Abstract

Introduction

The primary aim of this study was to explore the perception of Hong Kong emergency nurses regarding their work during the human swine influenza pandemic outbreak.

Methods

In this exploratory, qualitative study, 10 emergency nurses from a regional hospital in Hong Kong were recruited using purposive sampling. Semi-structured, face-to-face individual interviews were conducted. Qualitative content analysis was utilized to analyze the transcripts.

Results

The three following categories emerged from the interview data: concerns about health, comments on the administration, and attitudes of professionalism. Nurses viewed the human swine influenza as a threat to their personal and families’ health. However, nurses perceived that the severity of the disease was exaggerated by the public. Improvements in planning the circulation of information, allocation of manpower, and utilization of personal protective equipment were indicated. The emergency nurses demonstrated a sense of commitment and professional morale in promoting a high quality of nursing care.

Discussion

Various factors affecting the perceptions of emergency nurses toward their professional duties during the influenza pandemic were identified. By understanding these perceptions, appropriate planning, policies, and guidelines can be formulated to meet the healthcare needs of patients during future pandemic outbreaks.

Keywords: Influenza pandemic, Emergency nursing, Qualitative, Perception

Introduction

In recent decades, there have been various episodes of global influenza outbreaks. The latest influenza pandemic event started with the detection of a rapidly circulating new influenza strain called the human swine influenza (HSI) (WHO, 2010). The high frequency and intensity of procedures that involve close physical patient contact present occupational hazards for emergency nurses (Tam et al., 2007). In addition, uncertainties about patients’ infectious condition are extremely alarming for emergency nurses providing nursing care (Ovens et al., 2003). However, available studies about nurses’ pandemic experiences during the HSI pandemic are limited, lacking in both quantitative and qualitative research (Corley et al., 2010). This study gathered insight from emergency nurses in Hong Kong (HK) regarding their experience and perceptions toward work during HSI outbreak. The results of this study will contribute to developing preparedness at healthcare institutions in response to future pandemics.

Methods

An exploratory, qualitative design was adopted to explore the perception of HK emergency nurses regarding their work during the HSI pandemic outbreak. Qualitative research is an interpretive and naturalistic approach of enquiry that emphasizes the description of given meanings about human experiences and realities (Denzin and Lincoln, 2003). Employing an exploratory qualitative design in this study is appropriate to capture the subjective and humanistic perspective of work from emergency nurses during the HSI pandemic. An in-depth understanding of their perceptions will therefore be achieved.

Study setting

The study was conducted in the emergency department of a regional hospital in HK. The hospital provides 24-h emergency services and has high standard isolation and support facilities available to provide in-patient healthcare services for infectious patients.

Study population

Ten emergency nurses were recruited from the emergency department. The recruitment was based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) registered nurses; (2) full-time staff in the emergency department from the time of the outbreak of the HSI pandemic, designated as 1st June, 2009, to the date of participant recruitment; and (3) able to communicate in Cantonese. Exclusion criterion included nurses at an administrative or managerial level who were detached from direct patient contact procedures.

Sampling method

Participants were selected by purposive sampling. Purposive sampling is a non-probability sampling method where participants are deliberately chosen by the researcher according to the study requirement (Polit and Beck, 2008). In selecting participants, representative and productive individuals were invited to enhance the diversity and richness of captured information (Polit and Beck, 2010). Thus, participants with different characteristics such as age and work experience are chosen by the researcher to establish a wide range of information.

Sample size determination

For qualitative research, no absolute rules determine the estimated number of respondents. Recruitment should continue until data are saturated with recurrent ideas yielded and no new information is anticipated (Polit and Beck, 2010). However, due to the intensive labor required in meeting data saturation under time constraint, 10 nurses were recruited.

Sampling procedure

Given that the researcher had worked as an emergency nurse previously in the department, possible participants were identified according to the researcher’s judgment and the sampling criteria mentioned. From September 2010 to March 2011, eligible nurses were approached in person by the researcher and verbal invitations to participate were given individually.

