Abstract

Despite the enormous impact of food crises on restaurants, limited understanding of their long-term impacts and associated factors has undermined crisis managers’ ability to handle crisis situations effectively. This article investigated the long-term impact of food crises on the financial performance of restaurant firms and identified the factors that influenced this impact. This explanatory study examined the case of Jack in the Box, whose 1993 Escherichia coli scare was the first and largest restaurant-associated food crisis in modern times. An event study method was used to uncover stock price movements of Jack in the Box, in conjunction with 73 unrelated food crises that occurred from 1994 to 2010. Stock prices of Jack in the Box exhibited significantly negative responses to other firms’ food crises, moreover, the negative spillover effect was stronger if the crisis occurred closer in time, was similar in nature, and was accompanied with no recall execution. These findings shed light on the long-term financial impact of food crises and offer insights for crisis managers to develop more effective crisis management strategies.

Keywords: Food crisis, Negative spillover effect, Long-term impact, Event study method, Jack in the Box

1. Introduction

Negative spillover effects have been a popular topic in product-harm crisis research because such crises are both unexpected and devastating for firms. In this context, a spillover effect refers to the phenomenon in which information about brand A influences a consumer's beliefs regarding brand B, even if the impact is not explicit (Ahluwalia et al., 2001). Previous research has demonstrated the presence of spillover effect within the same brand family or product category (Balachander and Ghose, 2003), across product categories (Erdem, 1998), and from one product attribute to another (Ahluwalia et al., 2001). However, researchers have paid little attention to spillover effect at the firm level, which occurs across companies in the same category. For example, negative publicity regarding an Escherichia coli (E. coli hereafter) scare at Wendy's may negatively affect Jack in the Box, because of the indirect influence of negative publicity and the latter restaurant's prior association with E. coli.

Previous research suggests the presence of spillover effects among competitors. Siomkos et al. (2010) assert that a product harm crisis is an opportunity for competitors to take advantage of their weakened rivals, which implies a positive spillover effect. During rival firms’ crises, competitors can grab more market shares (Tsang, 2000, van Heerde et al., 2007) and increase consumer awareness through aggressive advertising (Dawar, 1998). Roehm and Tybout (2006) also find a negative spillover effect, demonstrating that negative consumer perceptions about one brand can spill over to competing brands in the same product category. Moreover, when a firm A has a crisis history, the advantage of being a competitor during a firm B's (rival firm) crisis may be offset by negative associations between the firm A and a crisis of firm B. In this respect, a rival's product harm crisis may become a threat if the firm is associated with a negative past event.

Crisis management researchers consider a firm's crisis history a critical factor (Coombs, 2004). Situational crisis communication theory posits that a history of crises becomes an important cue for determining reputational threats to firms (Coombs and Holladay, 2001, Coombs and Holladay, 2002). Moreover, existing information on a past crisis can shape consumers’ perceptions of current crises and influence reputational threats. Thus, a history of crises may amplify reputational threats and harm firms’ financial performance, even long after a crisis outbreak is over. Because 59% of all reported foodborne illness outbreaks in the United States are attributed to the restaurant industry (CDC, 2006), it is critical to investigate possible negative spillovers among restaurant firms. To that end, this study examines how negative spillover from unrelated crises influences a restaurant firm with a history of crisis.

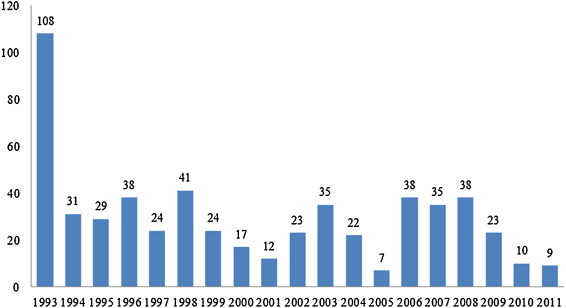

The Jack in the Box E. coli scare, Tylenol poisoning, Firestone's tire accidents, and Taco Bell's contaminated food incident were among the most cited examples of crises associated with well-known brands. Those incidents caused illnesses and deaths, resulted in negative consumer perceptions of quality, decreased sales revenues, tarnished firm reputations, and lower marketing efficiency (Dawar and Pillutla, 2000, van Heerde et al., 2007). Coombs (2004) suggested that despite its disastrous results, the unexpected and accidental nature of a crisis can serve as a cushion for affected firms in rebuilding consumer trust. However, empirical evidence shows that the media tend to report on past crises in relation to similar crises for very long time. For example, it is common for E. coli-related media reports to cite Jack in the Box as an example, though the event occurred 18 years ago. Fig. 1 displays the number of news articles containing words “Jack in the Box” and “E. coli” using LexisNexis database, evidencing that Jack in the Box still appears in media reporting in relation to E. coli up to present.

Fig. 1.

Number of news articles covering “Jack in the Box” in relation to “E. coli” by year.

Note: The E. coli event with Jack in the Box occurred in 1993.

If the media repeatedly mentions a restaurant firm with a crisis history, this is likely to evoke or reinforce negative images of the restaurant brand for consumers. Psychological research asserts that people access negative memories more easily and quickly than positive memories (Richins, 1983). Brands also depend heavily on publicity through widespread mass media, yet negative publicity is more powerful and salient in media reporting than positive publicity (Weinberger et al., 1991). Constant negative publicity can drive firms into a downward spiral (Weinberger and Romeo, 1989), and media attention may make a crisis more visible to the general public (Ahluwalia et al., 2000). In responding to other firms’ food crises, a firm with a food crisis history may be affected by unrelated crises, that is, by a negative spillover effect.

Seo et al. (2013) examined the impact of food safety events on firms, asserting that it takes approximately one year to recover from a crisis after an outbreak. Although their study investigated the impact of food crises on firms’ financial performance, the findings were limited to short-term impacts. To identify the long-term impact, the current study features an exploratory case study, using Jack in the Box, and investigates whether the firm's stock prices have been influenced by other restaurant firms’ food crises between 1994 and 2010. In addition, this study empirically tests for the presence of negative spillover on Jack in the Box's stock returns, while attempting to quantify the magnitude of spillover effect in terms of time, similarity, and recall execution.

2. Literature review

2.1. Negative spillover effect

Noting the prevalence of multiproduct systems, business researchers have paid substantial attention to negative spillover effects across multiple products or brands. Initially, researchers considered positive side effects from line or brand extension strategies (Balachander and Ghose, 2003). When spillover occurs within a brand family, information or perceptions about existing products transfer to newly launched products that use the same brand name, which ideally results in rapidly built consumer loyalty. Marketing practitioners cultivate brand relatedness and strength in their brand portfolio to increase marketing efficiency through positive spillovers.

On the other hand, circumstances also can activate negative spillover effects. Unexpected product harm crises or brand scandals may evoke a negative spillover effect on the products or brands if consumers perceive that products in a brand family share similar quality standards and brand images (Lei et al., 2008). Moreover, Dahlen and Lange (2006) found that a disaster for one brand can be “contagious,” such that it influences both the product category and competing brands. As brands come to depend more on publicity, the possibility of negative spillovers onto competitors when a firm experiences a crisis also increases. For example, even if brand A has little to do with the crisis associated with brand B, it may still be affected by negative publicity if there is any association between the two brands.

Considering the devastating results of Jack in the Box E. coli scare in 1993, which killed four children and sickened more than seven hundred people, it is expected that Jack in the Box may have experienced negative spillover effects from other firms’ food crises due to the association with other firms. Thus, this study proposes a hypothesis on the negative spillover effect from other firms’ food crises on Jack in the Box:

H1

There has been a negative spillover effect from other firms’ food crises on Jack in the Box.

2.1.1. Time and negative spillover effects

Prior crisis management research identified time as a crucial influence on consumers’ memory-based information processing (Standop, 2006, Vassilikopoulou et al., 2009). Unfavorable attitudes toward a crisis likely diminish over time; however, a longer period between a crisis and a product recall makes it more difficult for firms to regain consumers’ trust (Standop, 2006). Furthermore, Vassilikopoulou et al. (2009) assert that time significantly influences consumers’ perceptions, attitudes, and intentions. Consumers thus perceive less danger and adopt better impressions and future purchase intentions one year after a crisis, such that time helps reduce the negative effects of a crisis on consumer responses. Crisis managers then may expect to observe a time effect, by which consumers are less likely to recall a past negative event over time. Accordingly, a firm may be able to recover from a crisis. Thus, we hypothesize the time influence on negative spillover effect on Jack in the Box as:

H2

The negative spillover effect from other firms’ food crises on Jack in the Box is stronger when the negative spillover event is closer in time to the 1993 Jack in the Box E. coli outbreak (1993–2003) as compared to a negative spillover event that is farther away in time (2004–2010).

