Abstract

Objectives:

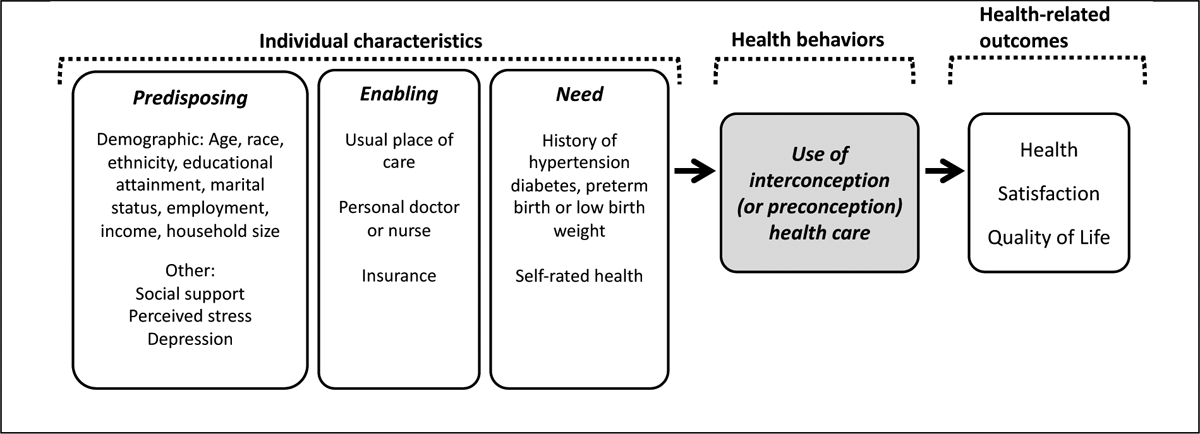

Preventive health care between pregnancies may benefit future pregnancies and women’s long-term health, yet such care is frequently incomplete. We used Andersen’s Model of Health Services Use to identify factors associated with receipt of interconception care.

Methods:

This secondary analysis uses data from a trial that recruited women from four health centers in the Baltimore metropolitan area. We used data on factors associated with Andersen’s model reported up to 15 months postpartum. Factors included health history (diabetes, hypertension, prematurity), self-rated health, demographics (age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment, income, parity), predisposing factors (depression, stress, social support), and enabling factors (usual place of care, personal doctor or nurse, insurance). Relative risk regression modeled the relationship between these factors and a dependent variable defined as completing both a postpartum visit and one subsequent health care visit. Models also accounted for time since birth, clustering by site, and trial arm.

Results:

We included 376 women followed a mean of 272 days postpartum (SD 57), of whom 226 (60%) completed a postpartum and subsequent visit. Women were predominantly non-Hispanic Black (84%) and low income (50% household income < $20,000/year). In regression, two enabling factors were associated with increased receipt of care: having a personal doctor or nurse (RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.11 – 1.70) and non-Medicaid insurance (RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.09 – 2.56).

Conclusions for Practice:

Enabling factors were associated with receipt of recommended care following birth. These factors may be modifiable components of efforts to improve care during this critical life course period.

Keywords: Preconception care, interconception care, preventive health care, health systems, quality of care

INTRODUCTION

Interconception care describes health care delivered between pregnancies with a goal of improving outcomes during potential future pregnancies (Lu et al., 2006). This type of preventive health care is a recommended strategy to improve birth outcomes and decrease health inequities (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Shapiro-Mendoza, 2016). However, only 30% of women report receiving pregnancy-relevant health counseling between pregnancies (Oza-Frank, Gilson, Keim, Lynch, & Klebanoff, 2014). Though interconception care is recommended for all women, women with existing health risks may especially benefit from care.

