Highlights

-

•

A total of 12 articles were included.

-

•

The number of domains varied across all of the selected studies.

-

•

This scoping review indicates that communication and ICS are essential domains.

-

•

Disaster planning is one of the most important core competencies for nurses.

-

•

Another of the important domains are decontamination and ethics.

Keywords: Disaster, Management, Competency, Review, Nursing, Preparedness, Skills, Knowledge

Abstract

Aim

Scoping review was conducted to identify the most common domains of the core competencies of disaster nursing.

Background

Nurses play an essential role in all phases of disaster management. For nurses to respond competently, they must be equipped with the skills to provide comprehensive and holistic care to the populations affected by or at risk of disasters.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology. The review used information from six databases: the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Ovid MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, Scopus and the Education Resources Information Center. Keywords and inclusion and exclusion criteria were identified as strategies to use in this review.

Results

Twelve studies were eligible for result extraction, as they listed domains of the core competencies. These domains varied among studies. However, the most common domains were related to communication, planning, decontamination and safety, the Incident Command System and ethics.

Conclusion

Knowledge of the domains of the core competencies, such as understanding the content and location of the disaster plan, communication during disaster and ethical issues is fundamental for nurses. Including these domains in the planning and provision of training for nurses, such as disaster drills, will strengthen their preparedness to respond competently to disaster cases. Nurses must be involved in future research in this area to explore and describe their fundamental competencies in each domain.

1. Background

A disaster can be defined as significant damage to property and people’s lives caused by an event that overwhelms the local community’s human resources [32]. Both natural and manmade disasters have significant effects on the health and the physical, emotional and psychological states of community members [27]. To control the possible negative effects of a disaster, a disaster management strategy must be implemented. The four main stages of providing proper disaster management are mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery [7]. Typically, mitigation and preparedness are implemented before a disaster occurs; the response stage is initiated during the disaster; and the recovery stage is carried out after the disaster [27]. The disaster management phases are summarised in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Phases of disaster management.

| Phase | Concept |

|---|---|

| Preparedness | Preparation not only includes assigned programmes or plans but also ensures continuous education that focuses on long-term goals, training, assessment and evaluation for all activities involved in managing disasters [7], [32]. |

| Mitigation | Mitigation requires a comprehensive plan for identifying risks and strengthening the resilience of response mechanisms [5]. |

| Response | Response to a disaster focuses on saving lives, reducing damage to infrastructure and supporting families through the provision of care, including food and shelter [27], [32]. |

| Recovery | Recovering from a disaster refers to restoring anything that was destroyed and returning to normal levels of functioning [27]. |

The increasing frequency of disasters globally has created an urgent need for international organisations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), to develop effective plans for disaster preparedness and management [36]. However, it is nurses that account for the largest professional group in the health sector, and they play a critical role in all phases of disaster management [32]. Nurses provide holistic care for victims and their families. Daily et al. [8] argued that, at the scene of a disaster, nurses can work as coordinators, information distributers, emotional and psychological supporters and clinical and first aid providers; further, they can triage victims and prioritise patients’ needs for care. Confidently responding to disasters and effectively providing help to the affected people requires adequately prepared nurses.

The International Council of Nurses’ (ICN) disaster nursing framework identified three phases of disasters for nurse competency (2009). First, the pre-event phase focuses on ensuring that nurses possess adequate knowledge, skills and abilities in the identification of risks, execution of response plans and preparation for all types of disasters before they occur. Second, in the disaster phase, nurses must provide physical, psychological and holistic care competently for individuals, families and communities along with special populations, such as children and the elderly. Finally, during the post-disaster phase, recovery and reconstruction take place. According to the ICN and WHO [16] nurses must have the sufficient knowledge and skills to care for the affected communities, individuals and families, not only in the immediate period but also in the long term.

