Abstract

Responsive hydrogels that undergo controlled shape changes in response to a range of stimuli are of interest for microscale soft robotic and biomedical devices. However, these applications require fabrication methods capable of preparing complex, heterogeneous materials. Here we report a new approach for making patterned, multi-material, and multi-responsive hydrogels, on a μm to mm scale. Nanolitre aqueous pre-gel droplets were connected through lipid bilayers in predetermined architectures and photopolymerized to yield continuous hydrogel structures. By using this droplet network technology to pattern domains containing temperature-responsive or non-responsive hydrogels, structures that undergo reversible curling were produced. Through patterning of gold nanoparticle-containing domains into the hydrogels, light-activated shape change was achieved, while domains bearing magnetic particles allowed movement of the structures in a magnetic field. To highlight our technique, we generated a multi-responsive hydrogel that, at one temperature, could be moved through a constriction under a magnetic field; and at a second temperature, could grip and transport a cargo.

Introduction

Remotely controlled shape-changing materials have been employed in soft robotics1–3, actuators4 and biomedical devices5,6. For such applications, fabrication from mechanically compliant, adaptable materials improves usability in challenging operating environments, including movement in confined spaces and in vivo7. Ideal materials should also have inbuilt capabilities for the performance of functions such as sensing and actuation2,7, minimising the need for additional integrated components or external wiring, and thereby allowing the production of tetherless, miniaturized devices3,8. Responsive hydrogels are one such class of soft material. These water-swollen, crosslinked polymeric networks undergo structural changes in response to environmental signals such as temperature, pH and light9. For example, poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm) undergoes a transition from a water-soluble coiled structure to a water-insoluble globular structure, when heated above its lower critical solution temperature (LCST)10. The LCST of PNIPAm is reported to lie between 30 and 35°C10,11. When PNIPAm is the main component of a hydrogel, contraction occurs above the LCST as water is expelled. Unlike other soft materials such as elastomers, responsive hydrogels are permeable to water, which is an attractive property in tissue engineering12, and for the encapsulation and release of biological effectors13.

Despite the potential utility of responsive hydrogels in soft miniature devices, current fabrication methods primarily rely on photolithography and extrusion printing14–16, limiting the preparation of structures beyond flat sheets and filaments. This lack of structural diversity, as well as limitations in patterning and the incorporation of multiple materials, restricts functionality in soft actuators17. For example, the incorporation of multiple responsive materials into shape-morphing devices would allow multi-stimulus control. Multi-stimulus responsive materials have been fabricated with 2D patterning of different materials on top of a common soft sheet. In a recent example, photolithography was used to layer multiple DNA-responsive polyacrylamide hydrogel sheets on top of an inert polyacrylamide hydrogel sheet16. Although not always a requirement of photolithographic approaches, the complex fabrication method in this example required multiple re-alignment steps. Due to cumulative misalignments of the gel layers, a twisting movement was generated under an applied stimulus, instead of the intended folding. Consequently, there is still a need for simple methods to pattern multi-material structures.

Droplet networks have shown promise for the high-resolution patterning of 1D, 2D, and 3D structures comprising aqueous droplets18, which may also contain gelators19,20 or biological molecules21,22. They are constructed from femtolitre to microlitre-sized aqueous droplets, formed in a lipid-containing oil18. The droplets acquire a lipid monolayer and when two are brought together, a lipid bilayer forms at the interface and holds them in place18. Small, manually-assembled 2D networks of aqueous droplets have been used to form functional devices such as batteries23, light sensors23, and electrical components24. Further, large 3D networks constructed with a droplet printer have demonstrated tissue-like properties, including externally triggered communication between compartments21 and the ability to change shape25. In the latter example, the shape change relied on the osmotically driven movement of water across the bilayers and was irreversible.

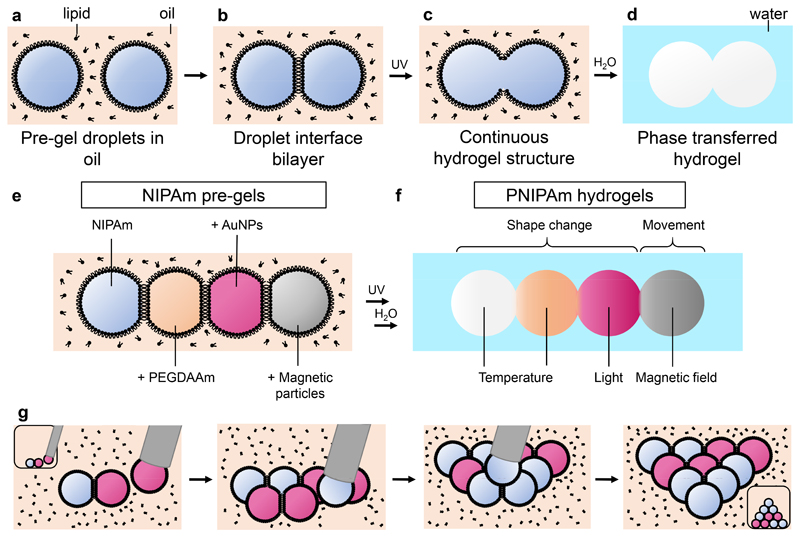

In the present work, we have formed patterned multi-material responsive hydrogels from droplet networks. These networks, assemblies of nanolitre pre-gel droplets, were photopolymerized to generate thermoresponsive μm- to mm-scale PNIPAm hydrogels (Figure 1a-d). Polymerization disrupted the droplet interface bilayers (Figure 1c), resulting in stable and continuous hydrogel structures, which could be transferred into an aqueous environment (Figure 1d). Through the precise placement of droplets containing different pre-gels, which could include additional responsive additives (Figure 1e), patterned multi-material hydrogels were fabricated that responded to a range of external stimuli, including temperature, light and magnetic fields (Figure 1f). Droplet networks were manually assembled from different types of pre-gel (Figure 1g-h). Typically, 50 nL droplets of pre-gel were ejected from a microsyringe in a micromachined well filled with a lipid-containing oil, where a lipid monolayer formed at their surfaces. Droplets were brought into contact and adhered to one another as lipid bilayers formed at the interfaces between them (Figure 1g). Sequential placement of additional droplets containing different pre-gel solutions enabled larger patterned networks to be prepared (Figure 1h-j). The versatility of this strategy in material design and droplet placement opens up new directions for the patterning of soft materials.

