Addictive drugs usurp the brain's intrinsic mechanism for reward, leading to compulsive and destructive behaviors. In the ventral tegmental area (VTA), the center of the brain's reward circuit, GABAergic neurons control the excitability of dopamine (DA) projection neurons and are the site of initial psychostimulant-dependent changes in signaling.

Keywords: GABA(B), GIRK, inhibition, phosphatase, PLA, trafficking

Abstract

Addictive drugs usurp the brain's intrinsic mechanism for reward, leading to compulsive and destructive behaviors. In the ventral tegmental area (VTA), the center of the brain's reward circuit, GABAergic neurons control the excitability of dopamine (DA) projection neurons and are the site of initial psychostimulant-dependent changes in signaling. Previous work established that cocaine/methamphetamine exposure increases protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) activity, which dephosphorylates the GABABR2 subunit, promotes internalization of the GABAB receptor (GABABR) and leads to smaller GABABR-activated G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) currents in VTA GABA neurons. How the actions of PP2A become selective for a particular signaling pathway is poorly understood. Here, we demonstrate that PP2A can associate directly with a short peptide sequence in the C terminal domain of the GABABR1 subunit, and that GABABRs and PP2A are in close proximity in rodent neurons (mouse/rat; mixed sexes). We show that this PP2A-GABABR interaction can be regulated by intracellular Ca2+. Finally, a peptide that potentially reduces recruitment of PP2A to GABABRs and thereby limits receptor dephosphorylation increases the magnitude of baclofen-induced GIRK currents. Thus, limiting PP2A-dependent dephosphorylation of GABABRs may be a useful strategy to increase receptor signaling for treating diseases.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Dysregulation of GABAB receptors (GABABRs) underlies altered neurotransmission in many neurological disorders. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is involved in dephosphorylating and subsequent internalization of GABABRs in models of addiction and depression. Here, we provide new evidence that PP2A B55 regulatory subunit interacts directly with a small region of the C-terminal domain of the GABABR1 subunit, and that this interaction is sensitive to intracellular Ca2+. We demonstrate that a short peptide corresponding to the PP2A interaction site on GABABR1 competes for PP2A binding, enhances phosphorylation GABABR2 S783, and affects functional signaling through GIRK channels. Our study highlights how targeting PP2A dependent dephosphorylation of GABABRs may provide a specific strategy to modulate GABABR signaling in disease conditions.

Introduction

GABAB receptors (GABABRs) are widely expressed in the nervous system and localized to extrasynaptic sites both pre- and postsynaptically. Activation GABABRs dampens neuronal activity through several parallel pathways, including activation of G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels and inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels and adenylyl cyclases. GABABRs are obligatory heterodimers consisting of two structurally similar subunits, whereby the GABABR1 contains the ligand binding site, and GABABR2 contains binding sites for allosteric modulators and couples to G-proteins (Galvez et al., 2000, 2001). Surface expression of GABABRs is determined by multiple tightly regulated trafficking processes, including ER export, internalization, recycling and degradation (Benke et al., 2012). Abnormal expression and signaling of GABABRs has been associated with many psychiatric illnesses, including epilepsy, depression, anxiety and drug addiction (Bowery, 2006). Understanding the regulatory pathways of GABABR trafficking will help us devise ways to remedy GABABR signaling in disease conditions.

GABABRs undergo agonist-induced desensitization, as well as cross-desensitization induced by activation of other receptors. Desensitization involves relatively fast processes at the level of G-protein signaling and a slower process of receptor endocytosis (Raveh et al., 2015). GABABRs are known to undergo constitutive endocytosis, followed by either degradation or recycling back to the plasma membrane (Vargas et al., 2008). How cells differentially regulate these pathways during receptor desensitization remains unclear. Unlike other GPCRs, GABABR desensitization does not involve phosphorylation by G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs). They are, however, phosphorylated by PKA, AMPK and CaMKII enzymes, with the former two stabilizing the receptor on the cell surface, and the latter promoting endocytosis and degradation (Couve et al., 2002; Kuramoto et al., 2007; Guetg et al., 2010; Zemoura et al., 2019).

We previously demonstrated that the phosphorylation status of Serine 783 (S783) on GABABR2 determines receptor fate during postendocytic sorting, whereby phosphorylation by AMPK promotes recycling, and dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) leads to lysosomal degradation (Kuramoto et al., 2007; Terunuma et al., 2010). Importantly, AMPK and PP2A activities are ideally balanced at basal conditions. Ischemic injury or transient anoxia results in AMPK activation and enhance S783 phosphorylation on GABABRs, promoting GABABR signaling and neuronal survival (Kuramoto et al., 2007). In cortical neurons, sustained NMDAR activation leads to a transient activation of AMPK and a corresponding transient increase in S783 phosphorylation/surface GABABR expression, which is followed by a sustained decrease that is PP2A dependent (Terunuma et al., 2010). Whether PP2A directly dephosphorylates S783 is yet uncertain, but PP2A was pulled down by GABABR1 subunit (Terunuma et al., 2010), suggesting a possible direct interaction between the two.

PP2A-mediated regulation of GABABR-GIRK signaling has thus far been observed in multiple brain regions in response to various stimuli. A single injection of psychostimulant leads to sustained depression of GABABR-GIRK currents in VTA GABA neurons (Padgett et al., 2012). This effect can be abolished by acutely inhibiting PP2A, and is absent in mice with a S783A mutation (Padgett et al., 2012; Munoz et al., 2016), suggesting that PP2A exerts its influence by regulating S783 phosphorylation. Furthermore, in layer 5/6 pyramidal neurons of the prelimbic cortex, a PP2A-dependent suppression of GABABR-GIRK was observed following repeated cocaine exposure (Hearing et al., 2013). Acute foot shocks resulted in a decrease in GABABR-GIRK signaling in lateral habenula (LHb) neurons at 1 h after the shock but persists for at least 2 weeks. PP2A inhibition rescued GABABR-GIRK currents as well as depressive-like behavioral phenotypes following foot shock stress (Lecca et al., 2016).

Together, these studies point to PP2A as a potential target for regulating aberrant GABABR signaling. However, PP2A is a ubiquitous phosphatase with highly diversified families of B subunits (Sontag, 2001; Slupe et al., 2011) and specific targeting of PP2A-GABABR interaction remains an important puzzle to solve. In the current study, we examine how PP2A may be directed to the GABABR, and regulate phosphorylation of GABABRs and their signaling through GIRK channels.

Materials and Methods

GST pull-down experiments

GST fusion proteins containing C-terminal deletions of the GABABR1 subunit were prepared as described previously (Couve et al., 2001). Adult male mice (C57BL6) were killed, brains were dissected and then homogenized in pull down assay buffer (50 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.2, 5 mm MgCl2, 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.2% Triton X-100, 50 mm NaF, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 0.1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 μg/ml antipain) using a sonicator. The homogenate was centrifuged at 150,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. Then, 500 μg of supernatant was mixed with 20 μg of the corresponding fusion proteins immobilized on glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (GE Life Sciences), and samples were rotated overnight at 4°C. Beads were washed twice in pull down assay buffer, twice in pull down assay buffer containing 500 mm NaCl, and twice in pull down assay buffer. Associated proteins were eluted in 40 μl of 2× sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblotting with antibodies for PP2A-B55 and PP2A-C. For pull-down, anti-PR55 (PP2A-B55) (clone 2G9; Millipore), anti-PP2Ac (BD Biosciences) and anti-GABABR1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used. All procedures and experiments using rodents were approved by the institutional animal care and use committees at Tufts University and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Immunoprecipitation of native GABABRs in cultured cortical neurons

