Abstract

Handedness has been extensively studied because of its relationship with language and the over-representation of left-handers in some neurodevelopmental disorders. Using data from the UK Biobank, 23andMe and the International Handedness Consortium, we conducted a genome-wide association meta-analysis of handedness (N = 1,766,671). We found 41 loci associated (P < 5 × 10–8) with left-handedness and 7 associated with ambidexterity. Tissue-enrichment analysis implicated the CNS in the aetiology of handedness. Pathways including regulation of microtubules and brain morphology were also highlighted. We found suggestive positive genetic correlations between left-handedness and neuropsychiatric traits, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Furthermore, the genetic correlation between left-handedness and ambidexterity is low (r G = 0.26), which implies that these traits are largely influenced by different genetic mechanisms. Our findings suggest that handedness is highly polygenic and that the genetic variants that predispose to left-handedness may underlie part of the association with some psychiatric disorders.

Handedness refers to the preferential use of one hand over the other. Conversely, ambidexterity refers to the ability to perform the same action equally well with both hands. Hand preference is first observed during gestation as embryos begin to exhibit single arm movements1,2. Across the life span, the consistent use of one hand leads to alterations in the macromorphology and micromorphology of bone3, which results in enduring asymmetries in bone form and density4,5. At the neurological level, handedness is associated with the lateralization of language (the side of the brain involved in language) and other cognitive effects6,7. The prevalence of left-handedness in modern western cultures is approximately 9%8 and is greater in males than females9. While handedness is conceptually simple, its aetiology and whether it is related to brain and visceral (internal organ) asymmetry is unclear.

Since the mid-1980s, the literature regarding the genetics of handedness and lateralization has been dominated by the right-shift10 and dextral-chance11 theories. Both theories involve additive biallelic monogenic systems in which an allele at the locus biases an individual towards right-handedness, while the second allele is a null allele that results in the random determination of handedness by fluctuating asymmetry. The allele frequency of the right-shift variant has been estimated at ~43.5%10, while that of the dextral-chance variant has been estimated at ~20% in populations with a 10% prevalence of left-handedness11. A joint analysis of data from 35 twin studies found that additive genetic factors accounted for 25.5% (95% confidence interval (CI) of 15.7, 29.5%) of the phenotypic variance of handedness12, which is consistent with predictions of the variance explained under the single gene right-shift and dextral-change models. However, linkage studies13–16, candidate gene and genome-wide association studies (GWAS)17–21 have failed to identify any putative major gene for handedness.

Most recently, two large-scale GWAS identified four genomic loci containing common variants of small effect associated with handedness20,21. However, both GWAS failed to replicate signals at the LRRTM1, PCSK6 and the X-linked androgen receptor genes that had previously been reported in smaller genetic association studies17–19. In this study, we present findings from the world’s largest GWAS meta-analysis of handedness to date (N = 1,766,671), which combined data from 32 cohorts from the International Handedness Consortium (IHC) (N = 125,612), 23andMe (N = 1,178,877) and the UK Biobank (UKBB) (N = 462,182).

Results

GWAS of left-handedness

Across all studies, the handedness phenotype was assessed by a questionnaire that evaluated either which hand was used for writing or for self-declared handedness. All cohorts were randomly ascertained with respect to handedness. Combining data across the 32 IHC cohorts, 23andMe and UKBB yielded 1,534,836 right-handed and 194,198 left-handed (11.0%) individuals (Supplementary Table 1). After quality control (Methods), the GWAS meta-analysis included 13,346,399 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; including autosomal and X chromosome SNPs) with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of >0.5%.

The genetic correlations as estimated by bivariate linkage disequilibrium (LD) score regression22 among the results from the UKBB, 23andMe and IHC GWAS were r G UKBB–23andMe = 0.88 (s.e. = 0.05), r G UKBB–IHC = 0.73 (s.e. = 0.16) and r G IHC–23andMe = 0.60 (s.e. = 0.11), which suggests that the three GWAS were capturing many of the same genetic loci for handedness. There was some inflation of the test statistics following meta-analysis (λ GC = 1.22); however, the intercept from the LD score regression analysis23 was 1.01. This suggests that the inflation was due to polygenicity rather than bias due to population stratification or duplication of participants across the UKBB, 23andMe and IHC studies.

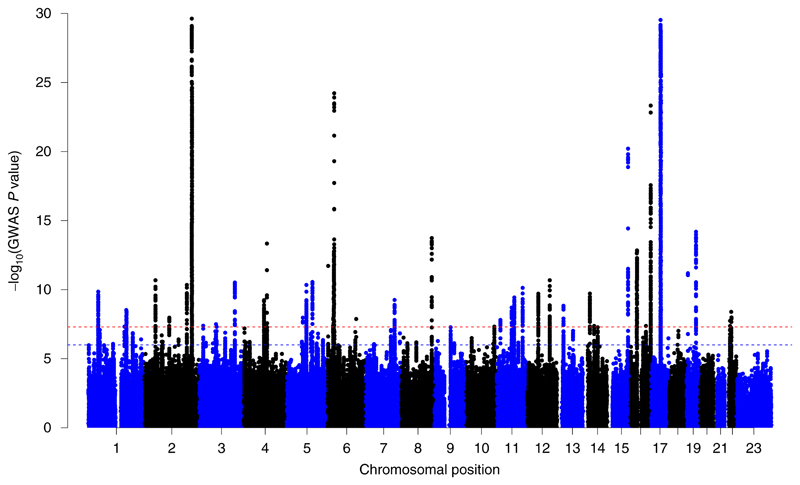

We identified 41 loci that met the threshold for genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10–8) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). Loci were defined as distinct if independent genome-wide significant signals were separated by at least 1 Mb, except for the MHC and 17q21.31 regions (the 17q21.31 region contains a common inversion polymorphism24) for which we only report the lead signals due to the extent of LD across these loci. Summary statistics for the lead variants at genome-wide significant loci are presented in Table 1 along with the gene nearest to the lead SNP. A description of the putative functions of the nearest gene is included in Supplementary Table 2. Conditional analyses identified nine additional independent SNPs at genome-wide significance near the lead SNPs on chromosomes 2q, 6p, 16q and 17q (Supplementary Table 3). Interestingly, the list of genome-wide significant associations included multiple variants close to genes involved in microtubule formation or regulation (that is, MAP2, TUBB, TUBB3, NDRG1, TUBB4A, TUBA1B, BUB3 and TTC28). A phenome-wide association scan (PheWAS) of the lead SNPs using GWAS summary data from 1,349 traits revealed that 28 out of the 41 lead SNPs have previously been associated with other complex traits (Supplementary Table 4). Among these results, we highlight that the rs6224, rs13107325 and rs45527431 variants have previously been associated with schizophrenia at genome-wide levels of significance (P < 5 × 10–8). Alleles at these loci had the same direction of effect (that is, those that increased the odds of left-handedness also increased the risk of schizophrenia). Furthermore, we found that seven variants associated with left-handedness were also associated with educational attainment; however, the direction of effect of these SNPs on left-handedness and educational attainment was not consistent. Future colocalization analyses are needed to assess whether the same SNPs associated with handedness also affect these other traits or whether the pattern of signals are more likely due to LD with another causal variant.

Fig. 1. Manhattan plot of the left-handedness meta-analysis.

Manhattan plots for the left-handedness GWAS meta-analysis (N = 1,534,836 right-handed versus 194,198 left-handed). Each dot represents a SNP. The red broken line highlights the genome-wide levels of significance threshold (P < 5 × 10–8); the blue broken line shows the threshold for suggestive associations.

Table 1.