Figure 1. Multi-responsive hydrogel structures templated by droplet networks.

a-d, Schematic of the fabrication process for a hydrogel structure templated by a droplet pair. a, Pre-gel droplets are submerged in a lipid-containing oil and acquire lipid monolayer coatings. b, When the two droplets are brought together, a lipid bilayer forms at the interface between them. c, Photopolymerization results in the rupture of the bilayer, and formation of a continuous hydrogel structure. d, Droplet-templated hydrogel structures can be transferred into an aqueous environment. e, Different pre-gels, with the additives PEGDAAm, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) or magnetic nickel particles, can be encapsulated in individual compartments of a droplet network. f, After polymerization, several types of stimulus-responsive hydrogel are integrated into a single patterned structure. g, Schematic showing the assembly of a pre-gel droplet network with 10 droplets from two different pre-gels by placement with a syringe. Insets show views of the assembly process from above.

Results and discussion

Droplets to template and pattern continuous hydrogels

Aqueous nanolitre droplets containing pre-gels were formed in a lipid-containing oil and manually assembled into networks using a microsyringe and pipette tips (Figure 1a, b). Typically, the pre-gel contained a mixture of N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAm) monomer, methylene bis(acrylamide) (MBA) crosslinker and α-ketoglutaric acid (α-KGA) photoinitiator. Upon irradiation at 365 nm, a range of concentrations of NIPAm (0.8-1.5 M), MBA (10-25 mM) and α-KGA (10-100 mM) formed thermoresponsive PNIPAm hydrogels from individual nanolitre droplets in oil. The radii and swelling ratios for the resulting droplets were measured after transfer into water (Supplementary Figure 1). The small size of the droplets (μm diameters and nL volumes) and the requirement of oil for their formation make traditional bulk hydrogel characterisation methods challenging. Despite this, we recorded FTIR spectra of our main PNIPAm hydrogel mixture before and after polymerization in droplets, and compared the data with that from a bulk (μL) hydrogel sample (Supplementary Figure 2). When comparing the droplet-templated hydrogel to the bulk hydrogel, the same two major carbonyl stretching peaks were observed between 1550 and 1650 cm-1 (see Supplementary Methods, section 2.14), indicative of polymer formation. Additional components could be incorporated to modify the stimulus-responsive behaviour and are described later. The lipid-in-oil mixture consisted of a 1:1 v/v mixture of hexadecane and silicone oil AR20, in which 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPhPC) was dissolved to a concentration of 1.2 mM. The combination of hexadecane and silicone oil with DPhPC as the primary lipid is widely used for the formation of stable droplet interface bilayers21,22,25,26. Photopolymerization of a network resulted in rupture of the bilayers and the formation of a continuous PNIPAm hydrogel structure (Figure 1c; Supplementary Figure 3). A variety of robust, free-standing hydrogels with linear, planar and three-dimensional geometries were assembled (Figure 2a-d, left panel). Prior to photopolymerization, the droplets forming the networks were held in place by the lipid bilayers. This allowed the top droplet of a 3D pyramid to be supported by the droplets below, without mixing of the contents (Figure 2d)27. Unlike previously described methods to pattern responsive hydrogels, these 3D structures are formed without a need for scaffold materials beyond the lipid. For this proof-of-principle work, we have assembled these structures manually, using a syringe to produce droplets and a gel-loading micropipette tip to arrange them. Although this fabrication process is manual and thus limited to the formation of structures composed of tens of droplets, automation of the construction process might be achieved with the use of a 3D droplet printer19,25. Such a method may produce structures composed of up to tens of thousands of droplets and will be the focus of future work. In the current work, droplets of different volumes can be used, with the upper limit capped by the stability of the lipid bilayers (becoming more unstable with droplets above 100 nL). A lower volume limit was observed when attempting to reproducibly form cohesive hydrogels with <10 nL droplets, due to challenges associated with both manual assembly of structures and oxygen inhibition of polymerization (see Supplementary Methods, section 2.13). This limits the present resolution achievable with this method without further adaptation. Different bilayer compositions might be used to increase the stability of the droplet interface bilayers when using larger droplets, whilst oxygen removal and scavenging procedures will improve polymerization for with smaller droplets.

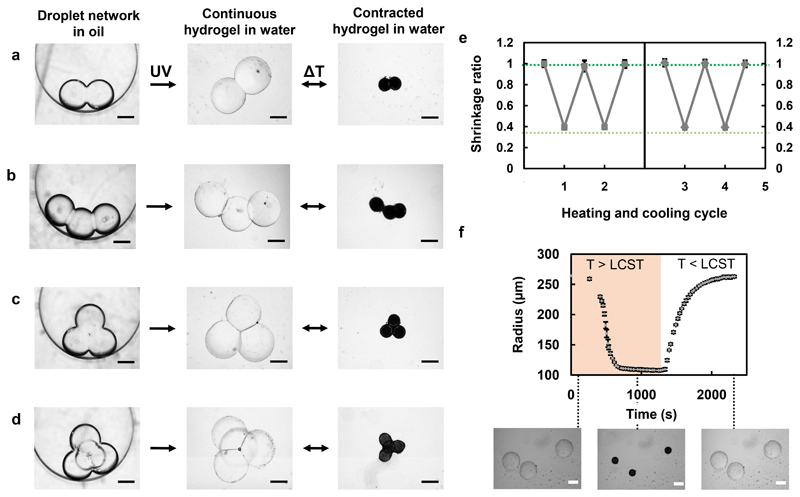

Figure 2. Formation and temperature response of PNIPAm hydrogel structures templated with droplet networks.

