Abstract

The blood pressure (BP) response to exercise is exaggerated in the type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). An overactive exercise pressor reflex (EPR) contributes to the potentiated pressor response. However, the mechanism(s) underlying this abnormal EPR activity remains unclear. This study tested the hypothesis that the heightened BP response to exercise in T1DM is mediated by EPR-induced sympathetic overactivity. Additionally, the study examined whether the single muscle afferents are sensitized by protein kinase C (PKC) activation in this disease. Sprague-Dawley rats were intraperitoneally administered either 50 mg/kg streptozotocin (T1DM) or saline (control). At 1–3 weeks after administration, renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) and mean arterial pressure (MAP) responses to activation of the EPR, mechanoreflex and metaboreflex, were measured in decerebrate animals. Action potential responses to mechanical and chemical stimulation were determined in group IV afferents with phosphorylated-PKCα (pPKCα) levels assessed in dorsal root ganglia (DRGs). Compared with control, EPR (58±18 vs. 96±33%, P<0.05), mechanoreflex (21±13 vs. 51±20%, P<0.05) and metaboreflex (40±20 vs. 88±39%, P<0.01) activation in T1DM rats evoked significant increases in RSNA as well as MAP. The response of group IV afferents to mechanical (18±24 vs. 61±45 spikes, P<0.01) and chemical (0.3±0.4 vs. 1.6±0.8 Hz, P<0.01) stimuli were significantly greater in T1DM than control. T1DM rats showed markedly increased pPKCα levels in DRGs compared with control. These data suggest that in T1DM, abnormally muscle reflex-evoked increases in sympathetic activity mediate exaggerations in BP. Further, sensitization of muscle afferents, potentially via PKC activation, may contribute to this abnormal circulatory responsiveness.

Keywords: sympathetic nerve activity, skeletal muscle exercise pressor reflex, blood pressure, muscle sensory afferents, type 1 diabetes mellitus

INTRODUCTION

In patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), the systolic blood pressure (BP) response to exercise is abnormally exaggerated 1. Since such excessive BP elevations can lead to adverse cardiac events and/or stroke during or immediately after a bout of exercise 2, 3, identifying the potential factors that mediate this abnormal circulatory response is physiologically and clinically relevant. However, the mechanism(s) underlying the potentiated BP responsiveness to physical activity in this disease remains unclear.

The exercise pressor reflex (EPR) originates in contracting skeletal muscle 4. During physical activity, the EPR is engaged upon stimulation of mechanically and metabolically sensitive group III and IV thin fiber muscle afferents (i.e., the mechanoreflex and metaboreflex components of the EPR)4. In healthy animals and humans, the EPR contributes significantly to the exercise-induced rise in BP primarily by increasing sympathetic nerve activity (SNA)4–6. Pioneering work in rats during the early stages of T1DM has demonstrated a heightened pressor response to static muscle contraction. This exaggerated BP response was shown to be mediated by an overactive EPR7. Moreover, additional experiments in T1DM rodents have shown that mechanoreflex overactivity mediates, in part, this abnormally high BP response 8. Although logical to suggest, whether the EPR and each of its individual reflex components induces these exaggerations in BP via abnormally large increases in SNA has yet to be established in T1DM.

In diabetes, peripheral neuropathy develops which can cause nerve pain and damage9, 10. In particular, damage to small myelinated group III and unmyelinated group IV fibers has been implicated in mechanical allodynia and hyperalgesia11, 12. Interestingly, it has been previously reported in diabetic BB/Wistar rats that saphenous nerve spontaneous activity is abnormally enhanced being mediated primarily by unmyelinated group IV fibers with only an occasional contribution from group III afferents 13, 14. Thus, group IV fibers may play a more prominent role in the generation of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. A previous study reported that rats with T1DM increased nociceptive responsiveness to mechanical stimuli in skin, suggesting that changes in the response properties of skin nociceptors contribute to the enhanced pain observed in diabetic peripheral neuropathy15. Given that group IV afferents involved in pain sensation are sensitized in T1DM it is logical to suggest that the heightened cardiovascular response to static exercise in this disease may be similarly mediated by a potentiated responsiveness of muscle afferents transmitting EPR sensory information.

Hyperglycemia, one of the pathophysiological characteristics of diabetes, leads to the formation and accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGE) 16which can cause neuronal damage mediated by increasing oxidative stress and neuronal apotosis17. Furthermore, the inflammatory cytokine high-mobility group box-protein 1 (HMGB1) is known to play a role in neuroinflammation 18. Both AGE and HMGB1 bind to the receptors for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) 16, 19. RAGE and protein kinase C (PKC) interact to modulate neuronal function such as slowing conduction velocity (i.e., indicative of peripheral neuronal damage)20. Moreover, evidence suggests that both mechanoreceptors21 and metaboreceptors22, 23are activated by PKC in sensory neurons. Additionally, a recent study reported that skin HMGB1-mediated increases in transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1)-evoked Ca2+ responses in DRG neurons were RAGE- and PKC-dependent in diabetic rats24. As such, it is also logical to suggest that alterations in skeletal muscle sensory neurons in T1DM may result from abnormalities in the RAGE/PKC pathway in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons that subserve the EPR.

In this study, therefore, it was hypothesized that the abnormally enhanced BP response to static exercise in T1DM is mediated by EPR-induced exaggerations in sympathetic activity that result, at least in part, from augmentations in the responsiveness of thin skeletal muscle afferent fibers via PKC signaling pathways. To test the hypothesis, we investigated 1) the renal SNA (RSNA) and mean arterial pressure (MAP) responses to activation of the EPR as well as the skeletal muscle mechanoreflex and metaboreflex in T1DM rats in vivo, 2) the alterations in action potential responses to mechanical and chemical stimulation in thin skeletal muscle afferents in vitro, 3) the impact of T1DM on plasma AGE and HMGB-1 and 4) the impact of T1DM on PKC activation in DRG neurons subserving skeletal muscle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article. A complete description of the methods used in this study is available in the online-only Data Supplement4, 6, 25–33.

