Abstract

Background:

We previously developed a computational model to aid clinicians in positioning implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), especially in the case of abnormal anatomies that commonly arise in pediatric cases. We have validated the model clinically on the body surface; however, validation within the volume of the heart is required to establish complete confidence in the model and improve its use in clinical settings.

Objective:

The goal of this study was to use an animal model and thoracic phantom to record the ICD potential field within the heart and on the torso to validate our defibrillation simulation system.

Methods:

We recorded defibrillator shock potentials from an ICD suspended together with an animal heart in a human-shaped torso tank and compared them to simulated values. We also compared the scaled distribution threshold (SDT), an analogue to the defibrillation threshold, from the measured and simulated electric fields within the myocardium.

Results:

ICD potentials recorded on the tank and cardiac surface and within the myocardium agreed well with those predicted by the simulation. A quantitative comparison of the recorded and simulated potentials yielded a mean correlation of 0.94 and a relative error of 19.1 %. The simulation can also predict SDTs similar to those calculated from measured potential fields.

Conclusions:

We found that our simulation could predict potential fields with high correlation to measured values within the heart and on the torso surface. These results support the use of this model for optimization of ICD placements.

Keywords: defibrillation, patient-specific simulation, torso tank, defibrillation simulation, implantable cardioverter defibrillator

1. Introduction

Defibrillation is a mature technology used in hundreds of thousands of patients to treat ventricular fibrillation and other life-threatening arrhythmias,1–3 but it is not without significant risks, including tissue damage from overshock4 and the morbidity of implantation surgery for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs).2 Device manufacturers, physicians, and researchers have proposed improvements to reduce the energy needed to defibrillate a patient, called the defibrillation threshold (DFT), and to minimize the invasiveness of the devices while maintaining patient safety. These improvements include new configurations such as subcutaneous ICDs5–7 and wearable cardioverter-defibrillators.8, 9 Testing the effectiveness of new device developments is essential, yet conducting such tests in animal or clinical experiments can be cost prohibitive or unethical.

Mathematical and computational modeling can facilitate defibrillator development, test new technologies, and guide their use. Such modeling may also reduce the number of patient and animal trials needed to test device configurations. To this end, we have developed a patient-specific simulation pipeline that has been used by researchers and physicians to test device configurations in subject-specific anatomies.10, 11 The pipeline predicts the potential distribution throughout the torso and calculates the DFT based on the critical mass hypothesis. This pipeline has been shown to be generally accurate in predicting DFT and body-surface defibrillation potentials in patients;10, 12 however, to our knowledge, no such published validations have included comprehensive measurements of potentials within the volume of the heart.

Previous studies have compared measured and simulated defibrillation potentials within the heart, but only with very sparse sampling and often over limited regions of the heart.13, 14 Other studies have used electrolytic phantoms to measure cellular potentials during defibrillation using optical techniques,15 yet these studies measured tissue activity before and after defibrillation, i.e., the results of defibrillation, and not the potentials generated by the device. We have carried out many related studies in electrolytic, densely instrumented phantoms shaped like a human torso with an isolated, perfused heart suspended inside, but have also focused on capturing intrinsic cardiac electrical activity rather than defibrillation.16–18 We have modified this preparation to measure defibrillation in a way that offers a unique opportunity to record multichannel signals of defibrillation pulses simultaneously in the myocardium and on the heart and torso surfaces.

In this study, we recorded defibrillator potentials in a human-shaped torso tank phantom containing an isolated animal heart. We were able to capture up to 1024 channels from within the heart using intramural multielectrode needles together with the epicardial and torso surface potentials using metallic contact electrodes. We compared the measured potential fields to those predicted by the simulation pipeline to establish its accuracy. We also computed the electric field strength from both the recorded and simulated potentials and evaluated their similarity based on our own metric: the scaled distribution threshold (SDT), based on the same critical mass assumptions as DFT but localized to the region captured by the intramyocardial measurements. The results of this study establish the torso-tank preparation as a viable experimental model to record potentials at high spatial resolution within the heart with accompanying epicardial and torso measurements. The comparisons of simulated and measured potentials demonstrated qualitative and quantitative similarities and indicated that simulation was generally accurate.