During the interconception period it may be particularly valuable to address health risks related to complications of pregnancy, such as gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, and preterm birth. These conditions are associated with modifiable risks, are consistently identified during pregnancy due to well-accepted screening guidelines (Mission, Catov, Deihl, Feghali, & Scifres, 2017), and are predictive of both future pregnancy complications (Laughon, Albert, Leishear, & Mendola, 2014; Yang et al., 2016) and long-term cardiovascular risk (Mosca et al., 2011). Because of the ongoing risks associated with complications of pregnancy, professional groups recommend that women who experience these complications have at least two health care visits in the year following birth (ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2010; Metzger et al., 2007; RW. Gifford, PA. August, G. Cunningham, LA. Green, 2000). These visits should include a postpartum visit in the weeks following pregnancy, as recommended for all women, and at least one additional visit to continue to address chronic health risks. Yet, compared to women with no complications of pregnancy, women with complications during pregnancy report only slightly higher rates of health care utilization following a birth (Bennett et al., 2014).

Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use provides a theoretical framework of factors associated with health care utilization (Andersen, 1995). This model suggests that health care utilization is driven by need for care, as well as by predisposing and enabling characteristics. The Andersen model suggests several possible explanations for low rates of interconception care. First, women both with and without health risks may be unaware of their need for care (Andersen, 1995). Second, women may have predisposing factors (e.g. depression, competing demands related to work responsibilities) that influence their health care utilization. Third, enabling resources, such as health insurance or a usual place of care may be absent.

The aim of this study was to use Andersen’s model to determine which factors drive health care utilization in the period following birth. We used data from four urban primary care sites in the Baltimore, Maryland metropolitan area, where women have high rates of chronic illness and pregnancy complications. We hypothesized that the need for care, based on self-reported risk factors or overall health, would be associated with health care utilization in this period.

METHODS

Population

This is a secondary analysis of data from a cluster randomized trial of postpartum women designed to test receipt of interconception care in the pediatric setting. Details of the intervention have been reported previously (Chilukuri et al., 2018). In brief, women were recruited during infant well visits at four pediatric primary care sites in the Baltimore, Maryland area. Women were eligible for enrollment up to one year after birth. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy at the time of recruitment, and inability to complete the study assessments in English or Spanish. Enrollment occurred from October 2013 – March 2015. Randomization was completed for 415 women. Data was collected by participant self-report in-person at enrollment and during telephone follow-up six and 12 months after enrollment. Participants were compensated with $25 for the initial study visit and for the two follow-up phone calls (if completed). All participants provided written informed consent. This study was conducted in accord with prevailing ethical principles and was approved by the Institutional Review Board a Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

In this analysis, we included 376 women who participated in this trial. We included all women who had a study interview at some point between 6 – 15 months postpartum, representing 379 women. Three of women were missing data on key analytic variables, leading to a final sample of 376 women. For each woman, we included all study data collected up until 15 months postpartum. Study instruments were developed using validated items widely used in national surveys or in other studies on related topics. Specific item sources are described further below.

Outcome – interconception preventive care

Data included assessment of a postpartum visit collected at enrollment (“after the birth of your most recent child, did you have your six-week postpartum check-up?”). Completion of a general preventive care visit was collected at all time points (“since the birth of your most recent child, have you visited a health care worker for a checkup?”). We created a dichotomous variable of affirmative response to both of these questions versus other.

Need for care

Health risks were assessed at enrollment. We focused on diabetes, hypertension, preterm birth, and low birth weight. Each of these conditions is predictive of future adverse pregnancy outcomes and long-term cardiovascular health, and each is associated with a recommendation for additional health care in the year following birth (Bloomfield & Wilt, 2011; Metzger et al., 2007; RW. Gifford, PA. August, G. Cunningham, LA. Green, 2000). Hypertension and diabetes were each assessed using two separate items asking about conditions during the pre-pregnancy period and conditions during pregnancy. History of preterm birth and low birth weight reflected all previous pregnancies. Preterm was assessed using a single item “during any of your previous pregnancies did you have any premature labor?” Low birth weight was assessed by asking about birth weight for each child. These pregnancy complications (hypertension, diabetes, and preterm birth or low birth weight) represented our overall classification of risk.

We also assessed self-rated health with the question “how would you describe your own health?” Response items included excellent, very good, good, fair, poor and were converted to a five-point numeric scale. This item is used in several national surveys and has been associated with important health outcomes, including mortality (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018; Schnittker & Bacak, 2014).