Cultured cortical neurons were prepared from E18 rat embryo as described previously (Terunuma et al., 2014) and were cultured in B27 containing Neurobasal media for 5 d at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Neurons were then incubated with membrane-permeable TAT-R1-pep or scrambled peptides for 24 h at a concentration of 1 μm. Peptides were synthesized by New England peptide (www.newenglandpeptide.com) and were of >95% purity. The sequence of TAT-R1-pep was Biotin-GRKKRRQRRRPQGRQQLRSRRHPPT and TAT-scrambled was Biotin-GRKKRRQRRRPQGQPQRLRSPRHRT. Neurons were washed twice with PBS and lysed in Buffer A (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mm NaF, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 2 mm sodium orthovanadate, 0.1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 μg/ml antipain). Homogenates were centrifuged at 150,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C, preabsorbed with 40 μl of protein A agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 4°C, and precleared supernatants were incubated with 1 μg of nonimmune IgG or GABABR1 antibodies for 1 h at 4°C. Immune complexes were precipitated with 40 μl of protein A agarose overnight at 4°C, washed twice with Buffer A, twice with 500 mm NaCl containing Buffer A, and finally twice with Buffer A. Immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted in 40 μl of 2× sample buffer, boiled for 3 min, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting. For IP, anti-PR55 (PP2A-B55) (clone 2G9; Millipore), anti-PP2Ac (BD Biosciences), anti-GABABR1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-GABABR2 p783 (Kuramoto et al., 2007) were used.

Mass spectrometry analysis

GABABR1 antibody or IgG were crosslinked onto protein A beads using 0.2 m triethanolamine, pH 8.2 (TEA), in the presence of 40 mm dimethyl pimelimidate (DMP) at room temperature for 30 min. After extensive washing, immunoprecipitation was performed as detailed above with mouse cortical neurons. Precipitated material was separated by SDS-PAGE, stained with Coomassie and bands of interest were excised and digested with trypsin (Nakamura et al., 2016). Samples were then subject to LC-MS/MS at the Yale/NIDA Neuroproteomic Center (https://medicine.yale.edu/keck/nida/general/mission.aspx). MS/MS spectra were searched against the mouse database (Uniprot) using the Sequest 28 analysis program. Peptide matches were considered true matches for ΔCN scores (delta correlation) > 0.2 and XCorr values (cross-correlation) >2, 2, 3, 4 for +1, +2, +3, +4 charged peptides respectively (Table 1). A particular protein would be considered present if at least five such high-quality peptides were detected. Proteins in detergent solubilized extracts of cortical neurons that were purified on control IgG were considered as nonspecific.

Table 1.

Proteins immunoprecipitated with GABABRs from cultured cortical neurons

| Protein ID | Protein name | IgG, % coverage | R1, % coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| USMG5 | Up-regulated during skeletal muscle growth protein | 0 | 25.9 |

| RL39 | 60S ribosomal protein L39 | 0 | 19.6 |

| RL37A | 60S ribosomal protein L37a | 0 | 14.7 |

| CNRP1 | CB1 cannabinoid receptor-interacting protein 1 | 0 | 9.8 |

| PROF1 | Profilin-1 OS = Mus musculus | 0 | 8.6 |

| GDIR1 | Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 1 | 0 | 7.8 |

| RS26 | 40S ribosomal protein S26 | 0 | 7.8 |

| RS15A | 40S ribosomal protein S15a | 0 | 6.9 |

| DPYL1 | Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 1 | 0 | 7.25 |

| RL27A | 60S ribosomal protein L27a | 0 | 6.8 |

| H10 | Histone H1.0 | 0 | 6.7 |

| COF1 | Cofilin-1 OS= | 0 | 6.6 |

| KV5A5 | Ig kappa chain V-V region T1 | 0 | 8.95 |

| RAB2A | Ras-related protein Rab-2A | 0 | 6.1 |

| RAP2A | Ras-related protein Rap-2a | 0 | 6 |

| CANB1 | Calcineurin subunit B type 1 | 0 | 5.9 |

| OTUB1 | Ubiquitin thioesterase OTUB1 | 0 | 5.5 |

| RS16 | 40S ribosomal protein S16 | 0 | 5.5 |

| RL9 | 60S ribosomal protein L9 | 0 | 5.2 |

| RL11 | 60S ribosomal protein L11 | 0 | 6.5 |

| RAB5A | Ras-related protein Rab-5A | 0 | 5.1 |

| NDUS3 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 3, mitochondrial | 0 | 4.9 |

| TPM3 | Tropomyosin alpha-3 chain | 0 | 4.6 |

| PGAM1 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | 0 | 5.7 |

| RL7 | 60S ribosomal protein L7 | 0 | 4.1 |

| HNRPD | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D0 | 0 | 3.9 |

| PP2AA | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A catalytic subunit alpha isoform | 0 | 3.6 |

| ERLN1 | Erlin-1 | 0 | 3.5 |

| SC6A1 | Sodium- and chloride-dependent GABA transporter 1 | 0 | 3.5 |

| EF1G | Elongation factor 1-gamma | 0 | 3 |

| SFXN5 | Sideroflexin-5 | 0 | 2.9 |

| SERA | D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | 0 | 2.8 |

| 2ABA | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A 55 kDa regulatory subunit B alpha isoform | 0 | 2.7 |

| ROA3 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A3 | 0 | 2.6 |

| NDUAA | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 10, mitochondrial | 0 | 2.5 |

| GUAD | Guanine deaminase | 0 | 2.5 |

| Sep-05 | Septin-5 | 0 | 2.4 |

| NPTN | Neuroplastin | 0 | 2.65 |

| Sep-03 | Neuronal-specific septin-3 | 0 | 2.3 |

| ARP3 | Actin-related protein 3 | 0 | 2.2 |

| PFKAM | ATP-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase, muscle type | 0 | 1.6 |

| TCPG | T-complex protein 1 subunit gamma | 0 | 2 |

Shown are the results of mass spectrometry analysis of proteins immunoprecipitated with antibodies against GABABR1 or IgG from mouse cortical neurons. Samples were digested with trypsin and subjected to LC-MS/MS to identify proteins precipitated with GABABR1 antibodies. The percentage coverage of each target protein is shown. The experimental data represent mean of two samples analyzed in parallel (duplicates). Note detection of PP2A-Cα (PP2AA) and PP2A-B55α (2ABA) subunits.

Cell culture and proximity ligation assay (PLA)

HEK293 cells were cultured in poly-d-lysine coated 12-well plates containing DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1× Glutamax, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, at 37°C in a humidified air incubator with 5% CO2. Cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 with cDNA plasmids expressing GABABR1-eYFP, GABABR2 and GIRK2a. 24 h posttransfection cells were trypsinized and transferred to poly-d-lysine coated 8-well chamber slides and allowed to settle for 4–5 h. Cells were then fixed with 2% PFA in PBS for 7 min and permeabilized with PBS-0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min before PLA assay.

For PLA with neurons, cerebral cortices of E18 C57B6/J mice were dissected in ice-cold HBSS supplemented with 10 mm HEPES and meninges were carefully removed. Cortical tissue was trimmed into pieces and incubated with 0.25% trypsin at 37°C for 15 min. Tissue was washed and triturated in culture media (Neurobasal Plus media supplemented with B-27 Plus, Glutamax and Pen-Strep; Invitrogen) using fire-polished thin glass pipettes. Cells were filtered through a 40 μm nylon cell strainer, counted and plated onto poly-d-lysine coated 8-well chamber slides (Falcon) at 5.7 × 105 cells/cm2. Half media exchanges were performed every 2 d and 1 μm AraC was applied on DIV2 to inhibit non-neuronal cell proliferation. PLA was performed on days in vitro (DIV) 6.

