Abstract

The generation of magnetic field in an electrically conducting fluid generally involves the complicated nonlinear interaction of flow turbulence, rotation and field. This dynamo process is of great importance in geophysics, planetary science and astrophysics, since magnetic fields are known to play a key role in the dynamics of these systems. This paper gives an introduction to dynamo theory for the fluid dynamicist. It proceeds by laying the groundwork, introducing the equations and techniques that are at the heart of dynamo theory, before presenting some simple dynamo solutions. The problems currently exercising dynamo theorists are then introduced, along with the attempts to make progress. The paper concludes with the argument that progress in dynamo theory will be made in the future by utilising and advancing some of the current breakthroughs in neutral fluid turbulence such as those in transition, self-sustaining processes, turbulence/mean-flow interaction, statistical and data-driven methods and maintenance and loss of balance.

1. Introduction

1.1. Dynamo Theory for the Fluid Dynamicist

It’s really just a matter of perspective. To the fluid dynamicist, dynamo theory may appear as a rather esoteric and niche branch of fluid mechanics — in dynamo theory much attention has focused on seeking solutions to the induction equation rather than those for the Navier-Stokes equations. Conversely, to a practitioner dynamo theory is a field with myriad subtleties; in a severe interpretation the Navier-Stokes equations and the whole of neutral fluid mechanics may be regarded as forming a useful invariant subspace of the dynamo problem, with — it has to be said — non-trivial dynamics. In this perspective, I shall attempt to present the important and interesting developments in dynamo theory from the point of view of a fluid dynamicist, pointing out common themes. I shall focus on explaining how recent developments in fluid mechanics can contribute to future breakthroughs for magnetohydrodynamic dynamos.

This is not a review in the typical sense. Although I shall present the key results and features of dynamo theory, I shall not be exhaustive by any means. This perspective is focused on those areas of dynamo theory that I believe are both accessible and of interest to fluid dynamicists, drawing analogies with other areas of fluids where necessary. It is also concentrated on those areas that I believe offer the greatest scope for imminent breakthroughs. These are not necessarily those areas of research that lead to the most accurate modelling of any given astrophysical object; though it is undoubtedly the case (as described in the next section) that the generation of magnetic fields in these objects nearly always forms the motivation for dynamo investigations. Further details of dynamo theory are contained in myriad reviews and monographs, for example those of Moffatt (1978); Krause & Raedler (1980); Brandenburg & Subramanian (2005); Jones (2008) and the recently published monograph of Moffatt & Dormy (2019) and review of Rincon (2019).

We begin, however, by giving motivation for the study of dynamos— much of which arises from observations of cosmical magnetic fields, including those of planets, stars, galaxies and disks.

1.2. Motivation

1.2.1. The Geomagnetic Field

The Earth’s magnetic field is presently predominantly dipolar with a mean surface strength of approximately 40μT. Currently the dipole axis is offset by about 10° from the rotation axis. Paleomagnetic records indicate that the magnetic field has persisted for greater than three billion years and has always had a significant dipole component (see e.g. Dormy et al. 2000; Aubert et al. 2010). Figure 1 shows how the record is punctuated by episodic reversals of the polarity of the dipole component; whilst the magnetic field reverses (in a time of about 104 years) the field energy decreases and the field becomes smaller scale and more multipolar. The figure clearly shows the timescale between reversals of the field is exceptionally long, with some events (superchrons) lasting over ten million years. The Earth’s magnetic field can currently be measured at the surface to spherical harmonic degree 13, with higher harmonics being screened by remnant magnetism of the crust. In addition to long term variation of the field, it is also subject to ‘secular variation’, which is seen in current and historical observations (Jackson et al. 2000). Here the spatial structure and strength of the field varies with timescales ranging from years to centuries, with significant features including the ‘Westward Drift’ of magnetic flux patches and changes in the length of day. These changes arise because of the interaction of magnetic fields with flows in the electrically conducting fluid outer core of the Earth.

Figure 1.

The Geomagnetic record showing the history of magnetic field reversals (source Wikipedia). The black/white bars relate to magnetic fields of opposite polarities.

1.2.2. Solar System Planets

Most, if not all, solar system planets currently possess or have possessed dynamogenerated magnetic fields. Even smaller satellites such as Ganymede and the Moon show signs of current or historic dynamo action. It seems as though magnetic field generation is possible whether the planet is terrestrial, a gas giant, or an ice giant. It is therefore expected, and there is some observational evidence to support the theory, that many exoplanets should also be capable of dynamo action (Shkolnik et al. 2008).

As is the case for the Earth, dynamo action usually takes place in the interior of planets but the magnetic fields are measured as a potential field having diffused through poorly conducting regions. These potential fields are usually decomposed into spherical harmonics with amplitudes given by the so-called Gauss coefficients (see e.g. Schubert & Soderlund 2011). Briefly, the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn possess strong dipole dominated magnetic fields. Jupiter’s field, confirmed by the Pioneer 10 flyby, has a largely axial dipole and, with a mean surface strength of 550μT, has the strongest field in the solar system. Before the recent Juno mission the observations of the magnetic field had a poor resolution (up to spherical harmonic degree three), though recent flybys by the Juno satellite are beginning to establish that the magnetic field has much more structure at smaller scales and a distinct hemispheric asymmetry (see e.g. Connerney et al. 2018). It is worth mentioning at this point that the Juno mission will probably give us the closest direct observation of a naturally occurring dynamo generated magnetic field; it will be fascinating to follow the progress of the mission. Saturn’s magnetic field, first revealed by Pioneer 11, has been measured to spherical harmonic degree three and has a mean surface strength of 30μT. The axis of the dipole is remarkably aligned with the rotation axis (with an offset of less than 1°) meaning that the results are consistent with the field being axisymmetric. As we shall see in section 2.4.3, it is not possible for such a field configuration to be generated by dynamo action (Cowling 1933); this prompts the widely held belief that Saturn’s magnetic field exists solely to have annoyed Cowling.

The terrestrial planets — possessing iron-alloy central cores, silicate mantles and rocky crusts — also largely exhibit dynamo generated magnetic fields. Mercury’s magnetic field, the weakest in the solar system at 0.3μT is dipole dominated, with the dipole largely aligned with the rotation axis; similarly the magnetic field of the Jovian satellite Ganymede is an axially aligned dipole of about 1μT. Meanwhile the Moon and Mars do not have magnetic fields that are currently maintained by dynamo action, but there is evidence of extinct dynamos in both cases (see Schubert & Soderlund (2011) and the references therein). It is unclear in both cases when, or why, the dynamo switched off, though theories for the cessation of such dynamos usually involve the cooling of the body leading to the unsustainability of thermal convection or the inner core of the body growing to such a size to make dynamo action inefficient. Venus has no measurable intrinsic magnetic field. It may be that the absence of an inner core in Venus means that dynamo action is not possible or that the core is not convective at all. Finally the ice giants Neptune and Uranus have magnetic fields as discovered by the Voyager 2 flybys. These planets possess fundamentally different multipolar magnetic fields, with mean surface field strengths of 30μT, and with the dipole component exhibiting a significant tilt from the rotation axis.

1.2.3. The Sun and Stars

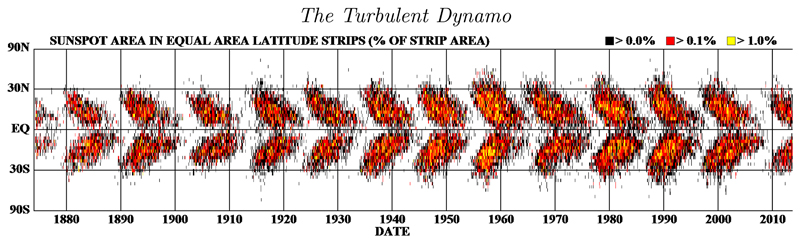

Arguably the most remarkable example of natural dynamo action is the solar activity cycle (Brun & Browning 2017; Hathaway 2015). Solar activity has been observed for many centuries, with both ancient Chinese and Athenian observations of sunspots being recorded. Sunspots have been systematically observed since the early seventeenth century, when Galileo turned the newly invented telescope towards our nearest star. It is now clear that solar magnetic activity exhibits an astonishingly systematic spatio-temporal behaviour. Sunspots appear in flux belts confined between the equator and latitudes of about ±30°. They show cyclic activity with a period of approximately eleven years; as the cycle progresses the latitude at which activity is found moves in a wave from midlatitude to the equator, before dying out — as shown in the solar butterfly diagram of figure 2. Note that the activity in this diagram is basically symmetric about the equator; this sunspot activity has been linked to magnetic fields though the Zeeman splitting of spectral lines. The sun has an azimuthally averaged field of a few hundred μT and the large-scale radial magnetic field changes sign across the equator and changes parity every eleven years, giving a 22-year magnetic cycle. The sunspot field reverses at sunspot minimum, whilst the coronal field reverses out of phase at sunspot maximum. The sun also possesses small-scale magnetic fields, which are only weakly coupled with the solar cycle.

