Abstract

Background and Aims

Endoscopic surveillance is recommended in patients with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC), who refuse of want to delay surgery. Since early signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) can be inconspicuous, current surveillance endoscopy protocol entails 30 random biopsies which are time-consuming. This study aimed to compare single-bite and double-bite techniques in HDGC surveillance.

Methods

Between October 2017 and December 2018, consecutive patients referred for HDGC surveillance were prospectively randomized to the single or double-bite arm. The primary outcome was the diagnostic yield for SRCC foci. Secondary outcomes were the procedural time for random biopsies, comfort score, biopsy size and quality of specimens, the latter assessed by the presence of muscularis mucosa, artefact and proportion usable for diagnostic assessment.

Results

In total, 25 patients were randomized to the single-bite and 23 to the double-bite arm. SRCC foci were detected in 3 and 4 patients in the single and double-bite arm, respectively (p=0.70). The procedural time for the double bite arm (12 min, IQR 4) was significantly shorter than single-bite arm (15 min, IQR 6, p=0.011), but comfort score was similar. The size of the biopsies in the double-bite arm was significantly smaller than single-bite arm (2.5mm vs 3 mm, p<0.001) but this did not affect the presence of muscularis mucosa (p=0.73), artefact level (p=0.11) and diagnostic utility (p=0.051).

Conclusion

For patients undergoing HDGC surveillance, the double-bite technique is significantly faster than the single-bite technique. The diagnostic yield and the biopsy quality for SRCC were similar across both groups.

Clinical trial registration number: NCT03950908 Unique Protocol ID: FGCS protocol v.10

Keywords: Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, Signet ring cell carcinoma, biopsy, single-bite, double-bite

Introduction

Approximately 3% of gastric cancer cases arise as a result of inherited cancer predisposition syndromes, of which the most common is hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) [1]. A germline mutation of E-cadherin gene (CDH1) is found in 25% to 30% of families fulfilling the clinical criteria for HDGC, which are based on the diffuse phenotype, age of onset and number of cases in a 3-generation pedigree [2]. The penetrance of the disease is high, with an estimated lifetime risk of gastric cancer of 70% in men, 56% in women and 42% lifetime risk of lobular breast cancer in women [3,4]. Individuals found to carry a pathogenic CDH1 variant are advised to undergo risk-reducing total gastrectomy [5]. However, some patients prefer to delay gastrectomy for medical or psychosocial reasons, for example, concerns about childbearing, impact on work, fear of surgical adverse events, or comorbidities that increase the risks of surgery [6,7]. For these patients, endoscopic surveillance is recommended to provide further evidence to help in decision-making processes. For families that fulfil the clinical criteria of HDGC but in whom no identified genetic cause is found, the uncertain risk precludes surgery and endoscopic screening is offered as the only means to determine whether they are at-risk.

Previous studies have validated the utility of endoscopic surveillance [8,9]. The aim is to detect microscopic foci of in-situ or intramucosal signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) to inform the best timing of prophylactic gastrectomy in patients who want to delay surgery. Based on previous prospective studies, the yield of early SRCC is estimated to be 30-61% in mutation carriers and 6-10% in the absence of a pathogenic CDH1 mutation [8,10,11]. Currently, the recommended endoscopic protocol involves targeted biopsies of any suspicious lesions as well as a minimum of 30 mapping random biopsies specimens taken from all anatomic areas of the gastric mucosa [3]. The endoscopic lesion most commonly associated with early SRCC is the pale mucosal area, which is generally visible on white light imaging but can be better visualized with narrow-band imaging [9,10]. However, up to 60% of SRCC foci are diagnosed on random biopsies only, which suggest that there is a significant additional diagnostic yield from the random biopsies. However, this biopsy protocol is time-consuming and tedious, which significantly prolongs the duration of the procedure and might reduce patient tolerance. To save time, two specimens can be taken during a single passage of the forceps ("double-bite" technique). Previous studies on the efficacy of the multiple bite technique, in both the upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract, have generated conflicting results in terms of biopsy quality and diagnostic utility [12–16]. The aim of this prospective, randomized study was to determine the adequacy and utility of the double-bite technique in patients undergoing surveillance for HDGC.