Data collection method

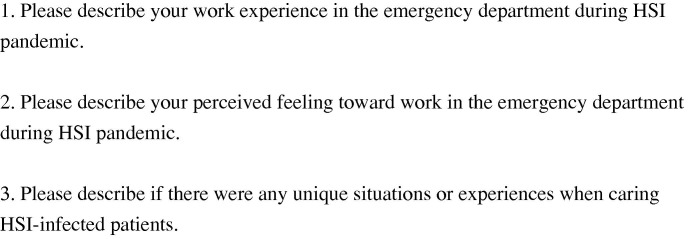

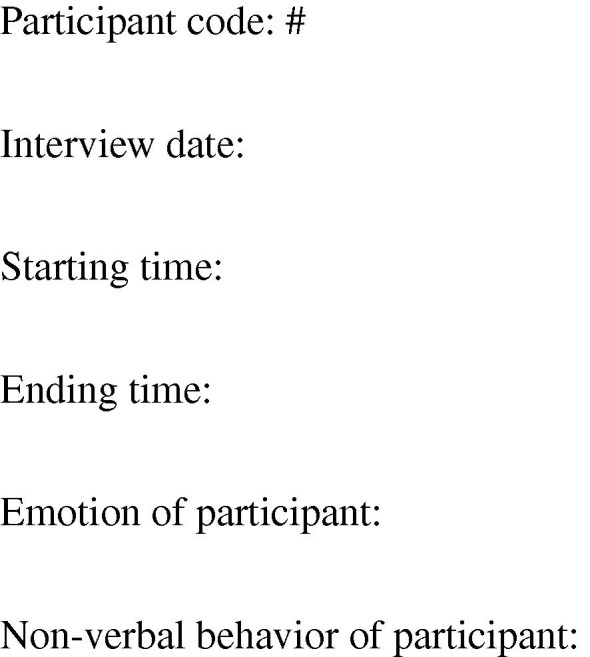

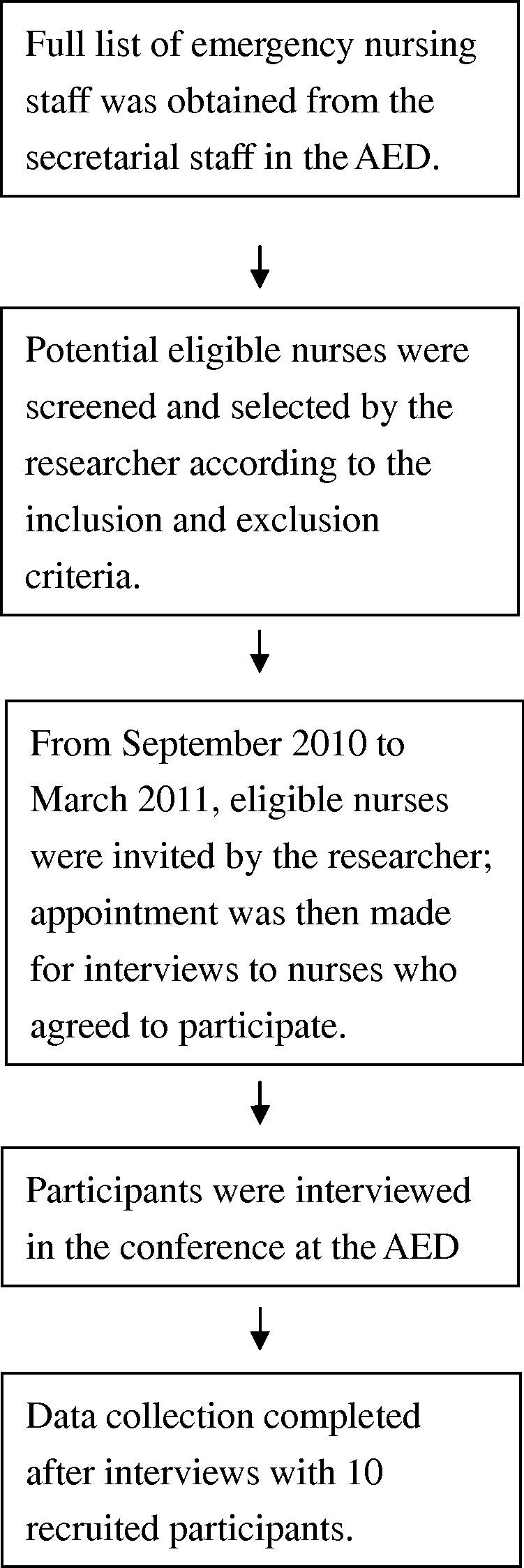

Semi-structured, face-to-face individual interviews were conducted by the researcher. A semi-structured interview guide (Fig. 1 ) was designed to elicit perceptions from the participants about their experiences working during the pandemic. The use of semi-structured interviews allows an in-depth exploration of participants’ perspectives (Parahoo, 2006). Participants were invited to freely verbalize their experiences and perceptions regarding their professional duties during the HSI pandemic. Field notes (Fig. 2 ) were recorded during and after the interviews about significant observations from informants’ physical expressions and gestures to enhance exploration of the participants’ verbal and non-verbal information (Robson, 2002). A tape recorder was also used to audiotape the interviews to help the researcher obtain accurate conversational data with complete wordings from informants (Polit and Beck, 2008). Flowchart of recruitment and data collection procedure is shown in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 1.