a, Brightfield images of a NIPAm pre-gel-containing droplet pair in oil. After UV photopolymerization, a continuous hydrogel structure was formed. The structure was transferred into water and reversible isotropic contraction occurred at 42°C, above the LCST of PNIPAm. b-d, A three-droplet chain (b), three-droplet triangle (c) and four-droplet pyramid (d) were also fabricated and reversibly contracted at 42°C. Structures appear black upon heating above the LCST, due to an increase in the refractive index of PNIPAm. e, Four cycles of heating and cooling were performed for the droplet pair-, chain- and triangle-templated structures. The radii of droplets comprising these structures were measured at 25°C and 42°C, and normalised to their initial radii. The resulting mean shrinkage ratios are shown for each temperature across the cycles. The break in the x axis indicates that two cycles were performed on the structures on two different days. The dark green dotted line delineates the fully swollen structure, whereas the pale green dotted line delineates the fully contracted structure. f, Radii of 3 individual, non-connected PNIPAm droplets measured during contraction, while heating to 42°C, and reswelling, while cooling to room temperature. Error bars in (e) and (f) represent one standard deviation about the mean shrinkage ratio or the radius, respectively. Scale bars correspond to 250 μm.

Following photopolymerization, the structures were transferred into an aqueous environment (Figure 2a-d, centre panel), where they contracted reversibly upon heating to 42°C and cooling to room temperature (Figure 2a-d, right panel). The temperature of 42°C is above the LCST of PNIPAm, and this temperature elevation was used throughout this work, unless otherwise stated. A lag period before deswelling was observed in these experiments due to the time taken for the water bath containing the hydrogel shapes to heat up to the desired temperature (Figure 2f). To monitor the temperature-dependent behaviour of the PNIPAm structures, we analysed the radii of the constituent droplets within 3 different structures over multiple heating and cooling cycles. The "shrinkage ratios" were calculated from the radii of constituent droplets at each temperature, normalized to their initial radii in the fully swollen state. For each structure, we observed the same amount of shrinkage and reswelling over successive cycles (Figure 2e). Furthermore, the structures remained intact over several days and at least four heating and cooling cycles. Additionally, we monitored 3 individual PNIPAm droplets from 25°C to 42°C, and subsequently back to 25°C, and observed that they had the same rate of contraction and reswelling as each other (Figure 2f).

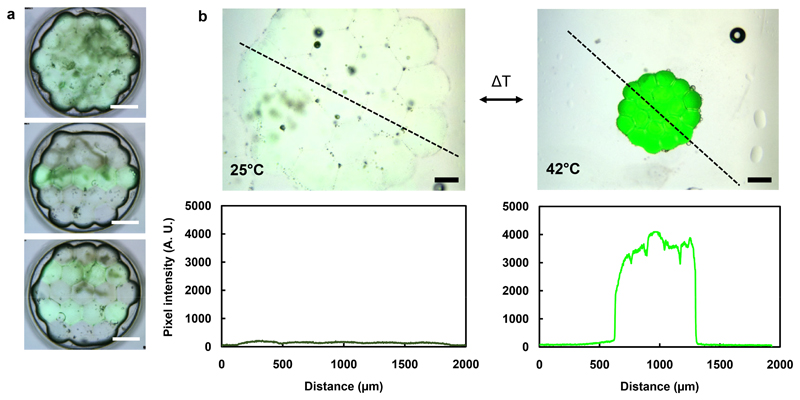

A major advantage of our strategy is that prior to photopolymerization, each droplet is separated from its neighbours by lipid bilayers. We could therefore encapsulate different contents within each of them. Following photopolymerization, multi-material structures could be obtained, in which different hydrogels are present in adjoining domains, based on their positions in the original droplet network. For example, we patterned hexagonal networks containing 19 droplets with and without a bilayer-impermeant fluorescent crosslinker, ethidium bromide bis(acrylamide) (EBBA) (Figure 3a), demonstrating a variety of 2D-patterned hydrogel structures. We monitored the fluorescence, measured along a line profile, of hexagonal PNIPAm structures containing EBBA throughout heating and cooling. As expected, we observed higher EBBA fluorescence upon heating, due to an increase in its local concentration following the decrease in volume of the gel (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. Patterned fluorescent PNIPAm hydrogel structures.

(a) Overlaid brightfield and fluorescence microscopy images of hexagonal hydrogel structures patterned with a fluorescent crosslinker, EBBA. Scale bars correspond to 500 μm. (b) Overlaid brightfield and fluorescence microscopy images, and pixel intensity plot profiles (along the black dashed lines) of fluorescent hexagonal hydrogel structures, before and after heating to 42°C. The pixel intensity increase is due to an increase in local EBBA concentration as a result of temperature-induced contraction. Scale bars correspond to 250 μm.

