Abstract

Since the emergence of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, social scientists and sociologists of health and illness have been exploring the metaphorical framing of this infectious disease in its social context. Many have focused on the militaristic language used to report and explain this illness, a type of language that has permeated discourses of immunology, bacteriology and infection for at least a century. In this article, we examine how language and metaphor were used in the UK media's coverage of another previously unknown and severe infectious disease: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). SARS offers an opportunity to explore the cultural framing of a less extraordinary epidemic disease. It therefore provides an analytical counter-weight to the very extensive body of interpretation that has developed around HIV/AIDS. By analysing the total reporting on SARS of five major national newspapers during the epidemic of spring 2003, we investigate how the reporting of SARS in the UK press was framed, and how this related to media, public and governmental responses to the disease. We found that, surprisingly, militaristic language was largely absent, as was the judgemental discourse of plague. Rather, the main conceptual metaphor used was SARS as a killer. SARS as a killer was a single unified entity, not an army or force. We provide some tentative explanations for this shift in linguistic framing by relating it to local political concerns, media cultures, and spatial factors.

Keywords: Epidemics, Metaphor, SARS, AIDS, UK

Introduction

An epidemic of a previously unknown infectious disease spread across several parts of the world in spring 2003. This new disease, given the name Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), inspired a major response from the international public health community, as well as from the local governments affected. Although the transmission of SARS was successfully halted in only a few months, it was initially uncertain whether the disease would be controlled, and from the outset SARS was identified and responded to as an exemplary problem of ‘emerging infectious disease’ to be addressed in a globalized context where medicine, national and international public health, politics and commerce interconnect.

Categorised as a global threat, SARS received intensive coverage in the international media, even in countries where the disease did not establish itself. In this paper, we examine the cultural framing of SARS in print newspapers in the UK, focusing on metaphors as cultural and linguistic tools for conceptualising disease. We argue that the framing of SARS through narratives, metaphors, clichés and analogical matrices shows a significant difference from recognised and studied cultural frameworks for interpreting epidemic diseases that have been largely derived with reference to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Most strikingly, coverage of SARS avoided the use of war and plague metaphors, which normally dominate ‘control of disease’ discourse, instead relying on a combination of killer and control metaphors. This article tries to establish whether the new medical and political configuration of disease features that characterised SARS contributed to new cultural patterns in the reporting of this disease (see Fox & Swazey, 2004).

Metaphors, medicine and policy

SARS first came to international attention in March 2003, some months after it first emerged in Guangdong province in China. What appeared to be initial outbreaks in Hong Kong and Vietnam led to the World Health Organisation (. (2003, 27 Nov)), World Health Organisation (. (2003, 31 Dec)) initiating an international alert through its new Global Outbreak and Response Network (GOARN), sending in teams to assist local public health services, and organising an international scientific effort to learn about the new disease—which rapidly identified a coronavirus as the biological agent responsible. The vast majority of the 8096 cases and 774 deaths from SARS were in China, but the disease spread to a number of other locations, notably Toronto (251 cases), Singapore (238 cases) and Taiwan (346 cases). After a period of rapid diffusion, outbreaks were contained through a combination of surveillance, quarantine methods and travel bans, beginning with Vietnam (where the end of local transmission was declared on 28 April). Case numbers peaked in May 2003. By 5 July, the last paths of transmission had been broken, and only a small number of individuals were still recovering from the disease.

In labelling SARS as an emerging infectious disease, public health officials, politicians and media commentators located it among the set of pathogens—including HIV/AIDS, Ebola, West Nile fever, multi-drug resistant TB and others—that have emerged as threats to global health since the early 1980s, fracturing confidence in Western medicine's therapeutic efficacy (King, 2002). One characteristic of Western reactions to these diseases has been a proliferation of instant critical analyses of policies and practices seeking to interpret the cultural and social factors at play within them.

The discourses and metaphors used to frame diseases have become a prominent subject within this literature. This interest in metaphor illustrates the impact of the ‘linguistic turn’, the emergence of ‘cognitive linguistics’ (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Turner, 2001), and the influence of critics, notably Susan Sontag, who have emphasised the interdependence of language and stigma in disease since the 1970s. Perhaps the most significant factor, however, is the character of the AIDS epidemic, by far the most widely discussed disease in social and cultural studies. The attention given to the cultural and linguistic framing of AIDS has been a direct response to the stigmatisation faced by those infected, and to the heated debates over the disease in the 1980s and 1990s. The significance of metaphor within this process has been widely analysed with some striking results, for example showing that negative AIDS metaphors can be correlated with the outcome of AIDS-related litigation in the US (Drass, Gregware, & Musheno, 1997; Rollins, 2002).

These and other studies of AIDS have played a crucial role in demonstrating the potency of language in shaping the impact of epidemic disease. Moreover, to a unique extent, the AIDS epidemic has been marked by the active contestation of language and metaphor. By 1992, Paula Treichler could state that ‘AIDS metaphors are now routinely compared and critiqued to refine their effectiveness and usefulness’ (Treichler, 1992: 87. See: Brandt, 1988; Gilmore & Somerville, 1994; Norton, Schwartzbaum, & Wheat, 1990; Hughey, Norton, & Sullivan-Norton, 1989; Gilmore & Somerville, 1994: 1351–1352; Sandahl, 2001). As a result, AIDS metaphors and language possess a fluid, overtly politicised character largely absent from other diseases, where metaphors tend to be more entrenched and less controversial (Sherwin, 2001: 346).