Material and Methods

Surveillance Programme

Patients in the Familial Gastric Cancer Registry held in Cambridge fulfilling the criteria for HDGC are invited to participate in a long-term research surveillance programme assessing efficacy and safety of endoscopic surveillance using high-resolution white-light endoscopy in addition to advanced imaging modalities [autofluorescence imaging (AFI) and narrow-band imaging (NBI)] combined with targeted and mapping random biopsies. Patients enrolled in endoscopic surveillance are managed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a medical geneticist, gastroenterologists, upper GI surgeons, psychologists, nutritionists and clinical nurse specialists. All patients are counselled about the recommendation to undergo prophylactic total gastrectomy when a deleterious CDH1 mutation is detected, and all are offered a baseline endoscopy before surgery. Those who prefer to defer surgery (because of patient choice or clinical recommendation based on physical or psychological comorbidity) are offered endoscopic surveillance.

Study Design

This was a single-centre, randomized controlled trial conducted in a tertiary referral centre in the United Kingdom. We recruited patients who were >18 years of age, and with a confirmed diagnosis of HDGC as well as patients in whom no pathogenic CDH1 mutation is identified or those awaiting clarification of their genetic status (e.g owing to a lack of confirmed mutation in the family index case), but who has clinical diagnostic criteria fulfilling a diagnosis of HDGC. Patients were manually assigned by a research nurse in a 1:1 ratio to receive random biopsies either with the single-bite technique (control group) or a double-bite technique (intervention group). The protocol was approved by the Cambridgeshire research ethics committee (MREC 97/5/32). The trial was performed in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. A dedicated research nurse obtained informed consent from each patient and prospectively collected the data.

The primary outcome was the diagnostic yield of SRCC foci on random biopsies on a per-patient analysis (i.e., any patient with a positive biopsy for SRCC on 1 out of 30 biopsies would constitute a positive SRCC diagnosis). There were four secondary outcomes of the study, which included the procedural time, the comfort score, the size of the biopsy and the quality of the biopsy.

Endoscopic Protocol

Endoscopies were performed according to a standardized protocol previously described [9]. Briefly, a white-light high-resolution endoscope equipped with 85x magnification (GIF-FQ260Z; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to examine all anatomic segments of the insufflated stomach. Any abnormalities on white-light endoscopy were recorded and assessed further by narrow-band imaging magnification with or without autofluorescence imaging. The endoscopist recorded the presence and location of pale areas, which have been previously associated with early SRCC. Targeted biopsy specimens were taken from identified lesions, and 5 random biopsy specimens each were taken from the 6 anatomical regions of the stomach (pre-pyloric area, antrum, transitional zone, body, fundus and cardia). The endoscopist was only notified of the randomization group before starting the random biopsies. The single bite technique involved taking a single biopsy on each pass of the biopsy forceps. The double-bite technique involved taking an initial biopsy, carefully repositioning the forceps, and taking a second biopsy from the same anatomic area with the first specimen still attached to the forceps. Boston Single-Use Radial Jaw™ 4 forceps with a spike were used. Since there can be significant inter-patient variation in the multi-imaging time and number of targeted biopsies, the procedural time was recorded as the time between the first and the last random biopsy. The comfort was scored by an endoscopy nurse immediately after the procedure, using the modified Gloucester scale (1: no discomfort, i.e. resting comfortably throughout; 2: minimal discomfort, i.e. one or two episodes of mild discomfort well tolerated; 3: Mild discomfort, i.e. more than 2 episodes of discomfort adequately tolerated; 4: Moderate discomfort, i.e. significant discomfort experienced several times during the procedure; 5: Severe discomfort, i.e. extreme discomfort experienced frequently during the procedure).

