Highlights

-

•

This study fills a gap in global public relations research.

-

•

Presents a review of the social-mediated crisis communication (SMCC) research in China.

-

•

Discusses how Chinese social media affect dialogue between three types of organizations and their publics.

-

•

Identifies contextual factors that may facilitate/inhibit social-mediated dialogue in crises of China.

-

•

Provides a scholarly assessment tool and practical advice on SMCC in China.

Keywords: Social media, Crisis communication, Weibo, Dialogue, Mediator, China, Public relations

Abstract

The rapid diffusion of social media is ushering in a new era of crisis communication. To enhance our understanding of the social-mediated dialogue between organizations and their publics in crises of China, this study conducts a content analysis of 61 relevant journal articles published in 2006–2018. Results of this research present an overview of ongoing research trends such as theoretical frameworks and methodological preferences. This research also explores how the unique Chinese social media characteristics affect the dialogue between types of organizations and their publics. Contextual factors such as face and favor, relationship (Guanxi) and sentiment (Renqing), and the centralized political system that may facilitate/inhibit dialogue in crises of China are identified as well. Finally, this study suggests promising new directions such as a scholarly assessment tool for the social-mediated crisis communication research in China.

1. Introduction

Crises now frequently occur all over the world. In several fast-developing countries such as China, India, and Brazil, crises are appearing more often than we have expected. Especially in China, crisis information spread rapidly and influenced the whole society through social media such as Weibo (Chinese Twitter) and Youku (Chinese YouTube). Major crises, for instance, the Wenzhou online mass incident and the China’s Red Cross credibility crisis in 2011, and the Hepatitis B vaccine scandal in 2013 have triggered public emergencies significantly through social media, which served as platforms for disseminating and exchanging information widely and instantaneously (Xie, Qiao, Shao, & Chen, 2016). In the era of Web 2.0, organizations could directly apply social media to start a dialogue with the massive audience. Meantime, publics were empowered in the online open space by actively participating in crises events (Romenti, Murtarelli, & Valentini, 2014; Xie et al., 2016), instead of being passive receivers of organizational information. Therefore, social media served as an ideal avenue for fostering dialogue between organizations and their publics in crises (Kent & Taylor, 2002; Romenti et al., 2014).

The social-mediated crisis communication (SMCC), also called “social-mediated dialogue” between organizations and their publics in crises (Fearn-Banks, 2002, p. 2; cited in Cheng, 2016a) has attracted attention from worldwide scholars in the past decade (Bondes & Schucher, 2014; Cheng, Huang, & Chan, 2017; Kim, Zhang, & Zhang, 2016; Tai & Sun, 2007; Zhu, Anagondahalli, & Zhang, 2017). For example, Tai and Sun (2007) demonstrated that in the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) crisis in 2003, the online tools have empowered the public to speak out and open the conversation with official claims in China. Cheng (2016b) explored the crisis communication of the Red Cross of China on Weibo and found that factors such as strict government control of information dissemination and closed culture of a Chinese non-profit organization (NPO) might inhibit effective dialogic conversations and lead to public distrust towards Chinese charitable organizations. Zhu et al. (2017) examined how McDonald’s and KFC used social media during their 2012 crises in China and found crisis response strategies should be contextualized and based on specific cultural variations. Mou (2014) conducted a content analysis of 6,186 microblog posts on 12 food safety incidents in China and results illustrated how different types of micro-blogs gratify diversified needs of online publics.

Considering a large amount of relevant literature focusing on the social-mediated crisis communication/dialogue in public relations or in the field of communication, the purpose of this paper is to provide a synthesized review of how global scholarship examines the realm of SMCC in China and offer insights for future research agendas. Through content analysis of 61 articles in 27 journals indexed in Web of Science core collection from 2006 to 2018, this paper gives an overview of current research trends such as theoretical frameworks and methodological preferences. Meanwhile, this study explores how social media has been changing dialogue between different types of organizations and their publics and the impact of unique contextual factors (e.g., cultural elements and political regimes) on the social-mediated dialogue. Aims of this study include three main dimensions: a) to enrich the global public relations literature by reviewing the SMCC research in a Chinese context. Not only a review is provided, but also a greater picture on theory building and practical implications of SMCC in China are addressed; b) to extend the dialogue research in China by exploring online dialogue between three types of organizations and their publics in crises; c) to illustrate how sophisticated cultural and political factors affect the SMCC practice in China.

2. Literature review

2.1. Social-Mediated Crisis Communication (SMCC)

Social media, as a “double-edged sword” has brought both opportunities and challenges for crisis communication (Cheng, 2016a). On the one hand, scholars found that social media could facilitate organizations to monitor crisis issues, open up-to-date conversations with publics, cultivate critical relationships, and create transparency of organizational actions (Jin & Liu, 2010; Macias, Hilyard, & Freimuth, 2009). On the other hand, misinformation, rumors, negative opinions, and emotions were amplified on social media and crisis managers might lose control of official messages when user-generated contents emerged or even dominated the public opinion (Liu, Jin, Austin, & Janoske, 2012; Wigley & Fontenot, 2010).

To address the impact of social media on crisis communication, Liu et al. (2012) created a social-mediated crisis communication model, serving as the first theoretical framework to describe relationships between organizations, online and offline publics, social media, traditional media, and word-of-mouth communication before, during and after crises (Austin, Fraustino, Jin, & Liu, 2017). This model has been widely tested using different methods such as experiments or interviews in the context of the United States. Scholars mainly discussed 1) how crisis information form, sources, crisis type and history might influence publics’ (e.g., influential social media content creators, followers, and inactives) crisis responses; 2) how types of organizations (i.e., corporates, NPOs, and governments) may respond to publics effectively by adopting different crisis communication strategies (Liu, Jin, & Austin, 2013; Liu, Fraustino, & Jin, 2015).

Besides this SMCC model, scholars also applied four main blocks of theories to study the interplay between social media and crisis communication (Austin et al., 2017). These theories included audience and stakeholder theories (e.g., uses and gratifications theory, media dependency theory, and spiral of silence theory), form or medium influence-based theories (e.g., media richness theory), source influence-based theories (e.g., dialogic public relations theory), and content influence-based theories (e.g., framing theory, image repair theory, and situational crisis communication theory). For instance, Lev-On (2012) adopted uses and gratifications (U & G) theory to examine publics’ motivations of using social media in a natural disaster context. Cheng et al. (2019) continued to use the U & G approach and examined publics’ gratifications-sought on social media of mobile devices during an earthquake in mainland China. Taylor and Perry (2005)’s multi-case study provided recommendations for organizational crisis responses based on dialogic public relations theory.

