Abstract

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a leading cause of preventable death in the US, however existing treatments are ineffective and produce aversive side effects such as nausea and fatigue. One potential therapeutic for AUD is the α3β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) antagonist 18-Methoxycoronaridine (18-MC). Prior work has shown that 18-MC reduces ethanol consumption in rodent models. The present study sought to further examine the therapeutic potential of 18-MC by testing its effects on nonconsummatory behaviors. We examined two behavioral measures: ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation, which measures euphoric properties of the drug, and the expression of locomotor sensitization which models neuroadaptations in response to repeated exposure. We tested dose-dependent effects of 18-MC (0, 10, 20 and 30 mg/kg) administration on ethanol stimulation and locomotor sensitization in female and male DBA/2J mice. 18-MC had no effect on acute ethanol-induced stimulation, but the highest dose (30 mg/kg) significantly decreased the expression of locomotor sensitization. Our results support the involvement of α3β4 nAChR in the expression of ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization and suggest that 18-MC may be a therapeutic for AUD.

Keywords: Ethanol, Locomotor sensitization, 18-Methoxycoronaridine, Locomotor stimulation

Introduction

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) affects 14.5 million adults in the United States according to the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Among those diagnosed with AUD, only 495,000 reported receiving treatment in the past year (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018). Possible deterrents for individuals seeking treatment are that the three FDA-approved medications for AUD are known to have low effectiveness and produce aversive side effects such as nausea and fatigue (Kim, Hack, Ahn, & Kim, 2018). Thus, research examining novel treatments with a higher therapeutic index is needed.

The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) system has emerged as a potential therapeutic target for alcoholism (Chatterjee & Bartlett, 2010). There are currently two FDA approved medications that act at nAChR: mecamylamine (Inversine®) and varenicline (Chantix®). Studies examining the nonspecific nAChR antagonist mecamylamine have observed positive effects for some alcohol behaviors including ratings of stimulation, but there has been limited evidence to suggest it will decrease consumption in clinical populations (Blomqvist, Hernandez-Avila, Van Kirk, Rose, & Kranzler, 2002; Chi & de Wit, 2003; Petrakis et al., 2018; Young, Mahler, Chi, & de Wit, 2005). These data are in contrast to work in animal models where mecamylamine decreases ethanol intake (Farook, Lewis, Gaddis, Littleton, & Barron, 2009; Ford et al., 2009; Hendrickson, Zhao-Shea, & Tapper, 2009). For varenicline, a α4β2 nAChR partial agonist, results have been more promising and suggest that it can decrease consumption in both humans and rodents (Erwin & Slaton, 2014; Kamens, Andersen, & Picciotto, 2010; O’Malley et al., 2018; Steensland, Simms, Holgate, Richards, & Bartlett, 2007). However, adverse side effects remain a concern for both of these drugs (Drovandi, Chen, & Glass, 2016; Shytle, Penny, Silver, Goldman, & Sanberg, 2002). These findings have prompted exploration into other nAChR-active drugs that may treat AUD with less side effects.

Human genetic studies have shown that polymorphisms in genes encoding the α5, α3, and β4 nAChR subunits are associated with several alcohol traits including dependence (Sherva et al., 2010), response to alcohol (Choquet et al., 2013), and onset of use (Schlaepfer et al., 2008). These results suggest that nAChR containing these subunits may be an important target for future drug development. One promising drug that targets nAChR is 18-methoxycoronaridine (18-MC). 18-MC is an α3β4 nAChR antagonist that reduces ethanol intake in male and female rodents without altering ethanol metabolism, tastant consumption, or ethanol-induced sedation (Miller, Ruggery, & Kamens, 2019; Rezvani et al., 2016, 1997). These findings suggest that 18-MC may specifically reduce ethanol consumption and that further research on its therapeutic potential should be conducted.

Ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation and sensitization are two nonconsummatory behaviors that may influence drug consumption. The initial stimulant properties of a drug may be an important indicator for drug abuse (Gabbay, 2005). For example, a heightened response to alcohol corresponds to a higher risk for alcohol misuse in humans (Holdstock, King, & de Wit, 2000; King, de Wit, McNamara, & Cao, 2011; King, McNamara, Hasin, & Cao, 2014). When alcohol is administered repeatedly, sensitization develops, such that the same dose of ethanol progressively elicits a greater locomotor response. The neuroadaptations thought to underlie sensitization are akin to the mechanisms underlying drug dependence and relapse (Steketee & Kalivas, 2011). Therefore, drugs that alter ethanol stimulation or sensitization may have therapeutic potential in a clinical setting.

