Graphical abstract

A new 18s rDNA based primer set found to be more effective for diagnosis of symptomatic falciparum malaria. Introduction of Hydroxy Napthol Blue has improved visual detection.

Keywords: Malaria, Plasmodium falciparum, LAMP, Hydroxy napthol blue, Bangladesh

Highlights

-

•

Introduction of Hydroxy Nepthol Blue (HNB) has lead easy and simple naked eye visualization of the LAMP amplicons.

-

•

The new primer set was found to be 99.1% sensitive and 99% specific in comparison with microscopy.

-

•

In comparison with Real Time PCR, sensitivity was 98.1% along with 100% specificity.

-

•

This new method can detect at least five parasite per μL of blood.

Abstract

Molecular diagnosis of malaria by nucleotide amplification requires sophisticated and expensive instruments, typically found only in well-established laboratories. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) has provided a new platform for an easily adaptable molecular technique for molecular diagnosis of malaria without the use of expensive instruments. A new primer set has been designed targeting the 18S rRNA gene for the detection of Plasmodium falciparum in whole blood samples. The efficacy of LAMP using the new primer set was assessed in this study in comparison to that of a previously described set of LAMP primers as well as with microscopy and real-time PCR as reference methods for detecting P. falciparum. Pre-addition of hydroxy napthol blue (HNB) in the LAMP reaction caused a distinct color change, thereby improving the visual detection system. The new LAMP assay was found to be 99.1% sensitive compared to microscopy and 98.1% when compared to real-time PCR. Meanwhile, its specificity was 99% and 100% in contrast to microscopy and real-time PCR, respectively. Moreover, the LAMP method was in very good agreement with microscopy and real-time PCR (0.94 and 0.98, respectively). This new LAMP method can detect at least 5 parasites/μL of infected blood within 35 min, while the other LAMP method tested in this study, could detect a minimum of 100 parasites/μL of human blood after 60 min of amplification. Thus, the new method is sensitive and specific, can be carried out in a very short time, and can substitute PCR in healthcare clinics and standard laboratories.

1. Introduction

Accurate diagnosis of malaria is important for controlling the disease as well as for limiting the increase in drug resistance (Murray and Bennett, 2009). Almost half of the world's population, residing in 106 countries, is under the threat of malaria, but one of the impediments to more universal diagnosis of malaria is the associated cost (Murray and Bennett, 2009).

Microscopy is still considered the gold standard for diagnosing malaria, though it is difficult to implement due to lack of expertise. However, its sensitivity and specificity is limited at about 80–90%, even in the best of settings (Reyburn et al., 2006). Because of the limitations of microscopy, rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) were implemented for malaria diagnosis in healthcare and research. Despite their significant contribution in the diagnosis of malaria because of the ease with which they can be performed, RDTs have several limitations, such as cross-reactivity with heterophile antibodies and rheumatoid factors, false positivity due to a previous infection, and decreased sensitivity in some instances, especially in the case of lower parasite densities (Wongsrichanalai et al., 2007). On the other hand, genetic diversity and deletion of histidine rich protein 2 (HRP2) can lead to false-negative diagnosis, especially in Peruvian cases of Plasmodium falciparum, which lack HRP2 and HRP3 (Baker et al., 2005, Gamboa et al., 2010). Furthermore, failure to maintain the expected quality in each production cycle and the inability to monitor treatment follow-up have made RDTs unreliable in some instances (Alam et al., 2011, Murray and Bennett, 2009, Wilson, 2012).

Conversely, molecular methods such as PCR and real-time PCR are more sensitive and can detect 1–5 parasites/μL of blood in some instances. But these methods are very expensive, require sophisticated instruments, and are feasible only in well-established laboratories with proper technical expertise (Mohon et al., 2012).

Notomi et al. (2000) described a novel DNA amplification method named loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). In this method, a specific fragment of DNA can be amplified in heat block without a thermal cycler, which can be too expensive for PCR application in the field. Four specially designed primers and two additional loop forming primers amplify the target DNA with a large fragment of Bst polymerase, which has exclusive strand displacement activity in the LAMP method. Immense amplification leads to accumulation of magnesium pyrophosphate, which turns the solution turbid; this turbidity is visible to the naked eye or can be measured with a turbidity meter (Notomi et al., 2000).