Loci associated with left-handedness after a meta-analysis of 23andMe, UKBB and IHC data

| CHR | BP | SNP | Gene | EA | NEA | EAF | Z | ORa | P | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44172458 | rs34550543 | ST3GAL3 | T | C | 0.41 | 6.42 | 1.02 | 1.4 × 10–10 | +++ |

| 1 | 160398240 | rs66513715 | VANGL2 | D | I | 0.20 | –5.46 | 0.97 | 4.77 × 10–8 | -?? |

| 1 | 169112399 | rs10081960 | NME7 | C | G | 0.60 | –5.93 | 0.98 | 2.96 × 10–9 | - - - |

| 2 | 48624007 | rs4953572 | FOXN2 | A | G | 0.66 | 6.70 | 1.02 | 2.11 × 10–11 | +++ |

| 2 | 109954066 | rs4676276 | SH3RF3 | A | C | 0.52 | 5.72 | 1.02 | 1.06 × 10–8 | +++ |

| 2 | 187522750 | rs13006483 | ITGAV | T | G | 0.28 | 6.59 | 1.03 | 4.51 × 10–11 | +++ |

| 2 | 210300731 | rs62213410 | MAP2 | A | T | 0.71 | –11.45 | 0.96 | 2.37 × 10–30 | - - - |

| 3 | 18167162 | rs1398651 | SATB1 | A | T | 0.56 | 5.49 | 1.02 | 4.11 × 10–8 | +++ |

| 3 | 74246260 | rs201072423 | CNTN3 | D | I | 0.51 | 5.53 | 1.02 | 3.17 × 10–8 | +++ |

| 3 | 77574555 | rs62251113 | ROBO2 | A | C | 0.37 | 5.45 | 1.02 | 4.94 × 10–8 | +++ |

| 3 | 158017859 | rs1526194 | RSRC1 | T | C | 0.58 | –6.65 | 0.98 | 3.02 × 10–11 | - - - |

| 4 | 89910701 | rs28658282:T | FAM13A | T | C | 0.10 | –6.20 | 0.96 | 5.77 × 10–10 | -?? |

| 4 | 103188709 | rs13107325 | SLC39A8 | T | C | 0.08 | 7.54 | 1.06 | 4.62 × 10–14 | +++ |

| 5 | 71890187 | rs246628 | LINC02056 | C | G | 0.41 | 5.72 | 1.02 | 1.06 × 10–8 | +++ |

| 5 | 87825490 | rs2194028 | TMEM161B-AS1 | T | C | 0.34 | 6.59 | 1.02 | 4.52 × 10–11 | +++ |

| 5 | 114471109 | rs1422070 | TRIM36 | A | C | 0.60 | –6.65 | 0.98 | 2.85 × 10–11 | - - - |

| 6 | 3143866 | rs35551703 | BPHL | A | G | 0.04 | –7.04 | 0.94 | 1.93 × 10–12 | - - - |

| 6 | 26599509 | rs45527431 | ABT1 | A | G | 0.91 | 5.86 | 1.04 | 4.63 × 10–9 | ++? |

| 6 | 30688427 | rs3132584 | TUBB | T | G | 0.21 | –10.31 | 0.95 | 6.12 × 10–25 | - - - |

| 6 | 127643791 | rs148342778:GTA | ECHDC1 | D | I | 0.65 | –5.68 | 0.97 | 1.32 × 10–8 | -?? |

| 7 | 127268806 | rs806188 | PAX4 | T | C | 0.32 | 6.20 | 1.02 | 5.65 × 10–10 | +++ |

| 8 | 134274226 | rs2233324 | NDRG1 | C | G | 0.16 | –7.66 | 0.96 | 1.86 × 10–14 | - - - |

| 10 | 124992505 | rs12414988 | BUB3 | A | G | 0.21 | 5.46 | 1.02 | 4.75 × 10–8 | +++ |

| 11 | 16474017 | rs1000565 | SOX6 | A | G | 0.60 | 5.65 | 1.02 | 1.56 × 10–8 | +++ |

| 11 | 66173400 | rs11227478 | NPAS4 | A | G | 0.21 | –6.00 | 0.98 | 1.97 × 10–9 | - - - |

| 11 | 77531890 | rs11820337 | RSF1 | T | C | 0.35 | 6.27 | 1.02 | 3.64 × 10–10 | +++ |

| 11 | 115081563 | rs9645660 | CADM1 | T | C | 0.52 | –6.51 | 0.98 | 7.43 × 10–11 | - - - |

| 12 | 49539892 | rs11168884 | TUBA1B | T | C | 0.34 | –6.37 | 0.98 | 1.96 × 10–10 | - - - |

| 12 | 100324975 | rs7132513:G | ANKS1B | C | G | 0.61 | 6.70 | 1.03 | 2.1 × 10–11 | +?? |

| 13 | 27294638 | rs9581731 | WASF3 | T | C | 0.71 | –6.05 | 0.98 | 1.49 × 10–9 | - - - |

| 14 | 29628115 | rs8016028 | AL133166.1 | T | C | 0.81 | –6.37 | 0.97 | 1.92 × 10–10 | - - - |

| 14 | 48430794 | rs8012503 | LINC00648 | C | G | 0.88 | 5.48 | 1.03 | 4.27 × 10–8 | +++ |

| 15 | 91423543 | rs6224 | FURIN | T | G | 0.47 | –9.39 | 0.97 | 6.16 × 10–21 | - - - |

| 16 | 28828834 | rs62036618 | ATXN2L | A | C | 0.61 | –7.39 | 0.98 | 1.43 × 10–13 | - -? |

| 16 | 69224615 | rs1424114 | SNTB2 | T | C | 0.35 | –5.48 | 0.98 | 4.21 × 10–8 | - - - |

| 16 | 89991599 | rs4550447 | TUBB3 | C | G | 0.12 | 10.12 | 1.06 | 4.67 × 10–24 | +++ |

| 17 | 43757450 | rs55974014 | CRHR1 | A | C | 0.21 | –11.43 | 0.95 | 2.97 × 10–30 | - - - |

| 19 | 6499231 | rs66479618 | TUBB4A | T | C | 0.20 | –6.87 | 0.97 | 6.48 × 10–12 | – –+ |

| 19 | 42439263 | rs112737242 | RABAC1 | D | I | 0.35 | –7.80 | 0.97 | 6.4 × 10–15 | - -? |

| 22 | 23663848 | rs4822384 | BCR | T | G | 0.39 | –5.63 | 0.98 | 1.82 × 10–8 | - - - |

| 22 | 28628209 | rs5762532 | TTC28 | T | C | 0.59 | –5.88 | 0.98 | 4.04 × 10–9 | - - - |

BP, base pair positions based on the GRCh37–hg19 human genome assembly; CHR, chromosome; EA, effect allele; EAF, effect allele frequency; NEA, non-effect allele; P, meta-analysis P value; Z, Z-statistic. The direction of effects is shown in the following order: 23andMe, UKBB and IHC.

OR corresponds to that derived from the 23andMe results. Where the SNP is missing in a cohort, a question mark is indicated in the Direction column.

To identify the most likely tissues and pathways underling the GWAS signals, we used DEPICT25 and MAGMA26. Results from both the DEPICT and MAGMA tissue-enrichment analyses implicated (false discovery rate (FDR) < 5%) the central nervous system, including brain tissues such as the hippocampus and cerebrum (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 5), which is consistent with the hypothesis that handedness is primarily a neurological trait. We observed significant evidence for pathways involved in left-handedness (FDR < 5%), including regulation of microtubules and axons, as well as neurogenesis and morphology regulation of the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Table 3).

Table 2.

Results of the tissue-enrichment analysis for left-handedness (DEPICT)

| Tissue | Group | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Corpus striatum | Nervous system | 0.00000673 |

| Basal ganglia | Nervous system | 0.0000148 |

| Hippocampus | Nervous system | 0.0000227 |

| Central nervous system | Nervous system | 0.0000327 |

| Brain | Nervous system | 0.0000357 |

| telencephalon | Nervous system | 0.0000398 |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | Nervous system | 0.0000414 |

| entorhinal cortex | Nervous system | 0.0000414 |

| Limbic system | Nervous system | 0.0000423 |

| Cerebrum | Nervous system | 0.0000427 |

| Prosencephalon | Nervous system | 0.0000487 |

| temporal lobe | Nervous system | 0.0000587 |

| Cerebral cortex | Nervous system | 0.0000668 |

| Parietal lobe | Nervous system | 0.000305 |

| mesencephalon | Nervous system | 0.000843 |

| occipital lobe | Nervous system | 0.00131 |

| visual cortex | Nervous system | 0.00156 |

| Brain stem | Nervous system | 0.00166 |

Only results with FDR values <5% are shown.

Table 3.

