Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To examine within-hospital racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity rates and determine whether they are associated with differences in types of medical insurance.

METHODS:

We conducted a population-based cross-sectional study using linked 2010-2014 New York City discharge and birth certificate datasets (N=591,455 deliveries) to examine within-hospital Black-White, Latina-White, and Medicaid-commercially insured differences in severe maternal morbidity. We used logistic regression to produce risk-adjusted rates of severe maternal morbidity for patients with commercial and Medicaid insurance and for Black, Latina, and White patients within each hospital. We compared these with-in hospital adjusted rates using paired t-tests and conditional logit models.

RESULTS:

Severe maternal morbidity was higher among Black and Latina than White women (4.2%, 2.9% vs.1.5%, p<.001) and among women insured by Medicaid than those commercially insured (2.8% vs. 2.0%, p<.001). Women insured by Medicaid versus those with commercial insurance had similar risk for severe maternal morbidity within the same hospital (p=.54). In contrast, Black versus White women had significantly higher risk for severe maternal morbidity within the same hospital (p<.001) as did Latina women (p<0.001). Conditional logit analyses confirmed these findings with Black and Latina versus White women having higher risk for severe maternal morbidity (adjusted odds ratio=1.52; 95% CI 1.46-1.62 and adjusted odds ratio=1.44; 95% CI 1.36-1.53, respectively) and women insured by Medicaid compared to those commercially insured having similar risk.

CONCLUSION:

Within hospitals in New York City, Black and Latina women are at higher risk of severe maternal morbidity than White women that is not associated with differences in types of insurance.

PRECIS

Within-hospital racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity rates exist in New York City hospitals but are not associated with differences in type of medical insurance.

Introduction

Research has documented racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity rates and that between-hospital differences -- i.e., Black and Latina mothers receiving care at hospitals with worse outcomes -- explain a sizable portion of these disparities.1-3 However, less attention has been paid to within-hospital disparities -- whether Black and Latina mothers have worse outcomes than White mothers who deliver in the same hospital.1,3

Medicaid covers nearly half of the deliveries in the United States and Black and Latina pregnant women are more likely to be insured by Medicaid than are White pregnant women. 1,3,4 In other areas of medicine research has documented that patients insured by Medicaid tend to receive lower quality of care than patients insured by commercial insurance even within the same hospital.5 There are reasons to suspect that insurance type may contribute to racial and ethnic severe maternal morbidity disparities within the same hospital. Pregnant women insured by Medicaid may be cared for by a different set of physicians. Reimbursement levels for delivery are lower for Medicaid versus commercially insured deliveries.6 Few studies have examined whether insurance status contributes to within-hospital racial disparities in severe maternal morbidity rates.

Our objective was to examine within-hospital racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity rates and to determine whether they are associated with differences in types of medical insurance.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional study using Vital Statistics birth records linked with New York State discharge abstract data - The Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) for all delivery hospitalizations in New York City from 2010 to 2014. Data linkage was conducted by the New York State Department of Health and Institutional Review Board approvals were obtained from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, the New York State Department of Health, and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Delivery hospitalizations were identified based on ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes and DRG delivery codes.7 Ninety eight percent of maternal discharges were linked with infant birth certificates. The final sample included 591,455 deliveries to live infants at 40 New York City hospitals.

New York City birth records include self-identified race and ethnicity data. We created a race/ethnicity variable by combining the race and information on Latina ethnicity into the following categories: non-Latina Black, Latina, non-Latina White, Asian and other race. We refer to non-Latina Black as Black and non-Latina White as White in this manuscript. We focus our analyses on Black, Latina, and White mothers. We ascertained patient insurance status from SPARCS and categorized it as “commercial”, “Medicaid”, “self-pay”, and “other”. Medicaid included all public insurance plans.

We used a published algorithm to identify severe maternal morbidity, using diagnoses for life-threatening conditions and procedure codes for life-saving procedures defined by investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).8,9

We compared sociodemographic characteristics and clinical conditions of Black, Latina and White deliveries as well as deliveries covered by Medicaid versus those covered by commercial insurance using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables.

We estimated risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity using logistic regression controlling for maternal sociodemographic (e.g., self-identified race and ethnicity, age, education, parity, country of birth), clinical and obstetric factors (e.g., multiple pregnancy, history of previous cesarean delivery, body mass index, prenatal care). Similar to previous research we also adjusted for patient risk factors that could lead to maternal morbidity and were likely present on admission to the hospital (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, premature rupture of membranes, disorders of placentation).10-13 Model fit was assessed by using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve statistics (c=0.780).

The risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity rates for each hospital were estimated by calculating the number of observed events over expected events for a hospital and multiplying it by the mean severe maternal morbidity rate for New York City.14 We ranked the hospitals from lowest to highest risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity using this approach.14

Next, using the same approach we estimated the risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity rates for Black versus White and Latina versus White deliveries and for deliveries insured by Medicaid versus those insured by commercial insurance and compared within-hospital adjusted rates using paired t tests. We calculated the difference in risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity rates for Black vs. White, Latina vs. White and Medicaid vs. commercially insured deliveries for each hospital and then performed a t-test to assess whether those differences were significantly different from zero. Because we analyzed differences in rates for the same hospital, the paired t-test analysis controlled for all unobserved within hospital characteristics that might confound the relationship between insurance and maternal morbidity.5 Women for whom insurance status was categorized as self-pay or other (<2%) were excluded from these analyses. We conducted a confirmatory analysis using conditional logit. A conditional logit model—also known as fixed-effects logit model--is an extension of logistic regression that produces adjusted odds ratios that are conditional on the group to which an observation belongs, the hospital, in our case. The odds ratio on race from a standard logistic regression model measures disparities due to both within hospital (i.e., Black mothers have worse outcomes than White mothers within each hospital) and between hospitals (i.e., Black mothers deliver at hospitals that treat all mothers poorly) factors.15 By conditioning on the hospital, conditional logit models eliminate any between-hospital influences on the odds ratios, leaving only within hospital estimates of racial differences. We tested for differences by insurance status on the within-hospital association of race and severe maternal morbidity by including interactions between race and insurance and ethnicity and insurance in these conditional models. We conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, we reran the conditional logit models on severe maternal morbidity without blood transfusion, as blood transfusions are a major component of the severe maternal morbidity measure. Second, we restricted the sample to hospitals between 20–80% of Medicaid deliveries because the distribution of Medicaid-insured patients across hospitals is skewed in New York City. Within-hospital differences in severe maternal morbidity by insurance are difficult to detect when only a small percentage of births are covered by either Medicaid or commercial insurance and therefore this restriction would increase the likelihood of finding a statistically significant within-hospital disparity in severe maternal morbidity by insurance, if one exists.

Given prior research demonstrating the association of Medicaid with health outcomes at the hospital-level,16 we also explored whether hospital performance for severe maternal morbidity is lower for hospitals with a higher percentage of patients insured by Medicaid. We calculated a Pearson correlation coefficient to assess the correlation between hospital-level rates of risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity and percent Medicaid deliveries. We also divided hospitals into quartiles based on percent Medicaid and examined hospital risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity rates using chi-square tests.

All statistical analysis was performed using the SAS system software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

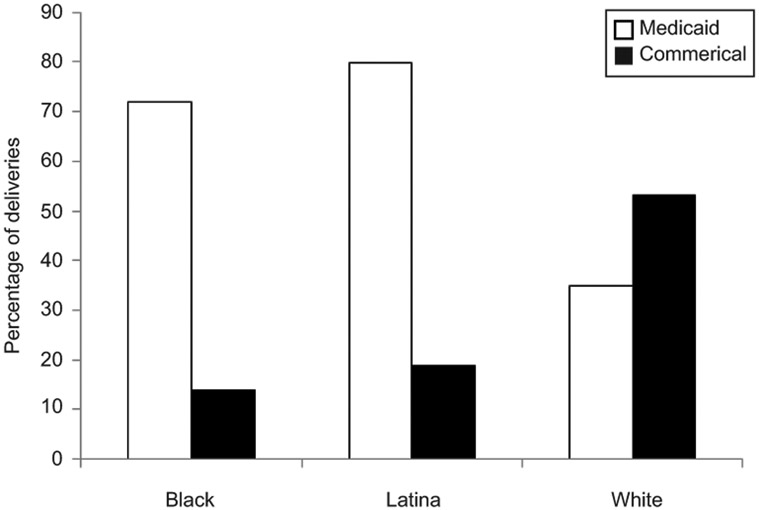

Black mothers accounted for 21%, Latina mothers for 30%, and White mothers for 31% of the 591,455 deliveries in New York City in 2010–2014. Medicaid insured 60.7% (n=358,897) of deliveries during this period (Table 1). Black and Latina versus White mothers were more likely to be insured by Medicaid (72%, 80% vs. 35% respectively, p<.001). (Figure 1). Severe maternal morbidity occurred in 15,158 deliveries (2.6%) and was higher among Black (4.2%) and Latina (2.9%) versus White (1.5%) mothers (p<.001) and among women insured by Medicaid (2.8%) versus women insured by commercial insurance (2.0%; p<.001). Similar racial and ethnic differences in severe maternal morbidity with and without blood transfusion existed when stratified by insurance (Table 2).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of deliveries in New York City between 2010-2014 by race/ethnicity and medical insurance.

| Black | Latina | White | Commercial | Medicaid | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n= 122067 | N=177768 | n= 185095 | P- value* |