Eventually, LAMP has attracted great interest from a number of investigators worldwide. Consequently, several diagnostic methods were implemented for protozoan parasite detection (Mori and Notomi, 2009) as well as malaria (Abdul-Ghani et al., 2012). Poon et al. (2006) first reported the use of LAMP for the diagnosis of clinical malaria caused by P. falciparum; later, Han et al. (2007), using primers targeting an 18S rNA gene, implemented genus- and species-specific LAMP for the diagnosis of four Plasmodium species that infect humans. Polley et al. (2010) reported better sensitivity of LAMP than earlier methods using primers designed for targeting mitochondrial DNA.

Despite these developments, visual detection of the LAMP product requires practical skill, and individual variation occurs in detecting positive reactions, especially in the setting of lower copy numbers of template DNA (Goto et al., 2009). Furthermore, a turbidity meter or fluorescent reader or portable fluorescence reader increases the cost and the number of instruments required. Post-addition of SYBR Green requires opening of the reaction tubes, which may lead to severe contamination in the laboratory, whereas pre-addition to the reaction mixture inhibits the amplification reactions. Pre-addition of Calcein with MnCl2 can surmount the problem of contamination, but it does not lead to significant development in the visual system (Goto et al., 2009). Moreover, cost is a big constraint in using SYBR Green and Calcein in LAMP visualization. Goto et al. (2009) introduced the concept of pre-addition of hydroxy naphthol blue (HNB), a cheap and easily visible dye in the reaction mixture, that does not inhibit the amplification. Massive amplification produces a pyro-phosphate by-product that precipitates with Mg2+ ion in the solution. In this process, HNB, the magnesium-chelating dye, loses its bound magnesium to provide magnesium to pyrophosphate, which has stronger affinity to magnesium than HNB. Consequently, absorption and emission spectra of the HNB complex are altered. Eventually, the color of the reaction mixture changes from violet to sky blue. Moreover, HNB provides a detection threshold similar to that provided by SYBR Green (Goto et al., 2009). Consequently, several LAMP-based methods were developed using HNB for the diagnosis of various targets such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, coronavirus, trypansomes, and influenza H1N1 (Cardoso et al., 2010, Grab et al., 2011, Hong et al., 2012, Ma et al., 2010).

In this study, HNB was introduced for the visualization of LAMP turbidity, and a new primer set was designed and its efficacy was compared with the primer set described by Poon et al. (2006) to detect P. falciparum in clinical samples using real-time PCR and conventional microscopy as reference methods.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Samples

The study area and sample collection procedures were described previously (Alam et al., 2011). The study samples included 106 microscopy-positive P. falciparum monoinfection and 105 microscopically negative samples. All the subjects had febrile illness and were suspected of malaria.

2.2. Microscopy

Thick and thin smear slides were prepared in duplicate using two drops of blood for each sample. Microscopy was performed by experienced microscopists according to WHO standard procedures, as described elsewhere (Alam et al., 2011).

2.3. DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from 200 μL preserved whole blood using the QiaAmp blood mini kit (Qiagen GmbH, Germany) following manufacturer's instructions.

2.4. Real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was done on extracted DNA according to the procedure described by Alam et al. (2011) using Invitrogen™ SYBR Green I supermix UDG (Life Technologies Corporation, USA).

2.5. LAMP method

Initially, the LAMP method was carried out following the protocol and primer set described by Poon et al. (2006), although pre-addition of 120 μM HNB was introduced in the reaction mixture. 2 μL of extracted DNA was used as the template for amplification. The tubes were heated at 60 °C for 60 min.

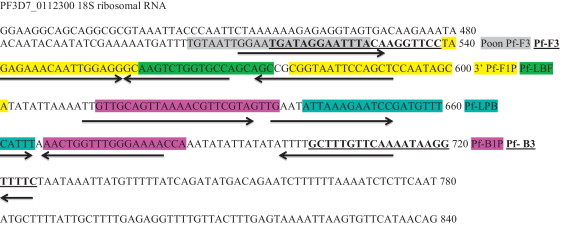

A slightly different region in the 18S rRNA gene of P. falciparum 3D7 type was selected using the NCBI-BLAST tool. Primers were designed with Primer Explorer V4: an online primer-designing tool (http://primerexplorer.jp/elamp4.0.0/index.html) developed by Eiken Chemical Co. LTD, Japan. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1 and Fig. 1 .