Alongside this work on HIV/AIDS, a broader critique of language in medicine, especially the reliance on particular dominant conceptual metaphors, has developed. Military metaphors have become a particular target in the two decades since they were powerfully anatomised by the critic and writer Susan Sontag (1978), Sontag (1989) in her essays on cancer, tuberculosis and AIDS (Annas, 1995; Patton, 1990: 59–60; Montgomery, 1991; Arrigo, 1999; Worboys, 2000; Gradmann, 2000, see also Clow, 2001). During this time, military metaphors have remained abundant. Even the ‘war on cancer’ that the American president Richard Nixon declared in the 1970s continues (Cox News Service, 2002; Lerner, 2003). Yet, such militaristic metaphors have drawbacks. Among sufferers, they promote shame and guilt (Sontag, 1978). Among policymakers and public health officials, ‘[m]ilitary thinking concentrates on the physical, sees control as central, and encourages the expenditure of massive resources to achieve dominance’ (Annas, 1995: 746). They can even arguably make it easier to ‘sacrifice people and their rights’ (Ross, 1986: 18). The consequences of this type of discourse can also be seen in comparable non-medical contexts, such as the disastrous UK response to the foot and mouth epidemic in 2001 (Nerlich, 2004). One result of these concerns about military metaphors has been a series of calls to replace them with more attractive alternative metaphors. Annas proposes an ‘ecological framework’; Sontag suggests a more absolute stripping away of metaphor altogether. What Sherwin described as ‘choosing politically liberating metaphors’ has become a widespread and urgent concern (Sherwin, 2001: 343; Treichler, 1992).

This politicised critique of metaphor is, however, based on a somewhat unbalanced empirical basis. Largely arriving on the back of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, it is oriented towards the rich and controversial language usages elicited by that disease. AIDS’ predominance in studies of metaphor is by no means exclusive: cancer, heart disease, tuberculosis and cholera have all been closely studied, if largely from patient narratives (Seale, 2001; Nations & Monte, 1996; Weiss, 1997; Gibbs & Franks, 2002). Yet little attention has been given to the wider social framing of diseases which have not attracted dramatic metaphorisation, particularly fast-moving, new infectious diseases, such as SARS. Only a few studies have emerged on Ebola, SARS and similar diseases (Unger, 1998; Washer, 2004). Sontag's suggestion that ‘diseases understood to be simply epidemic have become less useful as metaphors’ (1989: 72, emphasis added) may explain the neglect of such diseases by some researchers. However, given the narrow empirical basis of current arguments about language and policy, it is important to examine what effects metaphors have had in framing such diseases, and whether they present the same problems identified in HIV/AIDS or in broader critiques of militarism within medicine.

Fortunately, in scale and type, the impact of SARS has been different to HIV/AIDS. As a result, SARS offers an opportunity to explore the cultural framing of a less extraordinary epidemic disease and thereby to provide an analytical counter-weight to the very extensive body of interpretation that has developed around HIV/AIDS. In this article we investigate how the reporting of SARS in the UK press was framed, and how this related to media, public and governmental responses to the disease.

Sources and method

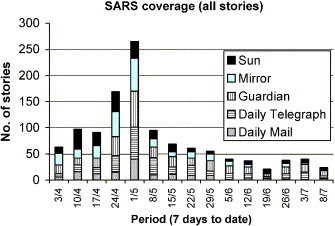

The study analysed coverage of the SARS story in five UK daily newspapers between its appearance in the press in March 2003 and the end of the epidemic in July 2003. Tabloid newspapers were represented by The Daily Mail, The Sun, and The Mirror, broadsheets by The Daily Telegraph and The Guardian, giving a cross section of political allegiances, editorial approach and readership profile. The study covered all the 1153 stories which referred to SARS in any way, extracted from the Lexis–Nexis database. Even brief mentions of SARS in business, sports and comic journalism were extracted and analysed. The study specifically sought to avoid focusing on ‘major’ articles and feature or editorial comments, where much of the heaviest use of metaphorical language tends to be located, to prevent cherry-picking lurid examples. The first stories appeared in The Mirror, The Guardian and The Daily Mail on 17 March, five days after the WHO issued its first alert. The last stories analysed appeared on 8 July, three days after Taiwan left the WHO's list of infected countries. Table 1 shows the pattern of coverage.

Table 1.

SARS coverage (all stories)

This comprehensive approach was chosen to provide a better coverage of the readers’ total exposure to the information and frames which structured representations of SARS in the media. The large corpus of material that resulted, inevitably presented a research challenge. Different quantitative approaches drawn from corpus linguistics and earlier metaphor studies (eg: Hughey, Norton, & Sullivan-Norton, 1989; see also Deignan, 1999 and Charteris-Black, 2004) were experimented with, but found to be inadequate for dealing with metaphor chains (see below) and the overlapping imagery common in the coverage. Instead, the qualitative method standard in linguistic metaphor studies was used, with adaptations to deal with the size of the corpus. This was based on two complete readings of the total corpus by separate researchers. On the first reading, qualitative research software was used to mark-up metaphors and repetitive tropes and outline a map of linguistic patterns and frequency. The second read through took the form of a structured reading of articles, with pieces from all newspapers read in sequence in seven-day blocs to establish chronological patterns and linguistic developments through the development of the corpus.

A great benefit of this inclusive approach was that it allowed us to look at extended stretches of media discourse and not only at isolated sentences, a method that still prevails in cognitive linguistics (see Stockwell, 1999). As a result, we have highlighted the main clusters or chains of metaphors. For example, in the killer metaphors discussed below, a metaphor system is developed that exploits various well-known features of ‘killers’ (they stalk, they strike, they are mysterious, they are criminals) and are through them linked to other metaphors, such as SARS IS A CRIMINAL (it has to be detected, traced, hunted down, etc.) and SARS IS A MYSTERIOUS ENTITY. In this way a whole web of metaphors is cast over a certain domain of discourse and gives it coherence and illocutionary force (see Koller, 2003).

UK SARS coverage

The UK press covered the SARS epidemic with varying degrees of interest. SARS was unquestionably a major news story, with particularly extensive coverage of Hong Kong, until recently governed by the UK, and Toronto. Many stories were, however, quite brief, and relied heavily on ‘human interest’ angles and government and WHO sources. One consequence of the importance of the WHO in setting the news agenda was the emphasis on scientific successes: this was a key area in which the WHO directed efforts, and it was one of the few aspects that involved major contributions from the UK and US. The media's combined emphasis on human interest and medical research and responses followed a pattern also apparent in the early coverage of other epidemics (Kinsella, 1989; Donovan, 1992).

