Abstract

Efficient and safe delivery of siRNA in vivo is the biggest roadblock to clinical translation of RNA interference (RNAi) based therapeutics. To date, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have shown efficient delivery of siRNA to the liver; however, delivery to other organs, especially hematopoietic tissues still remains a challenge. We developed DLin-MC3-DMA lipid-based LNP-siRNA formulations for systemic delivery against a driver oncogene to target human chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells in vivo. A microfluidic mixing technology was used to obtain reproducible ionizable cationic LNPs loaded with siRNA molecules targeting the BCR-ABL fusion oncogene found in CML. We show a highly efficient and non-toxic delivery of siRNA in vitro and in vivo with nearly 100% uptake of LNP-siRNA formulations in bone marrow of a leukemic model. By targeting the BCR-ABL fusion oncogene, we show a reduction of leukemic burden in our myeloid leukemia mouse model and demonstrate reduced disease burden in mice treated with LNP-BCR-ABL siRNA as compared to LNP-CTRL siRNA. Our study provides proof-of-principle that fusion oncogene specific RNAi therapeutics can be exploited against leukemic cells and promise novel treatment options for leukemia patients.

Keywords: lipid nanoparticle, CML, siRNA, in vivo, Lipid nanoparticle (LNP), BCR-ABL, RNAi, Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)

Introduction

Heterogeneity between leukemia patients and even among leukemic cells causes a lack of specificity in the current treatment regimens (chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation), which are often associated with long term side effects [1, 2]. Hence, there is a need to develop novel therapeutics for all leukemia patients targeting the disease by its molecular fingerprint. Discovery of RNAi has opened new doors for the treatment of various diseases including cancer. Examples of successful RNAi translation include efficient knockdown (86.8%) of hepatic transthyretin in patients with transthyretin amyloidosis [3] and suppression of cholesterol levels in a phase I clinical trial via a single dose of inclisiran (RNAi agent against PCSK9 gene) [4]. Patisiran, a FDA approved RNAi therapeutic has been shown to effectively halt or reverse the progression of the cardiac manifestations of hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis in phase III trials [5]. However, current efforts aim to improve the delivery system for siRNAs beyond the liver, by using nanotechnology [6].

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) represent one of the most advanced systems for RNAi delivery in vivo [7, 8]. These LNPs mixed with surface active compounds like polyethylene glycol (PEG) promote the self-assembly of all components for siRNA encapsulation, enter the cell through endocytosis, and enable siRNAs to escape the endosomal compartment. The low pH in the endosome and lysosome supports the disassembly of the LNPs, the release of the siRNA payload to the cytoplasm and finally the knockdown of the target mRNA [9–12]. A novel microfluidics technology allows highly reproducible packaging of siRNAs in LNPs [8, 13], and parallelization enables upscaling for the clinical setting.

One major roadblock in the translation of RNAi therapeutics is the upscaling to the clinical setting, which requires initial proof of principle studies to validate efficacy and safety of RNAi nano-therapeutics in a clinically relevant disease model. Chromosomal translocations are considered driver mutations in leukemogenesis, and are usually present in all leukemic cells and are retained during relapse. We hypothesized that fusion oncogenes frequently occurring in hematopoietic malignancies would be safe and effective therapeutic targets for siRNA application in leukemic cells [14, 15].

The chimeric fusion oncogene BCR-ABL is a leukemia specific fusion transcript that occurs in all patients with CML, 25% with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [16], and approximately 1% with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [17, 18]. Both ALL and advanced CML patients frequently develop drug resistance after initial response from current therapeutic strategies [19, 20]. Therefore, despite the marked success in CML treatment, concerns regarding the occurrence of resistant and residual disease in subsets of patients demands new approaches to target BCR-ABL [19, 21, 22]. The applicability of RNAi for degradation of the BCR-ABL transcript and sensitization towards inhibitor treatment has been well documented in in vitro studies [23, 24]. In 2007, Koldehoff et. al. first reported inhibition of BCR-ABL oncogene via synthetic BCR-ABL siRNA non-viral delivery in a chemotherapy resistant CML patient [25]. Since then, many other delivery systems including shRNA viral vectors have been applied for the knockdown of BCR-ABL and other fusion oncogenes [8, 26–29].

We utilized microfluidic mixing technology to package BCR-ABL siRNA molecules in LNPs for targeting BCR-ABL fusion oncogene in vitro and in vivo. We show a highly efficient and non-toxic delivery of siRNA in vitro and in vivo with nearly 100% uptake of LNP-siRNA formulations in bone marrow of leukemic model. By testing and validating the safety and functional efficacy of LNP mediated siRNA delivery in a CML model in vitro and in vivo, the present work provides proof-of-concept of the efficacy of therapeutic RNAi in human leukemia in vivo.

Materials and Methods

More details on materials and methods can be found in the supplemental information.

Cell culture

Human leukemic BCR-ABL positive K562 cells were maintained in RPMI medium (GE-Healthcare, Austria, Germany) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, in a humidified incubator at 37°C, adjusted to 5% CO2. K562 cells were sorted after transduction with a lentiviral construct expressing luciferase and GFP proteins in the pGL3-Basic vector (K562L.GFP cells).

LNP-siRNA formulation

The LNP-siRNA was formulated using a proprietary mixture of lipids containing an ionizable cationic lipid, supplied as SUB9KITS™, and the siRNA was encapsulated using a microfluidic system for controlled mixing conditions on the NanoAssemblr™ instrument (Precision Nanosystems, Vancouver, Canada) [12]. Concentrations in our manuscript always refer to siRNA (1μg/ml signifies 1μg of siRNA in 1ml of culture and 5mg/kg signifies 5mg of siRNA per kg of body weight) (0.25, 0.5, 1 and 2 μg/ml siRNA, corresponding to 17.85, 35.7, 71.43, and 143 nM siRNA, respectively). Further details about composition and properties of formulations are provided in supplementary methods.

Flow cytometry

Cells treated with the LNP-siRNA formulation were harvested following 24 hours of treatment and washed twice with PBS. Delivery of LNP-siRNA formulations was monitored by flow cytometry by detecting the DiI signal by the blue/green laser of the BD-LSR II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). GFP signal in K562L.GFP cells were used to detect transplanted human leukemia cells. CD34 (8G12) APC (345804) antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences (Heidelberg, Germany).

Xenograft models

6-8 weeks old female NOD/SCID mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany). NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wj1/SzJ / (NOD/SCID-IL-2Rg-null/ NSG) mice were bred by the central animal laboratory of Hannover Medical School and kept in pathogen-free conditions. All animal experiments were approved by the local authority and the institutional ethics committee. 2x106 K562 cells transduced with CTRL or anti-BCR-ABL shRNA were sorted and then inoculated subcutaneously in both flanks of NOD/SCID mice. Tumor volumes were measured at the indicated time points using a vernier caliper. K562L.GFP cells were re-suspended in sterile PBS (30 μl) and injected intrafemorally into the femur (1×105cells/injection) of female NSG mice. LNP-siRNA formulations were dosed at 5 mg/kg via intra-peritoneal injection. Mice were injected either intravenously or intraperitoneally with CTRL or LNP-AHA1 siRNA or LNP-BCR-ABL siRNA. The loading dose consisted of 3 injections of 5 mg/kg LNP-siRNA formulation (0, 8 and 24 hours). Additional injections were given as indicated in the results section.

Apoptosis measurement

For apoptosis measurement 1x105 cells were stained with Annexin V-APC according to the manufacturers protocol (BD Pharmingen Cat no. 550474) and analyzed on a BD-LSR II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany).