PLA was performed using Duolink in situ reagents (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer's instructions. Anti-rabbit PLUS and anti-mouse MINUS PLA probes and red detection reagents were used. For cortical neurons, MAP2 immunostaining was performed alongside PLA procedures. Slides were imaged with a digital camera (Canon) on a Zeiss fluorescence microscope with a 40× objective for HEK293 cells and 20× objective for cortical neurons. Exposure times, scope settings and lamp power were kept consistent for different experimental groups. PLA signals were quantified with particle analysis function in ImageJ after setting an appropriate threshold to filter out background signal. Cell numbers were counted manually. Antibodies used for PLA: anti-PP2A-C (Cell Signaling Technology #2038), anti-PP2A-B55 (Thermo Fisher MA5-15007), anti-GABABR1 (NeuroMab clone N93A/49), anti-GABABR2 (Thermo Fisher PA5-23720), anti-MAP2 (Abcam ab5392).

Electrophysiology in cultured cortical neurons

Rat cortical neurons were dissected as described above and plated onto glass coverslips at a density of 300,000 per 35 mm dish. Neurons were incubated in modified Neurobasal media (B27, Glutamax, glucose, Pen/Strep; Thermo Fisher) for 18–21 d before recordings. Recordings were performed in a bath solution containing (in mm) 140 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 2.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 11 glucose, pH 7.4 by NaOH. AP5 (50 μm), DNQX (20 μm), picrotoxin (100 μm) and TTX (500 nm) were added to the bath to block NMDA, AMPA, GABAARs and NaV channels, respectively. Baclofen (10 μm) was used for GABABR activation. The patch-pipette solution contained the following (in mm): 135 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 2 disodium-ATP, 2 Mg-ATP, 0.4 Na-GTP, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 by KOH. All reagents were purchased from Tocris Biosciences. The synthetic peptides were added directly to the patch-pipette solution at a working concentration of 50 μm. R1-pep contained amino acids RQQLRSRRHPPT and scrambled contained amino acids QPRTPRHLSQRR. Recordings were performed at a holding potential of −50 mV and at 34°C. Series resistance was monitored every 3 min to ensure that the recordings were stable over time. All data were acquired using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and pClamp software (Molecular Devices).

Experimental design and statistical analyses

The design of experiments in this study involved either comparing two groups (e.g., PLA vs one control, experimental vs control peptide), or multiple groups (e.g., PLA vs multiple controls). Sexes were mixed for all experiments, except for males used in GST pull-down experiments. For statistical analyses of two groups, we used a ratio-paired or unpaired Student's t test (one or two-tailed). For statistical analyses of multiple groups, we used one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test for significance (p-value) between groups, with the significance indicated in the text. All calculations and comparisons were determined in Prism software (GraphPad) and values reported as mean ± SEM or in scatter plots with mean indicated by solid bar.

Results

PP2A is a trimeric protein consisting of a structural A subunit, a catalytic C subunit, and a regulatory B subunit (Sontag, 2001; Slupe et al., 2011). Previously, we found that the PP2A C subunit associates with GABABRs and specifically the GABABR1 subunit in a pull-down experiment with GST-GABABR1 (Terunuma et al., 2010). Here we confirmed this interaction by mass spec analysis of proteins immunoprecipitated from cortical neurons with GABABR1 antibody. We detected both the PP2A-Cα subunit and B55α subunit in precipitated material using the GABABR1 antibody, but not control IgG (Table 1). Next we sought to identify the amino acid sequence on GABABR1 that mediates this protein-protein interaction. To do so, we exposed the cytoplasmic domain of the R1 subunit (amino-acids 857–961) expressed as a glutathione-S-transferase fusion protein (GST-R1) to detergent solubilized brain extracts (Fig. 1A,B). To assess recruitment of PP2A, we immunoblotted GST pulldown material with an antibody that recognizes the catalytic subunit (PP2A-C), a core component of this divergent family of phosphatases. PP2A-C was bound to GST-R1, but not to GST alone. The PP2A-B55 subunit was also detected, indicating binding to GST-R1 (Fig. 1C). To further delineate which amino acids support binding to PP2A, we used shorter fusion proteins encoding distinct regions of GABABR1 subunit cytoplasmic domain Δ1–Δ6 (Fig. 1B). Compared with GST-R1, Δ1 and Δ3 exhibited reduced binding to PP2A-C and PP2A-B55 from brain lysates, while Δ4 and Δ5 showed little or no binding (Fig. 1C,D). Together, these results suggest that residues 917–927 are important in mediating the binding of GABABR1 to PP2A (Fig. 1B–D). Consistent with this conclusion, Δ6, which contains residues 905–928, was the smallest region that retained some interaction with PP2A.

Figure 1.

Identification of the PP2A binding site in GABABR1 C-terminal domain. A, Diagram shows binding of PP2A (consisting of A–C subunits) to the C-terminal domain of the GABABR1 subunit. B, Schematic of seven different GST-tagged C terminal GABABR1 constructs used to localize the region of R1 involved in binding to PP2A. Numbers indicate amino acid positions in the full-length GABABR1 subunit. C, Immunoblot of pull-down. GABABR1 fusion proteins or GST alone were exposed to mouse brain lysates and bound proteins were subject to immunoblotting with antibodies against B55 (PR55), and C subunits of PP2A. Control lane shows input of PP2A enzyme. Bottom gel shows equal loading of GST fusion proteins revealed by Coomassie Blue staining. D, Bar chart shows the levels of PP2A binding to the different GABABR1 fusion proteins determined after subtracting background binding to GST alone. Mean ± SEM is shown for three separate experiments.