Interview guides for semi-structured interviews (translated from Chinese to English).

Fig. 2.

Interview field note record.

Fig. 3.

Flowchart of recruitment and data collection procedure.

Data management technique

The tape recordings were transcribed verbatim in Cantonese (Chinese) by the researcher after the interviews. Significant observations from informants’ physical expressions and gestures based on field notes recorded during the interviews were also incorporated. After each transcription, collation of the transcript was checked against the tapes and the field notes to ensure correctness. To reinforce accuracy of the verbatim content, audiotapes and transcriptions were sent to the research supervisor for checking and advice.

Data analysis

Qualitative content analysis was used to analyze the transcripts of the interviews. According to Hsieh and Shannon (2005), content analysis is “a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of textual data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns” (p. 1278). The data analysis process was active and interactive and proceeded by the researcher throughout the process of data collection (Polit and Beck, 2010). In conducting content analysis, three basic steps are involved: identifying meaning units, creating categories, and developing schemes of categorization (Berg, 2007).

Identifying meaning units

The transcriptions of the 10 participants were meticulously read and reread to reinforce further understanding of the contextual meaning. Texts with same central meaning were segmented to meaning units and sorted out from transcriptions. Codes were then assigned to the meaning units to represent threads from the dimension of emergency nurses.

Creating categories

Meaning units sharing the same manifested threads and contents were divided into sub-categories. Accumulation and comparison of sub-categories were performed by the researcher to explore similarities and differences in the participants’ dimensions. Subsequently, analogue sub-categories were sorted together into categories.

Developing schemes of categorization

The entire corpus of text was examined, and each meaning unit was categorized appropriately by the researcher according to the content and contextual meaning.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness is a criterion which constitutes rigor in a qualitative research (Parahoo, 2006). According to Guba (1981), trustworthiness is offered by four issues: credibility, confirmability, transferability, and dependability. Several techniques were employed to enhance trustworthiness of the study.

Credibility

Credibility of the study was assured by peer debriefing from the researcher’s supervisor. Through frequent debriefing sessions between the researcher and the supervisor, the study’s progress was reported and discussed. Critical evaluation was made by the supervisor to draw attention to flaws in the inquiry.

Confirmability

Member-checking was completed with all the 10 participants for validation of interpreted findings (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). A summary of the study result was reviewed by the participants to check congruency between the researcher’s interpretation and the participants’ actual intention.

Transferability

A vivid description of information about the inquiry was rendered to ensure sufficient contextual information about the study is granted. Transferring the findings and conclusions to similar situations could then be facilitated in other studies (Polit and Beck, 2008).

Dependability

An in-depth operational description of the method adopted in the study was demonstrated to account for a comprehensive understanding of the research methodology. Repetition of the study would thereby be enabled for future researchers.

Ethical consideration

Formal ethical approval was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee prior to the study. Participants were guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality. The study’s purpose and interview type were fully explained to the participants. Informed written consents were given to the participants to ensure their right to full disclosure.

Results

The demographic characteristics of participated nurses are summarized in Table 1 . The categories and sub-categories emerging from the interview data are listed in Table 2 .

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participated nurses.

| Participated nurses (N = 10) ƒ (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 20–25 | 2 (20) |

| 26–30 | 2 (20) |

| 31–35 | 2 (20) |

| 36–40 | 3 (30) |

| Over 40 | 1 (10) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 10 (100) |

| Male | 0 (0) |

| Ranking | |

| Nursing officer | 1 (10) |

| Advanced practice nurse | 1 (10) |

| Staff nurse | 8 (80) |

| Years of working experience (years) | |

| 1–5 | 2 (20) |

| 6–10 | 3 (30) |

| 11–15 | 3 (30) |

| More than 15 | 2 (20) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 5 (50) |

| Single | 5 (50) |

Table 2.