Cell viability assay

Equal cell numbers were seeded in 100 μl of medium in each well of a 96-well flat bottom transparent plate. 1/10th volume of the alamarBlue® reagent (Abd Serotec, Raleigh, NC) was directly added to the wells and incubated for 1 to 4 hours at 37°C in a cell culture incubator, protected from direct light. Results were recorded by measuring fluorescence using a fluorescence excitation wavelength of peak excitation 570 nm and peak emission 585 nm on a microplate reader (Safire; Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Immunoblotting

Cellular lysates were prepared and immunoblotting was performed as described previously [30]. Antibodies and methods are described in the Supplemental methods.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR analysis

RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed as previously described [31]. Further details are provided in supplemental methods.

Patients and primary cells

Primary leukemia cells from bone marrow and peripheral blood of patients with CML were cultured as mentioned in supplemental methods. Written informed consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the institutional review board of Hannover Medical School (ethical vote 2504-2014).

Statistical analysis

Pairwise comparisons were performed by Student t test for continuous variables. The 2-sided level of significance was set at P < .05. Comparison of survival curves were performed using the log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Munich, Germany), and GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

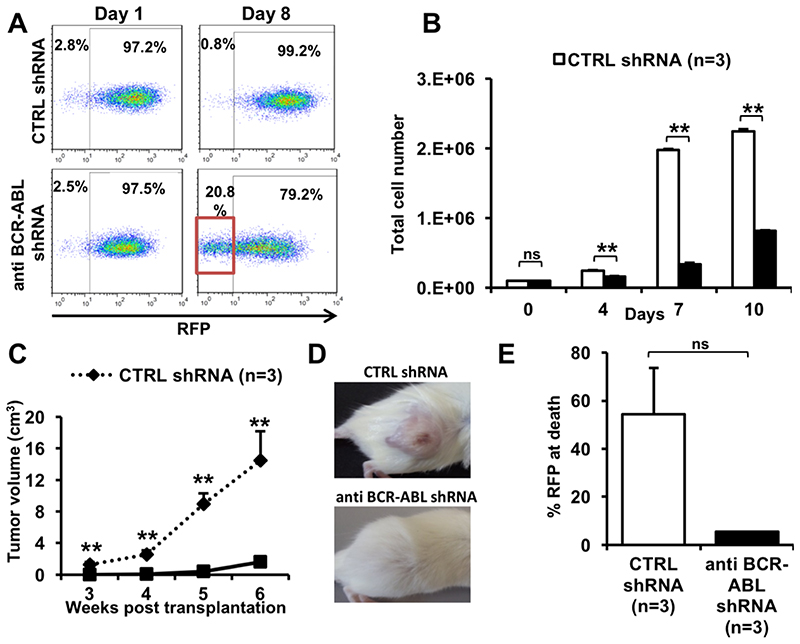

Validation of a BCR-ABL dependent monogenic xenotransplantation CML model

We established and validated a BCR-ABL dependent traceable K562 xenogenic leukemia model to study the properties of LNP-siRNA formulations in vivo. First, we wanted to confirm the dependency of K562 cells for the BCR-ABL fusion oncogene in vitro and in vivo by using short hairpin (sh) RNA based RNAi. K562 cells were transduced with a RFP (red fluorescent protein) vector expressing either a control shRNA (CTRL shRNA) or an anti-BCR-ABL shRNA (day 0). Knockdown of BCR-ABL induced a competitive disadvantage for RFP-positive cells as the proportion of RFP-negative cells increased in cells transduced with anti BCR-ABL shRNA as compared to CTRL shRNA transduced cells from day 1 to day 8 (Figure 1A). Also, anti-BCR-ABL shRNA transduced cells proliferated significantly slower than CTRL shRNA transduced cells from day 4 onwards (Figure 1B). Further, we transplanted these K562 cells transduced with CTRL or anti BCR-ABL shRNA subcutaneously in NOD-SCID mice. Mice transplanted with cells expressing anti BCR-ABL shRNA showed significantly reduced tumor volumes at all time points as compared to CTRL shRNA (Figure 1C and 1D). At death, tumors were excised from mice and the mixed tumor cell population was analyzed by flow-cytometry. The fraction of RFP-CTRL shRNA positive cells in control tumors were higher than in tumors transduced with anti-BCR-ABL shRNA, suggesting that contaminating non-transduced cells outgrew anti-BCR-ABL transduced cells (Figure 1E). Collectively, the reduction of BCR-ABL expression through BCR-ABL shRNA resulted in substantial growth inhibition in vitro and in vivo. These data demonstrate the feasibility of this BCR-ABL-dependent xenotransplant model as a single hit leukemia that can be further used to evaluate the targeted and functional efficacy of LNP mediated siRNA delivery.

Figure 1. Establishment of a BCR-ABL dependent monogenic xenotransplantation CML model.

A. Percentage of RFP positive cells measured by flow cytometry in K562 cells transduced with CTRL (RFP) or anti-BCR-ABL shRNA (RFP) and sorted for RFP positive cells at day 0 (representative FACS plot).

B. Number of viable, sorted, RFP positive K562 cells over time which were transduced with CTRL or anti-BCR-ABL-shRNA (initial cell count 100,000 cells per ml, mean ± SEM, n=3).

C. Tumor volume of K562 cells transduced with CTRL or anti-BCR-ABL shRNA inoculated subcutaneously in both flanks of NOD/SCID mice, measured at the indicated time points after inoculation (mean ± SEM, n=4).

D. Representative picture of subcutaneous tumors in NOD/SCID mice inoculated with K562 cells transduced with CTRL or anti-BCR-ABL shRNA.

E. Percentage of RFP positive cells in isolated subcutaneous tumors from NOD/SCID mice inoculated with K562 cells transduced with CTRL or anti-BCR-ABL shRNA, measured at 38 days after inoculation in sacrificed mice by flow cytometry (mean ± SEM, n = 3). As we analyzed all cells in the tumor the proportion of human leukemia cells is approximately 55% in the CTRL group, while the remaining cells are infiltrating stroma cells of mouse origin.

** indicates P<.01, ns, not significant.

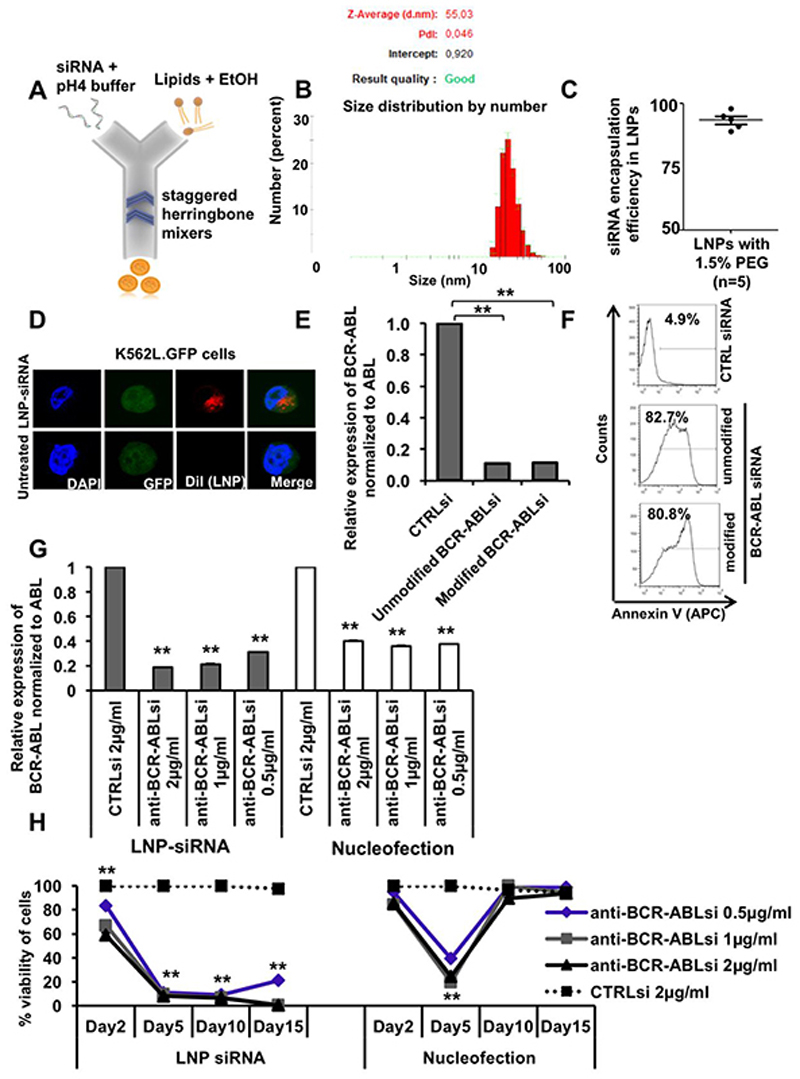

Formulation and characterization of lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-siRNA as an advanced delivery tool