Temperature-controlled shape change of droplet-templated hydrogels

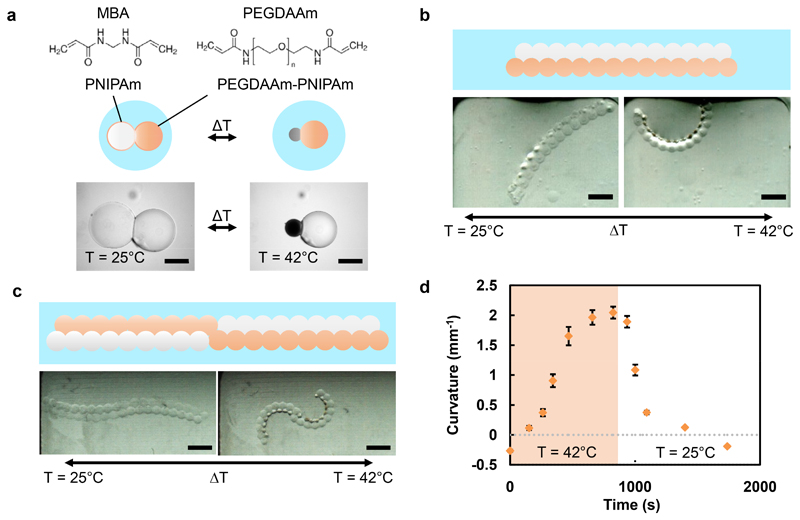

The versatility of our multi-material hydrogel strategy allows fabrication of PNIPAm-based structures capable of shape change, by the design of non-uniform contraction into the assembly. Previously, hydrophilic poly(ethylene glycol)-based crosslinkers have been used to increase the LCST of PNIPAm28, thereby reducing the amount of temperature-controlled contraction achieved at the LCST of unmodified PNIPAm. We formed PNIPAm droplets incorporating a range of concentrations of a poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylamide (PEGDAAm) crosslinker, which comprised a poly(ethylene glycol) chain (Mn = 3700) with an acrylamide functionality at both ends. We found a PEGDAAm concentration-dependent increase in the LCST and decrease in the shrinkage ratio at 42°C (Supplementary Figures 4 and 5), when compared to PNIPAm droplets crosslinked with MBA only (see Supplementary Methods, section 2.14). To produce non-uniform contraction in the structures, droplet networks were assembled from NIPAm-containing droplets with MBA, along with droplets that in addition contained 8 mM PEGDAAm (PEGDAAm-NIPAm). The hydrophilic PEGDAAm was found to be bilayer-impermeant, which allowed patterning of the PEGDAAm within droplet networks. To illustrate non-uniform contraction, a droplet pair was formed from a NIPAm-containing droplet and a PEGDAAm-NIPAm-containing droplet, both containing MBA (Figure 4a). Following photopolymerization, the hydrogel structure underwent non-uniform contraction upon heating, because the PEGDAAm-PNIPAm domain contracted to a lesser extent than the PNIPAm domain crosslinked with MBA only. We designed networks composed of both droplet types that, following photopolymerization, were capable of pre-defined, temperature-controlled shape changes. For example, by forming a parallel double strip of droplets from a chain of NIPAm-containing droplets adhered to a chain of PEGDAAm-NIPAm-containing droplets, we obtained a hydrogel structure that underwent a reversible curling motion upon heating and cooling (Figure 4b). Taking advantage of the versatile patterning capabilities inherent in our approach, we also formed two parallel chains of droplets, in which half of each chain consisted of PEGDAAm-NIPAm-containing droplets and the other half consisted of NIPAm-containing droplets (Figure 4c). After hydrogel formation, a reversible double-curling motion took place upon heating. Due to a difference in swelling of the two hydrogel types, there was a small negative curvature of the initial structure (Figure 4d). However, upon heating, the structure first straightened, before attaining a high positive curvature, and then returning to the initial shape upon cooling.

Figure 4. Shape changes of structures containing two different temperature-responsive hydrogels.

a. A hydrogel structure formed from a droplet pair. One domain contained PNIPAm (white sphere) crosslinked with MBA, and the other in addition contained 8 mM PEGDAAm (n = 80, Mn = 3700) (orange sphere). When heated to 42°C, the PEGDAAm-PNIPAm domain contracted to a lesser extent than the PNIPAm domain (dark grey sphere). Scale bar corresponds to 250 μm. b-c, Larger structures patterned with PNIPAm and PEGDAAm-PNIPAm underwent pre-defined, temperature-controlled, reversible shape changes. A bilayer structure (b) formed from a parallel double strip of droplets with different crosslinkers curls when heated above the LCST of the MBA-containing hydrogel, whereas an alternating bilayer with a central point of inflection (c) undergoes a double curling motion. Scale bars correspond to 1 mm. d, Kinetics of curvature changes for the structure depicted in (c) during heating to 42°C (pale orange) and cooling to room temperature (white). Error bars represent one standard deviation about the mean curvature.

Light-controlled shape change of droplet-templated hydrogels

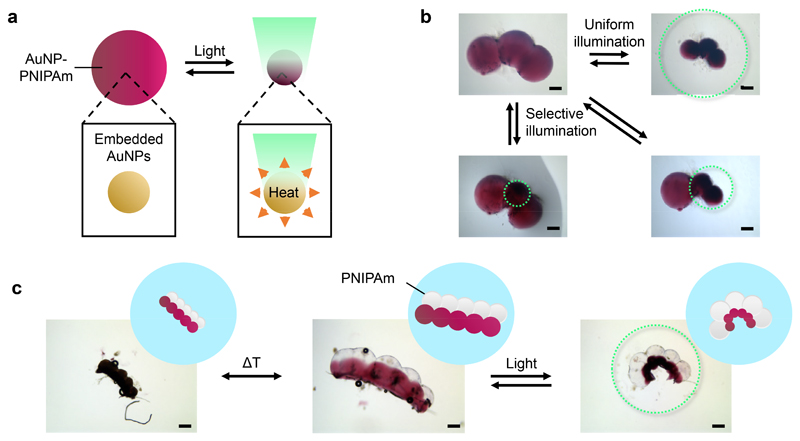

To complement the temperature-controlled shape changes of our structures, we added light-responsive gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) for precision activation through localised photothermal heating (Figure 5a). AuNPs have previously been embedded homogeneously within PNIPAm hydrogels4,29,30. In one example, upon irradiation with green light (λ = 530 nm), surface plasmon-mediated heating4 caused contraction of AuNP-PNIPAm composite hydrogel sheets at the site of illumination. We formed a droplet pair from one NIPAm-containing droplet and one AuNP-NIPAm-containing droplet (Supplementary Figures 6 and 7). Following photopolymerization, we illuminated the entire structure with green light and, within 200 seconds, the AuNP-PNIPAm domain of the hydrogel selectively contracted.

Figure 5. Shape changes of structures containing light-responsive domains.

a. PNIPAm structures containing embedded gold nanoparticles (AuNP-PNIPAm) contract when illuminated with green light (λ = 530 nm). b, Selective light-activated contraction of domains in a AuNP-PNIPAm hydrogel structure by using an aperture-restricted green light source. c, Two modes of deformation of a structure containing PNIPAm (white spheres) and AuNP-PNIPAm (pink spheres) domains. The structure contracts isotropically when heated to 42°C, and curls when irradiated with green light at 25°C. Scale bars correspond to 250 μm. Green dotted circles represent the regions of the structures irradiated with green light in b and c.