2.1.2. Similarity and negative spillover effects

The accessibility–diagnosticity framework offers a theoretical explanation of this negative spillover effect (Feldman and Lynch, 1988). The framework describes how the negative image of one brand spills over to perceptions of other brands if there is a strong association between them. When consumers consider brand A informative about brand B, its image influences perceptions of brand B. The framework also indicates that product similarity increases diagnosticity and accessibility (Feldman and Lynch, 1988). For example, attribute-level similarities have a greater effect than overall product similarity does on consumer perceptions (Broniarczyk and Alba, 1994, Roehm and Tybout, 2006). Moreover, categorization theory asserts that product similarity provides strong cues for categorization, which lead to higher levels of both diagnosticity and accessibility (Mervis and Rosch, 1981, Sujan, 1985). Resonance theory, which explains cognitive-oriented activities in information processing, indicates that greater correspondence induces a stronger resonance effect (Wan, 2008). It also supports the notion that the spillover effect is promoted by product similarity. Thus, when Lei et al. (2008) examined the effects of the strength and directionality of brand relatedness on spillovers within a brand family, they found that negative spillover within a brand family was stronger and more salient with a higher number of associations. Furthermore, Janakiraman et al. (2009) extended the scope of this research to a product category and tested negative spillover effects on competing brands. They found a moderating effect of product/brand similarity on perception spillovers, revealing that perception spillovers occurred when brands were sufficiently similar. Thus, this study proposes the effect of similarity in terms of operation type and type of foodborne illness on negative spillover effect on Jack in the Box:

H3

The negative spillover effect from other firms’ food crises on Jack in the Box is stronger when the similarity in terms of type of illness between the two events is greater.

H4

The negative spillover effect from other firms’ food crises on Jack in the Box is stronger when the similarity in terms of type of operation between the two events is greater.

2.1.3. Recall execution and negative spillover effects

When a firm fails to control the quality of products, the firm often results in product recalls. According to the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), the number of product recalls has increased due to frequent product-harm incidents (Chen et al., 2009). The underlying reasons of increase in product recalls include the globalization of production, the increased complexity of products, and closer attention of firms and government agencies (Berman, 1999). Notable examples of product recalls include Tylenol tampering in 1983, Jack in the Box's recall of contaminated beef in 1993, tire recalls of Firestone in 2000, Chinese milk scandal recalling baby products in 2008, and Toyota's recall of 7 million cars in 2009. Of those recalls, food product recalls are of great concern to the public due to its devastating influence threatening the public health.

Although the goal of recall execution is to safeguard the public and reduce consumers’ risk perception, the recall strategy often caused negative stock returns of a firm that announces the recall. Thomsen and McKenzie (2001) found significant negative returns of food companies following food recalls, and Chen et al. (2009) supported that proactive recall strategies caused more negative stock returns compared to that of passive recall strategies. In contrast, previous literature suggested positive consequences of recall execution such as increasing perceived responsiveness of a firm, reducing consumers’ risk perception, and maintaining future purchase intentions (Dawar and Pillutla, 2000, Siomkos and Kurzbard, 1994). More importantly, while previous research focused on the effect of recall strategy on a firm that announces the recall, the effect of recall announcement on other firms has not been explored.

Finance research has emphasized the role of industry factor, an industry-specific correlation among firms in the same field, as a significant driver influencing stock returns (Cavaglia et al., 2000). When a firm A deals with a crisis, the event may influence the stock returns of a firm B which is in the same industry with a firm A due to the high correlation that exists between firms in the same industry. The market evaluation of a firm A becomes a determinant of evaluation of a firm B by market investors. In this sense, a recall announcement of a hospitality firm A may become a driver influencing market evaluations of a hospitality firm B especially when the firm B has a past crisis history. Considering the positive effect of recall execution in reducing consumers’ risk perception (Dawar and Pillutla, 2000, Siomkos and Kurzbard, 1994), an announcement of a hospitality firm recalling suspected products may be perceived as positive signal by market investors which may reduce negative spillovers on other hospitality firms. In this sense, the recall execution may become a good news for other hospitality firms because investors perceive less risk with product recalls than without recalls. Thus, this study proposes a hypothesis as:

H5

The negative spillover effect from other firms’ food crises on Jack in the Box is stronger when there is no recall execution as compared to when there is a recall execution.

2.2. Measuring the impact of crises

Previous crisis management research has examined factors that influence the impact of crises, such as the amount, intensity, and type of media attention (Jolly and Mowen, 1985, Weinberger and Romeo, 1989); the number of injuries or deaths (Mowen, 1980); the firm's reputation (Siomkos and Shrivartara, 1993); the type of crisis (Coombs, 1995, Mitroff and Pearson, 1993); and the company's response (Siomkos and Kurzbard, 1994). Whereas many studies focus on economic impacts, by examining changes in sales revenue or reductions in production volume (Janakiraman et al., 2009, Tsang, 2000, van Heerde et al., 2007), little research uses stock market measures to assess the economic impacts of food crises.

A few studies use accounting indicators, such as return on assets and return on investment, to measure the impact of specific events (Dickerson et al., 1997, Hsu and Jang, 2007). However, accounting measures lack technical robustness, because some accounting data are only available on a quarterly basis. In addition, accounting measures reflect the impacts of both firm- and market-specific events, making it difficult to tease out the impact of firm-specific events.

Coombs (2004) uses a scenario-based survey to examine the impact of crisis history on consumers’ perceptions of crises. Although Coombs reports significant findings, such as an intensifying effect of a past crisis on consumers’ responses, measuring consumer intentions cannot fully capture the impact on associated firms. In contrast, event studies that investigate stock price movements (Chang and Zeng, 2011, Chen et al., 2007, Salin and Hooker, 2001) suggest that market measures capture immediate and direct reactions to crisis outbreaks. According to the efficient market hypothesis, changes in stock prices represent the economic impacts of a particular event, based on the market's evaluation of the firm's future cash flows (Fama, 1970). Thus, stock returns were selected for the current study to measure the economic impact of food crises on an associated firm.

2.2.1. Event study method

The efficient market hypothesis assumes that the stock market rapidly incorporates all available information into a firm's value (Mizik and Jacobson, 2004). According to this hypothesis, investors buy or sell stocks according to updated expectations formed by the stock market. Thus, information providing a positive (or negative) cue in terms of expected future cash flows will have a positive (or negative) influence on stock returns. Because of the efficiency of the market, abnormal returns (ARs) provide an unbiased estimate of future earnings (i.e., changes in market value) due to an event (Fama, 1970). A surprising event such as a crisis can strongly influence investors’ decisions and thus ARs, because estimations underscore the long-term future cash flows of firms under crises.

The event study method (ESM), pioneered by Fama et al. (1969), is widely used to measure changes in stock prices (i.e., changes in market expectations of a firm's future value) associated with the release of new information. This method is used frequently in both finance and marketing research to investigate the effect of stars on the success of movies (Elberse, 2007), television stock recommendations targeting naive investors (Karniouchina et al., 2009), and brand extension announcements (Lane and Jacobson, 1995), for example. Crisis management research has extensively used ESM to explore the impact of product recall announcements (Chen et al., 2009, Thomsen and McKenzie, 2001), the announcements of mergers or acquisitions (Dodd and Warner, 1983), positive and negative economic news (Chan, 2003), and the financial crisis in Japan (Miyajima and Yafeh, 2007).

Despite the advantages of using the event study analysis, there are constraints when using the method such as the availability of precise event dates and the price-sensitivity of the events. It is not desirable to use the method when the event dates are not precise and when events are not price-sensitive because the impacts may not be incorporated into stock prices (Brown and Warner, 1980). In addition, although most event studies rely on parametric test statistics, the parametric tests are considered to lack detailed assumptions about the probability distribution of returns. Instead, the use of non-parametric tests such as sign test and rank test is suggested by Cowan (1992) to ensure the results of parametric test statistics. In order to overcome such shortfalls of using event study method, the current study identifies the event dates using Marler Clark's website while cross-referencing the LexisNexis database. To eliminate the confounding effects, treatments are made as explained in the methodology section. Lastly, both parametric and non-parametric tests are performed to confirm the reported test results as suggested by Peterson (1989).

While ESM has often appeared in hospitality research, most previous hospitality research measuring stock price movements has investigated the short-term impact of a specific event on hospitality firms. For example, Chen et al. (2007) examined the impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreaks on the stock returns of seven hotels in Taiwan within one month after the outbreak. Salin and Hooker (2001) investigated the influence of food recalls on stock prices of four food-related firms after 10, 20, 30 and 40 days since the recall announcements. In addition, hospitality research investigated the impact of fed policy announcements (Chen, 2012), terrorist activities (Chang and Zeng, 2011), and IT news (Lee and Connolly, 2010) on hospitality stock returns. Although a number of studies examined the short-term impact of crises or events, research on the long-term effects of a food crisis is lacking. Thus, the current study investigates the long-term impact of food crises on a firm with a past crisis history.