In sum, scholars in the past years have increasingly paid attention to the SMCC research in contexts (Cheng, 2016a; Liu et al., 2015; Tai & Sun, 2007; Taylor & Perry, 2005; Zhu et al., 2017). This field also attracted updated reviews from several scholars such as Cheng (2016a), Eriksson (2018), and Rasmussen and Ihlen (2017). However, none of these studies fully examined the SMCC research in a non-Western context such as contemporary China and a review of the trends and research domains on SMCC in China is lacking. To explore this emerging field, the first research question was raised.

RQ1: What was the general trend of SMCC research in China (e.g., numbers of articles in each journal, theoretical frameworks, and methodological preferences)?

2.2. Dialogue, social media, and crisis communication

In the past decades, the concept of dialogue has emerged as an important research and professional issue in the field of public relations (Kent & Taylor, 2002; McAllister-Spooner & Taylor, 2007; Pang, Shin, Lew, & Walther, 2018; Taylor & Kent, 2014; Taylor & Perry, 2005). Pearson (1989) first considered “dialogue” as a public relations theory and he suggested that the ethical public relations practice was to have a dialogic system with publics. To outline a dialogic public relations theory, Kent and Taylor (2002) traced the roots of dialogue from interdisciplinary areas and defined dialogue as “an orientation that valued sharing and mutual understanding” (Taylor & Kent, 2014, p. 388). They defined dialogic communication as “any negotiated exchange of ideas and opinions” (Kent & Taylor, 1998, p. 325). To extend the conceptualization of dialogue in crisis communication, Romenti et al. (2014) reviewed organizational development and management literature (Innes, 2004; Shotter, 2008) and they found that dialogue might not require mutuality or openness as public relations literature assumed. Instead, dialogue served strategic communication purposes, and organizations and their publics could adopt a dialogic approach for any single or two-way communicative interactions in crises (Romenti et al., 2014).

Studies also found that social-mediated dialogue might play a critical role in building and maintaining organization-public relationships (Pang et al., 2018; Yang, 2018) and social media contained different functions in crisis communication. For instance, Liu and Kim (2011) found that social media could provide emotional support during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Muralidharan, Dillistone, and Shin (2011) demonstrated the use of social media interacting with publics and disseminating organizational information in the Haiti earthquake. Cheng, Jin, Hung-Baesecke, and Chen (2018) also supported the important role of social media tools in corporate social responsibility engagement in a natural disaster. This review study focuses on social-mediated dialogue in crises and specifically any exchange of ideas or opinions between organizations and their online publics in China.

2.3. Chinese social media in crisis communication

According to Cheng and Cameron (2017), social media as one of the fast-growing areas has significantly influenced crisis communication research in the U.S. In the mainland Chinese society, Huang, Wu, and Cheng’s (2016) study supported the impact of digital transformation in crises. Contrasting with the social media system in Western countries such as the United States, the Chinese new media landscape contained a large number of highly engaged users. For instance, one of China’s most popular social network, Sina Weibo has over 411 million monthly active users in the first quarter of 2018 (China Internet Watch, 2018), while Twitter only has 336 million users globally (Statista, 2018). Experimental research also disclosed that this large crowd of social media users in China could generate more online negative crisis-reaction intentions such as boycotting companies and writing negative comments than those in the U.S. (Chen & Bryan, 2017).

According to Tong and Lei (2013), Chinese social media also functions more dialogically than those tools in the rest of the world. WeChat in China, for example, integrates features from Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp, targeting 1.5 billion Chinese users who averagely spend 3 h a day on their smartphones (People’s Daily, 2017). WeChat not only performs as a tool for personal and social communication, but also functions in crisis communication by offering updated news and geo-localized services, collecting donations, and facilitating direct money transfers. On Weibo, a post with 140 characters in Chinese can express more meanings than a tweet in English. Compared to Twitter, Weibo contains several unique features such as threaded comments, verified accounts, trends categorization and Weibo events, and the medal reward system and hall of celebrity (Chen & Bryan, 2017).

Furthermore, research shows the live broadcasting function of social media in China has dramatized crises in China. Domestic social media features such as rich media and virtual red envelopes have motivated a huge online crowd to watch, cyber-manhunt, comment, and edit media content (Goode, 2009). In crises, Luo and Jiang (2012) found that Chinese online users were driven by rumors online and had a tendency to follow the crowd. This study thus posited the second research question to explore the types of social media commonly discussed in current SMCC research. Most importantly, RQ2 intended to explore how social media was changing the dialogue in crises of China.

RQ2: What were the types of social media discussed in current SMCC research and how did these tools influence dialogue between types of organizations and their publics?

2.4. Contextual factors, crisis communication, and dialogue

Different from Western contexts, which value low-power distance, the need for equality, and democracy, Chinese cultures emphasize high-power distance, group harmony, and authoritarianism (Hofstede, 2001; Wong, Wei, Wang, & Tjosvold, 2017). Power distance, as an important contextual factor measures inequality across culture and affects the relational dialogue between organizations and their publics in crises (Mathew & Taylor, 2018; Sriramesh & Vercic, 2011; Taylor, 2000). For instance, practitioners’ selection of communication models were different depending on levels of power distance in a society (Sriramesh & Vercic, 2011). In a low-power distance culture, which “better supports the multilevel distribution of data, information, and certain types of knowledge” (Leonard, Van Scotter, & Pakdil, 2009, p. 855), organizations preferred to apply a dialogic communication process with their publics in crises. In contrast, the high-power distance existed in Chinese societies and effectively influenced the crisis communication strategies and public responses in crises (Huang et al., 2016; Hwang, 1987). Organizations such as governments in a high-power distance nation were perceived to be very powerful and they avoided using extreme strategies and preferred passive crisis communicative strategies (Huang et al., 2016). Powerless individuals expecting an equal distribution of power might distrust organizations and reacted more strongly in crises than those in low-power distance nations. (Taylor, 2000).