Predisposing factors

According to Andersen’s model, predisposing factors reflect an individual’s demographic characteristics, as well as social status and ability to respond to stressors (Andersen, 1995; Babitsch, Gohl, & von Lengerke, 2012). In this category, we therefore included demographics, as well as depression, social support, and perceived stress. In addition to being theoretically consistent with Andersen’s model, depression, social support, and perceived stress have been associated with health care utilization in related settings (Mehta, Carter, Vinoya, Kangovi, & Srinivas, 2017; Shim, Stark, Ross, & Miller, 2019).

Available demographic factors included maternal age (years), educational attainment (categorized as < 12th grade, high school completion or GED, and > 12th grade), annual household income (collapsed to < $20,000, $20,000 – $40,000, > $40,000 or unknown), and marital status (collapsed to married or cohabitating versus other). These items were collected during study enrollment using standard items from national surveys. Employment was assessed at the most recent time point available (i.e. the time point in the 6 – 15 month window). Women were asked about live births prior to the most recent pregnancy, which we dichotomized as zero versus any.

We also considered several psychosocial factors as possible predisposing factors. Depression was assessed at enrollment using self-report of diagnosis of depression or anxiety in the pre-pregnancy or postpartum period using items from PRAMS (Shulman, D’Angelo, Harrison, Smith, & Warner, 2018). Depression may be underdiagnosed when assessing any one time point (Toohey, 2012). Therefore, we collapsed these two items into a single dichotomous variable, representing a diagnosis of depression in either the prenatal or the postpartum period.

Stress and social support were assessed at each time point. For participants where data from more than one time point was included we used the most recent time point for these items. Stress was assessed with the perceived stress scale (Karam et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2018). This scale ranges 0 – 20, with higher scores representing greater stress. When the scale was validated in a sample of pregnant women with symptoms of depression in Canada the mean score was 2.9 (Karam et al., 2012). Social support was assessed using the ENRICHD scale, which ranges from 6 – 31, with higher scores representing more support. ENRICHD has previously been applied to high risk cardiovascular populations (Hays, Sherbourne, & Mazel, 1995; Vaglio et al., 2004). Though not previously used in the postpartum population, it performed well in instrument testing for this study.

Enabling factors

We identified enabling factors related to health care access. Two items were taken from the National Health Interview Survey (Parsons et al., 2014). These included assessing for a personal relationship with a doctor or nurse (“A personal doctor or nurse is a health professional who knows you well and is familiar with your health history… Do you have one or more persons you think of as your personal doctor or nurse?), a usual place of care (“Is there ONE place that you USUALLY go to when you are sick or need advice about your health?”). Both of these items yielded dichotomous variables. Insurance type was assessed using PRAMS items (“currently do you have health insurance?” and “what type of insurance do you have?”). These questions were collapsed into three categories: no insurance, Medicaid insurance, or other. Enabling factors were assessed at all time points. For analysis we used data from the time point that fell in the 6 – 15 month window.

Analysis

Factors related to Andersen’s Model of Healthcare Utilization were examined. Figure 1 illustrates how available study data was classified according to constructs from this model (Andersen, 1995).

Figure 1:

Analytic factors in the context of Andersen’s Model of Health Service Use.

Note: The grey box represents the primary outcome in our analysis.

Factors were compared between women with and without health risks (hypertension, diabetes, preterm birth) using Fisher’s exact tests and Student t-tests for categorial and continuous variables, respectively.

Because interconception care utilization was a relatively common outcome in this population (>20%), we used multivariable log-linear Poisson regression with robust standard errors (i.e. relative risk regression) to evaluate the association of a interconception care with risk category and the previously described factors. In cases where a dichotomous outcome is common, this approach may minimize errors in calculating relative risks (Zou, 2004). In addition to the factors described above, regression also adjusted for time since most recent birth (months), study group (intervention versus control), and clustering by study site.