Although conducting a case study may not fully explain the impact of events on firms, the results obtained from a case study provide important empirical evidence about the severity of food crises and its impact on associated firms in the long run. This method is effective and widely used to examine crises, which tend to occur infrequently. For example, van Heerde et al. (2007) examined the impact of product harm crises on marketing efficiency by using Kraft Food Australia's 1996 salmonella food poisoning case. Rittichainuwat (2006) also used a case study of the tsunami that hit Thailand in 2004 to examine how the tourism industry recovers from natural disasters. In turn, this study examines the negative spillover effects reflected in stock returns due to food crises, using a case study of Jack in the Box, by adopting ESM.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

Jack in the Box, founded in 1951, is among the nation's leading fast food restaurant chains, currently with more than 2200 restaurants operating in 19 states in the United States. In January 1993, Jack in the Box suffered a major corporate crisis from an E. coli outbreak that gained tremendous media attention and shocked millions of customers. The Jack in the Box E. coli outbreak remains the largest and deadliest food crisis associated with restaurants. It resulted in the deaths of four children and sickened more than 700 people in multiple states. Jack in the Box lost millions of dollars in sales and revenue as a result of the crisis (Braun-latour et al., 2006). As an effort to recover its brand image and regain consumer confidence, Jack in the Box took several responsive recovery actions, including recalling products, closing restaurants, retraining employees, and conducting several nationwide marketing campaigns (Israeli, 2007). By the mid-1990s, those efforts were largely successful such as increases in sales and revenue, and in 1997, the lawsuits came to a close. In 2004, Jack in the Box became a recipient of the “Black Pearl” award for innovations in food safety and quality. Accordingly, it is frequently considered a successful case of recovering from a food-related crisis. However, are there possible negative spillovers from other firms’ food crises on Jack in the Box? or did Jack in the Box fully recover from the devastating memory of E. coli?

The Jack in the Box incident still remains the primary example of restaurant-associated food crises in U.S. history. To examine how Jack in the Box has been influenced by unrelated food crises since 1993, this study identified food crises in the past 18 years (1994–2010) that were associated with food-related firms, such as restaurants, food manufacturers, and food distributors. Because the purpose of this study is to examine the spillover effect from other firms’ food crises on the market value of Jack in the Box, thus, we excluded the 1993 incident from the data set and focused only on food crises associated with other firms.

A list of foodborne illness outbreaks that had occurred since 1993 was obtained from the website of Marler Clark, a major law firm handling lawsuits related to foodborne illness outbreaks (http://www.marlerclark.com/). Marler Clark attorneys have represented victims of most foodborne illness outbreaks since 1993, when the law firm was established to handle the Jack in the Box case. Marler Clark's archive is considered a reliable source for restaurant-associated foodborne illness outbreaks (Seo et al., 2013). When a lawsuit has been filed following a food crisis, it indicates that the crisis is serious, creating the possibility of a spillover effect on Jack in the Box. Using the Marler Clark's archive, food crisis-related information was collected including the year, date, type of foodborne illness, associated firm, recall execution, and the number of people sickened or killed by the illness.

In order to eliminate any confounding effects, two treatments were put in place. First, as suggested by McWilliams and Siegel (1997) and Wiles and Danielova (2009), we eliminated firms (cases) that were associated with announcements of mergers and acquisitions, earnings/dividend spin-offs, stock splits, key executives changes, lawsuits, and new product introduction between the period 2 days before and after the identified outbreak date. Second, any cases overlapped with significant events of Jack in the Box were removed from the data. The events of Jack in the Box included announcements of implementing HACCP (Hazard Analysis & Critical Control Points) to manage food safety and quality of foods, changing the company name from Foodmaker to Jack in the Box Inc, conducting a new advertising campaign, and winning food safety award during the period from 1993 to 2010 (Miller, 2007). As a result, the total number of cases was reduced from 85 to 73 after removing twelve confounding cases.

The sample for this study thus consisted of 73 food crises associated with restaurants, food manufacturers, and food distributors. This sample size was comparable with that of other event studies; for example, Salin and Hooker (2001) used 4 observations, Horsky and Swyngedouw (1987) used 58, Lane and Jacobson (1995) used 89, and Geyskens et al. (2002) used 93.

3.2. Analyses

We used ESM and subsequent analyses to compute the ARs and cumulative abnormal returns (CARs), then conducted a series of t-statistic tests to investigate the effects of similarity (restaurant/non-restaurant, E. coli/non-E. coli), time (within 10 years/20 years), and recall execution (recall/non-recall) on ARs and CARs. The University of Chicago's Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) was used to obtain daily stock returns for Jack in the Box from 1993 to 2010, consistent with previous literature (Chen et al., 2009). In addition, with an estimation window of 275 trading days, or one calendar year, ending 20 days before the event, we calculated market returns using an equal-weighted index (Cowan, 2003). By using the daily stock returns for Jack in the Box and market returns obtained from CRSP data files, both ARs and CARs were calculated. Following Brown and Warner (1980), a market model was chosen to obtain the estimates of expected returns.

Specifically, the returns for Jack in the Box (JACK) were computed as the difference between the closing price on day t (P t) and day t − 1 (P t – 1) (Eq. (1)). The stock returns for JACK were regressed against the return of market index to remove overall market effects (Eq. (2)):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where R t = the return of JACK on day t; P t = the closing price of JACK on day t; and R mt = the market return on day t.

Next, the expected returns were calculated by performing ordinary least squares regression analysis using the β estimate obtained from Eq. (2) (Eq. (3)). The AR was calculated by subtracting the expected returns (ERt) from the stock returns (R t) (Eq. (4)). As ESM specifies, AR refers to the difference between actual and expected returns, such that it can reflect the isolated effects of a firm-specific event, separate from overall market movements. In the current study, AR is calculated as the average value of JACK's stock prices in response to 73 events. We calculated CAR as the sum of daily ARs (Eq. (5)). For example, CAR 1 is calculated as the sum of AR on day 0 and AR on day 1, CAR 2 is the sum of AR on day 0, AR on day 1, and AR on day 2. Thus, CARs represent the average cumulative impacts on JACK from 73 others’ events.

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where AR is abnormal return of stock prices; CAR is cumulative abnormal return of stock prices.

To test the significance of ARs and CARs, the t-statistic on any day t in the event window was performed. The t-statistics follows a standard normal distribution based on the guidance of Campbell et al. (1997). If the outbreak of others’ crises caused abnormal returns, the t-statistics should be significantly different from zero, otherwise, the t-statistics should not be significantly different from zero. In addition, if results show negative significance, it is assumed that others’ crises had negative impacts on stock returns of Jack in the Box. In other words, the market perceived the others’ crises as negative information when evaluating the value of Jack in the Box.

3.3. Cross-sectional analysis

To identify significant factors influencing negative spillovers, a cross-sectional analysis was performed as suggested by Root and Contractor (1981), Brown et al. (2003), and Graf (2009). In order to perform the cross-sectional analysis, data were categorized into two groups in terms of four variables including the (1) recentness of outbreak time to the time of Jack in the Box event (whether an event occurred between 1993 and 2003 or 2004 and 2010), (2) similarity with Jack in the Box in terms of the type of foodborne illness (whether an event was associated with E. coli or non-E. coli), (3) similarity with Jack in the Box in terms of the operation type (whether an event was associated with restaurant or non-restaurant), and (4) recall execution (whether an event was accompanies with recall execution or not).

There were two control variables which may have influenced the impacts of events on stock returns: (1) severity of risks and (2) level of media attention. The severity of risks was coded as the number of illnesses caused by each event, and media attention was recorded as the number of news articles covering each event, which were obtained using LexisNexis database. Those two control variables were used as covariate variables when running the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA).

To test the effect of time (within 10/20 years), similarity in terms of foodborne illness type (high/low), similarity in terms of operation type (high/low), and recall execution (yes/no) on ARs and CARs for JACK, we performed ANCOVA as a parametric test. Unlike previous studies using a regression analysis for cross-sectional analysis (Borde et al., 1999, Chang and Zeng, 2011), this study used ANCOVA because of dichotomized nature of testing variables as well as the benefit of ANCOVA in showing the pattern of changes in ARs and CARs over time. With the ANCOVA, we can compare and test for the significance of the differences between the two groups. In addition, considering the small sample size of each group, we performed a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test to verify the results of the ANCOVA; as Corrado (1989) notes, it is advantageous to use nonparametric tests in event studies.

Previous literature using ESM has suggested the appropriate use of event window depending on the nature of research. While some previous research used one or two-day event window to examine immediate stock reactions to brand or product-related news (Lane and Jacobson, 1995, Elberse, 2007), a relatively longer event window has been used by crisis-related research. For example, Chen et al. (2007) used a 20-day event window to test the impact of SARS outbreaks, Salin and Hooker (2001) adopted a 40-day event window to investigate the impact of food recalls, and Chang and Zeng (2011) used a 40-day event window to measure the impact of terrorism on hospitality stock returns. Thus, a 30-day event window was used to examine the stock prices of JACK in responding to the outbreaks of seventy-three events.