Although the volume of media coverage of SARS in several countries has been shown to be correlated to case numbers (Chan, Jin, Rousseau, Vaughan, & Yu, 2003), the key concerns, priorities and emphases of the UK media coverage were nonetheless still closely related to the scale of the local threat (Kinsella, 1989: 156). Newspapers equivocated between presenting SARS as a major danger and dismissing it as a panic. Conscious and unconscious issues of language choice ran throughout this. The rumbling debate about the significance of SARS in part took the form of constant questioning about the appropriate epidemiological terminology for the outbreak: was it an epidemic, a pandemic, or neither? When, by May, it seemed unlikely that the UK would face an epidemic, coverage declined, despite the ongoing crisis in China. Even the Chinese threat to execute anyone who deliberately spread SARS received few mentions.

Much the UK reporting was instead concerned with stories about preventing SARS from reaching the UK. The four UK cases of SARS, and the suspected cases, received much coverage, as did boarding school quarantines. However, even these news strands were limited to arguments about how firmly the repertoire of traditional methods to control disease should be enforced. There was, for example, political debate about whether SARS should be a notifiable disease. But there was no equivalent to the heat of the vaccination versus slaughter debate of the FMD epidemic, despite some controversy in Toronto. It is significant that Vietnam had a major early success in controlling the epidemic using a quarantine-based approach. Indeed, conflict of any kind was limited: pressure groups were largely absent; there was no significant scientific debate about SARS in the public sphere, with few rival theories in the West to challenge the WHO laboratory network's conclusions. The other major local news themes in the UK press were SARS’ effect on tourism, sports, and the economy.

SARS and its metaphors

The English media's coverage of SARS employed two distinct and unusual sets of metaphors. One, of SARS as a Killer, was primarily used to discuss the characteristics and effect of the disease; the other, of Control, dominated discussions of responses to the disease. However, perhaps the most striking characteristic of the metaphorisation of SARS in the UK press was what was missing. In particular, war and plague, two metaphors that have played a very prominent part in framing other epidemics had marginal roles during SARS. These metaphors of war and plague are dealt with first below, before our discussion of the major conceptual metaphors that were employed.

Absent metaphors I: SARS wars

War metaphors are, as we have seen, one of the standard metaphor systems for disease in the West. Yet, during the SARS epidemic, they were only an occasional presence in media coverage. Even obvious war puns were neglected. ‘SARS Wars’ appeared only once—and then only because R2D2's inventor had built a ‘bug-buster’ robot. Where military metaphors were used, they tended to be limited in the scope they implied. For example, battle, rather than war, was generally used to describe responses to SARS, as when reporters described the WHO ‘battling’ against the virus. What makes this lack of war metaphors most striking is the coincidence between SARS and the Iraq war. Stories about SARS largely lacked connections to this war, or the ‘war on terror’. The only minor exceptions were when war and disease were given as explanations for economic problems, and when the suggestion was made that SARS might be the product of bioterrorism.

Although SARS was a relatively brief epidemic, language use was by no means static. As the epidemic unfolded, there were points when war metaphors did become slightly more common. In particular, from 21 April to 1 May, war metaphors appeared in greater numbers. Stories describe China on a ‘war footing’, ‘plans to combat the threat’, and ‘Armies of disinfection squads’. The Sun ran a series entitled: ‘On The SARS Frontline’ (28/4/03). This brief upsurge was linked to re-assessments the severity of the Chinese epidemic, emphasised on 23 April when the WHO added Beijing to its travel advisory list.

However, even as SARS seemed most serious, UK newspapers still only used war metaphors rarely. The Guardian employed a number on 24 April: ‘SARS fighting headquarters’, ‘Global battle against SARS panic’, ‘threat of infection’, the ‘most effective defence’, and ‘combat…the virus’. Yet these five instances came amidst six articles on SARS, plus additional references in other stories, all totalling over 7000 words. Extended clusters of linked war metaphors were still more uncommon. The Daily Mail was exceptional in a commentary on 26 April that discussed ‘old enemies’ who had once been ‘vanquished’, but were again ‘threats to humanity’, and warned:

‘the defeat of most infectious diseases is likely to be but temporary, or a victory in a skirmish rather than a final triumph in a war’.

It is striking that despite the employment of war metaphors to urge vigorous action by UK critics of the government's responses to SARS, such as Dr. Patrick Dixon of the London Business School, they declined even further in frequency during May.

The neglect of military metaphors was a local and contingent phenomenon. In other parts of the world military metaphors were heavily used. War metaphors were more prominent where the threat was immediate. The Chinese media and government, in particular, increasingly framed efforts against SARS as a war from late April. For example, the state news agency, Xinhua, reported about lessons learned ‘in fighting SARS’ (28/4/03). A few days later, the Communist Party was mobilised to ‘build a universal network to battle SARS’ (2/5/03). Comments from China occasionally led war metaphors to creep into the UK press: they lay behind the only uses of ‘war on/against SARS’ and ‘SARS war’ in the entire sample. The Taiwanese Prime Minister, Yu Shyi-kun's statement on 28 April that ‘Fighting the epidemic is like fighting a war. We face an invisible enemy’ had a similarly wide circulation. Members of the public from areas with SARS outbreaks also freely used war metaphors, as had occurred during the FMD epidemic in the UK in 2001:

‘It's like being in a war when you have to make sacrifices, give parts of your life up and do so many things differently. You feel you are under constant attack by an invisible enemy’ (28/4/03)

It seems that war metaphors are used more prominently when the relationship to the disease is either ‘personal’ or perceived as a threat to a ‘nation’. Foot and mouth disease in the UK and SARS in China fulfilled both criteria, whereas SARS in the UK did not.

Absent metaphors II: modern plagues

War metaphors were not the only obvious absence from the SARS coverage. SARS was also rarely identified as a plague, a metaphor that has been very important in framing AIDS (Cassens, 1985; Sontag, 1989; contrast Verghese, 2003). As well as owing something to the strength of the association between AIDS and plague, this plausibly reflects the various characteristics of the SARS epidemic—its speed, ease of transmission, low mortality, few external marks of infection, and lack of socially or nationally defined core of cases—that also helped limit the stigmatisation of the disease and its sufferers (Sontag, 1989). Nonetheless, certain aspects of the SARS story, particularly its pathological characteristics and symptoms, and assessments of its severity and likely trajectory, were embedded in an analogical framework of contemporary or historical epidemics.