Figure 2.

The butterfly diagram of the solar cycle. This shows the positions of the spots for each rotation of the sun since 1874. Magnetic activity first appears at mid-latitudes, widen, and then moves towards the equator as each cycle progresses (image courtesy of D. Hathaway).

The long-term dynamics of solar activity can be established from both direct and indirect observations. Telescopic observations demonstrate the modulation of the basic eleven year cycle and also reveal the presence of a period in the seventeenth century, known as the Maunder Minimum, when sunspots were almost completely absent. Interestingly, as the Sun emerged from this minimum sunspots were to be found solely in the southern hemisphere (Ribes & Nesme-Ribes 1993). Indirect observations of terrestrial isotopes (see Usoskin (2017)), whose production rate is anti-correlated with magnetic activity, show that the solar cycle persisted through the Maunder Minimum (Beer et al. 1998) and that minima such as the Maunder Minimum are recurrent events, that appear in clusters — so called “super-modulation” (Weiss & Tobias 2016; Beer et al. 2018).

Our understanding of the origin of the solar magnetic field owes much to observations of magnetic field generation in other stars. Stellar observations can obviously be used to calibrate dynamo theories, but will also give a clue as to past and future behaviour. The results from such observations are varied and bewildering to the non-expert (and sometimes to the expert). For our purposes it is sufficient to state the main results. For solar-like main-sequence stars, broadly speaking magnetic activity increases with rotation rate. There is a systematic increase in magnetic field strength with decreasing Rossby number of the star (here defined as Ro = u rms/2Ωℓ where u rms is a typical velocity, ℓ is a characteristic lengthscale given by mixing length theory), until activity levels off past a threshold in Rossby number (typically Ro ≈ 0.1 – 0.3). Interestingly this threshold appears to be independent of the mass of the star. It is also the case that many of these stars exhibit activity cycles similar to the solar cycle. The period of the cycle is also a function of Rossby number, with the cycle period decreasing with Rossby number (i.e. faster rotators have shorter period). Finally for these stars the morphology of the generated field also appears to depend on rotation rate, with faster rotators being more dominated by their zonal fields (See et al. 2016). Other stars show a wide variety of behaviour, depending on their mass, age and spectral type (for example whether they exhibit convection in a core or in an envelope plays a major role). Young stars (e.g. fully convective T-Tauri stars) have strong fields (average field strengths of around 0.2T). Suffice to say that stellar magnetic fields are ubiquitous and the properties of the generated field depend on the nature of the turbulence and the rotation rate of the star. The interested reader is directed to the excellent review by Brun & Browning (2017) for more details.

1.2.4. Galaxies and Galaxy Clusters

The properties of magnetic field in galaxies (including our own galaxy) have been extensively measured, with a variety of observational techniques — see Brandenburg & Subramanian (2005); Beck (2015) and the reviews referenced therein. Our own galaxy has an estimated local field strength of about 5 × 10–10 T, which is a typical amplitude for fields in galaxies. The magnetic field in galaxies usually has an ordered and a tangled component; in spiral galaxies the large-scale order manifests itself over several kiloparsecs. Usually the random component is strongest in the spiral arms, whilst the regular field extends into the interarm regions.

Galaxy clusters are the largest bound systems in the universe and are found to have magnetic fields; for these the total magnetic fields are estimated to be of the order of 10–11–10–9T. For most astrophysical objects it is now widely accepted that dynamo action is the only mechanism that can explain their magnetic properties and the persistence of the field for many ohmic decay times. For the galactic dynamo there appears still to be some debate (as the magnetic decay times for such vast objects are enormous), though there are a number of very significant arguments pointing to the dynamo origin of such fields (see e.g. Kulsrud & Zweibel 2008; Brandenburg & Subramanian 2005).

1.2.5. Accretion Discs

Accretion discs are gaseous discs of material spinning around a central object (for example young stars, white dwarfs, neutron stars and black holes). Although direct observations of dynamo-generated magnetic fields in such objects is difficult (though see Donati et al. (2005)), proxies such as emission or the magnetism of meteorites formed in the disc around the young sun give indirect evidence. Direct observations may place upper limits on the strength of any generated magnetic fields. However it is believed that magnetic fields play an important role in the collimation of jets and the sustainment of accretion (as we shall see later). The dynamo in such discs is very interesting theoretically — being essentially nonlinear (Tobias et al. 2011a ) — with many of the characteristics of the transition to dynamo action being similar to those for the transition to turbulence in wall-bounded flows (see e.g. Waleffe (1997); Barkley (2016)). We shall discuss in details these essentially nonlinear dynamos in section 7.

2. Fundamentals

“So many dynamos”

A well-known Palindrome

In this section we introduce the fundamentals of dynamo theory, identifying important analogies for fluid dynamicists. More details can be found for example in the excellent expositions and reviews referred to below.

2.1. Equations and Boundary Conditions

2.1.1. The induction and momentum equation

Dynamo theory typically (minimally) involves the construction of solutions to the pair of coupled partial differential equations for the evolution of the velocity field, u and the magnetic field B in an electrically conducting fluid under the magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) formalism. A complete derivation of the equations and a discussion of their applicability in any given physical situation is beyond the scope of this perspective; the interested reader is directed to Moffatt & Dormy (2019) and Jones (2008) for details of the derivation. Briefly, under the MHD approximation, which combines the non-relativistic Maxwell equations of electrodynamics with Ohm’s law for a moving conductor, these take the form

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

| (2.3) |

Here the standard fluid parameters are ρ, which is the density of the fluid, p which is the pressure and ν is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid, whilst F represents all the body forces (such as buoyancy or mechanical driving) acting to drive the fluid motion. The additional force term in the Navier-Stokes equations is termed the Lorentz force F Lor = j × B and arises owing to the interaction of the magnetic field with the current j flowing through the conductor. The current is itself given by the pre-Maxwell version of Ampère’s Law, i.e.

| (2.4) |

and hence

| (2.5) |

Here, and henceforth in this paper, μ is the permeability. The evolution equation for the magnetic field given by (2.2) is termed the induction equation. Here η = (μσ)–1 is the magnetic diffusivity which is a property of the conducting fluid, with electrical conductivity σ. Magnetic diffusivity is large for poor conductors. In circumstances in which the magnetic diffusivity is constant, (2.2) simplifies (utilising (2.3)) to

| (2.6) |

2.1.2. Magnetic Boundary Conditions

The induction and momentum equations are usually (though not always) solved in a finite domain subject to the imposition of boundary conditions on the fluid velocity and magnetic field. The boundary conditions for the fluid velocity are straightforward and standard; usually one considers impenetrable boundaries with either stress-free or no-slip conditions on the tangential component of the velocity.

The magnetic boundary conditions are more problematic and usually involve some degree of simplification. Typically this involves considering the fluid in a domain V with an exterior bounding surface S, external to which is either an insulator or a perfect conductor. If the region outside of the evolution of the dynamo fluid is perfectly conducting, surface charges, ρ S, and surface currents, j S, are allowed on the boundary. If we define [.] as the jump across the surface S and n as an outward pointing normal to that surface, then integrating the pre-Maxwell equations across the surface gives

| (2.7) |

where ϵ is the permittivity. If there are no surface currents or charges (i.e. for non- perfectly conducting boundaries) then B is continuous, provided μ is constant. If the region external to the solution domain does not allow currents (i.e. if this region is an insulator) then this continuity of B defines the problem. If the outside region allows currents then the normal derivative of n · B is also continuous, though the normal derivatives of the tangential components of B are not necessarily continuous (see the detailed discussion in Jones 2008).

However, if the outside of the domain is a static perfect conductor it is normal to assume that there is no trapped magnetic field there and so (for no normal flow conditions)

| (2.8) |

This gives

at a Cartesian boundary z =const, and

at a spherical boundary, r =const.

2.2. What is a dynamo?

Simply put, a self-exciting hydromagnetic dynamo is a self-consistent solution of the coupled Navier-Stokes and induction equation for which the magnetic energy,

| (2.9) |

remains finite as t → ∞. Here V is the volume over which the dynamo equations are solved, which could in principle be finite and bounded by a surface S or (in an idealisation) taken to be all space. If the volume is finite it is traditional to take the region external to the domain as being an insulator (j ext. = 0) so that the magnetic field is maintained entirely by the current distribution within the domain and so B = 𝒪(|x|–3) as |x| → ∞ (see e.g Moffatt 1978).