Our model building process initially began with the inclusion of each group of factors in succession (need, demographics, psychosocial, enabling, and other) to determine the effect of each covariate group independently and in combination with other factors. As this model building procedure resulted in similar interpretation as the fully adjusted model, which included all covariates, we presented the results for the model that included all previously described covariates. Results of regression models are presented as relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Sensitivity analyses were performed to determine whether dichotomization of self-rated health, perceived stress, and social support scales impacted interpretation of the regression model. We also examined whether use of the PHQ-2, a two question, validated measure of depressive symptoms (Arroll et al., 2010), led to different results than using report of a depression diagnosis. Finally, to assess whether allowing the timing of outcome data collection to vary from 6 – 15 months postpartum influenced our findings, we conducted an analysis limited to health care utilization reported in a narrower window of 6 – 10 months postpartum. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all comparisons. Analysis was conducted using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp, 2017).

RESULTS

Among the 376 women included in our sample, the mean maternal age was 27 (SD 6) years (Table 1). Most women reported non-Hispanic Black race and ethnicity (84%). Fewer than half (43%) had completed education beyond high school, and half reported household income < $20,000 (50%), married or living with a partner (55%) and current employment (54%). Data was collected for a mean of 272 days from birth (SD 57). In describing health care since their last pregnancy, 277 (74%) reported a postpartum visit around six-weeks postpartum, 304 (81%) reported a subsequent “checkup,” and 226 (60%) reported completing both visit types.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the cohort

| Overall N=376 |

No risk N=212 |

Any risk* N=164 |

p-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time from last birth (days) | 272 (57) | 274 (57) | 271 (56) | 0.65 |

| Received intervention | 174 (46%) | 113 (53%) | 89 (54%) | 0.91 |

| Completed postpartum visit & “checkup” | 226 (60%) | 123 (58%) | 103 (63%) | 0.52 |

| Need | ||||

| Self-rated health | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes or hypertension | 99 (26%) | 0 | 99 (60%) | <0.001 |

| Preterm birth or low birth weight | 110 (29%) | 0 | 110 (67%) | <0.001 |

| Predisposing factors: Demographics | ||||

| Maternal age (years) | 27 (6) | 26 (5) | 28 (7) | <0.001 |

| Race / Ethnicity | 0.20 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 317 (84%) | 175 (83%) | 142 (87%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 23 (6%) | 11 (5%) | 12 (7%) | |

| Hispanic | 17 (5%) | 13 (6%) | 4 (2%) | |

| Other | 19 (5%) | 13 (6%) | 6 (4%) | |

| Educational attainment | 0.06 | |||

| < 12th grade | 87 (23%) | 40 (19%) | 47 (29%) | |

| 12th grade / GED | 129 (34%) | 80 (38%) | 49 (30%) | |

| > 12th grade | 160 (43%) | 92 (43%) | 68 (41%) | |

| Married or cohabitating | 206 (55%) | 117 (55%) | 89 (54%) | 0.92 |

| Employment*** | 206 (54%) | 123 (58%) | 80 (49%) | 0.08 |

| Yearly household income | 0.12 | |||

| <$20,000 | 190 (50%) | 105 (50%) | 85 (52%) | |

| 20,000 – 40,000 | 90 (24%) | 45 (21%) | 45 (27%) | |

| >40,000 | 59 (16%) | 41 (19%) | 18 (11%) | |

| Unknown | 37(10%) | 21 (10%) | 16 (10%) | |

| Prior live birth | 207 (55%) | 98 (46%) | 109 (66%) | <0.001 |

| Predisposing factors: Psychosocial | ||||

| Depression | 72 (19%) | 32 (15%) | 40 (24%) | 0.03 |

| Perceived Stress*** | 4.5 (2.9) | 4.4 (2.9) | 4.6 (2.8) | 0.49 |

| Social support*** | 26 (5) | 26 (5) | 26 (5) | 0.50 |

| Enabling factors*** | ||||

| Usual place of care | 354 (94%) | 204 (96%) | 150 (91%) | 0.07 |

| Personal doctor or nurse | 261 (69%) | 141 (67%) | 120 (73%) | 0.10 |

| Current insurance | 0.48 | |||

| None | 23 (6%) | 24 (6%) | 9 (5%) | |

| Medicaid | 272 (72%) | 148 (70%) | 124 (76%) | |

| Other | 81 (22%) | 50 (24%) | 31 (19%) |

Includes women reporting hypertension, diabetes mellitus, preterm birth, or low birth weight.

P-values based on Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables or Student’s t-tests for continuous variables.