2. Methods

We recorded potentials generated by an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) placed with an isolated freshly harvested animal heart within a torso-shaped electrolytic tank and compared them with simulated potentials generated using our previously described pipeline.11, 12, 19 To record ICD potentials, we modified a previous setup designed to record intrinsic potential distributions in and around a beating heart as it was suspended in a tank filled with electrolyte solution.16–18 This modification allowed us to record potentials generated by the ICD suspended and discharged within the tank (Section A.1, Figure A.1). The recorded signals were processed as described in Section A.2 and the geometries were registered also as described in Section A.3 and shown in Figure A.2 to facilitate comparison to simulated data. The simulated potentials mimicked the experiment by generating values produced by the device using the same geometries and conductivities as used in the experiment (See the Supplement A.4 for details). We compared simulated and recorded potential values with the normalized root mean square error (), relative error (RE), and correlation (ρ); we compared electric field strength values with the scaled distribution threshold (SDT), also described in the expanded description of the methods in the supplemental material (Section A.5).

2.1. Ethics

All experiments were performed with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Utah and conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health publication No. 85–23).

3. Results

Our results first demonstrate the feasibility of using the torso-tank experimental preparation to validate the simulation pipeline. They secondly show high agreement between measured and simulated results with some exceptions, both qualitative and quantitative, for all experiments and recorded shocks. The same agreement was supported by a comparison of the electric field cumulative distribution function between measurements and simulations. The scaled distribution thresholds (SDTs) from measured and simulated electric fields agreed in some experiments but not in others.

3.1. Potential Field Comparison

Comparing the measured peak ICD potentials to values predicted by the simulation pipeline showed high correlation (ρ), low normalized RMS error (), and moderate relative error (RE) as summarized in Table B.1. The ρ ranged from 0.93 to 0.96 with a mean value of 0.94, the ranged from 4.7 to 7.7 % with a mean of 6.1 %, and the RE ranged from 3.7 to 35.9 %. Experiment A showed the biggest differences, with the highest error (RE and ) and lowest ρ. Conversely, experiment D was the most accurate, with the highest ρ, lowest RE by a factor of ∼4, and near lowest (Table B.1). Each experiment demonstrated relatively consistent accuracy across shocks. Table B.1 also shows the comparison between measured and simulated lead impedances. The minimum difference between measured and predicted values was 4 Ω, and the maximum was 28 Ω. The mean difference was 13 Ω.

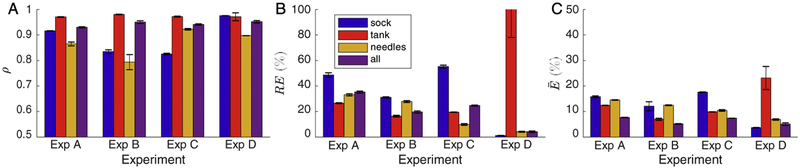

We compared measured and simulated results for each of the recorded subsets separately, i.e., the cardiac surface (sock), tank surface, and cardiac volume (needles). Typical ranges of error for ρ were from 0.79 to 0.98, the RE ranged from 1.2 % to 114 %, and ranged from 3.7 % to 23.2 %. As shown in Figure 1, the accuracy of the predicted potentials varied by recording surface as well as by experiment. The needle potentials showed lower correlations than the other recording subsets for three of the four experiments; however, they never had the highest RE and only had the highest in one experiment. The tank surface showed the highest correlations and lowest for three experiments and the lowest RE for two experiments. Paradoxically, the tank surface recordings for experiment D showed the highest RE and for all surfaces over all experiments, despite the high correlation.

Figure 1:

Mean comparison of the simulated and measured potential fields by measurement domain, i.e., the sock, tank, needles, or all recordings. The metrics shown are the A) correlation (ρ), B) relative error (RE), and C) normalized RMS error (). Error bars represent the standard deviation.