Table 1.

List of primers and sequence.

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| Pf-F3 | TGATAGGAATTTACAAGGTTCC |

| Pf-B3 | GAAAACCTTATTTTGAACAAAGC |

| Pf-F1P | TGCTATTGGAGCTGGAATTACCGTAGAGAAACAATTGGAGGGC |

| Pf-B1P | GTTGCAGTTAAAACGTTCGTAGTTGTGGTTTTCCCAAACCAGTT |

| Pf-LPF | GCTGCTGGCACCAGACTT |

| Pf-LPB | ATTAAAGAATCCGATGTTTCATTT |

Fig. 1.

Overlap of the LAMP primer sets on the PF3D7_0112300 18S rRNA gene. The new forward primer begins after the initial 11 nucleotides of the Poon et al.’s forward primer. The reverse primer Pf-B3 are identical. The other new primers, which are underlined, are shifted from the Poon et al.’s corresponding primers by 4–10 nucleotides.

For the newly designed primer set, a 2X reaction mixture was prepared comprising 40 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.8), 20 mM (NH4)2SO4 (pH 8.8), 20 mM KCl, 16 mM MgSO4, 1 M betain, 2.4 mM each of the DNTPs, 120 μM HNB, and 0.01% Tween 20. The primer mixture was prepared with 2.4 μM of F1P and B1P, 0.6 μM of LPF and LPB, and 0.2 μM of F3C and B3 primers. All reactions were carried out in 25 μL tubes using 2 μL of template DNA, 12.5 μL 2X reaction mixture, 9.5 μL of primer mixture, and 1 μL (8U) of Bst polymerase. All tubes were heated at 60 °C for 40 min in a heat block.

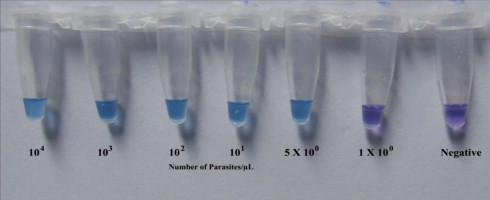

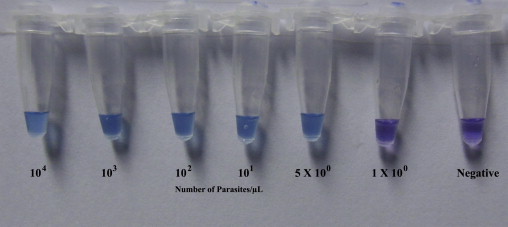

Changes in the color of the reaction mixture for both LAMP methods were observed by the naked eye. The color of the mixture in the tubes containing detectable amount of P. falciparum DNA changed from violet to sky blue (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Visualization of the LAMP reaction using HNB. The color changes from violet (negative reaction) to sky blue (positive reaction).

In order to set the reaction time, initially LAMP was carried on serially diluted DNA samples with parasitemia of 10000, 1000, 100, 10, 5, and 1. Each sample was amplified for five rounds. In each round of assay, reactions with 5 parasites/μL template DNA was amplified and changed the color within 30–32 min. Sometimes reactions with 1 parasite/μL template DNA were amplified within approximately 35–36 min. Incubation for longer duration did not show any color change. Therefore, 40 min was chosen as the reaction time.

2.6. Analytical sensitivity and specificity

Two confirmed microscopically positive P. falciparum samples were selected and slides were analyzed by three independent microscopists. Parasitemia were calculated according to WHO standard procedures. The average parasite count was calculated using three independent results from each microscopist for each of the sample. These samples were diluted with a healthy negative control blood sample to establish the parasitemia of 10000, 1000, 100, 10, 5, and 1 parasite/μL. Then DNA was extracted and LAMP reactions were carried out on the DNA of the diluted samples for five rounds following the procedures described above.

A negative control panel was made available comprising of 20 P. vivax, 3 P. malariae, 10 Leishmania donovani, and 10 M. tuberculosis positive blood samples and DNA was extracted. The infection status of the samples was confirmed by PCR. Then LAMP reaction was carried out to assess the cross-reactivity of the newly designed primers with this set of nonmalaria microbial DNA in blood.