Animals

All experiments were performed in adult male Sprague-Dawley rats. The animals were housed in standard rodent cages on 12:12-h light-dark cycles and were fed a standard diet and water ad libitum. T1DM (n = 21) was induced with a single intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) of 50 mg/kg streptozotocin 34. Streptozotocin was dissolved in saline solution and administered within 15 minutes after preparation. In the control group (n = 22), a benign vehicle (saline) was injected in lieu of streptozotocin. Each experiment was conducted 7–21 days after injection. All studies were performed in accordance with the US Department of Health and Human Services NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The procedures outlined were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Experimental Protocol

Experiment 1: Skeletal muscle reflex testing in vivo

MAP, heart rate (HR) and RSNA were continuously measured at rest and during distinctly separate stimulation of the EPR, mechanoreflex and metaboreflex. The EPR was activated by statically contracting the triceps surae muscles of the right hindlimb for 30 s via electrical stimulation of isolated L4 and L5 ventral roots. Isolated stimulation of mechanically sensitive afferent fibers was achieved by passively stretching the triceps surae of the right hindlimb for 30 s. To preferentially activate metabolically sensitive afferent fibers, capsaicin (0.3 μg/100 μl) was administered into the arterial supply of the right hindlimb.

Experiment 2: Single fiber recording in vitro

Using the extensor digitorum longus muscle-nerve preparation, single-unit action potential responses to mechanical and chemical stimulation were measured in thin skeletal muscle afferents (specifically group IV fibers). Response magnitude and mechanical threshold in group IV fibers were assessed in response to a ramp-shaped mechanical stimulation (0–196 mN, for 10 s). Discharge rate as well as latency to capsaicin stimulation (1μM, for 30 s) were also evaluated.

Experiment 3: Blood collection, ELISA and Western blotting

Fasting blood glucose levels were assessed by glucometer measurements. Insulin, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), HMGB1 and AGE concentrations were determined in blood plasma obtained from the tail vein using ELISA. Total (tPKCα) and phosphorylated (pPKCα) PKCαprotein levels were quantified in DRG (L3-L5) neurons by western blotting.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software. Group comparisons (control vs. T1DM) were made via Student’s unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney U non-parametric test. The level of statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. All data are expressed as mean ± SD.

RESULTS

Morphometric characteristics and fasting blood parameters as well as baseline hemodynamics and muscle thin fiber characteristics for control and T1DM rats are summarized in Table 1. T1DM animals showed significant body weight loss (P<0.01) as well as epididymal fat pad weight loss (3.67±0.56 vs. 2.23±0.66 g, P<0.05) as compared to control rats. Heart weight-to-tibial length ratios were significantly lower (P<0.01) and lung weight-to-body weight ratios significantly higher (P<0.05) in T1DM rats than control animals. There was no significant difference in EDL muscle weight, 0.18 ± 0.01 vs. 0.15 ± 0.02 g, between control and T1DM groups, respectively. Fasting blood glucose was significantly higher in T1DM animals as compared to control (P<0.01). Although not reaching statistical significance, plasma insulin in T1DM tended to be lower as compared to control animals (P=0.09). Plasma HbA1c was higher in T1DM compared with control (P<0.05). Additionally, baseline MAP and RSNA under 1% isoflurane anesthesia as well as after decerebration were not significantly different between groups. However, Baseline HR pre-and post-decerebration was significantly lower in T1DM rats compared with control (P<0.05). Moreover, the conduction velocity of skeletal muscle thin fiber afferents was not different between groups whereas the spontaneous activity of these afferents was significantly greater in T1DM animals (P<0.05). Of note, there were no significant differences in any variables between weeks two (7~14 days) and three (15~21 days) within each respective group (data not shown).

Table 1.

Morphometric characteristics, blood parameters, baseline hemodynamics and skeletal muscle thin fiber characteristics.

| Variables | Control | T1DM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphometric characteristics | |||

| Body weight, g | 362 ± 27 | 307 ± 20 | * |

| Heart weight/body weight, mg/g | 2.98 ± 0.5 | 3.01 ± 0.39 | |

| Heart weight/tibial length, mg/mm | 27.6 ± 3.3 | 24.0 ± 1.0 | * |

| Lung weight/body weight, mg/g | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | * |

| Fasting blood parameters | |||

| Blood glucose, mg/dL | 90 ± 16 | 266 ± 172 | * |

| Plasma insulin, ng/mL | 0.44 ± 0.08 | 0.26 ± 0.10 | |

| HbA1c, ng/mL | 2.9 ± 3.4 | 5.6 ± 2.7 | * |

| 1% isoflurane anesthesia | |||

| MAP, mmHg | 96 ± 17 | 106 ± 17 | |

| HR, beats/min | 402 ± 39 | 370 ± 42 | * |

| RSNA, signal to noise ratio | 5.4 ± 4.0 | 5.0 ± 1.6 | |

| After decerebration | |||

| MAP, mmHg | 90 ± 20 | 96 ± 13 | |

| HR, beats/min | 524 ± 45 | 465 ± 62 | * |

| RSNA, signal to noise ratio | 6.4 ± 3.8 | 7.2 ± 2.3 | |

| Skeletal muscle thin fiber characteristics | |||

| Conduction velocity, m/s | 0.99 ± 0.50 | 1.05 ± 0.43 | |

| Spontaneous activity, Hz | 0.08 ± 0.14 | 0.29 ± 0.37 | * |

Values are means ± SD. HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; RSNA, renal sympathetic nerve activity; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus.

P < 0.05 compared with control.

Body weight and blood glucose, control: n = 22, T1DM: n = 21; heart and lung weight and tibial length, control: n = 15, T1DM: n = 17; Plasma insulin, control: n = 15, T1DM: n = 12; Plasma HbA1c, control: n = 14, T1DM: n = 10; MAP, HR and RSNA, control: n = 9, T1DM: n = 10; conduction velocity and spontaneous activity, n = 15, T1DM: n = 17.