Method

Animals

Adult female and male DBA/2J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) arrived at 6–7 weeks of age and were housed 2–4 per standard cage with access to rodent chow (Lab Rodent Diet 5001, PMI Nutrition International, Inc., Brentwood, Missouri) and water ad libitum. DBA/2J mice were selected for these experiments because they exhibit robust ethanol-induced stimulation and sensitization (Gubner, McKinnon, & Phillips, 2014; Phillips, Dickinson, & Burkhart-Kasch, 1994; Rose, Calipari, Mathews, & Jones, 2013). Mice were left undisturbed to acclimate to our vivarium on a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700) for at least one week prior to testing. On experimental days, animals were transported to the behavior room and allowed to habituate for at least 45 min. Testing occurred between 0900 and 1300. All procedures were approved by The Pennsylvania State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drugs

For injections, ethanol (20% v/v; 200 proof; Koptec) and 18-MC ((-)-18-Methoxycoronaridine Hydrochloride; Orbiter Research, LCC) were diluted in physiological saline (0.9% NaCl; Baxter) and administered into the intraperitoneal (i.p.) cavity. 18-MC doses and pretreatment times were based on published work (Glick, Maisonneuve, & Szumlinksi, 2000; Miller et al., 2019).

Locomotor Activity Apparatus

Locomotor activity was monitored as horizontal distance traveled in eight Superflex chambers (16”x16”x12”; length x width x height) and analyzed using the Fusion 6.4 software system (Omnitech Electronics, Inc., Columbus, Ohio). In the chambers, activity is assessed through 8 pairs of photocell beams placed on both the horizontal X and Y planes. These beams are located 2 cm above the chamber floor and interruption of these beams are converted into locomotor activity (cm).

Ethanol-induced Locomotor Stimulation

Female and male DBA/2J mice (n=128) were assessed for the effects of 18-MC on ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation following a 1-day paradigm (Kamens & Phillips, 2008). Briefly, mice received a pretreatment of saline or 18-MC (10, 20, or 30 mg/kg; N=6–10/pretreatment/treatment/sex) and were placed into individual holding cages 30 min prior to receiving treatment with saline or ethanol (2 g/kg) (Dudek, Phillips, & Hahn, 1991). Following treatment, mice were immediately placed into the locomotor chambers. Locomotor activity (cm) was recorded for 15 min in 5-min epochs. The experiment was split into two passes (n=64/pass). Mice were counterbalanced across passes. Further mice were assigned to the 8 locomotor test chambers with sex, pretreatment, and treatment represented in each.

Expression of Ethanol-induced Locomotor Sensitization

Female and male DBA/2J mice (n=99) were examined for the effects of 18-MC on expression of ethanol sensitization following a 14-day paradigm depicted in Table 1 (Gubner et al., 2014). Mice received a pretreatment of saline or 18-MC (10, 20, or 30 mg/kg; N=9–10/group/sex) and were placed into individual holding cages for 30 min prior to treatment with saline or ethanol (2 g/kg) (Gubner et al., 2014; Kamens et al., 2006; Phillips, Lessov, Harland, & Mitchell, 1996). On days 1 and 2, all mice received saline pretreatment and treatment to habituate to the injections and test environment. On days 3–12, all mice received saline pretreatment and the chronic drug (CD) or chronic saline (CS) treatment groups received repeated injections of ethanol (2 g/kg) or saline, respectively. This time period corresponded to the development of behavioral sensitization. On day 13, all mice received a saline or 18-MC pretreatment and ethanol treatment to test the expression of sensitization between groups. On day 14, all mice received a saline pretreatment and treatment to determine any drug carry over effects. Locomotor activity was monitored immediately after treatment on days 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, 13, and 14. On days 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, and 11 mice were returned to their home cage after treatment. On each day locomotor activity (cm) was recorded for 15 min in 5-min epochs. Mice were tested in 2 passes in the 8 locomotor chambers described above. Across passes and chambers mice were counterbalanced based on sex and treatment condition.

Table 1.

Experimental groups and procedures for examining the effect of 18-MC on the expression of ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization.

| Experimental Group | D1&2 | D3 | D4&5 | D6 | D7&8 | D9 | D10&11 | D12 | D13 | D14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAL-CS | SAL, SAL | SAL, SAL | SAL, SAL | SAL, SAL | SAL, SAL | SAL, SAL | SAL, SAL | SAL, SAL | SAL, E2 | SAL, SAL |

| 18-MC–CD (4 groups: 0, 10, 20, and 30 mg/kg) + E2) | SAL, SAL | SAL, E2 | SAL, E2 | SAL, E2 | SAL, E2 | SAL, E2 | SAL, E2 | SAL, E2 | 18-MC, E2 | SAL, SAL |

| Activity test | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

SAL, saline; CS, chronic saline; CD, chronic drug; E2, ethanol.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS. Results from the ethanol stimulation study were analyzed with a factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data from the sensitization study were first analyzed with a repeated-measures ANOVA including locomotor activity on each test day. For analyses of the sensitization experiment we used the composite drug treatment (18-MC plus ethanol group) as a factor because our study did not include all possible 18-MC treated CS groups for a full factorial design. The development of sensitization was evaluated as the day 12 ethanol response minus the response to the first exposure on day 3. To examine the effects of 18-MC on sensitization, we utilized both between groups (day 13) and within groups analyses (day 13 - day 12). Independent variables included sex, day, pretreatment, treatment, and composite drug treatment where appropriate. Tukey’s post hoc analyses were performed. α < 0.05 was considered significant for all statistical analyses.

