Abstract

Vector control and effective case management are currently the backbone strategies of malaria control. Kitgum district, an area of perennial holoendemic malaria transmission intensity in Northern Uganda, appears to have experienced a malaria epidemic in 2015. This study aimed to describe the malaria trends in Kitgum General Hospital from 2011 to 2017 in relation to climatic factors and the application of population-based malaria control interventions. Hospital records were examined retrospectively to calculate malaria normal channels, malaria cases per 1000 population, test positivity rates (TPR) and to enumerate pregnancy malaria, hospitalizations and deaths. Climatic factors (humidity, temperature and rainfall) and population-based malaria control interventions that had been applied during this period were described. Kitgum district experienced an epidemic between the years 2015 and 2016; the malaria burden rose above the established normal channels. At its peak the number of malaria cases attending KGH was over 20 times above the normal channels. The total number of cases per 1000 population increased from 7 in 2014 to 113 in 2015 and 114 in 2016 (p value for trend < 0.0001). Similarly, TPR increased from 10.5% to 54.6% between 2014 and 2016 (p value for trend < 0.0001). This trend was also observed for malaria attributable hospitalizations, and malaria in pregnancy. There were no significant changes in any of the climatic factors assessed (p value=0.92, 0.99, 0.52 for relative humidity, max temperature, and rainfall, respectively). The malaria upsurge occurred in conjunction with a general decline in the use and application of malaria control interventions. Specifically, indoor residual spraying was interrupted in 2014. In response to the epidemic, IRS was reapplied together with mass distribution of long-lasting insecticide treated nets (LLINs) in 2017. Subsequently, there was a decline in all malaria indicators. The epidemic in Kitgum occurred in association with the interruption of IRS and appears to have abated following its re-introduction alongside LLINs. The study suggests that to enable malaria elimination in areas of high malaria transmission intensity, effective control measures may need to be sustained for the long-term.

Keywords: Malaria elimination, Resurgence, IRS, Vector control, Malaria epidemiology

1. Introduction

Malaria remains a major public health problem and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in sub Saharan Africa (Alonso et al., 2011; Nkumama et al., 2017). In 2015, there were an estimated 212 million new cases and 429,000 malaria deaths, the majority (> 90%) of which, occurred in Africa (World Health Organisation (WHO), 2016). In Uganda, the Ministry of Health estimates that malaria is responsible for 30–50% of outpatient visits, 15–20% hospital admissions, and despite the recent decline in incidence, it still remains a leading cause of inpatient deaths (MOH, 2015). Approximately 8–13 million cases are reported annually (Kamya et al., 2015; Tukei et al., 2017; Yeka et al., 2012). Nearly 95% of the country has stable P. falciparum transmission, with Anopheles gambiae s.I. and A.funestus, being the dominant species in most locations (Yeka et al., 2012).

In the absence of a highly effective vaccine, malaria control depends on vector control strategies and effective case management with artemisinin based combination therapies (ACTs) (Hemingway et al., 2016; Katureebe et al., 2016; MACDONALD, 1956; malERA Consultative Group on Drugs, 2011; Penny et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2013; Smith Gueye et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2010). These control measures are thought to have accounted for the reduction in the global incidence of, and mortality due to malaria since 2010 (Marsh, 2016; Nkumama et al., 2017; World Health Organisation (WHO), 2016). This success was exemplified in multiple areas in Africa such as coastal Kenya, the Gambia, Zambia, and Ethiopia, lending support to the idea that regional malaria elimination may be possible. In Uganda, the overall prevalence of malaria reduced from 47% in 2009 to approximately 19% in 2016 (MOH, 2015; Talisuna et al., 2015; Tukei et al., 2017), a change largely attributable to intensified malaria control. The major tools employed included countrywide distribution of long-lasting insecticide treated nets (LLINs), indoor residual spraying (IRS) of insecticides, treatment with ACTs, and intermittent preventive therapy (IPT) for high-risk groups (Oguttu et al., 2017; Talisuna et al., 2015). However, in 2015, Kitgum and the surrounding districts of Northern Uganda reported a spike in malaria cases (Malaria outbreak in northern Uganda, 2016).

Malaria transmission is influenced by climatic factors such as rainfall, temperature and humidity (Martens et al., 1995). Changes in these factors have precipitated malaria epidemics in some regions and several studies have attempted to use such changes to predict malaria epidemics (Darkoh et al., 2017; Teklehaimanot et al., 2004; Woube, 1997). This paper aimed to describe the malaria epidemic in Northern Uganda by examining the trends in Kitgum General Hospital from 2011 to 2017 in relation to climatic factors and population-based malaria control interventions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and site

This was a retrospective record-based study of outpatient and in-patient malaria at Kitgum General Hospital (KGH) from 2011 to 2017.

Kitgum district is located in Northern Uganda. It is bordered by South Sudan and Lamwo district to the north, Pader district to the west, Kotido and Kaabong districts to the east and Agago to the south. The land is generally flat with a population density of about 51 persons per Km2 and an average household size of 5.1 persons. The primary economic activity is subsistence farming complemented with small-scale animal husbandry. Malaria transmission occurs all year-round peaking following the onset of the rainy season. The district is served by 2 hospitals, Kitgum general Hospital (KGH) and St. Josephs’ Hospital. KGH is a public hospital that provides healthcare services at no cost to all patients while St. Josephs’ is a for-profit missionary hospital. Due to the high levels of poverty in the region KGH is more representative of the district trends.