At the most basic level, descriptions of SARS symptoms involved references to flu and pneumonia, as they did clinically. SARS was initially presented as ‘atypical pneumonia’ in WHO reports, a link reiterated in news reports about ‘mutant pneumonia’ and ‘killer pneumonia’. In contrast, references to flu or influenza provided a more limited impression of SARS’ severity, if not of its communicability.

Comparisons with diseases also dominated analyses of the severity of SARS and prognostications about its impact, as has been observed in other studies (Joffe & Haarhoff, 2002). The 1918/9 flu pandemic was the prime comparator. Contemporary flu epidemics were also referenced. For example, The Daily Mail argued that: ‘in comparison [with flu], this is a pinprick’. Other diseases, such as AIDS, appeared occasionally, and various people claimed that funding for SARS was excessive compared to the dearth of money for Malaria, AIDS, or even autism.

Often such comparisons formed part of either warnings of an imminent pandemic or dismissals of the disease, contrasting extremes of opinion. The uses of plague illustrate this. Plague was not referenced often, but when it did appear, writers took it as the benchmark of a severe epidemic, as though SARS must match plague to be taken seriously. For example, a letter on SARS in Toronto in the Guardian complained: ‘Yes, SARS is a presence in Toronto...but it is not the new black death’. In contrast, The Daily Mirror warned there was no certain ‘freedom from this latest modern plague’. This kind of disease comparison occurred to the near exclusion of alternative risk measurements.

Where disease patterns played their most ubiquitous role in the media coverage of SARS was, in fact, in a popularised language epidemiology. The visual language of mortality graphs was translated into roller-coaster imagery, in which cases soared until the epidemic was peaking, and then peaked; next, cases were falling, and they eventually petered out. The tracking of case-figures was, as this suggests, a major element of media coverage, due in part to this often being the only clear news hook for a story.

The killer virus

In the absence of military metaphors, SARS was not framed in non-violent, humanist or scientific language of the type some commentators have sought. Rather, the main conceptual metaphor used for SARS in the UK media was SARS IS A KILLER. This metaphor was particularly dominant in discussions of the nature, actions and impact of the disease. SARS was quickly labelled the ‘killer virus’, ‘killer plague’, or ‘deadly bug’. It ‘claims victims’, or simply kills people: ‘Eight more people were killed by SARS yesterday’. SARS has malevolent intentions: it ‘lingers’ on door handles, it ravages cities, it is ‘rampant’. It even has a ‘hit list’. ‘Victim’ was repeatedly used for those infected, at times in the tabloids almost to the exclusion of medical terms such as ‘patient’ or ‘infected’.

The Killer inspires fear in a supernatural manner that fits with conceptualisations of epidemics as nightmares (Nerlich, Hamilton, & Rowe, 2002): it is a ‘spectre’, it ‘struck fear into the market’ (Daily Mail, 25/4/03), it is a ‘chilling story’, it ‘unsettled companies’. It could be a criminal or a deadly animal, thereby incorporating the popular metaphor of CRIMINALS ARE ANIMALS. For example, ‘Killer Virus Bites Into Irish Profits’, or ‘the deadly SARS virus was on the loose’. The Killer metaphor system structured some reporting of responses to SARS, although far less than the metaphors of control discussed below. In particular, representing SARS as killer animal fitted with conceptions embedded in discourses of epidemiological investigation as hunting, used by public health bodies: scientists and governments tried to ‘hunt down’ or ‘track’ SARS.

There is, of course, an overlap between the Killer metaphor and traditional militaristic metaphors: both rely on an independent set of FORCE metaphors. In SARS, these suffused reporting even when Killer metaphors were absent. For example, fight was frequently used, and threat was also commonplace. The highly conventionalised language of fighting, almost dead metaphors, was ubiquitous in analyses of the effect of SARS. With things it could or did not kill, SARS was framed as a physical assault: it ‘slams’ shares, ‘hurt’ businesses, ‘hammered’ corporations, ‘knocked’ profits, ‘damaged’ states, and ‘gripped’ cities. Above all, SARS hit.1 It was ‘hitting’ regions, countries, companies, airlines, stock-markets, or the economy generally. Tourism was ‘the world's punchbag’; airlines were ‘SARS-battered’. As a result, SARS had an impact—the second most common term after hit. The same fight metaphors appeared regularly in descriptions of SARS’ physical impact on individuals. SARS is ‘attacking their lungs’, people are ‘struck down’, and ‘fighting to survive’. SARS is here conceptualised as a physical force. This metaphor is based on the ‘force schema’ (an image schema that involves physical or metaphorical causal interaction), one of the many image schemas that, according to Lakoff and Johnson (1980: 40), provide the embodied bases for conceptual metaphors.

Despite its similarities, the Killer metaphor system fundamentally differed from the military metaphor model. SARS as killer was a single, unified entity, not an army or force; it had no tactics, campaigns, or generals. This occurred despite the billions of individual viruses in those infected, and the existence of a number of distinct, localised outbreaks with recognised differences in severity, scale, and management. Despite the anthropomorphism, one result of this singularisation of the disease was its de-sexing, in a way that distinguishes it from standard post-Pasteurian understandings of microscopic life: only five stories refer to the virus breeding.

The Killer metaphor emerged quickly and persisted strongly in the UK media even though the number of deaths remained low in comparison to other recent epidemic diseases. The popularity of this metaphoric can be linked to two issues. Firstly, it neatly side-stepped ignorance about the disease, by eliding the mechanisms by which it spread and killed. But perhaps more importantly, it effectively conveyed the importance of a distant and unfamiliar epidemic: as this implies, it was particularly popular in tabloid headlines.