Results

Ethanol-induced Locomotor Stimulation

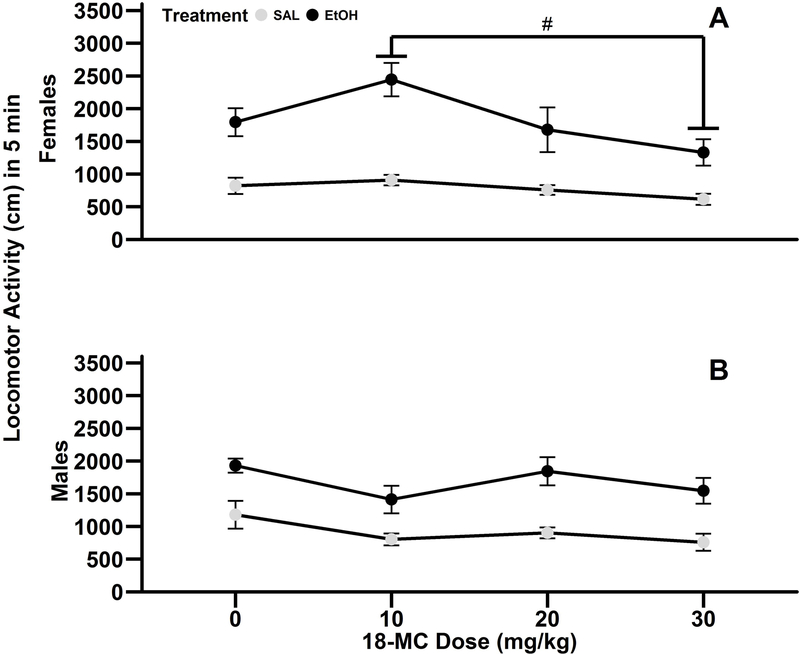

Treatment with 18-MC did not alter ethanol-induced stimulation or general locomotor activity in female and male DBA/2J mice (Fig. 1). Data from the first 5 min of the 15 min test are presented because ethanol stimulation was most robust at this time, which is consistent with prior work in this strain (Gubner et al., 2014; Shen, Harland, Crabbe, & Phillips, 1995). There was a significant main effect of treatment (F1,112=99.2; p<0.001), pretreatment (F3,112=3.6; p<0.05), and significant interaction of 18-MC pretreatment x sex (F3,112=4.2), so further analyses were conducted separately in females and males. Within female mice, ethanol treatment resulted in significant locomotor stimulation compared to saline treatment (main effect of treatment: F1,56=56.6; p<0.001; mean ± SEM: saline=774.3 ± 48.4 cm ; ethanol=1811.3 ± 142.9 cm). Further, female mice pretreated with 30 mg/kg 18-MC were less active than mice pretreated with 10 mg/kg 18-MC (main effect of pretreatment: F3,56=4.5; p<0.01; post hoc p<0.01), but the 18-MC pretreatment x treatment interaction was not significant. Similar to results in female mice, male mice treated with ethanol exhibited enhanced locomotor activity compared to saline treated mice (main effect of treatment: F1,56=42.8; p<0.001; saline=901.1 ± 73.2 cm; ethanol=1655.3 ± 99.2 cm). There was also a significant main effect of 18-MC pretreatment (F3,56=3.2; p<0.05), however post hoc analyses only revealed a trend for mice pretreated with 30 mg/kg 18-MC to be less active than saline controls (p=0.06).

Fig. 1.

18-MC did not alter ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation in male and female DBA/2J mice. Data (mean ± SEM) represent the first 5 min of locomotor activity in adult female (A) and male (B) DBA/2J mice. N=6–10/pretreatment/treatment/sex. #post hoc difference observed from the main effect of pretreatment; p<0.01.