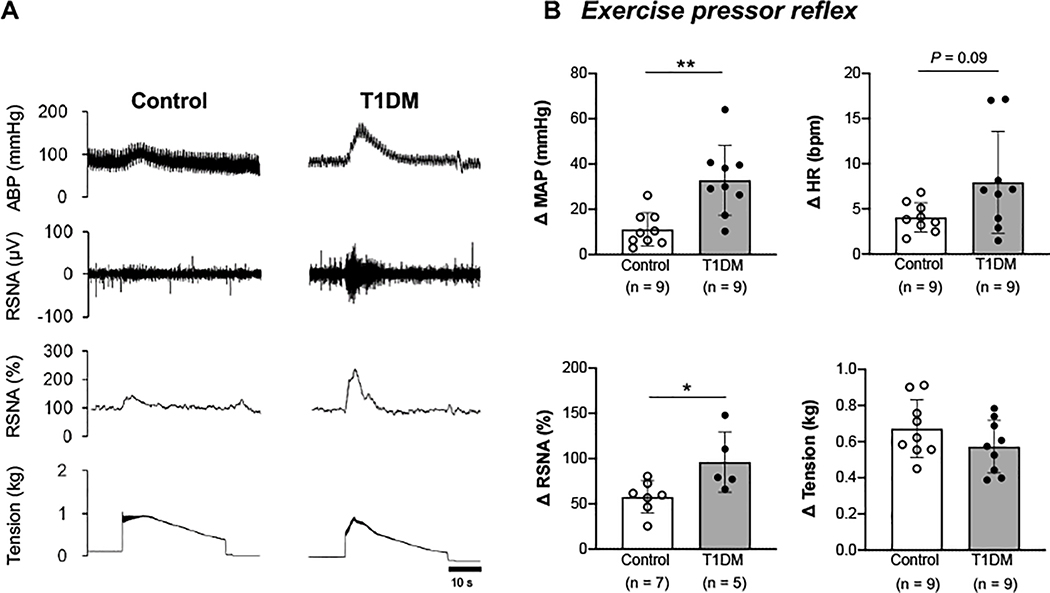

Skeletal Muscle Reflex Testing

The MAP and RSNA responses to activation of the EPR during static muscle contraction were significantly exacerbated in T1DM animals compared with control rats (P<0.05; Fig. 1, A and B). The HR change in response to EPR stimulation tended to be greater in the T1DM animals than the control rats, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.09). Importantly, the muscle tension developed during contraction was similar between the two groups.

Figure 1. Cardiovascular and sympathetic responses to activation of the exercise pressor reflex (EPR) by electrically induced muscle contraction in control and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) rats.

A, Representative tracings of arterial blood pressure (ABP) as well as raw and normalized renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA, %) during a 30-s static muscle contraction in a control and T1DM animal. B, Peak changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), RSNA, and developed tension in response to EPR activation. * P < 0.05 compared with control, ** P < 0.01 compared with control.

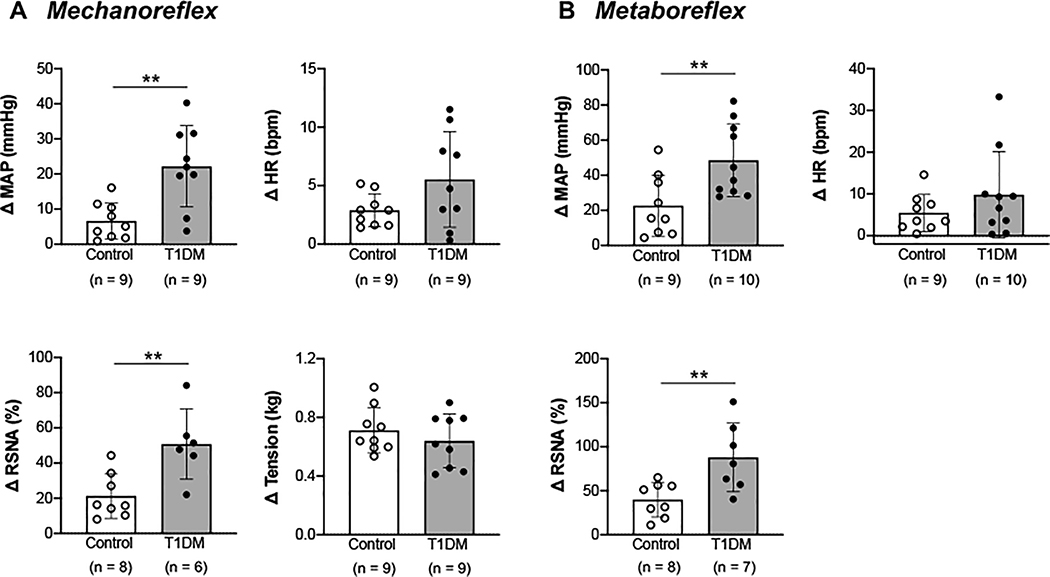

In the T1DM group, the changes in MAP and RSNA responses to activation of the muscle mechanoreflex induced via passive stretch were significantly augmented compared with the control group (P<0.01; Fig. 2A). The change in HR in response to mechanoreflex stimulation, however, was not significantly different between groups. The developed muscle tension during passive stretch was similar between groups. The MAP and RSNA responses to stimulation of the muscle metaboreflex during capsaicin administration were also enhanced in T1DM rats compared with control animals (P<0.01; Fig. 2B). Again, however, the HR response to metaboreflex stimulation did not significantly differ between the two groups.

Figure 2. Cardiovascular and sympathetic responses to activation of the muscle mechanoreflex via passive stretch and the muscle metaboreflex via intra-arterial capsaicin administration in control and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) rats.

Peak changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA), and developed tension in response to mechanoreflex stimulation(A)and metaboreflex stimulation(B). ** P < 0.01 compared with control.

Single Fiber Nerve Recordings

The position of the receptive fields in the group IV muscle afferents assessed in this study are shown in Fig. 3A and Fig. 4A. The majority of the receptive fields tended to be located near the musculotendinous junction. As noted previously, the conduction velocities were 0.99 ± 0.50 m/s (a range of 0.51–1.89 m/s) in control rats and 1.05 ± 0.43 m/s (a range of 0.52–1.91 m/s) in T1DM animals, which was not statistically different (Table 1). As compared to control, spontaneous activity in group IV fibers was significantly larger in T1DM (P<0.05; Table 1). Using a 30 s ramped mechanical stimulus to activate the afferent receptive field, the group IV fiber response magnitude was significantly greater in diabetic rats than in control animals (P<0.01; Fig. 3B), whereas there was no difference in the mechanical threshold between groups (P=0.14; Fig. 3C).These findings are readily apparent in the example raw recording illustrated in Fig. 3D. Capsaicin exposure evoked a significantly larger response in group IV fibers in diabetic rats compared with control animals (P=0.01; Fig. 4B). Additionally, the response latency to capsaicin stimulation was significantly shorter in T1DM rats (P<0.05; Fig. 4C). An original recording demonstrating these responses to capsaicin are shown in figure 4D.