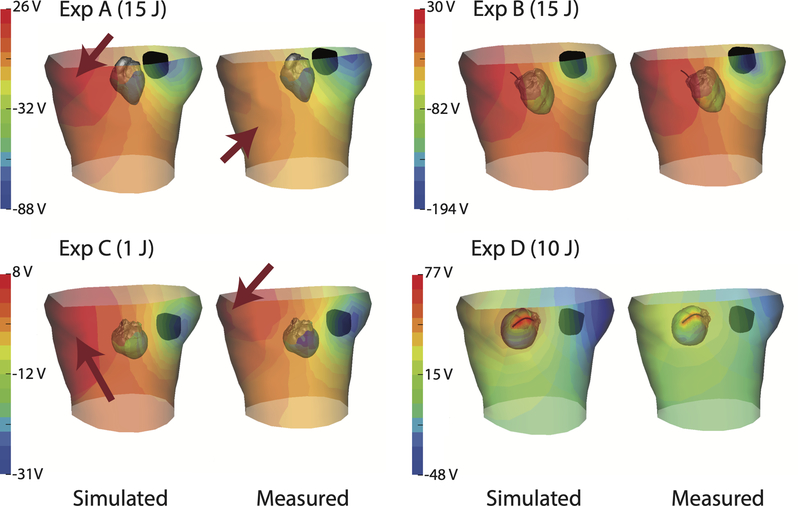

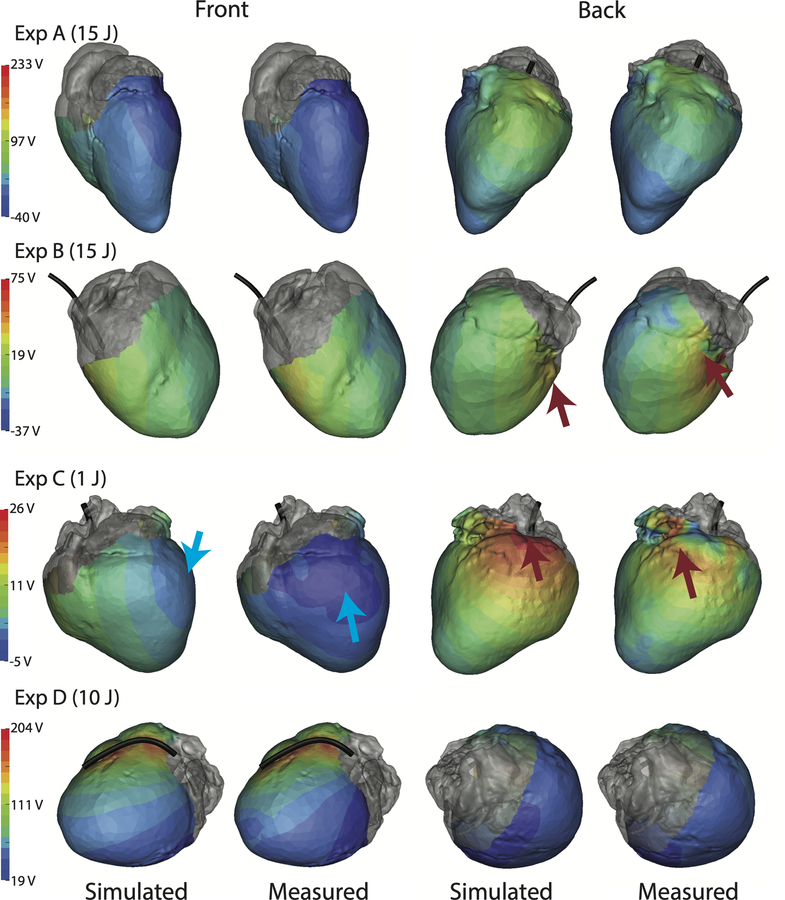

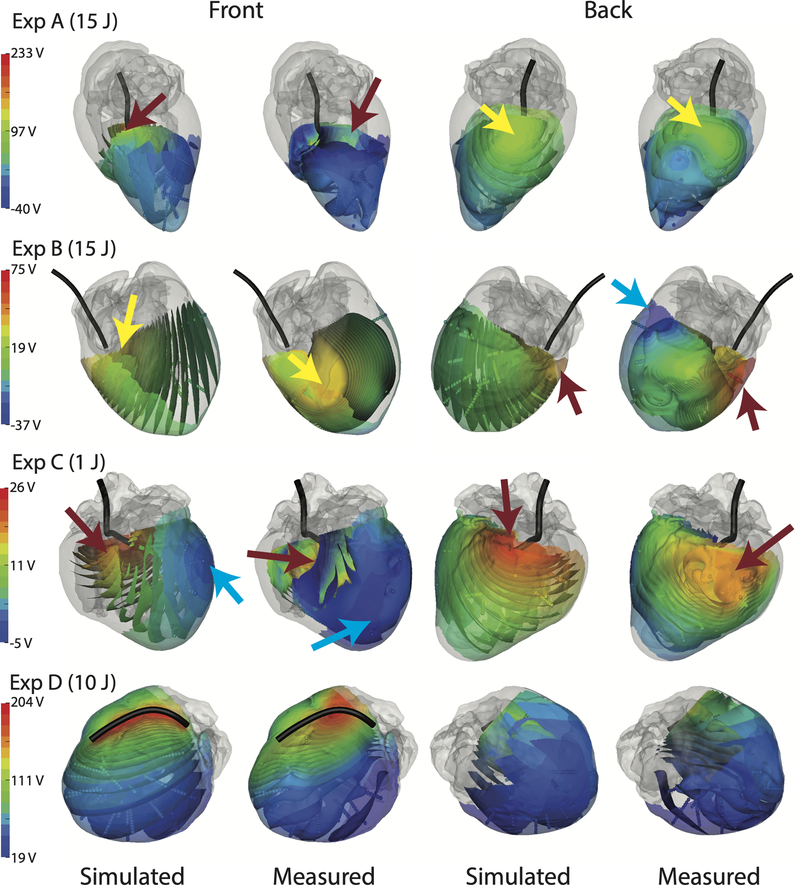

Figures 2, 3, and 4 show the measured potential distributions along with the corresponding simulated potentials for the torso surface, epicardium, and myocardial volume at the peak of a defibrillator pulse. The measured and predicted potential distributions showed a high degree of qualitative agreement in the potential patterns (a finding supported by the strong correlations). Amplitude variations were visible, largely because of scaling differences between simulations and measurements. However, there were shifts in locations of extrema on the tank surface in experiments A and C (Figure 2), the heart surface in experiments B and C (Figure 3), and in the myocardium in experiments A, B, and C (Figure 4). Experiment D showed a difference in the shape of the maximum area observed in the myocardium (Figure 4), which could be caused by undersampling of the region. The measured epicardial surface and myocardial volume potentials in experiments A, B, and C contained local extrema that were not predicted by the simulation (Figures 3 and 4). Some of the local extrema on the epicardial surface, e.g., near the base of the heart, could be attributed to poor electrode contact.

Figure 2:

Spatial comparison of the peak potential fields on the torso tank and the epicardium across all four experiments. ICD generator and coil positions are included (black) together with the epicardial surface. Note the variation in scale of the color maps, which applies to the torso potentials and was customized for each experiment. Arrows (red) indicate extrema locations that differ between simulated and measured data.

Figure 3:

Spatial comparison of the peak potential fields on the epicardial sock for all four experiments. ICD coil position is included (black) as is the output energy of the defibrillator. Each colorbar is customized for the experiment. Arrows indicate extrema locations that differ between simulated and measured data; red arrows are maxima and blue are minima.

Figure 4:

Spatial comparison of the peak potential fields from within the myocardium for all four experiments. ICD coil position is included (black). The visualization uses isosurfaces colored according to the scale bar next to each row, which is customized for each experiment. Arrows indicate extrema locations that differ between simulated and measured data; red arrows are maxima, blue are minima, and yellow are local maxima.

Qualitative comparison of the simulated and measured electric field values through the myocardium showed general agreement for most of the heart, yet not in some areas (Figure 4). In one example in experiment D, the electric field was high near the coil but decreased quickly with distance from the coil in the simulated case; the transition was more gradual in the recorded data. The areas of maximum electric field, which correlated to the areas of maximum potential, were also shifted in experiments A, B, and C, with a superficial area of high electric field on the posterior wall of the heart in experiment B in the measured data, features not present in the simulation. The electric field direction, as indicated by the isopotential surface orientation (Figure 4), showed local differences between measured and simulated data, most notably in experiment B near the apex.