Histologic Analysis

The clinical biopsy specimens from all eligible patients were collected on blocks, placed into pots containing formalin and transferred to the Pathology Department. Biopsies specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and periodic acid–Schiff diastase and were assessed for the presence of SRCC foci by two GI pathologists experienced in the diagnosis of SRCC. The two histologic secondary outcomes of the study were the size and quality of the biopsies. The size of the biopsies was assessed with a calibrated magnifying glass equipped with measuring scale and quantified in mm. Each biopsies specimen was also assessed for quality by two pathologists (MT and MOD), who were blinded to the study arm. Biopsy quality was categorized into three different parameters: 1) presence of muscularis mucosa, 2) presence of artefact and 3) the diagnostic utility of the biopsies. The presence of muscularis mucosa is an indicator of adequate depth of biopsy and is important as the SRCC foci are often located underneath the epithelial layer. The presence of muscularis mucosa was interpreted as binary (yes or no). Crash artefact level was scored as (i) no artefact, (ii) moderate (<50% of specimen altered by artefacts) and (iii) severe (>50% of specimen altered by artefacts). The overall diagnostic utility was scored as (i) good (>2/3 of specimen allowing histologic diagnosis), (ii) moderate (1/3 to 2/3 of specimen allowing histologic diagnosis) and (iii) poor (<1/3 of specimen allowing histologic diagnostic). For the quality assessment, diagnostic levels from individual blocks were evaluated separately.

Statistical Analysis

This study was powered to the secondary endpoint related to the procedural time. Based on preliminary measurements of the time taken to perform single and double bite biopsies, including the time to secure the biopsies in the pathology container, we estimated a difference of 180 seconds between the two techniques. Based on this, assuming a power of 0.8 and a two-sided alpha of 0.05, we estimated that at least 13 cases in each arm were required for this study.

Normality testing was performed using Shapiro-Wilk test. For descriptive statistics, parametric variables were reported using mean (standard deviation, SD) and non-parametric variables were reported using median (interquartile range, IQR). Independent Student’s T-test and, where appropriate, Mann-Whitney U test, was used to compare means, and median between groups, respectively. Categorical variables were analyzed with the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Comfort score and quality of biopsies were treated as ordinal, categorical variables and counts between categorical and ordinal variables were analysed using the Cochran-Armitage test for trend. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 24; Armonk, New York, United States, IBM Corp) and R version 3.6.2.

Results

Patients Characteristics and Targeted Biopsies Findings

In total, 48 patients were recruited into the study between October 2017 and December 2018. Of these, 25 were randomized to the single bite arm, and 23 to the double-bite arm. The number of patients successfully recruited would have allowed us to achieve a power of 0.95 for this study. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of age, gender, sedation dosage, lignocaine use, the purpose of endoscopy, presence of CDH1 mutation and number of biopsies taken (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients According to Group Assignment.

| Variable | Single-bite (n=25) | Double-bite (n=23) | All patients (n=48) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 44.0 (15.3) | 41.2 (13.4) | 42.7 (14.4) | 0.50* |

| Gender, n (%) - Males - Females |

12 (48) 13 (52) |

10 (43.5) 13 (56.5) |

22 (45.8) 26 (54.2) |

0.75&

|

| Fentanyl, μg; median (IQR) | 75 (50) | 100 (25) | 75 (50) | 0.30$ |

| Midazolam, mg; median (IQR) | 5 (1) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 0.25$ |

| Lignocaine, n (%) - No Lignocaine - Used Lignocaine |

4 (16) 21 (84) |

1 (4.3) 22 (95.7) |

5 (10.4) 43 (89.6) |

0.35#

|

| Endoscopy purpose, n (%) - Index - Surveillance |

11 (44) 14 (56) |

5 (21.7) 18 (78.3) |

16 (33.3) 32 (66.7) |

0.10&

|

| CDH1 mutation status, n (%) - Positive - Negative |

18 (72) 7 (28) |

15 (65.2) 8 (34.8) |

33 (68.8) 15 (31.3) |

0.61&

|

| Total number of biopsies taken, median (IQR) | 32 (2) | 32 (3) | 32 (2) | 0.23$ |