2.7. Data analysis

All data were analyzed in STATA version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station Texas, USA). Sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and accuracy were calculated with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) by the McNemar test and exacted by the same test using the ‘diagt’ command.

2.8. Ethical approval and anonymity

The study was approved by the Institutional Research Review Committee (RRC) and Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of icddr,b. A written consent was obtained from all adult subjects and from the legal guardians in the case of minor subjects prior to the collection of blood samples. Anonymity was maintained at every step of the research procedure.

3. Results

3.1. Microscopy and real-time PCR

All of the 106 microscopy-positive samples were also found positive by P. falciparum-specific real-time PCR. On the contrary, among the 105 microscopy-negative samples, two tested positive for P. falciparum by real-time PCR (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Comparison of the two LAMP methods with microscopy and real-time PCR.

| Test | Result | Microscopy |

Real-time PCR |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| Poon et al.’s LAMP | Positive | 102 | 2 | 103 | 1 |

| Negative | 4 | 103 | 5 | 102 | |

| New LAMP | Positive | 105 | 1 | 106 | 0 |

| Negative | 1 | 104 | 2 | 103 | |

3.2. Limit of detection and specificity

The LAMP primers described by Poon et al. (2006) detected a minimum of 100 parasites/μL in each of the five rounds of amplification within 60 min. No alteration in the initial color was observed after heating the samples for up to 90 min. Conversely, LAMP with newly designed primers successfully detected 5 parasites/μL within 35 min in each of the five amplification rounds. Additional heating to 60 min resulted in the detection of 1 parasite/μL in two of the five rounds of amplification.

All the 43 samples in the negative panel of P. vivax, P. malariae, L. donovani, and M. tuberculosis tested negative by both of the LAMP primer sets. Thus, analytical specificity with this panel was 100% for both primer sets.

3.3. Clinical sensitivity and specificity

Following pre-addition of HNB, LAMP with the primer set described by Poon et al. (2006) had a sensitivity of 96.2% (95% CI, 90.06–99.0; 102/106) and a specificity of 98.1% (95% CI, 93.3–99.8) in comparison with microscopy. Meanwhile, sensitivity decreased slightly to 95.4% (95% CI, 88.4–98.0) with somewhat improved specificity when real-time PCR was considered as the reference (Table 2, Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of LAMP methods in comparison with microscopy and real-time PCR.

| Reference Method | Method | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Kappa (κ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | Poon et al.’s LAMP | 96.2% (90.6–99.0) | 98.1% (93.3–99.8) | 98.1% (93.2–99.8) | 96.3% (90.7–99.0) | 0.94 |

| New LAMP | 99.1% (94.9–100.0) | 99.0% (94.8–100.0) | 99.1% (94.9–100.0) | 99.0% (94.8–100.0) | 0.98 | |

| Real time PCR | Poon et al.’s LAMP | 95.4% (89.5–98.5) | 99.0% (94.7–100.0) | 99.0% (94.8–100.0) | 95.3% (89.4–98.5) | 0.94 |

| New LAMP | 98.1% (93.5 –99.8) | 100.0% (96.5–100.0) | 100.0% (96.6–100.0) | 98.1% (93.3–99.8) | 0.98 | |

LAMP with newly designed primers was 99.1% (95% CI, 94.9–100) and 98.1% (95 CI%, 93.5–98.8) sensitive compared to microscopy and real-time PCR, respectively, while specificity was 99% (95% CI, 94.8–100) and 100% (95% CI, 96.5–100) for the assessments (Table 3).

Positive predictive values (PPV), negative predictive values (NPV), and the agreement of both LAMP methods in comparison with microscopy and real-time PCR are presented in Table 3.

4. Discussion

The LAMP primer sets assessed in this study were able to detect clinical falciparum malaria with great accuracy in comparison with microscopy and real-time PCR. LAMP with newly designed primers is more sensitive as it can detect a minimum of 5 P. falciparum parasites/μL of human blood. This method has very good concordance with microscopy and real-time PCR (0.94 and 0.98 respectively). A high PPV of the test method indicates its ability to detect actual positive cases. Conversely, a high NPV reveals its accuracy in excluding false-positive cases, which is also reflected in the 100% specificity of the new LAMP method.