Figure 3. Response of group IV muscle afferents to a ramped mechanical stimulus in control and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) rats.

A, Each spot represents the receptive field of a group IV muscle afferent. Shading illustrates the tendinous area. Changes in response magnitude and mechanical threshold are shown in B and C, respectively. D, Representative raw recording of individual group IV fiber activity and raw recording signal of the mechanical stimulator force output. White arrows indicate mechanical threshold. Control: n = 10, T1DM: n = 14. **P < 0.01 compared with control.

Figure 4. Response of group IV muscle afferents to a chemical stimulus (capsaicin) in control and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) rats.

A, Each spot represents the receptive field of a group IV muscle afferent. Shading illustrates the tendinous area. Changes in response magnitude and latency to capsaicin administration are shown in B and C, respectively. D, Representative raw recording of individual group IV fiber activity in response to capsaicin administration. White arrows indicate latency. Control: n = 6, T1DM: n = 7, * P < 0.05 compared with control, ** P < 0.01 compared with control.

ELISA and Western Blotting

Plasma HMGB1 levels were higher in T1DM compared with control (P<0.01; Fig. 5A). Plasma AGE did not differ between groups (Fig. 5B). The level of tPKCα was significantly lower in T1DM animals as compared to control rats (P<0.05; Fig. 5C and D), whereas pPKCα protein levels were significantly higher in T1DM (P<0.05; Fig. 5E).

Figure 5. HMGB1 and AGE concentrations in plasma and PKCα protein levels in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) of control and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) rats.

HMGB1 (Control: n = 9, T1DM: n = 10) and AGE (Control: n = 14, T1DM: n = 15) plasma concentrations are shown in A and B, respectively. C, Representative western blots (immunoblot: IB) for pPKCα (80 kDa), tPKCα (80 kDa) and GAPDH (37 kDa) in DRG tissue (intervening lanes between markers and samples removed for clarity). A magnification of the boxed area is shown on the right. Ratios for tPKCα and GAPDH as well as pPKCα and tPKCα protein levels are shown in D and E, respectively (Control: n = 10, T1DM: n = 10), A.U., arbitrary units, * P < 0.05 compared with control, ** P < 0.01 compared with control.

DISCUSSION

The major novel findings from this investigation were (1) in vivo, the sympathetic response to activation of the EPR, as well as its mechanically (i.e. mechanoreflex) and chemically (i.e. metaboreflex) sensitive components, was abnormally potentiated in untreated T1DM rats, (2) in vitro, skeletal muscle group IV fibers were sensitized to both mechanical and chemical stimuli in T1DM, and (3) phosphorylation levels of PKCα in DRG subserving skeletal muscle were augmented in diabetic animals. These findings suggest that the heightened BP response to static exercise in T1DM is mediated by EPR-evoked exaggerations in sympathetic activity. Additionally, although causality is not directly verified, the data would suggest that this enhanced EPR is associated with T1DM-induced sensitization of skeletal muscle afferent fibers and/or alterations in the PKC signaling pathway within the DRG.

EPR-Mediated Sympathetic Overactivity in Diabetic Animals

Consistent with recent studies7, EPR-mediated increases in BP were significantly augmented in T1DM as compared to control in the current investigation. Excessive pressor responses to static exercise in other chronic diseases such as hypertension and peripheral arterial disease, common comorbidities of T1DM35, 36, are well established. Increasing evidence suggests a pivotal role for skeletal muscle reflex-evoked sympathetic nerve overactivation in driving the abnormally high BP response in these other chronic cardiovascular diseases37, 38. Our findings add to this body of evidence by demonstrating for the first time that alterations in sympathetic responsiveness likewise contribute significantly to EPR overactivity in the early stages of untreated T1DM.

Previous studies have demonstrated that with the development of T1DM, endothelial cell dysfunction manifests. This dysfunction is characterized by decreased vasodilatory responsiveness to NO 39–41 as well as higher levels of endothelin 42, both of which may contribute to increases in the sensitivity of the vasculature to sympathetic adrenergic vasoconstrictor signaling. Therefore, it is possible that the exaggerated BP responses to static exercise noted in T1DM could be due to such vascular abnormalities. Alternatively, it is possible that increased vascular sensitivity to EPR-induced sympathetic adrenergic stimulation could play a role in the potentiation of the BP response to static exercise observed in this disease. Although this may contribute to the enhanced BP response to skeletal muscle contraction to some extent, it seems unlikely to be the primary cause. Rather, the results from the current study strongly suggest that the exaggerated pressor response to activation of the EPR in T1DM is mediated by abnormally enhanced increases in SNA.

Mechanoreflex and Metaboreflex-Induced Sympathetic Dysfunction in Diabetic Animals

Although the pressor response to passive stretch was augmented in T1DM as compared to control, the magnitude of the BP increase was smaller than that reported previously8. In addition, baseline HR in both groups tended to be higher compared to earlier studies7, 8. Despite such differences, T1DM exacerbated the RSNA and MAP responses to stimulation of both the mechanoreflex and metaboreflex. With regard to the mechanoreflex, our findings align with previous studies demonstrating abnormally augmented pressor responses to muscle stretch8 in T1DM rats. However, when considering the metaboreflex, previous studies in young T1DM patients reported that the BP response to post-exercise muscle ischemia (PEMI), a maneuver designed to selectively activate the metaboreflex, was blunted due in part to reductions in vasoconstrictor capacity43. Although the reasons for the discrepant results between our animal investigation and the previous human study with regard to the metaboreflex is not readily apparent, it could be due to the fact that in the latter young diabetic patients received insulin treatment whereas the animal populations of the current study did not. Alternatively, capsaicin sensitive TRPV1-mediated metaboreflex activation was applied in the current animal study while PEMI-mediated metaboreflex stimulation was utilized in the human investigation.