Meanwhile, several other contextual factors such as face-saving/giving, favor-seeking/giving, relationship (Guanxi) and sentiment (Renqing), and the centralized political system may also challenge the Western-dominated crisis communication practice and characterize a distinctive dialogue between organizations and publics on social media in crises (Cheng et al., 2017; Jiang, 2014). Rooted in Confucianism, the Chinese culture emphasized face (Mienzi), favor (enhui), relationship (Guanxi), and sentiment (Renqing). In crisis communication, Chinese organizations frequently adopted face-saving strategies since losing face means losing prestige, reputation or honor (Huang et al., 2016). Meanwhile, organizations and publics in China exchanged face and favor in the processes of social exchanges and resource distributions (Hwang, 1987). Giving face and favor to others could help establish and reinforce relationships between each other (Ting-Toomey, 2005). To build an effective dialogue, relationship and sentiment also served as key cultural factors. In China, creating a long-term and strong relationship is the precondition of opening conversations, developing cooperative goals, and reaching commited relationships (Wong et al., 2017). Defined as “the emotional responses of an individual confronting the various situations of daily life” (Hwang, 1987, p. 953), public sentiment, rather than regulations and rules, may become the top priority that organizations should take care of in crises of China.

Besides the above-mentioned cultural elements, the political regime in mainland China is also significantly different from those in Western countries such as the U.S. (Chou, 2009). The dominance of political power over social power is manifest very well when the central government strictly controls information dissemination in any types of social-mediated crises in China (Cheng et al., 2017). Scholars found that the ubiquitous control of the central government and strict media censorship have significantly influenced the communication pattern and dialogue building between organizations and their publics (Huang et al., 2016). Thus, this study proposed RQ3 to explore the contextual influence on the social-mediated dialogue in crises of China.

RQ3: How did contextual characteristics influence the social-mediated dialogue in crises of China?

3. Method

3.1. Data collection

To answer the above-mentioned research questions, a keyword screening method was applied to filter related articles written in English in the Web of Science core collection, which included over 20,000 worldwide scholarly journals in over 250 science, social sciences, and humanities disciplines (Clarivate Analytics, 2018). Articles with the following keywords in the topic section were selected for review: any of “online,” “Internet,” “social media,” “new media,” “blog,” “micro-blog,” “WeChat”, “Weibo”, “video,” “Web,” “social network service,” or “SNS,” and any of “crisis” or “crises” or “incident”, and any of “China” or Chinese”.

Meanwhile, 27 representative journals in the field of communication were used for screening. Specifically, six top-tier journals on new media technologies in communication (e.g., Information Communication & Society,New Media & Society, and Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking), seven journals relevant to public relations/crisis communication (e.g., Journal of Public Relations Research, Public Relations Review, andJournal of Contingencies and Crisis Management), seven top-ranked general communication journals (e.g., Journal of Communication and Communication Research), and seven journals in regions (e.g., Asian Journal of Communication and Chinese Journal of Communication) were selected. Finally, 61 articles from the 27 journals exclusively focusing on the SMCC research in China were collected for data analysis.

3.2. Measures and inter-coder reliability

Previous review studies focusing on new media, crisis communication, and public relations provided a framework of analysis for this study (Huang et al., 2016; Ye & Ki, 2012). Coding categories included four dimensions: 1) general information, including the name of the journal, publication year, names and locality of authors; 2) research focus (organization, media or publics), types of organizations (corporations, governmental institutions, and NPOs), theoretical frameworks (the spiral of silence theory, U & G theory etc.), and methodological preferences (survey, experiment etc.) 3) social media types (Weibo, blogs etc.); 4) crisis types (natural crisis, crisis of malevolence, confrontation crisis etc.) and occurred time.

To test inter-coder reliability, two well-trained coders analyzed 15 randomly selected articles, representing 25% of the 61 articles. Using Scott’s pi, the inter-coder agreement was 1.0 for the general information (i.e., the name of each journal, publication year, and authorship), 1.0 for social media types, 0.93 for research focus and organizational types, 0.90 for theoretical frameworks, 0.95 for methodological preferences, and 0.95 for crisis types and occurred time. The overall inter-coder agreement was 0.96.

4. Findings

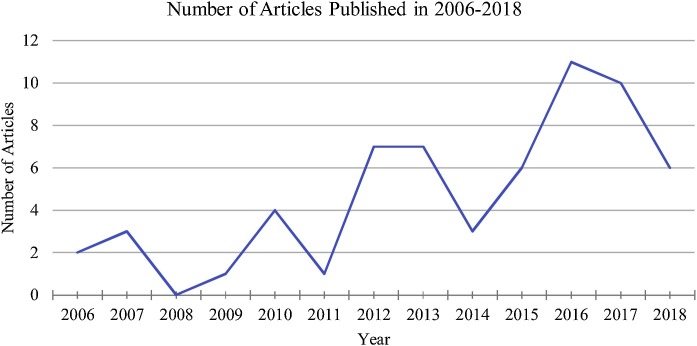

RQ1 investigated the trends in current SMCC research including general information of articles, theoretical frameworks, methodological preferences, and crisis types and occurred time. Fig. 1 demonstrated increasing attention to the SMCC research in China in the past decade, with 10 articles (16%) published between 2006 and 2010; 18 articles (30%) published between 2011 and 2014, and 33 articles (54%) published from 2015 to July 2018.

Fig. 1.

The Number of Articles on the Social-Mediated Crisis Communication from 2006 to 2018.

Among the 61 articles, the majority (n = 25, 41%) appeared in public relations or crisis communication-focused journals. Public Relations Review was the leading public relations journal, serving as the major outlet (21%) for the SMCC research in China. Seventeen articles (28%) were from journals focusing on communication research in regions such as Asian Journal of Communication. Eleven articles (18%) were found in the six technology-focused journals and eight articles (13%) were published in the seven top-ranked communication journals such as Journal of Communication. All the published research was led by scholars from global institutions: 29 first-authors were from Greater China (i.e., mainland China, Taiwan, Macau, or Hong Kong), 24 from the United States, 2 from Australia, 2 from England, 2 from Singapore, 1 from Japan, and 1 from Germany.

In terms of theoretical frameworks, approximately half of the articles (30 out of 61) applied theoretical frameworks. As shown in Table 1 , scholars mostly applied content influence-based theories, including image repair theory (12%), situational crisis communication theory (8%), and framing theory (8%). Meanwhile, audience and stakeholder theories (e.g., U & G theory, media dependency theory, and spiral of silence theory) were also frequently adopted (13%), followed by the social-mediated crisis communication model (3%), and other theories (5%).

Table 1.