LAMP method comprising auto-cycling and strand displacement DNA synthesis has become superior to other nucleic acid amplification techniques due to its simplicity, rapidity, sensitivity, specificity, and cost effectiveness (Abdul-Ghani et al., 2012). This method is very robust, and rare mutations do not affect its efficacy unless they occur in the extreme ends of the primer-binding sites (Notomi et al., 2000).

Poon et al. (2006) described 95% sensitivity and 99% specificity in regard to PCR in their first implementation of LAMP in malaria. The same primer set was replicated in the genus-and species-specific LAMP described by Han et al. (2007), where all of the 12 microscopy and PCR-positive P. falciparum samples were successfully detected by LAMP. Poschl et al. (2010) described 100% sensitivity and specificity of LAMP compared to nested PCR using the same primer set and reaction conditions. Lucchi et al. (2010) have also utilized the same primer set in real-time fluorescence LAMP with portable fluorescence reader, with 98.8% sensitivity and 100% specificity, while Paris et al. (2007) described 73.1% sensitivity compared to microscopy using the same primer set with 100% specificity. In this study, the primer set described by Poon et al. (2006) has failed to detect five real-time PCR-positive samples despite the pre-addition of HNB for easy visual detection, while four of the samples were positive by microscopy also. Three of these four samples had parasitemia of 16 parasites/μL. However, one sample was found positive only when real-time PCR crossed the detection threshold in its last cycle. This study also confirmed that the primer set described by Poon et al. (2006) can detect a minimum of 100 parasites/μL. Thus, it is an inherent limitation of Poon et al.’s (2006) primer set that it would miss those four samples. However, this set also failed to detect one P. falciparum positive sample of 25,000 parasites/μL. Any significant mutation in the extremes of the primer-binding site as discussed earlier might contribute to this phenomenon. On the other hand, the fact that one negative sample was a false-positive for P. falciparum using this primer set may be due to rare cross-reactivity of the primers. Both of these discordant events were not confirmed by sequence analysis in this study. The factors discussed here might also contribute to such variations in outcome of the same primer set in the different studies mentioned above.

The newly designed primer set has overlapping regions with the primer set described by Poon et al. (2006) in the F3 region, shown in gray in Fig. 1. This primer set can efficiently bind with three copies of 18S rRNA genes residual of at least three different chromosomes of the same parasite (NCBI BLAST request ID: DD77A3ZC0R, DD7KBG8J016, DD80J0X6013). Since this primer set can detect 5 parasites/μL, it requires approximately 15 copies of template to obtain significant visible amplification. However, Notomi et al. (2000), in their initial design, mentioned that the LAMP method can conduct visible amplification from six copies of template within 45 min when primer designing and reaction conditions are perfectly optimized. This primer set have failed to detect two of the real-time PCR-positive samples when one of them was microscopically positive with a low parasitemia (16 parasites/μL). These real-time PCR-positive samples had high threshold values and low relative fluorescence unit (RFU). Both the samples also tested negative by the LAMP method of Poon et al. (2006). Despite this minor incongruity in sensitivity, the new primer set was 100% successful in avoiding false-positive diagnosis due to cross-reactivity.

Yamamura et al. (2009) designed another 18S rRNA–based primer set for P. falciparum detection, which can detect 10 copies of plasmid DNA after 80 min of amplification. This method was determined to be 97.8% sensitive and 85.7% specific. However, cross-reactions of the primers with P. vivax and other undefined targets were ignored by melt curve analysis. This method also required sophisticated instruments like Genopattern Analyzer GP1000, which limits its wide application (Yamamura et al., 2009).

Mitochondrial DNA has 20–150 copies in the same parasite. Polley et al. (2010) described another primer set targeting mitochondrial DNA for the detection of P. falciparum malaria. Thus, this set also can detect 5 parasites/μL. This primer set is 93.3% sensitive and 100% specific in identifying P. falciparum cases. Recently, a commercial Pan/Pf LAMP assay was developed and evaluated in two different settings (Hopkins et al., 2013, Polley et al., 2013). Both of these studies reported highly sensitive detection of malaria cases but one study (Hopkins et al., 2013) reported compromised specificity and NPV when implemented in field, which is due to the detection of a high number of false-positive samples. The kit used expensive Calcein or turbidity meter. Calcein fluorescence has some drawbacks also, such as lower detection sensitivity and brightness of the fluorescence (Goto et al., 2009).