2.2. Data collection

Patients presenting to KGH with fever or history of fever are usually investigated for malaria by microscopy or by the P. falciparum (HRP-2) Rapid Diagnostic test (RDT). Information on the total number of patients that utilized KGH laboratory services between 2011 and 2017 and the proportion testing positive for malaria was extracted from relevant registers. The total number of hospitalizations and malaria attributable hospitalizations together with the number of patients with malaria in pregnancy and the total number of malaria associated deaths was also determined by examination of the relevant in-patient hospital records.

In parallel, we obtained data on the implementation and reported coverage of multiple malaria control interventions (IRS, LLIN and IPTp) in the district over the study period. Data on interventions and coverage was obtained from KGH and published reports on the district. (Mass Distribution of Long Lasting Insecticidal Nets for Universal Coverage in Uganda Evaluation Report, 2015; Ministry of Health Uganda, 2015; Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2016; Uganda Ministry of Health, 2014; USAID, 2016, 2015, 2007). The average monthly rainfall (mm), maximum and minimum temperatures (°C) and the average relative humidity (%) taken at 9:00 am and 3:00 pm were obtained from the National Meteorological Authority weather station, Kitgum zone, at Latitude 03053'N, Longitude 32053'E and altitude 937.3m above sea level. The average monthly values within a year were used to examine the relationship with malaria.

2.3. Data analysis

The data were entered into a Microsoft Excel 2013 database and visualized using Graph Pad Prism 6.05 for windows. STATA version 14.0 was used for statistical analysis. The monthly and annual trends of test positivity rates (TPR), malaria cases and hospitalization were examined. The annual number of malaria cases per 1000 population were determined using the estimated district population (UBOS, 2014). Hospitalizations attributable to malaria were plotted in two age categories 0–4.9 years and ≥5 years. The monthly number of cases in the years 2011–2014 were used to establish malaria epidemic threshold limits (malaria normal channels), as published before (World Health Organisation (WHO), 2003). The years 2015–2017 were monitored and the occurrence of an epidemic declared if the number of malaria cases rose above the 3rd quartile range. The number of patients with malaria in pregnancy and total deaths were also reported. Annual differences in climatic factors were examined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukeys post hoc analysis. A p value ≤0.05 was considered significant. Spearman’s rank correlations analysis was used to evaluate the independent correlation between the number of malaria cases and climatic factors. A multivariate regression modal was used to evaluate the relationship between multiple independent variables (rainfall (mm), maximum and minimum temperatures (°C) and the average relative humidity (%) taken at 9:00 am and 3:00 pm) and the monthly number of malaria cases. Briefly, all climatic factors were considered as independent variables. A backward stepwise method was used to build the multi-variate regression model and a p value ≤0.05 considered as a significant association. Interaction was assessed using a Chunk test. Any dropped variables were assessed for their confounding effect using a 10% difference between the adjusted and unadjusted exponent-coefficients.

3. Results

3.1. Trends of malaria burden in Kitgum general hospital

A total of 153, 643 patients were tested for malaria in the KGH laboratories over the seven-year period. Overall, 60,756 (40.0%) tested positive, and malaria was a major cause of morbidity accounting for 21.0–44.1% of all hospitalizations (Table 1). In Kitgum, malaria transmission occurs throughout the year albeit with monthly variations. However, a significant rise in all malaria parameters was observed in 2015 and remained high through 2016. Malaria parameters studied subsequently declined in 2017. The TPR was on a downward trend from 19.2% in 2011 to 10.5% in 2014. However, the TPR increased to 51.5% in 2015. Subsequently, the TPR declined from 54.6% in 2016 to 38.2% in 2017. Similarly, the number of malaria cases per 1000 population ranged from 6 to 10 cases per 1000 population between 2011 and 2014.

Table 1.

Summary of the annual changes in test positivity rate, malaria incidence, hospitalizations, malaria in pregnancy and deaths from Kitgum general hospital 2011–2017.

| Year | Test positivity rate | Malaria cases per 1000 population | Total hospitalizations | % of hospitalizations with malaria | Total Hospitalizations per 1000 population | Malaria in pregnancy | Total deaths | % of deaths attributed to malaria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 19.2 | 10 | 8771 | 31.6 | 45 | 296 | 198 | 21.7 |

