Abstract

Cell invasion allows cells to migrate across compartment boundaries formed by basement membranes. Aberrant cell invasion is a first step during the formation of metastases by malignant cancer cells. Anchor cell (AC) invasion in C. elegans is an excellent in vivo model to study the regulation of cell invasion during development. Here, we have examined the function of egl-43, the homolog of the human Evi1 proto-oncogene (also called MECOM), in the invading AC. egl-43 plays a dual role in this process, firstly by imposing a G1 cell cycle arrest to prevent AC proliferation, and secondly, by activating pro-invasive gene expression. We have identified the AP-1 transcription factor fos-1 and the Notch homolog lin-12 as critical egl-43 targets. A positive feedback loop between fos-1 and egl-43 induces pro-invasive gene expression in the AC, while repression of lin-12 Notch expression by egl-43 ensures the G1 cell cycle arrest necessary for invasion. Reducing lin-12 levels in egl-43 depleted animals restored the G1 arrest, while hyperactivation of lin-12 signaling in the differentiated AC was sufficient to induce proliferation. Taken together, our data have identified egl-43 Evi1 as an important factor coordinating cell invasion with cell cycle arrest.

Author summary

Cells invasion is a fundamental biological process that allows cells to cross compartment boundaries and migrate to new locations. Aberrant cell invasion is a first step during the formation of metastases by malignant cancer cells. We have investigated how a specialized cell in the Nematode C. elegans, the so-called anchor cell, can invade into the adjacent epithelium during normal development. Our work has identified an oncogenic transcription factor that controls the expression of specific target genes necessary for cell invasion, and at the same time inhibits the proliferation of the invading anchor cell. These findings shed light on the mechanisms, by which cells decide whether to proliferate or invade.

Introduction

Cell invasion, which is initiated by the breaching of basement membranes (BMs), is a regulated physiological process allowing select cells to cross compartment boundaries during normal development. Cell invasion is also the first step that is activated during the formation of metastases by malignant cancer cells [1]. Anchor cell (AC) invasion in C. elegans is a genetically amenable and tractable model that has provided important insights into the molecular pathways regulating cell invasion and uncovered the molecular similarities between tumor cell and developmental cell invasion [2,3].

The AC is specified during the second larval stage (L2) of C. elegans development, when two equivalent precursor cells (Z1.ppp and Z4.aaa) adopt either the AC or the ventral uterine (VU) fate, depending on stochastic differences in LAG-2 Delta/ LIN-12 Notch signaling [4,5]. This initially small difference is amplified by two extra stochastic events, the division order of Z1 and Z4 and the expression onset of hlh-2 in Z1.pp and Z1.aa[6]. The cell that exhibits higher lag-2 expression levels adopts the “default” AC fate and activates LIN-12 Notch signaling in the adjacent cell to induce the VU fate [7]. Unlike the VU cells, which undergo three to four rounds of cell divisions, the AC never divides but remains arrested in G1 phase and adopts an invasive fate. NHR-67, a nuclear receptor of the tailless family, is required to maintain the G1 arrest of the AC by regulating the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) inhibitor CKI-1. In response to the G1 arrest established by NHR-67, the histone deacetylase HDA-1 promotes the invasive AC fate [8]. AC invasion occurs during the third larval stage (L3) of C. elegans development. During this process, the AC is guided ventrally by cues from the adjacent primary vulva precursor cells (VPCs) and the ventral nerve cord. The AC then breaches the two BM layers separating the uterus from the epidermis and establishes direct contact with the invaginating vulva epithelium [9].

Both AC/VU fate specification and AC invasion require the activity of the egl-43 gene, which encodes two isoforms of a Zinc finger transcription factor homologous to the mammalian Evi1 proto-oncogene in the MECOM (Myelodysplastic Syndrome 1(MDS1) and Ecotropic Viral Integration Site 1 (EVI1), MDS1-EVI1) locus [10–12]. Human Evi1 has been implicated in the development of different types of cancer, most notably in the hematopoietic system in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [13,14]. Inhibition of C. elegans egl-43 during the mid-L2 stage leads to the formation of two ACs due to a defect in AC/VU cell specification [10]. However, egl-43 remains expressed in the AC after its specification, where EGL-43 is required together with the AP-1 transcription factor FOS-1 to induce the expression of genes that promote BM breaching (i.e. pro-invasive genes), such as zmp-1, cdh-3 and him-4 [10,11,15].

Despite the importance of egl-43 in regulating pro-invasive gene expression and BM breaching, its exact role during AC invasion remains poorly understood. Here, we report that egl-43 and fos-1 form a positive auto-regulatory feedback-loop. Moreover, egl-43 plays a previously unknown role in establishing the G1 arrest of the AC by repressing Notch-dependent AC proliferation. Thus, egl-43 acts as an important regulator of AC invasion that coordinates the G1 arrest with pro-invasive gene expression.

Results

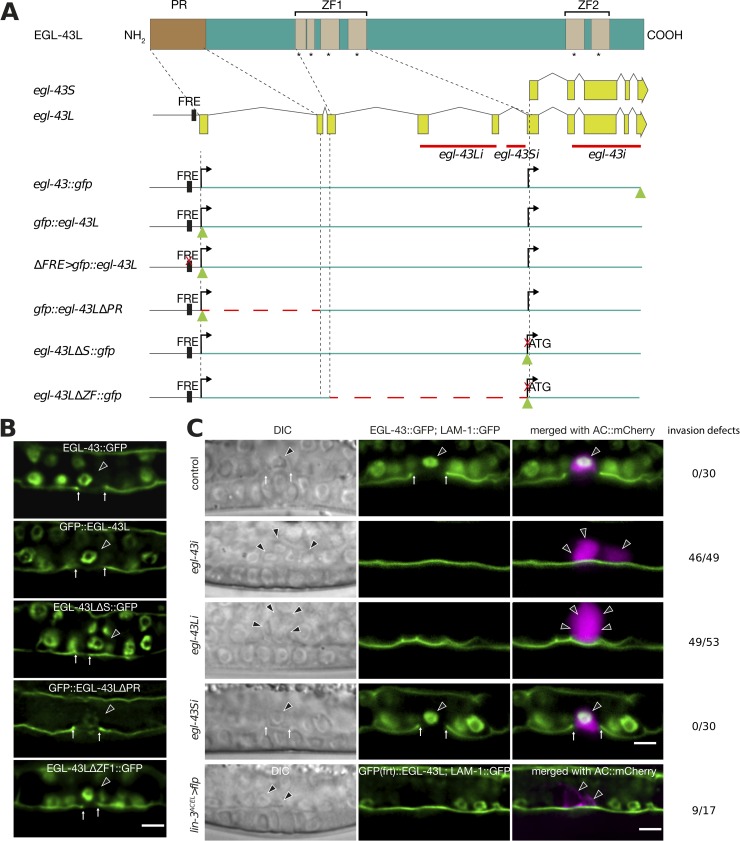

Deletion of the long egl-43L isoform leads to the formation of multiple ACs that fail to invade

In order to study the role of the different egl-43 isoforms during AC invasion, we used CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing [16] to insert gfp tags at the 5’ or 3’ end of the egl-43 locus (Fig 1A). Since the transcriptional start site of the short isoform (egl-43S) is located within the 5th intron of the egl-43L locus, the insertion of the gfp cassette at the 5’ end of the first exon labels exclusively the protein encoded by the long isoform (gfp::egl-43L), whereas the insertion of the gfp tag at the 3’ end of the locus labels both, the short egl-43S and the long egl-43L isoforms (egl-43::gfp, Fig 1A). Furthermore, the gfp cassette inserted at the 5’ end contained two flippase recognition target (FRT) sites in the gfp introns, permitting the tissue-specific inactivation of the egl-43L isoform (S1 Fig). For the expression analysis, we focused on the mid-L3 stage (the Pn.pxx stage, after the VPCs had undergone two rounds of cell divisions), the time when AC invasion normally occurs [9]. Both reporters, gfp::egl-43L and egl-43::gfp, were expressed in the invading AC and in the surrounding ventral and dorsal uterine (VU and DU) cells (Fig 1B, for a quantification of the AC expression levels of the different reporters, see S2 Fig). We found no obvious difference in the expression pattern of the two egl-43 reporters, suggesting that the long egl-43L isoform accounts for most of the expression observed. In order to test if the uterine expression is indeed caused by egl-43L, we designed two RNAi clones, one specifically targeting egl-43L (exons 4 and 5 of egl-43L), and the other targeting the 5’ UTR of egl-43S, which is not included in the egl-43L transcript (Fig 1A). EGL-43::GFP expression was lost upon egl-43L RNAi, yet no difference in expression was observed after egl-43S RNAi (Fig 1C, S2C Fig), supporting the above conclusion that the uterine expression originates predominantly from the long egl-43L isoform.