Nurses have few opportunities to develop their expertise, yet they require regular education and practice, especially regarding how to care for patients exposed to chemical and biological radiation or nuclear hazards [33]. They are often not well prepared for caring for patients with symptoms related to biological weapons [1], [19], [34]. To ensure that nurses are well prepared and have the adequate knowledge and skills required for all phases of disaster management, international efforts have been made to develop the core competencies of disaster nursing [8], [34]; however, these core competencies are inconsistent in their terminology and structures. For example, nurses in Japan are not familiar with the term competencies [17]. There is also a lack of evidence supporting the most appropriate set of the core competencies of disaster nursing [8]. Determining the most common domains of the core competencies of nurses identified in previous studies would help develop specific education programmes for disaster nursing preparedness, provide training and conduct research. This notion was supported by Ling and Daily [20], who claimed that the development of education and training programmes for competencies in general or for specific areas is required to strengthen the level of preparedness of nurses worldwide.

2. Methods

A scoping review is a review of the literature that aims to identify the amount and quality of research on a certain topic. In other words, a scoping review focuses on identifying what is known about a topic and its associated characteristics in the existing literature [6]. The methodology of this scoping review was adopted from that described in The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewers’ Manual 2015, Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews [25] and includes the following: identifying the research objective(s) and question(s); outlining the inclusion and exclusion criteria; identifying search strategies; extracting the results; discussing the results and drawing conclusions, including the implications for future research and practice.

3. Objective and research question

The objective of this scoping review was to identify the most common domains of the core competencies of nurses in disaster management. The research question was as follows: What are the most common domains of the core competencies of nurses in disaster management?

4. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The studies that were reviewed were selected according to inclusion and exclusion criteria related to the type of participant, phenomenon of interest, outcomes and type of study. The scoping review examined studies of the core competencies in disaster management for nurses in a range of different hospital settings, such as emergency departments, critical care units, medical wards and surgical wards. Moreover, studies that involved nurses outside of hospital settings, such as community nurses, were also considered. This review considered studies that listed the domains of the core competencies of disaster nursing in both natural and man-made disasters. It also examined studies that included the following important domains of the core competencies of nurses during all phases of disaster management: mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery. Lastly, this scoping review included all types of studies (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods and expert opinions).

The other inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review focused on the following: time period, language, type of article, study focus, setting, place of study and population and sample. Table 2 summarises all the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria along with the research objective and question guided the data extraction and presentation. While the framework used can be flexible, it was iterative in this study. Data that were relevant to the research question and objective were extracted.

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Time period | From database inception to 2015 | Nil |

| 2. Language and length of article | English/full article | Non-English/Abstract |

| 3. Types of articles | Original research published in peer-review journal or in the grey literature | Lesson learned report, or thesis |

| 4. Study focus | Competencies of disaster nursing | All studies not related to the study focus. |

| 5. Setting | Hospitals, communities, disaster science | Nursing home, nursing school |

| 6. Place of study | International | Nil |

| 7. Population and sample | Nurses work in and out hospitals | Nursing student, Physicians, paramedics and other health care providers |

5. Search strategies

Identifying the relevant studies on the core competencies of disaster nursing revealed existing knowledge on the topic. Initial limited searches of Ovid MEDLINE and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) were performed. This was followed by an analysis of the words contained in the title and the abstract, as well as the index terms used to describe the article. Then, a search was conducted to locate the published studies in English from the inception of the identified journals up until 2015. Extensive searches were conducted in the following electronic nursing databases: (1) CINAHL, (2) Ovid MEDLINE, (3) ScienceDirect, (4) ProQuest, (5) Scopus and (6) the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC). The keywords used in the searches were as follows: disaster and nursing; preparedness; competencies; response; drill; ability; capability; roles; function; knowledge and skills; and willingness and barriers. The searches were conducted both electronically and manually by searching for relevant articles in the reference lists of the selected articles. The Scopus database and Google Scholar were used to find more papers using ‘cited by’ lists. The searches were not limited to the database indexes; they also included grey literature.