| 2012 | 12.6 | 6 | 8546 | 42.2 | 43 | 241 | 181 | 29.3 |

| 2013 | 11.9 | 7 | 9023 | 39.6 | 44 | 356 | 169 | 21.8 |

| 2014 | 10.5 | 7 | 10238 | 21.0 | 50 | 179 | 199 | 8.0 |

| 2015 | 51.5 | 113 | 21918 | 44.1 | 106 | 663 | 256 | 19.5 |

| 2016 | 54.6 | 114 | 24600 | 39.3 | 117 | 1228 | 375 | 22.9 |

| 2017 | 38.2 | 34 | 14812 | 34.8 | 69 | Missing | 323 | 17.3 |

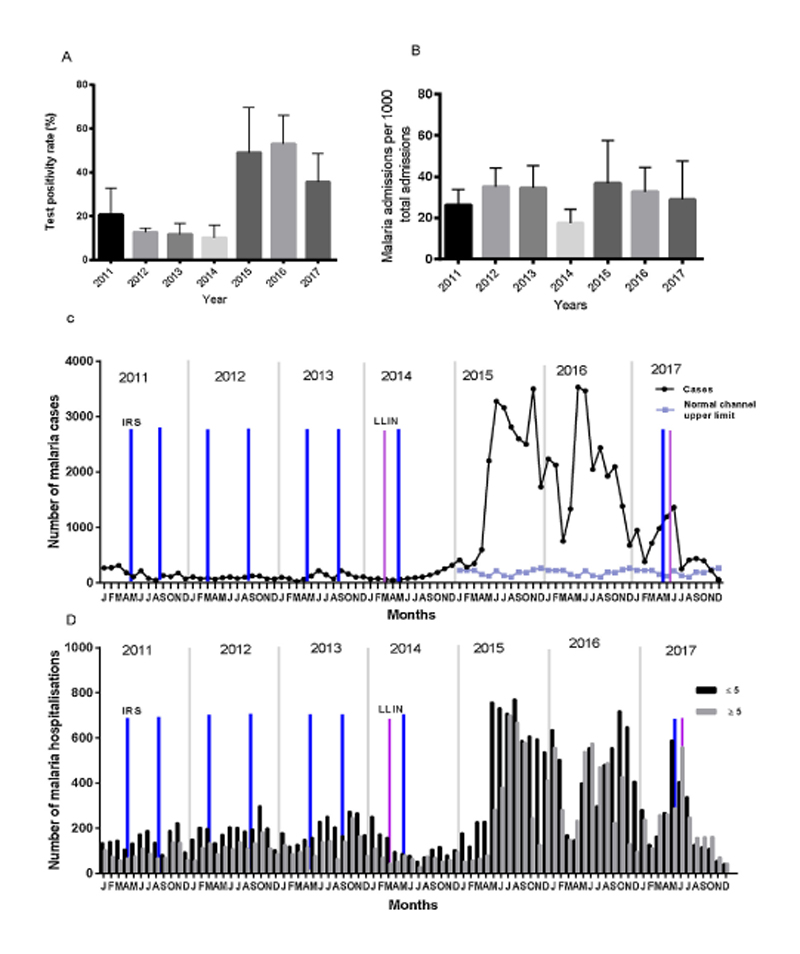

The malaria incidence calculated using cases reporting to the hospital rose from 7 per 1000 population in 2014 to 113 per 1000 population in 2015. The burden remained high at 114 per 1000 population in 2016. In 2017, this incidence declined to 34 cases per 1000 population. The number of patients with malaria in pregnancy rose from 9 cases in 2014 to 663 in 2015 and 1228 cases in 2016. Malaria attributable hospitalizations rose 2-fold from 21.0% in 2014 to 44.1% in 2015 and 39.3% in 2016, and in 2017 it was 34.8% (Table 1). Over the period 2015–2016 the number of cases exceeded the upper threshold as defined by the malaria normal channels (see Section 2.3), indicating the occurrence of an epidemic (Fig. 1). Essentially, all the malaria indicators (number of malaria cases, TPR, malaria hospitalizations and malaria in pregnancy) analyzed showed a significant positive increase between 2014 and 2016 (p value for trend < 0.0001).

Fig 1. Trends of malaria over the study period. A) Mean (+SD) annual test positivity rate, B) Mean (+SD) number of malaria admissions. C) Monthly trend of malaria cases overlaid with the normal channel upper limit calculated using numbers reported from 2011–2014. D) Number of monthly admissions due to malaria shown for the two age categories 0–4.9 years and ≥5 years. The approximate time points of population-based malaria control interventions including district wide indoor residual spraying (IRS; blue bars) and mass distribution of long -lasting insecticide treated nets (LLINs; purple bars) are indicated (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

3.2. The role of climatic factor variations in causation of the malaria epidemic

The annual means of the climatic factors including the average monthly rainfall (mm), maximum and minimum temperatures (°C) and the average relative humidity (%) were evaluated for each year. The highest amount of rainfall was received in 2013 with a monthly average of 147mm (SD 116.1). The year 2013 also had the highest relative humidity. The hottest year was 2016 with an average monthly maximum temperature of 31.8 °C (SD 2.3) and the lowest monthly average rainfall of 79mm (SD 50.2) (Table 2). There were no significant differences in the means of the climatic factors across the years (Rainfall, F = 0.86, p value 0.52. Maximum temp ° C F = 0.13, p value 0.99, relative humidity at 9:00 am F = 0.31, p value 0.92; and relative humidity at 3:00 p.m. F = 0.15, p value=0.98. Only minimum temp ° C F = 2.35, p value = 0.03 showed a significant ANOVA test. A Tukeys post hoc analysis showed no significant difference between the years. There were no abrupt or any major changes in the climatic factors over the years of study. Therefore, we concluded that the malaria epidemic was not precipitated by changes in any of the climatic factors.