N=221479 | N=358897 | P- value** |

||||||

| % | N | % | N | N | % | N | % | N | ||||

| Maternal Age | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| <20 | 7.1 | 8704 | 9.1 | 16206 | 1.2 | 2304 | 0.9 | 1969 | 7.3 | 26118 | ||

| 20-29 | 47.9 | 58406 | 51.8 | 92117 | 34.4 | 63748 | 24.1 | 53314 | 55.9 | 200710 | ||

| 30-34 | 24.6 | 30003 | 23.0 | 40964 | 34.6 | 64034 | 39.9 | 88278 | 21.9 | 78745 | ||

| 35-39 | 15.3 | 18637 | 12.6 | 22390 | 22.7 | 42021 | 27 | 59875 | 11.5 | 41346 | ||

| 40-44 | 4.73 | 5774 | 3.2 | 5741 | 6.4 | 11832 | 7.44 | 16477 | 3.11 | 11174 | ||

| 45+ | 0.4 | 543 | 0.2 | 350 | 0.6 | 1156 | 0.71 | 1577 | 0.2 | 804 | ||

| Ancestry | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| US Born | 57.7 | 70468 | 45.6 | 81028 | 72.5 | 134205 | 67.3 | 149083 | 43.4 | 155905 | ||

| Foreign Born | 42.3 | 51599 | 54.4 | 96740 | 27.5 | 50890 | 31.6 | 69959 | 55.4 | 198647 | ||

| Insurance | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Medicaid | 72.2 | 88071 | 79.7 | 141719 | 35.0 | 64762 | ||||||

| Private | 25.1 | 30687 | 18.9 | 33557 | 63.6 | 117750 | ||||||

| Other | 0.8 | 990 | 0.5 | 823 | 0.7 | 1249 | ||||||

| Uninsured | 1.9 | 2319 | 0.9 | 1669 | 0.7 | 1334 | ||||||

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 3.5 | 4287 | 3.1 | 5462 | 3.5 | 11001 | 5.4 | 11937 | 5.5 | 19685 | ||

| Normal weight (18.5-24.9) | 37.7 | 45967 | 44.8 | 79671 | 37.7 | 45967 | 61.8 | 136825 | 47.8 | 171485 | ||

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 29.2 | 35609 | 29.6 | 52642 | 18.4 | 33956 | 19.5 | 43125 | 25.7 | 92393 | ||

| Obese (30.0-39.9) | 23.9 | 29133 | 18.8 | 33387 | 8.3 | 15359 | 10.5 | 23166 | 16.2 | 58207 | ||

| Morbid Obesity (≥40) | 4.7 | 5752 | 2.6 | 4626 | 1.0 | 1891 | 1.5 | 3234 | 2.5 | 9073 | ||

| Missing BMI | 1.1 | 1319 | 1.1 | 1980 | 0.4 | 796 | 1.4 | 3194 | 2.2 | 8054 | ||

| Smoked during pregnancy | 3.7 | 4456 | 2.5 | 4511 | 2.3 | 4286 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 3909 | 2.8 | 10047 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | 1.2 | 1463 | 0.9 | 1505 | 0.9 | 1635 | <0.001 | 0.9 | 2037 | 0.9 | 3348 | <0.001 |

| Education | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Less than HS | 20.3 | 24727 | 36.7 | 65221 | 7.9 | 14553 | 2.6 | 5658 | 33.1 | 118866 | ||

| HS | 26.9 | 32831 | 24.1 | 42759 | 18.8 | 34881 | 8.3 | 18331 | 30.3 | 108581 | ||

| Greater than HS | 52.3 | 63822 | 39.0 | 69356 | 73.1 | 135216 | 87.9 | 194771 | 35 | 125524 | ||

| Missing or unknown | 0.6 | 687 | 0.2 | 432 | 0.2 | 445 | 1.1 | 2438 | 1.2 | 4345 | ||

| Prenatal visits | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| 0-5 | 11.9 | 14549 | 7.3 | 12993 | 3.4 | 6256 | 2.5 | 5464 | 8.8 | 31474 | ||

| 6-8 | 15.8 | 19310 | 12.7 | 22652 | 9.9 | 18231 | 9.4 | 20722 | 13.6 | 48891 | ||

| ≥9 | 70.3 | 85866 | 78.5 | 139568 | 86.1 | 159296 | 86.2 | 190927 | 75 | 269300 | ||

| Unknown | 1.9 | 2342 | 1.3 | 2555 | 0.7 | 1312 | 2 | 4367 | 2.6 | 9232 | ||

| Parity | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Nulliparous | 43.6 | 53257 | 41.1 | 73092 | 47.1 | 87272 | 53.1 | 117567 | 39.4 | 141411 | ||

| Multiparous | 56.2 | 68574 | 58.7 | 104411 | 52.7 | 97579 | 45.7 | 101162 | 59.3 | 212630 | ||