Results from pathway-enrichment analysis for left-handedness (DEPICT and MAGMA)

| Pathway ID | Pathway description | P value |

|---|---|---|

| DEPICT | ||

| MP:0000788 | Abnormal cerebral cortex morphology | 0.00000185 |

| MP:0000807 | Abnormal hippocampus morphology | 0.00000187 |

| GO:0008017 | Microtubule binding | 0.00000195 |

| MP:0004275 | Abnormal postnatal subventricular zone morphology | 0.00000549 |

| ENSG00000137285 | TUBB2B subnetwork | 0.00000571 |

| MP:0000812 | Abnormal dentate gyrus morphology | 0.00000843 |

| ENSG00000206211 | ENSG00000206211 subnetwork | 0.0000128 |

| ENSG00000206283 | PFDN6 subnetwork | 0.0000128 |

| ENSG00000204220 | PFDN6 subnetwork | 0.0000128 |

| GO:0005874 | Microtubule | 0.0000140 |

| GO:0021543 | Pallium development | 0.0000456 |

| MP:0000790 | Abnormal stratification in the cerebral cortex | 0.0000500 |

| ENSG00000147601 | TERF1 subnetwork | 0.0000596 |

| GO:0015631 | Tubulin binding | 0.0000600 |

| REACTOME apoptotic execution phase | REACTOME apoptotic execution phase | 0.0000665 |

| GO:0021987 | Cerebral cortex development | 0.0000696 |

| ENSG00000182901 | RGS7 subnetwork | 0.0000731 |

| ENSG00000106105 | GARS subnetwork | 0.0000738 |

| GO:0007409 | Axonogenesis | 0.0000902 |

| REACTOME: apoptotic cleavage of cellular proteins | REACTOME: apoptotic cleavage of cellular proteins | 0.000108 |

| MAGMA | ||

| REACTOME: CRMPs in SEMA3A signalling | CRMPs in SEMA3A signalling | 4.13 × 10–8 |

| REACTOME: axon guidance | Axon guidance | 3.13 × 10–6 |

| GO: neurogenesis | Neurogenesis | 3.53 × 10–6 |

| REACTOME: semaphorin interactions | Semaphorin interactions | 9.84 × 10–6 |

| Matzuk: preovulatory follicle | Preovulatory follicle | 1.26 × 10–5 |

| REACTOME: SEMA3A–PAK-dependent axon repulsion | SEMA3A–PAK-dependent axon repulsion | 1.73 × 10–5 |

| GO: regulation of non-motile cilium assembly | Regulation of non-motile cilium assembly | 3.01 × 10–5 |

Only results with FDR <5% are shown.

We then performed gene-based analyses using gene-expression prediction models of brain tissues using S-MultiXcan to identify additional loci27. In total, we tested the association between the predicted expression of 14,501 genes in brain tissues and left-handedness. In addition to detecting significant associations (P < 3.44 × 10–6) of genes within the loci identified during the meta-analysis, we observed an association between left-handedness and the predicted expression of AMIGO1 (P = 2.82 × 10–7), a gene involved in the growth and fasciculation of neurites from cultured hippocampal neurons and may also be involved in the myelination of developing neural axons28. Supplementary Table 6 shows the significant associations from the S-MultiXcan analysis.

We also applied the summary-data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) approach using expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data from PsychENCODE29,30 and from a meta-analysis of eQTL data from brain tissues31 that included results from GTEx32, CMC33 and ROSEMAP34 to identify additional loci and to pinpoint genes behind the GWAS associations. Through this approach, we were unable to identify genes outside the loci from our main GWAS; however, we were able to implicate the NMT1, TUBA1C, FES, CENPBD1 and BCR genes as candidates underlying some of our genome-wide significant associations. Supplementary Table 7 shows all the statistically significant associations from the SMR analysis.

Multiple studies have reported that left-handedness and ambidexterity are more prevalent in males than in females9. Consistent with this observation, we found that 11.9% of male participants in the IHC cohorts reported being left-handed or ambidextrous compared with only 9.3% of females (odds ratio (OR) = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.25–1.38, P < 2.2 × 10–16) (Supplementary Table 8). Similarly, in the UKBB data, 10.5% of males and 9.9% of females were left-handed (OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 1.05–1.09, P = 1.87 × 10–11), and in 23andMe, 15.6% of males and 12.6% of females were left-handed (OR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.26–1.30, P < 2.2 × 10–16). Sex differences in ambidexterity were also apparent in the UKBB and 23andMe cohorts (these data were not available for the IHC cohorts). In the UKBB data, 2% of males and 1.30% of females reported being ambidextrous (OR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.47–1.62, P < 2.2 × 10–16), while in 23andMe, 3.45% of males and 2.61% of females were ambidextrous (OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.28–1.37, P < 2.2 × 10–16). Birth year had a small but significant effect on left-handedness, with individuals who were born more recently being more likely to be left-handed (OR = 1.008 per year, 95% CI = 1.007–1.009, P < 2.2 × 10–16).

The differences in prevalence between males and females and a previously reported association between the X-linked androgen receptor gene and handedness17 could reflect the involvement of hormone-related genes in handedness aetiology. We therefore carried out a sex-stratified GWAS of handedness in the UKBB data using left-handed individuals as cases and right-handed individuals as controls; however, we did not identify any genome-wide significant loci. Despite this, the point estimate of the genetic correlation between male handedness and female handedness computed using LD score regression was lower than unity but not significantly different from one (r G = 0.77 (s.e. = 0.12), P = 0.055).

Associations with previously reported candidate genes

All loci identified in recent GWAS of handedness from the UKBB20,21 were replicated in our study. However, we found no evidence of association between left-handedness and genes and genetic variants reported in other prior studies. The SNPs rs1446109, rs1007371 and rs723524 in the LRRTM1 locus reported by Francks et al.18 did not reach nominal significance in any of the analyses performed (P > 0.05). Similarly, the SNP rs11855415 reported by Scerri et al.19 as associated with left-handedness in individuals with dyslexia did not show evidence of association (P > 0.05). Furthermore, we investigated whether the 27 genes exhibiting asymmetric expression in early development of the cerebral cortex described by Sun et al.35 were associated with handedness in our S-MultiXcan analyses. Only 11 out of the 27 asymmetry genes were available in our analysis, and after adjusting the results for multiple testing, we did not observe any significant association (Supplementary Table 9). In a more recent study, Ocklenburg and colleagues36 list 74 genes displaying asymmetric expression in cervical and anterior thoracic spinal cord segments of five human fetuses. In total, 43 out of the 74 genes were in our S-MultiXcan analyses, of which only HIST1H4C was statistically significant after correcting for multiple testing (P = 2.2 × 10–4) (Supplementary Table 10).

Heritability of left-handedness and genetic correlations with other traits

Previous twin studies have estimated the heritability of left-handedness as around 25%12. In the present study, we employed LD score regression, genome-based restricted maximum likelihood (REML) analysis, as implemented in BOLT-LMM, and maximum likelihood analysis of identity by descent (IBD) sharing in close relatives37 to provide complementary estimates of SNP heritability and total heritability that relied on a different set of assumptions to the classical twin model. Using GWAS summary statistics from our study and LD score regression, we estimated that the variance explained by SNPs was 3.45% (s.e. = 0.17%) on the liability scale, assuming the prevalence of left-handedness is 10% (Table 4). Using genotypic data from the UKBB study (and age and sex as covariates) and genome-based REML analysis, we also obtained low estimates of the SNP heritability (5.87%, s.e. = 2.21%). Due to the large disparity between estimates of heritability from twin studies and the lower estimates of SNP heritability from the above approaches, we estimated the heritability of handedness using autosomal IBD information from closely related individuals37 in the UKBB data (estimated genome-wide IBD > 8%). We partitioned the phenotypic variance into additive genetic effects (A), shared environmental effects (C) and individual environmental effects (E) (Methods). We estimated that additive genetic effects explained 11.9% (95% CI = 7.2–17.7) of the phenotypic variance in handedness, while shared environmental effects and individual environment effects accounted for 4.6% (95% CI = 0–9.0) and 83.6% (95% CI = 75.2–85.6) of the variance in liability, respectively (Table 4). Dropping (C) from the model did not significantly worsen the fit of the model (P = 0.29). The estimate from the A+E model was 19.7% (95% CI = 13.6–25.7) for additive genetic effects, which overlapped with those from twin studies.

Table 4.

SNP heritability and heritability of left-handedness estimated using a range of different approaches

| Data used | Method | h g 2 (s.e.)—liability scale |

|---|---|---|

| IHC meta-analysis (32 studies) | LD score regression | 0.031 (0.013) |

| UKBB left-handed individuals only as cases | LD score regression | 0.033 (0.004) |

| 23andMe left-handed individuals only as cases | LD score regression | 0.040 (0.002) |

| Meta-analysis UKBB, 23andMe and IHC | LD score regression | 0.035 (0.002) |

| UKBB left-handed individuals only as cases (males) | LD score regression | 0.042 (0.006) |

| UKBB left-handed individuals only as cases (females) | LD score regression | 0.032 (0.005) |

| UKBB left-handed individuals only as cases | REML (BOLT-LMM) | 0.059 (0.003) |

| Right- versus left-handed 0.08 < IBD < 0.3 relatives (no C) + siblings 0.65 > IBD > 0.35 with C in the model | A+C+E model | A = 0.12a (95% CI = 0.07–0.17), C = 0.045 (95% CI = 0–0.09) |

| Right- versus left-handed 0.08 < IBD < 0.3 relatives (no C) + siblings 0.65 > IBD > 0.35 without C in the model | A+E model | A = 0.20 (95% CI = 0.14–0.26) |

| Meta-analysis of twin studies of handedness12 | A+C+E model | A = 0.25 (95% CI = 0.157–0.30), C = 0 (95% CI = 0–0.076%) |

Estimate of narrow-sense heritability (h 2).

