Abstract

The 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak constitutes an example of the many crises that a restaurant may encounter. This article reviews a typology of crises, examines the crisis response of restaurants in Hong Kong, illustrates how local restaurants deal with this unprecedented situation and develop strategies for management and recovery. The lessons and experience gained from dealing with the SARS crisis serve as references for restaurants in other destinations when they face similar crises in future.

Keywords: Crisis management, Hong Kong restaurants, Recovery, Response to SARS

1. Introduction

Restaurants in Hong Kong have already been put under great pressure to survive in the harsh market environment resulting from the Asian financial crisis of 1997, but the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in March 2003 was a death sentence to the industry. The SARS epidemic has affected nearly 8588 people and killed 724 worldwide. Hong Kong people were afraid of venturing out to crowded public areas and shopping malls, causing a significant drop in business for restaurants. By any measure, business levels were a far shot away from the levels prior to SARS. Chinese restaurants where people eat family style from shared platters of food in a crowded environment were the worst affected having lost as much as 90% of their business since the outbreak began (Geoffrey and Prystay, 2003). This reveals vulnerability in the catering industry's ability to respond to crisis, especially epidemics like SARS that spread panic and disrupt the everyday activities of the people. However, some restaurants have managed to stay afloat, with some even turning a little profit. By studying the crisis response of these restaurants, we can formulate a crisis response and recovery plan to serve as a future reference for other restaurants facing similar disasters.

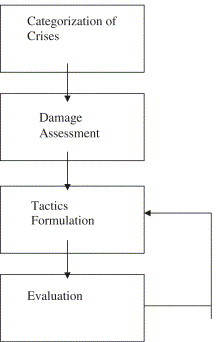

Following Stafford et al. (2002), we propose in this paper a four-step crisis management procedure to deal with crises like SARS. Fig. 1 shows the four steps in the process. Step one is categorization of crises in which restaurant managers should classify the crisis they are dealing with into one of the seven categories outlined in Table 1 below. Identification of the crisis type is important because it helps managers find the appropriate measures to keep the crisis under control. Next, the extent and type of damage is assessed, and then tactics are formulated and implemented to combat the crisis. The last step of the crisis management process is to evaluate the effectiveness of the recovery strategies using a feedback loop that enables managers to refine the tactics until the crisis is brought under control.

Fig. 1.

Crisis management procedure.

Table 1.

Seven types of crisis faced by restaurants

| Major factors | Specific environment | Type of crisis | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| External factors | Physical environment | Natural disaster | Earthquake damages a restaurant property; virus/bacteria contamination preventing patrons from visiting the restaurant |

| Technological failure | Failure of food processing system causing widespread food contamination. | ||

| Human or social environment | Confrontation | Labor strike disrupts normal operations; special-interest group boycotts restaurant | |

| Malevolence | Terrorists attack; food is poisoned through product tampering | ||

| Internal factors | Management failure | Skewed values | Restaurant sells junk food that is harmful to public health (ranking short-term profits over concern for the well being of consumers) |

| Deception | Restaurant knowingly serves spoiled or contaminated food | ||

| Misconduct | Corporate CEO charged with bribery to obtain a licence |

2. Categorization of crises

Crisis is defined as a low-probability, high-impact event that threatens the viability of the organization, and is characterized by ambiguity of cause, effect, and means of resolution, as well as by a belief that decisions must be made swiftly (Pearson and Clair, 1998). Fearn-Banks (1996) views a crisis as a major occurrence with a potentially negative outcome affecting an organization, company, or industry, as well as its publics, products, services, or good name. Pauchant and Mitroff (1992) regard a crisis as a disruption that physically affects a system as a whole and threatens its basic assumptions, its subjective sense of self, and its existential core. Barton (1993) suggests a crisis is a major, unpredictable event that has potentially negative results. In the business context, an event that damages a firm's reputation or drastically harms the long-term goals of profitability, growth or survival is called a crisis (Lerbinger, 1997).

The various crises that a business organization may encounter warrant different solutions and crisis-management methods. Using Lerbinger's (1997) typology of crisis, and following Stafford et al.'s (2002) approach of categorizing the September 11 terrorist attacks, we classify the potential crisis faced by restaurants into seven categories based on whether the crisis is caused by external factors or originate within the restaurant itself. The seven types of crisis are shown in Table 1.