These variables were created using data at the 6 mon – 15 month study time. All other variables are from data collected at enrollment.

Need for care

Any health risk (hypertension, diabetes, or preterm birth or low birth weight in any prior pregnancy) was reported by 164 women (44%); 99 (26% of total sample) reported hypertension or diabetes and 110 (29% of total sample) reported a history of preterm birth or low birth weight. There were 45 women (12% of total sample) who had both hypertension or diabetes and a history of preterm birth or low birth weight. Self-rated health differed between women with a health risk and those without (2.3 versus 2.7, p-value < 0.001).

Predisposing factors

A history of depression was reported by 19% of women. Mean perceived stress score was 4.5 (SD 2.9). Mean social support was 26 (SD 5). History of depression was the only predisposing factor that differed between women with a health risk and those without (15% for no risk women versus 24% in women with self-reported risk; p-value 0.03).

Enabling factors

Almost all women (94%) reported a usual place of care and most (69%) reported having a personal doctor or nurse. Most women had Medicaid insurance (70%) or other forms of insurance (22%) but some reported no insurance (6%). None of these factors were associated with health risk.

Factors associated with visit completion

In multivariable Poisson regression (Table 2) we found that two enabling factors were associated with interconception visit completion. These included having a personal doctor or nurse (RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.11 – 1.70) and non-Medicaid insurance (RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.09 – 2.56). A long duration of time since birth (months) was also associated with higher visit completion (RR 1.10, 95% CI 1.05 – 1.15).

Table 2:

Association between health care utilization in the interconception period and key factors

| Unadjusted RR (95% Cl) | Multivariable RR (95% Cl) | |

|---|---|---|

| Need | ||

| Hypertension and/or diabetes | 1.15 (0.97 – 1.34) | 1.12 (0.93 – 1.34) |

| Preterm birth and/or LBW | 1.04 (0.87 – 1.24) | 0.98 (0.82 – 1.18) |

| Self-reported overall health | 1.00 (0.93 – 1.09) | 0.98 (0.90 – 1.06) |

| Predisposing factors: Demographics | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98 – 1.01) |

| Race / Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | -- | -- |

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.53 (0.30 – 0.94) | 0.60 (0.35 – 1.03) |

| Hispanic | 0.71 (0.42 – 1.20) | 0.81 (0.50 – 1.33) |

| Other | 0.93 (0.62 – 1.37) | 0.83 (0.56 – 1.24) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| < 12th grade | -- | -- |

| 12th grade/GED | 1.03 (0.81 – 1.29) | 1.05 (0.82 – 1.35) |

| > 12th grade | 1.07 (0.86 – 1.33) | 1.18 (0.92 – 1.50) |

| Married or cohabitating | 0.90 (0.76, 1.06) | 0.88 (0.75 – 1.05) |

| Employment* | 1.20 (1.01 – 1.43) | 1.21 (0.99 – 1.47) |

| Household income / yr | ||

| < $20,000 | -- | -- |

| $20,000 – $40,000 | 1.01 (0.73 – 1.71) | 0.95 (0.76 – 1.18) |

| > $40,000 | 0.91 (0.70, 1.17) | 0.90 (0.67 – 1.21) |

| Unknown | 0.97 (0.73, 1.30) | 1.10 (0.83 – 1.45) |

| Prior live birth | 1.02 (0.87, 1.21) | 1.07 (0.88 – 1.29) |

| Predisposing factors: Psychosocial | ||

| Depressive symptoms | 1.00 (0.81 – 1.24) | 1.09 (0.85 – 1.40) |

| Perceived Stress* | 0.99 (0.96 – 1.02) | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.05) |

| Social support* | 1.02 (0.99 – 1.04) | 1.02 (1.00 – 1.04) |

| Enabling factors* | ||

| Usual place of care | 1.01 (0.71 – 1.45) | 0.74 (0.52 – 1.05) |

| Personal doctor or nurse | 1.32 (1.07 – 1.63) | 1.38 (1.11 – 1.70) |

| Current insurance | ||

| None | -- | -- |

| Medicaid | 1.23 (0.79 – 1.91) | 1.14 (0.78 – 1.66) |

| Other | 1.36 (0.86 – 2.15) | 1.64 (1.09 – 2.56) |

| Other | ||

| Time from last birth (mon) | 1.09 (1.05 – 1.14) | 1.10 (1.05 – 1.15) |

Italics p < 0.10; italics bolded p < 0.05

Note: Multivariable model also adjusts for study site and intervention arm.