2.3. Energetics and Conservation Laws

As in hydrodynamics, much can be understood by deriving global conservation laws, valid in the absence of driving and dissipation. For inviscid hydrodynamic flows in the absence of body forces (such as gravity) and boundary forces the total kinetic energy and kinetic helicity defined as

| (2.10) |

are conserved (Moreau 1961; Moffatt 1969)

In the presence of a magnetic field these quantities are no longer conserved. Transfer of energy may take place between kinetic and magnetic energies via the action of induction and the Lorentz force respectively. The magnetic and kinetic energy equations take the form, after a little vector calculus and ignoring surface terms,

| (2.11) |

and for an incompressible flow

| (2.12) |

where the dissipative terms have now been included, and is the rate of strain tensor for an incompressible fluid.

Adding equations (2.11) and (2.12) for an ideal (inviscid and perfectly conducting) fluid immediately reveals that the total (kinetic plus magnetic) energy is conserved, with magnetic energy only being created at the expense of kinetic energy. The u · (j × B) term is therefore responsible for this transfer of energy and arises from inductive effects in the induction equation and the Lorentz force in the momentum equation.

In addition to the total energy there are two other quadratic invariants of the ideal system, namely the magnetic helicity and the cross helicity. The cross helicity, given by

| (2.13) |

is clearly not sign definite; neither is cross-helicity dissipation. Cross-helicity may be either amplified or damped locally and so less attention has focussed on the implications of its conservation in the non-dissipative case (though see Biskamp 2003; Yokoi 2013).

However the implications of the conservation of magnetic helicity and its role in the saturation of nonlinear dynamos has received much attention and for that reason we devote some time to it here.

2.3.1. Conservation of Magnetic Helicity

Because ▽ · B = 0, it is often useful to write B = ▽ × A. Here A is termed the vector potential for the magnetic field. Clearly A is only defined up to a choice of gauge, so that transforming A → A + ▽ψ for any scalar ψ leaves the magnetic field unchanged. It is also then convenient to ‘uncurl’ (2.2) to give

| (2.14) |

where ϕ is related to the choice of gauge.

Various choices of gauge are possible; the Coulomb gauge has

| (2.15) |

The winding gauge (suitable for calculations in Cartesian geometries) has

| (2.16) |

where ∇H = (∂ x, ∂ y, 0) and (Prior & Yeates 2014). A numerically convenient gauge involves setting

| (2.17) |

as described in Brandenburg & Subramanian (2005)

Now, magnetic helicity is defined as

| (2.18) |

and its evolution can be easily shown to be given by

| (2.19) |

where F s represents the surface flux of magnetic helicity. Hence for a perfectly conducting fluids, with no loss or gain of magnetic helicity through the boundaries (i.e. F s = 0), magnetic helicity is conserved. This has implications for dynamo action, which requires the generation or destruction of magnetic helicity, as we shall see. Magnetic helicity is a measure of the topological complexity and linkage of field lines, and in the absence of diffusive processes (by which the field can reconnect) this complexity is maintained. Furthermore magnetic helicity appears to be a more robust invariant than say total energy in the presence of small diffusion. The dissipative term for total energy, –ημ ∫V j 2 dV, may remain finite as η → 0, because j 2 gets large in this limit. However the dissipation of magnetic helicity, — 2ημ ∫V j · B dV, appears to tend to zero as η → 0, so magnetic helicity is well conserved. Of course the situation changes if magnetic helicity is allowed to enter or leave the domain of interest; it may do so via either advective or diffusive processes, as we shall see in section 6.5.2.

In hydrodynamic turbulence the presence of quadratic invariants has consequences for the nature of the cascades. Briefly, the same reasoning applies to MHD. As argued above, for small dissipation energy decays faster than magnetic helicity and cross-helicity (Biskamp 2003). Therefore, in a turbulent state, energy cascades towards small scales (analogous to the energy cascade in 3D hydrodynamics). However, the magnetic helicity cascades toward large scales (analogous to the energy cascade in 2D hydrodynamics). The inverse cascade of magnetic helicity may lead to the formation of large-scale magnetic fields — this fact may prove to be important for the generation of systematic fields by nonlinear dynamos.

2.4. The induction Equation and Kinematic Dynamos: The basics

For fluid dynamicists an obvious useful analogy can be made between the induction equation (2.2) and the incompressible vorticity equation given by

| (2.20) |

For experts on vorticity dynamics, this analogy can lead to significant insight into the dynamics of the magnetic field. Magnetic flux tubes may in certain circumstances have similar dynamics to those of vortex tubes; this analogy becomes a formal correspondence when the magnetic field and vorticity are weak. However it is important not to push the analogy too far. Equation (2.20) is a nonlinear evolution equation for the vorticity (since the advecting velocity is itself related to the vorticity), whereas (2.6) is formally linear in the magnetic field, with the system only becoming nonlinear when coupled to the momentum equation via the Lorentz force. As a rule of thumb, if the magnetic field is weak compared with the velocity it behaves analogously to the vorticity; if it is of a similar strength it behaves more like the velocity.

Important limits of the induction equation are the so-called diffusive and perfectly conducting limits. If u = 0, equation (2.6) reduces to the vector diffusion equation,

| (2.21) |

so that for no fluid motion the field must diffuse away (assuming there are no fields at infinity). Hence motion is needed to maintain magnetic field. The timescale for diffusion of field with a typical lengthscale ℓ B is given by . To give some idea of some typical diffusive timescales, we note that τ d ~ 2 seconds for ℓ B = 1 m and η = 0.04 m2 s –1, which may be appropriate for a liquid sodium experiment. Whereas for a magnetic field on the scale of the Earth’s core and a relevant diffusivity gives τ d ~ 104 years; the Sun has a diffusion time for the large-scale magnetic field of 109 years, comparable with its age. For galaxies the diffusion time of magnetic field is significantly longer than the age of the universe!

In the absence of diffusion (the so-called perfectly conducting limit where σ → ∞ and η = 0), (2.6) becomes

| (2.22) |

Sometimes this is called the frozen flux limit; the magnetic flux ∫𝒮 B · d S through the surface S bounded by any closed curve C moving with the fluid, remains fixed (Alfvén’s theorem). Hence we can think of magnetic field as being frozen into the fluid, in a similar manner to vortex lines in an inviscid fluid, Alfvén’s theorem is the magnetic counterpart of Kelvin’s circulation theorem.

2.4.1. Importance of the magnetic Reynolds number Rm

Clearly from the above discussion, magnetic field will decay away unless the advec- tive term in the induction equation is large enough to overcome diffusive effects. The relative importance of the two terms ▽ × (u × B) and η▽2 B can be established by nondimensionalising. We choose a typical length scale L which is the size of the object or region under consideration and a typical fluid velocity U. On introducing scaled variables t = (L/U)t̃, x = Lx̃, u = U ũ, and dropping tildes the induction equation becomes

| (2.23) |

where Rm = UL/η is the dimensionless magnetic Reynolds number.

In general, large Rm means induction dominates over diffusion, whilst small Rm means diffusion wins out over induction, and as we shall see minimum values of Rm for dynamo action (so-called dynamo bounds) can sometimes be found.

It is worth noting at this point, however, that Rm should only be used as a guide to determine the relative importance of advection and diffusion. In defining Rm it has explicitly been assumed that L is a typical lengthscale for both the magnetic field and the velocity (i.e. that ℓ B = ℓ U = L). This makes sense if L is the size of the astrophysical object (i.e. the largest lengthscale available). Of course this may not be the case, with the potential for ℓ B to be very different from ℓ U. For example if ℓ B ≫ ℓ U then the relative importance of advection and diffusion is given by , where ω is a typical vorticity amplitude. This may be large even if ℓ U and U are small. Such a basic misunderstanding of the limitations of the information encoded in the magnetic Reynolds number may lead to the incorrect dismissal of certain small-scale flows as the possible origin of large-scale fields. Large-scale fields, as they are weakly diffusive, require very little induction for their maintenance.

2.4.2. A useful technique: axisymmetric field decomposition

It is clear from the form of the induction equation that a non-axisymmetric flow immediately creates a non-axisymmetric field, however the converse is not true. If both the flow and field are axisymmetric then one can decompose the flow and field by setting (in cylindrical polars (s, ϕ, z))

| (2.24) |

| (2.25) |

Here s = r sin θ (where τ and θ relate to spherical polars (r, θ, ϕ)). This defines the differential rotation Ω the streamfunction ψ, the zonal field B (sometimes termed toroidal field in an axisymmetric setting) and the scalar potential A. The induction equation then simplifies to

| (2.26) |

| (2.27) |

The form of these equations will be exploited in the next section to prove so-called antidynamo theorems. Note that though both the A and B equations have advective and diffusive terms, the field stretching term, s B P · ▽Ω, only appears in (2.27) if gradients in angular velocity are present. (2.26) shows that there is no corresponding source term in the equation for A.