We investigated the genetic correlation between left-handedness and 1,349 complex traits using LD score regression as implemented in the Complex-Traits Genetics Virtual Lab (CTG-VL)38. We did not observe any genetic correlations at FDR < 5% beside handedness itself. However, we observed a general inflation of P values across the traits (that is, the expected number of traits with genetic correlations at P < 0.05 under the null hypothesis of no association was 67.45, whereas we observed 102 traits with P < 0.05). We also observed suggestive positive correlations with neurological and psychiatric traits, including schizophrenia (P = 0.005663), bipolar disorder (P = 0.0023), intracranial volume (P = 0.01205) and educational attainment (P = 0.001772), and negative correlations with mean pallidum volume (P = 0.01124) (Supplementary Table 11).

GWAS of ambidexterity

We carried out a separate GWAS of ambidexterity with the UKBB and 23andMe data using ambidextrous individuals as cases (N = 37,637; ~2% of the total sample) and right-handed individuals as controls (N = 1,422,823). This meta-analysis included 12,493,443 autosomal and X chromosome SNPs with a MAF > 0.5%.

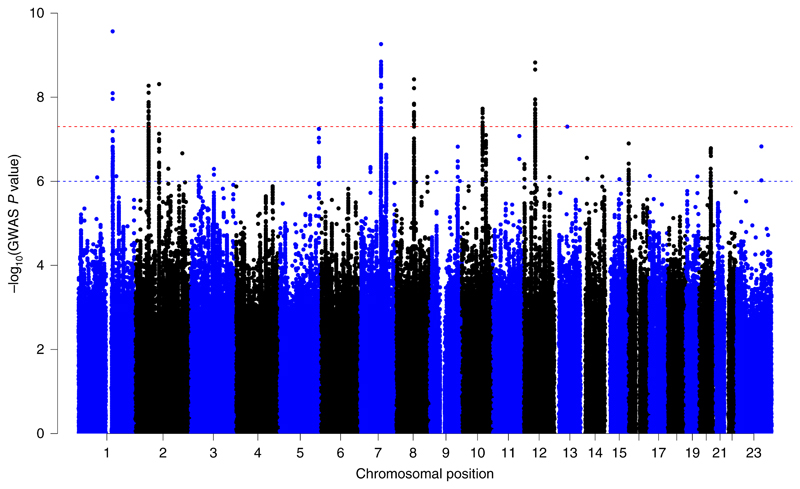

Similar to the left-handedness GWAS, before the meta-analysis, we computed the genetic correlation between the UKBB ambidexterity GWAS and the 23andMe GWAS. The estimate of the genetic correlation was r G = 1 (s.e. = 0.15), which indicates that both GWAS were capturing the same genetic loci. After the meta-analysis, we identified seven loci with P < 5 × 10–8 (Fig. 2). Table 5 displays the summary statistics for the lead SNPs at these loci along with the closest gene. Full summary statistics and descriptions of the nearest gene for these loci are included in Supplementary Table 12. There was some overlap between genome-wide significant SNPs associated with left-handedness and ambidexterity. A total of 16 out of the 41 SNPs associated with left-handedness displayed a nominal significant association with ambidexterity (P < 0.05), 15 of which were also in the same direction of effect (Supplementary Table 13). Conditional analyses did not identify further independent signals at genome-wide levels of significance. PheWAS revealed that the lead SNPs have been implicated in anthropometric traits and blood bio-markers (Supplementary Table 14).

Fig. 2. Manhattan plot of the ambidexterity meta-analysis.

Manhattan plots for the ambidexterity GWAS meta-analysis (N = 1,422,823 right-handed versus 37,637 ambidextrous individuals). Each dot represents a SNP. The red broken line highlights the genome-wide levels of significance threshold (P < 5 × 10–8); the blue broken line shows the threshold for suggestive associations.

Table 5.

Loci associated with ambidexterity after a meta-analysis of 23andMe and UKBB data

| CHR | BP | SNP | Gene | EA | NEA | EAF | Z | ORa | P | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 150317558 | rs782122127 | PRPF3 | D | I | 0.19 | –6.32 | 0.88 | 2.70 × 10–10 | ?– |

| 2 | 58196110 | rs2030237 | VRK2 | A | G | 0.58 | 5.84 | 1.04 | 5.29 × 10–9 | ++ |

| 2 | 104437850 | rs139630683 | AC0137271 | D | I | 0.45 | 5.85 | 1.05 | 4.88 × 10–9 | +? |

| 7 | 91899117 | rs2040498 | ANKIB1 | A | T | 0.65 | 6.21 | 1.06 | 5.42 × 10–10 | ++ |

| 8 | 77104817 | rs10113066 | RNU2–54P | T | G | 0.51 | 5.90 | 1.05 | 3.74 × 10–9 | ++ |

| 10 | 89722731 | rs36062478 | PTEN | T | C | 0.87 | –5.62 | 0.94 | 1.87 × 10–8 | – – |

| 12 | 49530132 | rs35554786 | TUBA1B | D | I | 0.24 | –6.05 | 0.93 | 1.49 × 10–9 | –? |

The direction of effects is shown in the following order: 23andMe and UKBB.

OR corresponds to that derived from the 23andMe results. Where the SNP is missing in a cohort, a question mark is indicated in the Direction column.

The DEPICT analysis did not identify any tissue or pathway at FDR < 5%. However, the MAGMA tissue-enrichment analysis highlighted all the brain tissues tested (FDR < 5%), including brain cerebellar hemisphere and the cerebellum (Supplementary Table 15). The MAGMA pathway analysis identified 16 pathways (FDR < 5%), including regulation of cell size, basal dendrite, postsynaptic cytosol, among others that are hard to interpret such as pulmonary valve morphogenesis and development (Supplementary Table 16).

A S-MultiXcan analysis based on the association between predicted gene expression in brain tissues and ambidexterity identified the genes QTRTD1, TMEM215, RPL41 and RAB40C in addition to those loci identified during the GWAS (Supplementary Table 17). The SMR analysis pinpointed TUBA1C and CYP51A1 as potentially behind the GWAS associations on chromosomes 12 and 7, respectively (Supplementary Table 18).

Heritability of ambidexterity and genetic correlations

The number of ambidextrous individuals in the UKBB was not enough to precisely estimate heritability using maximum likelihood analysis of IBD sharing in close relatives. However, the SNP heritability of ambidexterity on the liability scale (1% prevalence) estimated through LD score regression and REML implemented in BOLT-LMM was higher than that observed for left-handedness (h 2 g = 0.12 (s.e. = 0.007) and h 2 g = 0.15 (s.e. = 0.014)).

We estimated the genetic correlation between ambidexterity and a catalogue of 1,349 traits with GWAS summary statistics. Our analyses revealed 575 genetic correlations at FDR < 5%. Among the strongest correlations were positive genetic correlations between ambidexterity and traits related to pain and injuries, and body mass index, and a negative genetic correlation with educational attainment (Supplementary Table 19). Interestingly, the genetic correlation between our left-handedness meta-analysis and our ambidexterity meta-analysis was only moderate (r G = 0.24, s.e. = 0.03), which suggests that there are divergent genetic aetiologies.

Discussion

We carried out the largest genetic study of handedness to date. Our GWAS and SNP heritability analyses conclusively demonstrate that handedness is a polygenic trait, with multiple genetic variants that implicate multiple biological pathways each increasing the odds of being left-handed or ambidextrous by a small amount. We identified 41 left-handedness and 7 ambidexterity loci that reached genome-wide significance. Our findings are in contrast to the single-gene right-shift10 and dextral-chance11 hypotheses, whereby the causal genes are hypothesized to account for the heritability of handedness. If these large-effect variants do exist, they should have been detected by our GWAS meta-analysis, which provided over 90% statistical power (Supplementary Table 20) to detect variants with effect sizes as small as a 5% increase in odds per allele for common variants (MAF > 0.05) at genome-wide significance (α = 5 × 10–8). Instead, the present findings firmly support the hypothesis that handedness, like many other behavioural and neurological traits, is influenced by many variants of small effect and multiple biological pathways.

Using different methods and cohorts, we estimated the SNP heritability (h g 2) of handedness to be between 3% and 6%. However, by using IBD-based methods applied to siblings and other relative pairs, we estimated the narrow-sense heritability (h 2) to be 11.9% (95% CI = 7.2–17.7). Although this is lower than that obtained from twin studies (25%, 95% CI = 15.7–29.5 (ref. 12) and 21%, 95% CI = 11–30 (ref. 39)), the CIs for the estimates overlap. Interestingly, h g 2 estimates for ambidexterity were larger (12–15%), which suggests that common SNPs tag a higher proportion of variability in liability to ambidexterity than in liability to left-handedness.