Fig 1. Loss of egl-43L function leads to the formation of multiple ACs.

(A) Schematic overview of the egl-43 locus and the CRISPR/Cas9 engineered alleles used in this study. Green triangles indicate gfp insertion sites and dashed red line indicate deleted regions. The red crosses indicate the sites of the 11 bp (TTACTCATCTT) deletion in the Fos-Responsive Element (FRE) and of the mutation in the initiation codon of the egl-43S isoform. Solid red lines refer to the regions targeted by RNAi. (B) Expression patterns of the different endogenous egl-43 reporters depicted in (A). The basement membrane (BM) was simultaneously labelled with the LAM-1::GFP marker to score AC invasion. At least 25 animals were examined for each reporter. All animals contained one GFP expressing AC and exhibited BM breaching. A quantification of the AC expression levels is shown in S2 Fig. (C) RNAi of the different egl-43 isoforms and FLP/FRT-mediated excision of egl-43L. Left panels show Nomarski (DIC) images and middle panels the fluorescence signals of endogenous EGL-43::GFP expression in the nuclei and the LAM-1::GFP BM marker. The right panels show the GFP signals merged with the ACs labelled by the lin-3ACEL>mCherry reporter (rows 1–4) and cdh-3>mCherry::PH (row 5) in magenta. The black arrowheads point at the AC nuclei and the white arrows at the locations of the BM breaches. Control refers to animals exposed to the empty RNAi vector. The numbers to the right indicate the penetrance of the invasion defects. A quantification of the AC expression levels is shown in S2C Fig. The scale bars are 5 μm.

As reported previously [11], egl-43L RNAi led to an invasion defect with a penetrance comparable to that of total egl-43 RNAi (92% for egl-43L (n = 53) and 94% for total egl-43 RNAi (n = 49), combined data from two independent RNAi experiments). Consistent with a role of egl-43 during AC/VU specification [10,11], we detected early L3 larvae with two ACs upon egl-43L or total egl-43 RNAi (Fig 1C). However, in 36 out of 49 cases, total egl-43 RNAi led to the formation of more than two ACs, a phenotype that cannot be explained by an AC/VU specification defect (Fig 1C). Similar to the invasion defects, the occurrence of multiple ACs was also caused by selective inhibition of the long egl-43L isoform, with 42 out of 53 worms containing more than 2 ACs (Fig 1C). Moreover, the number of ACs increased progressively with the age of the larvae, indicating an ongoing proliferation of the AC after the L2 stage (Fig 2A and 2B). This pointed to an additional role of egl-43L in preventing the proliferation of the AC after its specification, independently of its function during VU fate specification.

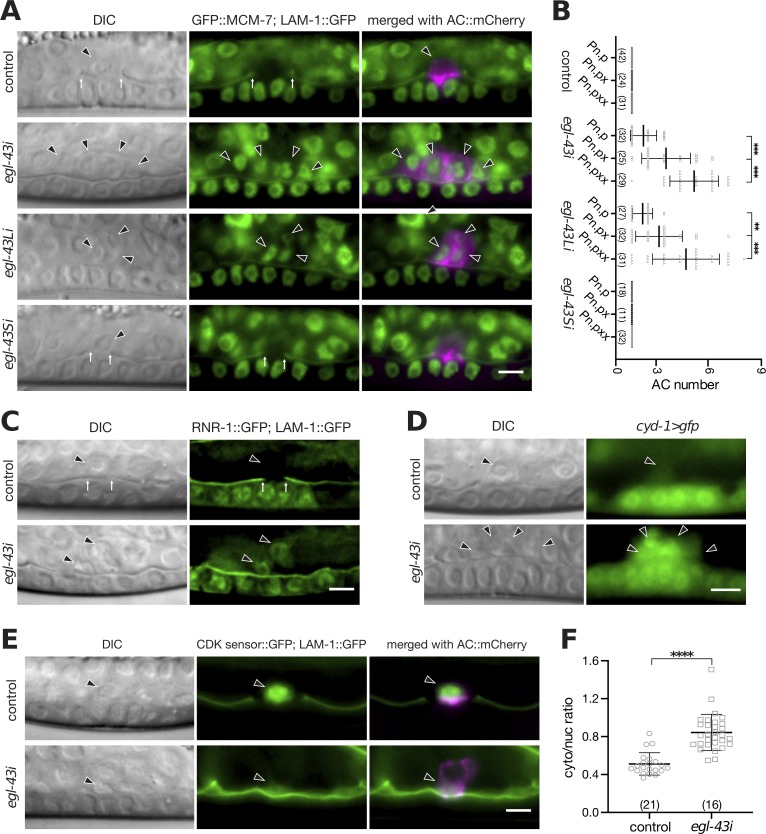

Fig 2. egl-43 is required for the G1 arrest of the AC.

(A) Expression of the endogenous GFP::MCM-7 reporter after RNAi of the different egl-43 isoforms. Elevated AC expression of GFP::MCM-7 was detected after egl-43 RNAi and egl-43L RNAi (29/29 and 28/31 cases, respectively), but not after control or egl-43S RNAi (0/31 and 0/32 cases, respectively). The left panels depict Nomarski (DIC) images and the middle panels nuclear GFP::MCM-7 expression together with the LAM-1::GFP BM marker at the mid-L3 stage. The right panels show the GFP signals merged with the ACs labelled by the cdh-3>mCherry::PH reporter in magenta. (B) Quantification of the number of ACs formed after RNAi of the different egl-43 isoforms from the early L3 (Pn.p) until the mid-L3 (Pn.pxx) stage. The error bars indicate the standard deviation. (C) Expression of the S-phase marker RNR-1::GFP together with LAM-1::GFP in control and egl-43 RNAi-treated mid-L3 larvae. No RNR-1::GFP expression was detected in 48 control RNAi animals, while 30/39 egl-43 RNAi- treated animals expressed the S-phase marker. (D) Elevated expression of the Cyclin D cyd-1>gfp reporter in the multiple ACs of egl-43 RNAi-treated mid-L3 larvae was observed in 52/58 cases, while all 43 control larvae showed faint cyd-1>gfp expression in the single AC. (E) Expression of the CDK activity sensor in the AC of control and egl-43 RNAi-treated mid-L3 larvae together with the LAM-1::GFP BM marker. The right panels show the CDK sensor signal merged with the ACs labelled by the lin-3ACEL>mCherry reporter in magenta. (F) Quantification of CDK sensor activity in the AC. Scatter plots showing the cytoplasmic to nuclear intensity ratio as a measure of CDK activity. The error bars indicate the standard deviation and the vertical bars in (B) and horizontal bars in (F) the mean values. Statistical significance was determined with a Student’s t-test and is indicated with ** for p<0.01, *** for p<0.001, **** for p<0.0001 and n.s for p> 0.05. In each graph, the numbers of animals scored are indicated in brackets. The black arrowheads point at the AC nuclei and the white arrows at the locations of the BM breaches. The scale bars are 5 μm.

In order to specifically examine the role of the egl-43S isoform during AC invasion, we used CRISPR/Cas9 engineering to introduce an ATG→CTG mutation in the predicted egl-43S start codon (egl-43LΔS::gfp, Fig 1A and 1B). The egl-43LΔS::gfp strain was viable and showed a similar expression pattern as the egl-43::gfp and gfp::egl-43L strains (Fig 1B). Moreover, AC invasion occurred normally in all egl-43LΔS::gfp animals examined, and no AC proliferation was observed (n = 35), which confirms the predominant role of egl-43L in regulating AC invasion and proliferation.

Finally, we used the Flp/FRT system to generate an AC-specific knock-out of egl-43L [17]. Since two FRT sites had been inserted in introns of the gfp cassette at the 5’ end of the egl-43L locus, the expression of the FLPase under control of the AC-specific lin-3 enhancer element (lin-3ACEL>flp) [18] specifically inactivated egl-43L in the AC (S1 Fig). Deletion of egl-43L in the AC led to invasion defects (9 out of 17 animals) and the formation of multiple ACs (4 out of 17 cases), similar to the phenotypes caused by egl-43 RNAi (Fig 1C). The relatively low penetrance observed after Flp/FRT-mediated excision compared to RNAi could be due to the perdurance of the EGL-43 protein in the AC, as faint GFP::EGL-43 expression in the AC of mid-L3 larvae could be observed in 2 out of 17 cases.

In summary, the long egl-43L isoform acts cell-autonomously to block AC proliferation and promote invasion.