The problem of framing a novel danger about which little was known can also be seen behind several of the less prominent alternative metaphors used. The less moralistic concept of SARS as a ‘superbug’, ‘super-disease’, or ‘superflu’ occasionally featured in the tabloids, drawing on comparable images of disturbed nature (such as superweeds in the GM debate: Nerlich, Clarke, & Dingwall, 2000) to convey its seriousness, while locating SARS within another new pathological genre: the superbug, such as MRSA. Similar news values can also be recognised in the common early description of SARS as ‘jet bug’, a device which brings SARS nearer and ties it to affluence rather than foreign poverty; it was suggested initially by the WHO relating SARS’ spread to international flights. Comparable concerns about news value are manifest in the use of mystery metaphors (mysterious pneumonia’, ‘elusive virus’, or ‘mystery bug’), particularly in early broadsheet reports. Newspapers also used various common natural disaster metaphors to interpret SARS's progress on a global or regional scale. The most ubiquitous was SARS IS A FIRE (‘burns out’). Others included earthquakes (‘the disease's epicentre’), and, more rarely, volcanoes (SARS ‘erupted’) and storms (‘eye of SARS storm’). SARS was thus linked to historical images of the stalking mysterious killer, to exemplars of modernity, the jet-set age and globalisation, and to generic natural disasters. Strikingly, as with SARS IS A KILLER, all these metaphors were used in such a way that SARS was represented as a unified entity.

The level of threat SARS presented to the UK was one of the most important factors shaping metaphor usage in the UK media. This can be seen in the changes to the framing of responsibility that occurred when the disease seemed closer. The dominant Killer metaphor gave SARS an ‘active’ role. It was a free agent responsible for its actions; those it infects were passive, blameless victims. This pattern of responsibility differs from the emphasis on individual culpability apparent in the blame and stigma linked with AIDS, syphilis and some other diseases. However, where people infected with SARS threatened to bring the disease into the country an alternative metaphor system—DISEASE IS A POSSESSION—was often used, particularly in the tabloid press. In this metaphorical schema, people catch, carry, pick up, get, have, bring, acquire or contract disease, which is a burden they have got, and can give or pass on to others, unless they are relieved of it or have it taken away. It emphasises individual culpability in disease. In the SARS coverage, it blended with similarly valenced grammatical forms, in which the sick person became the active agent in their illness (person X becomes or falls ill; is or becomes infected with or by Y). A good example is The Daily Mail report on the ‘First Briton to get ‘flu’ killer bug in the UK’: a person who ‘contracts’ SARS, and ‘becomes infected’, although the virus remains a ‘killer’ (14/4/03). Other newspapers used headlines such as: ‘Fifth Briton Brings Home Deadly Virus’, and ‘Nurses In Alert’ “Not Likely” To Have SARS’. Thus, when SARS became an immediate threat the ‘victim’ became a ‘carrier’ or ‘case’: a danger, rather than an object of compassion.

This situation with its metaphors of blame aside, the metaphors used for SARS decentred and stripped it of local identity. Some of the metaphors used, such as epicentre and spread, have been criticised for distancing epidemics and encapsulating blame, but this seems not to have occured for SARS (Reid, 1994). Early in the epidemic, it was rare to find references to SARS having a centre, heart, or core. Without knowledge of its origins, and with doubts about events in China, SARS had borders but no obvious middle for much of March and April. It was from the outset a disease of many places. In this lay its threat. The most obvious symptom of this was the lack of a localising name, such as West Nile Fever or Lyme Disease. SARS was virtually never framed as Hong Kong syndrome or Guangdong flu. With the exception of a brief flurry in late March of ‘flu-variant’ names (e.g.: ‘Hong Kong Flu’), SARS escaped a hierarchy of severity—and of blame.

By late April, this situation was changing. SARS seemed to be limited to a well-defined set of locations—Beijing, Hong Kong, Toronto, Guangdong. Now descriptions of centres became more common, although never frequent. For example, Toronto is ‘the epicentre of the worst SARS outbreak outside Asia’ (28/4/03). A few journalists even ventured to re-label SARS as a regional or Chinese problem.

The weak ties between SARS and a specific locality attenuated its ‘origin narrative’ (King, 2002: 773) and probably helped limit the stigmatising of social, national or racial groups as ‘SARS risks’ in the UK. There were some incidents of panic or hostility. Some school-children returning from Asia were driven from a Blackpool hotel by a ‘SARS Panic Mob’. A Scottish shop-keeper shut his shop after a ‘false SARS alert’ led customers to treat him ‘like a “leper”’. These were, however, faint echoes of the anxiety and antagonism that people with SARS faced in countries with epidemics. In contrast to suggestions that SARS was quickly identified and defused by ‘othering’ through identification as a Chinese disease (Washer, 2004), we found that in the broader sample we analysed SARS was only weakly identified as a problem of a definable ‘other’. In this, the social profile of SARS cases, clustered in hospitals and among the middle class, no doubt played a part. Only when links with Chinese food markets emerged towards the end of the epidemic did SARS begin to be connected to poverty and dirt.

To the extent that stigmatisation of potential SARS carriers occurred in the UK, it centred on people of Chinese ethnicity. A few stories appeared about people avoiding Chinatown restaurants in late April, and on universities ‘accused of racism’ for treating Chinese students as threats in early May. Most journalists seem, however, to have been more interested in shaming anyone they thought was indulging in discrimination or xenophobia than in reinforcing such perceptions—perhaps a small pay-off from the way in which AIDS has underlined the relationship of disease, stigma and marginalisation. The Guardian's review of a Horizon documentary, for example, accused it of suggesting that SARS spread ‘because… the Chinese were dirty’, that the WHO's efforts were thwarted by Chinese lies, and that ‘After the dirty liars owned up, SARS was identified’ (30/5/03). The only exception was The Daily Mail, which used SARS in its campaign against immigration and refugees, as did the right-wing anti-immigrant British National Party. However, the repeated reliance on images of groups of masked Chinese people to illustrate SARS stories may have undermined the media's avoidance of stigmatising labelling by conveying the message that it was the problem of a particular group who were, moreover, depersonalised and made passive by the mask.

Controlling and responding to SARS

The national and international response to SARS was, to a degree, framed in the same ways as the effects of the disease itself. Although as we saw above, killer and natural disaster metaphors had their place, metaphors of physical struggle were most successful at crossing this boundary. For example, some people and countries ‘faced up to SARS’ or tried to ‘tackle [the] outbreak’. The entire enterprise of responding to SARS was sometimes interpreted as a fight. The WHO, for example, was ‘set to lead the fight against killerbug SARS’ and then ‘had trouble fighting the SARS virus’.