Theoretical Frameworks and Methodological Preferences.

| Theory/Methods | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical framework | ||

| Image repair theory | 7 | 12 |

| Situational crisis communication theory | 5 | 8 |

| Framing theory | 5 | 8 |

| Uses and gratifications theory | 3 | 5 |

| Media dependency theory | 3 | 5 |

| Spiral of silence theory | 2 | 3 |

| Social-mediated crisis communication model | 2 | 3 |

| Other theories | 3 | 5 |

| No theories applied | 31 | 51 |

| Total | 61 | 100 |

| Research Methods | ||

| Quantitative methods | ||

| Survey | 6 | 10 |

| Content analysis | 14 | 23 |

| Experiment | 2 | 3 |

| Qualitative methods | ||

| Case study | 15 | 25 |

| Interview/focus group | 3 | 5 |

| Literature review | 2 | 3 |

| Discourse analysis | 7 | 11 |

| Quantitative and qualitative mixed | 12 | 20 |

| Total | 61 | 100 |

Regarding methodology, results indicated that quantitative methods included content analysis (n = 14, 23%), survey (n = 6, 10%), and experiment (n = 2, 3%). Qualitative methods included case study (n = 15, 25%), interview (n = 3, 5%), and other methods such as literature review and discourse analysis (n = 9, 14%). Overall, we found that qualitative methods (44%) were more frequently employed than quantitative methods (36%). Mixed methods were also common (n = 12, 20%).

RQ1 also examined types of crises studied in current SMCC research in China. Fifty-four articles (89%) have mentioned specific crises. The most frequently examined crises were managerial misconducts (n = 25, 41%), followed by natural disasters (n = 9, 15%), confrontation crises (n = 8, 13%), malevolence (n = 3, 5%), and technological crises (n = 1, 2%). Other eight crises (13%) included the financial crisis and celebrity scandal etc. These crises occurred between 2003 and 2014, covering major crises in contemporary Chinese society: 2003 SARS crisis, 2011 Red Cross credibility crisis, 2012 Diaoyu/Senkaku crisis, 2013 vaccination scandal, and food safety crises such as 2014 McDonald's food crisis.

RQ2 inquired into types of social media examined in current research. Data from Table 2 demonstrated that the majority of articles examined Weibo (n = 20, 33%), followed by Blogs/Forum (n = 7, 11%), online news apps (n = 13, 21%), and social media in general (n = 15, 25%). Six articles (10%) examined multiple types of social media such as Tencent QQ, Taobao blog, and Tianya forum. Regarding the impact of social media on dialogue in crises of China, this paper demonstrated results from perspectives of three main organizations (i.e., governments, corporates, and NPOs) and their publics.

Table 2.

Types of Crises and Chinese Social Media Studied in the SMCC Research.

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Crises | ||

| Managerial misconducts | 25 | 41 |

| Natural disasters | 9 | 15 |

| Confrontation crises | 8 | 13 |

| Technological crises | 1 | 2 |

| Crises of malevolence | 3 | 5 |

| Other crises | 8 | 13 |

| Crises in general | 7 | 11 |

| Total | 61 | 100 |

| Social Media | ||

| 20 | 33 | |

| Blogs/Forum | 7 | 11 |

| Online news apps | 13 | 21 |

| Social media in general | 15 | 25 |

| Multiple types of social media | 6 | 10 |

| Total | 61 | 100 |

4.1. Governmental institutions

Serving as the principal actor in dialogue, governments become the research focus among nine articles (15%). Scholars found that the Chinese central government has absolute power to interfere with other actors in a crisis event (Cheng, 2016b; Lyu, 2012). For instance, in the Xinjiang riot crisis, Chen (2012) found that the Chinese government maintained a highly controlled, reserved, and less direct conversation with publics. In addition, in the first 8 h of the Wenzhou train collision crisis, the Chinese government closed the dialogue by abandoning the rescue process and trying to bury the collided train under soil (Bondes & Schucher, 2014).

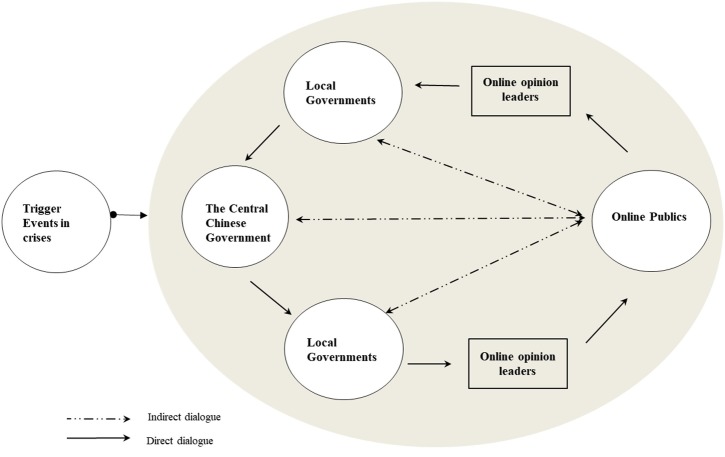

On social media, however, Chinese governmental institutions in recent years retained a certain level of openness by setting up an “online supervisory system” (Chen, Liu, & Deng, 2018). Instead of completely “controlling” dialogue with publics, the Chinese government was “guiding” dialogue to maintain a positive public image in crises (Xie et al., 2016). As shown in Fig. 2 , the central government first posted messages on its official website and linked to local governments’ social media accounts. Then local governments applied these messages as main sources for crisis communication. Second, serving as inspectors, local opinion leaders were hired to transmit crisis information and they were authorized to scan user-generated contents as well. These online opinoin leaders reported publics’ feedback following local governments’ directions (Chen et al., 2018) and meanwhile responded to online publics’ requests or inquiries. Scholars also found that the dialogue between local opinion leaders and their online followers was more direct and efficient than the top-down dialogue between governments and publics in crises of China (Tong & Lei, 2013).

Fig. 2.

The Government-Public Dialogue on Social Media of China.

Studies also indicated that governments allowed social media users to post opinions directly and even shared negative comments on governments during a certain period of politically sensitive events (Cairns & Carlson, 2016; Cheng, 2016b). Chinese governments began to open dialogue with online publics in strategic decision-making processes and thus several public emergency events were solved through online petitions (Xie et al., 2016).

4.2. Corporations

Scholars increasingly focused on corporations in previous years, publishing 13 articles in total (21%). Different from governments as leaders in dialogue with publics, Chinese private firms such as Taobao (China’s version of Amazon) had to avoid any conflicts and open dialogue with governments for possible future cooperation (Na, 2017). However, when facing publics, these firms guided dialogue through using strategies such as framing, denying, or even covering up the truth (Kim et al., 2016; Veil & Yang, 2012) in crises. Online publics correspondingly were found to dislike a denial of responsibility in dialogue and their negative sentiments easily triggered secondary crises in the dialogue with corporates (Luo & Zhai, 2017).