Neither the N-terminal PR nor the ZF1 domains in EGL-43 are necessary for AC invasion

egl-43L encodes a transcription factor containing an N-terminal PRD1-BF1/RIZ-1 domain (PR) and two separate clusters of Zinc finger domain (ZF1 & ZF2) that could exhibit DNA binding activity [12]. PR domains are structurally similar to the SET (Su(var)3-9, Enhancer of zeste and Trithorax) domains, which contribute to histone lysine methyltransferase activity and have also been reported to mediate protein-protein interactions [19,20]. In order to dissect the requirement of the different EGL-43 domains during AC invasion, we generated in-frame deletions in the egl-43 coding region using the CRISPR/Cas9 system (Fig 1A). In the PR domain deletion allele (gfp::egl-43ΔPR, deleted amino acids 2–62), we detected an approximately 75% decrease in GFP::EGL-43L expression levels in the AC (Fig 1B, S2A Fig). Despite this strong reduction, neither the proliferation nor the invasion of the AC were affected as all 25 animals scored showed normal AC invasion and no proliferation. Thus, the PR domain in EGL-43 is not necessary for AC invasion. Though, the reduced expression levels suggested that the PR domain is either required for egl-43 autoregulation (see below), protein stability, or that there exist additional regulatory elements in the deleted first intron that promote egl-43 expression in the AC (Fig 1A).

Furthermore, no AC invasion defects and no change in expression levels were observed in egl-43ΔZF1::gfp mutants, which carry an in-frame deletion removing amino acids 161–235, which encode the N-terminal Zinc Finger domains (ZF1) (Fig 1B, S2B Fig). Note that this allele also deletes the promoter of the egl-43S isoform. By contrast, the egl-43 null mutant tm1802, which contains a 659 bp deletion removing the C-terminal Zinc Finger domains (ZF2), displays severe developmental defects and early embryonic lethality [11]. Thus, the regulation of AC invasion and proliferation most likely depends on the C-terminal ZF2 domains.

egl-43 is required for the G1 arrest of the AC

Previous studies have shown that the AC must remain arrested in the G1 phase in order to invade [8]. The occurrence of multiple (i.e. more than two) ACs upon inactivation of egl-43L indicated that the AC had bypassed the G1 arrest and begun to proliferate. In order to test this hypothesis, we performed RNAi knock down of the different egl-43 isoforms in a strain carrying an endogenous GFP::MCM-7 reporter. mcm-7 encodes a subunit of the pre-replication complex (pre-RC) that is highly expressed in cycling cells but down-regulated in non-proliferating cells [21,22]. No GFP::MCM-7 expression was detectable in the AC after control or egl-43S RNAi. However, egl-43 and egl-43L RNAi resulted in elevated GFP::MCM-7 levels in the multiple ACs that formed, indicating that these ACs had re-entered the cell cycle (Fig 2A). Consistent with this conclusion, the average number of ACs increased during the development from the Pn.p (late L2/early L3) stage to the Pn.pxx (mid to late L3) stage (Fig 2B).

To further characterize the cell cycle state of the AC, we analyzed RNR-1::GFP expression, which serves as an S-phase marker [23]. While RNR-1::GFP was absent in the AC of control RNAi animals, it was expressed in the multiple ACs formed after egl-43 RNAi (Fig 2C). Moreover, we detected elevated levels of a transcriptional cyd-1>gfp Cyclin D reporter in the multiple ACs produced after egl-43i, while the single AC in control animals showed only faint Cyclin D expression (Fig 2D). Finally, we expressed a CDK biosensor in the AC to directly quantify CDK kinase activity [24,25]. This sensor monitors CDK activity via the phosphorylation-induced nuclear export of a GFP-tagged kinase substrate. Thus, a high cytoplasmic-to-nuclear signal ratio indicates high CDK activity. The multiple ACs formed in egl-43 RNAi-treated animals showed a significantly increased CDK sensor activity compared to the single AC in control RNAi animals (Fig 2E and 2F).

Thus, loss of EGL-43 function increases CDK activity and triggers cell cycle entry of the AC.

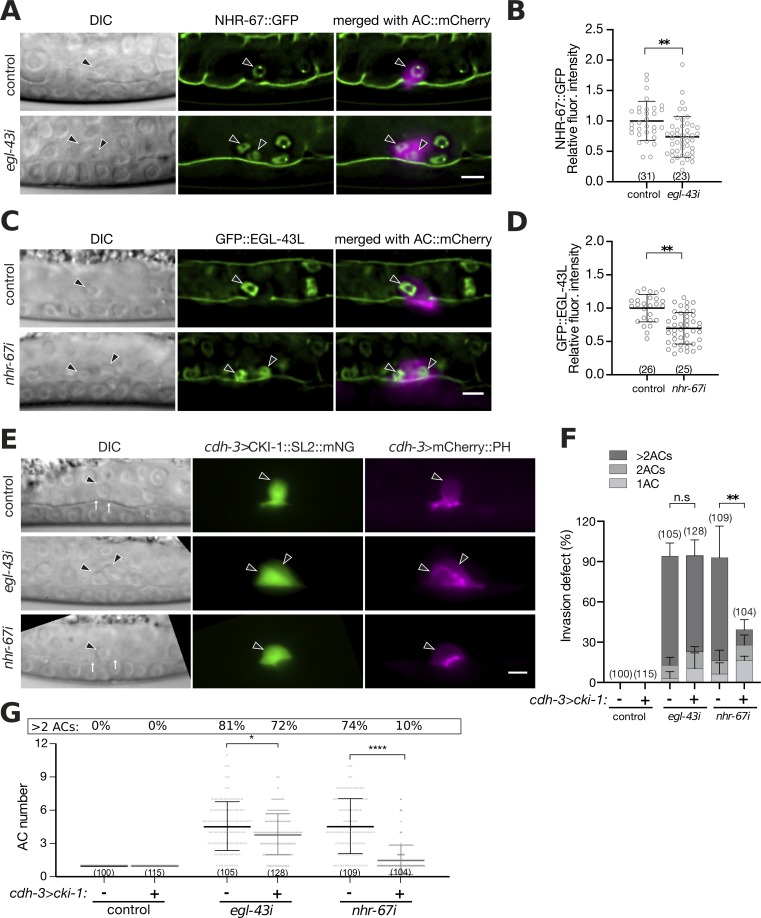

egl-43 and nhr-67 play distinct roles in inducing the G1 arrest of the AC

As reported previously [8], RNAi of nhr-67 led to the appearance of multiple ACs that could not breach the BM (Fig 3A). Since loss of nhr-67 led to a similar phenotype as inhibition of egl-43, we tested whether the expression of nhr-67 depends on egl-43, or vice versa. We first measured egl-43 and nhr-67 GFP reporter expression in early L3 larvae at the Pn.p stage, shortly after AC specification had occurred and the G1 arrest had been established. Quantification of endogenous GFP::EGL-43L reporter levels after nhr-67 RNAi revealed no significant change (S3A and S3B Fig). Also, the expression of an nhr-67::gfp reporter at the early L3 stage was not significantly changed by egl-43 RNAi (Fig 3C and 3D). Moreover, the expression of the histone deacetylase hda-1, which acts downstream of nhr-67 to promote AC invasion [8], was not changed by egl-43 RNAi (S3E and S3F Fig). However, in mid-L3 larvae (Pn.pxx stage), around the time of AC invasion, nhr-67 RNAi caused an approximately 30% reduction in GFP::EGL-43 expression levels, and a similar reduction in NHR-67::GFP expression levels was observed after egl-43 RNAi (Fig 3A–3D). Thus, at later stages egl-43 and nhr-67 may positively regulate each other’s expression.

Fig 3. egl-43 functions in parallel with nhr-67 and cki-1.

(A) Expression of GFP::EGL-43L after control and nhr-67 RNAi. The left panels depict Nomarski (DIC) images and the middle panels GFP::EGL-43L expression together with the LAM-1::GFP BM marker at the mid-L3 (Pn.pxx) stage. The right panels show the GFP signals merged with the ACs labelled by the lin-3ACEL>mCherry reporter in magenta. (B) Quantification of GFP::EGL-43L levels in the AC. (C) Expression of NHR-67::GFP after control and egl-43 RNAi. The left panels depict Nomarski (DIC) images and the middle panels NHR-67::GFP expression together with the LAM-1::GFP BM marker at the mid-L3 (Pn.pxx) stage. The right panels show the GFP signals merged with the ACs labelled by the cdh-3>mCherry::PH reporter in magenta. (D) Quantification of NHR-67::GFP levels in the AC. (E) AC-specific expression of cki-1 from the cdh-3 enhancer/promoter in control, egl-43 and nhr-67 RNAi-treated mid-L3 larvae. The left panels depict Nomarski (DIC) images, the middle panels cdh-3>CKI-1::SL2::mNG expression in green and the right panels the ACs labelled by the cdh-3>mCherry::PH reporter in magenta. Only animals showing mNG expression in the AC were scored. (F) Quantification of the AC invasion and (G) proliferation phenotypes in RNAi-treated animals expressing cdh-3>CKI-1::SL2::mNG (+) compared to their control siblings lacking the cdh-3>cki-1::SL2::mNG transgene (-). The error bars indicate the standard deviation and the horizontal bars the mean values. Statistical significance was determined with a Student’s t-test and is indicated with n.s. for p>0.05, * for p<0.05, ** for p<0.01, and **** for p<0.0001. The black arrowheads point at the AC nuclei. The numbers in brackets in the graphs refer to the numbers of animals analyzed. The scale bars are 5 μm.