Categories and sub-categories emerging from the interview data.

| Categories | Sub-categories |

|---|---|

| Concerns about health | • Personal health |

| • Health of household members | |

| • Health of the public | |

| Comments on the administration | • Communication |

| • Manpower | |

| • Personal protective equipment | |

| Attitudes of professionalism | • Demonstrating professional commitment |

| • Maintaining professional morale | |

| • Striving for quality of care | |

Concerns about health

Personal health

Nurses, especially those working in the emergency department, are vulnerable to infection (Sugerman et al., 2011). Four out of the 10 participants expressed concerns about their susceptibility to infection. One nurse expressed the following:

“I am extremely worried about contracting the disease because the death rate of HSI is high, much higher than common seasonal flu.”

However, a striking difference was noted regarding the perception among nurses with previous experience working during pandemics. A nurse with working experience during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak did not consider the HSI pandemic a threat to her own health:

“I have no special feelings towards HSI, because I have experienced the SARS outbreak. The severity of SARS is far much higher than HSI. As I have come through the challenge of SARS, the threat of HSI to me is relatively mild.”

Another nurse described that the severity of the influenza outbreak was minor compared with that of avian flu:

“Worry? Not at all. HSI is rather trivial to me. Its mortality rate is low compared with avian flu, and is pretty much the same as common flu. Even if I contract it, remedy is readily available.”

Health of household members

Family safety was another important issue that affected the participants. Six of the participants expressed worry about transmitting the influenza pathogen to family members. One participant described her feelings as follows:

“I am worried about taking the disease to relatives…my grandparents are weak and unwell, so I tried to isolate myself and keep them at a distance.”

On the other hand, two participants diagnosed with HSI have described their action to reduce the infectious risk for household members:

“I have done something to protect my family. I reminded myself to keep them at a distance, for example, having meals separately…In the peak of the HSI outbreak, I tried to stay at home and separate myself from others.”

Health of the public

Social havoc can be wreaked during a pandemic. Eight of the 10 participants expressed the view that the public overreacted to the threat of the HSI pandemic. One participant described her feelings as follows:

“The public went into panic about HSI. I think they were too sensitive, too nervous…They attended our department with only mild flu symptoms……Their worries were exaggerated.”

Comments on the administration

Communication

Effective planning for the communication of disease-related information is of paramount importance in the management of major global pandemic outbreaks (WHO, 2011). Half the participants were satisfied with the effective information communication in the department. A participant described it this way:

“The circulation of information is good…Information provided is up-to-date and is renewed immediately if there are any changes…The information is detailed, relevant and useful to our work.”

However, problems can occur with excessive guidelines. Four nurses reported an excess of information and rapidly changing regulations for infection control. One participant stated the following:

“The guidelines are a little bit confusing. It is difficult to identify which version is the most up-to-date one. And the information is too detailed and not succinct enough, making it not easy to point out the focal points from the materials.”

Manpower

Patient volume swelled considerably during the HSI outbreak (Corley et al., 2010, Lautenbach et al., 2010). This situation was actually echoed by all the participants in the current study. Moreover, nine participants described how they had to cope with huge workloads because of the increase in patient attendance in the emergency department. A participant further described that increased clinical inquiries from patients could impose added burden to their work:

“There were so many nervous patients and relatives asked for information related to HSI…I had to answer their questions while there was already too much work assigned to me. My workload then even got heavier.”

The delivery of emergency medical services is essential and requires adequate staffing (Lopez et al., 2004). However, seven of the 10 participants experienced a dearth of effective strategies in accessing and coordinating labor resources required for extensive emergency care needs. One participant recounted the following situation:

“Workload increased, but there was no reallocation of staff. Even so, they only provide us ‘man’, but with no ‘power’. While there were new staffs, I have to teach them what to do, how to do, when to do, it was actually increasing the workload of us.”

Personal protective equipment (PPE)

In addition to allocating sufficient human resources, ensuring an adequate supply of material resources is the responsibility of the administrator. PPE is of paramount importance when managing influenza pandemic threats to protect personnel health and control the spread of contagious germs (Ives et al., 2009, Wong et al., 2008). Regardless of the effectiveness of PPE, six participants expressed views that the PPE provided was “not user-friendly.” One participant described the inconvenience as follows:

“It is very uncomfortable wearing the PPE…The face-shield is quite troublesome, because there will be vapor on the screen when talking to the patient…The face-shield blocks my voice, I have to speak very loud to get myself heard by patients.”