Table 2.

Summary of mean monthly changes in climatic factors over the study years 2011–2017.

| Years | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean monthly Rainfall (mm) (SD) | 90.5 (66.4) | 105.2 (89.3) | 147.0 (116.1) | 114.5 (82.8) | 113.2 (76.3) | 79.3 (50.1) | 96.38 (72.0) |

| Mean monthly maximum temperature (° C) (SD) | 31.2 (2.3) | 31.5 (2.5) | 31.3 (1.6) | 31.8 (2.00) | 31.86 (2.4) | 31.8 (2.3) | 31.8 (2.6) |

| Mean monthly minimum temperature (° C) (SD) | 18.2 (1.1) | 18.0 (1.4) | 17.8 (0.9) | 17.8 (1.1) | 17.3 (1.7) | 16.5 (1.6) | 16.99 (1.7) |

| Mean monthly relative humidity 9:00am (%) (SD) | 73 (11.7) | 74 (13.7) | 78 (7.3) | 74 (12.1) | 77 (77.5) | 76 (11.0) | 79 (9.9) |

| Mean monthly relative humidity 3:00pm (%) (SD) | 43 (10.8) | 44 (12.1) | 44 (8.1) | 43 (10.3) | 44 (12.6) | 43 (11.5) | 46.8 (10.7) |

3.3. The relationship between climatic factors and malaria trends

Spearman’s ranks correlation analysis revealed that minimum temperature (°C) was the only variable independently correlating with the number of malaria cases (r = -0.33 [95%CI -0.51, -0.12], p value = 0.002). All other variables {rainfall (r = -0.0059 [95% CI -0.23, 0.21], p value = 0.95), maximum temperature (r = -0.019 [95%CI -0.24, 0.20], p value = 0.86), relative humidity (9:00am) (r = 0.17 [95% CI -0.04-0.38], p value = 0.103), relative humidity (3:00pm) (r = 0.071 [95%CI -0.15, 0.28], p value = 0.52)} were not significantly correlated with the number of malaria cases. By multi-variate analysis, maximum temperature (°C) (p value = 0.001), minimum temperature (°C) (p value = 0.007) and relative humidity (%) at 9:00am (p value = 0.005) and relative humidity (%) at 3:00pm (p value 0.006) were jointly associated with the number of malaria cases with rainfall confounding all the four variables (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis showing the association between climatic factors and the number of malaria cases.

| Malaria cases | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

| Variable | Coefficient | p value | 95% C. I | Coefficient | p value | 95% C. I |

| Max temperature (°C) | 523.7 | 0.002 | 200.9 – 846.6 | 543.4 | 0.001 | 223.4–863.3 |

| Min temperature (°C) | – 259.8 | 0.002 | – 418.408 - -101.1 | – 226.2 | 0.007 | – 387.7 - -64.6 |

| Relative humidity (9:00) | 92.6 | 0.013 | 20.202 – 165.1 | 106.0 | 0.005 | 32.7–179.2 |

| Relative humidity (3:00) | 47.9 | 0.015 | 9.559 – 86.3 | 54.42 | 0.006 | 15.7–93.0 |

| Rainfall (mm) | – 3.2 | 0.091 | – 6.9–0.5 | |||

There was no interaction between the independent variables. Rainfall confounded all the variables in the model. Data from each year was compiled together.

3.4. Documentation of malaria control interventions during the study period

In Uganda, the malaria reduction strategic plan (UMRSP) 2014–2020 is currently guiding control efforts (Uganda Ministry of Health, 2014). The program focuses on vector control strategies (IRS, LLINS and larval source management along with entomological monitoring). Second is the use and access to effective malaria treatment both in health centres and in the community. Finally, advocacy, social mobilization and information education (BCC) (Uganda Ministry of Health, 2014). Over the study period (2011–2017), the following major malaria control interventions were implemented in the region.

-

1)

Indoor residual spraying using different insecticides: This activity was funded largely by the United States of America President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI). In Kitgum, implementation of IRS began in 2007 using lambda cyhalothrin (ICON 10% WP) and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) (USAID, 2007). Spraying was initially carried out in the internally displaced peoples’ camps established during the 20-year Lord’s Resistance Army conflict in Northern Uganda. Biannual IRS begun in 2009 and was halted in 2014 after observing some success in malaria control (USAID, 2015). During the study years, pyrethroids were initially used in 2011 however due to reports of insecticide resistance within the region, carbamates were used in all subsequent IRS rounds (Abeku et al., 2017; Okia et al., 2018). In 2017, a single round of IRS was sprayed in response to reports of a malaria upsurge. Actellic® 300CS, an organophosphate based on Pirimiphos-methyl, was the pesticide of choice. It has a long residual effect over 6 months on wood or concrete surfaces. The coverage of IRS activities was over 90% of the entire district for all spraying rounds (USAID, 2016, 2015).