With regard to TRPV1, it should be noted that recently reported data suggests that that the TRPV1 receptor may not play a role in evoking the skeletal muscle reflex in normal healthy rats44. This is in contrast to other investigations conducted in animal models of disease such as hypertension29, heart failure45 and peripheral arterial disease46, in which altered TRPV1 responsiveness has been demonstrated to contribute significantly to EPR dysfunction via abnormal metaboreflex functioning. Likewise, it is noted that TRPV1 dysfunction has been shown to manifest in T1DM animals47, suggesting its potential contribution to the metaboreflex regulation of BP and sympathetic responsiveness in this disease. Clearly, further investigation in both humans and animals is warranted before definitive conclusions can be drawn about the physiological role of TRPV1 in mediating metaboreflex activity in both health and disease. Regardless of its physiological action, it is well accepted that stimulation of TRPV1 is a reliable tool to experimentally activate metabolically sensitive afferent fibers and was used for this purpose in the current investigation. As such, the current study does extend previous findings by providing evidence that the sympathetic response mediated by the experimental activation of both mechanoreflex and metaboreflex afferent fibers is exaggerated in the early-stages of untreated T1DM.

Spontaneous Hyperactivity in Skeletal Muscle Group IV Fibers from Diabetic Animals

Peripheral sensory fiber damage results in local inflammatory responses and the development of diabetic neuropathic pain 48. To our best knowledge, we observed for the first time that group IV afferents innervating skeletal muscle display a spontaneous hyperactivity in the absence of any intentional experimental stimuli in diabetic animals (Table 1). This is consistent with earlier studies demonstrating that spontaneous hyperactivity is observed in the skin-saphenous nerve, especially in nociceptive C-fibers, from early stages of diabetes15. It is suggested that spontaneous hyperactivity in the skeletal muscle sensory afferents of diabetic animals may be responsible for the extemporaneous muscle pain, which often accompanies diabetic neuropathy. Moreover, the hyperactivity at rest could potentially prime these afferents for the overactivity noted in T1DM during mechanical and chemical stimulation that may contribute to the EPR dysfunction observed in this disease.

Mechanically Sensitized Skeletal Muscle Group IV Fibers in Diabetic Rats

In the current study, group IV muscle afferents from T1DM rats demonstrated a greater response magnitude to mechanical stimuli than control animals (Fig.3B). Further, while differences between groups in the mechanical threshold did not reach statistical significance, it was 40% less in diabetic animals than control rats (Fig.3C). Albeit in a different population of afferent fibers, other studies have reported similar findings in saphenous nerve single C fibers from skin that showed a marked hyper-responsiveness to mechanical stimuli in vivo14 as well as in vitro15in an established rat model of painful diabetic neuropathy. Collectively, these findings suggest that the exaggerated muscle mechanoreflex function observed in T1DMis due, at least in part, to the potentiated responsiveness of thin fiber muscle afferents to mechanical stimuli.

Piezo-type mechanosensitive ion channel component 2 (Piezo2) is known to be expressed in DRG neurons, and to play a crucial role in touch and pain sensation 49. Specifically, within in vivo rat models, Piezo2-mediated mechanotransduction has been shown to be involved in evoking neuropathic pain in response to mechanical stimuli50. Utilizing the relatively selective mechano-sensitive channel inhibitor GsMTx4, a recent study suggested that Peizo2 may likewise mediate an exaggeration in mechanoreflex activity within the early stages of diabetes8. As a result of these findings, it is tempting to speculate that diabetes-induced mechanical sensitization of muscle afferents could be mediated by alterations in Piezo2 channel function. However, the proteins that underlie mechano-sensation as it relates to the EPR remain largely undetermined. Thus, further research is needed prior to drawing definitive conclusions with regard to the mechanisms responsible for abnormal mechano-transduction in diabetes.

Chemically Sensitized Skeletal Muscle Group IV Fibers in Diabetic Rats

Increasing evidence suggests that TRPV1 plays a role in both neuronal damage and pain in diabetic rats22, 51, 52. Importantly, the current study is the first to demonstrate that group IV muscle afferent discharge in response to capsaicin (a TRPV1 agonist) is heightened in T1DM (Fig. 4B and C). It is known that TRPV1 is directly sensitized by acute high-glucose24, 53. Indeed, the alterations in TRPV1 channel function may underlie the variety of pain syndromes induced by T1DM 52. We have previously shown that TRPV1 receptors in group III and/or IV muscle afferents may contribute importantly to activation of the EPR during skeletal muscle contraction in rats54. Taken together, it is plausible that muscle metaboreflex function is potentiated in diabetes as a result of augmentations in the responsiveness of group IV fibers via TRPV1 activation.

Increased Plasma HMGB1 Levels and PKC Activation in DRG Neurons from Diabetic Animals

High glucose concentrations cause sensory neuronal sensitization through the HMGB1/RAGE pathway24. RAGE is activated by AGE 16 or HMGB1 19. In the present study, plasma HMGB1 was significantly higher in T1DM than control (Fig. 5A), while plasma AGE did not differ among groups (Fig. 5B). This is consistent with reports that HMGB1 levels are increased in the plasma 55 and skin 24 of patients and animals with T1DM. It is known that HMGB1 acts more rapidly to activate RAGE 19 whearas AGE must accumulate over time (months to years in vivo)16. Thus, contributions of this signaling pathway to the findings of the current study, would most likely occur via HMGB1 activation of RAGE rather than AGE. We observed that pPKCα protein expression was upregulated (Fig. 5E), and tPKCα protein downregulated in DRG tissue from T1DM rats (Fig. 5D). These findings agree with a previous study demonstrating an increase in the phosphorylation of PKCα in diabetes 56. In contrast, investigations assessing tPKC in diabetic animals have produced conflicting results reporting both reductions and enhancements in tPKC levels in DRG neurons 57, 58. As stated previously, both RAGE and PKC interact to modulate neuronal function20. Moreover, RAGE is known to stimulate phosphorylation of PKC. Thus, given the observed increases in HMGB1 it is plausible to suggest that the HMGB1/RAGE signaling pathway significantly stimulated phosphorylation of PKCα in the early-stage diabetic rats of the current study.