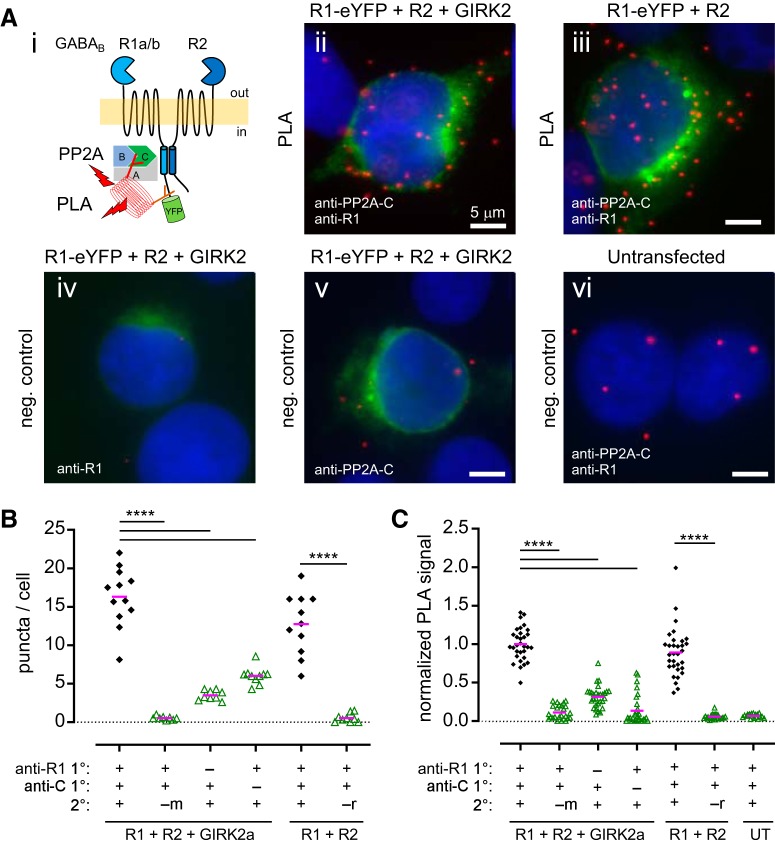

To test whether the interaction between PP2A and GABABR occurs in a living cell, we performed an in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) with HEK293 cells transfected with GABABR1 and GABABR2 subunits. PLA is a sensitive method that detects protein-protein interactions with single-molecule resolution (Weibrecht et al., 2010; Koos et al., 2014). The proximity of antibodies against two interacting proteins allows ligation of DNA strands conjugated to the antibodies, forming a circular DNA template. The circular DNA is then amplified by PCR, and detected by fluorescent DNA-binding probes (Fig. 2Ai). Thus, each fluorescent puncta corresponds to one protein–protein complex. We first tested for interaction between endogenous PP2A and transiently expressed GABABRs (Fig. 2A) in HEK293 cells. Antibodies against the PP2A catalytic subunit (PP2A-C) and GABABR1 C terminus (R1) revealed a strong PLA signal (quantified as puncta per cell) in HEK293 cells transfected with GABABR1 and GABABR2 (Fig. 2Aiii). eYFP fused to the GABABR1 subunit allowed detection of transfected cells. We also performed PLA in HEK293 cells cotransfected with GIRK2, a downstream effector of GABABR that has been demonstrated to coassemble with GABABRs (Kulik et al., 2006; Fowler et al., 2007; Fernández-Alacid et al., 2009; Ciruela et al., 2010). The presence of GIRK2, however, did not significantly increase the PLA signal between PP2A-C and GABABR1 (Fig. 2C). For negative control, we performed two types of experiments. In the first negative control, we omitted the primary antibody but used both PLA probes. For the second control, we omitted one secondary PLA probe. In both cases, we found significantly fewer puncta. (Fig. 2A–C). The PLA signal was significantly smaller (p < 0.0001), and may represent background due to nonspecific antibody/probe binding (Fig. 2Aiv–Av,B,C). In untransfected HEK cells, we also observed background levels of puncta (Fig. 2Avi,C). HEK293 cells are reported to express GABABR1 but not GABABR2 mRNA (Atwood et al., 2011). Without GABABR2, however, GABABR1 cannot traffic to the cell surface and is trapped in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) due to an ER retention signal present in the C-terminal domain (Couve et al., 1998; Margeta-Mitrovic et al., 2000; Pagano et al., 2001). Whether the weak PLA signal we observed in untransfected cells could come from native GABABR1 in the ER remains unknown.

Figure 2.

Interaction between PP2A and GABABR full-length proteins as detected by proximity ligation assay (PLA) in HEK293 cells. Ai, Schematic of the PLA reaction between PP2A (antibody against C subunit) and eYFP-tagged GABABR (antibody against GABABR1 C terminus). Aii–Avi, Representative PLA images of HEK293 cells for the indicated experimental conditions: HEK293 cells were transfected with the cDNAs indicated above each image, and primary antibodies used for PLA are indicated (bottom left). Green: eYFP signal indicating transfected cells. Red is the PLA signal; each red puncta represents a single PP2A-GABABR complex. Blue is DAPI staining. B, Scatter plot shows quantification of PLA signal from one representative experiment. Each data point represents analysis of one image containing 1–11 HEK cells. Presence or absence of primary antibodies and secondary probes (m, mouse; r, rabbit) are indicated below. Magenta bar indicates mean. ****p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test (F(5,53) = 70.76). C, Scatter plot of normalized PLA signal pooled from three independent experiments. Data points were normalized to the R1 + R2 + GIRK2a PLA condition (first column). UT, Untransfected. Magenta bar indicates mean (****p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test; F(6,182) = 134.5).

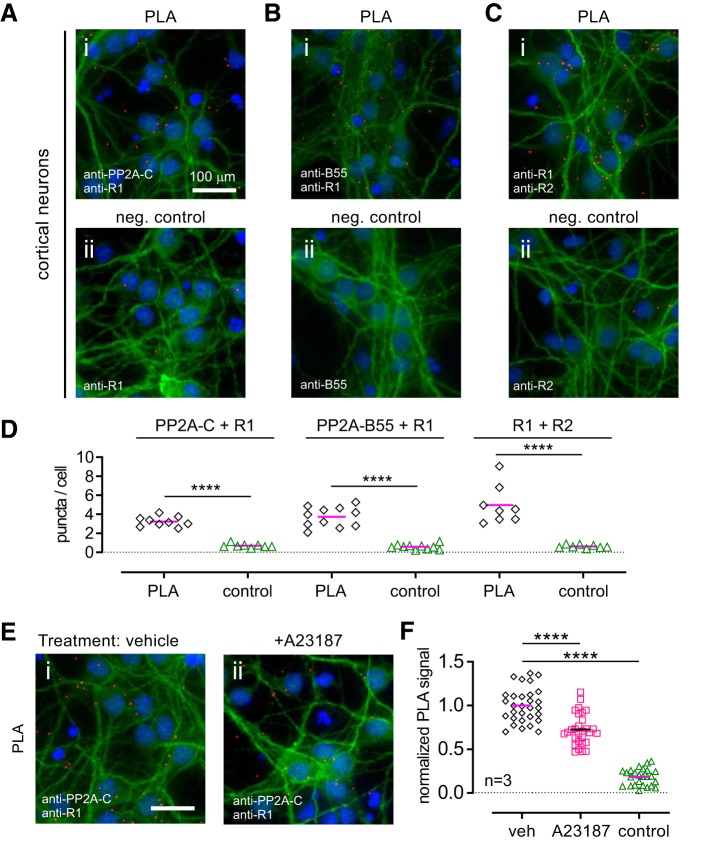

Having shown a positive PLA signal with transfected HEK293 cells, we investigated whether the close association of PP2A with GABABRs also occurs with natively expressed proteins in neurons. We probed for interaction between GABABR1 and PP2A-C subunit, as well as between GABABR1 and the PP2A regulatory B55 subunit, in cultures of mouse cortical neurons. As a positive control for the PLA we tested for interaction between GABABR1 and GABABR2. We detected robust PLA signals for all three conditions, whereas very few puncta were seen with negative controls (one primary antibody omitted) (Fig. 3A–D). The PLA signals were detected in both the soma and dendrites (marked by MAP2 immunostaining). The PLA signals quantified as puncta per cell were significantly higher than negative controls for association between PP2A-C subunit and GABABR1 (p < 0.0001), PP2A-B55α (p < 0.0001), and GABABR1 (p < 0.0001), as well as GABABR1 and GABABR2 subunits (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Evidence for interaction of endogenous PP2A and GABABR in cultured cortical neurons. A–C, Representative PLA images of cultured mouse cortical neurons (DIV 6) with the indicated primary antibodies. Top three panels (Ai, Bi, Ci) show PLA signal (red) between PP2A-C subunit and GABABR1, PP2A-B55 and GABABR1, and between GABABR1 and GABABR2 subunits. Bottom three panels (Aii, Bii, Cii) show corresponding negative controls where a primary antibody was omitted. Green is MAP2 immunostaining; red is PLA signal; blue is DAPI staining. D, Scatter plot showing quantification of PLA signal corresponding to A–C from one representative experiment. Each data point represents analysis of one image containing ∼80 neurons. Magenta bar indicates mean. ****p < 0.0001 using unpaired Student's two-tailed t test. E, F, Regulation of PP2A-C and GABABR1 interaction by intracellular Ca2+. E, Representative images of DIV 6 cortical neurons treated with vehicle (Ei) or the calcium ionophore A23187 (2 μm, Eii) for 30 min before PLA for PP2A-C and GABABR1. F, Scatter plot showing normalized PLA signal pooled from three independent experiments. Data points were normalized to the vehicle average for each experiment. Control group received vehicle treatment but the PP2A-C antibody was omitted. Red bar indicates group mean for three experiments (****p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test; F(2,81) = 167.8).