To investigate the uptake, distribution and silencing activity of CTRL and anti-BCR-ABL siRNA in vitro and in vivo, siRNAs were formulated in ionizable cationic LNPs using the NanoAssemblr™ (Figure 2A). Ionizable cationic LNPs have pKa values below 7 that allow siRNA encapsulation at lower pH and a relatively neutral surface at physiological pH. LNPs were analyzed for size and charge characteristics with the zetasizer instrument. The estimated mean diameter of the 1.5% PEG-DMG LNP-siRNA formulations (with final lipid/siRNA weight ratio 10:1) was 55 nm (Figure 2B) [32]. All the siRNAs used in this study had an encapsulation efficiency of more than 90%, suggesting that more than 90% of the packaged siRNA is actually present inside the lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) (Figure 2C). The intracellular localization of DiI labeled LNPs was visualized as red dots due to the presence of DiI in the perinuclear and cytoplasmic endosomal space through confocal imaging after 24 hours of treatment (Figure 2D). As previously reported, chemical modifications can be used to reduce sequence-related off-target effects and increased stability in vivo, while maintaining efficient target-mRNA silencing [33]. We therefore tested 1 unmodified and 2 modified siRNAs for their on-target efficacy by nucleofection in K562 cells. siRNAs were either modified by 2′-O-methyl or 2′-fluoro groups to enhance their stability in vivo (Supplementary Table S1) [33]. We found comparable on-target efficacies between unmodified and modified anti-BCR-ABL siRNAs. We observed 90% knockdown of the BCR-ABL oncogene at mRNA level (Figure 2E) resulting in 80-82% of Annexin V positive cells (Figure 2F) after treatment with unmodified or modified anti-BCR-ABL siRNA as compared to CTRL siRNA. Due to better stability of modified siRNAs in vivo, similar knockdown efficiency and apoptosis, we used the modified form (modification2) of anti-BCR-ABL siRNA for our in vivo experiments.

Figure 2. Formulation and characterization of lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-siRNA as an advanced delivery tool.

A. LNP-siRNA formulation scheme (outline). LNP components dissolved in ethanol were mixed with siRNA dissolved in low pH buffer in a microfluidic chip in the NanoAssemblr instrument.

B. Size distribution analysis of LNP-siRNA formulations produced with 1.5% PEG 2000 DMG (Peaks in the plot shows average diameter distribution, n=3).

C. Encapsulation efficiency of siRNA in LNPs, measured by the Ribogreen assay (n=5).

D. Subcellular distribution of LNP-siRNA (1 μg/ml) in K562L.GFP cells after 24 hours of incubation as shown by confocal imaging.

E. RT-PCR validation and comparison of BCR-ABL knockdown in K562L.GFP cells at 72 hours after nucleofection of 300nM unmodified and modified anti-BCR-ABL siRNA (mean ± SEM, n=3).

F. Representative FACS plot showing counts of Annexin V positive K562L.GFP cells at 96 hours after nucleofection of 300nM LNP-CTRL siRNA and anti-BCR-ABL siRNA (unmodified and modified/modification2).

G. Comparison of LNP versus nucleofection mediated siRNA delivery based on RT-PCR validation of BCR-ABL knockdown in K562L.GFP cells at 72 hours after siRNA delivery by LNPs (left side, grey bars) and by nucleofection (right side, white bars) (mean ± SEM, n=3).

H. Comparison of LNP versus nucleofection mediated siRNA delivery based on viability of K562L.GFP cells at day 2, 5, 10 and 15 after siRNA delivery (mean ± SEM, n=3).

** indicates P<.01

In order to investigate and compare the advances of our LNP-siRNA formulations over the conventional nucleofection method for siRNA delivery, equal quantities of siRNA were delivered in K562 cells via nucleofection or LNPs. We observed increased Annexin V positive cells (44%) when cells underwent nucleofection as compared to LNP-mediated delivery of CTRL siRNA (Supplementary Figures S2A and S2B). In addition, we observed significantly better knockdown efficiency at mRNA level through LNP mediated siRNA delivery in a dose dependent manner (81%, 79% and 69% for LNP versus 60%, 64% and 63% for nucleofected siRNA at 2, 1 and 0.5μg of siRNA, respectively, Figure 2G). Gene silencing of BCR-ABL by nucelofection only temporarily induced cell death in K562 cells, while LNP-mediated inhibition of BCR-ABL induced long-lasting growth suppression in K562 cells (Figure 2H). These results suggest that LNP-mediated delivery of siRNAs is an efficient and potent method of delivery over conventional methods.

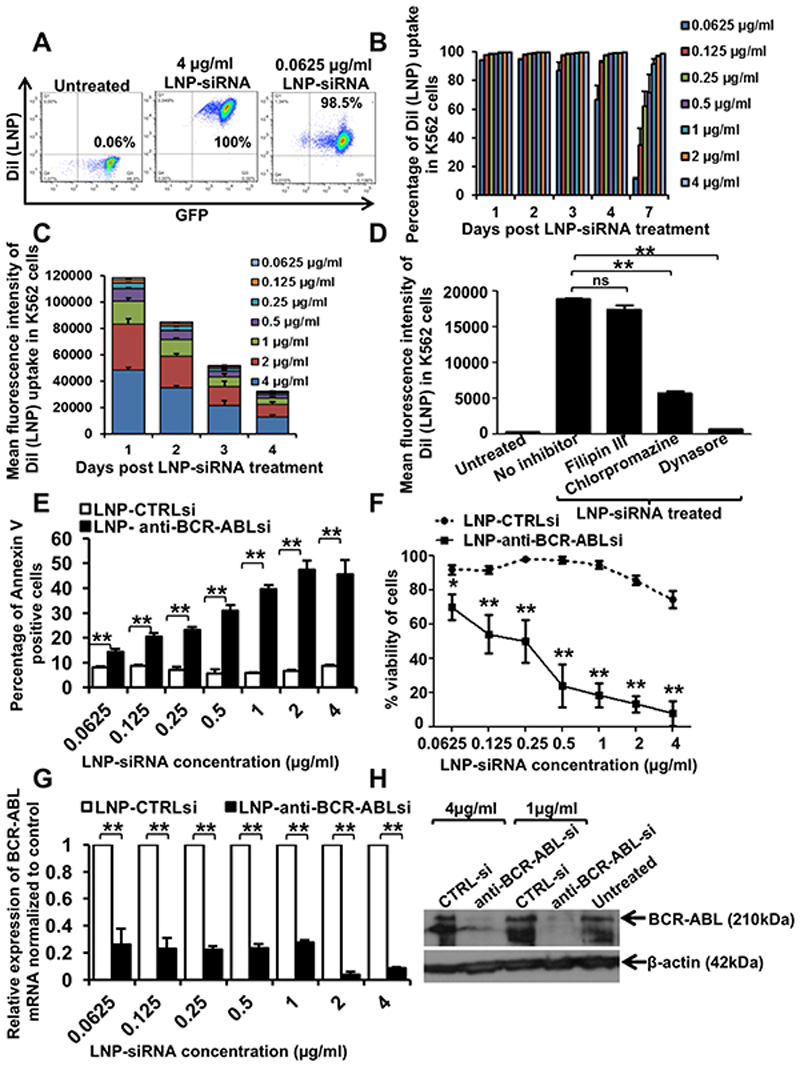

Uptake and on-target efficacy of LNP-siRNA formulations in human leukemia cells in vitro