3.2. Scaled Distribution Threshold Comparison

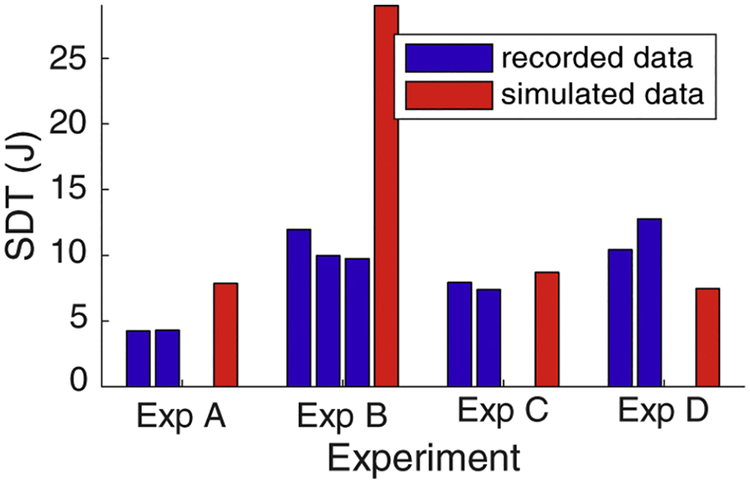

Comparing the SDT calculated from the measured and simulated fields through the myocardial tissue showed reasonable agreement in two of the experiments (A and C) but not the other two (B and D). The SDTs derived from the measured potentials ranged from 4.2 to 12.8 J, whearas simulated values were higher, from 7.5 to 29.0 J. As shown in Figure 5, the SDT varied within each experiment, with the greatest range occurring in experiment D (10.4 to 12.8 J) and the lowest range in experiment A (4.23 to 4.30 J). Experiment C showed the closest agreement between measurements and simulations with a difference of 1.0 J. Experiments A and D had similar agreement (3.6 and 4.1 J, respectively) while experiment B showed a much larger difference of 18.5 J. The SDT from simulated electric field values overpredicted the SDT from recorded data in experiments A and B and underpredicted in experiments C and D.

Figure 5:

Predicted SDTs based on recorded and simulated electric fields using the critical mass hypothesis (95 % over 5 V/cm). The SDT from each shock is shown compared to the simulated value from each experiment.

4. Discussion

The goals of this study were to show the feasibility of a new form of validation experiment and to compare measurements from an ICD in a torso tank experiment to result of our defibrillation simulation pipeline. The findings showed uneven but generally adequate agreement, both qualitatively and quantitatively with best agreement using SDTs and cumulative distribution functions (Section B.3, Figure B.1). These results, although in a limited number of experiments, provide a proof of concept that the torso-tank experimental preparation can be used to validate defibrillation simulations, including within the myocardium.

The high-density spatial sampling of this preparation provides a unique experimental validation of a simulation pipeline. Other studies with similar goals,12–14 i.e., recordings within the heart or on the body surface, omitted recording defibrillator potentials at this resolution and coverage within the heart and on the body surface. Using this novel preparation, we showed a higher correlation and lower relative RMS error than those shown in an in situ study based on measured epicardial potentials.14 We also showed a correlation and relative error similar to those in another in situ animal study based on sparse torso recordings.13 Our findings showed similar ρ, RE, and to those reported in our previous study based on measured body-surface maps during ICD testing.12

The comparisons of the SDTs calculated from the recorded and simulated electric fields provide some insight into the general accuracy of the simulation of defibrillation and the ability of the experimental preparation to capture the electric field (Figure 5). Although the measured and simulated SDTs did not agree in every case, they did show generally comparable values, which at least suggests that the electric field captured by the intramyocardial electrodes was dense enough to provide suitable spatial resolution.

The qualitative differences found in the potential fields (Figures 2, 3, and 4) suggest improvements for future experiments. For instance, since the only electrical sources are the ICD generator and coil, changes in the absolute maximum and minimum in the potential field and differences in potential gradient direction could easily be due to errors in the alignment of electrodes, particularly with the ICD coil (Figure 4). These same errors may also be the cause of the difference in calculated and measured SDTs and simulated fields. The greatest disagreements in SDT values were also correlated with the greatest qualitative differences in locations of the maxima and the greatest disagreement in lead impedance values (Exp. B, Section 3.1, Table B.1), suggesting a possible difference in the simulation and measurement setup relating to the path between the coil and the ICD generator again supporting the idea of misalignment of electrodes in the model. Heart shape also likely plays a role in the accuracy of the simulation, as evidence by the range of geometric values reported in Section B.2. Errors correlating to geometric measurements could be attributed to post experiment differences in cardiac state compared to other hearts or to errors in segmentation (Section B.2). Another possible source of error is the incomplete sampling with the intramyocardial needles in some experiments, e.g., Experiment D, in which the sock revealed large values outside the region covered by the needle electrodes.