Exploiting the spatiotemporal control available with light, we demonstrated selective contraction of individual domains within a hydrogel structure generated from a chain of three AuNP-NIPAm pre-gel droplets (Figure 5b). By using an aperture diaphragm on a light source, a single-droplet domain, two-droplet domain, or the entire hydrogel structure could be contracted. In addition, by photopolymerizing a 2D patterned droplet network comprising both AuNP-NIPAm pre-gel and NIPAm pre-gel droplets, we formed structures programmed to undergo two types of shape change, depending on whether temperature or light was used as a stimulus (Figure 5c). A double strip hydrogel structure was formed from a chain of five AuNP-NIPAm pre-gel droplets joined in parallel to a chain of five NIPAm pre-gel droplets. Following photopolymerization, this structure underwent an isotropic contraction when heated above the LCST, resulting from contraction of both domains. Curling was achieved when the entire structure was irradiated with green light, resulting from photothermal contraction of the AuNP-containing domain. Furthermore, our approach allows 3D placement of several types of droplet, each containing different pre-gels. We used two parallel adjoined chains of droplets to form a base and positioned a third chain on top to form a structure similar to a triangular prism (Supplementary Figure 8). Following this design, we fabricated a 3D multi-material hydrogel structure that underwent a non-uniform shape change in response to light. Non-light-responsive domains were formed by using droplets containing a NIPAm pre-gel, and light-responsive domains were formed by using droplets containing a AuNP-NIPAm pre-gel. Following photopolymerization, we obtained a continuous 3D-patterned multi-material structure, which underwent pre-programmed curling when irradiated with green light, due to contraction of the AuNP-containing domains positioned in each of the chains.

Cargo transport and maze navigation with a dual temperature- and magnetically-controlled hydrogel gripper

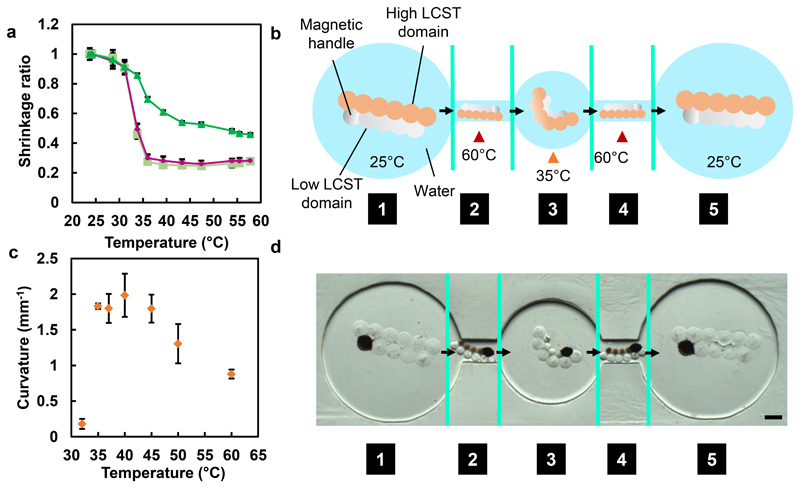

Soft responsive materials are ideal for the fabrication of devices used in narrow, tortuous environments, like those found in vivo, because of their ability to change shape controllably, aiding the navigation of obstacles3. Previously, grippers5,8, able to transport cargo through twisting passages, have been made by photolithography. However, opportunities remain for improving their manoeuvrability, for example, upon encountering constricted openings, which would facilitate their use for cargo transport. Through the combination of different temperature-responsive hydrogels, we made a structure with a magnetic handle that could shrink at one temperature, or curl at another, and be transported in a magnetic field (Figure 6). The dual-temperature-mediated shrinking or curling was achieved by patterning droplets with different LCST properties within the same structure, by using two different concentrations of PEGDAAm (Figure 6a; Supplementary Figure 4). The ability to position droplets containing different pre-gels is a key advantage of droplet-templated hydrogel fabrication. In this example, the concentrations of PEGDAAm used were 3.5 mM, which shrinks at a higher temperature (high LCST domain), and 0.4 mM, which shrinks at a lower temperature (low LCST domain). Consistent with its design, the structure had a low curvature (0.18 ± 0.07 mm-1) below 32°C, and a high curvature (1.83 ± 0.04 mm-1) at 35°C, which decreased when heated beyond 40°C, resulting in an intermediate curvature (0.88 ± 0.06 mm-1) at 60°C (Figure 6c). As a result, this multi-material hydrogel structure curled at 35°C, and shrank at 60°C. The incorporation of magnetic beads into a single droplet within the low LCST domain allowed manipulation of the whole structure with a magnetic field. Once shrunken, the structure could be magnetically translocated through narrow channels, which the original or curled structure could not traverse (Figure 6b).

Figure 6. A magnetically- and dual temperature-responsive shape-changing structure.

a, Temperature dependence of the shrinkage ratio of PNIPAm hydrogel droplets (pale green squares), or droplets containing in addition 1 mM (pink circles) or 3 mM PEGDAAm (dark green triangles). Error bars indicate one standard deviation about the mean shrinkage ratio. b, Design of the multi-responsive shape-changing structure. The low LCST domain contained 0.4 mM PEGDAAm, while the high LCST domain contained 3.5 mM PEGDAAm. A magnetic handle in the low LCST domain contained MagneHis™ Ni-Particles. Initially, the hydrogel structure is trapped in chamber (1). After heating to 60°C, both domains of the structure contract and it can be pulled through a narrow channel by a magnetic field (2). Once in the central chamber, it is cooled to 35°C and becomes curled as the low LCST domain contracts (3). When heated once more to 60°C, it again contracts and can be magnetically pulled through a channel (4) into the final chamber. Here, the hydrogel is cooled to room temperature and returns to its original size and shape (5). Green lines indicate where the temperature has been changed. (c) Temperature dependence of the curvature of the fabricated multi-responsive shape-changing structure. Error bars indicate one standard deviation about the mean curvature of three structures. (d) Brightfield images of the dual-controlled shape-changing structure at positions (1)-(5). Green lines indicate the change in temperature, as well as where images are stitched together. Scale bar corresponds to 500 μm. See Supplementary Figure 10 for uncropped individual images.