To determine the delivery efficiency of our LNP-siRNA formulations, we incubated human leukemia K562 cells with siRNA-containing LNPs at various concentrations. The delivery efficiency was determined by FACS, which measured the number of DiI fluorescence positive cells. K562 cells expressing GFP and luciferase (denoted as K562L.GFP) were incubated with CTRL siRNA-containing LNPs at concentrations from 0.0625μg/ml to 4μg/ml under normal culture conditions (RPMI with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin). We found that almost 100% of the cells had taken up siRNA containing LNPs even at the lowest concentration, following 24 hours of incubation (Figure 3A). Until day 4, almost all cells remained positive for DiI fluorescence even at the 0.125 μg/ml concentration. The percentage of LNP-siRNA positive cells incubated at lower concentrations started decreasing following days 4 to 7, whereas all cells with higher concentrations of LNP-siRNA remained positive for DiI fluorescence up to day 7 (Figure 3B). A dose and time dependent decrease in intracellular DiI mean fluorescence intensity was observed as measured by mean fluorescence intensity (Figure 3C and Supplemental Figure S2). To determine which endocytic pathway is responsible for LNP-siRNA uptake into the cells, we treated cells with LNP-siRNA in the presence of different endocytic inhibitors. Fillipin mediated downregulation of Caveolin 1, responsible for caveolin mediated endocytosis, did not modify LNP uptake, whereas treatment with chlorpromazine and especially dynasore, inhibitors of receptor/clathrin mediated endocytosis, reduced the uptake of LNPs significantly (Figure 3D). We next investigated whether LNP mediated siRNA delivery efficiently inhibited the BCR-ABL oncogene in human leukemic cells. To quantify the cells undergoing apoptosis due to inhibition of BCR-ABL, we performed an Annexin V assay with cells incubated with different doses of CTRL siRNA/LNPs and anti-BCR-ABL siRNA/LNPs. We observed a time (24 hours to 96 hours) and dose (0.0625 to 4μg/ml) dependent increase in apoptosis in cells with anti-BCR-ABL siRNA compared to CTRL siRNA starting at 48 hours and being most pronounced at 96 hours (Supplemental Figure S3 and Figure 3E). Cell viability was measured using the alamar blue assay. CTRL siRNA merely inhibited cell viability, while anti-BCR-ABL siRNA treated cells underwent apoptosis in a dose dependent manner (Figure 3F). All the cells treated with anti-BCR-ABL siRNA were dead by day 7 at or above siRNA concentrations of 0.5μg/ml (data not shown). To confirm that cell death was an on-target effect, we measured mRNA and protein levels of BCR-ABL in LNP/siRNA treated cells. Real time PCR analysis showed that BCR-ABL expression levels were reduced up to 90% at higher and 65-70% at lower concentrations of anti-BCR-ABL siRNA compared to CTRL siRNA at 72 hours (Figure 3G). A robust knockdown in BCR-ABL protein was shown by western blot at 96 hours (Figure 3H and S5). These results confirm that the ionizable cationic LNPs are more efficient, convenient and less toxic than conventional methods used to deliver siRNA into human cells and are taken up by receptor/clathrin mediated endocytosis.

Figure 3. Uptake and on-target efficacy of LNP-siRNA formulations in human leukemic cells in vitro.

A. Representative FACS plot showing the percentage of Dil (LNP) positive cells as measured by flow cytometry in K562L.GFP cells treated with LNP CTRL siRNA (4μg/ml and 0.0625 μg/ml) after 24 hours.

B. LNP uptake in all human leukemia cells in vitro over a large concentration range over time. Percentage of Dil (LNP) positive cells as measured by flow cytometry in K562L.GFP cells treated with LNP CTRL siRNA at indicated time points in the figure (mean ± SEM, n=3).

C. Mean fluorescence intensity of DiI (LNP) uptake in human leukemia cells over a large concentration range over time (mean ± SEM, n=3).

D. Mean fluorescence intensity of DiI (LNP uptake) as measured by flow cytometry in K562L.GFP cells at 1 hour, after treatment with LNP siRNA in the presence or absence of inhibitors of endocytosis (mean ± SEM, n=3).

E. Percentage of Annexin V positive K562L.GFP cells after 96 hours of LNP-CTRL or anti-BCR-ABL siRNA treatment at indicated concentrations (mean ± SEM, n=3).

F. Viability of K562L.GFP cells after 96 hours of LNP-CTRL or anti-BCR-ABL siRNA treatment with indicated concentrations as shown in the figure (mean ± SEM, n=3).

G. RT-PCR validation of BCR-ABL knockdown using LNP encapsulated anti-BCR-ABL siRNA as compared to CTRL siRNA in K562L.GFP cells after 72 hours (mean ± SEM, n=3).

H. Western blot showing knockdown of BCR-ABL protein expression in K562L.GFP cells treated with LNP CTRL or anti-BCR-ABL siRNA for 96 hours (representative of n=3).

* indicates P<.05, ** indicates P<.01, ns, not significant.

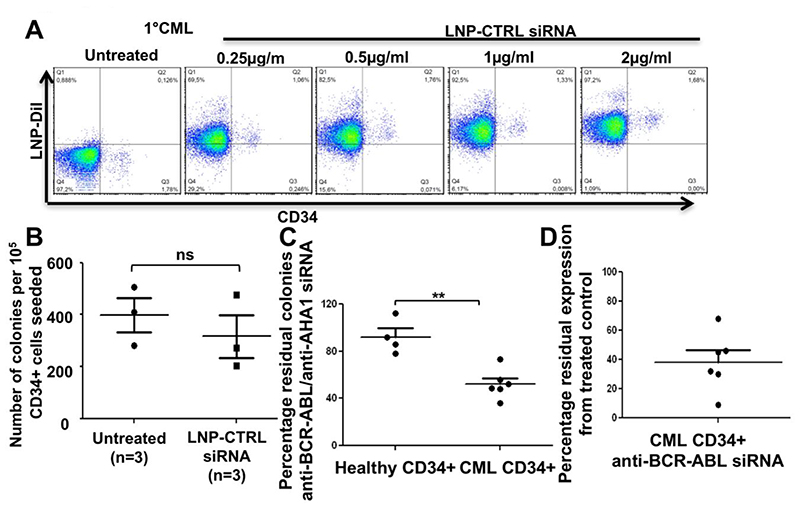

Efficient and safe functional delivery of LNP- BCR-ABL siRNA in CD34+ primary human CML cells