Our GWAS meta-analysis of left-handedness identified eight loci close to genes involved in microtubule formation and regulation. An enrichment for microtubule-related pathways was then confirmed by the DEPICT analysis. Microtubules are polymers that form part of the cytoskeleton and are essential in several cellular processes, including intracellular transport, cytoplasmic organization and cell division. With respect to handedness, microtubule proteins play important roles during the development and migration of neurons, plasticity and neurodegenerative processes40,41. The association between handedness and variation in microtubule genes also provides insights into differences in the prevalence of various neuropsychiatric disorders and left-handedness observed in some epidemiological studies42,43. Recent genetic studies have identified mutations in a wide variety of tubulin isotypes and microtubule-related proteins in many major neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases40,44–46.

We observed an association between left-handedness and the 17q21.31 locus. A deletion in this locus is known to cause Koolen de Vries syndrome, a disorder characterized by intellectual disability, developmental delay and neurological abnormalities of the corpus callosum, hippocampi and ventricles. Variation in the 17q21 locus, including structural variation, has been associated with schizophrenia47, autism48,49 and cognition50. In addition, based on our PheWAS, the rs55974014 SNP within this locus has been associated with mood swings, neuroticism and educational attainment traits. The rs55974014 SNP is located near several genes with neurological functions, including CRHR1 and NSF. Other SNPs close to this gene have been associated with intelligence51 and Parkinson’s disease52. Future colocalization analyses are warranted to assess the veracity of the same variant affecting multiple traits.

The genetic correlation between left-handedness and ambidexterity was low, which suggests that the genetic architecture underlying the two traits is different. Only 15 out of the 41 loci associated with left-handedness were associated with ambidexterity at marginal significance levels or lower (P < 0.05). However, tissue- and pathway-enrichment analyses indicated that just as for left-handedness, the central nervous system was implicated. Ambidexterity showed significant genetic correlations with multiple traits, particularly anthropometric and those involving pain and injuries. This suggests that reporting being able to write with both hands may be a result from injuries that led to the use of the other hand or may be due to increased injury risk. Future studies into the genetics of ambidexterity should include detailed phenotyping that considers the reasons leading to hand-use preference.

In contrast, left-handedness was not significantly genetically correlated with other (non-handedness) traits in our study. Given that previous studies have shown that the phenotypic correlation between left-handedness and most traits and diseases is low, it is perhaps unsurprising that the magnitude of most genetic correlations with left-handedness was low also. However, our lack of significant results was also partially a reflection of the large number of statistical tests performed and the conservative testing correction applied when estimating the genetic correlation between left-handedness and other traits. Nevertheless, we observed a clear inflation of the distribution of P values when compared to the null, which indicates that there is likely to be a small degree of genetic overlap between handedness and other traits. Among the suggestive genetic correlations (P < 0.05), we observed positive genetic correlations between left-handedness and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, which is consistent with previous observations of greater atypical hand dominance in patients with schizophrenia and in patients with bipolar disorder53,54.

The present study benefitted from having a large sample size that allowed the detection of dozens of novel variants of small effect on handedness. However, it is worth noting that the genetic correlations derived from GWAS summary statistics of left-handedness in the IHC, 23andMe and UKBB data were high but statistically different from one, potentially affecting the statistical power of the meta-analysis. These differences may have been due to the way data were collected in each of the cohorts. For example, in the UKBB, handedness data were obtained at up to three occasions, while this was not the case for the 23andMe and the IHC cohorts. Furthermore, genetic correlations with the IHC data may have been affected by the IHC including ambidextrous and left-handed individuals as cases.

In summary, we report the world’s largest GWAS meta-analysis of handedness. We showed that handedness is polygenic and found evidence that microtubule genes may play an essential role in lateralization. Loci mapped in the present study warrant further exploration of their potential role in neurological development and laterality.

Methods

As described below, we performed a meta-analysis on GWAS results from the IHC, the UKBB and 23andMe. Informed consent was provided by all participants. The research was approved by the research ethics committee of each of the individual studies.

Genome-wide association in the UKBB

The UKBB is a large long-term biobank study from the United Kingdom that aims to identify the contribution of genetic and environmental factors to disease. Detailed information on phenotyping and genotyping is presented elsewhere55. In brief, the UKBB recruited 502,647 individuals aged 37–76 years across the country and gathered information regarding their health and lifestyle, including handedness, via questionnaires. Genotype data from the UKBB are available for 487,411 participants. Genotypes were imputed by the UKBB against the UK10K reference panel using IMPUTE 2 (ref. 56). In addition to the quality control metrics performed centrally by the UKBB55, we defined a set of participants of European ancestry by clustering the first two principal components (PCs) derived from the genotype data. Using a K-means algorithm with K = 4, we identified a group of 463,023 individuals of European ancestry. From this group, 462,182 individuals (250,767 females) provided self-reported data on handedness. In total, 410,677 participants identified themselves as right-handed, 43,859 as left-handed and 7,646 as ambidextrous. The mean birth year of the participants was 1951 (s.d. = 8.04).

We tested 11,498,822 autosomal and X chromosome SNPs with MAF > 0.005 and info score of >0.4 for associations with handedness using BOLT-LMM, which implements a linear mixed model to account for cryptic relatedness and population structure. Sex and age were included as covariates in all models. We performed four analyses: (1) right- versus left-handed; (2) right versus ambidextrous; (3) right- versus left-handed (male only); and (4) right- versus left-handed (female only). Analyses of X chromosome genotypes were performed in BOLT-LMM, fitting sex as a covariate and coding the male genotypes as 0/2.

Genome-wide association in 23andMe

All individuals included in the analyses were research participants of the personal genetics company 23andMe, Inc., a private company. The phenotypes, including self-reported handedness, of the research participants were collected via online surveys. DNA extraction and genotyping were performed on saliva samples by the National Genetics Institute (NGI), a CLIA-licensed clinical laboratory and a subsidiary of the Laboratory Corporation of America. Samples were genotyped on one of five genotyping platforms. The v.1 and v.2 platforms were variants of the Illumina HumanHap550+ BeadChip, including about 25,000 custom SNPs selected by 23andMe, with a total of about 560,000 SNPs. The v.3 platform was based on the Illumina OmniExpress+ BeadChip, with custom content to improve the overlap with the v.2 array, with a total of about 950,000 SNPs. The v.4 platform was a fully customized array, including a lower redundancy subset of v.2 and v.3 SNPs with additional coverage of lower-frequency coding variation, and about 570,000 SNPs. The v.5 platform was an Illumina Infinium Global Screening Array (~640,000 SNPs) supplemented with ~50,000 SNPs of custom content. Samples that failed to reach a 98.5% call rate were re-analysed. Individuals whose analyses repeatedly failed were re-contacted by 23andMe customer service to provide additional samples.

For our standard GWAS, we restricted participants to a set of individuals who have a specified ancestry (predominantly European ancestry) determined through an analysis of local ancestry57. A maximal set of unrelated individuals was chosen for each analysis using a segmental IBD estimation algorithm58. Individuals were defined as related if they shared more than 700 cM IBD, including regions where the two individuals share either one or both genomic segments of IBD. This level of relatedness (roughly 20% of the genome) corresponds approximately to the minimal expected sharing between first cousins in an outbred population. In total, 1,012,146 individuals included in the analysis identified themselves as right-handed, 136,740 as left-handed and 29,991 as ambidextrous. The mean birth year of the participants was 1972.

We used Minimac3 to impute genotype data against a reference panel consisting of the May 2015 release of the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 haplotypes59 and the UK10K imputation reference panel60. We computed associations by logistic regression assuming additive allelic effects. We used the imputed dosages rather than best-guess genotypes and included covariates for age, sex, the top five PCs to account for residual population structure and indicators for genotype platforms to account for genotype batch effects. For associations on the X chromosome, male genotypes were coded as if they were homozygous diploid for the observed allele. For quality control of the GWAS results, we removed SNPs with rsq < 0.3, MAF < 0.005 and available sample size <20% of the total sample, as well as SNPs that had strong evidence of a platform batch effect. We also flagged logistic regression results that did not converge due to complete separation, identified by abs(effect) > 10 or s.e. > 10 on the log odds scale. Two analyses were performed: (1) right- versus left-handed and (2) right versus ambidextrous.

The IHC

The IHC is a large-scale collaboration between 32 cohorts (N = 125,612) with existing GWAS data to identify common genetic variants influencing handedness. Across all studies, the phenotype was collected by a questionnaire that asked either which hand was used for writing or for self-declared handedness. As these two measures are highly (~95%) concordant, not all studies reported on ambidexterity, and around 1–2% of participants reported being able to write with both hands12,61; both left-handed and ambidextrous individuals were classified as cases where this information was available. All cohorts were population samples with respect to handedness, thus combining the data from the 32 studies yielded 13,599 left-handed and 112,013 right-handed individuals (Supplementary Table 1).