Due to the high penetrance of the AC proliferation phenotype caused by single nhr-67 or egl-43 RNAi, we were unable to test if the simultaneous knock-down of both transcription factors had an additive effect. Consistent with a previous report [8], the AC-specific expression of the CDK inhibitor cki-1 together with an mNeonGreen (mNG) marker on a bi-cistronic mRNA under control of a cdh-3 enhancer/promoter fragment (cdh-3>cki-1::SL2::mNG) partially rescued the AC proliferation and invasion defects caused by nhr-67 RNAi (Fig 3E–3G). By contrast, CKI-1 overexpression did not rescue the invasion defects caused by egl-43 RNAi (Fig 3E and 3F), and it only slightly inhibited AC proliferation (Fig 3G). Notably, around 10% of egl-43 RNAi treated and CKI-1 overexpressing animals contained one AC, yet their BMs were not breached (Fig 3F).

These data suggested that that egl-43 acts in parallel with nhr-67 and hda-1 to maintain the G1 arrest and promote invasion of the AC.

egl-43 inhibits AC proliferation by repressing lin-12 Notch expression

LIN-12 Notch signaling is not only critical during the AC/VU decision, but it also links differentiation to cell cycle progression in different tissues [4,26,27]. We therefore tested whether egl-43 regulates lin-12 Notch expression in the AC by examining a translational LIN-12::GFP reporter [28]. In control animals at the mid-L3 stage, LIN-12::GFP expression had disappeared in the AC, while expression persisted in the adjacent VU cells (Fig 4A). By contrast, the multiple ACs that formed after egl-43 RNAi continued to express LIN-12::GFP (Fig 4A). The ACs in egl-43 RNAi-treated larvae still expressed a lin-3::mNG reporter, which serves as a marker to distinguish the AC from the VU fate [29], as well as a reporter for the LIN-12 ligand LAG-2 (S4A and S4B Fig) [30]. Thus, the inhibition of egl-43 did not cause a transformation of the AC into a VU fate, but rather resulted in the ectopic expression of LIN-12 in the proliferating ACs.

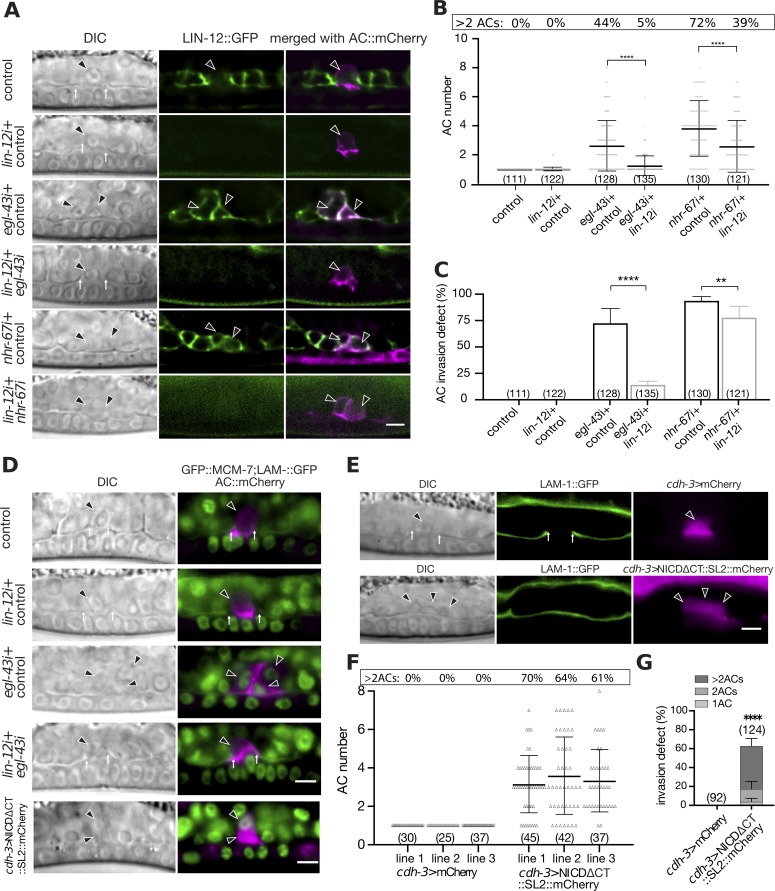

Fig 4. egl-43 and nhr-67 repress lin-12 Notch expression to prevent AC proliferation.

(A) Expression of LIN-12::GFP after control, lin-12, egl-43 or nhr-67 single and egl-43; lin-12 or nhr-67; lin-12 double RNAi. The left panels shows Nomarski (DIC) images, middle panels LIN-12::GFP expression in green and the right panels the GFP signal merged with the AC labelled by the cdh-3>mCherry::PH reporter in magenta. Elevated LIN-12::GFP expression was observed in the ACs of 93/128 egl-43 and 119/130 nhr-67 RNAi treated animals, while none of 111 control RNAi animals showed LIN-12::GFP expression in the AC. (B) Quantification of the AC numbers in mid-L3 larvae treated with the different RNAi combinations shown in (A). (C) Quantification of the AC invasion defects caused by the different RNAi treatments shown in (A). (D) GFP::MCM-7 expression together with LAM-1::GFP after control, egl-43 or lin-12 single and egl-43; lin-12 double RNAi, and in larvae expressing NICDΔCT::mCherry. The left panels show Nomarski (DIC) images and the right panels the GFP::MCM-7 signal in green merged with the AC labelled by the cdh-3>mCherry::PH reporter in magenta. 32/35 egl-43 single RNAi and 13/40 egl-43; lin-12 double RNAi treated animals showed GFP::MCM-7 expression in the AC. None of the 32 control and of the 40 lin-12 single RNAi treated animals exhibited GFP::MCM-7 expression in the AC. Expression of NICDΔCT::mCherry induced GFP::MCM-7 expression in 32/33 cases. (E) AC-specific expression of nicdΔct from the cdh-3 enhancer/promoter leads to the formation of multiple ACs. Left panels shows Nomarski (DIC) images and middle panels the BM marker LAM-1::GFP. The right panels show the mCherry expression from the cdh-3 promoter as a control (row 1) or co-expressed with nicdΔct from a bi-cistronic transcript (row 2). (F) Quantification of the AC numbers in three independent control lines expressing mCherry alone and in three lines expressing NICDΔCT together with mCherry in the AC. (G) Quantification of the AC invasion defects in control lines and in lines expressing NICDΔCT together with mCherry in the AC. The pooled results of the three indepdnet lines are shown. The error bars indicate the standard deviation and the horizontal bars in (B) and (F) the mean values. Statistical significance was determined with a Student’s t-test and is indicated with ** for p<0.01 and **** for p<0.0001. The black arrowheads point at the AC nuclei. The numbers in brackets in the graphs refer to the numbers of animals analyzed. The scale bars are 5 μm.

To test whether an over-activation of lin-12 Notch signaling in the AC is responsible for the AC proliferation phenotype, we performed double RNAi of egl-43 and lin-12 and scored the number of ACs, as well as their ability to invade. While 63% of egl-43 single RNAi-treated animals formed multiple (i.e. more than one) ACs, only 16% of egl-43; lin-12 double RNAi-treated animals contained multiple ACs. The average number of ACs per animals decreased from 2.6 in egl-43 single to 1.2 in egl-43; lin-12 double RNAi-treated animals (Fig 4B), and the penetrance of the AC invasion defect decreased from 72% to 14% (Fig 4C). Eight out of the 19 animals that had been treated with egl-43; lin-12 double RNAi and exhibited an invasion defect contained a single AC. This suggested that the egl-43 invasion phenotype is not exclusively caused by the over-proliferation of the AC.

To test if reducing lin-12 activity restored the cell cycle arrest of the AC, we examined the GFP::MCM-7 reporter, which is expressed exclusively in proliferating cells. Control or single lin-12 RNAi did not induce GFP::MCM-7 expression in the AC of mid-L3 larvae, while egl-43 RNAi resulted in the formation of multiple GFP::MCM-7 positive ACs in 91% of the cases (Figs 2A & 4D). By contrast, the single ACs formed in egl-43; lin-12 double RNAi-treated animals did not express GFP::MCM-7 in 68% of the cases (Fig 4D).