The seven categories can be grouped together with respect to the environment in which each crisis arises. In the following, we would elaborate more fully on the nature of various crises in each environment, and would attempt to relate SARS to the appropriate environments.

2.1. Physical environment

As an external factor, physical environmental conditions such as natural disasters and technological failures are the least controllable by a restaurant. Restaurants can only react passively to large-scale hurricanes or other natural phenomenon. Such is the case with Hurricane Andrew in Florida, 1992, and Hurricane Hugo in South Carolina, 1989, which resulted in 26.5 billion and 7 billion dollars worth of damage, placing them as the top two costliest hurricanes in the US history (http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pastcost.shtml).

Technological failure is caused by errors in the application of science in industry. The most prominent example is that of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant explosion in 1986, resulting in many European countries destroying crops in fear of contamination.

The SARS outbreak in Hong Kong fits naturally into the physical environment category of crises. The origin of the coronavirus suspected of causing SARS is still unknown and restaurant managers are still grappling with the task of dealing with its consequences. The entire industry lost three billion dollars of revenue in the two months after the outbreak, and many restaurants were on the verge of collapse.

The appropriate strategy to deal with disasters of the physical environment type is to react quickly to minimize the damage. Time is of the essence because the damage could escalate very quickly to a point that threatens the survival of the business.

2.2. Social environment

Crises of the social environment are caused by human deeds. Strikes by labour unions and boycotts of certain goods resulting in damage to firms are examples of confrontation types of crises in a firm's social environment. Acts of malevolence are likewise crises of the social environment. These crises include terrorist acts or criminal deeds, which are also extremely disruptive to a firm's business.

The SARS instance in Hong Kong had indirectly generated crises of the social environment because many restaurants experienced liquidity problems after the outbreak, and had to lay off thousands of staff or force them to take no-pay leave. This led to some labour unrest and lawsuits.

The strategies for dealing with crises in the social environment involve calming the people and negotiation with the parties affected to achieve a win–win resolution. Legal measures may be necessary if compromise is not possible.

2.3. Management failures

The management level is of utmost importance as many crises are caused by skewed management values, deception or misconduct. Fiscal forecasts and goals that cannot be reached often lead to unethical behaviour, or even criminal acts on the part of the management. Such crises can utterly destroy the reputation of a firm, as with the recent Enron and Worldcom scandals.

Many restaurants are facing serious cash flow problems after the SARS outbreak, so there is great temptation for their managers to engage in unethical conduct to ensure the survival of their business, which may ultimately give rise to crises of the management failure type. The appropriate strategy to deal with these kinds of crises is to enforce a strict code of conduct on business practices. Very often, dismissal and legal sanction have to be resorted to for criminal behaviour.

3. The usefulness of a crisis typology on crisis management

The crisis typology we outlined in the previous section is useful to restaurant managers in two ways. First, the appropriate management and recovery strategies are dependent on the type of crisis in question (Lerbinger, 1997). For example, in the case of a crisis that belongs to the technological failure type, the possible remedial actions may include a public relations campaign to convince the public that the failed system has been adequately fixed, or a better new system is in place. The firm should also communicate to the public that it would try its best to avoid similar failures in future. Second, the typology can alert managers to subsequent crises that may follow the original one when the wrong approach has been used to deal with the original crisis. In the SARS outbreak, for example, restaurant managers’ attempt to lay off staff without proper compensation to improve their cash flow position may lead to confrontation with the labour, which may subsequently cause a crisis of the social environment type.

4. Damage assessment

Before a recovery plan is devised to rebuild the business, restaurants should assess the type and extent of damage caused by the crisis. In the SARS instance, for example, the major damage caused to a lot of restaurants was a sudden cash flow problem that was both immediate and heavy. Hence, the appropriate counter measures must aim at maintaining an adequate liquidity position for the restaurant. Operating costs must be minimized, and low cost loans must be solicited. Meanwhile, revenue enhancement plans need to be devised to generate more cash inflow to the restaurant.