Meanwhile, due to Weibo’s rapid circulation of information, crises evolved from the breakout to regression stage at a faster pace than through other social media channels. Liu, Yu, and Wang (2016) argued that the cycle of public talking about crisis issues would not be longer than five days if no new topics plugged in. In both Baidu and Ctrip cases in 2016, since the corporates did not respond to critics immediately, public opinion was guided under the direction defined by social media (Liu et al., 2016).

4.3. NPOs

Only three articles (Cheng, 2016b; Cheng et al., 2017; Long, 2016) addressed NPOs’ crisis communication with their publics. Within limited literature, Cheng (2016a) examined responses of the Red Cross of China in a credibility crisis. Results demonstrated that this NPO adopted an accommodative communication strategy to open dialogue with angry donors on social media during the crisis, but finally shirked responsibility and shifted the blame onto others. Although many donors lost their trust toward the Chinese charitable system and refused to donate again, the Red Cross of China insisted on conducting a closed dialogue and did not disclose any donation information to the general public.

4.4. Online publics

A majority of current research (24 articles, 39%) examined publics and a significant increasing trend towards online stakeholders was found from 2006 to 2018. Scholars discussed antecedents that motivated publics to engage in dialogue on social media in crises, including a low-level of trust toward governments and traditional media, gratifications-sought from social media, and the increased-level of civic awareness and media literacy (Mou, 2014; Xie et al., 2016). Results also showed that Chinese online publics are highly dependent on social media and a growing number of users have used social media to express and share opinions during public emergency events (Xie et al., 2016). During the Sichuan earthquake, for example, grass-roots activists began to build up mutual trust, pave the way for more regular and extensive dialogue between online and offline activism (Lu, 2018). In the “occupy central” social movement, large quantities of online publics also expressed their extreme voices through proactive dialogue with authorities (Luo & Zhai, 2017). Finally yet importantly, the Chinese social-mediated dialogue consists of many nonverbal languages such as emoticons and figurative language. Scholars such as Kim et al. (2016) found that when Alibaba, China’s largest e-commerce companyadopted an informal personable communication style in dialogue with their online publics in China, the communication outcomes were positive in terms of consumer sentiments.

RQ3 explored how contextual characteristics in China affected the social-mediated dialogue in crises. Results identified several major contextual factors, which included high-power distance, face-saving/giving, favor-seeking/giving, relationship (Guanxi) and sentiment (Renqing), and the centralized political system.

4.5. High-power distance

This cultural trait significantly influenced the government-public dialogue in crises. For instance, (Hong, 2007) found that in the SARS crisis, instead of sending updated information to the publics, local officials concealed the real number of infectors until receiving upper-level orders from the central government. The high-power distance prevented the occurrence of true dialogue and could easily trigger publics’ high-level of distrust toward organizations when people felt disempowered and helpless during crises (Cheng, 2016b).

4.6. Face-saving/giving

Due to the traditions of Chinese culture, another factor that influences social-mediated dialogue in crises is face-saving/giving. Private corporations in China have developed a unique dialogic pattern with governments by giving the face to governments and saving face for themselves. For instance, Na (2017) found that the corporate blogger Taobao has never directly threatened the face of governmental officials in crisis responses. Instead, the blogger rhetorically passed the buck to a third party as the scapegoat. Veil and Yang (2012) also found that in the Sanlu milk contamination crisis, the value of “face-saving” led to a totally closed dialogue between the state-owned corporate and its publics. The accused firm in crises chose to cover up the truth and manipulated media coverage since “the ugly things in the family shall not go public” (Veil & Yang, 2012). Thus, in the Chinese context, face-saving/giving resulted in a closed and unethical dialogue between corporations and their online publics.

4.7. Favor-seeking/giving

In the social-mediated dialogue, both organizations and publics valued “favor” in their relationships. For instance, Mou and Lin (2017) found that individuals build online social networks and engage in dialogue with others since they expect resources for favor-seeking/giving between each other. To engage in a relationship, Chinese social media users categorize their virtual community members and choose to open dialogue with connections following a favor-seeking or giving tradition.

4.8. Relationship and sentiment

Results showed that cultural traits such as relationship and sentiment have significantly influenced the social-mediated dialogue in crises. On the one hand, Chinese people heavily relied on relationships and their online dialogue with others was to enhance interpersonal relationships in a collectivist culture (Zheng, Liu, & Davison, 2018). Relationship has become the basis for maintaining a dialogue in Chinese society (Yang & Jiang, 2015). On the other hand, sentiment is the top priority in crisis communication of China. Yang and Jiang (2015) identified the hierarchical sequence of sentiment, reason, and law and they found that totally relying on the law was ineffective or even useless in handling a crisis in China. Instead, sentiment (Renqing) should be specially taken care of during crises. For instance, the chief executive officer (CEO) of Vanke, the largest property firm in mainland China, stated that he would donate two million RMB (around 300,000 US dollars) in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. However, online publics attacked his blog post since this CEO ignored the sentimental feelings of victims in the natural crisis (Yang & Jiang, 2015).

4.9. Centralized political system

Scholars (Bondes & Schucher, 2014; Cairns & Carlson, 2016; Cheng, 2016b) found that the organization-public dialogue was strictly controlled by the centralized political system in China. In crises, sensitive words and social media accounts were blocked; nonverbal languages such as emoticons and figurative language were strictly filtered out; private-personal data could be easily collected by governmental institutions. Between governments and corporations, the political control restricted “all the argumentative moves of a corporate weblog” (Na, 2017, p. 344). Even if publics stayed in their daily conversations on social media, the political system could monitor users’ online dialogue and detect any negative comments on governments. Thus, the centralized political governance in China impedes a transparent, equal, and open dialogue between the above-mentioned three types of organizations and their online publics in crises.

5. Discussion and conclusion

By reviewing 61 articles published in 27 academic journals, this study presented an overview of current SMCC research in China from 2006 to 2018. Results demonstrated that increasing academic attention focused on online publics. Scholars widely discussed public motives of using social media, highly engaged online communication, and public emotions and non-verbal language use in online dialogue (Kim et al., 2016; Mou, 2014; Tai & Sun, 2007; Xie et al., 2016). Findings also demonstrated the two sides of social media’s impact on dialogue between organizations and their publics in crises of China. On the one hand, social media may act as a mediator for rapid information transmission and promote transparent dialogue in crises. Chinese social media helps balance the organizational power as the “dominator” and the public power as the “challenger” in crises. On the other hand, social media serves as an open-platform to all types of users, so it is hard to control information due to the highly engaged dialogic interactions. Messages online have the power of directing public opinion and can cause damage to an organization’s reputation. Last but not least, the unique contextual factors such as power distance, face-giving/saving, favor, relationship (Guanxi) and sentiment (Renqing), and the centralized political system that may facilitate/inhibit dialogue in crises of China were identified. Implications and directions for future SMCC research were presented below.