Expression of Ethanol-induced Locomotor Sensitization

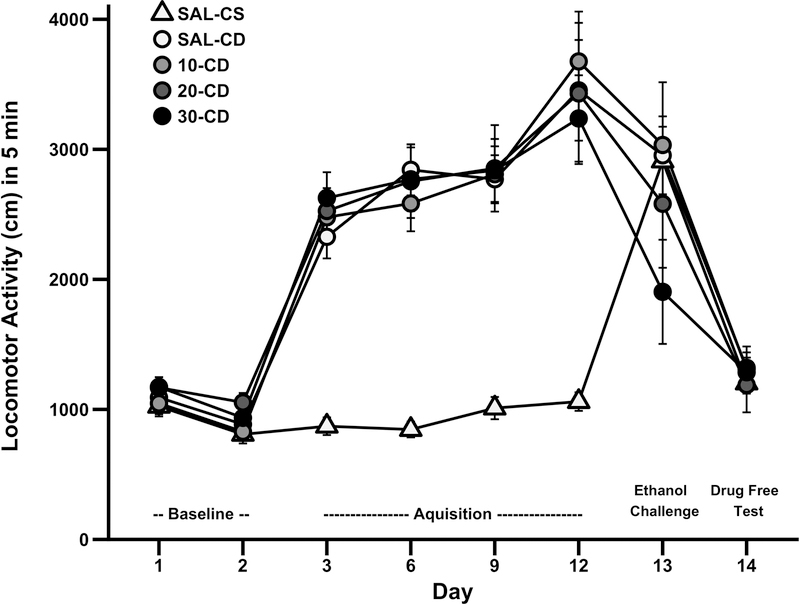

Daily locomotor activity data from the sensitization study is presented in Fig. 2. In the repeated measures ANOVA that included all test days, there was a significant main effect of day (F7,623=123.6; p<0.001) and composite drug treatment (F4,89=12.7; p<0.001). Further, there were significant day x sex (F7,623=5.5; p<0.001) and day x composite drug treatment interactions (F28,623=9.0; p<0.001). These results suggest that the pattern of activity across days is dependent upon drug treatment, expected based on the experimental design. Consistent with prior studies utilizing a similar design, we then focused our analysis on measures of sensitization (Gubner et al., 2014). To test for the development of behavioral sensitization we examine the difference in locomotor response on day 12 after chronic ethanol treatment minus the day 3 response after initial ethanol exposure (Gubner et al., 2014). There was a significant main effect of sex (F1,95=5.6; p<0.05), so males and females were analyzed independently. Exposure to repeated ethanol resulted in robust locomotor sensitization in male (main effect of treatment F1,47=4.3; p<0.05; CS=266.4 ± 132.7 cm; CD=970.2 ± 175.9 cm), but not female DBA/2J mice.

Fig. 2.

Locomotor activity across test days for the ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization study. Data (mean ± SEM) represent the first 5 min of locomotor activity in adult DBA/2J mice. N=19–20/group. SAL-CS, saline-chronic saline; SAL-CD, saline-chronic drug; 10-CD, 10mg/kg 18-MC-chronic drug; 20-CD, 20 mg/kg 18-MC-chronic drug; 30-CD, 30mg/kg 18-MC-chronic drug.

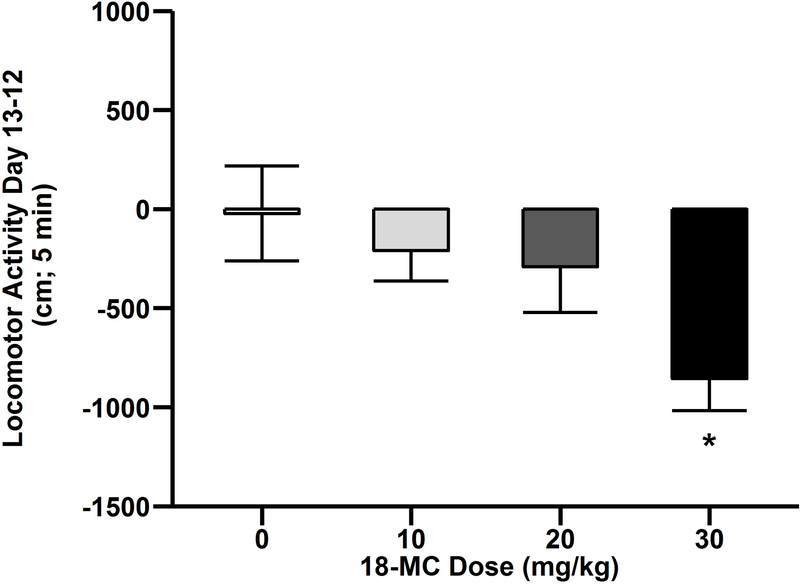

Since the goal of the experiment was to examine effects of 18-MC on the expression of sensitization, we performed between and within groups analyses. First, to determine the effect of 18-MC on expression of sensitization between groups, the day 13 response was examined. On day 13 there were no significant effects or interactions. Second, we examined the effects of 18-MC on ethanol-induced sensitization within groups. For this analysis, the day 12 sensitized response was subtracted from the day 13 response following 18-MC administration within only the CD groups (Fig. 3). There was a main effect of 18-MC pretreatment (F3,72=3.3; p<0.05) such that mice pretreated with 30 mg/kg 18-MC exhibited less sensitization relative to saline treated mice (post hoc p<0.05). Importantly, neither the main effect of sex or interaction of sex and 18-MC dose were significant therefore data presented Fig. 2 and 3 are collapsed on this factor. On day 14 there were no significant effects or interactions, so there were no lasting effects of 18-MC or chronic ethanol treatment on general locomotor activity.

Fig. 3.

18-MC reduced expression of ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization. Data (mean ± SEM) represent day 13 - day 12 difference in locomotor activity among CD groups in male and female DBA/2J mice. N=19–20/group.*significantly different from saline; p<0.05.