As part of our analysis of our modeling pipeline, we explored various parameters of the simulation, including conductivities and geometric positions (Section B.4. Increasing the torso conductivity generally reduced the RE, but it also generally decreased ρ. This result suggests that there may be a systematic error similar to those reported in previous studies,13 attributed to errors in the estimated voltage drop of the device, conductivity values, lead impedance, or the insufficient temporal sampling. Perturbing the ICD device, coil, and heart positions did not reduce the errors in either the isotropic or anisotropic cases. The residual error could be attributed to compounded registration error associated with the generator, coil, heart, and electrode positions, but could also be due to errors in segmentation and other steps in the pipeline. Previous studies of uncertainty quantification by our group showed the geometric parameters could have substantial effects on the simulation of bioelectric fields and that there were complex interactions among these effects.20 Additional analyses, such as exploring the effect of wall thickness, as well as a more systematic exploration of the geometric sensitivity, could improve the simulation accuracy.

Other experimental design components may have affected the recorded potentials in ways that we could not fully elucidate from the data we captured. One potential cause of error is the attenuation of the defibrillators used in the torso-tank experiment. Tissue under large electric fields can produce nonlinear effects, such as electroporation,21 that would not be present in these attenuated shocks. However, previous studies have not shown these nonlinear effects to be significant.12–14 Similarly, although it is accepted that tissue conductivities can change post mortem,22 there was no consistent effect of perfusing the tissue in Experiment D on the resulting recordings in this study. Although the recordings from Experiment D were different from those for the other three, the data were inadequate to determine whether these differences were due to perfusion, species, or device placement.

In addition to experimental considerations, some of the assumptions made in the simulation pipeline could produce differences between measured and simulated potential fields. One previously discussed possible source of error was the isotropic conductivity values used in the simulation.12 Past studies have shown anisotropic conductivities were needed to accurately predict defibrillation potentials;14, 23 however, including anisotropy in our simulations had a mixed effect on their accuracy. A more systematic analysis of differing anisotropy ratios might reveal a parameter space that improves the accuracy of the simulation. High spatial sampling of the myocardial tissue during ICD shock showed local extrema, indicating that heterogeneous conduction might have occurred. More intricate modeling of the tissue heterogeneity in the myocardium, such as including cardiac vasculature or sheet structure,24, 25 may be needed to accurately predict the potential field generated by defibrillators. Another possible source of simulation error is the quasi-static assumption, which simplifies the computation of the potential field. The frequencies generated by the device are high enough that capacitive responses from the tissue would be possible.26

A major finding is that future studies using this torso tank preparation could improve our understanding of the myocardial response to defibrillators and provide a greater range of scenarios for validating simulations and their underlying mechanistic assumptions. With this setup, multiple ICD configurations could be tested to record their relative effect on the potential field through the heart, including subcutaneous and abdominal positions.11, 19 The setup also allows for heterogeneity of the torso volume by suspending geometries with specified conductivities in the tank, which could model lungs, ribs, and other relevant organs and their effect on the potential distribution.27 Exploring these variations in the experimental setup would help validate and improve the simulation by providing more comprehensive data than in past studies.

Perhaps the most valuable mechanistic contribution of the torso tank preparations lies in the exploration of the causes of successful and unsuccessful shocks. The virtual electrode hypothesis28 is generally considered the most accurate mechanistic explanation of defibrillation, while the critical mass hypothesis29 is much simpler and hence orders of magnitude less costly when used to compute DFTs. However, the critical mass hypothesis has shown inconsistent accuracy in predicting DFTs.10, 12, 30 With the high density needle recordings in our torso tank preparation, one could identify characteristics of the electric field that may affect the accuracy of the critical mass hypothesis, such as heterogeneity or spatial distribution of the tissue above the 5 V/cm threshold. Additional insight into these characteristics may help researchers fill the gap of understanding between the two hypotheses.