Another participant described the tiresome gowning and de-gowning of PPE:

“We had to gown the PPE up before taking nasopharyngeal swabs and aspirates for patients, and then gown down afterwards. If there was another patient who needed to take the swab, I had to again gown up and gown down. It is very time-consuming.”

Attitudes of professionalism

Demonstrating professional commitment

During the influenza outbreak, nurses endured a considerable amount of hardship directly attributed to the occupational hazard of disease exposure in the workplace. The descriptions provided by six participants shed light on the explanation that the faithfulness of nurses to their duties could be related to their eagerness to fulfill professional commitments. A participant demonstrated the awareness of the obligation of a nurse as follows:

“Everyone has to take their own responsibility towards the society. If I, as a nurse, retreated from the threats of influenza, who is going to help the sick people? It is a feeling of mission calling. I am doing what I need to do as a nurse, rather than act cowardly.”

Maintaining professional morale

The physical well-being of nurses could obviously be threatened in the course of the HSI pandemic. Additionally, the fight against the pandemic flu could create considerable psychological effects to nurses. Eight of the total participants reported the psychological stress was largely due to increased workload in the emergency department. This participant experienced mounting work-related tension as follows:

“I think my work performance was affected and I am frustrated about that… The pressure from work was great…It was like the situation of patient flow was uncontrollable…A sense of powerlessness…I felt discomfort about these feelings.”

Owing to the abovementioned psychological disturbances from the work environment, the psychological morale of emergency nurses could be adversely affected. Nonetheless, eight emergency nurses confirmed that they maintained their professional morale. A participant said:

“The morale was satisfactory. Nobody was dejected. The working environment is encouraging. There is no need for material rewards to cheer us up.”

Striving for quality of care

Despite the tremendous operational effects of HSI on the emergency department, favorable effects on the quality of emergency services were reported. Five participants perceived that lessons were learned from the HSI outbreak. One participant affirmed benefitting from the experience:

“It is a treasurable experience…With the experience of HSI outbreak, I would be more skillful in handling seasonal flu in the coming years…I will be more adapted to future pandemic situations, because I am more knowledgeable about infectious disease, and more familiar with infection control practice.”

Discussion

Not surprisingly, emergency nurses experienced anxiety regarding their own health during the HSI pandemic. The finding is consistent with previous studies and demonstrates that healthcare professionals react with fear for their own safety during HSI (Corley et al., 2010) and other infectious disease outbreaks (Balicer et al., 2006, Chung et al., 2005, Ives et al., 2009, O’Boyle et al., 2006). It is found that nurses with previous pandemic experience perceived significantly milder risk to the HSI pandemic. The inconsonance of participants in perceived hazard toward HSI could be attributed to their experience with previous infectious disease outbreaks. As the experience in dealing with infectious disease outbreaks broadens, the proficiency in managing infectious diseases in terms of knowledge and skills will be reinforced (Stuart and Gillespie, 2008). Indeed, the accumulation of pandemic experience will strengthen the perceived preparedness of frontline nurses to pandemic situations (Sugerman et al., 2011).

Besides personal health, fear among participants regarding the susceptibility of their significant others to infection was indicated. A study in Australia identified that the worry of transmitting HSI to susceptible relatives at home was prevalent among nurses (Corley et al., 2010). Another study in Singapore illustrated the perceived insecurity of healthcare professionals regarding the health of their families during infectious disease outbreaks (Wong et al., 2008). The findings of this study also provide information that self-quarantine is one strategy that participants employ to minimize the transmission hazard to their family. Self-quarantine is deemed effective in limiting the spread of pathogens (Rao et al., 2009). However, because of the generally congested living environment in HK, household isolation measures could be unintentionally violated, thus influencing the efficacy of protecting family members against germs (Huang, 2009). Further researches in studying the effectiveness of home-based self-quarantine strategy would be worthwhile as existing knowledge in this area is scare.

Ironically, although personal health and family health were being threaten, the participants in this study considered the severity of the HSI outbreak as a threat to public health to be overrated. This phenomenon could be explained by the disparity in perceptions of the severity of HSI. Frontline nurses based their judgments on HSI’s lethality because of the life-saving nature of their jobs. As a result, the danger of HSI having an insignificantly high mortality rate would be viewed as unimportant. The literature also supports the view that the attention of nurses is frequently confined to their own personal health, with oversight regarding public health issues and disease prevalence (Goodwin et al., 2009).