2.4.3. Anti-dynamo theorems

It is fair to say that the psychology of the dynamo practitioner has been strongly shaped by the early results of dynamo theory — results that showed the complexity and difficulty of achieving dynamo-generated fields. Key are the so-called anti-dynamo theorems that show the impossibility of dynamo action for large classes of magnetic fields and velocity fields with certain symmetries. We shall not reproduce all of the demonstrations and proofs here, since they are readily available from many sources (for example Jones 2008; Dormy & Soward 2007; Moffatt & Dormy 2019), but the importance of these for the subsequent direction of the development of the field can not be overstated.

Cowling’s Theorem: An axisymmetric field vanishing at infinity can not be maintained by dynamo action (Cowling 1933).

Proof: As noted above, a non-axisymmetric velocity field immediately generates non- axisymmetric magnetic field and so it is necessary to consider only axisymmetric flows and fields. The evolution of the field is therefore given by equations (2.26-2.27). Multiplying equation (2.26) by s 2 A, using the divergence theorem, and integrating over all space gives

| (2.28) |

assuming that surface terms vanish at infinity. This equation clearly shows that sA decays to zero as t → ∞ note sA can not decay to a constant since this would imply A → ∞ as s → 0. Once A has decayed there is no source term in the toroidal field equation (i.e. 2.27). Similar arguments then ensure the subsequent decay of B/s and therefore the impossibility of the creation of an axisymmetric magnetic field by dynamo action. It is important to note that it is the absence of source terms in equation (2.26) that causes the problems for dynamo action. Relaxation of the constraint of axisymmetry allows for the re-inclusion of such a source term.

The effect of Cowling’s Theorem ruling out such simple symmetric solutions made the search for any dynamo solutions (which were necessarily three dimensional!) seem a formidable task. Indeed, for a long time it was not clear that any such dynamo solutions existed. The situation is encapsulated in the following story taken from Krause (1993) (which attributes the source as Paul Roberts.) ‘Walter Elsasser and Einstein were friends in Germany before they both emigrated to the US in the 1930s. Several years after Elsasser had settled there (in the late 1930s in fact), he became interested in the origin of the geomagnetic field. Einstein paid him a visit, and (as people do) asked “What are you working on these days?”. Elsasser told him, and Einstein invited him to explain dynamo theory to him. Elsasser set up the problem and then told Einstein about Cowling’s theorem. Einstein’s response was, “If such simple solutions are impossible, self-excited fluid dynamos cannot exist”. For once, the great man’s craving for simplicity seems to have misled him.’

Other Antidynamo Theorems: There are many extensions of Cowling’s antidynamo theorem to other geometries and to slightly different setups. For example, in Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z), no magnetic field that vanishes at infinity and is independent of z can be generated by dynamo action; the proof proceeds along similar lines to that given above (see e.g. Jones 2008). Note again that this is a restriction on the form of a dynamo-generated magnetic field.

Anti-dynamo theorems placing constraints on the form of the fluid velocities that can lead to dynamo action have been proven by Bullard & Gellman (1954); Backus (1958) and in Cartesian coordinates by Zel’dovich (1957). These results essentially show that a velocity field must have all three components in order to be capable of acting as a dynamo (see the long discussion and derivation in Moffatt 1978).

In conclusion, both the field and the flow must be sufficiently complicated for dynamo action to occur. A minimal requirement is that the field must be three-dimensional and the flow must not be purely poloidal (i.e. can not be planar).

2.4.4. Bounds on dynamo action

Even for flows and fields that are not ruled out as dynamos on symmetry grounds, there are bounds that constrain dynamo action in finite domains; a crude measure of the expected efficiency of a dynamo is given by the magnetic Reynolds number Rm, which gives the ratio of advection to diffusion at a particular scale in the flow (usually taken to be the integral or system scale). The importance of Rm can be formalised in bounds derived by Backus (1958) and Childress (1969), both of which use the evolution equation for the magnetic energy E M, given by (see equation (2.11))

| (2.29) |

For field generation in a sphere of radius a, matching to a decaying potential dynamo action requires

| (2.30) |

where e max is the maximum of the rate of strain tensor (Backus 1958). Note here that Rm is defined in terms of the maximum strain (and not a typical velocity amplitude), which seems natural. A slightly different bound from (2.29) (Childress 1969) requires

| (2.31) |

Other bounds on dynamo action are also possible. However it can be shown that a steady or periodic dynamo can exist in a bounded conductor with an arbitrarily small value of the kinetic energy. Hence there is no lower bound on dynamo action when Rm is defined using the root mean square (rather than maximum) velocity, without placing limitations on the rate of strain (Proctor 2015).

Motivated by the desire to construct experimental dynamos in the laboratory, there is currently an effort to optimise the efficiency of dynamo flows given certain constraints. This involves taking the machinery developed for understanding the transition to turbulence, such as adjoint optimisation methods and using them to maximise the efficiency of dynamo velocities (Willis 2012).

2.5. Kinematic dynamos: some simple flows that work

The kinematic problem considers the induction equation in isolation, for a prescribed velocity field u. It is then natural to consider flows that are either steady, periodic in time or statistically steady. Because the induction equation is linear in the magnetic field, solutions take the form of magnetic fields that grow or decay exponentially on average and the task for the dynamo theorist is to determine which flows lead to growing solutions (i.e. which can act as dynamos) and then perhaps examine the form of the solutions as a function of Rm.

2.5.1. Kinematic dynamos

Having convinced ourselves that overly symmetric fields and flows are not good for dynamo action and that sufficient stretching is required, it is time to discuss some flows that do actually work as dynamos. These are not presented in chronological order, as we shall start with the simpler case of flows in an infinite domain, before moving onto flows in spheres and spherical shells.

The Ponomarenko Flow (Ponomarenko 1973):

Here we consider the simplest possible flow that leads to dynamo action. It takes the form of a localised discontinuous “screw” or vortex flow that in cylindrical co-ordinates (s, ϕ, z) is given by

| (2.32) |

where Ω and U are constants. Note that this flow is not planar, owing to the presence of the throughflow U ẑ, and has kinetic helicity, H = u · ω = 2UΩ. We shall see the importance of kinetic helicity for large-scale dynamos in section 5. Strong shear naturally occurs at (the physically unrealistic) discontinuity at s = a. In principle there are two independent parameters defining the flow U and Ω. These can be re-expressed in terms of an overall amplitude of the flow given by U amp = (U 2 + a 2Ω2)1/2 and the pitch angle χ = U/aΩ.

The trick for elegant solution for the kinematic dynamo modes in such a configuration is to note first that the flow is steady and, together with the linearity of the induction equation, this implies that magnetic field will either grow or decay exponentially in time, with potentially a complex growth-rate λ = σ + iω. Secondly, the flow is independent of z and ϕ and therefore monochromatic magnetic fields can be sought in those directions. It is therefore advantageous to seek solutions of the form B = b(s) exp (λt + imϕ + ikz), where m and k are the azimuthal and vertical wavenumbers, which must be non-zero to avoid the anti-dynamo theorems discussed earlier.

This model is extremely illuminating as it can be solved pseudo-analytically (see Jones 2008) for details; marginally stable solutions can be found by setting Re(λ) = 0 (for a given Rm = aU amp/η, χ, ka and m). The Ponomarenko flow is indeed a dynamo! It can be thought of as a prototype dynamo that is a model of vortical plume. Dynamo action sets in at Rm crit = 17.72, for ka crit = –0.3875, m = 1, a 2 ω/η = –0.41 and χ = 1.31, so the optimal pitch is 𝒪(1). The magnetic field is strongest near s = a, where it is generated by (the unphysical) shear. Although it is important to examine how dynamo action onsets, it is also, as we shall see, of great interest to determine the behaviour at large Rm. Asymptotic solutions of the Ponomarenko dynamo (in the form of Bessel functions) show that (Gilbert 1988) the fastest growing modes are given by

| (2.33) |

In the presence of viscosity, velocities with discontinuities are not realistic and so the Ponomarenko dynamo has been extended to the continuous case where u = sΩ(s)ϕ̂ + U(s)ẑ, where Ω(s) and U(s) are smooth functions (Gilbert 1988).

The Roberts Flow (Roberts 1972a):

Perhaps the most illuminating, kinematic dynamo flow is the so-called G.O. Roberts flow. This flow, like the Ponomarenko flow, is specially crafted to circumvent both the Cartesian version of Cowling’s anti-dynamo theorem and the planar velocity anti-dynamo theorem, whilst still remaining fairly tractable.