| Missing | 0.2 | 236 | 0.2 | 265 | 0.1 | 244 | 1.2 | 2751 | 1.4 | 4856 | ||

| Type of Pregnancy | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Singleton | 98.1 | 119730 | 98.7 | 175436 | 97.3 | 180146 | 97.1 | 215118 | 98.7 | 354137 | ||

| Multiple | 1.9 | 2337 | 1.3 | 2332 | 2.7 | 4949 | 2.9 | 6362 | 1.3 | 4760 | ||

| C-Section Delivery | 37.4 | 45600 | 32.7 | 58128 | 28.1 | 52036 | <0.001 | 36.4% | 80651 | 30.9% | 110977 | |

| Previous Cesarean | 17.0 | 20748 | 17.7 | 31431 | 13.8 | 25568 | <0.001 | 15.2 | 33595 | 16.4 | 59004 | |

| Primary Cesarean | 23.3 | 28397 | 18.0 | 32027 | 17.8 | 32936 | <0.001 | 23.0% | 51011 | 17.0% | 60833 | |

| Vaginal Delivery | 62.7 | 76467 | 67.3 | 119640 | 71.9 | 133059 | <0.001 | 63.6% | 140829 | 69.1% | 247920 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||||

| Cardiac Disease | 1.5 | 1795 | 0.3 | 541 | 0.6 | 1132 | <0.001 | 0.6% | 1431 | 0.3% | 1011 | <0.001 |

| Renal Disease | 0.4 | 541 | 0.1 | 137 | 0.04 | 81 | <0.001 | 0.1% | 126 | 0.1% | 255 | 0.04 |

| Musculoskeletal Disease | 0.3 | 401 | 0.3 | 567 | 0.3 | 564 | 0.50 | 0.4% | 955 | 0.2% | 828 | <0.001 |

| Digestive Disorder | 0.02 | 30 | 0.03 | 50 | 0.2 | 455 | <0.001 | 0.2% | 370 | 0.0% | 172 | <0.001 |

| Blood Disease | 18.8 | 22935 | 15.6 | 27744 | 10.2 | 18885 | <0.001 | 11.5% | 25538 | 14.9% | 53490 | <0.001 |

| Mental Disorders | 4.0 | 4940 | 3.5 | 6183 | 3.1 | 5714 | <0.001 | 2.6% | 5728 | 3.3% | 11961 | <0.001 |

| CNS disease | 1.2 | 1501 | 1.2 | 2222 | 1.2 | 2250 | 0.64 | 1.4% | 3017 | 0.9% | 3343 | <0.001 |

| Rheumatic Heart Disease | 0.1 | 103 | 0.1 | 96 | 0.03 | 60 | <0.001 | 0.0% | 86 | 0.1% | 210 | 0.001 |

| Disorder Placentation | 2.2 | 2641 | 1.5 | 2731 | 1.5 | 2703 | <0.001 | 1.8% | 3897 | 1.7% | 6020 | 0.02 |

| Chronic Hypertension | 3.0 | 3650 | 1.2 | 2207 | 0.7 | 1339 | <0.001 | 1.3% | 2868 | 1.4% | 5126 | <0.001 |

| Pregnancy Hypertension | 8.7 | 10599 | 6.0 | 10605 | 3.2 | 5836 | <0.001 | 4.5% | 9955 | 5.6% | 19978 | <0.001 |

| Lupus | 0.2 | 257 | 0.2 | 344 | 0.1 | 213 | <0.001 | 0.2% | 446 | 0.1% | 493 | <0.001 |

| Collagen Vascular Disorder | 0.04 | 47 | 0.03 | 50 | 0.1 | 124 | <0.001 | 0.1% | 200 | 0.0% | 79 | <0.001 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 0.1 | 113 | 0.1 | 189 | 0.1 | 223 | 0.07 | 0.1% | 326 | 0.1% | 276 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.2 | 1431 | 0.9 | 1563 | 0.4 | 714 | <0.001 | 0.6% | 1231 | 0.9% | 3148 | <0.001 |

| Gestational diabetes | 1.3 | 1585 | 1.0 | 1709 | 0.4 | 793 | <0.001 | 0.6% | 1407 | 1.0% | 3476 | <0.001 |

| Asthma/Chronic bronchitis | 4.3 | 7703 | 5.4 | 9562 | 4.4 | 8061 | <0.001 | 4.80% | 10639 | 5.1% | 18137 | <0.001 |

Asian, and other race populations not shown; N= 106,525 (18.0%)

Other insurances and uninsured not shown; N=11,077 (1.9%)

Figure 1.

Maternal insurance status of black, Latina, and white deliveries in New York City hospitals, 2010–2014.

Table 2.