5. Tactics formulation

To draw out the appropriate recovery strategies to save their business, restaurant managers must consider each process in the business operation, and find out how each step in the service management cycle could be modified and improved to bring the crisis under control. Essentially, the appropriate tactics in the SARS epidemic should include all measures that could minimize the cost and enhance the revenue of the restaurant. The strategies that restaurant managers have devised to deal with the circumstance are:

5.1. Cost reduction

During the SARS crisis, restaurant managers sought various ways to minimize their running expenses so that it had a better chance of surviving the outbreak. This goal could be accomplished via a multitude of recovery measures. One approach is to reduce investment in advertising and promotion. Another possible means of cutting costs is to reduce factor input costs, achievable through negotiation with suppliers to lower the cost of foodstuffs, with landlords to reduce rent, and with staff for pay cut or no-pay leave.

A time of crisis also warrants the step of lobbying for government financial support. The government may take notice of the plight and offer benefits such as interest-free loans or allow for a suspension of certain fees and charges. On April 18th, the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce began lobbying for government relief for SARS-affected businesses, including the catering industry. In response to the lobbying, Hong Kong's Chief Executive, Mr. Tung Chee-Hwa, announced a HKD 11.8 billion package that included tax rebates, lower rent for shops in public shopping malls and reduced water and sewage charges for restaurants.

5.2. Revenue enhancement

Simultaneous to cost reduction, restaurant managers may implement revenue enhancement strategies. To combat the pressures resulting from widespread fear of SARS, a restaurant could increase its patron's perceived value of dining there by adopting a combination of the following.

5.2.1. Change of marketing mix

The most obvious tactic is to improve food quality and service. In addition, restaurants may offer discounts or other forms of promotion to entice potential customers to dine. Capitalizing on the people's current emphasis on health and strengthening their own immunity, some restaurants offered specialized “anti-SARS” menus, with items that claim to boost customers’ immune system. Such items are often based on Chinese herbal medicine and aim to induce harmony between the yin and yang forces within the body. This approach was well received by the Hong Kong people, who already have a strong tradition of incorporating Chinese medical herbs into their diet. For customers who were nonetheless still afraid of dining out, many restaurants provided take-away or delivery services.

Several restaurants also took steps to improve their social image in order to attract customers by setting up a community fund whereby a proportion of any patronage was donated to SARS-related causes.

5.2.2. Decrease perceived physical risk

The damage to restaurants caused by SARS is largely due to panic and widespread fear as opposed to actual direct consequences of the virus. This stems from the fact that threats that cannot be seen or controlled are considered much more perilous than those that can be seen (Gregg, 2003).

Perceived physical risk is one of the six types of risks that have been extensively discussed and studied by marketing scholars like Bauer (1967) and Bettman (1973). As the SARS virus is transmitted by airborne water molecules, it is necessary to deploy a clear and effective policy that ensures the sanitation of the restaurant premises, so that the perceived risk of dining in the restaurant could be kept to the lowest possible level. To instil a sense of confidence in the patron, restaurant managers should advertise its hygiene policies and the measures the restaurant has taken to safeguard the customers’ physical health.

To make the customer feel confident, restaurants proactively took steps to sanitize the restaurant area. In fact, many restaurants used cleanliness and hygiene as a selling point in addition to food quality and cost. The following measures were adopted by local restaurants to combat the SARS epidemic:

-

•

Regardless of position, all staff were instructed to wear protective surgical masks. This policy was implemented in almost all restaurants in Hong Kong.

-

•

A ‘hygiene ambassador’ was employed to greet customers and offer antibacterial wipes. The American restaurant chain Ruby Tuesday said it regained 30% of its lost customers through this sanitation measure and offering a 50% discount. Another example is Queen's, a disco in Hong Kong that introduced Nurse Betty, an attractive waitress who checked the temperatures of customers at the door.

-

•

Many restaurants disinfected the premises several times a day and all eating utensils were kept in a sterilized compartment or immersed in hot water to eradicate the virus.

-

•

Chinese people share a meal amongst friends and family using chopsticks, which provides a channel for spreading SARS. To deal with this problem, each dish was accompanied with a “common” pair of chopsticks that everyone used to transfer food to his/her own bowl instead of using the pair for eating.

-

•

Karaoke restaurants advertized that all microphones we re cleaned by ultraviolet rays and disinfectant spray to prevent the spread of the virus.