The problem of information overload was highlighted by the participants about the administrative response to the pandemic. Nurses encountered difficulties in distinguishing the relevance of guidelines and measures because there was too much information provided from diverse sources. The same problem has been reported by physicians in the United Kingdom. Caley et al. (2010) stated that physicians were perplexed by healthcare advice during the HSI outbreak because excessive information was provided by the healthcare authority. The ambiguity of the guidelines could adversely affect adherence to infection control measures and consequently increase the risk of hospital-acquired infections to the staff and the public (Elliott, 2009).

The shortage of manpower posed another problem to the participants during the outbreak. A shortage of nurses is anticipated in Hong Kong (HK) at the peak of the HSI pandemic (Wong et al., 2010). Despite patients’ pressing need for information, incorporating patient education amidst the tension at work could be difficult for frontline nurses (Ives et al., 2009). Although patient education is considered an integral part of nurses’ role in providing total patient care (Black and Hawks, 2009), constraints, such as workload restrictions, were imposed on nurses which hindered them from teaching patients (Walsh and Crumbie, 2007). However, inconsistency was recognized in a previous study arguing that nurses would be readily available to deliver information to patients and relatives easily (Chung et al., 2005). Various circumstances require consideration in assessing nurses’ willingness to provide patient education amidst the pandemic.

The participants in this study highlighted the importance of staff training to combat HSI outbreak. Effective training would equip nurses with the knowledge and clinical skills applicable to patient care, which would benefit their capabilities for handling major health emergency threats such as pandemic situations (Leiba et al., 2006; Vinson, 2007). In addition to enhancing the pandemic preparedness of the frontline staff through preliminary training, the smooth functioning of the healthcare institution in response to disease outbreaks should also be maintained (Hynes, 2006).

Although the significance of PPE in reducing the risk of exposure to diseases was recognized by the participants, their experience indicated that utilization of the PPE was uncomfortable and time-consuming. In a study in Australia, PPE usage was reported to be annoying for frontline staff and created unnecessary duties during the HSI pandemic (Corley et al., 2010). The perception of discomfort and inconvenience of PPE might affect the compliance of healthcare professionals in using PPE. The refusal to adhere to PPE utilization use could pose a threat to public health (Loeb et al., 2004). Administrators should persuade frontline healthcare workers to use PPE properly by describing the proven effectiveness of PPE in preventing contamination.

The sense of commitment to patient care compelled emergency nurses to strictly adhere to their duties under the dire threat of the HSI outbreak. As was shown in previous studies, healthcare professionals were willing to work despite the potential risk of infection due to their professional obligations (Corley et al., 2010, Leiba et al., 2006, Wong et al., 2008). In addition to retaining efficient manpower, a sense of strong professional commitment contributes to an improved quality of nursing care regarding the level of overall patient safety (Teng et al., 2009). Controversially, there were evidences suggested that threat of diseases could predominate professional obligations of the healthcare professionals. From Wong et al. (2010) study, it was revealed that a large proportion of community nurses (as high as 70%) would be unwilling to work in the pandemic period of HSI. More than a tenth of the healthcare manpower was also estimated to decrease in an epidemic event because of absenteeism among healthcare professionals (Tam et al., 2007). Reasons behind the huge difference in healthcare professionals’ preferences over willingness to work addressed the need for further in-depth studies on this aspect.

Nurses would suffer from psychological distress, including fear, anxiety, frustration, and powerlessness. Findings in the current study concur with previous investigations exploring healthcare personnel’s perceived effects of potential influenza pandemic, showing that disturbance could affect mental and psychological health (Imai et al., 2008, Wong et al., 2008). The psychological morale of emergency nurses could also be adversely affected during the HSI pandemic (Imai et al., 2008, Wong et al., 2008). Poor morale among staff in the emergency department has been anticipated in the literature (Robinson et al., 2009). Although the participating nurses described their motivation at work as being satisfactorily sustained during the pandemic, a study in the United Kingdom indicated that the morale among healthcare professionals was undermined because of a paucity of recognition from their employer (Ives et al., 2009).

Based on the descriptions of the participants, experiences from the HSI pandemic can benefit the quality of care from personal and institutional perspectives. Emergency nurses are more resourceful in managing patient health needs while possessing knowledge regarding communicable diseases (Hynes, 2006). The risk of disease contagion can be lowered with improved adherence to infection control measures by emergency nurses (Johal, 2009). As the readiness of the staff improves for future outbreaks, institutional preparedness can be elevated for responding to future public health emergencies (Stuart and Gillespie, 2008). A similar conclusion was obtained in a study that found that the quality of patient care was improved after the havoc wreaked by the SARS outbreak (Tam et al., 2007).