6. Study selection

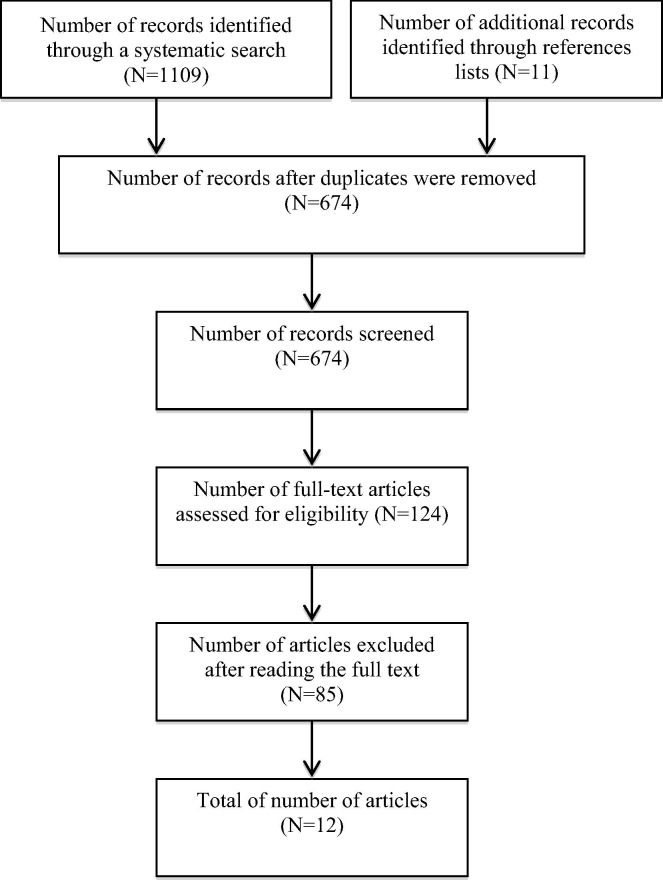

The searches of the electronic databases resulted in 1109 articles in total (CINAHL, n = 493; Scopus, n = 329; ScienceDirect, n = 69; ProQuest, n = 78; and Ovid MEDLINE, n = 140). The number of articles was reduced to 124 for the following reasons: (1) some articles were not based on research or literature reviews; (2) some articles were duplicates; (3) some articles were only available in the abstract form and (4) some articles focused on nursing homes and nursing students. Ultimately, 124 articles were read in full; 85 were reread for reviewing and data extraction, 73 of which were determined to be unrelated to the objectives of this study because they did not list core competencies as outcomes. Therefore, a total of 12 articles were included in the scoping review. The search strategy is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

PRISMA.

7. Extraction and results

The data from the 12 included studies were charted according to their author(s), years, locations, methodologies and domains of competencies. The data relevant to the objectives of this scoping review are shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Domains of Core Competencies.

| Authors | Year | Core Competency Domains |

|---|---|---|

| Gebbie & Qureshi | 2002 |

|

| Stanley et al. | 2003 |

|

| Wisniewski et al. | 2004 |

|

| Markensn et al. | 2005 |

|

| Hsu et al. | 2006 |

|

| Polivka et al. | 2008 |

|

| Everly, Beaton, Pfefferbaum, & Parker | 2008 |

|

| Subbarao et al. | 2008 |

|

| ICN & WOH | 2009 |

|

| Walsh et al. | 2012 |

|

| Schultz et al. | 2012 |

|

| Marin & Witt | 2015 |

|

The number of domains varied across the selected studies. The first study, conducted by Gebbie and Qureshi [13], identified 11 competency domains in which nurses must be educated and trained. In 2003, the International Nursing Coalition for Mass Casualty Education (INCMCE) developed the core competencies for registered nurses and students. These competencies include 10 domains, the following 4 of which are main core competencies: critical thinking, assessment, technical skills and communication skills. The other six are associated with core knowledge [30]. In 2004, eight dimensions of emergency preparedness competencies were developed by Wisniewski et al. [37] based on previous research conducted at Vanderbilt University and by the ICNMCE. These competencies are important for all healthcare workers, particularly nurses; however, their study focused only on the response and preparedness phases and did not include other important phases, such as mitigation and recovery. In 2005, Markenson et al. [23] identified 22 domains of core competencies: 8 for principal management, 5 for terrorism, 2 for public health and 7 for patient care.