SD, Standard Deviation; IQR, Interquartile Range

Student’s T-test

Mann-Whitney U test

Chi-Square test

Fisher’s-Exact test

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

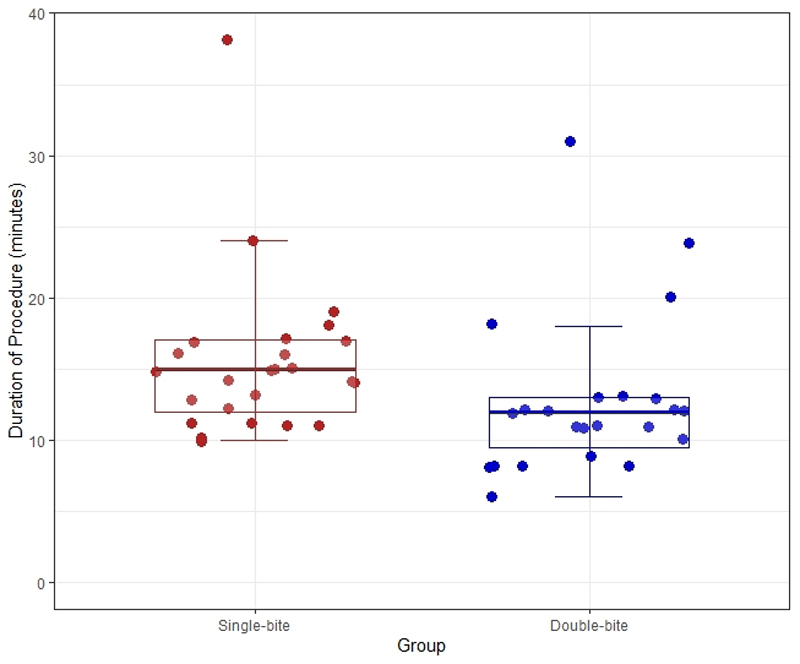

With regards to the primary outcome, 17.4% of patients randomized to the double-bite group had SRCC foci in random biopsies, compared to 12.0% for the single-bite group (p=0.70) (Table 2). The median duration of the procedure for the double-bite group was 12 minutes, which was significantly shorter compared to the single-bite arm, 15 minutes (Mann-Whitney U test, p=0.011) (Figure 1). When we assessed comfort score as an ordinal variable, there was no significant trend seen in the comfort scores between the two arms (Cochran-Armitage test for trend, p=0.081). The size of the biopsies was significantly smaller for patients in the double-bite group compared to the single-bite group (2.5mm vs 3mm, Mann-Whitney U test, p<0.001) (Figure 2). Given the smaller size of the biopsies in the double-bite arm, we assessed in more detail the quality of each biopsy. A total of 600 biopsy specimens were available for interpretation, of which 322 and 278 biopsies were from the single and double-bite group, respectively. There was no difference in the presence of muscularis mucosa, with 59.3% and 57.9% of biopsies containing muscularis mucosa in the single and double-bite groups, respectively (Chi-square test, p=0.73). Likewise, there was no significant trend seen between the two arms in the level of crash artefact to hamper histologic diagnosis (Cochran-Armitage test for trend, p=0.11). With concern to the diagnostic utility, although we found a trend towards better quality for the single-bite group, this did not meet statistical significance (Cochran-Armitage test for trend, p=0.051) and 92.8% of the biopsies in the double-bite arm were deemed to be of good diagnostic utility (Table 2).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| Outcomes | Single-bite (n=25) | Double-bite (n=23) | All patients (n=48) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | ||||

| Diagnostic yield for SRCC, n (%) | 3 (12.0%) | 4 (17.4%) | 7 (14.6%) | 0.70# |

| Anatomical location of SRCC foci - Fundus - T-zone - Multifocal (Fundus and Antrum) |

2 0 1 |

3 1 0 |

5 1 1 |

- |

| Secondary Outcome | ||||

| Duration of procedure, min; median (IQR) | 15 (6) | 12 (4) | 13 (5) | 0.011$ |

| Comfort score, n (%) - No discomfort - Minimal discomfort - Mild discomfort - Moderate discomfort - Severe discomfort |