The chemical sensitization of these afferents could be explained by PKC-induced activation of TRPV1 23. It has been previously demonstrated that TRPV1 is phosphorylated through a PKC-dependent mechanism in the DRG of diabetic rats 22, 23.With regard to mechanical sensitization of these afferents, an earlier study suggested that piezo2 channels may contribute to PKC-mediated sensitization59. As such, the mechanical sensitization of group IV muscle afferents in T1DM may be also induced by augmented activation of PKCα in DRG neurons.

Limitations

Limitations to this investigation are acknowledged. Firstly, only male rats were examined. Male rats were used as it has been reported that in the early stages of streptozotocin-induced T1DM (up to 3 weeks after treatment), the exaggerated pressor response evoked by the EPR is not different between sexes7. Nevertheless, the fact that female rats were not studied in the current investigation should be taken into consideration when interpreting results. Secondly, it is possible that the mechanical compression utilized in single fiber recording experiments in vitro does not wholly mimic muscle contraction conditions during exercise in vivo. As such, it is further possible that the afferents of the EDL would respond differently in vivo. That being acknowledged, thin-fiber muscle afferents are known to be stimulated by mechanical deformation of their receptive fields during muscle contraction60. Clearly, in this study, mechanical deformation of the receptive fields of the afferents investigated elicited enhanced responses in T1DM. Thirdly, DRG neurons from L3, L4 and L5 were collected to assess PKCα whereas most cell bodies from sensory neurons extending from the EDL are localized to DRG from L4 only61. Moreover, it remains unclear whether PKC activation directly modulates the action potentials of muscle afferents as well as the exaggerated pressor responses they evoke in T1DM. Additional studies are warranted to address these noted limitations.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study suggest the sympathetic response to activation of the EPR, as well as its mechanoreflex and metaboreflex functional components, is abnormally heightened in diabetes resulting, at least in part, from the increased sensitivity of group IV skeletal muscle afferent fibers to mechanical and chemical stimuli. This sensitization is possibly mediated via activation of the HMGB1/RAGE/PKC pathway. Importantly, these changes likely contribute significantly to the EPR-mediated exaggerated BP response to static exercise in T1DM.

PERSPECTIVES

Exercise has been shown to normalize abnormal circulatory regulation in cardiovascular disease 62, 63. Moreover, evidence suggests that exercise improves physical fitness and reduces insulin resistance in people with T1DM 64, 65. However, the excessive BP response to physical activity in this disease increases the risk for development of an adverse cardiac event and/or stroke during or immediately after a bout of exercise 2, 3. As a result, the frequency and intensity of exercise prescription is often limited66. Although not specifically addressed in the current investigation, an increased risk for the development of hypoglycemia during exercise is also a significant barrier to regular physical activity in T1DM patients66. For example, evidence suggests that moderate-to-vigorous exercise increases the risk of hypoglycemia between 38 and 80 % in T1DM patients67, 68. At this time, the specific duration and intensity of physical activity that can be safely prescribed to maximize benefits remains largely unknown69. Dissection of the mechanisms underlying the abnormal cardiovascular, and for that matter metabolic, responses to exercise in T1DM may prove beneficial to the development of novel therapeutic strategies targeted at reducing the risks associated with physical activity. Based on the results of the current study, targeting EPR-induced sympathetic overactivity and/or the receptor/signaling pathways responsible for muscle afferent sensitization may represent viable approaches to treating the excessive BP response associated with T1DM.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is NEW?

Sympathetic responses to activation of the exercise pressor reflex are exaggerated in type 1 diabetic rats.

Action potential responses to mechanical and chemical stimulation are potentiated in group IV afferents of type 1 diabetic rats.

Phosphorylated-PKCα is increased in the dorsal root ganglia of type 1 diabetic rats.

What is relevant?

The study identifies sympathetic overactivity and skeletal muscle afferent sensitization as potential therapeutic targets for improving/preventing the abnormal high exercise blood pressure in type 1 diabetes.

Summary

In type 1 diabetes, skeletal muscle reflex-evoked sympathetic overactivity and sensitization of muscle afferents (potentially via phosphorylated-PKCα) significantly contribute to the potentiated circulatory response to exercise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Martha Romero and Julius Lamar, Jr. for their expert technical assistance.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This research was supported by grants from the Southwestern School of Health Professions Interdisciplinary Research Grant Program (to M.M.), the Lawson & Rogers Lacy Research Fund in Cardiovascular Disease (to J.H.M.), the JSPS KAKENHI (JP17K01769 to N.H.), the National Institutes of Health Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL-133179 to M.M., S.A.S. and W.V.), and the UT Southwestern O’Brien Kidney Research Core Center (P30DK079328 to W.V.).