These variables were created using data at the 6 mon – 15 month study time. All other variables are from data collected at enrollment.

Sensitivity analysis

Interpretation of results did not materially change with the inclusion of dichotomous scales for self-rated health, perceived stress, and social support, when PHQ-2 was included as a measure of current depressive symptoms, or when we limited our sample to data collected by 10 months postpartum.

DISCUSSION

We found that enabling factors were associated with preventive health care utilization for women in this study. Specifically, women who could identify a personal doctor or nurse and those with non-Medicaid insurance were more likely to attend both a postpartum visit and a second check-up. These findings were robust across a number of sensitivity analyses examining definitions of variables related to depression, stress, and social support and timing of outcome assessment.

However, unexpectedly, women with self-reported health risks or pregnancy complications were not more likely to complete recommended care. These women did have poorer self-rated overall health. Self-rated health has been associated with increased health care utilization, diagnosed chronic conditions, and mortality for both men and women (Schnittker & Bacak, 2014; Zajacova, Huzurbazar, & Todd, 2017). However, in this study, this factor was not predictive of increased care. Interestingly, when we explored whether factors in our model demonstrated similar relationships when predicting only a postpartum visit, we found that hypertension diagnosis was associated with slightly increased postpartum follow-up. The postpartum visit is universally recommended, whereas subsequent health visits are specifically recommended for those with chronic conditions or complications of pregnancy. Therefore, we expected to see the reverse – namely that hypertension would not predict health care that is universally recommended but would predict subsequent health care recommended specifically for those with complications of pregnancy

In our analysis, identifying a personal doctor or nurse was more important than being able to identify a usual place of care. Having a personal doctor or nurse has previously been associated with increased receipt of care and improved quality of care (Atlas, Grant, Ferris, Chang, & Barry, 2009; Sox, Swartz, Burstin, & Brennan, 1998). Our findings, as well as these previous studies, speak to the importance of physician (or nurse) – patient relationships in ensuring care receipt. This relationship, with components of both the personal and the professional, is not always at the center of efforts to improve women’s health care.

The importance of modifiable enabling factors in our findings is encouraging, because these factors could be the basis of future efforts to improve receipt of preventive care among interconception women. Our findings suggest that connecting women to health care clinicians who known them and are familiar with their history, and insurance-related issues warrant ongoing attention in potential interventions to address health risks in low-income, urban populations. Our findings regarding Medicaid insurance may reflect factors other than quality of insurance coverage including difficulty finding clinicians who accept Medicaid insurance or gaps in coverage (Rhodes et al., 2014).

Prior work describing interconception care has varied in approach, including descriptions of both completion of care and content of care. We found relatively high rates of interconception preventive care utilization compared to prior work based on either self-report or administrative data (Bennett et al., 2014; Oza-Frank et al., 2014). This may be because data collection for this analysis took place in the context of intervention, where both treatment and control participants received encouragement from their child’s clinician to complete recommended care for themselves.

Strengths of this study include a rich dataset that allowed us to examine factors from multiple domains that are theoretically associated with health care utilization in Andersen’s model. All survey items in this study were taken from widely used, validated sources, and were field tested before final use. In addition, our study addressed a population that was largely Black race, with low household income and low educational attainment. In the US, Black women are at high risk for poor birth outcomes and poor cardiovascular outcomes compared to women of other races (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Thus understanding dynamics of health care utilization in this population may be particularly important to improving women’s health (Lu et al., 2010). We are unaware of any other reports addressing this population that are able to examine so many factors relevant to this theoretical model of health care utilization.