Next, we investigated whether the association between PP2A and GABABR is physiologically regulated. We showed previously that increases in intracellular Ca2+ level, which models elevated neuronal activity, can enhance phosphorylation of S783 on GABABR2 (Terunuma et al., 2010). A high Ca2+ level activates AMP-dependent protein kinase (AMPK), which has been shown to phosphorylate S783 (Kuramoto et al., 2007; Terunuma et al., 2010). We hypothesized that under high Ca2+ level there is a concomitant decrease in PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation of S783 and potentially a decrease in the PP2A-GABABR interaction. To test this hypothesis, we treated neurons with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (2 μm) for 30 min, a condition that led to increased S783 phosphorylation in cortical neurons (Terunuma et al., 2010). In A23187-treated cells, we observed a significant decrease in the PLA signal for PP2A-C and GABABR1, compared with vehicle-treated neurons (Fig. 3E,F). Together, the PLA studies demonstrate that PP2A can associate with full-length GABABRs in different cell types, and that it is a dynamic interaction regulated by intracellular Ca2+.

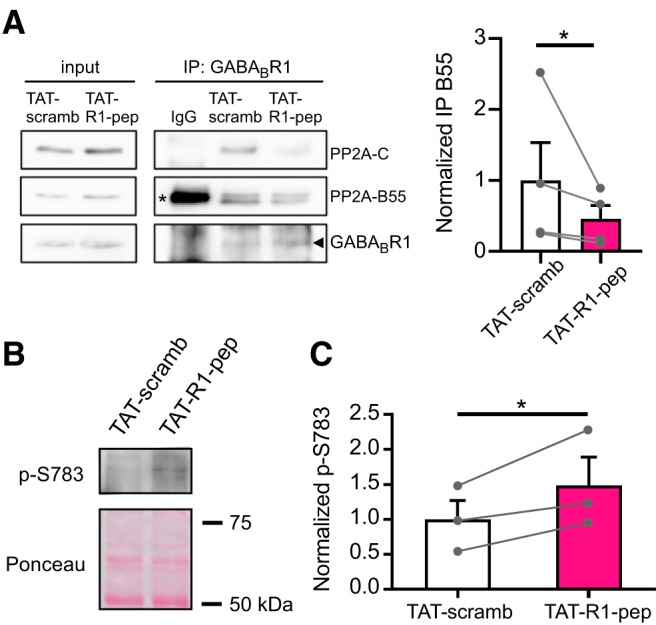

If the direct association of PP2A with the GABABR is important for dephosphorylating p-S783, then we hypothesized that a R1 peptide that competes for PP2A binding might reduce the dephosphorylation, and therefore increase p-S783 (Terunuma et al., 2010). To test this hypothesis, we designed a new R1 peptide (TAT-R1-pep) that contains a TAT sequence (Green and Loewenstein, 1988) for crossing the plasma membrane and examined the effect in cultures of cortical neurons. TAT-R1-pep which competes for binding of PP2A to native GABABR1 reduced the amount of both PP2A B and C subunits that associates with GABABR1 in coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 4A). In addition, TAT-R1-pep significantly increased the level of S783 phosphorylation on the R2 subunit suggesting that interaction of PP2A with the C terminus of GABABR1 helps to regulate the phosphorylation state of S783 in GABABR2 (Fig. 1A).

Figure 4.

PP2A binding to GABABR1 modulates the level of phosphorylation at S783 in GABABR2 subunit. A, Coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) of GABABR1 and PP2A from cultured rat neurons treated with membrane permeant TAT-R1-pep or TAT-scrambled peptides. Total lysates (input) shown on the left. Note decrease in PP2A B55 and C subunits with TAT-R1-pep. Bar graph shows the quantification of co-IP (PP2A-B55/R1 ratio) for TAT-R1-pep condition normalized to the TAT-scrambled peptide. Note significant decrease in PP2A with TAT-R1-pep. Mean ± SEM shown with individual points (*p = 0.0122; t = 4.214, df = 3; one-tailed ratio paired t test). Asterisk for IgG control indicates nonspecific signal with secondary antibody. Arrowhead indicates size for GABABR1. B, Increase in phosphorylation of S783 in GABABR2 subunit after TAT-R1-pep treatment. Blot shows Western with antibody recognizing phosphorylated S783 in R2 (p-S783) for scrambled (TAT-scramb) and TAT-R1-pep conditions following immunoprecipitation of the R1 subunit. Ponceau S shows total protein after IP. C, Bar graph shows the quantification of p-S783 phosphorylation for the TAT-R1-pep condition normalized to the TAT-scrambled peptide. Note significant increase in phosphorylation with TAT-R1-pep (*p = 0.0266; t = 4.157, df = 2, one-tailed ratio paired t test).

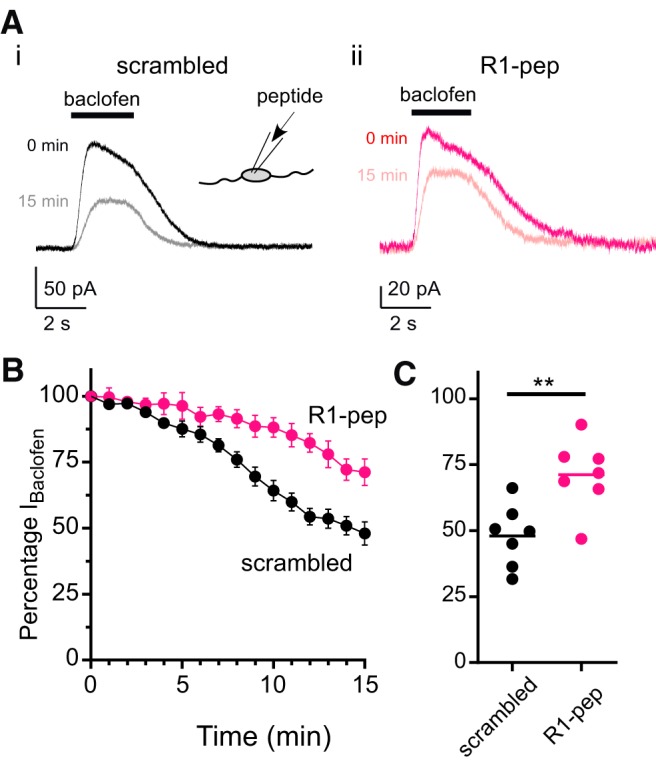

Previous work established that PP2A-dependent dephosphorylation of p-S783 controls surface expression of GABABRs in neurons (Terunuma et al., 2010). To examine if exposure to the GABABR1 peptide affects GABABR function, we measured the rate of current rundown, a phenomenon inherent to whole-cell recordings that is caused by the dialysis of the intracellular milieu and results in the rapid internalization of specific membrane proteins (Kuramoto et al., 2007). Application of baclofen (10 μm) leads to stimulation of GABABRs, which in turn activate the GIRK channels. Baclofen activated an outward current that quickly began to rundown over the course of the 15 min recording (Fig. 5Ai). In cells exposed to the scrambled control peptide, the percentage of current remaining at the end of the recording period was 48 ± 4% (N = 7 neurons) (Fig. 5A–C). By contrast, cells exposed to the R1-pep peptide retained 71 ± 5% (N = 7 neurons) of the baseline current (Fig. 5Aii), which was significantly greater than the control peptide (p = 0.0046, two-tailed unpaired t test) (Fig. 5B,C). In the absence of baclofen, the change in the holding current during the 15 min recording was small and not significantly different with each peptide (10.2 ± 2.9 pA for scrambled, vs 11.7 ± 4.9 pA for R1 peptide, p = 0.7958, unpaired t test). This result suggested there was no nonspecific effect of R1 peptide on membrane currents in the cortical neurons. Together, these data support the conclusion that the physical interaction between the GABABR and PP2A plays a direct role in the internalization of GABABRs (Terunuma et al., 2010).