-

2)

Insecticide treated bed net distribution, coverage and use: In 2013, mass distribution of LLINs for the entire nation was undertaken by the Ministry of Health in Uganda, with a target of one LLIN for every two residents. In Kitgum, LLINs were distributed at the beginning of the year 2014 with a reported coverage of 92% (145,319/146,000 nets), (Mass Distribution of Long Lasting Insecticidal Nets for Universal Coverage in Uganda Evaluation Report, 2015). The malaria indicator survey (MIS) 2014/15 (December 2014–January 2015) estimated that 94.2% of households had at least one LLIN and the average number of nets per household was 2.7 (Ministry of Health Uganda, 2015). Later, the Uganda demographic health survey (UDHS) 2016 reported that an estimated 41.2% of households had at least one LLIN for every two persons in each house hold. The percentage of households with at least one LLIN was 80.7% and the average number of nets per home was 1.7 (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2016). However only 67.8% of children under the age of 5 years were found to have slept under a mosquito net the night before the survey. In 2017 another mass distribution campaign was undertaken in the region. The targeted coverage was at least one net for every 2 individuals. All pregnant women attending antenatal care were given an LLIN. The earlier malaria indicator survey of 2014/15 estimated that about 79.9% of pregnant women sleep under a LLIN (Ministry of Health Uganda, 2015). The Demographic Health Survey 2016 found that within the region an estimated 68.2% of pregnant women slept under a LLIN (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2016). A total of 1441 pregnant women attending Kitgum General Hospital for antenatal care received a LLIN in 2017, 2197 nets were received in 2016, 1163 in 2015, 779 in 2014, and 1365 in 2012. The records for 2011 and 2013 were incomplete.

-

3)

Intermittent preventive treatment (IPTp) with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine for pregnant women: The demographic health survey of 2016 estimated that 69.9% of pregnant women received at least one or more doses of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine while only 37.2% and 16.2% took at least 2 and 3 doses respectively (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2016). In Kitgum General Hospital, the number of pregnant women who received the first dose increased from 21% in 2015 to approximately 50% in 2017. The number that completed the second dose increased from 10.9% in 2015 to 35.2% in 2017. Data for the earlier study years was not available.

-

4)

Diagnosis and effective treatment of malaria: ACTs remain the main stay of malaria treatment. Currently the test, track and treat strategy is used where ACTs are only given to patients with confirmed malaria on either microscopy or RDT tests. Artesunate, is the first line therapy for severe malaria in combination with ACTs (Uganda Ministry of Health, 2014). Within the region, from both MIS and UDHS surveys, ACTs were used to treat over 90% of all fevers in children under 5 years. However, quinine, chloroquine and amodiaquine are still used (Ministry of Health Uganda, 2015; Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2016). The UDHS 2016 found that within the region, of the children under 5 years that had a fever, 85.1% sought treatment but only 66.8% had blood drawn for parasitology. However, 90.9% of all children under 5 years with a fever were treated with ACTs (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2016).

4. Discussion

An upsurge of malaria was observed in Kitgum and the surrounding districts of Northern Uganda in the years 2015 and 2016. These areas typically experience high intensities of malaria transmission. This study aimed to describe trends in the burden of malaria in relation to recent interventions and changes in climatic factors. The study suggests that the malaria epidemic in 2015/16 was precipitated by the interruption of IRS in 2014. Independent studies within the region where IRS was also interrupted report the similar findings (Okullo et al., 2017; Raouf et al., 2017). Importantly, the work recommends that regardless of short-term success, effective malaria control efforts may require sustained implementation to achieve elimination. Furthermore, IRS can be effectively applied in response to any future malaria epidemic to successfully drive down the malaria burden averting malaria morbidity and mortality.

The malaria burden at the peak of the epidemic greatly exceeded the pre-intervention numbers. This increase could be explained in part by 1) a loss of immunity: It is possible that with several years of malaria control resulting in decreased exposure, individuals could have partially lost or not acquired adequate levels of immunity to malaria (Cook et al., 2010; Diop et al., 2014; Fowkes et al., 2016; Marsh and Kinyanjui, 2006; Bouchaud et al., 2005). This may have increased their risk of clinical disease with renewed transmission. However, evidence is lacking from such a high malaria transmission setting indicating whether 4–5 years of intense malaria control is sufficient to cause loss of immunity. 2) Improved malaria diagnosis: The use of malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) has substantially increased in recent years. RDTs improve the speed, ease, accuracy and cost of malaria diagnosis and treatment compared to microscopy (Boyce et al., 2015). Improved diagnosis may account for some increase in the numbers observed. In recent years, Uganda embraced the test, track and treat strategy for malaria management. Here, all fevers are tested through microscopy or RDT improving the accuracy of disease management (Uganda Ministry of Health, 2014). Lastly, we are not aware of any major social upheavals such as sudden refugee influx or regional instability that could account for the increase in hospital attendance in this time period.