4. Results

4.1. Impact of the E. coli scare in 1993 on Jack in the Box (JACK)

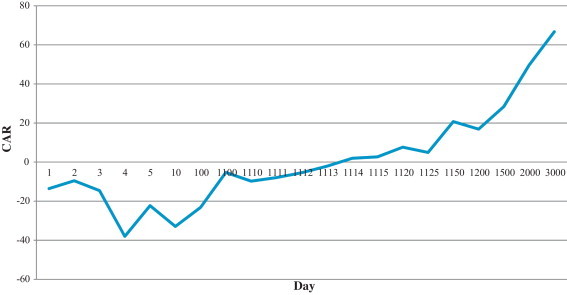

We examined stock prices for Jack in the Box (JACK, hereafter) since 1993 to identify the seriousness and duration of a food crisis. Because positive (negative) abnormal returns (AR) or cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) indicate a positive (negative) market evaluation of the firm's future value, we pinpointed when CARs for Jack in the Box showed positive values, to find the point at which recovery from the E. coli outbreak occurred. The first news report that covered the E. coli scare associated with Jack in the Box was released on January 18, 1993. Beginning with the first day, we calculated CARs by summing daily ARs. For example, the calculated AR for Jack in the Box was −1.9018 for January 18, 1993 (t 0), and −11.6767 for January 19, 1993 (t 1). Between January 18, 1993, and January 19, 1993 (t 0 − t 1), the CAR was −13.5785, or the sum of −1.9018 and −11.6767.

As Fig. 2 indicates, CAR for JACK turned positive on June 16, 1997, the 1,114th day since the first outbreak day, indicating that it took JACK almost 4.5 years to recover from the E. coli outbreak. This result depicts the seriousness and duration of food safety events through changes in the market values of JACK. Even acknowledging that JACK's E. coli outbreak was notable, as the first and most devastating food safety event at the time, similar crises could easily affect other restaurants in the future. Although it is not possible to generalize results from a single case, the results of this study offer a warning to restaurant managers, by highlighting the detrimental impact of a one-time food safety event.

Fig. 2.

The impacts of E. coli scare in 1993 on Cumulative Abnormal Returns (CARs) of Jack in the Box (1993–2002).

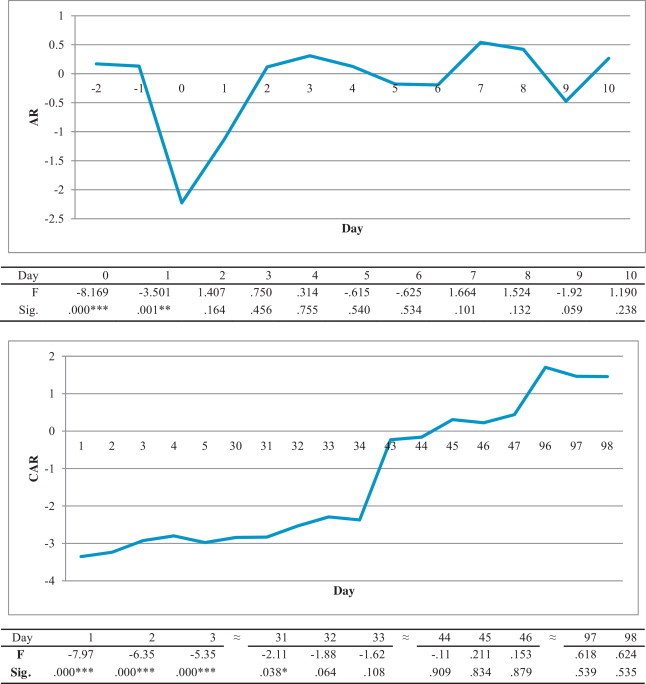

4.2. Impacts of other firms’ food crises on JACK

As Fig. 3 presents, ARs of JACK were significantly negative in response to other food crises on the outbreak day (day 0) and the following day (day 1). Moreover, CARs were significantly negative until the 31st day. Afterwards, the negative value turned positive on the 45th day after the outbreak although the CARs were not statistically significant. This result demonstrates that unrelated food crisis outbreaks caused JACK to experience negative market evaluations, even though JACK had nothing to do with the food crises.

Fig. 3.

Significance of ARs and CARs of Jack in the Box in response to 73 other food crises.

Note: The figure shows ARs and CARs of JACK in response to 73 food crises associated with other food-related firms which occurred from 1993 to 2010. Day indicates the number of days since the outbreak. AR is an indicator of abnormal stock returns, and CAR is an indicator of cumulative impacts since the outbreak of events. ARs or CARs which are below 0 indicate the occurrence of negative events, and those over 0 indicate the occurrence of positive events. The table shows the significance of ARs and CARs, supported by t-test. Significantly negative t-value evidences the negative impacts of events. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

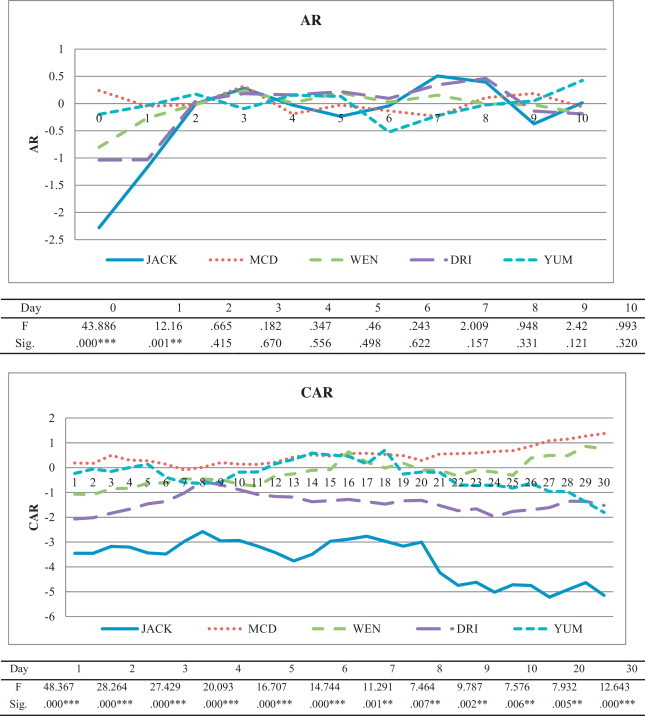

4.3. Is the negative spillover effect on JACK stronger than on other chain restaurant firms?

To determine whether ARs and CARs for JACK are significantly more negative than those for other firms, we examined four national chain restaurant firms in terms of ARs and CARs in response to the same 73 food crises. McDonald's, Wendy's, Darden Restaurants (which owns Olive Garden and other chains), and Yum Brands (owner of KFC and Taco Bell) were selected because these four companies are leading restaurant chain firms compatible with Jack in the Box. Following the same data collection procedure used for JACK, we obtained historical stock prices for the four restaurant firms from CRSP in line with previous literature (Chen et al., 2009). In order to eliminate the confounding effect, any cases within the period of 10 days before and after foodborne illness outbreaks of Wendy's, Darden, Yum, and McDonald's were removed from data prior to the analysis. Those events include, for instance, foodborne illnesses associated with McDonald's in 1998, Wendy's in 2000, KFC in 2002, Olive Garden in 2005, and Taco Bell in 2006. This elimination enables us to remove the possibility of negative spillover of other firms on themselves regardless of the influence of Jack in the Box. The ARs and CARs of the four restaurant firms (hereafter, OTHER) were calculated using the same event windows to determine whether the changes in ARs and CARs for OTHER differed from those for JACK. To test the significance of this difference, we also performed a one-way ANOVA.

The results indicate that JACK showed significantly lower ARs on the outbreak day (day 0) and the following day (day 1) compared with OTHER (Fig. 4 ). The pattern of CARs shows that JACK had significantly more negative CARs than OTHER, consistent with the changes in ARs. Whereas CARs for OTHER moved closer to or greater than 0 within 10 days of the outbreaks, JACK consistently showed significantly more negative ARs than OTHER, even 30 days after the outbreaks. The results imply that the negative spillover effect on JACK was much more pronounced than on OTHER.

Fig. 4.

Significance of spillover effect on Jack in the Box compared with other restaurants.