The fight against SARS was, however, only one way of framing institutional and political responses to the disease. More common were metaphors of Control that tactically validated a more politically and economically moderate approach. In descriptions of global or local situations, these significantly outweighed uses of the Killer, Natural Disaster, and Bodily Struggle metaphors. Reports of governments’ and international organisations’ actions thus framed the disease as a problem, crisis or disaster. SARS was successively a ‘major problem’, ‘spreading out of control’, or already ‘out of control’.

Beyond this dyad of controlled/uncontrolled, these efforts were often framed through simple CONTAINER schemas (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980: 51), which were particularly relevant to ideas of disease spread. However, unlike AIDS discourse in which, as Julia Epstein (1992) has shown, the key boundaries are the edges of the physical bodies of the infected and the margins between the ‘general population’ and ‘high-risk’ groups, the crucial container mapping in SARS discourse was over a more extended physical space—towns, cities, regions, and countries. While the ‘SARS body’ was characterised visually by the sterile, masked, anonymous traveller, their mouth and nose tightly covered, the ‘SARS space’ was leaky and permeable, dripping with contagion, much as AIDS bodies were often conceptualised in the 1980s and early 1990s (Weiss, 1997: 464). Reports warned that ‘there is a danger that it could spill out of urban areas’ and described a ‘desperate bid to contain’ SARS; expatriates recounted ‘seeing a vague threat boil over into crisis’.

When governments and the WHO sought to control SARS, they did so through actions that were often described in a language of depersonalised bureaucratic cliché that echoed discourses of environmental management or urban improvement in its disregard for human costs. The media reported on measures, regulations, restrictions, controls, efforts, approaches, handling, or dealing. The bloodlessness of this vocabulary meant that it constantly demanded qualification in news reports to alleviate its rhetorical weakness and emphasise the seriousness of states’ actions. Thus, articles noted: ‘stringent measures’, ‘strict controls’, and ‘draconian public health measures’.

In adopting the discourse of control and bureaucratic action, the media followed the WHO and UK government language from the outset. WHO press releases consistently discussed investigations, containment, measures, and responses.2 Both UK government and opposition politicians debated public health measures and a ‘proportionate approach’.3 Similar use was made of this discourse in China. On 29 April, for example, the Chinese Prime Minister announced measures to have SARS ‘brought under control’. Framing responses to SARS in a discourse of bureaucratic control drew on a long tradition in which public health as ‘medical police’ is a function of the civil state similar to the other kinds of ‘policing’ it carries out (Jordanova, 1980; Porter, 1999). Ideas of police ran throughout the limited repertoire of traditional public health techniques used to halt SARS. Quarantines of the infected and their contacts, and surveillance of travellers were the two most important methods used against SARS, with travel bans imposed by some countries.4 The relationship to policing was clear: governments promised ‘to hold victims’, ‘detain SARS sufferers’, identify ‘those suspected of harbouring the virus’. They also praised ‘good detective work’ by scientists.

This conceptualisation of SARS through control and bureaucratic action did not actively conflict with the Killer metaphoric. Indeed, it fitted well with the animal variant of this. However, it did hold out more limited prospects for the eventual outcome of the epidemic. A killer could be hunted, captured or exterminated, just as a war ultimately leads to victory or defeat. The language of control offered a more limited and defensive image of restraining the disease. It implied the authorities might curtail its movement and reach, but perhaps not remove it from the world.

Conclusion

The UK media coverage of SARS was framed through the use of a limited set of metaphors which tended to be restricted to particular issues. Two systems were particularly important. A Killer metaphor system was commonly used to discuss the nature of SARS, its local and human impact, and individual responses. The institutional and national impact of SARS and the responses it elicited were largely framed through a bureaucratic discourse of management and a balance metaphor-dyad of controlled/uncontrolled. Struggle metaphors were also heavily used to describe the human and economic impacts of SARS; a range of other metaphors and analogical frames appeared occasionally. Overall, these metaphors and historical framings were limited, fragmented and somewhat hackneyed. They are a marked contrast to the richness of writing and reporting required to explain more novel scientific, medical or natural events such as clones or invasive species (see Nerlich, Clarke, & Dingwall, 1999; Larson, Nerlich, & Wallis, forthcoming).

The disarticulation of these different aspects of the SARS metaphor system offers a striking contrast with AIDS, where plural and overlapping metaphors, of war, plague, pollution, sin and the like, tended to be extensive rather than localised, permeating discussions of both disease and policy. For example, AIDS as sin was employed to describe cause (divine judgement), attitude to sufferer (sinner), and individual and public policy responses (repentance, abstinence, moral education). By contrast, the metaphor system we have described shares some characteristics with patterns identified in coverage of Ebola and other analyses of SARS (Unger, 1998; Washer, 2004). Unger has identified a shift in Ebola coverage from a ‘mutation-contagion’ package, the content of which includes the story aspects we found most closely related to the Killer metaphor system, to a ‘containment’ package, which has parallels to the bureaucratic control discourse we discuss. However, where Unger and Washer interpret this as a single news discourse that frightens then reassures, we find that the two metaphor systems co-exist in parallel, serving quite separate needs and prompted by different sources and intentions (see also Joffe & Haarhoff, 2002).

There has been some debate over the degree to which metaphors of disease tend to be contradictory (Weiss, 1997; Gibbs & Franks, 2002). In this case, the conflict is clear, but is the result of the structural context rather than psychology. The existence of different metaphor systems used in the description of specific aspects of SARS can be understood as intimately related to tensions between public concerns and anxieties surrounding the disease entity, the habitual pressures on the media to convey the news values of stories, and the limits on political and public health options and governments’ willingness to act. Several aspects of this relationship are particularly clear from the analysis above. News values are most obvious in the prominence of the ‘SARS Killer’ metaphor system and the alternate disaster metaphors, and in the striking shift to DISEASE IS A POSSESSION metaphors when SARS seemed most threatening. More suggestive and surprising is the media's avoidance of overt marginalisation, where feedback from AIDS coverage may be having an effect. The relationship between governmental responses and the media coverage is at one level more direct, as is apparent from journalist's reiteration of bureaucratic control metaphors employed initially in government and WHO briefings. However, it also may be fundamentally related to the striking lack of militaristic metaphors. This seems to contradict research into the use of ‘media templates’ or the use of standard narrative and metaphorical conventions that structure the media reporting of medical issues (see Kitzinger, 2000; Miller, Kitzinger, Williams, & Beharrell, 1998; Seale, 2003) and therefore needs some explanation.