All individuals were of self-declared European ancestry (confirmed by genotypic PCA in each cohort). Within each cohort, the genotypic data were imputed to Phase I and II combined HapMap CEU samples (build 36 release 22) with the exception of the Finnish Twin Cohort study, the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study and Nurses’ Health Study HPFS/NHS, the Netherlands Twin Registry (NTR), and TOP cohorts, which were imputed to 1000G Phase 3 V5 European population. Within each sample, genome-wide association analyses were conducted for both genotyped and imputed SNPs. The imputed genotypes were analysed using the dosage of an assumed effect allele under an additive model with covariates for year of birth and sex. Supplementary Table 21 shows the imputation and analysis software used in each of the cohorts.

To examine any potential impacts of including ambidextrous individuals as cases on the IHC, we ran a GWAS on the UKBB and 23andMe samples using both phenotypic definitions ((1) left versus right and (2) right versus left + ambidextrous) and computed the genetic correlations between the two analyses. The genetic correlations were r G 23andMe = 0.95 (s.e. = 0.003) and r G UKBB = 0.98 (s.e. = 0.006), which suggests that there is only a minor impact of the inclusion of ambidextrous individuals as cases on the GWAS results.

Meta-analysis of IHC, UKBB and 23andMe

A weighted Z-score meta-analysis was conducted with the METAL software62 using the summary GWAS statistics from each of the 32 IHC cohorts, UKBB and 23andMe. Given the large discrepancies between the number of cases and controls, we elected to weight each sample by the effective sample size for binary traits, defined as N eff = 4/(1/N cases + 1/N controls).

Before the meta-analysis, quality control thresholds were applied to each of the GWAS results from the individual studies (r 2 ≥ 0.3, MAF ≥ 0.005, P HWE ≥ 1 × 10–5). We used EasyQC63 to identify and remove SNPs that had allele frequencies that substantially differed from the Haplotype Reference Consortium. In total, up to 13,346,399 SNPs remained for the left-handedness meta-analysis. For the ambidexterity meta-analysis, only 23andMe and the UKBB datasets were used. This meta-analysis included up to 12,493,443 SNPs.

Tissue-expression and pathway analyses

Tissue-expression and pathway analyses were performed using DEPICT (v.1 rel. 194)25 implemented in the CTG-VL (beta 0.1)38 and MAGMA26 implemented in the functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations (FUMA) web application64 (accessed on 20 March 2020). DEPICT assesses whether genes in associated loci are highly expressed in any of the 209 medical subject heading (MeSH) tissue and cell-type annotations based on RNA sequencing data from the GTEx project32. Molecular pathways were constructed based on 14,461 gene sets from diverse database and data types, including Gene Ontology, the Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) and REACTOME. As input for DEPICT, we used independent SNPs (based on clumping with a r 2 (LD) between SNPs < 0.05 and 2-Mb windows) with P <1 × 10–5. MAGMA analyses were performed with the default options of FUMA using data 1000 Genomes Phase 3 for LD reference and GTEx v.8 (ref. 32) for the tissues-enrichment analysis. Enrichment analyses were performed for 15,483 pathways from MsigDB v.7.0 (ref. 65) and 54 tissues from GTEx. Associations with Benjamini–Hochberg FDR values of <5% are reported for both analyses.

Gene-based association analyses

Gene-based association analyses were carried out using S-MultiXcan27 and the SMR method27 implemented in the CTG-VL (beta 0.1)38. S-MultiXcan conducts a test of association between phenotypes and gene-expression levels predicted by data derived from the GTEx project32. In this study, we performed S-MultiXcan using prediction models of all the brain tissues available from the GTEx project. This included amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex BA24, caudate basal ganglia, cerebellar hemisphere, cerebellum, brain cortex, frontal cortex BA9, hippocampus, hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens basal ganglia, putamen basal ganglia, spinal cord cervical c-1 and substantia nigra samples. As a total of 14,501 genes expressed in different brain tissues were tested, the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold was set at P = 3.44 × 10–6.

SMR conducts a test for pleiotropic associations between the expression level of a gene and a complex trait using eQTL data and GWAS summary statistics. SMR uses a heterogeneity in dependent instruments (HEIDI) test to distinguish pleiotropy from linkage. A rejection (P < 0.05) of the null hypothesis (pleiotropy) indicates that the association of the SNP with gene expression and the trait of interest is probably due to linkage of that SNP with two distinct causal SNPs (one for the gene expression and one for the trait). In this study, we performed SMR using eQTL data derived from a meta-analysis of eQTL data from brain tissues (Brain-eMeta)31 that included GTEx32, CMC33 and ROSEMAP34. In addition to this, we carried out SMR analysis using PsychENCODE eQTL summary data from Wang et al.29 and Gandal et al.30. For each of the analyses, we report associations below a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold based on the number of genes tested that was up to 11,013 genes (that is, P < 4.54 × 10–6).

Genetic correlations

To test whether handedness shares a genetic background with other complex traits with available GWAS summary data, we used CTG-VL38, which implements LD score regression and contains a large database of summary GWAS statistics. In total, we assessed the genetic correlation of left-handedness and ambidexterity with 1,349 different traits. As many of the 1,349 traits tested are correlated between each other, hence not considered independent tests, we adopted a Benjamini–Hochberg FDR of <5% to account for multiple testing.

Heritability estimates

To estimate the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by SNPs, we used two statistical methods. REML, implemented in BOLT-LMM, was used to estimate the variance explained by additive effects of genotyped SNPs (h 2 g)66. Using a prevalence estimate of 10%, the observed h 2 g was transformed to SNP heritability on an unobserved continuous liability scale67. LD score regression was used to estimate the variance explained by all the SNPs using the GWAS summary statistics. Similar to REML, the observed h 2 g was transformed to the liability scale using a prevalence estimate of 10%.