Note: The table shows the significance of difference between ARs and CARs of Jack in the Box and Other restaurant firms (McDonald's Inc., Wendy's Inc., Darden Restaurant Inc., Yum Brands Inc.) to 73 food safety events. As a parametric test, one-way ANOVA was performed to test the difference between Jack in the Box and others. Significant FF value indicates the presence of significant differences between two groups (Jack versus OTHER). Additionally, an analysis comparing Jack in the Box and Wendy's which are relatively similar in firm size is performed because the size of five firms varies considerably. The result of the additional analysis confirms that the negative spillover on Jack in the Box was significantly greater than that on Wendy's. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

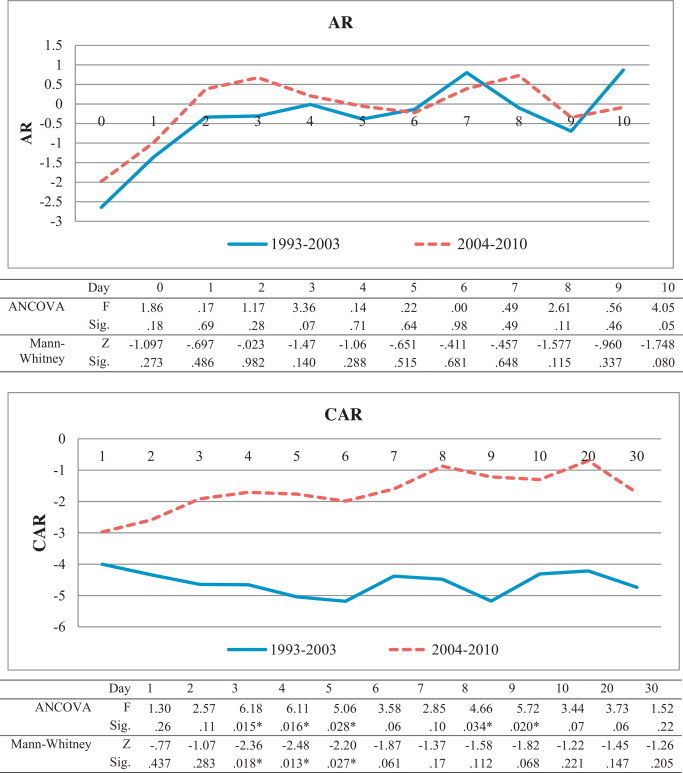

4.4. The effect of time on negative spillover effect

Fig. 5 shows that JACK experienced more negative ARs from events that occurred between 1993 and 2003 (within 10 years of JACK's E. coli outbreak) than from events that occurred between 2004 and 2010 (within 20 years after JACK's E. coli outbreak). The trend of changes in CAR indicates a more negative impact on JACK of events that occurred in the first 10 years after the outbreak compared with that of events that occurred in the next 10 years. The difference between CARs of JACK for both periods was significant until the ninth day, according to ANCOVA results, or until the fifth day, according to the Mann–Whitney U test results. Changes in CARs indicated that JACK was more likely to suffer from events that occurred closer to the original event (1994–2003) compared with events occurring further from the original event (2004–2010), in support of the proposition that the time effect reduces the negative spillover effect on JACK.

Fig. 5.

The effect of time on spillover on Jack in the Box.

Note: The figures show ARs and CARs of JACK in response to events occurred within 10 years (10 years events, 1993–2003, n = 27) and JACK's ARs and CARs to events occurred within 11–20 years (20 years event, 2004–2010, n = 46) since the E. coli scare in 1993. Overall, JACK showed more negative ARs and CARs to 10 years events (1993–2003) than those of 20 years events (2004–2010). The tables show the significance of difference between JACK's ARs and CARs to 10 years events and 20 years events. In consistent with previous analyses, both parametric test (ANCOVA) and non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U test) were performed to test the difference between two groups considering small sample size. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

People tend to recall negative events less as time goes by (Vassilikopoulou et al., 2009), which may be why the effect of negative spillovers on JACK's market values decreased. By highlighting the effect of time on spillover effects, these results provide empirical evidence that time heals, but spillover effects never completely disappear. If a firm experiences a food safety event, time may help it recover. However, the time effect alone cannot guarantee a full recovery.

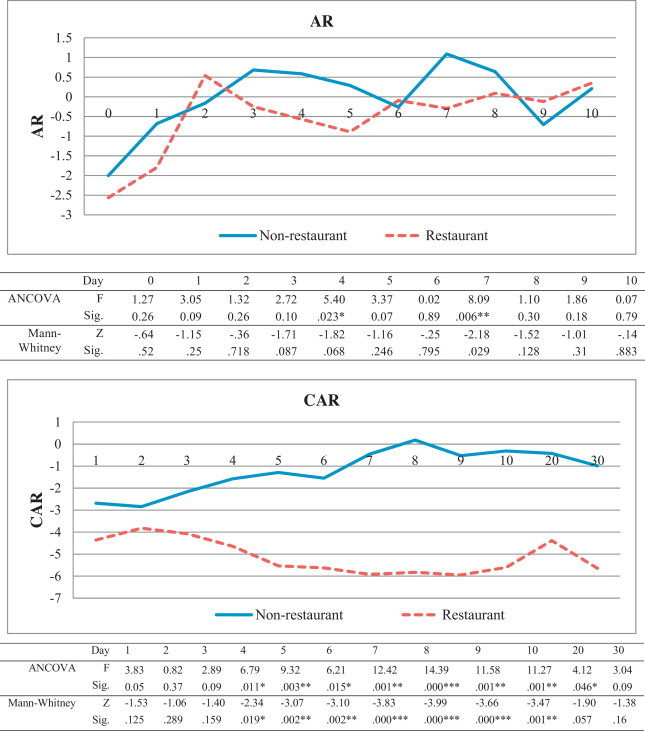

4.5. The effect of similarity in operation type on negative spillover effect

The effects of similarity in operation type (restaurant events vs. non-restaurant events) on spillovers on JACK were examined (Fig. 6 ). In response to restaurant events, ARs of JACK were significantly lower than non-restaurant events on days 4 and 7 (ANCOVA). Overall, changes in CARs suggest that JACK showed more negative CARs in response to restaurant events than to non-restaurant events. The differences between both cases were significant from day 4 to day 10, supported by both ANCOVA and Mann–Whitney U test results.

Fig. 6.

The effect of similarity (type of operation) on spillover on Jack in the Box.

Note: The figures show ARs and CARs of JACK in response to events associated with restaurants (restaurant events, n = 29) and non-restaurants (non-restaurant events, n = 44). Non-restaurant events include food manufactures, food distributors, catering service firms, and hotels. Overall, JACK's ARs and CARs were more negative to restaurant events than those of non-restaurant events. The tables show the significance of difference between restaurant events and non-restaurant events. Consistently, both parametric test (ANCOVA) and non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U test) were performed to test the difference between restaurant events and non-restaurant events. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The results imply that restaurant-associated food crises have a stronger spillover effect on JACK, revealing the similarity effect on negative spillover. When a food crisis was associated with restaurants, JACK suffered from more severe spillover effects than it did from nonrestaurant-associated food crises. Consistent with previous studies using the accessibility–diagnosticity framework (Broniarczyk and Alba, 1994, Roehm and Tybout, 2006), greater attribute similarity leads to stronger impacts on perceptions.

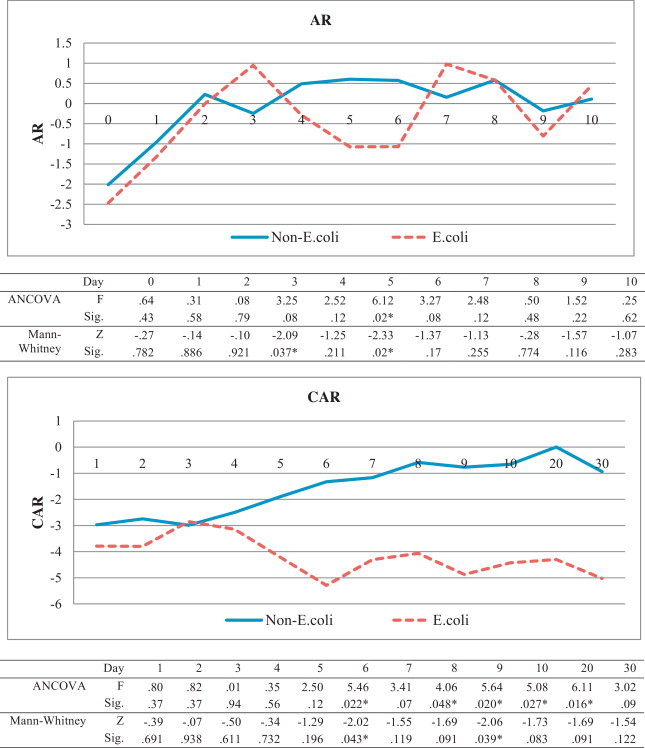

4.6. The effect of similarity in risk type on negative spillover effect

The ANCOVA results revealed that ARs for JACK were significantly lower for events associated with E. coli than events not associated with it on day 5 (Fig. 7 ). The trend of CARs showed that E. coli events caused much more negative CARs for JACK when compared with non-E. coli events, and we found significant differences from day 6 to day 20 (ANCOVA) and from day 6 to day 9 (Mann–Whitney U test).

Fig. 7.

The effect of similarity (type of foodborne illness) on spillover on Jack in the Box.

Note: The figure and table show the significance of difference between JACK's responses (ARs and CARs) to events associated with E. coli (n = 34) and to events associated with non-E. coli (n = 39). Non-E. coli events include Salmonella, Shigella, hepatitis A, and norovirus. Consistently, both parametric test (ANCOVA) and non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U test) were performed to test the difference between E. coli and non-E. coli groups. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

A similar risk type also influences the magnitude of spillover effects on JACK. Consistently, we found that similarity at the attribute level influenced perceptions and market evaluations of the future value of firms reflected in stock returns. When a food crisis was associated with E. coli, JACK experienced more severe impacts from the crisis than when a food crisis was related to other bacteria or viruses, such as Salmonella, Shigella, hepatitis A, or norovirus.