The hydrogel structure was placed into a container in which chambers of various sizes were interconnected by 500 μm diameter channels (Figure 6d). Initially, the hydrogel was trapped in a large chamber (1). The structure was contracted to its minimum size by heating to 60°C, when it formed a smaller and slightly curled version of its initial shape. Under the influence of a magnetic field (2), it was then moved through a channel into a second chamber. After cooling to 35°C, the high LCST domain reswelled, trapping the structure in the second chamber. As a result of the local reswelling, the structure also curled (3), to form a “gripper-like” shape in contrast to the original linear structure. After a second contraction by again heating to 60°C, the structure collapsed and was moved by using a magnetic field through the second narrow channel (4) into the final chamber (5), where it was allowed to reswell. Values for the curvature of the hydrogel structure, at the temperatures used, are shown in Supplementary Figure 9.

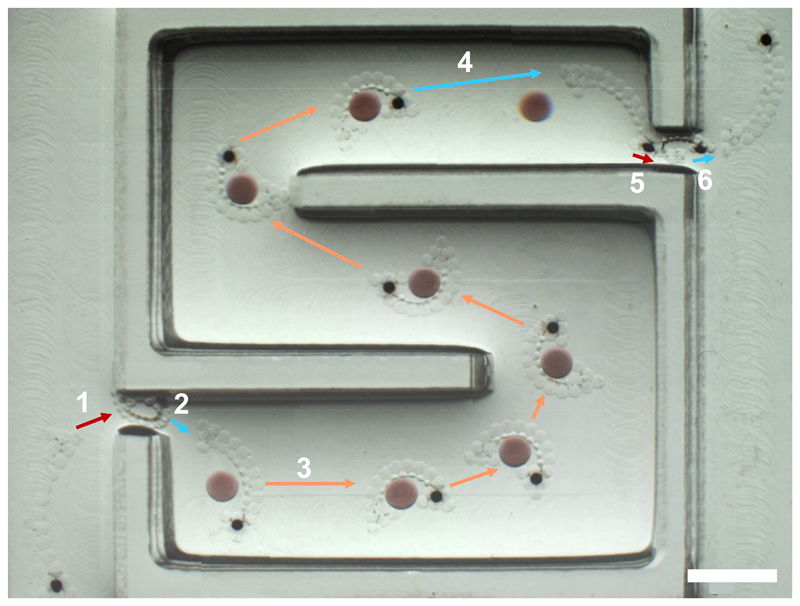

Using this principle, we fabricated a multi-responsive 3D hydrogel gripper comprised of three different hydrogels (Supplementary Figure 11) that is able to transport cargo and navigate a maze (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure 12). The low LCST domain contained PNIPAm crosslinked with MBA only; the high LCST domain contained PNIPAm crosslinked with MBA, and included a magnetic-bead containing handle. When fully swollen in water, the gripper was too large to pass through a 1 mm channel into a maze (1). However, upon heating to 60°C, the gripper was fully contracted such that it was small enough to enter the maze and be pulled through it using a magnet field (2). Cooling to room temperature caused the gripper to swell and straighten (3), before subsequent heating to 42°C allowed it to grip a cargo, a large PNIPAm hydrogel droplet containing AuNPs to improve visibility and PEGDAAm to minimise contraction at the temperature ranges used. With the cargo in its grasp, the gripper was magnetically transported to the end of the maze (4), where it released the cargo upon cooling to room temperature (5). By shrinkage at 60°C once more, the gripper could be magnetically pulled through the exit of the maze (6), where it re-swelled to its original shape. Supplementary Figure 12 shows a 3D multi-responsive hydrogel gripper moving through a more complex maze, including similar contraction for entry and exit. Previous examples of gripping devices have offered limited deformability beyond gripping5,8. By contrast, besides gripping, our device could undergo an overall contraction, which allowed it to enter spaces inaccessible to its swollen state, which could have significant implications for soft materials in microsurgery. It is important to note that the structure needed some 3D sections for the reproducible gripping and transport of the larger cargo droplet. Specifically, the cargo did not remain against the bottom of the maze during transport and required at least some gripping in three dimensions to be held by the shape-changing structure. Comparable 2D structures were unable to effectively hold on to the cargo.

Figure 7. Cargo transport and maze navigation by a magnetically responsive and dual temperature-responsive hydrogel gripper.

1. The gripper, initially outside the entrance to the maze, is fully contracted by heating it to 60°C. The fully contracted gripper can be pulled through a narrow channel at the entrance using a magnetic field. 2. Once inside the maze, it is cooled to room temperature, causing it to swell and straighten, before being heated to 42°C, allowing it to grip a cargo (coloured red). The cargo was a large PNIPAm hydrogel droplet containing AuNPs to improve visibility and PEGDAAm to minimise contraction at the temperature ranges used. 3. With the cargo in its grip, it is transported to the other end of the maze using a magnetic field. 4. Upon reaching the end of the maze, it is cooled to room temperature so that it releases the cargo. 5. The gripper is subsequently fully contracted at 60°C so that it can be pulled through the narrow channel at the exit of the maze. 6. The gripper reswells at room temperature. The images from each location have been stitched together to demonstrate the full path. Scale bar corresponds to 4 mm. See Supplementary Figure 12 for cargo transport and navigation through a more complex maze by a magnetically responsive and dual temperature-responsive hydrogel gripper. See Supplementary Figure 13 and 14 for a reproduction of the composite image with borders of stitched images indicated and uncropped individual images, respectively.