Abbreviations

- AGE

advanced glycation end products

- BP

blood pressure

- EPR

exercise pressor reflex

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- EDL

extensor digitorum longus

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HbA1c

hemoglobin A1c

- HMGB1

high mobility group box 1

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MA

mechanically activated

- NO

nitric oxide

- PKC

protein kinase C

- RAGE

receptor for advanced glycation end products

- RSNA

renal sympathetic nerve activity

- SNA

sympathetic nerve activity

- T1DM

type 1 diabetes mellitus

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matteucci E, Rosada J, Pinelli M, Giusti C, Giampietro O. Systolic blood pressure response to exercise in type 1 diabetes families compared with healthy control individuals. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1745–1751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoberg E, Schuler G, Kunze B, Obermoser AL, Hauer K, Mautner HP, Schlierf G, Kubler W. Silent myocardial ischemia as a potential link between lack of premonitoring symptoms and increased risk of cardiac arrest during physical stress. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:583–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Tofler GH, Sherwood JB, Goldberg RJ, Muller JE. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by heavy physical exertion. Protection against triggering by regular exertion. Determinants of myocardial infarction onset study investigators. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1677–1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCloskey DI, Mitchell JH. Reflex cardiovascular and respiratory responses originating in exercising muscle. J Physiol. 1972;224:173–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mark AL, Victor RG, Nerhed C, Wallin BG. Microneurographic studies of the mechanisms of sympathetic nerve responses to static exercise in humans. Circ Res. 1985;57:461–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell JH, Kaufman MP, Iwamoto GA. The exercise pressor reflex: Its cardiovascular effects, afferent mechanisms, and central pathways. Annu Rev Physiol. 1983;45:229–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grotle AK, Garcia EA, Huo Y, Stone AJ. Temporal changes in the exercise pressor reflex in type 1 diabetic rats. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2017;313:H708–h714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grotle AK, Garcia EA, Harrison ML, Huo Y, Crawford CK, Ybarbo KM, Stone AJ. Exaggerated mechanoreflex in early-stage type 1 diabetic rats: Role of piezo channels. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2019;316:R417–r426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obrosova IG. Diabetic painful and insensate neuropathy: Pathogenesis and potential treatments. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2009;6:638–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomlinson DR, Gardiner NJ. Glucose neurotoxicity. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2008;9:36–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapur D Neuropathic pain and diabetes. Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews. 2003;19 Suppl 1:S9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llewelyn JG, Gilbey SG, Thomas PK, King RH, Muddle JR, Watkins PJ. Sural nerve morphometry in diabetic autonomic and painful sensory neuropathy. A clinicopathological study. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1991;114 ( Pt 2):867–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burchiel KJ, Russell LC, Lee RP, Sima AA. Spontaneous activity of primary afferent neurons in diabetic bb/wistar rats. A possible mechanism of chronic diabetic neuropathic pain. Diabetes. 1985;34:1210–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Levine JD. Hyper-responsivity in a subset of c-fiber nociceptors in a model of painful diabetic neuropathy in the rat. Neuroscience. 2001;102:185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki Y, Sato J, Kawanishi M, Mizumura K. Lowered response threshold and increased responsiveness to mechanical stimulation of cutaneous nociceptive fibers in streptozotocin-diabetic rat skin in vitro--correlates of mechanical allodynia and hyperalgesia observed in the early stage of diabetes. Neuroscience research. 2002;43:171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh VP, Bali A, Singh N, Jaggi AS. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications. The Korean journal of physiology & pharmacology : official journal of the Korean Physiological Society and the Korean Society of Pharmacology. 2014;18:1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byun K, Yoo Y, Son M, Lee J, Jeong GB, Park YM, Salekdeh GH, Lee B. Advanced glycation end-products produced systemically and by macrophages: A common contributor to inflammation and degenerative diseases. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2017;177:44–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeda T, Ozaki M, Kobayashi Y, Kiguchi N, Kishioka S. Hmgb1 as a potential therapeutic target for neuropathic pain. Journal of pharmacological sciences. 2013;123:301–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saleh A, Smith DR, Tessler L, Mateo AR, Martens C, Schartner E, Van der Ploeg R, Toth C, Zochodne DW, Fernyhough P. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products (rage) activates divergent signaling pathways to augment neurite outgrowth of adult sensory neurons. Exp Neurol. 2013;249:149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zochodne DW. Mechanisms of diabetic neuron damage: Molecular pathways. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2014;126:379–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Castro A, Drew LJ, Wood JN, Cesare P. Modulation of sensory neuron mechanotransduction by pkc- and nerve growth factor-dependent pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4699–4704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong S, Wiley JW. Early painful diabetic neuropathy is associated with differential changes in the expression and function of vanilloid receptor 1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:618–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang S, Joseph J, Ro JY, Chung MK. Modality-specific mechanisms of protein kinase c-induced hypersensitivity of trpv1: S800 is a polymodal sensitization site. Pain. 2015;156:931–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bestall SM, Hulse RP, Blackley Z, Swift M, Ved N, Paton K, Beazley-Long N, Bates DO, Donaldson LF. Sensory neuronal sensitisation occurs through hmgb-1-rage and trpv1 in high-glucose conditions. J Cell Sci. 2018;131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith SA, Mitchell JH, Garry MG. Electrically induced static exercise elicits a pressor response in the decerebrate rat. J Physiol. 2001;537:961–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizuno M, Mitchell JH, Crawford S, Huang CL, Maalouf N, Hu MC, Moe OW, Smith SA, Vongpatanasin W. High dietary phosphate intake induces hypertension and augments exercise pressor reflex function in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2016;311:R39–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufman MP, Waldrop TG, Rybicki KJ, Ordway GA, Mitchell JH. Effects of static and rhythmic twitch contractions on the discharge of group iii and iv muscle afferents. Cardiovasc Res. 1984;18:663–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stebbins CL, Brown B, Levin D, Longhurst JC. Reflex effect of skeletal muscle mechanoreceptor stimulation on the cardiovascular system. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1988;65:1539–1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizuno M, Murphy MN, Mitchell JH, Smith SA. Antagonism of the trpv1 receptor partially corrects muscle metaboreflex overactivity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Physiol. 2011;589:6191–6204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith SA, Williams MA, Mitchell JH, Mammen PP, Garry MG. The capsaicin-sensitive afferent neuron in skeletal muscle is abnormal in heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:2056–2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taguchi T, Sato J, Mizumura K. Augmented mechanical response of muscle thin-fiber sensory receptors recorded from rat muscle-nerve preparations in vitro after eccentric contraction. Journal of neurophysiology. 2005;94:2822–2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins WR, Jr., Nulsen FE, Randt CT. Relation of peripheral nerve fiber size and sensation in man. Archives of neurology. 1960;3:381–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hotta N, Kubo A, Mizumura K. Chondroitin sulfate attenuates acid-induced augmentation of the mechanical response in rat thin-fiber muscle afferents in vitro. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2019;126:1160–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deeds MC, Anderson JM, Armstrong AS, Gastineau DA, Hiddinga HJ, Jahangir A, Eberhardt NL, Kudva YC. Single dose streptozotocin-induced diabetes: Considerations for study design in islet transplantation models. Laboratory animals. 2011;45:131–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treatment of hypertension in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:199–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zander E, Heinke P, Reindel J, Kohnert KD, Kairies U, Braun J, Eckel L, Kerner W. Peripheral arterial disease in diabetes mellitus type 1 and type 2: Are there different risk factors? Vasa. 2002;31:249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mizuno M, Murphy MN, Mitchell JH, Smith SA. Skeletal muscle reflex-mediated changes in sympathetic nerve activity are abnormal in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H968–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xing J, Lu J, Li J. Role of tnf-α in regulating the exercise pressor reflex in rats with femoral artery occlusion. Frontiers in physiology. 2018;9:1461–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saenz de Tejada I, Goldstein I, Azadzoi K, Krane RJ, Cohen RA. Impaired neurogenic and endothelium-mediated relaxation of penile smooth muscle from diabetic men with impotence. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1025–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bucala R, Tracey KJ, Cerami A. Advanced glycosylation products quench nitric oxide and mediate defective endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in experimental diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:432–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen RA. The role of nitric oxide and other endothelium-derived vasoactive substances in vascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1995;38:105–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Idris-Khodja N, Ouerd S, Mian MOR, Gornitsky J, Barhoumi T, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Endothelin-1 overexpression exaggerates diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction by altering oxidative stress. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29:1245–1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberto S, Marongiu E, Pinna M, Angius L, Olla S, Bassareo P, Tocco F, Concu A, Milia R, Crisafulli A. Altered hemodynamics during muscle metaboreflex in young type 1 diabetes patients. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2012;113:1323–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ducrocq GP, Estrada JA, Kim JS, Kaufman MP. Blocking the transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 does not reduce the exercise pressor reflex in healthy rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2019;317:R576–r587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang HJ, Li YL, Gao L, Zucker IH, Wang W. Alteration in skeletal muscle afferents in rats with chronic heart failure. The Journal of physiology. 2010;588:5033–5047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xing J, Lu J, Li J. Contribution of nerve growth factor to augmented trpv1 responses of muscle sensory neurons by femoral artery occlusion. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2009;296:H1380–1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pabbidi RM, Yu SQ, Peng S, Khardori R, Pauza ME, Premkumar LS. Influence of trpv1 on diabetes-induced alterations in thermal pain sensitivity. Mol Pain. 2008;4:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Calcutt NA, Jolivalt CG, Fernyhough P. Growth factors as therapeutics for diabetic neuropathy. Current drug targets. 2008;9:47–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coste B, Mathur J, Schmidt M, Earley TJ, Ranade S, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Piezo1 and piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science. 2010;330:55–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park SP, Kim BM, Koo JY, Cho H, Lee CH, Kim M, Na HS, Oh U. A tarantula spider toxin, gsmtx4, reduces mechanical and neuropathic pain. Pain. 2008;137:208–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cui YY, Xu H, Wu HH, Qi J, Shi J, Li YQ. Spatio-temporal expression and functional involvement of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 in diabetic mechanical allodynia in rats. PloS one. 2014;9:e102052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khomula EV, Viatchenko-Karpinski VY, Borisyuk AL, Duzhyy DE, Belan PV, Voitenko NV. Specific functioning of cav3.2 t-type calcium and trpv1 channels under different types of stz-diabetic neuropathy. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1832:636–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lam D, Momeni Z, Theaker M, Jagadeeshan S, Yamamoto Y, Ianowski JP, Campanucci VA. Rage-dependent potentiation of trpv1 currents in sensory neurons exposed to high glucose. PloS one. 2018;13:e0193312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith SA, Leal AK, Williams MA, Murphy MN, Mitchell JH, Garry MG. The trpv1 receptor is a mediator of the exercise pressor reflex in rats. J Physiol. 2010;588:1179–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Devaraj S, Dasu MR, Park SH, Jialal I. Increased levels of ligands of toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1665–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shangguan Y, Hall KE, Neubig RR, Wiley JW. Diabetic neuropathy: Inhibitory g protein dysfunction involves pkc-dependent phosphorylation of goalpha. Journal of neurochemistry. 2003;86:1006–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cameron NE, Cotter MA, Jack AM, Basso MD, Hohman TC. Protein kinase c effects on nerve function, perfusion, na(+), k(+)-atpase activity and glutathione content in diabetic rats. Diabetologia. 1999;42:1120–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ways DK, Sheetz MJ. The role of protein kinase c in the development of the complications of diabetes. Vitamins and hormones. 2000;60:149–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dubin AE, Schmidt M, Mathur J, Petrus MJ, Xiao B, Coste B, Patapoutian A. Inflammatory signals enhance piezo2-mediated mechanosensitive currents. Cell reports. 2012;2:511–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murphy MN, Mizuno M, Mitchell JH, Smith SA. Cardiovascular regulation by skeletal muscle reflexes in health and disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1191–1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peyronnard JM, Charron LF, Lavoie J, Messier JP. Motor, sympathetic and sensory innervation of rat skeletal muscles. Brain Res. 1986;373:288–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mizuno M, Iwamoto GA, Vongpatanasin W, Mitchell JH, Smith SA. Exercise training improves functional sympatholysis in spontaneously hypertensive rats through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H242–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mizuno M, Iwamoto GA, Vongpatanasin W, Mitchell JH, Smith SA. Dynamic exercise training prevents exercise pressor reflex overactivity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H762–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laaksonen DE, Atalay M, Niskanen LK, Mustonen J, Sen CK, Lakka TA, Uusitupa MI. Aerobic exercise and the lipid profile in type 1 diabetic men: A randomized controlled trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:1541–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chimen M, Kennedy A, Nirantharakumar K, Pang TT, Andrews R, Narendran P. What are the health benefits of physical activity in type 1 diabetes mellitus? A literature review. Diabetologia. 2012;55:542–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brazeau AS, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Strychar I, Mircescu H. Barriers to physical activity among patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2108–2109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bachmann S, Hess M, Martin-Diener E, Denhaerynck K, Zumsteg U. Nocturnal hypoglycemia and physical activity in children with diabetes: New insights by continuous glucose monitoring and accelerometry. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:e95–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Metcalf KM, Singhvi A, Tsalikian E, Tansey MJ, Zimmerman MB, Esliger DW, Janz KF. Effects of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity on overnight and next-day hypoglycemia in active adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1272–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tully C, Aronow L, Mackey E, Streisand R. Physical activity in youth with type 1 diabetes: A review. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16:85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.