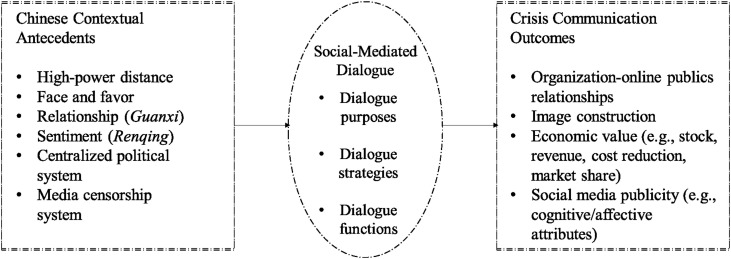

5.1. Theorizing the social-mediated dialogue in crises

Within the current literature, scholars extensively discussed the social-mediated crisis communication between three types of organizations and their publics in China. However, results found only half of current SMCC studies applied a theoretical framework. Meanwhile, theories such as the social-mediated crisis communication model, form/medium influence-based theories (e.g., media richness theory), and source influence-based theories (e.g., dialogic public relations theory) were not frequently applied. Moreover, a theoretical framework that explains the antecedents, process, and outcomes of dialogue on social media in crises of China is lacking. This study consequently posits a theoretical framework of the SMCC research in China, which confirms the importance of Chinese contextual elements and may help crisis managers to consider dialogue as an alternative communication approach for crisis responses. As shown in Fig. 3 , this scholarly assessment tool first lists major contextual antecedents that can significantly influence social-mediated dialogue in crises of China, which include high-power distance, face and favor, relationship (Guanxi), sentiment (Renqing), the centralized political system, and media censorship system. Second, as what Romenti et al. (2014) suggested, dialogue fulfilled the strategic goals of organizations. Dialogue orientations and approaches determined types of dialogue strategies, serving for different purposes and functions in crisis communication. This new framework thus argues that purposes, strategies, and functions of social-mediated dialogue should be examined in the future. Last but not least, this assessment tool contains measurements of SMCC outcomes such as organization-online publics relationships, image construction, economic value (e.g., stock, revenue, cost reduction, market share), and social media publicity (e.g., cognitive or affective attributes). Future research may test the antecedents, processes, and outcomes of social-mediated dialogue in crises of China based on this scholarly assessment tool.

Fig. 3.

A Scholarly Assessment Tool for the Social-Mediated Dialogue in Crises of China.

5.2. Extending research on secondary crisis communication

As social media has become increasingly important and powerful in facilitating publics to express their own opinions, scholars showed a keen interest in secondary crisis communication (SCC), which was defined as “the public disseminate crisis information and post negative comments about firms in crisis” (Schultz, Utz, & Goritz, 2011; cited in Zheng et al., 2018, p. 56). For instance, Noguti, Lee, and Dwivedi (2016) found the unique feature of SCC is the capacity for large quantities of information transmitted rapidly on social media (Noguti et al., 2016). Moreover, SCC not only spread crises events, but also led to new crises (Luo & Zhai, 2017). SCC has magnified the consequences of crises and certain publics’ posts in a celebrity-endorsement crisis even generated more “likes” than organizational crisis responses (Jiang, Huang, Wu, Choy, & Lin, 2015). Currently limited research focused on the effects of SCC and stakeholders’ crisis communication strategies, while in crises of China the public-generated dialogues had a high degree of diffusivity and interaction. The highly active publics and their crisis responses strategies on social media deserve exploration. This study calls for more future studies on secondary crisis communication in China.

5.3. Exploring NPOs’ crisis communication in Greater China

Results presented that large quantities of current studies focused on stakeholders/publics, governments, or corporates, rather than NPOs. In China, two main types of NPOs exist: one is initiated and sponsored by governments; the other is organized and financially supported by private citizens or institutions (Cheng, 2016b). Future research agenda may focus on the social-mediated crisis communication from perspectives of NPOs and provide theoretical and practical suggestions to increase organizational transparency and accountability in crises.

Meanwhile, dominant studies focused on mainland China and little attention was paid to Greater China, which included Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Although Hong Kong and Macau for instance, have returned to the territory of China, local residents may still hold a different political stand and stay out of the strict control of mainland Chinese governments (Huang et al., 2016); people there can easily get access to Facebook and Twitter, which are entirely blocked in mainland China. The Hong Kong government currently is facing the crisis of mistrust from publics in the post-handover period (Luo & Zhai, 2017). In Taiwan, the relatively mature democratic policies may lead to a different adoption of dialogue strategies in crises. Thus, future research can thoroughly explore each specific region and compare the social media and crisis communication practice in Greater China.

5.4. Lessons/advice for practitioners

According to Eriksson (2018), a good systematic review should not only describe directions for theory development and research topics, but also provide implications for practitioners. This review research filled the gap of global public relations literature by presenting lessons for practitioners who are interested in the social media and crisis communication practice in China. First, in China, emoticons and figurative language were popular on various domestic social media tools. Results suggested that it is important for organizations to adopt an informal personable communication style in dialogue with online publics in crises. Second, the appearance of social media such as Weibo and WeChat makes timing an essential factor in crisis communication. Thus, organizations need to change their dialogic approaches from being passive to being active and open true dialogue on China's social media sites for crisis communication. It is also essential to grasp publics’ sentimental feelings at the outset of dialogue and regularly monitor items such as customer satisfaction and word-of-mouth on popular social media platforms (Kim et al., 2016). Finally, as results from this study demonstrated, organizations should particularly understand the cultural norms and societal forces of China, if their strategic goal is to establish and maintain a positive relationship with publics in such a challenging marketplace.

Limitation and future directions

Several limitations must be mentioned. First, this study did not explore articles written in Chinese from local Chinese scholars, future research might conduct a complete review and compare findings between the international and local scholarship on the subject of social-mediated dialogue in crises. Second, to explore the stand-alone empirical research, this study only reviewed journal articles and excluded book reviews, commentaries, and conference proceedings. With the rapidly growing productivity in the SMCC research, many journal articles, books, and conference papers from interdisciplinary areas such as business, psychology, and public policy could also provide rich references on this topic. Future research may include those resources into discussions.