Limitations

The major limitation is related to sample size. Due to time and resource constraints, only 10 nurses were recruited. Although there are no strict requirements for sample sizes in qualitative research (Burns and Grove, 2005), a larger sample size could promote the attainment of data saturation (Green and Thorogood, 2009). Expanded studies with larger sample sizes are recommended to facilitate the comprehensiveness and amplitude of findings.

Another limitation in this study was in the gender diversity of participants. Only female emergency nurses were recruited in this study. Although the researcher recognized the importance of recruiting both male and female participants to ensure diversity and richness of data, there were no male nurses matching the recruitment criteria that were available for participation. The lack of male nurses in the study limits the extent to which the results can fully reveal the perceptions of the participants and achieve data saturation.

Implications for emergency nurses

The current findings provide important insight into devising strategies for the allocation of manpower. Surges in the demand for emergency medical services during a pandemic, which can pose challenges to the availability of manpower, should be anticipated. To address increased staffing needs with limited human resources, the deployment of manpower should be decisively considered and implemented. Non-urgent healthcare services, such as elective investigations and surgeries, can be temporary curtailed or suspended. The reserved manpower can be reallocated to the emergency department to match the available supply of personnel with the public demand for emergency healthcare services.

The necessity of developing regulations for the dissemination of information in the emergency department is indicated as a result of this study. The amount and volume of information in healthcare facilities should be substantial, especially in the midst of a pandemic when information regarding disease management needs to be frequently updated and renewed. Standardized information from designated sources would effectively reduce the ambiguity of data received by frontline nurses and other healthcare professionals.

Conclusions

In a pandemic, emergency nurses are confronted by substantial difficulties in providing healthcare services to patients with uncharted infectious statuses. This study provides a rich description of the perceptions of emergency nurses in HK toward work during the HSI pandemic. The experiences of the nurses were explored, and their views were validated via critical examination and comparisons with previous research. The results of this study provide insights into enhancing the preparedness of healthcare facilities for future pandemics and facilitate evaluation of the quality of care delivered by emergency nurses. Additional research should be undertaken to expand the understanding of factors that influence the perception of nurses and the quality of nursing during pandemics.

References

- Balicer R.D., Omer S.B., Barnett D.J., Everly G.S. Local public health workers’ perceptions toward responding to an influenza pandemic. BioMed Central Public Health. 2006;6:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg B. Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 2007. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Black J.M., Hawks J.H. Saunders Elsevier; St. Louis, MO: 2009. Medical–Surgical Nursing: Clinical Management for Positive Outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- Burns N., Grove S.K. Saunders Elsevier; St. Louis, MO: 2005. Study Guide for the Practice of Nursing Research: Conduct, Critique, and Utilization. [Google Scholar]

- Caley M., Sidhu K., Shukla R. GPs’ opinions on the NHS and HPA response to the first wave of the influenza A/H1N1 pandemic. The British Journal of General Practice. 2010;60(573):283–285. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung P.M., Wong K.S., Seun S.B., Chung W.Y. SARS: caring for patients in Hong Kong. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005;14:510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley A., Hammond N.E., Fraser J.F. The experiences of health care workers employed in an Australian intensive care unit during the H1N1 Influenza pandemic of 2009: a phenomenological study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2010;47:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin N.K., Lincoln Y.S. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott P. Radcliffe Publishing; Abingdon: 2009. Infection Control: A Psychosocial Approach to Changing Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin R., Haque S., Neto F., Myers L.B. Initial psychological responses to influenza A, H1N1 (“swine flu”) BioMed Central Infectious Diseases. 2009;9(166):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J., Thorogood N. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. [Google Scholar]