Figure 5.

R1-pep peptide attenuates rundown of baclofen-activated GIRK currents (IBaclofen) in cultured cortical neurons. A, Representative traces showing baclofen-activated currents recorded from rat cortical neurons at baseline (0 min) and after 15 min for the scrambled peptide (Ai) (QPRTPRHLSQRR, black traces) and PP2A-interfering peptide (Aii) (R1-pep: RQQLRSRRHPPT, magenta traces). Black bars above traces indicate the duration of the baclofen (10 μm) pulse. Holding potential was −50 mV. Inset, Diagram shows inclusion of peptides in the patch pipette and thus directly exposed to the cell interior. B, Plot of the normalized IBaclofen over time for recordings with control peptide (scrambled, black) and R1-pep peptide (magenta). Mean ± SEM is shown (n = 7 cells per condition). C, Dot plot showing the current remaining at 15 min expressed as a percentage of the baclofen-induced current at 0 min for cells exposed to either R1-pep (magenta) or scrambled peptide (black). Bar indicates mean (**p = 0.0046; t = 3.468, df = 12, two-tailed unpaired t test).

Discussion

In this study, we provide evidence that PP2A associates directly with the GABABR through a specific series of amino acids located in the C-terminal domain of the GABABR1 subunit. Disruption of this GABABR1/PP2A interaction appears to reduce dephosphorylation of p-S783 on the GABABR2 subunit, and promote surface expression and functional coupling to GIRK channels in cortical neurons. We discuss the implications of these findings in the context of subcellular signaling and neurological diseases.

PP2A diversity and specificity

Mice injected with psychostimulants exhibit smaller GABABR-activated GIRK currents in VTA GABA neurons, which is expected to increase neuronal excitability of GABA neurons (Padgett et al., 2012; Rifkin et al., 2018). We showed previously that this downregulation of GABABRs was due to PP2A-dependent dephosphorylation of p-S783 and internalization of the GABABR (Padgett et al., 2012). Subsequently, the same PP2A-dependent downregulation of GABABR function was also reported in mPFC and lateral habenula neurons, in response to cocaine and foot shock, respectively (Hearing et al., 2013; Lecca et al., 2016). Similarly, Maeda et al. reported that a PP2A inhibitor suppressed restraint-induced hyperlocomotion in cocaine-sensitized mice (Maeda et al., 2006). Thus, PP2A is emerging as a putative therapeutic target for treating addiction. The challenge, however, is that PP2A is a ubiquitous phosphatase in the body. PP2A is a heterotrimeric complex comprised of three subunits, a catalytic (C), a scaffold (A), and a regulatory (B) subunit (Slupe et al., 2011). Different B subunits provide substrate specificity for PP2A, with the B subunit determining whether PP2A is found in the nucleus, cytosol or attached to the cytoskeleton (Sontag, 2001; Slupe et al., 2011). How the actions of PP2A become selective for a particular signaling pathway is of great interest but poorly understood. Here, we provide new evidence that PP2A associates directly with the GABABR. First, PP2A containing the B55α subunit (see Table 1) coprecipitates with GABABRs and binds to a small region of the GABABR1 C terminal domain. Second, GABABRs expressed either in HEK293 cells or natively in neurons are positioned within a few nm of PP2A, as indicated by a positive PLA signal (Weibrecht et al., 2010; Koos et al., 2014). What promotes the interaction of PP2A with the GABABR? In the striatum, activation of D1Rs leads to increase in cAMP and PKA activation, which in turn phosphorylates PP2A and ultimately leads to dephosphorylation of p-T75 on DARPP-32 (Ahn et al., 2007a,b). The mechanism underlying the increase in PP2A activity with psychostimulants in VTA GABA neurons, however, remains unknown. Experiments suggest elevations in intracellular Ca2+, either through NMDA receptor activation or a Ca2+ ionophore, can regulate the interaction of PP2A with the GABABR. We found that increase in intracellular Ca2+ via the Ca2+ ionophore A23187, leads to a decrease in association of PP2A with the GABABRs (decrease in PLA signal). This would correspond to the initial increase in p-S783 seen with A23187 (Terunuma et al., 2010).

In addition to the PP2A-dependent pathway, GABABR trafficking is also influenced by Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). NMDA-dependent internalization of GABABRs also occurs via activation of CaMKII and phosphorylation of serine 867 (S867) in the C terminal domain of GABABR1 subunit (Guetg et al., 2010). PKA-dependent phosphorylation of S892 on GABABR2 promotes stabilization of the receptor on the plasma membrane (Fairfax et al., 2004) and KCTD12 was recently shown to enhance phosphorylation of S892 (Adelfinger et al., 2014). The interplay of regulatory proteins like PP2A and the balance of phosphorylation provide a complex and dynamic mechanism in regulating the surface expression of GABABRs in neurons.

Binding site and complex formation

The PP2A binding site on GABABR1 was narrowed to the region containing 918RQQLRSRRHPPT929, which is adjacent to the coiled-coil domain of GABABR1 that is involved in dimerization with the GABABR2 subunit (White et al., 1998; Kammerer et al., 1999; Margeta-Mitrovic et al., 2000; Burmakina et al., 2014). The finding that PP2A associates directly with GABABRs provides further support for a GABABR signaling complex that contains a multitude of regulatory proteins. In addition, the GABABR can associate with GIRK channels in a signaling complex (Kulik et al., 2006; Fowler et al., 2007; Fernández-Alacid et al., 2009; Ciruela et al., 2010). GIRK channels can also directly associate with trafficking proteins, such as SNX27 (Lunn et al., 2007; Balana et al., 2011). Indeed, a cluster of proteins has been identified that interact directly with, or close to, GABABRs (this study and (Schwenk et al., 2016)). How these protein-protein interactions are regulated and what is the functional impact remain important questions to be addressed in the future. While the evidence is clear that PP2A associates with and regulates GABABRs in the brain, this association could occur either at the plasma membrane or within intracellular compartments. Although we provide evidence that B55 containing PP2A interacts with GABABR1, whether it is the B55 subunit that mediates the direct binding and whether other families of B subunits could mediate PP2A-GABABR1 interaction remain to be tested.