To evaluate the LNP-siRNA uptake in difficult to transfect CD34+ primary human CML cells, we incubated an LNP CTRL-siRNA formulation with freshly isolated primary cells from a CML patient in cytokine supplemented primary human cell culture media. We observed an efficient dose dependent uptake of LNP-CTRL siRNA in the CD34 positive population and with variable efficacy in CD34 negative primary cells from the CML patient at 72 hours after a single treatment (Fig. 4A). Treatment of bone marrow of healthy stem cell donors revealed no toxicity to normal progenitors as assessed by the CFC assay (Figure 4B). These data show that our LNPs are efficiently and safely taken up under normal growth conditions even in difficult to transfect primary leukemic cells, with no significant effect on normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. We next investigated whether LNP mediated siRNA delivery efficiently inhibited the BCR-ABL oncogene in primary human CML cells. We incubated CD34+ primary bone marrow cells from either healthy donors or BCR-ABL positive CML patients with LNP-CTRL (or AHA1) siRNA or LNP-BCR-ABL siRNA (1μg/ml) overnight and seeded equal number of treated cells for CFC assay. We observed a significant reduction in the number of residual colonies in CD34+ primary CML cells treated with LNP-BCR-ABL siRNA compared to healthy control cells (Fig. 4C). The knockdown in BCR-ABL expression in these cells was confirmed via Real Time PCR analysis. Though we observed a significant reduction in BCR-ABL expression, the percentage of reduction was different in different CD34+ primary CML samples (35-90% reduction) (Figure 4D). These results indicate that our LNP-siRNA formulations can effectively target CD34+ primary human CML cells without having any adverse effects on normal healthy CD34+ bone marrow cells.

Figure 4. Efficient uptake and on target efficacy of LNP-siRNA in primary human CD34+ CML cells.

A. Representative FACS plot for uptake of LNP-CTRL siRNA in CD34 negative and CD34 positive CML bone marrow cells at day 3 after a single treatment of different concentrations of LNP-CTRL siRNA in vitro (representative of n=3 CML samples).

B. Colony number from CFC assays with healthy human CD34+ cells either untreated or treated with LNP-CTRL-siRNA (1μg/ml). 100,000 cells were plated in 3 mL semi-solid medium and 1μg/ml LNP-CTRL-siRNA was added to this medium. Colony numbers were counted after 14 days of incubation (mean ± SEM, n=3).

C. Residual colony number from CFC assays with healthy human CD34+ cells or CD34+ CML patient cells cells treated with LNP-siRNA (CTRL or BCR-ABL). 100,000 cells were treated overnight with LNP-CTRL-siRNA or LNP-BCR-ABL-siRNA (1μg/ml each) and plated in 3 mL semi-solid medium. Colony numbers were counted after 14 days of incubation (mean ± SEM, n=4 CD34+ healthy controls and n=6 CD34+ primary CML patient cells).

D. RT-PCR validation of BCR-ABL knockdown in CD34+ primary CML cells treated with LNP-siRNA (CTRL or BCR-ABL). 100,000 cells were treated with LNP-CTRL-siRNA or LNP-BCR-ABL-siRNA (1μg/ml each) for 72 hrs (mean ± SEM, n=6 CD34+ primary CML patient cells).

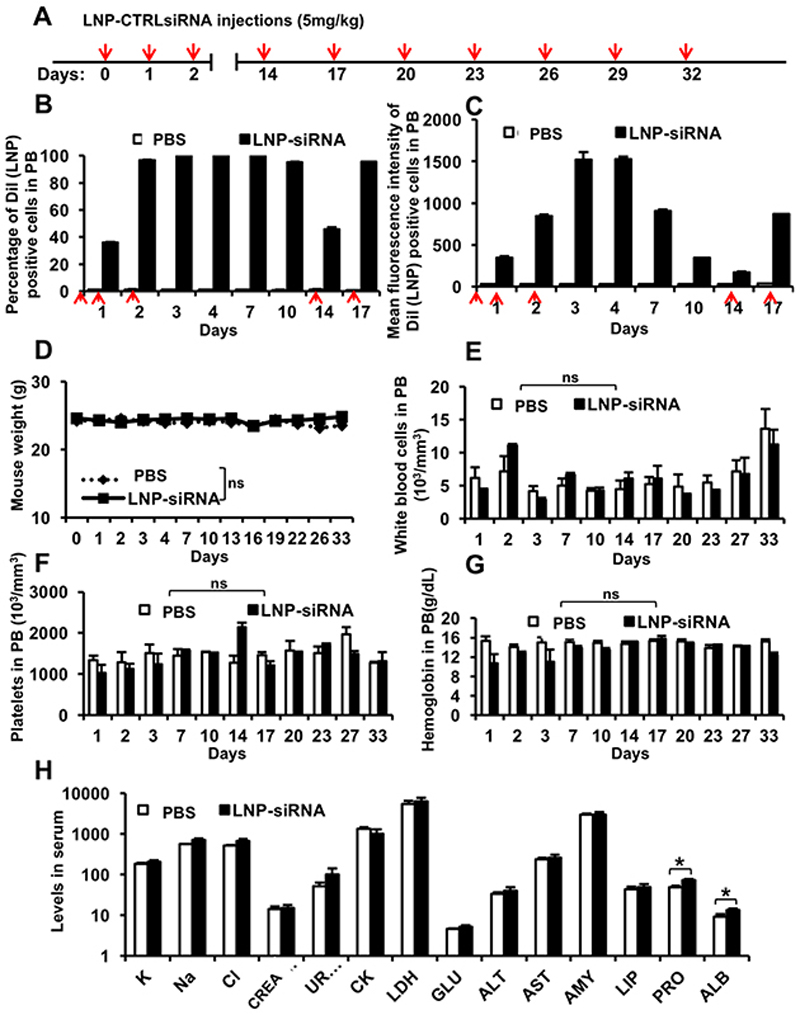

Pharmacokinetics of LNP-siRNA formulations suggests overall good stability and tolerability in mice

Next, we investigated the bio-distribution and half-life of siRNA-containing LNPs and their safety profile in vivo. Healthy NSG mice were injected with a therapeutic dose of 5mg/kg LNP-CTRL siRNA at regular time intervals (see Figure 5A for injection schedule). CTRL or AHA1 is a targeting functional siRNA used as control, as knockdown of AHA1 has no reported phenotype. To first evaluate the uptake efficiency, injected mice were bled at regular time intervals and analyzed for the percentage and fluorescence intensity of DiI positive cells in the PB. We found that a total dose of 10 mg/kg LNP-CTRL siRNA (2 injections) resulted in a 100% uptake in peripheral blood cells, but a total dose of 15 mg/kg (3 injections over 24 hours) resulted in higher fluorescence intensity (Figure 5B and 5C, respectively). Interestingly, LNP-siRNA uptake was very stable in vivo as almost 100% peripheral blood cells were positive until day 10 after administration of the first 3 doses (Figure 5B). Peak fluorescence intensity was maintained through day 4, while DiI fluorescence intensity decreased over time (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Pharmacokinetics of LNP-siRNA formulations suggests overall good stability and tolerability in mice.

A. Injection schedule for i.v injections of LNP-CTRL siRNA in normal NSG mice (red arrow indicates injection).

B. Percentage of Dil (LNP) positive cells as measured by flow cytometry in peripheral blood (PB) of NSG mice following treatment with PBS or LNP-CTRL siRNA at indicated time points. (mean ± SEM, n=3) (Red arrow indicates 5mg/kg LNP CTRL siRNA injection).

C. Mean fluorescent intensity of Dil (LNP) positive cells as measured by flow cytometry in peripheral blood (PB) of NSG mice following treatment with PBS or LNP-CTRL siRNA at indicated time points (mean ± SEM, n=3) (Red arrow indicates 5mg/kg LNP CTRL siRNA injection).

D. Mouse body weight following treatment (as indicated in Figure 5A) with PBS or LNP-CTRL siRNA at indicated time points. (mean ± SEM, n=3)

E. White blood cell count, (F) platelet count and (G) hemoglobin in peripheral blood of NSG mice treated with PBS or LNP-CTRL siRNA at indicated time points. (mean ± SEM, n=3).