IRS in Kitgum was halted in 2014 on the premise that malaria control had been successful. Success was considered as there was a 45% reduction in the risk of parasitemia and a 32% reduction in the risk of anaemia among children under 5 years of age, a low malaria test positivity rate, and a greater than 50% decline in the number of malaria cases per 1000 population in the districts receiving IRS compared to those not receiving IRS (Steinhardt et al., 2013; USAID, 2015). It is worth noting that during the period when IRS was halted there was also a decline in the use of other malaria control interventions. For example, by 2016, there was a reduction in the universal coverage of LLINS from 92% in 2014 to as low as 41.2% in 2016, far below the national target of 85% by 2017. Furthermore, only 67.85% of children under the age of five slept under the LLIN the night prior to the 2016 health indicator survey, a proportion that is similarly below the national target(Uganda Ministry of Health, 2014). In pregnant women, LLIN coverage dropped from about 79.9% in 2015 to approximately 68.2% in 2016. Thus, although other studies attributed the epidemic primarily to cessation of IRS (Okullo et al., 2017; Raouf et al., 2017), our study suggests that in addition to the cessation of IRS, the epidemic could have resulted from an overall decrease in all malaria control interventions. Despite this observation however, it is important to note that halting IRS was followed by an increase of the malaria incidence to epidemic proportions within 6–7 months. Another study of children younger than 5 years from ten districts in the region reported an identical finding (Okullo et al., 2017). Similar reports were got from Apac district (200 km south of Kitgum) (Raouf et al., 2017). Halting IRS therefore maybe a significant risk factor for malaria epidemics in high transmission settings.

The malaria epidemic posed a huge burden on the health system and significantly increased morbidity especially in children under 5 years of age. Kitgum General Hospital reported a 2-fold increase in malaria hospitalisations. The increase in total hospitalizations could also be attributed to the ‘malaria dividend’ theory (Marsh, 2016) where an increase or decrease in malaria has a similar effect on other conditions such as bacteraemia (Church and Maitland, 2014). Thus, a break down in malaria control may have far reaching implications for health systems. Interestingly, the rise in morbidity did not significantly alter mortality. This may be as a consequence of effective diagnosis and case management with appropriate antimalarial drugs, as incorporated in the test, treat and track policy and the integrated community case management (ICCM) program (Kitutu et al., 2017; Uganda Ministry of Health, 2014).

Multiple studies have shown an association between climatic changes and the burden of malaria (Hay et al., 2002; Lindblade et al., 1999; Woube, 1997). Hence, it was postulated that these changes could be used as predictors of malaria epidemics (Darkoh et al., 2017; Teklehaimanot et al., 2004; Woube, 1997). Climatic changes affect malaria transmission dynamics by modulating mosquito behaviour and distribution (Alemu et al., 2011; Martens et al., 1995; Upadhyayula et al., 2015). Notably, there were no unusual climatic variations in Kitgum district over the study period. Therefore, it is unlikely that the 2015/16 epidemic in Kitgum was caused by a climatic event. The region experiences two main seasons; a short dry and a rather long rainy season (lasting about 7–8 months in the year). In Kitgum, malaria transmission occurs relatively all year-round peaking following the onset of the rainy season around March/April.

There are a number of limitations. First, data collection was conducted at only one site, Kitgum General Hospital. Whilst additional sites would have provided more data for the purposes of comparison, KGH is the only public hospital serving this district which has high levels of poverty. As such, trends from KGH are likely to be representative of malaria trends within the district. Second, this was a retrospective study with data collected from hospital records which may have been imperfect. Third, this study does not present the entirety of the burden in the district, as several cases may have been managed at home, by village health workers or in lower health centres including St. Joseph’s hospital (a private for profit hospital in the district). Finally, several cases and deaths, especially within the community, also remain unreported.

In line with WHO recommendations for scaling back malaria control interventions, our study suggests that in high transmission settings, longer and more sustained efforts may need to be maintained even after achieving control in the short term. Control measures should ideally be scaled back following detailed analyses of malaria indicators, disease surveillance structures, the capacity for case management and vector control (WHO Global Malaria Programme, 2015). It remains possible that the currently available interventions on their own will not achieve eradication (Benelli and Beier, 2017; Cohen et al., 2012; Cui et al., 2015). New cost-effective and long-lasting control interventions may be necessary. These alternatives include deployment of an effective vaccine, reactive case detection and possibly mass drug administration. However, how such alternative strategies would be employed remains unclear and requires further research (Benelli and Beier, 2017; Benelli and Duggan, 2018). It is also necessary to evaluate the minimum level of control interventions that should be maintained in high transmission settings to fortify malaria control gains. It will also be vital to sustain global funding for malaria control and research, in addition to strengthening national control programs to enable effective disease and entomological surveillance. Together, these measures will minimise the risk of malaria resurgence that threatens the vision of a malaria free generation.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to: Kitgum general hospital laboratory and records departmental staff for their generous support; Ocen Patrick the Vector control officer, Kitgum,