Tat peptide strategy and disease

PP2A inhibitors have been used successfully in animal models to treat anxiety- and depression-like phenotypes (Lecca et al., 2016; Tchenio et al., 2017; O'Connor et al., 2018). In humans, PP2A inhibitors have been used as chemo-sensitizers in treating cancer (O'Connor et al., 2018). For example, LB-100 is a small molecule inhibitor of the PP2A-C subunit and has been tested in Phase I clinical trials for treating solid tumors in combination with Docetaxel (O'Connor et al., 2018). However, there are unwanted side effects with these broad spectrum PP2A inhibitors. Developing a more targeted approach, such as specifically interfering with the association of PP2A with its target as described in our study (i.e., GABABR) could provide a more efficacious and specific strategy for treating human neurological diseases. The ability of TAT peptides to cross cell membranes makes them an ideal tool for this purpose. We showed that a TAT-R1 peptide can significantly reduce dephosphorylation of GABABRs and affect GABAB-GIRK signaling. It will be of interest in the future to determine if slow synaptic transmission mediated by GABABRs and GIRK channels Lüscher et al. (1997) is also affected by antagonizing the interaction of PP2A with GABABRs. TAT peptides have been used to inhibit β-adrenergic receptor activation of If (Saponaro et al., 2018), to disrupt GluA2 association with GAPDH in vivo, protecting against epilepsy-induced neuronal damage (Zhang et al., 2018), and for interfering with NR2B association with Src, decreasing NR2B tyrosine phosphorylation (Ba et al., 2019). Recently, a TAT-modified ω-conotoxin peptide was shown to cross the blood–brain barrier, providing some analgesia (Yu et al., 2019). Thus, TAT peptides offer a promising option for treatment of brain disorders.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant DA037170 to P.A.S. and S.J.M.; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant AA018734) to P.A.S.; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grants NS051195, NS056359, NS081735, R21NS080064, and NS087662 to S.J.M.; and National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH097446 to S.J.M.); a 2017 NARSAD Young Investigator Grant (X.L.); and the Yale/NIDA Neuroproteomics Center (Grant P30 DA018343 to S.J.M. and A.C.N.). We thank the Slesinger and Moss laboratories for discussions on the experiments.