- 15 (60) 10 (40) 0 0 0 |

- 12 (52.2) 5 (21.7) 5 (21.7) 1 (4.3) 0 |

- 27 (56.3) 15 (31.3) 5 (10.4) 1 (2.1) 0 |

0.081£

|

| Size of biopsy, mm; median (IQR) | 3(1.5) | 2.5(1) | 2.5 (1) | <0.001$ |

| Quality of biopsy, n (%) - Presence of muscularis mucosa - Presence of artefact • Not Present • Moderate (<50% biopsy altered by artefact) • Severe (>50% biopsy altered by artefact) - Global quality assessment • Good (>2/3 used for diagnosis) • Moderate (1/3 to 2/3 used for diagnosis) • Poor (<1/3 used for diagnosis) |

(n=322) 191 (59.3) - 160 (49.7) 160 (49.7) 2 (0.6) - 313 (97.2) 7 (2.2) 2 (0.6) |

(n=278) 161 (57.9) - 120 (43.2) 156 (56.1) 2 (0.7) - 258 (92.8) 20 (7.2) 0 |

(n=600) 352 (58.7) - 280 (46.7) 316 (52.7) 4 (0.7) - 571 (95.2) 27 (4.5) 2 (0.3) |

0.73& 0.11£ 0.051£ |

SRCC, Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma; IQR, Interquartile Range

Fisher’s Exact test

Chi-square test

Mann-Whitney U test

Cochran-Armitage Test for Trend

Figure 1.

Scatter plot with superimposed box plot of duration of procedure stratified by group allocation. Circles represent individual patient data, coloured by group. The bold horizontal line represents the median duration of the procedure (p=0.011).

Figure 2.

Scatter plot with superimposed box plot of the size of specimens stratified by group allocation. Dots represent individual patient data, coloured by group. Bold horizontal line represents the median size of specimens (p<0.001)

Targeted versus Random Biopsies for HDGC Surveillance

None of the patients were diagnosed with macroscopically visible cancer requiring referral for oncological treatment. There were 11 patients who were diagnosed with SRCC foci. Of these, 4 cases were diagnosed as part of targeted biopsies for visible lesions and 7 cases were diagnosed on random biopsy. Among the four cases diagnosed with targeted biopsies, in two cases, a single pale area was found in the antrum (Figure 3). A third case had multiple foci of SRCC in several pale areas at the incisura. A fourth case was diagnosed with multiple SRCC foci from several pale areas in the antrum as well as within random biopsies from the fundus. For SRCC diagnosed on the targeted biopsy, the antrum was the most common location, in keeping with the fact that pale areas are very rarely seen in the proximal stomach.

Figure 3.

Case of SRCC detected within the pale area. A) Panoramic view of the antrum with normal-appearing mucosa. B) Detailed view of the pale area on white light endoscopy. C) Detailed view of the pale area on NBI, which allows better delineation of the margins.

With concerns to SRCC foci on random biopsies, these were most often detected in the fundus. There was a single case of multifocal SRCC found during random biopsies and this patient was in the single-bite arm. (Table 3). All, but one of the cases with SRCC foci were detected in the CDH1 positive group (Table 1).

Table 3. Comparison between target and random biopsy.

| Variable | Targeted Biopsy | Random Biopsy |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with SRCC | 4 | 7 |

| Anatomical location of SRCC foci - Pre-pyloric - Antrum - Incisura - T-zone - Body - Fundus - Multifocal (Fundus and Antrum) |

0 3 1 0 0 0 0 |

0 0 0 1 0 5 1 |

SRCC, signet ring cell carcinoma

Discussion

The double-bite technique is routinely performed in clinical practice and mainly serves as a time-saving modality. This can be advantageous during procedures where multiple biopsies are required; however, it might carry the risk of sub-optimal quality of the biopsies, which can result in lower diagnostic yield. In this study, we applied this technique in the biopsy protocol for patients undergoing surveillance for HDGC. The double-bite technique reduces significantly the time required for biopsy collection. The biopsy specimens in the double-bite arm were smaller, however, this did not impact negatively on the detection of SRCC foci.