Hsu et al. [15] used a systematic consensus to identify the fundamental knowledge and skills required for disaster nursing. Their study consisted of the following five stages: a literature review, a structure review, synthesis, refinement and the development of objectives. Valid contributions were provided regarding seven important domains of the competencies of healthcare providers. Surprisingly, among the seven core competency domains, no themes were generated for several of the important domains confirmed by previous research ([16], [29], such as ethical issues, surge capacity and capability. Furthermore, it is unclear how the specific objectives in each domain of Hsu et al.’s [15] study were measured, as they seem broad and were not determined based on specific objectives.

In 2008, three studies were conducted in the United States to explore the core competencies of disaster nursing [26], [11], [31]. Each study contributed to the body of knowledge on disaster nursing by organising the competencies in each phase of disaster management. Polivka et al. [26] identified a total of 25 competencies (10 for disaster preparedness, 8 for response and 7 for recovery). Everly et al. [11] identified five domains of core competencies, while Subbarao et al. [31] identified seven domains, including planning, communication and ethics. Although there were differences in the number of domains in the three studies, they found similar domains, such as planning, communication and the Incident Command System (ICS). However, serious doubts have been raised regarding how the competencies in all of these studies are to be measured.

A study was conducted by the ICN and WHO in 2009 that differed from previous studies in several respects. The study reviewed two documents created by Stanley [30] and Yamamoto [38] to develop the core competencies of disaster nursing. The ICN helped explain the importance of disaster management for nurses and identified the knowledge, skills and abilities that nurses must have in each phase of a disaster (i.e., mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery). Approximately 130 core competencies were identified across 10 domains. As such, the study helped develop disaster nursing core competencies and tested the levels of nurses’ competencies. This is understood to be the only framework that has been developed for determining the core competencies of disaster nursing. However, the focus of this study was on general nurses; thus, the core competencies for emergency nurses were not understood completely.

There has been a gradual development in the core competencies of healthcare providers, particularly nurses. Researchers have developed many core competencies based on specific objectives [29], [35]. For instance, Walsh et al. [35] outlined the core competencies as having 11 domains, along with 37 sub-competencies. Although considerable progress was made in their study, concerns regarding the core competencies in triage, transportation and psychological issues remained unexplored. However, a solution was proposed by Schultz et al. [29], who identified 19 core competencies and more than 90 objectives. In doing so, they contributed to knowledge regarding disaster management for all healthcare providers (i.e., physicians, nurses and emergency management staff), both inside and outside of hospitals. The last study used a different methodology, as emergency nurses in Brazil were interviewed about the domains of the core competencies of disaster management; as a result, five domains were identified with a total of 17 competencies focused mainly on preparedness and response [22].

While several competency sets have been designed, no unified standards have been formulated; therefore, the sets are inconsistent and have yet to be validated empirically. The structures of these core competencies differ across previous studies; however, the most common domains that were found across the selected studies include knowledge related to the following: (1) communication, (2) planning, (3) decontamination and safety, (4) ICS and (5) ethics. Each competency is a key component of disaster preparedness and response.

8. Discussion

This scoping review focused on identifying the most common domains of the core competencies of nurses in regard to disaster management and was conducted systematically using the JBI methodology. To date, no unified standards for competencies have been formulated or validated empirically, and disaster vocabularies vary across studies. Efforts to explore disaster nursing core competencies in different healthcare systems and cultures would contribute to the body of knowledge on disaster nursing. The findings indicate that many domains in this area can be explored by healthcare providers, particularly nurses. Most importantly, the most common domains of the core competencies examined include possessing adequate knowledge of how to initiate disaster plan management using the ICS, clear communication, decontamination and ethics.