H. Serum biochemical profile in LNP-CTRL siRNA and PBS treated control mice after 5 injections (serum was collected at 24 hours following the last injection) (K: potassium (mmol/l);Na: sodium (mmol/l); Cl: chloride (mmol/l);KREA: creatinine (μmol/l); UREA: urea (mmol/l); CK: creatine kinase (U/l);LDH: lactate dehydrogenase (U/l); (GLU: glucose (mmol/l);ALT: alanine aminotransferase (U/l); AST: aspartate aminotransferase (U/l);AMY: amylase (U/l);LIP: lipase (U/l);PRO: protein (g/l); ALB: albumin (g/l). (mean ± SEM, n=3 for PBS treated mice and n=6 for LNP-CTRL siRNA treated mice).

* indicates P<.05, ns, not significant.

Upon multiple injections of LNP-CTRL siRNA (see Figure 5A for injection schedule) no reduction in body weight was observed compared to PBS treated mice, showing that LNP-siRNA is generally well tolerated (Figure 5D). Examination of complete blood counts of the mice revealed that LNP-siRNA treated mice had a comparable number of white blood cells, platelets, and hemoglobin (Figure 5E, 5F and 5G), with similar numbers of lymphocytes, granulocytes and monocytes (data not shown) compared to PBS treated mice. Serum analysis showed no significant toxicity in mice following administration of LNP-siRNA (Figure 5H). Importantly, no liver toxicity was found as there were no significant differences in the levels of liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). Comparable levels of urea and creatinine between LNP-siRNA and PBS treated mice suggested that the kidney function was not affected. Normal levels of amylase and lipase enzymes (AMY, LIP) suggested no signs of pancreatitis associated with systemic toxicity. Amino groups present in cationic amino lipids or dehydration caused due to excess uptake of LNPs can be a reason for significantly higher levels of serum albumin and protein in treated versus control mice. Levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), glucose, sodium, and potassium in serum were similar in treated mice and control mice, suggesting overall good tolerability of the LNP/siRNA formulation in mice.

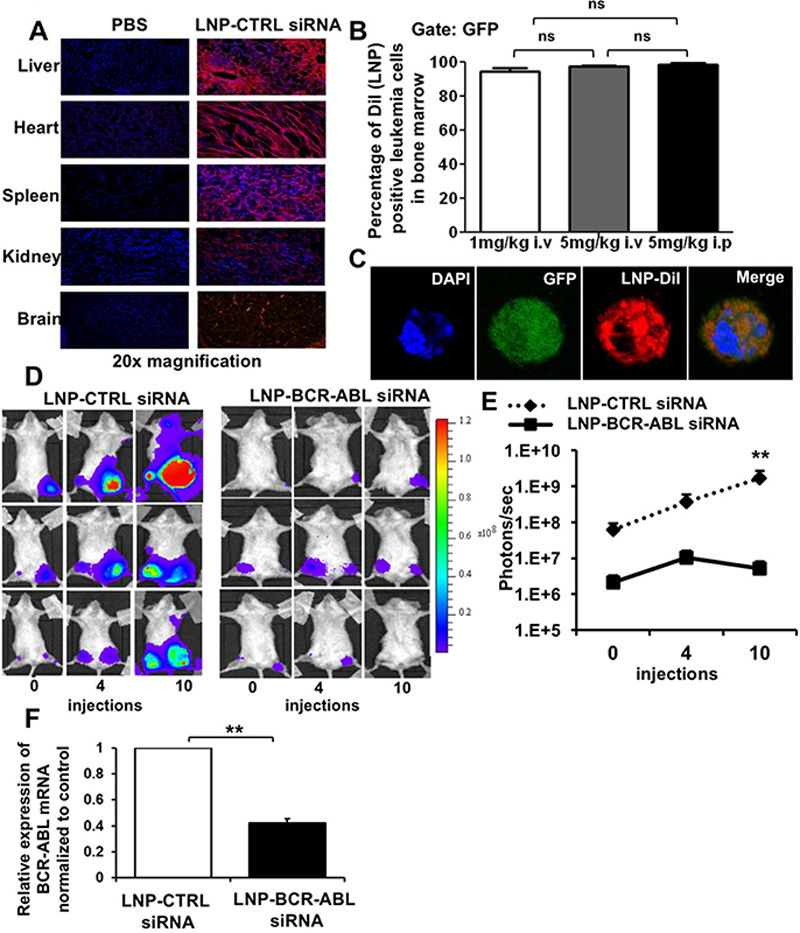

Efficient delivery of LNP-siRNA formulations in hematopoietic tissues in vivo decreases leukemic burden in a CML-xenograft leukemia model

We next assessed the delivery potential of our LNPs in vivo, with a focus on hematopoietic tissues following systemic administration. We used our K562L.GFP xenograft leukemia mouse model, where leukemic cells are injected directly into the femurs of mice. These mice received 3 intravenous injections of LNP-siRNA at 5 mg/kg body weight at 0, 8 and 24 hours and were analyzed at 48 hours. The systemic administration of LNPs resulted in ubiquitous uptake in different tissues, spleen, liver, lung, kidney, heart and also brain, which is hard to reach due to the blood-brain-barrier (Figure 5A). Almost all human leukemic cells in bone marrow had taken up LNPs independent of the dose and route of administration (Figure 5B, 5C Supplemental Figure S4). However, the higher dose of 5 mg/kg induced higher fluorescence intensity in bone marrow cells of treated mice compared to the dose of 1 mg/kg, suggesting a dose-dependent uptake into these cells in vivo (Figure 5C). The leukemia burden in mice was quantified using IVIS imaging to detect the luciferase signal in human leukemic cells present in the bone marrow of transplanted mice before and after treatment with LNPs encapsulating CTRL siRNA or anti-BCR-ABL siRNA. After 10 LNP-siRNA injections over a period of 35 days, we observed a reduction in the luciferase signal by 0.75-fold from 4 injections to 10 injections, while the signal increased in control treated mice by 1.6-fold (Figure 5D and Figure 5E). We observed a 60% knockdown efficiency of BCR-ABL by LNP-anti-BCR-ABL siRNA in sorted leukemia cells from the myelosarcoma tissue of sacrificed mice (Figure 5F). Thus, LNPs efficiently delivered siRNA to human leukemia cells in vivo and reduced leukemic burden in a xenograft leukemia model.

Discussion

As a therapeutic approach, RNAi can overcome major drawbacks of traditional chemotherapy like low tumor specificity, severe side effects, and the inability to inhibit undruggable targets like transcription factors. In this study, we took advantage of the leukemia specificity of fusion oncogenes to selectively target leukemia cells despite an untargeted drug delivery system. We utilized siRNA against the fusion breakpoint of BCR-ABL fusion gene that specifically knock down the fusion gene [23]. Our ionized LNPs were optimized to bypass the liver and distribute to all tissues. This enabled us to target leukemic cells independent of the expression of a potential leukemia specific ligand.

So far, no cellular ligand has been identified that is selectively expressed on leukemic but not on normal stem cells. Ligands like CD123, CD33 or CLL1/CLEC12A are found on leukemic stem cells but are also present to some extent in normal stem cells [34–36]. Peer et al. developed hyaluronan-coated LNPs, which are specifically taken up by adenocarcinoma A549 cells that express higher levels of the hyaluronan receptor CD44 compared to normal cells [37]. Also, effective inhibition of cyclin D1 in a mantle cell lymphoma mouse model using αCD38 antibody-LNPs encapsulating CycD1 siRNA was recently reported [13]. However, such a targeted approach likely decreases the wide delivery of siRNAs to all leukemic cells. Our untargeted approach was highly efficient to deliver LNPs to all human leukemic cells in vivo both in peripheral blood and bone marrow. Thus, the use of a leukemia-specific siRNA enabled us to abstain from a targeted delivery approach.