Conclusions

We have described a general method for the fabrication of multi-material, multi-responsive hydrogel structures by photopolymerizing networks of droplets containing different pre-gels. This approach differs from current fabrication methods that rely on photopatterned 2D layers2,14,16 or extrusion printing15. In our method, pre-gel droplets are readily assembled into 2D or 3D patterns. With this voxel patterning, we can create complex multi-material structures, enabling multiple stimulus-controlled shape changes within a single structure. These multi-material structures can respond to a range of stimuli, including temperature, light and magnetic fields. One such structure, a magnetically controllable and dual temperature-responsive gripper, could adapt to traverse a constricted opening while retaining the ability to transport cargo. Our approach might be elaborated to fabricate multi-material hydrogels capable of responding to additional stimuli31, including different wavelengths of light2,30. In addition, our approach will allow the fabrication of responsive hydrogels across multiple length scales, as droplet volumes can range from fL to μL18. Droplet production can even be automated with microfluidics32 and 3D droplet printers25,33. The method might be combined with other fabrication methods to create defined droplet features within larger hydrogel structures. Furthermore, due to similarities in structural features, our multi-responsive structures might also be integrated with droplet network-based synthetic tissues21,25. Accordingly, this approach for the formation of multi-material, multi-responsive μm to mm-sized structures opens up new possibilities for the design of miniaturized soft robotics, biomedical devices and other shape-changing soft materials.

Methods

General procedure for preparation of NIPAm pre-gel

NIPAm, MBA and α-KGA were individually dissolved in MilliQ water. The solutions were then combined to form the pre-gel solutions. Typically, NIPAm (271.7 mg, 2.4 mmol) was added to MilliQ water (1 mL) to yield a NIPAm stock solution (1.84 M, due to increase in volume); MBA (19.3 mg, 0.125 mmol) was added to MilliQ water (1 mL) to yield a MBA stock solution (125 mM), and α-KGA (95 mg, 0.65 mmol) was added to MilliQ water (1 mL) to yield an α-KGA stock solution (650 mM). The standard NIPAm pre-gel mix, which was used unless otherwise stated, contained 90 μL of the NIPAm stock, 15 μL of the MBA stock, 2.5 μL of the α-KGA stock and 17.5 μL MilliQ water, resulting in a final concentration of 1.34 M NIPAm, 13.1 mM MBA and 13.1 mM α-KGA. Further details concerning additional pre-gel preparations are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Preparation of lipid-in-oil

DPhPC (25 mg, 29.5 μmol) was dissolved in chloroform. 5 mg aliquots of the dissolved DPhPC were transferred to glass vials, and the chloroform was evaporated by rotation under a gentle stream of nitrogen to form lipid films. The films were subsequently placed in a desiccator for at least three hours to ensure that all residual chloroform had evaporated. To make a DPhPC lipid-in-oil stock, a lipid film was dissolved in filtered hexadecane (500 μL). The DPhPC stock (typically 100 μL) was diluted with more filtered hexadecane (typically 400 μL), in addition to filtered silicone oil AR 20 (typically 500 μL). This resulted in a final DPhPC concentration of 1.2 mM, and a final hexadecane and silicone oil composition of 1:1 v/v. For fluorescent lipid-in-oil stocks, DPhPC (25 mg) was dissolved in chloroform (1 mL) to make a 25 mg mL-1 (29.5 mM) stock, and Texas Red®-1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (TR-DHPE) (1 mg) was dissolved in chloroform (1 mL) to make a 1 mg mL-1 (0.72 mM) stock. 39 μL of the DPhPC stock and 1.6 μL of the TR-DHPE stock were transferred to a glass vial, and the chloroform was evaporated under nitrogen and then desiccated as previously described, resulting in a lipid film. Hexadecane (500 μL) and silicone oil AR20 (500 μL) were added, to yield a final concentration of 1.2 mM DPhPC with 0.01 mol % TR-DHPE, and a final hexadecane and silicone oil composition of 1:1 v/v.

Droplet network formation

Droplets were formed in custom-made poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) well arrays, produced using a computer numerical control (CNC) milling machine (monoFab SRM-20 Roland, Japan). Depending on the manual arrangement of the droplets in differently shaped well arrays, various patterns were formed. Typically, well arrays were filled with 175 μL of the lipid-in-oil. In each well, droplets of pre-gel solution were formed with a 0.5 μL syringe (7000.5 KH, Hamilton, USA). Droplet networks were then assembled by manually bringing droplets (50 nL unless specified, equivalent to a diameter of approximately 500 μm) into contact with one another and allowing bilayers to form at the interfaces, which happened within seconds. Droplets can be drawn into a gel-loading pipette tip via capillary action. With this method, droplets could be removed, rearranged, and placed in 3D. Further details concerning droplet network assembly are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Photopolymerization of continuous hydrogel structures

Following droplet or droplet network formation, well arrays were placed in a custom-made glass chamber with a sealable inlet and outlet and purged with nitrogen for 45 minutes. Networks within the chamber were then irradiated with UV light for 30 minutes by using a 365 nm collimated LED (M365L2-C5, Thorlabs) on its maximum setting, controlled by an LED driver (set at 1.2 mA; LEDD1B, Thorlabs) from a distance of 2 cm. After photopolymerization, the continuous hydrogel structures were transferred via micropipette into an aqueous environment for imaging and further experimentation (see Supplementary Methods for detail).

Light and fluorescence microscopy

An Olympus SZX10 upright microscope was used for bright-field microscopy. For bright-field and fluorescence imaging, a Leica DMi8 inverted microscope was used with a 5x or 10x objective, unless otherwise stated. For confocal imaging, a Leica SP5 confocal microscope was used with a 10x objective.

Heating and cooling of structures

A Tokai Hit™ Leica TPX (Type HF) Thermo Plate was used to heat the well arrays containing the hydrogel structures. Initially, the plate was set at, typically, 42°C. Then, the temperature reported by the plate sensor was monitored until the desired temperature had been reached. Due to the time taken for the water surrounding the hydrogel structures to reach the temperature reported by the plate sensor, at least 30 min were allowed before imaging the heated hydrogel structures. For cooling to room temperature, the temperature was set, typically, to 25°C. Once the temperature reported by the plate sensor registered the desired temperature, 30 min were allowed for samples to cool down, before further imaging.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a European Research Council Advanced Grant and OxSyBio. FGD and RGK were supported by funding from the EPSRC & BBSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Synthetic Biology (EP/L016494/1). DJL is grateful to the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program for a Marie Curie Global Fellowship (657650). DJL and CJH acknowledge support from the U.S. Army Research Office under Contract Numbers W911NF-09-D-0001/W911NF-19-D-0001 for the Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies. MJB was supported by Merton College. JBS was supported by funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/M011224/1).