Acknowledgement

None.

Biography

Yang Cheng is an Assistant Professor at North Carolina State University, Raleigh, USA. She teaches quantitative research methods, strategic communication, the introduction of public relations, and crisis communication. Her research interests include public relations, social media and crisis communication, and artificial intelligence in the business context. Some of her publications have appeared in top journals such as the New media & Society, American Behavioral Scientist, International Journal of Communication, Public Relations Review, and Asian Journal of Communication. She has also received many awards and honors from global institutions such as the Institute of Public Relations and PRIME research, and has acted as the principal investigator in many grants including the Arthur Page Johnson Legacy Scholar Grant.

References

- Austin L., Fraustino J.D., Jin Y., Liu F. Crisis communication in a changing media environment: A review of the theoretical landscape in crisis communication and research gaps. In: Austin L., Jin &Y., editors. Social media and crisis communication. Routledge; New York, NY: 2017. pp. 423–448. [Google Scholar]

- Bondes M., Schucher G. Derailed emotions: The transformation of claims and targets during Wenzhou online incident. Information, Communication and Society. 2014;17(1):45–65. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.853819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns C., Carlson A. Real-world islands in a social media sea: Nationalism and censorship on Weibo during the 2012 Diaoyu/Senkaku Crisis. The China Quarterly. 2016;225:23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen N. Beijing’s Political crisis communication: An analysis of Chinese government communication in the 2009 Xinjiang riot. Journal of Contemporary China. 2012;21(75):461–479. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.-F., Bryan H.R. Examining public responses to social media crisis communication strategies in the United States and China. In: Austin L., Jin Y., editors. Social media and crisis communication. Routledge; New York, NY: 2017. pp. 114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Liu Y.P., Deng S.L. The factors that influence the communication effectiveness of Government affairs microblog. Information Science. 2018;36(1):91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y. How social media is changing crisis communication strategies: Evidence from the updated literature. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2016;26(1):58–68. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y. Social media keep buzzing! A test of contingency theory in China’s Red Cross credibility crisis. International Journal of Communication. 2016;10 [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Cameron G. The status of social mediated crisis communication (SMCC) research: An analysis of published articles in 2002-2014. In: Austin L., Jin Y., editors. Social media and crisis communication. Routledge; New York, NY: 2017. pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y., Chen, Y. R., Hung-Baesecke, R., and Jin, Y., 2019, When CSR meets mobile SNA users in mainland China: An examination of gratifications sought, CSR motives, and relational outcomes in natural disasters. International Journal of Communication 13, 319-341.

- Cheng Y., Jin Y., Hung-Baesecke R., Chen Y.R. Mobile corporate social responsibility (mCSR): Examining publics’ responses to CSR-based initiatives in natural disasters. International Journal of Strategic Communication 13(1) 2019, 76-93 doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2018.1524382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Huang Y.H., Chan C.M. Public relations, media coverage, and public opinion in contemporary China: Testing agenda building theory in a social mediated crisis. Telematics and Informatics. 2017;34(3):765–773. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- China Internet Watch . 2018. Weibo monthly active users reached 411M, 93% from mobile in Q1 2018.https://www.chinainternetwatch.com/24501/weibo-q1-2018/ Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Chou B.K.P. Routledge; New York, NY: 2009. Government and policy-making reform in China: The implications of governing capacity (comparative development and policy in Asia) [Google Scholar]

- Clarivate Analytics . 2018. Web of science platform: Web of science core collection.https://clarivate.libguides.com/webofscienceplatform/woscc Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M. Lessons for crisis communication on social media: A systematic review of what research tells the practice. International Journal of Strategic Communication. 2018;12(5):526–551. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2018.1510405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fearn-Banks K. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. Crisis communications: A casebook approach. [Google Scholar]

- Goode L. Social news, citizen journalism and democracy. New Media & Society. 2009;11(8):1287–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. 2nd ed. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 2001. Culture’s consequences: International differences in work- related values. [Google Scholar]

- Hong T. Information control in time of crisis: the framing of SARS in China-based newspapers and Internet sources. Cyberpsychology & behavior. 2007;10(5):696–699. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.H., Wu F., Cheng Y. Crisis communication in context: Some aspects of cultural influence underpinning Chinese PR practice. Public Relations Review. 2016;42(1):201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang K. Face and favor. The Chinese power game. The American Journal of Sociology. 1987;92(4):944–974. [Google Scholar]

- Innes J. Consensus building: Clarifications for the critics. Planned Theory. 2004;3(1):5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M. The business and politics of search engines: A comparative study of Baidu and Google’s search results of Internet events in China. New Media & Society. 2014;16(2):212–233. doi: 10.1177/1461444813481196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Huang Y.-H., Wu F., Choy H.-Y., Lin D. At the crossroads of inclusion and distance: Organizational crisis communication during celebrity-endorsement crises in China. Public Relations Review. 2015;41(1):50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Liu B.F. The blog-mediated crisis communication model: Recommendations for responding to influential external blogs. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2010;22(4):429–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kent M.L., Taylor M. Building dialogic relationships through the World Wide Web. Public Relations Review. 1998;24:321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kent M.L., Taylor M. Toward a dialogic theory of public relations. Public Relations Review. 2002;28:21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Zhang X.A., Zhang B.W. Self-mocking crisis strategy on social media: Focusing on Alibaba chairman Jack Ma in China. Public Relation Review. 2016;42(5):903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K.M., Van Scotter J.R., Pakdil F. Culture and communication cultural variations and media effectiveness. Administration & Society. 2009;41(7):850–877. doi: 10.1177/0095399709344054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lev-On A. Communication, community, crisis: Mapping uses and gratifications in the contemporary media environment. New Media & Society. 2012;14:98–116. doi: 10.1177/1461444811410401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.F., Kim S. How organizations framed the 2009 H1N1 pandemic via social and traditional media: Implications for US health communicators. Public Relations Review. 2011;37(3):233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.F., Fraustino J.D., Jin Y. How disaster information form, source, type, and prior disaster exposure affect public outcomes: Jumping on the social media bandwagon? Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2015;43(1):44–65. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2014.982685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.F., Jin Y., Austin L.L. The tendency to tell: Understanding publics’ communicative responses to crisis information form and source. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2013;25(1):51–67. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2013.739101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.F., Jin Y., Austin L.L., Janoske M. The social-mediated crisis communication model: Guidelines for effective crisis management in a changing media landscape. In: Duhe S.C., editor. New media and public relations. 2nd ed. Peter Lang.; New York: 2012. pp. 257–266. [Google Scholar]