In the need to develop a framework for nurses to mitigate, prepare for, respond to and recover from disasters, the ICN created a list of core competencies in 2009 to help facilitate deployment, create consistency in practice, facilitate communication, promote shared aims and help nurses work within organisational structures with unified approaches. The ICN Disaster Nursing Competencies were designed to serve all nurses globally [16] and applies to all nursing settings (mental health, public health nursing, emergency nursing, nursing education, etc.). After, the ICN and WHO [16] developed the Framework of Disaster Nursing Competencies, and it became the basis for a study that examined China’s student training programmes for disaster nursing [21]. Daily and Williams [9] recommended this framework for developing disaster core competencies and curricula to educate healthcare providers. It is important to consider the Framework of Disaster Nursing Competencies in developing educational and training programmes for nurses who expect to participate in disaster response, as this work covers all stages of disaster management.

Disaster planning is one of the most important core competencies for nurses who must be equipped with the essential knowledge and skills needed to be competent in planning for disasters [1], [3], [2], [4], [14], [18]. Competencies related to planning include being aware of the location of the disaster plan and having the ability to activate it [37]. For an enhanced response, nurses should understand the purpose and content of the disaster plan. For instance, to provide effective action during a critical event or disaster, nurses must know how to respond, communicate and formulate a new plan if the situation changes suddenly [29]. For nurses to be capable of initiating a disaster plan, they must participate in its creation, as well. The proper execution of a plan requires continuous evaluation, education, training and drills [5]. After 9/11, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organisations (JCAHO) challenged all healthcare organisations in the United States to create plans that would facilitate the effective management of disasters [10]. These plans were required to include the assessment and preparedness phases, understand risks and minimise their effects and provide outlines of the response and recovery processes [10]. These requirements suggest that nurses will respond more effectively to disaster situations if they are familiar with the content and location of the disaster plan. To ensure that this is the case, education, training and further research that investigates the current issues associated with planning, such as barriers to nurses’ participation in creating disaster plans, is highly recommended. However, it must be acknowledged that staff nurses in many countries already participate in disaster exercises and training activities related to disaster management. These activities range from drills and discussion-based programmes, such as seminars and table-top exercises, to more complex operation-based initiatives, including functional and full-scale exercises [27].

This scoping review indicates that communication and ICS are essential domains of the core competencies of nurses because they were reported repeatedly in several of the selected studies. The JCAHO further emphasised the importance of cooperation and communication between healthcare institutions and the development of a chain of command [10]. All nurses must demonstrate proficiency in their understanding of the principles of communication as well as of alternative approaches. Previous studies have shown that hospitals often exhibit poor communication and a lack of planning, motivation, empowerment, common language, disaster-trained staff, qualified and knowledgeable managers and emergency ICSs [39]. Moreover, nurses must know the structure of the ICS at the national, local and institutional levels [23], [29], understand the roles of the command staff and comprehend how communication flows in the system. It is also imperative that nurses understand the decision-making process during times of disaster [37].

Another important domain of the core competencies of disaster nursing is decontamination, which involves the removal of contaminated substances, including those that are chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear. For proper decontamination to occur, nurses must be able to identify the essential equipment and use protective personal equipment properly [32]. Access to protective personal equipment, vaccinations and other resources increases the potential willingness of nurses to respond to a disaster [24], [34]. Moreover, nurses must be familiar with decontamination procedures and be capable of using the required equipment to protect both their own safety and the safety of patients. Willingness and competence are required for effective responses, such as were seen in the global responses to severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2002–2004 and in the H1N1 flu pandemic in 2009.