Discussion

The present study examined the effects of 18-MC, an α3β4 nAChR antagonist, on two nonconsummatory ethanol traits which may underlie the reduction in drug consumption previously reported (Miller et al., 2019; Rezvani et al., 2016, 1997). Here 18-MC reduces the expression of ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization in female and male DBA/2J mice when tested with a within groups analysis. 18-MC did not alter ethanol-induced stimulation or cause reductions in basal locomotor activity. Thus, α3β4 nAChR appear to be specifically involved in the expression of ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization, but not in acute stimulation.

Utilizing a within subject analysis, we observed that a high (30 mg/kg) dose of 18-MC decreased the expression of ethanol-induced sensitization in female and male DBA/2J mice. We did not observe a significant effect of 18-MC pretreatment in the between subject analysis, which may be due to high intra-strain variation in locomotor responses to ethanol (Masur & dos Santos, 1988). Alternatively, we may have been underpowered to detect this effect with the between-groups analysis, which would be consistent with the known power advantage of a within-subject design (Keppel, 1991).

It is interesting that we observed an effect of 18-MC on ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization that was independent of sex, but our paradigm produced sensitization in only male mice. These data suggest that although we did not see an increase in locomotor activity with repeated ethanol injections in female mice, neural adaptations that are modulated by nAChR were still occurring. Visual examination of the between-groups day 13 response revealed a similar pattern to the within-groups analysis (Fig 3). Here, CD mice pretreated with 30 mg/kg 18-MC (mean=2059.19 ± 232.11 cm) appear to have reduced activity compared to saline controls (mean=2880.75 ± 174.38 cm). Overall, these data provide moderate support that 18-MC decreases sensitization. Reducing the expression of sensitization is clinically relevant because treatment for alcoholism will occur after chronic drug use.

Previous work suggests that the anti-addictive properties of 18-MC are mediated by antagonism of α3β4 nAChR (Glick, Maisonneuve, Kitchen, & Fleck, 2002; Pace et al., 2004), although low affinity for opioid and serotonin receptors has been reported (Glick & Maisonneuve, 2000; Glick et al., 2000). To our knowledge this is the first study to examine the role of α3β4 nAChR in the expression of ethanol locomotor sensitization, but prior work has examined other nAChR (Bhutada et al., 2010). Consistent with our findings, the nonspecific nAChR antagonist mecamylamine attenuated expression of ethanol-induced sensitization in inbred Swiss male mice using a similar paradigm (Bhutada et al., 2010). It is possible that the reduction observed following mecamylamine administration is due to α3β4 nAChR, as prior studies have shown that mecamylamine is most potent at inhibiting human α3β4 receptors (Papke, Sanberg, & Shytle, 2001). Taken together, our results support a specific role of α3β4 nAChR in the expression of ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization.

The development of drug-induced locomotor sensitization is related to the neural adaptations observed following chronic drug use that are akin to dependence (Phillips, Pastor, Scibelli, Reed, & Tarragón, 2011) and highly correlated with relapse (Fish, DeBold, & Miczek, 2002). Prior studies have shown that 30 mg/kg 18-MC reduces acute ethanol intake in C57BL/6J mice (Miller et al., 2019). Further, 10–40 mg/kg 18-MC decreases ethanol consumption in a model of chronic ethanol consumption in rats (Rezvani et al., 2016, 1997). This finding is notable because high affinity α3β4 nAChR partial agonists reduce ethanol intake in rats following chronic (11 weeks) ethanol exposure (Chatterjee et al., 2011). Our findings with ethanol sensitization are in line with these data that show an attenuated ethanol response by 18-MC after chronic ethanol exposure.

The mechanisms underlying the expression of locomotor sensitization involve changes in dopaminergic transmission in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and ventral tegmental area (VTA) (Cador, Bjijou, & Stinus, 1995). α3β4 nAChR are expressed in multiple brain regions in the rodent nervous system including in the ventral midbrain (including the VTA), hippocampus, medial habenula, pineal gland, cerebellum, locus coeruleus, and interpeduncular nucleus, (Gotti, Zoli, & Clementi, 2006). The medial habenula receives direct inputs from the NAc and VTA and send outputs to the VTA, so 18-MC may be altering dopaminergic transmission through this brain region (Cuello, Emson, Paxinos, & Jessell, 1978; McLaughlin, Dani, & De Biasi, 2017; Phillipson & Pycock, 1982; Sutherland, 1982). Prior work suggests that the anti-addictive properties of 18-MC are mediated through actions at α3β4 nAChR in the medial habenula because direct infusions of 18-MC into this brain region decreases morphine, methamphetamine, and nicotine self-administration (Glick et al., 2002; Glick, Ramirez, Livi, & Maisonneuve, 2006; Glick, Sell, & Maisonneuve, 2008; Glick, Sell, Mccallum, & Maisonneuve, 2011; Pace et al., 2004; Rezvani et al., 2016). We hypothesize that 18-MC may alter the expression of ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization through actions at α3β4 nAChR in the medial habenula, but more work is necessary to test this.