The G.O. Roberts flow is the special case of the well-studied ABC (Arnol’d, Beltrami and Childress) flow in Cartesian co-ordinates (x, y, z) in an infinite domain given by

| (2.34) |

For the Roberts flow A = B = 1, C = 0, so that u(x, y) = (cos y, sin x, sin y + cos x). This flow is two-dimensional (in the sense that it only depends on two coordinates), but it has all three components (thus not falling foul of the planar flow anti-dynamo theorem).

Before discussing the dynamo properties of the Roberts flow, it is useful to describe some of its basic hydrodynamic properties. The Roberts flow is integrable in the sense that it can be written in terms of a single steady streamfunction ψ(x, y), so that

| (2.35) |

where ψ = sin y + cos x.

The flow takes the form of an array of helical cells with throughflow, see Figure 3(a). It has a typical horizontal spatial scale of 2π and an infinite vertical scale. Moreover the winding sense of each helix in the array is the same. This ensures that the normalised relative kinetic helicity, defined to be

| (2.36) |

is unity (a so-called maximally helical flow); the importance of helicity for the large-scale dynamo properties of the flow will be discussed at some length in section 5.3.1.

Figure 3.

(a) Contours of the streamfunction ψ for the G.O. Roberts flow. Positive (and zero) contours are solid and negative contours are dashed. (b) Growth rate σ as a function of wavenumber, k z for various Rm (after Roberts 1972a ). (c,d) Scaled magnetic energy in the plane z = 0 for two different Rm = 16 and 512. As Rm is increased the field is expelled into magnetic boundary layers of width 𝒪(Rm –1/2). Note only the domain between 0 and 2π is shown. The magnetic energy is scaled between 0 and 1. Figure courtesy of Andrew Clarke.

Roberts utilised the same considerations as Ponomarenko (though a year previous) to search for magnetic field solutions to the induction equation of the form

| (2.37) |

where b(x, y) is periodic in x and y (including the possibility that b(x, y) has a mean part). The solution of the two-dimensional problem requires spectral methods yielding a matrix eigenvalue problem for the growth-rate σ = Re(λ) as a function of the wavenumber k z and Rm. For each value of Rm there is an optimal value of k z that maximises the growth rate, as shown in Figure 3(b).

The form of the magnetic field for this flow is very illuminating. Figure 3(c,d) shows the magnetic energy in the plane z = 0. For this steady flow the field is generated by the flow between the stagnation points. As Rm is increased the field is expelled into magnetic boundary layers of width 𝒪(Rm –1/2) enhancing diffusion (though the length of the filamentary field structures is determined by the geometry of the flow). This is therefore an example of a small-scale dynamo — the field generated is dominated by structure at a scale smaller than a typical scale in the velocity; such a dynamo relies on the stretching overcoming the dissipative effects of diffusion.

In a tour-de-force paper Soward (1987) analysed the behaviour of the Roberts dynamo at high Rm utilising asymptotic methods. He showed that the maximal growth-rate for this dynamo σ → 0 as Rm → ∞ (though very slowly — indeed

| (2.38) |

for large Rm). In the parlance of dynamo theory this makes the Roberts flow a slow dynamo — we shall discuss slow, fast and quick dynamos later.

Finally for this section we stress again that the Roberts flow is a small-scale dynamo that generates field via stretching. Although the flow is helical, this is not its defining characteristic here. Indeed, Roberts also considered a flow with no net helicity, viz. u = (sin 2y, sin 2x, sin(x + y)). Although this is a less efficient dynamo than the helical Roberts flow, it is nonetheless a (slow) dynamo. As noted by H.K. Moffatt ‘Helicity is not essential for dynamo action, but it helps’.

2.5.2. Kinematic dynamos in a spherical domain

The examples above are instructive (and similar types of flows will be utilised later to illustrate other dynamo properties). A natural question to pose, however, is whether similar types of flow can lead to dynamos in a bounded domain — the most natural examples of which are spheres or spherical shells.

In spherical geometry one may decompose an incompressible velocity field in terms of two scalar fields (Bullard & Gellman 1954), i.e.

| (2.39) |

Here T and S are the toroidal and poloidal components. Alternatively we write

| (2.40) |

where and are given by

| (2.41) |

| (2.42) |

where —l ⩽ m ⩽ l, and is the spherical harmonic.

The flow is defined by choosing the values of l and m and the corresponding radial functional form for the scalar fields (r, t) and (r, t). In a landmark paper, Bullard and Gellman, nearly twenty years before the flows discussed in the last section, chose and set , and . Having made a similar expansion to equation (2.39) for the magnetic field, they used spectral interaction rules to determine the growth-rate of the field. They reported dynamo action for this flow for high enough Rm, but unfortunately the dynamo growth was spurious (as shown by subsequent higher resolution calculations). We shall return to this unfortunate property of dynamo calculations in section 2.5.3. Although the reported dynamo action was incorrect, the work of Bullard & Gellman revitalised the field after the depressing wilderness years of anti-dynamo theorems, giving hope that self-excited dynamos were indeed possible. Generalisations and extensions of the Bullard & Gellman type dynamos have been studied by Kumar & Roberts (1975) and Dudley & James (1989).

If the non-axisymmetric components of such flows are small (𝒪(ϵ)) then it is possible to perform an asymptotic expansion with the axisymmetric components of flow and field dominating over the non-axisymmetric parts. This is the nearly axisymmetric dynamo of Braginskii (1975), which is an example of a self-consistent mean field model (see section 5).

2.5.3. A note of caution

The evolution equation for the magnetic field as described by the induction equation takes the form of a competition between magnetic field stretching (advection) and diffusion. Often these are both exponential processes; whether magnetic field grows or decays is then determined by the small difference between the efficiency of these processes. It is therefore of vital importance that both of these processes are accurately represented by the numerical scheme utilised to solve the induction equation. Failure to do so will inevitably lead to the incorrect determination of the dynamo properties of the flow. This was first demonstrated by the spurious solutions to the Bullard-Gellman dynamo (Bullard & Gellman 1954). Owing to computational limitations, the resolution chosen for the spectral scheme was not sufficient to resolve the dissipative structures (current sheets) in the magnetic field. Hence the dissipation was underestimated and dynamo action was claimed when no such sustained magnetic field generation was possible. It is always this way round. Insufficient resolution in a dynamo calculation will lead to the system appearing to be a dynamo when in fact it is not. This is troubling to computational dynamo theorists, though not as troubling to some as it should be.

It should be clear from the above discussion that any misrepresentation of the magnetic diffusion in a dynamo calculation is to be avoided at all costs. This includes not only misrepresentations that arise owing to lack of resolution, but also those that arise owing to the numerical scheme. It is often the case in fluids calculations that sub-grid processes are modelled (say by the inclusion of a hyperdiffusion, a numerical fix or by nominally solving the diffusionless problem with a stable scheme and using numerical errors to take the form of the dissipative processes (see e.g. Miesch et al. 2015)). In hydrodynamics, where there may be many competing terms in the nonlinear evolution equation for the velocity and dissipation may be small, such schemes may not be too damaging — but for dynamo calculations extreme care must be taken in interpreting the results from such schemes. Let me stress again that if one is examining the competition between two processes in the linear induction equation, one of which is known to be incorrectly represented, there is a strong chance that the results are incorrect.

3. So what’s the problem then?

The previous sections demonstrated that dynamo action is possible in simple steady flows in the kinematic regime, i.e. for a prescribed velocity field, in both infinite and finite domains. Despite the restrictions placed on dynamo fields and the velocities that generate them, growing solutions for the magnetic field are possible.

The rest of this Perspective will focus on the current issues that are troubling dynamo theorists. In this section we shall introduce each issue, indicating its importance for our understanding, before describing in subsequent sections the past and current attempts at a resolution of each issue and concluding in section 10 with possible future lines of research (many of which are based on current techniques utilised in hydrodynamics).

3.1. Turbulence — high and low Pm

The flows considered above are defined at a single spatial scale and are steady. Of course naturally occurring flows in geophysics and astrophysics are neither. In general, owing to the vast lengthscale of such flows, the Reynolds numbers of the dynamo flows are enormous and the flows are extremely turbulent — hence the title of this Perspective. Moreover similar arguments may pertain to the magnetic Reynolds number Rm. The ratio of these two non-dimensional numbers is given by the magnetic Prandtl number Pm = ν/η, which is a property of the fluid/plasma. In geophysics and astrophysics Pm is usually either very large or very small; in numerical experiments it is usually 𝒪(1). The combination of turbulence, with its large range of spatial and temporal scales to be resolved and the naturally occurring extreme values of Pm presents a formidable problem to the theorist and the numericist.

When Pm is large (Rm ≫ Re) the magnetic field can be generated on scales much smaller than the viscous dissipation scale. How dynamos (at least kinematically) behave in this regime is the preserve of Fast Dynamo Theory, which is discussed in section 4.1. The situation is reversed (and more complicated) when Pm is small (Re ≫ Rm); in this case the magnetic field dissipates in the inertial range of the turbulence; with substantial implications for the dynamo — this case is discussed in sections 4.2.1 and 4.2.3.