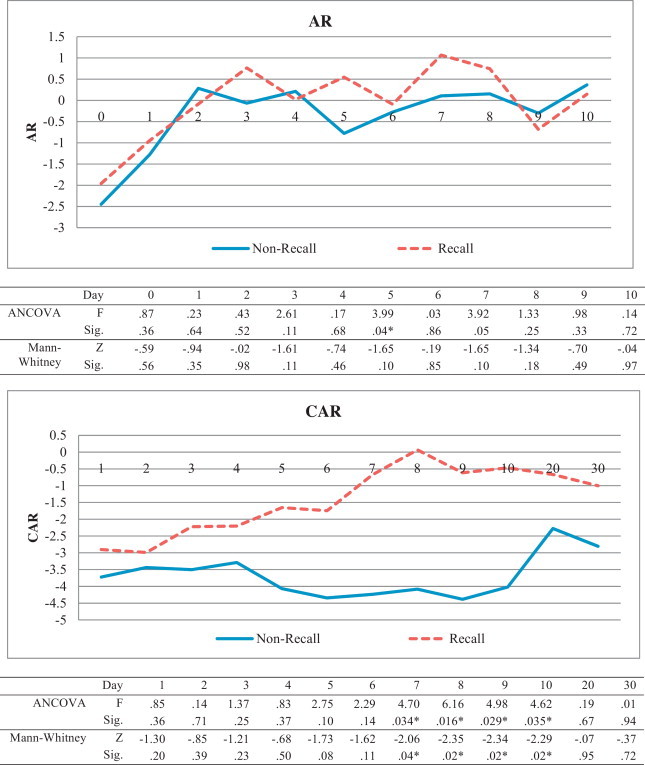

4.7. The effect of recall execution on negative spillover effect

Results indicated that recall execution of others caused less negative spillovers on JACK (Fig. 8 ). The differences in CARs between two events were found to be significant from day 7 to day 10 by both ANCOVA and Mann–Whitney U test. The result also indicates the presence of a time lag effect, implying that the effect of recall execution became more salient over time.

Fig. 8.

The effect of recall execution on spillover on Jack in the Box.

Note: The table shows the significance of difference between JACK's responses (ARs and CARs) to events that were accompanied with recall execution and events without recall execution. Consistently, both parametric test (ANCOVA) and non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U test) were performed to test the difference between groups with recall and without recall. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

This result unveils the role of recall execution in diminishing negative spillover effects on other firms. When a recall is announced by other hospitality firms, JACK experienced much less negative spillover from this event than from events without recalls, which emphasizes the important role of recall execution to other firms.

5. Conclusion, discussion, and implications

5.1. Summary of findings

Whereas previous research has explored the negative spillover effect within the same brand family, this study extends the scope to negative spillovers from one firm to another unrelated firm. Specifically, we anticipated that a firm with a crisis history may experience negative spillovers from unrelated crises, perhaps activated by consumer memory mechanisms and salient media reporting. The results of this study showed negative spillovers on Jack in the Box up to the present, as evidenced by stock return movements (ARs and CARs) in response to the outbreak of unrelated food crises. The negative spillover effect was influenced by time, the level of similarity in operation type (restaurant) and risk type (E. coli), and the recall execution. The negative spillover was stronger (weaker) when the crisis occurred within 10 years of the outbreak (10–20 years after the outbreak), when the crisis was associated with a restaurant (non-restaurant), was related to E. coli (non-E. coli), and there was no recall execution (recall execution).

5.2. Discussion

This research is among the first to examine the long-term impact of a food crisis on a restaurant firm using the case of Jack in the Box. This explanatory case study provides empirical evidence of negative spillover effects over a span of 18 years, indicating that a one-time food crisis may have long-term negative consequences on restaurant firms. However, the negative spillover effect on Jack in the Box has decreased over time; time heals wounds, though not completely. Although Jack in the Box was thought to handle the crisis effectively, it is unlikely that the restaurant chain can recover completely from the crisis. Several lessons thus emerge from the case of Jack in the Box.

Time heals wounds but the scar remains. This study indicates the presence of negative spillovers on Jack in the Box, up to the present. It is surprising that Jack in the Box still suffers from a negative event that occurred 18 years ago. Although the direct impact of its own E. coli outbreak event lasted less than five years, the negative spillover effect still has indirectly influenced Jack in the Box. This finding illuminates the severity of food crises on restaurant firms. It also evidences that consumers’ brand evaluations tend to be heavily influenced by publicity, especially negative publicity, which is consistent with previous literature (Weinberger and Romeo, 1989, Weinberger et al., 1991).

A positive message, however, for firms such as Jack in the Box comes from the time effect, which indicates that the negative spillover effect diminishes over time. For example, Jack in the Box suffered less negative ARs and CARs after recent crises, between 2004 and 2010, compared to those between 1993 and 2003. This result signals the effect of time in reducing negative spillovers on Jack in the Box. The findings provide useful cues to help crisis managers predict the severity and duration of their potential crises more accurately. Although there are exceptional cases, in which restaurant firms have gone out of business due to a crisis (e.g., Chi-Chi's restaurant), the general trend is that negative spillovers subside over time. Thus, the current research indicates that time heals wounds somewhat but not completely.

High similarity leads to a strong negative spillover effect. Similarity amplifies the negative spillover effect. This similarity effect, in terms of the magnitude and duration of negative spillovers on Jack in the Box, is consistent with previous literature (Janakiraman et al., 2009, Lei et al., 2008), which asserts that greater similarity between a current event and a past event evokes a stronger psychological association, resulting in a more pronounced negative spillover effect. Specifically, we found that similarity at the attribute level, such as operation type and risk type, affected the magnitude of the negative spillover effect on Jack in the Box (Broniarczyk and Alba, 1994, Roehm and Tybout, 2006). Following the accessibility–diagnosticity framework (Feldman and Lynch, 1988), the greater the similarity between a later crisis and the earlier Jack in the Box crisis, the stronger the negative spillover affects Jack in the Box. Consumers likely perceive stronger linkages between the current crisis and a past crisis if they are similar, which may result in stronger spillover effects on the firm with a crisis history. Therefore, if a crisis occurs in another firm that is similar to the firm's past crisis, a crisis manager must engage in crisis management efforts. This finding should help restaurant firms more effectively anticipate the magnitude of negative spillovers on their firms, depending on the level of similarity between a food crisis and their own crisis.

A firm's recall execution reduces negative spillover on other firms. The positive effect of recall execution provides evidence on the indirect influence of a firm's recall announcement which reduces the negative spillover on other firms. Although the current study did not examined the direct relationship between recall execution and negative spillover, the results of CARs responding to recall execution imply that stock returns are positively influenced by others’ recall announcements. When a hospitality firm announces a recall strategy, the recall is perceived as positive by investors which positively influence the market evaluation of other firms in the hospitality industry. The finding on the effect of recall execution is interesting considering previous literature emphasizing the negative consequences of recall announcement on stock returns (Chen et al., 2009, Thomsen and McKenzie, 2001). Although the recall announcement can threat stock returns of a hospitality firm suffering from their own crisis, the recall can be a positive signal to other firms in the hospitality industry. Given the positive consequences of recall execution, effective communication among hospitality firms during crises becomes more crucial to protect each other during one's crisis.

Time-lag effect is detected in the pattern of negative spillover. One interesting finding is that the significant differences between two groups tend to be found after a certain length of time rather than immediately, which is called “time-lag effect” (Gail, 2005). For example, with regards to the effect of time, similarity, and recall execution, the differences of CARs between two groups were turned into significant after three to seven days since the outbreak date. Such intensified impact of crises was detected earlier by Chen et al. (2007), supporting that the negative influence of SARS on stock prices was worse after 20 days than those of after 10 days since the outbreak. The authors noted that the impact of a foodborne illness outbreak is intensified because of the increasing number of illnesses or deaths over time. The finding of this study also supported that the negative spillover tends to be gradually influencing other firms’ stock price movements over a period of time.

The tendency may be explained using social amplification theory which argues that crises often evoke public fear and outrage (Sandman, 1993). The anger and outrage toward a firm can be amplified over time, which drives crisis managers to be unable to recover from a crisis. In addition, the “time-lag effect” is often found by finance research due to the time consumed for information dissemination to the public, and more importantly, the time spent to allow influences to be incorporated into stock prices. Considering the presence of time-lag effect caused by other firms’ food crises, the impacts are more likely to gradually spread and amplify. Acknowledging the possible presence of negative spillover effect may enable crisis managers to better prepare crisis communication strategies to prevent negative spillover from others’ crises.