LIN-12::GFP expression was also up-regulated in the AC of nhr-67 RNAi treated animals (Fig 4A). However, inhibition of lin-12 only partially suppressed the AC over-proliferation caused by nhr-67 RNAi from 3.8 to 2.6 ACs per animal (Fig 4B) and only slightly reduced the nhr-67 invasion defects from 94% to 81% (Fig 4C).

Thus, reducing lin-12 activity suppressed the AC proliferation and invasion defects caused by egl-43 RNAi. By contrast, the nhr-67 phenotype was less sensitive to a reduction in lin-12 levels, suggesting that NHR-67 inhibits AC proliferation predominantly through another pathway.

Activation of LIN-12 Notch signaling in the differentiated AC triggers proliferation

These results led to the hypothesis that the ectopic activation of LIN-12 Notch signaling caused by loss of egl-43 function may trigger the re-entry of the AC into the cell cycle. In order to test if LIN-12 signaling is sufficient to induce AC proliferation, we expressed a fragment of the intracellular LIN-12 Notch domain, in which the C-terminal PEST degradation motif had been deleted (NICDΔCT) [26], under the control of the AC-specific cdh-3 enhancer/promoter fragment. Expression of NICDΔCT in the VPCs was shown to hyper-activate the Notch signaling pathway [26], and cdh-3-driven expression occurs only after the AC fate has been specified [31]. Three independent transgenic lines carrying the cdh-3>nicdΔct::SL2::mCherry transgene (co-expressing an mCherry marker on a bi-cistronic mRNA) exhibited an AC proliferation phenotype with an average of 3.4 ACs per animal, which is comparable to the phenotype observed after egl-43 RNAi (Fig 4E and 4F). In addition, the GFP::MCM-7 reporter was up-regulated (Fig 4D), even though GFP::EGL-43L continued to be expressed in the multiple ACs of cdh-3>nicdΔct::SL2::mCherry animals (S4C Fig). In addition, NICDΔCT expression caused a penetrant AC invasion defect (Fig 4G).

Thus, the ectopic activation of the LIN-12 Notch pathway in the differentiated AC was sufficient to trigger cell cycle entry. Taken together, we propose that EGL-43 inhibits LIN-12 Notch expression to maintain the G1 arrest of the invading AC.

A positive regulatory feedback loop between egl-43 and fos-1 activates pro-invasive gene expression

It has previously been reported that fos-1 positively regulates egl-43 expression in the AC and that egl-43 is required for the expression of zmp-1, cdh-3 and him-4 [10,11]. To further characterize the role of egl-43 in regulating pro-invasive gene expression, we investigated a possible mutual regulation of fos-1 and egl-43. The expression of the endogenous GFP::EGL-43L reporter in the AC was reduced approximately two-fold in homozygous fos-1(ar105) mutants compared to heterozygous fos-1(ar105)/+ control siblings at the mid-L3 stage (Fig 5A and 5B). Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, we deleted the 11 bp (TTACTCATCTT) FOS-Responsive Element (FRE) [11] in the promoter region of the endogenous gfp::egl-43L reporter strain (ΔFRE>gfp::egl-43L, Fig 1A). In a heterozygous fos-1(ar105)/+ background, the expression of the mutant ΔFRE>gfp::egl-43L reporter was reduced to a similar extent as the wild-type gfp::egl-43L reporter was reduced in a homozygous fos-1(ar105) background. Since the levels of the FRE mutant reporter did not further decrease in homozygous fos-1(ar105) larvae, FOS-1 appears to control egl-43 expression mainly through this FRE (Fig 5A and 5B). While this experiment confirmed that FOS-1 up-regulates endogenous egl-43 expression, it also pointed at the existence of additional factors that activate egl-43 expression in the AC. In particular, the deletion of the FRE in egl-43 did not cause an obvious defect in AC invasion (all 23 animals scored showed normal AC invasion), suggesting that the reduction in egl-43 expression after the deletion of the FRE can be compensated by the AC.

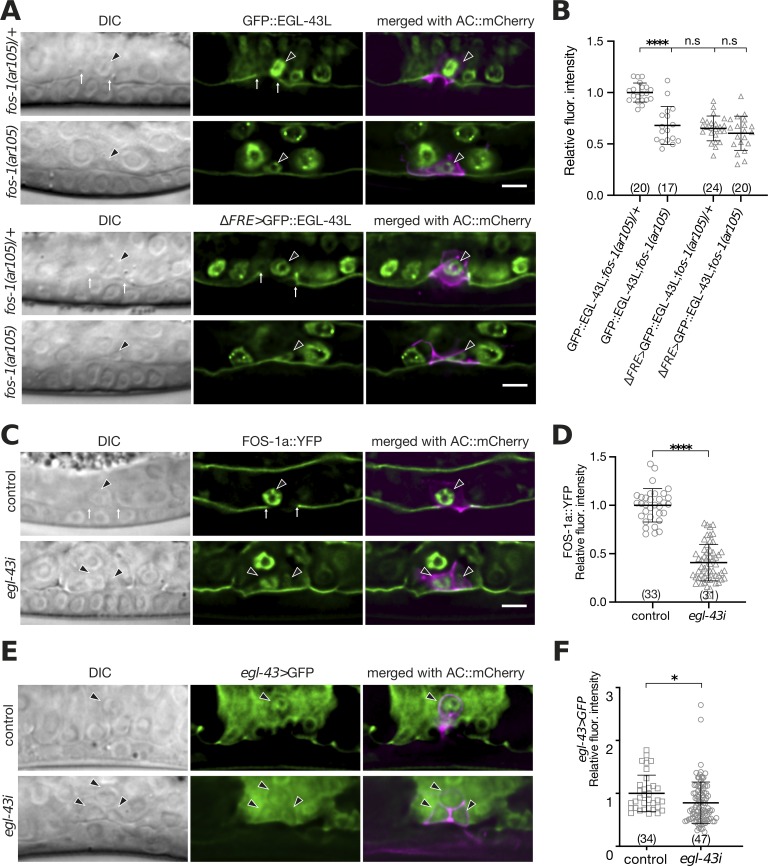

Fig 5. egl-43 and fos-1 regulate each other’s expression.

(A) Expression of endogenous GFP::EGL-43L and of the mutant ΔFRE>GFP::EGL-43L reporter carrying a deletion of the Fos-responsive element TTACTCATCTT (ΔFRE), each in a fos-1(ar105)/+ heterozygous and fos-1(ar105) homozygous background at the mid-L3 stage. (B) Quantification of GFP::EGL-43L expression levels in the ACs of the indicated mutant backgrounds. (C) Expression of a FOS-1a::YFP reporter after control and egl-43 RNAi. (D) Quantification of FOS-1a::YFP levels in the ACs after control RNAi. (E) Expression of a transcriptional egl-43>gfp reporter in the ACs after control and egl-43 RNAi. (F) Quantification of the transcriptional egl-43>gfp reporter expression shown in (E). For each reporter, the left panels show Nomarski (DIC) images, the middle panels the GFP signals of the indicated reporters in green (in (A) and (C) together with the LAM-1::GFP BM marker) and the right panels the GFP reporter signals merged with the ACs labelled with the cdh-3>mCherry::PH reporter in magenta. The black arrowheads point at the AC nuclei and the white arrows at the locations of the BM breaches. The error bars indicate the standard deviation and the horizontal bars the mean values. Statistical significance was determined with a Student’s t-test and is indicated with n.s. for p>0.05, * for p<0.05 and **** for p<0.0001. The numbers in brackets refer to the numbers of animals analyzed. The scale bars are 5 μm.

Since egl-43 and fos-1 regulate some of the same target genes [11,15], we tested if egl-43 regulates fos-1a expression. The expression of a fos-1a::yfp reporter in the AC was reduced approximately three-fold by egl-43 RNAi (Fig 5C and 5D), indicating that egl-43 and fos-1 positively regulate each other’s expression. Moreover, the expression of a transcriptional egl-43L reporter (egl-43L>gfp is a strain containing an insertion of the self-excising cassette [16] after the gfp coding sequences to terminate transcription 5’ of the egl-43 coding sequences) was reduced by egl-43 RNAi (Fig 5E and 5F). Thus, egl-43 positively regulates its own expression in the AC.

Unlike nhr-67 or egl-43, fos-1 was not required to maintain the G1 arrest of the AC, as neither the S-phase maker RNR-1::GFP nor the proliferation marker GFP::MCM-7 were up-regulated after fos-1 RNAi (S5A and S5B Fig). We thus speculated that the regulation of fos-1 by EGL-43 and the cell cycle inhibition via lin-12 repression represent two independent functions of EGL-43. Supporting this hypothesis, LIN-12::GFP expression was not up-regulated by fos-1 RNAi, while expression of NICDΔCT did not affect fos-1 expression levels in the AC (S5C–S5E Fig).