Bst DNA polymerase can endure several inhibitors, while PCR is inhibited by minimal concentration of hemoglobin, IgM, and IgG (Abdul-Ghani et al., 2012).

Introducing easier sample preparation rather than Qiagen extraction with this sensitive and specific primer set, and simple and cheap endpoint visual detection, might provide a practical way to develop a LAMP assay for P. falciparum for routine diagnostic purposes. Future studies will validate this method with heat-treated samples or the simple boil and spin extraction for practical use in endemic countries.

In conclusion, the new LAMP method is highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of symptomatic falciparum malaria. This method can be an alternative molecular diagnostic tool to PCR and might become a standard method for wide use. Furthermore, this method has immense potential to become a tangible tool for point-of-care diagnosis of malaria and treatment monitoring in healthcare and epidemiological studies.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research study was funded by icddr,b and its donors, which provided unrestricted support to icddr,b for its operations and research. Current donors providing unrestricted support include: Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Swedish International Development Corporation Agency (Sida), and the Department for International Development, UK (DFID). We gratefully acknowledge these donors for their support and commitment to icddr,b's research efforts.

The authors are grateful to the NMCP for their permission to conduct the study in their facilities. The authors are also indebted to the people of Matiranga who consented to participate in the study and the doctors and staff of Matiranga and Ramu UHC for their extended support. The authors are indebted to Mohammad Sharif Hossain for analyzing the data. The authors also appreciate the contribution of Shariar Mustafa, Mamun Kabir, Milka Patracia Podder, H.M. Al-Amin, Khaja Md. Mohiuddin, and Gulam Musawwir Khan for their valuable contributions to the study.

Contributor Information

Abu Naser Mohon, Email: abu_naser@icddrb.org.

Rubayet Elahi, Email: arelahi@uams.edu.

Wasif A. Khan, Email: wakhan@icddrb.org.

Rashidul Haque, Email: rhaque@icddrb.org.

David J. Sullivan, Jr., Email: dsulliva@jhsph.edu.

Mohammad Shafiul Alam, Email: shafiul@icddrb.org.