3.2. Organisation

The dynamos described so far tend to be small-scale dynamos in the sense that they generate field kinematically on a scale smaller than the typical velocity scale (sometimes on the diffusive scale, which gets very small as Rm increases). However observed geophysical and astrophysical magnetic fields display organisation on the scale of the astrophysical object and are sometimes called large-scale dynamos. A natural question, therefore, is “What is the origin of this organisation and how does the mechanism leading to organised flows compete with that leading the production of small-scale fields?” Can this competition be understood within a kinematic framework, or are nonlinear effects from the momentum equation required? Is it the case that the organisation arises as a consequence of turbulent interactions or despite them? These questions are discussed in section 5, where the concept of mean-field electrodynamics will be introduced and critiqued.

3.3. Saturation

From the point of view of a fluid dynamicist, the focus of dynamo theorists on the induction equation is somewhat mysterious, though, to be fair, the difficulties in finding dynamo solutions described above go some way to explaining this preoccupation. However, in the present era of massive computations, it makes no sense to make the kinematic assumption and take the velocity as prescribed. What is required is to solve the coupled Navier-Stokes and induction equations. Questions that can be addressed within this framework include: How does a turbulent small-scale dynamo saturate? Do organised fields saturate in a similar manner? Are there dynamos that operate through instabilities of a magnetic field driving a flow — if so can these lead to subcritical dynamo action? These questions are addressed in section 6

3.4. The Role of Rotation — rapid or otherwise

As we shall see in section 5, the dynamo generation of organised magnetic field requires a breaking of reflexional symmetry of the system (Moffatt 1978). In geophysical and astrophysical systems this naturally occurs via the influence of rotation (often in combination with stratification). Rotation is responsible for providing correlations that lead to the generation of a net electromotive force, in much the same way as it can drive large-scale flows via the introduction of correlations and non-trivial Reynolds stresses (see e.g. Vallis 2006). For dynamos, rotation plays a key role in determining the solutions of the induction equation. Moreover, once the field is generated it becomes dynamic in the momentum equation. In the case of rapid rotation, such as is the case in Earth’s core and in rapidly rotating stars, this is a particularly interesting and delicate issue. Magnetic fields may break leading-order geostrophic balances (leading to so-called mag- netostrophic balance) or, even if the primary balance is still geostrophic, the fields may play a crucial role in the prognostic equation for unbalanced motions, as discussed in section 8. Furthermore, the presence of strong rotation can lead to dynamo-generated magnetic field acting as a conduit to turbulence via nonlinear processes. The magnetic field can act so as to relax the constraints engendered by strong rotation, leading to more efficient (convective) driving of turbulence and strongly subcritical behaviour. All these issues are discussed in section 8.

4. Small-scale magnetic field generation

In this section we describe current research into small-scale dynamos. One problem that appears to have been solved to the satisfaction of dynamo theorists is the fast dynamo problemm.

4.1. One-scale velocity fields and fast dynamo theory

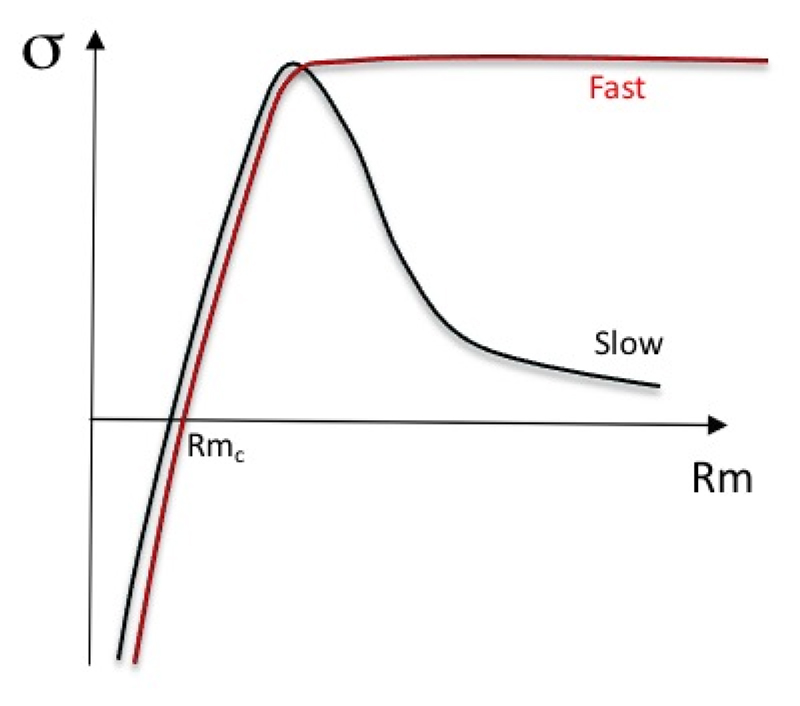

Simply put, fast dynamo theory is concerned with the kinematic generation of magnetic field (on any scale) at high Rm (such as pertains in virtually all astrophysical objects). Consider a velocity field defined at a single scale ℓ 0 with a characteristic velocity u 0. Then, defining Rm = u 0 ℓ 0/η in the usual way, the fast dynamo problem is concerned with the behaviour of the growth-rate σ(Rm) of the dynamo at high Rm. There are two possibilities, either σ → 0 as Rm → ∞ in which case the dynamo is described as ‘slow’. An alternative is that σ → const > 0 as Rm → ∞ — a so-called fast dynamo. The two possible options for the growth-rate curve are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Growth rate σ as a function of Rm for a slow dynamo (black curve) and a fast dynamo (red curve).

Moffatt & Proctor (1985) demonstrated that the eigenmodes associated with fast dy-namo action may exist, providing that they have a scale of variation 𝒪(Rm –1/2) as Rm → ∞, nearly everywhere in the fluid domain. Much of our understanding of the be-haviour of fast dynamos arises from the field of dynamical systems and mixing; progress has been made by examining the simpler problem where the flow is modelled as a discontinuous (in time) map. Indeed there are strong parallels between the two problems. I will not go into details here, but the interested reader should consult the excellent Childress & Gilbert (1995).

A central result arising from dynamical systems approaches to fast dynamo action is that which bounds the asymptotic growth-rate of the dynamo by the topological entropy of the flow (Klapper & Young 1995); see also Finn & Ott (1988). This is important as it immediately rules out the possibility of fast dynamo action for integrable flows, such as the steady -dimensional flows discussed earlier. Chaotic particle paths are required for a flow to be a fast dynamo. Chaos may be introduced in two obvious ways, either by making the flow fully three-dimensional or by introducing time dependence to the -dimensional flows (whilst for simplicity still keeping the flows at a single spatial scale). Moving to three dimensions makes computations at high Rm extremely challenging, owing to the severe constraints imposed by the requirement to resolve structures on the scale Rm –1/2 in three dimensions. Nonetheless, progress has recently been made in investigating the dynamo properties of the ABC flow given earlier as

| (4.1) |

This flow is chaotic, as shown by the Poincaré sections of the particle paths in Dombre et al. (1986) and the finite-time Lyapunov exponents shown in Figure 5(a). Calculations of the growth-rate as a function of Rm have periodically been made, since the earliest calculations (see e.g. Arnold & Korkina 1983; Galloway & Frisch 1984) extending to higher Rm as computational power has increased. Figure 5(b) taken from Bouya & Dormy (2015) shows that with current computing facilities Rm ~ 105 is possible for this flow. The figure shows that even at this value of Rm the dynamo is not in its asymptotic regime.

Figure 5.

Finite time lyapunov exponents for the ABC = 1 flow (after Brummell et al. 2001). The ABC = 1 flow is unusual in having rather large integrable KAM regions and small chaotic regions; Poincaré sections for this flow can be found in Dombre et al. (1986). (b) growth-rate as a function of Rm for the ABC dynamo (after Bouya & Dormy 2015)

A much more promising way to investigate fast dynamo action is to introduce chaos via time-dependence in a -dimensional flow. This of course has the benefit of allowing computations to proceed in 2 dimensions and so facilitate the investigation of the high Rm regime. This approach was pioneered by Otani (1988, 1993) and Galloway & Proctor (1992), who constructed similar flows. Here I give details dynamo action in the Galloway- Proctor circularly polarised (GPCP) flow, which takes the form

| (4.2) |

where

| (4.3) |

This is based on the Roberts flow, with the time-dependence being introduced via a rotation of the cellular pattern around a circle. This introduces a significant region of chaos (though regions of integrability still remain) as shown in the finite-time Lyapunov exponents of Figure 6).