The glaring absence from SARS coverage was the militaristic metaphors that have long been seen as prime features of discourses of bioscience and disease. The immediate context of war in Iraq may have played a part in this, pushing commentators to create distinctive discursive systems for the two stories. However, three aspects of the development of SARS as a political issue made it particularly unsuitable for framing as a war. First, the international response to SARS lacked a ‘general’ as SARS’ rapid transmission to several countries meant it was not ‘owned’ by any single originating nation. The closest thing to a leader was the WHO. However, it faced tight limits as an advisory and coordinating institution, and the difficulties it experienced in negotiating access to China made it essential for it to avoid claiming authority over affected countries. Consistently, the WHO presented itself as ‘working with’ or ‘supporting’ national authorities in a ‘collaborative effort’ and ‘partnership’. This also meant that there was no point at which war on SARS was declared. Second, in the UK, SARS was largely a distant, international story. The UK government needed to avoid panic, not call on national solidarity or quash dissent—both areas where militaristic metaphors can help. Third, the effort against SARS did not promise to end in a clear victory. Framing SARS as a problem of control reflected a general uncertainty which AIDS has fostered about the effect that governments can have on epidemic diseases. The aspiration to contain, rather than eradicate, SARS, lacks the optimism of the war on cancer of the 1960s and 1970s.

SARS is unlikely to represent a milestone in some discursive retreat from the war metaphoric. War will no doubt continue to dominate the discourses of the intimate aspects of human disease encounters. Nevertheless, the neglect of war metaphors in the coverage of SARS indicates that they are more flexible than some arguments for their cognitive and cultural dominance imply. It also suggests they are rather less ‘dead’ than has been argued by those, such as Richard Gwyn, who have taken their ubiquity to imply a loss of ‘metaphoric currency’ (Gwyn, 2002: 131). SARS does, of course, make clear that alternative framings are possible. However, as the prominence of an equally bloody Killer metaphor suggests, they are unlikely to take the appealing forms some have sought.

SARS may, however, reflect some characteristics of the framing of globalized issues. SARS highlights the role of international organisations in driving news agendas on some kinds of international issues. In the current geopolitical situation, few if any such institutions can claim a genuine directorial role or possess any significant resources of their own, in the manner of national governments. They function as advisory, regulatory, coordinating bodies, and rely on the unenforceable goodwill of national governments to achieve their goals. This in turn affects the metaphorical framing of international ‘problems’ and induces the bureaucratic, managerial approach which can be seen in the SARS discourse in place of more energetic war metaphor systems. Understanding this shift in metaphorical framing, away from the well-entrenched metaphor system of war and plague, might not only signal a shift in the perception and policing of an emergent disease, but can also contribute to an emerging shift in the theorising of metaphor itself, away from seeing it purely as a rhetorical or cognitive device towards seeing it as a cultural and political one. As Bono has suggested: ‘such cultural [scientific] metaphors adapt themselves to a larger ecology of contesting social and cultural values, interests and ideologies’ (1990: 81).

Acknowledgements

Research for this paper was funded by the Leverhulme Trust. We would like to thank Emma Callow for her excellent research work on this project. Thanks also to all those who have provided helpful comments and feedback on this paper, especially Anja Minnich, Arran Stibbe and Pru Hobson-West.

Footnotes

This is reflected in word frequency within the corpus. Within SARS stories, hit (477 uses) was far more common than any alternative terms: strike (133), impact (128) blow (65), grip (39), knock (30), struck (10), hammer (9). Note: These counts do not distinguish between whether or not the word was being used specifically with relationship to SARS.

WHO press releases are available at: http://www.who.int/csr/sars.

Parliamentary debates on SARS occurred on the 26 March and 28 April 2003: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/.

It is worth noting that the US Centres for Disease Control did attempt to define their quarantine provisions as ‘modern’ quarantine, in contrast to the unpopular traditional quarantines: CDC press releases, 2 April 2003.

References

- Annas G. Reframing the debate on health care reform by replacing our metaphors. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332(11):744–747. doi: 10.1056/nejm199503163321112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo B.A. Martial metaphors and medical justice: implications for law, crime, and deviance. Journal of Political and Military Sociology. 1999;27(2):307–322. [Google Scholar]

- Bono J. Science, discourse, and literature: the role/rule of metaphor in science. In: Peterfreund S., editor. Literature and science: theory and practice. Northeastern University Press; Boston: 1990. pp. 59–89. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt A.M. AIDS and metaphor: toward the social meaning of epidemic disease. Social Research. 1988;55(3):413–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassens B.J. Social consequences of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1985;103(5):768–771. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-5-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan L.C.Y., Jin B., Rousseau R., Vaughan L., Yu Y. Newspaper coverage of SARS: a comparison among Canada, Hong Kong, Mainland China and Western Europe. Cybermetrics. 2003;6/7(1) [Google Scholar]

- Charteris-Black J. Palgrave Macmillan; London: 2004. Corpus approaches to critical metaphor analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Clow B. Who's afraid of Susan Sontag? or, the myths and metaphors of cancer reconsidered. Social History of Medicine. 2001;14(2):293–312. doi: 10.1093/shm/14.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox News Service. (2002, 4 April). 30 Years of War on Cancer. Retrieved 12 March, 2004, from http://www.amprogress.org/Files/Files.cfm?ID=382&c=68.