Taken together, the expression analysis indicated that egl-43 and fos-1 form a positive feedback loop that maintains high expression of both transcription factors in the AC to induce the expression of target genes required for invasion. The auto-regulation of egl-43 likely adds further robustness to this network.

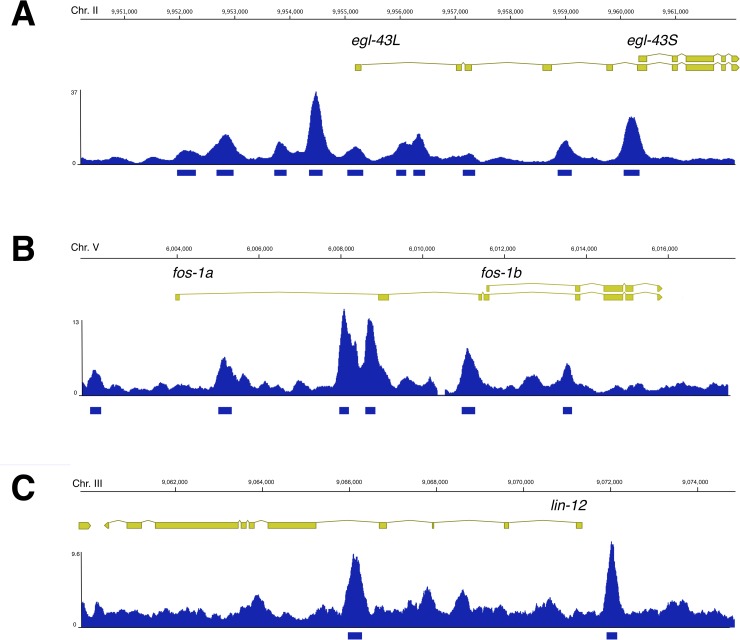

EGL-43 binding is enriched at the fos-1, egl-43 and lin-12 loci

To test if the changes in fos-1, lin-12 and egl-43 reporter expression caused by egl-43 RNAi could be due to a direct regulation by EGL-43, we performed chromatin immuno-precipitation and sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis of the endogenous EGL-43::GFP reporter at the L3 stage using anti-GFP antibodies, in two biological replicates (see extended methods). At this stage, most of the EGL-43::GFP expression was confined to cells in the somatic gonad and to approximately 30 head and 6 tail neurons [11] (and this study). The ChIP-seq analysis identified 6276 peaks of significant enrichment, 5257 of which we could associate with 3977 genes (S5 Table).

EGL-43 binding was found at the egl-43, fos-1 and lin-12 loci (Fig 6). Notably, EGL-43 was also enriched at the jun-1 locus, which encodes the homolog of the human c-JUN proto-oncogene that forms together with c-FOS the AP-1 transcription factor (S5 Table). Even though no function of JUN-1 in AC invasion has been reported, this observation might indicate that EGL-43 regulates AP-1 activity in other processes, such as ovulation or lifespan [32]. Moreover, EGL-43::GFP was enriched at other previously reported targets, including mig-10 [33], hlh-2 [34] and zmp-1 [11] (S5 Table). On the other hand, no specific binding to the nhr-67 [34] or cdh-3 [11] genes was observed, suggesting that these two genes may be indirectly regulated by EGL-43.

Fig 6. EGL-43 binding is enriched at the egl-43, fos-1 and lin-12 loci.

(A) Enrichment of EGL-43 binding at the egl-43, (B) fos-1 and (C) lin-12 loci. The exon-intron structure indicated by the yellow boxes and the genomic locations in base pairs of the three analyzed genes are shown on top. The blue bar graphs show the combined data of two independent ChIP-seq experiments. The numbers on the left vertical axis of each graph indicate the maximal read coverage in the intervals shown. The blue shaded boxes underneath the graphs show the identified peaks. S5 Table contains a list of all identified EGL-43 binding sites.

Taken together, the ChIP-seq analysis suggested that fos-1, lin-12 and egl-43 are direct EGL-43 targets.

Discussion

An uncontrolled activation of cell invasion is one of the hallmarks of malignant cancer cells that form metastases [1]. Genetic studies in model organisms have indicated that invasive tumor cells re-activate the same molecular pathways that control cell invasion during normal animal development. AC invasion in C. elegans has served as an excellent model to dissect the genetic pathways regulating the invasive phenotype of a single cell [3].

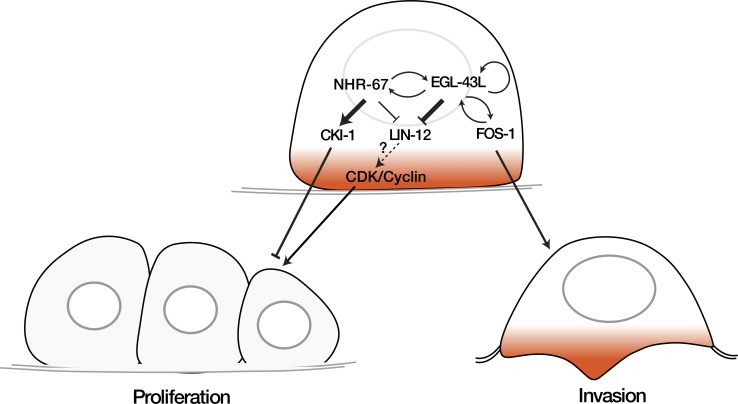

Here, we report that the egl-43 gene, the C. elegans ortholog of the human Evi1 proto-oncogene, functions in a regulatory network together with the transcription factors NHR-67 and FOS-1 to control AC invasion (Fig 7). Our results are consistent with a recent report by Medwig-Kinney et al. [34] demonstrating similar interactions between egl-43, nhr-67 and fos-1 during AC invasion. The inclusion of the LIN-12 NOTCH pathway in our model further expands the network and differentiates between the functions of EGL-43 and the nuclear receptor NHR-67. Even though egl-43 and nhr-67 positively regulate each other’s expression at a later stage, our data indicate that EGL-43 and NHR-67 inhibit AC proliferation through distinct mechanisms.

Fig 7. EGL-43L is part of a regulatory network controlling AC invasion.

EGL-43L plays two distinct functions during AC invasion. Left side: EGL-43L represses LIN-12 Notch expression in the differentiated AC to prevent proliferation. In addition, EGL-43 and NHR-67 positively regulate each other, and NHR-67 controls CKI-1 expression to maintain the G1 arrest of the AC. Right side: EGL-43L activates in a positive feedback loop together with FOS-1 the expression of pro-invasive genes in the AC.

Firstly, EGL-43 maintains the AC arrested in the G1 phase of the cell cycle by repressing the expression of the LIN-12 Notch receptor. The ectopic activation of Notch signaling in the differentiated AC was sufficient to induce proliferation in the presence of EGL-43, while reducing lin-12 expression efficiently suppressed the AC proliferation and invasion defects caused by inhibition of egl-43. Thus, LIN-12 is an essential downstream target of EGL-43 that can reactivate the cell cycle in the AC. A recent study in C. elegans has highlighted the importance of the LIN-12 Notch pathway in keeping an equilibrium between the proliferation and differentiation of somatic cells [27]. Furthermore, the regulation of different cell cycle genes by the Notch pathway has been reported in several cases. For example, Notch signaling induces cyclin D1 expression in mammalian kidney and breast epithelial cells [35,36] and activates dE2F1 and cyclin A expression in the photoreceptor precursors of the Drosophila eye to promote S-phase entry [37].

It was previously shown that NHR-67 maintains the G1 arrest of the AC by inducing the expression of the CDK inhibitor CKI-1 [8]. While overexpression of CKI-1 efficiently rescued the AC proliferation and invasion phenotype caused by nhr-67 RNAi, CKI-1 only slightly suppressed the AC proliferation phenotype and had no effect on the invasion defects caused by egl-43 RNAi. However, it should be noted that the transgene we used to overexpress CKI-1 did not fully suppress the nhr-67 AC proliferation and invasion phenotypes, while a different cki-1 overexpression transgene used by Medwig-Kinney et al. [34] caused a complete rescue of nhr-67 RNAi, probably due to higher levels of CKI-1 expression. It is therefore possible that a further increase in CKI-1 levels beyond the concentration we reached may also suppress the egl-43 phenotype. Taken together, we suggest that the AC proliferation phenotype caused by inhibition of egl-43 is less sensitive to an increase in the CKI-1 dosage than the nhr-67 phenotype.