Clinical Implications:

The overall accuracy of the predicted potential fields compared to the measured values in these torso tank experiments provides important validation of our simulation pipeline to predict potential fields and DFTs. Combined with past validation studies,10, 12 these findings provide further support that the simulation of defibrillation can be effective as a patient-specific tool to facilitate defibrillator implantation or design, such as guiding new placements of ICDs in patients with abnormal or developing anatomies.10 The accuracy and computational efficiency of the pipeline also provides a possibility for an immediate impact as a planning tool for ICD implantation. The simulations could also be used to test new device configurations, such as subcutaneous ICD implantations,11 or to identify trends in defibrillator behavior based on many varied parameters, such as patient size, structural variability, tissue conductivity, and many more. With this simulation tool, which is demonstrably accurate, clinicians and researchers could better understand defibrillators for both individual and general applications.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we found that our simulation pipeline could consistently predict potential fields that exhibit high correlation to measured values throughout the torso volume, including on the epicardial surface and throughout the myocardial volume, and could generate reasonable electric field distributions. We also found that the simulation could predict SDT metrics that were roughly comparable to measured values. An expanded validation study using the torso-tank experimental preparation would provide further insight into the accuracy of the simulation, especially in predicting potential fields through the myocardium. Our findings also show the feasibility of using the torso-tank experimental preparation to validate the defibrillation simulation in the myocardium and provide further general confidence in the utility of simulations to improve defibrillation therapy.