Figure 6.

(a) Lyapunov exponents as a function of starting position in the plane z = 0 for the GPCP flow. (b) Growth-rate as a function of Rm for fixed k z = 0.57 for the Galloway-Proctor CP flow. Courtesy of Andrew Clarke (after Galloway & Proctor (1992)).

The magnetic field for the GPCP-flow is again generated on the small-diffusive length- scale ℓ B ~ Rm –1/2 as Rm → ∞. The growth-rate (which is a function of vertical wavenumber k z and Rm) has the form shown in Figure 6(b) for fixed k z. Interestingly, for large enough Rm the preferred wavenumber becomes independent of Rm, as does the optimised growth-rate. Notice also that this dynamo reaches its asymptotic growth-rate for moderate Rm and so is an example of a quick dynamo (Tobias & Cattaneo 2008a ), discussed below. Although it is impossible to prove numerically that these time- dependent flows are fast dynamos, all the evidence certainly points in this direction. It is now widely accepted that sufficiently chaotic flows at a single scale will act as fast dynamos. Of course it is possible to introduce time-dependence to three-dimensional, single scale cellular flows such as the ABC-flow, which has the tendency to increase the regions of chaos and hence their dynamo efficiency. Such dynamos have been investigated in both the linear and nonlinear regimes (Brummell et al. 2001).

One aspect of fast dynamo theory that is not widely appreciated is that it is only applicable for high Pm fluids, as noted by Tobias & Cattaneo (2008a). The paradigm of holding the flow fixed and increasing Rm is equivalent to increasing the Pm of the fluid. Clearly increasing Rm whilst holding Pm fixed requires an equivalent increase in Re, which will lead to a change in the form of the flow for any realistic forcing mechanism. In particular, increasing Re almost inevitably leads to turbulence with a wide range of spatial and temporal scales.

4.2. Multi-scale velocity fields

In this section we examine kinematic dynamos where the underlying flow has a spectrum of spatial scales. As discussed above, one can think of two cases; at high Pm the magnetic field dissipates at scales much smaller than the smallest eddy and one can rely somewhat on fast dynamo theory based on considering the smallest eddy alone (since the smallest eddy is the one with the fastest turnover time). At low Pm the magnetic field dissipates in the inertial range of the turbulence and life becomes more complicated. We shall start by considering the simplified (some might say over-simplified) case of random velocity fields.

4.2.1. Random dynamos - the Kraichnan-Kazantsev formulation

The discussion developed in this section summarises that of Tobias et al. (2012). Turbulent velocity fields have a coherent and random component, both of which may contribute to the dynamo properties. The simplest model of (kinematic) dynamo action driven by a purely random flow on a range of scales is the so-called Kazantsev model (Kazantsev 1968). It is an example of a solvable model for the statistics of the magnetic field based on those for a prescribed velocity, and as such may be viewed as an early example of Direct Statistical Simulation (see section 10).

The prescribed velocity takes the form of a Gaussian, δ-correlated (in time) velocity field, with zero mean and a covariance given by 〈u i(x + r, t)u j(x, τ)〉 = κ ij(x, r)δ(t – τ). Geophysical and astrophysical flows that lead to dynamo action do have means, are in general anisotropic and inhomogeneous (and this should be a feature of any description of dynamo action). However analytic progress can be made for the dynamo problem by assuming that the underlying flow is isotropic and homogeneous, in which case the velocity correlation function has the form

| (4.4) |

where r = |r|. In addition, for incompressible velocity fields we have that κ N = + (κ L + , and so the velocity statistics can be characterized by the single scalar function κ L(r). Progress is made by defining a corresponding expression for the magnetic covariance 〈B i(x + r, t)B j(x, t)〉 = H xj(x, r, t), where for similar reasons to above

| (4.5) |

Similarly, ▽ · B = 0 gives H N = H L + , and so the correlator is completely determined by H L(r, t). The evolution equation for H L, in terms of the input function κ L(r), follows from deriving the equation for the magnetic correlator

| (4.6) |

where κ(r) = 2η + κ L(0) – κ L(r) is the ‘renormalized’ velocity correlation function. Remarkably, changing variable via H L = ψ(r, t)r –2 κ(r)–1/2 leads to a related equation that formally coincides with the Schrödinger equation in imaginary time, i.e.

| (4.7) |

Here ψ describes the wave function of a quantum particle with variable mass, m(r) = 1/[2κ(r)], in a one-dimensional potential (r > 0) given by

| (4.8) |

Equation (4.7) has been investigated in detail for various choices of prescribed κ(r) (see Zeldovich et al. (1990); Arponen & Horvai (2007); Chertkov et al. (1999)). For a more thorough review see Tobias et al. (2012); Rincon (2019), though the main results are summarised below.

A homogeneous, isotropic turbulent flow with a wide-range of scales, and a well-defined inertial range can be characterised by the second order structure function Δ2(r) = 〈|(u(x,t) – u(x + r, t)).e r|2〉, where e r = r/r. The inertial and dissipative ranges are then described by the scaling exponents of Δ2(r) with Δ2(r) ~ r 2α, where α is termed the roughness exponent of the flow. In the dissipative sub-range we expect α = 1 as the velocity is a smooth function of position, whilst for the inertial range the velocity is rough and α < 1 — for Kolmogorov turbulence α = 1/3. If the slope of the energy spectrum in the inertial range is given by E k ~ k –p then p is related to the roughness exponent by p = 2α + 1.

We shall briefly describe dynamo action in the Pm ≫ 1 case, where the the velocity is smooth on the dissipative scale of the field, and the Pm ≪ 1 case where the velocity is rough there. For the smooth case, exponentially growing solutions of equation (4.6) can be found with the magnetic energy spectrum E M peaked at the magnetic dissipation scale, just as for the single-scale flows considered earlier. The spectrum for the magnetic energy in the range 1/l η < k < 1/l ν has E M ~ k 3/2, independent of the spectral index for the velocity in the inertial range (Kulsrud & Anderson 1992). This regime for a smooth velocity is also referred to as the Batchelor regime, as it corresponds to that of Batchelor (1959) for passive-scalar advection.

The low Pm case is more complicated, and we shall not go into much detail here. Briefly, when Pm ≪ 1, the magnetic field dissipates in the inertial range, where κ(r) ~ r 1+α (see e.g Tobias et al. 2012). Hence in the inertial range the Schrödinger equation (4.7) has an effective potential with the following properties. At small scales the effective potential is regularised by magnetic diffusion; growing dynamo solutions correspond to bound states for the wave-function ψ. These are guaranteed to exist when 0 < α < 1. Hence, dynamo action is always possible even in the case of a rough velocity at low Pm (Boldyrev & Cattaneo 2004). However, it is important to note that the effective potential always remains ∝ 1/r 2 in the inertial range; its depth decreases as α → 0. Hence, it is harder to drive dynamo action the rougher the velocity — this has serious consequences for our ability to generate magnetic fields in liquid metal experiments, as discussed in section 9.

Equation (4.7) can be solved asymptotically and solutions demonstrate that the growthtime of the dynamo is of the order of the turnover time of the eddies at the diffusive scale (ℓ η). Moreover it shows (Boldyrev & Cattaneo 2004) that there is a dramatic increase in the effort (computational or experimental) as the velocity becomes rougher (1+α gets smaller). Hence the effort required to drive a dynamo in a rough velocity also increases.

For these random flows we may now describe the behaviour of the critical magnetic Reynolds number Rm c as one moves from large Pm to small Pm. At high Pm the effort necessary to drive a dynamo is modest. As Pm decreases through unity the viscous scale becomes smaller than the resistive scale and the dynamo begins to operate in the inertial range. There is then an increase in the effort required to sustain dynamo action. However, once the dynamo is in the inertial range, further decreases in Pm do not make any difference to the effort required (as measured by Rm c). We also note here that the Kazantsev model relates to the addition of multiplicative noise in the induction equation. Mathematically this case was considered by, for example, Laval et al. (2006) who were interested in the effects of turbulence on the dynamo threshold. They showed that there are two regimes — an intermittent regime, with a power law distribution for B and at higher Rm, a second threshold where the field saturates towards a stable non-zero value.

This picture is largely consistent with numerical models of dynamo action in random flows (Yousef et al. 2003; Schekochihin et al. 2004, 2005) as we shall see in the next section.

The Kazantsev model as proposed is extremely restrictive, though it can easily be extended to cases where the correlation time of the turbulence is finite (Vainshtein & Kichatinov 1986; Kleeorin et al. 2002), provided the growth time of the dynamo is long compared with this correlation time. Anisotropic versions of the Kazantsev model have also been constructed by Schekochihin et al. (2004b). These solvable models will also prove useful in understanding the generation of organised field (as discussed in section 5.3.4).