On the other hand, the nhr-67 AC proliferation and invasion phenotypes were less sensitive to lin-12 inhibition when compared to the egl-43 phenotype, even though NHR-67 RNAi also increased lin-12 expression in the AC. We thus propose that EGL-43 inhibits AC proliferation predominately by repressing LIN-12 NOTCH signaling, while NHR-67 acts primarily by enhancing CKI-1 expression (Fig 7). One possible explanation for the different sensitivities could be that the hyper-activation of LIN-12 signaling caused by loss of egl-43 results in elevated CDK/Cyclin activity, which overcomes a threshold set by CKI-1-mediated cell cycle inhibition. The inhibition of nhr-67, on the other hand, may reduce the threshold by decreasing CKI-1 expression. Since nhr-67 and egl-43 positively regulate each other’s expression in the proliferating ACs, EGL-43 may promote cki-1 expression indirectly via nhr-67.

The egl-43 AC invasion and proliferation phenotypes did not completely correlate, as a fraction of egl-43 depleted animals -especially in combination with lin-12 RNAi- contained a single AC that failed to invade. Hence, EGL-43 appears to have an additional function besides merely preventing AC proliferation. EGL-43 likely exerts the proliferation-independent function through its interaction with fos-1, which is not required for the G1 arrest of the AC but necessary to induce the expression of pro-invasive genes. Deleting the FOS-1 responsive element (FRE) in the endogenous egl-43 locus confirmed our earlier findings based on transgenic reporter analysis that egl-43L expression is positively regulated by FOS-1 [11]. FOS-1 is not absolutely required for the expression of EGL-43, because additional factors such as HLH-2 activate egl-43 expression in the AC [10]. Moreover, EGL-43 positively regulates fos-1 as well as its own expression in the AC. Thanks to the positive feedback loop between egl-43 and fos-1, low levels of either of the two transcription factors may be sufficient to induce a stable expression of both transcription factors and thereby irreversibly determine the invasive fate of the AC. Interestingly, a similar self-activating function has been described for mammalian Evi1 in hematopoietic stem cells [12].

In summary, EGL-43 coordinates the expression of pro-invasive genes with the cell cycle arrest of the AC by inducing fos-1 and inhibiting lin-12 Notch expression. Thus, EGL-43 is a central component in a regulatory network, which decides whether to divide or invade.

Material and methods

C. elegans culture and maintenance

C. elegans strains were maintained at 20°C on standard nematode growth plates as described [38]. The wild-type strain was C. elegans Bristol, variety N2. We refer to translational protein fusions with a :: symbol between the gene name and the tag, while transcriptional fusions are indicated with a > symbol between the promoter/enhancer and the tag. The genotypes of the strains used in this study are listed in S1 Table. The construction of the plasmids, oligonucleotides and sgRNAs used to generate the different reporters are described in the Extended Methods in S1 Text and in S2–S4 Tables.

Scoring the AC invasion phenotype

AC invasion was scored in mid-L3 larvae after the VPC had divided twice (Pn.pxx stage) as described [11]. We monitored the continuity of the BM by DIC or fluorescence microscopy using the qyIs10[lam-1>lam-1::gfp] transgene as a marker.

RNA interference

RNAi interference was done by feeding dsRNA-producing E. coli [39]. Larvae were synchronized at the L1 stage by hypochlorite treatment of gravid adults and plated on NGM plates containing 3mM IPTG. P0 animals were analyzed after 30–36 hours of treatment. For double RNAi experiments, bacteria of the indicated clones were mixed at a 1:1 ration. RNAi clones targeting genes of interest were obtained from the C. elegans genome-wide RNAi library or the C. elegans open reading frame (ORFeome) RNAi library (both from Source BioScience). RNAi vectors targeting egl-43L and egl-43S were subcloned into the L4440 vector by Gibson assembly (S3 Table). The empty L4440 vector (labelled “control” in the figures) was used as negative control in all experiments.

Microscopy and image analysis

Fluorescent and Nomarski images were acquired with a LEICA DM6000B microscope equipped with a Leica DFC360 FX camera and a 63x (N.A. 1.32) oil-immersion lens, or with an Olympus BX61 wide-field microscope equipped with a X-light spinning disc confocal system, a 100x Plan Apo (N.A. 1.4) lens, a lumencor light engine as light source and an iXon ultra888 EMCCD camera. Worms were imaged with 100 x magnification and z-stacks with a spacing of 0.1 to 0.8 μm were recorded. The Fiji software [40] was used for image analysis and fluorescent intensity quantifications using the built-in measurement tools as follows. To quantify expression of the different reporters, deconvolved optical z-sections across the AC were used to generate summed z- projections. The region of the AC nucleus was manually selected, and the integrated signal intensity was measured in the AC nucleus, from which a background value measured in an identically sized region outside of the animal was subtracted. To quantify the CDK sensor activity, images were processed with a Gaussian blur filter (sigma = 50), and a single mid-sagittal z-slice through the AC nucleus was selected for the measurements. The average of the integrated intensities in three equally sized and randomly selected areas, each in the cytoplasm (Ic) and the nucleus (In) of the AC were measured to calculate the cytoplasmic to nuclear (Ic/In) intensity ratios, which are plotted in Fig 2F.

Supporting information

(TIF)

(A) Quantification of GFP::EGL-43L and GFP::EGL-43LΔPR and (B) EGL-43LΔS::GFP and EGL-43LΔZF1::GFP expression levels in the AC of mid-L3 larvae. N- and C-terminal GFP fusions were quantified separately because the site of insertion potentially affects GFP signal intensity. (C) Quantification of the AC expression levels of EGL-43::GFP, a reporter for both the EGL-43L and EGL-43S isoforms, upon control, egl-43, egl-43L, and egl-43S RNAi. The numbers of animals analyzed for each condition are shown in bracket. The error bars indicate standard deviations and the horizontal bars the mean values. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-tests and is indicated with n.s. for p>0.05 and **** for p<0.0001.

(TIF)

(A) NHR-67::GFP expression in the ACs of early-L3 larvae (Pn.p stage) after egl-43 RNAi. (B) Quantification of NHR-67::GFP expression levels after egl-43 RNAi. (C) GFP::EGL-43L expression in the ACs of early-L3 larvae after nhr-67 RNAi. (D) Quantification of GFP::EGL-43 expression levels after nhr-67 RNAi. (E) HDA-1::RFP expression in mid-L3 larvae after egl-43 RNAi. (F) Quantification of the HDA-1::RFP expression shown in (E). For all reporters, left panels show Nomarski (DIC) images, middle panels the respective reporter together with the LAM-1::GFP BM marker, and right panels merged images with the ACs labelled by cdh-3>mCherry::PH (A), cdh-3>mCherry::moeABD (C) or cdh-3>gfp (E). The error bars indicate standard deviations and the horizontal bars the mean values. Statistical significance was determined with a Student’s t-test and is indicated with ** for p<0.01 and n.s. for p>0.05. The numbers in brackets refer to the numbers of animals analyzed. The scale bars are 5 μm.

(TIF)

(A) lin-3 reporter expression in the control and egl-43 RNAi ACs. Left panels show Nomarski (DIC) images and right panels the fluorescence image with LIN-3::mNG. (B) lag-2 expression in the ACs of control and egl-43 RNAi. Left panels shows Nomarski (DIC) images, middle panel the fluorescence image with lag-2>GFP reporter, and right panels the reporter merged with AC marker cdh-3>mCherry::PH. (C) GFP::EGL-43L expression in the ACs of control and NICDΔCT expressing ACs. Left panels show Nomarski (DIC) images, middle panels the GFP::EGL-43 signal with the LAM-1::GFP BM marker, and right panels merged with the ACs labelled with cdh-3>PH::mCherry (control, row 1) and cdh-3>NICDΔCT::SL2::mCherry (row 2) respectively. (D) Quantification of the GFP::EGL-43L expression shown in (C). The error bars indicate standard deviations and the horizontal bars the mean values. Statistical significance was determined with a Student’s t-test and is indicated with n.s. for p>0.05. The numbers in brackets refer to the numbers of animals analyzed. The scale bars are 5 μm.