- Liu K.J., Yu X., Wang D. Crisis communication trends and influencing factors in “double micro era”: Using the examples of the Baidu and Ctrip cases in 2016. Journal of Social Sciences. 2016;8:23–34. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.0257-5833.2016.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long Z.Y. Managing legitimacy crisis for state-owned non-profit organization: A case study of the Red Cross Society of China. Public Relations Review. 2016;42:372–374. [Google Scholar]

- Lu X. Online communication behavior at the onset of a catastrophe: An exploratory study of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. Natural Hazards. 2018;91:785–802. doi: 10.1007/s11069-017-3155-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Jiang H. A dialogue with social media expert: Measurement and challenges of social media user in Chinese public relations practice. Global Media Journal-Canadian Edition. 2012;5(2):57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Q., Zhai X. “I will never go to Hong Kong again!” How the secondary crisis communication of “Occupy Central” on Weibo shifted to a tourism boycott. Tourism Management. 2017;62:159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu J.C. How young Chinese depend on the media during public health crises? A comparative perspective. Public Relations Review. 2012;38(5):799–806. [Google Scholar]

- Macias W., Hilyard K., Freimuth V. Blog functions as risk and crisis communication during Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2009;15(1):1–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01490.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew S., Taylor G. Power distance in India: Paternalism, religion and caste: Some issues surrounding the implementation of lean production techniques. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management. 2018 doi: 10.1108/CCSM-02-2018-0035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister-Spooner S.M., Taylor M. Community college Web sites as tools for fostering dialogue. Public Relations Review. 2007;33:230–232. [Google Scholar]

- Mou Y. What can microblog exchanges tell us about food safety crises in China? Chinese Journal of Communication. 2014;7(3):319–334. doi: 10.1080/17544750.2014.926952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mou Y., Lin A.C. The impact of online social capital on social trust and risk perception. Asian Journal of Communication. 2017;27(6):563–581. doi: 10.1080/01292986.2017.1371198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan S., Dillistone K., Shin J.H. The gulf coast oil spill: Extending the theory of image restoration discourse to the realm of social media and beyond petroleum. Public Relations Review. 2011;37(3):226–232. [Google Scholar]

- Na Y. Strategic maneuvering by persuasive definition in corporate crisis communication: The case of Taobao’s response to criticism. Journal of Argumentation in Context. 2017;6(3):344–358. doi: 10.1075/jaic.17001.yan. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noguti V., Lee N., Dwivedi Y. Post language and user engagement in online content communities. European Journal of Marketing. 2016;50:695–723. [Google Scholar]

- Pang A., Shin W., Lew Z., Walther J.B. Building relationships through dialogic communication: Organizations, stakeholders, and computer-mediated communication. Journal of Marketing Communications. 2018 doi: 10.1080/13527266.2016.1269019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R.A. Ohio University; 1989. A theory of public relations. Unpublished Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Daily . 2017. Chinese spend 3 hours a day on their smartphones, ranking 2nd in the world: Survey.http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2017-06/28/content_29916889.htm Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen J., Ihlen Ø. Risk, crisis, and social media. A systematic review of seven years’ research. Nordicom Review. 2017;38(2):1–17. doi: 10.1515/nor-2017-0393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romenti S., Murtarelli G., Valentini C. Organizations’ conversations in social media: Applying dialogue strategies in times of crises. Corporate Communications an International Journal. 2014;19(1):10–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz F., Utz S., Goritz A. Is the medium the message? Perceptions of and reactions to crisis communication via Twitter, blogs and traditional Media. Public Relations Review. 2011;37(1):20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Shotter J. Dialogism and polyphony in organizing theorizing in organization studies: Action guiding anticipations and the contentious creation of novelty. Organization Studies. 2008;29(4):501–524. [Google Scholar]

- Sriramesh K., Vercic D. Routledge; New York: 2011. Culture and public relations. [Google Scholar]

- Statista . 2018. Number of monthly active Twitter users worldwide from 1st quarter 2010 to 2nd quarter 2018 (in millions)https://www.statista.com/statistics/282087/number-of-monthly-active-twitter-users/ Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Tai Z., Sun T. Media dependencies in a changing media environment: The case of the 2003 SARS epidemic in China. New Media & Society. 2007;9(6):987–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. Cultural variance as a challenge to global public relations: A case study of the Coca-Cola tainting scare in Western Europe. Public Relations Review. 2000;26:277–293. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M., Kent M.L. Dialogic engagement: Clarifying foundational concepts. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2014;26(5):384–398. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M., Perry D.C. Diffusion of traditional and new media tactics in crisis communication. Public Relations Review. 2005;31:209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Ting-Toomey S. The matrix of face: An updated face-negotiation theory. In: Gudykunst W., editor. Theorizing about intercultural communication. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y.Q., Lei S.H. War of position and microblogging in China. Journal of Contemporary China. 2013;22(80):292–311. [Google Scholar]

- Veil S.R., Yang A. Media manipulation in the Sanlu milk contamination crisis. Public Relations Review. 2012;38(5):935–937. [Google Scholar]

- Wigley S., Fontenot M. Crisis managers losing control of the message: A pilot study of the Virginia tech shooting. Public Relations Review. 2010;36(2):187–189. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong A., Wei L., Wang X., Tjosvold D. Guanxi’s contribution to commitment and productive conflict between banks and small and medium enterprises in China. Group & Organization Management. 2017;42(6):819–845. doi: 10.1177/1059601116672781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Qiao R., Shao G., Chen H. Research on Chinese social media users’ communication behaviors during public emergency events. Telematics and Informatics. 2016;34(3):740–754. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.-U. Effects of government dialogic competency: The MERS outbreak and implications for public health crises and political legitimacy. Journalism and Mass Communication Society. 2018;95(4):1011–1032. doi: 10.1177/1077699017750360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.L., Jiang L. Managing corporate crisis in China: Sentiment, reason, and law. Business Horizons. 2015;58:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2014.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L., Ki E.-J. The status of online public relations research: An analysis of published articles in 1992–2009. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2012;24(5):409–434. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Liu H., Davison R.M. Exploring the relationship between corporate reputation and the public’s crisis communication on social media. Public Relations Review. 2018;44(1):56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Anagondahalli D., Zhang A. Social media and culture in crisis communication: McDonald’s and KFC crises management in China. Public Relations Review. 2017;43:487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]