In contrast to effects on sensitization, 18-MC did not alter ethanol-induced stimulation or basal locomotor activity in female and male DBA/2J mice relative to controls. Ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation is associated with the feelings of euphoria and physiologically corresponds to elevated dopamine levels (Carlsson, Engel, Strombom, Svensson, & Waldeck, 1974). To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the involvement of α3β4 nAChR in ethanol-induced stimulation, but prior work has examined the role of other nAChR in this behavior. For example, the nonspecific nAChR antagonist mecamylamine reduces ethanol-induced stimulation, suggesting these receptors influence this trait (Bhutada et al., 2010; Kamens & Phillips, 2008). One type of nAChR previously linked to ethanol stimulation is α4β2 receptors, but results here are mixed. For example, the α4β2 nAChR partial agonist varenicline reduces stimulation, but the α4β2 nAChR antagonist dihydro-b-erythoidine had no effect on this behavior (Gubner et al., 2014; Kamens & Phillips, 2008). In terms of α3β4 receptors, there are also mixed findings. Prior work in genetically engineered mice suggests a possible role of the α3 subunit in the acute locomotor response to ethanol. Specifically, Chrna3 heterozygous (+/−) mice exhibit reduced locomotor sedation in response to an acute injection of ethanol (Kamens et al., 2009). However, these genetically engineered mice were on a C57BL/6J background, whereas here we tested the acute response in DBA/2J mice. Therefore, it is difficult to draw direct comparisons because these two strains vary greatly in response to acute administration of ethanol (Rose et al., 2013). The current data provide no support for a role of α3β4 nAChR in ethanol stimulation, but this could be dependent on strain tested.

Overall, our present findings suggest that 18-MC may have therapeutic potential for AUD. We demonstrated here that 18-MC attenuates the expression of ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization. In contrast to effects on sensitization, 18-MC did not alter ethanol-induced stimulation or basal locomotor activity, therefore the effects observed appear to be specific to the expression of ethanol-induced sensitization. Further, our results support the involvement of α3β4 nAChR in expression of ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization. Currently 18-MC is in clinical trials for a non-drug abuse trait, but if tolerated in humans it may be an effective treatment for AUD.

Public Significant Statement:

The present study found that 18-MC specifically reduced expression of ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization, which is a behavioral measure that models neural adaptations to chronic alcohol use and thought to reflect dependence. These results support the involvement of α3β4 nAChR in ethanol sensitization and support 18-MC as a potential therapeutic for individuals suffering from AUD.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by The Broadhurst Career Development Professorship for the study of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (HMK), NIDA P50 DA039838 (Linda Collins), and the Penn State Social Science Research Institute (HMK).