This is the first study that evaluates the efficacy of the double-bite technique in the setting of HDGC. Previous studies have assessed this technique in different clinical scenarios, with varying results. In a study involving 16 patients undergoing diagnostic gastroscopy, Padda et al, showed that the double-bite specimens were adequate for histopathologic purposes but there was a significant risk of losing samples [13]. Similarly, in another study on 84 patients, which evaluated the histopathologic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection, no difference was detected between the single and double-bite techniques. In this study, the double-bite technique was associated with a shorter procedural duration but carried a significant risk of losing samples [14]. In a study involving 12 patients with ulcerative colitis who underwent surveillance colonoscopy, the double-bite technique was vulnerable to specimen loss but also and was associated with reduced histological quality [15]. Lastly, Latorre et al showed that in the context of the diagnosis of coeliac disease the single-bite technique was superior compared to the double-bite with better specimen orientation and decreased specimen loss [16]. Taken altogether, these studies demonstrate that the double-bite technique leads to a higher rate of specimen loss and possibly, reduced quality in certain clinical contexts.

With regards to HDGC, since the SRCC foci are generally located in the deep part of the gland with early invasion of the lamina propria and muscularis mucosa, a smaller size biopsy specimen could affect the quality of biopsies. Our results showed that even though the size of biopsies taken with the double-bite technique was smaller, the muscularis mucosa was equally represented suggesting that the biopsies taken with the double-bite technique achieved sufficient depth. Furthermore, despite a slight and non-significant reduction in the proportion of the biopsy suitable for histological diagnosis from double-bite biopsies, the crash artefact level was not different between the two groups. As a result, we found that the biopsy technique did not affect the diagnostic yield of SRCC foci. Therefore, we conclude that despite a smaller size, the double-bite technique still captured the relevant compartment of the mucosa affected by the early SRCC foci.

In this study, we did not record the number of lost samples in the double-bite arm, as we always aimed to obtain 30 random biopsies according to the standard protocol. The endoscopy nurse always assisted by counting the number of samples obtained. If a sample was missing, an additional biopsy was taken to compensate. We hypothesized that if the specimen loss occurred in a significant proportion of biopsies, this would have impacted negatively on the procedural time, reducing the time difference between the two arms. Nonetheless, the time required to perform the random biopsies in the double-bite arm was significantly shorter than the single-bite arm, suggesting that the proportion of samples loss were low and the need for “extra” passes were minimal. The shorter procedural time did not affect the comfort and the doses of the sedation required. This is likely because all these patients received high doses of sedation, due to the relatively young age, the anticipated length of the procedure and the high psychological burden which required maximizing patients’ comfort

Independently from the type of biopsy protocol used, in agreement with previous data from our group, this study shows that the random biopsies have an additional yield of SRCC foci [8]. These early lesions can be associated with pale areas, however, are often completely inconspicuous even with advanced imaging. Therefore, to correctly inform about the presence of early invasive disease, random mapping biopsies are advocated. It has been described that pale areas are mostly detected in the distal stomach around the transitional zone between gastric body and antrum, therefore for appropriate histological characterization of the proximal stomach, random biopsies remain essential.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, we could not power the trial to the primary outcome as no previous data on detection of SRCC foci with the double-bite and single-bite technique were available. To formally prove similar diagnostic accuracy, a non-inferiority trial was required. Assuming an SRCC detection rate of 25% on single-bite biopsy and a non-inferiority margin of 30% relative difference, with 90% power and one-sided alpha=0.025, the total number of patients required would be 1402 (701 per group), making such a trial impossible to conduct due to the extremely low prevalence of this condition. Therefore, we are formally unable to conclude that the double-bite technique is non-inferior to the single-bite technique in detection of SRCC, however, we feel that the data provided here provide evidence that the quality of the biopsies for diagnostic use were adequate. Second, this study was conducted in a high-volume research centre by medical staffs who are very experienced in endoscopic surveillance for HDGC as well as in sample handling and histologic processing. This is in line with current recommendations suggesting that HDGC surveillance should be performed in expert centres. The results of this study are very relevant to the HDGC population, but its applicability to the general clinical setting may be more limited.