(TIF)

(A) Expression of the S-phase marker RNR-1::GFP after control and fos-1 RNAi. None of 19 control or 23 fos-1i animals showed RNR-1::GFP expression in the AC. (B) Expression of GFP::MCM-7 after control and fos-RNAi. None of 25 control or 25 fos-1i animals showed GFP::MCM-7 expression. (C) LIN-12::GFP expression is not up-regulated after control (0/20) or fos-1 (0/24) RNAi treatment. (D) Expression of FOS-1a::YFP in control and NICDΔCT-expressing ACs of mid-L3 larvae. (E) Quantification of the FOS-1a::YFP expression shown in (D). For each reporter, the left panels show Nomarski (DIC) images, the middle panels the GFP or YFP signals of the indicated reporters in green (in (B) and (D) together with the LAM-1::GFP BM marker) and the right panels the GFP reporter signals merged with the ACs labelled with the cdh-3>mCherry::moeABD (A, C), lin-3ACEL>mCherry (B) or cdh-3>nicdΔct::sl2::mCherry (D) reporters in magenta. The black arrowheads point at the AC nuclei and the white arrows at the locations of the BM breaches. The error bars indicate standard deviations and the horizontal bars the mean values. Statistical significance was determined with a Student’s t-test and is indicated with n.s for p>0.05. The numbers in brackets refer to the numbers of animals analyzed. The scale bars are 5 μm.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank members of the Hajnal laboratory for numerous discussions, the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440), and the van der Heuvel laboratory for providing strains. We are also grateful to Andrew Fire for making gfp vectors available.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files. The ChIP-seq data generated in this study are available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE144292.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant no. 31003A-166580 and by the Kanton of Zürich. Julie Ahringer's laboratory was supported by Wellcome grant 101863 and by core funding from the Wellcome Trust (092096) and Cancer Research UK (C6946/A14492). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144: 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagedorn EJ, Sherwood DR. Cell invasion through basement membrane: the anchor cell breaches the barrier. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23: 589–596. 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherwood DR, Plastino J. Invading, Leading and Navigating Cells in Caenorhabditis elegans: Insights into Cell Movement in Vivo. Genetics. Genetics; 2018;208: 53–78. 10.1534/genetics.117.300082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seydoux G, Greenwald I. Cell autonomy of lin-12 function in a cell fate decision in C. elegans. Cell. 1989;57: 1237–1245. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90060-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenwald I, Kovall R. Notch signaling: genetics and structure. WormBook. 2013;: 1–28. 10.1895/wormbook.1.10.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attner MA, Keil W, Benavidez JM, Greenwald I. HLH-2/E2A Expression Links Stochastic and Deterministic Elements of a Cell Fate Decision during C. elegans Gonadogenesis. Curr Biol. 2019;29: 3094–3100.e4. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.07.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson HA, Fitzgerald K, Greenwald I. Reciprocal changes in expression of the receptor lin-12 and its ligand lag-2 prior to commitment in a C. elegans cell fate decision. Cell. 1994;79: 1187–1198. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matus DQ, Lohmer LL, Kelley LC, Schindler AJ, Kohrman AQ, Barkoulas M, et al. Invasive Cell Fate Requires G1 Cell-Cycle Arrest and Histone Deacetylase-Mediated Changes in Gene Expression. Elsevier Inc; 2015;35: 162–174. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anchor Cell Invasion into the Vulval Epithelium in C. elegans. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hwang BJ, Meruelo AD, Sternberg PW. C. elegans EVI1 proto-oncogene, EGL-43, is necessary for Notch-mediated cell fate specification and regulates cell invasion. Development. The Company of Biologists Ltd; 2007;134: 669–679. 10.1242/dev.02769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rimann I, Hajnal A. Regulation of anchor cell invasion and uterine cell fates by the egl-43 Evi-1 proto-oncogene in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 2007;308: 187–195. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maicas M, Vázquez I, Alis R, Marcotegui N, Urquiza L, Cortés-Lavaud X, et al. The MDS and EVI1 complex locus (MECOM) isoforms regulate their own transcription and have different roles in the transformation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2017;1860: 721–729. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Y, Liang Y, Zheng X, Deng X, Huang W, Zhang G. EVI1 promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, cancer stem cell features and chemo-/radioresistance in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. BioMed Central; 2019;38: 82–17. 10.1186/s13046-019-1077-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goyama S, Yamamoto G, Shimabe M, Sato T, Ichikawa M, Ogawa S, et al. Evi-1 is a critical regulator for hematopoietic stem cells and transformed leukemic cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3: 207–220. 10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherwood DR, Butler JA, Kramer JM, Sternberg PW. FOS-1 promotes basement-membrane removal during anchor-cell invasion in C. elegans. Cell. 2005;121: 951–962. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickinson DJ, Pani AM, Heppert JK, Higgins CD, Goldstein B. Streamlined Genome Engineering with a Self-Excising Drug Selection Cassette. Genetics. 2015;200: 1035–1049. 10.1534/genetics.115.178335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis MW, Morton JJ, Carroll D, Jorgensen EM. Gene activation using FLP recombinase in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2008;4: e1000028 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang BJ, Sternberg PW. A cell-specific enhancer that specifies lin-3 expression in the C. elegans anchor cell for vulval development. 2004;131: 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang S, Shao G, Liu L. The PR domain of the Rb-binding zinc finger protein RIZ1 is a protein binding interface and is related to the SET domain functioning in chromatin-mediated gene expression. J Biol Chem. American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; 1998;273: 15933–15939. 10.1074/jbc.273.26.15933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou B, Wang J, Lee SY, Xiong J, Bhanu N, Guo Q, et al. PRDM16 Suppresses MLL1r Leukemia via Intrinsic Histone Methyltransferase Activity. Mol Cell. 2016;62: 222–236. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korzelius J, The I, Ruijtenberg S, Portegijs V, Xu H, Horvitz HR, et al. C. elegans MCM-4 is a general DNA replication and checkpoint component with an epidermis-specific requirement for growth and viability. Dev Biol. 2011;350: 358–369. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Heuvel S. Cell-cycle regulation. WormBook. 2005;: 1–16. 10.1895/wormbook.1.28.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park M, Krause MW. Regulation of postembryonic G(1) cell cycle progression in Caenorhabditis elegans by a cyclin D/CDK-like complex. 1999;126: 4849–4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spencer SL, Cappell SD, Tsai F-C, Overton KW, Wang CL, Meyer T. The proliferation-quiescence decision is controlled by a bifurcation in CDK2 activity at mitotic exit. Cell. 2013;155: 369–383. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Rijnberk LM, van der Horst SEM, van den Heuvel S, Ruijtenberg S. A dual transcriptional reporter and CDK-activity sensor marks cell cycle entry and progression in C. elegans. Prigent C, editor. PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science; 2017;12: e0171600 10.1371/journal.pone.0171600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nusser-Stein S, Beyer A, Rimann I, Adamczyk M, Piterman N, Hajnal A, et al. Cell-cycle regulation of NOTCH signaling during C. elegans vulval development. Mol Syst Biol. 2012;8: 618–614. 10.1038/msb.2012.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coraggio F, Püschel R, Marti A, Meister P. Polycomb and Notch signaling regulate cell proliferation potential during Caenorhabditis elegans life cycle. Life Sci Alliance. Life Science Alliance; 2019;2: e201800170 10.26508/lsa.201800170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarov M, Murray JI, Schanze K, Pozniakovski A, Niu W, Angermann K, et al. A genome-scale resource for in vivo tag-based protein function exploration in C. elegans. Cell. 2012;150: 855–866. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill RJ, Sternberg PW. The gene lin-3 encodes an inductive signal for vulval development in C. elegans. 1992;358: 470–476. 10.1038/358470a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen N, Greenwald I. The lateral signal for LIN-12/Notch in C. elegans vulval development comprises redundant secreted and transmembrane DSL proteins. 2004;6: 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inoue T, Sherwood DR, Aspöck G, Butler JA, Gupta BP, Kirouac M, et al. Gene expression markers for Caenorhabditis elegans vulval cells. Mech Dev. 2002;119 Suppl 1: S203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiatt SM, Duren HM, Shyu YJ, Ellis RE, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans FOS-1 and JUN-1 regulate plc-1 expression in the spermatheca to control ovulation. Tansey WP, editor. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20: 3888–3895. 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L, Shen W, Lei S, Matus D, Sherwood D, Wang Z. MIG-10 (Lamellipodin) stabilizes invading cell adhesion to basement membrane and is a negative transcriptional target of EGL-43 in C. elegans. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2014;452: 328–333. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.08.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medwig-Kinney TN, Smith JJ, Palmisano NJ, Tank S, Zhang W, Matus DQ. A developmental gene regulatory network for C. elegans anchor cell invasion. Development. 2020;147: dev185850 10.1242/dev.185850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronchini C, Capobianco AJ. Induction of cyclin D1 transcription and CDK2 activity by Notch(ic): implication for cell cycle disruption in transformation by Notch(ic). Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21: 5925–5934. 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5925-5934.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen B, Shimizu M, Izrailit J, Ng NFL, Buchman Y, Pan JG, et al. Cyclin D1 is a direct target of JAG1-mediated Notch signaling in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. Springer US; 2010;123: 113–124. 10.1007/s10549-009-0621-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baonza A, Freeman M. Control of cell proliferation in the Drosophila eye by Notch signaling. Dev Cell. 2005;8: 529–539. 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brenner S. The Genetics of CAENORHABDITIS ELEGANS. Genetics. 1974;77: 71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamath RS, Ahringer J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods. 2003;30: 313–321. 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00050-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Meth. Nature Publishing Group; 2012;9: 676–682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]