Footnotes

Code availability

The MATLAB code used for image analysis in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

FGD and DJL designed, performed, and analysed the experiments, with contributions from MJB, JBS, WR, and RGK. FGD, DJL, MJB and HB wrote the paper. DJL, MJB, CJH and HB supervised the work.

Competing interests

Hagan Bayley is the Founder of, a Director of, a share-holder of and a consultant for OxSyBio, a company engaged in the development of printed tissues and tissue-like materials.

References

- 1.Li T, et al. Fast-moving soft electronic fish. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1602045. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang HW, Sakar MS, Petruska AJ, Pané S, Nelson BJ. Soft micromachines with programmable motility and morphology. Nat Commun. 2016;7:1–10. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu W, Lum GZ, Mastrangeli M, Sitti M. Small-scale soft-bodied robot with multimodal locomotion. Nature. 2018;554:81–85. doi: 10.1038/nature25443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Y, Hauser AW, Bende NP, Kuzyk MG, Hayward RC. Waveguiding Microactuators Based on a Photothermally Responsive Nanocomposite Hydrogel. Adv Funct Mater. 2016;26:5447–5452. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leong TG, et al. Tetherless thermobiochemically actuated microgrippers. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:703–708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807698106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandes R, Gracias DH. Self-folding polymeric containers for encapsulation and delivery of drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rus D, Tolley MT. Design, fabrication and control of soft robots. Nature. 2015;521:467–475. doi: 10.1038/nature14543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breger JC, et al. Self-folding thermo-magnetically responsive soft microgrippers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:3398–3405. doi: 10.1021/am508621s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ionov L. Biomimetic Hydrogel-Based Actuating Systems. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23:4555–4570. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schild HG. Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide): experiment, theory and application. Prog Polym Sci. 1992;17:163–249. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman AS. Stimuli-responsive polymers: Biomedical applications and challenges for clinical translation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashmi B, et al. Developmentally-inspired shrink-wrap polymers for mechanical induction of tissue differentiation. Adv Mater. 2014;26:3253–3257. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim H, et al. Visible Light-Triggered On-Demand Drug Release from Hybrid Hydrogels and its Application in Transdermal Patches. Adv Healthc Mater. 2015;4:2071–2077. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J, Hanna JA, Byun M, Santangelo CD, Hayward RC. Designing responsive buckled surfaces by halftone gel lithography. Science. 2012;335:1201–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1215309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sydney Gladman A, Matsumoto EA, Nuzzo RG, Mahadevan L, Lewis JA. Biomimetic 4D printing. Nat Mater. 2016;15:413–418. doi: 10.1038/nmat4544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cangialosi A, et al. DNA sequence–directed shape change of photopatterned hydrogels via high-degree swelling. Science. 2017;357:1126–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang YS, Khademhosseini A. Advances in engineering hydrogels. Science. 2017;356 doi: 10.1126/science.aaf3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Booth MJ, Restrepo Schild V, Downs FG, Bayley H. Functional aqueous droplet networks. Mol Biosyst. 2017;13:1658–1691. doi: 10.1039/c7mb00192d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham AD, et al. High-Resolution Patterned Cellular Constructs by Droplet-Based 3D Printing. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7004. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06358-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sapra KT, Bayley H. Lipid-coated hydrogel shapes as components of electrical circuits and mechanical devices. Sci Rep. 2012;2 doi: 10.1038/srep00848. 848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Booth MJ, Schild VR, Graham AD, Olof SN, Bayley H. Light-activated communication in synthetic tissues. Sci Adv. 2016;2:e1600056–e1600056. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Booth MJ, Restrepo Schild V, Box SJ, Bayley H. Light-patterning of synthetic tissues with single droplet resolution. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09394-9. 9315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holden MA, Needham D, Bayley H. Functional bionetworks from nanoliter water droplets. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:8650–8655. doi: 10.1021/ja072292a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maglia G, et al. Droplet networks with incorporated protein diodes show collective properties. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:437–440. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villar G, Graham AD, Bayley H. A Tissue Like Printed Material. Science. 2013;340:48–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1229495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villar G, Heron AJ, Bayley H. Formation of droplet networks that function in aqueous environments. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:803–808. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wauer T, et al. Construction and manipulation of functional three-dimensional droplet networks. ACS Nano. 2014;8:771–779. doi: 10.1021/nn405433y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim S, Lee K, Cha C. Refined control of thermoresponsive swelling/deswelling and drug release properties of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) hydrogels using hydrophilic polymer crosslinkers. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2016;27:1698–1711. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2016.1230933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hauser AW, Evans AA, Na JH, Hayward RC. Photothermally reprogrammable buckling of nanocomposite gel sheets. Angew Chemie - Int Ed. 2015;54:5434–5437. doi: 10.1002/anie.201412160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutton A, et al. Photothermally triggered actuation of hybrid materials as a new platform for in vitro cell manipulation. Nat Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14700. 14700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shibayama M, Tanaka T. Volume phase transition and related phenomena of polymer gels. In: Dušek K, editor. Responsive Gels: Volume Transitions I. Advances in Polymer Science. Vol. 109 Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elani Y, Demello AJ, Niu X, Ces O. Novel technologies for the formation of 2-D and 3-D droplet interface bilayer networks. Lab Chip. 2012;12:3514–3520. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40287d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Challita EJ, Najem JS, Monroe R, Leo DJ, Freeman EC. Encapsulating networks of droplet interface bilayers in a thermoreversible organogel. Sci Rep. 2018;8 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24720-5. 6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.