5.3. Theoretical contributions and practical implications

This study contributes to crisis management literature in several important ways. The major contribution of the study is to uncover the presence of negative spillover effect on hospitality firms with past history, which extends the existing theoretical frameworks on hospitality crisis management. The present study shed lights on the hidden long-term impacts from food crises on hospitality firms by providing empirical results opposing the widely known successful story of Jack in the Box. Whether a firm has a past crisis history is considered a critical factor in Situational crisis communication theory (SCCT), influencing the type of appropriate crisis response strategies (Coombs, 2004). Considering that the SCCT model deals with the crisis of own company, the model can be extended by including factors influencing the negative spillover from others’ crises. Further, the appropriate crisis response strategies to others’ crises can be designed accordingly. Moreover, unlike previous research focusing on short-term impacts of crises, the examination on the long-term impact of crisis enriches the crisis-related hospitality literature. The idea of negative spillover effect in a long-term perspective can be further applied to other crises threatening the hospitality industry such as natural disasters and business fraud. In addition, the magnitude of negative spillover effect may differ depending on the type of crises, which may be a focus for future research.

The current study extends the usage of event study method. While previous research used changes in sales revenue or consumer behavioral intentions as the indicator of impacts of crises (Lei et al., 2008, Roehm and Tybout, 2006, van Heerde et al., 2007), this study adopted the ESM and provided empirical evidence of the impact of food crises on a firm's stock prices. Moreover, the current study also proves that event study method can be used for examining the long-term impacts of events not only the short-term events. While previous research introduced the event study method as a useful tool for short-term events (Chen et al., 2007, Chang and Zeng, 2011), the method can be an instrument examining long-term impacts of events.

The present study also offers practical implications to restaurant crisis managers. Others’ crises can be a severe threat if a firm has a crisis history. To avoid this negative spillover effect, crisis managers should deal appropriately with others’ crises, rather than ignoring them. Restaurant crisis managers should first identify the magnitude of the predicted negative spillover by examining the similarity of the ongoing crisis with their own crisis history, in terms of operation or crisis type. In addition, they should examine the seriousness of the crisis, which could drive negative publicity threatening firms during a time of crises. If a firm has a pre-developed crisis management plan, crisis managers should conduct appropriate crisis management strategies, such as communicating with the media and the public. Because social media has become a key business-to-customer communication tool, crisis managers could consider using this method to avoid possible negative spillovers from others’ food crises. Considering the importance of firms’ responses to crises (Siomkos, 1999, Siomkos and Shrivartara, 1993), performing an immediate crisis response may be a key strategy in successful crisis management.

Firms developing pre- and post-crisis management strategies can implement practical methods, such as a simulation-based scenario method. Medical and health care researchers have developed a simulation-based curriculum for clinical education and training in response to crises (Gaba et al., 2001, Gaba, 2004), and radiology crisis management researchers have developed a computerized realistic simulation (Sica et al., 1999). Using scenario-based crisis management strategies to train managers may enable restaurant and hotel managers to deal more appropriately with an unexpected crisis. In developing crisis scenarios, case studies may be especially effective as a means to predict diverse crisis situations and suggest appropriate response strategies. For example, Braun-latour et al. (2006) examined the childhood memory-based advertising strategy of Wendy's in responding to a hoax driving negative publicity in 2005. This unique advertising strategy helped it recover from its tainted brand image and might be useful when applied to other restaurant brands that suffer ill effects from rumors, hoaxes, and negative publicity. Chien and Law (2003) also investigated the responses of Hong Kong hotels to the SARS outbreak in March 2003, which provided good examples of appropriate responses by hotels during crises. Case studies offer various examples to use in developing scenario-based crisis management strategies. In this sense, the current study provides essential guidelines for restaurant crisis managers by not only warning of the danger of food crises but also offering response strategies when others experience their own crises.

Considering the immense impact of food crises, managers should pay more attention when determining their firms’ branding strategy. Restaurant firms should consider their branding strategy as a marketing tool that can not only increase brand awareness but also protect brands in case of crises (Rao et al., 2004). Although corporate branding can be an effective strategy to facilitate brand awareness, it also can endanger the whole brand family when faced with a crisis. In contrast, using a house-of-brand strategy, which allows sub-brands to use different names than the parent company, may protect members of the brand family when just one of them is involved in a crisis. In this sense, the house-of-brand strategy may be effective in minimizing negative spillover on the entire brand family. For example, in 1993, the parent company of Jack in the Box was Foodmaker, which held several other restaurant brands. Although Jack in the Box's crisis was a severe event, the images of other brands were not negatively influenced, because Foodmaker used the house-of-brand strategy causing weak associations among brands. If the parent company had used a corporate branding strategy, the results of the crisis might have been more severe.

5.4. Limitations and recommendations for future studies

Although this study makes several important theoretical and practical contributions, it is not without limitations. First, a case study approach limits the generalizability of these findings to other firms. By demonstrating the presence of negative spillovers on Jack in the Box, this study provides a snapshot of the impact of food crises on restaurant firms. Second, in addition to stock prices, there are other potential measures of the impact of a crisis on firms, such as return on assets, return on investment, or consumer perceptions. Although stock prices are immediate and direct measures, further studies may adopt other approaches to clarify the long-term impact of food crises on restaurant firms.

Considering that the current study only focused on food crises, future research may focus on other types of crises such as natural disaster, human-caused accidents, or business fraud. For instance, hotel industry has suffered from an accident like MGM Grand fire in Las Vegas in 1980 which killed 85 people, and 9/11 crisis from terrorist attacks in 2001 resulting in almost 3000 deaths (Stafford et al., 2002). The enhanced understanding on the impacts of such crises on hospitality industry may help crisis managers design effective crisis communication strategies. In terms of methodology, one method of examining the impact of crises on firms may be a longitudinal study which enables researchers to compare consumers’ intentions before and after the outbreak of crises. Despite the difficulty of conducting a longitudinal study, the method may overcome the limitation of the manipulated nature of scenario-based survey by maximizing the reality of survey. Lastly, although the current study used only one company, Jack in the Box, future studies may select more than one hospitality company that had similar crises in the past. For example, there were a number of hospitality companies suffered from foodborne illnesses such as salmonella and E. coli. The use of ESM along with the focus on other types of crises may enrich the existing crisis-related hospitality research.

Contributor Information

Soobin Seo, Email: seo.190@osu.edu.

SooCheong (Shawn) Jang, Email: jang12@purdue.edu.

Barbara Almanza, Email: almanzab@purdue.edu.

Li Miao, Email: lmiao@purdue.edu.

Carl Behnke, Email: behnkec@purdue.edu.

References

- Ahluwalia R., Burnkrant R.E., Unnava H.R. Consumer response to negative publicity: the moderating role of commitment. Journal of Marketing Research. 2000;37(2):203–214. [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia R., Unnava H.R., Burnkrant R.E. The moderating role of commitment on the spillover effect of marketing communications. Journal of Marketing Research. 2001;38(4):458–470. [Google Scholar]

- Balachander S., Ghose S. Reciprocal spillover effects: a strategic benefit of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing. 2003;67(1):4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-latour K.A., Latour M.S., Loftus E.F. Is that a finger in my chili? Using affective advertising for postcrisis brand repair. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly. 2006;47(2):106–120. [Google Scholar]

- Berman B. Planning for the inevitable product recall. Business Horizons. 1999;42(2):69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Borde S.F., Byrd A.K., Atkinson S.M. Stock price reaction to dividend increases in the hotel and restaurant sector. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research. 1999;23(1):40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Broniarczyk S.M., Alba J. The importance of the brand in brand extension. Journal of Marketing Research. 1994;31(2):214–228. [Google Scholar]

- Brown J.R., Dev C.S., Zhou Z. Broadening the foreign market entry mode decision: separating ownership and control. Journal of International Business Studies. 2003;34:473–488. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.J., Warner J.B. Measuring security price performance. Journal of Financial Economics. 1980;8(3):205–258. [Google Scholar]

- Cavaglia S., Brightman C., Aked M. The increasing importance of industry factors. Financial Analysts Journal. 2000:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan A.R. Nonparametric event study tests. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting. 1992;2(4):343–358. [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) Preliminary FoodNet data on the incidence of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food – 10 states, United States, 2005. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55(14) http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5514a2.htm?s_cid=mm5514a2e [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J.Y., Lo A.W., MacKinlay A.C. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1997. Event-study analysis. The Econometrics of Financial Markets; pp. 149–180. (Chapter 4) [Google Scholar]

- Chan W.S. Stock price reaction to news and no-news: drift and reversal after headlines. Journal of Financial Economics. 2003;70(2):223–260. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C., Zeng Y.Y. Impact of terrorism on hospitality stocks and the role of investor sentiment. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly. 2011;52(2):165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.H. The reaction of US hospitality stock prices to Fed policy announcements. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2012;31(2):395–398. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Ganesan S., Liu Y. Does a firm's product-recall strategy affect its financial value? An examination of strategic alternatives during product-harm crises. Journal of Marketing. 2009;73(6):214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.H., Jang S., Kim W.G. The impact of the SARS outbreak on Taiwanese hotel stock performance: an event-study approach. IJHM. 2007;26(1):200–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien G.C.L., Law R. The impact of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome on hotels: a case study of Hong Kong. IJHM. 2003;22(3):327–332. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4319(03)00041-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T. Choosing the right words: the development of guidelines for the selection of the “appropriate” crisis response strategies. Management Communication Quarterly. 1995;8(4):447–476. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T. Impact of past crises on current crisis communications: insights from situational crisis communication theory. Journal of Business Communication. 2004;41(3):265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T., Holladay S.J. An extended examination of the crisis situation: a fusion of the relational management and symbolic approaches. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2001;13(4):321–340. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T., Holladay S.J. Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Management Communication Quarterly. 2002;16(2):165–186. [Google Scholar]