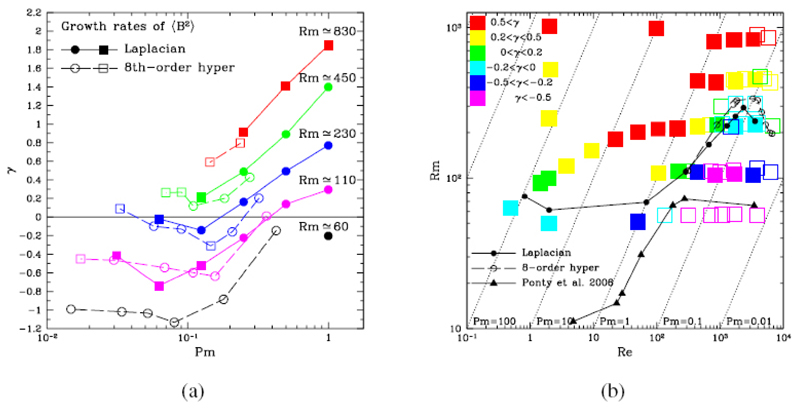

4.2.2. Numerical Solutions of Random Dynamos — the low Pm problem

Owing to the importance of understanding how dynamos onset in turbulent flows at low Pm for experiments (see section 9), there has been much numerical effort in this direction. These numerical calculations are fraught with difficulty as extremely large calculations are required to capture the separation of spatial scales. Tobias et al. (2012) calculate that the resolution of a numerical model required to answer the question of the behaviour of the critical value of Rm for dynamo action at low Pm is beyond the reach of current computational resources (requiring a calculation of size 10, 0003 points). However numerical calculations are beginning to yield some indication of the role of low Pm

In order to relate the Kazantsev models to numerical kinematic numerical simulations, where the Navier-Stokes equations are solved (with no Lorentz force) to provide the input to the induction equation, the Kazantsev models have been extended take into account departures from Gaussianity in the flow, with similar conclusions being drawn as for Gaussian flows. The results are summarised in Figure 7, which shows Rm c as a function of Re for a collection of such calculations (Schekochihin et al. 2007). At large and moderate Pm these results are consistent with the predictions of the Kazantsev model described above, as shown in Figure 7. As noted above, calculations rapidly becomes prohibitive at small Pm, and so this regime is not really accessible to direct numerical simulation (DNS), unless large eddy simulations (LES) are utilised (Ponty et al. 2007). However care must be taken here — in this regime the dynamo growth is controlled by the roughness exponent of the flow and so one would require an LES scheme with exceptional representation of the roughness.

Figure 7.

Onset of dynamo action at moderate Pm, from Schekochihin et al. (2007). (a) Growth rate of magnetic energy as a function of Pm for five values of Rm. (b) Growth/decay rates in the parameter space (Re, Rm). Also shown are the interpolated stability curves Rm c as a function of Re based on the Laplacian. Hyperviscous runs are shown separately.

Turbulence is, however, significantly more complicated than random flows that are δ-correlated in time, limiting the applicability of the Kazantsev model. For these flows it should be the case that characteristics other than the spectral slope of the velocity (and hence the roughness exponent) control the dynamo growth. We discuss this case in the next section.

4.2.3. Flows with coherence

In this section we consider the case more relevant to geophysical and astrophysical flows, where the flow has two components, a random component as described above and a systematic component whose coherence time is long compared with its turnover time. Such coherent structures, such as long-lived vortices, are ubiquitous in flows where rotation and stratification are important. The structures also exist on a wide range of spatial scales and so it is natural to ask what determines the kinematic dynamo growth- rate in a multi-scale flow with coherent structures.

The theory for such flows (which do not now have short correlation times) was developed by Tobias & Cattaneo (2008a , b ). This was achieved in two stages, the first step involved demonstrating that for such flows, knowledge of the form of the spectrum is not enough to determine the dynamo properties. They considered a flow with both long-lived vortices and a random component with a well-defined spectrum. They took advantage of the G.O. Roberts trick for dynamos with -dimensional velocities, by synthesising the flows from solutions to the active scalar equations. They also generated a second (random) flow with the same spectrum as the first by randomising the phases of the spectral components. They found that the flow with coherent long-lived structures is a much more efficient dynamo than the flow that is purely random. Here, by efficient we mean that at the same Rm the dynamo growth-rate is higher for the coherent flow. The sustained systematic stretching from the long-lived coherent structures is pivotal in generating field efficiently. In particular, helical vortices are able to generate magnetic field structures — in this case the field generated takes the form of a helix reminiscent of that generated by a Ponomarenko dynamo.

It is now reasonable to assume that a multi-scale kinematic dynamo will be dominated by the coherent parts of the flow — the long-lived structures (rather than the temporally δ-correlated random components) will determine the dynamo growth-rate and the form of the field. So, if a dynamo consists of a superposition of such coherent eddies with a range of spatial scales and turnover times (all shorter than their correlation time), what factors determine the small-scale dynamo growth-rate?

Progress can be made by assuming that each eddy acts as dynamo largely independently of the eddies at very different scales. This assumption was validated in a model problem by Cattaneo & Tobias (2005). A further step is to assume that each of the dynamo eddies are ‘quick dynamos’. As defined by Tobias & Cattaneo (2008a), a ‘quick dynamo’ is one that reaches a neighbourhood of its maximal growth-rate quickly as a function of Rm. Here, “quickly” is a somewhat imprecise term — though a rule of thumb would be for the growth-rate to come within 10% of its maximum for Rm ~ 10Rm c; by this definition most dynamos are quick dynamos. If this is the case then the dynamo is driven by the coherent eddy which has the shortest turnover time τ and has Rm ⩾ 𝒪(1). Both the local Rm and τ are functions of the spatial scale and so the location in the spectrum of the eddy responsible for dynamo action depends on the spectral slope as well as the magnetic Reynolds number on the integral scale.

The difference between dynamos that are dominated by random components and those that have long-lived coherent structures has recently been confirmed by Seshasayanan et al. (2017a). They considered the onset of dynamo action in a randomly forced flow subject to the effects of rotation. As the rotation is increased, the flow develops more spatial and temporal coherence with the coherent vortices eventually winning out over the random element of the flow. This has the effect of reducing the critical Rm at which dynamo action occurs, even at low Pm — the coherence engendered by the rotation turns a low Pm dynamo into a high Pm dynamo as predicted by Tobias & Cattaneo (2008a).

5. Organised magnetic field generation

It is often the case that astrophysical magnetic fields display some degree of organisation (or order) either spatially (displaying order on spatial scales large compared with the typical eddies in the turbulent flows) or temporally (displaying temporal coherence on timescales much longer than typical timescales in the turbulence) or sometimes both (for example the spatiotemporal behaviour of the solar cycle).

It is therefore natural to consider theories that describe the evolution of the “organised” components of the magnetic field (and potentially the velocity field). This could be for fields that are organised either spatially or temporally. In order to make progress it is necessary to give some mathematical precision to the concept of an organised field. This brings in the concept of averaging and forces the theorist to turn to statistical theories that are designed to provide information about these average quantities. Such theories are ubiquitous in fluid mechanics (for example Frisch 1995; Bühler 2014; Kraichnan 1965) though, owing to the historical path of research in dynamo theory, the statistical theories in the two disciplines have tended to develop along different tracks. I shall argue strongly that future progress in dynamo theory can only be made by reconciling these approaches and returning to the paradigms preferred by fluid dynamicists. Nonetheless much can be learned from the dynamo approach, which I shall briefly review here.

5.1. The Nature of Averaging

We shall be concerned with the derivation and solution of equations for the average properties of our state variables (for example B and u). We shall primarily be interested in decomposing state variables into mean (average) and fluctuating parts so that for example

| (5.1) |

Here the overbar represents a linear averaging process that (in general) obeys the Reynolds averaging rules, i.e.,

| (5.2) |

and

| (5.3) |

Hence averaging equation (5.1) gives

| (5.4) |

In terms of products it is also convenient, though not necessary, if the averaging procedure satisfies

| (5.5) |

and

| (5.6) |

There are many different forms of averaging that satisfy the above Reynolds averaging rules, and some useful forms that do not. We briefly comment on a few here.

5.1.1. Spatial and Temporal Averaging

Perhaps the most utilised form of averaging assumes that the fluctuations are characterised by a length-scale ℓ 0 (perhaps the scale of the energy containing eddies or fluctuating magnetic field). This is assumed small compared with the larger scale L of the variation in the averaged quantities. For a system-scale dynamo L will typically be 𝒪(R) where R is the lengthscale of the domain. It is then possible to define an intermediate scale a that satisfies ℓ 0 ≪ a ≪ L. The spatial average can then be defined as (Moffatt 1978)

| (5.7) |