This study has several limitations. First, there may have been misclassification in our risk categories. Though preterm birth and low birth weight were assessed over all prior births, hypertension and diabetes were only assessed in the period surrounding the most recent pregnancy. Similarly, misclassification of our outcome may have occurred because women reported on our outcome of healthcare utilization across a nine-month span. Though we adjusted for time from birth and conducted sensitivity analysis to address this concern, some women may have sought preventive health care following the period of inclusion in our study. Second, there was minimal variability in some variables, particularly race and having a usual place of care. While these factors remained important in adjusting findings in our theory-driven model, lack of variability means that we may have been underpowered to detect associations between these factors and our outcome. Third, data was collected through self-report and, though we used broadly accepted items that are relied on for national public health planning, we cannot confirm that reported factors matched true participant characteristics. Finally, our findings may not be generalizable to other populations, including rural populations, or those who speak neither English nor Spanish.

In conclusion, in a low-income, population in the Baltimore area that was predominantly Black race, we found that approximately half of women accessed both a postpartum visit and another preventive care visit during their first 6 – 15 months postpartum. Receipt of this care was associated with having a personal doctor or nurse and non-Medicaid insurance. Other factors that might theoretically be expected to predict care were not associated with receipt of care in our model. These included self-rated health, and predisposing factors such as socioeconomic status and mental health. Future efforts to improve receipt of interconception care should focus on enabling factors, particularly health insurance and the personal relationship between women and health care professionals.

SIGNIFICANCE.

What is already known on this subject:

Preventive care before or between pregnancies may improve birth outcomes and women’s long-term health. However, many women, including those with health risks, do not access preventive care between pregnancies.

What this study adds:

A longitudinal dataset from the Baltimore, Maryland area allowed this theory-based approach to assessing factors associated with interconception preventive care. We found that enabling factors, particularly having a usual doctor or nurse and certain insurance types, are associated with increased preventive care in this critical period in the life course.

Acknowledgements:

This research received funding from the Abell Foundation, The Aaron and Lillie Straus Foundation, and The Zanvyl and Isabelle Krieger Fund, and the DC-Baltimore Research Center on Child Health Disparities (P20 MD000198) from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors, and no official endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the Department of Health and Human Services is intended or should be inferred.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. (2010). ACOG Committee Opinion #326. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 106(6), 1469–1470. 10.1097/00006250-200512000-00056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 1–10. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7738325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, Gunn J, Kerse N, Fishman T, … Hatcher S (2010). Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Annals of Family Medicine, 8(4), 348–353. 10.1370/afm.1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas SJ, Grant RW, Ferris TG, Chang Y, & Barry MJ (2009). Patient-physician connectedness and quality of primary care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 150(5), 325–335. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19258560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitsch B, Gohl D, & von Lengerke T (2012). Re-revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. Psycho-Social Medicine, 9, Doc11. 10.3205/psm000089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett WL, Chang H-YY, Levine DM, Wang L, Neale D, Werner EF, & Clark JM (2014). Utilization of primary and obstetric care after medically complicated pregnancies: An analysis of medical claims data. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(4), 636–645. 10.1007/s11606-013-2744-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield HE, & Wilt TJ (2011). Evidence Brief: Role of the Annual Comprehensive Physical Examination in the Asymptomatic Adult. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Evidence Briefs. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22206110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). CDC health disparities and inequalities report—United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62, 1–186.23302815 [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). CDC - PRAMS For Researchers - Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System - Reproductive Health. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/prams/prams-data/researchers.htm

- Chilukuri N, Cheng TL, Psoter KJ, Mistry KB, Connor KA, Levy DJ, & Upadhya KK (2018). Effectiveness of a Pediatric Primary Care Intervention to Increase Maternal Folate Use: Results from a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. The Journal of Pediatrics, 192, 247–252.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, & Mazel R (1995). User’s Manual for the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Core Measures of Health-Related Quality of Life. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR162.html