Our LNPs represent an excellent transfection reagent in vitro that allowed near complete transfection of difficult to transfect primary normal hematopoietic and leukemic cells. It has been shown that the intracellular uptake of our nanoparticles is dependent on the association with ApoE and binding to the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL) [38, 39]. The LDL receptor is widely expressed on leukemic cells [40] and was also expressed in our leukemia cells. As expected, the receptor/clathrin mediated endocytosis of the nanoparticles was confirmed in our study.

Chromosomal translocations are early events, possibly the ones initiating leukemia, usually present in all leukemia cells, and are retained during relapse [41–43]. Our approach of targeting fusion oncogenes can be extended to a large proportion of ALL and AML patients. In all, 75% of pediatric patients harbor gross chromosomal aberrations, with ETV6-RUNX1, TCF3-PBX1, MLL rearrangements and BCR-ABL1 being the most frequent translocations [44]. In adult ALL patients MLL-AF4, TCF3-PBX1 and TEL-AML1 are found in 5, 3 and 2% of patients, respectively, besides BCR-ABL, which is found in approximately 25% of patients and is associated with poor prognosis [45]. In AML patients, recurrent and unique fusion oncogenes are found in 45 percent of patients [46].Thus, LNP-siRNA targeting fusion oncogenes can be developed for a significant proportion of patients. This approach can be highly individualized, and if a different fusion gene appears at relapse, it can be treated with a different siRNA. Treatment response can be easily monitored by a fusion oncogene-specific real-time RT-PCR.

Despite the marked success in CML and ALL treatment by tyrosine kinase inhibitors, some patients develop resistant disease and loose the response to kinase inhibitors [22, 47]. Although we intended the BCR-ABL model as proof-of-principle, LNP-siRNA treatment may become useful in patients with mutations causing resistance against the available kinase inhibitors. Thus, we provide proof-of-concept that primary human leukemia can be targeted with siRNA in vivo and can improve survival.

The interest in antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) or siRNA based therapeutics initially declined due to the failure of phase III trials. LY2275796, an eIF-4E ASO and oblimersen, a BCL2 ASO did not meet the primary endpoint in AML and small cell lung cancer [48, 49]. However, anti-sense oligonucleotides (ASO) and small molecule inhibitors are currently the main therapeutic strategies against aberrant splicing in cancer [50]. Imetelstat, a 13-mer lipid-conjugated oligonucleotide targets the RNA template of human telomerase reverse transcriptase and has recently shown promising activity in myelofibrosis patients [51].

Currently, most efforts around siRNA therapy focus on liver diseases, because most formulations are quickly and largely trapped in the liver. Proof-of-concept of siRNA-mediated knockdown of a disease gene in humans was published in 2013 showing efficient knockdown of transthyretin in thransthyretin amyloidosis patients after a single subcutaneous injection of anti-transthyretin siRNA packaged in LNPs (ALN-TTR02) (average knockdown of transthyretin 86.8%) [3]. Also, phase II clinical trials testing the RNAi dynamic conjugate (DPC) ARC-520 in combination with approved nucleoside analogs (NCT02065336 and NCT02349126) against HBV are ongoing [52].

MicroRNAs have been also delivered in vivo in a number of studies. Transferrin targeted lipopolyplex nanoparticle mediated expression of miR-181a, a negative regulator of the RAS pathway, antagomiR-126, a leukemia stem cell regulator, and miR-29b have been shown to effectively target AML cells [53–55]. Furthermore, targeted and non-targeted dendrimeric nanoparticles carrying miR-22 or miR-150 have been reported to significantly delay AML progression in engineered murine models [56, 57].

In summary, we have developed LNPs that target primary human leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo with high efficacy, deliver a leukemia-specific siRNA to leukemic cells and thus reduce the disease burden in mice. Fusion oncogenes thus represent disease specific targets for RNAi and should be exploited to realize a new mode of personalized treatment in leukemia patients.

Supplementary Material

Figure 6. Efficient uptake of LNP-siRNA formulations in hematopoietic tissue decreases leukemic burden in xenotransplant leukemia mice.

A. In vivo delivery of LNPs in different tissues (liver, heart, spleen, kidney, brain) of normal NSG mice at 48 hours after the start of treatment with 3 LNP-CTRL siRNA i.v injections (5mg/kg dose) by fluorescence microscopy (image representative of n=3).

B. Percentage of Dil (LNP) positive human leukemic cells in the bone marrow of xenotransplant NSG mice at 48 hours after the start of treatment with 3 LNP-CTRL siRNA i.v injections of indicated dose and route of delivery (mean ± SEM, n=3).

C. Subcellular distribution of LNP-siRNA in Dil (LNP) positive human leukemic cells in the bone marrow of NSG mice 48 hours after start of treatment with 3 LNP-CTRL siRNA i.v injections as shown by confocal imaging.

D. Anti-leukemic effect of LNP-anti-BCR-ABL siRNA in vivo, as shown by IVIS imaging of bioluminescence in NSG mice which received a transplant of K562L.GFP cells and were treated with LNP-CTRL siRNA or anti-BCRABL siRNA (before and after treatment with 4 and 10 i.p injections over a period of 35 days) (n=3).

E. Anti-leukemic effect of LNP-anti-BCR-ABL siRNA in vivo. Graphical representation of quantitation of IVIS imaging of bioluminescence in NSG mice which received a transplant of K562L.GFP cells and were treated with LNP-CTRL siRNA or anti-BCRABL siRNA (before and after treatment with 4 and 10 i.p. injections over a period of 35 days) (n=3).

F. RT-PCR validation of in vivo BCR-ABL knockdown in sorted K562L.GFP xenotransplant cells from myelosarcoma tissue of NSG mice which received a transplant of K562L.GFP cells and were treated with 10 i.p injections of 5mg/kg LNP-CTRL siRNA or anti-BCRABL siRNA (mean ± SEM, n=3).

* indicates P<.05, ** indicates P<.01, ns, not significant.

Acknowledgement

We thank Silke Glowotz, Martin Wichmann, Anitha Thomas and Colin Walsh for technical support. We express sincere thanks to the patients for their participation in the study. We thank Prof. Dr. Alf Lamprecht and Dr. Manusmriti Singh for providing us nanoparticles during the initial experiments. We thank the staff of the Central Animal Facility and Matthias Ballmaier from the Cell Sorting Core Facility (supported in part by the Braukmann-Wittenberg-Herz-Stiftung and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) of Hannover Medical School.