S.J.M. serves as a consultant for AstraZeneca and SAGE Therapeutics, relationships that are regulated by Tufts University. S.J.M. holds stock in SAGE Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Adelfinger L, Turecek R, Ivankova K, Jensen AA, Moss SJ, Gassmann M, Bettler B (2014) GABAB receptor phosphorylation regulates KCTD12-induced K(+) current desensitization. Biochem Pharmacol 91:369–379. 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn JH, McAvoy T, Rakhilin SV, Nishi A, Greengard P, Nairn AC (2007a) Protein kinase A activates protein phosphatase 2A by phosphorylation of the B56 subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:2979–2984. 10.1073/pnas.0611532104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn JH, Sung JY, McAvoy T, Nishi A, Janssens V, Goris J, Greengard P, Nairn AC (2007b) The B′′/PR72 subunit mediates Ca2+-dependent dephosphorylation of DARPP-32 by protein phosphatase 2A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:9876–9881. 10.1073/pnas.0703589104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood BK, Lopez J, Wager-Miller J, Mackie K, Straiker A (2011) Expression of G protein-coupled receptors and related proteins in HEK293, AtT20, BV2, and N18 cell lines as revealed by microarray analysis. BMC Genomics 12:14. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ba M, Yu G, Yang H, Wang Y, Yu L, Kong M (2019) Tat-src reduced NR2B tyrosine phosphorylation and its interaction with NR2B in levodopa-induced dyskinetic rats model. Behav Brain Res 356:41–45. 10.1016/j.bbr.2018.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balana B, Maslennikov I, Kwiatkowski W, Stern KM, Bahima L, Choe S, Slesinger PA (2011) Mechanism underlying selective regulation of G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium channels by the psychostimulant-sensitive sorting nexin 27. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:5831–5836. 10.1073/pnas.1018645108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benke D, Zemoura K, Maier PJ (2012) Modulation of cell surface GABA(B) receptors by desensitization, trafficking and regulated degradation. World J Biol Chem 3:61–72. 10.4331/wjbc.v3.i4.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowery NG. (2006) GABAB receptor: a site of therapeutic benefit. Curr Opin Pharmacol 6:37–43. 10.1016/j.coph.2005.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmakina S, Geng Y, Chen Y, Fan QR (2014) Heterodimeric coiled-coil interactions of human GABAB receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:6958–6963. 10.1073/pnas.1400081111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruela F, Fernández-Dueñas V, Sahlholm K, Fernández-Alacid L, Nicolau JC, Watanabe M, Luján R (2010) Evidence for oligomerization between GABAB receptors and GIRK channels containing the GIRK1 and GIRK3 subunits. Eur J Neurosci 32:1265–1277. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07356.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couve A, Filippov AK, Connolly CN, Bettler B, Brown DA, Moss SJ (1998) Intracellular retention of recombinant GABAB receptors. J Biol Chem 273:26361–26367. 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couve A, Kittler JT, Uren JM, Calver AR, Pangalos MN, Walsh FS, Moss SJ (2001) Association of GABA(B) receptors and members of the 14–3-3 family of signaling proteins. Mol Cell Neurosci 17:317–328. 10.1006/mcne.2000.0938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couve A, Thomas P, Calver AR, Hirst WD, Pangalos MN, Walsh FS, Smart TG, Moss SJ (2002) Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation facilitates GABA(B) receptor-effector coupling. Nat Neurosci 5:415–424. 10.1038/nn833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairfax BP, Pitcher JA, Scott MG, Calver AR, Pangalos MN, Moss SJ, Couve A (2004) Phosphorylation and chronic agonist treatment atypically modulate GABAB receptor cell surface stability. J Biol Chem 279:12565–12573. 10.1074/jbc.M311389200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Alacid L, Aguado C, Ciruela F, Martín R, Colón J, Cabañero MJ, Gassmann M, Watanabe M, Shigemoto R, Wickman K, Bettler B, Sánchez-Prieto J, Luján R (2009) Subcellular compartment-specific molecular diversity of pre- and post-synaptic GABA-activated GIRK channels in Purkinje cells. J Neurochem 110:1363–1376. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06229.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CE, Aryal P, Suen KF, Slesinger PA (2007) Evidence for association of GABAB receptors with Kir3 channels and RGS4 proteins. J Physiol 580:51–65. 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez T, Prezeau L, Milioti G, Franek M, Joly C, Froestl W, Bettler B, Bertrand HO, Blahos J, Pin JP (2000) Mapping the agonist-binding site of GABAB type 1 subunit sheds light on the activation process of GABAB receptors. J Biol Chem 275:41166–41174. 10.1074/jbc.M007848200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez T, Duthey B, Kniazeff J, Blahos J, Rovelli G, Bettler B, Prézeau L, Pin JP (2001) Allosteric interactions between GB1 and GB2 subunits are required for optimal GABA(B) receptor function. EMBO J 20:2152–2159. 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M, Loewenstein PM (1988) Autonomous functional domains of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus tat trans-activator protein. Cell 55:1179–1188. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90262-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guetg N, Abdel Aziz S, Holbro N, Turecek R, Rose T, Seddik R, Gassmann M, Moes S, Jenoe P, Oertner TG, Casanova E, Bettler B (2010) NMDA receptor-dependent GABAB receptor internalization via CaMKII phosphorylation of serine 867 in GABAB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:13924–13929. 10.1073/pnas.1000909107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing M, Kotecki L, Marron Fernández de Velasco E, Fajardo-Serrano A, Chung HJ, Luján R, Wickman K (2013) Repeated cocaine weakens GABA(B)-girk signaling in layer 5/6 pyramidal neurons in the prelimbic cortex. Neuron 80:159–170. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammerer RA, Frank S, Schulthess T, Landwehr R, Lustig A, Engel J (1999) Heterodimerization of a functional GABAB receptor is mediated by parallel coiled-coil alpha-helices. Biochemistry 38:13263–13269. 10.1021/bi991018t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koos B, Andersson L, Clausson CM, Grannas K, Klaesson A, Cane G, Söderberg O (2014) Analysis of protein interactions in situ by proximity ligation assays. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 377:111–126. 10.1007/82_2013_334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulik A, Vida I, Fukazawa Y, Guetg N, Kasugai Y, Marker CL, Rigato F, Bettler B, Wickman K, Frotscher M, Shigemoto R (2006) Compartment-dependent colocalization of Kir3.2-containing K+ channels and GABAB receptors in hippocampal pyramidal vells. J Neurosci 26:4289–4297. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramoto N, Wilkins ME, Fairfax BP, Revilla-Sanchez R, Terunuma M, Tamaki K, Iemata M, Warren N, Couve A, Calver A, Horvath Z, Freeman K, Carling D, Huang L, Gonzales C, Cooper E, Smart TG, Pangalos MN, Moss SJ (2007) Phospho-dependent functional modulation of GABA(B) receptors by the metabolic sensor AMP-dependent protein kinase. Neuron 53:233–247. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecca S, Pelosi A, Tchenio A, Moutkine I, Lujan R, Hervé D, Mameli M (2016) Rescue of GABAB and GIRK function in the lateral habenula by protein phosphatase 2A inhibition ameliorates depression-like phenotypes in mice. Nat Med 22:254–261. 10.1038/nm.4037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn ML, Nassirpour R, Arrabit C, Tan J, McLeod I, Arias CM, Sawchenko PE, Yates JR 3rd, Slesinger PA (2007) A unique sorting nexin regulates trafficking of potassium channels via a PDZ domain interaction. Nat Neurosci 10:1249–1259. 10.1038/nn1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher C, Jan LY, Stoffel M, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA (1997) G-protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRKs) mediate postsynaptic, but not presynaptic transmitter actions in hippocampal neurons. Neuron 19:687–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Yoshimatsu T, Hamabe W, Fukazawa Y, Kumamoto K, Ozaki M, Kishioka S (2006) Involvement of serine/threonine protein phosphatases sensitive to okadaic acid in restraint stress-induced hyperlocomotion in cocaine-sensitized mice. Br J Pharmacol 148:405–412. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margeta-Mitrovic M, Jan YN, Jan LY (2000) A trafficking checkpoint controls GABA(B) receptor heterodimerization. Neuron 27:97–106. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00012-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz MB, Padgett CL, Rifkin R, Terunuma M, Wickman K, Contet C, Moss SJ, Slesinger PA (2016) A role for the GIRK3 subunit in methamphetamine-induced attenuation of GABAB receptor-activated GIRK currents in VTA dopamine neurons. J Neurosci 36:3106–3114. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1327-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Morrow DH, Modgil A, Huyghe D, Deeb TZ, Lumb MJ, Davies PA, Moss SJ (2016) Proteomic characterization of inhibitory synapses using a novel pHluorin-tagged gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor, type A (GABAA), alpha2 subunit knock-in mouse. J Biol Chem 291:12394–12407. 10.1074/jbc.M116.724443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor CM, Perl A, Leonard D, Sangodkar J, Narla G (2018) Therapeutic targeting of PP2A. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 96:182–193. 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett CL, Lalive AL, Tan KR, Terunuma M, Munoz MB, Pangalos MN, Martínez-Hernández J, Watanabe M, Moss SJ, Luján R, Lüscher C, Slesinger PA (2012) Methamphetamine-evoked depression of GABA(B) receptor signaling in GABA neurons of the VTA. Neuron 73:978–989. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano A, Rovelli G, Mosbacher J, Lohmann T, Duthey B, Stauffer D, Ristig D, Schuler V, Meigel I, Lampert C, Stein T, Prezeau L, Blahos J, Pin J, Froestl W, Kuhn R, Heid J, Kaupmann K, Bettler B (2001) C-terminal interaction is essential for surface trafficking but not for heteromeric assembly of GABA(b) receptors. J Neurosci 21:1189–1202. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01189.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raveh A, Turecek R, Bettler B (2015) Mechanisms of fast desensitization of GABA(B) receptor-gated currents. Adv Pharmacol 73:145–165. 10.1016/bs.apha.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin RA, Huyghe D, Li X, Parakala M, Aisenberg E, Moss SJ, Slesinger PA (2018) GIRK currents in VTA dopamine neurons control the sensitivity of mice to cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E9479–E9488. 10.1073/pnas.1807788115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saponaro A, Cantini F, Porro A, Bucchi A, DiFrancesco D, Maione V, Donadoni C, Introini B, Mesirca P, Mangoni ME, Thiel G, Banci L, Santoro B, Moroni A (2018) A synthetic peptide that prevents camp regulation in mammalian hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels. Elife 7:e35753. 10.7554/eLife.35753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk J, Pérez-Garci E, Schneider A, Kollewe A, Gauthier-Kemper A, Fritzius T, Raveh A, Dinamarca MC, Hanuschkin A, Bildl W, Klingauf J, Gassmann M, Schulte U, Bettler B, Fakler B (2016) Modular composition and dynamics of native GABAB receptors identified by high-resolution proteomics. Nat Neurosci 19:233–242. 10.1038/nn.4198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slupe AM, Merrill RA, Strack S (2011) Determinants for substrate specificity of protein phosphatase 2A. Enzyme Res 2011:398751. 10.4061/2011/398751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontag E. (2001) Protein phosphatase 2A: the trojan horse of cellular signaling. Cell Signal 13:7–16. 10.1016/S0898-6568(00)00123-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchenio A, Lecca S, Valentinova K, Mameli M (2017) Limiting habenular hyperactivity ameliorates maternal separation-driven depressive-like symptoms. Nat Commun 8:1135. 10.1038/s41467-017-01192-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terunuma M, Vargas KJ, Wilkins ME, Ramírez OA, Jaureguiberry-Bravo M, Pangalos MN, Smart TG, Moss SJ, Couve A (2010) Prolonged activation of NMDA receptors promotes dephosphorylation and alters postendocytic sorting of GABAB receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:13918–13923. 10.1073/pnas.1000853107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terunuma M, Revilla-Sanchez R, Quadros IM, Deng Q, Deeb TZ, Lumb M, Sicinski P, Haydon PG, Pangalos MN, Moss SJ (2014) Postsynaptic GABAB receptor activity regulates excitatory neuronal architecture and spatial memory. J Neurosci 34:804–816. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3320-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas KJ, Terunuma M, Tello JA, Pangalos MN, Moss SJ, Couve A (2008) The availability of surface GABA B receptors is independent of gamma-aminobutyric acid but controlled by glutamate in central neurons. J Biol Chem 283:24641–24648. 10.1074/jbc.M802419200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibrecht I, Leuchowius KJ, Clausson CM, Conze T, Jarvius M, Howell WM, Kamali-Moghaddam M, Söderberg O (2010) Proximity ligation assays: a recent addition to the proteomics toolbox. Expert Rev Proteomics 7:401–409. 10.1586/epr.10.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JH, Wise A, Main MJ, Green A, Fraser NJ, Disney GH, Barnes AA, Emson P, Foord SM, Marshall FH (1998) Heterodimerization is required for the formation of a functional GABAB receptor. Nature 396:679–682. 10.1038/25354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Li Y, Chen J, Zhang Y, Tao X, Dai Q, Wang Y, Li S, Dong M (2019) TAT-modified ω-conotoxin MVIIA for crossing the blood–brain barrier. Mar Drugs 17:E286. 10.3390/md17050286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemoura K, Balakrishnan K, Grampp T, Benke D (2019) Ca(2+)/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) beta-dependent phosphorylation of GABAB1 triggers lysosomal degradation of GABAB receptors via mind bomb-2 (MIB2)-mediated lys-63-linked ubiquitination. Mol Neurobiol 56:1293–1309. 10.1007/s12035-018-1142-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Qiao N, Ding X, Wang J (2018) Disruption of the GluA2/GAPDH complex using TAT-GluA2 NT1–3-2 peptide protects against AMPAR-mediated excitotoxicity after epilepsy. Neuroreport 29:432–439. 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]