- Guba E.G. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educational Communication and Technology Journal. 1981;29(2):75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. In-flew-enza: pandemic flu and its security implications. In: Cooper A.F., Kirton Innovation J.J., editors. In global Health Governance: Critical Cases. Ashgate; London: 2009. pp. 127–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hynes P. Reflections on critical care emergency preparedness: the necessity of planned education and leadership training for nurses. Dynamics. 2006;17(4):18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T., Takahashi K., Todoroki M., Kunishima H. Perception in relation to a potential influenza pandemic among healthcare workers in Japan: implication for preparedness. Journal of Occupational Health. 2008;50:13–23. doi: 10.1539/joh.50.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives J., Greenfield S., Parry J.M. Healthcare workers’ attitudes to working during pandemic influenza: a qualitative study. BioMed Central Public Health. 2009;9(56):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johal S.S. Psychosocial impacts of quarantine during disease outbreaks and interventions that may help to relieve strain. Journal of the New Zealand Medical Association. 2009;122(1296):47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenbach E., Saint S., Henderson D.K., Harris A.D. Initial response of health care institutions to emergence of H1N1 influenza: experiences, obstacles, and perceived future needs. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010;50:523–527. doi: 10.1086/650169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiba A., Goldberg A., Hourvitz A., Aran A., Weiss G., Leiba R. Lessons learned from clinical anthrax drills: evaluation of knowledge and preparedness for a bioterrorist threat in Israeli emergency departments. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2006;48(2):194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y., Guba E. Sage Publications; New York, NY: 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb M., McGeer A., Henry B., Ofner M., Rose D., Hlywka T. SARS among critical care nurses, Toronto. Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal. 2004;10(2):251–255. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez V., Wong Y.C., Chan K.S. SARS: consequences for nurses, intensive care units and the health care system in Hong Kong. Connect: The World of Critical Care Nursing. 2004;2:91–93. [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle C., Robertson C., Secor-turner M. Nurses’ beliefs about public health emergencies: fear of abandonment. American Journal of Infection Control. 2006;34:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovens H., Thompson J., Lyver M., Murray M.J. Implication of the SARS outbreak for Canadian emergency department. Journal of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physician. 2003;5(5):343–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parahoo A.K. Palgrave Macmillan; New York, NY: 2006. Nursing Research: Principles, Process and Issues. [Google Scholar]

- Polit D.F., Beck C.T. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2008. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Polit D.F., Beck C.T. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2010. Nursing Research, Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Rao S., Scattolini G.N., Caram L.B., Frederick J., Moorefield M., Woods C.W. Adherence to self-quarantine recommendations during an outbreak of norovirus infection. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2009;30(9):896–899. doi: 10.1086/598346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S.M., Sutherland H.R., Spooner J.W., Bennett J.H., Lit C.A., Graham C.A. Ten things your emergency department should consider to prepare for pandemic influenza. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2009;26:497–500. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.061499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson C. Blackwell Publishers; Oxford: 2002. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart R.L., Gillespie E.E. Preparing for an influenza pandemic: healthcare workers’ opinions on working during a pandemic. Healthcare Infection. 2008;13(3):95–99. doi: 10.1071/HI08024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugerman D., Nadeau K.H., Lafond K., Jhung M., Isakov A., Greenwald I. A survey of emergency department 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) surge preparedness—Atlanta, Georgia, July–October 2009. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;52(S1):177–182. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam K.P., Lee S., Lee S.S. Impact of SARS on avian influenza preparedness in healthcare workers. Infection. 2007;35(5):320–325. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-6353-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng C.I., Dai Y.T., Shyu Y.I., Wong M.K., Chu T.L., Tsai Y.H. Professional commitment, patient safety, and patient-perceived care quality. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2009;41(3):301–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson E. Managing bioterrorism mass casualties in an emergency department: lessons learned from a rural community hospital disaster drill. Disaster Management & Response. 2007;5(1):18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.dmr.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh M., Crumbie A. Bailliere Tindal Elsevier; New York, NY: 2007. Watson’s Clinical Nursing and Related Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Wong T.Y., Koh C.H., Cheong S.K. Concerns, perceived impact and preparedness in an avian influenza pandemic: a comparative study between healthcare workers in primary and tertiary care. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 2008;37:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L.Y., Wong, Y.S., Kung, K., Cheung, W.L., Gao, T., Griffiths, S., 2010. Will the community nurse continue to function during H1N1 influenza pandemic: a cross-sectional study of Hong Kong community nurses. BioMed Central Health Services Research 10, (107). <http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/10/107> (retrieved 19.01.11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization, 2010. Influenza A (H1N1): pandemic alert phase 6 declared, of moderate severity. <http://www.euro.who.int/influenza/AH1N1/20090611_11> (accessed 04.03.10).

- World Health Organization, 2011. Pandemic influenza preparedness and response. <http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/pipguidance2009/en/index.html> (accessed 22.04.11).