Funding Sources

This study was supported by the Rudolf-Bartling Stiftung, an ERC grant under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (No. 638035), grant 111267 from Deutsche Krebshilfe, DFG grant HE 5240/5-2 and HE 5240/6-2; grants from Dieter-Schlag Stiftung and a Terry Fox Foundation Program Project Award to RKH.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

N.J. and M.H. designed the research; N.J., A.S., A.C., M.S., R.B., M.S., F.K., R.L., F.N., K.W. S., M.S., D.G.K., K.B., H.P.V., M.E., A.G., F.T., R.K.H., E.R., P.C. and M.H. performed the research; N.J., A.S. and M.H. analyzed the data. N.J. and M.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosure of Conflict of interest

Euan Ramsay is an employee of Precision Nanosystems. Pieter Cullis is founder of Precision Nanosystems. The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.De Kouchkovsky I, Abdul-Hay M. Acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2016 update. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6(7):e441. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chavez-Gonzalez A, et al. Novel strategies for targeting leukemia stem cells: sounding the death knell for blood cancer. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2016 doi: 10.1007/s13402-016-0297-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coelho T, et al. Safety and efficacy of RNAi therapy for transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):819–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgerald K, et al. A Highly Durable RNAi Therapeutic Inhibitor of PCSK9. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(1):41–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon SD, et al. Effects of Patisiran, an RNA Interference Therapeutic, on Cardiac Parameters in Patients With Hereditary Transthyretin-Mediated Amyloidosis. Circulation. 2019;139(4):431–443. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorenzer C, et al. Going beyond the liver: progress and challenges of targeted delivery of siRNA therapeutics. J Control Release. 2015;203:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rungta RL, et al. Lipid Nanoparticle Delivery of siRNA to Silence Neuronal Gene Expression in the Brain. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2013;2:e136. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jyotsana N, et al. RNA interference efficiently targets human leukemia driven by a fusion oncogene in vivo. Leukemia. 2018;32(1):224–226. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belliveau NM, et al. Microfluidic Synthesis of Highly Potent Limit-size Lipid Nanoparticles for In Vivo Delivery of siRNA. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2012;1:e37. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2012.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semple SC, et al. Efficient encapsulation of antisense oligonucleotides in lipid vesicles using ionizable aminolipids: formation of novel small multilamellar vesicle structures. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1510(1-2):152–66. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hafez IM, Cullis PR. Roles of lipid polymorphism in intracellular delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;47(2-3):139–48. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tam YY, Chen S, Cullis PR. Advances in Lipid Nanoparticles for siRNA Delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2013;5(3):498–507. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics5030498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinstein S, et al. Harnessing RNAi-based nanomedicines for therapeutic gene silencing in B-cell malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(1):E16–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519273113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowley JD. Letter: A new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukaemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and Giemsa staining. Nature. 1973;243(5405):290–3. doi: 10.1038/243290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Druker BJ. Perspectives on the development of a molecularly targeted agent. Cancer Cell. 2002;1(1):31–6. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talpaz M, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2531–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurzrock R, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias: from basic mechanisms to molecular therapeutics. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(10):819–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-10-200305200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laurent E, et al. The BCR gene and philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemogenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61(6):2343–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorre ME, et al. Clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science. 2001;293(5531):876–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1062538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto M, et al. The two major imatinib resistance mutations E255K and T315I enhance the activity of BCR/ABL fusion kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319(4):1272–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weisberg E, Griffin JD. Mechanism of resistance to the ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in BCR/ABL-transformed hematopoietic cell lines. Blood. 2000;95(11):3498–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Branford S, et al. High frequency of point mutations clustered within the adenosine triphosphate-binding region of BCR/ABL in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia or Ph-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia who develop imatinib (STI571) resistance. Blood. 2002;99(9):3472–5. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scherr M, et al. Specific inhibition of bcr-abl gene expression by small interfering RNA. Blood. 2003;101(4):1566–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas M, et al. Targeting MLL-AF4 with short interfering RNAs inhibits clonogenicity and engraftment of t(4;11)-positive human leukemic cells. Blood. 2005;106(10):3559–66. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koldehoff M, et al. Therapeutic application of small interfering RNA directed against bcr-abl transcripts to a patient with imatinib-resistant chronic myeloid leukaemia. Clin Exp Med. 2007;7(2):47–55. doi: 10.1007/s10238-007-0125-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koldehoff M. Targeting bcr-abl transcripts with siRNAs in an imatinib-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia patient: challenges and future directions. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1218:277–92. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1538-5_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valencia-Serna J, et al. siRNA/lipopolymer nanoparticles to arrest growth of chronic myeloid leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2018;130:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urbinati G, et al. Antineoplastic Effects of siRNA against TMPRSS2-ERG Junction Oncogene in Prostate Cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takenaka S, et al. Downregulation of SS18-SSX1 expression in synovial sarcoma by small interfering RNA enhances the focal adhesion pathway and inhibits anchorage-independent growth in vitro and tumor growth in vivo. Int J Oncol. 2010;36(4):823–31. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scherr M, et al. Enhanced sensitivity to inhibition of SHP2, STAT5, and Gab2 expression in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) Blood. 2006;107(8):3279–87. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heuser M, et al. High meningioma 1 (MN1) expression as a predictor for poor outcome in acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics. Blood. 2006;108(12):3898–905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang YP, et al. Modification of polyethylene glycol onto solid lipid nanoparticles encapsulating a novel chemotherapeutic agent (PK-L4) to enhance solubility for injection delivery. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:4995–5005. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S34301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Fougerolles A, et al. Interfering with disease: a progress report on siRNA-based therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(6):443–53. doi: 10.1038/nrd2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Testa U, Pelosi E, Frankel A. CD 123 is a membrane biomarker and a therapeutic target in hematologic malignancies. Biomark Res. 2014;2(1):4. doi: 10.1186/2050-7771-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeijlemaker W, et al. A simple one-tube assay for immunophenotypical quantification of leukemic stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30(2):439–46. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutta S, Saxena R. The Expression Pattern of CD33 Antigen Can Differentiate Leukemic from Normal Progenitor Cells in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2014;30(2):130–4. doi: 10.1007/s12288-013-0317-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landesman-Milo D, et al. Hyaluronan grafted lipid-based nanoparticles as RNAi carriers for cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2013;334(2):221–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan XD, et al. The role of apolipoprotein E in the elimination of liposomes from blood by hepatocytes in the mouse. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;328(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akinc A, et al. Targeted Delivery of RNAi Therapeutics With Endogenous and Exogenous Ligand-Based Mechanisms. Molecular Therapy. 2010;18(7):1357–1364. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou PX, et al. Uptake of synthetic Low Density Lipoprotein by leukemic stem cells - a potential stem cell targeted drug delivery strategy. Journal of Controlled Release. 2010;148(3):380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiemels JL, et al. Prenatal origin of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children. Lancet. 1999;354(9189):1499–503. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)09403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma X, et al. Rise and fall of subclones from diagnosis to relapse in pediatric B-acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6604. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mullighan CG, et al. Genomic analysis of the clonal origins of relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2008;322(5906):1377–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1164266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(16):1541–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1400972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernt KM, Hunger SP. Current concepts in pediatric Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front Oncol. 2014;4:54. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ley TJ, et al. Genomic and Epigenomic Landscapes of Adult De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(22):2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Hare T, Corbin AS, Druker BJ. Targeted CML therapy: controlling drug resistance, seeking cure. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16(1):92–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright JR, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of erythropoietin in non-small-cell lung cancer with disease-related anemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(9):1027–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hong DS, et al. A phase 1 dose escalation, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic evaluation of eIF-4E antisense oligonucleotide LY2275796 in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(20):6582–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jyotsana N, Heuser M. Exploiting differential RNA splicing patterns: a potential new group of therapeutic targets in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2018;22(2):107–121. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2018.1417390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tefferi A, et al. A Pilot Study of the Telomerase Inhibitor Imetelstat for Myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):908–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Geisbert TW, et al. Postexposure protection of non-human primates against a lethal Ebola virus challenge with RNA interference: a proof-of-concept study. Lancet. 2010;375(9729):1896–905. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60357-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang X, et al. Targeting the RAS/MAPK pathway with miR-181a in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dorrance AM, et al. Targeting leukemia stem cells in vivo with antagomiR-126 nanoparticles in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29(11):2143–53. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang X, et al. Targeted delivery of microRNA-29b by transferrin-conjugated anionic lipopolyplex nanoparticles: a novel therapeutic strategy in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(9):2355–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang X, et al. miR-22 has a potent anti-tumour role with therapeutic potential in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11452. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang X, et al. Eradication of Acute Myeloid Leukemia with FLT3 Ligand-Targeted miR-150 Nanoparticles. Cancer Res. 2016;76(15):4470–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.