Insurance, Race, Ethnicity, and Severe Maternal Morbidity with and without blood transfusions.

| Deliveries | Severe Maternal Morbidity |

Severe Maternal Morbidity without Blood Transfusion Cases |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % (N) | % (N) | |

| Commercially Insured | 221479 | 2.01 (4462) | 0.80 (1765) |

| Medicaid | 358897 | 2.88 (10339) | 0.86 (3072) |

| Black | 122067 | 4.2 (5125) | 1.35 (1646) |

| Latina | 177768 | 2.85 (5072) | 0.84 (1499) |

| White | 185095 | 1.46 (2708) | 0.55 (1020) |

| Black Commercially Insured | 30687 | 3.73 (1146) | 1.52 (466) |

| Latina Commercially Insured | 33557 | 2.24 (751) | 0.83 (279) |

| White Commercially Insured | 117750 | 1.54 (1810) | 0.61 (724) |

| Black Medicaid | 88071 | 4.35 (3830) | 1.29 (1133) |

| Latina Medicaid | 141719 | 2.99 (4237) | 0.84 (1194) |

| White Medicaid | 64762 | 1.31 (850) | 0.43 (281) |

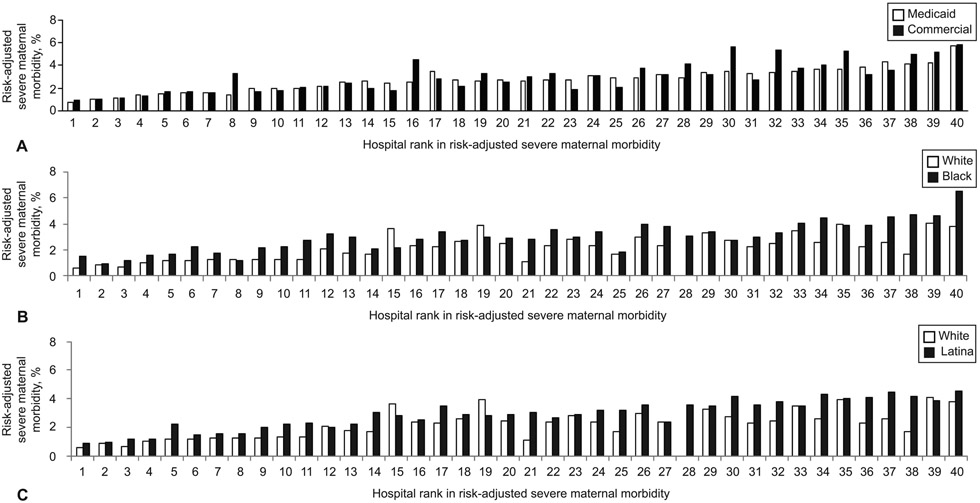

The majority of the 40 hospitals were private, had Level 3/4 nurseries, and were teaching hospitals. The median percent of Medicaid deliveries for New York City hospitals was 81.1% (IQR 48.7%−92.4%). Figure 2 shows within-hospital risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity rates for Medicaid versus commercially insured, for Black versus White, and for Latina versus White deliveries across hospitals ranked from lowest to highest rates of risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity.

Figure 2.

Within hospital comparison of risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity for Medicaid versus commercially-insured deliveries (P=.54) (A); black versus white deliveries (P<.001) (B); and Latina versus white deliveries (P<.01) (C). P values are calculated using paired t-test.