- Institute of Medicine. (2011). Clinical Preventive Services for Women: Closing the Gaps. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 10.17226/13181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karam F, Bérard A, Sheehy O, Huneau M-C, Briggs G, Chambers C, … OTIS Research Committee. (2012). Reliability and validity of the 4-item perceived stress scale among pregnant women: Results from the OTIS antidepressants study. Research in Nursing & Health, 35(4), 363–375. 10.1002/nur.21482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughon SK, Albert PS, Leishear K, & Mendola P (2014). The NICHD Consecutive Pregnancies Study: recurrent preterm delivery by subtype. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 210(2), 131.e1–8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BA, Schuver K, Dunsiger S, Samson L, Frayeh AL, Terrell CA, … Avery MD (2018). Rationale, design, and baseline data for the Healthy Mom II Trial: A randomized trial examining the efficacy of exercise and wellness interventions for the prevention of postpartum depression. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 70, 15–23. 10.1016/j.cct.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MC, Kotelchuck M, Culhane JF, Hobel CJ, Klerman LV, & Thorp JM (2006). Preconception care between pregnancies: the content of internatal care. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 10(5 Suppl), S107–22. 10.1007/s10995-006-0118-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MC, Kotelchuck M, Hogan V, Jones L, Wright K, & Halfon N (2010). Closing the Black-White gap in birth outcomes: a life-course approach. Ethnicity & Disease, 20(1 Suppl 2), S2–62–76. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20629248 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PK, Carter T, Vinoya C, Kangovi S, & Srinivas SK (2017). Understanding High Utilization of Unscheduled Care in Pregnant Women of Low Socioeconomic Status. Women’s Health Issues, 27(4), 441–448. 10.1016/j.whi.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, de Leiva A, Dunger DB, Hadden DR, … Zoupas C (2007). Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care, 30 Suppl 2(Supplement 2), S251–60. 10.2337/dc07-s225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mission JF, Catov J, Deihl TE, Feghali M, & Scifres C (2017). Early Pregnancy Diabetes Screening and Diagnosis. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 130(5), 1136–1142. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, … American Heart Association. (2011). Effectiveness-Based Guidelines for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women—2011 Update. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 57(12), 1404–1423. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oza-Frank R, Gilson E, Keim SA, Lynch CD, & Klebanoff MA (2014). Trends and Factors Associated with Self-Reported Receipt of Preconception Care: PRAMS, 2004–2010. Birth, 41(4), 367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons VL, Moriarity C, Jonas K, Moore TF, Davis KE, & Tompkins L (2014). Design and estimation for the national health interview survey, 2006–2015. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 2, Data Evaluation and Methods Research, (165), 1–53. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24775908 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Kenney GM, Friedman AB, Saloner B, Lawson CC, Chearo D, … Polsky D (2014). Primary Care Access for New Patients on the Eve of Health Care Reform. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(6), 861 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford RW, August PA, Cunningham G, Green LA, L. M (2000). Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 183(1), S1–S22. 10.1067/mob.2000.107928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J, & Bacak V (2014). The Increasing Predictive Validity of Self-Rated Health. PLoS ONE, 9(1), e84933 10.1371/journal.pone.0084933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro-Mendoza CK (2016). CDC grand rounds: public health strategies to prevent preterm birth. MMWR.Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JY, Stark EL, Ross CM, & Miller ES (2019). Multivariable Analysis of the Association between Antenatal Depressive Symptomatology and Postpartum Visit Attendance. American Journal of Perinatology, 36(10), 1009–1013. 10.1055/s-0038-1675770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman HB, D’Angelo DV, Harrison L, Smith RA, & Warner L (2018). The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): Overview of Design and Methodology. American Journal of Public Health, 108(10), 1305–1313. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sox CM, Swartz K, Burstin HR, & Brennan TA (1998). Insurance or a regular physician: which is the most powerful predictor of health care? American Journal of Public Health, 88(3), 364–370. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9518965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Toohey J (2012). Depression during pregnancy and postpartum. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 55(3), 788–797. 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318253b2b4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaglio J, Conard M, Poston WS, O’Keefe J, Haddock CK, House J, & Spertus JA (2004). Testing the performance of the ENRICHD Social Support Instrument in cardiac patients. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2(1), 24 10.1186/1477-7525-2-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Baer RJ, Berghella V, Chambers C, Chung P, Coker T, … Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL (2016). Recurrence of Preterm Birth and Early Term Birth. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 128(2), 364–372. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajacova A, Huzurbazar S, & Todd M (2017). Gender and the structure of self-rated health across the adult life span. Social Science & Medicine, 187, 58–66. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G (2004). A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]