To estimate the narrow-sense heritability, we fit a variance components model to estimate the proportion of phenotypic variance attributable to additive genetic effects (A), shared environmental effects (C) and individual environmental effects (E)37. We modelled the genetic sharing between close relative pairs using IBD information (as calculated by the KING software (v.2.1.6)68) on 20,277 sibling pairs (0.65 > IBD > 0.35) and 49,788 relative pairs with 0.3 > IBD > 0.8 from the UKBB study to estimate trait heritability. In the model, we also estimated a variance component due to a shared environment (siblings only), which made siblings potentially more similar in terms of handedness, and a unique environmental component, which did not contribute to similarity between relative pairs. Variance components were estimated using maximum likelihood using the OpenMx package69.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Professor John M. Starr and Professor Leena Peltonen have passed away. We have included them in memory of their work on this project. This research was conducted using the UK Biobank Resource (application number 12703). Access to the UK Biobank study data was funded by the University of Queensland (Early Career Researcher grant 2014002959 to N.W.). D.M.E. is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship (APP1137714). G.C.-P. is funded by an Australia Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE180100976). C.M.L. is supported by the Li Ka Shing Foundation, WT-SSI/John Fell funds and by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, by Widenlife and NIH (5P50HD028138-27). R.M. was supported by Estonian Research Council grant PUT PRG687 and institutional grant PP1GI19935 from Institute of Genomics, University of Tartu. M.I.M. funding support for this work comes from Wellcome (090532, 106130, 098381, 203141, 212259, 095101, 200837 and 099673/Z/12/Z) and the NIHR (NF-SI-0617-10090). N.W. is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship (APP1104818). S.E.M. was funded by a NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (APP1103623). I.B. is funded by Wellcome (WT206194). B.F. was supported by a grant from the Oak Foundation. We thank the research participants of 23andMe for making this study possible. Members of the 23andMe Research Team are as follows: M. Agee, A. Auton, R. K. Bell, K. Bryc, S. L. Elson, P. Fontanillas, N. A. Furlotte, B. Hicks, K. E. Huber, E. M. Jewett, Y. Jiang, A. Kleinman, K.-H. Lin, N. K. Litterman, M. H. McIntyre, K. F. McManus, J. L. Mountain, E. S. Noblin, C. A. M. Northover, S. J. Pitts, G. D. Poznik, J. F. Sathirapongsasuti, J. F. Shelton, S. Shringarpure, C. Tian, V. Vacic, X. Wang and C. H. Wilson. We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in the ALSPAC study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them and the entire ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses. The UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust (grant reference 102215/2/13/2) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. GWAS data were generated by Sample Logistics and Genotyping Facilities at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and LabCorp (Laboratory Corporation of America) using support from 23andMe. The Netherlands Twin Register acknowledges funding from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific research (NWO), including NWO-Grant 480-15-001/674: Netherlands Twin Registry Repository and the Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure (BBMRI–NL, 184.021.007 and 184.033.111); the KNAW Academy Professor Award (PAH/6635 to D.I.B.); Amsterdam Public Health (APH) and Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam (NCA); the European Community 7th Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013): ENGAGE (HEALTH-F4-2007-201413) and ACTION (9602768). We also acknowledge The Rutgers University Cell and DNA Repository cooperative agreement (NIMH U24 MH068457-06); the Collaborative Study of the Genetics of DZ twinning (NIH R01D0042157-01A1); the Developmental Study of Attention Problems in Young Twins (NIMH, RO1 MH58799-03); Major depression: stage 1 genome-wide association in population-based samples (MH081802); Determinants of Adolescent Exercise Behavior (NIDDK R01 DK092127-04); Grand Opportunity grants Integration of Genomics and Transcriptomics (NIMH 1RC2MH089951-01) and Developmental Trajectories of Psychopathology (NIMH 1RC2 MH089995); and the Avera Institute for Human Genetics, Sioux Falls, South Dakota (USA). The generation and management of GWAS genotype data for the Rotterdam Study (RS I, RS II, RS III) were executed by the Human Genotyping Facility of the Genetic Laboratory of the Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The GWAS datasets are supported by the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research NWO Investments (number 175.010.2005.011, 911-03-012), the Genetic Laboratory of the Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus MC, the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (014-93-015; RIDE2), and the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI)/Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Aging (NCHA), project number 050-060-810. We thank P. Arp, M. Jhamai, M. Verkerk, L. Herrera and M. Peters and C. Medina-Gomez for their help in creating the GWAS database, and K. Estrada, Y. Aulchenko and C. Medina-Gomez. for the creation and analyses of imputed data. We would like to thank K. Estrada, F. Rivadeneira, T. A. Knoch, M. Verkerk and A. Abuseiris. The Rotterdam Study is funded by the Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands Organization for the Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE), the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Ministry for Health, Welfare and Sports, the European Commission (DG XII), and the Municipality of Rotterdam. The authors are very grateful to the study participants, the staff from the Rotterdam Study (particularly L. Buist and J. H. van den Boogert) and the participating general practitioners and pharmacists. We thank all study participants as well as everybody involved in the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study (HBCS). The Helsinki Birth Cohort Study has been supported by grants from the Academy of Finland, the Finnish Diabetes Research Society, the Folkhälsan Research Foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, Finska Läkaresällskapet, the Juho Vainio Foundation, the Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, the University of Helsinki, the Ministry of Education, the Ahokas Foundation, and the Emil Aaltonen Foundation. In addition, we thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study for their valuable contributions, and the Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School This work was supported in part by NIH R01 CA49449, P01 CA87969, UM1 CA186107 and UM1 CA167552. The KORA study was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Zentrum München—German Research Center for Environmental Health, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and by the State of Bavaria. Furthermore, KORA research was supported within the Munich Center of Health Sciences (MC-Health), Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, as part of LMUinnovativ. We are very grateful to all DNBC families who took part in the study. We would also like to thank everyone involved in data collection and biological material handling. The DNBC was established based on a major grant from Danish National Research Foundation. Additional support for the DNBC was obtained from the Pharmacy Foundation, the Egmont Foundation, the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Augustinus Foundation, and the Health Foundation. The DNBC 7-year follow-up was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation (195/04) and the Danish Medical Research Council (SSVF 0646). The DNBC biobank is a part of the Danish National Biobank resource, which is supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Phenotype and genotype data collection in the Finnish Twin Cohort has been supported by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, the Broad Institute, ENGAGE – European Network for Genetic and Genomic Epidemiology, FP7-HEALTH-F4-2007, grant agreement number 201413, National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grants AA-12502, AA-00145, and AA-09203 to R J Rose and AA15416 and K02AA018755 to D M Dick) and the Academy of Finland (grants 100499, 205585, 118555, 141054, 264146, 308248, and 312073 to J.K.). J.K. acknowledges support by the Academy of Finland (grants 265240, 263278). E.V. acknowledges support by the Academy of Finland (grant 314639). Finally, we thank the participants of all the cohorts for their valuable contribution. This publication is the work of the authors, and S.E.M. and D.M.E. will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Study design: C.M.L., R.M., B.M.N., D.M.E., S.E.M. Manuscript preparation: G.C.-P., C.M.L., R.M., B.M.N., D.M.E., S.E.M. Meta-analysis and downstream analyses: G.C.-P. Individual study design, analysis or data collection: N.E., D.A.H., J.Y.T. (23andMe); P.D., W.L.M., L. Paternoster, G.D.S., B.S.P., N.J.T. (ALSPAC); D.M.E., J.P.K. (ALSPAC, UKBB); F.A., D.M.D. (COGA); J.S.B., Z.K., P.M.-V., V.M., P.V., G. Waeber, D.W. (COLAUS); C.H., J.E.H., O.P. (CROATIA-Korcula); H.C., I.R., A.F.W. (CROATIA-Vis); O.A.A., M.P.B., I.G., T.F.H., A.M.H., B.K., S.H.M., R.A.O., D.R., K.S., H.S, S.S., G.T., T.W. (deCODE); H.A.B., B.F., F.G., M. Melbye (DNBC); T.E., R.M., A.M., L.M., M.N., M.T.-L. (EGCUT); M.M.B.B. (EMC); I.B., K.-T.K., R.J.F.L., N.J.W., J.H.Z. (EPIC); J.N.H., C.P. (FRAMINGHAM); K.H., J.K., T.P., E.V. (FTC); J.G.E., J.L., K.R., E.W. (HBCS); E.A., C.G., N.K., H.-E.W. (KORA); G.D., I.J.D., M.L., J.M.S. (LBC); A.A.H., S.A.M., P.P.P. (MICROS); B.W.J.H.P., J.H.S. (NESDA); C.M.L., M.I.M., A.P., L. Peltonen, I.P., S.R. (NFBC66); J.H., P.K., X.L., M.X. (NHS/HPFS); D.I.B., E.J.C.d.G., J.-J.H., J.M.V., G. Willemsen (NTR); D.L.D., S.D.G., N.G.M., S.E.M., D.R.N., M.J.W. (QIMR); M.A.I., C.M.-G., F.R., A.G.U., C.M.v.D., F.J.A.v.R. (RS); J.W.S. (STEP); K.S.O. (TOP); G.C.-P., L.-D.H., N.W. (UKBB); L.F.C., M. Mangino, N.S., T.D.S. (UK TWIN); D.I.C., G.P., W.L.M., B.M.N. Manuscript review: all the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

G.C.-P., N.E., D.A.H. and J.Y.T. are employees of 23andMe, Inc., and hold stock or stock options in 23andMe. S.H.M., K.S., H.S., S.S. and G.T. are employees of deCODE Genetics/Amgen. M.I.M. is a Wellcome Senior Investigator and a NIHR Senior Investigator. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. M.I.M. has served on advisory panels for Pfizer, NovoNordisk and Zoe Global; has received honoraria from Merck, Pfizer, NovoNordisk and Eli Lilly; has stock options in Zoe Global; has received research funding from Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, NovoNordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, Servier and Takeda. As of June 2019, he is an employee of Genentech, and holder of Roche stock. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00956-y.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to D.M.E. or S.E.M.

Peer review information Primary handling editor: Charlotte Payne.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Data availability

GWAS summary statistics of the meta-analysis of the UKBB, IHC and 23andMe data for the top 10,000 independent SNPs as well as summary statistics of the meta-analysis between the UKBB and IHC data for all the SNPs are available at https://evansgroup.di.uq.edu.au/gwas-results.html. Access to the full summary statistics from the 23andMe sample (for all SNPs) can be obtained by qualified researchers through a data transfer agreement with 23andMe that protects participant privacy. Please contact 23andMe at https://research.23andme.com/dataset-access for more information.

Code availability

The code used to perform the meta-analysis will become available on GitHub upon publication.