We would like to acknowledge Colton Ruggery, Kylie Stuhltrager, and Aidan Peat for their technical assistance on this project.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Bhutada PS, Mundhada YR, Bansod KU, Dixit PV, Umathe SN, & Mundhada DR (2010). Inhibitory influence of mecamylamine on the development and the expression of ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization in mice. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 96(3), 266–273. 10.1016/J.PBB.2010.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist O, Hernandez-Avila CA, Van Kirk J, Rose JE, & Kranzler HR (2002). Mecamylamine modifies the pharmacokinetics and reinforcing effects of alcohol. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 26(3), 326–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cador M, Bjijou Y, & Stinus L (1995). Evidence of a complete independence of the neurobiological substrates for the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine. Neuroscience, 65(2), 385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A, Engel J, Strombom U, Svensson TH, & Waldeck B (1974). Suppression by dopamine-agonists of the ethanol-induced stimulation of locomotor activity and brain dopamine synthesis. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology, 283(2), 117–128. 10.1007/BF00501138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee & Bartlett SE (2010). Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as pharmacotherapeutic targets for the treatment of alcohol use disorders. CNS & Neurological Disorders Drug Targets, 9(1), 60–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Coe JW, Hurst RS, … Bartlett SE (2011). Partial Agonists of the α3β4* Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Reduce Ethanol Consumption and Seeking in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology, 36, 603–615. 10.1038/npp.2010.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H, & de Wit H (2003). Mecamylamine Attenuates the Subjective Stimulant-Like Effects of Alcohol in Social Drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 27(5), 780–786. 10.1097/01.ALC.0000065435.12068.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet H, Joslyn G, Lee A, Kasberger J, Robertson M, Brush G, … Jorgenson E (2013). Examination of Rare Missense Variants in the CHRNA5-A3-B4 Gene Cluster to Level of Response to Alcohol in the San Diego Sibling Pair Study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(8), 1311–1316. 10.1111/acer.12099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello AC, Emson PC, Paxinos G, & Jessell T (1978). Substance P containing and cholinergic projections from the habenula. Brain Research, 149(2), 413–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drovandi AD, Chen CC, & Glass BD (2016). Adverse Effects Cause Varenicline Discontinuation: A Meta-Analysis. Current Drug Safety, 11(1), 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek BC, Phillips TJ, & Hahn ME (1991). Genetic analyses of the biphasic nature of the alcohol dose-response curve. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 15(2), 262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin BL, & Slaton RM (2014). Varenicline in the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorders. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 48(11), 1445–1455. 10.1177/1060028014545806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farook JM, Lewis B, Gaddis JG, Littleton JM, & Barron S (2009). Effects of Mecamylamine on Alcohol Consumption and Preference in Male C57BL/6J Mice. Pharmacology, 83(6), 379–384. 10.1159/000219488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish E, DeBold J, & Miczek K (2002). Repeated alcohol: behavioral sensitization and alcohol-heightened aggression in mice. Psychopharmacology, 160(1), 39–48. 10.1007/s00213-001-0934-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford MM, Fretwell AM, Nickel JD, Mark GP, Strong MN, Yoneyama N, & Finn DA (2009). The influence of mecamylamine on ethanol and sucrose self-administration. Neuropharmacology, 57(3), 250–258. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay FH (2005). Family History of Alcoholism and Response to Amphetamine: Sex Differences in the Effect of Risk. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 29(5), 773–780. 10.1097/01.ALC.0000164380.16043.4F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick & Maisonneuve IM (2000). Development of novel medications for drug addiction. The legacy of an African shrub. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 909, 88–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick, Maisonneuve IM, & Szumlinksi KK (2000). 18-Methoxycoronaridine (18-MC) and Ibogaine: Comparison of Antiaddictive Efficacy, Toxicity, and Mechanisms of Action. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 914(1), 369–386. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SD, Maisonneuve IM, Kitchen BA, & Fleck MW (2002). Antagonism of alpha 3 beta 4 nicotinic receptors as a strategy to reduce opioid and stimulant self-administration. European Journal of Pharmacology, 438(1–2), 99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SD, Ramirez RL, Livi JM, & Maisonneuve IM (2006). 18-Methoxycoronaridine acts in the medial habenula and/or interpeduncular nucleus to decrease morphine self-administration in rats. European Journal of Pharmacology, 537(1–3), 94–98. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick, Sell EM, & Maisonneuve IM (2008). Brain regions mediating α3β4 nicotinic antagonist effects of 18-MC on methamphetamine and sucrose self-administration. European Journal of Pharmacology, 599, 91–95. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.09.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick, Sell EM, Mccallum SE, & Maisonneuve IM (2011). Brain regions mediating α3β4 nicotinic antagonist effects of 18-MC on nicotine self-administration 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gotti C, Zoli M, & Clementi F (2006). Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: native subtypes and their relevance. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 27(9), 482–491. 10.1016/j.tips.2006.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubner NR, McKinnon CS, & Phillips TJ (2014). Effects of varenicline on ethanol-induced conditioned place preference, locomotor stimulation, and sensitization. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 38(12), 3033–3042. 10.1111/acer.12588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson LM, Zhao-Shea R, & Tapper AR (2009). Modulation of ethanol drinking-in-the-dark by mecamylamine and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists in C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology, 204(4), 563–572. 10.1007/s00213-009-1488-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdstock L, King AC, & de Wit H (2000). Subjective and objective responses to ethanol in moderate/heavy and light social drinkers. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(6), 789–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens, Andersen J, & Picciotto MR (2010). The Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Partial Agonist Varenicline Increases the Ataxic and Sedative-Hypnotic Effects of Acute Ethanol Administration in C57BL/6J Mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(12), 2053–2060. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01301.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Burkhart-Kasch S, McKinnon CS, Li N, Reed C, & Phillips TJ (2006). Ethanol-related traits in mice selectively bred for differential sensitivity to methamphetamine-induced activation. Behavioral Neuroscience, 120(6), 1356–1366. 