Previous studies also considered ethics in disaster as an essential knowledge area for all healthcare providers, including nurses. For instance, Walsh et al. [35] demonstrated that healthcare providers must be proficient in identifying and discussing the general ethical issues relating to the standards of care and resources during times of disaster. Having adequate knowledge and a full understanding of the principal ethical issues involved in disaster situations can prepare nurses to respond with confidence to related problems [28]. Considering ethics is important; as such, ethics should be included as a consideration in disaster nursing education, drills, research and planning [12].

9. Limitations

This review included papers written in English only. Moreover, most of the studies were conducted in the United States even though the existing literature is diverse. The populations, contexts and concepts of the literature are features of their methodologies rather than their quality.

10. Conclusion

This scoping review outlined the most common domains of the core competencies of nurses. Including these domains in the planning and provision of training for nurses, such as disaster drills, will strengthen their readiness and preparedness to respond with competence in cases of disaster. Nurses need to be involved in future research in this area to explore and describe their fundamental competencies in each domain. Furthermore, programmes providing disaster training, either online or through comprehensive disaster preparedness models, could be essential to improving the knowledge and skills of nurses with regard to disaster management.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have any actual or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Abdullelah Al Thobaity, Email: abdulelahw@hotmail.com.

Virginia Plummer, Email: Virginia.Plummer@monash.edu.

Brett Williams, Email: Brett.Williams@monash.edu.

References

- 1.Al Khalaileh M.A., Bond E., Alasad J.A. Jordanian nurses’ perceptions of their preparedness for disaster management. Int Emerg Nursing. 2012;20(1):14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Thobaity A., Plummer V., Innes K., Copnell B. Perceptions of knowledge of disaster management among military and civilian nurses in Saudi Arabia. Austr Emerg Nurs J. 2015;18(3):156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Thobaity A., Williams B., Plummer V. A new scale for disaster nursing core competencies: development and psychometric testing. Austr Emerg Nurs J. 2016;19(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arbon P., Ranse J., Cusack L., Considine J., Shaban R.Z., Woodman R.J. Australasian emergency nurses’ willingness to attend work in a disaster: A survey. Austr Emerg Nurs J. 2013;16(2):52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barton C.C. Disaster preparedness and management. In: Philip W., editor. Information resources in toxicology. 4th ed. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2009. pp. 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booth A., Papaioannou D., Sutton A. Sage Publications Ltd.; London: 2011. Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coppola D.P. Introduction to international disaster management. 2nd ed. Butterworth-Heinemann; Boston, MA: 2011. The management of disasters; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daily E., Padjen P., Birnbaum M. A review of competencies developed for disaster healthcare providers: limitations of current processes and applicability. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2010;25(5):387–395. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00008438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daily E, Williams J. White paper on setting standards for selecting a curriculum in disaster health. World Association for Disaster and Emergency Medicine. 19 April 2013 <http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.361.6364&rep=rep1&type=pdf>.

- 10.Eiland J.E., Pritchard D.A., Stevens D.A. Emergency preparedness: is your OR ready? AORN J. 2004;79(6):1275–1283. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)60882-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everly G.S., Beaton R.D., Pfefferbaum B., Parker C.L. Training for disaster response personnel: the development of proposed core competencies in disaster mental health. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(4):539. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frumkin H., Frank L., Jackson R.J. Island Press; 2004. Urban sprawl and public health: designing, planning, and building for healthy communities. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gebbie K.M., Qureshi K. Emergency and disaster preparedness: core competencies for nurses: what every nurse should but may not know. Am J Nurs. 2002;102(1):46–51. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200201000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammad K.S., Arbon P., Gebbie K., Hutton A. Nursing in the emergency department (ED) during a disaster: a review of the current literature. Austr Emerg Nurs J. 2012;15(4):235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu E.B., Thomas T.L., Bass E.B., Whyne D., Kelen G.D., Green G.B. Healthcare worker competencies for disaster training. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6(1):19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ICN, WHO. ICN Framework of disaster nursing competencies. World Health Organization and International Council of Nurses; 2009. <http://myweb.polyu.edu.hk/~hswhocc/resource/D/2009DisasterNursingCompetencies.pdf>.