References

- Abdul-Ghani R., Al-Mekhlafi A.M., Karanis P. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for malarial parasites of humans: would it come to clinical reality as a point-of-care test? Acta. Trop. 2012;122:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam M.S., Mohon A.N., Mustafa S., Khan W.A., Islam N., Karim M.J., Khanum H., Sullivan D.J., Jr., Haque R. Real-time PCR assay and rapid diagnostic tests for the diagnosis of clinically suspected malaria patients in Bangladesh. Malar. J. 2011;10:175. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J., McCarthy J., Gatton M., Kyle D.E., Belizario V., Luchavez J., Bell D., Cheng Q. Genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 (PfHRP2) and its effect on the performance of PfHRP2-based rapid diagnostic tests. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;192:870–877. doi: 10.1086/432010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso T.C., Ferrari H.F., Bregano L.C., Silva-Frade C., Rosa A.C.G., Andrade A.L. Visual detection of turkey coronavirus RNA in tissues and feces by reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) with hydroxynaphthol blue dye. Mol. Cell. Probes. 2010;24:415–417. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa D., Ho M.F., Bendezu J., Torres K., Chiodini P.L., Barnwell J.W., Incardona S., Perkins M., Bell D., McCarthy J., Cheng Q. A large proportion of P. falciparum isolates in the Amazon region of Peru lack pfhrp2 and pfhrp3: implications for malaria rapid diagnostic tests. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto M., Honda E., Ogura A., Nomoto A., Hanaki K.I. Colorimetric detection of loopmediated isothermal amplification reaction by using hydroxy naphthol blue. Biotechniques. 2009;46:167–172. doi: 10.2144/000113072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grab D.J., Nikolskaia O.V., Inoue N., Thekisoe O.M.M., Morrison L.J., Gibson W., Dumler J.S. Using detergent to enhance detection sensitivity of African trypanosomes in human CSF and blood by loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) PLoS Negl. Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han E.T., Watanabe R., Sattabongkot J., Khuntirat B., Sirichaisinthop J., Iriko H., Jin L., Takeo S., Tsuboi T. Detection of four Plasmodium species by genus-and species-specific loop-mediated isothermal amplification for clinical diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:2521–2528. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02117-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M., Zha L., Fu W., Zou M., Li W., Xu D. A modified visual loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for diagnosis and differentiation of main pathogens from Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. World J. Microb. Biotechnol. 2012;28:523–531. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0843-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins H., Gonzalez I.J., Polley S.D., Angutoko P., Ategeka J., Asiimwe C., Agaba B., Kyabayinze D.J., Sutherland C.J., Perkins M.D., Bell D. Highly sensitive detection of malaria parasitemia in a malaria-endemic setting: performance of a new loop-mediated isothermal amplification kit in a remote clinic in Uganda. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;208:645–652. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchi N.W., Demas A., Narayanan J., Sumari D., Kabanywanyi A., Kachur S.P., Barnwell J.W., Udhayakumar V. Real-time fluorescence loop mediated isothermal amplification for the diagnosis of malaria. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X., Shu Y., Nie K., Qin M., Wang D., Gao R., Wang M., Wen L., Han F., Zhou S. Visual detection of pandemic influenza A H1N1 Virus 2009 by reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification with hydroxynaphthol blue dye. J. Virol. Methods. 2010;167:214–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohon A.N., Elahi R., Podder M.P., Mohiuddin K., Hossain M.S., Khan W.A., Haque R., Alam M.S. Evaluation of the OnSite (Pf/Pan) rapid diagnostic test for diagnosis of clinical malaria. Malar. J. 2012;11:415. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Y., Notomi T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): a rapid, accurate, and cost-effective diagnostic method for infectious diseases. J. Infect. Chemother. 2009;15:62–69. doi: 10.1007/s10156-009-0669-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C.K., Bennett J.W. Rapid diagnosis of malaria. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2009;2009:415953. doi: 10.1155/2009/415953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notomi T., Okayama H., Masubuchi H., Yonekawa T., Watanabe K., Amino N., Hase T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E63. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris D.H., Imwong M., Faiz A.M., Hasan M., Yunus E.B., Silamut K., Lee S.J., Day N.P.J., Dondorp A.M. Loop-mediated isothermal PCR (LAMP) for the diagnosis of falciparum malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007;77:972–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polley S.D., Gonzalez I.J., Mohamed D., Daly R., Bowers K., Watson J., Mewse E., Armstrong M., Gray C., Perkins M.D., Bell D., Kanda H., Tomita N., Kubota Y., Mori Y., Chiodini P.L., Sutherland C.J. Clinical evaluation of a loop-mediated amplification kit for diagnosis of imported malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;208:637–644. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polley S.D., Mori Y., Watson J., Perkins M.D., GonzAlez I.J., Notomi T., Chiodini P.L., Sutherland C.J. Mitochondrial DNA targets increase sensitivity of malaria detection using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J. Clin. Microb. 2010;48:2866–2871. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00355-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon L.L.M., Wong B.W.Y., Ma E.H.T., Chan K.H., Chow L.M.C., Abeyewickreme W., Tangpukdee N., Yuen K.Y., Guan Y., Looareesuwan S. Sensitive and inexpensive molecular test for falciparum malaria: detecting Plasmodium falciparum DNA directly from heat-treated blood by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Clin. Chem. 2006;52:303–306. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.057901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poschl B., Waneesorn J., Thekisoe O., Chutipongvivate S., Karanis P. Comparative diagnosis of malaria infections by microscopy, nested PCR, and LAMP in northern Thailand. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010;83:56–60. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyburn H., Ruanda J., Mwerinde O., Drakeley C. The contribution of microscopy to targeting antimalarial treatment in a low transmission area of Tanzania. Malar. J. 2006;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M.L. Malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:1637–1641. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongsrichanalai C., Barcus M.J., Muth S., Sutamihardja A., Wernsdorfer W.H. A review of malaria diagnostic tools: microscopy and rapid diagnostic test (RDT) Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007;77:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura M., Makimura K., Ota Y. Evaluation of a new rapid molecular diagnostic system for Plasmodium falciparum combined with DNA filter paper, loop-mediated isothermal amplification, and melting curve analysis. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;62:20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]