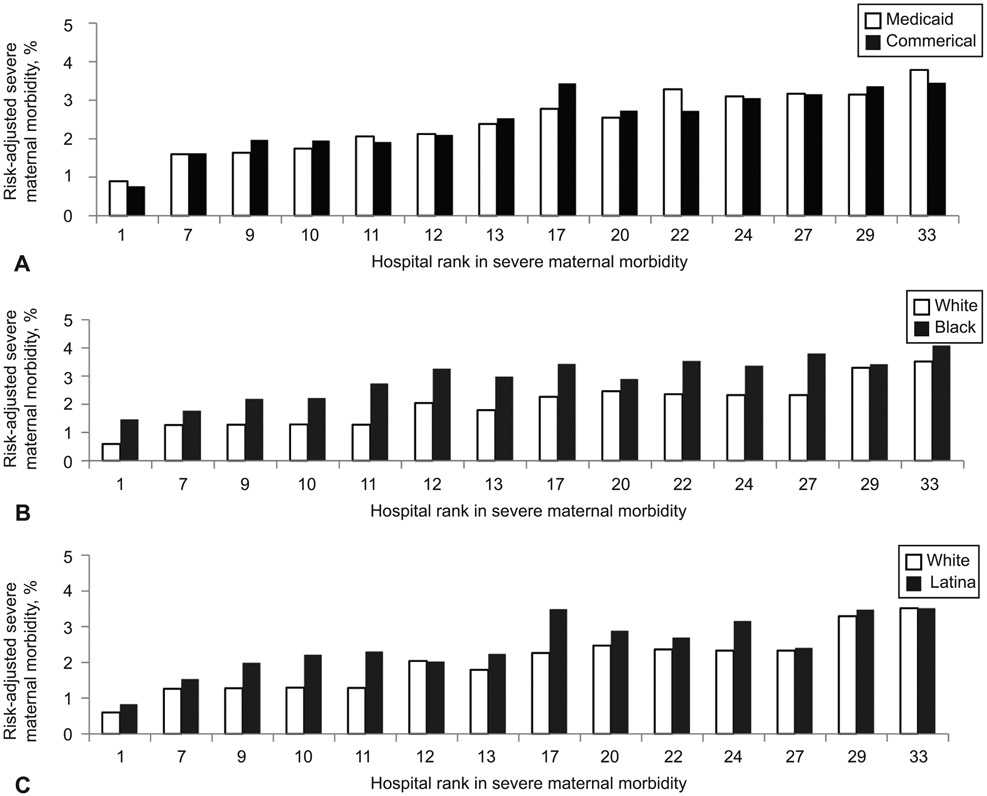

Paired t-tests demonstrated that women insured by Medicaid and those commercially insured had similar risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity rates within the same hospital (p=.54). In contrast, Black women had statistically significant higher risk for severe maternal morbidity within-hospital (p<.001) as did Latina women (p<.001). Conditional logit analyses confirmed these findings with Black and Latina versus White women having higher within hospital risks for severe maternal morbidity (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.52; 95% CI 1.46–1.62 and AOR=1.44; 95% CI 1.36–1.53, respectively) and women insured by Medicaid versus those commercially insured having similar risk (AOR=1.05; 95% CI 0.99–1.11). Sensitivity analyses excluding blood transfusions from the severe maternal morbidity outcome corroborated these findings with Black and Latina versus White women having higher risk for severe maternal morbidity (AOR=1.51; 95% CI 1.38–1.67 and AOR=1.27; 95% CI 1.15–1.40, respectively). Further, sensitivity analysis of hospitals with 20–80% of deliveries insured by Medicaid also confirmed these analyses. (Figure 3). The interactions between race and insurance and ethnicity and insurance were insignificant in the conditional logit model suggesting that within-hospital association between race and severe maternal morbidity or ethnicity and severe maternal morbidity did not vary by insurance.

Figure 3:

Within hospital comparison of risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity for hospitals with percentage of Medicaid deliveries between 20% and 80%: Medicaid versus commercially insured deliveries (P=.65) (A); black versus white deliveries (P<.001) (B); and Latina versus white deliveries (P<.001) (C). P values are calculated using paired t-test.

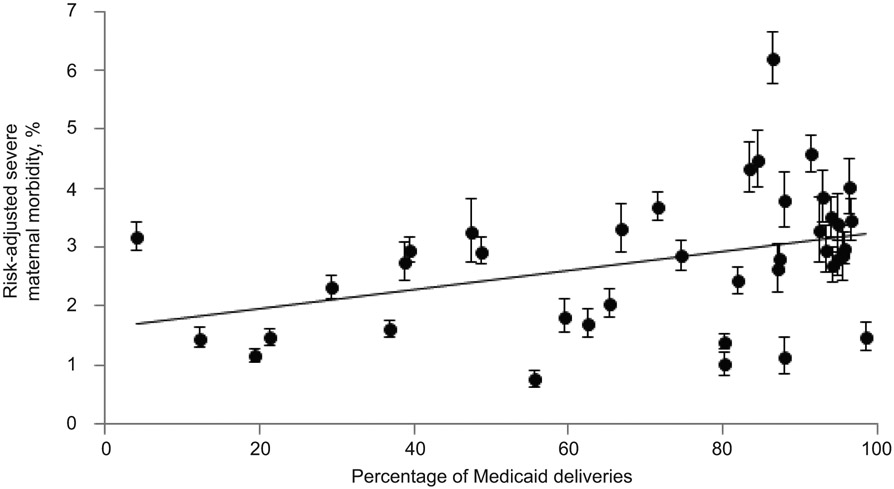

In the analysis testing the association between the percent of deliveries insured by Medicaid at the hospital level and risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity, we found a positive association (rho=0.13, p=0.01) (See Figure 4). However, hospitals with low rates of severe maternal morbidity were found among both low and high percent Medicaid hospitals. The risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity rate for hospitals in the highest quartile of Medicaid deliveries was 3.1% compared with 2.3% for the hospitals in the lowest quartile of Medicaid deliveries (p=0.03).

Figure 4.

Association of risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity with percentage of Medicaid deliveries in New York City hospitals.

DISCUSSION

Our data demonstrate that Black and Latina women are more likely than White women to experience a severe maternal morbidity within the same hospital after accounting for patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. These disparities were not explained by type of medical insurance. In fact, women insured by Medicaid and those with commercial insurance had similar risks for severe maternal morbidity within the same hospital.