- Corrado C.J. A nonparametric test for abnormal security-price performance in event studies. Journal of Financial Economics. 1989;23(2):385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan A.R. Cowan Research; Ames, IA: 2003. Eventus 7. 6 User's Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlen M., Lange F. A disaster is contagious: how a brand in crisis affects other brands. Journal of Advertising Research. 2006;46(4):388–397. [Google Scholar]

- Dawar N. Product-harm crises and the signaling ability of brands. International Studies of Management and Organisation. 1998;28(3):109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Dawar N., Pillutla M.M. Impact of product-harm crises on brand equity: the moderating role of consumer expectations. Journal of Marketing Research. 2000;37(2):215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson A.P., Gibson H.D., Tsakalotos E. The impact of acquisitions on company performance: evidence from a large panel of UK firms. Oxford Economic Papers. 1997;49(3):344–361. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd P., Warner J.B. On corporate governance: a study of proxy contests. Journal of Financial Economics. 1983;11(1–4):401–438. [Google Scholar]

- Elberse A. The power of stars: do star actors drive the success of movies? Journal of Marketing. 2007;71(4):102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem T. An empirical analysis of umbrella branding. Journal of Marketing Research. 1998;35(3):339–351. [Google Scholar]

- Fama E.F. Efficient capital markets: a review of theory and empirical work. Journal of Finance. 1970;25(2):383–417. [Google Scholar]

- Fama E.F., Fisher L., Jensen M.C., Roll R. The adjustment of stock prices to new information. International Economic Review. 1969;10(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman J.M., Lynch J.G. Self-generated validity and other effects of measurement on belief, attitude, intention, and behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1988;73(3):421–435. [Google Scholar]

- Gaba D.M. The future vision of simulation in health care. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2004;13(1):i2–i10. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.009878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaba D.M., Howard S.K., Fish K.J., Smith B.E., Sowb Y.A. Simulation-based training in anesthesia crisis resource management (ACRM): a decade of experience. Simulation & Gaming. 2001;32(2):175–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gail M.H. Time lag effect. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Geyskens I., Gielens K., Dekimpe M. The market valuation of Internet channel additions. Journal of Marketing. 2002;66(2):102–119. [Google Scholar]

- Graf N.S. Stock market reactions to entry mode choices of multinational hotel firms. IJHM. 2009;28:236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Horsky D., Swyngedouw P. Does it pay to change your company's name? A stock market perspective. Marketing Science. 1987;6(4):320–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu L., Jang S. The postmerger financial performance of hotel companies. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research. 2007;31(4):471–485. [Google Scholar]

- Israeli A.A. Crisis-management practices in the restaurant industry. IJHM. 2007;26(4):807–823. [Google Scholar]

- Janakiraman R., Sismeiro C., Dutta S. Perception spillovers across competing brands: a disaggregate model of how and when. Journal of Marketing Research. 2009;46(4):467–481. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly D.W., Mowen J.C. Product recall communications: the effects of source, media, and social responsibility information. Advances in Consumer Research. 1985;12:471–475. [Google Scholar]

- Karniouchina E.V., Moore W.L., Cooney K.J. Impact of mad money stock recommendations: merging financial and marketing perspectives. Journal of Marketing. 2009;73(6):244–266. [Google Scholar]

- Lane V., Jacobson R. Stock market reactions to brand extension announcements: the effects of brand attitude and familiarity. Journal of Marketing. 1995;59(1):63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Connolly D.J. The impact of IT news on hospitality firm value using cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) IJHM. 2010;29(3):354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Lei J., Dawar N., Lemmink J. Negative spillover in brand portfolios: exploring the antecedents of asymmetric effects. Journal of Marketing. 2008;72(3):111–123. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams A., Siegel D. Event studies in management research: theoretical and empirical issues. Academy of Management Journal. 1997;40(3):626–657. [Google Scholar]

- Mervis C.B., Rosch E. Categorization of natural objects. The Annual Review of Psychology. 1981;32:89–115. [Google Scholar]

- Miller B. 2007. Jack in the Box-recovering from mega-crisis.http://www.hrimtraining.org/paulbocuse/Case%20Studies/case_jackinbox.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mitroff I.I., Pearson C.M. Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 1993. Crisis management: A diagnostic guide for improving your organization's crisis preparedness. [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima H., Yafeh Y. Japan's banking crisis: an event-study perspective. Journal of Banking and Finance. 2007;31(9):2866–2885. [Google Scholar]

- Mizik N., Jacobson R. Stock return response modeling. In: Moorman C., Lehmann D.R., editors. Assessing Marketing Strategy Performance, Chapter 2. Marketing Science Institute; Cambridge, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mowen J.C. Further information on consumer perceptions of product recalls. Advances in Consumer Research. 1980;7:519–523. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson P.P. Event studies: a review of issues and methodology. Quarterly Journal of Business and Economics. 1989:36–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rao V.R., Agarwal M.K., Dahlhoff D. How is manifest branding strategy related to the intangible value of a corporation? Journal of Marketing. 2004;68(4):126–141. [Google Scholar]

- Richins M.L. Negative word-of-mouth by dissatisfied consumers: a pilot study. Journal of Marketing. 1983;47(1):68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rittichainuwat B.N. Tsunami recovery: a case study of Thailand's tourism. Cornell Hotel Restaurant Administration Quarterly. 2006;47(4):390–404. [Google Scholar]

- Roehm M.L., Tybout A.M. When will a brand scandal spill over, and how should competitors respond? Journal of Marketing Research. 2006;43(3):366–373. [Google Scholar]

- Root F.R., Contractor F.J. Negotiating compensation in international licensing agreements. Sloan Management Review. 1981;22(2):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Salin V., Hooker N.H. Stock market reaction to food recalls. Review of Agricultural Economics. 2001;23(1):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sandman P.M. Responding to community outrage: strategies for effective risk communication. AIHA. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Seo S., Jang S., Miao L., Almanza B., Behnke C. The impact of food safety events on the value of food-related firms: an event study approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2013;33:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sica G.T., Barron D.M., Blum R., Frenna T.H., Raemer D.B. Computerized realistic simulation: a teaching module for crisis management in radiology. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1999;172(2):301–304. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.2.9930771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomkos G.J. On achieving exoneration after a product safety industrial crisis. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing. 1999;14(1):17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Siomkos G.J., Kurzbard G. The hidden crisis in product-harm crisis management. European Journal of Marketing. 1994;28(2):30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Siomkos G.J., Shrivartara P. Responding to product liability crises. Long Range Planning. 1993;26(5):72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Siomkos G.J., Triantafillidou A., Vassilikopoulou A., Tsiamis I. Opportunities and threats for competitors in product-harm crises. Marketing Intelligence & Planning. 2010;28(6):770–791. [Google Scholar]

- Sujan M. Consumer knowledge: effects on evaluation strategies mediating consumer judgments. Journal of Consumer Research. 1985;12(1):31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford G., Yu L., Kobina A.A. Crisis management and recovery how Washington, DC, hotels responded to terrorism. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly. 2002;43(5):27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Standop D. Product recall versus business as usual: a preliminary analysis of decision-making in potential product-related crises. Ninety-nineth EAAE Seminar on ‘Trust and Riskin Business Networks’; Bonn, Germany, 8–10 February; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M.R., McKenzie A.M. Market incentives for safe foods: an examination of shareholder losses from meat and poultry recalls. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2001;82:526–538. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang A.S.L. Military doctrine in crisis management: three beverage contamination cases. Business Horizons. 2000;43(5):65–73. [Google Scholar]

- van Heerde H.J., Helsen K., Dekimpe M.G. The impact of a product-harm crisis on marketing effectiveness. Marketing Science. 2007;26(2):230–245. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilikopoulou A., Siomkos G., Chatzipanagiotou K., Pantouvakis A. Product harm crisis management: time heals all wounds? Journal of Retailing & Consumer Service. 2009;16(3):174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Wan H.H. Resonance as a mediating factor accounting for the message effect in tailored communication: examining crisis communication in a tourism context. Journal of Communication. 2008;58(3):472–489. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger M.G., Romeo J.B. The impact of negative product news. Business Horizons. 1989;32(1):44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger M.G., Romeo J.B., Piracha A. Negative product safety news: coverage, responses, and effects. Business Horizons. 1991;34(3):23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles M.A., Danielova A. The worth of product placement in successful films: an event study analysis. Journal of Marketing. 2009;73(4):44–63. [Google Scholar]