortex lesions. Brain. 2004a;127(5) doi: 10.1093/brain/awh135. 11081126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin HA, Rolls ET, Kischka U. Impulsivity, time perception, emotion and reinforcement sensitivity in patients with orbitofrontal cortex lesions. Brain. 2004b;127(5) doi: 10.1093/brain/awh135. 11081126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besharati S, Forkel SJ, Kopelman M, Solms M, Jenkinson PM, Fotopoulou A. Mentalizing the body: spatial and social cognition in anosognosia for hemiplegia. Brain. 2016;139(3):971–985. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besharati S, Kopelman M, Avesani R, Moro V, Fotopoulou A. Another perspective on anosognosia: self-observation in video replay improves motor awareness. Neuropsychological rehabilitation. 2015;25(3):319–352. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2014.923319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibby H, McDonald S. Theory of mind after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43(1):99–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivona U, Ciurli P, Barba C, Onder G, Azicnuda E, Silvestro D, et al. Formisano R. Executive function and metacognitive self-awareness after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2008;14(5):862–868. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708081125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnelle V, Ham TE, Leech R, Kinnunen KM, Mehta MA, Greenwood RJ, Sharp DJ. Salience network integrity predicts default mode network function after traumatic brain injury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(12):4690–4695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113455109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressler SL, Tang W, Sylvester CM, Shulman GL, Corbetta M. Top-Down Control of Human Visual Cortex by Frontal and Parietal Cortex in Anticipatory Visual Spatial Attention. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(40):10056–10061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1776-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW, Alderman N, Evans J, Emslie H, Wilson BA. The ecological validity of tests of executive function. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS. 1998;4(6):547–558. doi: 10.1017/s1355617798466037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffarra P, Vezzadini G, Zonato F, Copelli S, Venneri A. A normative study of a shorter version of Raven's progressive matrices 1938. Neurological Sciences. 2003;24(5):336–339. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantagallo A, Zoccolotti P. Il test dell'attenzione nella vita quotidiana (TAQ): contributo alla standardizzazione italiana. Rivista di Neurologia. 1998;12:111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Canzano L, Scandola M, Pernigo S, Aglioti SM, Moro V. Anosognosia for apraxia: Experimental evidence for defective awareness of one's own bucco-facial gestures. Cortex. 2014;61:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlesimo GA, Caltagirone C, Gainotti G, Fadda L, Gallassi R, Lorusso S, et al. Parnetti L. The Mental Deterioration Battery: Normative Data, Diagnostic Reliability and Qualitative Analyses of Cognitive Impairment. European Neurology. 1996;36(6):378–384. doi: 10.1159/000117297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlesimo GA, Caltagirone C, Gainotti G, Nocentini U. Batteria per la valutazione del deterioramento mentale (Parte II): Standardizzazione e affidabilita diagnostica nell'identificazione di pazienti affetti da sindrome demenziale. Archivio di Psicologia, Neurologia e Psichiatria. 1995;56:471–488. [Google Scholar]

- Cattelani R, Dal Sasso F, Corsini D, Posteraro L. The Modified Five-Point Test: normative data for a sample of Italian healthy adults aged 16-60. Neurological Sciences. 2011;32(4):595–601. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0489-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channon S, Pellijeff A, Rule A. Social cognition after head injury: Sarcasm and theory of mind. Brain and Language. 2005;93(2):123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicerone K. Disturbance of social cognition after traumatic orbitofrontal brain injury. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 1997;12(2):173–188. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6177(96)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocchini G, Gregg N, Beschin N, Dean M, Della Sala S. VATA-L: visual-analogue test assessing anosognosia for language impairment. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2010;24(8) doi: 10.1080/13854046.2010.524167. 13791399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocchini G, Logie RH, Della Sala S, MacPherson SE, Baddeley AD. Concurrent performance of two memory tasks: Evidence for domain-specific working memory systems. Memory & Cognition. 2002;30(7):1086–1095. doi: 10.3758/BF03194326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Hillside. NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. 1988 doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo L, Sartori G, Brivio C. Stima del quoziente intellettivo tramite l'applicazione del TIB (test breve di Intelligenza) Giornale Italiano di Psicologia. 2002;3:613–637. [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Kincade JM, Ollinger JM, McAvoy MP, Shulman GL. Voluntary orienting is dissociated from target detection in human posterior parietal cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3(3):292–297. doi: 10.1038/73009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosson B, Barco PP, Velozo CA, Bolesta MM, Cooper PV, Werts D, Brobeck TC. Awareness and compensation in postacute head injury rehabilitation. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 1989;4(3):46–54. doi: 10.1097/00001199-198909000-00008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Monte O, Schintu S, Pardini M, Berti A, Wassermann EM, Grafman J, Krueger F. The left inferior frontal gyrus is crucial for reading the mind in the eyes: Brain lesion evidence. Cortex. 2014;58:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Barba G, Brazzarola M, Barbera C, Marangoni S, Causin F, Bartolomeo P, Thiebaut de Schotten M. Different patterns of confabulation in left visuo-spatial neglect. Experimental Brain Research. 2018;236(7):2037–2046. doi: 10.1007/s00221-018-5281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan B, Karnath H-O. A hitchhiker's guide to lesion-behaviour mapping. Neuropsychologia. 2018;115:5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Sala S, MacPherson SE, Phillips LH, et al. How many camels are there in Italy? Cognitive estimates standardised on the Italian population. NeurolSci. 2003;24:10–15. doi: 10.1007/s100720300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody N, Wong S, Ahmed R, Piguet O, Hodges JR, Irish M. Uncovering the Neural Bases of Cognitive and Affective Empathy Deficits in Alzheimer's Disease and the Behavioral-Variant of Frontotemporal Dementia. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2016;53(3) doi: 10.3233/JAD-160175. 801816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockree PM, O'Connell RG, Robertson IH. Connecting clinical and experimental investigations of awareness in traumatic brain injury. 2015:511–524. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63521-1.00032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dourado MCN, Laks J, Mograbi DC. Awareness in Dementia. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2019;1 doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Trexler LE, Gauggel S. Awareness of activity limitations and prediction of performance in patients with brain injuries and orthopedic disorders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2004;10(2):190–199. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotopoulou A. Time to get rid of the 'Modular' in neuropsychology: A unified theory of anosognosia as aberrant predictive coding. Journal of Neuropsychology. 2014;8(1):1–19. doi: 10.1111/jnp.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotopoulou A. The virtual bodily self: Mentalisation of the body as revealed in anosognosia for hemiplegia. Consciousness and Cognition. 2015;33:500–510. doi: 10.1016/jxoncog.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulon C, Cerliani L, Kinkingnehun S, Levy R, Rosso C, Urbanski M, et al. Thiebaut de Schotten M. Advanced lesion symptom mapping analyses and implementation as BCBtoolkit. GigaScience. 2018;7(3):1–17. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD, Frith U. The Neural Basis of Mentalizing. Neuron. 2006;50(4):531–534. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD, Frith U. Implicit and Explicit Processes in Social Cognition. Neuron. 2008;60(3):503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher HL, Frith CD. Functional imaging of “theory of mind”. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2003;7(2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(02)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher HL, Jack AI, Roepstorff A, Frith CD. Imaging the intentional stance in a competitive game. NeuroImage. 2002;16(3 Pt 1):814–821. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambina G, Valbusa V, Corsi N, Ferrari F, Sala F, Broggio E, et al. Moro V. The Italian Validation of the Anosognosia Questionnaire for Dementia in Alzheimer's Disease. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementiasr. 2015;30(6):635–644. doi: 10.1177/1533317515577185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasquoine PG. Blissfully unaware: Anosognosia and anosodiaphoria after acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2016;26(2):261–285. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2015.1011665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genova HM, Rajagopalan V, Chiaravalloti N, Binder A, Deluca J, Lengenfelder J. Facial affect recognition linked to damage in specific white matter tracts in traumatic brain injury. Social Neuroscience. 2015;10(1):27–34. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2014.959618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraci A, Surian L, Ferraro M, Cantagallo A. Theory of Mind in patients with ventromedial or dorsolateral prefrontal lesions following traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 2010;24(7-8):978–987. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2010.487477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabenhorst F, Rolls ET. Value, pleasure and choice in the ventral prefrontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011;15(2):56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory C, Lough S, Stone V, Erzinclioglu S, Martin L, Baron-Cohen S, Hodges JR. Theory of mind in patients with frontal variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease: theoretical and practical implications. Brain. 2002;125(4):752–764. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham TE, Bonnelle V, Hellyer P, Jilka S, Robertson IH, Leech R, Sharp DJ. The neural basis of impaired self-awareness after traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2014;137(2):586–597. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havet-Thomassin V, Allain P, Etcharry-Bouyx F, Le Gall D. What about theory of mind after severe brain injury? Brain Injury. 2006;20(1):83–91. doi: 10.1080/02699050500340655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Phillips LH, Crawford JR, Theodorou G, Summers F. Cognitive and psychosocial correlates of alexithymia following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44(1):62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho AK, Robbins AOG, Barker RA. Huntington's disease patients have selective problems with insight. Movement Disorders. 2006;21(3):385–389. doi: 10.1002/mds.20739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoofien D, Gilboa A, Vakil E, Barak O. Unawareness of Cognitive Deficits and Daily Functioning Among Persons With Traumatic Brain Injuries. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2004;26(2):278–290. doi: 10.1076/jcen.26.2.278.28084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, Leekam S. What are the Links Between Theory of Mind and Social Relations? Review, Reflections and New Directions for Studies of Typical and Atypical Development. Social Development. 2004;13(4):590–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.00285.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Im WY, Ha JH, Kim EJ, Cheon K-A, Cho J, Song D-H. Impaired White Matter Integrity and Social Cognition in High-Function Autism: Diffusion Tensor Imaging Study. Psychiatry Investigation. 2018;15(3):292–299. doi: 10.30773/pi.2017.08.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson PM, Moro V, Fotopoulou A. Definition: Asomatognosia. Cortex. 2018;101:300–301. doi: 10.1016/J.CORTEX.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach M, Rolls ET. The functional neuroanatomy of the human orbitofrontal cortex: evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychology. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004;72(5):341–372. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer KG, Levine DN. Babinski, J. (1914). Contribution to the study of the mental disorders in hemiplegia of organic cerebral origin (anosognosia). Translated by K.G. Langer & D.N. levine. Translated from the original Contribution a l'Etude des troubles mentaux dans l'hemiple. Cortex. 2014;61:5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leemans A, Jeurissen B, Sijbers J, Jones DK. ExploreDTI: a graphical toolbox for processing, analyzing, and visualizing diffusion MR data. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.exploredti.com.

- Lockwood PL. The anatomy of empathy: Vicarious experience and disorders of social cognition. Behavioural Brain Research. 2016;311:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzatti C, Willmes K, De Bleser R. Versione italiana. Florence: Organizzazioni Speciali; 1996. Aachener Aphasie Test (AAT) [Google Scholar]