Growing attention has focused on the potential contribution of Medicaid to racial and ethnic disparities in maternal health outcomes, even within the same hospital for a few reasons. First, pregnant women insured by Medicaid are often seen by resident physicians with attending coverage that may differ from attending physicians caring for commercially insured women. In other areas of medicine, researchers found that Medicaid patients were treated by lower-quality physicians.17,18 Second, Medicaid reimbursement for delivery hospitalization is far less than that for commercially insured and research suggests that physicians may alter their treatment practices based on the generosity of patients’ insurers.19 To our surprise, our data do not suggest that any differences in treatment patterns were reflected in worse outcomes for Medicaid-covered and commercially insured mothers within the same hospital. These results indicate that pathways other than insurance are responsible for the higher risks of severe maternal morbidity among Black and Latina versus White women that were observed in our study.

Disparities are a complex phenomenon and multiple pathways contribute to their occurrence.20 One pathway, documented by a growing body of research, is structural racism and bias in health care and in maternal health care specifically.21 More detailed research examining causes of variations in care for pregnant Black and Latina versus White women within the same hospitals such as patient-doctor communication, structural racism, bias, language issues, shared decision-making, and differential use of obstetrical quality tools is needed as these could be important levers to reduce disparities within hospitals. There is a large focus on implementation of implicit bias training in hospitals to address bias in patient care but more research is needed to assess its effect on patient outcomes.22 Additional research is also needed to better understand how community and social factors, as well as prenatal care factors, contribute to within-hospital racial and ethnic disparities. Richer data are needed to understand these pathways and multiple research designs should be considered, including mixed-methods, qualitative and interventional studies.23

Our findings that hospitals heavily reliant on Medicaid experienced higher severe maternal morbidity rates is consistent with previous health policy research documenting that payer mix and other hospital characteristics are associated with health outcomes.16,24,25 The median percent Medicaid deliveries in our sample was high and higher rates of severe maternal morbidity in Medicaid-reliant hospitals may be related to resource constraints. Our results raise the hypothesis that effects of reduced reimbursement for Medicaid may operate at the hospital but not at the individual level. Previous studies that examined hospitals that predominantly served disadvantaged patients had insufficient nursing resources to provide high quality care.26,27 Interestingly, in our analysis the association between hospital rates of severe maternal morbidity and percent Medicaid deliveries was not strictly uniform, in that high-Medicaid hospitals could be found in the lowest and highest clusters of risk for severe maternal morbidity (Figure 3). High performing Medicaid-reliant hospitals may have specific organizational practices, policies and procedures, or other characteristics that explain their strong performance and exploring this is an important area for future research.

Our analysis has some limitations. We used administrative data (ICD-9 procedure and diagnosis codes) that do not contain important clinical data on severity of illness. Although vital statistics and SPARCS have limitations with reliability of specific variables,28,29 we combined both sources as recommended to optimize validity.30 We used a published algorithm to identify severe maternal morbidity cases but did not conduct a medical chart review for case ascertainment. The CDC algorithm using ICD-9 codes for severe maternal morbidity has been reported to have good sensitivity but average positive predictive value.31 Our classification of Latina ethnicity combined Latinas of diverse ancestry, therefore not capturing the intersection of race and Latina ethnicity. Likewise, “Black” combines diverse groups such as Haitian immigrants and US-born Black women. We were unable to assess unmeasured community and social factors that may contribute to racial and ethnic disparities. In addition, we were unable to examine prenatal care factors and management of preexisting health conditions that may also contribute to disparities.

Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidities within the same hospital are disconcerting and demand immediate attention. Multiple factors may be driving these disparities. Optimizing the quality of care at all delivery hospitals including standardizing care, enhancing communication skills, implementing bias trainings, improving translation services, using disparities dashboards that stratify quality metrics by race and ethnicity, implementing quality improvement activities targeting gaps identified in care, and strengthening community partnerships are recommended steps that can address racial and ethnic disparities both within and between-hospitals.32,33 Differences in quality of care, whether within the same hospital or between hospitals, are potentially modifiable and actionable targets that we can address now.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01MD007651). The funders of this study had no role in design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Presented at Academy Health Annual Research Meeting June 2, 2019, Washington D.C.

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth A. Howell, Department of Population Health Science & Policy, Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science, Blavatnik Family Women’s Health Research Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

Natalia N. Egorova, Department of Population Health Science & Policy, Blavatnik Family Women’s Health Research Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

Teresa Janevic, Department of Population Health Science & Policy, Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science, Blavatnik Family Women’s Health Research Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

Michael Brodman, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science, Blavatnik Family Women’s Health Research Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

Amy Balbierz, Department of Population Health Science & Policy, Blavatnik Family Women’s Health Research Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

Jennifer Zeitlin, Department of Population Health Science & Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York; Inserm UMR 1153, Obstetrical, Perinatal and Pediatric Epidemiology Research Team (Epopé), Center for Epidemiology and Biostatistics Sorbonne Paris Cité, DHU Risks in pregnancy, Paris Descartes University, Paris, France.