Financial support

This work was supported by MRC/DFID African Research Leader Award to Richard Idro jointly funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement (MR/M025489/1). The award is also part of the EDCTP2 program supported by the European Union. F.O. is also supported by an MRC/DFID African Research Leader Award jointly funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement (MR/L00450X/1); an EDCTP Senior Fellowship (TMA 2015 SF - 1001); and a Sofja Kovalevskaja Award from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (3.2 - 1184811 - KEN - SKP). Funding agencies had no part in the design of the study or decision to submit the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Abeku TA, Helinski MEH, Kirby MJ, Ssekitooleko J, Bass C, Kyomuhangi I, Okia M, Magumba G, Meek SR. Insecticide resistance patterns in Uganda and the effect of indoor residual spraying with bendiocarb on kdr L1014S frequencies in Anopheles gambiae s.s. Malar J. 2017;16:156. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1799-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemu A, Abebe G, Tsegaye W, Golassa L. Climatic variables and malaria transmission dynamics in Jimma town, South West Ethiopia. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:30. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso PL, Brown G, Arevalo-Herrera M, Binka F, Chitnis C, Collins F, Doumbo OK, Greenwood B, Hall BF, Levine MM, Mendis K, et al. A research agenda to underpin malaria eradication. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benelli G, Beier JC. Current vector control challenges in the fight against malaria. Acta Trop. 2017;174:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benelli G, Duggan MF. Management of arthropod vector data – social and ecological dynamics facing the one Health perspective. Acta Trop. 2018;182:80–91. doi: 10.1016/J.ACTATROPICA.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchaud O, Cot M, Kony S, Durand R, Schiemann R, Ralaimazava P, Coulaud J-P, Le Bras J, Deloron P. Do African immigrants living in France have long-term malarial immunity? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce RM, Muiru A, Reyes R, Ntaro M, Mulogo E, Matte M, Siedner MJ. Impact of rapid diagnostic tests for the diagnosis and treatment of malaria at a peripheral health facility in Western Uganda: an interrupted time series analysis. Malar J. 2015;14:203. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0725-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church J, Maitland K. Invasive bacterial co-infection in African children with Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2014;12:31. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JM, Smith DL, Cotter C, Ward A, Yamey G, Sabot OJ, Moonen B. Malaria resurgence: a systematic review and assessment of its causes. Malar J. 2012;11:122. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J, Reid H, Iavro J, Kuwahata M, Taleo G, Clements A, McCarthy J, Vallely A, Drakeley C. Using serological measures to monitor changes in malaria transmission in Vanuatu. Malar J. 2010;9:169. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Mharakurwa S, Ndiaye D, Rathod PK, Rosenthal PJ. Antimalarial drug resistance: literature review and activities and findings of the ICEMR network. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:57–68. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkoh EL, Larbi JA, Lawer EA. A weather-based prediction model of malaria prevalence in Amenfi West District, Ghana. Malar Res Treat. 2017;2017:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2017/7820454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diop F, Richard V, Diouf B, Sokhna C, Diagne N, Trape J-F, Faye MM, Tall A, Diop G, Balde AT. Dramatic declines in seropositivity as determined with crude extracts of Plasmodium falciparum schizonts between 2000 and 2010 in Dielmo and Ndiop, Senegal. Malar J. 2014;13:83. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowkes FJI, Boeuf P, Beeson JG. Immunity to malaria in an era of declining malaria transmission. Parasitology. 2016;143:139–153. doi: 10.1017/S0031182015001249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay SI, Cox J, Rogers DJ, Randolph SE, Stern DI, Shanks GD, Myers MF, Snow RW. Climate change and the resurgence of malaria in the East African highlands. Nature. 2002;415:905–909. doi: 10.1038/415905a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemingway J, Shretta R, Wells TNC, Bell D, Djimdé AA, Achee N, Qi G. Tools and strategies for malaria control and elimination: what do we need to achieve a grand convergence in Malaria? PLoS Biol. 2016;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamya MR, Arinaitwe E, Wanzira H, Katureebe A, Barusya C, Kigozi SP, Kilama M, Tatem AJ, Rosenthal PJ, Drakeley C, Lindsay SW, Staedke SG, et al. Malaria transmission, infection, and disease at three sites with varied transmission intensity in Uganda: implications for malaria control. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:903–912. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katureebe A, Zinszer K, Arinaitwe E, Rek J, Kakande E, Charland K, Kigozi R, Kilama M, Nankabirwa J, Yeka A, Mawejje H, et al. Measures of malaria burden after long-lasting insecticidal net distribution and indoor residual spraying at three sites in Uganda: a prospective observational study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitutu FE, Kalyango JN, Mayora C, Selling KE, Peterson S, Wamani H. Integrated community case management by drug sellers influences appropriate treatment of paediatric febrile illness in South Western Uganda: a quasi-experimental study. Malar J. 2017;16:425. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2072-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblade KA, Walker ED, Onapa AW, Katungu J, Wilson ML. Highland malaria in Uganda: prospective analysis of an epidemic associated with El Nino. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:480–487. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(99)90344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACDONALD G. Epidemiological basis of malaria control. Bull World Health Organ. 1956;15:613–626. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaria outbreak in northern Uganda - InterHealth Worldwide [WWW Document] [Accessed 3.2.17];2016 URL https://www.interhealthworldwide.org/home/health-resources/health-alerts/2016/february/05/malaria-outbreak-in-northern-uganda/

- malERA Consultative Group on Drugs. A research agenda for malaria eradication: drugs. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh K. Africa in transition: the case of malaria. Int Health. 2016;8:155–156. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihw022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh K, Kinyanjui S. Immune effector mechanisms in malaria. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens WJM, Niessen LW, Rotmans J, Jetten TH, McMichael AJ. Potential impact of global climate change on malaria risk. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103:458. doi: 10.2307/3432584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mass Distribution of Long Lasting Insecticidal Nets for Universal Coverage in Uganda Evaluation Report