- 17.Kako M., Mitani S. A literature review of disaster nursing competencies in Japanese nursing journals. Collegian. 2010;17(4):161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kako M., Mitani S., Arbon P. Literature review of disaster health research in Japan: focusing on disaster nursing education. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2012;27(02):178–183. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X12000520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kayama M., Akiyama T., Ohashi A., Horikoshi N., Kido Y., Murakata T. Experiences of municipal public health nurses following Japan’s earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster. Public Health Nurs. 2014;31(6):517–525. doi: 10.1111/phn.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ling K.W., Daily E.K. Linking competency with training needs: session summary on disaster studies and evaluation, Session No. 17. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2016:1–2. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X15005580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loke A.Y., Fung O.W.M. Nurses’ competencies in disaster nursing: implications for curriculum development and public health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(3):3289–3303. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110303289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marin S.M., Witt R.R. Hospital nurses’ competencies in disaster situations: a qualitative study in the south of Brazil. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2015;1–5 doi: 10.1017/S1049023X1500521X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markenson D., DiMaggio C., Redlener I. Preparing health professions students for terrorism, disaster, and public health emergencies: core competencies. Acad Med. 2005;80(6):517–526. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200506000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin S.D. Nurses’ ability and willingness to work during pandemic flu. J Nurs Manag. 2011;19(1):98–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters M., Godfrey C., McInerney P., Soares C., Khalil H., Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute; Adelaide, South Australia: 2015. Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Manual; p. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polivka B.J., Stanley S.A., Gordon D., Taulbee K., Kieffer G., McCorkle S.M. Public health nursing competencies for public health surge events. Public Health Nurs. 2008;25(2):159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powers R., Daily E., editors. International disaster nursing. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroeter K. Nurses, ethics, and times of disaster. Perioperat Nurs Clin. 2008;3(3):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.cpen.2008.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schultz C.H., Koenig K.L., Whiteside M., Murray R. Development of national standardized all-hazard disaster core competencies for acute care physicians, nurses, and EMS professionals. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2012;59(3):196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanley J. International Nursing Coalition for Mass Casualty Education; Nashville: 2003. Using an untapped resource: educational competencies for registered nurses responding to mass casualty incidents. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subbarao I., Lyznicki J.M., Hsu E.B., Gebbie K., Markenson D., Barzansky B. A consensus-based educational framework and competency set for the discipline of disaster medicine and public health preparedness. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness. 2008;2(1):57–68. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e31816564af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veenema T.G. Springer Publishing; 2012. Disaster nursing and emergency preparedness for chemical, biological, and radiological terrorism and other hazards. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veenema T.G., Rains A.B., Casey-Lockyer M., Springer J., Kowal M. Quality of healthcare services provided in disaster shelters: An integrative literature review. Int Emerg Nurs. 2015;23(3):225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veenema T.G., Walden B., Feinstein N., Williams J.P. Factors affecting hospital-based nurses’ willingness to respond to a radiation emergency. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness. 2008;2(4):224–229. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e31818a2b7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walsh L., Subbarao I., Gebbie K., Schor K.W., Lyznicki J., Strauss-Riggs K. Core competencies for disaster medicine and public health. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness. 2012;6(1):44–52. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2012.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.WHO . World Health Organization; 2007. Risk reduction and emergency preparedness: WHO six-year strategy for the health sector and community capacity development. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wisniewski R., Dennik-Champion G., Peltier J.W. Emergency preparedness competencies: assessing nurses’ educational needs. J. Nurs. Adm. 2004;34(10):475–480. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200410000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto A. Disaster nursing in an ubiquitous society. Japan J Nurs Sci. 2004;1(1):57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yarmohammadian M.H., Atighechian G., Shams L., Haghshenas A. Are hospitals ready to respond to disasters? Challenges, opportunities and strategies of Hospital Emergency Incident Command System (HEICS) J Res Med Sci. 2011;16(8):1070–1077. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]