Supplementary Material

6. Acknowledgements

The research presented in this paper was made possible with help from Philip Ershler, Bruce Steadman, Alicia Booth, Nancy Allen, and Jayne Davis from the Cardiovascular Research and Training Institute (CVRTI) and the Nora Eccles Treadwell Foundation. Technical editing was provided by Christine Pickett. Defibrillator equipment used in this study was provided by Medtronic plc and Boston Scientific Corp. This project was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P41GM103545.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- [1].Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. , Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: A report from the American Heart Association, Circ. 135 (10) (2017) e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Alexander M, Cecchin F, Walsh E, Triedman J, Bevilacqua L, Berul C, Implications of implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy in congenital heart disease and pediatrics, J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol 15 (2004) 72–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bokhari F, Newman D, Greene M, Korley V, Mangat I, Dorian P, Long-term comparison of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator versus amiodarone: Eleven-year follow-up of a subset of patients in the canadian implantable defibrillator study (CIDS), Circ. 110 (2004) 112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ristagno G, Wang T, Tang W, Sun S, Castillo C, Weil MH, High-energy defibrillation impairs myocyte contractility and intracellular calcium dynamics, Crit. Care Med 36 (11) (2008) S422–S427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Berul CI, Triedman JK, Forbess J, Bevilacqua LM, Alexander ME, Dahlby D, Gilkerson JO, Walsh EP, Minimally invasive cardioverter defibrillator implantation for children: an animal model and pediatric case report, Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol 24 (12) (2001) 1789–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lieberman R, Havel WJ, Rashba E, DeGroot PJ, Stromberg K, Shorofsky SR, Acute defibrillation performance of a novel, non-transvenous shock pathway in adult ICD indicated patients, Heart Rhythm J. 5 (1) (2008) 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bardy GH, Smith WM, Hood MA, et al. , An entirely subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator, New Eng. J. Med 363 (1) (2010) 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Auricchio A, Klein H, Geller CJ, Reek S, Heilman MS, Szymkiewicz SJ, Clinical efficacy of the wearable cardioverter-defibrillator in acutely terminating episodes of ventricular fibrillation, Am J Cardiol 81 (10) (1998) 1253–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wassnig NK, Gunther M, Quick S, Pfluecke C, Rottstadt F, Szymkiewicz SJ, Ringquist S, Strasser RH, Speiser U, Experience with the wearable cardioverter-defibrillator in patients at high risk for sudden cardiac death, Circ. 134 (9) (2016) 635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jolley M, Stinstra J, Pieper S, MacLeod R, Brooks DH, Cecchin F, Triedman JK, A computer modeling tool for comparing novel ICD electrode orientations in children and adults, Heart Rhythm J. 5 (4) (2008) 565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jolley M, Stinstra J, Tate J, Pieper S, MacLeod R, Chu L, Wang P, Triedman J, Finite element modeling of subcutaneous implantable defibrillator electrodes in an adult torso, Heart Rhythm J. 7 (5) (2010) 692–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tate J, Stinstra J, Pilcher T, Poursaid A, Jolley MA, Saarel E, Triedman J, MacLeod RS, Measuring defibrillator surface potentials: The validation of a predictive defibrillation computer model, Comp. in Biol. & Med 102 (2018) 402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2018.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jorgenson DB, Schimpf PH, Shen I, Johnson G, Bardy GH, Haynor DR, Kim Y, Predicting cardiothoracic voltages during high energy shocks: Methodology and comparison of experimental to finite element model data, IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng 42 (6) (1995) 559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Claydon F, Pilkington T, Tang A, Morrow M, Ideker R, Comparison of measured and calculated epicardial potentials during transthoracic stimulation, in: IEEE EMBS 10th Ann. Intl. Conf, IEEE Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 1988, pp. 206–207. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rodriguez B, Li L, Eason J, Efimov I, Trayanova N, Differences between left and right ventricular chamber geometry affect cardiac vulnerability to electric shocks, Circ. Res 97 (2) (2005) 168–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shome S, MacLeod R, Simultaneous high-resolution electrical imaging of endocardial, epicardial and torso-tank surfaces under varying cardiac metabolic load and coronary flow, in: Functional Imaging and Modeling of the Heart, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4466, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2007, pp. 320–329. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Milanic M, Jazbinsek V, Macleod R, Brooks D, Hren R, Assessment of regularization techniques for electrocardiographic imaging, J. Electrocardiol 47 (1) (2014) 20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].MacLeod R, Taccardi B, Lux R, Electrocardiographic mapping in a realistic torso tank preparation, in: Proceedings of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 17th Annual International Conference, IEEE Press, 1995, pp. 245–246. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jolley M, Stinstra J, Pieper S, MacLeod R, Brooks D, Cecchin F, Triedman J, A computer modeling tool for comparing novel ICD electrode orientations in children and adults, Heart Rhythm J. 5 (4) (2008) 565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Swenson D, Geneser S, Stinstra J, Kirby R, MacLeod R, Cardiac position sensitivity study in the electrocardiographic forward problem using stochastic collocation and BEM, Annal. Biomed. Eng 30 (12) (2011) 2900–2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jones JL, Jones RE, Balasky G, Microlesion formation in myocardial cells by high-intensity electric field stimulation, Am. J. Physiol 253 (2 Pt 2) (1987) H480–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.2.H480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Haemmerich D, Ozkan OR, Tsai JZ, Staelin ST, Tungjitkusolmun S, Mahvi DM, Webster JG, Changes in electrical resistivity of swine liver after occlusion and postmortem, Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing 40 (1) (2002) 29–33. 40 (1), doi: 10.1007/BF02347692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Trayanova N, Skouibine K, Aguel F, The role of cardiac tissue structure in defibrillation, Chaos 8 (1) (1998) 221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bishop MJ, Boyle PM, Plank G, Welsh DG, Vigmond EJ, Modeling the role of the coronary vasculature during external field stimulation, IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng 57 (10) (2010) 2335–2345. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2010.2051227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Connolly A, Vigmond E, Bishop M, Virtual electrodes around anatomical structures and their roles in defibrillation, PLOS ONE 12 (3) (2017) 1–19. 12 (3), doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173324. URL 10.1371/journal.pone.0173324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ashihara T, Trayanova NA, Asymmetry in membrane responses to electric shocks: insights from bidomain simulations, Biophys. J 87 (4) (2004) 2271–2282. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.043091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].MacLeod R, Taccardi B, Lux R, The influence of torso inhomogeneities on epicardial potentials, in: IEEE Computers in Cardiology, IEEE Computer Society, 1994, pp. 793–796. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Efimov I, Ripplinger CM, Virtual electrode hypothesis of defibrillation, Heart Rhythm J. 3 (9) (2006) 1100–1102. 3 (9), doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ideker RE, Wolf PD, Alferness C, Krassowska W, Smith WM, Current concepts for selecting the location, size and shape of defibrillation electrodes, PACE 14 (2 Pt 1) (1991) 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rantner L, Vadakkumpadan F, Spevak P, Crosson J, Trayanova N, Placement of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in paediatric and congenital heart defect patients: A pipeline for model generation and simulation prediction of optimal configurations, J. Physiol 591 (Pt 17) (2013) 4321–4334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.