Paul L. Hebert, University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, Washington..

REFERENCES

- 1.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:122 e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Janevic T, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Severe Maternal Morbidity Among Hispanic Women in New York City: Investigation of Health Disparities. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:285–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markus AR, Andres E, West KD, Garro N, Pellegrini C. Medicaid covered births, 2008 through 2010, in the context of the implementation of health reform. Womens Health Issues 2013;23:e273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spencer CS, Gaskin DJ, Roberts ET. The quality of care delivered to patients within the same hospital varies by insurance type. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1731–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heatley E, Middleton P, Hague W, Crowther C. The DIAMIND study: postpartum SMS reminders to women who have had gestational diabetes mellitus to test for type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial - study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuklina EV, Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, et al. An enhanced method for identifying obstetric deliveries: implications for estimating maternal morbidity. Matern Child Health J 2008;12:469–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1029–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States. 2019. (Accessed July 5 2019, at http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/MaternalInfantHealth/SevereMaternalMorbidity.html.)

- 10.Gray KE, Wallace ER, Nelson KR, Reed SD, Schiff MA. Population-based study of risk factors for severe maternal morbidity. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012;26:506–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srinivas SK, Fager C, Lorch SA. Evaluating risk-adjusted cesarean delivery rate as a measure of obstetric quality. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:1007–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grobman WA, Feinglass J, Murthy S. Are the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality obstetric trauma indicators valid measures of hospital safety? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:868–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, Balbierz A, Egorova N. Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. JAMA 2014;312:1531–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howell EA, Hebert P, Chatterjee S, Kleinman LC, Chassin MR. Black/white differences in very low birth weight neonatal mortality rates among New York City hospitals. Pediatrics 2008;121:e407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hebert PL, Howell EA, Wong ES, et al. Methods for Measuring Racial Differences in Hospitals Outcomes Attributable to Disparities in Use of High-Quality Hospital Care. Health Serv Res 2017;52:826–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhoads KF, Ackerson LK, Jha AK, Dudley RA. Quality of colon cancer outcomes in hospitals with a high percentage of Medicaid patients. J Am Coll Surg 2008;207:197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner L, Vishwasrao S. Physician quality and health care for the poor and uninsured. Inquiry 2010;47:62–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geissler KH, Lubin B, Marzilli Ericson KM. Access is Not Enough: Characteristics of Physicians Who Treat Medicaid Patients. Med Care 2016;54:350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein AJ, Ketcham JD, Rathore SS, Groeneveld PW. Variations in the use of an innovative technology by payer: the case of drug-eluting stents. Med Care 2012;50:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howell EA. Reducing Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2018;61:387–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Attanasio LB, Hardeman RR. Declined care and discrimination during the childbirth hospitalization. Soc Sci Med 2019;232:270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, Singh A, Johnson TJ. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc Sci Med 2018;199:219–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howell EA, Ahmed ZN, Sofaer S, Zeitlin J. Positive Deviance to Address Health Equity in Quality and Safety in Obstetrics. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2019;62:560–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franks P, Clancy CM, Gold MR. Health insurance and mortality. Evidence from a national cohort. JAMA 1993;270:737–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weygandt PL, Losonczy LI, Schneider EB, et al. Disparities in mortality after blunt injury: does insurance type matter? J Surg Res 2012;177:288–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks-Carthon JM, Kutney-Lee A, Sloane DM, Cimiotti JP, Aiken LH. Quality of care and patient satisfaction in hospitals with high concentrations of black patients. J Nurs Scholarsh 2011;43:301–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lake ET, Staiger D, Edwards EM, Smith JG, Rogowski JA. Nursing Care Disparities in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Health Serv Res 2018;53 Suppl 1:3007–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiGiuseppe DL, Aron DC, Ranbom L, Harper DL, Rosenthal GE. Reliability of birth certificate data: a multi-hospital comparison to medical records information. Matern Child Health J 2002;6:169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasmeen S, Romano PS, Schembri ME, Keyzer JM, Gilbert WM. Accuracy of obstetric diagnoses and procedures in hospital discharge data. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:992–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dietz P, Bombard J, Mulready-Ward C, et al. Validation of selected items on the 2003 U.S. standard certificate of live birth: New York City and Vermont. Public Health Rep 2015;130:60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Main EK, Abreo A, McNulty J, et al. Measuring severe maternal morbidity: validation of potential measures. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:643 e1–e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howell EA, Brown H, Brumley J, et al. Reduction of Peripartum Racial and Ethnic Disparities: A Conceptual Framework and Maternal Safety Consensus Bundle. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:770–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howell EA, Ahmed ZN. Eight steps for narrowing the maternal health disparity gap: Step-by-step plan to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in care. Contemp Ob Gyn 2019;64:30–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.