References

- 1.Hepper PG, McCartney GR, Shannon EA. Lateralised behaviour in first trimester human foetuses. Neuropsychologia. 1998;36:521–534. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parma V, Brasselet R, Zoia S, Bulgheroni M, Castiello U. The origin of human handedness and its role in pre-birth motor control. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16827-y. 16804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazenby R. Skeletal biology, functional asymmetry and the origins of ‘handedness’. J Theor Biol. 2002;218:129–138. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2002.3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gumustekin K, et al. Handedness and bilateral femoral bone densities in men and women. Int J Neurosci. 2004;114:1533–1547. doi: 10.1080/00207450490509186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steele J, Mays S. Handedness and directional asymmetry in the long bones of the human upper limb. Int J Osteoarchaeologoy. 1995;5:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knecht S, et al. Handedness and hemispheric language dominance in healthy humans. Brain. 2000;123:2512–2518. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.12.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pujol J, Deus J, Losilla JM, Capdevila A. Cerebral lateralization of language in normal left-handed people studied by functional MRI. Neurology. 1999;52:1038–1043. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papadatou-Pastou M, et al. Human handedness: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2020;146:481–524. doi: 10.1037/bul0000229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papadatou-Pastou M, Martin M, Munafo MR, Jones GV. Sex differences in left-handedness: a meta-analysis of 144 studies. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:677–699. doi: 10.1037/a0012814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Annett M. Lef, Right, Hand and Brain: the Right Shift Theory. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McManus IC. Handedness, language dominance and aphasia: a genetic model. Psychol Med Monogr Suppl. 1985;8:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medland SE, Dufy DL, Wright MJ, Gefen GM, Martin NG. Handedness in twins: joint analysis of data from 35 samples. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:46–53. doi: 10.1375/183242706776402885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francks C, et al. A genomewide linkage screen for relative hand skill in sibling pairs. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:800–805. doi: 10.1086/339249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Agtmael T, Forrest SM, Del-Favero J, Van Broeckhoven C, Williamson R. Parametric and nonparametric genome scan analyses for human handedness. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:779–783. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warren DM, Stern M, Duggirala R, Dyer TD, Almasy L. Heritability and linkage analysis of hand, foot, and eye preference in Mexican Americans. Laterality. 2006;11:508–524. doi: 10.1080/13576500600761056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Somers M, et al. Linkage analysis in a Dutch population isolate shows no major gene for left-handedness or atypical language lateralization. J Neurosci. 2015;35:8730–8736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3287-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medland SE, et al. Opposite effects of androgen receptor CAG repeat length on increased risk of left-handedness in males and females. Behav Genet. 2005;35:735–744. doi: 10.1007/s10519-005-6187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francks C, et al. LRRTM1 on chromosome 2p12 is a maternally suppressed gene that is associated paternally with handedness and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:1129–1139. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scerri TS, et al. PCSK6 is associated with handedness in individuals with dyslexia. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:608–614. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Kovel CGF, Francks C. The molecular genetics of hand preference revisited. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5986. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42515-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiberg A, et al. Handedness, language areas and neuropsychiatric diseases: insights from brain imaging and genetics. Brain. 2019;142:2938–2947. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bulik-Sullivan B, et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1236–1241. doi: 10.1038/ng.3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bulik-Sullivan BK, et al. LD score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2015;47:291–295. doi: 10.1038/ng.3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Jong S, et al. Common inversion polymorphism at 17q21.31 affects expression of multiple genes in tissue-specific manner. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:458. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pers TH, et al. Biological interpretation of genome-wide association studies using predicted gene functions. Nat Commun. 2015;6 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6890. 5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Leeuw CA, Mooij JM, Heskes T, Posthuma D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barbeira AN, et al. Integrating predicted transcriptome from multiple tissues improves association detection. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1007889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.UniProt Consortium. The universal protein resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D190–D195. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang D, et al. Comprehensive functional genomic resource and integrative model for the human brain. Science. 2018;362:eaat8464. doi: 10.1126/science.aat8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gandal MJ, et al. Transcriptome-wide isoform-level dysregulation in ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Science. 2018;362:eaat8127. doi: 10.1126/science.aat8127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qi T, et al. Identifying gene targets for brain-related traits using transcriptomic and methylomic data from blood. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2282. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04558-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.GTEx Consortium. The Genotype–Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fromer M, et al. Gene expression elucidates functional impact of polygenic risk for schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1442–1453. doi: 10.1038/nn.4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng B, et al. An xQTL map integrates the genetic architecture of the human brain’s transcriptome and epigenome. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1418–1426. doi: 10.1038/nn.4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun T, et al. Early asymmetry of gene transcription in embryonic human left and right cerebral cortex. Science. 2005;308:1794–1798. doi: 10.1126/science.1110324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ocklenburg S, et al. Epigenetic regulation of lateralized fetal spinal gene expression underlies hemispheric asymmetries. eLife. 2017;6:e22784. doi: 10.7554/eLife.22784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visscher PM, et al. Assumption-free estimation of heritability from genome-wide identity-by-descent sharing between full siblings. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cuellar-Partida G, et al. Complex-Traits Genetics Virtual Lab: a community-driven web platform for post-GWAS analyses. Preprint at bioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/518027. [DOI]

- 39.Vuoksimaa E, Koskenvuo M, Rose RJ, Kaprio J. Origins of handedness: a nationwide study of 30,161 adults. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:1294–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kapitein LC, Hoogenraad CC. Building the neuronal microtubule cytoskeleton. Neuron. 2015;87:492–506. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lasser M, Tiber J, Lowery LA. The role of the microtubule cytoskeleton in neurodevelopmental disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:165. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirnstein M, Hugdahl K. Excess of non-right-handedness in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of gender effects and potential biases in handedness assessment. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:260–267. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.137349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Preslar J, Kushner HI, Marino L, Pearce B. Autism, lateralisation, and handedness: a review of the literature and meta-analysis. Laterality. 2014;19:64–95. doi: 10.1080/1357650X.2013.772621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Penazzi L, Bakota L, Brandt R. Microtubule dynamics in neuronal development, plasticity, and neurodegeneration. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2016;321:89–169. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang Q, Yang H, Wang M, Wei H, Hu F. Role of microtubule-associated protein in autism spectrum disorder. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34:1119–1126. doi: 10.1007/s12264-018-0246-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marchisella F, Cofey ET, Hollos P. Microtubule and microtubule associated protein anomalies in psychiatric disease. Cytoskeleton. 2016;73:596–611. doi: 10.1002/cm.21300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahn K, et al. High rate of disease-related copy number variations in childhood onset schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:568–572. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cantor RM, et al. Replication of autism linkage: fine-mapping peak at 17q21. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:1050–1056. doi: 10.1086/430278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yonan AL, et al. A genomewide screen of 345 families for autism-susceptibility loci. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:886–897. doi: 10.1086/378778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trampush JW, et al. GWAS meta-analysis reveals novel loci and genetic correlates for general cognitive function: a report from the COGENT consortium. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:1651–1652. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hill WD, et al. A combined analysis of genetically correlated traits identifies 187 loci and a role for neurogenesis and myelination in intelligence. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:169–181. doi: 10.1038/s41380-017-0001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simon-Sanchez J, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dragovic M, Hammond G. Handedness in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of evidence. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;111:410–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ravichandran C, Shinn AK, Ongur D, Perlis RH, Cohen B. Frequency of non-right-handedness in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2017;253:267–269. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sudlow C, et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44:955–959. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Durand EY, Chuong BD, Mountain JL, Macpherson JM. Ancestry composition: a novel, efficient pipeline for ancestry deconvolution. Preprint at bioRxiv. 2014 doi: 10.1101/010512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henn BM, et al. Cryptic distant relatives are common in both isolated and cosmopolitan genetic samples. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.UK10K Consortium et al. The UK10K project identifies rare variants in health and disease. Nature. 2015;526:82–90. doi: 10.1038/nature14962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perelle IB, Ehrman L. An international study of human handedness: the data. Behav Genet. 1994;24:217–227. doi: 10.1007/BF01067189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Winkler TW, et al. Quality control and conduct of genome-wide association meta-analyses. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:1192–1212. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Watanabe K, Taskesen E, van Bochoven A, Posthuma D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liberzon A, et al. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1739–1740. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loh PR, et al. Efficient Bayesian mixed-model analysis increases association power in large cohorts. Nat Genet. 2015;47:284–290. doi: 10.1038/ng.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee SH, Wray NR, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. Estimating missing heritability for disease from genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Manichaikul A, et al. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2867–2873. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neale MC, et al. OpenMx 2.0: extended structural equation and statistical modeling. Psychometrika. 2016;81:535–549. doi: 10.1007/s11336-014-9435-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

GWAS summary statistics of the meta-analysis of the UKBB, IHC and 23andMe data for the top 10,000 independent SNPs as well as summary statistics of the meta-analysis between the UKBB and IHC data for all the SNPs are available at https://evansgroup.di.uq.edu.au/gwas-results.html. Access to the full summary statistics from the 23andMe sample (for all SNPs) can be obtained by qualified researchers through a data transfer agreement with 23andMe that protects participant privacy. Please contact 23andMe at https://research.23andme.com/dataset-access for more information.

The code used to perform the meta-analysis will become available on GitHub upon publication.