6. Assessment of crisis management tactics

The tactics devised for fighting the crisis must be closely monitored and refined depending on their effectiveness. That is, contingency measures must remain flexible and adapt to changing conditions of the crisis. New information needs to be incorporated into the business practices of the company. For example, the implementation scale of measures such as the distribution of face masks could be modified to minimize cost after WHO decided to withdraw Hong Kong from its list of affected areas.

7. Discussion

Whilst the SARS crisis is a natural disaster, the methods employed by local restaurant managers to deal with the challenge serves as a good reference for other restaurants who may be inflicted with similar crises in future. In this outbreak, local restaurants have been adept in responding to the crisis. Through a combination of the cost reduction and revenue enhancement strategies outlined above, alongside a variety of additional measures, several restaurants have even succeeded in turning a profit under the adverse influence of the outbreak.

One important issue uncovered from the SARS outbreak is that nearly all Hong Kong restaurants do not have a crisis plan. The literature on crisis management has stressed the importance of a plan for crisis management (see, for example, Fearn-Banks, 1996; Coombs, 1999; Barton, 2001). To survive a crisis, a restaurant must have formal guidelines and procedures for communicating to employees, as well as the general public about various reactive measures a restaurant plans to undertake in the event of a crisis. A restaurant's contingency plan should not cover epidemics like SARS only, but should also look into recovery measures for all the other six types of crises we described in Table 1. In formulating a crisis management plan, a restaurant must look at its needs and goals, establish a risk management policy and communicate it to all staff. The crisis management plan should establish clear accountabilities and responsibilities for identifying, managing and monitoring risks. In the planning process, restaurant managers must trade-off the risk involved and the costs of the measures to be undertaken, and should encourage openness and participation from all staff. Finally, the plan should also incorporate a review process to enable a restaurant to learn from each crisis for more effective crisis management in future.

Finally, restaurants that prepare for a crisis should use a team approach. The use of teams is standard practice among leading corporations today (Devine et al., 1999). According to Coombs (1999), a crisis management team is a cross-functional group of people within the organization who have been designated to handle any crisis. Previous research has found that a crisis team approach has a better chance of formulating a crisis management plan that is effective (Pearson and Clair, 1998; Fink, 1986; Pearson et al., 1997).

References

- Barton L. South-Western Publishing Company; Cincinnati, OH: 1993. Crisis in Organizations: Managing and Communicating in the Heat of Chaos. [Google Scholar]

- Barton L. SouthWestern College Publishing—Thomson Learning; Cincinnati, OH: 2001. Crisis in Organizations II. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R.A. Consumer Behavior as Risk Taking. In: Cox D.F., editor. Risk Taking and Information Handling in Consumer Behavior. Harvard University Press; Boston, MA: 1967. pp. 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bettman J.R. Perceived risk and its components: a model and empirical test. Journal of Marketing Research. 1973;10:184–190. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing, and Responding. [Google Scholar]

- Devine D.J., Clayton L.D., Philips J.L., Dunford B.B., Melner S.B. Teams in organizations: prevalence, characteristics, and effectiveness. Small Group Research. 1999;30:678–711. [Google Scholar]

- Fearn-Banks K. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ: 1996. Crisis Communication: A Casebook Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Fink S. Amacom; New York: 1986. Crisis Management: Planning for the Inevitable. [Google Scholar]

- Geoffrey, A.F., Prystay, C., 2003. Restaurants, churches, taxis and bars woo SARS recluses. Wall Street Journal, 25 April.

- Gregg A.R. SARS and the fear factor. Maclean's. 2003;116:37. [Google Scholar]

- Lerbinger O. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New Jersey: 1997. The Crisis Manager: Facing Risk and Responsibility. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pauchant T.C., Mitroff I. JosseyBass Publishers; San Francisco, CA: 1992. Transforming the Crisis-prone Organization: Preventing Individual, Organizational, and Environmental Tragedies. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C.M., Misra S.K., Clair J.A., Mitroff I.I. Managing the unthinkable. Organizational Dynamics. 1997;26:51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C.M., Clair J.A. Reframing crisis management. Academy of Management Review. 1998;23:59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, G., Yu, L., Armoo, A.K., 2002. Crisis Management and Recovery. Cronell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, October, 27–40.