10.1037/0735-7044.120.6.1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens, McKinnon CS, Li N, Helms ML, Belknap JK, & Phillips TJ (2009). The alpha 3 subunit gene of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is a candidate gene for ethanol stimulation. Genes, Brain, and Behavior, 8(6), 600–609. 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00444.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens, & Phillips TJ (2008). A role for neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in ethanol-induced stimulation, but not cocaine- or methamphetamine-induced stimulation. Psychopharmacology, 196(3), 377–387. 10.1007/s00213-007-0969-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel G (1991). Design and analysis: a researcher’s handbook (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Hack LM, Ahn ES, & Kim J (2018). Practical outpatient pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder. Drugs in Context, 7, 212308. 10.7573/dic.212308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, de Wit H, McNamara PJ, & Cao D (2011). Rewarding, Stimulant, and Sedative Alcohol Responses and Relationship to Future Binge Drinking. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(4), 389. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, McNamara PJ, Hasin DS, & Cao D (2014). Alcohol Challenge Responses Predict Future Alcohol Use Disorder Symptoms: A 6-Year Prospective Study. Biological Psychiatry, 75(10), 798. 10.1016/J.BIOPSYCH.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masur J, & dos Santos HM (1988). Response variability of ethanol-induced locomotor activation in mice. Psychopharmacology, 96(4), 547–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin I, Dani JA, & De Biasi M (2017). The medial habenula and IPN regulate mood and addiction. Journal of Neurochemistry 10.1111/jnc.14008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Miller CNCN, Ruggery C, & Kamens HMHM (2019). The α3β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist 18-Methoxycoronaridine decreases binge-like ethanol consumption in adult C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol, 79, 1–6. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Zweben A, Fucito LM, Wu R, Piepmeier ME, Ockert DM, … Gueorguieva R (2018). Effect of Varenicline Combined With Medical Management on Alcohol Use Disorder With Comorbid Cigarette Smoking. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(2), 129. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace CJ, Glick SD, Maisonneuve IM, He L-W, Jokiel PA, Kuehne ME, & Fleck MW (2004). Novel iboga alkaloid congeners block nicotinic receptors and reduce drug self-administration. European Journal of Pharmacology, 492(2–3), 159–167. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Sanberg PR, & Shytle RD (2001). Analysis of mecamylamine stereoisomers on human nicotinic receptor subtypes. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 297(2), 646–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrakis IL, Ralevski E, Gueorguieva R, O’Malley SS, Arias A, Sevarino KA, … Krystal JH (2018). Mecamylamine treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 113(1), 6–14. 10.1111/add.13943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Dickinson S, & Burkhart-Kasch S (1994). Behavioral sensitization to drug stimulant effects in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J inbred mice. Behavioral Neuroscience, 108(4), 789–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Lessov CN, Harland RD, & Mitchell SR (1996). Evaluation of potential genetic associations between ethanol tolerance and sensitization in BXD/Ty recombinant inbred mice. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 277(2). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TJ, Pastor R, Scibelli AC, Reed C, & Tarragón E (2011). Behavioral Sensitization to Addictive Drugs: Clinical Relevance and Methodological Aspects (pp. 267–305). Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. 10.1007/978-1-60761-883-6_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson OT, & Pycock CJ (1982). Dopamine neurones of the ventral tegmentum project to both medial and lateral habenula. Some implications for habenular function. Experimental Brain Research, 45(1–2), 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani AH, Cauley MC, Slade S, Wells C, Glick S, Rose JE, & Levin ED (2016). Acute oral 18-methoxycoronaridine (18-MC) decreases both alcohol intake and IV nicotine self-administration in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 150–151, 153–157. 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani AH, Overstreet DH, Yang Y, Maisonneuve IM, Bandarage UK, Kuehne ME, & Glick SD (1997). Attenuation of Alcohol Consumption by a Novel Nontoxic Ibogaine Analogue (18-Methoxycoronaridine) in Alcohol-Preferring Rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 58(2), 615–619. 10.1016/S0091-3057(97)10003-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JH, Calipari ES, Mathews TA, & Jones SR (2013). Greater Ethanol-Induced Locomotor Activation in DBA/2J versus C57BL/6J Mice Is Not Predicted by Presynaptic Striatal Dopamine Dynamics. PLoS ONE, 8(12), e83852. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer IR, Hoft NR, Collins AC, Corley RP, Hewitt JK, Hopfer CJ, … Ehringer MA (2008). The CHRNA5/A3/B4 Gene Cluster Variability as an Important Determinant of Early Alcohol and Tobacco Initiation in Young Adults. Biological Psychiatry, 63(11), 1039–1046. 10.1016/J.BIOPSYCH.2007.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen EH, Harland RD, Crabbe JC, & Phillips TJ (1995). Bidirectional selective breeding for ethanol effects on locomotor activity: characterization of FAST and SLOW mice through selection generation 35. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 19(5), 1234–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherva R, Kranzler HR, Yu Y, Logue MW, Poling J, Arias AJ, … Gelernter J (2010). Variation in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes is associated with multiple substance dependence phenotypes. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 35(9), 1921–1931. 10.1038/npp.2010.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shytle RD, Penny E, Silver AA, Goldman J, & Sanberg PR (2002). Mecamylamine (Inversine®): an old antihypertensive with new research directions. Journal of Human Hypertension, 16(7), 453–457. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Richards JK, & Bartlett SE (2007). Varenicline, an 4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, selectively decreases ethanol consumption and seeking. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(30), 12518–12523. 10.1073/pnas.0705368104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee JD, & Kalivas PW (2011). Drug wanting: behavioral sensitization and relapse to drug-seeking behavior. Pharmacological Reviews, 63(2), 348–365. 10.1124/pr.109.001933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Rockville. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland RJ (1982). The dorsal diencephalic conduction system: a review of the anatomy and functions of the habenular complex. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 6(1), 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EM, Mahler S, Chi H, & de Wit H (2005). Mecamylamine and ethanol preference in healthy volunteers. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(1), 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]