- Deignan A. Corpus-based research into metaphor. In: Cameron L.J., Low G.D., editors. Researching and applying metaphor. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1999. pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan P. High noon in Bethesda: medicine, newsweeklies, adn the early phase of the AIDS epidemic. Proteus. 1992;9(2):11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Drass K.A., Gregware P.R., Musheno M. Social, cultural, and temporal dynamics of the AIDS case congregation: early years of the epidemic. Law and Society Review. 1997;31(2):267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein J. AIDS, stigma and narratives of containment. American Imago. 1992;49(3):293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Fox R.C., Swazey J.P. He knows that machine is his mortality: old and new social and cultural patterns in the clinical trial of the AbioCor artificial heart. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2004;47(1):74–99. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2004.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs R.W., Franks H. Embodied metaphor in women's narratives about their experiences with Cancer. Health Communication. 2002;14(2):139–166. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1402_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore N., Somerville M.A. Stigmatization, scapegoating and discrimination in sexually transmitted diseases: overcoming ‘them’ and ‘us’. Social Science & Medicine. 1994;39(9):1339–1358. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradmann C. Invisible enemies: bacteriology and the language of politics in Imperial Germany. Science in Context. 2000;13(1):9–30. doi: 10.1017/s0269889700003707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwyn R. Sage; London: 2002. Communicating health and illness. [Google Scholar]

- Hughey J.D., Norton R.W., Sullivan-Norton C. Insidious metaphors and the changing meaning of AIDS. AIDS and Public Policy Journal. 1989;4(1):56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe H., Haarhoff G. Representations of far-flung illnesses: the case of Ebola in Britain. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;54(6):955–969. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordanova L. Medical police and public health: problems of practice and ideology. Bulletin of the Society for the Social History of Medicine. 1980;27:15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N.B. Security, disease, commerce: ideologies of post-colonial global health. Social Studies of Science. 2002;32(5/6):763–790. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella J. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 1989. Covering the plague: AIDS and the American media. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger J. Media templates: patterns of association and the (re)construction of meaning over time. Media Culture and Society. 2000;22(1):61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Koller, V. (2003). Metaphor clusters, metaphor chains: analyzing the multifunctionality of metaphors in text. Metaphorik. de 5. Retrieved December 2, 2003 from: www.metaphorik.de/05.

- Lakoff G., Johnson M. Chicago University Press; Chicago: 1980. Metaphors we live by. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, B., Nerlich, B., & Wallis, P. (forthcoming). Metaphors and Biorisks. Science Communication.

- Lerner B.H. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. The breast cancer wars: hope, fear, and the pursuit of a cure in twentieth-century America. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D., Kitzinger J., Williams K., Beharrell P. Sage; London: 1998. The circuit of mass communication: media strategies, representations and audience reception in the AIDS crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery S.L. Codes and combat in biomedical discourse. Science as Culture. 1991;2(3):341–390. [Google Scholar]

- Nations M.K., Monte C.M.G. “I’m Not Dog, No!”: cries of resistance against cholera control campaigns. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;43(6):1007–1024. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerlich B. Towards a cultural understanding of agriculture: the case of the ‘war’ on foot and mouth disease. Agriculture and Human Values. 2004;21(1):15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nerlich, B., Clarke, D.D., & Dingwall, R. (1999). The influence of popular cultural imagery on public attitudes towards cloning. Sociological Research Online 4(3), Retrieved December 2, 2003 from http://www.socresonline.org.uk/socresonline/4/3/Nerlich.html.

- Nerlich B., Clarke D.D., Dingwall R. Clones and crops: the use of stock characters and word play in two debates about bioengineering. Metaphor and Symbol. 2000;15(4):223–240. [Google Scholar]

- Nerlich, B, Hamilton, C., & Rowe, V. (2002). Conceptualising foot and mouth disease: the socio-cultural role of metaphors, frames and narratives. Metaphorik.de, 2, http://www.metaphorik.de/02/nerlich.htm.

- Norton R., Schwartzbaum J., Wheat J. Language discrimination of general physicians: AIDS metaphors used in the AIDS crisis. Communication Research. 1990;17(6):809–826. doi: 10.1177/009365029001700606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton C. Routledge; New York, London: 1990. Inventing AIDS. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Porter D. Routledge; London: 1999. Health, civilisation and the state: a history of public health from ancient to modern times. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid E. Approaching the HIV epidemic: the community's response. AIDS Care. 1994;6(5):551–557. doi: 10.1080/09540129408258669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins J. AIDS, law, and the rhetoric of sexuality. Law and Society Review. 2002;36(1):161–192. [Google Scholar]

- Ross J.W. Ethics and the language of AIDS. Federation Review. 1986;9(3):15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sandahl C. Performing metaphors: AIDS, disability, and technology. Contemporary Theatre Review. 2001;11(3–4):49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Seale C. Sporting cancer: struggle language in news reports of people with cancer. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2001;23(3):308–329. [Google Scholar]

- Seale C. Health and media: an overview. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2003;25(6):513–531. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.t01-1-00356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin S. Feminist ethics and the metaphor of AIDS. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy. 2001;26(4):343–364. doi: 10.1076/jmep.26.4.343.3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontag S. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; New York: 1978. Illness as metaphor. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag S. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; New York: 1989. AIDS and its metaphors. [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell P. Towards a critical cognitive linguistics. In: Combrink A., Bierman I., editors. Discources of war and conflict. Potchefstroom University Press; Potchefstroom, South Africa: 1999. pp. 510–528. [Google Scholar]

- Treichler P.A. AIDS, HIV, and the cultural construction of reality. In: Herdt G., Lindenbaum S., editors. The time of AIDS: social analysis, theory, and method. Sage; London: 1992. pp. 65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Turner M. Oxford University Press; New York, Oxford: 2001. Cognitive dimensions of social science. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Unger S. Hot crises and media reassurance: a comparison of emerging diseases and Ebola Zaire. British Journal of Sociology. 1998;49(1):36–56. [Google Scholar]

- Verghese A. The SARS epidemic: the metaphor of blight. Wall Street Journal. 2003;241(93):A18. [Google Scholar]

- Washer P. Representations of SARS in the British newspapers. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59(12):2561–2571. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M. Signifying the pandemics: metaphors of AIDS, cancer, and heart disease. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1997;11(4):456–476. doi: 10.1525/maq.1997.11.4.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worboys M. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2000. Spreading germs: disease, theories, and medical practice in Britain, 1865–1900. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (2003, 27 Nov). Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome: Report by the Secretariat. Retrieved 4 April, 2004, from http://www.who.int/gb/EB_WHA/PDF/EB113/eeb11333.pdf.

- World Health Organisation. (2003, 31 Dec). Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. 31 Dec 2003. Retrieved 4 April, 2004, from http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/.

Further reading

- Helman C.G. 4th ed. Arnold; London: 2000. O1_MRKO1_MRKCulture, health and illness. [Google Scholar]