In summary, the use of the double-bite technique to obtain random biopsies for HDGC surveillance is associated with a shorter procedural duration. We did not detect any difference in the diagnostic yield between single-bite and double-bite techniques, although this trial was not designed to demonstrate non-inferiority. Adopting the double-bite technique for HDGC surveillance biopsies into clinical practice can be considered particularly when procedures are not performed with deep sedation or general anaesthetic where a shortened procedural time would be appealing to both endoscopists and patients.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Cambridge Clinical Research Center and the research nurses Tara Evans, Bincy Alias and Michele Bianchi for their help with endoscopic procedures and sample collection. We also thank the staff of the Addenbrookes Hospital Human Research Tissue Bank for providing tissue specimens. We would like to thank Dr Shalini Malhotra, Dr Ahmad Miremadi, and Dr James Chan for providing expert review of pathology specimens. We also thank Dr Mark Tischkowitz for genetic counselling, Dr Hisham Ziauddeen and Professor Paul Fletcher for psychological support; Mr Richard Hardwick for clinical management and Professor Carlos Caldas for his overall supervision of the HDGC study.

Funding

The study has received infrastructure support from the Experimental Cancer Medicine Center and Cambridge Biomedical Research Center. AP was funded by a CRUK Multidisciplinary Project Award (C47594/A21102).

Footnotes

Authors Contribution

MdP, WJ, GR performed the endoscopies. AP, SR, WW performed data collection. AP, WKT, WJ, WW and MdP analyzed the data. AP, WKT and MdP wrote the manuscript. MdP and RCF designed the study. MT and MOD performed histological diagnosis. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Fitzgerald RC, Caldas C. Clinical implications of E-cadherin associated hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Gut. 2004;53:775–778. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.022061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansford S, Kaurah P, Li-Chang H, et al. Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer Syndrome: CDH1 Mutations and Beyond. JAMA oncology. 2015;1:23–32. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Post RS, Vogelaar IP, Carneiro F, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated clinical guidelines with an emphasis on germline CDH1 mutation carriers. Journal of medical genetics. 2015;52:361–374. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pharoah PD, Guilford P, Caldas C, et al. Incidence of gastric cancer and breast cancer in CDH1 (E-cadherin) mutation carriers from hereditary diffuse gastric cancer families. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1348–1353. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald RC, Hardwick R, Huntsman D, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated consensus guidelines for clinical management and directions for future research. Journal of medical genetics. 2010;47:436–444. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.074237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mastoraki A, Danias N, Arkadopoulos N, et al. Prophylactic total gastrectomy for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Review of the literature. Surgical oncology. 2011;20:e223–226. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallowell N, Badger S, Richardson S, et al. An investigation of the factors effecting high-risk individuals' decision-making about prophylactic total gastrectomy and surveillance for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) Familial cancer. 2016;15:665–676. doi: 10.1007/s10689-016-9910-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mi EZ, Mi EZ, di Pietro M, et al. Comparative study of endoscopic surveillance in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer according to CDH1 mutation status. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:408–418. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim YC, di Pietro M, O'Donovan M, et al. Prospective cohort study assessing outcomes of patients from families fulfilling criteria for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer undergoing endoscopic surveillance. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2014;80:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw D, Blair V, Framp A, et al. Chromoendoscopic surveillance in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: an alternative to prophylactic gastrectomy? Gut. 2005;54:461–468. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.049171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Post RS, van Dieren J, Grelack A, et al. Outcomes of screening gastroscopy in first-degree relatives of patients fulfilling hereditary diffuse gastric cancer criteria. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2018;87:397–404.e392. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fantin AC, Neuweiler J, Binek JS, et al. Diagnostic quality of biopsy specimens: comparison between a conventional biopsy forceps and multibite forceps. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2001;54:600–604. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.118945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Padda S, Shah I, Ramirez FC. Adequacy of mucosal sampling with the "two-bite" forceps technique: a prospective, randomized, blinded study. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2003;57:170–173. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bae M, K M, Lee J. Study of Mucosal Sampling for Helicobacter pylori Using‘Two-bite’Technique in Relation to Time-saving. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;29:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hookey LC, Hurlbut DJ, Day AG, et al. One bite or two? A prospective trial comparing colonoscopy biopsy technique in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis. Canadian journal of gastroenterology = Journal canadien de gastroenterologie. 2007;21:164–168. doi: 10.1155/2007/851830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Latorre M, Lagana SM, Freedberg DE, et al. Endoscopic biopsy technique in the diagnosis of celiac disease: one bite or two? Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2015;81:1228–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]