- Ministry of Health Uganda. Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS) 2014-2015. 2015:144. [Google Scholar]

- MOH. Annual Health Sector Performance Report 2014/2015. Kampala, Uganda: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nkumama IN, O’Meara WP, Osier FHA. Changes in malaria epidemiology in Africa and new challenges for elimination. Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oguttu DW, Matovu JKB, Okumu DC, Ario AR, Okullo AE, Opigo J, Nankabirwa V. Rapid reduction of malaria following introduction of vector control interventions in Tororo District, Uganda: a descriptive study. Malar J. 2017;16(227) doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1871-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okia M, Hoel DF, Kirunda J, Rwakimari JB, Mpeka B, Ambayo D, Price A, Oguttu DW, Okui AP, Govere J. Insecticide resistance status of the malaria mosquitoes: anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus in eastern and northern Uganda. Malar J. 2018;17(157) doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2293-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okullo AE, Matovu JKB, Ario AR, Opigo J, Wanzira H, Oguttu DW, Kalyango JN. Malaria incidence among children less than 5 years during and after cessation of indoor residual spraying in Northern Uganda. Malar J. 2017;16:319. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1966-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny MA, Maire N, Studer A, Schapira A, Smith TA. What should vaccine developers ask? Simulation of the effectiveness of malaria vaccines. PLoS One. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raouf S, Mpimbaza A, Kigozi R, Sserwanga A, Rubahika D, Katamba H, Lindsay SW, Kapella BK, Belay KA, Kamya MR, Staedke SG, Dorsey G. Resurgence of malaria following discontinuation of indoor residual spraying of insecticide in an area of Uganda with previously high-transmission intensity. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:453–460. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DL, Cohen JM, Chiyaka C, Johnston G, Gething PW, Gosling R, Buckee CO, Laxminarayan R, Hay SI, Tatem AJ. A sticky situation: the unexpected stability of malaria elimination. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2013;368 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0145. 20120145–20120145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Gueye C, Newby G, Tulloch J, Slutsker L, Tanner M, Gosling RD. The central role of national programme management for the achievement of malaria elimination: a cross case-study analysis of nine malaria programmes. Malar J. 2016;15:488. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1518-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt LC, Yeka A, Nasr S, Wiegand RE, Rubahika D, Sserwanga A, Wanzira H, Lavoy G, Kamya M, Dorsey G, Filler S. The effect of indoor residual spraying on malaria and anemia in a high-transmission area of Northern Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:855–861. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talisuna AO, Noor AM, Okui AP, Snow RW. The past, present and future use of epidemiological intelligence to plan malaria vector control and parasite prevention in Uganda. Malar J. 2015;14(158) doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0677-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teklehaimanot HD, Schwartz J, Teklehaimanot A, Lipsitch M. Weather-based prediction of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in epidemic-prone regions of Ethiopia II. Weather-based prediction systems perform comparably to early detection systems in identifying times for interventions. Malar J. 2004;3(44) doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-3-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tukei BB, Beke A, Lamadrid-Figueroa H. Assessing the effect of indoor residual spraying (IRS) on malaria morbidity in Northern Uganda: a before and after study. Malar J. 2017;16(4) doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1652-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UBOS. 2014 Census Population Uganda Natl Popul Hous Census Resulte. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey. 2016;2016:1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Ministry of Health. The Uganda Malaria Reduction Strategic Plan 2014–2020. 2014:1–83. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyayula SM, Mutheneni SR, Chenna S, Parasaram V, Kadiri MR. Climate drivers on malaria transmission in Arunachal Pradesh, India. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USAID. Malaria Operational Plan (MOP) for Uganda - 2/20/07. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- USAID. PRESIDENT ' S MALARIA INITIATIVE Uganda Malaria Operational Plan FY 2015. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- USAID. PRESIDENT’ S MALARIA INITIATIVE Tanzania Malaria Operational Plan FY 2016. President’s Malaria Initiative. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Smith JD, Kappe SHI. Advances and challenges in malaria vaccine development. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2010;11:1–26. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001318.Advances. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Global Malaria Programme. Risks Associated With Scale-back of Vector Control After Malaria Transmission Has Been Reduced. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO) Prevention and Control of Malaria Epidemics Tutor’s Guide World Health Organization HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Roll Back Malaria Table of Contents. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO) World malaria report 2016 Fact Sheet World Malar Rep. 2016:150. [Google Scholar]

- Woube M. Geographical distribution and dramatic increases in incidences of malaria: consequences of the resettlement scheme in Gambela, SW Ethiopia. Indian J Malariol. 1997;34:140–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeka A, Gasasira A, Mpimbaza A, Achan J, Nankabirwa J, Nsobya S, Staedke SG, Donnelly MJ, Wabwire-Mangen F, Talisuna A, Dorsey G, et al. Malaria in Uganda: challenges to control on the long road to elimination. I. Epidemiology and current control efforts. Acta Trop. 2012;121:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]